Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2019, vol. 43, pp. 37–56 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.43.3

Implementing Inclusive Education in Lithuania: What are the main Challenges according to Teachers’ Experiences?

Suvi Lakkala

University of Lapland

Faculty of Education

suvi.lakkala@ulapland.fi

Agnė Juškevičienė

Vilnius University

Faculty of Philosophy

Institute of Educational Sciences

agne.juskeviciene@fsf.vu.lt

Jūratė Česnavičienė

Vytautas Magnus University

Education Academy

jurate.cesnaviciene@vdu.lt

Sniegina Poteliūnienė

Vytautas Magnus University

Education Academy

sniegina.poteliuniene@vdu.lt

Stasė Ustilaitė

Vytautas Magnus University

Education Academy

stase.ustilaite@vdu.lt

Satu Uusiautti

University of Lapland

Faculty of Education

satu.uusiautti@ulapland.fi

Abstract. The purpose of this article was to analyse the challenges primary and subject teachers had experienced concerning the implementation of inclusive education in Lithuanian primary schools, progymnasiums and gymnasiums. In this study, 86 Lithuanian teachers reflected on their experiences of teaching in heterogeneous classes. The data were collected from 13 group interviews. The article highlights the challenges encountered by the primary and subject teachers in implementing inclusive teaching. The findings were arranged under four themes. Concerning teachers’ pedagogical competence, the teachers highlighted difficulties in differentiating their teaching and including the students with special educational needs in the classes’ social peer networks. Teachers also pointed out the need for multiprofessional collaboration and dialogue with parents. The themes were then interpreted in the theoretical frames of teachers’ professional competences. At a practical level, the study’s findings may help teacher educators understand the teacher competences needed to implement inclusive education and support them to develop existing teaching programs to target the successful implementation of inclusive education. At a conceptual level, this study presents evidence for preparing teachers to work in the conditions of striving towards inclusive education.

Keywords: inclusive education; students with special educational needs; primary teachers; subject teachers; improvement of teachers’ competencies.

Įtraukiojo ugdymo įgyvendinimas Lietuvoje: pagrindiniai mokytojų patiriami iššūkiai

Santrauka. Pagrindinė įtraukiojo ugdymo idėja – kokybiškas ugdymas(is) ir lygios galimybės visiems mokiniams nepriklausomai nuo jų ugdymosi poreikių. Tarptautiniame kontekste atlikti švietimo tyrimai (Määttä, Äärelä, and Uusiautti, 2018; Shepherd and West, 2016) rodo, kad mokytojams ir mokyklai kyla iššūkių įgyvendinant įtraukiojo ugdymo idėjas, išryškėja poreikis tobulinti mokytojų kompetencijas, kurios yra svarbios, siekiant sėkmingo įtraukiojo ugdymo realizavimo mokykloje. Įtraukiojo ugdymo kontekste profesinių kompetencijų tobulinimosi poreikį įvardija ir patys Lietuvos mokyklų mokytojai. Mokytojai reflektuoja ugdymo procesą, todėl svarbu analizuoti jų patirtis, siekiant atliepti jų kompetencijų tobulinimosi poreikius.

Straipsnyje analizuojami iššūkiai, kuriuos patyrė pradinio ugdymo ir mokomųjų dalykų mokytojai įgyvendindami įtraukųjį ugdymą. Savo patirtis, ugdant mokinius heterogeninėse klasėse, reflektavo 86 įvairiose Lietuvos miestų ir rajonų mokyklose, įvairiose bendrojo ugdymo (pradinio, pagrindinio, vidurinio) pakopose dirbantys mokytojai, turintys vyresniojo mokytojo arba mokytojo metodininko kvalifikacinę kategoriją. Straipsnyje pristatomo tyrimo duomenims rinkti taikytas sutelktųjų grupių (angl. Focus group) pusiau struktūruotas interviu, leidžiantis atskleisti pasirinkto tyrimo reiškinio plotmę, nes tyrimo dalyviai, atsakydami į pateiktus klausimus ir girdėdami vieni kitų atsakymus, gali papildomai komentuoti ir reaguoti į kitų tyrimo dalyvių perspektyvas (Bloor et al., 2001; Patton, 2002). Tyrimo duomenys analizuoti, taikant teminę analizę. Temos buvo konstruojamos remiantis Allday, Neilsen-Gatti ir Hudson (2013) teoriniais samprotavimais apie sėkmingam įtraukiojo ugdymo įgyvendinimui būtinus mokytojo gebėjimus. Į tai atsižvelgus, straipsnyje aprašomi radiniai buvo suskirstyti į keturias temas: Ugdymo diferencijavimas ir mokymosi proceso individualizavimas; Mokinių gerovė ugdymo(si) procese; Daugiaprofesinis komandinis darbas; Tėvų ir mokytojų dialogas.

Tyrimas atskleidė, kad mokytojai darbe susidūrė su tam tikrais iššūkiais: įtraukiojo ugdymo įgyvendinimas buvo sudėtingas, nes individualizuoto mokymosi, mokinių gerovės, daugiaprofesinio požiūrio į mokymą ir dialogo su tėvais idėjos negalėjo būti realizuotos tradiciniais mokytojų taikomais metodais ir ribotomis žiniomis apie mokinių, turinčių specialiųjų ugdymosi poreikių, ugdymą.

Tyrimo rezultatai padeda geriau suprasti vaidmenis, galimybes ir kliūtis, su kuriomis susiduria pradinių klasių ir dalykų mokytojai, ugdydami mokinius heterogeninėse klasėse, numatyti būdus, kaip suteikti tikslingą paramą mokytojams, kaip pagerinti mokytojų profesinį tobulėjimą ir sprendimų priėmimo nacionaliniu, savivaldybių ir mokyklų bendruomenių lygmeniu procesą, kad tai prisidėtų prie sėkmingo įtraukiojo ugdymo įgyvendinimo. Be to, tyrimas praplečia kitų tyrėjų įžvalgas apie įtraukiojo ugdymo įgyvendinimą skirtinguose sociokultūriniuose kontekstuose ir skirtinguose bendrojo ugdymo etapuose. Remiantis tyrimo rezultatais mokytojams įtraukiojo ugdymo srityje siūloma tobulinti ugdymo praktikos reflektavimo kompetenciją; gebėjimą įgyvendinti socialinio konstrukty-vizmo idėjomis grįstą mokymą(si), siekiant įgyti teigiamos įtraukiojo ugdymo patirties; mokytojo emocinį intelektą, kuris vaidina svarbų vaidmenį mokytojui sąveikaujant su mokiniais ir jų tėvais; bendradarbiavimo ir komandinio darbo kompetencijas.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: įtraukusis ugdymas; mokiniai, turintys specialiųjų ugdymosi poreikių; pradinių klasių mokytojai; mokomųjų dalykų mokytojai; mokytojų kompetencijų tobulinimasis.

Received: 04/11/2019. Accepted: 29/11/2019

Copyright © Suvi Lakkala, Agnė Juškevičienė, Jūratė Česnavičienė, Sniegina Poteliūnienė, Stasė Ustilaitė, Satu Uusiautti

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Including children with disabilities in mainstream education has been a global goal of educational reformists since 1990s, e.g. the Salamanca Statement (Slee, 2001; UNESCO, 1994). The goal of inclusion reflects the social model of disabilities, whereby society takes account of the diversity of its members (Peters, 2007). Indeed, the Program for International Student Assessment report (PISA) by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2011) showed that many well-performing education systems have achieved good results while including marginalised groups of students in mainstream education.

Among many other countries, Lithuania has reformed its educational legislation to better serve the goal of inclusive education. In this research, we ask what kinds of challenges primary and subject teachers encounter when teaching in heterogeneous classes. How do the teachers utilise the pedagogies related to inclusive education? Based on our findings, we ponder what kinds of professional competences would the teachers need, and are there any other kinds of issues causing challenges for their teaching?

In Lithuania, the idea of inclusive education is fairly new. The Lithuanian education system has been evolving towards a democratic justice since the escape from Soviet Union regime in 1990. Until that, the children with disabilities were placed in specialised boarding schools, and the segregated education built barriers for the inclusion of people with disabilities into society. School-aged children with moderate or severe mental disorders as well as those in need of particular care and attention would stay at home or be taken to residential care homes where they would be looked after but not educated. Due to the segregated school arrangements, the existence of the people with disabilities was invisible to most Lithuanians (Galkienė, 2017). The Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania (1991) validated the right of school-aged children with various developmental disorders to be educated in comprehensive schools or in specialized schools close to their parents. In 1998, the Law on Special Education of the Republic of Lithuania (Lietuvos Respublikos specialiojo ugdymo įstatymas, 1998) laid the legal foundation for the model of integrated education to transition from a strictly segregated system to an educational system open to all learners equally. Then the terms concerning the learners with various developmental disorders were changed to learners with special educational needs (SEN). The goal was to merge general and special education into a common educational space (Monkevičienė et al., 2017). Also, an intensive movement of school-aged children and youngsters from families and care homes to general schools or special education centres took place (Galkienė, 2017).

The Law Amending the Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania (2011) merged the two previous laws, the Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania and the Law on Special Education of the Republic of Lithuania. They evidence a sharp tendency to pursue the expansion of inclusive education of learners with SEN. Along with the National Education Strategy for 2013–2022 (Valstybinė švietimo 2013–2022 metų strategija, 2013), they aim to promote diversity in educational establishments by creating favourable learning conditions for all learners, according to their needs and abilities. The Lithuanian legitimate terminology does not include the term inclusive education. The terms special educational needs (SEN) and educational assistance, which covers special, special pedagogical, psychological, and social assistance, are used. There are two forms of education for learners with special educational needs in general education schools: education in a general class providing necessary student support, and education in a special class, usually for learners with intellectual disorders.

Determined by the Law Amending the Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania (2011), there are now three ways of implementing the curricula in general classrooms: the general curriculum and two levels of adjustment of it. The adjusted program creates the conditions for a learner to acquire basic, secondary or vocational education and/or qualification. Individualized program constructs the studies of learners with mental disorders, by individualizing pre-school, primary, and lower general secondary curricula. The studies are designed in collaboration with the students and their guardians. The Child Welfare Committees coordinate the arrangements for education assistance. The committees consist of a school leader, various specialists, teacher representatives, and representatives of learners’ parents.

In Lithuania, teacher training for inclusive education is regulated by two documents, Pedagogues’ Training Regulations (Pedagogų rengimo reglamentas, 2018) and Descriptor of Teacher Qualification Requirements (Reikalavimų mokytojų kvalifikacijai aprašas, 2014). The Lithuanian teacher education consist of pedagogical studies as well as subject knowledge and skills to identify “the specificities of psycho-physical level of maturity and special needs of children and pupils of a given age, recognizes pupils’ socialization, development and learning difficulties and helps overcome them, is able to provide psychological and pedagogical assistance…” (Galkienė, 2017, p. 77). Every teacher, either during the initial teacher education or as in-service training, must complete a 60-hour course on Special Needs Education and Psychology, approved by the Minister for Education, Science and Sport.

Theoretical framework

Research conducted in international education contexts has showed that the implementation of inclusion has certain challenges (see Määttä, Äärelä, and Uusiautti, 2018; Shepherd and West, 2016). How does inclusion materialize in practice, for example, in the form of student equity, participation, and sufficient support, is an important question. However, the foundation of this is to solve what do inclusive teacherhood and special education teacherhood necessitate to be successful (Määttä, Äärelä, and Uusiautti, 2018). Earlier research in Lithuania has suggested that teachers have disbelief in the abilities of students with disabilities, and, when talking about personal interaction, they often seek to distance themselves from these students and support segregationist ideas (Ališauskas and Šimkienė, 2013; Geležinienė, Ruškus, and Balčiūnas, 2008; Miltenienė, 2004, 2008). Teachers lack competence in differentiating and individualising their teaching (Ambrukaitis, 2004; Barkauskaitė and Sinkevičienė, 2012; Kaffemanienė and Lusver, 2004; Kiušaitė and Jaroš, 2012). Indeed, inclusion requires more and more versatile skills and expertise from teachers, as well as profound understanding about the ideology of inclusion (Määttä, Äärelä, and Uusiautti, 2018).

In their study, Allday, Neilsen-Gatti, and Hudson (2013) distinguished four global knowledge bases or skills that are necessary to a teacher who implements the ideas of inclusive education. Firstly, an inclusive teacher needs to be able to understand their role and position as a teacher of diverse students and to possess basic knowledge of special educational needs and the process by which the support is planned and constructed. Secondly, teachers need the competence of applying differentiated teaching methods when working with diverse students. Similarly, Shani and Hebel (2016) recognise the need for the competence of differentiated teaching when implementing inclusive education. The third global knowledge base is excellent classroom management when creating an optimal classroom microclimate and the sense of safety in students (see also Niemiec and Ryan, 2014). The fourth is the competence to work in collaboration with other teachers and specialists. Likewise, the ability to collaborate was identified as one of the crucial inclusive teacher’s skills in an international project called Teacher Education for Inclusion (Watkins and Donnelly, 2012).

Shani and Hebel (2016) see the teacher’s personal commitment and a sense of responsibility towards all students as a crucial part of the inclusive teacher’s professional identity. This argument resonates with many previous studies related to teachers’ professional development, in which the meaning of personal values, attitudes, beliefs and experiences is acknowledged (e.g. Levin and He, 2008). Teachers are seen as reflective practitioners, whose practical theories consist of private personal knowledge as well as theoretical and philosophical-ethical elements (Körkkö, Kyrö-Ämmälä, and Turunen, 2016), and they are made explicit to oneself during the reflective discussions in teacher education (Jay and Johnson, 2002). In the case of an inclusive teacher, the practical theory would include the ability to recognise and reflect the factors that support or hinder the inclusion of all students (cf. Shani and Hebel, 2016).

Methodology

Research purpose and questions

The purpose of this research is to analyse the situation of inclusive education in Lithuania and to provide research-based ideas of how to develop it qualitatively. We asked Lithuanian teachers to describe their experiences in practice. The following research question was set for this research: What kind of challenges have primary and subject teachers encountered when implementing inclusive education?

Research settings and participants

Research question was answered by analysing data obtained through focus group interviews among Lithuanian teachers. This research is part of a broader study that aims to increase understanding teacher’s needs to improve competencies. This study has received funding from European Social Fund project ‘Development of General and Subject-Specific Competencies of General Education Teachers’ (No. 09.4.2-ESFA-V-715-02-0001). Project organized by The Education Development Centre acting under the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport of Lithuania. The aim of the project is to provide conditions for general education schoolteachers to develop their general and subject-specific competences, as well as to improve the Lithuanian system of teacher qualification.

The teachers were purposively invited to join the research by criterion sampling (Patton, 2015). The teachers were to fulfil at following selection two criteria: 1) teachers in the Senior Teacher’s or Teacher-Methodologist qualification categories1 and 2) teachers were participating in in-service training (various seminars and training courses) to improve their competences. In addition, both primary education and subject teachers were invited. E-mail invitations to participate in the research were sent off to all 92 teachers, who had been selected by the Education Development Centre methodologists. Eighty-six teachers expressed their agreement for participation. Their teaching experience ranged from four to 42 years. The teachers were working in primary education (grades 1-4) and in secondary education (grades 5-12 and I-IV gymnasium). The participants came from different towns and centres of districts in Lithuania.

Data collection

The focus group interview (FGI) method was chosen for this research because it was considered to allow a vivid discussion about the chosen research problem (Patton, 2015). The teachers were divided into focus groups (N=13) according to their subject area. In the FGIs, the teachers of the same subject area were able to comment and react to the other participants’ perspectives (Gibbs, 2012). Two researchers participated in each FGI. At the beginning of every discussion, research participants were given detailed information on the research and the participants signed a consent form. The researchers presented themselves, the objectives and the detailed interview procedures, including the use of data and the research ethics. The discussion moderator was the main interviewer, whereas the second researcher, an active observer and listener of the discussion, was able to become involved in the discussion and present specifying or additional questions. In the interviews, the teachers were asked to consider their most difficult matters while teaching in mainstream classes. The main questions asked from the participants were, for example: What is the hardest part of teaching children a particular subject? Why do you think so? What kind of help would you require? The researchers asked additional questions on the matter. Their purpose was to unveil the exact difficulties the teachers faced when implementing the ideas of inclusive education in Lithuanian general education schools. During the discussions, the researchers sought to create a safe atmosphere and encouraged the participants to share their experiences (Zeichner, 2001).

The FGIs were conducted between June and December 2017. The discussions were conducted in Lithuanian and recorded with a voice recorder. Altogether, thirteen focus group interviews were organised. On average, the discussions lasted two and half hours. All the FGIs were transcribed verbatim for analysis. The date have been preserved in separate files whilst fully respecting the rules on confidentiality and anonymity. Table 1 presents the research participants by subject. In our data excerpts, we show the focus group of the interview, for example, Primary education teachers’ interview.

Table 1. Focus group interview participants

|

Study participants by subject |

Number of focus groups |

Number of teachers |

Teaching experience |

|

Primary education teachers |

1 |

8 |

4–42 years |

|

Languages (native, foreign) teachers |

3 |

18 |

7–38 years |

|

Mathematics teachers, information technology teachers |

2 |

19 |

5–33 years |

|

Natural sciences (biology, physics, chemistry) teachers, physical education teachers |

2 |

12 |

8–21 years |

|

Social sciences (history, geography) teachers, ethics teachers |

3 |

20 |

10–34 years |

|

Art teachers, technologies teachers |

2 |

9 |

4–11 years |

|

Total |

13 |

86 |

Data analysis

At first, a thematic reading of the data was used, and the themes were constructed through the theories of inclusive teaching. In the interpretative reading of the pedagogical themes, the conceptual context was the theories of teachers’ professional competences and identity. Data analysis was conducted using thematic qualitative analysis (Vaismoradi, Turunen, and Bondas 2013), which was guided by the theoretical considerations of inclusive pedagogy following the main themes expressed of Allday, Neilsen-Gatti, and Hudson (2013). According to Vaismoradi, Turunen, and Bondas (2013), thematic analysis is useful because it involves the search for and identification of common threads that extend across an entire set of interviews, in our case across FGI data. In the first step, the data were read through several times to give the researchers an overall comprehension of the data. The second step was to reduce and categorise the respondents’ statements in relation to the content’s meaning (O’Reilly, Ronzoni, and Dogra 2013). Preliminary data analysis was performed by the Lithuanian researchers separately. The third step was to make a critical analysis of the preliminarily established sub-themes to form more general themes, comparing them to theories of inclusive teaching. At this stage, all the researchers worked together. The researchers compared the preliminary sub-themes and themes to detect discrepancies between the researchers. The different interpretations of the data were resolved during mutual reflective discussions. Table 2 illustrates an example of the analytical process. The interview data that found its way into this article have translated from Lithuanian to English.

Table 2 . Example of the data analysis

|

Interview excerpts |

Reduced citation |

Sub-themes |

Themes |

|

A teacher prepares for his lesson and also has to prepare tasks additionally for eight pupils with special needs, the disorders of which are completely different; you’ve got to picture how extended the day of a teacher becomes [Social sciences and ethics teachers’ interview]. |

A teacher perceives the preparation of tasks for pupils with SEN as additional, time-consuming work |

Additional preparation for lessons |

Differentiation of teaching and individualisation of learning process |

|

[…] when there are children of different capacities, different abilities, […] some of them work well and do all the tasks, communicate, while the others cannot even understand what all this is about. Thus, to tailor this lesson to very diverse children, who […] can be in different levels, is a challenge [Social sciences and ethics teachers’ interview]. |

For the teacher it is difficult to differentiate the tasks for pupils at different levels of achievement |

Difficulties in differentiating tasks for SEN pupils |

Results

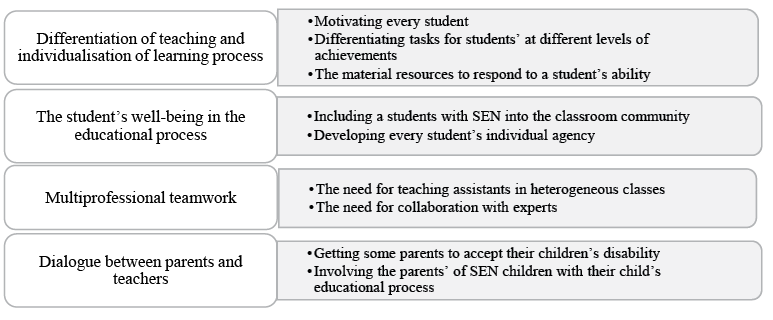

The teachers who participated in the study revealed their personal experiences in the area of inclusive education. The following work presents these teachers’ different insights regarding the implementation of the inclusive education process. Based on the data analysis, four themes and their sub-themes, which describe quintessential challenges arising to teachers in their educational practice, were distinguished. They are introduced in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The primary and subject teachers’ challenges in implementing inclusive education

In the following chapters, the themes describing the teachers’ challenges in implementing inclusive education are described in detail. In addition, they are analysed through the dimensions linked to inclusive teaching and pedagogy in previous research.

Differentiation of teaching and individualisation of the learning process

In the first theme, ‘differentiation of teaching and individualisation of the learning process’, one of the main challenges experienced by several teachers was the difficulty of motivating every student. For example one teacher, talking about students with SEN, noted that it is difficult to get them involved in the prepared tasks: ‘it is difficult, for example, there is some task, he doesn’t want to perform it, no matter what, then you ask him to model something from clay’. [Art and technologies teachers’ interview]. Here the teacher had difficulties taking the student’s desires into consideration, because she saw that the topic she had planned, i.e. an item to be sculptured from the clay, was the main goal for the lesson. According to the principles of inclusive teaching, an alternative way of interpreting the learning goal would be to practise sculpturing or enhancing the students’ artistic views. Then the outcome’s form could be individual and moulded according to the students’ interests (see e.g. Florian and Spratt, 2013).

Another challenge for the teachers was the difficulty to differentiate the tasks for students at different achievement levels:

[…] when there are children of different capacities, different abilities, with differences in perception or their emotional intellect, […] some of them work well and do all the tasks, communicate, while the others cannot even understand what all this is about. Thus, to tailor this lesson to very diverse children, who […] can be at different levels, is a challenge. [Social sciences and ethics teachers’ interview].

Another example of challenges linked to differentiation shows that teachers may plan teacher-led lessons, in a way that all the students are dependent on the teacher’s verbal instructions:

[…] those of a higher level are already standing behind my back and pulling my skirt. ‘What shall we do now?’ I am giving them a new task, but I don’t even have time to explain to them, because I already have to keep on explaining. [...] But, picture that the children of a higher level were able to do 5–6 pages per lesson. Whereas others, completed only [...] 2–3 lines and that with my continuous (support) ... you still need to push. [Primary education teachers’ interview].

Another teacher said: ‘[…] until I sit with Aleksiejus, he works, writes something, when only I leave him he does not do anything again, but I cannot pay all my attention only to him’ [Language teachers’ interview]. The teachers in aforementioned excerpts have difficulties to plan the lesson in a way that takes into consideration the students’ diverse needs. In inclusive teaching, a teacher uses various ways of studying (e.g. flexible peer groups), gives literal or visual instructions and differentiates the target group and the instruction intensity (see e.g. Lakkala and Määttä, 2011). In inclusive teaching, the various goals for students are set by keeping an eye on the students’ learning process and finding the individual strengths in each student (Tjernberg and Mattson, 2014).

In differentiation, the third issue was the lack of material resources with which to respond to students’ learning abilities. The teachers brought up the need for additional and differentiated material.

A teacher gets ready for a lesson and he must additionally prepare, well, say, tasks for eight pupils with special needs, for pupils whose disorders are completely different; only imagine how prolonged the day of a teacher becomes. [Social sciences and ethics teacher’s interview].

We don’t have any methodological material […]. If we find any text, an exercise on the internet, we give it to a child. [Language teachers’ interview].

The teachers pointed out that the number of textbooks suitable for students with SEN is insufficient in Lithuania. Moreover, they noted a lack of methodological aids containing tasks adapted for students with different abilities.

The students’ well-being in the educational process

The second theme of challenges was taking care of ‘students’ well-being in the educational process’ in the mainstream class. Many teachers found it challenging to include a child with SEN in the classroom community. Several teachers considered behavioural problems to be the most difficult when it comes to building relationships with peers:

Well, if there isn’t the one who, for example, shrieks, shouts, hits, bangs or if a child came with a problem, with special needs, he hits, throws his book at children, tears – all attention, I calm him down—when it comes to teaching and attention to all other children, it’s gone. [...] Therefore, the greatest problem is those children with special needs. To integrate them. We understand that it is a problem. We do not reject them [...] [Primary education teachers’ interview].

Our results indicate that the teachers lack the kinds of methods that support student’s socio-emotional development and social skills. For example, in Vitalaki, Kourakos, and Hart’s (2018) research, teaching methods such as talking, exchanging ideas orally, role-play and working in student groups helped the students to develop positive social performance such as confidence and empathy towards peers.

In some of our group interviews, teachers brought up the problem of some teachers’ negative attitudes towards students with SEN.

[…] there are others, they simply don’t love these children […]. This is a child, who does not bring me [a teacher’s] profit, will not raise the academic level of my class. So, he is not a child profitable to me, […] so he disturbs my lesson […] not able to manage classroom. Teachers […] do not understand that they reject, they think they put a lot of effort into upbringing, but really, that body language perhaps betrays them. I can say that I include them very much, but [...]. [Primary education teachers’ interview].

According to previous research, teachers’ own feelings of competence in teaching diverse learners and attitudes towards inclusive education have a relatively strong positive connection (e.g. Malinen, 2013). In addition, exam-oriented school culture is seen as a hindrance to inclusive education (see Miles and Singal, 2010). On the other hand, teachers felt that sometimes the difficulties of increasing understanding among peers were due to the general instructions given by the educational authorities:

The children, who are around, see that the child is different anyway. According to all the requirements, it turns out that you can’t tell children that he is autistic […]. And when we ask [from the special education teacher]: ‘How to tell those children, using which words, what should we do?’ They say: ‘Well, tell them that he is different’. Then: ‘In what way of “different”?’ Whatever it is, but the children see it anyway. [Primary education teachers’ interview].

In the theme of taking care of students’ well-being, the teachers found the development of every child’s individual agency to be another challenge. The teachers noticed that it is not enough that the students follow orders. The students also need to learn how to implement the learned knowledge or strategy autonomously:

I noticed that, in a one-on-one relationship, they do everything, use all the tools, whereas when they get back to their classroom they forget everything. I think that it is necessary to teach a child to use those means in the classroom. [Primary education teachers’ interview].

[...] I do not know, he learns according to a modified program, but there is something not connected […] he needs constant attention, he needs to sit side by side [with the teacher] […]. I do not know how it works for others, but it is very difficult for me. [Mathematics and information technology teachers’ interview].

These examples shed light on the need of multifaceted goals in inclusive teaching. Students’ self-regulation skills are not only important for learning outcomes but also crucial predictors of future adults’ agency and engagement in society (cf. Skinner, Pitzer, and Steele, 2016). Still, an inclusive teacher needs the skill to adjust the learning tasks to student’s individual level (Lakkala, Uusiautti & Määttä, 2016).

Multiprofessional teamwork

In the third theme, the challenges in ‘multiprofessional teamwork’ were identified. The majority of teachers pointed out the importance of professional teaching assistants (TAs). Teachers saw the class management as very difficult if they were to work alone with diverse students. Some teachers would have liked to instruct the weaker students while the TAs’ could assist the more advanced students.

[…] a teaching assistant […] can help not only the pupils with special educational needs [...]. I can work with the group of children, who have difficulties, but he can work with those who have understood what needs to be done […] but he is not available. [Natural sciences and physical education teachers’ interview].

Other teachers, conversely, preferred to concentrate their professional experience on more advanced students and let the TA support those with certain difficulties:

[...] if we integrate children with special needs, […] every one of us [teachers] must have an individual assistant as well. Now, when you are explaining to all on the blackboard, at the very same moment, four guys (SEN students) are already working on the computer. At that moment, I am not able to instruct the four students who are on the computer, because I have to show the others the following steps in the blackboard […]. [Mathematics and information technology teachers’ interview].

According to our data, one of the most relevant problems in teaching heterogeneous classes is the division of time and intensity used for students’ instruction (e.g. Lakkala & Määttä, 2011). Moreover, more than one supervising adult is often needed (e.g. Booth and Ainscow, 2002). Implementing inclusive education requires competence to apply various teaching methods during the lessons, for example station working, co-operative learning and scaffolding (Tomlinson and Moon, 2013). A strategy of instruction based on the students’ learning process is essential. Varying different methods teachers can address TAs’ supporting tasks and concentrate on, for example, instructing the groups of students who are studying in their proximal zone of learning (Lakkala & Määttä, 2011).

However, in the context of the research data, in spite of having a TA, some teachers also highlighted the importance of the TA’s professional competence:

I personally know from my experience that assistants hinder and don’t assist, because they do everything for the pupil. Then you must teach that assistant […]. Our goal is to remove that [pupil’s need for help] as quickly as possible […]. [Primary education teachers’ interview].

Indeed, there has been much debate about TAs’ deployment and appropriate role when supporting the learning of students with SEN in mainstream schools (see e.g. Webster et al., 2010). Teachers’ notions in our research bring out the importance of developing support in the classroom and the education of both teachers and TAs’ (cf. Takala, 2007).

In the theme of multiprofessional teamwork, the need for collaboration with experts also emerged. In a heterogeneous class, there are manifold problems, and one teacher cannot manage them all (Lakkala and Kyrö-Ämmälä, 2017), as can be seen in the research data:

Why are we inclined to put everything on our own shoulders? […] If there is a (student with) disorder, then perhaps you should get some professional assistance in the educational process. Here, a teacher sometimes becomes helpless. [Social sciences and ethics teachers’ interview].

Teachers in our research, based on their needs, also sketched new kinds of professional profiles for experts who could support their teaching. The teachers see their own pedagogical competence and knowledge base as inappropriate for the current circumstances in their classes:

[…] actually, that might be a solution and jobs could be created, if some consultant would be made available […] because I need to search now, if a child is aggressive out there, what I need to do. In order that I would not violate children’s rights. [Primary education teachers’ interview].

In heterogeneous classes, teachers need continuous pedagogical discussions with colleagues and other experts. Through those reflections, it is possible to identify the potential obstacles for students’ learning and problems in behaviour at early stage (Tjernberg and Mattson, 2014).

Dialogue between parents and teachers

Finally, the fourth theme was named as ‘dialogue between parents and teachers’. Teachers confronted many kinds of problems in trying to discuss children’s troubles with their families. Sometimes it was difficult for teachers to involve parents of children with SEN in the educational process, because parents may deny the child’s disability. Some teachers noted:

It would be good, if a child went to the [Pedagogical-Psychological] service with his parents, and had those papers [official decision of SEN]. How many parents […] don’t receive any support for their child? […] I, for example, had in my class one with papers [official decision] about special needs, and I actually had five [pupils with special educational needs but without an official decision of SEN]. [Primary education teachers’ interview].

The worst thing is when parents don’t want to acknowledge the emotional state of their child, for example, depression, which we detect at the very beginning and tell the parents straightaway. Parents just say: ‘Come on, he’s ok.’ [Social sciences and ethics teachers’ interview].

Some teachers tried to understand the parents’ motives for denial: ‘Parents are afraid of all the Pedagogical Psychological Services. […] they have the greatest guilt, what kind of a father or mother I am.’ [Primary education teachers’ interview]. Teachers were also aware that sometimes the communication about the student is negatively coloured: ‘[...] because, once again [parents may think]: “How many positive things have I heard about my child and how many negative things?”’ [Social sciences and ethics teachers’ interview]. Along with the idea of inclusive education, the importance of including families in educational decision-making has become obvious (Tjernberg and Mattson, 2014). Teachers are usually the first professionals to detect problems at school and thus the first ones to contact their pupils’ guardians. Our results are consistent with previous research that indicates that teachers experience their competence to collaborate with parents inadequate (Miller, Coleman, and Mitchell, 2018).

Discussion and Conclusions

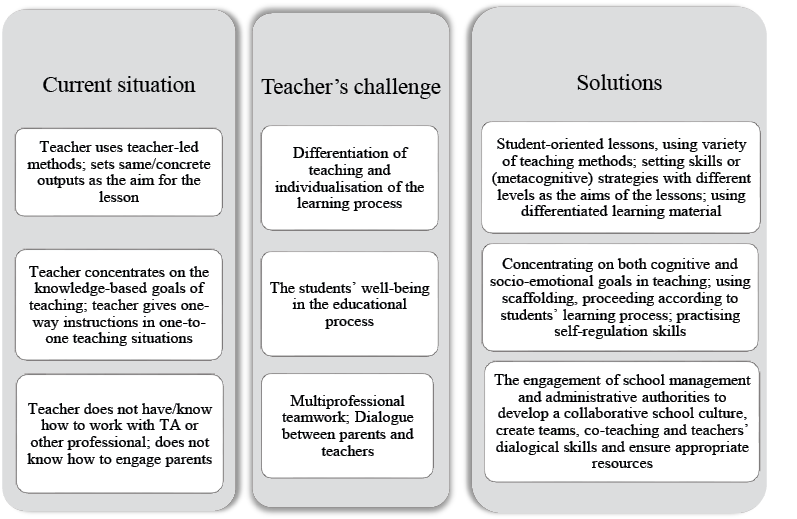

Based on our findings, the teachers encountered certain challenges in their work that seemed to be based on the methods they used in the current situation. The implementation of inclusion was challenging because the ideas of individualized learning, student’s well-being, multiprofessional approach for teaching, and dialogue with parents could not be met with traditional teacher-led methods and limited special educational knowledge. Figure 2 summarises our results under three themes: the current situation, the teacher’s challenges and the solutions based on inclusive pedagogy to meet the challenges in heterogeneous classes.

We have described the teachers’ own perceptions of their pedagogical challenges while teaching in heterogeneous classes. We have viewed the actions in the light of previous research, in order to get an idea of teachers’ performance in terms of inclusive pedagogy. Our results revealed that the pedagogical situations in heterogeneous classes are extremely multifaceted and involve various pedagogical choices to be made by the teachers. The knowledge and skills needed among the teachers in this research resonate with the results of Allday, Neilsen-Gatti, and Hudson (2013), described in the beginning of this study. Indeed, also other researchers have found out that one of the main difficulties when implementing inclusive education is the insufficient preparedness of teachers to work in ever-changing educational environments and respond to every student’s unique needs (Pit-ten Cate et al., 2018; Shani and Hebel, 2016).

Figure 2. Summary of themes and the pedagogical conceptualisation of the solutions to meet the challenges in heterogeneous classes

The idea of inclusive education has changed the paradigm of teaching and renewed the concept of teacherhood in a profound way (e.g. Lakkala, Uusiautti, and Määttä, 2016; Slee, 2001). This change in teachers’ thinking became visible in our research data also. According to our findings, the teachers’ decisions need to base on their diverse students’ developing learning processes (see also Allday, Neilsen-Gatti, and Hudson, 2013). This leads us to the conclusion that inclusive teachers’ professional development is dependent on their ability reflect their work constantly (Tjernberg and Mattson, 2014). Hence, the first wider competence we address to inclusive teachers is the competence of reflection. While the inclusive teachers, through reflective thinking, create the pedagogical knowledge based on their students’ needs, ontologically their starting point is the socio-constructivist approach. It means that the people involved in the school’s everyday life socially construct the knowledge (Brydon-Miller, Greenwood, and Maguire, 2003). The socio-constructivist learning concept is in line with the ontological basis of inclusion (the social model of disabilities) where the assumption is that obstacles in learning and participation are produced socially and they are dependent on the reactions of the society (Booth and Ainscow, 2002). Thus, the second wider inclusive teacher’s competence can be defined as the ability to implement teaching methods leaning on the socio-constructivist learning in order to gain positive experiences of implementing inclusive education (see also Galkienė, 2017).

The third inclusive teacher’s competence we bring up in our research is a teacher’s emotional intelligence, which provides an important framework to view how teachers encounter students and their parents. People with higher levels of emotional intelligence also report more positive interactions in their social relationships and are able to support others’ emotional abilities, too (e.g., Penrose, Perry, and Ball, 2007; Vesely, Saklofske, and Leschied, 2013). This competence is conducted from the findings indicating the teachers’ challenges in engaging the students with SEN to the class community and overall catering the students’ socio-emotional needs at school. For example, according to Monkevičienė et al. (2017), following the values of dignity, respect towards differences, acceptance and equality, the teachers create a warm, democratic, and supportive microclimate in the classroom as a community. Moreover, Skinner, Pitzer, and Steele (2016) point out that students’ relatedness will strengthen when they have chances to talk and listen to each other, share learning experiences and are given emotional support.

The fourth inclusive teacher’s competence we highlight in our conclusions is the competence of collaboration and multiprofessional teamwork. The teachers in our research stressed difficulties in collaboration with parents as well as other teachers (e.g. special education teacher). They lacked the help and support of other experts and they had various perceptions of how to collaborate with other adults at school (e.g. TA’s). The demand of (multiprofessional) collaboration is one of the most profound changes that has actualised along with the inclusive education. For a long time, the prevailing trend for teachers was to work alone, and the ability to manage alone the group of students was even an index of a teacher’s professionalism (cf. Hargreaves, 2000). However, according to previous research, multiprofessional and collaborative working practice is challenging. The different knowledge basis in various professions and the differing ways to interpret situations and solve problems may cause uncertainty among the professionals and lead to withdrawal from the collaboration (Edwards, Lunt, and Stamou, 2010; Rose and Norwich, 2014). In addition, to collaborate with other adults and parents is not merely a question of an individual teacher’s competence. Collaboration is also strongly related to the school culture in general, and thus needs attention when the legislative frames and curricula in educational systems are renewed.

Certain limitations exist in this research that are worth discussing. Although the focus group interview data appeared rich and allowed teachers express their opinions and perceptions freely, it is good to remember that the teachers were recruited from a certain type of group of teachers purposefully.

Regarding other reliability criteria for research, to allow transferability (see Shenton, 2004), we have described the most important historical developments of the implementation of inclusion in Lithuania. This was to help the reader to understand the findings that aroused from the focus group interview data among Lithuanian teachers. Qualitative research is rarely totally repeatable but naturally, in this research too, the purpose has been to report the data collection in sufficient detail. More importantly, we have used researcher triangulation to make sure that the findings emerge from the data. Also data excerpts as a part of findings were added to illustrate confirmability (Shenton, 2004). The overall purpose has been to credibly describe the current challenges encountered by Lithuanian teachers when implementing inclusive education.

Since the previous research has pointed out the significance of teachers’ values and attitudes (e.g. Tjernberg and Mattson, 2014), it would have been interesting to interpret the teachers’ indirect expressions when they were describing quite straightforward practical situations. Still, in order to make interpretations, we would also have needed additional data, for example class observations.

Lithuania has reformed its compulsory education at a rapid pace. In many other European countries, there have been difficulties in adopting the paradigm of inclusive education (e.g. Slee, 2001; Shepherd and West, 2016). Now Lithuania has introduced a new concept of teacher education to better meet the needs of an inclusive school system (The Good School Concept, 2015; Pedagogues’ Training Regulations, 2018). When reforming education, besides the initial teacher education, teachers’ in-service training becomes important. In our data, many teachers had their teacher training before the Lithuanian education reforms took place. In Lithuania, teachers are obliged to have five days of in-service training yearly. In addition, they can have their pedagogical performance evaluated and may acquire a new qualification category. In Lithuania, if a teacher consistently develops their professional competence, it leads to a higher salary and better career opportunities (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, n.d.). These kinds of incentives are likely to strengthen the teachers’ willingness to develop their professional competence. In addition, the quality and the systematic nature of teachers’ in-service training will still be crucial when trying to overcome the challenges identified by the teachers. The successful experiences of teaching in heterogeneous classes are likely to improve the teachers’ attitudes towards students with SEN and to diverse learners overall (Avramidis and Kalyva, 2007).

This research helps to better understand the role, possibilities and obstacles that primary and subject teachers face while teaching in heterogeneous classes. It also helps to foresee ways to enhance teachers’ professional development and the role of national, municipal and school community-level decision making contributing to successful implementation of inclusive education. This research is valuable because it broadens the theoretical insights of previous researchers about the implementation of inclusive education in different sociocultural contexts and the implementation of inclusive education at different stages of general education. In addition, the research data can help to provide targeted support for teachers to help them make inclusive education work in practice.

Further research could focus on revealing the supportive and disruptive factors affecting the experiences of inclusive education for students and parents in education, which would allow seeing more diverse perspectives of implementing the process of inclusive education. Further research could also relate to analysing the school management’s role in inclusive school settings, which would allow seeing the process of inclusive education from more varied perspectives.

Declaration of interest statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Ališauskas, A., & Šimkienė, G. (2013). Mokytojų patirtys, ugdant mokinius, turinčius elgesio ir (ar) emocijų problemų [Teachers’ Experiences in Educating Pupils Having Behavioural and / or Emotional Problems]. Specialusis ugdymas, 1(28), 51-61. Retrieved from http://www.sumc.su.lt/images/journal2013_1_28/13_alisauskas_simkiene_en.pdf

Allday, R. A., Neilsen-Gatti, S., & Hudson, T. (2013). Preparation for Inclusion in Teacher Education Pre-Service Curricula. Teacher Education and Special Education, 36(4), 298-311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413497485

Ambrukaitis, J. (2004). Pedagogų nuomonė apie savo pasirengimą ugdyti vaikus, turinčius specialiųjų poreikių [Teachers‘ Reflections on Being Ready to Educate SEN Children]. Specialusis ugdymas, 2(11), 114-123.

Avramidis, E., & Kalyva, E. (2007). The Influence of Teaching Experience and Professional Development on Greek Teachers’ Attitudes towards Inclusion. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 22(4), 367-389. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250701649989

Barkauskaitė, M., & Sinkevičienė, R., (2012). Mokinių mokymosi motyvacijos skatinimas kaip vadybinė problema [The encouragement of pupils’ learning motivation as a management problem]. Pedagogika, 106, 49-59.

Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2002). Index for INCLUSION: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools. London: Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education. Retrieved from https://www.eenet.org.uk/resources/docs/Index%20English.pdf

Brydon-Miller, M., Greenwood, D., & Maguire, P. (2003). Why Action Research? Action Research, 1(1), 9-28.

Edwards, A., Lunt, I., & Stamou, E. (2010). Inter-professional work and expertise: New roles at the boundaries of schools. British Educational Research Journal, 36(1), 27-45.

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (n.d.). Country information for Lithuania - Teacher education for inclusive education. Retrieved from https://www.european-agency.org/country-information/lithuania/teacher-education-for-inclusive-education

Florian, L., & Spratt, J. (2013). Enacting Inclusion: A Framework for Interrogating Inclusive Practice. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 28(2), 119-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2013.778111

Geležinienė, R., Ruškus J., & Balčiūnas, S. (2008). Mokytojų veiklų, ugdant emocijų ir elgesio sutrikimų turinčius vaikus, tipologizavimas [Typology of Teachers’ Activities in Educating a Child with Emotional and Behaviour Difficulties]. Specialusis ugdymas, 2(19), 45-58.

Gibbs, A. (2012). Focus Groups and Group Interviews. In J. A., M. Waring, R. Coe, & L. V. Hedges (Eds.), Research Methods & Methodologies in Education (pp. 186-192). London: Sage.

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Four ages of professionalism and professional learning. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 6(2), 151-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/713698714

Jay, J., & Johnson, K. (2002). Capturing Complexity: A Typology of Reflective Practice for Teacher Education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(1), 73-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00051-8

Kaffemanienė, I., & Lusver, I. (2004). Moksleivių, turinčių mokymosi negalių, bendrojo lavinimo turinio individualizavimas [The Individualization of the Educational Content for Children with Learning Disabilities]. Specialusis ugdymas, 2(11), 133-150.

Kiušaitė, J., & Jaroš, I. (2012). Peculiarities of Social Integration of Adolescents with Hearing Impairment. Socialinis ugdymas, 19 (30), 101-112.

Körkkö, M., Kyrö-Ämmälä, O., & Turunen, T. (2016). Professional Development through Reflection in Teacher Education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 55, 198-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.014.

Lakka.la, S., & Kyrö-Ämmälä, O. (2017). The Finnish school case. In A. Galkienė (Eds.) Inclusion in socio-educational frames. Inclusive school cases in four European countries (pp. 267-309). Vilnius: The Publishing House of the Lithuanian University of Educational Sciences.

Lakkala, S., & Määttä, K. (2011). Toward a Theoretical Model of Inclusive Teaching Strategies – An Action Research in an Inclusive Elementary Class. Global Journal of Human Social Science, 11(8), 30-40.

Lakkala, S., Uusiautti, S., & Määttä, K. (2016). How to Make the Neighbourhood School for All? Finnish Teachers’ Perceptions of Educational Reform Aiming Towards Inclusion. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 16 (1), 46-56. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12055

Law Amending the Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania (2011). Official Gazette, 2011-03-31, No. 38-1804. Retrieved from https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.407836

Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania (1991). Retrieved from https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/07c2ecf0168711e6aa14e8b63147ee94?jfwid=rivwzvpvg

Levin, B., & He, Y. (2008). Investigating the Content and Sources of Teacher Candidates’ Personal Practical Theories. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(1), 55-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487107310749

Lietuvos Respublikos specialiojo ugdymo įstatymas [Law on Special Education of the Republic of Lithuania] (1998). Retrieved from https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.69873

Määttä, K., Äärelä, T., & Uusiautti, S. (2018). Challenges of special education. In S. Uusiautti & K. Määttä (Eds.) New methods of special education (pp. 13-29). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Malinen, O-P. (2013). Inclusive Education from Teachers’ Perspective: Examining Pre- and In-Service Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Attitudes in Mainland China. Dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Education, University of Eastern Finland, Philosophical Faculty. Retrieved from http://epublications.uef.fi/pub/urn_isbn_978-952-61-1167-4/index_en.html

Miles, S., & Singal, N. (2010). The Education for All and Inclusive Education Debate: Conflict, Contradiction or Opportunity? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802265125

Miller, G. E., Coleman, J., & Mitchell, J. (2018). Towards a Model of Interprofessional Preparation to Enhance Partnering Between Educators and Families. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(3), 353-365. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1465660

Miltenienė, L. (2004). Pedagogų nuostatos į specialųjį ugdymą ir ugdymo dalyvių bendradarbiavimą: struktūros ir raiškos ypatumai [Teachers’ Attitude to Special Education and to Co-operation of Participants of Education: Peculiarities of Structure and Expression]. Specialusis ugdymas, 2(11), 151-165.

Miltenienė, L. (2008). Vaiko dalyvavimas, tenkinant specialiuosius poreikius bendrojo lavinimo mokykloje [Child’s Participation in Meeting Special Needs in General Education Schools]. Specialusis ugdymas, 1(18), 179-190.

Monkevičienė, O., Ustilaitė, S., Navaitienė, J., & Juškevičienė, A. (2017). Theoretical Modelling of Inclusive Education in Research by Lithuanian Researchers. In A. Galkienė (Eds.) Inclusion in socio-educational frames. Inclusive school cases in four European countries (pp. 146-170). Vilnius: The Publishing House of the Lithuanian University of Educational Sciences.

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in the Classroom. Applying Self-Determination Theory to Educational Practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 133-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318

O’Reilly, M., Ronzoni, P., & Dogra, N. (2013). Research with Children: Theory & Practice. London: Sage.

OECD (2011). Lessons from PISA for the United States, Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pedagogų rengimo reglamentas [Pedagogues’ Training Regulations] (2018). Order No. V-501 of 29 May 2018 of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania. Retrieved from https://e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/12340f50630811e8acbae39398545bed

Penrose, A., Perry, C., & Ball, I. (2007). Emotional intelligence and teacher self efficacy: The contribution of teacher status and length of experience. Issues in Educational Research, 17(1), 107-126. Retrieved from http://www.iier.org.au/iier17/penrose.html

Peters, S. J. (2007). Education for All? A Historical Analysis of International Inclusive Education Policy and Individuals with Disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 18(2), 98-108. https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073070180020601

Pit-ten Cate, I. M., Markova, M., Krischler, M., & Krolak-Schwerdt, S. (2018). Promoting Inclusive Education: The Role of Teachers’ Competence and Attitudes. Insights into Learning Disabilities 15(1), 49-63. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1182863

Reikalavimų mokytojų kvalifikacijai aprašas [Descriptor of Teacher Qualification Requirements] (2014). Order No. V-774 of 29 August 2014 of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania. Retrieved from https://e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/7f45d9f02f7911e4a83cb4f588d2ac1a/asr

Rose, J. & Norwich, B. (2014). Collective commitment and collective efficacy: A theoretical model for understanding the motivational dynamics of dilemma resolution in inter-professional work. Cambridge Journal of Education, 44(1), 59-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2013.855169

Shani, M., & Hebel, O. (2016). Educating Towards Inclusive Education: Assessing a Teacher-Training Program for Working with Pupils with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) Enrolled in General Education Schools. International Journal of Special Education, 31(3), 1-23. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1120685

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22, 63-75. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ792970

Shepherd, K. G., & West, J. E. (2016). Changing times: introduction to the special issue. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 39(2), 81-82. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0888406416638515

Skinner, E. A., Pitzer, J. R., & Steele, J. S. (2016). Can Student Engagement Serve as a Motivational Resource for Academic Coping, Persistence, and Learning During Late Elementary and Early Middle School? Developmental Psychology, 52(12), 2099-2117. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000232

Slee, R. (2001). Social Justice and Changing Directions in Educational Research: The Case of Inclusive Education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 5(2-3), 167-177. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110010035832

Takala, M. (2007). The Work of Classroom Assistants in Special and Mainstream Education in Finland. British Journal of Special Education, 34(1), 50-57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2007.00453.x

The Good School Concept (2015). Order No. V-1308 of 21 December 2015 of the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Lithuania. Retrieved from http://www.nmva.smm.lt/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Geros-mokyklos-koncepcija-angl%C5%B3-kalba.pdf

Tjernberg, C., & Mattson, E. H. (2014). Inclusion in Practice: A Matter of School Culture. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 29 (2), 247-256. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.891336

Tomlinson, C. A., & Moon, T. N. (2013). Assessment and Student Success in a Differentiated Classroom. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

UNESCO (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Salamanca. Spain: UNESCO, Ministry of Education and Science. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

Valstybinė švietimo 2013–2022 metų strategija [The National Education Strategy for 2013–2022] (2013). Valstybės žinios, 140-7095. Retrieved from https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.463390

Vesely, A. K., Saklofske, D. H., & Leschied, A. D. W. (2013). Teachers – the vital resource: the contribution of emotional intelligence to teacher efficacy and well-being. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28(1), 71-89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573512468855

Vitalaki, E., Kourkotas, E., & Hart, A. (2018). Building Inclusion and Resilience in Students with and Without SEN through the Implementation of Narrative Speech, Role Play and Creative Writing in the Mainstream Classroom of Primary Education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(12), 1306-1319. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1427150

Watkins, A., & Donnelly, V. (2012). Teacher Education for Inclusion in Europe. Challenges and Opportunities. In C. Forlin (Eds.) Future Directions for Inclusive Teacher Education. An International Perspective (pp. 192-202). London: Routledge.

Webster, R., Blatchford, P., Bassett, P., Brown, P., Martin, C., & Russell, A. (2010). Double Standards and First Principles: Framing Teaching Assistant Support for Pupils with Special Educational Needs. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 25(4), 319-336. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2010.513533

Zeichner, K. (2001). Educational Action Research. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.) Handbook of Action Research - Participate Inquiry and Practice (pp. 273-283). London: Sage.

1 In Lithuania, there are the four different qualification categories teachers can aspire to: 1. Teacher (mokytojas); 2. Senior Teacher (vyresnysis mokytojas); 3. Teacher-Methodologist (mokytojas metodininkas); 4. Teacher-Expert (mokytojas ekspertas). These qualification categories represent career steps associated with specific responsibilities and a salary supplement.