Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2025, vol. 102, pp. 142–162 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2025.102.8

Knowledge Creation in Life Sciences Scientific Research Teams: A Qualitative Study of Principal Investigators in Lithuania

Simona Taparauskienė

Vilnius University, Communication Faculty

salciunaite.simona@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-0216-180X

https://ror.org/03nadee84

Saulė Jokūbauskienė

Vilnius University, Communication Faculty

saule.jokubauskiene@kf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1218-5105

https://ror.org/03nadee84

Abstract. Knowledge creation in research teams is a continuous process. Scientists representing different fields collaborate in interdisciplinary teams, as combining knowledge from various fields enables them to solve complex scientific problems. Europe’s digital decade, the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Regulation 2024/1689, is expected to shape the global labor market by 2030, driven by the interplay of geoeconomic fragmentation, knowledge-economy uncertainty, and sustainability. It is essential to emphasize that breakthrough technology at a national level can be developed by small groups of scientists. Information and communication technologies are crucial for ensuring the storage and transfer of data, information, and knowledge, both within teams and between teams. The study employs a semi-structured qualitative interview method to examine the knowledge-creation process in scientific research teams in the life sciences. Based on a literature review and qualitative research, the study finds that the knowledge-creation process in those teams aligns with the knowledge conversion model. The methods used for knowledge creation include conducting experiments, taking laboratory notes, reflecting, engaging in scientific discussions, patenting, reading and writing scientific articles, and searching for information in databases. The cultivation of organizational culture and the use of information and communication technology tools are two criteria that support an effective knowledge-creation process.

Keywords: knowledge creation, scientific research teams, information and communication technologies.

Žinių kūrimas gyvybės mokslų srities mokslinių tyrimų komandose: kokybinis pagrindinių tyrėjų tyrimas Lietuvoje

Santrauka. Žinių kūrimas mokslinių tyrimų komandose yra nepertraukiamas procesas – naujos žinios nuolat kuriamos remiantis ankstesnių tyrimų rezultatais. Įvairių sričių mokslininkai yra linkę dirbti tarpdisciplininėse mokslinių tyrimų komandose, nes įvairių sričių žinių sujungimas įgalina išspręsti sudėtingus mokslinius klausimus. Technologijų plėtra, Europos skaitmeninis dešimtmetis atitinka geoekonominės fragmentacijos, žinių ekonomikos neapibrėžtumo ir tvarumo vaidmenį, kurie kartu yra vieni iš pagrindinių veiksnių, transformuojantys pasaulinę darbo rinką iki 2030 m. Svarbu pabrėžti, kad nacionaliniu lygmeniu proveržio technologijas gali kurti nedidelės mokslininkų grupės. Plačiąja prasme informacijos ir ryšių technologijos yra labai svarbios užtikrinant veiksmingą duomenų, informacijos ir žinių saugojimą ir perdavimą tiek komandos, tiek komandų tarpusavio lygmeniu. Straipsnyje pristatomas tyrimas, kuriame naudojant pusiau struktūruotą kokybinio interviu metodą nagrinėjamas žinių kūrimo procesas gyvybės mokslų srities mokslinių tyrimų komandose. Remiantis literatūros analize ir kokybiniu tyrimu, atliktu pasitelkiant pagrindinius tyrėjus Lietuvoje, galima teigti, kad žinių kūrimo procesas mokslinių tyrimų komandose atitinka žinių konversijos modelį. Žinių kūrimui naudojami metodai apima eksperimentų atlikimą, laboratorinių užrašų pildymą, refleksiją, mokslines diskusijas, patentavimą, mokslinių straipsnių skaitymą ir rašymą bei informacijos paiešką duomenų bazėse. Organizacinės kultūros puoselėjimas, informacijos ir ryšių technologijų priemonių naudojimas yra du kriterijai, užtikrinantys veiksmingą žinių kūrimo procesą.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: žinių kūrimas; mokslinių tyrimų komandos; pagrindinis tyrėjas; gyvybės mokslai; informacinės ir ryšių technologijos

Received: 2025-12-30. Accepted: 2025-07-16.

Copyright © 2025 Simona Taparauskienė, Saulė Jokūbauskienė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Research and development (R&D) at the national scale fosters structural change to build a more knowledge-intensive economy and society, enhances international competitiveness, promotes growth in labor productivity, and creates high-quality jobs. More than 52 million euros were allocated for R&D projects in Lithuania in 2024, coming from the state budget and the European Union’s structural support funds (Research Council of Lithuania, 2024). The integration of knowledge from different disciplines becomes a core process in scientific problem solving for addressing complex scientific and societal issues (Cooke et al., 2015; Misra et al., 2011; Salazar et al., 2012). The number of co-authors of scientific articles is increasing, and scientific research teams are becoming more international and multidisciplinary (Choi & Pak, 2006; Jones, 2021; Stokols et al., 2008). Advancements in digital technology accelerate data retrieval, facilitate information and knowledge management processes, and increase the efficiency of collaboration among geographically dispersed teams or team members, all of which are integral to knowledge creation in teams.

The research studies of knowledge management include knowledge creation, storage, and sharing processes analyzed as an impact for innovations (Atkočiūnienė & Petronytė, 2018; Hansen, 2002), researchers explore the nature of knowledge and its creation process (Alavi & Leidner, 2001, Nonaka et al., 2000, Nonaka & Toyama, 2003). Previous studies have explored an increasing teaming-up (Jones, 2021), the structure of scientific research teams (Choi & Pak, 2006; Stokols et al., 2008), their organizational culture (Antes et al., 2016; Cooke et al., 2015; Prado-Gasco et al., 2015), and leadership (Casati & Genet, 2014). Some researchers, such as Bailey et al. (2012) and Griffith et al. (2003), explored studies on the benefits of information and communication technologies (ICT) for organizing work in teams. Although there is a gap in the literature on scientific research teams dedicated to life sciences research, there is a focus on the knowledge creation process. The research question is as follows: How is the knowledge creation process in Life Sciences scientific research teams in Lithuania constructed from the principal investigator’s perspective?

Research object. Knowledge creation in scientific research teams of Life Sciences scientific research teams in Lithuania from the principal investigator’s perspective. The research aim is to explore knowledge creation of life sciences scientific research teams in Lithuania from the principal investigator’s perspective. In alignment with the aim, the research tasks are as follows: 1) to analyze knowledge creation of Life Sciences scientific research teams in Lithuania from the principal investigator’s perspective, and 2) to explore the findings of knowledge creation of a qualitative study of principal investigators in Lithuania in Life Sciences scientific research teams.

The study aims to extend knowledge management research by incorporating scientific research teams into the previous models, on the grounds of examining an effective knowledge creation process: fostering an appropriate organizational culture, and leveraging information and communication technology tools. In this context, the following research methods were used: qualitative case study, including scientific literature analysis, and semi-structured qualitative interview.

The Knowledge Creation Process

The Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom (DIKW) hierarchy is constructed along three axes – first, understanding from exploration to reflection, second, the context from collecting the details to integrating the picture, and third, the time between the past and the future (Hey, 2004) (see Figure 1. DIKW hierarchy (Hey, 2004)). The data are obtained by researching and collecting separate details of the context, and information is gathered by combining the details and assimilating them, although the interpretation of the same data varies significantly based on an individual (Jashapara, 2004, p. 17). Knowledge is acquired through experience in the past, and the highest level of the hierarchy is wisdom, which is created by building on contributions to new ideas and reflecting a knowledge-based ecosystem (Burns, 2025, p. 48).

![[There are three axes in the image: the vertical axis representing the context is graded into four steps – gathering parts, connection of parts, formation of a whole, and joining the wholes; the horizontal axis, which denotes understanding, is graded into five steps – researching, absorbing, doing, interacting, and reflecting; the third axis is diagonal and represents time scale. To the side of this axis, there are four bubbles representing the DIKW hierarchy. The time axis is divided into the Past (Experience) and the Future (Novelty) at the place where the knowledge and wisdom boundaries intersect – exactly where scientific research teams work.]](https://www.journals.vu.lt/IM/en/article/download/42817/version/38959/41575/131002/figg-1.png)

Figure 1. DIKW hierarchy (Hey, 2004)

R&D activities explore new knowledge to solve challenges and problems, or use already existing knowledge to acquire additional expertise for the development of new ideas, products, or services. Researchers, based on their work, continuously create knowledge by identifying research gaps, considering their experience of conducting research, and interpreting the data obtained. The process involves everyone in scientific research teams and especially principal investigators, who not only carry out the research, but also set the vision and strategy of the team’s projects and develop new ideas for research.

Organizational learning is a process of achieving traditional goals through the acquisition of knowledge (know-what) and the development of skills (know-how), as well as a change in attitudes of the individual learner (Jashapara, 2004, p. 61) that occurs in the learning process for each team member. Developing new areas of research team learning can be viewed in a group’s capacity to engage appropriately in dialogue and discussion (Harris, 1990; Jashapara, 2004, p. 62; Senge, 1990). The construction of single-loop and double-loop learning explores objectivist perspectives on the knowledge creation process in scientific research teams, confirming positivist-rooted ideas that the social world can be studied scientifically, with the main idea that objective knowledge is produced through research (Hislop, 2013, p. 18). Whereas, the concept of activity theory developed by Engeström’s expanded Activity theory model (Hashim & Jones, 2007) is a theoretical framework for understanding human interaction through the use of tools and artefacts. The tools in Life Science scientific research teams serve as information and communication technologies, and artefacts may be found as experiment notes, which also means conducting the experiments. The study adopts Nonaka’s SECI model, which has been argued to encompass the core knowledge-creation process, including the understanding of Ba/Space (Hislop, 2013, p. 106–111), as observed in scientific research teams, and continues the classical knowledge management tradition.

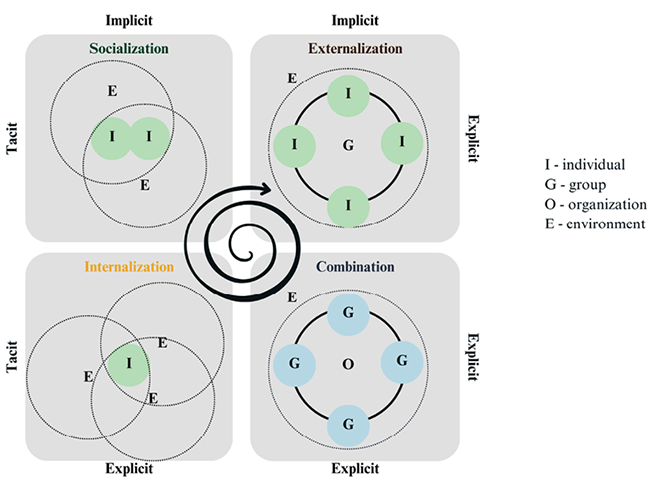

Knowledge is divided into three types: a) explicit, b) implicit, which can be easily conveyed, and c) tacit, which is acquired personally through experience and is difficult to express (Nickols, 2010). One form of knowledge can be converted into another, i.e., tacit knowledge can be transformed into explicit knowledge and vice versa (see Figure 2). Information collected inside and outside the organization is usually stored as personal experience, and the first step for transforming employees’ tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge, according to Nonaka & Toyama (2003), is socialization based on the conversion of knowledge between forms that knowledge is created (Hislop, 2013, p. 108). The process is based on sharing experiences face-to-face, whereas knowledge is conveyed by working together, observing, and memorizing important knowledge. Communication methods depend largely on the type of organization and the nature of its activities; they vary from discussion and reflection on completed tasks, whereas, overcoming of challenges leads to acquired experiences, when, on the grounds of the previous experience, employees of the organization combine their knowledge and know-how, know-why, and care-why. This process, when tacit knowledge in people’s minds is prepared for expression, i.e., when it is transformed into implicit knowledge, and also expressed and written down, is called externalization (Atkočiūnienė & Petronytė, 2018; Faith & Seeam, 2018; Nonaka & Toyama, 2003). Meanwhile, combination refers to the process by which accumulated knowledge is expressed in a new, physical form. The final step in the knowledge conversion model is internalization, with the focus shifting to the personal domain (Leibold et al., 2002). At this stage, new concepts or models apply in practice. It is of importance to note that members of the organization work with explicit knowledge and encounter new, unique situations. In relation to the challenges, new experience is acquired – this is tacit knowledge, which must be formalized again, starting from the first step. In the model presented by Nonaka & Toyama (2003), the spiral symbol, rather than a circle, appears, indicating that new knowledge is created from existing knowledge. Thus, in an organization, knowledge is created through the interaction of explicit and tacit knowledge, and is expanded both qualitatively and quantitatively, thereby creating added value for the organization (Atkočiūnienė & Petronytė, 2018; Nonaka et al., 2000).

Figure 2. Knowledge conversion (SECI) model (Nonaka & Toyama, 2003)

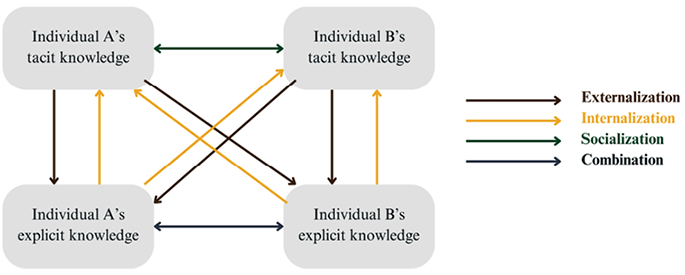

The SECI process of knowledge creation occurs both within a team and between two individuals. According to the model presented by Alavi & Leidner (2001), the tacit knowledge of one individual, during externalization, can be transformed into the explicit knowledge of that individual and another individual, or, during socialization, into the tacit knowledge of another person (Figure 3). During internalization, an individual’s explicit knowledge may become the tacit knowledge of another individual, and, in the case of combination, this knowledge may become that individual’s explicit knowledge.

Figure 3. Knowledge conversion between two individuals (Alavi & Leidner, 2001)

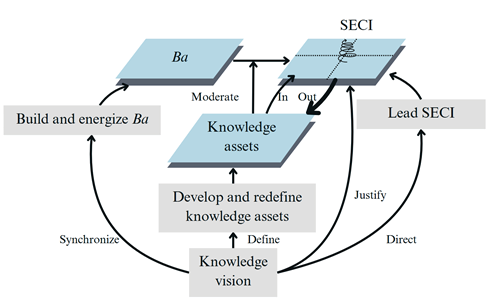

Three components are required for organizational knowledge creation: the SECI process, Ba and knowledge assets (Nonaka et al., 2000). Ba is described as a common place, or space for knowledge creation, and it has four types that are distinguished – initiating, interacting, cybernetic, and practitioner. The meaning of the space correlates with the stages of the SECI process. Knowledge assets are the basis of knowledge creation processes, and they are also organization-specific resources, which are one of the most important assets of the organization to create a sustainable competitive advantage (Senge, 1990). Four types of knowledge assets are distinguished: experiential, conceptual, systemic, and routine knowledge assets (Nonaka et al., 2000). In the knowledge creation process, managers play a particularly important role, mainly middle managers, who are at the intersection of vertical and horizontal information flows within large organizations (Hislop, 2013). Fundamentally, knowledge vision is important, which refers to the direction that the organization needs in its pursuit to acquire knowledge. The definition of a vision that affects all three layers of the knowledge creation process, based on the current situation, is carried out by top and middle management working with all three elements of the knowledge creation process – i.e., leaders present a vision of knowledge, develop and promote the sharing of knowledge assets within the organization, and create and energize, enable and encourage continuous knowledge conversion in Ba (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Knowledge creation process (Nonaka et al., 2000)

Scientific research teams share and carry on several projects, or vice versa, several teams work on one project, which demonstrates the importance of the knowledge network. Hansen (2002) explored knowledge sharing between project teams, and the teams connected to those with the necessary knowledge were more successful in completing their projects more quickly. Finally, the research results also showed that direct connections can be damaging if the shared knowledge is not appropriately selected for maintenance.

Scientific Research Teams

A scientific research team is a team of contributing researchers led by (a) principal investigator(s) to produce scientific results, primarily in the form of scientific papers, patents, or innovations (Milojević, 2014). While it is noticeable that, in the second half of the 20th century, the number of scientists joining teams was increasing, while also the number of co-authored articles was growing, for example, in the field of economics, articles with two or more authors in 1960 accounted for only 19% of articles in economic journals, whereas, in 2000, this share increased to 44%, and, in 2018, it went up to 74%; despite creating university research groups, there is a lack of high-level, long-term, top-down, interdisciplinary and interdepartmental teams (He et al., 2024; Jones, 2021).

Scientific research teams can be very diverse in their composition and in their attempts of reaching different goals depending on the competences of the team members – undiscipline, multidiscipline, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary (Stokols et al., 2008). The primary rationale for bringing researchers together into scientific research teams is the challenge posed by complex scientific and societal issues that require integrating a broad mix of disciplines and, in some cases, stakeholder perspectives. If team members apply their unique knowledge and skills to address a common research problem, knowledge integration becomes a key process in solving scientific problems (Cooke et al., 2015; Misra et al., 2011; Salazar et al., 2012). However, the issue of integration of team members themselves creates challenges, as people from not only different disciplines but also different countries and cultures, speaking different languages and having different research practices, come together to work in scientific research teams. Scientists may come to discomfort by crossing the boundaries of their disciplines – both by the physical boundaries of their discipline department, laboratory, or research center, and the cultural boundaries that guide their scientific activities. According to Cooke et al. (2015), the challenges of integrating scientists into interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teams can be addressed through an appropriate organizational culture and stimulative system. Organizational culture leads to the effectiveness of knowledge management. A study by Prado-Gasco et al. (2015) shows that the level of knowledge management in R&D teams is high when a constructive organizational culture that fosters communication, collaboration and support is established, which creates favorable conditions for knowledge management. The findings of the study also indicate that, in R&D teams, organizational culture has a greater impact on knowledge management than knowledge management has on organizational culture.

Following the number of publications focused on the quantification of researchers and to note that mixed-motive situations often takes place in scientific research teams, it is evident that being an author of an article is of primary importance, therefore, considering that researchers compete at both the individual and team levels, i.e., as a team, they collectively attempt to get their research published in the possibly highest-ranked journal, while, at the same time, each individual researcher wants to be the first author of a publication (Klaic et al., 2018; Milojević, 2014). According to the management of scientific research teams, there remains a particularly complex process, whereas, in contrast, the quality and integrity of a scientific work largely depend on the management and leadership practices of the principal investigator. The complexity of activities such as supporting organizational culture, implementing knowledge management systems, mentoring trainees, collecting teams, training and supervising staff, solving technical problems, and improving work processes are an integral part of good research results (Antes et al., 2016; Casati & Genet, 2014).

However, principal investigators engage in dialogue with the academic scientific community, business companies, and other participants in the knowledge economy ecosystem while conducting research. The principal investigator must consider medium- and long-term scientific visions and perspectives of research projects alongside scientific trends, national and international priorities, and the requirements of public authorities (Casati & Genet, 2014; Greco et al., 2022). In conclusion, while scientific research teams demonstrate the importance of the knowledge network, previous research highlights issues on knowledge creation processes linked to the SECI model as developed by Nonaka & Toyama (2003) and the supported organizational culture.

Research Methodology

This section examines knowledge creation as a continuous process within scientific research teams, culminating in innovation. According to the Resolution of the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania of April 11, 2024 No. XIV-2538, the smart specialization strategy (S3) must be explicitly directed at the continuous creation of social creativity, social development visions and goals, and social innovations, in the context of digitalization and the development and implementation of green technologies. Currently, only three areas in the country meet the criteria for science and business that create knowledge and innovations and have scientific experience, two of which are life sciences and information and communication technologies (Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania, 2024). The statement supports the reliability of the study’s results.

A qualitative case study of principal investigators in life science scientific research teams applying to a semi-structured qualitative interview method was designed on the perception that this methodological approach would support the ability to respond in real time of the interview and to incorporate supplementary inquiries into the prepared questionnaire that were appropriate to the subject for consideration while seeking to sustain a neutral and conversational atmosphere between the informant and the interviewer (Gaižauskaitė & Valavičienė, 2016; Tidikis, 2003).

The questionnaire addressed team organization and organizational culture. The research sample was formed by using purposeful sampling combined with snowball sampling, with each principal investigator, wherever possible, recommending a colleague. However, the study informants had to meet the following criteria: 1) being the principal investigator leading the scientific research team; 2) representing the life sciences research field. Thirty-one invitations were sent by email to principal investigators of Organization X in the life sciences field to participate in the study. A total of 11 principal investigators were interviewed. The scientific research teams’ management experience among the interviewed principal investigators was as follows: four of them had 25–30 years, three had 15–20 years, two had 20–25 years, one had 10–15 years, and one had more than 40 years of experience. The size of the scientific research teams differs: three teams consist of fewer than five members, one team consists of 15–20 members, and six teams consist of 5–10 members. Further, the transcription of all recordings was conducted by using artificial intelligence-based transcription tools TurboScribe and MAXQDA (2024). The data were analyzed by using qualitative content analysis, which involved dividing the informants’ statements into categories and subcategories. To protect the anonymity of the principal investigators in Organization X, where the scientific research teams are highly distinctive and even minor details could reveal their identities, we avoided using indexed quotation labels that might enable readers to identify the participants. We also analyzed Organization X’s strategic activity plans to enrich the research results. Finally, the study was conducted according to the principles of research ethics that include anonymity, information about usage of the results, voluntary participation, and the ability to withdraw from participation in the interview. The study was conducted in November–December 2024.

Analysis of Research Results

During the analysis of knowledge creation and preservation methods, it was established that knowledge is created and preserved by several different methods – by conducting experiments and filling in laboratory notes, team and personal meetings, scientific discussions and writing scientific publications, reflection on the conducted research, challenges encountered, and feedback (Table 1). The most important of them are:

a) conducting experiments and filling in laboratory notes – laboratory notes, or workbooks, recording the conditions and results of all experiments conducted. Since new knowledge builds on old knowledge, it is sometimes relevant to know the exact conditions of an experiment conducted several years ago, and only in well-kept laboratory notebooks can the necessary information be found. It is this need to trace back to information obtained in the past that justifies why the keeping of laboratory notebooks should be a commitment of every researcher to the laboratory. These notes are mostly paper-based, but digital platforms are also used, such as Benchling, a cloud-based platform for storing and sharing scientific data in biotechnology.

b) reviewing and writing scientific publications. Scientific publications document the knowledge gained from research on the subject. However, to conduct research and correctly interpret the results, the informant believes that it is necessary to read scientific publications first and foremost. Equally important is the scientific discussion with the team members about the scientific publications they have read, which helps generate new ideas.

It can be noted that different types of meetings – personal one-to-one or team meetings – are organized in different scientific research teams, and the frequency varies as well – this may be monthly, weekly or bi-monthly, and one of the teams does not organize regular meetings at all. Despite the differences in the organization of the meetings, they discuss largely the same topics – that is, scientific news in the field being studied, the results of scientific research and the challenges faced, and everyday issues in the laboratory.

Table 1. Methods for knowledge creation and preservation that are used by scientific research teams

|

Category: Knowledge creation and preservation methods |

|

|---|---|

|

Subcategory |

Illustration of proposition |

|

Experiments & laboratory notes |

‘It is a legal obligation for every scientist to keep a laboratory journal’ ‘Sometimes you have to pull out a journal that is ten years old’ ‘It is very important to document every experiment that succeeds or fails. <...> Almost 30 years ago, everything was only on paper <...> Now, I think most people have their workbooks in the digital space, out there in the clouds, like Benchling’ ‘Research starts with an experiment and a detailed description of it. <...> If you learn something today that you can’t explain, you might be able to explain it in a month or a year. <...> An example now is the need for domains that were made ten years ago’ |

|

‘Experimentation is the basic building of knowledge. You experiment and then people talk to each other at different levels’ ‘The old methodology of using notes works for us and probably still does. Because there are a lot of experiments that don’t work as well as we would like or at all. And we can’t put it in papers <...> it just stays in notebooks’ |

|

|

Team and individual meetings, scientific discussions |

‘We <...> don’t have regular meetings’ ‘We try to have a traditional weekly live meeting. <...> It is also a discussion of scientific problems, <...> news. <...> If someone is sick <...> it will be a hybrid meeting. <...> It’s not only our regular staff who are involved in the meetings, but <...> also students’ ‘I have regular discussions with each of the staff about their work. Plus, we do our group seminars regularly, where everyone presents the results of their research and then we have a group discussion in order to get some additional comments, questions or some insights’ ‘During the weekly meetings, we discuss <...> current issues of the experiments as well as the daily life of the lab <...>. Every month, the whole group meets’ |

|

Scientific publications |

‘Scientific publications, peer-reviewed at international level, are key’ ‘To disseminate knowledge to the scientific community’ ‘In the world of science, the main thing is the scientific paper that we write through discussion and collaboration’ ‘It’s very important to read publications, to take an interest, because ideas actually come from elsewhere. Knowledge is created on a comparative basis, meaning you try to understand a system by comparing it with other similar systems <...> everything in nature is connected’ |

|

Reflection, feedback |

‘In individual meetings, when we reflect on the previous week’s work or on the work of a certain period <...> how you did, your efficiency, your mistakes. It may create knowledge, but it’s more for that individual to learn from that knowledge than <...> for others to benefit from it’ ‘That feedback from others, not necessarily from members of your working group, but from colleagues who may have had some more experience with the method, is very important’ |

The ICT used by principal investigators can be divided into four categories – online data repositories with an authentication system, online document preparation and editing tools, databases and platforms for online calls, and instant messaging (Table 2). The most frequently mentioned options were online data repositories with an authentication system, which allow scientific research team members to see each other’s results, read articles, create and manage file versions, help exchange information and knowledge within the team, make it easier for principal investigator to monitor the progress of the members’ work, and also ensure the preservation of information despite the failures of the devices used. Online document preparation and editing tools allow researchers writing scientific publications to edit the same document simultaneously and avoid creating multiple copies of the file, and using one of such tools – LaTeX, in which information and document formatting are encoded in the ASCII code – also allows saving storage memory and affords reliable control of information. Scientific research teams use various databases. Some are designed to store unpublished, confidential research results within the team. Others have open access and help share accumulated knowledge from conducted research with the scientific community. One informant states that an access to research results and data obtained from other scientific research teams helps to assess the feasibility of the desired experiment and plan it, i.e., to check whether such studies have already been conducted, what are the results, whether they correspond to the data that the informant received, which methods do not yield results, etc., which makes scientific work more efficient. Internet calling and instant messaging platforms enable scientific research teams to exchange information, participate in discussions and solve emerging problems quickly and independently of the geographical location.

Thus, ICT is most useful in the sense that it helps to share knowledge and information quickly and reliably, provides the opportunity to consult remotely regardless of the geographical location, and simultaneously prepare documents or scientific publications.

Table 2. ICT that are used in scientific research teams

|

Category: ICT |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Subcategory |

Tools |

Benefits of tools |

Illustration of proposition |

|

Internet-accessible data storage with authentication system |

- Tortoise SVN - Google Drive - SharePoint / OneDrive - Benchling |

Allows team members to see each other’s results and the articles they are reading |

‘Everybody who does something, everybody else sees what they are doing, <...> if you read an article and you put it in a shared library <...> we all know that our colleague has read that article and when we need to find it, it is much easier for us, <... > so we can expand our knowledge faster’ ‘Storing everything in the cloud is also an accessibility improvement at the team level’ |

|

Allows the team leader to monitor the progress of the members’ work |

‘Benchling can see all the progress, can share with the manager and he can follow’ ‘Improves data management for the team leader, it’s really easier, it’s more efficient to see and manage everything, to follow the progress’ |

||

|

Allows the creation and management of versions of a file (reduces chaos and allows undoing changes to the file) |

Subversion control system SVN allows you to write short comments about uploaded files. ‘That’s the point, you upload one version, and the layer is already there’ |

||

|

Helps to share information and knowledge within the team |

‘We put it up there <...> for accessibility or else for sharing, because it’s very convenient’ ‘Anyone in the group can pick it up, look at it, remember what was said’ |

||

|

Speeds up the work of the team |

‘So that everyone can find it quickly, without having to ask a team member. <...> If something runs out, everyone can post it in a folder <...> and then anyone can see it immediately <...> and take care of it in advance’ ‘The notes are in the clouds, <...> so that you don’t have to encrypt handwriting’ |

||

|

Ensures that information is preserved despite failures of the devices used |

‘This is very safe, as we know that computers can sometimes completely burn up’ ‘The data is automatically backed up’ |

||

|

Online tools for documents drafting and editing |

- LaTeX - Google Docs - Google Sheets |

Allow simultaneous editing of the same document (all tools listed in the left column) |

‘We can read, write, comment on an article in real time, several people can work on it at the same time, it’s very convenient’ ‘The most useful platforms are the ones where you can access the same thing from different places, edit and revise together’ |

|

Save storage memory and allows reliable control of information (LaTeX only) |

‘We code in ASCII, so you don’t write space-consuming documents anymore <...> when you work in LaTeX, <...> you are always 100% in control [of information]’ |

||

|

Databases |

- Reaxys - SciFinder - Unnamed databases |

Help you to assess and plan the experiment you want to carry out |

‘There’s Reaxys, there’s SciFinder, where you look for information there, check a lot of things, and you can do a lot of things more efficiently and quicker, plan things better’ |

|

Provides open access to data for the whole world |

‘We have a database which is a double-acting open access part for the whole world, where the data is already in print’ ‘The idea was to publish our team data in a way that would be accessible to everyone, and we have done that, and we‘ve published the database’ |

||

|

Allows you to protect confidential information |

‘We‘re putting up our own data that hasn‘t been published’ |

||

|

Online calling and instant messaging platforms |

- Google Meets - Discord - Slack - MS Teams - Skype - Messenger |

Expands opportunities for team and personal meetings |

‘We use it for online meetings <...> if someone can’t attend a lab meeting but would like to, or someone maybe couldn’t make it but wants to make it a one-to-one meeting’ ‘There are some activities where we only do them on Teams. <...> There are some where we are doing hybrid, so that has given a lot of convenience, if someone can’t come somewhere, they can just log in’ |

|

Enables quick transfer of knowledge to each other |

‘We use Discord for daily communication, for knowledge exchange’ ‘If you need to exchange that data between the members of the team <...> email, even Facebook Messenger, it happens that we send it, because it’s easier with a click of a button’ ‘Sometimes we send an email after we have edited an article’ |

||

|

Provides space for problem solving |

‘There is a team in MS Teams where we discuss the problems that we encounter’ |

||

The scientific research teams’ leaders who participated in the study identified six challenges related to information and knowledge management (Table 3):

a) Delayed completion of laboratory notes. When data collection is prioritized during experiments, these notes are often not completed on time, information is later forgotten by team members, and some of the data gets lost.

b) Team members’ lack of responsibility for data preservation. When completing laboratory notes, it is of importance to note the date and conditions of the experiment so that the results can be replicated and compared later.

c) Team members leave. The scientist Hey (2004) states that knowledge is created and applied in the minds of those who know, so it can be said that if a person leaves an organization, the knowledge in their mind also leaves. For this reason, all the data and information saved by the outgoing employees, usually students, become extremely important for the continuity of the scientific research team activities. According to the informants, the ideal situation is when a person completes the research, publishes it in a scientific article, and only then leaves, but this is usually not the case. As one of the solutions, the principal investigator tries to maintain systematic storage of domains in appropriate folders so that when a person leaves, it is easy to orientate themselves on what was done, and how the experiments were conducted.

d) Successful data and document management requires a system – an order, i.e., according to what criteria documents are placed in folders, and a repository, i.e., where to store data and various documents. One of the informants shared that due to the large variety of files and their historically different ways of describing them, it is difficult to create a document storage system that allows you to see the entire project picture. Another informant, whose scientific research team already has a system in place, faces a lack of storage space, because information is growing very rapidly, and, in order not to lose it, it is necessary to make copies.

Managing information sharing is another challenge for managers. Not all team members are willing to share information, in the sense that they try to control it, while others, on the contrary, want to spread it as widely as possible, and so it is a crucial task for the principal investigators to encourage people to take care that information does not disappear, and to prevent it from getting to the wrong people, such as competitors.

Table 3. Challenges faced by research team leaders

|

Category: Challenges |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Subcategory |

Small category |

Illustration of proposition |

|

Knowledge and data preservation |

Late completion of lab notes |

‘The description is a bit behind the experiments. <...> sometimes documentation is the weaker side of all experiments’ |

|

Team members not feeling responsible for preserving data |

‘Some are more dutiful, and they keep updating and uploading information, others need to be prompted’ ‘There are always challenges in terms of preserving the data <…> in terms of ordering it’ ‘There are times when something is lost, you still have to try things out, you have to repeat things, you don’t necessarily get it right’ |

|

|

Team member leaves |

‘We’ve always had the problem that <...> a person disappears, and the notes disappear’ ‘When a person leaves, you must replicate his results and… no way. You look at the notebooks he left behind, and the documents in digital format, and it doesn’t say exactly how it was. That’s why we keep trying to introduce students to some kind of internal standard’ |

|

|

Data and document management |

‘Our data comes from different areas and has its own history of different ways of describing it’ ‘Information is growing very fast <...> it is very important to make copies when storing information, because it can just disappear one day. <...> Some experiments generate very large volumes of data, <...> we have external disks that are standard, they don’t fit either’ |

|

|

Information sharing management |

‘Some team members want to control the information and not share it, others want to disseminate it as widely as possible, so there are two challenges – to get people to make sure that the information doesn’t disappear, and to make sure that it doesn’t get to someone it doesn’t need to get to’ |

|

When analyzing the influence of organizational culture on knowledge creation in scientific research teams, the informant noted the values fostered in the teams they led:

a) openness to sharing knowledge within the team and accepting other opinions, which enables team members to share their knowledge and experience, thus preventing the repetition of errors at the team level, and at the same time does not prevent the raising of new research hypotheses.

b) inclusiveness, which is defined as the inclusion of all researchers who contributed to the study in the list of authors of a scientific publication. The inclusiveness policy fostered in scientific research team helps team members, young researchers, to build their own network of colleagues and partners, and gradually become independent researchers.

c) support and professional growth, which not only allows team members to feel valued, but also enables them to develop new areas of research, bring new research methods to Lithuania, which unambiguously expands the thematic field of knowledge created by scientific research team.

d) responsibility for the orderly collection and storage of information that forms the basis of knowledge (Table 4).

Thus, the results suggest that organizational culture has a significant impact on the effectiveness of knowledge creation in scientific research teams – it enables open sharing of information and knowledge within the team and fosters the development of self-directed young researchers who take on the task of creating knowledge in new scientific fields.

Table 4. Values fostered by scientific research teams

|

Category: Values |

|

|---|---|

|

Subcategory |

Illustration of proposition |

|

Openness to sharing knowledge and accepting others’ opinions |

‘The most important thing is openness <...> so that knowledge is open within our team’ ‘Everyone’s question, the idea raised is equally important <...> and we try to apply that “yes and” rule, <...> because this way some new hypotheses, ideas that are worth testing <...> may arise which may then turn into knowledge or negative results’ |

|

Inclusion |

‘Because we have this so-called inclusion policy in the laboratory, we will more quickly include those who have contributed relatively little to a specific article. <...> together they learn from each other and grow’ |

|

Support |

‘We managed to create a laboratory that is truly a group of supportive people’ ‘I try to support and encourage <...> I think that people really <...> appreciate that support’ |

|

Growth |

‘I want independent people to grow in the laboratory’ ‘That monthly meetings of the team, or rather I would say, a human resources thing <...> for the growth of that specialist’ |

|

Responsibility |

‘So that everyone feels able to contribute to the whole team on the topics that we are developing, and so that they feel responsible for being here. <...> The responsibility is to get some results, to make some insights’ |

Findings and Discussion

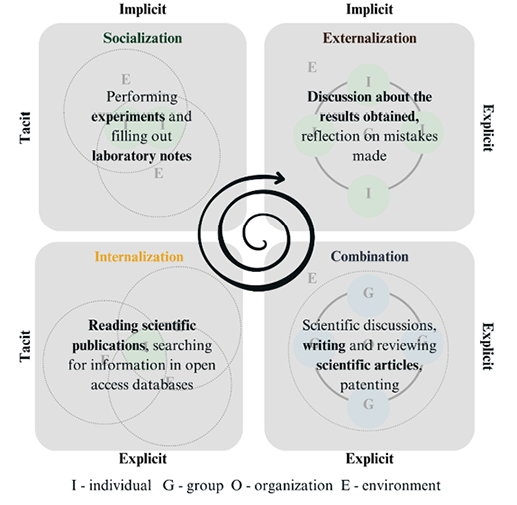

Knowledge creation occurs through the transformation of both explicit and implicit knowledge within a knowledge-based ecosystem, along with prior research indicates that everyone is involved in the process. Researchers’ insights presented in scientific literature, the review, and the study results provide a basis for identifying the knowledge creation process in scientific research teams in the life sciences. The study identifies the unique knowledge creation methods used by scientific research teams in life sciences, which align with the knowledge conversion (SECI) model proposed by Nonaka & Toyama (2003). During socialization, the researcher interacts with the environment, conducts experiments, collects data, and completes laboratory notes, i.e., translating tacit knowledge into implicit knowledge ready to be shared with colleagues. In externalization, the implicit knowledge acquired by the researcher is made explicit through discussion of experimental results or errors made by the scientific research team. The team’s explicit knowledge is combined with that from other experiments and preserved in scientific publications or patents. Nevertheless, combining different types of knowledge scientific research team members, mostly principal investigators, needs to use tools and artefacts proposed in the Activity Theory model. Writing scientific publications involves scientific discussion at the team, department, or project level and peer review from other scientists in the field, thus combining the knowledge of many different research teams into a single scientific product. Internalization involves reading scientific publications and searching open-access databases for information to design new experiments and hypotheses that emerge in project-based single-loop or double-loop organizational learning (Figure 5. The process of knowledge creation in scientific research teams).

Figure 5. The process of knowledge creation in scientific research teams

The literature review and empirical study specify that two criteria are needed for an effective knowledge creation process:

a) Building the right organizational culture. Scientific research teams foster an open organizational climate for knowledge sharing, characterized by trust, acceptance, inclusiveness, support, professional development, and responsibility, enabling open information sharing within the team and cultivating autonomous young researchers who take up knowledge creation in new scientific fields.

b) Usage of information and communication tools. Researchers Bailey et al. (2012) and Griffith et al. (2003) argue that ICT is an integral part of coordinating work in teams, and is particularly useful in geographically distributed teams. The study shows that ICT helps scientific research team leaders perform their jobs more efficiently, given the flow of the fifth industrial revolution and the breakthrough of artificial intelligence by facilitating rapid, reliable knowledge sharing, enabling remote consultation regardless of the geographical location, and supporting the simultaneous production of papers or scientific publications.

Conclusions and Suggestions

• The theoretical analysis of the knowledge creation process suggests that knowledge creation occurs in the Ba space, when the explicit and tacit knowledge of the organization’s knowledge assets is transformed into one another during the knowledge conversion (SECI) process. In the knowledge creation process, principal investigators play an important role, setting a vision for knowledge, creating and managing it, and promoting continuous knowledge conversion. During knowledge conversion, the existing knowledge is expanded both qualitatively and quantitatively, thus creating added value for the organization. Ba is described as a shared space for knowledge creation, with four types distinguished: initiating, interacting, cybernetic, and practitioner. The meaning of space correlates with the stages of the SECI process.

• Knowledge creation in scientific research teams occurs by conducting research based on already existing knowledge and is the primary goal of R&D projects. Scientific research teams are designed to address complex scientific questions and are classified by the expertise of their members as unidisciplinary, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, or transdisciplinary. They face challenges posed by cultural and organizational norms, career stages, differences in communication and work styles, and situations of mass motivation, which can be mitigated, and favorable conditions for knowledge creation are created by an appropriate organizational culture. The quality of scientific work, the integrity of scientific research team leaders, and the compliance of R&D projects with the requirements of the scientific field, national and international priorities, and government institutions depend on scientific research team leaders’ leadership practices. The duration of project implementation is shortened by effective knowledge sharing between teams, and the team members’ use of ICT. The principal investigator’s effective role must account for medium- and long-term scientific visions and perspectives.

• According to the results of the qualitative study, the knowledge creation process in life sciences scientific research teams take place, including the knowledge conversion (SECI) model. The following methods are used for knowledge creation: conducting experiments, documenting laboratory notes, reflecting on errors, participating in scientific discussions, patenting, reading, writing, and reviewing scientific articles, and searching for information in databases. Two criteria are essential for ensuring an effective knowledge creation process: fostering an appropriate organizational culture and using ICT tools.

• The research findings highlight the need for guidelines for scientific research team members, which emphasize the importance of each SECI model stage and its methods. A clear understanding of the specific methods that contribute to effective knowledge creation would help principal investigators and team members better appreciate one another’s interests when pursuing shared and individual goals, thereby improving interpersonal relations.

Author contributions

Simona Taparauskienė: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization.

Saulė Jokūbauskienė: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing, supervision.

References

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Review: Knowledge Management and Knowledge Management Systems: Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 107–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250961

Antes, A. L., Mart, A., & DuBois, J. M. (2016). Are Leadership and Management Essential for Good Research? An Interview Study of Genetic Researchers. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 11(5), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264616668775

Atkočiūnienė, Z. O., & Petronytė, A. (2018). Žinių kūrimo ir dalijimosi jomis poveikis inovacijoms. Informacijos mokslai, 83, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2018.83.2

Bailey, D. E., Leonardi, P. M., & Barley, S. R. (2012). The Lure of the Virtual. Organization Science, 23(5), 1485–1504. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0703

Burns, P. (2025). Corporate entrepreneurship and innovation (5th ed.). Bloomsbury academic.

Casati, A., & Genet, C. (2014). Principal investigators as scientific entrepreneurs. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 39, 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9275-6

Choi, B. C. K., & Pak, A. W. P. (2006). Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. Medecine Clinique Et Experimentale, 29(6), 351–364.

Cooke, N. J., Hilton, M. L., & National Research Council (Eds.). (2015). Enhancing the effectiveness of team science. The National Academies Press.

European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202401689

Faith, C., & Seeam, A. (2018). Knowledge sharing in academia: A case study using a SECI model approach. Journal of Education, 9(1), 53–70.

Gaižauskaitė, I., ir Valavičienė, N. (2016). Socialinių tyrimų metodai: Kokybinis interviu. VĮ Registrų centras.

Government of Republic of Lithuania. (2022, March 31). State progress strategy “Lietuva 2050” No. 2022-06482. https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/3338f790b0ea11ec8d9390588bf2de65

Greco, V., Politi, K., Eisenbarth, S., Colón-Ramos, D., Giraldez, A. J., Bewersdorf, J., & Berg, D. N. (2022). A group approach to growing as a principal investigator. Current Biology, 32(11), R498–R504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.04.082

Griffith, T. L., Sawy, J. E., & Neale, M. A. (2003). Virtualness and Knowledge in Teams: Managing the Love Triangle of Organizations, Individuals, and Information Technology. MIS Quarterly, 27(2), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036531

Hansen, M. T. (2002). Knowledge Networks: Explaining Effective Knowledge Sharing in Multiunit Companies. Organization Science, 13(3), 232–248. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3086019

Harris, S. G. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Human Resource Management, 29(3), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.3930290308

Hashim, N. H., & Jones, M. (2007). Activity theory: A framework for qualitative analysis. https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/conference_contribution/Activity_theory_a_framework_for_qualitative_analysis/27796473/1

He, Y., Li, F., & Liu, X. (2024). Research progress on the evaluation mechanism of scientific research teams in the digital economy era. Journal of Internet and Digital Economics, 4(3), 218–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIDE-04-2024-0016

Hey, J. (2004). The Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom Chain: The Metaphorical link. https://www.jonohey.com/files/DIKW-chain-Hey-2004.pdf

Hislop, D. (2009). Knowledge Management in Organizations: A Critical Introduction (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Jashapara, A. (2004). Knowledge Management: An Integrated Approach. Pearson Education Limited.

Jones, B. F. (2021). The Rise of Research Teams: Benefits and Costs in Economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35(2), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.35.2.191

Klaic, A., Burtscher, M. J., & Jonas, K. (2018). Person-supervisor fit, needs-supplies fit, and team fit as mediators of the relationship between dual-focused transformational leadership and well-being in scientific teams. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(5), 669–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2018.1502174

Leibold, M., Probst, G., & Gibbert, M. (2002). Strategic management in the knowledge economy. New approaches and business applications. Publicis.

Milojević, S. (2014). Principles of scientific research team formation and evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(11), 3984–3989. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1309723111

Misra, S., Hall, K., Feng, A., Stipelman, B., & Stokols, D. (2011). Collaborative Processes in Transdisciplinary Research. In M. Kirst, N. Schaefer-McDaniel, S. Hwang, & P. O‘Campo (Eds.), Converging Disciplines: A Transdisciplinary Research Approach to Urban Health Problems (pp. 97–110). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6330-7_8

Nickols, F. (2010). The Knowledge in Knowledge Management. https://www.nickols.us/Knowledge_in_KM.htm

Nonaka, I., & Toyama, R. (2003). The knowledge-creating theory revisited: Knowledge creation as a synthesizing process. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.kmrp.8500001

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., & Konno, N. (2000). SECI, Ba and Leadership: A Unified Model of Dynamic Knowledge Creation. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(99)00115-6

Prado-Gasco, V. J., Pardo, I. Q., Moreno, F. C., & Vveinhardt, J. (2015). Knowledge Management in R&D Teams at a Spanish Technical University: Measurement and Relations with Organizational Culture. Engineering Economics, 26(4), 398–408. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.26.4.9885

Research Council of Lithuania. (2024). Research Council of Lithuania Activity Report 2023. https://lmt.lrv.lt/media/viesa/saugykla/2024/5/zQUiJY4VXZ4.pdf

Salazar, M. R., Lant, T. K., Fiore, S. M., & Salas, E. (2012). Facilitating Innovation in Diverse Science Teams Through Integrative Capacity. Small Group Research, 43(5), 527–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496412453622

Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania. (2024, April 11). On the Approval of the Description of the Long-term Policy Development Directions for Science, Technology and Innovation in Lithuania. Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania. https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/rs/legalact/TAD/ad54f302f80311ee97d7f4f65208a4ec/

Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Currency Doubleday.

Stokols, D., Hall, K. L., Taylor, B. K., & Moser, R. P. (2008). The Science of Team Science: Overview of the Field and Introduction to the Supplement. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(2), S77–S89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.002

Tidikis, R. (2003). Socialinių mokslų tyrimų metodologija. Lietuvos teisės universiteto Leidybos centras.

World Economic Forum Future of Jobs. (2025, June). Future of Jobs Report 2025. https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_Report_2025.pdf