Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2021, vol. 46, pp. 54–72 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2021.46.4

Institutional Influence of Academics in Argentinean Public Universities in a Context of External Control

Mónica Marquina

Interdisciplinary Nucleus of Training and Studies for Educational Development (NIFEDE),

National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET),

Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina

mmarquina@untref.edu.ar

Cristian Pérez Centeno

NIFEDE, Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina

cpcenteno@untref.edu.ar

Nicolás Reznik

Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Argentina

nicoreznik@gmail.com

Abstract. The paper studies the institutional influence of academics in Argentina within a context of increasing external control as a consequence of deep public reforms in the Higher Education system. Drawing on data from the Academic Profession in the Knowledge-Based Society (APIKS) survey, the aim is to analyse how much and in what sense the recent changes on the public policy level and the intermediate level of the state agencies have affected the academic profession in Argentina over teaching, research and social engagement activities, and its effects over the perception of institutional influence. Although we assume that academic power has been reduced within the new scenario, we believe that not all academics have responded in the same manner.

Keywords: University – Academic Profession – Argentina – Peer reviewers – Academic influence.

Argentinos valstybinių universitetų mokslininkų ir dėstytojų įtaka institucijai išorės kontrolės kontekste

Santrauka. Straipsnyje nagrinėjama Argentinos mokslininkų įtaka savo institucijai dėl gilių visuomenės reformų aukštojo mokslo sistemoje didėjančios išorės kontrolės kontekste. Remiantis Akademinės profesijos žinių visuomenėje (angl. APIKS) apklausos duomenimis siekiama išanalizuoti, kiek ir kaip pastarojo meto pokyčiai viešosios politikos ir valstybinių agentūrų lygmeniu paveikė akademinę profesiją Argentinoje – dėstymą, mokslinius tyrimus ir socialinio įtraukimo veiklas ir šių pokyčių įtaką suvokiant savo instituciją. Nors bendrai tikima, kad naujasis scenarijus sumažino akademinės bendruomenės galias, mūsų tyrime ne visi mokslininkai ir dėstytojai atsakė vienodai.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: universitetas, akademinė profesija, Argentina, recenzentai, akademinė įtaka.

Acknowledgements:

Received: 30/09/2020. Accepted: 20/03/2021

Copyright © Mónica Marquina, Cristian Pérez Centeno, Nicolás Reznik

Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to study the institutional influence of academics in Argentina within a context of increasing external control from the government over their academic activity. Indeed, higher education in Argentina has experienced deep reforms since the mid ´90s, based on a public policy agenda for universities oriented to higher efficiency and effectiveness. The reforms have transformed the relation of universities to the state.

The new agenda has created new rules to institutions and to academic work, based on quality assurance mechanisms and project-based or performance-based funding programmes. For these purposes, Argentina has followed similar trends of developed countries, with the creation of councils or agencies for competitive funding or for accreditation. These intermediate bodies between the state and institutions involve evaluation of academic activity with the participation of peer reviewers.

We start from a review of the literature that argues over the emergency of a new public policy agenda of higher education towards greater external control of academic work. We analyse how these trends, based on the New Public Management (NPM) approach, manifest in a context like Argentina, with strong collegial tradition and academic freedom. Although we assume that academic power has been reduced within the new scenario, we believe that not all academics have responded in the same manner. Therefore, we focus on the academic institutional influence regarding some structuring features of the academic profession in Argentina.

The aim is to analyse how much and in what sense the changes on the public policy level, and on the intermediate level that has developed with the creation of new state agencies, have affected the academic profession in Argentina, especially in terms of external control over teaching, research and external academic activities, and the consequent perception of institutional influence. We use data from the Academic Profession in the Knowledge-Based Society (APIKS) survey.

Global trends towards “managerialism” in higher education

Several authors have pointed out that European higher education reforms of the last decades are a consequence of the predominance of the NPM paradigm as a new regulatory governance mechanism of public services by state agencies (Hood & Scott, 1996). As Deem & Brehony (2005, p. 220) argue, this shift in the management of public services and their marketisation has “also been accompanied paradoxically by both greater state regulation (...) and fragmentation of service delivery”. The new configurations have meant the inclusion of ideas and practices from the private sector into the world of public service, looking for efficiency and effectiveness (Farrell & Morris, 2003). NPM is also associated with new kinds of external accountability, including the use of performance indicators to verify compliance with objectives and goals (Power, 1997).

By the late 1980s, the impact of the NPM reforms on higher education systems and institutions manifested in the UK, Australia, New Zealand and Canada (Bleiklie & Kogan, 2007). The United Kingdom is one of the best examples of this transformation, aimed directly at the heart of the traditional collegial model of university governance in the context of reforms in the public sector under neoliberal and pro-market national policies during the Margaret Thatcher government (Austin & Jones, 2016).

The reforms in this new context configured new relationships between the state, the academic profession and higher education institutions. New public policies reinforced the role of research councils and evaluation agencies in charge of applying the instruments developed by public authorities to measure scientific performance and selectively allocate resources to link funding to performance. For their part, the new instruments promoted new behaviours and increased productivity and quality (Whitley, 2007).

Intermediary organisations (Van der Meulen and Rip, 1998) or agencies (Christensen & Lægreid, 2005) are part of a principal-agent relation: the ministry (the principal) asks the agencies (agents) to develop specific tasks. Since most of them rely on a peer-based evaluation led by academics, these bodies depoliticise and legitimise government policies by directly linking the results of peer reviews to resources.

The policy agenda has focused particularly on research, but this is not the only academic activity affected. Calls for proposals are also aimed at selectively allocating funds for teaching and technology transfer, as well as evaluation, accreditation, and assessment processes (Schwarz & Westerheijden, 2004). As Musselin points out, these processes are all linked to the rise of an “incentivising” state, which does not prescribe what to do, but develop the rules of a game “which require compliant behaviours if one wants access to funding” (Musselin, 2013, p. 1168) Then, the autonomy given by the state is an illusion, since the incentive-based instruments mean a stronger control over behaviours (Les Galès & Scott, 2010).

The universities – state relation and the shift towards managerialism in Latin America and Argentina

In Latin America, NPM appeared as a new school of thought about the state during the ‘90s, giving birth to “second generation” reforms. While the “first generation of reforms” had been focused on a restructuring of the state and market´s relations (privatisation, decentralisation, deregulation, tax reform, and financial liberalisation), the second set of reforms was aimed at “reinventing government” (Osborne & Gaebler, 1994).

Within this context of reforms, Latin American higher education systems adopted public policies based on World Bank directives, whose patterns aimed at orienting these systems according to a common global agenda. This agenda attempted to act as a response to the processes of massive growth experienced in the region, with policies oriented to growth in the private sector and institutional diversification. The new public policies included the promotion of research productivity and the implementation of quality assurance systems. New state agencies were created for these purposes that gradually influenced the operation of universities, since they were in charge of applying the public policy agenda for universities through performance-based financing instruments, or to ensure compliance with specific standards.

In Argentina, different incentives and regulations were implemented with regard to the academic profession, which began to outline a model for academic work that, until then, was limited only to certain specific disciplines. Peer review systems for the evaluation of teaching, research projects, and grants promoted the establishment of new academic segments that, in practice, started to act as academic elites allocating resources and prestige in the academic profession that is increasingly fragmented (Marquina, 2013).

The National Commission for Evaluation and Accreditation of Universities (CONEAU) was created through the Higher Education Act of 1995. It is in charge of the external evaluation of universities, as well as the accreditation of undergraduate programmes of public interest (Engineering, Medicine, etc.) and all graduate programmes. With this agency, teaching is the main activity under scrutiny. In these processes, participation of peer committees is involved.

The Programme of Incentives to Teachers-Researchers at National Universities involved an additional payment for research productivity performance based on peer–review processes. While this programme is still in place, it now faces the paradox that the financial incentive is almost nonexistent, although another type of symbolic benefit is distributed —prevalence or advancement within a system of researcher categories— in accordance with productivity parameters like the ones used worldwide. Currently, 12.8% of university teachers in Argentina take part in this incentive programme (SPU, 2016) and evaluation is in charge of peer reviewers, as well.

During the ´90s, the National Agency for Science and Technology Promotion (ANPCyT) was also created, which was based on funding instruments directed at supporting research and promoting innovation activities through research grants. These processes also involved the participation of peer reviewers evaluating research and innovation projects.

More recently, since 2006, the Secretariat of University Policies (SPU) has been promoting a set of actions destined to strengthen the relation between the university and the community. These actions involve competitive calls for project submissions headed by professors. Although the funding granted is limited and is meant for annual development, it helps sponsor joint activities between universities and society.

The traditional university model of governance and management in Argentina has its roots in the Córdoba University Reform of 1918. The ideas of academic freedom, autonomy and co-governance among teachers, students, and graduates were set as distinctive features of the Argentinean University and expanded throughout Latin America. Local research suggest that this model was affected by the managerial approach that sustained the university reforms during the ´90s. These changes have produced slow transformations in the internal functioning of universities towards a managerialisation of tasks, including academic ones (Marquina, 2020; Obeide, 2020).

The academic profession in Argentina

The academic profession in Argentina has specific features that differentiate it from developed countries, as well as from other Latin American ones. These traits are strongly related to three characteristics of the higher education system: a) the mass system condition; b) the training of professionals as the main purpose; c) the traditional collegial governance model.

A first characteristic of teachers and researchers of Argentinean institutions is a high presence of part-time faculty. There has been a prevalence of close to two-thirds of part-time teachers (10 hours per week), with an upwards trend in recent years. All of them have permanent employment based on long-term contracts. The other third is distributed among full-time teachers (40 hours per week) and teachers working 50% of a full-time position, who are concentrated in the higher echelons (SPU, 2020). In general terms, research activity and academic management tasks fall within the domain of full timers. Part-time positions concentrate in lowest ranks (in 2017, 60% of junior staff was part-time, and only 32% was full-time). The distribution of full-time positions among academic personnel also varies among disciplines.

In addition, the Argentinean academic profession is strongly hierarchical. The chair system is the most common type of organisation of academic work, especially in more traditional institutions, which also concentrate the largest number of students. Both juniors and senior professors are part of the university chair and play different roles with specific tasks assigned according to rank. Full professors (heads of chairs) design syllabi and give lectures (theory classes), usually large-scale, whereas juniors (the vast majority of teachers) carry out laboratory functions or class work with smaller groups of students and are in direct contact with them.

The relevance of beliefs and academic culture for the understanding of institutional worlds (Clark, 1983) and the effects of governmental steering on the academic culture in recent decades (Maassen, 1996) have been sufficiently studied. These changes can be observed through the analysis of different academic generations, according to the moment of access to and socialisation in the academic career. According to Shaw´s (2008) definition of generation, the aspects of time and space affect the aggregate of subjects’ generations because of their presence in a delineated historical period, as well as the specific processes of socialisation in terms of values, beliefs, attitudes and demands towards academics’ work in higher education institutions.

These considerations are valuable since the public policies affecting the academic profession in Argentina have probably impacted academic activities and socialisation in different ways in terms of generational groups. The new generation accessed the profession and socialised within these new rules, and the oldest generation, that is almost at the end of the academic career, watched the changes without strong stress (Marquina, et. al., 2015), whereas the intermediate generation suffered the transformations and was compelled to adapt to the new rules under the risk of being left behind of the competitive race towards more recognition and higher ranks. Thus, the Argentinean academic profession is diverse in academic cultures that coexist and can be distinguished by generation.

Finally, academics in Argentina have a considerable power, at least formal, in institutional decision-making processes, conferred by the Higher Education Act of 1995. Main institutional authorities - presidents or rectors and deans – are elected by the university community, which is composed of teachers, students, graduates, and in some cases administrative staff organised in claustros (“cloisters” or academic senate), a body made up of teachers, researchers, and graduate students. Teachers - who have at least 50% of the participation as members in the governance bodies - must be senior professors to be elected. These regulations generate a distribution of power inside institutions, and academics make use of that power in a differentiated way. So, it is possible to recognise an academic elite composed by those who meet specific traits, such as, full-time employment, senior rank and/or being a part of older generations.

Questions, analytical model and hypotheses

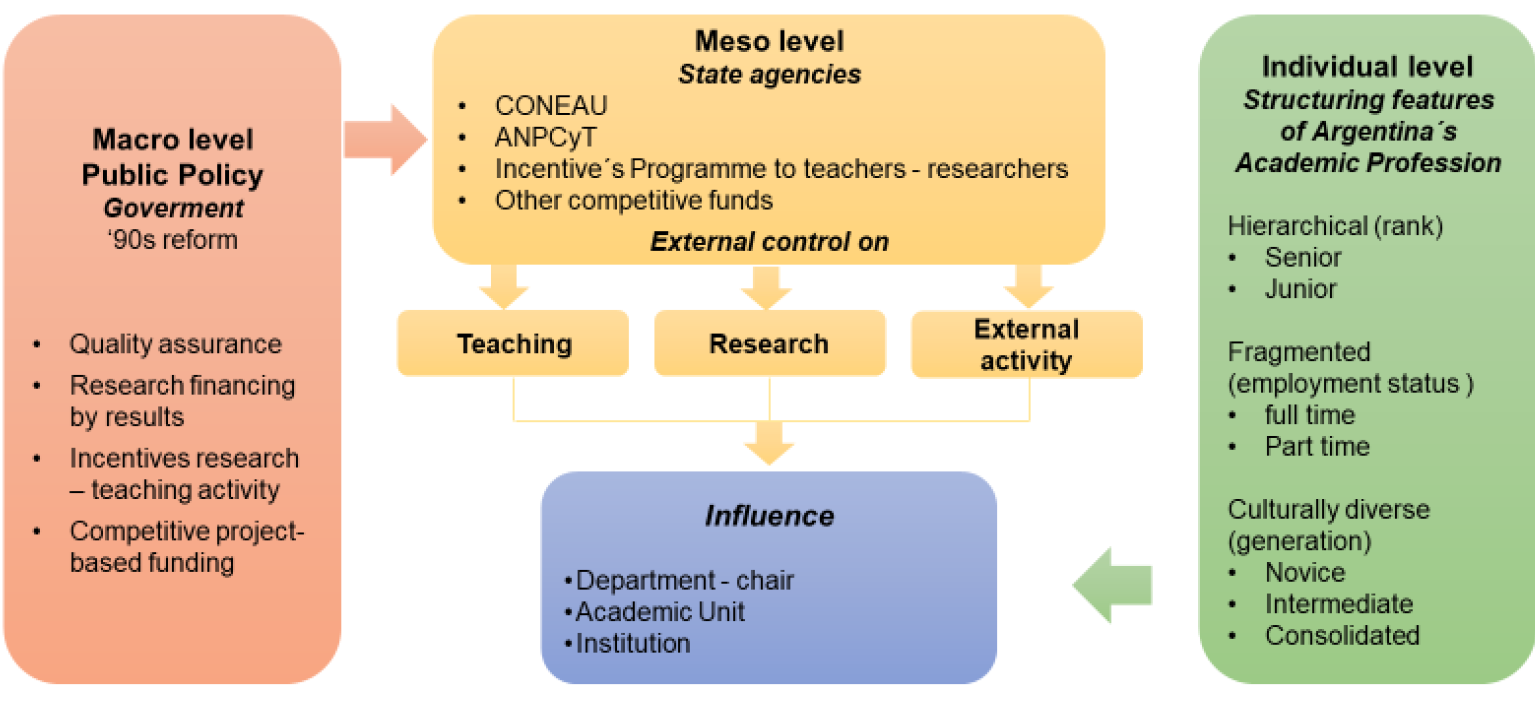

The aim of this work is to analyse how much and in what sense the public policy agenda of the ’90s (macro level), which involved the creation of state agencies in charge of applying specific policy instruments (meso level), has increased the perception of external control over teaching, research and social engagement activities among academics, affecting the perception of their institutional influence, in accordance with some specific structuring features of the Argentinean academic profession (individual level).

Therefore, our questions are:

1. Do academics in Argentina perceive external control over their teaching, research and social engagement academic activities?

2. What is the perception of their influence at different levels of the organisational structure, in a situation of greater or lesser external control over the academic activity?

3. How do these perceptions vary according to specific features of the Argentinean academic profession?

Since we are interested in paying special attention to how these aspects vary according to the structuring features of the profession mentioned, for the purposes of this study, we will consider the following:

a) Hierarchical: Two main ranks, juniors and seniors.

b) Fragmented: Two groups, full-time and part-time academics.

c) Diverse: Three generations of academics, according to key moments of the national policies and the year of access to the first teaching position:

i) Novice: They have accessed the academic career since 2008, have 10 or less years of experience in the profession and are younger than 37 (entered the profession during President Cristina Fernandez’ administration).

ii) Intermediate: They got their first position between 1995 and 2007, are up to about 25 years in the profession and are younger than 50 (entered the profession in the second administration of President Carlos Menem or during Nestor Kirchner´s administration).

iii) Consolidated: They entered the career before 1995, have worked as academics for more than 25 years and are 50 or older (entered the profession during the de facto military government or during the administrations of Raúl Alfonsín or Carlos Menem´s).

We have worked with a three-level analytical model that sustains the hypotheses of this work and the methodological proposal:

Graphic 1: Analytical model for the study of academic institutional influence in the context of external control

According to the model, in a first stage we have worked with three main hypotheses:

H1: Most academics perceive external control over their teaching, research and social engagement activities with emphasis on research.

Due to the increasing instances of academic evaluation from state agencies, academics are required to design projects to obtain external competitive funds for different academic activities. Simultaneously, quality assurance processes, mainly accreditation of programmes, have also imposed new rules that are carefully designed by the state agency. Programmes carried out by professors as programme directors must go through these processes on a periodical basis. We assume that research activity is perceived as being most subject to evaluations, since there are more instruments that not only distribute material resources but also symbolic ones.

H2: The academics’ perception of external control increases with a) the generation, b) the rank and c) the employment status.

The role of director of academic programmes, responsible for the preparation of the accreditation reports, is mainly performed by senior professors with established track records. They receive the specialized support of the accreditation units. Achieving accreditation is a huge responsibility for them, given its impact on the institution and their disciplinary field. They are witnesses of the changes since accreditation processes last between ten to fifteen years. Thus, in our hypothesis we argue that perception of institutional control increases in relation to career trajectory; that is, the older the generation. Nevertheless, academics from newer generations do not perceive this control because they have entered the profession with the new rules already in place.

H3: Argentinean academics perceive that their influence in university decision making is greater: a) the closer is the organisational level; b) the older is the generation, the higher is the rank, and the employment status. c) They perceive their influence is lesser the higher is the perception of external control.

Being elected by their peers as members of collegial bodies means to have reached recognition from colleagues to represent them, based on experience that does not necessarily mean to have political or managerial abilities. That power is the result of a path in which the first steps occur in closer settings (the chair, the department) and extends to the academic unit and to the institution later. It is also reasonable to support the idea that academics perceive themselves as more influential when their academic career has advanced backgrounds. This can be verified by considering the academic generation, as well as the rank and the time they spend at their workplace during the week. Nonetheless, the perception of increasing influence along with academic career progression might be changing with the perception of external control over the work.

Data and methods

The Argentinean APIKS survey was carried out in 2019, with a total of 1.450 responses obtained. We have worked with a total of 954 valid cases after a cleaning and weighting process to ensure the representativeness of the national university system (137.357 people).

The analysis of the hypotheses was based on an analytical model, which allowed us to relate dependent variables to independent ones. In H1 and H2, we analyse only those academics who perceive external control over their teaching, research or external activities (F2_6). The whole sample is considered for the rest of the hypotheses.

For H1, we address the academics’ perception of external control over teaching, research and external activities as dependent variables. The intention is to find out the perception of external control as a whole, and which of these activities are perceived as externally controlled the most. In H2, we also address the academics’ perception of external control with the intention of recognising differences according to three independent variables: generation, rank and employment status. In H3, we study the perception of influence over the Chair/Department, the Academic Unit and the Institution levels in those who perceived themselves as being externally controlled. We also analyse variations by generation, employment status and rank. As explained in Annex, “external control” is measured with question F2_6: “Who evaluates your teaching, research and external activities?”, option “external reviewers”; and “influence” is measured with question F1 “How influential are you in helping to shape key academic policies at your institution?1.

After the analysis of these first three hypotheses, and the non-verification of H3, we want to find the reasons for those results. For that purpose, in H4, we follow H3 steps for the group of those who have participated in external committees as peer reviewers. Finally, in H5, we refine the analysis by considering the academics who perceived themselves externally controlled and have also participated in committees as peer reviewers.

In addition to the mentioned statistical indicators and measures for addressing the five hypotheses, we have complementary incorporated others, when necessary, such as the standard deviation, the coefficient of variation or the percentage distribution, which allows for a deeper and a more specific analysis.

The employed method to evaluate the association between variables was the Chi square, whenever the variables allowed it. All the analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics v.25.

Results

H1: Most academics perceive external control over their teaching, research and external activities with emphasis on research.

Table A shows that just over half of academics perceive external control (51.6%) in their academic work, and they mainly perceive it over their research work, practically doubling the perception of external control over teaching (1.8 times more) and over social engagement activities (2.4 times more).

Table A: Perception of external control over academic activities

|

External Control (total) |

… over Teaching |

… over Research |

… External Activities |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: APIKS Argentina. F2_6.

So, it is confirmed that most academics perceive external control over their teaching, research and social engagement activities with emphasis on research control. But what influences this perception? What are the necessary conditions for such perception to come about?

H2: The academics´ perception of external control increases with a) the generation, b) the rank and c) the employment status.

Table B introduces the academic’s perception of external control both in general and in each dimension of their professional activity separately. The results show answers to F2_6 question to the APIKS questionnaire (See Annex). It is clear that there is a predominance of external control over research (45,3%) in comparison with control perceived over teaching (24,8%) or social engagement activities (18,6%).

External control over research shows the widest gaps between categories of each of the structuring features of the Argentinean academic profession: generation, employment status and rank. On the contrary, the perception of external control over social engagement activities is not only lower compared with the other activities, but also presents the narrowest gaps between categories.

Table B also shows that the perception of external control is statistically associated with the mentioned structuring features of the academic profession. And this association persists regardless of the area of external control (teaching, research or external activities) in such a way that the higher is the rank, the employment status and the older is the generation, the greater is the academic perception of external control. Therefore, H2a, H2b and H2c are confirmed.

Table B: Perception of external control by generation, employment status and rank

|

External |

… over |

… over |

… External |

||||||

|

% |

Dif |

% |

Dif |

% |

Dif |

% |

Dif |

||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Generation |

Consolidated |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intermediate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Novice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Employment Status |

Full-time |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Part-Time |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rank |

Senior |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Junior |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: APIKS Argentina. F2_6 by rank, employment status and generation.

*p<0.05 **p<0.,01 ***p<0.001

H3: Argentinean academics perceive that their influence in university decision making is greater: a) the closer is the organisational level; b) the older is the generation, the higher is the rank, and the employment status. c) They perceive their influence is lesser the higher is the perception of external control.

The comparison of answer averages of the perception of influence on different organisational levels (Table C1) shows a greater perception of influence on the chair or department where academics regularly perform their professional work, rather than on the academic unit where the authority is less close and where their own influence competes with other disciplinary groups.

The perception of influence is even lesser at the institutional level, where academics would probably have possibilities of influence only if they are part of collegiate bodies, or whether they are elected as deans or rectors. In other words, the perception of influence is lesser the further from their daily workplace is the level where decisions are taken.

Table C1: Academics’ influence by external control and structuring features

|

Chair/ |

Academic Unit |

Institution |

||

|

Total Mean (Stand. Dev.) |

2.30 (1.07) |

2.00 (1.05) |

1.83 (1.02) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: APIKS Argentina. (F1 & F2) by rank, employment status and generation.

*p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001

Table C1 also demonstrates an association between the perception of influence and each of the structuring features of the Argentinean academic profession. For all categories of these 3 studied variables, the previous finding is verified: the influence is associated with the organisational “closeness” – first, the chair or department; second, the academic unit; and, third, the institution.

It is also noted that the older the academic generation, the greater their perception of influence on institutional policies on all organisational levels. The same occurs with rank and employment status: those in the highest ranks and those spending more time at the workplaces are the ones who perceive themselves as more influential.

Finally, the comparison of means shows a higher perception of influence on all organisational levels in the academics who perceive themselves as externally controlled with respect to the total group, which is indicative of a statistical association between variables (Table C2). In all studied variables, it is also clear that the previous finding for the externally controlled group is verified for each of the specific externally controlled areas (teaching, research and external activities): the influence is associated with the organisational “closeness” – first, the chair or department; second, the academic unit; and, third, the institution. Also, there is a greater perception of influence among the externally controlled group, particularly on Social Engagement activities, followed by teaching and research.

Given these results, hypotheses H3a and H3b must be accepted, whereas H3c, on the contrary, must be rejected. Far from the perception of decreasing influence, the externally controlled academics perceive themselves to be more influential than the total group. In addition, this is more prevalent the closer is the organisational level. And this influence is greater the older is the academic generation, the higher is the rank and the higher is the employment status. Going even further, we have also found that the conclusion drawn in H3c is not dependent on the type of academic activity. Indeed, the analysis shows similar results when considering the external control over teaching, research and external activities separately (Table C2, b).

Table C2: Academics’ influence by external control

|

Chair/ |

Academic Unit |

Institution |

|

|

Total Mean (Stand. Dev.) |

2.30 (1.07) |

2.00 (1.05) |

1.83 (1.02) |

|

Externally Controlled |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: APIKS Argentina. F1 by external control (F2_6).

*p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001

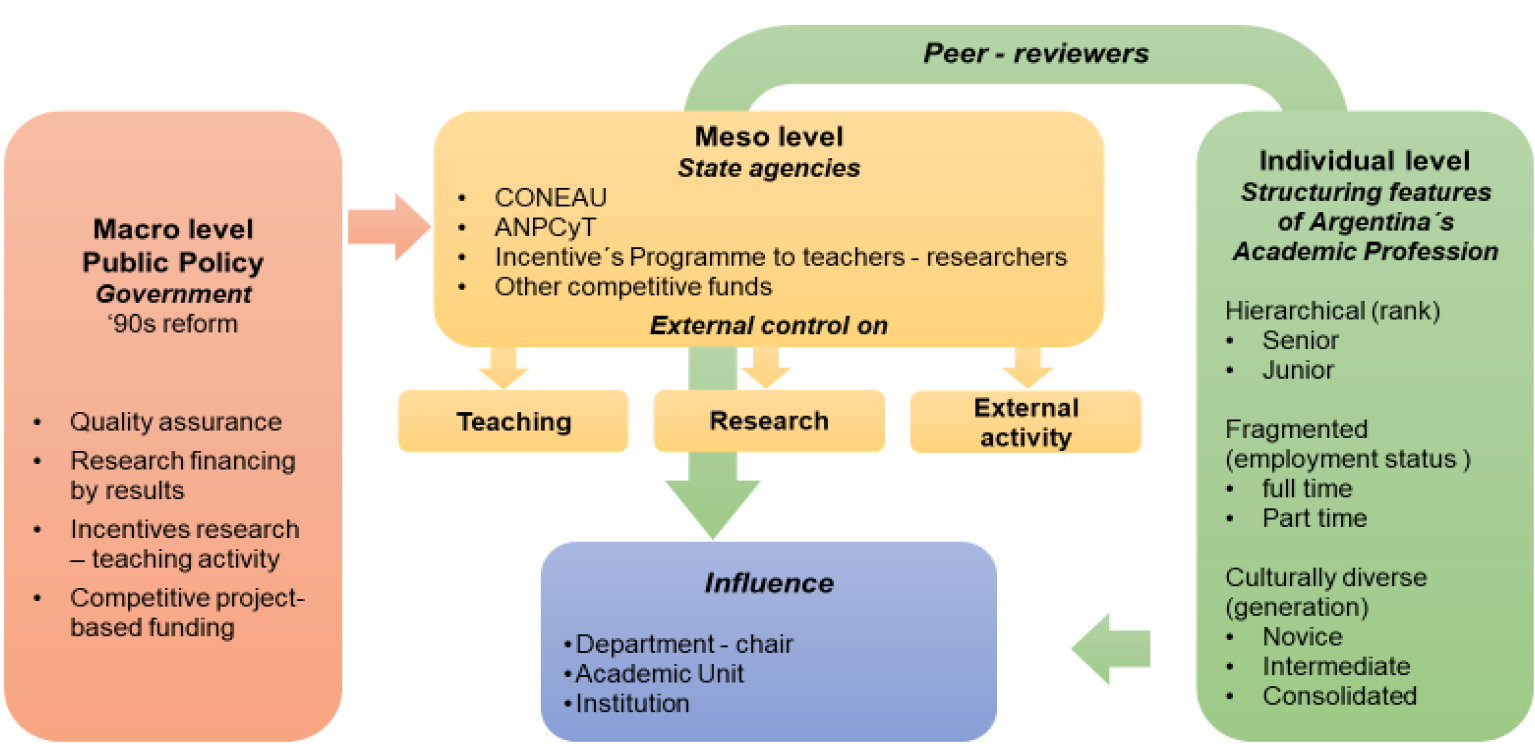

Additional research and new results

After the analysis of the first three hypotheses, and the non-verification of H3c, we wanted to find the reasons for these results. To that end, we reviewed the literature that delved into the study of state agencies for higher education policies and new relationships between state policies, agencies, and the academic profession.

Graphic 2: New analytical model for the study of academic institutional influence in the context of external control

Musselin (2013) has pointed out that, rather than weakening professional power, the recent reforms have reconfigured the academic profession by reinforcing the power of academics who participate as peer reviewers at state agencies. She argues that the studies concluding that reforms have weakened the academic profession have overlooked the reinforcement of the role of peer reviews conducted by state agencies, with effects on university governance and power distribution within the academic profession. She concludes that the changes are not a zero-sum game in which some win power (for example, managers) and others lose it (academics), but these powers combine. She also concludes that the internal power distribution among academics has changed as well. According to this, we decided to make our analytical model more complex by introducing “served as peer reviewer” as a new independent variable that might affect the academic influence at different levels of the organisation (Graphic 2).

H4: Participation in external committees as peer reviewers increases academic influence at the institution

Testing if Argentina reaches similar conclusions like Musselin’s for the European context, we found that academics who served as peer reviewers feel more influence at the three organisational levels than those who do not (Table D), and then H4 can be accepted. The institutional level is the one where we have found the highest gaps between the group that served and the groups that did not serve as peer reviewers.

Table D: Academics’ influence by serving as peer reviewer

|

Chair/Dept. |

Academic Unit |

Institution |

||

|

Total Mean |

|

|

|

|

|

Served as peer reviewer |

Yes |

|

|

|

|

No |

|

|

|

|

Source: APIKS Argentina. F1 * B6_2.

*p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001

H5: Externally controlled academics that participate in committees as peer reviewers perceive themselves as more influential at the institution

Finally, we wonder what happens with the group that perceive themselves as externally controlled and have also served in committees as peer reviewers. Table E shows that this group perceive themselves as more influential than the total mean at all levels of the organisation (both characteristics are statistically associated), consistently with the results and findings of previous hypotheses.

Again, the institutional level is where the widest gaps are observed. This is the organisational level where a higher effect of the combination of these two characteristics (to be externally controlled and have experience as peer reviewers) is recorded, as compared with other organizational levels. This is verified both in general and when they perceive themselves externally controlled over each academic dimension separately. So, H5 must be also accepted.

Table E: Academic influence by externally controlled academics who served as peer reviewers

|

Chair/Dept. |

Academic Unit |

Institution |

|

|

Total Mean |

2.30 |

2.00 |

1.83 |

|

Served as peer reviewer |

2.49*** |

2.12* |

1.99* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: APIKS Argentina. F1 * (B6_2 & F2_6) / In parentheses, % of increase compared with total mean.

*p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001

Discussion

In this study we have studied the effects of changes in state-level public policies on the Argentinean academic profession. We conjectured that the shifts resulting in more external control over academic activity have impacted on the perception of institutional influence of academics.

We theoretically considered the predominance of a managerial state and an institutional governance model at institutions that might impact on academic influence in decision making at different organizational levels of Argentinean universities, after nearly two decades of a profound reform in higher education. We assumed that the new configuration of the state (macro and meso levels) has increased external control on research, teaching and social engagement activities of academics.

Our first three hypotheses addressed several aspects of the institutional influence of academics, with focus on the total group and the specific group of academics that perceive themselves as externally controlled. In both cases, we do so regarding what we have called “structuring features of the academic profession in Argentina” (generationally diverse, fragmented in full-timers and part-timers; and hierarchical in ranks), since these traits are country-specific when compared with the academic professions of other countries.

Our results showed that more than a half of Argentinean academics perceive themselves as externally controlled, mainly in research activity (H1). We also found that this perception of external control varies according to the specific features of our academic profession. We assumed in H2 that academics tended to perceive themselves as more externally controlled the higher is the rank and the employment status, and the older is the generation, a hypothesis that could be accepted. One possible interpretation of this finding is that the regulations stated at the public policy level, and applied by state agencies at the meso level, have been assumed by most academics as part of their work and culture. Besides, whereas young academics have entered the career with the new rules fully functioning, and part-timers might not be so much involved with the external requirements, the consolidated and senior academics have been witnesses of the changes, and full-timers have been asked to be strongly accountable for their research and social engagement activity. Therefore, consolidated, seniors and full-timers perceive the influence of state agencies over their work more roundly.

We have obtained significant and unexpected findings regarding academic influence in helping to shape key academic policies at their institution. We assumed in H3a that the influence on different organisational levels is part of the path where first steps occur in closer settings (the chair, the department), and later extend to the academic unit and to the institution. We also supported the idea that academics perceive themselves as more influential when the academic career is more advanced (H3b). Indeed, our results show that academics perceive themselves as more influential in decisions at the closest organisational level. Also, our findings prove that the influence is greater the older is their academic generation, the higher is the rank, and the higher is the employment status. This is consistent with the academic career development; to the extent that academics advance in their careers, they perceive themselves as having greater influence on institutional policies at all organisational levels. On the basis of the theoretical assumption of the effects of NPM at the public policy level, with the creation of state agencies (Hood & Scott, 1996), and the increase in managerial institutional responses (Deem, 1998); as well as gradual transformations in the internal functioning of universities towards the managerialisation of academic tasks (Marquina, 2020; Obeide, 2020), we also assumed in H3c that the perception of influence is lesser the higher is the perception of external control. Surprisingly, rather than seeing less influence when there is a higher perception of external control, our study provides indications of the contrary. Those who perceive being externally controlled are the ones that perceive themselves as more influential, and this is more evident in older generations and higher ranks. Additionally, we have also found that the conclusion drawn in H3c is not dependent on the type of academic activity.

We wanted to find the reasons for these results. We reviewed the literature that delved into the study of state agencies for higher education, and the role of peer reviewers in the processes developed there, following Musselin’s (2013) conclusions stating that rather than weakening professional power, the recent reforms have reconfigured the academic profession by reinforcing the power of the academics who participate as peer reviewers at state agencies. Accordingly, we decided to introduce having “served as peer reviewer” as a new independent variable in our analytical model, assuming that this condition might provide more in-depth explanation as to why the academic influence on different levels of the organisation increases when academics perceive themselves as more externally controlled.

As expected, we could confirm the association between participation as peer reviewers and influence on different organisational levels, and we could also verify that in Argentina, like in Europe, the role of peer reviewers in the new configuration of the public policy level (macro) and the implementation level (meso) has created an elite that perceives itself as more influential than the rest of its colleagues. Also, our results showed that this group of peer reviewers within the institution perceives to be influent the most at the highest organisational level where big decisions are made. Not being sufficiently satisfied with these findings, we wanted to go further, by including the “external control” variable. Following Musselin’s conclusions, we could confirm that the perception of external control, far from reducing the influence of academics who served as peer reviewers, could increase it at all levels of the organisation.

We interpret these findings as the expression of how academic power articulates with the meso level where policies for higher education are implemented. As Musselin (2013) argues, external councils and agencies depoliticise as well as legitimise governmental decisions by giving peer reviewers the decisions on results, based on rules and criteria that have been produced by the agencies, to guarantee the quality of the peer-review process, although its content has been developed with the academics, often in negotiation with a larger community.

The rationale of external control might not be reducing the power of academics. On the contrary, it might be legitimating and reinforcing academic institutional influence, especially in the academics of the oldest generation, with higher ranks and more weekly time at the workplace. Since our results also show that the group of academics that perceive themselves as most influential is composed of those who have served as peer reviewers and also perceive themselves as externally controlled the most, we can also interpret such expression of “external control” over their academic activity not as a signal of weakness, but of more power given by the knowledge they have about the rules of academic control and the meaning they give to this condition as well. In sum, when academics manifest to be externally controlled, they might be expressing “I am the one who is exercising external control over my colleagues”.

Based on the findings, our central conclusion is that the idea of a shift towards the weakening of academic autonomy and power because of the new regulations decided at the public policy level and implemented at the state agencies level is not true for Argentina. As Musselin (2013) concludes, meso-level agencies in charge of the implementation of the instruments of public policies act as important vectors of influence and power for the group of academics of the oldest generation which, paradoxically, have spent most of the time of their academic career without the new rules. Apparently, the structuring features of the Argentinean academic profession exacerbate by increasing the diversity between generations and the gap between hierarchies. As pointed out by Whitley (2007), this is the academic elite that decides who will get resources and rewards, so they provide an equilibrium in the relationship between the academic profession and the state and have a strong influence on the regulation of the academic profession.

Based on these conclusions, it will be interesting to evaluate at the level of public policy and state agencies how well the peer review system has worked during these two decades as facilitators of the implementation of the policies designed. Likewise, future research may study in more detail to what extent the performance of these peer evaluators has meant an expansion of academic power in public policy or has collaborated in the strengthening of a certain conservatism of the profession with the consolidation of a small elite with growing power in the institution.

References

ANNEX

|

Hypotheses |

Dependent variables |

APIKS |

Measure |

Independent variables |

Association measure |

|||

|

H1 |

Most academics perceive external control over their teaching, research and external activities with emphasis on research control. |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

H2 |

The academics´ perception of external control increases with a) the generation, b) the rank and c) the employment status. |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

H3 |

Argentinean academics perceive that their influence in university decision-making is greater: a) the closer is the organisational level; b) the older is the generation, the higher is the rank, and the employment status. c) They perceive their influence is lesser the higher is the perception of external control. |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

H4 |

Participation in external committees as peer reviewers increases academic influence at the institution. |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

H5 |

Externally controlled academics that participate in committees as peer reviewers perceive themselves as more influential at the institution. |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||

1 See Annex for more methods details.