Acta humanitarica academiae Saulensis eISSN 2783-6789

2025, vol. 32, pp. 152–169 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/AHAS.2025.32.11

Terminology Commissions in Latvia (1919–1921) and Lithuania (1921–1926): Comparative Research

Regīna Kvašīte

University of Latvia, Latvia

regina.kvasyte@lu.lv

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7247-7022

https://ror.org/05g3mes96

Abstract. The first Terminology Commissions were established in Latvia in 1919, and in Lithuania in 1921. The article discusses the establishment of the Terminology Commissions of Latvia and Lithuania, the organisation of the work and its results based on the research carried out so far, publications in the press and the minutes of the Terminology Commissions meetings.

Many similarities were found between the Latvian Terminology Commission and the Lithuanian Terminology Commission, for example, subcommittees of various fields were created to consider terms and the accepted terms were later reviewed by the general commission. However, the main difference is that the Latvian Terminology Commission had more subcommittees and members in them, which allowed to cover a larger number of areas. In both Latvia and Lithuania, lists of terms under consideration were published in the press – mainly in journals Izglītības Ministrijas Mēnešraksts (Monthly of the Ministry of Education) (Latvia) and Švietimo darbas (Work of Education) (Lithuania). The public could also express their opinion.

The results of the work of both Terminology Commissions have a lasting value: the dictionaries of Latvian and Lithuanian terms: in Latvia Zinātniskas terminoloģijas vārdnīca (Dictionary of Scientific Terminology) in 1922, in Lithuania Įvardai, arba terminai, priimti Terminologijos komisijos (Terms, Approved by the Terminology Commission) in 1924. However, they differ both in scope and quality of preparation.

Specialists from various fields, as well as famous linguists – Latvian Jānis Endzelīns (1873–1961) and Lithuanian Jonas Jablonskis (1860–1930) participated in the work of the Lithuanian and Latvian Terminology Commissions. Although none of them left behind any theoretical works on terminology, their consulting, coining of new or correcting existing terms in their languages was a significant contribution to the development of scientific terminology in their countries.

The research shows that the establishment of the first Terminology Commissions and their role in each of the countries should be evaluated similarly, but it is regrettable that due to financial, organisational and personal problems, the activities of Latvian Terminology Commission and Lithuanian Terminology Commission did not last long.

Keywords: Latvian terminology, Lithuanian terminology, the first Terminology Commissions, Jānis Endzelīns, Jonas Jablonskis, dictionaries of terms, comparative research.

Terminologijos komisijos Latvijoje (1919–1921) ir Lietuvoje (1921–1926): gretinamasis tyrimas

Anotacija. Pirmosios Terminologijos komisijos įsteigtos Latvijoje 1919 metais, o Lietuvoje 1921 metais: straipsnyje aptariamas komisijų įkūrimas, darbo organizavimas ir rezultatai, remiantis iki šiol atliktais tyrimais, publikacijomis spaudoje ir komisijų posėdžių protokolais.

Nustatyta nemažai panašumų, pavyzdžiui, ir Latvijoje, ir Lietuvoje terminams svarstyti buvo sukurti įvairių sričių pakomitečiai, o jų priimtus terminus vėliau tvirtino bendroji komisija. Pagrindinis skirtumas, kad Latvijos Terminologijos komisijoje buvo daugiau pakomitečių ir narių juose, kas leido aprėpti daugiau sričių. Tiek Latvijoje, tiek Lietuvoje apsvarstytų terminų sąrašai buvo skelbiami spaudoje – Latvijoje daugiausia žurnale Izglītības Ministrijas Mēnešraksts (Švietimo ministerijos mėnraštis), o Lietuvoje – Švietimo darbas. Savo nuomonę galėjo pareikšti ir visuomenė.

Abiejų pirmųjų Terminologijos komisijų veiklos rezultatai apibendrinti terminų žodynuose: Latvijoje 1922 metais išleistame Zinātniskas terminoloģijas vārdnīca (Mokslinės terminijos žodynas), Lietuvoje – 1924 metų leidinyje Įvardai, arba terminai, priimti Terminologijos komisijos. Tačiau jie skiriasi tiek apimtimi, tiek parengimo kokybe.

Terminologijos komisijų darbe dalyvavo įvairių sričių specialistai, taip pat žymūs kalbininkai – latvis Jānis Endzelīns (1873–1961) ir lietuvis Jonas Jablonskis (1860–1930). Nors nė vienas iš jų nepaliko teorinių darbų terminologijos klausimais, jų konsultavimas, naujų terminų kūrimas ar esamų terminų taisymas buvo reikšmingas indėlis į savo kalbų terminijos raidą jų šalyse.

Tyrimas rodo, kad pirmųjų TK įkūrimas ir jų vaidmuo kiekvienoje iš šalių vertintini panašiai, tačiau jų veikla – Latvijoje dėl finansinių, Lietuvoje labiau dėl organizacinių ir asmeninių problemų – truko neilgai.

Pagrindinės sąvokos: latvių terminologija, lietuvių terminologija, pirmosios Terminologijos komisijos, Jānis Endzelīns, Jonas Jablonskis, terminų žodynai, gretinamasis tyrimas.

Gauta: 2025-03-17. Priimta: 2025-11-21

Received: 17/03/2025. Accepted: 21/11/2025

Copyright © 2025 Regīna Kvašīte. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The historical development of the Latvian and Lithuanian states was determined by different factors, but there were periods when similar processes took place in them. This was reflected in both political, economic and social life. Lithuania declared independence on February 16, 1918, Latvia – on November 18, 1918, and remained independent republics until 1940, when they were occupied by the Soviet Union. To meet the needs of the life of independent states, it was necessary to expand and improve the use of national languages, therefore, it was important to take care of the terminology of various fields. In the late 1920s and early 1930s – in Latvia in 1919, and in Lithuania in 1921 – Terminology Commissions were established, which began to develop the theory of terminology, but paid most attention to the management of terms in their languages. The work of both commissions featured the contributions of two of the most prominent linguists of the time – the Latvian Jānis Endzelīns and the Lithuanian Jonas Jablonskis.

The recent increase in interest in the activities of the Latvian and Lithuanian Terminology Commissions is related to their recently celebrated centenaries (Auksoriūtė 2021; Baltiņš 2020; Kvašīte 2020; 2024; Kvašytė 2021a; 2021b). It is recognized that in the management of terms, both Lithuanian and Latvian terminologists could have benefited from the data of the second Baltic language, as well as the experience of the neighboring country in how to manage terms. Hints about this can be found in the minutes of the Lithuanian Commission and other contemporary sources. Cooperation between Latvian and Lithuanian terminologists, as well as comparative research on terms in various fields (for more information, see Kvašytė 2022) are also significant in the current situation.

The aim of this study is to identify the similarities and differences in the establishment, organization of work, and dissemination of results of the first Terminology Commissions in Latvia and Lithuania. To achieve this aim, meeting minutes of the commissions as well as publications in academic journals and periodicals revealing the commissions’ activities were used. The novelty of the study lies in the comparative description of the establishment, activities, and disbandment of these commissions. Methodologically, the meeting minutes of the commissions in both countries and other sources were analyzed. The structure and activities of each country’s commissions are described, as well as the lasting results of their work – terminology dictionaries. Attention was drawn to the activities of the linguists of that time who actively participated in the activities of the commissions and the creation of terms – the Latvian Jānis Endzelīns and the Lithuanian Jonas Jablonskis. The minutes were searched for direct data on the influence of the second Baltic language on the creation of terms, and in other sources for indirect references to this.

1. Establishment and organization of the Commission’s work

1. 1. The Terminology Commission at the Ministry of Education of Latvia

In Latvia, the Terminology Commission under the Ministry of Education (Latvian: Terminoloģijas komisija pie Izglītības ministrijas) was established on 9 September 1919. The Minister of Education, Kārlis Kasparsons (1865–1962)1 and the Director of the 1st Department of the Ministry, Longīns Ausējs (1885–1942), signed Resolution No. 542 “Temporary Commission of the Ministry of Education”, which was published in the newspaper Valdības Vēstnesis (Government News). The resolution defined the composition of the commission: it was planned to appoint three representatives each from the Ministry of Education, the Latvian Teachers’ Union, the Faculty of History and Philology of the Latvian University of Applied Sciences, the Latvian Writers’ and Journalists’ Society, and the Latvian Engineers’ Union. It is stated that the members of the commission receive remuneration for participating in meetings and for the individual tasks entrusted to them, and in order for the considered terms to be finally adopted, they must be submitted to the Latvian Teachers’ Congress (Izglītības ministrijas terminoloģijas pagaidu komisija, 1919, p. 1).

From the protocols of the Latvian commission, which are stored in the Latvian State Historical Archive (Latvian: Latvijas Valsts vēstures arhīvs) fund No. 6637 are divided into separate files of the presidium, linguistics commission and sub-commissions, and various publications in the press show that the representatives of the organizations mentioned in the resolution were selected quickly: the delegates of the Writers’ and Journalists’ Union were the writer and public figure Linards Laicens (1883–1938), the man of letters, translator and teacher Kārlis Krūza (1884–1960) and the literary critic and journalist Jānis Akmens (1887–1958), the teachers’ union – mathematician, historian, researcher of the history of bibliography Jānis Straubergs (1886–1952), Vilis Plūdonis (real name Vilis Lejnieks; 1874–1940) and the literary researcher, lawyer and politician Kārlis Tīfentāls (after 1940 Kārlis Dziļleja; 1891–1963), both of them are also known as poets.

In the year of the commission’s establishment, the following sections operated: 1) natural sciences, 2) physics and mathematics, 3) medicine, 4) technology, 5) linguistics and philosophy, 6) legal economics and 7) arts section (later it was merged with linguistics and philosophy). In 1920, 4 more sections were established: 1) military, 2) painting and construction, 3) music and 4) veterinary. Each of the commission’s sections employed from 3 to 12 specialists in the relevant field. On September 27, 1919, the first commission meeting took place, at which the participating specialists were divided into sections, and recommendations were also made on the persons who should be invited to join (this was done at the next meeting). However, it was emphasized that the meetings were public – all persons interested in the creation of Latvian terms could participate in them.

On October 6, the meeting considered the draft activity plan of the commission (authored by the representative of the Latvian Teachers’ Union Straubergs), the essential provisions of which – the composition of the commission, membership in it, remuneration for work (the amount is determined by the ministry) – had already been fixed in the resolution on its establishment. The plan discussed the structure of the commission: the governing body is the plenary sessions, which adopt resolutions on the activities of the commissions and sub-commissions (sections), issue orders on terminology and spelling issues, elect the presidium of the commission, and also form sub-commissions. The executive body is the presidium, which consists of a chairman, two deputy chairmen and two secretaries. The tasks of the sections designated for managing terms in various areas are to collect material, contact different institutions in whose activities these terms might be needed, and prepare and submit projects to the commission. It is important to mention that a separate linguistics commission was also actively involved in the Latvian commission, whose members included linguist and language historian Ernests Blese (1892–1964), philosopher, psychologist, and pedagogue Pauls Dāle (1889–1968), as well as Krūza, Plūdonis, and Laicens.

The task of this commission was to assess the linguistic correctness of all terms considered by the sub-commissions before submitting them to the plenary session of the commission. In order to do this successfully, the members themselves had to be well versed in the terms used at that time, be able to choose the most appropriate term from the existing set of synonyms, and find or create new terms. Words from Latvian dialects were also very useful for creating new terms, a large collection of which was accumulated by Endzelīns (see more about him below). Words from other languages, especially Russian and German, were also used as examples for creating new terms, but the linguistic structure of the new words had to correspond to the system of the Latvian language (Skujiņa, 1972, pp. 17–18). At least one specialist in the relevant field who was well versed in the concepts, i.e. the content of the terms, had to participate in the consideration of terms.

Many prominent specialists in their fields were involved in the activities of the Latvian Commission Presidium and various sub-commissions: veterinarian, microbiologist Augusts Kirhenšteins (1872–1963), physicist Fricis Gulbis (1891–1956), architect Augusts Malvess (1878–1951), journalist, bibliographer and cultural historian Matīss Ārons (1858–1939), teacher, book publisher, lexicographer Jēkabs Dravnieks (1858–1927), writers Jānis Jaunsudrabiņš (1877–1962) and Jānis Jaunzemis (pseudonym Apšīšu Jēkabs; 1858–1929), etc. It should be noted that at that time many specialists were educated experts in several fields. The first chairman of the commission was Ādolfs Vickopfs (1878–1967), an engineer and technologist who had worked as a teacher at the Riga State Technical School. J. Straubergs (1886–1952) and the educator, geographer, translator, and poet Fricis Adamovičs (1863–1933) were elected as deputies (for more information, see Kazakeviča 2016; Baltiņš & Kazakeviča, 2024a).

At the meeting of January 22, 1920, when a certain sample of terms adopted by the commission had already begun to take shape, Deputy Chairman Adamovičs was instructed to contact the editorial offices of newspapers and magazines, especially the future ministry publication Izglītības Ministrijas Mēnešraksts (Monthly of the Ministry of Education). The first issue of the monthly was published on February 28, and 247 terms were already published in it. Lists of terms were also published in the official daily newspaper of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Latvia Valdības Vēstnesis (1919–1940) (Government News). Some lists of terms were reprinted by other publications in Latvian periodical – Ekonomists (The Economist), Latvju Mūzika (Latvian Music), Latvijas Kareivis (Latvian Soldier), Latvijas Sargs (Latvian Guard), Satiksmes un Darba Ministrijas Vēstnesis (Bulletin of the Ministry of Transport and Labor), etc., but they selected them according to the specific interests of their readers (Baltiņš & Kazakeviča, 2024a, pp. 179–181).

The need to publish terms in the press raised the question of the order in which they should be presented. Based on the assumption that Latvian equivalents would most often be sought for a certain Russian or German term, it was decided to present them in the following order of languages: Latin, Russian, German, English, French and Latvian (the choice of foreign language equivalents varied slightly by area). This resolution also regulated the principle of compiling the index.

1. 2. The Terminology Commission at the Ministry of Education of Lithuania

In Lithuania, the Terminology Commission (Lithuanian: Terminologijos komisija prie Švietimo ministerijos) was established following the example of Latvia. The prominent Lithuanian linguist Jablonskis, who also became one of the members of the commission, made a significant contribution to this. On March 14, 1921, in Kaunas, the temporary capital of Lithuania at that time (1920–1939), the head of government (Prime Minister) Kazys Grinius (1866–1950) and the Minister of Education Kazys Bizauskas (1893–1941) signed the Order of the Ministry of Education No. 551 on the establishment of the commission (Terminologijos komisijos sudarymo įsakymas, 1921, p. 4). The Order regulates that the commission consists of 10 people invited by the Ministry of Education. The following subcommittees are formed separately from the terminology commission, the members of which are employees of interested state institutions (they may also co-opt other necessary specialists): 1) philosophy and theology, 2) physics-mathematics and natural sciences, 3) technology, 4) medicine, 5) law, 6) trade and industry, 7) agriculture, 8) war, 9) administration and 10) art. The subcommittees prepare lists of terms, to which texts in Russian and preferably one of the Western European languages must be added. The meetings are attended by members of the interested subcommittees, who have the right to make decisions, i.e. the role of specialists in specific fields is highlighted. The adopted terms are made known to the public, and after receiving feedback, the commission reviews the terms once again and then announces them as mandatory for use. The order also mentions that the ministry pays 50 auksinas (the Lithuanian currency at the time; from auksas ‘gold’) for participation in the meeting.

The minutes of the Lithuanian Terminology Commission No. 1–80 (1921–1923) are kept at the Institute of the Lithuanian Language (Lithuanian: Lietuvių kalbos institutas), and No. 81–180 (1924–1926) in the Central State Archives of Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuvos centrinis valstybės archyvas) (Auksoriūtė, 2011, p. 81). The first meeting of the commission took place on April 21, 1921. Ten participants were invited, of whom seven attended.Those present discussed the tasks of the commission and the organization of its work. The first task of the commission was to unify the official language of state institutions, and it was also agreed that it was necessary to review and correct the terms of various scientific fields. The activities were to be organized in such a way that the responsible persons of the interested ministries officially submitted drafts of terms to the commission in writing (10 copies each), which were sent to the commission members for review (detailed explanations of concepts were required). However, the terminology commission paid attention not only to the management of terms, but also to other language issues: it considered the forms of geographical names, ethnonyms, etc. It was decided to publish in the press that such a commission had been formed and had begun its work. At the second meeting, the Lithuanian commission elected a chairman. He was the lawyer, state, public and cultural figure Antanas Smetona (1874–1944). It should be noted that Smetona was the first and fourth president of Lithuania (in 1919–1920 and 1926–1940, respectively), in whose life Latvia also played an important role – he studied privately in Liepāja, and then at the Mintauja (now Jelgava) gymnasium. The secretary of the commission was linguist, teacher, and press worker Antanas Vireliūnas (1887–1925). In 1919–1921, he worked at the Ministry of Education. However, the minutes of the meetings show that during the five years of the first commission’s operation, other individuals also held the position of secretary.

All members who began working in the Lithuanian Commission are listed in the first minutes: linguist Kazimieras Būga (1879–1924), poet and literary critic, theologian and mathematician, public figure and Esperanto speaker Aleksandras Dambrauskas (known as Adomas Jakštas (1860–1938)), philosopher, educator Pranas Dovydaitis (1886–1942), linguist Jonas Jablonskis (1860–1930), writer, educator, cultural figure Pranas Mašiotas (1863–1940), the aforementioned Smetona and Vireliūnas, and lawyer and political figure Vladas Požėla (1879–1960), who did not attend the first meeting, writer, press worker, public figure, educator and priest Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas (1896–1933), and painter, graphic artist, photographer Adomas Varnas (1879–1979), and subcommittees usually consist of three people. From the minutes, one can find out which areas of terminology are planned to be discussed, because preparations were underway to form the corresponding subcommittees. For example, Smetona, a lawyer and chairman of the terminology commission, was to form a legal subcommittee, and Tumas-Vaižgantas – a literary terms subcommittee. It was mentioned that it was recommended to invite writers, poet, playwright, critic, publicist, translator and cultural and Soviet government figure Liudas Gira (1884–1946) and prose writer, playwright and political figure Vincas Krėvė-Mickevičius (1882–1954) to it (for more information on the management of literary terms, see Mitkevičienė, 2013). The prominent naturalist Tadas Ivanauskas (1882–1970) was tasked with discussing natural terms and gathering the necessary specialists. A total of 26 meetings were held during the first year of the commission’s activities. They discussed not only terms, but also ethnonyms, geographical names, place names, etc.

It is important to mention that many members of the Lithuanian commission were connected with Latvia at that time – they studied or worked in Rīga (Mašiotas), Liepāja, Jelgava (Jablonskis, Smetona). This could have influenced the work of the commission, despite the fact that the Latvian Terminology Commission was no longer active when the commission in Lithuania was established and operating. It is likely that they knew or could have heard about the terminology management in Latvia.

The Lithuanian Commission organized its work similarly to the Terminology Commission in Latvia – sub-committees in various fields were created to consider terms, the terms adopted by which were later reviewed and approved by the general commission (presidium). Another similarity between the Latvian and Lithuanian practice of adopting terms is that the public could also express their opinion on the adopted terms, therefore, the relevant lists were published in the press. The minutes of the meeting of January 4, 1923 described the procedure for how persons who submit terms to the commission for consideration must prepare them – wherever possible, they must add equivalents in foreign languages. This minutes (No. 51) recorded that the commission must acquire dictionaries of terms published in other languages, including Latvian. It can be assumed that the term dictionary published by the Latvian Terminology Commission in 1922 is primarily concerned, although dictionaries of terms in Latvian had been published before that, as already mentioned earlier. The deadlines adopted by the commission were published in the journal Švietimo darbas (Work of Education), which was published in Kaunas (1919–1930) and in the official daily newspaper Lietuva (Lithuania) (Kaunas, 1919–1928). The commission’s minutes contain records of observations received after the publications, for example, on May 17, 1923, regarding telephone deadlines.

However, the work of the Lithuanian Commission was not smooth – the minutes repeatedly recorded that it was necessary to reorganize it. Two main reasons were mentioned: 1) more and more members of the Commission were not attending the meetings and 2) the work of the Commission itself and the sub-commissions was ineffective, because it was not properly prepared. However, on February 2, 1922 (No. 31), it was decided to increase the remuneration for participation in the meetings (this is one of the important complaints about the smooth functioning of the Commission) from 50 auksinas to 150 auksinas and to oblige the Presidium to organize the lists of terms already submitted by the sub-commissions. The creation of terms was difficult, because there was not a sufficient number of qualified linguists, and the unqualified members of the Commission had no understanding of the principles of terminology management and the norms of common language.

2. Terminological activities of prominent linguists

The research focused mainly on the most prominent linguists of the time, Jānis Endzelīns and Jonas Jablonskis, although other linguists from both countries also participated more or less actively in the activities of the commissions (or sub-commissions).

2. 1. Jānis Endzelīns (1873–1961)

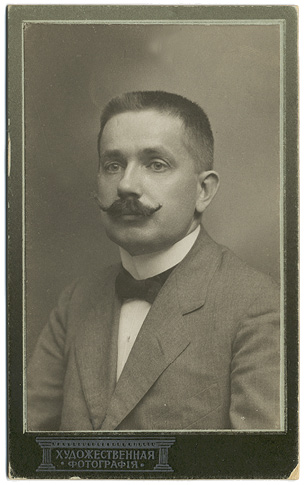

Endzelīns joined the work of the Terminology Commission after returning from Kharkiv, where he taught at the university in 1908–1920 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Jānis Endzelīns in Kharkiv (~1920) (Latvian National Museum of Literature and Music, No. RMTM 246629).

He was invited to return to Latvia by the government to work at the Latvian Higher School established in 1919 (renamed the University of Latvia on August 22, 1922). At the meeting of June 21, 1920, the chairman of the commission, Vickopfs, made a proposal to invite Endzelīns, and he was immediately elected a member of the Terminology Commission and its Linguistics Commission, and at the meeting of June 28, he was already welcomed for the first time at the meeting. At that time, the linguist, folklorist, ethnographer, mythologist Pēteris Šmits (1869–1938) was also elected to the commission. When on August 30, 1920 , new elections for the presidium of the Latvian Commission were held, Endzelīns was elected chairman, and he asked that his deputies Blese and Krūza take care of technical matters. At the meeting on September 13, Endzelīns refused to head the Linguistics Commission, and Šmits was elected in his place. Until the end of the Commission’s activities, in addition to the chairman and Endzelīns, its secretary Blese, as well as Krūza, Kauliņš, Dravnieks, Jaunzems and Ārons, actively participated in the activities of the Linguistics Commission (Baltiņš & Kazakeviča, 2024a, p. 156).

Based on the Latvian linguist Daina Nītiņa and the memoirs of his former students who shared about the professor, Solvita Labanauskienė (2012, p. 175) describes Endzelīns’ activities, stating that the scientist emphasized the significance of neighboring languages and used Lithuanian as an example for the Latvian language, and also often used Lithuanian language facts in his research. In addition, which is very important in terminology, Endzelīns cared about the purity of his native language, he openly, strictly and critically spoke about language errors and irregularities, he was concerned with linguistic correctness: respect for the meaning of words, grammatical correctness and sonority. He demanded this from every speaker and writer (Ibid., p. 175) (for more on Endzelīns’ works, see Nītiņa, 1972; Skujiņa 1972; Labanauskienė 2012; Baltiņš, 2024).

2. 2. Jonas Jablonskis(1860–1930)

Jablonsk is, as already mentioned, made a significant contribution to the establishment of the Terminology Commission in Lithuania (see Figure 2).

He repeatedly popularized the work of his Latvian colleagues in the press and urged Lithuanians to follow their example. In the magazine Švietimo Darbas in December 1920, even before the establishment of the commission, introducing the latest issue of the Latvian periodical Izglītības Ministrijas Mēnešraksts, he wrote about the commission established in Latvia under the Ministry of Education, explaining in detail the purpose and who formed the commission, how it works, and how and where it publishes the terms it considers. Jablonskis drew attention to the fact that the commission addresses people who are knowledgeable in a specific field of activity through the press and asks them to express their opinion on the terms adopted. Having received observations, the commission once again considers the terms that have caused doubts and finally publishes them for public use (Jablonskis, 1933, p. 225). By the way, Jablonskis encouraged people to visit and familiarize themselves with the activities of the Latvian Terminology Commission so that its experience could be adopted in Lithuania. His suggestion to use the results of Latvian work is also noteworthy.

Figure 2.

Jonas Jablonskis in our home (~1920–1925) (Maironis Lithuanian Literature Museum, No. MLLM F1 17394).

Although Jablonskis did not leave behind any theoretical works on terminology, his practical work in consulting, creating new or refining existing terms in his languages made a significant contribution to the development of scientific terminology in his countries (for more on Jablonskis’ works, see Piročkinas, 1978; Keinys, 2012). In Jablonskis’ opinion, the main principle of terminology work is that terms in special scientific fields should be created by specialists in that field, and linguists can only evaluate them from the point of view of language correctness (cf. the Latvian commission’s requirement that a representative of a specific field participate in the deliberations of the linguists’ commission). While living in Voronezh, where he taught Lithuanian and Latin in 1915–1918, Jablonskis implemented this principle in practice – he consulted those specialists who asked for help in preparing textbooks, etc. (Piročkinas, 1978, pp. 136–139).

Jablonskis “has never written or spoken publicly about the principles of his terminology work. However, it cannot be said that he did not have them. His views on the standardization of terms were consistent and quite clear. Having graduated from philology at Moscow University, J. Jablonskis correctly understood the place of terminology in the dictionary system. Terminology (especially its core, i.e. the names of the main concepts) cannot be too far removed from the literary language. That is why J. Jablonskis said that terms should be created in the same way as ordinary words in our language. The second thing that can be understood from J. Jablonskis’ term management activities is that there is no need to look for Lithuanian substitutes for international words that have become established in the language system. The third thing is that J. Jablonskis was well versed in the specifics of word formation and skillfully applied it to terminology matters. Looking at the neologisms created by J. Jablonskis (e.g. deguonis ‘oxygen’, vandenilis ‘hydrogen’, dėmuo ‘element’), it can be seen that they were highly specialized. Many of the new words proposed by A. Vireliūnas could not even remotely compare with them. For example, the word bakas ‘tank’ could not compete with A. Vireliūnas’ new word pilas, the word elektra ‘electricity’ – with the new word gintra, etc. The basis for the formation of these words – the main words from which the new words are made – have already been chosen inaccurately. Therefore, such new words, it is clear, could not take root. The new words of J. Jablonskis’ terminology were incomparably more specialized” (Gaivenis, 2014, pp. 270–271).

However, various disagreements arose in the commission, including among the linguists who arranged the terms. The minutes of January 11, 1923 (No. 52) record that Jablonskis refused to participate in the meetings, probably because he did not agree with the efforts of some members, especially Vireliūnas and Varnas, to Lithuanianize even long-established international words. Manifestations of purism especially intensified after Būga’s death on December 2, 1924.

Both Endzelīns (1935) and Jablonskis (1933) have expressed their opposition to such efforts to Latvianize/Lithuanize established international terms in their publications. For example, in Latvia, the name of the commission itself was discussed more than once – there was a desire to Latinize the international word terminoloģija ‘terminology’ used in it. However, no agreement was reached and the name of the commission remained unchanged. It should be noted that in Lithuania, instead of the international word termins ‘term’, a word įvardas of its own origin was used (see below). This was also commented on by another Lithuanian linguist, Juozas Balčikonis (1885–1969). In response to the reproaches directed at him for not participating in the commission meetings, he emphasized that he did not see the point in creating terms for such words as geografija ‘geography’, istorija ‘history’, geometrija ‘geometry’, trigonometrija ‘trigonometry’, geologija ‘geology’, etc. (Balčikonis, 1978, p. 46).

3. The dictionaries of Terminology Commisions

3. 1. Latvian dictionary of terminology

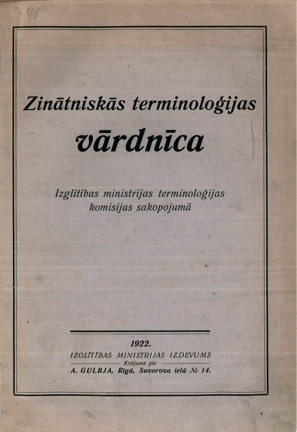

Even before the establishment of the Terminology Commission, specialized collections of Latvian and international words were published in Latvia, which can be considered dictionaries of terms, for example, dictionaries of navigation (1902; 1908), military (1914), construction (1922) (Banga et al., 1995). In 1922, after the Terminology Commission had ceased its activities, a dictionary of terms adopted by it Zinātniskās terminoloģijas vārdnīca (Dictionary of Scientific Terminology) was published (see Figure 3).

The dictionary contains terms from 20 fields (19 are named in the table of contents – veterinary medicine is not included), divided into thematic (sometimes combined) sections of varying scope: 1) linguistics, 2) philosophy, 3) law, 4) national economy and finance, 5) music, 6) painting, sculpture and construction, 7) natural sciences, 8) forestry, 9) chemistry and chemical technology, 10) mathematics, 11) geometry and drawing, 12) physics, 13) mechanics and resistance of materials, 14) machine and metalworking, 15) construction, 16) electricity and electrical engineering, 17) military, 18) maritime, 19) book industry and 20) veterinary medicine. In total, the dictionary contains 8,398 heading terms (according to other estimates, 8,462). The preface to the dictionary states that sources in Russian, German, English, and French were used, but the order in which they are presented in the dictionary – starting with terms in Russian – is explained by the fact that this language was best known to the commission members (the exception is bibliography, where German comes first) (Baltiņš & Kazakeviča, 2024b, pp. 185–187).

Figure 3.

Latvian dictionary of scientific terms (1922).

However, the dictionary provided artificially created incomprehensible terms alongside international words, for example, inerce ‘inertia’ – kutrība, klients ‘client’ – / pienāksnieks, koeficients ‘coefficient’ – reizulis, koridors ‘corridor’ – starpeja, signalizācija ‘alarm system’ – ziņdošana, temperatūra ‘temperature’ – siltkāpe, tēze ‘thesis’ – dēts, etc. (Grabis, 2006, p. 224).

As can be seen, the commission tried to eliminate most of the international words (which Endzelīns also called modern foreign words), replacing them with new words (Labanauskienė, 2012, pp. 177–178).

After the publication of the Terminology Dictionary, it was sharply criticized in the media. Endzelīns publicly published three letters addressed to one of the critics, Doctor of Medical Sciences Hermans Buduls, who called the dictionary “extremely superficial” in terms of terminology (for more details, see Endzelīns III2, pp. 127–133). The Latvian linguist wrote a strict response, in which he opposed the unfounded and absurd criticism. In the response letters, he indicated not only the motives for choosing the criticized terms, but also defined the principles of creating terms. Endzelīns considers three-word terms no longer to be terms, but definitions. In addition, in his opinion, it is important that all words used in the vernacular are first collected, and only then can word formation be resorted to (Skujiņa, 1972, p. 22).

In publications on the development of terminology in Latvia, this dictionary of terms always attracts attention. The dictionary is recognized as a significant source of the history of Latvian terminology, from which one can learn and adopt what was well established by the first professional collective of term creators, but not repeat the mistakes of old terminologists (Blinkena, 2017, p. 285). Modern authors highlight successfully proposed innovations, criticize tendencies to standardize long-used international terms (Grabis, 2006; Skujiņa, 2002). However, such assessments appeared after a certain time, when it was possible to more objectively assess the establishment of terms. The attitude of contemporaries to the results of the work of the Terminology Commission was reflected in the press. The reviews of that time contained both critical remarks and positive assessments, as well as observations about the process of term creation in general (Baltiņš, 2011).

3. 2. Lithuanian dictionary of terminology

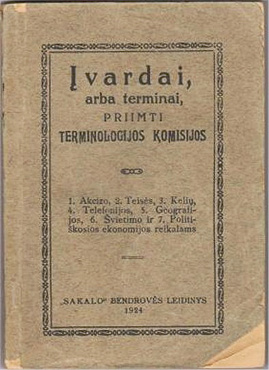

Before the establishment of the Terminology Commission, dictionaries of varying scope and quality had already been published in Lithuanian, both in Lithuania and abroad (in the USA, Russia), of terms in botany (1900; 1902; 1906), music (1916), arithmetic and algebra (1919), military (1919), geometry and trigonometry (1920), technology (1920), and zoology (1920) (Gaivenytė-Butler, Keinys & Noreikaitė, 2008). And in 1924, the secretary of the commission, Vireliūnas, prepared and, on his own initiative, published the dictionary Įvardai, arba terminai, priimti Terminologijos komisijos [Terms, approved by the Terminology Commission] (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Lithuanian dictionary of terms (1924).

This is a small-sized publication, which included terms from seven fields – excise, law, roads, telephony, geography, education, and political economy. The publication was criticized by many linguists and terminologists for its poor quality and layout errors. The review was published by Jablonskis, who expressed a number of criticisms (Jablonskis, 1933, pp. 322–324). He also criticized the word įvardas ‘term’ (from lithuanian verb įvardyti ‘to name’) used in the title, which he considered to be an inappropriate use (Keinys, 2012, p. 39). The contemporary lexicologist and terminologist Jonas Klimavičius (Klimavičius, 2005, p. 261) holds a different opinion – that the new word is good, probably created by Vireliūnas. It should be noted that this Lithuanian neologism as a synonym for a loanword has not disappeared from the Lithuanian language – several dictionaries in the title of which it is used appeared in Canada (Gaivenytė-Butler, Keinys & Noreikaitė, 2008, pp. 109; 135; 172), and one in Lithuania – Lietuvos pajūrio žvejų marinistikos įvardai [Marine Terms used by Lithuanian Coastal Fishermen] (Gudelis, 2006) (see also Kvašīte, 2022–2023; Kvašīte, 2024). However, it is recognized that a significant part of the terms adopted by the commission at that time are still used today (Auksoriūtė, 2011, p. 88).

By the way, the minutes show that the Terminology Commission considered Lithuanian literary, legal, etc. terms, as well as ethnonyms, geographical names, and place names, but literary terms, for example, were not included in the dictionary.

4. The Disbandment of the Commissions

4. 1. In Latvia

In Latvia, the Terminology Commission ceased its work in April 1921, when its funding was cut off due to the austerity regime (the interwar budget year began on April 1). At the last general meeting on May 9, 1921, it was decided to publish all the terms adopted by that time by field, submitting the compiled collection to a private publisher. At that time, the Commission’s leadership did not imagine that it could be liquidated, so it was recorded in the minutes that the Linguistics Commission would have a work break from June 1 to September 1. The hopes that by the end of the summer the financing issues would be resolved and the Commission’s activities would only be temporarily suspended did not come true. The Minister of Education Aleksandrs Dauge (1868–1937) and the Director of the School Department Ausējs (he also signed the establishment resolution) signed the School Department of the Ministry of Education Report No. 3109 on the termination of the Commission’s activities, was dated September 15, 1921 and published (Izglītības ministrijas Skolu departamenta lēmumi, 1921). The work of managing the terms was entrusted to the Committee of Sciences (Latvian: Zinātņu komiteja), which had already been conceived by the Minister of Education of the Provisional Government, Kasparsons. The establishment of such an institution, which would be responsible for the most important issues of scientific culture, was the first step towards a state academy of sciences (Stradiņš, 1998, p. 101). Endzelīns was approved as its president. Such a resolution made it possible to at least partially ensure the possibility of the Terminology Commission to resume its activities after a certain period of time.

However, in 1922, due to a lack of funding, the Science Committee was also disbanded. (Stradiņš, 1998, pp. 95–117). Endzelīns expressed his view on the end of the first Terminology Commission, indicating that the commission was not liquidated, but simply left without the already very small remuneration for participation in meetings. This meant that the activities of the commission were considered inappropriate or even unnecessary, and therefore the commission was liquidated without completing its work (Endzelīns, 1935). The idea of restoring the activities of the Terminology Commission was discussed several times. Around the time the dictionary of terms was being prepared, the Ministry of Culture was approached for support, but no official resolutions were found anywhere, and the preface to the dictionary states that the commission was forced to cease its activities due to budget shortages (Zinātniskās terminoloģijas vārdnīca, 1922).

4. 2. In Lithuania

In Lithuania, due to the ever-rising discussions, in which the public also gets involved, on the issues of creating new terms and the purism that flourished in this activity, etc., the Ministry of Education on March 21, 1925, issued Resolution No. 3509 on the establishment of a new commission. Jablonskis is appointed its chairman. The old commission convenes for a meeting on March 23, but after getting acquainted with the resolution, it expresses dissatisfaction with such behavior of the ministry and disperses. The first meeting of the new commission took place on March 26. Among the linguists, in addition to the chairman Jonas Jablonskis, Juozas Balčikonis, Antanas Salys and Pranas Skardžius participated in it. However, the composition of the commission changed quite often, which complicated the work, because the newly arrived members could not immediately fully engage in the activities. The greatest burden fell on chairman Jablonskis, who also had to be the organizer, because it was necessary not only to resolve issues of accepting deadlines, but also to look for new specialists, draw up estimates, submit reports, etc. Realizing that he did not have such organizational skills, Jablonskis resigned from the position of chairman, but agreed to stay to do practical work on creating deadlines (Auksoriūtė 2011, p. 89; see also Palionis, 1979).

The ministry’s reaction to Jablonskis’ statement was unexpected – it dissolved the commission and ordered that this work be organized at the University of Lithuania (under which Kaunas, now Vytautas Magnus University, operated from 1922 to 1930). The university senate, at its meeting on December 29, 1926, established the Terminology Commission, which included the doctor, educator, public and political figure Petras Avižonis (1875–1939), the philosopher and educator Stasys Šalkauskis (1886–1941), and the linguist Juozas Balčikonis. However, Avižonis protested against the liquidation of the previously operating commission and doubted whether the university faculties would be interested in dealing with terminology management. In addition, when Jablonskis left this work, there were no good terminology specialists left (Avižonis also refused to participate), so the Terminology Commission established by the university did not even begin to work (Piročkinas, 1978, pp. 175–182).

Conclusion

A comparative research shows that the establishment of the first terminology commissions in Latvia and Lithuania and their role in each country should be assessed similarly. In this way, there was a transition from individual and spontaneous term creation to collective and planned activity carried out by a specially created institution.

The Terminology Commission in Lithuania organized its work similarly to the Terminology Commission in Latvia – subcommittees in various fields were created to consider the terms, the adopted terms of which were later reviewed and approved by the general commission (presidium). However, the fundamental difference between the Latvian and Lithuanian commissions was that Latvia had more subcommittees and sections that formed them (32), while Lithuania had 10, as well as members in them, which allowed it to cover a larger number of areas. It is also similar that the public could also express their opinion on the adopted terms, since the lists of terms adopted by the commission were published in the press.

The result of the work of the first Latvian and Lithuanian terminology commissions, which has a lasting value, is the publication of dictionaries of terms adopted by them: in Latvia in 1922, in Lithuania in 1924. However, they differ in content, scope, and the attitude of contemporaries and modern terminologists to spoken publications. The order in which the terms are published also differs. The Latvian commission’s provisions were to publish terms in foreign languages first (usually Russian first, then German), so that the lists would be easier to use for those who do not know Latvian terms. The Lithuanian commission first presented Lithuanian terms.

The contribution of prominent personalities (primarily the linguists Endzelīns and Jablonskis) was also significant. Although none of them left behind theoretical works on terminology, their practical work in consulting, creating new or refining existing terms in their languages was a significant contribution to the development of scientific terminology in their countries.

The prevalence of purist tendencies was one of the similarities noted when comparing the activities of the first Latvian and Lithuanian terminology commissions, only in Lithuania they were more pronounced. This partly determined the fate of the commission. The work of the terminology commissions did not last long (in Latvia from 1919 to 1921, in Lithuania from 1921 to 1926), but they were interrupted for different reasons. In Latvia this was primarily due to a lack of funding, while in Lithuania it was due to disagreements between the commission members, as well as the unwillingness of the ministry to solve problems constructively.

The reviewed Latvian sources did not reveal any connections with the Lithuanian experience of terminology management. This is understandable, because when the Latvian Commission was working, such a commission did not yet exist in Lithuania, but terminological activities were taking place. And from the very beginning, the activities of the Lithuanian Commission included observations related to the work of Latvian terminologists and terminology management.

References

Auksoriūtė, A. (2011). Terminologijos komisijos (1921–1926) veiklos apžvalga. Terminologija, 18, 80–91.

Auksoriūtė, A. (2021). Terminologijos komisijos įkūrimo šimtmečiui. Gimtoji kalba, 3, 3–9.

Balčikonis, J. (1978). Dėl Terminologijos komisijos darbo. Rinktiniai raštai, I. Vilnius: Mokslas, 45–46.

Baltiņš, M. (2011). Laikabiedru vērtējumi par Zinātniskās terminoloģijas vārdnīcu (1922): konstruktīva kritika un mūžīgie jautājumi. Vārds un tā pētīšanas aspekti, 15 (2). Liepāja: LiePA, 17–26

Baltiņš, M. (2013). Terminrades process un principi. In A. Veisbergs (ed.), Latviešu valoda (pp. 415–433). Rīga: Latvijas Universitātes Akadēmiskais apgāds.

Baltiņš, M. (2020). Izglītības ministrijas Terminoloģijas komisijai – 100: ceļš līdz valstiski atzītai terminradei. Valodas prakse: vērojumi un ieteikumi, 15, 49–60.

Baltiņš, M. (2024). Jāņa Endzelīna terminoloģiskais mantojums un tā apzināšanas iespējas. Linguistica Lettica, 32, 54–87.

Baltiņš, M. (2024). Terminoloģijas komisijas izstrādāto terminu projektu publiskošana. In M. Baltiņš (ed.). Terminoloģija: teorija, vēsture, prakse (pp. 166–182). Rīga: Latvijas Universitātes Akadēmiskais apgāds.

Baltiņš, M. & Kazakeviča, A. (2024a). Terminoloģijas komisijas izveide un darbība. In M. Baltiņš (ed.). Terminoloģija: teorija, vēsture, prakse (pp. 110–165). Rīga: Latvijas Universitātes Akadēmiskais apgāds.

Baltiņš, M. & Kazakeviča, A. (2024b). „Zinātniskās terminoloģijas vārdnīca” un tās vērtējums. In M. Baltiņš (ed.). Terminoloģija: teorija, vēsture, prakse (pp. 183–199). Rīga: Latvijas Universitātes Akadēmiskais apgāds.

Banga, M., Cakule, G., Kļaviņa, S., Mūrniece, B. & Zariņa, S. (1995). Latvijā izdotās latviešu valodas vārdnīcas. Bibliogrāfisks rādītājs (1900–1994). Rīga: Latvijas Universitāte.

Blinkena, A. (2017). 1922. gada „Zinātniskās terminoloģijas vārdnīca” mūsdienu skatījumā. Caur vārdu birzi, II, Rīga: Latvijas Universitātes Latviešu valodas institūts, 282–285.

Gaivenis, K. (2014). J. Jablonskio veikla Terminologijos komisijoje. Rinktiniai raštai. Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 268–271.

Gaivenytė-Butler, J., Keinys, S. & Noreikaitė, A. (2008). Lietuvių kalbos terminų žodynai. Anotuota 1900–2005 m. bibliografijos rodyklė. Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas.

Grabis, R. (2006). Zinātniskās terminoloģijas izstrāde un terminoloģijas vārdnīcu veidošana. Darbu izlase. Rīga: Latvijas Universitātes Latviešu valodas institūts, ٢٥٢–٢٥٩.

Gudelis, V. (2006). Lietuvos pajūrio žvejų marinistikos įvardai. Vilnius: UAB „Utenos Indra”.

Įvardai, arba terminai, priimti Terminologijos komisijos (1924). Kaunas: “Sakalo” bendrovės leidinys.

Izglītības ministrijas Skolu departamenta lēmumi (1921, september 15). Valdības Vēstnesis, 209, 3.

Izglītības ministrijas terminoloģijas pagaidu komisija (1919, september 11). Valdības Vēstnesis, 34, 1.

Jablonskis, J. (1933). Terminų dalykas. In J. Balčikonis (ed.), Jablonskio raštai, II (pp. 210–212). Kaunas: Švietimo ministerija.

Kazakeviča, A. (2016). Izglītības ministrijas Terminoloģijas komisijas (1919–1921) darbības atspoguļojums Terminoloģijas komisijas sēžu protokolos. Terminrade Latvijā senāk un tagad. Latvijas Zinātņu akadēmijas Terminoloģijas komisijas 70 gadu jubilejas konferencei veltīts īsrakstu krājums. Rīga: Zinātne, 65–70.

Keinys, S. (2012). Lietuvių terminologijos kūrimo apžvalga (iki 1940 m.). Lietuvių terminologijos raida. Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 29–56.

Klimavičius, J. (2005). Lietuvių terminografija: praeities bruožai, dabarties sunkumai ir uždaviniai. Leksikologijos ir terminologijos darbai: norma ir istorija, Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas, 259–276.

Kvašīte, R. (2020). Pirmās Terminoloģijas komisijas Latvijā un Lietuvā. Zinātniskie raksti, 6 (XXVI), Latviešu terminoloģija simts gados. Rīga: Latvijas Nacionālā bibliotēka, 74–92.

Kvašīte R. (2022–2023). The Terms of the Latvian and Lithuanian Terminology: the Comparative Aspect. In L. Karosanidze (ed.), Terminology Issues, V (pp. 180–195). Tbilisi: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Arnold Chikobava Institute of Linguistics.

Kvašīte, R (2024). Pirmās Latvijas un Lietuvas Terminoloģjas komisijas un to darbības sastatījums. In M. Baltiņš (ed.), Terminoloģija: teorija, vēsture, prakse (pp. 200–211). Rīga: Latvijas Universitātes Akadēmiskais apgāds.

Kvašytė, R. (2021a, balandžio 14). Apie pirmąsias terminologijos komisijas Lietuvoje ir Latvijoje. Mokslo Lietuva, 7 (672), 11–12.

Kvašytė, R. (2021b, balandžio 28). Apie pirmąsias terminologijos komisijas Lietuvoje ir Latvijoje. Mokslo Lietuva, 8 (673), 6–7.

Kvašytė, R. (2022). Lietuvių ir latvių terminologija: istoriniai ryšiai ir gretinamieji tyrimai. Terminologija, 29, 169–181.

Labanauskienė, S. (2012). Janio Endzelyno terminologinės įžvalgos. Terminologija, 19, 173–183.

Mitkevičienė, A. (2013). Terminologijos komisijos (1921–1926) vaidmuo lietuvių literatūros mokslo terminijos istorijoje. Terminologija, 20, 172–179.

Nacionālā enciklopēdija. http://enciklopedija.lv/

Nītiņa, D. (1972). Vispārīgās valodniecības jautājumi akadēmiķa Jāņa Endzelīna darbos. Veltījums akadēmiķim Jānim Endzelīnam 1873–1973. Rīga: Zinātne, 11–24.

Palionis, J. (1979). Lietuvių literatūrinės kalbos istorija. Vilnius: Mokslas.

Piročkinas, A. (1978). J. Jablonskis – bendrinės kalbos puoselėtojas. Vilnius: Mokslas.

Skujiņa, V. (1972). J. Endzelīna devums latviešu valodas zinātniskās terminoloģijas attīstībā. Latviešu valodas kultūras jautājumi, 8, 17–33.

Skujiņa, V. (2002). Latviešu terminoloģijas izstrādes principi. Rīga: Latviešu valodas institūts.

Stradiņš, J. (1998). Mēģinājumi izveidot valstisku zinātņu akadēmiju Latvijā (1918. gads – 20. gs. 40. gadi). In J. Stradiņš. Latvijas Zinātņu akadēmija: izcelsme, vēsture, pārvērtības, I. Rīga: Zinātne, 95–117.

Švābe, A. (ed.) (1927–1940). Latviešu konversācijas vārdnīca. Rīga: A. Gulbis.

Terminologijos komisijos protokolai (1921–1923). Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos instituto Terminologijos centras (not published).

Terminologijos komisijos sudarymo įsakymas (1921). Vyriausybės žinios, 60, 4.

Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija. https://www.vle.lt

Zinātniskās terminoloģijas vārdnīca (1922). Izglītības ministrijas terminoloģijas komisijas sakopojumā. Rīga: Izglītības ministrija, A. Gulbis.

1 Additional data about individuals here and further is taken from various Latvian and Lithuanian dictionaries encyclopedias (Švābe, 1927–1940; Nacionālā enciklopēdija; Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija), however, specific sources are not cited for each surname.