Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika ISSN 1648-2425 eISSN 2345-0266

2022, vol. 25, pp. 62–79 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2022.48

Exploring Gender Stereotypes among Prospective Foster Families

Alla Yaroshenko

Academy of Labour, Social Relations and Tourism

alla.yaroshenko@outlook.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0112-3112

Tetyana Semigina

National Qualifications Agency

semigina.tv@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5677-1785

Abstract. One of the acute social work issues in Ukraine is the deinstitutionalization of care for orphans and children left without parental care and the introduction of family care models. It is known that the success of such models largely depends on the motivations and values that inspire parents to place children, the socio-psychological characteristics of family members, gender aspects such as the distribution of household workload, the involvement of men in performing housework and care for children and so on.

Building on social role theory, we examine gender stereotypes of prospective foster parents in Kyiv, Ukraine. The exploration of femininity and masculinity stereotypes was carried out using the Sex-Role Inventory (Bem, 1974), while the assessment of ambivalent sexism in the attitudes toward women and men was done through using a short version of the methodology of Glick and Fiske (1996). 83 paricipants of the mandatory trainings for prospective foster parents were questioned.

Our study reveals that the prospective foster parents hold a biased set of beliefs. Almost a third of respondents’ responses concerning women show high indicators on the femininity scale and concerning men – on the masculinity scale. Also, respondents demonstrate a greater extent of benevolent rather than hostile sexism and describe a generalized image of women and men as androgynous individuals. High levels of hostility to feminism, especially among women, have been reported.

Ukraine has all legal grounds for gender equality. Thus, from the intersectional point of view, the study results highlight the impact of culture and social norms on perceptions of gender and gender stereotyping.

The paper ends with suggestions on training programs for both prospective foster parents and social workers, enchancing egalitarian family patterns and agency of women.

Keywords: gender stereotypes, social roles, femininity, masculinity, foster care.

Atskleidžiant su lytimi susijusius stereotipus būsimų globėjų šeimose

Santrauka. Viena iš aktualių socialinio darbo problemų Ukrainoje – našlaičių ir be tėvų globos likusių vaikų globos deinstitucionalizavimas ir globos šeimoje modelių diegimas. Žinoma, kad tokių modelių sėkmė labai priklauso nuo motyvacijos ir vertybių, skatinančių tėvus globoti vaikus, šeimos narių socialinių ir psichologinių savybių, lyčių aspektų, kaip antai namų ūkio darbo krūvio paskirstymo, vyrų įsitraukimo į namų ruošos darbus ir rūpinimąsi vaikais ir kt. Remdamiesi socialinio vaidmens teorija, nagrinėjame būsimų globėjų lyčių stereotipus Kijeve, Ukrainoje. Moteriškumo ir vyriškumo stereotipai buvo tiriami naudojant Sex-Role Inventory (Bem, 1974), o ambivalentiško seksizmo požiūryje į moteris ir vyrus vertinimas atliktas naudojant trumpą Glicko ir Fiske (1996) metodikos versiją. Apklausti 83 būsimiems globėjams skirtų privalomųjų mokymų dalyviai.

Mūsų tyrimas atskleidė, kad būsimi globėjai turi šališkų įsitikinimų. Beveik trečdalis respondentų atsakymų apie moteris rodo aukštus rodiklius moteriškumo skalėje, o apie vyrus – vyriškumo skalėje. Be to, respondentai labiau demonstruoja geranorišką, o ne priešišką seksizmą ir pateikia apibendrintą moterų ir vyrų kaip androgeniškų asmenų įvaizdį. Buvo išsakytas didelis priešiškumas feminizmui, ypač tarp moterų.

Ukraina turi visus teisinius pagrindus lyčių lygybei. Taigi, intersekciniu požiūriu, tyrimo rezultatai išryškina kultūros ir socialinių normų įtaką lyties suvokimui ir lyčių stereotipams.

Darbo pabaigoje pateikiama pasiūlymų dėl mokymo programų, skirtų būsimiems globėjams ir socialiniams darbuotojams, gerinančių egalitarinius šeimos modelius ir moterų savarankiškumą.

Raktažodžiai: lyčių stereotipai, socialiniai vaidmenys, moteriškumas, vyriškumas, globa.

Received: 2022-08-19. Accepted: 2022-11-21.

Copyright © 2022 Alla Yaroshenko, Tetyana Semigina. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Ukraine, like many post-Soviet countries, had inherited the system of big child care institutions, in which hundreds of thousands of children were kept. This system was expensive and ineffective, as the state boarding schools were not able to ensure the positive socialization of children (Herczog, 2021; Kryvachuk, 2018).

In 2006, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine adopted the State Program for Overcoming Child Homelessness and Neglect for 2006–2010. In the same year, the Concept of the State Program of Reforming the System of Institutions for Orphans and Children Deprived of Parental Care was also approved. In 2017, the Government of Ukraine launched a reform of deinstitutionalization by adopting the National Strategy on Reform of Institutional Care System and Children Upbringing for 2017–2026.

So, one of the topical trends in the social work development in Ukraine is the deinstitutionalization of care for orphans and children left without parental care. The family care models are developed, including family-type children’s homes, foster families, adoption and others. It is envisioned that foster parents join the cohort of social work professionals and perform the role of parasocial workers: in addition to parenting, they themselves become providers of social services. The implementation of this approach assumes that the fulfillment of parental responsibilities is based on the social work ethical standards (IFSW, 2018), according to which professionals work to strengthen inclusive communities that respect diversity and challenge discrimination caused in particular by sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, etc.

To become a foster family, its members should undergo mandatory training (informal education at the social service with the follow-up registration in the state database of prospective parents). The training of candidates for foster parents may be focused on: (1) shaping the conscious helping behavior in relation to the child, which, like professional activity, is manifested in prosocial activity (Habashi, Graziano & Hoover, 2016); (2) enhancing foster parent competency in managing tough emotions and behaviors exhibited by traumatized children and youth (Leathers et al., 2012). Proper preparation, training, and support for foster parents impact on retention of children in new families (Randle et al., 2017; Solomon, Niec & Schoonover, 2017).

A number of studies have found that the success of the family care models largely depends on the motivations and values that inspire parents to place children, the socio-psychological characteristics of family members, as well as such gender aspects as the distribution of household workload, the involvement of men in performing housework and care for children (Antle et al., 2020; Chamberlain et al., 2008). Yet, the introduction in Ukraine of family forms of the upbringing of children left without parental care is accompanied by limited attention of academics to gender aspects of the functioning of family forms of upbringing, such as the gender competence of foster parents, the involvement of men in the process of caring for children, gender socialization of children, single-parent foster families, domestic violence in adoptive families, and gender roles, etc. (Yaroshenko, 2021).

Our research is aimed at identifying gender stereotypes and biases of prospective foster parents and providing recommendations for overcoming such stereotypes in the preparation training.

Gender stereotypes as a reflection of societal relations and inequality

For the purpose of our research, we use a few broad theoretical concepts: (1) gender stereotypes as consensual beliefs about the attributes of group members; (2) ambivalent sexism; (3) intersectionality of gender inequality.

We look at gender stereotypes through the lens of Social Role Theory. According to this theory, perceivers infer men’s and women’s traits as corresponding to their observed behaviors (Eagly & Wood, 2012; Gilbert, 1998; Wood & Eagly, 2012). Koenig and Eagly (2014) argue that since social roles organize most behaviors, groups’ stereotypical traits correspond to their members’ typical role occupancies and this division in gender stereotype content is based on observations (in media or daily life) of women and men in different roles; a division of labor stemming from women’s and men’s differing physical capabilities for child rearing contra labor requiring physical strength.

It was Bakan (1966) who introduced agency and communion as core dimensions of gender stereotype content and fundamental motivators of human behavior. Agency is associated with masculine characteristics and refers to traits such as independence, assertiveness and dominance. Whereas communion is supposed to be related to feminine characteristics and refers to traits such as relationship-oriented, emphatic and caring (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014). Cross-cultural research (Cuddy et al., 2015) has shown that the male stereotype aligns with the core cultural values: such that individuals from collectivist cultures rated men as more communal than women, whereas individuals from individualistic cultures rated men as more individualistic than women.

Bosak and co-authors (2018) define gender stereotypes as ‘ubiquitous’. Other research (Gustafsson Sendén et al., 2019) provides information that gender stereotypes are often internalized by men and women, and we, therefore, focus on both how men and women are seen by others and how they see themselves with respect to stereotyped attributes.

Psychological studies (Fiske & Taylor, 2013; Hentschel et al., 2018; Martínez-Marín & Martínez, 2019; Rivera & Paredez, 2014) demonstrate that stereotypes serve an adaptive function allowing people to categorize and simplify what they observe and to make predictions about others. At the same time, these biased beliefs may cause faulty assessments of people based on generalization from beliefs about a group that do not correspond to a person’s unique qualities, and diminishing self-assesment that impact opportunities for both men and women, inducing bias consequent decisions.

Gender stereotypes are regarded as dynamic; they represent the transforming attributes of women and men, and these beliefs about groups’ past, present, and future follow groups’ trajectories of actual role change (Diekman & Eagly, 2000). This dynamic reflects the current trend towards a more egalitarian relation with a family (Akkan, 2020).

Recent studies conducted in a different context, including Ukraine (Eagly at al., 2020; Frederick et al., 2007; Lopez-Zafra & Garcia-Retamero, 2012; Nikolic-Ristanovic, 2002; Sweeting et al., 2014), suggest that there has been a change in traditional gender stereotypes, yet research findings are inconsistent. For example, Diekman and Schneider (2010) explored the interactions between broad gender roles and specific roles. They pointed out that if women still do more of the household work that is associated with caregiving, or if they perform more communal tasks at work, they should not be perceived to decrease in communion. Similarly, if men do not work in professions that require communal skills, or enact family roles that are less associated with caregiving, men might not be perceived as acquiring communion only by taking more parental leave.

According to the theory of ambivalent sexism by Glik and Fisk (1996), attitudes towards gender groups are ambivalent, which is due to both the unequal distribution of power in favor of men and the mutual dependence of women and men in the realization of the reproductive function and the addition of one in performing various social roles. The theory suggests that ambivalent sexism is a multidimensional construct that encompasses benevolent and hostile sexism. Despite the positive color (subjectively positive nature of the evaluator’s feelings, his prosocial behavior, desire for closeness), benevolent sexism cannot be considered a positive phenomenon. The presence of this type of sexism indicates that a person supports traditional stereotyping and male dominance.

Contemporary sexism is also characterized by the fact that prejudice against women become more hidden and “subtle” and masked by a benevolent and protective attitude; persons who share sexist views deny the existence of discrimination against women and do not support their struggle for equal rights and women’s assistance policies (Swim et al., 1995).

The third concept that we used in our study is intersectionality, a framework for understanding how social identities overlap. It was suggested by Crenshaw (1991) and is defined as the interconnected nature of social categorisations such as race, class, and gender, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage. According to Hancock (2013), the intersectional perspective reminds us that we all have multiple facets of our identities and experiences, as well as social categories have developed their meaning in relation to each other.

Latest research (Goering & Shaw, 2017; Grooms, 2020 Sattler & Font, 2021) reveals the pivotal role of gender issues in foster care, as gender beliefs influence children’s placement and retention in families, the positive socialization of children and their further social trajectories. For example, Ashley (2014) noted that foster parents often reject LGBTQ+ children based on their sexual orientation or gender identity and remove them from their homes.

Social work is designed to counteract social inequalities in society, in particular, gender inequality, discrimination and stereotypes. As stated by Dominelli (2002), insufficient understanding of the societal structures and their impact on group beliefs leads to a simplified social work practice. So, in order to develop relevant support for foster parents, it is worth comprehending their gender stereotypes and correcting their negative perceptions.

Ukrainian Context

In Ukraine, the LawOn Ensuring Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men was adopted in 2005. This legislation aims to achieve the parity position of women and men in all spheres of life in society through the legal provision of equal rights and opportunities for women and men, the elimination of discrimination based on gender and the application special temporary measures for eliminating the imbalance between the opportunities of women and men to exercise equal rights granted to them by the Constitution and laws of Ukraine.

The adverse social transformations took place in post-socialist Ukraine, including activisation of women rights movement and the deterioration in women’s material status (Philips, 2008; Semigina, Yurochko & Stopоlyanska, 2022).

By now, the level of gender inequality and gender asymmetry remains high. This is confirmed by gender indicators and the research findings. Thus, in 2020, according to the Gender Gap Index, Ukraine ranked 59th out of 153 countries (World Economic Forum, 2021). UNFPA-Ukraine (2019) states that the majority of men believe that there is a division into «female» and «male» occupations. In addition to that, more than 40% of men in Ukraine believe that a woman should leave her paid work to spend more time with her family.

In Ukrainian families, the distribution of unpaid housework and child care remains unequal. In addition, “pro-family” movements, which use anti-gender slogans and oppose the policy of equality between women and men implemented by the state, have recently intensified their activities (Levchenko et al., 2013; Skoryk, 2017).

So, in Ukraine, like in some post-socialist states (Kelmendi & Jemini-Gashi, 2022; Oláh, Kotowska & Richter, 2018), women experience a double burden model through the expectations to fulfill traditional feminine gender roles within the family while simultaneously moving toward the conception of a new agentic role in society associated with independence and self-determination.

Research methodology

General background of research

The study was conducted at the Kyiv centre of social services for families, children and youth in 2018-2020. This municipal organization is responsible for the arrangement of mandatory trainings for those people who have expressed a will to become foster parents and meet the necessary requirements for the prospective foster parents (age, socio-economic status, etc.).

Candidates are selected by the municipal social centre, while the 8-week training programme is adopted by the Ministry of Ukraine of Family, Youth and Sports. This programme is an adapted version of the American program PRIDE (Polowy & Spring, 2009), developed in the early 1990s.

The content of the programme covers the topics of protection of children’s rights and interests, development of parental competences, distribution of childcare responsibilities, empowerment pedagogy. The training programme did not include any gender topics or sexual education aspects.

The research object of our work was the representations of gender stereotypes and biases of prospective foster parents participating in these mandatory trainings.

The hypothesis was put forward and tested that the sharing of social ideas about the qualities inherent in modern women and men, the presence of existential judgments depends on the social and reproductive status of the respondents.

Paricipants of research

Our research used a non-experimental design with different groups of prospective foster parents. Overall 5 training groups were questioned. The composition of these groups was random, the municipal centre invited to a particular group those people from the list of applicants who were able to undergo informal education in the given time slot. These traning for these groups were arranged in a sequential order in the offline format.

We surveyed all 83 participants of such groups. The criteria for inclusion were the following:

(1) expressed desire to become a foster parent;

(2) participation in a mandatory training for foster parents;

(3) consent to participate in the research.

In order to reduce the influence of psychological factors (such as previously received information, and the authority of trainers) and increase the objectivity of the results, the survey was conducted in groups with different composition of trainers, as well as with the involvement of participants who were at different stages of education (during the third, fourth, fifth, seventh, and eighth sessions out of eight).

Instruments and procedures

The exploration of stereotypes on femininity and masculinity traits was done by using the Sex-Role Inventory (Bem, 1974), while the assessment of ambivalent sexism in the attitudes toward women and men was done by using a short version of the methodology of Glick and Fiske (1996).

The Bem Sex-Role Inventory, BSRI (Bem, 1974) allows us to highlight respondents’ perceptions of the behavior patterns and character traits that they associate with “feminine” and “masculine”. The scoring of the BSRI by design does not treat the masculine and feminine items as clustering at opposite ends of a linear continuum; they are treated as measures of two independent scales. By comparing the feminine and masculine features contained in the descriptions of the generalized images of men and women, it is possible to assume the degree of influence of gender stereotypes on the judgments of the respondents.

Bem also found that some individuals have balanced levels of traits from both scales and described them as androgynous – a person having both high masculine and high feminine traits without employing a gender schema (circumstances dictate which trait – feminine or masculine – is exhibited by an androgynous person in a certain situation).

The BSRI is scored using a 60 trait personality test in which participants are asked to rate themselves on a 7 point scale (from ‘never/almost never true’ to ‘always/almost always true’.)

Glick and Fiske’s Ambivalent Sexism Inventory, ASI (Glick & Fisk, 1996; Rollero, Glick & Tartaglia, 2014) includes 22 items in two subscales – benevolent sexism (BS) and hostile sexism (HS). Each type of sexism is divided into three subscales, such as: benevolent sexism (maternalism/protective paternalism, complementary gender differentiation, heterosexual intimacy) and hostile sexism (abusive paternalism, compensatory gender differentiation, heterosexual hostility). All the items were rated on a six-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Data Analysis

Gender stereotypes are analyzed according to the following groups: masculinity-femininity; distribution of spheres of activity, work and directions of socialization of both sexes; social roles in the family, private and public spheres. The intersectionality perspective has been used to interpret the importance of multiple layers of vulnerabilities and their coexistence, including education, socioeconomic status, and their implications for gender perceptions.

Both used inventory instruments contain keys and procedures for processing data (Bem, 1974; Glick & Fisk, 1996; Rollero, Glick & Tartaglia, 2014). Mathematical processing of the results was carried out with the IBM SPSS Statistics Program.

Ethical issues

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Academy of Labour, Social Relations and Tourism (Ukraine). The protocol was approved by the Senate of this Academy.

All respondents declared their consent to participate in the research. A consent preamble was used with the administration of the survey through which subjects were informed of their right to refuse to complete these surveys, not to answer a specific question or questions on the surveys, or to discontinue participation at any time without penalty.

The study had no external funding. There is no conflict of interests or competing interests.

Results of the research

Characteristic of prospective foster parents

83 respondents participated in the study. Their age ranged from 24 to 68 years. Almost half (52%) of all participants belong to the age category from 35 to 44 years. Women constituted the majority of respondents (60%).

Approximately the same number of men and women received higher education (75%) and were officially employed (73%). The majority of respondents of both sexes are married (66% of women and 88% of men), and a third of them have children.

With regard to religion, 70% of the respondents classified themselves as Christians, of which the Orthodox (57%), Protestant (24%), and Catholic (5%) denominations were specified. A third of the respondents of the Christian faith indicated the specific churches they belong to, which may indicate their active involvement in religious practice. Among the respondents, there are those who do not consider themselves believers (14%), but recognize the influence of the dominant religious denomination in the country on their worldview.

Respondents’ views on femininity and masculinity traits

Findings from the survey of prospective foster parents show that in almost a third of cases, respondents’ answers about women contain high indicators on the femininity scale (30% of women and 33% of men), and about men – on the masculinity scale (26% of women and 30% of men). The group of respondents who most often attribute feminine qualities to women, and masculine qualities to men, turned out to be men aged 24 to 35. The choice of a set of androgynous qualities can also indicate the influence of traditional stereotypes.

Respondents of both sexes more often characterize women as attractive, ready to help, conscientious, friendly, tactful, artistic, but unpredictable and moody, and men as reliable and serious. Attractiveness, in the opinion of 94% of men, is a purely female trait, while half less share this idea about men.

The distribution of characteristics according to the scales of femininity and masculinity demonstrated that, in general, the study participants associate most feminine characteristics with women, and masculine characteristics with men. So, men are mostly presented as defending their own beliefs, defending their position, self-confident, ambitious, persistent, strong personalities, strong-willed, courageous, and serious, having an analytical mind, prone to leadership, willing to take risks. According to respondents, they are more domineering (55% of men and 63% of women) than aggressive (35% of men and 22% of women).

Respondents describe women as compliant, loyal, feminine, compassionate, attentive to the needs of others, sensitive, compassionate, warm-hearted, gentle, trusting, polite, those who love children and adhere to accepted norms of behavior.

To test the hypothesis that respondents’ perceptions of the qualities inherent in men and women will differ depending on the respondent’s social and reproductive status (by sex, age, education, and parental experience), we used the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test and H- Kruskal-Wallis test. As a result, the hypothesis was only partially confirmed: no statistically significant differences were found between the groups, except for the comparison of participants by age – it was found that the assessment of male qualities in the age cohort from 25 to 34 years was more masculine than in the group of participants aged 45–54 years old.

Study findings demonstrated that the vast majority of respondents characterize modern women and men as androgynous personalities (Table 1).

Table 1. Average indicators of the IS index* according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents (N=83)

|

№ |

Categories |

IS of women |

IS of men |

|||

|

Average |

N |

Average |

N |

|||

|

1 |

Sex |

Men |

,67 |

33 |

-,70 |

33 |

|

Women |

,61 |

50 |

-,62 |

50 |

||

|

2 |

Age |

Up to 25 |

1,04 |

1 |

-,93 |

1 |

|

25-34 |

,72 |

19 |

-,93 |

19 |

||

|

35-44 |

,61 |

43 |

-,64 |

43 |

||

|

45-54 |

,58 |

17 |

-,35 |

17 |

||

|

Over 55 |

,46 |

3 |

-,74 |

3 |

||

|

3 |

Marital status |

In marriage |

,66 |

62 |

-,63 |

62 |

|

Never been married |

,44 |

4 |

-,87 |

4 |

||

|

Widower/widow |

,58 |

6 |

-,63 |

6 |

||

|

Divorced |

,57 |

11 |

-,74 |

11 |

||

|

4 |

Having children |

Has |

,62 |

36 |

-,56 |

36 |

|

Has not |

,64 |

47 |

-,72 |

47 |

||

|

5 |

Education |

Secondary |

,57 |

20 |

-,53 |

20 |

|

Higher |

,65 |

63 |

-,69 |

63 |

||

|

6 |

Employment |

Officially employed |

,64 |

61 |

-,63 |

61 |

|

Self-employment |

,61 |

15 |

-,81 |

15 |

||

|

Maternal (parental) leave |

,46 |

1 |

-,35 |

1 |

||

|

Not employed |

,65 |

6 |

-,52 |

6 |

||

* The main IS index is calculated according to the formula: F = (sum of points for femininity): 20, M = (sum of points for masculinity): 20, IS = (F – M) * 2.322. The value of the obtained index is correlated with the following indicators: androgyny – an index ranging from -1 to +1; masculinity – the index is less than -1, bright expressiveness – less than -2.025; femininity – the index is more than +1, bright expressiveness – more than +2.025.

Differentiating Hostile and Benevolent Sexist Attitudes

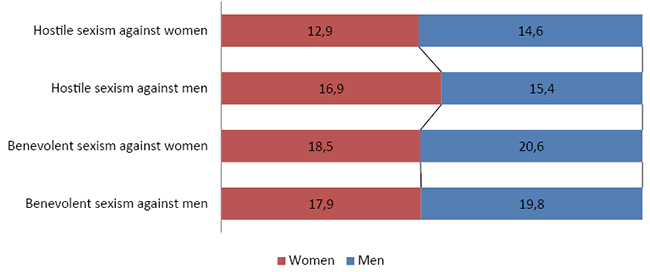

According to the results of our study, prospective foster parents demonstrate benevolent rather than hostile sexism to a greater extent. At the same time, the level of hostile and benevolent sexism is higher in men than in women (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Average indicators on scales of ambivalent sexism (based on Glick and Fiske’s Ambivalent Sexism Inventory with 22 items; N=83)

For both women and men, on a scale of benevolent sexism, heterosexual intimacy has proved to be the most important, as a desire for psychological and physiological intimacy with a person of the opposite sex. The analysis of separate questionnaires filled out by respondents who show a low level of ambivalent sexism (disagree with most of the judgments included in the questionnaire) showed that they give a positive response to the statement “Every man ought to have a woman whom he adores”.

There is also a difference in the attitude of men and women to certain aspects of the researched issue. Thus, male respondents more than female respondents support protective paternalism towards women, which is connected with the roles they perform as a mother, wife, and romantic object. The vast majority of men’s answers (94%) testify to the tendency of the respondents to agree and strongly with the fact that “Women should be cherished and protected by men” (and 88% of women as well).

Differences were also recorded in the views of the respondents on the complementary gender differentiation of benevolent sexism towards women and men. Thus, about half of the respondents support a point of view that reflects benevolent sexism towards women (when they are attributed positive qualities, such as «spiritual purity», high moral qualities, which are absent in men). However, the high rates of complementary gender differentiation of benevolent sexism for men indicate that, in general, respondents agree that men are more likely to take risks (82% of men and 82% of women) and to expose themselves to danger in order to protect others (85% of men and 78% women), and a quarter of the respondents answered the statement with full agreement.

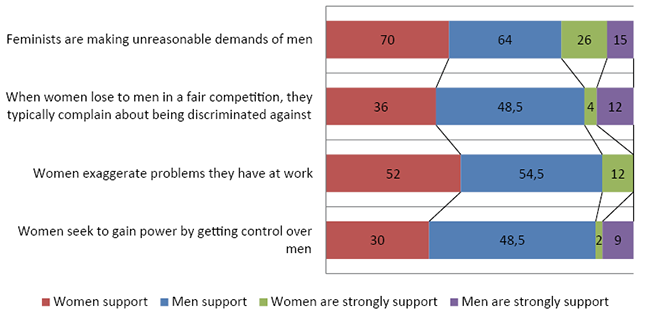

Respondents’ answers to questions designed to reveal hostile sexism against women were analyzed separately. These questions include an indication of discrimination, women’s rights and feminism. Among the respondents who approved those judgments, men predominate (Fig.2). The only exception is the statement that feminists make unjustified demands on men: it was supported by 70% of women, of whom 26% fully share this opinion. Only one of the participants of the training testified that she was familiar with the issues of feminism, leaving in the margins of the questionnaire next to the statement «Feminists are making unreasonable demands of men» the inscription «Feminism has many directions - it depends on which one.»

Figure 2. Respondents’ positive answers to judgements of the scale of hostile sexism towards women (N=83; %)

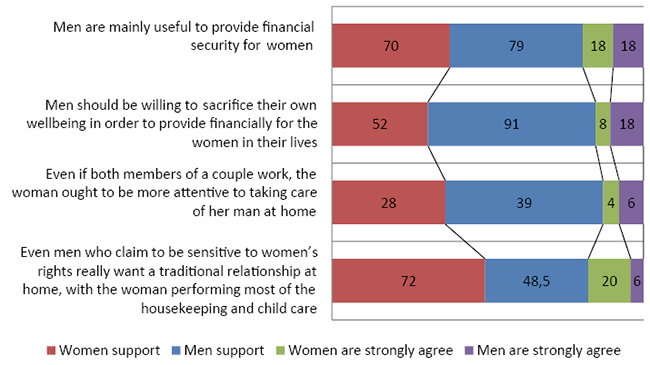

To find out the respondents’ attitudes to the distribution of roles in the family and private sphere, a few statements on the sexism scales regarding women and men were analysed separately. The results showed that the majority of respondents of both sexes (79% of men and 70% of women) support the statement that one of the main responsibilities of men is to provide financial support for women, and 91% of men surveyed believe that men should be ready for scarifying their own wellbeing (only half of the surveyed women agreed with this thesis). As for the distribution of housework, the respondents are not inclined to support the unfair distribution of the burden in family life, however, 72% of women tend to think (and 20% fully supported this opinion) that even men who are sensitive to issues of women’s rights, all at home, they strive for a traditional type of relationship, when a woman does housework and takes care of children (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Respondents’ positive responses to judgments regarding the distribution of social roles in the family and private sphere (N=83; %)

In sum, research findings indicate gender stereotypes and ambivalent sexist attitudes of the prospective foster families. Gender stereotype measures indicated that men are viewed as being less positively responsive but having more powerful traits than women who are considered attractive and caring. Respondents characterize modern women and men as androgynous personalities who are having both high masculine and high feminine traits exhibited by in a given situation. No statistically significant differences in gender stereotypes were found between the groups with exception of age: respondents over 45 assess male qualities as less masculine.

It is worth paying attention to the fact that respondents of both sexes place the responsibility of providing for the family financially on men, which indicates the acceptance by women and men of traditional social roles and expectations.

Prospective foster parents also demonstrate judgments of benevolent sexism and negative evaluations of feminists, indicating their acceptance of traditional social roles and expectations, as well as a low level of awareness of the women’s movement and prejudice against those who implement the ideas of gender equality.

Discussion

Consistent with other Ukrainian research on gender bias and gender roles (Frederick et al.; 2007; Levchenko et al., 2013; UNFPA-Ukraine, 2019), our study reveals the existence of gender distribution within a household. The inability to provide welfare for own family is considered by men as an inability to achieve the ideals of masculinity set by social norms. Also, an important observation was that respondents over 35 years of age with secondary education demonstrate the highest level of benevolent sexism towards women and men, which prompts us to pay special attention to this category of research participants.

Respondents (including women) demonstrate judgments of benevolent sexism and negative evaluations of feminists, indicating their acceptance of traditional social roles and expectations, as well as the low level of awareness of the women’s movement and prejudice against those who implement the ideas of gender equality.

The relative stability in gender-stereotypic personality characteristics was observed in our study and other researches on foster families (Volynets & Balim, 2009). We recorded the gender bias in the candidate’s vision of the family model and their acceptance of traditional social roles and expectations. The responses of the respondents testify to the existing split between agency and communication dimensions (Bakan, 1996; Cuddy et al, 2015) in gender stereotypes deeply rooted in the Ukrainian patriarchic culture (Skoryk, 2017).

The results of our study signal that the views of prospective foster parents combine, on the one hand, the sprouts of the egalitarian approach (seeing women and men as androgynous individuals), on the other hand, the sex-typed ideas about their qualities with traditional bipolar gender behavior.

With regard to these findings, the creation of a gender-sensitive environment during the training of candidates for surrogate parents is of particular importance, because, according to Bem (1993), it is not the individual who should be androgynous - rather, society should stop insisting on the universal functional importance of gender dichotomy.

The findings from our survey, as well as results of other studies (Chamberlain et al., 2008) indicate the need for the development and implementation of gender-sensitive interventions for foster parents that should be carried out by social workers.

Also, our data show that the concept of feminism is still stigmatized and causes fear among women themselves, which often makes it impossible to implement social interventions based on feminist paradigms enhancing women’s agency (Bakan, 1966; Abele & Wojciszke, 2014).

Building new interventions should be based on the Council of Europe (2019) statement that sexism manifests as unconscious biases that can be eliminated through awareness, training and education, and requires stronger measures, such as legislation.

At the current stage of societal development in Ukraine, it is possible to implement a transitory model of programmes containing elements of gender-conciliatory and transformational approaches. We agree with the views of researchers (Carr, 2003) who suggest that in order to change the perception of gender social roles it is necessary to rely on the principles of feminist and critical pedagogy, the combination of feminist frameworks with other approaches (resilience and practice based on strengths), the use of interdisciplinary connections, informal education.

The existing training programme for prospective foster families should be changed. The content of the program needs to be critically reconsidered through «gender lenses» and refined in order to spread the egalitarian model of the family and eradicate gender harmful norms.

Findings from our and other researches provide grounds for the following suggestions.

• The programme should encourage women’s agency (Abele & Wojciszke, 2014), and take into account the gender awareness-raising methods that help to facilitate the exchange of ideas, increase the level of awareness and general sensitivity to gender (in)equality, improve mutual understanding and develop competencies and skills necessary for social change (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2016).

• In the course of training, it is worth to use existing discriminatory statements/behavior of learners as learning situations (when appropriate); use diagnostic assessment to identify prior knowledge instead of making assumptions; emphasize and balance with additional information materials that have gender discriminatory features.

• Given the fact that in the online environment there is no clear, predictable gender difference, “typically male/female” biases also do not find a place, it is worth to conduct the gender competence topics online. In offline discussions, participants may experience certain problems when discussing topics related to sexuality. Online learning overcomes gender bias by allowing learners to remain anonymous and the instructor to focus on comments and feedback while avoiding gender bias. Anonymity allows listeners to interact with content that is often not too “comfortable” for them (such as sexual orientation, gender identity, etc.). Other researchers (, 2010) support using the online training format for sensitive issues.

Limitations and future research

The first limitation of the study is the sampling procedure. The participants were recruited through convenience sampling; thus, the results are not representative of the general population. Secondly, our findings are limited by mono-method and self-reporting biases. We aware that people may express more egalitarian attitudes than their subsequent behavior would suggest. So, findings might underestimate the level of benevolent or otherwise sexism in subsequent relationships within the foster family.

Future studies should focus on diverse data collection methods, including focus group discussions, interviews, or vignettes, providing a broader and more nuanced understanding of how gender roles evolve. Additional research is needed on how the experience of fostering contributes to socially constructed feminine gender roles, as well as the adaptive function of stereotypes in the lives of foster families.

Conclusions

Perception of social roles is important for the retention of children in foster care families and for upbringing them.

The research conducted among prospective foster parents at the Kyiv centre of social services for families, children and youth revealed the existence of gender stereotypes in the candidates’ vision of the family model, their acceptance of traditional social roles and expectations.

Respondents of both sexes more often characterize women as attractive, ready to help, conscientious, friendly, tactful, artistic, but unpredictable and moody, and men as reliable and serious.

Respondents of both sexes also demonstrate benevolent sexism rather than hostile sexism. It was found that the majority of respondents need a close relationship with a person of the opposite sex, and men demonstrate protective paternalism in relation to women.

The results of the study indicate the need for the development and implementation of gender-sensitive interventions that will be carried out by social workers, as well as the need to change the focus of the foster parent training program.

References

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Communal and agentic content in social cognition: a dual perspective model. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol., 50, 195–255.

Akkan, B. (2020). An egalitarian politics of care: young female carers and the intersectional inequalities of gender, class and age. Feminist Theory, 21(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700119850025

Antle, B.F., Barbee, A.P., Sar, B.K., Sullivan, D.J. & Tarter, K. (2020). Exploring Relational and Parental Factors for Permanency Outcomes of Children in Care. Families in Society, 101(2), 132–147. doi:10.1177/1044389419881280

Ashley, B. (2014). The challenge of LGBT youth in foster care. The Forum, 14(4), 47–67

Bakan, D. (1966). The Duality of Human Existence: An Essay on Psychology and Religion. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Bem, S. L. (1993). The lenses of gender: transforming the debate on sexual inequality. Yale University Press.

Bosak, J., Eagly, A., Diekman, A. & Sczesny, S. (2018). Women and Men of the Past, Present, and Future: Evidence of Dynamic Gender Stereotypes in Ghana. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(1), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022022117738750

Carr, E. S. (2003). Rethinking empowerment theory using a feminist lens: The importance of process. Affilia, 18(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109902239092

Chamberlain, P., Price, J. M., Leve, L. D., Laurent, H., Landsverk, J. A. & Reid, J. B. (2008). Prevention of behavior problems for children in foster care: Outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science, 9, 17–27.

Council of Europe (2019). Recommendation on Preventing and Combating Sexism. https://www.coe.int/en/web/gender-matters/recommendation-on-preventing-and-combating-sexism

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299.

Cuddy, A. et al. (2015). Men as cultural ideals: cultural values moderate gender stereotype content. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., 109, 622–635.

Diekman, A. B. & Eagly, A. H. (2000). Stereotypes as dynamic constructs: Women and men of the past, present, and future. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1171–1188. doi:10.1177/0146167200262001

Diekman, A. B., & Schneider, M. C. (2010). A Social Role Theory Perspective on Gender Gaps in Political Attitudes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(4), 486–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01598.x

Dominelli, L. (2002). Feminist social work theory and practice. Palgrave.

Eagly, A. H. & Wood, W. (2012). Social role theory. In: van Lange, P., Kruglanski, A., Higgins, E. T. (Eds.), Handbook of theories in social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 458–476). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Eagly, A.H., Nater, C., Miller, D.I., et al. (2020). Gender stereotypes have changed: a cross-temporal meta-analysis of US public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. Am Psychol., 75(3), 301–315.

European Institute for Gender Equality (2016). Effective gender equality training: Analysing the preconditions and success factors: main findings. https://eige.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/mh0415347enn.pdf

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2013). Social Cognition: From Brains to Culture. London: Sage.

Frederick, D. A., Buchanan, G. M., Sadehgi-Azar, L., Peplau, L. A., Haselton, M. G., Berezovskaya, A. (2007). Desiring the muscular ideal: Men’s body satisfaction in the United States, Ukraine, and Ghana. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 8, 103–117.

Gilbert, D. T. (1998). Ordinary personology. In: Gilbert, D. T., Fiske, S. T., Lindzey, G. (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 89–150). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Goering, E. S. & Shaw, T. V. (2017). Foster care reentry: A survival analysis assessing differences across permanency type. Child Abuse & Neglect, 68, 36–43.

Grooms, J. (2020). No Home and No Acceptance: Exploring the Intersectionality of Sexual/Gender Identities (LGBTQ) and Race in the Foster Care System. The Review of Black Political Economy, 47(2), 177–193.

Gustafsson Sendén, M., Klysing, A., Lindqvist, A. & Renström, E.A .(2019). The (Not So) Changing Man: Dynamic Gender Stereotypes in Sweden. Front. Psychol., 10:37. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00037

Habashi, M. M., Graziano, W. G., & Hoover, A. E. (2016). Searching for the prosocial personality: A big five approach to linking personality and prosocial behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(9), 1177–1192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216652859

Hancock, A. M. (2013). Empirical intersectionality: A tale of two approaches. UC Irvine Law Review, 3(2), 259–296.

Hentschel T, Heilman ME and Peus CV (2019) The Multiple Dimensions of Gender Stereotypes: A Current Look at Men’s and Women’s Characterizations of Others and Themselves. Front. Psychol. 10, 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00011

Hentschel, T., Braun, S., Peus, C. & Frey, D. (2018). The communalitybonus effect for male transformational leaders – leadership style, gender, and promotability. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol., 27, 112–125. doi: 10.1080/ 1359432X.2017.1402759

Herczog, M. (2021). Deinstitualization efforts of the child care system in Europe – Transition from institutional to family- and community-based services. In: K. Kufeldt, B. Fallon, & B. McKenzie (Eds.). Protecting children: Theoretical and practical aspects (pp. 370–386). CSP Books.

IFSW (2018). Global Social Work Statement of Ethical Principles. https://www.ifsw.org/global-social-work-statement-of-ethical-principles

Kelmendi, K. & Jemini-Gashi, L. (2022). An Exploratory Study of Gender Role Stress and Psychological Distress of Women in Kosovo. Women’s Health. doi:10.1177/17455057221097823

Koenig, A. M. & Eagly, A. H. (2014). Evidence for the social role theory of stereotype content: Observations of groups’ roles shape stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107, 371–392. doi:10.1037/a0037215

Kryvachuk, L. (2018). Transformation of Social Services in Ukraine: the Deinstitutionalization and Reform of the Institutional Care System for Children. Labor et Educatio, 6, 129–148. https://doi.org/10.4467/25439561LE.18.010.10237

Leathers, S. J., Spielfogel, J. E., Gleeson, J. P., & Rolock, N. (2012). Behavior problems, foster home integration, and evidence-based behavioral interventions: What predicts adoption of foster children?. Children and youth services review, 34(5), 891–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.017

, M. (2010). The Use of an Online Diversity Forum to Facilitate Social Work Students’ Dialogue on Sensitive Issues: A Quasi-Experimental Design. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 30:3, 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2010.499066

Levchenko, K. et al. (2013). Antygender v Ukrayini»: ekspertne opytuvannya [“Antigender in Ukraine”: expert survey]. Gendernyy zhurnal «YA», 3(34): 29–32 (in Ukrainian).

Lopez-Zafra, E. & Garcia-Retamero, R. (2012). Do gender stereotypes change? The dynamic of gender stereotypes in Spain. The Journal of Gender Studies, 21, 169–183. doi:10.1080/09589236.2012.661580

Martínez-Marín, M.D. & Martínez, C. (2019). Negative and Positive Attributes of Gender Stereotypes and Gender Self-Attributions: A Study with Spanish Adolescents. Child Ind Res., 12, 1043–1063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9569-9

Nikolic-Ristanovic, V. (2002). Social change, gender and violence: post-communist and war affected societies. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer Science+Business Media.

Oláh, L.S., Kotowska, I.E. & Richter, R. (2018). The new roles of men and women and implications for families and societies. In: Doblhammer, G, Gumà, J (eds), A demographic perspective on gender, family and health in Europe (pp. 41–64).Cham: Springer.

Philips, S. (2008). Women’s Social Activism in the New Ukraine: Development and the Politics of Differentiation. Indiana University Press.

Polowy, M.E., & Spring, B. (Eds.). (2009). PRIDE book. Illinois: Illinois department of children and family services.

Randle, M., Ernst, D., Leisch, F. & Dolnicar, S. (2017). What makes foster carers think about quitting? Recommendations for improved retention of foster carers. Child & Family Social Work, 22, 1175–1186.

Rivera, L.M. & Paredez, S.M.(2014). Stereotypes can “get under the skin”: testing a self-stereotyping and psychological resource model of overweight and obesity. J Soc Issues ; 70(2), 226–240.

Rollero, S., Glick, P. & Tartaglia, S.(2014). Psychometric properties of short versions of the ambivalent sexism inventory and ambivalence toward men inventory. TPM, 21(2). https://bit.ly/3A3fkTI

Sattler, K. M. P., & Font, S. A. (2021). Predictors of Adoption and Guardianship Dissolution: The Role of Race, Age, and Gender Among Children in Foster Care. Child Maltreatment, 26(2), 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559520952171

Semigina, T., Yurochko, T. & Stopоlyanska, Y. (2022). ‘Everyone is on their own and nobody needs us’: women ageing with HIV in Ukraine. In: M. Henrickson, C. Charles, S. Ganesh, S. Giwa, D. Kwok, & T. Semigina, T. (Eds.), HIV, sex, and sexuality in later life (pp. 46–63). Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Skoryk, M., ed. (2017). Alternative report on Ukraine’s implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (VIII periodic report). Kyiv: Kyiv Institute of Gender Studies.

Solomon, D. T., Niec, L. N. & Schoonover, C. E. (2017). The impact of foster parent training on parenting skills and child disruptive behavior: A meta-analysis. Child Maltreatment, 22, 3–13.

Sweeting, H., Bhaskar, A., Benzeval, M., et al. (2014). Changing gender roles and attitudes and their implications for well-being around the new millennium. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol., 49(5), 791–809.

Swim J., Aikin, K., Hal,l W., & Hunter, B. (1995). Sexism and racism: oldfashioned and modern prejudices. Journal of personality and social psychology, 68(2), 199–214.

UNFPA-Ukraine (2019). Gender Equality and Response to Domestic Violence in the Private Sector of Ukraine: Call for Action. https://ukraine.unfpa.org/en/BADV2019eng

Volynets, L. & Balim, L. (2009). Adoption: realities and trends, results of sociological research. Kyiv: Holt International.

Wood, W. & Eagly, A. H. (2012). Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. In: Olson, J. M., Zanna, M. P. (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 46, pp. 55–123). London: Elsevier.

World Economic Forum (2021). Global Gender Gap Report 2020. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf

Yaroshenko, A. A. (2021). The formation of gender competence of social workers in the context of the development of family forms of raising orphans and children deprived of parental care (PhD dissertation, specialty 231 “Social Work”). Kyiv: Academy of Labor, Social Relations and Tourism.