Informacijos mokslai ISSN 1392-0561 eISSN 1392-1487

2020, vol. 87, pp. 52–71 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2020.87.26

MAX share this! Vote for us! Analysis of pre-election Facebook communication and audience reactions of Latvia’s populist party KPV LV leader Aldis Gobzems

Anda Rožukalne

Riga Stradins University, Faculty of Communication, Latvia

e-mail: anda.rozukalne@rsu.lv

Abstract. This article analyses the communication content by the Latvian populistic party KPV LV (LETA; Re: Baltica) and the audience’s reaction, with a focus on the daily updates and live videos that were posted on Facebook (FB) prior to the 13th elections of the Saeima (Parliament of Latvia). The aim of the research is to determine the type of populism that KPV LV employed (de Wreese, 2018).

The research data was collected during the pre-election period in August – September 2018, when the popularity and social media activity of the party increased. The methods employed were qualitative and quantitative content analysis. In order to identify the structure of emotions expressed in audience-created content, the online data analysis tool “Emotion Recognition Model” was used. Given that populist ideology manifests itself in specific discursive patterns (Kriesi, Papas, 2015), the data interpretation was based on theoretical findings about populism as a political communication style (Jagers, Walgrave, 2007). In order to analyze the interrelations between populist communication and its audience, this study employed theoretical literature on social media use in populist communication and on expressions of emotions in social networking sites.

Keywords: populist communication, Facebook, social media audience engagement, emotions, Latvia

Received: 17/01/20. Accepted: 02/03/20

Copyright © 2019 Anda Rožukalne. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

June 20 and 21, 2018 were unusual both on Latvia’s political stage and in media experience. Firstly, employees of The Corruption Prevention and Combatting Bureau (KNAB), having received permission from the Saeima, arrested Artuss Kaimiņš, a parliament member belonging to no faction and the founder of the party KPV LV (abbreviation from Kam pieder valsts? ‘Who Owns the State?’) (Skaties, 20 June 2018). A. Kaimiņš and two others were arrested on suspicion about vast illegal financing of the political organisation. Secondly, on the next day, the public medium Latvian Television broadcasted a FB live video that showed supporters of the party awaiting the liberation of the arrested and voicing their disagreement with the arrest and their contempt of the institution (LSM, 21 June 2018). When the arrested left the isolator, A. Kaimiņš and his personal friend Aldis Gobzems, a lawyer and the party’s candidate for the position of Prime Minister, were welcomed with loud exclamations of support.

In many countries, right-wing populists are identified through the help of party leaders, extraordinary personalities, such as Le Pen in France, Nigel Farage in the UK, Tsipras of Syriza in Greece and others. Latvia is no exception. Regarding populism in Latvia, only a few names can be mentioned as its representatives, but the most prominent among them, both in their actions and communication, are the already-mentioned parliament member and former actor A. Kaimiņš and the lawyer A. Gobzems. The party KPV LV was founded on May 3, 2016 (Panorāma, 3 May 2016). Its founder A. Kaimiņš had been elected to the 12th Saeima in 2014 as a representative of Latvia’s Regional Alliance. He had previously gained popularity by hosting an online radio talk-show (Rožukalne, 14 August 2014). In the spring of 2018, the party KPV LV nominated A. Gobzems as their candidate of Prime Minister (LSM, 13 May 2018). When pre-election campaign began in July 2018, A. Gobzems’ communication became very active, leaving the previous leader A. Kaimiņš behind.

Populist parties and politicians have been active in Latvia’s political environment since the early 1990s (Balcere, 2015), but usually they were not very successful. Recent historical events have changed this situation. In August 2018, less than two months before election, KPV LV ranked third (7.5%) amongst the 16 parties running for the Saeima. According to SKDS data, 9.5% of men and 5.7% of women supported KPV LV by August 2018. The supporters of the party were mostly aged 18 to 24 (15.2%) and 25 to 34 (11%), other age groups showed less interest – 7% to 2.5%. KPV LV won the second place in the 2018 parliamentary elections and 16 seats (16%) in the Parliament.

One year later, it seems that the party might soon disappear from the political scene of Latvia. Its founder A. Kaimiņš has lost chairmanship of the parliamentary faction, while Prime Minister candidate A. Gobzems has been expelled from the party and three other deputies have left the faction. The party has lost not only its power in the Parliament but also voters’ support, and by September 2019 the rating of KPV LV had dropped to 2.8 percent (Bērtule, 27 September 2019).

Over the last decade, the political map of Europe has been altered by the success of populist parties in elections. These processes have also influenced populism studies, which mostly analyse the driving forces of this turn in Western Europe (Schmidt, 2018). The peculiarities of populist politicians in Central and Eastern Europe as well as in Scandinavia have been discussed in a special issue of the Central European Journal of Communication (Stepinska, 2018). The dynamic development of populist parties, their usually quite short life cycles, and the differences in electoral cycles in each country might be the main reasons why most populism studies are single-case studies (see: Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2008; Boss and Kees, 2014; Lees, 2018; Suiter et al., 2018) with a few exceptions of comparative studies (see: Schmidt, 2017, Kasprowicz and Hess, 2019). This situation is determined by both the resources available for research and the objective need to assess the nature of populism in each particular country. In Latvia, populist electoral success and the discourse of populism in political party programs have already been studied (Balcere, 2015), but until now there has not yet been any study analysing the interaction between the populist parties’ communication and the reaction of their audience.

2. Literature review

2.1 Rise of populism and populist communication

When analysing the causes of the development of populism, researchers come to a number of similar conclusions related to changes in the socio-economic situation (Hameleers, 2016; Zulianello et al., 2018) in different countries. The potential for the rise of populism is increased by inequality and the dropping levels of life conditions. Populism analysing theory links the worsening economic prospects to rapid technological development (Postill, 2018), which allegedly creates a gap between elites and ordinary citizens. Observing the political success of populists and the restructuring of political powers, many researchers have redefined populism, drawing useful conclusions for an analytical assessment. Klaes de Wreese et al. (2018) emphasise two main reasons for the spread of populism: economic insecurity and cultural backlash (Hameleers, 2016; Wreese et al., 2018). Socio-economic problems are a fertile ground for society’s dissatisfaction (Wahl-Jorgensen, 2018), making voters angry. Proof of these explanations can be found in the recent past, as the first decade of the 21st century brought economic crisis to many countries.

Applying these criteria to Latvia, we can identify several factors contributing to the development of populism. After the economic recession in 2008 and 2009, when GDP in Latvia shrunk by 25%, a period of moderate economic growth followed (Ministry of Economy, 2018). One of the most serious developmental issues in Latvia is the negative birth-rate and emigration. Since the beginning of the 21st century, 9% of Latvia’s population have emigrated for various reasons (Hazans, 2013). Since 2010, the population of Latvia has shrunk by 170 thousand or 8%. Due to migration, Latvia has lost 113 thousand inhabitants, and because of its negative birth-rate – 57 thousand (Central Statistics Bureau, 2017).

Nearly all political parties that participated in the pre-election campaign in 2018 touched upon the emigration issue. Latvia lacks workforce in many spheres, and some entrepreneurs are hoping for more flexible laws regarding the immigration and residence of workforce from third world countries. Economic reasons, however, are being juxtaposed with culture preservation concerns. The Latvian society still holds in their collective memory the massive immigration during the Soviet rule and the subsequent russification. Most of the society is negatively positioned against any immigration (Eurobarometer, 2015). The declared task to return the emigrated inhabitants to Latvia is even more complicated. Latvia as a nation united across borders is but an ideal concept; it is difficult to speak of a unifying diaspora in practice (Lulle et al, 2015). These aspects identify groups in Latvian society whose interests can be used to construct in-groups (Latvians, protectors of national culture, local businessmen, emigrants) and out-groups (immigrants, foreign investors, unreliable officials, government institutions, and professional media) on a political level.

Sociological research shows that the society’s distrust towards governmental institutions and dissatisfaction with the developmental direction of the country is long-lasting. The Shared disposition index created by the Latvian Barometer survey reveals that most respondents think that Latvia is developing in the wrong direction. This data has not improved since 2010 (SKDS, August 2018). This background makes the 2018 pre-election political messages more understandable. KPV LV leaders spread information about Latvia’s economic issues in their FB posts, raising doubts even about statistic data. In other countries, populism supporters also tend to evaluate the economic situation as worse than it actually is (Stokes, 2018).

According to de Wreese (2018), populist success is more likely in countries with weak media and other democratic institutions. These factors place Latvia at high risk, as the media market is narrow and highly concentrated (Jastramskis et al. 2017), and the quality of media content is influenced by political parallelism (Rožukalne, 2013) and by instrumental journalistic culture (Dimants, 2017).

When explaining the success of populism, scholarly discussion focuses on populist ideas and communication. Populism ideology is characterised by dividing the society in two groups: ‘blameless people’ who suffer from those at fault and their political decisions. To emphasise the ‘people-cantered’ and ‘anti-elitist’ discourse, these groups are called blameless in-group and culprit out-group (Hameleers, 2016, 3). The contrast of ‘we’ and ‘they’ can be achieved in politician and media-constructed communication (Gidron, Hall, 2017). The populist definitions of antagonistic and homogenous group characteristics are shaped via communication. It could be one of the reasons why populism is seldom regarded as a political ideology; it is mostly described as a style of political practice and communication (Wolkenstein, 2015). De Wreese et al. (2018) claim that content determines the main components of populism ideology, but the style is equally important, as it determines the specific elements of content presentation in populist communication. Populists’ primitivism, loudness, and orientation towards outrageous issues is called the tabloidisation of politics (Wolkenstein, 2015). Aalberg et al. (2016) describe populism as a set of characteristics that reflect populist ideology on a communicative level. Wirz et al. (2018) claim that a message can be defined as populistic content-wise if it addresses people as a unified and positively positioned group, while the elite is discredited and certain social groups are excluded or defined as harmful to the society’s interests. Researchers point out that populists use emotional, dramatic absolutism or colloquial language (Wirz et al., 2018: 497). An important element in populist communication is the use of emotional style. For reflecting on political issues, emotional blame-attribution is actively used as a framework (Hameleers et al. 2016, 4).

The rise of populism in the context of democracy development is ambiguous. On the one hand, it can be called a “refreshing wakeup call” (de Wreese et al. 2018, 424) for the current politicians in power. On the other hand, it can leave a negative impact on liberal democracies; through the use of election rights, populist forces can affect independent institutions, such as courts and free media.

In order to define the aims and scope of this study, theoretical concepts that explain populism in relation with communication and the typology of populism elaborated by de Vreese (2018) have been used. De Vreese (2018) offers three types of populism that can be determined empirically. In his classification, complete populism includes concentration on “people”, anti-elitism, and exclusion of out-groups; excluding populism tries to address “people” and to define excluded out-groups; empty populism aims only towards “people”.

2.2 Populism and social media communication

Empirical research shows that populist success is increased by the development of social media and the populist actors’ skills to effectively use the new communication platforms (Rožukalne, 2017; Bobba et al., 2018, Postill, 2018). Social media are a fertile ground (Engesser et al., 2017) for populist communication that helps populist politicians to bypass the use of professional media during election campaigns. Social media communication makes it easy to avoid the boundaries of social groups. It is close to the characteristics of direct democracy and plebiscitary democracy (Dahlgren, 2013; Alvares, Dahlgren, 2017). The form of communication in social networking platforms creates an illusion of proximity to the politicians, rendering the communication informal (Tuukka, 2017; Enli, Rosenberg, 2018; Postill, 2018). As Enli and Rosenberg (2018) conclude, politicians look more honest in the social media environment. The open and direct communication style of the populists on social media makes voters to rate these politicians as more authentic and realistic than other politicians. Moreover, the voters’ willingness to follow politicians on social media platforms is determined by their desire to receive information that has not been processed by journalists and news media (Newman, 2017).

Trust in the politicians’ messages is enhanced by the appreciation of the networking process and the presence of other users (Enli, 2015). Constructing one’s own authenticity and spontaneity is a part of the populist communication strategy (Enli, 2015), it helps populists to justify anti-elitism. By using the opportunities provided by social media communication, populist political communication increases its impact, because a large part of media users consumes news via social networking platforms (Newman, 2019), and voters consider their more actively used media as more reliable.

The use of social media and the politicians’ interaction with their supporters can be viewed, according to Gerbaudo (2018), as opinion-building and movement-building. The algorithm and other features of the social media system help the supporters of an idea to easily find one another in the online environment. Alongside the anti-elite statements and the encouragements to the ordinary people, Gerbaudo (2018) has identified attacks against neoliberalism ideology, exclusion of the different groups, and xenophobia. This is more characteristic to right-wing populists, whereas left-wing populists tend to demonstrate the ordinary peoples’ moral superiority over the greedy bankers and businessmen and the corrupt politicians exploiting them (Gerbaudo, 2018, 96–97).

From the perspective of populist interests, social media promote the effect of mobilisation, creating online crowds of similarly thinking individuals (Gerbaudo, 2018, Postill, 2018). The so-called ‘network effect’ also helps to form groups, as it is a part of the social media algorithm whereby the more frequently connected nodes are linked more and more tightly. Social media use in the communication of populist parties does not mean that the other parties cannot use social media. Gerbaudo (2018) and Zulianello et al. (2018) conclude that observing the success factors of populist communication other parties also start to adopt the populist style of expression in their communication.

2.3 Populist communication and emotions

An important factor that makes populist communication attractive is emotions – in the messages and the rhetoric, as well as in the perception by the audience. In most literature, emotions are analysed in the context of populist communication, because they show the essence of populism: complex relationships between conflicting groups resembling “friend and foe” communication forms (Schmidt, 2017: 461). Some studies see the emotionalisation of politics (Salmela, von Scheve, 2018) as the interaction between populist voters and politicians. Some scholars link the increase in emotional communication to populism-fuelling external factors, such as inequality and economic instability, as well as to mechanisms of social psychology (Salmela, von Scheve, 2017; Salmela, von Scheve, 2018), where emotions play an important role. Thus, the reality of digital communication, where the emotional attitude emerging alongside the audience’s comments and opinions generates “emotional noise” (Garde-Hansen, Gorton, 2013), raises questions about how to evaluate emotions in public communication.

The study of emotions in social sciences is accompanied by the explanation that their characterisation is complex and there is no unified definition of emotion (Arquembourg, 2015). Klaus R. Scherer defines emotion as ‘‘an episode of interrelated, synchronized changes in the states of all or most of five organismic subsystems in response to the evaluation of an external or internal stimulus event as relevant to major concerns of the organism’’ (Scherer, 2004: 668). In the same time, emotions are expressed in relation to preferences, attitudes, moods, interpersonal stances, feelings and many other phenomena (Scherer, 2004).

Analysis of media-related emotions shows that group emotions are created by a surprising or novel information. Moreover, individual emotions are responses to unexpected information “that can initiate social behaviour” (Margolin, Wang, 2018:4). In the context of semiotic approach (Arquembourg, 2015), communication and the social aspect are crucial in emotion determination, as the awareness of joy, admiration, anger or hatred is possible when the social environment contains equal interpretants of these emotions.

Even though the digital sphere lacks a significant part of communication content, the mediated communication causes emotions as powerful as non-mediated communication does, as proven by the Media Equation theory (Gabriels et al., 2014). Emotional events connect the participants with the audience, creating a “synchronized and hyper-realist collective hallucination” (Garde-Hansen, Gorton, 2013:2). In observation of emotions caused by media, postures, gestures and expressions are absent from the analysis; emojis and other signs often can only partly substitute them (Rožukalne, 2018). Most often, only words and texts are available for detailed analysis, as they serve both to express emotions and as responses to other emotions.

The emotions of users as expressed within the social networking platforms belong to the horizontal level of digital communication (Garde-Hansen, Gorton, 2013). The term reflects the equal position and the usually two-directional and feedback-filled communication between the creators and receivers of content.

Emotions in political communication characterise the antagonistic public sphere (Mouffe, 2005), which is the opposite of the Habermassian rational public sphere. Since the presence of emotions in public communication is inevitable (Tong, 2015), they can be described as a normal part of the practice of public democracy.

3. Research design and method

In Latvia, the number of FB users is approaching 800 thousand per day as of 2018 (Kantar, 2018) – it is the most popular social networking platform in the country. During the pre-election period in 2018, KPV LV had chosen this global social medium as their most important communication channel. The present study of the pre-election communication of KPV LV is largely based on assessing its leaders’ communication in social media. Although the party was founded by A. Kaimiņš, the pre-election communication was mainly kept up by another leader of the party, the lawyer A. Gobzems. The content of his FB account constituted the majority of the party’s communication outside political debates and meetings with voters. KPV LV used several FB accounts in their pre-election activities. After comparing their content and users’ data (these accounts have from 400 to 10 thousand followers), A. Gobzems’ account shows the largest number of followers (12,000) and the largest amount of audience engagement data.

As KPV LV is currently (during the time of this study) the only party in Latvia that can be characterised as populist, this is a single case study that employs mixed methods of data gathering and research. They include quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis. The most successful research on populist communication (e.g. the research by Schmidt, 2017) employed quantitative text analysis or classical content analysis. Considering that the sampling principles of classical media content analysis (Kim et al., 2017) cannot be fully applied in the case of social media content (where the production and distribution of content and the audience engagement in the communication process are not limited to a certain period), a method of processing mixed data was chosen. In order to assess the communication content of KPV LV and its possible impact on the audience, qualitative and quantitative content analysis was applied to A. Gobzems’ FB account, focusing on the timeline from August 15, 2018, to September 15, 2018. It was the most active period of the pre-election campaign. Altogether, 101 FB posts were analysed, assessing their format and topic structure, and audience reactions structure as well. In order to compare the political and audience content, qualitative content analysis was applied to A. Gobzems’ FB posts as well as to the audience’s comments on them, (only posts with more than 50 comments were chosen). For rational reasons, when evaluating the quantitative data of audience engagement, 22 out of 101 FB posts (plus the comments) created within one month were chosen for qualitative analysis. Altogether, the content of 6913 audience comments was analysed. In order to operationalize theoretical insights into populist communication styles, additional content analysis categories that identified moralizing, sensationalizing, and attacking style were introduced. Quantitative content analysis was performed automatically by filtering all FB content using keywords referring to certain communication topics and the in-group and out-group. Qualitative analysis of A. Gobzem’s pre-election communication content was carried out manually. Moreover, a research tool “Emotion Recognition Model”, created by researchers of Riga Stradiņš University and already used in a previous study (Rožukalne, 2018), was employed to detect the emotion structure of FB audience comments. “Emotion Recognition Model” is based on Robert Plutchik’s (1980) structure of emotions (Plutchik, Kellerman, 1980). The research tool “Emotion Recognition Model” is based on assumption that the emotions of internet users are revealed by their language. In order to identify FB users’ emotions, the all audience comment’s content was filtered and sorted by using list of words and phrases of “Emotion recognition model” that identify expressed emotions in audience comments.

List of research questions:

RQ1 – What is the content of the KPV LV leader Aldis Gobzems’ communication in FB from mid-August until mid-September of 2018? Do the key topics of communication content point to a particular type of populism?

RQ2 – What is his style of communication and his attitude towards his voters, political competitors and the media during the pre-election period?

RQ 3 – What is the content and structure of emotions in the followers’ comments on his FB posts?

4. Research results

The data show a high diversity of content and a high level of audience engagement in A. Gobzems’ pre-election communication (Chart 1). He posts photos and live videos (about an hour long broadcasts, usually focused on many topics), writes blogs and comments on media content, and attracts attention by announcing future live FB broadcasts.

The audience was reacting to A. Gobzems’ content quite actively. Within a month’s time, his posts were shared 19 677 times, they received 6813 comments and 36 281 reactions represented by emoji. A. Gobzems was also directly urging his followers to react to his posts. Many of his texts and videos started with an invitation ‘Please share!’. A. Gobzems’ posts of that period have received 91% “Like” emoji reactions, 4% “Love” reactions, 3% “Ha ha” reactions, and 2% “Wow” reactions.

A. Gobzems was mostly using FB to popularise his party and to inform about its activities (N=101 posts; N=255 topics). A third (30%) of his post content was dedicated to the pre-election campaign. During that period, mass media often published criticism on the past actions of KPV LV and its leaders. A significant part of A. Gobzems’ communication in FB was devoted to the issue of media and journalism (18%). His attitude towards the media, as shown in his FB content, was twofold: he praised those publications that supported the position of KPV LV (8%), and attacked those media publications that criticised KPV LV. In many posts (9%), A. Gobzems was replying to the voters’ questions and explaining the party’s position on different matters. He frequently criticised his political rivals (11%) and the government elite (6%), as he wanted to present his party as a new power and ‘the only one capable to make a change’. Landscape photos that A. Gobzems had taken with the help of a drone (4%) helped to vary his FB timeline content; 4% of his posts were devoted to other issues – for instance, documents that A. Gobzems had received from or was planning to submit to law enforcement institutions.

Chart 1. Structure of A. Gobzems’ FB posts: form and engagement data. (N=101 posts). Source: Author.

|

FB posts structure and structure of audience engagement data |

Number |

|

FB posts on A. Gobzems’ page during the period chosen for study |

101 |

|

Text blogs (analysis of the party‘s position, reflection on current events, criticism of political rivals, etc.) |

22 |

|

Media publication links posted together with A. Gobzems‘ comment |

14 |

|

Posts that consist of photos and text (e.g. information of the party’s pre-election activities and meetings with voters, excerpts from documents) |

24 |

|

Number of posts that share party activities related content (e.g. official party’s ads, PR activities, reshared posts of KPV LV colleagues, etc.) |

23 |

|

FB live video sessions |

11 |

|

Publications of personal events and/or photos |

7 |

|

Total number of video blog views (11 videos) |

306 000 |

|

Average number of video blog views (11 videos) |

27 000 |

|

Total number of shares of the 101 posts selected for quantitative analysis |

19 677 |

|

Average number of shares of the 101 posts selected for quantitative analysis |

242 |

|

Average number of shares of the 22 posts selected for qualitative analysis |

365 |

|

Total number of emoji reactions added to the 101 posts selected for quantitative analysis |

36 281 |

|

Average number of emoji reactions per post |

359 |

|

Total number of comments added to the 101 posts selected for quantitative analysis |

6918 |

|

Average numbers of comments per post of those added to the 101 posts selected for quantitative analysis |

68 |

|

Total number of comments added to the 22 posts selected for qualitative analysis |

2621 |

|

Average numbers of comments per post of those added to the 22 posts of posts selected for qualitative analysis |

119 |

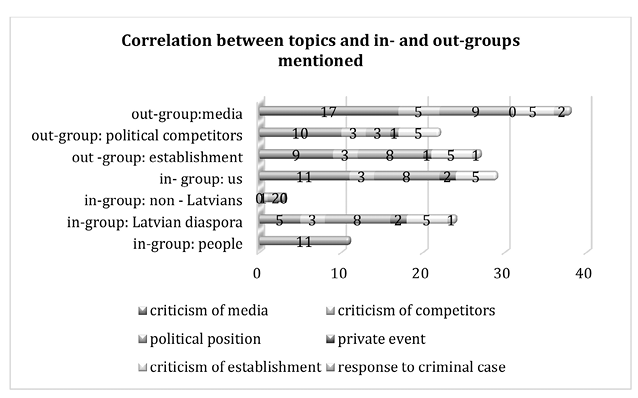

Analysing his FB communication content, the above-mentioned in-groups and out-groups were identified. As A. Gobzems criticised his political rivals (35%), media (33%) and elite (32%), his FB content reveals a similar out-group structure. The politician contrasted himself and his party with those who had been shaping the current Latvian politics – high-level officials and institutions.

A. Gobzems’ defined in-groups are connected to the activities, ideas and supporters of his party. The in-group most frequently mentioned in his FB communication consists of A. Gobzems himself and his party members (43%), described as ‘we’, ‘our kind’. The second largest in-group are ‘the people of Latvia’ (41%) as an entity – to which, according to A. Gobzems, other politicians do not speak, listen, or care about. The main political ideas of KPV LV are related to blaming the elite for their politics that have allegedly forced thousands of inhabitants to leave the country; 10% of the posts mention the representatives of the Latvian diaspora. A. Gobzems emphasises the need to unify the society, several posts mention non-Latvians (6%) as an in-group, and a few posts are published in Russian.

When correlating these data with the FB’s communication content of the leader of KPV LV and the in-groups and out-groups mentioned there (Chart 2), it is obvious that A. Gobzems chooses to include all out-groups defined by KPV LV in each of the relevant topics. For instance, if he criticizes the media, he mentions the media’s different attitude towards his political rivals, KPV LV voters, and officials. It gives him an opportunity to blame the media for not being sufficiently demanding towards the ‘old’ politicians and, according to A. Gobzems, the unprofessionalism of the media is the main reason why they criticise populist politicians and their ideas. A. Gobzems’ rhetoric changes when it comes to his in-groups. The politician selects separate topics to discuss with each particular group. He speaks to the Russian minority in the context of the party’s political position, and mentions the ‘people’ in connection with the criticism directed at the media. In his messages addressed to the Latvian diaspora, he highlights the party’s political views, criticism of the establishment, and the co-responsibility of the media for the emigration of Latvian citizens.

Chart 2. Correlation of the topics and in-groups and out-groups mentioned in A. Gobzems’ FB content. (N=22, N=173 topics). Source: Author.

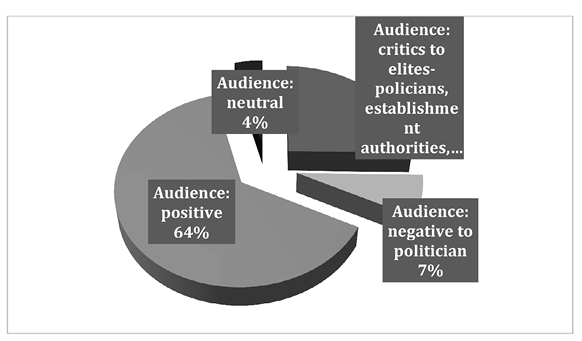

Qualitative content analysis of the most commented posts reveals that the audience is more likely to react to a video or text where a politician touches upon controversial issues: criticises the media (36% of comments), explains his political position (27%), criticises the establishment (17%), criticises his political rivals (10%). Audience also commented on A. Gobzems’ personal events (7%) and on his response to the criminal cases involving his party members (3%).

In his most commented FB posts, A. Gobzems usually expressed a negative attitude (N=22 posts; N=18 negative attitude) towards media and journalist activities, his political rivals, or representatives of the elite. Only a handful of posts showing his political position, as well as his personal events contain a positive (2 posts) or neutral attitude (3 posts).

Assessing the FB post content, communication style was also identified by using separate content analysis categories. When discussing the actions and ideas of his party in contrast to the other parties, elite and media, A. Gobzems frequently claimed himself to be different, better, braver than others. The phrases ‘I risk for you’; ‘we are the only ones who call things by their real names’, etc. imply a moral assessment. His style was mostly moralising (N=9 posts of N=22 posts analysed by using qualitative content analysis) or attacking (N=8 posts). He was trying to create an intrigue and surprise by publicizing documents, private chats, and various information about others’ private lives – these posts can be defined as sensational (N=6 posts).

Chart 3. Structure of the audience’s attitude as expressed in comments. N=6913 comments. Source: Author.

The analysis of the audience’s attitude in their comments on A. Gobzems’ posts shows that it partially coincides with the attitude expressed by emoji reactions. 64% of the comments are overall positive (Chart 4), expressing support and agreeing with the opinions in the posts; 32% of the comments display a negative attitude. Content analysis showed that the negative attitude was directed either towards the issues, people or institutions mentioned by A. Gobzems, (25%), or towards A. Gobzems himself (7%). The audience mostly supported the politician; only a few comments were criticising or neutral (4%), or doubtful and asking additional questions.

Comment analysis used the “Emotion Recognition Model”, which identifies words and phrases referring to specific emotions. Data showed (see Chart 4) that the comments frequently mentioned emotions – some comments even two or more. Their structure coincided with the overall attitude: commenters expressed admiration (29%), trust (29%), and acceptance (15%) towards the politician, and anger (13%), dislike (7%), rage (4%), disgust (2%), shame (1%) towards those who were criticised by A. Gobzems.

Chart 4. Structure of the emotions expressed in audience’s comments. N=6913 comments; N= 5671 comments include emotion; N=12 206 emotional words, phrases; N = 1242 comments with no emotion. Source: Author.

In order to assess the involvement of the audience, it was important to study its behaviour when commenting the daily content on the party’s events. Comments were analysed on the basis of two criteria – categories defined as “response to the topic of post” and “response to the other commenter(s)”. The data showed that in 25% of cases the commenters directly reacted to A. Gobzems’ topics, and only 7% of the commenters engaged in discussions amongst themselves. Other comments (68%) were general, unrelated with the content of A. Gobzems’s posts.

5. Conclusions and discussion

The party KPV LV actively used social media and other digital platforms enabling them to regularly and directly address their audience, presenting their political position, defining in-groups and out-groups, and causing emotions in the audience. The attracted audience reaction to the KPV LV content on FB on a regular basis by demonstrating ‘small acts of engagement’ (Picone et al, 2019).

Answers to research questions:

RQ1 – What is the content of the KPV LV leader Aldis Gobzems’ communication in FB from mid-August until mid-September of 2018? Do the key topics of communication content point to a particular type of populism?

Data shows that A. Gobzems’ communication includes typical features of populism, praising his own actions, criticising the elite, exhibiting support and interest in the needs of ‘the people’. Besides discussing his political position, a large part of A. Gobzems’ communication is about media and journalists. During his FB live streams, A. Gobzems actively responds to his critics in the media and himself criticises journalists, calling them ‘politically engaged’, attacking them personally, claiming them unprofessional, biased and ‘fake news creators’. Contrasting his own communication to that of the media, A. Gobzems constructs the media as an out-group. A part of his communication content consists of reshared media publications which deal with economic, political or social problems. In his own comments, A. Gobzems claims that the establishment is unable to solve the ordinary people’s problems and is only increasing their suffering. Thus, A. Gobzems has an opportunity to criticise his political rivals, especially the “old” politicians and authorities. When commenting on other sources, A. Gobzems stresses his and his party’s superiority. His communication defines particular in-groups (ordinary people, non-Latvians, members of diaspora), and out-groups (the establishment, other politicians, professional media). These out-groups reveal the main goals of A. Gobzems’ communication – the use of social media to conduct a direct political fight against the above-mentioned adversaries. A. Gobzems’s publications are an example of complete populism (in de Vreese’s (2016) classification), as it clearly identifies the ordinary people as the support group, defines out-groups, and displays strict anti-elitism. However, even though the FB communication of KPV LV demonstrates many elements of complete populism, it lacks out-groups that are not a part of anti-elitism messages. Thus, the type of populism shown in the communication of KPV LV might be called ‘complete anti-elite populism’, because all the mentioned out-groups belong to the elite.

RQ2 – What is his style of communication and his attitude towards his voters, political competitors and the media during the pre-election period?

A. Gobzems mostly evaluates events, processes and individuals negatively. This critical view helps him to create a dichotomy between ‘we’ and ‘they’, which is important in distinguishing the ‘good’ KPV LV from the ‘bad’ critics and rivals. His style of communication frequently contains moral evaluation and emphasises the superior qualities of KPV LV: its openness, honesty, determination. When criticising the establishment, A. Gobzems combines moralising and attacking style, he threatens to expose facts that would put the journalists’ reputation in danger. In many publications, he tries to reveal allegedly unknown information in a sensational style: he publicises otherwise unavailable documents and private messages. Thus, KPV LV reflects typical populist characteristics: anti-elitism and aggressive communication (Hameleers et al., 2016; Alvares, Dahlgren, 2016); its communication style is mostly moralising and attacking. As A. Gobzems refrains from defining any out-groups outside the public elite, he perceives ‘the people’ as a homogenous group. This kind of populism is more typical of left-wing politicians (Garbaudo, 2017; Salmela and von Scheve, 2018).

RQ 3 – What is the content and structure of emotions in the followers’ comments on his FB posts?

The structure of the audience’s emotions is quite homogenous as it involves admiration, support, and trust towards the political leader, and anger, disdain, shame, and disgust towards the problems that A. Gobzems mentions. The number of the reactions and comments shows that a part of this feedback consists of automatic responses (Ott, 2016). Many of these comments contain just a greeting, slogan and brief support. In this aspect, A. Gobzems appears to be a successful micro-agenda setter (Wohn, Bowe, 2016) carrying out regular communication with his followers. A. Gobzems employs a style typical of populist politicians in social media. He greets the regular viewers of his live video blogs, refers to some of the commenters as “good friends”, and does not start his speeches before the number of viewers who have joined the FB live has reached at least a hundred. He responds to audience in his video and text posts addresses specific people and responds to comments.

Although the followers of KPV LV rarely discuss issues raised by politicians, they show a high degree of engagement as they actively post emoji, share their posts and show their presence in live video streaming sessions. Emotional reactions, in a way, replace rational discussion, they become the dominant form of audience engagement online. However, the daily routine of A. Gobzems thematically addresses just a small fraction of the commenters; most commenters simply praise the party and its leader instead of actually reacting to the content. This environment resembles an echo-chamber where it is difficult for other opinions to break in, but emotions play a big role (Wang, Hickerson, 2016).

The relations between social media and traditional media content is not separate, but merges in recursive loops of ‘viral reality’ (Postill, 2014), as politicians use traditional media publications to undermine the reputation of media and to attract audience. These practices are most typical of anti-media populism. The choice of communication topics and the audience engagement techniques show that messages encounter hybrid-mediated spaces that do not completely differentiate between off-line and online audiences, populists and non-populists, traditional and social media users (Postill, 2018).

Regular communication on FB and the supporters’ reaction, as well as the generated content, points to a stable fan community of KPV LV. The founder of the party, former actor A. Kaimiņš gained his popularity by using provocative communication style on YouTube. A. Gobzems, despite having contributed to various political forces in the past, had not been actively involved in politics yet. He became popular after the roof of the supermarket “Maxima” collapsed in 2013 and he offered free legal aid to the victims of the accident (Kupčs, Bērtule, 21 August 2017). When A. Gobzems turned to political activity, he added his former followers from the FB account devoted to the supermarket collapse to his new political FB account (Tvnet, 2 August 2018). During the pre-election period, KPV LV also used a humorous FB page “Pārdomu pērles” (Pearls of Reflection) as its platform for political advertising. Already before that, the page was managed by people affiliated to KPV LV. Thus 34,000 followers of the said page became the audience for the party’s official FB account. This digital communication practice demonstrates the importance the party had attached to the size of the audience and the demonstration their own popularity. It proves that the number of followers, audience-generated content and activities was used as a part of the political communication message of KPV LV.

Limitations and future directions

This research project encountered certain limitations concerning obtaining data and the extent of the data. The online communication of KPV LV is fragmented in its content as well as frequency. During the pre-election period, several online channels communicated the same content – advertisements and messages of the political parties. Focusing on the content and audience feedback of A. Gobzems’ FB account, this research covered the largest part of the pre-election content and its audience. However, the audience continues to react to the FB content in the course of time; thus, the data already collected for the study may later change. In the same time, the chosen period represents the dominant style of the political messages and communication of KPV LV. The study does not include information about the strategy of the party’s political communication (Zulianello et al., 2018; Kalsnes, 2019,), therefore no significant indicators of platform communication management can be determined. The party offered a space for user engagement both in the public FB accounts and in the closed groups of the party’s followers (the content of these groups was thus not available for research). This study does not show how many audience comments were deleted and does not differentiate between various behaviour-defined audience groups among the regular followers of A. Gobzems on FB.

Future research directions may include both the collection of additional data and the application of specific tools for gathering digital communication data. The methods employed in this study cannot be used to determine whether the social media audience of KPV LV has the potential to develop into a digital community or fan group (Dean, 2017). However, it would be useful to look into the ways populist politicians use voter engagement to politicize their fans. Another important research issue concerns the status of KPV LV politicians as celebrities. Were the fans of celebrity figures politicized through political communication? Therefore, in the future research of political communication it would be important to use tools that help to distinguish real audience accounts from bots, and to structure the level of user engagement in detail, thus exploring the dynamics of the relations between populist politicians and their followers.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

ALBERTAZZI, Daniele; MCDONNELL, Duncan. (2008). Introduction: The sceptre and the spectre. In: ALBERTAZZI, Daniele; MCDONNELL, Duncan D. (eds.). Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 1–11. ISBN 978-0-230-59210-0

ALVARES, Claudia; DAHLGREN, Peter (2016). Populism, extremism and media: Mapping an uncertain terrain. European Journal of Communication, No. 31(1), p. 46–57.

ARQUEMBOURG, Jocelyne (2015). The collective sharing of emotions in a media process of communication – a pragmatist approach. Social Science Information, No. 54(4), p. 424 – 438.

BALCERE, Ilze (2015). Populisms Latvijas politisko partiju diskursā laika periodā no 1993. līdz 2011. gadam [Populism in discourse of Latvian political parties from 1993 to 2011]. Promocijas darbs. Rīga: Latvijas universitāte.

BĒRTULE, Anete (September 27, 2019). Partiju reitingi: “Saskaņas”pozīcijas vājinās, “KPV LVV” gada laikā lielākais kritums [Party Ratings: Harmony’s positions weaken, KPV LV’s biggest drop during a year]. LSM.lv. Interactive [Accessed on 27 September 2019]. Online access: (https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/latvija/partiju-reitingi-saskanas-pozicijas-vajinas-kpv-lv-gada-laika-lielakais-kritums.a333441/).

BOBBA, Giuliano; CREMONESI, Cristina; MANCOSU, Moreno; SEDDONE, Antonella (2018). Populism and the Gender Gap: Comparing Digital Engagement with Populist and Non-populist Facebook Pages in France, Italy, and Spain. The International Journal of Press/Politics, p.1–18.

BOS, Linda; BRANTS, Kees (2014). Populist rhetoric in politics and media: A longitudinal study of the Netherlands. European Journal of Communication, No. 29(6), p.703–719.

CENTRAL STATISTICS BUREAU (May 30, 2017). Iedzīvotāju skaits Latvijā turpina samazināties [Population in Latvia continues to decrease]. Interactive [Accessed 15 May 2019]. Access through Internet: http://www.csb.gov.lv/notikumi/iedzivotaju-skaits-latvija-turpina-samazinaties-riga-verojams-pieaugums-45899.html.

DAHLGREN, Peter (2013). The Political Web: Media, Participation and Alternative Democracy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-32638-6.

DEAN, Jonathan (2017). Politicising fandom. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, No. 19(2), p. 408–424.

DIMANTS, Ainārs (2018). Latvia. Different journalistic cultures and different media accountability within one media system. In: EBERWEIN, Tobias; FENGLER, Susanne; KARMASIN, Mathias (Eds.), The European Handbook of Media Accountability (pp. 143 – 149). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781315616353

DIMITROVA, Daniela V.; SHEHATA, Adam; STROMBACK, Jesper; NORD, Lars W. (2014). The Effects of Digital Media on Political Knowledge and Participation in Election Campaigns: Evidence from Panel Data. Communication Research, No. 41 (1), p. 95–118.

ENGESSER, Sven; FAWZI, Nayla; LARSSON, Anders O. (2017). Populist Online Communication: Introduction to the Special Issue. Information, Communication & Society, No. 20 (9), p. 1279–92.

ENLI, Gunn (2015). Mediated authenticity. How the media constructs reality. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

ENLI, Gunn; ROSENBERG, Linda T. (2018). Trust in the Age of Social Media: Populist Politicians Seem More Authentic. Social Media + Society, No. January-March, p.1–11.

GABRIELS, Katleen; POELS, Karolien; Braeckman Johan (2014). Morality and involvement in social virtual worlds: The Intensity of Moral Emotions in Response to Virtual Versus Real Life Cheating. New Media & Society, No. 16, (3), p. 451–469.

GERBAUDO, Paolo (2018). Social media and populism: an elective affinity? Media, Culture & Society, No. 40(5), p. 745–753.

GIDRON, Noam; HALL, Peter A. (2017). Populism as a Problem of Social Integration [accessed 17 September 2019]. Access through Internet: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hall/files/gidronhallapsa2017.pdf.

HAMELEERS, Michael; BOS, Linda; de VREESE, Claes H. (2016). “” They Did It”: The Effects of Emotionalized Blame Attribution in Populist Communication.” Communication Studies, No. 1-31, p. 4. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650216644026.

HAZANS, Mihails (2013). Emigration from Latvia: Recent trends and economic impact. In: OECD. (2013). Coping with emigration in Baltic and East European countries, 65–110. OECD Publishing. Interactive [Accessed 14 October 2019]. Access through Internet: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/coping-with-emigration-in-baltic-and-east-european-countries/emigration-from-latvia-recent-trends-and-economic-impact_9789264204928-7-en.

JAGERS, Jan; WALGRAVE, Stefaan (2007). Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium. European Journal of Political Research, No. 46 (3), p. 319–345.

JASTRAMSKIS, D.; ROŽUKALNE, A.; JOESAAR, A. (2017). Media Concentration in the Baltic States (2000–2014). INFORMACIJOS MOKSLAI, No. 77, p. 26-48. https://doi.org/10.15388/im.2017.77.10705

KALSNES, Bente (2018). Examining the populist communication logic: strategic use of social media in populist political parties in Norway and Sweden. Central European Journal of Communication, Vol 12, No 2 (23), p. 187 – 205. 195.

KANTAR (04.06.2018) Interneta vietņu top 5 [Top 5 of the Internet sites]. Interactive [Accessed 16 October 2019]. Access through Internet: https://www.kantar.lv/11499-2/

KIM, Hwalbin., JANG, Mo S., KIM, Sei-Hill., WAN, Anan. (2018). Evaluating sampling methods for content analysis of Twitter data. Social Media+ Society, No. 4 (2), 1-10.

KPV LV. Programma (n.a; n.d.) [Program]. Interactive [Accessed 17 October 2019]. Access through Internet: https://kampiedervalsts.com/programma/.

KRIESI, Hanspeter; PAPPAS, Takis S. (eds.). (2015) European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession. Colchester: ECPR Press.

KUPČS, Edgars; BĒRTULE, Anete (21August 2017). Zolitūdes traģēdijā cietušajiem «Maxima» piedāvā izmaksāt 900 000 eiro [Maxima is offering a payout of 900,000 euros to the victims of the Zolitude tragedy]. Interactive [Accessed 14 October 2019]. Access through Internet: https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/latvija/zolitudes-tragedija-cietusajiem-maxima-piedava-izmaksat-900-000-eiro.a247388/.

LETA. (8 October 2018). 13. Saeimā ievēlētās partijas sāks diskutēt par sadarbību [The parties elected in the 13th Saeima will start discussing the cooperation]. Interactive [accessed 10 October 2019]. Access through Internet: https://www.la.lv/13-saeima-ieveletas-partijas-saks-diskutet-par-sadarbibu.

LSM. (13 May 2018). Partijas KPV premjera kandidāts būs advokāts Gobzems [Lawyer Gobzems will be prime minister candidate for the party KPV] [accessed 10 October 2019]. Access through Internet: https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/latvija/partijas-kpv-lv-premjera-kandidats-bus-advokats-gobzems.a278217/.

LSM (21 June 2018). KPV finansēšanas lietā aizturētajiem piemērots aizdomās turētā statuss [In a case of party KPV funding sustained individuals has been qualified for suspects status]. Interactive [Accessed 12 October 2019]. Access through Internet: https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/latvija/kpv-lv-finansesanas-lieta-aizturetajiem-piemerots-aizdomas-turama-statuss.a282872/.

LULLE, Aija; UNGURE, Elza; BUŽINSKA, Laura (2015). Mediju platformas un diasporas mediji: izpratnes un vajadzības [Media Platforms and Diaspora Media: Understandings and Needs]. Rīga: Latvijas universitāte.

MINISTRY OF ECONOMY (30 Jan 2018). Iekšzemes kopprodukts 2017.gadā sasniedz vēsturiski augstāko līmeni Latvijas brīvvalsts pastāvēšanas laikā [In 2017, the GDP reaches the historically highest level during the existence of indepentent Latvian state]. Interactive [Accessed 12 October 2019]. Access through Internet: https://www.em.gov.lv/lv/jaunumi/17835-iekszemes-kopprodukts-2017-gada-sasniedz-vesturiski-augstako-limeni-latvijas-brivvalsts-pastavesanas-laika.

MOUFFE, Chantal (2005) On the Political. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30521-7.

OTT, Brian L. (2016). The age of Twitter: Donald J. Trump and the politics of debasement. Critical Studies in Media Communication, No. 34:1, p. 59-68.

PANORĀMA (3 May 2016). Nodibina A.Kaimiņa partiju KPV [Establish party of Kaimiņš KPV]. Interactive [Accessed 10 October 2019]. Access through Internet: https://ltv.lsm.lv/lv/raksts/03.05.2016-nodibina-a.kaimina-partiju-kpv.id71321/.

KASPROWICZ, Dominika; HESS, Agnieszka (2019). Some remarks on the comparative experiment as a method in assessing populist political communication in Europe. Central European Journal of Communication, No. 12, no 2 (23), p. 242 – 255.

LEES, Charles (2018). The ‘Alternative for Germany’: The rise of right-wing populism at the heart of Europe. Politics, No. 38(3), p. 295–310.

NEWMAN, Nic; FLETCHER, Richard; KALOGEROPOULOS, Antonis; LEVY, David A. L.; NIELSEN, Rasmus Kleis (2017). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2017. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Interactive [Accessed 12 October 2019]. Access through Internet: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital%20News%20Report%202017%20web_0.pdf.

PARLEMETER 2015 (14 October 2015) Part I. The main challenges for the EU, migration, and the economic and social situation. European Parliament Eurobarometer (EB/EP 84.1). Interactive [Accessed 12 October 2019]. Access through Internet: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/570419/EPRS_STU(2015)570419_EN.pdf.

PICONE, Ike; KLEUT, Jelena; PAVLIČKOVA, Tereza; ROMIC, Bojana; MOLLER HARTLER, Jannie; De RIDDER, Sander (2019). Small acts of engagement: Reconnecting productive audience practices with everyday agency. new media & society, No. 21(9), p. 2010 –2028.

PLUTCHIK, Robert; KELLERMAN, Henry (Eds.) (1980). Emotion: Theory, research and experience, vol. 1. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 9781483270012.

POSTILL, John (2014). Democracy in the age of viral reality: A media epidemiography of Spain’s indignados movement. Ethnography, No. 15(1), p. 50–68.

POSTILL, John (2018). Populism and social media: a global perspective. Media, Culture & Society, No. 40(5), p. 754–765.

RE: BALTICA. (18 August 2018). Kam pieder KPV.LV [Who owns KPV.LV]. Interactive [Accessed 10 February 2020]. Access through Internet: https://www.tvnet.lv/6079671/kam-pieder-kpv-lv.

ROŽUKALNE, Anda (2013). Who Owns Latvia’s Media. Riga: Apgads Zinatne. ISBN 978-9984-879-49-9.

ROŽUKALNE, Anda (14 August 2014). Politiskās preses svaigais zieds SIA “Suņu būda” [Fresh flower of politics’ press – “Doghouse”]. Interactive [Accessed 12 October 2018]. Access through Internet: https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/arpus-etera/arpus-etera/anda-rozukalne-politiskas-preses-svaigais-zieds-sia-suna-buda.a94642/.

ROŽUKALNE, Anda (2017). Is Populism Related Content the New Guilty Pleasure for Media and Audiences? In: KUDORS, Andis.; PABRIKS, Artis. (Eds). The Rise of Populism: Lessons for the European Union and the United States of America. Riga: University of Latvia Press, p. 37 – 56. ISBN 978-9934-18-280-8.

ROŽUKALNE, Anda (2018). Aggressive memories or aggressiveness that changes memories? Analysis of audience reaction to news stories on significant historical events by using the data of The Index the Internet Aggressiveness. In: HANOVS, Denis; GUBENKO, Igors (eds.). Memory – access denied? Political landscapes of memory and inclusion in contemporary Europe. Rīga: Zinātne Publishers, p. 119 – 139. ISBN 978-9934-54-971-7.

SALMELA, Mikko; von SCHEVE, Christian (2017). “Emotional Roots of Right-wing Political Populism. Social Science Information, 56(4), p. 567-95.

SALMELA, Mikko; von SCHEVE, Christian (2018). Dynamics of Right- and Left-wing Political Populism. Humanity & Society, No. 42(4), p. 434-454.

SCHMIDT, Franzisca (2018). Drivers of Populism: A Four- country Comparison of Party Communication in the Run - up to the 2014 European Parliament Elections Political Studies, No. 66(2), p. 459–479.

SKATIES (20 June 2018). Video: Artusa Kaimiņa aizturēšana – no balsojuma Saeimā līdz iekāpšanai KNAB busiņā [Video: Artuss Kaimiņš Detention – From Saeima voting to boarding in KNAB Minivan]. Interactive [Accessed 10 October 2018]. Access through Internet: https://skaties.lv/zinas/latvija/video-artusa-kaimina-aizturesana-no-balsojuma-saeima-lidz-iekapsanai-knab-busina/.

SKDS (August 2018). LATVIJAS BAROMETRS [Latvian Barometer]. Rīga.

STEPINSKA, Agnieszka (ed.). (2019). Populism and the Media across Europe. Central European Journal of Communication. No. 12, no. 2 (23).

STOKES, Bruce (18 September 2018). A Decade After the Financial Crisis Economic Confidence Rebounds in Many Countries. Interactive [Accessed 9 October 2018]. Access through Internet: http://www.pewglobal.org/2018/09/18/a-decade-after-the-financial-crisis-economic-confidence-rebounds-in-many-countries/.

SUITER, Jane; CULLOTY, Eileen; GREENE, Derek; SIAPERA, Eugenia (2018). Hybrid media and populist currents in Ireland’s General Election. Ireland European Journal of Communication, No. 33(4), p. 396–412

TONG, Jingrong (2015). The formation of an antagonistic public sphere: Emotions, the Internet and news media in China. China Information, No. 29 (3), p. 333 – 351.

TUUKKA, Yla-Anttila (2017). Familiarity as a tool of populism: Political appropriation of shared experiences and the case of Suvivirsi. Acta Sociologica, No. 60(4), p. 342–357.

WAHL-JORGENSEN, Karin (2018). Media coverage of shifting emotional regimes: Donald Trump’s angry populism. Media, Culture & Society, No. 40(5), p. 766–778.

WANG, Xiao; HICKERSON, Andrea (2016). The Role of Presumed Influence and Emotions on Audience Evaluation of The Credibility of Media Content and Behavioural Tendencies. Journal of Creative Communications, No. 11(1), p. 1-11.

WIRZ, Dominique. S; WETTSTEIN, Martin; SCHULZ, Anne; MULLER, Philip; SCHEMER, Christian; ERNST, Nicole; ESSER, Frank; WIRTH, Werner (2018). The Effects of Right-Wing Populist Communication on Emotions and Cognitions toward Immigrants. The International Journal of Press/Politics, No. 23(4), p. 496–516.

de VREESE, Claes; H., ESSER, Frank; AALBERG, Tori; REINEMANN, Carsten; STANYER, James (2018). Populism as an Expression of Political Communication Content and Style: A New Perspective. The International Journal of Press/Politics, No. 23(4), p. 423–438.

WOHN, Yvette D; BOWE, Brian J. (2016). Micro Agenda Setters: The Effect of Social Media on Young Adults’ Exposure to and Attitude Toward News. Social Media +Society, No. January-March, p.1-12.

WOLKENSTEIN, Fabio (2015). What can we hold against populism? Philosophy and Social Criticism, No. 41(2), p. 111–129.

ZULIANELLO, Mattia; ALBERTINI, Alessandro; CECCOBELLI, Diego (2018). A Populist Zeitgeist? The Communication Strategies of Western and Latin American Political Leaders on Facebook. The International Journal of Press/Politics, No. 23(4), p. 439 –457.