Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2023, vol. 96, pp. 21–39 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2023.96.64

Beauty Standard Perception of Women: A Reception Study Based on Foucault’s Truth Relations and Truth Games

Hasan Gürkan

Girona University, Philology & Communication Department, Spain

Istinye University, Communication Faculty, Radio, Television and Cinema Department, Turkey

gur.hasan@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3805-9951

Aybike Serttaş

Istinye University, Communication Faculty, Radio, Television and Cinema Department, Turkey

aybikeserttas@yahoo.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3471-7264

Abstract. This study discusses how television viewers’ definitions of beauty are affected by advertisements. The media effects on the perception of beauty and truth are explained in detail as the investigation unfolds. In November 2021 and May 2022, the study collected data through individual interviews with 22 women aged 18 to 63. The data gleaned from these interviews was interpreted with Stuart Hall’s coding-encoding theory using Peircein trichotomy and Foucault’s truth relations and truth games. The study found that one of the new functions of advertising is to enable female viewers to make personal evaluations of physical beauty standards and concluded that beauty is not truth but is a construct manufactured by advertisements. Female audiences read women shown in ads with multiple dimensions of significance and sensibility to experience the presentation and re-presentation of the women.

Keywords: advertising; beauty standard; truth; Foucault; reception analysis; Turkey; cultural studies.

Moters grožio standartų suvokimas: suvokimo tyrimas, paremtas Foucault tiesos santykiu ir tiesos žaidimais

Santrauka. Šiame tyrime aptariama, kokią įtaką reklama daro televizijos žiūrovų suvokimui apie grožį. Tyrime išsamiai analizuojamas medijų poveikis grožio ir tiesos suvokimui. Tyrimas buvo vykdomas nuo 2021 m. lapkričio iki 2022 m. gegužės, o duomenys buvo surinkti pasitelkiant individualius pokalbius su 22 moterimis nuo 18 iki 63 metų amžiaus. Gauti duomenys buvo interpretuojami naudojant Stuarto Hallo kodavimo / dekodavimo modelį bei Peirce’o trichotomiją ir Foucault tiesos santykį ir tiesos žaidimus. Tyrimo metu nustatyta, kad viena iš naujų reklamos funkcijų yra suteikti galimybę žiūrovėms asmeniškai įvertinti fizinio grožio standartus, ir padaryta išvada, kad grožis nėra tiesa, o reklamos sukurtas konstruktas. Moterų auditorija mato moteris, vaizduojamas reklaminiuose skelbimuose, įvairiais reikšmingumo ir jautrumo aspektais.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: reklama; grožio standartas; tiesa; Foucault; suvokimo analizė; Turkija; kultūros studijos.

Received: 2022-08-15. Accepted: 2023-03-05.

Copyright © 2023 Hasan Gürkan, Aybike Serttaş. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The advertising industry has been trying new applications for target audiences (Arens, 2002; Gill, 2008; Sheehan, 2013). Advertisements shape the ideal of beauty perception, playing an active role in determining individuals’ attitudes toward body and appearance (Bordo, 2003; Cash et al., 1990; Grogan, 1999; Lennon et al., 1999). Studies (Cash et al., 2002; Hargreaves et al., 2003; 2004; Jung et al., 2003; Richins, 1991) have stated that individuals experience mental problems in the face of the idealized beauty promoted by advertisements. Some studies (Grogan, 1999; Levy-Navarro, 2009; Milkie, 1999) show that women are highly critical when media images differ from reality. Therefore, understanding how women react to women they see in advertisements is essential when evaluating reactions to advertising and brand attitudes.

Beauty advertisements have a significant impact on consumer perceptions of beauty. According to Knobloch and Janiszewski (2009), exposure to idealized images of beauty in advertising can lead to negative self-perception and body image dissatisfaction among consumers. This is supported by a meta-analytic review that found that the experimental presentation of thin media images can decrease body satisfaction (Groesz et al., 2002). One reason is that advertisements often present unrealistic or unattainable beauty standards, which can cause individuals to compare themselves unfavorably to the models featured in the ads (Knobloch et al., 2009). This can lead to feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem, particularly among those who do not feel that they meet the standards of beauty presented in the advertisements (Posavac et al., 1998).

In addition to presenting unrealistic beauty standards, advertisements often reinforce narrow and culturally specific notions of what is attractive (Knobloch et al., 2009). This can lead to pressure to conform to certain beauty ideals and can have a particularly damaging impact on individuals who do not fit these standards (Slater et al., 2006). Overall, the impact of beauty advertisements on consumer perceptions of beauty is complex and multifaceted. While they can have a positive effect by promoting products and techniques that enhance appearance, they can also have negative consequences by presenting unrealistic and culturally specific beauty standards and reinforcing negative self-perception and body image dissatisfaction.

According to Baudrillard (2018, p.172), the rediscovery of the body is primarily through objects. Women commonly devote themselves to perfumes, massages, and cures in the hope of reinventing their bodies, and Rocha (2013, p. 7) has stated that the body is central to a woman’s individuality. The image fixed to feminine identity in advertisements is of a silent woman with a body. Although these words related to the body are forbidden, women have to know how to use them (Rocha, 2013, p. 10). Xu (2019, p. 2) claims that by adding signs and associations to the advertised products, the value of the products is inextricably intertwined with their artificial relationships. A beautiful woman should be associated with the woman’s image and the use of beauty products and services. A woman, a beautiful female as a cultural symbol, reveals how the media disciplines women in terms of written features such as beautiful skin tones, body shapes, stylish clothes, and temperament. When beautiful women are accepted as attractive, they function as a symbolic form of capital that provides prestige and sociocultural distinction.

It seems crucial to know more about how media and advertising can impact people’s perceptions and behaviors and lead to the emergence of shared perceptions and the development of norms of behaviors. The study assumes that such perceptions do not emerge naturally and spontaneously but are constantly shaped and discursively constructed through advertising. This work is based on Michel Foucault’s (1980) claim that truth, mentioned in his work Truth and Power, is a part of the world and produced by more than one form of restriction. This study rests on the concept that every society manages its truths, and its analysis assumes that beauty is a perception shaped by advertisements. The concept of truth was central in Foucault’s thought to show how any period of time and society builds its own regime of truth. The truth is, for Foucault, a construction from which emerges a normalization process as people’s behaviors tend to conform to what they perceive as truth and its underlying norms of behaviors. Foucault’s concept of truth relations offers a critical framework for understanding the complex and often hidden ways in which power and knowledge intersect in society. This article explores how Foucault’s truth relations concept can be applied to the analysis of advertisements and highlights how advertisements serve as a site of power and control in contemporary society. This study questions whether ads cause the perception of beauty to become truth. The study conducted in-depth interviews with 22 women to determine whether female characters’ physical appearance in advertisements defines beauty characteristics for audiences.

Literature Review

Body Perception and the Media’s Construction of Beauty and in the Truth Era

Foucault (1980) argues that there are specific historical and cultural rules about the mode of connection and diffusion of truth. In addition, any system of regulations is a finite system of constraints and limitations. Like his other categories, truth is a historical category in Foucault’s work. His work can also be seen as an attempt to make a history of truth. According to Foucault (1980), this history for the Western world is the history of an irresistible obligation to find the truth, search for it, express it, and honor a specific group with the privilege of reaching it.

Foucault is concerned with how the rules that rank or limit what is called truth are historically constructed. In his archaeological excavations, he tries to reveal not a fixed structure but a kind of layer in which this limitation, the truth-granting relations, will become visible, the interface between truth and power, knowledge and power. According to Foucault (1980), truth is produced. These truth productions are not separate from power and power mechanisms; because these power mechanisms enable and lead to these truth productions, these truth productions have potent effects that bind and unite us. What interests him is the truth/power, knowledge/power relations. In this case, this layer of objects, or rather this layer of relations, is difficult to grasp since no general theory can more or less understand them.

Foucault (1980) states that what is to be understood as truth is not some general norm or a set of propositions. Instead, truth should be understood as “a set of procedures that enable everyone to utter utterances that will be accepted as true at any time.” According to Foucault (1980), truth is not an objective and universal reality that exists independently of human thought and language. Instead, he argues that truth is a social construct that is produced and maintained by power relationships within a given society. He refers to this process as power-knowledge, in which knowledge and truth are produced, disseminated, and maintained through exercising power. Foucault believes that the production of truth is not a neutral or objective process but rather one that is shaped by the interests, values, and ideologies of those who hold power. He argues that the dominant power structures of a society determine what counts as truth or valuable knowledge and that this knowledge is used to justify and reinforce the existing power dynamics. Foucault (1984) also argues that the pursuit of truth is not a neutral or objective process but rather one shaped by the interests and values of those seeking it. He believes that the desire for power often drives the pursuit of truth and that the search for truth is often used to legitimate and reinforce existing power structures.

One way in which advertisements exert their power is through language and imagery. Advertisements often employ language and imagery designed to appeal to our emotions and desires rather than our reason (Barthes, 1957). This can be seen in the use of slogans and catchphrases that seek to tap into our fears, hopes, and aspirations, as well as in the use of attractive and aspirational imagery that presents an idealized and often unrealistic view of the world. By presenting a distorted view of reality, advertisements seek to shape our understanding of the world in ways that serve the interests of the advertisers. Another way in which advertisements exert their power is through the creation of needs and desires. For instance, advertisements often seek to create a sense of dissatisfaction with our current circumstances and to present the advertised product or service as the solution to this dissatisfaction (Veblen, 1899). This can be seen in how advertisements often present an idealized version of reality, in which the advertised product or service leads to happiness, success, and fulfillment. By creating a sense of need or desire for the advertised product or service, advertisements seek to shape our behavior in ways that serve the interests of the advertisers. Moreover, inspiring artists and researchers alike, beauty is a concept whose definition has changed over the centuries (Cross et al., 1971; Dion et al., 1972; Alley et al., 1992). Nevertheless, it has always been of interest to media professionals, especially advertisers. In this sense, some studies (Bower et al., 2013; Stephans et al., 1994; Solomon et al., 1992; Kilbourne, 2000; Kamins, 1990; Sutton, 2009) deal with how the advertising industry constructs beauty.

Beautiful is an adjective that generally denotes something we desire and are drawn to, according to Umberto Eco, who focuses on beauty from pre-Christian times to the present. Beauty is not absolute or fixed but varies in form depending on its time and place; this applies not only to physical beauty but also to the beauty of God or ideas. From time to time, beauty is associated with moderation, harmony, and even symmetry when we consider something evenly proportioned to be beautiful (Eco, 2006). The representation of beauty in the media and its effects on women have been studied mainly concerning social media in recent years (Chua et al., 2016; Mills et al., 2017; Wolf, 2019; Fardouly et al., 2016). Fardouly et al., (2016) report that social media use is associated with negative body image and that though studies show short-term exposure to Facebook does not negatively affect body image, appearance comparison is connected to social media and body image. In a study using selfie photographs (Mills et al., 2018), women who posted selfies on social media reported feeling more anxious, less confident, and physically less attractive than controls, even when they were able to take and retouch their selfies. The study is critical because it is the first experimental study to show that taking and sharing selfies causes adverse psychological effects for women.

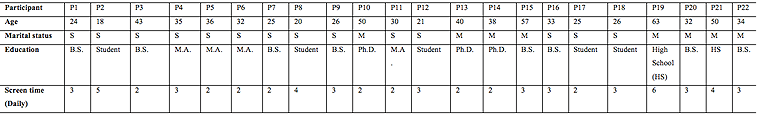

The Framework of the Study

This study has undertaken reception analysis based on the coding-decoding theory developed by Stuart Hall. Tomaselli (2016) states that the interpretant in Hall’s model is the key to understanding how interpreters behave; the interpretants make sense of the signs related to discursive context and then respond. While Peirce highlights how the signs work, Hall and contemporary media scholars have developed theories of how interpreters work. Hall discusses three ways of responding to texts. Coding-decoding describes communication as a comprehensive process that does not depend solely on transmitting the message with a viewer who is active, not passive. Audience reception focuses on interpretation processes, placing these processes in the context of domestic, cultural, discursive, and motivational-related strategies that exist before and after monitoring (Tomaselli, 2016; Hall, 1993; Livingstone, 2003). This model explains the relationship of a television program with the audience with three analytical options. The audience looks at the television program and then finds meaning, makes sense, and produces meaning, but they are not aware of this code explanation process because extracting meaning from a television program is something the audience constantly does (Serttaş et al., 2015). Hall argues that not all people will see a text the same way. The audience receives the content of their through dominant reading, negotiated reading, and opposite reading. In the dominant reading the audience and the sender have the same cultural judgments, rules, and assumptions; in this case, there is a little communication problem between the receiver and the sender. In the negotiated reading, the receiver exposes the sender’s message from the dominant cultural and social perspective; in this case, messages are primarily understood but received differently from the dominant reading. In the opposite reading, the audience sees the text as the other party wants; still, in this case, due to social beliefs, the audience also sees meanings that the sender does not intend to transmit (Hall, 1993, pp. 101-103). Like Hall, John Fiske argues that audiences are not passive while watching television and even perceive programs in ways that producers cannot guess; this refers to the assumptions of uses and gratifications theory. Accordingly, the audience receives the messages hidden in the TV narrative and deals with the meaning (Fiske, 1987, p. 79). Some scholars (Peirce, 1953; Tomaselli, 2016) contend that there are three kinds of interpretants: (i) the immediate, (ii) the dynamical and (iii) the final. The interpretant is divided by different responses: (i) the emotional, (ii) the energetic, and (iii) the logical. While the emotional adresses to a sign, on the other hand, the energetic covers an effort, and the logical is a part of ideology. This study, in November 2021 and May 2022, collected reception data through individual interviews with 22 women aged 18 and 63. Participants first watched TV broadcasting commercials randomly compiled from mainstream primetime media. According to the October 2020 data of Turkey Monitoring Research Corporation (TIAK), the most-watched channels in prime time in Turkey are ATV, Show TV, Fox TV, and TV 8. TIAK calculated the prime time hours as 18.00-24.001. All interviews lasted between 30 and 90 minutes. All participants completed a short demographic questionnaire asking basic information about age, income, education, and media consumption habits. In this context, the participants cover three generations: 6 participants are X, 11 participants are Y, and five are from Z generation. In the study, the number of participants from the Y generation, which has the highest purchasing power and the most crowded population, is the highest, while X and Z are close to each other. Many factors, such as generational differences, experiences, and knowledge, cause similarities and differences in views. The distribution of women participating in the study follows.

Table 1. Participant details

The average age of the participants is 32. The screen time of the participants is, on average, 2.8 hours per day; this includes television and OTTs (such as Netflix and Apple TV). No significant relationship was found between age, education level, marital status, and screen time. Women with positive definitions of emotional conditioning do not see beauty as a competitive pursuit or a goal to be achieved. Only one participant who has children tries to set a positive example for her children with a cognitive modeling concern and tries to take precautions to prevent them from obsessing over beauty. Based on this information, the educational status of the participants can be diversified in the future studies, and questions may be asked about the social media’s use and screen time. In interviews, all participants defined beauty similarly. Regardless of whether or not they acknowledged reality, the image of beauty in each participant’s mind is similar to the description of a conventionally beautiful woman. The only difference is that some participants question the naturalness of this beauty, while the vast majority do not.

While compiling the interview notes, a code was given to each participant. The names of the participants were coded with the letter P and a number, and the coding started with P1.

The study seeks answers to the following research questions:

RQ1: Is beauty a truth in the advertising industry?

RQ2: How does the audience perceive beauty stereotypes?

Participants were asked the following questions during the face-to-face interview: (i) In the commercials you watch, how do the women look? (ii) Do women in the commercials you watch influence your product/service and brand buying behaviors? (iii) Do female characters in the commercials you watch undermine your self-esteem? The relationship between advertising and meaning in this study can be summarized as follows: The examination of an issue is based on autoethnographic relations (Brigg et al., 2010) that can provide explanations about more traditional and political characteristics or behaviors. This study mainly focuses on accessing meaningful, accessible, and evocative research based on personal experiences. It will sensitize readers to issues of identity politics, silenced affairs, and forms of representation that enable them to empathize with people (Ellis et al., 2011). The findings part of the study, which was framed using an in-depth interview technique (Gürkan, 2019), describes the answers, experiences, perceptions, and perspectives of the researchers within the scope of the questions posed to the participants.

Findings and Discussion

This study combined two research techniques to collect, assemble and edit the data from multiple perspectives: In-depth Interviews and Reception Analysis. Each technique revealed aspects of a subject-audience, which is also multiple and variable, forcing us to rely on a criterion of simultaneity rather than causality. Reception analysis enabled us to define concisely and functionally our areas of interest in the subject-audience relationship we were investigating. In addition, these readings are fully articulated with the subject of beauty.

The researchers determined the research questions within the scope of the study’s purpose by watching the advertisements broadcast on TV channels in primetime. They conducted one-on-one in-depth interviews to collect data from the study subjects and then examined and compared the subjects from different sociocultural backgrounds, values and ideologies. Themes and concepts identified in the one-on-one in-depth interviews conducted by the researchers were coded according to three categories: (i) Dominant Readings, (ii) Negotiated Readings and (iii) Oppositional Readings. Dominant readings result when the reader does not question the authenticity of the advertising messages. Negotiated readings result when the reader is affected by the advertising messages despite being fully aware that these messages contain elements of fiction. Oppositional readings result when the reader recognizes, understands and opposes the advertising messages wholly. In the ads, the researchers identified sub-themes pertaining to personal attractiveness, modernism, reality and fiction, and logic. These included women’s beauty perceptions; participants’ beauty preferences and socioeconomic status; participants’ readings on the female characters in advertisements; and participants’ readings on an attractive woman. The study uses Hall’s coding-encoding theory and Peirceian trichotomy to tie the signs to discourse, philosophy and the phenomenology of the human condition. The table below presents the multiple dimensions of significance and sensibility for women to experience the presentation and re-presentation of the women (as discussed by Arendt, 1958; Tomaselli, 2016).

Table 2. Hall and Peirce concept for reception analysis

|

|

ACT |

|||

|

Participant |

Encoding |

Decoding |

Representamen |

Interpretant |

|

P1 |

Beauty is the power |

Beauty is a need |

Star, image, brand design |

I should buy this product |

|

P2 |

Trust the star that is used in the advertorial |

She is the definition of beauty |

Star, image, brand design |

I trust and admire her |

|

P3 |

The products have similar effects to plastic surgery |

Beauty can be formed with plastic surgery or with those products |

Star, image, brand design |

I must use any way possible to stay beautiful, including surgery and beauty products |

|

P4 |

Beauty can be consumed |

Beauty is expensive |

Star, image, brand design |

I should buy this product |

|

P5 |

Beauty is a need |

Product is more important |

Star, image, brand design |

I need to know that the product I buy is functional and meets my needs, I can find it easily and I can afford it |

|

P6 |

Beauty is a necessity |

We care about the appearance of the people in our ads |

Star, image, brand design |

I like looking at beautiful people |

|

P7 |

Beauty is a privilidge |

Beautiful women represent elite brands |

Star, image, brand design |

I admire this woman and the products associated with her |

|

P8 |

We create beauty with technical details |

Beauty can be created with cinematic tricks |

Star, image, brand design |

I can tell how beauty is created |

|

P9 |

Beauty is powerful |

Feel the power and shape yourself if you need it |

Star, image, brand design |

Ordinary women do not attract my attention |

|

P10 |

Beauty is powerful |

Beauty can be achieved with our product |

Star, image, brand design |

My daughters wanted to buy products represented by a pop star, which made me think a lot |

|

P11 |

Thin is beautiful |

Beauty is equal to being fit |

Star, image, brand design |

I must lose weight |

|

P12 |

Beauty is powerful |

Beauty and youth are tools |

Star, image, brand design |

I must stay young and beautiful |

|

P13 |

Beauty pays and this is a market |

The audience wants to watch beautiful people |

Star, image, brand design |

I have good relations with the ones I love, and I don’t want to waste energy on such matters |

|

P14 |

Beauty is powerful |

In the past, the world was shaped by ideas, now it is shaped by beauty |

Star, image, brand design |

Media industry has taught us how to be beautiful |

|

P15 |

Beauty is powerful |

Ads are impressive in buying the products |

Star, image, brand design |

Any woman I see in advertisements does not make me question my physical characteristics |

|

P16 |

Beauty is powerful |

Sex sells |

Star, image, brand design |

The women I see in advertisements sometimes cause me to question my own body |

|

P17 |

Beauty is powerful |

Beautiful women influence your purchasing behavior |

Star, image, brand design |

The women I see in advertisements are unrealistic |

|

P18 |

Beauty is powerful |

Ads are fictional, but they are still impressive in manipulating purchasing behavior |

Star, image, brand design |

The women I see in advertisements do not cause me to deal with my own body |

|

P19 |

Beauty is powerful |

Product may be more important |

Star, image, brand design |

I don’t compare myself to any of the women I see in advertisements |

|

P20 |

Woman must not age |

Beauty has some universal standards |

Star, image, brand design |

The women I see in advertisements make me evaluate my physical characteristics |

|

P21 |

Beauty is a must |

Beautiful women are a part of the beauty project |

Star, image, brand design |

I do not compare myself the women I see in advertisements |

|

P22 |

Beauty is a must |

Show business needs beauty |

Star, image, brand design |

The women I see in advertisements become beautiful as a result of extraordinary efforts |

Dominant Readings: the reader does not question the authenticity of the advertising messages

The advertising industry contributes to consumer decision-making and influences consumer choices (Aaker 1997; Hoeffler et al., 2002; Becker-Olsen et al., 2006; Madrigal et al., 2008). Women admit that pressure to look physically attractive is a reality. Advertisements play an important role in stereotyping women (Kilbourne 2010; Gill et al., 2014; Grau et al., 2016) but not every woman acknowledges this role of advertisements. Besides, Knobloch et al. (2009) and Posavac et al. (1998) state that exposure to idealized images of beauty in advertisements can lead to negative self-perception and body image dissatisfaction among consumers. P1, P4, P11, and P12 (selected expressions given below), in comparing themselves with the women in the ads they watched, admitted to feeling incomplete and to being sometimes affected by the aesthetic atmosphere created in the ad, even though they did not perceive the advertising message fully. For example, P1 states that women seem to belong to another world on TV, adding they are stunning and seem happy.

I look at them, but I think they are not real. We don’t see such women when we go out on the streets anyway. While watching the commercial, I sometimes turn to look at myself. I like myself, but I’m not as beautiful as the women in commercials. I remember the brands that use celebrities in their ads, and if I need a product, I give priority to these brands (P1).

Moreover, these women said that beauty is a project. For instance, P4 puts the beauty order as follows:

Feeling beautiful is important to me. I do a lot of research for my make-up items. I watch all advertisements, take notes, research products. Beauty is a demanding thing. Even though I don’t meet all of the classical beauty criteria, I’m beautiful. If you ask what classical beauty criteria are, the first things that come to my mind are tall height, long neck, thick hair, big eyes, and beautiful skin- being slim, long legs. In these advertisements, some women always resemble what I told; none of them are different. When I look at them, I can see what I can do for myself. It is costly and inconvenient (P4).

These women see being attractive as an advantage and brutally criticize themselves. They also emphasize that the female celebrity in the ad, importantly, makes the ad memorable. P2, P11, and P12’s comments:

I am a fan of Tuba Büyüküstün2. I think she’s the definition of beauty. I watch all the commercials she plays. I trust the products she promotes. I know I can’t be like her, but still buying those products makes me feel good. It’s not easy to be so beautiful when you say I can’t be like her. I find myself attractive too (P2).

I am surprised the moment I see a thin woman. On social media, the accounts of overweight and fit women reached hundreds of thousands or even millions of followers. This situation made me feel a little more normal (P11).

Many people say that I am beautiful. I play with myself as I see that there are ways to be even more beautiful. I think beauty is power, and why shouldn’t I have that power when I’m young? (P12).

Negotiated readings: the reader is affected by the advertising messages but knows the messages contain fiction

As Jhally (1995) points out, advertising is the most influential socialization institution in modern society. Cook (2001) states that ads persuade, influence, and change ideas, building identities and attitudes. Ideal female figures are stereotyped through ads. The image constructed for the female identity in advertisements is standard. Constructed meanings about the body manipulate women (Rocha, 2013; Xu, 2019). In this context, the image of women should be associated with the use of beauty products and services. Lau and Zuraidah (2010) state that advertising subtly distorts reality and manipulates consumers to buy a lifestyle alongside goods. Women who are affected by the advertising messages but are aware they are fiction agree that the most prominent theme in the advertisements is the ideal.

P3, P9, P6, P7, and P8 are affected by the ads and the profiles they follow on social media. They emphasize that all the women they follow are really beautiful. These participants, who do negotiated reading, are aware that cameras and light tricks are used to make women look more beautiful in the advertisements they watch, make-up is important or use Photoshop. They see the functioning system but still approve of its commoditization of the female body. This group, who says that the advertisements do not reflect the truth, still make an effort to be beautiful and criticize their efforts to this end. It is also noteworthy that one of the participants identified beauty with happiness and peace. P3 and P20 state they are affected by the ads and the profiles they follow on social media though they add that they are not real:

I examine myself very much, and I look in the mirror a lot. I follow the accounts of plastic surgeons on social media. I can tell you what procedures are in all of the women in these advertisements. So these women are not real. Yet they are lovely. The more I look at them, the better the definition in my mind develops. Sometimes the product has a contribution; sometimes, it is the plastic surgery (P3).

The female characters change in the advertisement, but we generally come across women who do not age and look beautiful. The women I see in ads do not affect my purchase of the product. Instead, women in advertisements make me evaluate my physical characteristics (P20).

The participants (P7, P8, P22) are aware that in the advertisements they watch, make-up, lighting, camera filters, and Photoshop are used to make women look more beautiful.

Watching commercials or browsing magazines, sometimes even TV series, can feel like a torment to me. I have a weight problem, and the thinness of the women around here surprises me. Some of these women become mothers, and after a few months, they are just small again. Yes, there are some tricks, but they’re still lovely. When I see them, my excesses sink into my eyes. Therefore, when a beautiful woman becomes the face of a brand, I inevitably feel admiration for that brand (P7).

We know that the beauty of women in the ads is artificial, like light tricks, make-up, and so on. For me, beauty is thinness, smooth skin, being well-groomed, and having style. I can give people a beauty rating at a glance (P8).

The choices and discourses of women in advertisements rarely affect me. These women are women who become beautiful as a result of extraordinary efforts. In addition, the show business’s efforts are also significant. I do not compare myself to these women (P22).

P9 sees the functioning system but still approves of its commoditization of the female body.

I can have botox if I need it. Because I know the women in these ads are not naturally attractive. Or I thought that I would never dye my hair, but because I liked Elçin Sangu3 so much, I dyed it red for a while. In other words, beauty is shaped by what I see. Of course, the women in the advertisements should be beautiful, and it is difficult for an ordinary woman to attract my attention (P9).

Assertive, beautiful, well-groomed types of women are used a lot. Especially lately, I have seen many powerful female characters, but they are within certain limits. I see women who can cope with a lot of problems and face them alone. We know these ads are fictional, but they are impressive in buying the products. I sympathize with the chocolate that the woman I saw there ate or the cleaning material she used. However, the women I see in advertisements do not cause me to deal with my own body (P18).

P6, P15, P17, and P21 say that the ads do not reflect the truth but still try to achieve the standards of beauty they are shown and criticize themselves harshly.

As a woman, I like looking at such beautiful women. I know that it is possible to look better with Photoshop, some similar programs, and camera tricks, but they look good after all, and if I am a brand owner, I would care about the appearance of the people in my advertisement (P6).

In the advertisements, almost all women are depicted as blonde, long-haired, miniskirt, prudish women. Although I know that what I am watching is a world of fiction and lies, the women in the advertisements can effectively make me purchase that product from time to time. Still, any woman I see makes me question my physical characteristics (P15).

Most of the women in the ads are thin, make-up, high cheekbones, beautiful women. They are compressed into specific patterns. Although these women are portrayed as vital in ads, I think this is unrealistic. Although I rarely compare the women in the ads with my size, the products do not affect my buying behavior (P17).

The women in the ads are tall, long-haired, and well-groomed women. I do not prefer a product that I see in the ads. These women are purely projected women, and I do not compare my body with them (P21).

Oppositional readings: the reader recognizes, understands and wholly opposes the concept of the perfect woman that the advertisements promote

The effect of advertisements on individuals in the consumer society cannot be ignored (Turow, 2011). Many studies claim that certain unacceptable physical messages are transmitted to women (Heinberg et al., 1995; Stormer et al., 1996; Shaw et al., 1996; Harrison et al., 1997). Moreover, as Knobloch et al. (2009) point out, presenting unrealistic beauty standards makes it easy to reinforce narrow and culturally specific notions of what is often attractive in advertisements. As a result, individuals begin to conform to certain beauty ideals (Slater et al., 2006). P5, P10, P13, and P14 are aware that there is no logical link between the products in the advertisements they watch and the beauty of the female characters in those advertisements. For example, P5 and P10 state that the advertisements they watched did not cause them to rate their beauty. Because these participants think that beauty is industrialized and turned into a concept, which has a financial equivalent:

Everyone is attractive on TV. So it is in these ads. Except for the advertisements for some products, all women look like models. I don’t know why they are chosen that way, but I know they are not like that in real life. I guess advertisers are afraid of selecting ordinary people. However, I need to know that the product I buy is functional, the price is affordable, meets my needs, and I can find it easily. Yes, a beautiful woman catches my attention, but I cannot be like that woman when I buy it. I believe these dreamy characters in commercials mainly affect young girls negatively (P5).

I watch television with my daughters from time to time. A few years ago, there was an advertisement starring Hadise4. They wanted to buy products of that brand. It made me think a lot. At this age, I did not like to see that they were affected so much and I tried not to let them watch TV for a long time. My daughters pay attention to their weight at this age, they do their hair for hours, clothes are important as well. I want them to be well-groomed, but I’m trying not to obsess over it. They watch Korean dramas. They did not want to sunbathe this summer, as everyone in Korean dramas is White (P10).

None of the women are realistic, they’re exaggerated, and celebrity acting destroys credibility. If daily, familiar words are spoken in advertisements, it affects my purchase of the product. I don’t compare myself to any woman I see in commercials because I know it’s not real (P19).

On the other hand, P13, P14, and P16 stated that the media and advertisers determining the criteria for beauty should feel responsible for the pressure they create. Participants also said that they limited their use of traditional media and social media to stay away from this pressure:

I have a boyfriend, friends, and a family. I have good relations with all of them, and I don’t want to waste energy on such matters. Sometimes I think to dye my hair, and then I give up. I love looking at beautiful women in the media, I sometimes say “wow” but their job is to be beautiful. It is a market, after all, and they’re also doing a reasonable premium. We are in a time when everything turns into money. Beauty pays well too. There are beautiful people in commercials, news, TV series, movies and everywhere. I think the audience wants to watch beautiful people. It is a matter of supply and demand (P13).

Some used to shape the world with their thoughts in the past, now some direct them with their beauty. How does that happen? I think it happens thanks to the power of media. They have taught us how to be beautiful. There was the subject of beautiful women in the past too, but it was not talked. Now we are focused on beauty. And were there so many plastic surgeons in the past? I do not think so. Doctors are also very active now. Yes, these ads affect us either, but we know they are just ads. On social media, you inevitably start comparing the beautiful with yourself. You should not watch ads and you should limit the time you spend on social media. Even the way of thinking of people changes with constant exposure (P14).

In ads, I see thin women with long hair, tall, with make-up, often wearing revealing outfits (sometimes so revealing as to point to sexuality directly). The women in the advertisements do not affect my product purchasing preferences, but they affect the general public that we see the same types of women on the street in everyday life. These women sometimes cause me to question my own body because a general perception of beauty is drawn (P16).

The subject of beauty, along with body perception and the representation of women in different media products, has been discussed in the context of gender studies and women’s studies, but the question of whether beauty is a truth has not been examined. The participants interviewed revealed that the advertising discourse includes the reconstruction of reality (as well as the ideal, the imagined, the desired) as well as the reconstruction of the definition of female beauty. Advertising discourse is continually produced and can reach large masses, and the endless repetition of these discourses increases the impact of the messages. This advertisement, which is produced, serves the truth audience’s motives for approval, self-affirmation or seeking the ideal for themselves. Truth discourse in advertising is constantly being produced and simultaneously reaching large masses. This discourse corresponds to a concept, that those who produce and those who receive the messages unwittingly agree on in the industry. In this case, truth comes into play at the point where the average and pure reality for the audience lose its function.

As shown in Table 3, results point to various oppositions between shared perceptions and ways of norm accumulation that divide the women’s perception, constituting an ambivalent state where cultural values are relatively separated. Seeking the truth in advertisements can be perceived as an attempt to restore Foucault’s truth games, how objects that have become the benchmark of power relations at a particular moment are reinstated. Moreover, Table 3 also expresses how women produce, approve and perceive beauty through Foucault’s concept of truth relations.

Table 3. The complex field of women’s beauty perception

|

Perception shaped by family, social and cultural norms |

Beauty constructed with Foucault’s truth relations and truth games |

|

i. More critical attitude ii. More compatible iii. Anti-establishment iv. Following the role models v. Regional norms and Global norms |

i. Beauty as a symbol ii. Beauty as a need iii. Beauty as power iv. Beauty as a must v. Beauty as privilege |

Conclusions

The interviews with the 22 study participants made it possible to categorize advertising messages based on coding. Accordingly, the vast majority of advertisements are coded with the message saying that beauty is absolute power. In advertisements, the perception of beauty is represented by a star character, brand image, and design. According to research, 12 participants believe in advertising messages and want to be unconditionally beautiful. However, 6 participants know that the women they see in the advertisements are unrealistic and are satisfied with their physical characteristics. Four participants emphasized that beauty is a feature that can be produced and shaped. Interestingly, there are specific beauty criteria that all women in the study see as universal and standard, such as thinness, full hair, extended height, white skin, and colored eyes. The definitions of beauty are similar even if the participants read the advertising messages as negotiated or contradictory. Although the viewers are aware that they need to question the reality of these women, they still want to be like them. If these women are a blend of fantasy, fiction and design, does natural beauty exist? The study sought answers to all these questions by collecting and analyzing data from a female audience with different demographic characteristics. Although some viewers know that beauty in advertising is truth, their belief in it is unshaken. The number of female viewers aware of the illusion on the screen is relatively low.

Foucault’s concept of truth relations refers to how society produces, validates, and disseminates knowledge and information. According to Foucault, truth is not an objective reality that exists independently of human interpretation but is produced and reproduced through a complex system of power relations (Foucault, 1972). In other words, the knowledge accepted as accurate within a given society is shaped by the power dynamics within that society and is often used to reinforce and maintain existing power relations. This concept can be particularly illuminating when applied to the analysis of advertisements, a ubiquitous feature of modern society. Advertisements play a significant role in shaping our understanding of the world, as they often present a selective and distorted view of reality to promote a particular product or service (Lefebvre, 1984). As such, advertisements serve as a site of power, as they seek to shape our beliefs and behavior in ways that benefit the advertisers. For Foucault, since the object is produced with words and discourses, conformity with its thing can only consist of conformity with the historical modalities in which the object is constructed. With this approach, it is correct to speak of truth relations rather than truth in the narrow sense. At this point, like every society, Turkey also organizes its truth relations. In the study, there are the types of discourse that women accept as truth, the mechanisms used to distinguish between true and false statements, the techniques and procedures used in reaching the truth, and the special statuses they give to those responsible for telling the truth. Similarly, with these relations, which Foucault calls truth games, which means determining under what conditions and depending on what conditions advertisements gain importance for the field of knowledge. As a result of the interviews in this study, a new function emerged related to the abstract features attributed to the advertised products and not directly designed by advertisers for this purpose. This function lets the advertisement narrative change the viewer’s perception, leaving aside the concrete benefits of the product/service for the viewer. Advertising has created an act of self-reflection in the vast majority of the target audience, in any case of the type of product/service, where it is considered the person’s physical characteristics. Regardless of the advertising content, its cinematography becomes a text that sets the aesthetic standards of the audience with the female characters it creates and dictates standards of physical perfection to most viewers. The advertisement text has become a media product independent of sales, which causes the audience to design their beauty. Some viewers buy products/services that they identify with the woman’s beauty in the advertisement. Still, for some, the advertisement is a production in which only the beautiful woman is watched.

Beauty has become a symbol of product/service functionality, quality, and desirability for viewers, who identify the advertised product with the idealized women in the product/service advertisements. All participants think beauty is a compelling feature, and body image is an issue for all of them. According to the participants who buy the product/services in the advertisements they watch, the commercials reflect and determine the beauty trends according to Hall’s three different coding and encoding actions. An issue the study underscores, and one that other studies should examine in detail, is that women who have spiritual satisfaction and express happiness with their immediate surroundings do not prioritize beauty. These women stated that they know that advertisements shape contemporary beauty standards and try to keep their children away from these influences and limit their media use to this end. Finally, according to this study’s participants, the perception of beauty is fed by social media simultaneously with traditional media. A future study of the role of beauty in social media, which this study’s participants constantly emphasize in their statements, can contribute significantly to the discourse on the construction of beauty standards. In conclusion, Foucault’s truth relations concept offers a valuable framework for understanding the complex and often hidden ways in which power and knowledge intersect in society. When it is applied to the analysis of advertisements, this concept highlights how advertisements serve as a site of power and control, shaping our beliefs and behavior in ways that benefit the advertisers. Moreover, further research can be done with data mapping methods on Twitter and other micro-blogs with similar keywords. With this method, perception analysis can be carried out, and more female consumers can be reached.

References

Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 347–356. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151897

Alley, T. R., & Cunningham, M. R. (1991). Averaged faces are attractive, but very attractive faces are not average. Psychological science, 2(2), 123–125.

Arens, W., & Weigold, F. (2002). Contemporary Advertising and Integrated Marketing Communications. McGraw-Hill.

Arendt, A. (1958). The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press.

Barthes, R. (1957). Mythologies. Seuil.

Baudrillard, J. (2018). Tüketim Toplumu. Ayrıntı.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.01.001

Bordo, S. (2003). Unbearable weight: Feminism, Western culture, and the body (10th anniversary ed.). University of California Press.

Bower, A. B., & Landreth, S. (2013). Is beauty best? Highly versus normally attractive models in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2001.10673627

Brigg, M., & Bleiker, R. (2010). Autoethnographic international relations: Exploring the self as a source of knowledge. Review of International Studies, 36(3), 779–798. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210510000689

Cash, T. F., & Pruzinsky, T. (1990). Body images: Development, deviance, and change. Guilford.

Cash, T. F., & Pruzinsky, T. (2002). Future challenges for body image theory, research, and clinical, practice. In T. F. Cash & T. Pruzinsky (Eds.), Body images: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice (pp. 509–516). Guilford Press.

Chua, T. H. H., & Chang, L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Behaviour, 55(A), 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.011

Cook, G. (2001). Discourse of advertising. Routledge.

Cross, J. F., & Cross, J. (1971). Age, sex, race, and the perception of facial beauty. Developmental Psychology, 5(3), 433–439. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0031591

Dion, K., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1972). What is beautiful is good. Journal of personality and social psychology, 24(3), 285–290. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0033731

Eco, U. (2006). Güzelliğin Tarihi. Doğan.

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An Overview. Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, 36(4(138)), 273–290.

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2016). Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.005

Fiske, J. (1987). Active Audiences, and Pleasure and Play Television Culture. Methuen.

Foucault, M. (1984). The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1980). Truth and power. In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, (pp. 109–133). Pantheon Books. (Translated by Colin Gordon.)

Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge. Tavistock.

Gill, R. (2008). Empowerment/sexism: Figuring female sexual agency in contemporary advertising. Feminism & Psychology, 18(1), 35–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353507084950

Gill, R., & Elias, A. S. (2014). ‘Awaken your incredible’: Love your body discourses and postfeminist contradictions. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics, 10(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1386/macp.10.2.179_1

Grau, S. L., & Zotos, Y. C. (2016). Gender stereotypes in advertising: a review of current research. International Journal of Advertising, 35(5), 761–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1203556

Groesz, L. M., Levine, M. P., & Murnen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10005

Grogan, S. (1999). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women, and children. Routledge.

Gürkan, H. (2019). The experiences of women professionals in the film industry in Turkey: A gender-based study. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies, 16(1), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.2478/ausfm-2019-0011

Hall, S. (1993). Encoding/Decoding. In S. During (Ed.), The Cultural Studies Reader (pp. 90–103). Routledge.

Hargreaves, D. A., & Tiggemann, M. (2003). The effect of “thin‐ideal” television commercials on body dissatisfaction and schema activation during early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(5), 367–373. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1024974015581

Hargreaves, D. A., & Tiggemann, M. (2004). Idealized media images and adolescent body image: “Comparing” boys and girls. Body Image, 1(4), 351–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.10.002

Harrison, K., & Cantor, J. (1997). The relationship between media consumption and eating disorders. Journal of Communication, 47(1), 40–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1997.tb02692.x

Heinberg, L. J., Thompson, J. K., & Stormer, S. (1995). Development and validation of the sociocultural attitudes towards appearance questionnaire (SATAQ). International Journal of Eating Disorders, 17(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199501)17:1%3C81::AID-EAT2260170111%3E3.0.CO;2-Y

Hoeffler, S., & Keller, K. L. (2002). Building brand equity through corporate societal marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 21(1), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.21.1.78.17600

Jhally, S. (1995). Image-based culture. Advertising and popular culture. In G. Dines & J. M. Humez (Eds.), Gender, race and class in media. A text-reader (pp. 77–88). Sage Publications.

Jung, J., & Lennon, S. (2003). Body image, appearance self‐schema, and media images. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 32(1), 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X03255900

Kamins, M. A. (1990). An investigation into the “match-up” hypothesis in celebrity advertising: When beauty may be only skin deep. Journal of Advertising, 19(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673175

Kilbourne, J. (2000). Beauty and the Beast of Advertising. In B. K. Scott, S. E. Cayleff, A. Donadey, & I. Lara (Eds.), Women in Culture: An Intersectional Anthology for Gender and Women’s Studies (pp. 183–185). Wiley Blackwell.

Kilbourne, J. (2010). Killing us softly 4: Advertising’s image of women [Documentary]. The Media Education Foundation.

Knobloch, L. K., & Janiszewski, C. (2009). The impact of advertising on body image concerns among women: An examination of the role of appearance schema activation. Journal of Social Psychology, 149(2), 153–163.

Lau, K. L., & Zuraidah, M. D. (2010). Fear factors in Malaysian Slimming Advertisements. https://docplayer.net/22587662-Fear-factors-in-malaysian-slimming-advertisements-lau-kui-ling-zuraidah-mohd-don.html

Lefebvre, H. (1984). The Production of Space. Blackwell.

Lennon, S. J., Lillethun, A., & Buckland, S. S. (1999). Attitudes toward social comparison as a function of self‐esteem: Idealized appearance and body image. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journals, 27(4), 379–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X99274001

Levy‐Navarro, E. (2009). Fattening queer history: Where does fat history go from here? In E. Rothblum & S. Solovay (Eds.), The fat studies reader (pp. 15–22). New York University Press.

Livingstone, S. (2003). The changing nature of audiences: from the mass audience to the interactive media user. LSE Research Online.

Madrigal, R., & Boush, D. M. (2008). Social responsibility as a unique dimension of brand personality and consumers’ willingness to reward. Psychology & Marketing, 25(6), 538–564. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20224

Milkie, M. A. (1999). Social comparisons, reflected appraisals, and mass media: The impact of pervasive beauty images on black and white girls’ self‐concepts. Social Psychology Quarterly, 62(2), 190–210. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695857

Mills, J. S., Musto, S., Williams, L., & Tiggemann, M. (2018). “Selfie” harm: Effects on mood and body image in young women. Body Image, 27, 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.08.007

Mills, J. S., Shannon, A., & Hogue, J. (2017). Beauty, Body Image, and the Media. In M. P. Levine (Ed.), Perception of Beauty (pp. 145–157). InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.68944

Peirce, C. S. (1953). Charles S. Peirce’s Letters to Lady Welby (I. C. Lieb, Ed.). Whitlock’s Inc.

Posavac, H. D., Posavac, S. S., & Posavac, E. J. (1998). Exposure to idealized images of women and men: The effects on body dissatisfaction. Sex Roles, 39(11-12), 721–734.

Richins, M. L. (1991). Social comparison and the idealized images of advertising. The Journal of Consumer Research, 18(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1086/209242

Rocha, E. (2013). The Woman in Pieces: Advertising and the Construction of Feminine Identity. SAGE Open, 3(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013506717

Serttaş, A., & Gürkan, H. (2015). Türkiye’deki Kadın İzleyicilerin Televizyon Progrmlarındaki Kadını Algısı. İstanbul Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Dergisi, 48(1), 91–111.

Shaw, J., & Waller, G. (1996). The media’s impact of body image: Implications for prevention and treatment. Eating Disorders, 3(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640269508249154

Sheehan, K. B. (2013). Controversies in Contemporary Advertising. Sage Publication.

Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2006). Body image and appearance-related concerns in young children: A review. Body Image, 3(1), 43–50.

Solomon, M. R., Ashmore, R. D., & Longo, L. C. (1992). The beauty match-up hypothesis: Congruence between types of beauty and product images in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 21(4), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1992.10673383

Stephans, D. L., Hill, R. P., & Hanson, C. (1994). The beauty myth and Female Consumers: The Controversial Role of Advertising. The Journal of Consumers Affairs, 28(1), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.1994.tb00819.x

Stormer, S. M., & Thompson, J. K. (1996). Explanations of body image disturbances: A test of maturational status, negative verbal commentary, social comparison, and sociocultural hypotheses. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 19(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199603)19:2%3C193::aid-eat10%3E3.0.co;2-w

Sutton, D. H. (2009). Globalizing ideal beauty. Palgrave Macmillian.

Tomaselli, K. (2016). Encoding/decoding, the transmission model and a court of law. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 19(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877915599611

Turow, J. (2011). The daily you: How the new advertising industry is defining your identity and your worth. Yale University Press.

Xu, X. (2019). Is “Beautiful Female Something” Symbolic Capital or Symbolic Violence? That Is a Question. SAGE Open, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019850236

Wolf, D. (2019). Desire in Absence: The Construction of Female Beauty in the Social Media Age. The Ohio State University. Department of Art Undergraduate Research Theses.

Veblen, T. (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class. Macmillan.

1 For more information please visit the page: http://tiak.com.tr/tablolar (Accessed Date: 15th January 2022).

2 A famous actress in Turkey.

3 A famous actress in Turkey, well-known with her red hair.

4 A famous female singer in Turkey.