Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2022, vol. 93, pp. 42–61 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2022.93.60

PR-Message Analysis as a New Method for the Quantitative and Qualitative Communication Campaign Study

Artem Zakharchenko

Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine

artem.zakh@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3877-8403

Abstract. Communication practitioners often seek fast quantitative and qualitative analysis of the information campaign outcomes in the media space. Such analysis is required by PR departments of commercial brands, by political technologists, and by experts in information wars and ideology.

A new approach for the analysis of information campaign outcomes is introduced in this paper. Using PR messages as a category for analysis of media coverage of information campaigns provides a framework for credible efficiency evaluation, as well as for the deep analysis of the factors contributing to achievements or failures. This method allows the campaign organizers to understand what message it is better to disseminate in the media. In other words, through the messages of what kind the opinion of the campaign initiator or their opponents is conveyed to the media audience more effectively.

We consider a message to be a judgment in which an object or predicate relates to the substance of the information campaign. Using it as a category for analysis and several types of the message as subcategories of analysis allows us to combine qualitative and quantitative approaches and, at the same time, avoid many restrictions of content analysis, discourse analysis, and narrative analysis.

We show how the method works on the example of the failed information campaign that promoted a lobbyist and populist bill in the Ukrainian parliament. We showed that only our method could explain the reasons for its failure and provide the best way to improve the communication.

Keywords: information campaigns; content analysis; discourse analysis; PR message; information attack.

Viešųjų ryšių pranešimų analizė kaip naujas kiekybinio ir kokybinio komunikacijos kampanijos tyrimo metodas

Santrauka. Komunikacijos specialistai dažnai siekia greitos kiekybinės ir kokybinės informacinės kampanijos rezultatų analizės žiniasklaidos erdvėje. Tokios analizės reikalauja komercinių prekių ženklų viešųjų ryšių departamentai, politikos technologai ir informacinių karų bei ideologijos ekspertai. Šiame straipsnyje pristatomas naujas požiūris į informacinių kampanijų rezultatų analizę. Viešųjų ryšių pranešimų naudojimas kaip informacinių kampanijų žiniasklaidos analizės kategorija suteikia pagrindą patikimam efektyvumo vertinimui, taip pat nuodugniai veiksnių, prisidedančių prie pasiekimų ar nesėkmių, analizei. Šis metodas leidžia kampanijos organizatoriams suprasti, kokią žinią geriau skleisti žiniasklaidoje. Kitaip tariant, per kokio tipo kampanijos iniciatorių ar jų oponentų pranešimus nuomonė efektyviau perduodama žiniasklaidos auditorijai. Mes manome, kad pranešimas yra sprendimas, kuriame objektas ar predikatas yra susijęs su informacinės kampanijos esme. Naudodami jį kaip analizės kategoriją ir kelių tipų pranešimą kaip analizės subkategorijas, galime derinti kokybinius ir kiekybinius metodus ir tuo pačiu metu išvengti daugelio turinio analizės, diskurso analizės ir naratyvinės analizės apribojimų. Mes parodome, kaip šis metodas veikia žlugusios informacinės kampanijos, kuri Ukrainos parlamente propagavo lobistinį ir populistinį įstatymo projektą, pavyzdžiu. Mes atskleidėme, kad tik mūsų metodas gali paaiškinti jos žlugimo priežastis ir suteikti geriausią būdą, kaip pagerinti komunikaciją.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: informacinės kampanijos; turinio analizė; diskurso analizė; viešųjų ryšių pranešimas; informacinė ataka.

Received: 2021-06-03. Accepted: 2022-02-02.

Copyright © 2022 Artem Zakharchenko. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

In the era of information warfare, PR communication practitioners are constantly dealing with the increasingly complicated structure of information campaigns. At the same time, they have to respond to communication challenges faster, take quicker decisions on improving the campaign plan, having considered the opponents’ actions and changes in the external information background. This task is urgent both for PRs of commercial brands and parties to the political process and ultimately for the strategic communication of countries, in particular, in the context of information aggression.

The growing complexity of communication is associated primarily with the trend for narrow targeting of PR campaigns at different segments of the target audience which became possible due to the development of internet communication and Big Data (Nai & Maier, 2018). The communication channels, opinion leaders, and messages to be delivered are selected for each particular segment.

The above trends make the efficiency analysis of communication campaigns more complicated as well. This fact underpins the relevance of the study.

The main hypothesis of our study is that the use of PR messages as a category for communication analysis of the information campaign helps a researcher to understand the circumstances of PR campaigns, which is more difficult to achieve using other methods. The communicators for whom these studies are made thus receive the material for immediate adjustment of their PR tactics and strategies.

As defined by D. Du Plessis, “PR-message is the information which the organization wishes to convey to its relevant publics by way of the public relations programme. This message … should be general enough to encompass all facets of the programme, but could also be divided into various secondary messages” (Plessis, 2000). Messages are disseminated in the media according to the media logic (Altheide & Snow, 1979) or employing the planted stories, and also in social networks according to the social media logic (Dijck & Poell, 2013) or, again, by writing paid posts by opinion leaders, through bot farms used to write comments with a particular message, etc.

Therefore, the goal of our study is to develop the methodology that would allow for efficient use of PR message as an analysis category as well as to define the pros and cons of this methodology. The study object is a pool of PR messages used in commercial, political, or strategic PR campaigns, while the focus of the study is the possibility to use these messages as an analysis category.

2. Literature review

Most of the so-called media effects theories have no quantitative tools (Laughey, 2008). Therefore, the problem of impact measurement is not closely connected to this scientific discourse and is mostly developed by practitioners: media critics or PR experts. They distinguish between effects and efficacy, considering that the second term stipulates the goal and the measure of its achievement (Rice & Atkin, 2009).

There are several frameworks for this measurement, specific for the areas of practitioners. Namely, the most known framework for the evaluation of the PR campaign efficacy is Barcelona principles (AMEC | International Association for the Measurement and Evaluation of Communication, 2020). It stipulates that the measurement should identify outputs (the evaluation of how active was the campaign), outcomes (the change in consciousness/behavior of the targeted audience (Austin et al., 2006)), and potential impact (long-term social changes).

In social projects impact evaluation, the Knight foundation matrix is one of the most known. This is the matrix of indicators of five categories: news, voice, action, awareness, capacity (Knight foundation, 2011). F.Napoli matrix puts the spotlight on engagement, considering it as the measure of the social impact (Napoli, 2014). Another model named CoMTI seems to be the most overarching in terms of the set of indicators used for the evaluation (Diesner et al., 2014).

At last, there are a lot of works focused on the identification of motivation, outlook, and ideological foundations of communication actors. Typically, such identification work is carried out by researchers not associated with the PR campaign organizers. A lot of this kind of work is carried out, for example, in the public sector: for the protection of human rights, environment, opposition to political propaganda, in particular, (Syme et al., 2000; Yuzva, 2015) and others).

It is the output that our paper is focused on. Evaluating the PR output, as stated by D. Wilcox, testifies to the high performance and creativity of the PR expert, it is an excellent criterion for the assessment of his work (Wilcox et al., 2003).

The measurement of output implies a set of methods. While outcome and potential impact are usually measured by sociological methods like focus groups, in-deeps interviews, etc, the toolkit for output evaluation is different.

In the classic work on arranging and conducting information campaigns, E. Austin and B. Pinkleton name top output evaluation methods: documentation of messages placed in the media (73% of campaigns covered by their research), documentation of participation in campaign events or activities (62%), documentation of the number of campaign events implemented (52%), and content analysis of messages placed (52%). The most advanced output evaluations also use discourse analysis or narrative analysis. But classic content analysis, as a rule, is more common compared to them and better suited for automation.

The set of indicators used in these evaluations is usually too poor. In particular, Austin and Pinkleton (Austin et al., 2006, pp. 164–166) state that content analysis is commonly used by PR practitioners to study the tone of the media coverage or the balance of media representation of an organization and its competitors, dynamics of media coverage in time, or the extent of media coverage of different audiences. They advise using the following units of analysis: positive, negative, or mixed stories about the organization, specific aspects of corporate identity, mentioned in publications, mentions of corporate programs in media, mentions of competitors.

Alternative methods used to study PR campaigns mainly relate to the field of discourse analysis. As C. Daymon and I. Holloway note (Daymon & Holloway, 2010, p. 68) in their fundamental work “Qualitative Research Methods in Public Relations and Marketing Communications”, discourse analysts go beyond the analysis of the text to determine how the language was used, why, when, under what conditions and by whom. In the process of analysis, it is necessary to find out the relationship between the text, its authors, and consumers, and also the social environment in which the creation and consumption of the text occur; what are other (and better) ways to organize this interactive communication. In this case, the units of analysis are large fragments of text containing value judgments and language patterns rather than words or phrases (Daymon & Holloway, 2010, p. 173).

There are quite a few modifications of this method aimed at a certain narrow aspect of research. For example, the linguistic and ideological analysis of political discourse, according to (van Dijk, 1997), reveals what basic ideologies determine the political discourse, in what linguistic constructions these ideologies come out, and makes it possible to establish what ideological principles, in particular such “noxious” as racism or Nazism, are hidden in the minds of various politicians.

The linguistic theory of argumentation, in which the value arguments used by politicians are the analysis category, is close to the above method. According to this theory, information or propaganda campaigns can be built around discussions in which one side uses for example arguments based on the concept of justice, and the other side on the concept of freedom (Baranov, 2001). As we see, the notion of the concept and arguments is close to the definition of primary and secondary PR messages mentioned at the beginning of the paper but the latter is more universal category suitable for use not only in politics but also in business discourse.

Another well-known technique suitable for describing communication campaigns is narrative analysis. Inherently, this is a qualitative rather than a quantitative analysis, which implies the active involvement of the analyst’s personal experience. This analysis is focused on identifying various aspects of stories, narratives that occur in various aspects of life including media texts.

According to the classification by (Riessman, 2002), it is divided into several subcategories. The first is a thematic analysis, where the content of the narrative is examined rather than its form. The opposite is structural analysis, where emphasis shifts to the telling process itself. The third method is an interactional analysis. Here the emphasis is on the dialogic process between narrator and listener, the process of co-construction of new meanings collaboratively by narrator and listener. Finally, there is a performative analysis where the storytelling is seen as a performance that actively changes the world.

All the above modifications of this analysis have been used repeatedly to study public campaigns and propaganda. The recent cases include the studies of propaganda of terrorism in Islamic English-language magazines (Ingram, 2017), the analysis of the influence of US state propaganda on media (Vincent, 2000), the research of campaigns for skin cancer prevention (Garvin & Eyles, 2001), etc.

A separate subcategory is the so-called analysis of political narrative, proposed by E. Roe (Roe, 1994). The area of his focus is narratives describing difficult policy dilemmas. According to this technique, the researcher determines the dominant narrative, counter-narratives, and then creates a meta-narrative derived from them, which is meant to offer solutions to the conflicts in question. A similar technique is also sometimes used in the study of PR campaigns, in particular, initiatives to involve the public in solving environmental problems (Hampton, 2009).

As we can see, the above cases of discourse and narrative analysis application cannot answer the questions posed at the beginning of the paper as far as the target of their analysis is not the tools consciously used by PR experts. Their main focus is political or propaganda study, which is not always similar to PR communication study. However, the content analysis operates with more common PR categories, these are usually the simplest categories like tone or brand voice that cannot show anything about the communication efficacy. Namely, the positive tone of message may be too general and helpless in promoting core values.

So, deep quantitive analysis of the output efficacy is possible only by using the meanings of the campaign. And the main instrument of these meanings delivery to the recipient is the PR message. “Practitioners saw well-crafted key messages as having the power to cut through the environment to achieve specific outcomes and positively position organisations,” this is the finding of the paper that examined the most successful campaigns (James, 2011). So, the message is the bridge from output to outcome. Variations of the message led to the change in consumers’ responses (Hongcharu, 2019). We have not found any metrics that allow using quantitive approach to message evaluation.

There is some very interesting idea of evaluating the effectiveness of commercial brand communication proposed by Kazokiene and Stravinskiene (Kazokiene & Stravinskiene, 2011), who suggest the following key evaluation criteria for PR effectiveness: simplicity, informativeness, truthfulness, ethicality, novelty, and expedience of the communication message, the attractiveness of the media where the message is placed, the attractiveness of message presentation and a speaker. But this work doesn’t offer any specific measures.

So, there is a need for the method proving precise evaluation of the PR campaign output.

3. Grounds for the proposed methodology

3.1. Requirements for the method

Let us be clear about the requirements for this method.

First of all, it should be detailed enough to understand which message is disseminated better and why. That is, through the messages of what kind the opinion of campaign initiator or his opponents are conveyed to the media audience more effectively. None of the methods listed in Section 2 gives the answer to this question. There are a lot of attempts on the part of PR communication practitioners to find the answer to the question using purely qualitative but not quantitative approaches (see, for example, (Agility PR Solutions, 2017)). Though only the quantitative approach would be quite sufficient evidential.

Secondly, it should accommodate the point that not only the brand itself can spread the promotion or protection messages, but also many of its “brand defenders” (Ammann et al., 2020). Similarly, the attack messages can often come not from a direct opponent, but from a wide range of speakers, some of whom were initially involved in the campaign, and others joined the process of message dissemination later, deciding that it may bring them certain benefits. In the end, both sides can involve opinion leaders in social networks that write paid posts, bots who distribute respective comments, buy experts who will give unfair comments in the media. As a result, the usual calculation of the number of publications containing the standpoint of the brand or their opponent gives an incomplete picture of the information campaign.

Third, the method should combine a quantitative approach for measurement and a qualitative for the explanation of the communication processes and patterns. Mixed-method communication research that combines qualitative and quantitative practices is one of the trends of modern discourse (Thurman, 2018).

Quantifying the PR message helps us to meet all these requirements because we may find this message without its connection to a speaker, we may compare the spreading of the messages through the different channels and apply qualitative analysis to the results of the quantitative one. Thus, we may focus on tools, communication channels, ways to argue the standpoints, response to them by media and audience, peculiarities of the behavior of numerous communication actors, including the media, media attention to the messages and their speakers.

3.2. Special aspects of the analysis of information campaign coverage in media

Using PR messages as an analysis category presents some challenges to us.

First, these studies involve the content analysis tools that are used for the sampling and coding process. The sampling requires the usage of automatic monitoring systems to define primary sources of certain messages dissemination. It is necessary to analyze the totality of mentions in order not to skip the story in which the message appears for the first time. However, this task is often not difficult if methods of automatic text analysis or at least methods for searching information in the database are used.

The defined sample does not normally require usual procedural elements of document analysis, like, for example, verification of documents authenticity or motivation for their creation, because texts are obtained, as a rule, from automated monitoring databases, and all of them are created as a part of ordinary activities of media organizations.

The number of publications that usually contain the messages of information campaigns in the Ukrainian media space, normally, is not excessively large, and so, the manual coding is appropriate. Since the middle of 2016, for a five-year study of information campaigns by the Center for the Content Analysis, it has been estimated that this number usually ranges from 70–80 to 2000–3000 media publications. In case the campaign actively engages social networks, the number of messages is often 10 to 20 times larger.

If the sample still needs to be narrowed, it is convenient to use the list of the most influential media: TOP-100, TOP-50, etc., selected based on expert opinions, or a sample of posts that have reached the highest benchmark of Facebook interactions (likes + shares + comments).

Second, the most difficult in methodological terms is the detection of the very messages. PR communication practitioners usually do not apply the systematic approach when writing messages and characterize this process as “creative”. With this approach, it would be very difficult to identify which units of text are PR messages and which are not. However, the creation of messages can be quite formalized. In accordance with the principles of classical logic, any PR message is a judgment. That is a combination of the subject, predicate, and link word. It is to be recalled that the subject (S) is what is said in the judgment, the predicate (P) is a certain statement about the subject of thought, and the link word is a reflection of the connection existing between S and P.

At the time of encoding, the messages shall be deemed to be all judgments that are available in the sample of media messages where the following items occur to be a subject or predicate:

a) one of the parties to the conflict or their aspects,

b) the subject of the conflict or its aspects,

c) external circumstances that significantly affect the course of the conflict.

Before the encoding starts the list of aspects or external circumstances should be determined by experts based on the nature of the campaign, the analysis tasks, and the required accuracy of measurement, but it can be supplemented in the process of encoding.

Since messages are not always present in media texts in the form of definitive phrases, latent encoding should be applied, that is, the encoder should reveal not only explicit but also hidden messages. In addition, a list of analysis sub-categories – talking points used by the parties – is formed by the searching method, that is, it is selected from the texts included in the sample.

Third, after obtaining the quantitative data, the qualitative part of the analysis starts, which includes approaches of discourse analysis and narrative analysis. The dissemination of each message and the features of a whole campaign should be outlined by the analyst familiar with the specificity of the campaigning procedures in the particular communication space. And more detailed categorization of the PR messages contributes significantly to this analysis.

3.3. Detailed analysis of detected PR messages and data processing

Even more room for conclusions regarding the course of the information campaign is provided if to divide the category of the message into subcategories by several parameters. These may include:

1. Messages of different types of communication. In terms of this criterion, the messages can be divided into:

- Messages for promotion of a business or political brand, its goods, services, and ideas. These messages are aimed at strengthening the advertising communication; they typically contain the information of brand advantages.

- Attack messages. Here an organized spreading of negative information about the brand or its aspects and initiatives is supposed.

- Defense messages. They are supposed to spread information that neutralizes the attack messages, restoring the positive perception of a brand.

- Counterattack messages. They are supposed to spread negative information on the attack initiator, describing him as a poor source of information, or simply forcing it to abandon the attack under the threat of losing its own good repute.

- Expert opinion about the course of the information campaign. They characterize the circumstances in which the information campaign is conducted, the methods of conducting it, its causes, consequences, etc.

It should be noted that a message cannot be referred to one of the subcategories listed here based only on the definition of judgment author. After all, for example, attack messages are often unintentionally spread by their victim, and the defense messages are spread by external experts or loyal consumers.

2. Importance of messages:

- Primary: messages which are key for a particular PR campaign

- Secondary: messages which are parts of a primary message or the arguments in favor of it

3. Messages regarding various aspects of a campaign. For instance, in cases where the object of the campaign is a conflict, the subject of a judgment can be one of the following:

- Messages regarding the substance/situation of the conflict, its prerequisites, current, and future development

- Messages regarding the content/situation of alternative (for example, illustrative or hidden) conflict

- Messages regarding a person participating in a conflict, his/her past, present, and future

- Messages regarding the external situation in which the conflict is developing

4. Ideological values on which the messages are based. They can be divided according to various parameters as in the study above cited (van Dijk, 1997). For instance:

- Liberal values

- Traditional values

- Social values

5. By initiation. Usually, this parameter is used for messages in which the stand of the organization on a particular issue is present. Such active references are divided into:

- Proactive. The messages that appeared on the initiative of the organization and, probably, are stated in its PR strategy.

- Reactive. The messages that appeared as a reaction to external challenges: information attacks, information crises, incidents, natural disasters, unexpected honorable distinctions, etc.

6. By the factors of reputation, relationships, and other important for the organization parameters. Several sets of parameters are widely used. For example, RepTrack (Reputation Institute, 2020), which divides the company’s reputation into 7 factors: products & services, innovation, leadership, performance, citizenship, workplace, the formation of which is in that or other way influenced by media messages. Similarly, the reputation of the relationship with the company is divided into factors: interaction, trust, commitment, pleasure, mutual benefit, social responsibility (Hon & Grunig, 1999).

Thus, obtained quantitative data can be processed using the discourse analysis and narrative analysis techniques described above, in particular, to find out how the media react to messages, in what way these messages interact with social media audience, etc.

Table 1 illustrates the features and shortcomings of various analysis methods in terms of studying information campaigns, particularly, the specificities and benefits of the proposed method.

Table 1. Comparison of characteristics of and options provided for by different analysis methods in the context of information campaign study

|

Method |

Analysis |

Potential analysis goal when applied to PR campaigns analysis |

Key analysis categories when applied to PR campaigns analysis |

Method Restrictions in the PR campaigns |

|

1. Content analysis |

Documents through which the communication within the campaign was carried out |

Measuring frequency of brand mention in the media, the number of media that published the standpoint of the company, the tonality of brand mention in the media based on the results of the campaign. |

Names of brands, surnames of speakers, press office quotes. Also, the following analysis techniques are used: tonality definition, the context of mentioning, etc. |

The communication process is left out by the method, only its results are studied: specific documents.

|

|

2. Discourse analysis |

Discussion communication in the political, ideological, business aspects. |

To identify the format of relations between the communication actors, the context of communication, the response of communication consumers and its reasons, and hence the effectiveness of communication. |

Value judgments in communication texts, language patterns used, non-verbal communication tools, text metadata |

The tool for quantitative evaluation of PR communication has not been developed. It cannot be applied to non-discussion communication in which one side participates. |

|

2.1. Linguistic and ideological analysis of political discourse |

Discussion communication between carriers of different political and ideological views, for example during parliamentary debates, information wars. |

To identify the ideological guidelines used by communicators. |

Lexical constructions used by communicators. |

It does not set the objective of measuring the effectiveness of communication. It cannot be applied to non-discussion communication in which one side participates. |

|

2.2. Linguistic theory of argumentation |

Discussion communication between carriers of different political and ideological views, for example during parliamentary debates, information wars. |

To identify the ideological guidelines used by communicators. |

The reasons used by the communicator to prove their opinion. |

It does not set the objective of measuring the effectiveness of communication. |

|

3. Narrative analysis |

Texts and other types of communication are used in propaganda and PR campaigns. |

To identify the key topics raised by communicators in their stories, images of characters, communicative channels used for narration, rate of interactivity during the narration, and the effectiveness of communication through these stories. |

Plot, characters of the narrative, topic of the narrative, narration formats, narrators |

It does not set the objective of measuring the effectiveness of communication. |

|

3.1. Analysis of political narrative |

Texts and other types of communication are used in political discussions. |

To define the prospects for finding a common language, to create a meta-narrative, which would combine the narratives of two parties |

The plot, characters of the narrative, topic of the narrative, communication tools |

It does not set the objective of measuring the effectiveness of communication, inapplicable for non-political topics |

|

4. Proposed quantitative analysis of information campaigns message spreading |

A set of media messages that participated in information campaigns. |

Identify tools, communication channels, ways to argue the standpoints of the parties, response to them by media and audience, peculiarities of the behavior of numerous communication actors, including the media, media attention to the messages, and their speakers. |

PR-messages. Subcategories described in par. 3.3 are also used. |

It cannot always answer the question of how the news affected the recipients of media texts, although it allows understanding how many and what users contacted PR messages. |

Source: Own processing

4. Results and discussion

The proposed methodology was tested on the several hundred information campaigns studied during five-year work by the analytical department of the Center for the Content Analysis, including campaigns of commercial brands, communications in the internal Ukrainian political space, and communication cases within the framework of the Ukraine-Russian information war.

One of the examples we have chosen to illustrate how the methodology works is the PR campaign involving the Ministry of Economy of Ukraine, a facilitator of the ProZorro public procurement system. Its opponent was the Radical Party of Oleh Lyashko. It was the patriotic populists’ party that had a small faction in the Verkhovna Rada. This faction lobbied for the adoption of Bill No. 7206, the so-called “Buy Ukrainian, Pay to Ukrainians” Bill. It provides for preferences for the so-called “domestic producers” in the public procurement procedure.

This case is a fair demonstration of the method capabilities as far as both parts of the discussion were almost equally active, at the same time they used different tactics. Both opponents were the actors of domestic Ukrainian politics, without the interruption from external agents. Also, this campaign finally involved numerous actors who initially were not part of the discussion.

4.1. Political background of the campaign

Since the Revolution of Dignity in 2013–2014, remarkable changes took place in Ukrainian politics, as well as in communication (Gruzd & Tsyganova, 2015). In 2013-2016 country faced the rise of civil control over the authorities and civil society took up some of state functions like the combat of Russian propaganda (Sienkiewicz, 2016). Civil rights movement pervaded very different areas like women’s activism (Lokot, 2018; O. Zakharchenko et al., 2020) or demand for reforms (Ronzhyn, 2016).

So, before the case we look into, any non-market or corrupt initiative on behalf of the team of the previous President, Petro Poroshenko, turned into a public loss of face primarily for the authorities itself. However, the authorities usually ignored that fact. It either left its decision in force, as in the case of the notorious “Rotterdam +” coal price formula to calculate the price for electricity which was heavily criticized by experts and politicians (Gerus, 2016), or made some concessions under the pressure of international partners as in the situation with increased control over the NABU in December 2017 (Karmanau, 2017).

This circumstance made the Ukrainian political process quintessentially different from the political processes of neighboring countries. Undemocratic populist decisions of the ruling political powers there only raised their rating among the conservative part of the population giving thus the opportunity to ignore the protest actions of the liberal minority.

Obviously, after the Revolution of Dignity in Ukraine, the politicians often took populist decisions. A good example was an increase in the minimum wage on the initiative of prime-minister V. Groysman at the end of 2016. Yet, this populism was related to the wasteful spending of budgetary funds and did not intend to strengthen the power or obtain corrupt income. However, in post-Maidan Ukraine, “Buy Ukrainian, Pay to Ukrainians” Bill was one of the first legislative initiative criticized by the public for corruption, which at the same time managed to raise the rating of its initiator. At that time, the similar situation occurred if only to the repeated extension of the moratorium on the agricultural land sale.

The authors of the Bill included not only Radical Party representatives but also deputies from Petro Poroshenko Block faction, with the Prime Minister of Ukraine, Volodymyr Groysman, expressing his cautious support for the Bill. It is important to note that the campaign was conducted long before the latest elections in Ukraine and the rise of Volodymyr Zelenskyi’s populism in the form of non-agenda ownership (A. Zakharchenko et al., 2019) and rise of polarization in the active part of the society (A. Zakharchenko & Zakharchenko, 2021).

The information campaign for the Bill was launched in the media on October 17, 2017. Its main public defenders included Radical Party representatives, O. Lyashko and V. Halasiuk, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and some other national industry associations. Initially, the Bill was promoted on Facebook, as well as on Ukraina TV-Channel and in the Segodnya newspaper (owned by R. Akhmetov, a former member of the Party of Regions, now considered one of the sponsors of the Radical Party), with further discussion sweeping all the top media.

The Bill was battered by representatives of ProZorro, Kyiv School of Economics (KSE), Reanimation Reform Package public organization, anti-corruption activists, and some politicians. The core of the criticism was that the Bill did not really give preferences to all domestic producers but creates a non-competitive environment in public procurement, contributes to inflation, and violates the international obligations of Ukraine.

4.2. Research Design

The timeframe for our research study was the period from October 17 to December 31, 2017, that is, from the campaign launch to the end of its active phase. The first sample includes all media messages gathered by monitoring system Mediateka containing mentions of the bill in the TOP-100 of Ukrainian Internet media (the standard list used in many studies by the Content Analysis Center (Центр контент-аналізу, 2018)), as well as on television, radio and in print. The second sample includes Facebook posts or reposts with the mentions of the bill that have in total not less than 50 interactions including “likes”, shares or comments, gathered by monitoring system YouScan. Thus, the first sample consisted of 660 publications and the second of 376 Facebook posts. The study estimated the number of contacts of media messages and Facebook posts with the audience based on the use of public metrics for Internet media attendance and newspaper circulation, allowing for the likelihood of each of the articles being read and for the data on the number of TV programs viewers according to the available studies of the TV panel. Finally, the breakdown of media by categories (mass, “high quality”, politically committed, media with a weak reputation) was also based on a classification standard for the analyses conducted by the Content Analysis Center (Центр контент-аналізу, 2018).

This research design allows us to focus on the publications of the most influential media and the most popular posts in social media.

4.3. Research Data

Figures in this chapter contain some specific information about speakers, media brands, etc., nevertheless, it will be too long to familiarize readers with all these items. This information is included just for the illustration of the frame of the analysis, for there is no need for the reader to go into details of the subject.

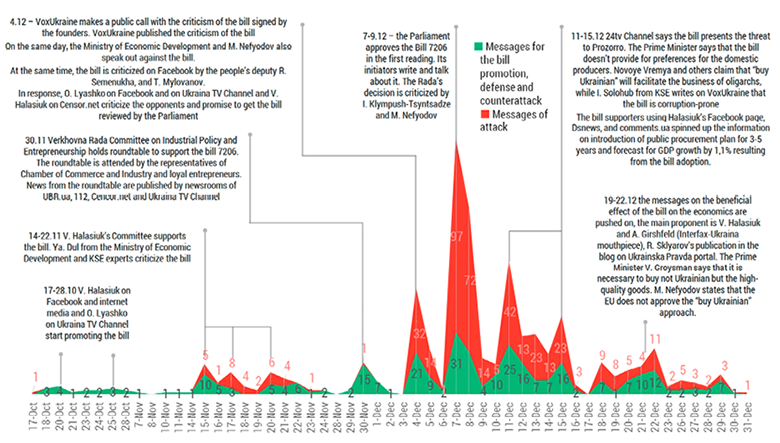

Fig. 1. Dynamics of spreading the messages on the bill promotion, attacks against it, messages of defense, and counter-attacks. The number of publications with respective messages in both samples. Source: Own processing.

Promotion of the bill on media started in October, though the intensive information attacks against it on behalf of the Ministry of Economics appeared only in early November when it became clear that there were good chances for its adoption in the Verkhovna Rada. In response to the criticism, the Radical Party began a very powerful defense campaign and simultaneously counter-attacked the critics of the bill (see Fig.1). Eventually, on December 7, the bill was passed in the first reading but next week in the period from December 7 to December 15, the number of publications concerning the bill reached its highest point. The purpose of the Ministry of Economy was to prevent the adoption of the bill on second reading.

The goal was achieved at least for a while: as of March 2018, the bill was not submitted to the Parliament for consideration in the second reading. Our study shows the way the ProZorro team managed to achieve this result and what side effects it caused.

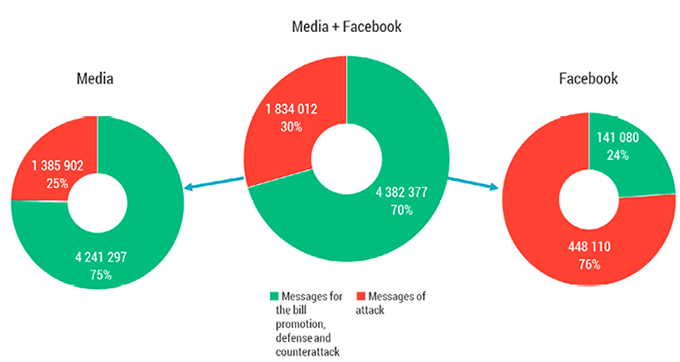

If to compare the number of contacts of the messages from bill supporters and opponents with the audience, it turns out that the number of messages of the first category was much greater (Fig.2). Anyway, this preponderance was provided, primarily, by virtue of television, while on Facebook, just the contrary, most of the contacts with the audience were received by the messages from the ProZorro team and its supporters.

ProZorro’s PR experts have resorted to a strategy to counter the bill, which has already worked fine repeatedly. They opt for the so-called “high-quality” media – the Ukrainska Pravda, Novoe Vremya, Liga, etc. – as their target audience. It is the readers of these media, including, in particular, Verkhovna Rada deputies and market experts, who usually determine the future of such initiatives. The messages chosen for them were appropriate, aimed at rational and ironic comprehension of the proposed changes in legislation.

Fig. 2. Comparison of message prominence. The number of contacts with the audience by messages in the TOP-100 internet media, on the television, radio, printed media sample and on Facebook, 17.10-31.12.2017. Source: Own processing.

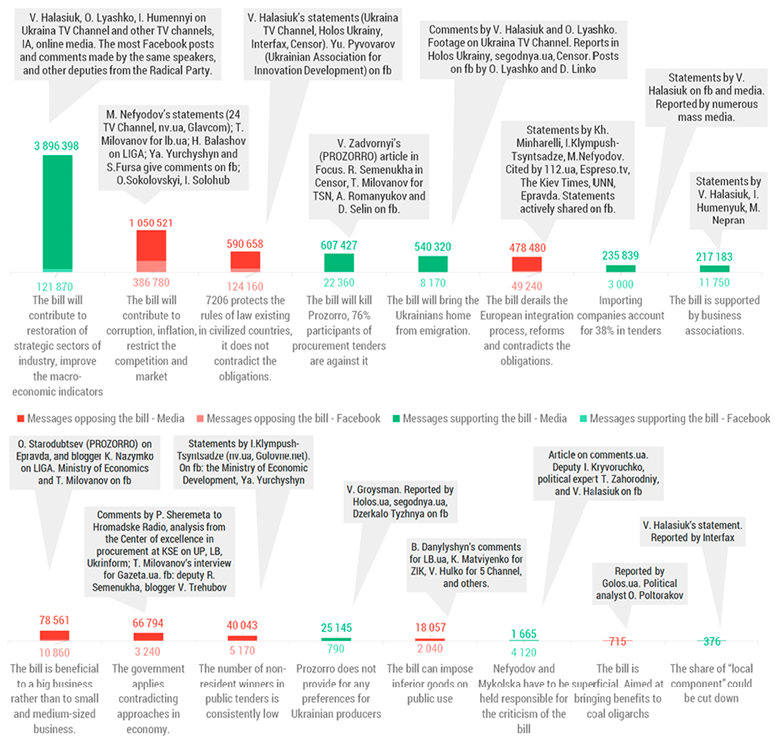

As can be seen in Fig. 3, the most shared messages associated the adoption of the bill with the economic welfare of the country and consisted of typical populist rhetoric: they promised employment, high salaries, return of the Ukrainians from emigration, etc. While the message of the bill critics appealed to the fight against corruption, to one of the most intensely promoted achievements of reformers – the ProZorro system – as well as to the values of private entrepreneurship. The liberal values to which the information attack initiators appealed have a smaller circle of supporters in Ukraine as compared to the values contained in messages of the bill authors and the carriers of these values naturally make up the audience of “high-quality” media and are often among the active Facebook users.

Fig. 3 Number of contacts with the audience by messages of different parties to a conflict in media and Facebook samples. Source: Own processing.

This example clearly illustrates why a quantitative analysis of message spreading provides more accurate information on the effectiveness of communication than traditional evaluation of the exposure of a communicator position in the media or evaluation of the use of certain worldview attitudes. After all, we see that each of the two sides of the campaign used more than a dozen different secondary messages and their speakers were not only representatives of the two main opponents – the Radical Party of Oleh Lyashko and the Ministry of Economics – but also many other stakeholders, such as industry associations, independent economic experts, officials and people’s deputies, well-known volunteers and others. Consequently, no other traditional analysis method would provide so accurate evaluation of the campaign output.

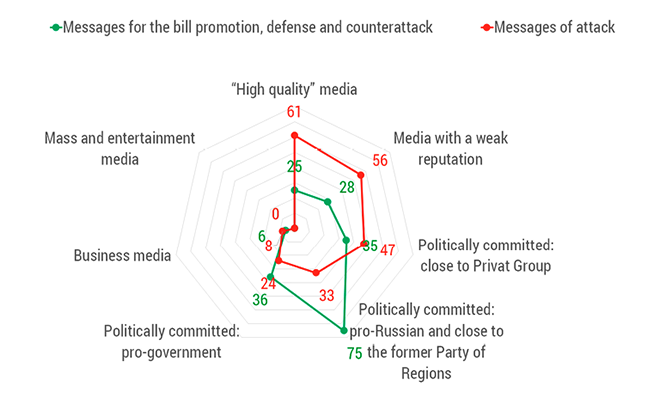

As a result, the spreading of messages in media of different categories was respective (Fig. 4). The most attention to the message of the information attack was given by the “high quality” and business media. They were joined by the media close to the Privat Group of Ihor Kolomoyskyi, and part of the media with a weak reputation. The remaining categories were more supportive of the legislative initiative proposed by the Radical Party, especially the category of media close to the former representatives of the Party of Regions.

Such distribution of attention can be explained by two reasons. On the one hand, it is likely that Akhmetov’s media group, as well as pro-government media, traditionally supported O. Lyashko. On the other hand, the messages of both sides were chosen in such a way that they were interesting to these particular groups of media.

Fig. 4. Attention to the messages of both sides from the media of different categories: number of media publications containing the stated messages. Source: Own processing.

4.4. Campaign Results

The choice of messages determined the results of the campaign for both sides. On the one hand, the final adoption of the bill was suspended. The win of the ProZorro team in the struggle for the output in the segment of “high-quality” media probably contributed to this outcome.

On the other hand, this campaign harmed the public image of M. Nefyodov and his team among the audience of mass media. V. Halasiuk affronted his opponents calling them “grant eaters, compradors and even some respectful economists deceived by the former”, accusing them of “conducting propaganda against domestic industry”. Aired on the Ukraina TV Channel Lyashko said: “Who opposes paying to the Ukrainians? Only those who want the dollar to rate 50 or 100 hryvnias!”

It can be assumed that Nefyodov does not care about his image among the viewers of the Ukraina TV Channel. After all, the influence of this part of the population on politics is restricted to elections, and the Deputy Minister has not yet announced his intention to run for any elective office. However, in the period before the Presidential Election 2018, the Ukrainian authorities will increasingly have to take into account the attitude of voters to various issues on the political agenda. If the opponents manage to convince the mass audience that the reform team in the Ministry of Economics is harmful, this can further inhibit the reforms. M. Nefyodyov has already felt the effects of the described information campaign – on January 14, 2018, the Federation of Employers of Ukraine began lobbying for his dismissal from the position of Deputy Minister.

Our analysis shows that one of the solutions to this problem could have been the selection by the ProZorro team of other messages aimed not only at “high-quality” but also at the mass audience. For example, instead of combating the populist slogan, they could have taken advantage of it, e.g., by declaring that assistance to the domestic producer is needed but not in the corrupt format as proposed by the Radical Party. Such a message would be understandable to a broad media audience.

4.5. Discussion

The above example shows that our method of PR messages analysis meets all the requirements we set at the beginning of Section 3. This is the only method that could explain the reasons for the failure of the bill promotion campaign.

First, this approach helps to determine which message is better for each communication channel that was selected for the campaign. Repeating and updating the most successful messages may contribute to their better dissemination. That was used by bill opponents who asked different speakers to repeat the message that the bill will contribute to inflation and corruption, and reached a huge audience, particularly in social media.

Second, we compared not only the messages of the very opponents but also numerous bystanders who adhered to one of the parties. Representatives of different ministries, popular bloggers, NGOs, and industrial groups contributed to the promotion of the campaign messages. Our method affords to account for all these kinds of contribution.

Third, qualitative analysis on the quantitative data helped to show the patterns of the messages dissemination, the origin of the campaign dynamics, and, finally, to clarify the outcome of the campaign.

Other methods mentioned in the paper could not help to receive such results. Traditional content analysis cannot cover the messages of all participants of the discussion or address the issue of the best promotion message. Traditional discourse and narrative analyses have no quantitative scales. Linguistic modifications of discourse analysis may help to choose better semantic toolkits for the communications but cannot evaluate its success. Analysis of political narrative may assist in the search for reconciliation, but neither of the parties in this confrontation looked for such reconciliation.

5. Conclusion

In the context of increasing complexity and speed up processes of the social information exchange, the use of PR message as an analysis category opens up significant opportunities for a researcher of PR communication and propaganda to identify the patterns for information campaign development, allows determining favorable and unfavorable circumstances for campaign development and adjusting campaign plans promptly.

In methodological terms, the research based on this category of analysis utilizes the tools for sampling and coding from the content analysis arsenal, as well as data processing tools that belong to the analysis discourse tools (finding motives, channels, the effectiveness of communication, argumentation of the sides) and narrative analysis (identification of primary sources of narratives and participation of various communicators in the story narration).

In this case, the most important subcategories of the study are the messages of different aspects of the information campaign: promotion, attack, defense, counterattack, expert judgments. Depending on the nature of the campaign and the research tasks, other subcategories of analysis can be selected, based on which it is possible to draw conclusions about the attention of media of different categories to each of the messages used as well as about the dynamics of development and fading of conflict.

This method is appropriate both in the corporate sector and as a part of countering the information aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine and other democratic states.

In future studies, the proposed methodology should be combined with quantitative evaluation of the effectiveness of getting out the point in each message involved in the information campaign, as well as with the quantitative evaluation of the message credibility for the target audience, in particular with those suggested by (Kazokiene & Stravinskiene, 2011). This will combine the output and outcome analysis.

Bibliography

Agility PR Solutions. (2017). 4 PR messaging tips to improve your communications strategy. Agility. https://www.agilitypr.com/pr-news/public-relations/4-tips-improve-pr-messaging/

Altheide, D. L., & Snow, R. P. (1979). Media Logic. SAGE Publications.

AMEC | International Association for the Measurement and Evaluation of Communication. (2020). Barcelona Principles 3.0. https://amecorg.com/2020/07/barcelona-principles-3-0/

Ammann, C., Giuffredi-Kähr, A., Nyffenegger, B., Harley, K., & Hoyer, W. (2020). A Typology of Consumer Brand Defenders: When Egoists, Justice Fighters and Brand Fans Defend your Brand. Proceedings of the European Marketing Academy, 49th, Article 63341.

Austin, E. W., & Pinkleton, B. E. (2006). Strategic Public Relations Management. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410616555

Baranov, A. N. (2001). Introduction to Applied Linguistics. Editorial URSS.

Daymon, C., & Holloway, I. (2010). Qualitative Research Methods in Public Relations and Marketing Communications. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203846544

Diesner, J., Kim, J., Pak, S., Soltani, K., & Aleyasen, A. (2014). Computational Impact Assessment of Social Justice Documentaries. The Journal of Electronic Publishing, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0017.306

Dijck, V., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding Social Media Logic. Media and Communication, 1(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.12924/mac2013.01010002

Garvin, T., & Eyles, J. (2001). Public health responses for skin cancer prevention: the policy framing of Sun Safety in Australia, Canada and England. Social Science & Medicine, 53(9), 1175–1189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00418-4

Gerus, A. (2016, June 22). What’s Wrong With the “Rotterdam Formula”? Ukrayinska Pravda. https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/columns/2016/06/22/7116844/

Gruzd, A., & Tsyganova, K. (2015). Information wars and online activism during the 2013/2014 crisis in Ukraine: Examining the social structures of Pro- and Anti-Maidan groups. Policy and Internet, 7(2), 121–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.91

Hampton, G. (2009). Narrative policy analysis and the integration of public involvement in decision making. Policy Sciences, 42(3), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9087-1

Hon, L. C., & Grunig, J. E. (1999). Guidelines for Measuring Relationships in Public Relations. Institute for Public Relations. www.instituteforpr.org

Hongcharu, B. (2019). Effects of Message Variation and Communication Tools Choices on Consumer Response. Global Business Review, 20(1), 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150918803528

Ingram, H. J. (2017). An Analysis of Inspire and Dabiq : Lessons from AQAP and Islamic State’s Propaganda War. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 40(5), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2016.1212551

James, M. (2011). Ready, aim, fire: Key messages in public relations campaigns. PRism, 8(1).

Karmanau, Y. (2017, December 11). Ukraine’s Anti-Corruption Agency Faces Strong Resistance. US News. https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2017-12-11/success-then-suppression-for-ukraine-anti-corruption-agency

Kazokiene, L., & Stravinskiene, J. (2011). Criteria for the Evaluation of Public Relations Effectiveness. Engineering Economics, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.22.1.222

Knight foundation. (2011). IMPACT: A Practical Guide to Evaluating Community Information Projects. https://knightfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/Impact-a-guide-to-Evaluating_Community_Info_Projects.pdf

Laughey, D. (2008). Key Themes in Media Theory. Open University Press.

Lokot, T. (2018). #IAmNotAfraidToSayIt: stories of sexual violence as everyday political speech on Facebook. Information Communication and Society, 21(6), 802–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1430161

Nai, A., & Maier, J. (2018). Perceived personality and campaign style of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. Personality and Individual Differences, 121, 80–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.020

Napoli, P. M. (2014). Measuring media impact: an overview of the field. Hampton Press. www.learcenter.org.

Plessis, D. Du. (2000). Introduction to Public Relations and Advertising. Juta and Company Ltd. https://books.google.com/books?id=dU2Yz3u9lMoC&pgis=1

Reputation Institute. (2020). RepTrak. https://www.reputationinstitute.com/solutions

Rice, R. E., & Atkin, C. (2009). Public Communication Campaigns: Theoretical Principles and Practical Applications. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media Effects. Advanced Theory and Research (pp. 436–468). Routledge.

Riessman, C. K. (2002). Narrative Analysis. In The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion (pp. 216–270). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412986274.n10

Roe, E. (1994). Narrative Policy Analysis. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822381891

Ronzhyn, A. (2016). Social media activism in post-euromaidan Ukrainian politics and civil society. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference for E-Democracy and Open Government, CeDEM 2016, May, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1109/CeDEM.2016.17

Sienkiewicz, M. (2016). Open source warfare: the role of user-generated content in the Ukrainian Conflict media strategy. In Media and the Ukraine Crisis: Hybrid Media Practices and Narratives of Conflict (pp. 19–70). Peter Lang.

Syme, G. J., Nancarrow, B. E., & Seligman, C. (2000). The Evaluation of Information Campaigns to Promote Voluntary Household Water Conservation. Evaluation Review, 24(6), 539–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X0002400601

Thurman, N. (2018). Mixed-Methods Communication Research: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches in the Study of Online Journalism. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526428431

van Dijk, T. A. (1997). What is Political Discourse Analysis? Belgian Journal of Linguistics, 11, 11–52. https://doi.org/10.1075/bjl.11.03dij

Vincent, R. C. (2000). A Narrative Analysis of US Press Coverage of Slobodan Milosevic and the Serbs in Kosovo. European Journal of Communication, 15(3), 321–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323100015003004

Wilcox, D. L., Cameron, G. T., Agee, W. K., & Ault, P. H. (2003). Public Relations: Strategies and Tactics.

Yuzva, L. (2015). Students on social revolutions in Ukraine in the early ХХІ century. Bulletin of V. Karazin Kharkiv National University, 1148, 140–146.

Zakharchenko, A., Maksimtsova, Y., Iurchenko, V., Shevchenko, V., & Fedushko, S. (2019). Under the Conditions of Non-Agenda Ownership : Social Media Users in the 2019 Ukrainian Presidential Elections Campaign. COAPSN-2019 International Workshop on Control, Optimisation and Analytical Processing of Social Networks, 199–219. http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2392/paper15.pdf

Zakharchenko, A., & Zakharchenko, O. (2021). The Influence of the ‘Tomos Narrative’ as a Part of the Ukrainian National and Strategic Narrative. Corvinus Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 12(1), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.14267/CJSSP.2021.1.7

Zakharchenko, O., Zakharchenko, A., & Fedushko, S. (2020). Global challenges are not for women: Gender peculiarities of content in Ukrainian Facebook community during high-involving social discussions. CEUR Workshop Proceedings, 2616, 101–111.

Центр контент-аналізу. (2018). How do we explore you: methodology and samples of the Content Analysis Center. The Center for Content Analysis. http://ukrcontent.com/blog/yak-mi-vas-doslidzhuemo-metodiki-i-vibirki-centru-kontent-analizu.html