Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2022, vol. 93, pp. 77–92 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2022.93.63

Searching Peace through War: The Presentation of Pakistan Govt Talks with Therik Taliban Pakistan in National Press

Lubna Shaheen

Utrecht University, The Netherlands

lubna.g786@gmail.com

Muhammad Tarique

Utrecht University, The Netherlands

m.tarique@uu.nl

Abstract. After over two decades of violence, loss of thousands of civilians, displacement of tens of thousands of people, and damages to key infrastructure in Pakistan by Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), the central government decided to talk with them in 2014. These peace talks were vital, as their failure could inevitably lead to a longer war. This study is about the coverage given by the Pakistani national press on these peace talks and the military operation followed by it. It is evaluated how much print media have played their role either in initiating peace or instigating war. With this intention, Johan Galtung’s theory of Peace Journalism was applied. Analyzing the contents of four elite national English and Urdu dailies the study concluded that the mainstream press portrayed the peace talks with a considerable difference throughout peace talks, which had undermined the government approach of bringing peace. War-oriented coverage of the operation tells that whatever would be the situation media would sensationalize it. Within the news stories, mixed expressions were seen towards both peace and war but the overall coverage remained war-oriented.

Keywords: peace talks; Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan (TTP); violence; peace journalism (PJ); war journalism (WJ); military operation/Zarb e Azab.

Taikos paieškos karo metu: Pakistano vyriausybės derybų su Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan nušvietimas nacionalinėje spaudoje

Santrauka. Po daugiau nei du dešimtmečius trukusio smurto, tūkstančių civilių netekties, dešimčių tūkstančių žmonių persikėlimo į kitas vietas ir žalos, kurią padarė Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) pagrindinei Pakistano infrastruktūrai, 2014 m. centrinė vyriausybė nusprendė su jais pradėti derybas. Šios taikos derybos buvo labai svarbios, nes joms nepasisekus neišvengiamai galėjo kilti dar ilgesnis karas. Šiame tyrime analizuojama, kaip šios taikos derybos ir po jų vykdoma karinė operacija buvo nušviečiamos Pakistano nacionalinėje žiniasklaidoje. Aiškinamasi, kokį vaidmenį suvaidino žiniasklaida: ar inicijuojant taiką, ar kurstant karą. Šiuo tikslu buvo pritaikyta Johano Galtungo taikos žurnalistikos teorija. Išanalizavus keturių elitinių nacionalinių dienraščių anglų ir urdu kalbomis turinį, tyrime daroma išvada, kad pagrindinė spauda taikos derybas vaizdavo labai skirtingai, o tai pakenkė vyriausybės požiūriui siekiant taikos. Į karą orientuotas operacijos nušvietimas spaudoje leidžia suprasti, kad ir kokia būtų situacija, žiniasklaida vis tiek ją pateiktų sensacingai. Naujienų straipsniuose buvo pastebimi prieštaringi pasisakymai tiek apie taiką, tiek apie karą, tačiau bendras situacijos nušvietimas išliko orientuotas į karą.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: taikos derybos; Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan (TTP); smurtas; taikos žurnalistika (PJ); karo žurnalistika (WJ); karinė operacija / Zarb e Azab.

Received: 2021-06-09. Accepted: 2022-03-29.

Copyright © 2022 Lubna Shaheen, Muhammad Tarique. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Conflicts need mediation, and in larger conflicts, the media, due to its underlying power, play imperative role in disputes as a third-party mediator. News certainly play a role in conflicts (Hackett, 2007) and it largely depends on the perception and portrayal of an issue by the gatekeepers that may change the dimensions of the whole problem. Studies support the role of media in the escalation of the conflict (Lee, 2010; Maslog & Lee, 2005; Galtung, 2000), but literature is limited to few examples on media’s role in peace promotion (Bratic, 2015). Media give priority to war and violence and give huge coverage; however, peace news are scarce (Wolfsfeld, 2004). Studies show that media prefers and sensationalize war than peace (Wolfsfeld, 2004) in most of the cases, e.g., the Ireland peace process, in which media proved to be a promoter of conflict than a facilitator of peace. Spencer (2004), referring to the northern peace process, said “television news operates more effectively for the promotion of conflict rather than peace”. Similarly, in the case of the Vietnam War, Herman & Chomsky (1988) blamed US media for restricting information that was not favourable to the US government and controlling the voices of the anti-war movements and the people of Vietnam, leaving the impression that Vietnam, not the US, was the provoker of war. Therefore, if the media has the power to escalate conflicts, it has the power to de-escalate as well (Bratic, 2006). Media can influence positively in the peace process with long-lasting effects (Becker, 2004). There are examples where media played their role as a peacebuilder, media heavily supported the “Good Friday Agreement” Campaign between Great Britain and Ireland (Bratic, 2007).

Focus on war journalism causes an increase in conflict, while PJ helps to decrease it (Galtung, 1998).

Talks and dialogues are the first steps towards a peaceful resolution of conflicts, the most difficult breakthrough in any larger dispute is bringing people to a discussion table under one roof; as Byman (2006) said, the circumstances for favourable talks are not always welcoming since the beginning of talks with a terrorist group may strengthen them more. The success of peace talks not only brings peace but also prevents from loss of human lives, infrastructure, and financial resources. Media have a major role to play as a conflict resolver, in an ideal situation, media work as a bridge between the government, the negotiating party, and the public. As Davison said, (1974) “Media provide for a two-way flow of influence; from the negotiators to the public, and from the public to the negotiator”. So, the way the press portrays a situation is likely to affect the outcomes.

Since 9/11 the Taliban problem has been receiving enormous coverage in the Pakistani press, especially during 2014 when the government of Muhammad Nawaz Sharif decided to bring TTP to the discussion table and give a chance to a peaceful resolution of the long-lasting violence. This study is about the presentation of peace/war journalism in the coverage of the peace process with TTP and the military operation against TTP in leading English and Urdu dailies of Pakistan. The peace process was the result of violence ensued by the TTP, and when it was decided by the Nawaz regime, the media gave huge coverage. The purpose is to analyse how newspapers presented two opposite aspects of the same conflict through PJ.

Historical background of the conflict

In 1979 the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, and the Afghan people were supported and funded by the United States, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia (Bew et al., 2013, p. 10). The US, allied with Pakistan, heavily funded the Madrassas (religious education seminaries) in Afghanistan (Shaheen & Tarique, 2021) to fight against the Soviet forces. From 1979 to 1992 the US spent at least 3 billion dollars on Afghan Mujahidin (Parenti, 2001; Singh, 2007) for equipping them to fight against Soviet forces. In 2001, the US declared war against terror, therefore “heroes of US and Arab nations who sponsored the Afghan jihad (holy war) against the Soviet Union were suddenly declared as villains, enemies, and terrorists” (Byman, 2006). Once again Pakistan decided to help the US and provided support to the US government and NATO forces in Afghanistan. This gave rise to terrorists’ activities against Pakistan. Since then, the Taliban have played havoc with the peace of the country taking the lives of thousands of people and damaging the social fabric of Pakistani society. In this scenario, the political government decided to resolve the Taliban issue with dialogues and brought TTP to the discussion table in January 2014. Talks were proceeding when Taliban killed 23 army men, and consequently suspended a few times but started again, and finally failed due to the Taliban’s attack on Karachi airport. Resultantly, Pakistan’s military launched operation Zarb e Azab (sword of the Holy Prophet PBUH) in North Waziristan (Pakistani area bordering Afghanistan) with full political support on 15 June 2014. As opposed to what was assumed that Zarb e Azab would control the furious activities of the TTP (Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan), the heinous acts of violence in history were witnessed during and after the military operation of Zarb e Azab including bombing and shooting in Army Public School (APS), which killed 144 students and teachers (Dawn, December 14, 2015). Zarb e Azab caused the dislocation of more than a million local people and loss of Rs190 billion, “still the terrorist threat to Pakistan is far from defeated” (Basit, 2016). The recent developments in Afghanistan have given rise to TTP terrorists activities within Pakistan, causing the loss of lives of military and civil persons. So, the situation after eight and half years of military operation is still quite unpredictable.

Peace Journalism / Theoretical framework

Peace journalism (PJ) is a way to look at the other side of the story, to report, and to focus on the angles, which can prevent conflict and promote peace, “WJ and PJ are two different ways of reporting the same set of events” (Lynch and Galtung, 2010, p. 52). As of the journalism itself as a “service provider” in the lines of Luhmann’s “theory of social justice” (2000) and “the reality of Mass Media” (1995), whose function is to provide social co-orientation, “PJ is defined as a special mode of socially responsible journalism which contributes to peace” (Hanitzsch 2004, p. 483). Research after the civil war & the peace treaty of 1992 in El Salvador shows that the media positively promoted the democratization process and provided platform for dialogues that made it peace possible (Nuikka, 1999). German media reports after the WWII show that media positively portrayed the cooperation between Germany and France and followed responsible media ethics (Jaeger 2002b in Kempf, 2003).

Researchers believe that PJ can play a significant role in peacebuilding in war-torn societies, in chronic conflicts whether they are political, religious, or racial, in societies where there is no war but violence exists (Galtung, 1996; Galtung & Lynch, 2010; Lynch & McGoldrick 2005) and PJ can also be used as a pre-emptive measure where there are chances of conflicts and violence. Shinar (2007) stated, “Peace journalism is a normative model of responsible and conscientious media coverage of conflict, that aims at contributing to peace-making, peacekeeping, and changing the attitudes of media owners, advertisers, professionals, and audiences towards war and peace” (p. 2). Researchers agree that it is responsible journalism as it provides an opportunity to the journalists to contribute to the well-being of the society and cover the event in a way “that create opportunities for society at large to consider and value nonviolent responses to conflict” (Lynch & McGoldrick, 2005, p. 5). As Galtung (1997, 1998) suggested, PJ stresses that journalists should practice peace plans, they should try to highlight points that can help bring peace, work for the de-escalation of conflicts, and rehabilitation of societies.

Studies have examined the dominance of WJ in different conflicts; Lee and Maslog (2005) studied the press coverage of five countries in four different conflicts and found that overall WJ frames were more dominant than PJ frames. Siraj (2008) examined Pakistan & India conflict in two US newspapers and found that WJ stories were greater in number than PJ stories.

Talks and dialogues are the initial steps of resolving an issue, and especially when the issue involves violence. The role mass media play in the success of peace talks, making public opinion in favor of the positive solution and resolving conflicts is less observed. Howard et al. (2003) called media a “double-edged sword”, as it sometimes works for peaceful resolution of the conflict and most of the time works against the peace (Des Forges, 1999; Price and Thompson, 2002).

Media, considering their broader range of powers, can influence the peace process, as Hawkins noticed that “Media agendas do influence a broad range of policy initiatives and lack of media coverage contributes to lack of policy” (2002, p. 225). “Media can perform positively when peace is really on political agenda” (Kempf 2003, p. 9). Radio Douentza in Mali, which was serving a very small community of mostly farmers, took the peace initiative through their service. There was an ongoing conflict between two groups of the community and every year a large number of people were being killed in clashes. The radio took three initiatives to possibly reduce the violence, like positive public service messages and quick information regarding incidents, so the authority could intervene & give voice to the farmers so they can discuss their issues. The Dayton Peace Agreement ended the three-year civil war between Serbians, Croatians, and Bosnians in 1995, which took the lives of thousands of people. In this process of peace-building, the radio was the main media heavily used by all three sides for peace-building (Bratic, 2008). PJ can resolve national conflicts as well; a study on the Balochistan conflict (Tarique, 2017) reveals that press uses war frames than peace frames in their converge of the issue and suggested that if more peace frame could be used the situation would be different.

Today’s media have more opportunities to intervene into the conflicts, but how they intervene is most of the time questionable; however, it is certain that they escalate conflicts (Junne, 2013, para. 2). They do so by giving a biased coverage, ignoring the actual facts, and knowingly or unknowingly favouring one side of the conflict. Media in Sierra Leone incited the war by giving biased coverage of the incidents that were in favour of the insurgents rather than the government (Bau, 2010). Foreign media also covered the war in Sierra Leone in a way that was also not unbiased, giving a picture of Africa as a “no hope zone” (ibid, p. 20).

Coverage of operation Zarb e Azab in Pakistani newspapers was analyzed by Hussain & Munawar (2017), who concluded that the operation was “inclined more towards WJ framing than PJ framing in their coverage of the Taliban conflict” (p. 38). A comparison of English and Urdu press concluded that Urdu newspapers were more war-oriented than the English newspapers of the country (ibid). The newspapers “supported the official version on the conflict and operation but also marginalized and undermined alternative voices calling for a peaceful resolution of this years-long conflict” (Hussain & Munawar 2017, p. 38). Quite contrary to that, another study, which considered only one-month coverage of the selected issue, suggested the negative role of media during the initial days of operation, criticizing that print media framing of the operation was not supportive, as they showed their dissatisfaction over the launch of the operation. They focused more on the civil-military divide and the problems caused by the operation of Zarb e Azab (Khan & Akhtar, 2016). They argued that “coverage of Operation Zarb-e-Azb is biased and thus challenging the state’s policy on counter-terrorism. It is far from being neutral and acts irresponsibly mocking the ethics of journalism” (Khan & Akhtar, 2016).

A study analysed AP and Xinhua’s coverage and observed that they were also critical of Pakistan’s role in combating terrorism before the start of operation, but a considerable shift was seen in the image of Pakistan as a “victim” after operation Zarb-e-Azab started (Yousaf, 2015). The coverage of three Pakistani newspapers was analysed by Subhani & Sultan (2015), who concluded that “the newspapers were mostly against the peace talks and government and media were not on the same page on the issue of peace talks” with the Taliban before Zarb-e-Azab (p. 47). “Picture of Pakistan army was given negative coverage in selected press before operation Zarb-e-Azb and after the beginning of operation Zarb-e-Azb, both daily papers positively portrayed Pakistan army” (Ali & Wazir, 2016). Considerable difference was found in the framing of the Pakistan army in American Newspapers before and during Arab-e-Azab (ibid). In another study, the researchers analyzed tweets (16411) and retweets during August and Sep 2014 and proposed that social media users were mainly in favour of operation Zarb e Azab and believed that only the military can crush terrorism and the only way to combat terrorism is war (Lashari & Wiil, 2016).

Peace journalism is an effort to initiate peace through media platforms. Galtung’s (1997) peace and war indicators have been considered as two contrasting ways of covering of events during conflicts. Galtung defined media’s role either as an instigator of war or initiator of peace. His proposed model of PJ provides a guideline to journalists to focus more on responsible journalism than a sensational side of converge. PJ is more of a conscious effort than a traditional way to cover the conflicts, so it could be helpful in peaceful resolution. Peace journalists must have strong knowledge of the conflict before reporting on it.

Methodology

Quantitative content analysis to measure the peace/war indicator has been used in the coverage of four newspapers from English & Urdu languages. N is 1229 during one year, the unit of analysis is the hard news published on the front pages of the newspapers.

Peace talks from January 1, 2014, to June 15, 2014, and Military operation from June 16, 2014, to December 31, 2014. The reason for taking an equal period is to justify the period for two different phases of same conflict. To see how the press covered peace process and how it covered operation against TTP.

The following research questions have been suggested on the overall war and peace time period in the selected press. The purpose is to understand whether the press promoted peace or war through its presentation of the events and to analyse the difference of coverage given to the issue in different times and in different language newspapers.

RQ1. Which type of coverage; either peace or war is given by the selected press during each of two selected periods?

RQ2. Is there any difference of war and peace journalism among English and Urdu Newspapers during the selected time?

RQ3. Does the coverage of the selected press differ in the war and peace coverage of TTP talks and Operation Zarb e Azab?

The data of “Dawn” & “Jang” were collected manually from the library archive since Dawn and Jang’s online versions are not in the form of a complete page, which makes it difficult to analyze the size & placement of the story at the front page. Images of the whole page were taken and then were shifted to the computer for analysis. The data from The Nation1 and Express2 was collected from the online version of newspapers websites and

The pilot study of the content indicated that not all of the thirty-four indicators introduced by Johan Galtung’s (1986) classification of war and peace journalism are existent in the coverage, so only twelve of war and twelve of peace indicators were selected from Galtung (1986) classification.

Hard news from the front pages of four newspapers were selected for analysis, considering they include the following words: Taliban, TTP Talks, government and Taliban, US Drone attacks, internally displaced people (IDPs) of North Waziristan, Army’s role, operation Zarb-e-Azab, Political parties’ stance over talks/Zarb-e-Azab, Bomb blasts, US stance about Taliban.

Table 1: Galtung’s war and peace journalism explanation table

|

War/Escalation - Indicators |

Peace/ De-escalation - Indicators |

|

1. Discussing problems only 2. Discussing peace doing war 3. Controlled society 4. Making war secret/propaganda 5. Us and them 6. Only they are wrong (blaming) 7. Name of their wrongdoers 8. Their lies our truths 9. We are strong/they are a week 10. Discussing only surface losses 11. Elite coverage 12. Discussing conflict only |

1. Discussing their solution also 2. Current issues are more important 3. Discussing causes of the conflict 4. Peaceful society 5. Making war transparent (telling the truth) 6. Equality 7. Both are accountable 8. Names of both sides’ wrongdoers 9. Both sides lies and both sides truths 10. Both are equal (both should be considered) 11. Elite and poor coverage (coverage of sufferers, IDP’s, their problems) 12. Discussing conflict resolution |

Table 2: Selected Newspaper presentation in terms of WJ & PJ

|

War/Escalation – |

Definitions and |

Peace/ De-escalation – indicators |

Definitions and |

|

1. Discussing problems Only

|

1. “Taliban ko khatam kar dain dehshat gardi khatam ho jaiy gi” [Peace wouldn’t be a reality till to the existence of Talibans] (January 21, 2014, Express).

|

1. Discussing their solution also

|

1. “Expressing reservations over the proposed military operations, Maulana Fazl said the use of force was not a solution to the problem. The prevailing situation could be controlled only through a national security policy” (January 27, 2014, Dawn). |

|

2. Discussing peace doing war (when media uses the third party to say it)

|

2. “Opposition wants army action against Taliban” (Dawn, January 21, 2014). “After killing thousands of members of various state organs, as well as others the violent Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) has decided to extend its war by declaring the country’s media as a party to the conflict” (January 23, 2014, Dawn). (The period when peace talks were in progress). |

2. Discussing causes of the conflict

|

2. “The committees representing the government and the Taliban agreed on Saturday to extend the ceasefire and take measures to speed up the dialogue process” (March 30, 2014, Dawn).

|

|

3. Controlled society

|

3. “No room in law for talks with terrorists” (February 02, 2014, Dawn)

|

3. Peaceful society

|

3. “Amaan sirf Taliban say muzakraat say he ho sakta ha” [Peace and talks are interdependent entities] (Jang, January 18, 2014) |

|

4. Making war secret

|

4. “Government weighing options on Taliban issue” (February 24, 2014, Dawn)

|

4. Making conflict transparent

|

4. “TTP claims responsibility for the attack” (February 14, 2014, The Nation). |

|

5. Us and them

|

5. “Surrender or perish; no relaxation to militants this time” (June 16, 2018, The Nation) “8 soldiers 20 militants die in clash” (November 2, 2014, The Nation) |

5. Equality

|

5. “Member of government peace committee told the media that it would be difficult to continue peace dialogue as both government and Taliban are not agreeing on a ceasefire” (May 22, 2014, The Nation) |

|

6. Only they are wrong (blaming/ when airstrikes and drones were killing Taliban‘s also)

|

6. Humaray dushman islam ki arth main chup kar karwaian kar rahay hain” [Our enemies are attacking us in the garb of forces in the name of Islam] (March 25, 2018, Jang) |

6. Both are accountable

|

6.“Shumali Waziristan say 13000 kabailion ki nakalmakani. Koi imdad nahi mili na kahin rahnay dia ja raha ha” [13000 tribesmen are displaced from the N Wazirastan. These IDPs are made homeless without giving shelters to live on] (January 26, 2014, Jang) |

|

7. Name of their wrongdoer

|

7.“Fazlullah mobilizes bombers” (May 19, 2014, The Nation)

|

7. Names of both sides’ wrongdoers

|

7. “No ceasefire is possible unless intelligence agencies stopped killing and dumping bodies of their fighters” (Nation February 20, 2014). |

|

8. Their lies our truths

|

8. “Talks injustice to terror victims; forces undertook Fata* airstrike in self-defense” (February 21, 2018, Dawn). |

8. Both sides lie’s and both sides truths

|

8. “TTP offers security to negotiators” (February 3, 2014. The Nation)

|

|

9. We are strong

|

9. “Terror to be eliminated: COAS” (June 12, 2014, The Nation)

|

9. Both are equal

|

9. “Taliban say muzakarat ki rah main rukawat, Drone ya khudkush haamlay” [Drones attacks and suicide attacks are reason of peace talks] (January10, 2014, Express) |

|

10. Discussing surface losses only

|

10.Taliban say muzakarat par itfaq karnay wali tamam jamatian pechay hat gain, hum ikalay rah gay (January 16, 2014, Express)

|

10. Discussing after-effects

|

10.Taliban say Muzakarat darust simt may aagay bhar rahay han, kom ko kushkhabri dain gay [Dialogues with the Talibans are becoming successful and the nation would see the era of peace soon] (March 3, 2014, Jang) |

|

11. Elite coverage

|

11. “TTP talks can’t progress amid needless rhetoric; Nisar” (May 3, 2014, the Nation) |

11. Elite and sufferers’ coverage

|

11. Operation Zarbe e Azab ko do Haftay ho gaye hain aur panch lac IDPs hijrat kar cukay hain [Half a million IDPs are displaced in the two weeks from the start of Operation Zarb e Azab] (June 27, 2014 Jang) |

|

12. Discussing conflict only |

12. “Taliban split on ceasefire extension” April 3, 2014, (the Nation) |

12. Discussing conflict resolution |

12. Aaman kay leay Taliban say Muzakarat karnay hon gay [peace talks are necessary to bring peace] (January 12, 2014, Express) |

* Federally administrated areas

For an in-depth analysis at the second level, each news story has been divided into four parts i.e.,

1. Lead (Lead and sub-leads)

2. Introduction

3. Important details in the body of the text

4. Less important details in the body of the text

The analysis of the story into four main parts will help to establish which part of the story to be used as peace- or war-oriented. Stories were analyzed keeping in view and twelve peace & twelve war indicators based on Galtung’s (1986) taxonomy of peace war indicators (Table .1). Each news story was analyzed for its tone at four given levels, the score of 01 was recorded if the first part (lead or sub-lead) falls into the peace or war category; hence, if all the four parts of the story were peace-oriented, the score of peace orientation was recorded. Similarly, if overall the story consists of more peace frames, it was recorded as peace-oriented, and if there were more war indicators, it was classified as war-oriented, and if both were equal, it was considered neutral (Maslog & Lee, 2005).

Findings and Analysis

Table 3: Frequency of news stories in Four Newspapers

|

Newspapers |

Frequency |

Percent % |

|

Dawn |

251 |

20.4 |

|

The Nation |

180 |

14.6 |

|

Jang |

328 |

26.7 |

|

Express |

470 |

38.2 |

|

Total |

1229 |

99.9 |

During one year N was 1229, among them the highest news stories on the issue were produced by Express (470) followed by Jang (328), Dawn (251), and The Nation (180).

RQ 1. Which type of coverage; either peace or war is given by the selected press during each of two selected periods?

Table 4.a: Frequency distribution of WJ-PJ indicators among newspapers

|

Newspaper |

Indicators |

N% |

||

|

WJ % |

PJ % |

Neutral % |

||

|

Dawn |

181(72.1) |

58(23.1) |

12(4.7) |

251(100) |

|

The Nation |

119(66.1) |

43(23.8) |

18(10.0) |

180(100) |

|

Jang |

151(46.0) |

159(48.4) |

18(5.4) |

328(100) |

|

Express |

214(45.5) |

229(48.7) |

27(5.7) |

470(100) |

|

Total |

665(54.1) |

489(39.7) |

75(6.1) |

1229(100) |

χ2 = 33.227, p <0.001; Cramer’s V = .164, p <0.001. Among 1229 news stories 665 (54.1%) were framed as WJ, while 489 (39.8) were framed as PJ and 75 (6.1) were neutral.

Although WJ indicators were the strongest in the overall coverage of newspapers, the highest percentage of WJ indicators were seen in the coverage Dawn, with nearly 72% of the news being war-oriented, followed by The Nation (66.1%), Jang (46%), and Express (45.5%). In terms of the structure of the news, overall WJ were more dominant than PJ or neutral coverage.

Table 3.b: Distribution of War and Peace journalism among news structure

|

|

Lead % |

Intro % |

Imp Details % |

Less imp details % |

|

WJ |

591(48.1) |

623(50.7) |

592(48.2) |

582(47.4) |

|

PJ |

496(40%) |

498(40.5) |

513(41.7) |

512(41.7) |

|

Neutral |

142(11.6%) |

108(8.8) |

124(10.1) |

135(11%) |

|

Total |

1229 |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Lead χ2 =1515.6, p <.0001; Cramer’s V = 0.785, p <.0001:

Intro χ2 =1571.0, p <.0001; Cramer’s V = 0.799, p <.0001:

Important Details χ2 =1566.7, p <.0001; Cramer’s V = 0.798, p <.0001:

Less important details χ2 =1517.6, p <.0001; Cramer’s V = 0.786, p <.0001.

There was a significant difference in terms of WJ/PJ reporting of different portions of the news. WJ was more dominant in all the portion of news than PJ and neutral. The “Intro” section of the news stories was more war-oriented (50.7%) than the other three parts of the story.

Table 3.c: Frequency of WJ and PJ Indicators in newspapers

|

War/Escalation - |

Frequency % |

Peace/ De-escalation - |

Frequency % |

|

1. Discussing problems Only 2. Discussing peace doing war 3. Controlled society 4. Making war secret/propaganda |

332(9.7) 261(7.6) 177(5.1) 305(8.9) |

1. Discussing their solution also 2. Discussing what is happening/why is it happening 3. Peaceful society 4. Making war transparent (telling the truth) |

151(7.1) 178 (8.4) 308(14.6) 416(19.8) |

|

5. Us and them 6. Only they are wrong 7. Name of their wrongdoers 8. Their lies our truths 9. We are strong/they are week |

270(7.9) 384(11.2) 794(25.8) 221(6.4) 209(6.1) |

5. Equality 6. Both are accountable 7. Names of both sides’ wrongdoers 8. Both sides lies and both sides truths 9. Both are equal (both should be considered) |

97(4.6) 94(4.4) 273(13) 150(7.1) 120(5.7) |

|

10. Discussing the only surface loss |

103(3%) |

10. Discussing after-effects (financial, human losses) |

107(5.1) |

|

11. Elite coverage |

98(2.9) |

11. Elite and poor coverage (Coverage of sufferers, IDP’s, problems) |

103(4.9) |

|

12. Discussing conflict only |

171(5%) |

12. Discussing conflict resolution |

101(4.8) |

|

Total |

3413(100) |

|

2098(100) |

The total count of WJ indicators was 3413. The most salient indicators were the names of their wrongdoers (25.8%), only they are wrong (11.2), and discussing problems only (9.7). The reason could be that the media usually create a divide between the two parties involved in the conflict by taking the side of one party and putting blame on the other side. The total number of PJ indicators was 2098, with most commonly used indicators being making war transparent (19.8), peaceful society (14.6), and discussing what is happening (8.4).

RQ2. Is there any difference between war and peace journalism indicators among English and Urdu Newspapers?

Difference of war and peace journalism among newspapers

χ2 = 80.308, p <0.001; Cramer’s V = 0.181, p <0.001

Overall, there was a significant relationship between war and peace coverage and English and Urdu language newspapers. English language newspapers presented more war journalism stories than Urdu press. The frequency of WJ in English newspapers was 300/431(69.6) and in Urdu, newspapers was 365/798 (45.7). This finding supports the notion that English language newspapers have more war-oriented coverage than Urdu language newspapers.

RQ3. Does the coverage of the selected press differ in the framing of TTP talks and Operation Zarb e Azab?

The difference in the coverage of peace talks and Operation Zarb e Azab

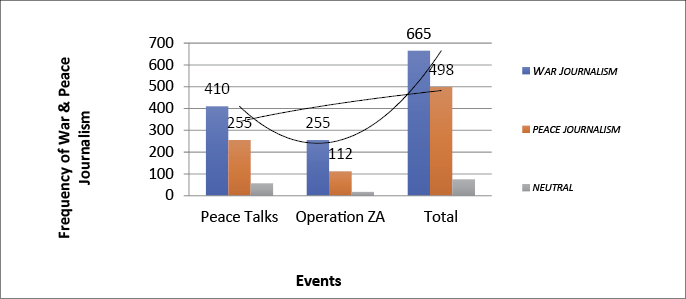

Table 5: Difference in coverage patterns amongst two events

|

Indicators |

Peace Talks % |

Zarbe e Azab % |

N% |

|

War |

410(61.6) |

255(38.3) |

665(100) |

|

Peace |

377(77.0) |

112(22.9) |

489(100) |

|

Neutral |

57(76.0) |

18(24.0) |

75(100) |

|

Total |

844(68.7) |

385(31.3) |

1229(100) |

T-test, Peace talks (M= 1.58, SD =0.61), and Operation Zarb e Azab (M=1.38, MD=0.57) conditions; t (1229) = 5.319, p = .001. Overall, the coverage of peace talks was significantly higher than operation Zarbe e Azab, while WJ coverage was higher (61.6) than operation Zarbe e Azab (38.3). But also, peace talks got more peace-oriented coverage (77.0) than operation Zarbe e Azab (22.9), whereas the number of neutral news (75) during the whole year, peace talks (76.0) followed by military operation (24.0).

Figure 1: Difference of coverage in Peace Talks and Zarb e Azab

The coverage patterns differ in terms of two aspects: frequency distribution of War and PJ and distribution of news stories between two different events.

Conclusion

This study has a unique aspect as it covers the two opposite periods (peace talks and military operation) of the same event (Taliban conflict). The findings regarding the first research question suggest that the overall coverage of all newspapers was war-dominated in both periods. The newspapers applied more war journalism indicators. The findings support the notion that media hesitate in reporting peace and remain war-oriented in conflicts. Lee and Maslog (2005) examined the press coverage of five countries in four different conflicts and found that overall war journalism frames were more dominant than peace journalism frames; Lee (2010) observed again that “more intense conflicts are associated with a higher use of war journalism frames” (p. 364). Another important finding is that the press gave huge coverage to Taliban talks, but when the operation started its coverage declined. The reason might be that the press overall was not supportive of the peace process and were criticizing the government’s initiative, so when the government changed its stance towards war the newspapers’ claim was fulfilled.

The English press was more war-oriented than the Urdu press. The results of the second research question support Lee’s (2010) suggestions that there is a significant difference between war and peace framing of the news stories in the English language & vernacular language news stories – English language news stories are more likely to be war-oriented than the local language stories. Rehman (2014) concluded that English newspapers present more war journalism stories than Urdu language newspapers in a military operation against Lal Masjid. The present study suggested that Dawn’s coverage was more tilted towards war than The Nation. The traditional print media, e.g., Dawn still holds a significant readership and is popular in Pakistan. Having a readership of 1.38 million, it has a vast impact on Pakistani people. Also, it is read by the elite people, politicians and policy-makers, the foundation had generally demonstrated more prominent strength and resistance to its feedback (Tarique, 2017). On the other hand, The Nation is the most cited Pakistani newspaper since its emergence in the national mediascape in 1986. With overall 400,000 circulations across the country, its base rely upon the national ideology of Pakistan, and the same is the case here, when during peace talks, its coverage remains less war oriented. The Nation also remained favourable to military operation in lines with the govt’s stance and gave war-oriented coverage during that period. The Urdu newspapers Jang and Express were tilted more towards the peace journalism narrative than war journalism, but the stories given by Jang were highly war-oriented and most of the time were given on the front page as banner lead. The reason possibly is that these both are national language newspapers and are read by common and rural people and have less influence on decision-making. All newspapers tagged different names to other parties like in the case of Dawn, most of the time when it reported about the TTP, its tag was the “outlawed Taliban”. The same is the case with other three newspapers: whenever they report about peace talks or operation Zarb e Azab, they used such tags for the Taliban. Peace talks with the TTP got more coverage than Operation Zarb e Azab and the press highlighted the news about violence which the Taliban were creating, but reports about ongoing operations by the military, drone attacks, and suffering of people affected by the military operation were overlooked by newspapers.

Considering the third research, the newspapers gave war-oriented coverage to both the events. These results correspond to a previous study by Shinar (2013) that newspapers would remain war-oriented whether they cover peace talks or an ongoing conflict. Subhani (2015) suggested that the Pakistani press played a negative role in peace talks with TTP by favouring war instead of peace. Pakistani newspapers’ narrative was more supportive of the government’s stance in the case of a military operation, while in the case of peace talks the attitude was opposite. So, the notion that media most of the time goes with the official stance does not fit here.

This study proposed that peace journalism has now become imperative for two main reasons: the escalation in conflicts and the emerging role of media. Scholars have argued that journalists should start practicing peace journalism (Galtung, 1996; Lynch & McGoldrick, 2005), since PJ enhances the quality of news coverage as a third party in a conflict, the facilitator of communication, mediator, or the arbitrator between two rival sides.

References

Ali, A. A., & Wazir, A. (n.d.). Operation Zarb-e-Azb: Treatment of Pakistan Army in the Western Media Before and After the Start of Operation Zarb-e-Azb. https://www.academia.edu/32924307/Operation_Zarb-e-Azb_Treatment_of_Pakistan_Army_in_the_Western_Media_Before_and_After_the_Start_of_Operation_Zarb-e-Azb

Basit, A. (2016). Pakistan’s Counterterrorism Operation: Myth vs. Reality: The diplomat (online). https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/pakistans-counterterrorism-operation-myth-vs-reality/

Bau, V. (2010). Media and conflict in Sierra Leone: national and international perspectives of the civil war. Global Media Journal-African Edition, 4(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.5789/4-1-10

Becker, J. (2004). Contributions by the Media to Crisis Prevention and Conflict Settlement. Conflict & Communication Online, 3(1/2). www.cco.regener-online.de

Bew, J. et. al, (2013). Talking to the Taliban: Hope over History? ICSR. Report of New American foundation. http://indianstrategicknowledgeonline.com/web/ICSR-TT-Report.pdf

Bratic, V., & Schirch, L. (2007). Why and when to use the media for conflict prevention and peacebuilding. European Centre for Conflict Prevention.

Byman, D. (2006). The Decision to Begin Talks with Terrorists: Lessons for Policymakers. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 29(5), 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100600703996

Davison, W. P. (1974). News media and international negotiation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 38(2), 174–191.

Des Forges, A. (1999). Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda. Human Rights Watch. www.hrw.org/reports/1999/rwanda/

Galtung, J. (2000). The task of peace journalism. Ethical perspectives, 7(2).

Galtung, J. (1996). Peace by peaceful means: Peace and conflict, development and civilization (Vol. 14). Sage.

Galtung, J. (1986). On the role of the media in worldwide security and peace. Peace and communication, 249–266.

Hackett, R. A. (2007). Journalism versus peace? Notes on a problematic relationship. Global Media Journal: Mediterranean Edition, 2(1), 47–53.

Hanitzsch, T. (2004). Journalists as peacekeeping force? Peace journalism and mass communication theory. Journalism Studies, 5(4), 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700412331296419

Hawkins, V. (2002). The other side of the CNN factor: the media and conflict. Journalism Studies, 3(2), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700220129991

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media. Pantheon.

Hussain, S., & Munawar, A. (2017). Analysis of Pakistan Print Media Narrative on the War on Terror. International Journal of Crisis Communication, 1(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.31907/2617-121x.2017.01.01.06

Howard, R., & European Centre for Conflict Prevention. (2003). The power of the media: A handbook for peacebuilders. European Centre for Conflict Prevention.

Jowett, G. S., & O’Donnell, V. (1999). Propaganda and Persuasion (3rd ed.). Sage.

Junne, G. (2013, September). The Role of Media in Conflict Transformation. Irenees.net. https://en.unesco.org/interculturaldialogue/resources/502

Kempf, W. (2003). Constructive conflict coverage- A social-psychological research and development program. Conflict and communication online, 2(2), 1–13.

Khan, M. K., & Wei, L. (2016). When friends turned into enemies: The role of the National State vs. Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) in the war against terrorism in Pakistan. Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 28(4), 597–626.

Khan, S., & Akhtar, N. (2016). Operation Zarb-e-Azb: An Analysis of Media Coverage. Journal of Strategic Studies, 36(1).

Lashari, I, A., & Wiil, U. K. (2016). Monitoring Public Opinion by Measuring the Sentiment of Retweets on Twitter. Proceedings of the 3rd European Conference on Social Media Research EM Normandie, Caen, France 12-13 July 2016. http://bdigital.ipg.pt/dspace/bitstream/10314/3469/1/ataconfernecia.pdf

Lee, S. T. (2010). Peace journalism: Principles and structural limitations in the news coverage of three conflicts. Mass communication and society, 13(4), 361–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430903348829

Lee, S. T., & Maslog, C. C. (2005). War or peace journalism? Asian newspaper coverage of conflicts. Journal of communication, 55(2), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb02674.x

Luhmann, N. (1995). Social Systems. Stanford University Press. Luhmann, N. (2000). The Reality of the Mass Media. Stanford University Press.

Lynch, J., & Galtung, J. (2010). Reporting conflict: New directions in peace journalism. UQP.

Lynch, J., & McGoldrick, A. (2007). Peace journalism. In C. Webel & J. Galtung (Eds.), Handbook of peace and conflict studies (pp. 248–264). Manchester University Press.

Lynch, J., & McGoldrick, A. (2005). Peace journalism: a global dialog for democracy and democratic media. In R. A. Hackett & Y. Zhao (Eds.), Democratizing global media: One world, many struggles (pp. 269–312). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Mendelzis, L. (2007). Representation of Peace in News Discourse: Viewpoint and Opportunity in Peace Journalism. Conflict and communication online, 6(1), 1–10.

Nuikka, M. (1999, July). Do they speak for war or for reconciliation? Role of the mass media in the peace process: A comparative analysis of three Salvadorian newspapers in April 1992 and in April 1998. In 20th IAMCR Conference in Leipzig.

Parenti, C. (2001). America’s Jihad: a history of origins. Social Justice, 28(3), 31–38.

Price, M. E., & Thompson, M. (Eds.) (2002). Forging Peace: Intervention, Human Rights and the Management of Media Space. University of Edinburgh Press.

Rahman, B. H., & Eijaz, A. (2014). Pakistani Media as an Agent of Conflict or Conflict Resolution: A Case of Lal Masjid in Urdu and English Dailies. Pakistan Vision, 15(2), 238.

Shaheen, L. & Tarique, M. (2021). From peace talks to military operation: Pakistani English newspapers’ representation of the TTP conflict. Discourse, media and conflict, Cambridge University Press. (In press).

Shinar, D. (2013). Reflections on media war coverage: Dissonance, dilemmas, and the need for improvement. Conflict & Communication, 12(2).

Shinar, D. (2007). Independent Media and Peace Journalism. In Another communication is Possible (pp. 178–185).

Singh, B. (2007). The Talibanization of Southeast Asia: Losing the war on terror to islamist extremists. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Siraj, S. A. (2008, May). War or peace journalism in elite US newspapers: Exploring news framing in Pakistan-India conflict. In Annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Montreal, Quebec.

Spencer, G. (2004). The impact of television news on the Northern Ireland peace negotiations. Media, Culture & Society, 26(5), 603–623. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0163443704044218

Subhani, M. S., & Sultan, K. (2015). Pakistani Newspapers on Peace Talks with Tahrik e Taliban Pakistan. Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies, 1(1), 47–60.

Tarique, M. (2017). Balochistan Unrest through the Lens of Pakistani National Print Media (1999-2008). [Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of the Punjab, Pakistan].

Wolfsfeld, G. (2004). Media and the Path to Peace. Cambridge University Press.

Yousaf, S. (2015). Representation of Pakistan: A Framing Analysis of the Coverage in the US and Chinese News Media Surrounding Operation Zarb-e-Azb. International Journal of Communication, 9, 23.

144 stories remembering lives list in Peshawar (2015, December 14). Dawn, 1. https://www.dawn.com/news/1223313