Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika ISSN 1648-2425 eISSN 2345-0266

2022, vol. 24, pp. 8–23 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2022.34

“It was a Shock to the Whole Family”: Challenges of Ukrainian Families Raising a Child with Autism

Tetyana Semigina

Academy of Labour, Social Relations and Tourism

Email: semigina.tv@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5677-1785

Olha Stoliaryk

Ivan Franko National University of Lviv

Email: olgastolarik4@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1105-2861

Abstract. Based on the family-centered approach and a consumer perspective this research examines the overall level of satisfaction with educational and social services of the families raising children with autism or autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in Lviv (Ukraine) and the challenges in interactions of such families with services. The survey (90 parents who are social work clients) and individual semi-structured interviews (30 parents) were used.

The findings indicate the respondents’ evaluation of the services they receive and inclusive education could not be qualified as favorable. Key challenges identified within the study are: problems of staff preparedness and lack of information about services; personal feelings of emotional burnout; unrealistic expectations from services; social stigma related to autism and social isolation of parents raising a child with ASD.

It is important for social workers to consider the need to collaboratively create the so-called social routers for families raising children with developmental disabilities during the early stages of family work. Verified information may reduce the parents’ stress and consolidate their efforts, help to avoid dubious treatments that are detrimental to the child’s health and are a significant financial burden to the family.

Keywords: family consumer perspective, access to service, autism, inclusive education, rehabilitation.

Received: 2021-11-22. Accepted: 2022-02-09

Copyright © 2022 Tetyana Semigina, Olha Stoliaryk. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The number of children with autism/autism spectrum disorders (ASD) is growing steadily around the world (Autism speaks, 2021). Gray (2002) argues that these children are characterized by low social competence, low level of communication, and specific behavior that complicates the process of their socialization. When a child has behavioral disorders and is diagnosed as ‘having autism’, a critical life situation emerges within the family. Researchers (Lovell & Wetherell, 2018; Pozo, Sarriá & Brioso, 2013) point out a number of quantitative and qualitative changes, difficulties and hardships faced by the family, such as: cultural stigma of autism nosology, associated stigma of parents and guardians, barriers to accessing services, family segregation, additional financial burden and other issues affecting the family’s quality of life and self-assessment of well-being. In many cultures, such families are excluded from society or feel blame for having ‘abnormal’ children (Chan & Lam, 2018; Dardas & Ahmad, 2014; Gray, 2002).

Thus, the family must adapt and adjust to the new challenges. Gordillo, Chu and Long (2020) suggest that the adaptation is possible through a reassessment of the social situation, balancing the adaptive needs and the families’ resources , revisioning of the family’s outlook, accepting the need and inevitability of change, and the development of coping strategies. Furthermore, a family raising a child with ASD needs a whole range of specific basic services including education, training, rehabilitation, medical and social services. Fong, Gardiner, Iarocci (2020) note that adequate, systematic access to services is one of the key factors influencing the quality of life of each individual family member and the child with autism.

In the post-Soviet countries, where Ukraine is building its educational policy, there is a lack of quality services in the field of inclusive and special education (An, Chan & Kaukenova, 2020). The implementation of the principles of inclusiveness in all spheres of life in Ukraine began with the reorganization of the education system in the 2000s, in particular the introduction of deinstitutionalization – the closing of boarding schools providing educational services on a paternalistic basis.

Current public policy in many countries promotes the practice of inclusive education (, 2015; , 2013), although, as in most post-Soviet countries, the process of involving the child in the educational environment is at the level of integration and segregation (Horishna, 2020; Sabo, Vančíková, Vaníková, & Šukolová, 2018). In Ukraine, the inclusion process takes place by creating an environment where everyone is provided with equal access to public policy services (Semigina & Chystiakova, 2020). As an alternative to inclusion, special institutions have been established to provide educational services for children with developmental disabilities: training and rehabilitation centers, special schools that should focus on taking into account the individual trajectory of the child’s development. However, the majority of specialized social and medical institutions are non-governmental private organizations operating on a fee-for-service basis. The existing institutions deal with different aspects of the child’s disorders, but their services don’t take into account the complex family situation. Thus, the social support in Ukraine is fragmented and it is not provided on a family-oriented basis (Gurzhiy, 2017; Lekholetova, Liach& Zaveryko, 2020; Stoliaryck, Semigina & Zubchyk, 2020).

The research aim is to explore to what extent the families that are raising children with ASD are satisfied with educational and social services, and to identify the challenges in interactions of such families with services.

The family raising children with asd: social work rerspective

Family adaptation to autistic children

The findings from different studies (Hoffman et al, 2009; Salceanu & Sandu, 2020; Vargas-Muñoz et al., 2017) prove that in many societies, disregarding the economic conditions of the national state, families raising children with mental and behavioral disorders belong to a social group with clear signs of vulnerability and disintegration. If a child is officially diagnosed with a disability, then, according to regulations, family members acquire a new status that regulates certain rights and responsibilities, which they may not always agree with. This process complicates the inner fears and anxieties of parents, provokes negative feelings – shame, resentment, guilt (Gray, 2002; Lovell & Wetherell, 2018; Sim et al., 2018). Some studies emphasize that stress is a consequence of the formed pathological emotional dependence in the relationship with the child (Hoffman et al., 2009).

Raising a child with disabilities determines the level of psychological well-being and quality of life of the individual family members and the family as a unit. Academic literature (Dardas & Ahmad, 2014; Usman. et al., 2021) suggests a number of research tools to measure the quality of life of those families who have children with disabilities and the role of social support for the family in the enhancement of family outcomes. Access to various services and parenting programs is considered one of the key determinants of the quality of life for families caring for children with ASD.

In recent decades, there has been a growing recognition of the importance of family-centered service delivery. Allen and Petr (1998) highlight three core elements of the family-based model – the family as the unit of attention, informed family choice, and a family-strengths perspective. This concept has significant social work practice, policy, and research implications.

Studies conducted in Ukraine (Chukhriy, 2012; Kovalyiova & Varina, 2020) and other countries (Anthony, & Campbell, 2000; Baumann et al., 2012; McCubbin & Patterson, 1983; Yu et al, 2018) has shown the co-existence of two approaches to the adaptation of families raising a child with mental disorders, including ASD: (1) adaptation as a process of adaptation to new conditions of reality by balancing the internal attitudes of the family in accordance with the requirements of the external environment; (2) adaptation of resources, opportunities of the social environment to the needs of family members by initiating social changes. Stainton and Besser (1998) emphasize that for the successful integration of the family into the social environment, in addition to the adaptation of family members to changes in the social situation, it is necessary to adapt the environment to the needs of the social group.

Collaborative approaches

The partnership between families and professionals is the foundation of family-centered social work. Academic research (Georgiou, 1996; Johnson & Briggs, 2021; Gallagher, Smith & 2016) has focused on parental involvement and motivation that play the pivotal role in ensuring children’s well-being. According to Barrat (2012), the relationships are seen as central to parental interventions whether between families or professionals. Parents who have established positive connections with social workers and other professionals were more likely to achieve positive results. At the same time, Dumbrill (2006), Forrester et al. (2019) pointed out that clarity in relations with families about what needs to be changed and the reasons for such activities, as well as sensitivity and willingness to tune into the parents’ perspective, may be much better to help parents become motivated and engage with services.

The idea of family (parent) involvement in decision-making and listening to their views is rooted in the overall social concept of the client-centered approaches and broadening users’ participatory process (Elsen & Lorenz, 2014; McLaughin et al., 2019). In addition, engaging families (and clients) in assessing services for their kids can help workers interact more effectively with families and, in so doing, improve permanency for children (Gross-Manos et al., 2019; Altman, 2008).

The introduction of inclusive practices in the Ukrainian educational space has become a driving force in creating a child-friendly environment for kids with mental disorders. However, there are still challenges that make it difficult to access quality education for this category of children. Thus, at present Ukraine faces problems related to the number of educational institutions in the community, their occupancy, the compliance of educational programs with the needs of children with mental disorders, etc. (Okseniyk, 2018). Parents feel overwhelmed and distressed, and their views are not taken into account.

Research methodology and organization

General background of research

The analysis is carried out from the standpoint of the theories of the social construction of reality (Engel & Schutt, 2016) that are in line with the modern understanding of the social cohesion nature of the social problems, generating critical and innovative knowledge production (IASSW, 2014). The research especially focuses on the points of views of the families raising children with autism. The family consumer perspective (MacDuffie, et al., 2020; Scheer, Kroll, Neri & Beatty, 2003) was used for constructing study tools and interpreting data. The assessment of the services that the parents are receiving and their satisfaction with them, the way they view their life situation, and their experience in interacting with the service providers constitute the core of the study approach.

This study was conducted in Lviv, Ukraine. The city has a small selection of service providers for families raising children with autism. Conditionally, they can be divided into 1) educational: special schools for children with complex disorders of intellectual/mental development, as well as training and rehabilitation centers for a specific nosology; 2) rehabilitation centers focused on the psychophysical rehabilitation of children; 3) inclusive resource centers (providing medical, psychological and pedagogical consultations on health and development of the child); 4) social centers (daycare centers for children, centers for supported living, social services and departments of social work). These institutions are mainly focused on children with autism, but not their parents. The number of children in these institutions is not large. It is worth mentioning that the statistical data on children with ASD is not available for Lviv, nor Ukraine in general.

Sample and procedures of research

The study lasted from March to May 2020 and consisted of two states. The mixed-methods design with the combination of a structured questionnaire (90 respondents) and semi-structured interviews (30 respondents) was employed. This design helps to balance the expressed ‘voices’ of parents with the quantified data by having more than one frame of reference (Thyer, 2001), or as Hopson and Steiker (2008) state, it allows the exploration of generalizable findings on specific measurable outcomes while capturing the influence of external contexts and subjective processes in a single study.

In the first stage of our study, we focused on the peculiarities of the interaction of the respondents with the service providers. The purposive sample consisted of parents raising children with autism. The criteria for inclusion of respondents were: (1) having a child up to 18 years old with officially registered ASD; (2) being a client of one of the services – Training and Rehabilitation Centre “Trust” (for families who regularly receive educational services), a consulting psychological and pedagogical centre “Trust” (for families who occasionally but not regularly receive educational and rehabilitation assistance), and Lviv City Centre of Social Services for Families, Children and Youth (for the families that are registered and receive social support services).

In total, we invited 105 clients for the interview. Some of them withdrew due to overload, others –due to COVID-19 quarantine measures. All in all, 90 parents were participants of the survey. The face-to-face interviews were arranged at the Centre “Trust”. The questionnaire on assessing the quality of life of the family was used. This tool has been tested for validity and contains questions within the following blocks: features of interaction with public institutions, social activity, family relationships, relationships with the child, child features, social support, and resource potential.

During the second stage of the study, 30 individual semi-structured interviews were arranged and conducted by phone. The respondents were those parents who participated in the survey and came from the families who receive educational and rehabilitation assistance at the Centre “Trust” on a non-regular basis. The interviews were aimed to find out what these families’ thoughts were on the availability and quality of services they receive. The interview guide for the qualitative part includes open-ended questions on: biased attitudes of specialists; correspondence of services with needs; cooperation with the service providers.

The study protocol was approved by the Academy of Labor, Social Relations and Tourism. All respondents signed an informed consent form to participate in the study and have the results processed. The clients were assured that their participation in the survey would not affect their rights to receive the services. The interviews were arranged in such a way as to facilitate access to parents’ perspectives and to delegate authority from the researcher to the participants (Thyer, 2001).

Data analysis

Methods of mathematical and statistical data processing (computer package of statistical analysis SPSS in version 22 were used to precede with the survey results. The interview results were coded, deciphered, and grouped into several block representing the families’ vision on interaction with the service providers. A thematic analysis was conducted, and the following core themes emerged: (1) the level of parents’ satisfaction with educational and rehabilitation services; (2) challenges and barriers in the interactions between the families and service providers. The results of the research are presented through descriptive analysis; also, some quotations from interviews are used throughout this paper. Ethical dilemmas, including security and confidentiality, were taken into account.

Results of the research

Characteristics of families and children

Among our 90 respondents there were 52 women and 38 men; 3 respondents were 18–24 years old, 22 respondents aged 25–34, 51 respondents were 35–44 years old, and 14 were over 45 (details on respondents’ characteristics are presented in Table 1).

Table 1. Social and demographic characteristics of respondents (n=90)

|

Respodents |

n=90 |

100 (%) |

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

38 |

42.2 |

|

Female |

52 |

57.7 |

|

Residence (as defined by the territorial administrations) |

||

|

City |

59 |

65.5 |

|

Urban type village |

21 |

23.33 |

|

Village |

10 |

11.11 |

|

Education |

||

|

Academic degree |

2 |

2.22 |

|

Higher education |

41 |

45.55 |

|

Incomplete higher education |

11 |

12.22 |

|

Vocational and technical education |

28 |

31.11 |

|

Secondary education |

8 |

8.88 |

|

Age |

||

|

18-24 |

3 |

3.33 |

|

25-34 |

22 |

24.44 |

|

35-44 |

51 |

56.66 |

|

45-60 |

14 |

15.55 |

|

Employment |

|

|

|

Working |

35 |

38,9 |

|

On maternity leave |

9 |

10 |

|

Not working |

41 |

45.5 |

|

Officially registered as unemployed |

5 |

5,6 |

The age range of children with autism who are raised by respondents is indicated as follows: 3–5 years (4 children, 4%), 6–7 years (12 children, 11%), 8–9 years (22 children, 24%), 10–13 years (34 children, 38%), 14–17 years (18 children, 20%).

All respondents noted that access to the services and social support is an important factor in the quality of life of a family raising a child with autism. However, the analysis of the survey results demonstrates that more than half of the respondents (61%) indicated that their children regularly visit education, training and rehabilitation services (M = 2.9, SD = 1.2).

Overall level of parents’ satisfaction with educational and rehabilitation services

The respondents’ evaluation of the services they receive could not be qualified as favorable. Thirty-one percent of the respondents (n = 29) indicated that the services offered by the social services market are not in demand and relevant to clients: they do not focus on the needs and resources of families; do not take into account the contextual and environmental conditions in which the family operates.

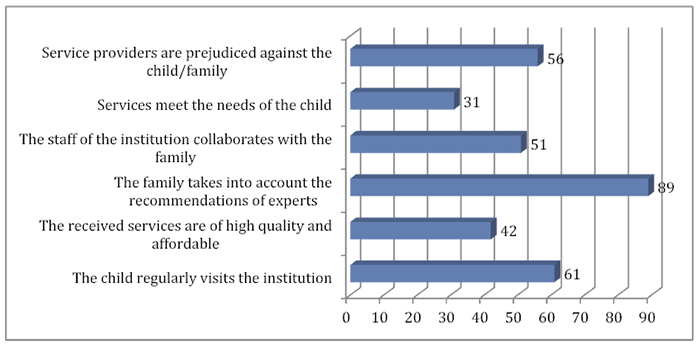

Slightly more than half of the respondents (51%, n = 46) reported cooperation between family and educational / rehabilitation institution (M = 2.7, SD = 1.1). Forty-two percent (n = 38) of the respondents consider educational services to be of high quality and affordable, and 56% (n = 52) reported stigmatization and prejudice. Eighty-nine percent (n = 80, M = 2.2, SD = 0.8) of the families take into account the recommendations of experts (Figure 1).

Only 48% of all respondents were informed about the family social services; 47% of the respondents consider the provided services as targeted (received at the place of residence). It means that in many cases social workers do not assess the living conditions of vulnerable families and their family traditions, and do not observe the behavior of family members in their natural conditions of functioning.

Figure 1. Families’ evaluation of services received by a child with autism (n = 90; %)

Parents raising older adolescents have much greater difficulty accessing educational and social services than parents with children of primary school age and adolescence.

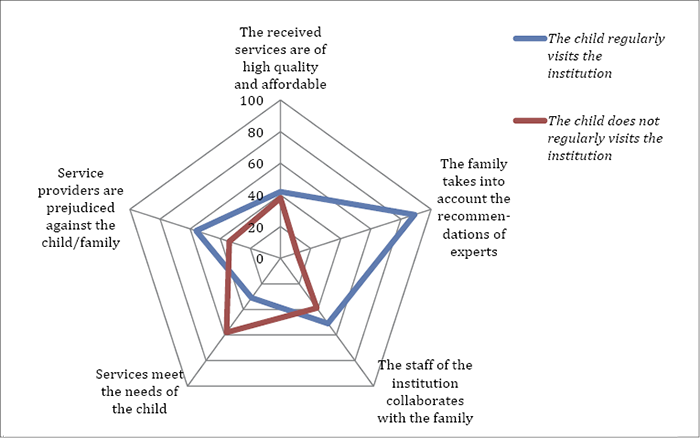

Low indicators of territorial accessibility of the services (39%) evidence only a partial coverage of the vulnerable groups of clients and the existence of social injustice, as clients living the remote areas remain deprived of the necessary social support (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Peculiarities of cooperation of the families with the support services for children with autism (n=90; %)

Challenges in the interactions between the families and service providers

In the survey, a notable number of the respondents (n = 39) indicated difficulties in accessing information. Among the problems, the respondents mentioned a lack of the coordinated support of specialists after the diagnosis, uncertainty as to the child’s educational route, the lack of contact cards and the overload of the media space with unverified information about the treatment protocols, correction, and education of a child with autism.

The parents shared their experiences in the interviews. For example, Taras, the father of a girl with autism (15 years old)1, told us:

“When she was diagnosed, it was a shock to the whole family. Back then, no one talked about autism as openly as they do now. In social work departments, employees talked about the complexity of the diagnosis, its uniqueness, but there were no clear recommendations on where to go for help. It is because of the lack of information that our child has lost the opportunity for early intervention.”

A substantial share of the respondents (n = 57) suffered from stigma while receiving educational, training or rehabilitation services. Educational providers, especially those within the inclusive educational institutions, often labeled a child with autism as incapable for learning. Peculiarities of the child’s behavior, the complexity of the symptoms, and the routine rituals affect the assessment of the child’s abilities and capabilities by the employees of the educational institutions.

In addition to primary stigma, families with a child with autism suffer from secondary (auto) stigma. According to the results of the interview, the parents of a child with autism are prejudiced against educational service providers, their own child and themselves. Tetiana, the mother of a boy with autism (7 years old), was critical toward social service employees:

“Social workers, inspecting the flat, asked ‘Do you need financial help?’ We were shocked! We are in a good financial position, provided with everything we need and even more. It turned out that the social pedagogue (maybe social worker?) at the institution where the child studies noticed that the son was always in the same clothes and in any weather in the same shoes (rubber sneakers), so he turned to them. We had to explain to them for a long time that my son has a routine ritual of choosing clothes – he wears only what attracts him very much and may not change his clothes for months.”

Some respondents (n = 31) indicated a lack of balance between the child’s own expectations and learning outcomes. Often, parents believe that specialists do not assess the level of development of the child and view a child through the lenses of a disease, choosing simple training programs that slow down the development of the child.

Sometimes, parents find it necessary to monitor the learning process on a par with professionals. For example, Galina, the mother of a girl with autism (11 years old), shared her experience:

“I read a lot of academic literature, was interested in research in this field, studied the experience of international schools and organizations. I always ask the teacher to show us the calendar-thematic planning for each individual subject. Looking at the topics, I repeatedly notice that the curriculum is too easy for my child. For the most part, all lessons are reduced to a game, it slows down the child’s development.”

However, there is a small number of parents who admitted that they had underestimated the child’s abilities and misplaced the child’s areas of development. Victoria, the mother of a boy with autism (9 years old), told us:

“We are in a classroom that combines several nosologies: typical speech disorders, Down syndrome, and autism. We were transferred there last year, saying that my son could follow a stronger curriculum. We initially objected, because M*** is not verbal, not always capable of self-service, and here you need to do homework, solve problems. To our surprise, the son easily adapted to the new class. It seems to me that if he could speak, his words would be “Well, finally!”. We spent so much time developing everyday skills that were probably not interesting or important enough for him, at a time when there was a need to satisfy the cognitive processes.”

The next challenge is unpreparedness or lack of staff within the service providing institutions. The respondents (n = 58) consider that educational / rehabilitation institutions are not staffed by professionals who have special training in methods of working with children with a specific behavior. According to the parents, specialists are often afraid of such children, because of their physical and verbal outbursts of aggression and their behavioral patterns, and do not know how to interact with them. For example, Vitaly, the father of a boy with autism (8 years old), recalled the time when his child started to go to an inclusive school:

“After the first day of school, I noticed that my son was excited. After talking to the assistant, I found out that the teacher was conducting a lesson with the class, he paid almost no attention to the child. He approached only at the beginning of the lesson, giving printed forms with ready-made tasks. To the assistant’s remark that the boy needed the task to be explained to him, the teacher replied: “How should I explain it to him if he isn’t even looking at me! I was not taught how to work with such children!”

Almost two-thirds of the respondents (n=67) noted that they suffer from emotional burnout, which is provoked by low internal or external resources. The correction, rehabilitation, and development of a child with autism is a difficult niche that requires time and has large financial and psychological costs. Emotional burnout, internal indifference, and acquired hospitalism occur when the level of costs is high while the result on which the resource is concentrated is low. An important factor is the availability of an external resource – social support, which can help cope with life’s challenges.

Oksana, the mother of a boy with autism (9 years old), shared her emotional dismay:

“I think we tried everything we could. And inclusion, and training in rehabilitation centers, and individual (private lessons). However, if it wasn’t sad, I see a regression. I understand that the behavioral symptoms are becoming more complex, there are often “kickbacks” (note that the child loses the acquired skills) and I understand that nothing will help him, there is no way out…”

Social isolation could be defined as one challenge for parents raising a child with ASD. In the interviews, parents stressed that the birth of a child with developmental disabilities affects their mobility and social activity. Families face misunderstandings and social exclusion, and moreover, they isolate themselves from the world, wanting to communicate only with “their own kind” or those who are involved in their problems.

Anna, the mother of a girl with autism (15 years old), expressed the following:

“We rarely go anywhere. In fact, it is not easy at all: to communicate with people who do not always understand you, for whom your difficulties are invisible. Our only friends are parents from a public organization who also raise such children.”

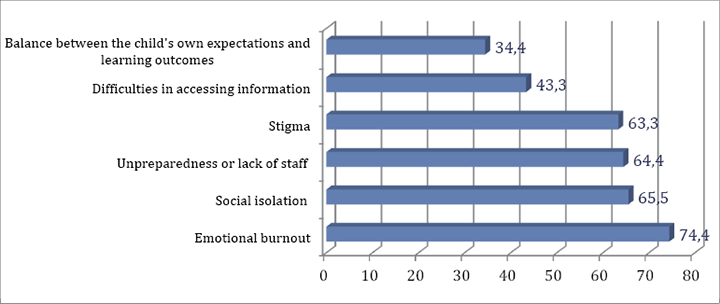

Figure 3 visualizes the challenges in the interactions between families and service providers that were identified during the study.

Figure 3. Barriers in interaction with service institutions: family vision (n=90; %)

So, the results of the study demonstrate that the interactions between families raising children with autism and providers of educational, training and/or rehabilitation services are complicated by a number of interrelated factors. Some of them are of the organizational nature – problems of staff preparedness and the lack of information about services. The personal feelings of emotional burnout and unrealistic expectations from services are strengthened by the social stigma related to autism and the social isolation of parents raising a child with ASD.

It was also stated during the interviews that the financial situation in particular in these families is unstable, and family members are forced to use loans, which may be due to material costs for services related to the child’s illness and the need for constant child care, which, in turn, complicates opportunities of employment and regular employment possibilities for parents. However, other factors may include low financial literacy or inability to plan and allocate the family budget.

Discussion

Social work practice is always embedded with problems of living that require a person-in-environment perspective to address them (IASSW, 2014). The limitation of our study, and in particular of this paper, is that we did not describe in detail the context of service provision for children with ASD and their parents. A decontextualized analysis was used to explore the views of parents. The sample was relatively small and purposive. Yet, our respondents belong to the ‘hidden population’ as there is little information about families raising a child with ASD. Therefore, despite non-representativeness and a biased selection of respondents, who represent only the regional base of social services’ clients, we hope that this research will appeal to those who want to understand the realities of a post-socialist country with underdeveloped social work practices.

Notwithstanding the described limitations, the findings of our research indicate that families raising children with ASD bear signs of vulnerability and disintegration, and thus the research confirms the position of other authors (Hoffman et al, 2009; Gray 2002; Lovell & Wetherell, 2018; Pozo, Sarriá & Brioso, 2013; Salceanu & Sandu, 2020; Vargas-Muñoz et al., 2017).

Worldwide educational and rehabilitation institutions are increasingly adopting consumer-directed approaches (Laver et al., 2018; Pritchard, Cotton, Bowen, & Williams, 1998). The same is valid for social work education. Researchers (McLaughin, Duffy, McKeever & Sadd, 2019) pointed out that service users and caregivers can be effectively involved in social work curriculum planning, delivery, assessment, and management.

Our study affirms a high level of unfulfilled needs of parents who have children with ASD or other intellectual developmental problems. The findings indicate that currently in Ukraine, educational and rehabilitation services for children with ASD and their families are far from consumer-driven programs. Having a child diagnosed with autism still makes a family socially excluded from society, while existing services for children with ASD are partially unavailable and not always fit the expectations of the families.

On the other hand, our research confirms the necessity of an adequate assessment of a child’s capabilities by the parents, taking into account the balance between expectations and abilities. Thomas, King, Mendelson and Nelson-Gray (2018) showed a similar problem: parents, who suppose that they know their children best, attribute to them certain traits which they do not possess, or, conversely, focus not so much on the children’s abilities but on the skills that will help them function in society.

So, it is important for educational and rehabilitation service providers to critically consider the vision of families when planning social support and developing interventions.

Firstly, we share the opinions of Anthony and Campbell (2020), Avendano and Cho (2020), that a social worker should establish a process of cooperation between educators, special educators and families raising a child with autism. It is important for social workers to consider the need to collaboratively create the so-called social routers for families raising children with developmental disabilities during the early stages of family work. Verified information may reduce the parents’ stress and consolidate their efforts and help avoid dubious treatments that are detrimental to the child’s health and mean a significant financial burden on the family.

Secondly, social workers, educational and rehabilitation service providers have to build up internal and external resources of the family. We stand in solidarity with Rios, Aleman-Tovar and Burke (2020) that chronic fatigue, financial instability, lack of time, the burden of child care, and interactions with educational and social service providers are a cause of stress and internal burnout for family members, especially women. In this case, a good tool for social support is the external resources of the family: close relatives, friends, and the community. The research findings were suggestive, not definitive in describing the optimum choice of interventions. A series of observations should be carried out to show which methods and forms would actually be preferred by families.

Conclusions

Our research confirms that in Ukraine, children with ASD are still not fully covered by educational and social services. According to the parents, the compliance of existing services with the needs of a child is not high. Clients living in remote areas remain deprived of the necessary social support. Family-oriented services are scarce, and parents do not have enough information on them.

The undertaken research allows defining the challenges faced by the families raising children with ASD. These challenges can be grouped into several blocks: information vacuum and/or disinformation, high level of stigma/self-stigma, mismatch between the parents’ expectations and the results of the educational and rehabilitation process, lack of professional staff, an artificial, isolated environment in which the family operates. These factors affect the parents’ assessment of the educational services that exist and affect their quality of life. Many parents still do not have sufficient access to information on the organization of their child’s life path and educational trajectory, which is a disadvantage for the promotion of inclusive and special education.

In order to understand the needs of the family as much as possible, social workers should move away from the position of a service provider and take the position of an “observer-researcher” to see the life situation through the eyes of the family members. This will allow social intervention plans to be sensitively adapted to the real needs of the family.

References

Allen, R.I. & Petr, C.G. (1998). Rethinking family-centered practice. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(1): 4-15. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080265

Altman, J.C. (2008). Engaging families in child welfare services: worker versus client perspectives. Child Welfare, 87(3): 41-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19189804/

An, S., Chan, C. K., & Kaukenova, B. (2020). Families in transition: Parental perspectives of support and services for children with autism in Kazakhstan. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 67(1), 28-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2018.1499879

Anthony, N., & Campbell, E. (2020). Promoting Collaboration Among Special Educators, Social Workers, and Families Impacted by Autism Spectrum Disorders. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 4(3), 319-324. doi: 10.1007/s41252-020-00171-w

Autism speaks (2021). Autism Statistics and Facts. Retrieved from: https://www.autismspeaks.org/autism-statistics-asd

Avendano, S. M., & Cho, E. (2020). Building Collaborative Relationships with Parents: A Checklist for Promoting Success. Teaching Exceptional Children, 52(4), 250–260. doi: 10.1177/0040059919892616

Baumann, M. et al. (2012). Social integration of children with special educational needs - opportunity and responsibility. Land Salzburg. https://www.salzburg.gv.at/bildung_/Documents/soziale_integration_english_ohne_vw.pdf

Chan, K.K.S. & Lam, C.B. (2018). Self-stigma among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 48, 44-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.01.001

Chukhriy, I. V. (2012). Factors of social and psychological adaptation of mothers raising a disabled child. Current problems of education and upbringing of people with special needs: a collection of scientific papers, 9 (11): 210-228.

Dardas, L. A., & Ahmad, M. M. (2014). Quality of life among parents of children with autistic disorder: A sample from the Arab world. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35 (2), 278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.10.029

Dumbrill, G. (2006). Parental experience of child protection intervention: A qualitative study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 30(1): 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.08.012

Elsen, S. & Lorenz, W., eds. (2014). Social Innovation, Participation and the Development of Society. Bozen-Bolzano University Press.

Engel, R. J. & Schutt, R. K. (2016). The Practice of Research in Social Work. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Fong, V. C., Gardiner, E., & Iarocci, G. (2020). Can a combination of mental health services and ADL therapies improve quality of life in families of children with autism spectrum disorder? Quality of Life Research, 29(8), 2161–2170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02440-6

Gallagher, M., Smith, M. & Hardy, M. (2016). Children and families’ іnvolvement in social work decision making. Children and Society, 26: 74-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00409.x

Georgiou, S. N. (1996). Parental involvement: Definition and outcomes. Social Psychology of Education, 1(3): 189-209. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02339890.

Gordillo, M. L, Chu, A. & Long, K. (2020). Mothers’ Adjustment to Autism: Exploring the Roles of Autism Knowledge and Culture. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45 (8), 877–886. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa044

Gray, D. E. (2002). «Everybody just freezes. Everybody is just embarrassed»: Failed and enacted stigma among parents of children with high functioning autism. Sociology of Health & Illness, 15 (1), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00316

Gross-Manos, D et al. (2019). Two sides of the same neighborhood? Multilevel analysis of residents’ and child-welfare workers’ perspectives on neighborhood social disorder and collective efficacy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(6): 682-692. doi: 10.1037/ort0000348.

Gurzhiy, N. (2017). Consumer awareness on non-medical interventions for autistic children and adults in Ukraine. Visnyk Akademiyi pratsi, sotsial’nykh vidnosyn i turyzmu, 3: 48-56.

Hardy, I. & , S. (2015). Inclusive education policies: discourses of difference, diversity and deficit. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(2): 141-164. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2014.908965

Hoffman, C. D., Sweeney, D. P., Hodge, D., Lopez-Wagner, M. C., & Looney, L. (2009). Parenting stress and closeness: Mothers of typically developing children and mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(3): 178–187. doi:10.1177/1088357609338715

Hopson, L. M., & Steiker, L. K. H. (2008). Methodology for evaluating an adaptation of evidence-based drug abuse prevention in alternative schools. Children & Schools, 30(2): 160. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2903757/

Horishna, N. (2020). The development of the category of inclusive education in philosophical-educational concepts and modern scientific discourse. Social work and education, 7(1): 56-64. https://doi.org/10.25128/2520-6230.20.1.5.

IASSW (2014). The IASSW Statement on Social Work Research. Retrieved from: https://www.iassw-aiets.org/the-iassw-statement-on-social-work-research-july-2014/

Johnson, W.E. & Briggs, H.E. (2021). Interventions with Fathers: Effective Social Work Practice for Enhancing Individual and Family Well-Being. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(8): 791-796. doi:10.1177/10497315211047187

Kovalyova, O.V. and Varina, G.B. (2020). Conceptualization of a family-centered approach in the process of developing adaptive resources of parents raising children with special needs. Topical Issues of Society Development in the Turbulence Conditions: Conference Proceedings of the International Scientific Online Conference (p. 351-360). Bratislava.

Laver, K. et al. (2018). Introducing consumer directed care in residential care settings for older people in Australia: views of a citizens’ jury. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 23(3): 176-184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819618764223

Lekholetova, M., Liach, T. & Zaveryko, N. (2020). Problems of parents caring for children with disabilities. Society. Integration. Education. Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. IV (p. 268-278). http://journals.ru.lv/index.php/SIE/article/view/4945

Lovell, B. & Wetherell, A. (2018). Caregivers’ characteristics and family constellation variables as predictors of affiliate stigma in caregivers of children with ASD. Psychiatry Research, 270, 426-429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.09.055

MacDuffie, K., et al. (2020). “If He Has it, We Know What to Do”: Parent Perspectives on Familial Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45 (2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsz076

McCubbin, H.I., & Patterson, J.M. (1983). The family stress process: The double ABCX model of adjustment and adaptation. Marriage & Family Review, 6(1-2), 7-37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v06n01_02

McLaughin H., Duffy J., McKeever B., Sadd J., eds. (2019). Service User Involvement in Social Work Education. Abington: Routledge.

. (2021). Making inclusion matter: critical disability studies and teacher education. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 53(3): 298-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2021.1882579

Oksenyuk, O. (2018). Social support for the family of a child with special needs. Social work and education, 5(1): 38-46. http://journals.uran.ua/swe/article/view/128699/123787

Pozo, P., Sarriá, E., & Brioso, A. (2013). Family quality of life and psychological well-being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: a double ABCX model. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58 (5), 442 –458. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12042

Pritchard, C., Cotton, A., Bowen, D. & Williams, R. (1998). A Consumer Study of Young People’s Views on their Educational Social Worker: Engagement as a Measure of an Effective Relationship. The British Journal of Social Work, 28(6): 915–938. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23714914

Rios, K., Aleman-Tovar, J., & Burke, M. M. (2020). Special education experiences and stress among Latina mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 73, 101534. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101534

Sabo, R., Vančíková, K., Vaníková, T., & Šukolová, D. (2018). Social Representations of Inclusive School from the Point of View of Slovak Education Actors. The New Educational Review, 54(4), 247-260. doi: 10.15804/tner.2018.54.4.20

Salceanu, C. & Sandu, M. (2020). Anxiety and depression in parents of disabled children. Technium Social Sciences Journal, 3(1): 141–150. https://doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v3i1.92

Scheer, J., Kroll, T., Neri, M.T., & Beatty, P. (2003). Access barriers for persons with disabilities: The consumer’s perspective. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 13(4): 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/104420730301300404

(2013) How do we make inclusive education happen when exclusion is a political predisposition? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 17(8): 895-907. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2011.602534

Semigina, T., & Chystiakova, A. (2020). Children with Down Syndrome in Ukraine: Inclusiveness Beyond the Schools. The New Educational Review, 59, 116-126. doi: 10.15804/tner.2020.59.1.09

Sim, A. et al. (2018). Factors associated with stress in families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental neurorehabilitation, 3: 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518423.2017.1326185

Stainton, T. & Besser, H. (1998). The positive impact of children with an intellectual disability on the family. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 23(1): 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668259800033581

Stoliaryck, O., Semigina, T. & Zubchyk, O. (2020). Family social work: the realities of Ukraine. Scientific bulletin of South Ukrainian National Pedagogical University named after K. D. Ushynsky, 4 (133): 38-46.

Thomas, P. A., King, J. S., Mendelson, J. L., & Nelson‐Gray, R. O. (2018). Parental psychopathology and expectations for the futures of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(1), 98-105. doi: 10.1111/jar.12337

Thyer B. A., ed. (2001). The handbook of social work research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Usman, A. et al. (2021). Assessing the Quality of Life of Parents of Children With Disabilities Using WHOQoL BREF During COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fresc.2021.708657/full

Vargas-Muñoz, M.E. et al. (2017). Maladjustment in families with disabled children. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 237: 863-868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.184

Yu, Y. et al. (2018). Using a model of family adaptation to examine outcomes of caregivers of individuals with autism spectrum disorder transitioning into adulthood. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 54: 37-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.06.007

1 All names were changed.