Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2020, vol. 45, pp. 60–76 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.45.4

English Language Policy in Relation to Teachers and Teacher Educators in Latvia: Insights from Activity Systems Analysis

Tatjana Bicjutko

University of Latvia, Latvia

tatjana.bicjutko@lu.lv

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9894-7555

Līva Goba-Medne

University of Latvia, Latvia

liva.goba-medne@lu.lv

Abstract. The ambitious objectives of European language policy and the strive for competitiveness have led to an increasing emphasis on foreign language competence at the level of national education systems. Using Spolsky’s onion model of language policy (2004) and Engeström’s Expansive Learning theory (1987, 2008), the study attempts to determine the formative influence of the existing multilayered language policy on the professional development of Latvian educators with the aim to compare the situation for teachers and teacher educators in respect of their English language proficiency.

Given the prioritisation of English and strategic differences in foreign language management in relation to teachers and faculty, the activity systems analysis points to significantly higher demands and concomitant pressure in respect of English language competence of academic staff, and the lack of incentives to increase their proficiency for teachers. Remedying the existing situation through policy making, both systemic and individual perspectives should be taken into account, as their interplay affects the agency of educators in achieving the goals.

Keywords: language policy, development of English language proficiency, activity systems analysis, academic staff, teachers

Anglų kalbos politika mokytojų ir mokytojų rengėjų atžvilgiu Latvijoje: įžvalgos pritaikius veiklos sistemų analizę

Santrauka. Ambicingi Europos kalbų politikos tikslai ir pastangos užtikrinti konkurencingumą paskatino nacionalinėse švietimo sistemose daugiau dėmesio skirti kalbų kompetencijai. Šiame straipsnyje naudojant Spolsky „svogūno“ kalbų politikos modelį (2004) ir Engeström besiplečiančio mokymosi teoriją (1987; 2008) siekiama nustatyti formuojamąjį daugiakryptės kalbų politikos poveikį profesiniam Latvijos ugdytojų rengimui bei norima palyginti esamas anglų kalbos mokėjimo sąlygas mokytojams ir mokytojų rengėjams.

Nepaisant anglų kalbos prioretizavimo ir strateginių skirtumų administruojant užsienio kalbas mokytojų ir dėstytojų atžvilgiu, veiklos sistemų analizė atskleidė reikšmingai didesnius reikalavimus anglų kalbos kompetencijai ir su tuo susijusį spaudimą akademiniam personalui bei mokytojų paskatinimo stiprinti jų anglų kalbos mokėjimo lygį trūkumą. Gerinant esamą kalbų politikos situaciją, svarbu atkreipti dėmesį tiek į sisteminę, tiek į individualią perspektyvą, kadangi šių lygmenų sąveika turi įtakos tam, kaip mokytojų rengėjai pasieks išsikeltus tikslus.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: kalbos politika, anglų kalbos mokėjimo tobulinimas, veiklos sistemų analizė, akademinis personalas, mokytojai.

Received: 22/05/2020. Accepted: 10/10/2020

Copyright © Tatjana Bicjutko, Līva Goba-Medne, 2020.

Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

With its proverbial recommendation of “teaching at least two foreign languages from a very early age” (EC, 2002, p. 19), European policy of multilingualism places a steadily growing emphasis on multilingual competencies and foreign language skills as a competitive advantage in the context of global competition (Leech, 2017). Another circumstance is that even after Brexit, English still maintains its linguistic hegemony (Trajectory Partnership, 2018), and its leading position as the first foreign language over the European Union was convincingly protocoled in a proposal for a comprehensive approach to the teaching and learning of languages (EC, 2018b) as well as adopted by the education ministers at the Council meeting in Brussels (EC, 2019).

The ambitious objectives of European language policy have led to an increasing emphasis on multilingual competences at the level of national education systems. The functional utility of foreign language skills in general and the competitive advantage provided by English linguistic competence (EC, 2017) in particular resonate at the level of national and institutional policies. Additionally, the inevitable growth of public expectations (EC, 2018c) may and occasionally does result in the institutional pressure on educators, who are both tools for implementing EU strategic decisions and guarantors of its success at the grassroots level. Therefore, the examination of the interplay of various layers of EU and national language policy, as well as their impact on the practices of professional development of both teachers and teacher educators, may help expose existing contradictions and tentatively point to their solutions.

Hence the research questions are as follows:

• What is the place of the English language within the multilayered structure of EU and Latvian foreign language policies?

• How is the existing English language policy reflected in Latvian educators’ daily practices, and especially that of their professional development?

• Are there any systemic contradictions disincentivising and/or hindering the enhancement of English language proficiency of teachers and teacher educators?

To answer the questions, several objectives are set forth: (1) to outline the hierarchy of existing foreign (English) language policies that affect educators in Latvia as well as to map any differences in the impact as concerns teachers and university staff, (2) to model the structure of teachers’ and teacher educators’ activity of English language proficiency development, (3) to convey the activity systems analysis aiming at revealing existing contradictions, and (4) to summarise the obtained data by making relevant conclusions and putting forward tentative suggestions for overcoming hindrances on the way to educators’ English proficiency enhancement.

Research methods and procedure

The study is a mixed method qualitative research employing an inductive approach. First, document analysis is used to outline the relevant regulatory framework, with Spolsky’s “onion” model of language policy (2009) employed to describe the multilayered nature of the expectations/requirements in respect of foreign (English) language competence of educators in Latvia. Further, language management is analysed using Engeströms’ (1987) method allowing to view the collected data through the perspectives of educators confined to implement the policies in practice and to create a model of the activity systems of English language proficiency development of educators. The ensuing analysis of the created model helps in exposing systemic contradictions, which are to be discussed in the end.

In a nutshell, language policy is an application of power to language or a set of activities designed and carried out to regulate language use. “[L]anguage policy functions in a complex ecological relationship among a wide range of linguistic and non-linguistic elements, variables and factors” (Spolsky, 2004, p. 41), and, although its concepts are “fuzzy and observer dependent” (ibid.), it is language policy that underlies the choice of a language or its variety in any social situation.

Commonly associated with what a national government does officially through legislation and policy enactments, language policy goes beyond that and it “is also established by other actors, for example, school administrators who develop guidelines for language use within the institution, or lecturers who choose to speak a language/variety in a class. To put it simply, language policy is found wherever language is used” (Rozenvalde, 2018, p. 8).

Spolsky (2004, 2009) offers his “tripartite division of language policy into (1) language practices, (2) language beliefs and ideology, and (3) the explicit policies and plans resulting from language-management or planning activities that attempt to modify the practices and ideologies of a community” (Spolsky, 2004, p. 39). Prescriptive measures introduced by different social actors involved in language management are often heterogeneous and occasionally mutually contradictory; what is more, de jure policies are not quite the same as language practices. So, to have a fuller understanding of language policy, a line should be drawn between written laws and the way they are implemented de facto in practice. For the purposes of the present study, however, the focus is on language management or planning and its multi-layered structure as it affects the education system in Latvia.

Thus, the starting point are the language-related directives issued at the EU level. Global university ranking, which is a hierarchically higher level of management for tertiary education, is not to be considered separately, for it is deeply integrated in EU policy making. Next, language use is regulated at a national level, so regulatory documents formulating national language policy are to be parsed. The resulting onion model of language policies would be an abstraction if not expanded horizontally. Policies being essentially multi-sited by nature, they diverge considerably in relation to different groups of educators. Therefore, to reveal contesting aspects and contradictions within the education system in Latvia, the activity systems analysis is to become the second stage of the study.

Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) is a multidisciplinary research approach put forward by Engeström and associated researchers (Engeström & Sannino, 2010). The conceptual tool used in this study – the model of the activity system (Engeström, 1987; Engeström & Sannino, 2010) – offers a level of abstraction together with practicality in analysing human systems. Having demonstrated its efficacy in a workplace environment and transformation research (Blayone & VanOostveen, 2020), activity theory is a well-established and widely deployed research tool in the field of education too (Barab et al., 2002; Behrend, 2014; Bligh & Flood, 2017; Engeström, 2008; Mentz & De Beer, 2017; Yamagata-Lynch & Haudenschild, 2009).

Oriented towards the development and reshaping of work practices, CHAT distinguishes actions that are individual, short-lived and goal-directed from activity systems that are social, durable and object-oriented (Engeström, 2000). In linking individual and social levels, activity systems analysis adheres to several core principles, namely: (1) human activity is taken as a holistic, socially situated, object-oriented and culturally mediated system; (2) tensions are arising both within and among elements and activity systems, and contradictions are considered the sources of change and development; (3) heterogeneous perspectives coexist in any activity system, and this multi-voicedness of an activity is multiplied via networks of activity systems; (4) the principle of historicity presents activity systems as having taken shape and been transformed over lengthy periods of time (Engeström, 1987, 2000). Since the focus is on English language proficiency of educators as part of their professional development, the above-stated principles provide a critical lens to identify key elements of the system and examine their interrelationship. Finally, the analysis aims at highlighting systemic contradictions and putting the system in historical perspective.

Premised on the above, the first step, document analysis, serves as a form of “conflictual questioning of the existing standard practice” (Engeström, 2009, p. 69). Next is modelling with the help of activity theory, followed by an activity systems’ analysis. Identifying systemic problems or contradictions within and among elements of the activity systems may explain failures or difficulties in language policy implementation as well as map areas for further research.

The hierarchy of existing foreign language education policies

EU language policy

First, language management will be discussed at the EU level.

It is a truism to say that the future of Europe is the central concern of the EU governing bodies. Since “[t]he Union is first and foremost a Union of values, as enshrined in Article 2 of the Treaty on the European Union, and education, training and culture are crucial for transmitting and promoting common values and building mutual understanding” (EC, 2018b, p. 1), educational policies are especially important for the European project. The need to strengthen the educational systems of the member states is self-explanatory, and the pledge is to work towards a “Union where young people receive the best education and training and can study and find jobs across the continent” (Council of the EU, 2017), among other things. The joint work is underpinned by “a number of key initiatives, including the Erasmus+ programme, European universities, language learning, the European Student Card, the mutual recognition of diplomas and the European Year of Cultural Heritage” (EC, 2018b, p. 3), and all the above-listed actions are intertwined and mutually reinforcing in reaching the overarching goal of establishing a European Education Area by 2025.

With this vision of “a Europe in which learning, studying and doing research would not be hampered by borders” (EC, 2017, p. 11), “boosting language learning” is at the heart of the shared agenda. The benchmark is set high, and it is “that, by 2025, all young Europeans finishing upper secondary education have a good knowledge of two languages, in addition to their mother tongue(s)” (EC, 2017, p. 13). The idea of “teaching at least two foreign languages from a very early age” came forth in the Barcelona Objective (EC, 2002, p. 19), where, in the move towards a “competitive economy based on knowledge” (ibid), foreign language competence for the first time was linked to sustainable economic growth.

The choice of foreign languages to master becomes an issue, however. Already in 2012, English was the most widely spoken foreign language in all but six EU member states, excluding the English speaking countries (EC, 2012, p. 11). Today, although the urge is to “[s]upport the diversity of the language offer in schools, going beyond English” (EC, 2018b, p. 14), the first foreign language in most EU countries is still English, and the number of students learning the second foreign language at upper secondary level for their leaving certificate is declining (ibid., p. 6-7). Despite its pledge to support linguistic and cultural diversity, the very idea of the European Education Arena suggests a preferential treatment of major languages (English in particular).

Further, rampant internationalisation with global rankings of universities as a crucial impact factor has brought the issue of competitiveness to the forefront and made English the crowned language of higher education (further HE) and science. Introduced in 1987, the ERASMUS programme turned on the tap of international student mobility, but it was the standardisation of EU degree programmes under the Bologna process which opened the floodgates of academic mobility of both students and university staff and created the European Higher Education Area (further EHEA). All HE policies ever since have essentially aimed at removing obstacles to borderless HE of Europe, and even though the Bologna declaration (1999) did not expand on language preferences, most EU universities predictably turned to English as a common language, attracting international students and facilitating the recruitment of international teaching staff (Wächter & Maiworm, 2014).

Not going into further detail, the analysis of EU language management points to the overall emphasis on foreign language learning, with English as an implicit lingua franca in education and science. Since all strategic solutions transpiring from the EHEA objectives are left to the countries’ discretion, Latvian language policy is to be analysed further.

Language policy in Latvia

Latvian, the only official language in the country, is the cornerstone of Latvian identity – “[t]he fundamental national treasures are the country’s national culture and the Latvian language” (NDP 2020, 2012, p. 8). In the age of multilingualism and mobility, however, the viability of a medium-sized language community close to the lowest threshold of one million speakers requires special language management (Vila, 2012). Having found itself “in the new delicate demographic situation” (Rozenvalde, 2018, p. 61) with a disproportionately high number of Russian speakers, post-Soviet Latvia has been putting a considerable effort to re-establish and maintain the status and sociolinguistic functionality of the Latvian language (ibid.). Acknowledging the threat of “languages of high market value,” Guidelines for State Language Policy 2015-2020 (Cabinet of Ministers, 2014) focus on maintaining competitiveness of the Latvian language and require other planning documents to ensure the component of the official language policy.

The National Development Plan provides the vision of Latvia where “[t]he strength of the nation will lie in the inherited, discovered and newly created cultural and spiritual values, the richness of language and knowledge of other languages” (NDP 2020, 2012, p. 3; the same wording in the upcoming NDP 2027, 2019, p. 5). The Plan stands on three priorities, namely, the growth of the national economy, human securitability and growth for regions. The growth of the national economy is a top priority for any country, and one of the ways to achieve it presupposes commercialisation of knowledge, hence state support of higher education export, fundamental and applied research. The Latvian language, in turn, is safeguarded through the prioritisation of research in Latvian studies and national identity (NDP 2020, 2012, p. 30; also Cabinet of Ministers, 2014, p. 22).

“[T]o ensure the development and sustainability of the Latvian language as the only official language” (Cabinet of Ministers, 2014, p. 5), the focus is not limited to its research. The official language education policy is another action direction laid down for the achievement of the objective (ibid., p. 22). Even expanding the export of HE, study programmes are to be provided “primarily in Latvian and [only then] in one of the official languages of the European Union” (NDP 2020, 2012, p. 5). Nevertheless, a further move towards internationalisation supported by Cohesion Policy funds and the state budget is in creating programmes in EU languages, “international publicity of the programmes and development of support centres for foreign students [as well as] recruitment of foreign instructors” (ibid., p. 31).

While strengthening the position of the Latvian language in public and private realms, the state concurrently attempts to increase the average multilingual competence through the national education system. So, foreign language skills are put at the level of communication, technological, and other 21st century skills (NDP 2020, 2012, p. 43-44), and their development is foreseen at all stages of education. Thus, “upon entering school children are given the foundations for responsible behaviours, creative and well-developed logical thinking and the knowledge of at least one foreign language” (ibid., p. 8). The compulsory secondary education, both general and vocational, stands on three pillars, which are “intensive acquisition of Latvian, foreign languages and information technology” (ibid., p. 6), with sights set on fluency in two foreign languages (Latvija2030, 2010, p. 36). In its turn, adult education is to be equipped with “contemporary methods of foreign language acquisition” (NDP 2020, 2012, p. 45) and people of retirement and pre-retirement age should be provided possibilities to develop their “skills of using information and communication technologies and language skills” (Latvija2030, 2010, p. 31).

Thus, the analysis of national language policy points to the existing dichotomy of the “protectionist” policy in respect of the state language and pragmatic considerations concerning foreign language skills in general as well as English as “the” foreign language in particular. Since the interest of the current analysis is in the development of English language proficiency of educators, the instruments of foreign language management at school and university are to be discussed in more detail.

Language policy: Latvian school

The importance of multilingual skills is evident in the school curriculum. Thus, to qualify for a Certificate in General Secondary Education, students must pass four centralised exams, including both in the Latvian language and a foreign language of choice. Although the Education Law (Izglītības likums, 1998) and General Education Law (Vispārējās izglītības likums, 1999) regulating the teaching of foreign languages in the education system of Latvia do not prescribe two foreign languages at school, the second foreign language is listed as a compulsory subject in the state general education standards. Furthermore, with the introduction of “a competence-based approach, in a uniform system and successively at all levels of education, starting from the age of one and a half and up to grade 12” (IZM, 2020), the reform “School 2030” significantly changes the relative share and vision of the language block of the curriculum.

The process of implementation started from pre-schools in the academic year 2019-2020; next, the improved curriculum was introduced in grades 1, 4, 7 and 10 in the following academic year. For basic education (Grades 1-9), it means more emphasis on language as a system of communication. Now the second foreign language is to be learnt from Grade 4 instead of Grade 6 as before – the shift is bolstered by research claiming that up to the age of 10 children acquire foreign languages “naturally.” However, school administration receives more freedom, and the total amount of classes envisaged for foreign languages can be distributed among first and second foreign languages at a school’s discretion (Skola 2030, 2020a).

For secondary schools, the changes are even more palpable. To begin with, newly introduced “specialised” elected courses might be developed in any of the EU languages. Learning content may be acquired at three levels, namely, basic, optimum, and advanced, and the state examinations are administered correspondingly. The optimum level is the prerequisite for enrolling to a HE programme (Skola 2030, 2020c). Whereas the second foreign language (English, German, French or Russian) may be studied at any level, the first foreign language (the same set minus Russian) should be no less than of the optimum level. The stress is on multilingual competence (EC, 2018a, p. 8), mediation and applicability, as well as educational provision for most proficient students (Skola 2030, 2020b). Such advancement calls for corresponding teacher competencies, though the need is not self-evident, and the requirements are vaguely defined.

In “Education Development Guidelines 2014-2020” (Saeima, 2014), special attention is paid to motivation and professional capacity of teachers, but not enough heed to their multilingual competence. One of the related measures is the advancement of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), the methodology with the underlying principle of “all teachers are teachers of language.” Next is the support to E-Twinning projects, the European Council initiative to enhance international co-operation between teachers by promoting the acquisition of foreign languages and developing ICT skills as part of everyday life in the classroom (Saeima, 2014, p. 28).

The lack of foreign language competence has been an acknowledged problem in teachers’ education, with the acquisition of foreign languages having been set for inclusion in professional competence development programmes (Saeima, 2014, p. 87). While the Latvian language proficiency level C1 is uniformly required of all teachers, the Professional Standard for Teachers (Skolotājs. Profesijas standarts, 2018) is vague on the foreign language competence. The objective is to communicate and be able to express and justify one’s opinion in at least one of the EU official languages, with the foreign language competence in their professional field being at least B2 in the first foreign language and A2 in the second one, respectively. Further, the recent “Regulations on Teachers’ Education and Professional Qualifications and Procedures for the Improvement of Teachers’ Professional Competence” (Cabinet of Ministers, 2018) do not contain a word on language requirements, therefore continuing the trend which has been described as weak strategic planning for the professional development of teachers on the national level (Zeiberte, 2012). According to the aforementioned Regulations (2018), teachers themselves are responsible for the choices made in regard to their professional development, which they do in cooperation with their school administration, as long as the total of 36 hours of in-service training is completed within 3 years. While the quantitative indicator is clearly stated, content requirements are not specifically defined.

Overall, the analysis of regulatory documents related to teacher professional activity in general and professional development in particular leads to a conclusion that foreign language proficiency of schoolteachers depends on their self-determination and existing supply of in-service training rather than on strategic planning and nationwide standard.

Language policy: Latvian tertiary education

In the tertiary education of Latvia, the national policy often conflicts with the demand for internationalisation; hence, the situation in the sector is significantly different from the one found in schools.

The Law on Higher Education Institutions (Augstskolu likums, 1995) promotes the cultivation and development of the Latvian language as one of the tasks of HE (5.1), with no more than one-fifth of a programme in EU languages (56.2). Study programmes not implemented in the official language are strictly regulated, and they are special language and cultural studies and language programmes (56.3), programmes meant for foreign students in Latvia and those “implemented within the scope of co-operation provided for in European Union programmes and international agreements” (56.1). Further, the results of research and artistic creation works must be published in the official language, and the materials “may also be published in other official languages of the European Union” (62.2, 63.2). In respect of staff, the law presents the nomenclature but does not detail the requirements, including language competence, making it part of self-governance of HE institutions (further HEI). Likewise continuing the professional development (further CPD) of university staff is entitled to 160 undefined hours in 6 years (the election period) and left to the HEI’s discretion (Cabinet of Ministers, 2018).

In the sector of HE, “Education Development Guidelines 2014-2020” envisage “attracting human resources, strengthening both the capacity of Latvian academic staff and attracting foreign teaching staff, which will improve the competitiveness of higher education and promote internationalization” (Saeima 2014, p. 28, see also p. 115; translation and italics by the authors). Under the actions to reduce the dropout rate, there is also listed the “development of excellent study programmes in foreign languages” (ibid., p. 115). In line with the above, a new model for financing tertiary education was proposed by the World Bank and endorsed by the Cabinet of Ministers in 2015. Next year’s agreement between the World Bank and the Ministry of Education and Science was signed “to increase [HE] quality, internationalisation and labour market relevance” (OECD, 2017, p. 18; authors’ italics). The interim report on the implementation of the Guidelines in the period between 2014-2017 lists Erasmus+ strategic partnership, mobility, 14 joint study programmes with foreign universities as well as pre-planned co-operation between Latvian higher education institutions for developing study programmes in EU languages (IZM, 2019a, p. 31). Next is a binding distinction of the Academic Information Centre, Latvian coordination point for referencing national qualifications framework to the EQF: in 2018, it entered the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education and joined the European Quality Assurance Register for Higher Education. Further, the programme for retaining homeborn researchers and attracting foreign ones has remained among the top priorities for social development, economic growth and securitability (NDP2027, 2019), and as such directly concerns HEIs.

To enable benchmarking, the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Latvia signed the Agreement on Good Practice of Attracting International Students and Delivering Studies with the accredited HEIs in Latvia (IZM, 2017). To ensure the quality of international study programmes, the preferable level of English or any other implementation language is C1 (5.1.), and “not only university lecturers and employees of the relevant department/service, but also other staff of the higher education institution, including technical staff [have to] have a relevant level of knowledge of foreign language (English)” (5.2.). To sum it all up, competitiveness and internalization are key words, with further progress logically requiring high foreign/English language competence of academic staff.

In Latvia, HE multilingualism officially embraces the official and EU languages, but a closer look reveals that, in fact, the only foreign language to be mastered is English. Thus, the website “Study in Latvia” established by the State Education Development Agency of Republic of Latvia to promote study programmes in EU languages lists 40 Bachelor level study programmes with only 2 of them delivered in other than the English language, namely, the academic programmes of French and German Philology, 1 Master level study programme in German, while there are no non-English Doctoral study programmes meant for foreign students (StudyinLatvia, n.d.).

The improvement of English language competence of university personnel becomes a growing concern (see Bicjutko & Odina, 2018), and there has been a recent attempt to turn the tide nationwide with the EU-funded project under specific objective 8.2.2 “To strengthen academic staff of higher education institutions in strategic specialisation areas” of the Operational Programme “Growth and Employment” (EsFondi.lv). The project gave 6 biggest universities of Latvia an opportunity to offer English language courses for their staff among other short-term CPD programmes. The situation however is tense, for the C1 level is unachievable for a large part of academic personnel, and the recently failed attempt of the Ministry of Science and Education to make that all doctoral theses be written and defended in English (IZM, 2019b) has not been really encouraging.

Thus, although the final say essentially belongs to HEIs, the language management at the national level favours English in promoting their internationalisation and competitiveness.

Understanding professional development of educators through activity systems analysis

Modelling of the activity systems

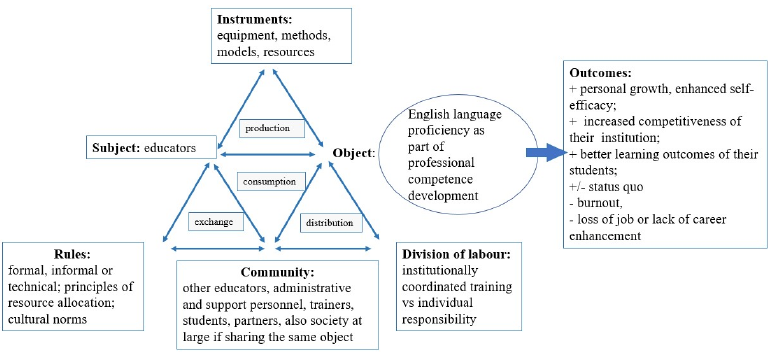

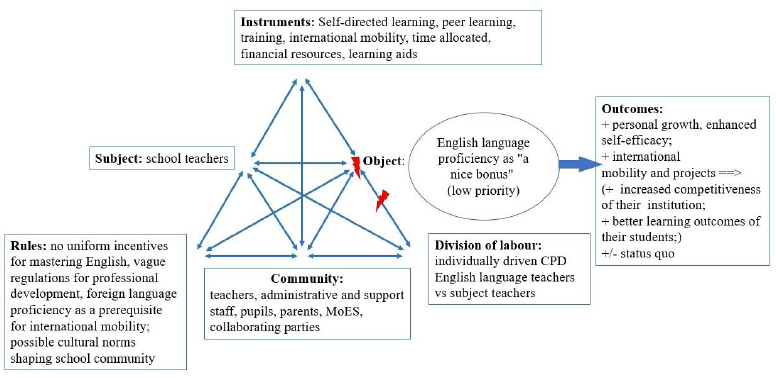

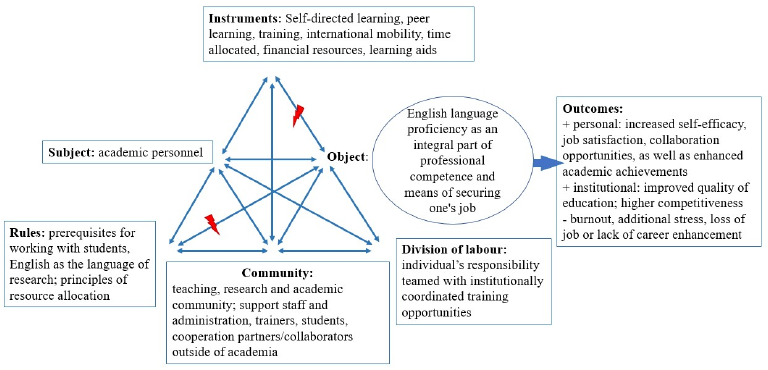

To codify the impact of the foreign language policy on schoolteachers and academic personnel in CHAT terms, the components/parts of activity systems must be identified (see Fig. 1). Thus, the core elements of the model are the subject (educators) who guides their actions toward an object (English language proficiency) representing the “problem space” (Engeström & Sannino, 2010) or “horizon of possibilities” and carries a motive or a need (Engeström, 1987) or contains a purpose (Yamazumi, 2007). The interaction of the subject with the object is mediated using instruments (physical or psychological resources such as equipment, programmes, conceptual models etc.) and leads to outcomes. Subject, object and instruments form a sub-triangle of production, which is socially and historically situated.

Production is also socially situated, and the community, composed of individual and collective stakeholders, shares the same object/outcomes with the subject, thus, forming the sub-triangle of consumption. Division of labour characterises how tasks as well as mandate, power and status are distributed, and hence is the sub-triangle of distribution. Actions within the activity system are steered and confined by rules, which together with subject and community form the sub-triangle of exchange (Engeström, 1987; Engeström & Sannino, 2010).

Figure 1. General model of the activity system of English language proficiency development of educators (adapted from Engeström (1987))

Each sub-triangle may potentially be regarded as an activity on its own, and the elements have a new role in a neighbouring activity. For example, language proficiency is part of professional development of educators, and as such it is a tool in a “neighbouring” system. As “[t]he model suggests the possibility of analysing a multitude of relations within the triangular structure of activity [...], the essential task is always to grasp the systemic whole, not just separate connections” (Engeström 1987, p. 62). Thus, the aim is not to fix all occurrences and separate actions of English language proficiency development within the model (following Barab et al., 2002), but to unfold the inherent dynamics and characterise the inevitably occurring tensions and contradictions among the elements of the activity systems for schoolteachers and academic personnel, and, consequently, see the differences between activity systems themselves. The previous document analysis informs both modelling activity systems and making conclusions based on their analysis.

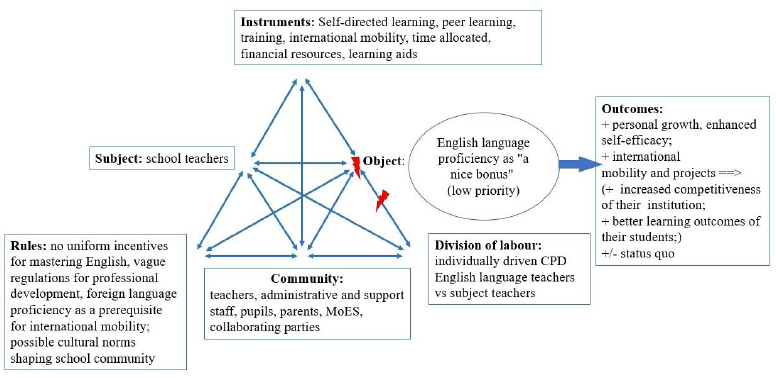

Analysis of the activity systems: School teachers

First is the analysis of the development of English language proficiency of teachers in Latvia (Figure 2). As far as foreign languages are concerned, English is of low priority due to its seldom use in teachers’ daily work, with the exception of English language teachers (division of labour). This marks the contradiction in the system (marked by a lightning bolt) between object and division of labour. Since English language proficiency is mostly regarded as a “nice bonus,” the majority of the teacher population has no strong motive or purpose for enhancing it, which constitutes an inner contradiction of the object hampering the activity itself. The contradiction is partly mitigated by the incentives of desired outcomes such as international mobility via exchange programmes and projects, a larger pool of accessible teaching resources etc. Additionally, the status quo is endangered with the introduction of CLIL. However, the division of labour, i.e., the existence of English language teachers, eases the tension and allows to rely on the cumulative pool of teaching competencies within a school community as “[t]he range and complexity of competences required for teaching in the 21st century is so great that any one individual is unlikely to have them all, nor to have developed them all to the same high degree” (EC, 2013, p. 8). Furthermore, the school community comprises parents, entrepreneurial local community members, Ministry of Education and Science (MoES) and collaborating organisations, and none of them systematically stimulates teachers to move towards the object and, consequently, outcomes. As far as systemic rules are concerned, there are no direct incentives from above, although some might be introduced by the school board as well as changed cultural norms could make the outcomes more desirable. CLIL seems to be another move in the right direction, when the desired outcome is reached through exchange; moreover, it has an additional benefit of enhanced learning outcomes.

Figure 2. Model of activity system of English language proficiency development of school teachers (adapted from Engeström (1987))

However, any administrative measures should be implemented with caution so as not to cut English language proficiency off its living context and set it as a dead object, in Engeström’s terms. When mastery turns into an aim in itself rather than a utile satisfier of needs (Engeström, 2008), the purposefulness of enhancing the foreign language stays only within the encapsulated school environment and ceases to exist outside.

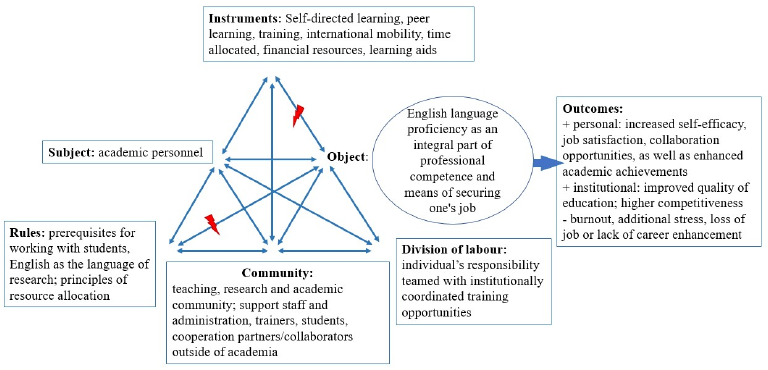

Analysis of the activity systems: Academic personnel

The activity system of English language proficiency development of academic personnel shows a different picture (Figure 3). The object of the activity is well articulated, as English language proficiency is a direct prerequisite for securing one’s job and performing professional duties such as carrying out research projects, participating in conferences and being part of international mobility. Due to internationalisation policies, a growing number of international students are to be taught and it creates a community push towards English Medium Instruction as well as more incentives for academic personnel to develop their English language skills. English language proficiency brings many desirable outcomes, such as enhanced academic achievements and higher competitiveness; alternatively, a lack thereof negatively affects one on both personal and institutional levels, the outcomes ranging from insecurity to the threat of unemployment.

Figure 3. Model of activity system of English language proficiency development of academic personnel (adapted from Engeström (1987)

HE internationalisation increases the demand for fluency in English, and the language proficiency of educators becomes not only an individual HEI’s concern. While institutionally provided and individually allocated instruments, i.e., language courses meet the demand, the limited time of provision as well as the overall lack of time and a big working load (Bicjutko & Odina, 2018; Shagrir, 2017) hamper the personnel’s professional development and may pose negative outcomes. Therefore, contradictions in the system may be identified in the form of (1) inappropriateness or the lack of instruments for reaching the object as well as (2) systemic rules that impede language studies (issues of resource allocation, i.e. scheduling, and excessive institutional pressure resulting in high levels of anxiety).

Conclusion

Primed by the study of European and national strategic and regulatory documents, the bifurcated activity systems analysis conducted to examine how the EU foreign language policy eventually impacts the development of English language proficiency of teachers and teacher educators allows for a number of conclusions, warnings and tentative recommendations.

1. Given the hegemonic position of English in EU multilingual and LV foreign language management, schoolteachers and academic staff are not equally incentivised to enhance their English language proficiency.

2. In Latvia, HE language management is in search of a compromise between a protectionist language policy and rampant internationalisation.

3. Whereas HEIs are driven to promote English and become more competitive, schools are rated locally and serve as strongholds of traditional values. The activity systems analysis further reveals the systemic conditions differing for schoolteachers and academic staff.

• While English language proficiency may be considered a “nice bonus” for teachers, it is an absolute necessity for the faculty; thus, the amount of pressure differs significantly.

• Although the range of instruments to improve English does not differ significantly, the CPD provision for HEI personnel is better.

• Despite palpable benefits for schoolteachers, the object carries higher stakes for HEI staff and possible outcomes greatly differ.

• Despite the self-governance of HEIs and the institutional dependence of schools, existing policies indirectly impose stricter rules (external motivation) on HEI staff and set no systemic requirements to non-foreign language teachers.

• The majority of the HEI community are directly interested in English language proficiency, whereas the school community can be generally regarded as disinterested.

• While academic staff should react individually and collectively or institutionally to the growing demands for English language competence, school teachers may use the division of labour, with language teachers covering for the existing tension.

To summarise, the analysis revealed the difference in contradictions as well as varying degrees of motivation towards the object for two types of subjects within one education system – the high external pressure on HE personnel and lack of motivation and support of teachers towards their English language enhancement. If foreign language competence is seen as a token of country development, the revealed discrepancy points to a gap between two levels of the education system and, as any gap, it negatively affects the functioning of the system as a whole. In terms of solutions, closer collaboration between school and university such as joint research projects might additionally incentivise teachers. However, for a clearer picture of policy development and implementation, both systemic level and individual perspective should be considered. In understanding the individual (subject’s) perspective, the motive of action takes an important role, shaping the object of the activity and the agency of the subject. As the institutional pressure leads to the loss of agency and threatens well-being of staff, policy makers should remember that preferring the culture of control to the culture of trust leads towards a dead object rather than towards agency building. However, the reverse is true if an individual’s perspective is considered alongside the systemic one.

References

Augstskolu likums [Law on Higher Education Institutions]. (1995). Adopted 02 November 1995, Saeima, Republic of Latvia. Retrieved from https://likumi.lv/ta/id/37967-augstskolu-likums

Barab, S. A., Barnett, M., Yamagata-lynch, L., Squire, K., Barab, S. A., Barnett, M., … Keating, T. (2002). Using Activity Theory to Understand the Systemic Tensions Characterizing a Technology-Rich Introductory Astronomy Course. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 9(2), 76–107. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327884MCA0902

Behrend, M. B. (2014). Engeström’s activity theory as a tool to analyse online resources embedding academic literacies. Journal of Academic Language & Learning, 8(1), 109–120. Retrieved from https://journal.aall.org.au/index.php/jall/article/view/315

Bicjutko, T., Odina, I. (2018). Language Policy and Language Needs of Academic Personnel: the Case of the University of Latvia. In O. Titrek, A. Zembrzuska, G. S.-G. Sakarya (eds.). 4th International Conference on Lifelong Education and Leadership for all (ICLEL 2018): Conference proceeding book (pp.567-574). Retrieved from https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/d546b1_20f8aff367a6467285d6d8aa7aaa3a8a.pdf

Blayone, T.J.B. & VanOostveen, R. (2020) Prepared for work in Industry 4.0? Modelling the target activity system and five dimensions of worker readiness. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951192X.2020.1836677

Bligh, B. & Flood M. (2017). Activity theory in empirical higher education research: Choices, uses and values. Tertiary Education and Management, 23(2), 125-152. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2017.1284258

Bologna Process Committee. (1999). Joint declaration of the European Ministers of Education convened in Bologna on 19 June 1999. (The Bologna Declaration). Retrieved from https://www.eurashe.eu/library/modernising-phe/Bologna_1999_Bologna-Declaration.pdf

Cabinet of Ministers. (2014). On Official Language Policy Guidelines for 2015-2020. Order No. 630, adopted 3 November 2014, Cabinet of Ministers, Republic of Latvia. Retrieved from https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/270016

Cabinet of Ministers. (2018). Noteikumi par pedagogiem nepieciešamo izglītību un profesionālo kvalifikāciju un pedagogu profesionālās kompetences pilnveides kārtību. [Regulations on Teachers’ Education and Professional Qualifications and Procedures for Improvement of Teachers’ Professional Competence]. Order No. 569, adopted 11 September 2018, Cabinet of Ministers, Republic of Latvia. Retrieved from https://likumi.lv/ta/id/301572/redakcijas-datums/2018/09/14

Council of the EU. (2017). The Rome Declaration. Declaration of the leaders of 27 member states and of the European Council, the European Parliament and the European Commission. Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2017/03/25/rome-declaration/pdf

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

Engeström, Y. (2000). Activity theory as a framework for analyzing and redesigning work. Ergonomics, 43(7), 960–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/001401300409143

Engeström, Y. (2008). Crossing boundaries in teacher teams. In From teams to knots: Activity-theoretical studies of collaboration and learning at work (pp. 86–117). Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. (2009). Expansive learning: Toward an activity-theoretical reconceptualization. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists in Their Own Words (pp. 53–73). New York: Routledge.

Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educational Research Review, 5(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

EsFondi.lv (n/a). ES fondi 2014 - 2020. Retrieved from https://www.esfondi.lv/es-fondi-2014---2020

European Commission (EC). (2002). Presidency conclusions. Barcelona European Council 15 and 16 March 2002. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/PRES_02_930

European Commission (EC). (2012). Europeans and their Languages. Report. Special Eurobarometer 386. Retrieved from https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/f551bd64-8615-4781-9be1-c592217dad83/language-en/format-PDF/source-119658026

European Commission (EC). (2013). Supporting Teacher Competence Development for Better Learning Outcomes. European Commission, Education and Training. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgt077

European Commission (EC). (2017). Study on foreign language proficiency and employability. Final Report. Brussels. https://doi.org/10.2767/908131

European Commission (EC). (2018a). Council Recommendation of 22 May 2018 on key competences for lifelong learning. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018H0604(01)&from=EN

European Commission (EC). (2018b). Proposal for a Council Recommendation on a comprehensive approach to the teaching and learning of languages. Retrieved from http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-9229-2018-ADD-2/EN/pdf

European Commission (EC). (2018c). The European Education Area. Report. Flash Eurobarometer 466. Retrieved from https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/3dbc3537-ebf9-11ea-b3c6-01aa75ed71a1

European Commission (EC). (2019). Council Recommendation of 22 May 2019 on a comprehensive approach to the teaching and learning of languages. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2018%3A272%3AFIN

Izglītības likums [Education Law]. (1998). Adopted 29 October 1998, Saeima, Republic of Latvia. Retrieved from https://likumi.lv/ta/id/50759

Izglītības un zinātnes ministrija (IZM). (2017) Agreement on good practice in attracting foreign students. Retrieved from https://www.izm.gov.lv/en/agreement-on-good-practice-in-attracting-foreign-students

Izglītības un zinātnes ministrija (IZM). (2019a). Par Izglītības attīstības pamatnostādņu 2014.–2020.gadam īstenošanas 2014.-2017.gadā starpposma novērtējumu. Informatīvais ziņojums [On an interim assessment of the implementation of the 2014-2017 Education Development Guidelines for 2014-2020. Informative report]. Retrieved from https://www.izm.gov.lv/lv/sabiedribas-lidzdaliba/sabiedriskajai-apspriesanai-nodotie-normativo-aktu-projekti/3337-informativais-zinojums-par-izglitibas-attistibas-pamatnostadnu-2014-2020-gadam-istenosanas-2014-2017-gada-starpposma-novertejumu

Izglītības un zinātnes ministrija (IZM). (2019b). Turpinās darbs pie doktora studiju pilnveides modeļa [Work on the doctoral study improvement model continues]. Published on 19 November 2019. Retrieved from https://www.izm.gov.lv/lv/aktualitates/3770-turpinas-darbs-pie-doktora-studiju-pilnveides-modela

Izglītības un zinātnes ministrija (IZM). (2020). Description of Educational Curriculum and Learning Approach. News of 25.01.2020. Retrieved from https://www.izm.gov.lv/en/highlights/3336-description-of-educational-curriculum-and-learning-approach-2

National Development Plan 2021-2027: Summary. (The version submitted for public consultation on October 7, 2019) (NDP2027). (2019). Riga: Cross-Sectoral Coordination Centre (CCSC). Retrieved from https://www.pkc.gov.lv/sites/default/files/The%20Latvian%20National%20Development%20Plan%202021-2027%20-%20Summary_pdf_1.pdf

National Development Plan of Latvia for 2014–2020 (NDP 2020). (2012). Riga: Cross-Sectoral Coordination Centre (CCSC). Retrieved from https://www.pkc.gov.lv/images/NAP2020%20dokumenti/NDP2020_English_Final.pdf

Mentz, E. & De Beer, J. (2019). The use of Cultural-Historical Activity Theory in researching the affordances of indigenous knowledge for self-directed learning. In De Beer, J. (Ed.) The decolonisation of the curriculum project: The affordances of indigenous knowledge for self-directed learning. NWU Self-directed Learning Series Volume 2 (pp.49-86). Cape Town: AOSIS.

OECD. (2017). Education Policy Outlook: Latvia. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/Education-Policy-Outlook-Country-Profile-Latvia.pdf

Leech, P. (2017). European policy on multilingualism: Unity in diversity or added value? Cultus, 10(1), 27-38. Retrieved from https://www.cultusjournal.com/files/Archives/Cultus-_10_Patrick-Leech.pdf

Rozenvalde, K. (2018). Multilayered Language Policy in Higher Education in Estonia and Latvia: Case of National Universities. (Doctoral Thesis, University of Latvia). Riga: LU Akadēmiskais Apgāds. Retrieved from https://luis.lu.lv/pls/pub/luj.fprnt?l=1&fn=F1031182997/Rozenvalde_Kerttu_kk11232.pdf

Saeima. (2014). Par Izglītības attīstības pamatnostādņu 2014.–2020.gadam apstiprināšanu. [On the Approval of the Education Development Guidelines for 2014-2020]. Notice of 22 May 2014, Saeima, Republic of Latvia. Retrieved from https://likumi.lv/ta/id/266406

Shagrir, L. (2017). Teacher Educators’ Professional Development: Motivators and Delayers. In Teachers and Teacher Educators Learning Through Inquiry: International Perspectives (pp.159-180). Kielce-Krakow: Jan Kochanowski University.

Skola 2030. (2020a). Pamatizglītība [Basic Education]. Retrieved from https://www.skola2030.lv/lv/skolotajiem/izglitibas-pakapes/pamatizglitiba

Skola 2030. (2020b). Valodas [Languages]. Retrieved from https://www.skola2030.lv/lv/skolotajiem/macibu-jomas/valodas

Skola 2030. (2020c). Vidusskola [Secondary School]. Retrieved from https://www.skola2030.lv/lv/skolotajiem/izglitibas-pakapes/vidusskola

Skolotājs. Profesijas standarts. [Teacher. Professional Standard]. (2018). Retrieved from https://visc.gov.lv/profizglitiba/dokumenti/standarti/2017/PS-048.pdf

Spolsky, B. (2004). Language Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511615245

Spolsky, B. (2009). Language Management. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511626470

Study in Latvia. (n.d.) Study programmes. Retrieved from http://www.studyinlatvia.lv/study-programmes

Sustainable Development Strategy of Latvia until 2030 (Latvija2030). (2010). Adopted 10 June 2010, Saeima, Republic of Latvia. Retrieved from http://www.varam.gov.lv/lat/pol/ppd/?doc=13857

Trajectory Partnership. (2018). The Future Demand for English in Europe: 2025 and beyond. A report commissioned by the British Council March 2018. Retrieved from https://www.britishcouncil.org/education/schools/support-for-languages/thought-leadership/research-report/future-of-english-eu-2025

Vila, X. (ed). (2012). Survival and Development of Language Communities: Prospects and Challenges. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Vispārējās izglītības likums [General Education Law]. (1999). Adopted 10 June 1999, Saeima, Republic of Latvia. Retrieved from https://likumi.lv/ta/id/20243

Wächter, B. & Maiworm, F. (Eds.). (2014). English-Taught Programmes in European Higher Education. The State of Play in 2014. ACA Papers on International Cooperation in Europe. Bonn: Lemmens. Retrieved from http://www.aca-secretariat.be/fileadmin/aca_docs/images/members/ACA-2015_English_Taught_01.pdf

Yamagata-Lynch, L. C., & Haudenschild, M. T. (2009). Using activity systems analysis to identify inner contradictions in teacher professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(3), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.014

Yamazumi, K. (2007). Human agency and educational research: A new problem in activity theory. Actio: An International Journal of Human Activity Theory, 1(1), 19–39.

Zeiberte, L. (2012). Pedagogu tālākizglītības pārvaldība nepārtrauktas profesionālās pilnveides nodrošināšanā. [Teachers’ further education management for continuous professional development.] (Doctoral Thesis, University of Latvia). Riga: LU Akadēmiskais Apgāds. Retrieved from https://luis.lu.lv/pls/pub/luj.fprnt?l=1&fn=F-1185553089/Livija Zeiberte 2012.pdf