Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika ISSN 1648-2425 eISSN 2345-0266

2023, vol. 27, pp. 182–199 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2023.27.11

Challenges and Dilemmas Faced by Labor Market Integration Support Providers in Portugal

Ana Luisa Martinho

Polytechnic University of Porto / CEOS.PPORTO & A3S Association

anamartinho@iscap.ipp.pt

Abstract. This research delves into the challenges and dilemmas faced by both professionals and people in vulnerable situations in the process of social and professional inclusion. Grounded in a theoretical framework that underscores the persistent rates of labor exclusion among specific social groups and the fragmented social policies in Portugal, the study aims to understand the structural framework and practices in this field.

This research adopts a qualitative approach to investigate the challenges of the social and professional integration of people in vulnerable situations. For this purpose, the study employs nine in-depth case studies within the context of social economy organizations in Portugal.

The findings illuminate the complex challenges faced by professionals supporting people with complex needs, including the nonlinearity and multifaceted nature of the inclusion process, resource inadequacies, the need for specialized training and guidance, and a labor market unaligned with the needs and abilities of the clients. The study underscores the necessity for a more holistic, supportive, and inclusive approach to address the intricate dynamics of social and professional integration for people in vulnerable situations.

Keywords: Social Economy Organizations; Inclusive and Decent Work; Individualized Support; Work Integration Social Enterprises; Social and Employment Inclusion

Received: 2023-12-22. Accepted: 2024-02-29.

Copyright © 2023 Ana Luisa Martinho. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

In today’s contemporary Welfare States, the quest for equality and equitable access to the labor market has gained prominence as a fundamental public responsibility. Recognizing the right to work as a cornerstone of a dignified existence, efforts have been directed towards supporting the active population in their journey towards professional integration. In this context, ensuring that individuals in vulnerable situations receive the same opportunities is imperative. In Portugal, studies on the work done by those professionals are incipient. What’s more, the field of social and labor integration for these people is poorly structured when compared to other countries, particularly at European level, such as in other European countries (Estivill et al., 1997; Defourny et al., 1998; Lipietz, 2001; Lima & Trombert, 2017; Defourny & Nyssens, 2021). In fact, in Portugal, we can state that the field of labor market integration for people in vulnerable situations is poorly structured, if we take into account the scarcity of: i) legislative contributions and the ineffectiveness of specific social policies; ii) specific training for support work in unemployment, underemployment and precariousness for specific population groups; iii) studies on the work of supporting people in situations of vulnerability; iv) methodological guidelines for the work of professionals when it comes to support people in situations of vulnerability. That is why this paper addresses the challenges encountered by labor market integration support providers. These professionals play a crucial role in supporting individuals facing vulnerabilities yet face inadequate recognition and training within the Portuguese labor market landscape.

1. Advancing Inclusive and Decent Work through Labor Market Integration Support Providers

1.1. The importance of inclusive and decent work for all

The state of the art establishes a connection between the importance of work activity in social inclusion processes, in a work-centric society, and the recognition of the right to decent work and corresponding social protection in modern Welfare State models. Despite social protection being considered as a safeguard within this organizational model, the persistent rates of social exclusion faced by vulnerable social groups raise questions.

Research has highlighted a noticeable shift in traditional employment patterns, exemplified by the crisis of full-time, stable, and white male employment (Lorey, 2015; Sarfati & Bonoli, 2002). This transformation reflects the changing nature of work, characterized by increased flexibility and insecurity. Consequently, these shifts in the labor market have significant implications for the employability of various population segments, particularly those considered vulnerable. It is important to clarify that the concept of social vulnerability is polysemic and has varied according to different spatio-temporal contexts. The study and delimitation of the concept of vulnerability are closely linked to the sociological approach of concepts such as social exclusion and poverty. However, for the purpose of this paper, we will only focus on a broad definition of the concept linked to the issue of disadvantage in accessing and succeeding in the labor market. As a complex phenomenon, vulnerability can affect social groups that, due to their exclusion/marginalization, do not benefit from fundamental human rights. It is a concept used in various scientific disciplines (Alwang et al., 2001) that cannot be reduced to institutional and administrative categorizations. Vulnerability can be a condition associated with individuals who are in the labor market and yet subject to precarious work and low wages. Despite this, individuals in professional occupations have a lower risk of social vulnerability (Junior et al., 2021). Thus, most marginalized groups, namely vis-à-vis the labor market, are categorized as migrants, people with disabilities, NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training), ex-prisoners, women, etc. These are the main target group of the labor market inclusion concerns of Employment Policies.

A prominent issue in the labor market is the prevalence of structural unemployment, which disproportionately affects vulnerable groups, leading to significant barriers to accessing gainful employment. Examining the causes and consequences of structural unemployment is essential for designing targeted policy interventions to create more inclusive employment opportunities. The notion of employment trajectories has gained attention in recent research. “Carousel employment trajectories” (Diogo, 2007) illustrate the precariousness and instability experienced by some individuals in their work journeys. Additionally, “life mazes” and “yo-yo trajectories” (Machado Pais, 2001) exemplify complex life paths influenced by fluctuating employment opportunities. Understanding these diverse trajectories can aid in designing more tailored support systems for people with complex needs.

Active employment policies have evolved over time to address the challenges of unemployment and vulnerability, emphasizing insertion/integration (Hespanha, 2008) and promoting a right-duty approach to access employment opportunities. Measures have been implemented to remove obstacles hindering employability and foster greater employer involvement. The role of public institutional actors and the social economy in facilitating professional integration for people in a vulnerable situation is a crucial aspect of these policies. The right to work is fundamentally crucial in guaranteeing individual existence. In a wage-earning (Castel, 2003) and work-centric society employment holds centrality, it shapes daily life, provides visibility, social identity, and recognition/integration (Williams et al., 2016; Ramos, 2000; Barel, 1990; Gorz, 1988).

It is also important to establish a connection between the concept of inclusive work and the argument for diversity in Human Resources in the labor market, recognized in the approaches of Strategic Diversity Management and Diversity and Inclusion Management. Since the 1990s, with the pioneering studies of Cox and Blake (1991), the increasing diversity of labor markets has spurred the evolution of diversity management and its impact on organizational competitiveness. Indeed, there is already considerable scientific literature on the benefits of strategic diversity management. Chidiac (2020) presents a wide range of studies demonstrating tangible outcomes such as improved organizational performance, heightened competitiveness, reduced turnover, and intangible benefits like enhancing the working environment and fostering better relationships between workers and employers/management, as well as talent retention. It therefore seems obvious that decent work, inclusivity, and nondiscrimination are vital in advancing towards Diversity and Inclusion Management. However, despite the well-documented advantages, the active engagement of employers in labor market policies and practices for individuals in vulnerable situations encounters challenges of applicability and resistance within the business community (van Berkel et al., 2017).

As this is a complex responsibility, several players are called upon to take an active role in this endeavor. First and foremost, public institutions, more recently employers, but always, by their very nature, social economy organizations. In Portugal, these organizations play a particularly important role in the implementation of social and employment public policies. In fact, since the establishment of the welfare state following the 1974 revolution, special statutes have been created for social economy organizations, giving them a central place as providers of social services for the state.

1.2. The context: Social Economy Organizations in Portugal

As a movement acknowledged as hybrid and “plural,” in which we are all, in a certain way, integrated (Mintzberg, 2015), Social economy organizations are often claimed to play a central role in the fight against discrimination and for inclusion. Over the years, these organizations have shown results, namely as: an alternative work model in digital platforms (Meira & Fernandes, 2021), gender equality in management bodies (CASES, 2021), and high levels of employee satisfaction and retention (Marques & Veloso, 2020; Renard & Snelgar, 2017).

At the European level, the institutionalization of the concept occurred, among other reasons, through the regulation of the social economy in different EU countries, with successive legislation since the 2010s, in the form of framework laws.1 Following the example set internationally, Social Economy in Portugal has also shown dynamism and renewal. In a country with a tradition of welfare and charity associated with the social action of the Catholic Church, Portugal saw its first organizations emerged in the 15th century. However, it was necessary to wait until the 21st century for there to be a legal recognition of the sector as a whole and not only separate legislation for instance for associations or cooperatives. Indeed, the 21st century marks a turning point in the recognition of social economy in Portugal, culminating in its legal recognition with the Law of Bases of the Social Economy (LBES) in 2013 (Law 30/2013, of May 8th). Portugal thus becomes the second country in Europe to approve an LBES (Meira, 2013).

It is important to highlight that in the Satellite Account for the Social Economy, it is not possible to identify organizations dedicated to the social and professional integration of people in a vulnerable situation. Indeed, this accounting follows the International Classification of Non-Profit Organizations and Third Sector (ICNPO/TS), which recognizes 12 types of activities. From among the 12 areas of activity in the classification, we highlight the area of Social Services, for which the following examples of activity are mentioned: “(social) support services for children, young people, the elderly, people with disabilities and families, temporary shelters, emergency and rescue services, support for refugees, training activities or vocational counselling, among others” (INE/CASES, 2023, p. 82).

The social economy in Portugal has shown expansionist signs and strong public recognition. According to the latest Satellite Account for the Social Economy published in 2023, about data from 2020, there are 73 851 entities in Portugal. Since 2010, the number of units within this sector has grown by approximately 33% (INE, 2023).

In 2020, the Gross Value Added of the Social Economy represented 3.2% of the national economy’s Gross Value Added, slightly increasing (0.4%) compared to 2019. This evolution was contrary to what was observed in the national economy, where the GVA decreased by 5.8% in the first year when the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were felt.

Between 2019 and 2020, social economy organizations accounted for 5.1% and 5.2% of the total employment and 5.8% and 5.9% of the paid employment in the national economy, respectively. According to data from the latest Social Economy Satellite Account (2023), in 2020 Social Services was the second most important area of activity in terms of Gross Value Added, employment and wages, closely following Health. In fact, social services generated 24.9 per cent of GVA, 29.9 per cent of paid employment and 26.7 per cent of total salaries in the social economy (INE, 2023).

1.3. Challenges for Labor market integration support providers

Although there is a great recognition and discourse for the inclusive a just transition, but also for the role of social economy organizations, in Portugal there is a paradox. Indeed, we can affirm for weak political practices. Namely a lack of training for social and professional support providers, and because of it, a lack of recognition of this occupation. Work support providers play a central role in supporting individuals, specifically in the methodologies selected to address the specific and complex needs of each client. This specialized role of professionals, focusing on supporting people in vulnerable situations, has been recognized in several countries (Lima & Trombert, 2017; Castra, 2003), with corresponding specialized training opportunities for their professionalization. However, this trend has not been observed in Portugal (Martinho & Gomes, 2021). The lack of recognition for such a professional profile results in both undefined roles and responsibilities, as well as the absence of specific initial qualifications or structured training programs tailored to these professionals (Associação A3S, 2016).

M any employment policies are focused on giving financial incentives to companies and/or give experiences for jobseekers in the labor market, as trainees. They are not actually workers, so they do not have social protection. Our study places particular emphasis on international typologies of social economy organizations, such as WISE (Work Integration Social Enterprise), that serve as productive organizations with a mission of socio-professional integration (Cooney et al., 2023). Portugal has a unique situation in the European panorama, because a law for WISEs was in place (Portaria nº 348-A/98, 18 de junho) from 1998 to 2015. In fact, during the economic crisis (2008–2013), with austerity policies, this law was revoked and has not been reinstated to this day (Quintão et al., 2018). In the current global paradigm of clear common direction towards the development of more active social policies, and despite some delays in Southern countries (Bonoli, 2013), it is also possible to observe in Portugal the “resumption of a social policy guided by the principles of investment rather than solely passive protection and minimums” (Capucha, 2019, p. 36). Despite being less structured compared to other European contexts, the Portuguese work integration field has shown greater attention to the issue of labor market integration for people with complex needs. Following the international trend, there have been signs of expansion on this topic, with policies focused on the supply side, exemplified by Law No. 4/2019, January 10, which represents a paradigmatic approach to this matter.

Namely because the inexistence of specific and integrated policies, and of an umbrella organizations that represent those de facto WISE, there is a lack of a formal field of labor market integration support. This informal way of existing, potentially make the providers’ job even more difficult, namely in terms of lack of resources. Historically, the inadequate resources for street level workers have been repeatedly studied. In the 1980s Lipsky (1969; 1980) already analyzed the uncertainty of front-line workers, namely because of the complexity of the subject matter – people. On the dilemmas that the author reflected on is the difficulty on balancing the specific needs of each client with the structural and bureaucratic system that providers must respond to. Labor market integration support providers are, above all, human service workers (Hasenfeld, 1992). In addition, historically, those professional functions are often pointed out as inadequate in terms of resources to provide an appropriate job. This specificity of work implies commitment and dedication, because it has implication on the quality of life of supported people (Hasenfeld, 1992).

Like other European countries, such as France or Slovenia (Greer et al., 2018), the social economy in Portugal, which is dedicated to social services, is characterized by its holistic response to the communities in which it operates, often acting as an intermediary in the operationalization of public policies for which the state is responsible. Within the set of social responses provided by the social economy in terms of social work, these organizations also offer responses in terms of support for employability. In this context, the labor market integration support provider faced the dilemma of being between the policies measure, acting as a public sector actor sometimes as “charitable and police burden” (Hespanha, 2008, p. 6) of care work and the well-being of their client. Having the power to give or take away social support, may also pose a challenge regarding the discretionary power identified by several authors as Lipsky (1980) and Hespanha (2008). Discretionary power refers to the possibility that, when faced with a situation involving the allocation of social support, the professional may choose from a range of possible behaviors the one that seems best suited to satisfying the public policy they represent. This leads to individual choices and, probably, judgment (Lipsky, 1980; Hespanha, 2008).

The high responsibility and ethics define the practice of labor market integration support providers: “the well-being of the workers is enhanced by investing in the well-being of the client and vice-versa – such mutual dependence – foster mutual respect and trust” (Hasenfeld, 1992, p. 21). Individualized social support is one of the pillars of access to employment and (re)integration (Ebersold, 2001; Castra, 2003; Paul, 2020). However, the quest for individualized responses to the specific needs of each person being supported encounters various resistances in the practice of socio-professional support. The rigidity of available public policy devices already conditions the pursuit of individualization (Castra, 2003), in addition to the complexity of the issues faced by each supported person, has a multi-causal dimension in their vulnerable situations.

The positive consequences of projectification – understood as a shift paradigm in order to improve the new product development process – has been extensively studied. The negative consequences, although more recent, have already been recognized, particularly in terms of precariousness. Namely, this was studied by Greer et al. (2018) in the in Slovenian and French social services, particularly the precariousness towards workers. A recent report from the social economy organization, Jesuit Refugee Service Portugal, aptly underscores the challenges associated with short-term project engagements. Furthermore, the organization contends that Portugal’s exclusive reliance on EU funds poses a hindrance to their efforts in supporting migrants and refugees. The insufficient public investment in establishing more robust and enduring solutions for sustained intervention and the stability of social workers is noted. Consequently, these organizations are frequently compelled to downsize, resulting in the loss of valuable expertise within their teams (JRS, 2023).

2. Methodological Approach

Starting from the theoretical framework, we formulated the analytical model and explicitly chose a qualitative research approach. In a country marked by persistent rates of labor exclusion among certain social groups and with vague and uncoordinated social policies promoting their integration, the study of labor market support providers practices is crucial. The research is grounded in the two general research questions mentioned above, namely: How is the field of social and professional integration of vulnerable individuals structured in Portugal? What are the practices developed by professionals in social economy organizations? To address these questions, our research design rotates around a central methodological approach – nine Portuguese case studies. Those were conducted in the context of Portuguese social economy organizations that provide support and counselling to people in vulnerable situations with labor inclusion goals. As a research method, case studies have been utilized by various disciplines in the social sciences, enabling the investigator “to retain the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life events” (Yin, 2009, p. 4).

We conducted nine case studies, focused on the work carried out by different professionals (Human Resources managers, Social Integration Income technicians, vocational and/or employment counsellors, job coaches) involved in the social and labor counselling and support of individuals who are disconnected from the labor market. These professionals work within social economy organizations situated in the Metropolitan Area of Porto-Portugal. We chose to gather the data through several interviews with a total of 34 different professionals, which we later transcribed. Additionally, we conducted observation work, particularly during visits to the case study sites and participation in work meetings of different teams. Official documents, such as the Organization’s website, its statutes, and documents systematizing the activities carried out, were also consulted, in addition to documentary analysis of the work tools used by the interviewees in their social and labor integration support work. The fieldwork for data collection of the case studies took place between March 2019 and May 2021.

A case study protocol was drawn up, closely following the guidelines of Yin (2009), which included all the inherent methodological procedures, namely: the identification of the reference person, the research objectives and questions, the visit/displacement to the case study, the interviews, the observation, the request and consultation of relevant documentation, the report and informed consent. In this, the guarantee of professional secrecy and anonymity in the referencing of the case study is explained, using coding for this purpose.

Regarding the sample composition, given that this study is primarily qualitative and exploratory in nature, we opted for a convenience sample. This sample followed criteria of heterogeneity in the presented practices, as well as representing the practices of social and professional integration work with people in a vulnerable situation. Indeed, the case studies were selected based on prior knowledge and the researcher’s proximity and/or were recommended by a key informant, following a snowball sampling logic. Access to the case studies was gained either by contacting the person in charge of the organization by telephone, or by the person who would become the point of reference throughout the study, i.e. the professional in charge/coordinator of accompanying and guiding people in situations of vulnerability.

Whenever possible, during the first face-to-face contact, a visit was made to the premises with an informal presentation of the work carried out and a subsequent entry in the field diary. In conjunction with this visit, the first exploratory interview with the reference person was carried out using an open-ended script, so as not to condition the presentation of the case a priori. In a constant quest to adapt the researcher to the specific field being analyzed, which is typical of the qualitative paradigm, on the one hand, and to the characteristics of the work teams, on the other, we carried out some collective interviews (Beta, Omega, Iota, Zeta), in response to a suggestion from the interviewees themselves.

Due to the diversity of cases, both in terms of their size and the work carried out, we observed and simulated the work carried out. In each case study,2 a report summarizing the information gathered was sent to the reference person for validation. At the time of this validation, some interviewees added relevant information to better understand the case and all validated the reports.

In a triangulation of secondary data collected through documentary analysis and primary data collected through the case studies, the data was analyzed using the content analysis. Thus, due to the uniqueness of each case study, the vertical content analysis technique was used. This was followed by a phase of horizontal content analysis by categories of analysis. In this paper, we present the results of this analysis in relation to the macro-category of analysis: challenges and dilemmas faced by labor market integration support providers.

3. The nine case studies

3.1. General scope

If we consider the general profile of the case studies, we find that seven of them were established within social economy organizations that already had more widespread interventions and later developed specific responses in the area of employability. In fact, only Alfa and Lambda existed before the hosting entity and were founded as projects.

The hosting entities of the case studies were established between 1926 (Alfa) and 2008 (Lambda), varying in size in terms of paid workers, ranging from none (in addition to those integrated into Alfa) to over 100 (Omega). Mostly formed as associative entities (except for Lambda, which was constituted as a cooperative).

Except for Alfa and Iota, which are exclusively dedicated to supporting individuals in vulnerable situations in their professional integration, the other cases are part of more comprehensive responses for these individuals and/or other target-groups. Consequently, the funding used by the support teams to address employability issues is not specific. Instead, it comes from more generic funding for social support and/or intervention to combat social exclusion, such as the protocols of Social Integration Income, Local Development and Social Cohesion Contracts, or Program for the Support of People with Mental Disorders. In these cases, the hosting entities of the studied cases develop multiservice responses aimed at various target groups, from children and youth to the elderly. However, the hosting associations of Alfa, Beta, and Kapa have specialized in interventions for people with disabilities, particularly those with experience of mental illness.

Regarding the general profile of the clients of the cases, Table 1 represents a simple classification of the main target groups identified based on the legal status of the hosting entity of each case. Six of the cases primarily target unemployed individuals, four focus on people with disabilities (including mental illnesses), and one is directed towards individuals with addictive behavior.

Table 1. Main target groups of the case study

|

|

Main target-groups - clients |

|

Alfa |

People with disabilities |

|

Beta |

People with experience of mental illness |

|

Gama |

People in an unemployed situation and at risk of social exclusion |

|

Delta |

People in an unemployed situation and at risk of social exclusion |

|

Kapa |

People with disabilities |

|

Lambda |

People in an unemployed situation |

|

Omega |

People in an unemployed situation + People with disabilities + People with addictive behavior |

|

Iota |

People in an unemployed situation and at risk of social exclusion |

|

Zeta |

People in an unemployed situation and at risk of social exclusion |

Source: adapted from case studies status

Despite the general profile presented in Table 1, the characterization of the target groups of each case proves to be more complex, with multiple variables. Focusing only on the predominant characteristics of the clients, we can outline a typical profile that integrates several features for each case study. As an illustrative example, we observe that Delta accompanies predominantly male individuals over the age of 40, while Gama mainly supports females who are mothers and may experience some mental health issues. Beyond formal categories like age, gender, and health status, other characteristics are identified, such as life and career paths marked by experiences of precariousness and fluctuations between employment and unemployment. The individuals also exhibit socio-emotional skills, including a lack of confidence in the labor market, social work, and themselves.

3.2. Challenges and Dilemmas

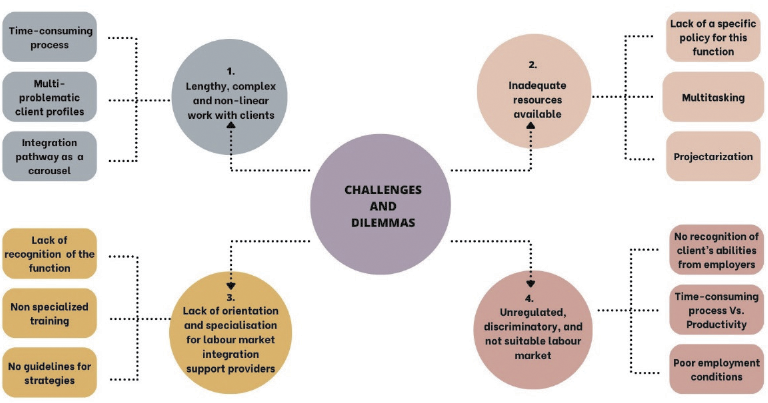

The findings across all nine case studies highlight four overarching categories of challenges faced by professionals who support individuals in vulnerable situations with their social and professional integration: i) Lengthy, complex and nonlinear work with clients; ii) Inadequate resources available; iii) Lack of orientation and specialization for labor market integration support providers; iv) Unregulated, discriminatory, and not suitable labor market.

Figure 1. Challenges and dilemmas faced by labor market integration support providers

Source: Nine case studies

3.2.1. Lengthy, complex and nonlinear work with clients

Regarding the first category, the interviewees often grapple with the complexity of the task at hand, compounded by the diverse profiles of their clients. Individuals seeking support vary widely in their proximity to the labor market, and the process is time-consuming. It frequently involves reactivating employability skills, and achieving results in this context is a gradual and challenging endeavor, as an interviewee pointed out: “It’s not something that we get immediate results, it’s gradual, it’s an achievement, but it’s a challenge” (Alfa E3). Consequently, providing sustained support over an extended period is essential to observe consistent and sustainable outcomes.

The clients themselves reveal structural situations of exclusion that extend beyond mere labor market exclusion. Given the multifaceted challenges faced by each individual, the process of work integration is far from linear. Progress is punctuated by setbacks and interruptions for various reasons, as highlighted by one interviewee: “If there’s a relapse in consumption here, if there’s a loss of housing, for example, employability work is halted” (Delta E2). The complexity of the challenges faced by clients underscores the need for a holistic approach that goes beyond individual interventions. Working at a meso level, professionals must engage with the broader context and support networks of the individuals they are assisting. This becomes especially crucial in cases involving individuals with a history of substance use, where sustaining abstinence and motivating for treatment demand special attention. In the field of vocational rehabilitation, namely, when working with individuals with mental illness experience, the complexity of the task necessitates close and regular monitoring and continuous adaptation of predefined plans. As one interviewee explained: “There is a lot of difficulty in having a well-outlined project from start to finish; there are always things that come up, obstacles, and the users’ relapses in terms of health” (Beta E2).

The profile of the clients presents a challenge, as it requires very intentional work on issues such as empathy and managing the frustrations of adults who tend to focus on difficulties in their discourse. It often involves unlocking ideas that have been built up over many years and hinder the effective work of change: ”very blocked in their own expectations when they think they already know everything’ [...] when the person is not open to change, they are very crystallized” (Lambda EE).

Low self-esteem and a lack of confidence in the training system and the labor market further demotivate individuals seeking support and create obstacles to successful intervention. Breaking away from previous unsuccessful support experiences is crucial. As one professional put it, they must “demystify with the participants that this is not like any other training” (Iota Field Diary, team meeting observation). Previous experiences, often characterized by a series of training programs, can foster resistance. Moreover, when individuals perceive prior experiences as ineffective, especially in terms of achieving meaningful professional integration, their scepticism deepens.

3.2.2. Inadequate resources available

For the interviewees, the complexity of the situations experienced by the clients does not align with the limitations imposed by the configuration of the support measures. The second category of constraints is related to the lack or inadequacy of available resources for the work.

The funding duration for facilitating labor market integration is perceived as inadequate. For instance, training programs that include short-term on-the-job training are deemed insufficient. Participants expressed that “three weeks is a very short period. We can accommodate them, but it’s challenging to establish a comprehensive understanding of each individual” (Iota Field Diary). Both the duration and budget constraints limit tailored interventions based on the unique needs of each person. As one interviewed noted, “Sometimes, we identify improvements and actions that could enhance the project, but due to budget constraints, we can’t implement them” (Iota E3). Moreover, in cases of on-the-job training, the support does not cover training grants for trainees, it only includes meal and transportation allowances. Consequently, many clients reject the proposed solutions by professionals or have to resort to sporadic informal jobs to supplement their income. It is essential to consider that clients, especially those facing financial constraints, need a significant amount of time to explore subsistence alternatives or attend to family care needs. Short-term needs can significantly impact long-term investment strategies.

The complexity of issues and the diverse vulnerability situations experienced by the clients create a paradox with the funding cycles of projects. Finite funding complicates sustained efforts with these target groups. The economic and financial sustainability challenges faced by social economy organizations result in professionals dedicating a significant portion of their efforts to seeking funding and preparing applications. Interviewees emphasized a constant need to apply for projects that always demand fresh ideas and proposals. Unfortunately, this often leads to a lack of recognition for tested and validated models, as many funding sources tend to standardize interventions without valuing alternative models in line with the funded intervention principles. Aside from the dispersion in the work carried out by professionals, project-based work necessitates constant adaptation of procedures associated with accountability rules, which vary from funder to funder. Adapting to each new funder often involves significant bureaucratic burdens.

According to the interviewees, this lack of continuity and human resources poses a significant limitation in current public policies. In cases Beta, Gama, and Kapa, all the work done by the support teams is deemed additional and showcases multitasking.

The support measures also reveal limitations in how clients can transition from passive to active employment measures. Interviewees identified several examples, highlighting the difficulty faced by individuals in leaving a secure income from the Social Insertion Income measure to enter the job market with precarious contractual ties, even if the income is meagre. In the interviewees’ opinion, some measures prove ineffective in promoting stable and enduring employment. Consequently, the risk an individual takes in leaving a support measure, no matter how small but regular, outweighs the benefit and limits the opportunities that professionals can present to the client through employment incentive mechanisms. The interviewees point out the administrative complexity of discontinuing social support to enter the job market as one of the barriers to the effective integration of clients. The abrupt cessation of the right to social assistance and financial support when the client reaches a job could sustain situations of full inclusion. Professionals have pointed out that it would be necessary to implement a transition period, with continued support, to ensure the effectiveness of inclusion. Interviewees also identified challenges arising from a legal void in Portugal regarding WISE. This gap leads to a lack of support, guidance, and time for managing social and inclusive businesses, coupled with obstacles from conventional funders of the case studies. For example, in the case of Zeta, the Social Security Institute, the public institution overseeing Zeta’s services, presents challenges in operationalizing the work.

3.3.3. Lack of orientation and specialization for labor market integration support providers

Regarding the third category of constraints, we identified in the interviews a lack of framework and guidance for the performance of the providers’ function. Since, in several cases, support for integration into the labor market is an additional function of their job description, labor market integration support providers identify the need for guidance in the employability area: “starting to work on employability is not easy because there is no systematic and easily accessible information, the information is scattered. There are no tools, guidelines, best practices” (Kapa EE).

Even in cases overseen by the public Institute of Social Security, the interviewees consider the guidance to be inadequate. Case Zeta highlights these difficulties, particularly regarding the assessment of the situations to be included in the semi-annual reports or in the annual Activity Plan. For example, the interviewees mention that they have never received technical content feedback on the plans or evaluation reports. When there is any feedback, it is limited to identifying typos, counting errors, etc. Regarding cases that develop social and inclusive businesses, the need for specialization also relates to areas of social enterprise management, which has been cumulatively ensured by the same professionals.

In addition, the need for guidance extends not only to the technical dimensions of the work performed by the providers but also to the emotional management dimension of the work. In fact, the interviewees point to the need for support associated with significant emotional strain and exhaustion from the social work by professionals. Coupled with a lack of professional appreciation and inadequate resources for performing their function, emotional strain becomes even more significant. The lack of recognition and specialization in the role hinders the career management of these professionals, acknowledging that their salary is partly psychological.

Thus, the interviewees point to the need for specific training. The search for an answer to their training, in some cases, involves more indirect strategies, namely participation in employability workshops aimed at unemployed individuals.

In the case of Beta, which supports people with mental illness experience, the interviewees emphasize the gaps in terms of training response. In fact, for professionals in the rehabilitation and mental health field, from the perspective of Beta case professionals, it is even more limited and lacks diversification of responses. Some labor market integration support providers sought for specialized training abroad.

3.3.4. Unregulated, discriminatory, and not suitable labor market

The last category encompasses a set of challenges associated with an ecosystem unfavorable to the integration of clients. Society remains stigmatizing, according to the interviewees, posing a barrier to client integration. This includes the lack of knowledge and prejudice on the part of employers regarding the abilities of clients. As an illustrative example, the Beta case, which supports people with mental illness experience, mentions that employers often make initial comments revealing this lack of knowledge and prejudice: “you can’t even tell they have a mental illness” (Beta EE). The existence of stigmas is consistently mentioned by various interviewees. According to them, changing the mindsets of employers is a complex task since companies often want someone “in their image and likeness” (Lambda E1) and may not be open to diverse profiles like those of the supported clients: “Because it’s not an easy audience, is it? [...] We already know, and this is common sense, that presenting a former convict to a company is very difficult. Or presenting someone who had and you can tell had alcohol or drug consumption, is also difficult, so um... First of all, I think there needs to be an openness from companies” (Omega E4). Employers often have firm views regarding gendered professions, for example, rejecting women for the role of car salesperson. The work of the interviewees also involves raising awareness among employers and trying to bring their clients closer. However, this contact is slow and nonlinear, marked by significant constraints: “for example, out of 200 emails we send to companies, we usually get one or two responses” (Iota E2).

The interviewees highlight other mismatches in job offers, particularly in terms of night work, considering the housing situations of clients without fixed addresses, especially in terms of incompatibility with the schedules of some temporary accommodation facilities. The interviewees mention difficulties in finding a perfect match between job offers and demand: “in small companies, sometimes there are no responses, but there is a more familiar and protected environment, and in large companies, there are more offers, but the environment is less protected” (Kapa EE). Limitations due to lack of public transportation, family dependencies, or low qualifications are also mentioned. The Lambda case operates in an area once marked by strong economic activity in the clothing industry. In this context, the clients often have a different profile from what current offers seek. In fact, on the one hand, current offers are often ill-suited. On the other hand, sometimes people with backgrounds in a particular area seek other professional experiences, as some of the clients express: “’I come from the footwear industry, but I don’t want shoes anymore.’ Indeed, people are tired of that [factory] environment” (Lambda E3), preferring job offers in the cleaning sector.

The expectations that the job market has for candidates are highly structured, with rigid rules, making it difficult for people who have been detached from formal work logics to fit in. The challenges for employers to embrace the mission of integrating people in vulnerable situations are also acknowledged by the interviewees since it demands a lot in the face of companies’ production challenges: “companies have their work pace and don’t always have this time available” (Iota E1).

Even when there is employer engagement, stable contracting is not guaranteed and the existence of working poor is a reality observed by the interviewees. Indeed, in many situations having a job will mean that the social support that the person had until then will cease (such as exemption from fees for access to healthcare, housing support, etc.). “And the person often said, ‘I mean, I earn more, but it seems like I earn less because I lost everything else I had.’ [...] The person became independent, but their situation actually becomes more complicated economically” (Zeta E1).

Final remarks

The research findings underscore the myriad challenges and dilemmas faced by labor market integration providers, particularly as Human Services workers addressing the needs of individuals with complex requirements (Hasenfeld, 1992). The principal obstacle identified succinctly summarized as historically inadequate resources (Lipsky, 1980) available for supporting clients in their social and labor inclusion efforts.

Professionals involved in the case studies align with contemporary paradigms, emphasizing individualized social and employment support (Ebersold, 2001; Castra, 2003) and advocating for diversity and inclusion in the labor market (Cox and Blake, 1991; Chidiac, 2020).

However, within the framework of individualized support, the policies seem ill-suited for work tailored to each client’s needs. The individualization of policy measures introduces the challenge of discretion, as identified by Lipsky (1980) and Hespanha (2008). While allowing room for innovation and personalized responses, this discretion also poses the risk of bias and prejudice from integration agents in less favorable situations. The labor market integration providers emphasize that, in certain instances, employability may not be a realistic goal for some of their clients. In such cases, their role is to assist these clients in managing their expectations. Embracing a rights-centered approach distances itself from the burdensome aspects of care work as “charitable and police burden” (Hespanha, 2008, p. 6). Instead, it underscores the significance of acknowledging the multidimensionality of problems and stresses the importance of collaborating with diverse local partners.

In the second paradigm, employers continue to display prejudice and resistance towards integrating individuals with complex profiles, as highlighted by our interviewees. Employer engagement with active labor market policies remains a persistent obstacle (van Berkel et al., 2017). The labor market integration providers interviewed emphasize that employers lack familiarity with the specificities and skills of candidates, necessitating the role of labor market integration providers in dispelling stereotypes and clarifying the capabilities of the clients they work with, as well as providing support for hiring. In this capacity, they assume a pedagogical and awareness-raising role.

Regarding the negative consequences of projectification (Greer et al., 2018; JRS, 2023), the study prompts reflection on the sustainability of social intervention. We questioned whether projectification might be a double-edged sword for the efforts of labor market integration providers. While project-based work has the potential to stimulate innovation, its effectiveness in addressing systemic issues, such as the employability of individuals with complex needs, appears to be doubtful.

In Portugal, even though there is no longer a legal framework for WISE, the data collected during this research shows, on the one hand, the need for a more structuring model of support, and on the other, the plurality and diversity of practices, tailored to the needs of each case study. A recommendation resulting from our research is to create umbrella organizations representing the field of integration. These organizations could create guidelines for the labor market integration support providers professional guidance, by producing benchmarks and promoting mutual learning through experience-sharing events. In addition, they could play an important role in representing the field at national level in international organizations, in a lobbying logic.

The need for specialization and professionalization of Labor market integration support providers is a cross-cutting concern for the different actors consulted throughout this research. Therefore, even though the role is not recognized, it is up to the teaching and learning systems, particularly higher education, to innovate in their training offer and meet emerging needs. We therefore suggest two types of offers for higher education and one for the nonhigher education continuing training system. The mission of higher education institutions is also to develop and promote research and applied research. Given the scarcity of scientific production and dissemination in Portugal about the social and labor integration of people in situations of vulnerability, research centers could be active agents in promoting this little-explored area that is of great use to the community, from the perspective of science at the service of social and economic development.

References

Alwang, J.; Siegel, P. & Jorgensen, S. (2001): “Vulnerability as Viewed from Different Disciplines”, World Bank Document, SP Discussion Paper, 0115.

Associação A3S. (2016): The marketing and coaching functions of work integrated social enterprises (WISE). An exploratory study in 5 European countries. http://www.evtnetwork.it/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/IO-1_Exploratorystudy_Final-Version.pdf.

Barel, Y. (1990). Le Grand Intégrateur. Connexions, Paris, n.56, 85-100

van Berkel, R., Ingold, J., McGurk, P., Boselie, P., Bredgaard, T. (2017). Editorial introduction: An introduction to employer engagement in the field of HRM. Blending social policy and HRM research in promoting vulnerable groups’ labour market participation. Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 27, Nº 4, 503-513. doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12169.

Bonoli, G. (2013). The origins of Active Social Policy. Labour markets and Childcare Policies in a Comparative Perspective. Oxford University Press

Boulayoune, A. (2012). L’accompagnement: une mise en perspective. Informations sociales, 169, 8-11. https://doi.org/10.3917/inso.169.0008

CASES (2021). Retrato da Mulher no Setor Coopertativo português. Cooperativa António Sérgio para a Economia Social.

Capucha, L. (2019). Pobreza e Emprego. As paralelas não convergem. SOCIOLOGIA ON LINE, n.º 19, junho 2019, 33-50. doi: 10.30553/sociologiaonline.2019.19.2

Castel, R. (2003). L’Insécurité sociale : qu’est-ce qu’être protégé? Éditions du Seuil.

Castra, D. (2003). L’insertion professionnelle des publics précaires. Presses Universitaires de France.

Chaves, R. & Monzón, J.L. (Dirs.) (2018). Best practices in public policies regarding the European Social Economy post the economic crisis. European Economic and Social Committee, CIRIEC. doi: 10.2864/551286.

Chidiac, E. (2020). Strategic Management of Diversity in the workplace. A comparative study of the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Australia. Routledge.

Cooney, K.; Nyssens, M. & O’Shaughnessy, M. (2023). Work Integration and Social Enterprises in. Yi, I. Encyclopedia of the Social and Solidarity Economy. A Collective Work of the United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on SSE (UNTFSSE), Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Cox, T.H. and Blake, S. (1991) Managing Cultural Diversity: Implications for Organizational Competitiveness. The Executive, 5, 45-56. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.1991.4274465

Defourny, J. & Nyssens, M. (Ed.) (2021). Social Enterprise in Wester Europe. Theory, Models and Practice. Routledge Studies in Social Enterprise & Social Innovation.

Defourny, J., Favreau, L. & Laville, J-L. (Dir.). 1998. Insertion et nouvelle économie sociale. Éditions Desclée de Brouwer.

Diogo, F. (2007). Pobreza, Trabalho, Identidade. Celta Editora.

Divay, S. (2012). Les réalités multiples et évolutives de l’accompagnement vers l’emploi. Revue Informations sociales, nº 169, 46-54. https://doi.org/10.3917/inso.169.0045

Ebersold, S., 2001. La naissance de l’inemployable, ou l’insertion aux risques de l’exclusion. Presses universitaires de Rennes.

Estivill, J., Bernier, A. & Valadou, C. (1997). Las Empresas Sociales en Europa. Comissión Europea DG V, Hacer Editorial.

Gorz, A. (1988). Métamorphoses du travail. Quête du sens: critique de la raison économique. Paris: Galilée.

Hasenfeld, H. (Ed.) (1992). Human Services as Complex Organizations. Sage Publications.

Hespanha, P. (2008). Politicas Sociais: novas abordagens, novos desafios. Revista de

Ciências Sociais. 39:1 (2008) 5-15

Hiez, D. (2021). Guide to the writing of Law for the Social and Solidarity Economy. SSE International Forum, Les Rencontres du Mont-Blanc.

INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatística (2023). Conta Satélite da Economia Social 2019-2020.

Junior, F. A.; Marques-Quinteiro, P.; Faiad, C.; Figueira, T.; Lima, A. & Freitas, L. (2021). “Without work, I am nothing, I have no identity”: a qualitative study in a Brazilian public organization. Public Sciences & Policies. Vol. VII , n.º 1, 2021, pp. 169-191. doi: 10.33167/2184-0644.CPP2021.VVIIN1

JSR (2023). Livro Branco sobre os direitos das pessoas imigrantes e refugiadas em Portugal. JRS Portugal.

Lima, L. & Trombert, C. (Dir.) (2017). Le travail de conseiller en insertion. ESF éditeurs.

Lipietz, A. (2001). Pour le tiers secteur L’économie sociale et solidaire : pourquoi et comment. Editions La Découverte.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-Level Bureaucracy. Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. Rusell Sage Publications.

Lipsky, M. (1969). Toward a Theory of Street-Level Bureaucracy. The American Political Science Association.

Lorey, I. (2015). Autonomy and precarization. In Nico Dockx, & Pascal Gielen (eds.). Mobile autonomy: exercises in artists’ self-organization. Valiz, p. 47-60.

Machado Pais, J. (2001). Ganchos, Tachos e Biscates: Jovens, Trabalho e Futuro. Ambar.

Marques, J. S., & Veloso, L. (2020). A Conceptual Review of Precarity. Literature Report. A3S: Porto. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6301006.

Martinho, A.L. & Gomes, M. (2021). Os perfis profissionais de Agentes de Inserção das Organizações da Economia Social. Revista Cooperativismo e Economia Social. Cooperativismo e Economía Social (CES). N.º 43(2020-2021). pp. 123-147. ISSN: 2660-6348

Meira, D. & Fernandes, T. (2021). The legal-labour protection of service providers in the collaborative economy and labour platform cooperatives. Revista Electróniuca de Direito – Junho 2021 – N.º 2 (VOL. 25), pp.237-267. doi 10.24840/2182-9845_2021-0002_0010

Meira, D. (2013). A Lei de Bases da Economia Social Portuguesa: do projeto ao texto final. CIRIEC-España, Revista Jurídica de Economía Social y Cooperativa,n.º 24, 2013, pp. 21-52.

Mintzberg, H. (2015). Rebalancing Society. Radical Renewal Beyond Left, Right, and Center. Berrett–Koehler Publishers, Inc. a BK Currents book.

Paul, M. (2020). La démarche d’accompagnement. Repères méthodologique et ressources théoriques. Deboeck supérieur.

Quintão, C., Martinho, A. L. & Gomes, M. (2018). As empresas sociais de inserção na promoção do emprego e inclusão social a partir de estudos de caso europeus. Revista Gestão e Sociedade, Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais – FAPEMIG, (v. 13, n.32), 2374-2391.

Ramos, A. (2000). Centralidade do Trabalho. In Cabral, M. V., Vala, J. & Freire, J. (Eds.), Trabalho e Cidadania: Atitudes Sociais dos Portugueses, (pp.48-71). Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa.

Renard, M. & Snelgar, R.J. (2017). Positive consequences of intrinsically rewarding work: A model to motivate, engage and retain non-profit employees. Southern African Business Review Volume 21, pp. 177-197. ISSN: 1998-8125

Sarfati, H. & Bonoli, G. (Ed.). (2002). Labour Market and Social Protection Reforms in International Perspective. Parallel or converging tracks? International Social Security Association.

Williams, A. E., Fossey, E., Corbière, M., Paluch, T., & Harvey, C. (2016). Work participation for people with severe mental illnesses: An integrative review of factors impacting job tenure. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 63(2), 65–85. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12237

Yin, R.K. (2009). Case Study Research. Design and Methods. Sage, USA.

1 Spain enacted its law in 2011, Portugal in 2013, France in 2014, Romania in 2015, Greece in 2016, and Poland and Bulgaria are still in the process of drafting national laws on the Social Economy (Hiez, 2021; Chaves & Monzón, 2018).

2 For each case study we use a code: Alfa, Beta, Gama, Delta, Kapa, Lambda, Omega, Iota, Zeta.