Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2023, vol. 96, pp. 136–152 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2023.96.70

Debating Feminism on Instagram: A Critical Discourse Analysis of @LasIgualadas in Colombia

Admilson Veloso da Silva

Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary

veloso@uni-corvinus.hu

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9167-3902

Ana María Cuesta López

Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary

ana.cuestal22@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6861-6691

Abstract. The first organized feminist movement in Colombia demanded the right for women to vote in 1954 and, despite its progressist agendas and decades of work, it still tends to be distorted by traditional media representation. With social media, these activists can reach the audience directly, disseminate information, and dispute narratives. Hence, this study addresses the question: how are the discourses about feminism constructed on Instagram in Colombia? Based on netnography and critical discourse analysis, the paper analyzes the discussions on publications and comments on the most popular feminist Instagram account in Colombia, @LasIgualadas. The results indicate that the platform usage could help create a less stereotypical perspective on the movement while informing society on its agendas and raising awareness about rights violations. However, the debate on @LasIgualadas is still predominantly carried out by women (80.5%), and some topics, such as abortion and LGBTQI+ rights, are distorted or deviated from by some Instagram users’ comments.

Keywords: Instagram; Feminism; Colombia; Social Media; Critical Discourse Analysis; Netnography.

Diskusija apie feminizmą „Instagram“: kritinė diskurso analizė @LasIgualadas Kolumbijoje

Santrauka. Pirmasis organizuotas feminisčių judėjimas Kolumbijoje 1954 m. pareikalavo moterų teisės balsuoti ir, nepaisant progresyvių programų ir dešimtmečius trukusio darbo, jis vis dar nėra tinkamai atspindimas tradicinėje žiniasklaidoje. Naudodamos socialines medijas, šios aktyvistės gali tiesiogiai pasiekti auditoriją, skleisti informaciją ir ginčyti esamus naratyvus. Šiame tyrime sprendžiamas klausimas: kaip instagrame konstruojami diskursai apie feminizmą Kolumbijoje? Remiantis tinklo etnografijos (netnography) ir kritine diskurso analize, straipsnyje analizuojamos diskusijos dėl publikacijų ir komentarų populiariausioje feministinėje instagramo paskyroje Kolumbijoje @LasIgualadas. Rezultatai rodo, kad platformos naudojimas gali padėti sukurti mažiau stereotipinį požiūrį į judėjimą, kartu informuojant visuomenę apie jo darbotvarkę ir didinant informuotumą apie moterų teisių pažeidimus. Tačiau @LasIgualadas diskusijose vis dar dominuoja moterys (80,5 proc.), o kai kurios temos, pavyzdžiui, abortai ir LGBTQI+ teisės, kai kurių instagramo vartotojų komentaruose iškraipomos arba nuo jų nukrypstama.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: Instagram; feminizmas; Kolumbija; socialinės medijos; kritinė diskurso analizė; tinklo etnografija.

Received: 2023-03-21. Accepted: 2023-11-06.

Copyright © 2023 Admilson Veloso da Silva, Ana María Cuesta López. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Social media platforms, such as Instagram, play a relevant role in how our societies communicate nowadays, especially when it comes to shaping people’s perspectives and promoting activism. These platforms have boosted the visibility of feminist movements by allowing users to organize, reach, and spread information (Crossley, 2015). However, in many Latin American countries, including Colombia, stereotypes about feminists are still strong and mostly negative (Percy and Kremer, 1995; Díaz, 2022). Within the online sphere, Instagram is one of the most popular platforms with over two billion users (Kemp, 2023), and maintains a strong approach to visualities (Highfield and Leaver, 2016), thus becoming a rich field for feminists to dispute the narratives around the movement (Mahoney, 2020; García and Solana, 2019; Savolainen et al., 2020).

Taking this background of discursive disputes and technological development, the objective of this research is to analyze how discourses about feminism are constructed on Instagram in Colombia, with a focus on user engagement and the impact of language and communication styles on the page @LasIgualadas. The paper begins with a literature review regarding the main theories related to contemporary gender studies, feminism in Colombia, and new media from a communication science perspective. The empirical part consists of a multimodal research relying on the method of netnography (Kozinets, 2020), followed by the critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, 2010) of the page content posted on the feminist Instagram account @LasIgualadas, the most popular of its type in Colombia, and the discussions promoted by users in the comments section.

Considering the possibilities brought by new media and the Internet, this study explores and addresses the question: How are the discourses about feminism constructed on Instagram in Colombia? The analyzed and interpreted dataset was selected utilizing the fifth operations procedure proposed by Kozinets (2020). The sample corresponds to the page’s top 40 most interacted publications of the Instagram account @LasIgualadas from its creation up to June 2023, in addition to the five most popular comments on each post (n=200) based on reactions and replies to those comments.

The results show that 41% of commenters support the messages conveyed by Las Igualadas, indicating a predominantly supportive user base. However, 59% of commenters express negative, neutral, or undefined positions on feminism. It is worth noting that engagement with the account occurs despite differing opinions, highlighting the value of allowing interaction with contrasting perspectives. Agreeableness varies depending on the topic, with controversial subjects like abortion receiving less agreement, while violence generates more consensus. Las Igualadas utilizes a question-based style in their titles or captions, fostering critical thinking and self-reflection among users. Given the contentious nature of feminism in Colombia, commenters often employ sarcasm, irony, passive-aggressive remarks, and jokes. The language and manner in which the feminist movement and its supporters, like @LasIgualadas, convey their message can reflect societal acceptance, as language influences opinions and attitudes.

A brief perspective on gender studies and feminism

The research on gender inequality origin is diverse in scope and perspectives, tracing back to the beginning of human evolution to examine where in history the disparity started. While some streams are related to psychology and propose that physiological sex differences correlate with gendered behaviors (Mealey, 2000) other streams related to biological anthropology focus on primate behaviors and the conflict of interest between the sexes (Huber, 2016). Alternatively in their study, Collins et al. (1993), using as a basis the ecological-evolutionary theory, suggests that rather than being founded on fixed characteristics resulting from physiological sex differences, women’s secondary status is dictated by men’s control of resources and political power (Collins et al., 1993, Huber, 2016).

Pilcher and Whelehan (2004) date the emergence of gender studies as a scientific matter to the late 1960s and explain that it was triggered by the so-called second wave of feminism, which brought to the attention disparities between men and women in societies on many aspects, such as economic and political. However, for many years feminists had already been discussing and writing about their agenda based on a distinction between gender (woman) and sex (female), contrasting with biological determinist to demonstrate how social and cultural situations influenced the construction of genders, such as the contribution of Simone de Beauvoir (1949), who argued that “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”1 (p. 301). Despite the different scientific takes on this issue, no specific explanation has been reached and accepted by all as to why gender inequality exists. Nevertheless, social movements, like feminism, have promoted events and activities throughout history resulting in legislations and achievements that have helped to reduce gender inequality.

Similarly to the diversity in theories covering gender disparities, the definition of feminism is a complicated matter. According to Willemsen (1997), feminism has many forms, theories, and ideologies, making it challenging to find consensus on its definition even among the feminists themselves. “It is hardly even possible to give a definition of feminism that every feminist will agree with” (Willemsen, 1997, p.5). Feminist social movements and academic theories have described the relationship between men and women in general and the liberation of women in particular (Winter, 2010). The vast majority of definitions of feminism (Restuccia, 1987; Mclaughlin, 1993; Thompson, 1994; Castells, 1996) agree on one thing: feminism is characterized as a movement that seeks the equality of the sexes. Definitions like this are found in various sources, and although the interpretation of the feminist movement should be clear, in the present, people seem to have a distorted perspective that goes far from its authentic aim (Gassing and Sulartiningsih, 2020).

The theoretical development provided by research on matters of gender studies has also encompassed contemporary issues. Analyzing the intersections of digital culture and gender, Daniels (2009) discusses “cyberfeminism” to understand how new technologies, and specifically the Internet, can be effective for resisting (or reinforcing) repressive gender regimes and enacting equality (Daniels, 2009, p. 101).

The term cyberfeminism was defined by Plant (1997) and is used to “describe the work of feminists interested in theorizing, critiquing, and exploiting the Internet, cyberspace, and new-media technologies in general” (Consalvo, 2002), being associated with the third wave of feminism in the 1990s and 2000s. More recently, Pilcher and Whelehan (2017) revisited the notions surrounding cyberfeminism to expand the discussion toward new questions regarding the relationship between bodies and technology, in addition to how social media functions as communal spaces to counter sexism. Further on, we explore the specific contributions of Instagram to feminism and the context of the movement in Colombia, where the analysis will focus.

Instagram contributions to feminism

Social media are a relevant part of contemporary communication practices and offer research possibilities (Martí et al., 2019). For instance, these platforms enable feminist movements to discuss, organize, and disseminate information, expanding their reach and accessibility through cyberfeminism (Plant, 1994; Consalvo, 2002). Instagram, with over two billion users globally (Kemp, 2023), is a highly influential platform that allows feminists to challenge prevailing narratives. Its interactive features, such as top comments, likes, replies, and video responses, provide opportunities for the dispute of narratives, while also offering the potential to counter misrepresentations and stereotypes found in traditional media (Beni and Veloso, 2022).

Although new media technologies offer opportunities for debates, research highlights concerning aspects of user behavior. Chadha et al. (2020) highlight the prevalence of online harassment and misogynistic behaviors toward women on social media platforms, emphasizing the need for platform interventions (p. 250). Álvarez et al. (2021, p. 469) examine reaction GIFs and raise concerns about the sexualized portrayal of women in these digital visual representations. Prior to Instagram, Herring et al. (2002) studied online trolling in a feminist web-based discussion forum, analyzing disruptive strategies employed by trolls and the challenges faced by targeted groups in responding. The authors suggest that distinguishing between cooperative debate and uncooperative provocation is crucial, with centralized moderation providing support for vulnerable groups experiencing harassment and trolling.

In this context, Instagram provides a platform for feminists to challenge prevailing narratives, despite potential drawbacks of negative online behavior. García and Solana (2019) highlight the role of feminist Instagram artists in changing the thematic agenda by reflecting gender inequality, denouncing sexism, critiquing patriarchy, and educating millennials through art and language. Savolainen et al. (2020) explore how filtering practices shape feminist visibility on Instagram, resulting in a popular image of confident and individualistic feminism while amplifying feminist politics of visibility and desire. Palomo-Domínguez et al. (2022) examine artist Maria Hesse’s content strategy on Instagram, combining her artwork, personal life, and advocacy for feminism and sisterhood. Hesse strategically employs transmediality, hybridization, and feminism to increase her personal brand’s notoriety, aligning with communication trends and user expectations on Instagram.

Another recent paper from these same authors (Palomo-Domínguez et al., 2023) investigates the gender awareness promoted by eight Spanish female illustrators on social media. The study applied three methodological approaches: a desktop study to compare the illustrators’ profiles, content analysis to scrutinize the topics and their advocacy in art, and a Delphi method involving experts in communication, philosophy, sociology, psychology, and politics to assess their contribution to gender egalitarian values. Their findings reveal a strong emphasis on feminism in the illustrators’ publications, fostering a sense of sisterhood, particularly among millennials and centennials. Despite their status as influencers, they exhibit considerable similarity in their communication channels, formats, content, tone, and style, with a significant presence on Instagram.

Furthermore, the platform aims to allow users to shape their experience by providing features to control sensitive content (Instagram, 2021). However, this has led to conflicting perspectives among feminist users, as the platform can simultaneously be supportive and harmful to feminism (Hu, 2017). For instance, feminist demands coexist with publications that reinforce patriarchy and objectify women’s bodies on Instagram (Hu, 2018). Therefore, Instagram presents itself as a “neutral” space, leaving interpretation to its users. In terms of social protests, it also plays a dual role: It offers broad exposure and viral potential for movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, but it enforces community guidelines by removing posts related to natural bodily processes such as menstruation and breastfeeding. In Colombia, feminism on Instagram aligns with global trends, utilizing the platform effectively for social movements. One notable example is the @LasIgualadas page, which will be discussed in the following section.

Feminism and @LasIgualadas: The context in Colombia

Colombian history has limited records on feminism before 1954 when women gained the right to vote. However, oral accounts from ancestors suggest that the indigenous communities that initially inhabited Colombia were matriarchal, emphasizing women’s authority and communal harmony (Watson‐Franke, 1987, p. 234). The arrival of the Spanish in 1492 introduced a stark contrast, as women in Spain held a subordinate status due to religious beliefs reinforced by the Catholic Church (Deagan, 2003, Cushner, 2006). These customs were transplanted to the American continent, perpetuating gender inequality. Therefore, contemporary gender issues, to an extent, come from the reverberations of Spanish colonialism. Even after the country’s independence from Spain to this day there are many social consequences of the unequal division of Colombian society, including huge gaps in social classes, violence, corruption, drug trafficking and armed conflicts.

The first wave of women’s movements in Colombia (1923–1943) fought for voting rights, autonomy, education, and public office, despite political resistance. The 1991 Colombian constitution acknowledged and reinforced women’s rights established in earlier laws (Constitución Política de Colombia, 1991). While progress has been made through international treaties and legislation, challenges remain in full implementation. In February 2022, the feminist movement successfully legalized abortion within the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, following widespread protests (Parkin, 2022). In the past years, activists in the country started using digital social media platforms for information dissemination, alliance-building, and fostering diverse perspectives (Barrachina, 2019). However, digital access gaps and limited connectivity persist in Latin America (World Economic Forum, 2021), making women engaged in feminist cyberactivism a minority. Moreover, empirical studies on cyberfeminism, especially on visual social media platforms, are lacking in Colombia.

Despite the few popular activist accounts, there are Instagram users that talk about the feminist movement and practice activism, one of them being Las Igualadas (@LasIgualadas), an opinion column from the media group El Espectador. The creation of the channel in 2018 is attributed to Mariangela Urbina, the main representant of the column until June 2022, the lawyer Viviana Bohorquez, and Juan Carlos Rincon, opinion editor of El Espectador. The column also has accounts on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok and Instagram. The present research focuses on the latter, which as of May 2023 has around 192,000 followers and is considered one of the most influential and followed feminist accounts in Colombia. Moreover, other applications such as TikTok or YouTube have specific logics of content production/distribution/consumption and how users interact among themselves, which makes it nearly impossible to apply the same methods and procedures to collect and analyze data.

According to their description (Urbina, 2018), the videos that are published in the account bet on a simple and forceful language, which lands the arguments of the gender perspective in the daily life of the audience. Las Igualadas is a channel created to generate a social transformation that encourages women to identify behaviors that are often normalized, but in reality, are violent and speaks about gender issues that seem elementary but that are usually ignored (Fondo Lunaria Mujer, 2022).

Methodology: netnography and critical discourse analysis

The empirical part consisted of a multimodal approach combining exploratory research relying on netnography (Kozinets, 2020), followed by the critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, 2010) of the page content posted on the Instagram account @LasIgualadas and the discussions promoted by users in the comments section. More specific details about the methodology are also presented in the Codebook, which can be accessed via the link at the end of this paper for inspiration, but not as a strict frame, for further research practices of netnography and critical discourse analysis regarding feminism on social media.

The study aims at exploring the research question “how are the discourses about feminism constructed on Instagram in Colombia via @LasIgualadas?”, addressing initial insights from the critical discourse analysis of the page @LasIgualadas.

Netnography, as described by Kozinets (2015), is a qualitative research approach that analyzes online social interaction and the perceptions and behaviors of Internet users over time; thus, being chosen for this study due to the emotionally charged and nonintrusive nature of the content. The study focused on the comments section of Instagram posts as a source of data, which were monitored, coded, and analyzed to understand users’ perceptions of feminist topics and the feminist movement. Challenges encountered during the search included writing and interpretation issues such as spelling errors, contractions, metaphors, irony, and sarcasm. Kozinets (2020) further explains two data collection operations in netnography: investigative and immersive. We applied investigative operations to selectively choose data from the vast amount of information on social media platforms, while immersive operations involved extensive data collection through detailed descriptions recorded in the researchers’ immersion journal, referred to as the Codebook in this research.

When it comes to Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), Fairclough’s approach (2010) suggests that language helps create change and can be used to influence human behavior. The CDA model defines any case of language as a communicative event; the model consists of three categories called dimensions (Setiawan, 2018). These three elements are depicted in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Diagrammatic representation of Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis framework (adapted from Fairclough, 1995, p.98).

Dimension 1 – Text: The analysis focuses on the linguistic features of the text dimensions (Setiawan, 2018). By choosing certain words, one can show an attitude towards the subject.

Dimension 2 – Discursive Practice: The analysis focuses on processes relating to the production and consumption of the text (Setiawan, 2018). The way one talks about a subject can change one’s view of the subject. Text is almost always subject to interpretation.

Dimension 3 – Sociocultural Practice: The analysis focuses on the wider social practice to which the communicative event belongs (Setiawan, 2018). The choice of words forms the context of one’s social community, in which there are certain norms and traditions.

Data collection and procedure

This section of the paper focuses on the data collection of the netnographical approach by presenting and explaining how the data was collected, coded and, later on, how it was critically analyzed. The posts were selected based on the following criteria (see Table 1):

Table 1: Criteria to select the posts for the analysis.

The sample was selected during two phases but analyzed as one dataset. The first phase (20 posts) was collected from the creation of @LasIgualadas account from January 2018 until March 2022. In July 2022, Las Igualadas had a rebranding in all of their channels, in which the main presenters were changed, and the brand image was updated; therefore, the second phase (20 posts) was collected from July 2022 until May 2023. The time frame for the analysis included the oldest top post dated July 05, 2019, and the most recent one dated May 19, 2023.

Table 2: Content classification of posts and the categories.

The Codebook is an outlook that reflects the process of the research and focuses on the methodological aspects of the study. It can be used as a guide to further understand the procedure used by the researchers for the data collection, data description and data analysis. After initial exploratory work to define the most popular posts on the page, the first part of data gathering included a spreadsheet where all the information related to the posts and comments was collected and classified. The content classification of each publication counts with four different categories and each category allows the researchers to classify within the characteristics presented in Table 2:

At the same time, the content classification of each comment counts with four different categories; and each category allows the researchers to classify within the following characteristics in Table 3:

Table 3: Content classification of comments and the categories.

The second part of the research, as explained in the Codebook, focuses on Critical Discourse Analysis. It is important to highlight that the necessary data for developing CDA (posts, comments and graphs) was already collected in the previous steps of the netnography. In this second phase, the researchers critically analyzed the content based on the CDA model following the results from the coded material and the already presented theoretical framework. The analysis was divided into the following four parts: Context; Dimension 1 – Text; Dimension 2 – Discursive Practice; and Dimension 3 – Sociocultural Practice.

Limitations and ethical considerations

The exploratory study has a specific geographical focus, Colombia, directly connected to its sociocultural aspects and the analyzed platform usage (Instagram). Hence, the results cannot be generalized to other countries, regions, or other social media platforms. In addition , the sample is limited by a single page, @LasIgualadas, and by the number of analyzed posts and comments, offering a qualitative analysis. The analyzed page went through a rebranding process and change in its content creators between the first and the second sample, which can imply an alteration in their editorial approach, as indicated in the following section (Data analysis and results). Furthermore, it is not totally clear how the Instagram algorithm favors content visibility, thus attracting more people to debate certain topics. Finally, as an ethical decision, although the content used for this research can be accessed publicly on Instagram, the researchers anonymized the participants whose comments were collected to reduce the risk of identification.

Data analysis and results

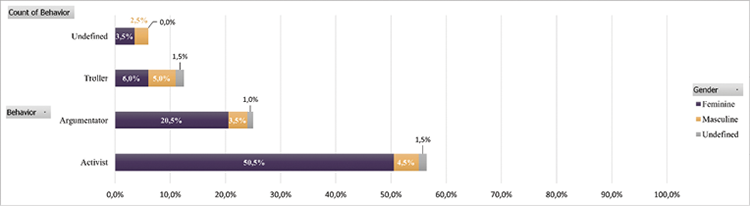

This section focuses on the results after the data was coded, by presenting and explaining some of the graphs generated in the research to provide a context. Additionally, the three dimensions of the CDA are presented to offer a critical perspective on the data analysis. Figure 2 illustrates the Commenter Gender in relation to Commenter Behavior results. Based on the literature collected throughout the explorative part, the feminist movement consists mainly of women; hence 80.5% of the users who interact with the posts are feminine, only 15.5% masculine and 4% undefined. Below the most significant data is highlighted:

Commenter Gender in relation to Commenter Behavior

Figure 2: Instagram comments classification results in the category Commenter Gender in relation to Commenter Behavior.

• 50.5% of the activists were women, which means they support the idea of the post, but since it is a feminist account, the support would be expected to be greater, independently of the gender.

• Of the 15.5% of men who commented, the highest behavior was troller (5%), meaning there is a tendency for men not to take feminism seriously, and by commenting they seek to disrupt with no valid argument, using disrespectful statements or bad words to insult and deliberately provoke others. This behavior of Internet users towards feminists was already noticed at the beginning of the century by Herring et al. (2002) and still persists online.

Alignment of Comments toward Post’s Topic in relation to Topic

In Figure 3, it can be highlighted that:

• A key significant area is agreeableness. The more controversial the topic, the fewer people agree, which can be evidenced in abortion issues, where 9% out of 12.5% of the people disagree with abortion-related issues.

• Regarding the topic of violence, people tend to agree more (23.5%); a reason for this could be that people tend to feel compassion for the cases shown in posts that talk about everyday life painful experiences and some people may feel identified or feel greater empathy.

Figure 3: Post classification and Comment classification results in the category Alignment of Comments towards Post’s Topic in relation to Topic.

The data shows a slight tendency in variation regarding the categories over time, with changes in the coverage of topics such as violence and abortion. However, this trend cannot be evaluated as conclusive due to two primary factors. Firstly, the rebranding and change in content creators that occurred between the first and second sample collections. This transition potentially implies that the rebranded identity of Las Igualadas has brought forth new strategies and plans for the Instagram account. These orientations, encompassing diverse thematic areas and consumer approaches, are still undergoing refinement and may differ from the approaches employed by the previous content creators. Secondly, as the page also covers sporadic events to foment public debate, this tendency could have been influenced by other social factors (i.e., a lawsuit from 2020 that resulted in Colombia’s constitutional court voting in early 2022 to decriminalize abortion until 24 weeks of gestation).

Throughout the data analysis, it is possible to notice that a significant amount of Las Igualadas Instagram followers are either explicitly feminists or users interested in acquiring more knowledge on feminist topics. For instance, less than half of the comments contest the feminist agenda (Activist 57% vs. Argumentator 25%; Agreeableness 52.5% vs. Disagreeableness 32%), which could be expected considering Las Igualadas’ declaration as an account dedicated to feminist discourse. Consequently, this phenomenon might lead to an echo chamber effect, where critical evaluation is diminished and conveys the impression of unanimous agreement on feminist issues. Nevertheless, there are still contradictory positions from users, that even though might be fewer in numbers, their willingness to voice contrary perspectives fosters the debates while challenging prevailing assumptions and creating a more diverse understanding of feminist issues.

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)

The strongly shaped culture in Colombia is a vehicle that allows knowing the country’s idiosyncrasies within its great cultural diversity. Colombia is divided into thirty-two regions, having infinite spaces where traditions, experiences, political-economic situations, and backgrounds converge. For years, these have built an imaginary about what the country’s inhabitants are. Despite the regional differences, there is a point where it all collides; the Spanish colonialism left a lasting influence throughout the country. Although the Spanish decimated the indigenous population, many elements live on in Colombian customs, music, and rituals. Moreover, even though, in the eyes of the world, Colombia is a country full of beauty, nature, dances, traditions and charm, this is just a layer on top of all the consequences of colonialism that still live in the political, economic, and social problems of the country (Cosoy, 2016).

As discussed in the theoretical framework, the Roman Catholic religion and the Spanish language marked the beginning of a machista2 culture based on gender inequalities. Such culture takes away women’s power of choice, inhibits access to equal opportunities and stigmatizes them to fit into gender roles. Likewise, even after the country’s independence in 1819, the slavery of both native Indigenous and Africans had consequences in the unequal division of social classes; consequences that have fostered violence, corruption, drug trafficking and armed conflicts in the actuality.

Dimension 1

In the first dimension, the feminist message is taken as text: what Las Igualadas conveys in their posts and the comments responding to its publications. As feminism is still considered a controversial issue in Colombia, some commenters tend to use sarcasm, irony, passive-aggressive comments and even jokes, as it is evidenced in Comment 1 of a post related to Transgender people. When the argument heats up, they begin to directly insult the Commenter they are arguing with, by attacking their personal life and treating them as ignorant on the topic like in Comment 2.

Comment 1 and Comment 2. Retrieved from the account @LasIgualadas on Instagram.

Dimension 2

The second dimension focuses on the commenter’s words, and how they compose the sentences is essential to understanding the perspective on feminist issues. The CDA model states that the way people talk about a subject can change one’s point of view. An example of this is Figure 4 where the image’s description says: “Chris Pratt’s last post on Instagram is the representation of everything that is wrong with some men.” From the outset, the semantic way in which the sentence is formed already gives it a negative connotation toward men; consequently, the discussions in the comments are carried out negatively, especially in relation to men.

Figure 4. Post from @LasIgualadas account.

Dimension 3

The third dimension talks about what is considered good or bad, normal or strange, based on the context of a specific society, in this case, Colombia. The moment a person does not approve of the text, it is difficult for that person to agree with that posture. Many people in Colombia do not consider themselves feminists because how the discourse is transmitted no longer identifies them, even though they agree with the essence of feminism.

At the same time, Colombians are characterized by their loyalty to their traditions and norms. As mentioned above, economic, social, and cultural problems have cultivated mistrust and intolerance of foreign ideas among Colombians. Consequently, there is still a barrier that does not allow Colombian society to fully accept new or revolutionary positions such as feminism.

Discussion

Social media is an incredibly powerful tool if used correctly, hence the importance of knowing how to take advantage of it when wanting to convey a message in a particular way. Considering the different studies mentioned throughout the paper, as well as the historical overviews of feminism, and its relationship with social media, it is possible to understand feminism as a representative movement in which fights are fought from different realities. At the same time, Instagram is a platform that has the potential for the feminist movement to raise voices for all those realities that traditional media do not cover entirely.

Reflecting on the initial research question – how are the discourses about feminism constructed on Instagram in Colombia via @LasIgualadas? – throughout the data analysis and results, it was possible to see how the discussions in the comments were carried out. Comment discussions are relevant for Instagram accounts because it increases the visibility of the content. Moreover, Instagram allows scope for contradicting voices to express their opinions, but it still lacks further technical development to properly detect and prevent the dissemination of hate speech or misleading information about feminism, corroborating the claims made by Chadha et al. (2020). This can be evidenced by “trolls” or accounts without a clear user identification disseminating messages that intentionally tried to deviate or harm a healthy debate online.

In the case of Las Igualadas, by touching on feminist issues from different perspectives and realities, their account makes Instagram users in Colombia think and question their own posture on issues that are not constantly discussed in more traditional media platforms. Although it was evidenced that some discussions tried to dispute the user’s attention and deviate from the main topics of discussions while diminishing the feminist agenda, in some cases by adopting conservative perspectives that are rooted in specific traditional values (i.e., using religious beliefs to advocate against abortion), the study indicates that users’ counter-argumentations to these attention-deviating or provocative comments could balance the debate and preserve the main narratives. Moreover, to one extent, the prevalence of an audience that supports the page’s ideas (namely, their followers) favors the development of progressist discussions in comparison to the least common deviating/disagreeing Instagram users who take part in the debates.

Even though Instagram’s functionalities still have room for improvement to prevent censorship of some content related to women’s matters, while also enabling a healthier/cleaner debate – for instance, preventing aggressive comments from trolls or the development of extremist ideas (i.e., racist, misogynist, xenophobic, etc.) – Instagram could be adopted by the feminist movement and by other social causes to challenge/break stereotypes and inform society directly. Further research could expand this analysis to other pages, platforms, and countries, and increase the number of posts/comments to also explore the topic from a more quantitative perspective.

Resources

Codebook: The codebook applied for the data analysis in this research can be accessed via the link: https://bit.ly/CodebookInstafeminismInColombia

References

Álvarez, D., González, A., & Ubani, C. (2021). The Portrayal of Men and Women in Digital Communication: Content Analysis of Gender Roles and Gender Display in Reaction GIFs. International Journal of Communication, 15, 462–492. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/14907

Barrachina, S. G. (2019). ¿En que contribuye el feminismo producido en las redes sociales a la agenda feminista? Dossiers feministes, 25, 147–167. http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/Dossiers.2019.25.1

Beni, A., & Veloso, A. S. (2022). Debating Digital Discourse: The Impact of User-Generated Content on the Visual Representation of #Africa. In A. Mammadov & B. Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk (Eds.), Analysing Media Discourse: Traditional and New (pp. 179–204). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Butler, J. (1986). Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex. Yale French Studies, 72, 35–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2930225

Castells, C. (1996). Perspectivas feministas en teoría política. Paidos.

Chadha, K., Steiner, L., Vitak, J., & Ashktorab, Z. (2020). Women’s Responses to Online Harassment. International Journal of Communication, 14, 239–257. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/11683

Collins, R., Chafetz, J. S., Blumberg, R. L., Coltrane, S., & Turner, J. H. (1993). Toward an Integrated Theory of Gender Stratification. Sociological Perspectives, 36(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.2307/1389242

Consalvo, M. (2002). Cyberfeminism. In S. Jones (Ed.), Encyclopedia of New Media (pp. 109–110). SAGE Publications.

Constitucion Politica de Colombia. (1991). Constitucion Política 1 de 1991. https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=4125

Cosoy, N. (2016, August 24). ¿Por qué empezó y qué pasó en la guerra de más de 50 años que desangró a Colombia? BBC News Mundo. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-37181413

Crossley, A. D. (2015). Facebook Feminism: Social Media, Blogs, and New Technologies of Contemporary U.S. Feminism. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 20(2), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671X-20-2-253

Cushner, N. P. (2006). Why Have You Come Here? The Jesuits and the First Evangelization of Native America. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195307569.001.0001

Daniels, J. (2009). Rethinking Cyberfeminism(s): Race, Gender, and Embodiment. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 37(1/2), 101–124. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27655141

Deagan, K. (2003). Colonial origins and colonial transformations in Spanish America. Historical Archaeology, 37(4), 3–13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25617091

Díaz, J. (2022). Lo que hemos logrado “Rayando Paredes”. Aire libre. https://airelibre.fm/lo-que-hemos-logrado-rayando-paredes/

Drees-Gross, F., & Zhang, P. (2021, July 21). Less than 50% of Latin America has fixed broadband. Here are 3 ways to boost the region’s digital access. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/07/latin-america-caribbean-digital-access/#:~:text=While%2087%25%20of%20the%20population,the%20population%20in%20urban%20areas.&text=Data%20plans%20and%20internet%2Denabled,affordable%20for%20the%20region

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Longman.

Fairclough, N. (2010). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ferguson, K. E. (2012). Simone de Beauvoir – Introduction. Theory & Event, 15(2). https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/478358

Fondo Lunaria Mujer. (2022). Las Igualadas, Bogotá. https://fondolunaria.org/las-igualadas-bogota-2/

Gassing, S. S., & Sulartiningsih, S. (2020). Reality Construction of Feminism Distortion in Cyber Media. International Journal of Science and Research, 9(9), 82–87. doi:10.21275/SR20831140509

García, M. T. M., & Solana, M. Y. M. (2019). Mujeres ilustradoras en Instagram: las influencers digitales más comprometidas con la igualdad de género en las redes sociales. VISUAL REVIEW. International Visual Culture Review / Revista Internacional de Cultura Visual, 6(2), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.37467/gka-revvisual.v6.1889

Herring, S., Job-Sluder, K., Scheckler, R., & Barab, S. (2002). Searching for safety online: Managing “Trolling” in a feminist forum. The Information Society, 18(5), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240290108186

Hu, N. (2017, June 22). What Instagram Taught Me About Feminism. The Harvard Crimson. https://www.thecrimson.com/column/femme-fatale/article/2017/6/22/hu-instagram-feminism/

Hu, Y. (2018). Exploration of How Female Body Image Is Presented and Interpreted on Instagram. Advances in Journalism and Communication, 6(4), 95–120. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2018.64009

Huber, J. (2016). On the Origins of Gender Inequality (1st ed.). Routledge.

Instagram. (2021, July 20). Introducing Sensitive Content Control. https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/introducing-sensitive-content-control

Kemp, S. (2023, January 26). Digital 2023 - We Are Social Report. https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2023/01/the-changing-world-of-digital-in-2023/

Kozinets, R. V. (2015). Management Netnography: Axiological and Methodological Developments in Online Cultural Business Research. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods. SAGE.

Kozinets, R. V. (2020). Netnography: the essential guide to qualitative social media research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Kruks, S. (1992). Gender and Subjectivity: Simone de Beauvoir and Contemporary Feminism. Signs, 18(1), 89–110. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174728

Mahoney, C. (2020). Is this what a feminist looks like? Curating the feminist self in the neoliberal visual economy of Instagram. Feminist Media Studies, 0(0), 1–17.

Martí, P., Serrano-Estrada, L., & Nolasco-Cirugeda, A. (2019). Social Media data: Challenges, opportunities and limitations in urban studies. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 74, 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2018.11.001

Mclaughlin, L. (1993). Feminism, the public sphere, media and democracy. Media, Culture & Society, 15(4), 599–620. https://doi.org/10.1177/016344393015004005

Mealey, L. (2000). Sex differences: Development and Evolutionary Strategies (1st ed.). Academic Press.

Palomo-Domínguez, I., Sánchez-Gey Valenzuela, N., & Jiménez-Marín, G. (2022). Hibridación, transmedialidad y feminismo en la comunicación social de María Hesse: marca persona y perfil en Instagram. In M. P. Álvarez-Chávez, G. O. Rodríguez-Garay, & S. Husted Ramos (Eds.), Comunicación y pluralidad en un contexto divergente (pp. 544–572). Dykinson.

Palomo-Domínguez, I., Jiménez-Marín, G., & Sánchez-Gey Valenzuela, N. (2023). Social Media Strategies for Gender Artivism: A Generation of Feminist Spanish Women Illustrator Influencers. Information & Media, 98, 23–52. https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2023.98.61

Parkin, D. J. (2022, February 22). Colombia legalises abortion in move celebrated as ‘historic victory’ by campaigners. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/feb/22/colombia-legalises-abortion-in-move-celebrated-as-historic-victory-by-campaigners

Percy, C., & Kremer, J. (1995). Feminist Identifications in a Troubled Society. Feminism & Psychology, 5(2), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353595052007

Pilcher, J., & Whelehan, I. (2004). Fifty key concepts in gender studies. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446278901

Pilcher, J., & Whelehan, I. (2017). Cyberfeminism. In Key concepts in gender studies (pp. 25–27). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781473920224.n8

Plant, S. (1997). Zeros + Ones: Digital Women + the New Technoculture. Fourth Estate.

RAE. (2022). Machismo — Definición. In Diccionario de la lengua española. https://dle.rae.es/machismo

Restuccia, F. L. (1987). The Name of the Lily: Edith Wharton’s Feminism(s). Contemporary Literature, 28(2), 223–238. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1208389?origin=crossref

Savolainen, L., Uitermark, J., & Boy, J. D. (2022). Filtering feminisms: Emergent feminist visibilities on Instagram. New Media and Society, 24(3), 557–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820960074

Setiawan, H. (2018). Deconstructing Concealed Gayness Text in The Film Negeri van Oranje: Critical Discourse Analysis. Jurnal Humaniora, 30(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.22146/jh.26991

Highfield, T., & Leaver, T. (2016). Instagrammatics and digital methods: studying visual social media, from selfies and GIFs to memes and emoji. Communication Research and Practice, 2(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2016.1155332

Thompson, D. (1994). Defining Feminism. Australian Feminist Studies, 9(20), 171–192.

Urbina, M. (2018, March 7). Conozca a las santandereanas creadoras de ’Las Igualadas’. Vanguardia. https://www.vanguardia.com/entretenimiento/galeria/conozca-a-las-santandereanas-creadoras-de-las-igualadas-PDVL426669

Watson‐Franke, M. B. (1987). Women and property in Guajiro society. Ethnos, 52(1-2), 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.1987.9981343

Willemsen, T. (1997). Feminism and utopias: An introduction. In A. van Leening, M. Bekkerl, & I. Vanwesenbeeck (Eds.), Feminist utopias in a Postmodern Era (pp. 1–10). Tilburg University Press.

Winter, B. (2010). Feminism, Economics and Utopia: Time Travelling through Paradigms. Feminist Economics, 16(2), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701003731872