Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2020, vol. 21, pp. 59–78 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2019.21.4

The Meaning of Eagles in the Baltic Region. A Case Study from the Castle of the Teutonic Order in Klaipėda, Lithuania (13th–14th Century)

Freydis Ehrlich

Institute of History and Archaeology,

University of Tartu, Jakobi 2, 51005, Tartu, Estonia

freydis.ehrlich@ut.ee

Giedrė Piličiauskienė

Department of Archaeology, Faculty of History,

Vilnius University, Universiteto 7, Vilnius, Lithuania

giedre.piliciauskiene@if.vu.lt

Miglė Urbonaitė-Ubė

Institute of Baltic Region History and Archaeology, Klaipėda University,

Herkaus Manto st. 84, LT-92294, Klaipėda, Lithuania

migle.urbonaite-ube@ku.lt

Eve Rannamäe

Institute of History and Archaeology,

University of Tartu, Jakobi 2, 51005, Tartu, Estonia

eve.rannamae@ut.ee

Abstract. In this paper, we examine archaeological bird remains from Klaipėda Castle (Ger. Memel), western Lithuania. The castle was built in 1252, and during the Middle Ages, it was the northernmost castle of the Teutonic Order in Prussia. The castle together with its adjacent town were subjected to wars and changing political situations over the centuries, but nevertheless represented a socially higher status. The studied bird remains were found during the excavations in 2016 and have been dated by context to the Middle Ages – from the end of the 13th to the beginning of the 14th century. Our aim is to introduce and discuss the bird remains with an emphasis on two species – the white-tailed sea-eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) and golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos). Most of all, we are interested in their role in expressing people’s social status, use in material culture, and significance as a food source. Our analysis showed that in Klaipėda, the eagles were probably used for raw material and possibly for feathers, but not for hawking and food. Alternatively, they could have been killed for scavenging. Other species identified in the assemblage such as chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus), grey partridge (Perdix perdix), geese (Anser sp.), ducks (Anatinae), and great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) were mainly interpreted as food waste. This article presents the first concentrated study on bird remains from Klaipėda and is one of the first discussions about the meaning of eagles in the Baltic region.

Keywords: eagles, Baltic region, bird remains, Klaipėda Castle, medieval, zooarchaeology.

Erelių reikšmė Baltijos regione. Vokiečių ordino pilies Klaipėdoje atvejis (XIII–XIV a.)

Anotacija. Šiame straipsnyje yra analizuojamos Klaipėdos pilyje rastos paukščių liekanos. Pilis čia pastatyta 1252 m. ir viduramžiais buvo šiauriausia Prūsijoje įsikūrusio Vokiečių ordino tvirtovė. Nors pilis ir aplink ją augantis miestas ne vieną šimtmetį kentėjo nuo karų ir kitų negandų, joje aptikti radiniai atskleidžia aukštą pilies gyventojų socialinį statusą. Tirti ir šioje publikacijoje pristatomi paukščių kaulai yra datuojami XIII a. pabaiga–XIV a. pradžia. Nors straipsnyje aptariamos visų pilyje rastų paukščių liekanos, daugiausia dėmesio skiriama dviem erelių rūšims – jūriniam (Haliaeetus albicilla) ir kilniajam (Aquila chrysaetos). Šiame straipsnyje pabandėme atsakyti į klausimus, kaip ereliai siejasi su socialiniu statusu, kaip ir kam jie naudoti, ar pilyje šie paukščiai galėjo būti valgomi. Atlikti tyrimai atskleidė, kad Klaipėdoje ereliai greičiausiai buvo laikomi dėl nagų ir plunksnų, o ne kaip medžiokliniai paukščiai ar maistui. Gali būti, kad jie sumedžioti tiesiog kaip kenkiantys plėšrūnai. Kitų Klaipėdos pilyje aptiktų paukščių – vištos (Gallus gallus domesticus), kurapkos (Perdix perdix), tikrųjų žąsų genties (Anser sp.) ir antinių šeimos (Anatinae) paukščių bei didžiojo kormorano (Phalacrocorax carbo) – liekanas galima interpretuoti kaip maisto atliekas. Šis straipsnis yra pirmoji Klaipėdoje rastiems paukščiams skirta publikacija ir vienas iš pirmųjų svarstymų apie erelių reikšmę Baltijos regione.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: ereliai, Baltijos regionas, paukščių liekanos, Klaipėdos pilis, viduramžių, zooarcheologija.

Received: 12/10/2020. Accepted: 02/12/2020

Copyright © 2020 Freydis Ehrlich, Giedrė Piličiauskienė, Miglė Urbonaitė-Ubė, Eve Rannamäe. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The history of the Klaipėda Castle

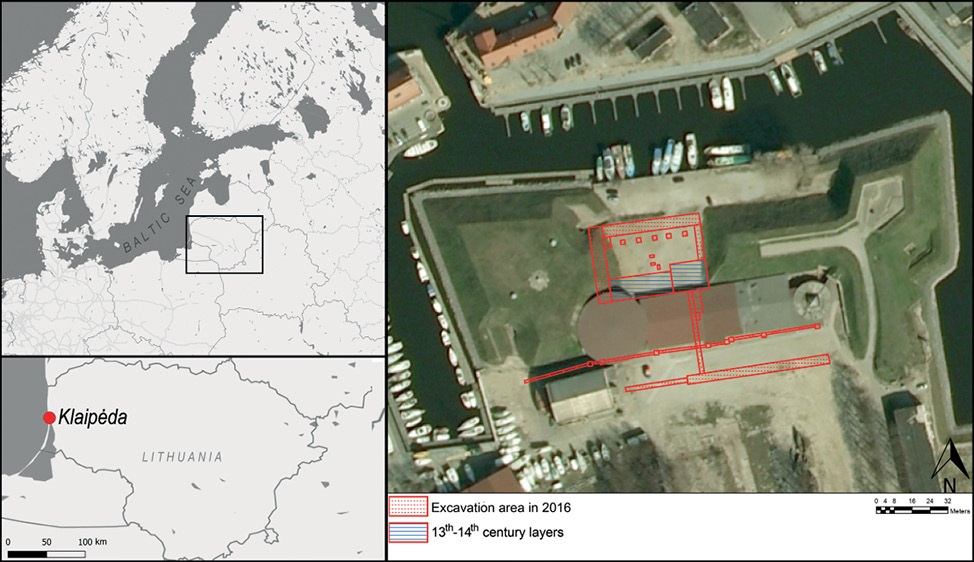

Klaipėda (Ger. Memel) is located in western part of modern Lithuania (Fig. 1). Klaipėda Castle was built in 1252 by the Livonian Order and in 1328 was passed over to the Teutonic Order, which made it the Order’s northernmost castle in Prussia (Žulkus, 2002, p. 7; Žulkus and Daugnora, 2009, p. 74).

Fig. 1. The location of Klaipėda and the excavation area in the Klaipėda Castle in 2016. The studied bird bones were found in the 13th–14th century layer. Map data: Snazzy Maps and Google, Maxar Technologies. Drawing by Freydis Ehrlich and Miglė Urbonaitė-Ubė.

1 pav. Klaipėdos pilies ir 2016 m. čia vykdytų archeologinių tyrimų situacijos planas. Paukščių kaulai rasti XIII–XIV a. sluoksniuose (žemėlapio duomenys: „Snazzy Maps“ ir „Google“, „Maxar Technologies“, F. Ehrlich ir M. Urbonaitės-Ubės pav.)

Around the same time as the castle, a small town was built nearby. The town and the castle integrated each other, because the town was also under the control of the knights and provided them with all necessary goods, food, and equipment (Žulkus, 2002, p. 29). The political intention for Klaipėda was to make it a regional centre with a cathedral and bishop’s residence (Ubis, 2018, p. 170). Subsequently, in 1257–1258, Klaipėda was granted Lübeck city rights (Kisielienė et al., 2012, p. 1004–1005), but at the end of the 13th century, a further urban and economic development and political plans failed. The main reasons were the wars with local Curonians, Samogitians, and Lithuanians; additionally, the country was ravaged by mutual marches between the Order and Grand Duchy of Lithuania (Žulkus and Daugnora, 2009, p. 75). Between 1255–1472, the castle was attacked almost every ten years (Žulkus and Daugnora, 2009, p. 77). Therefore, until the mid-15th century, its economic power weakened, and Klaipėda’s inhabitants are known to have supplied food and other items over the southern Baltic shores (Žulkus and Daugnora, 2009, p. 75). Regardless of the attacks and need to foray, the inhabitants in Klaipėda lived equally well compared to other medieval western European towns as evidenced by artefacts found from the site.

Due to wars and changing political situations, the town remained small and united with the castle until the 15th/16th century, when it was moved to the territory of today’s old town of Klaipėda (Žulkus, 2002, p. 29). Therefore, the Klaipėda Castle area we know today actually includes both the castle and the first phase of the medieval town and this is also the context of the current study (hereafter referred to as castle).

Faunal remains from the 2016 excavations

The history of the Klaipėda Castle has been studied by extensive archaeological excavations since 1968 and the fieldwork is still ongoing (Zabiela, 2019, p. 8, 11). The faunal material discussed in this paper was excavated in 2016 in the northern part of the castle. In total, 1598.5 square meters were excavated and late 13th to early 16th century structures uncovered (Zabiela, 2017, p. 42, 83; Zabiela et al., 2017, p. 185). The most significant finds of wooden buildings, platforms, and a well came from late 13th to early 14th century layers (Zabiela, 2017, p. 42, 57). These structures can be associated with the town part of the castle area, and therefore, with the early settlers of Klaipėda (Ubis, 2018, p. 170). Prior this fieldwork only fragments of 13th–14th century structures had been uncovered and this was the first time when a more detailed analysis of medieval structures and artefacts could be done.

In total, 2439 mammal, 439 fish, and 75 bird remains were found in the same layers of the 13th to early 14th century, dated by stratigraphy and artefacts (Table 1; Zabiela et al., 2017, p. 184–185). Of the mammal remains, 93% belonged to domestic and 7% to wild animals. The proportion of wild animals was higher than in other medieval sites and towns in Lithuania, but quite typical for residency of a higher social status, where the remains of game are usually abundant (Piličiauskienė and Blaževičius, 2018, p. 47–48). Among the fish bones, almost all were those of freshwater species that are known to have been preferred by the nobles in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the 14th to 17th century (Piličiauskienė, Blaževičius, 2019). Additionally, two cod (Gadus morhua) specimens were found, probably of nonlocal origin based on their size (see Orton et al., 2011) – in this case these are the first remains of medieval marine fish in the territory of modern Lithuania.

The size of the analysed bird bone sample was relatively small – 75 bones (2.5% of all zooarchaeological material), but bird bones from Klaipėda in general are very scarce. In previous research, only around 40 specimens and three taxa (chicken, goose, duck) from various temporal contexts have been briefly mentioned (Bilskienė and Daugnora, 2001a; Masiulienė, 2009). There could be two possible reasons behind the small number of birds. First of all, the sample size could be biased due to the excavation method, where osteological material was collected only by hand. However, the collection seems to have been careful, because many small specimens, including fish bones were recovered. The second reason for the small number of bird remains could lie in the past consumption patterns – namely, birds seem not to have been a significant part of the diet during the Middle Ages in Lithuania. Overall, the 2.5% of bird bones, as we see in the analysed assemblage from Klaipėda, are quite normal for Lithuanian faunal material. In the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, birds were quite expensive food, and peasants consumed fowl rarely (Dambrauskaitė, 2018; 2019, p. 156–159; Laužikas, 2014). Usually birds form around 1% of the medieval zooarchaeological assemblages from towns and settlements and around 3–5% in high status sites like manors and castles (Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 108–109). As a comparison, in the 13th to mid-14th century Vilnius Lower Castle, 1.8% of the zooarchaeological material were birds, and by the mid-16th and 17th century, their proportion had increased to 8.2% (Piličiauskienė and Blaževičius, 2018, tab. 1). Similar trend of increasing fowl consumption throughout the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period can be seen in other Lithuanian sites (e.g. Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 108–109; Piličiauskienė, unpublished data) and also in Poland (Makowiecki, 2009; Makowiecki et al., 2013; Dembińska, 1999).

Importance and aims of the study

Although based on small numbers, an elaborated analysis of Klaipėda material significantly complements the information about the lifestyle of the castle inhabitants and the overall usage and meaning of birds during the study period. New qualitative data is important not only for the history studies of Klaipėda and Lithuania, but in a much broader sense, because bird remains in the Baltic region have been studied only in small extent (as discussed in Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 104, 108; Maldre et al., 2018, p. 1229; Ehrlich et al., 2020). In the three Baltic countries – Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia – there is a considerable amount of bird bones stored in the osteological collections, but they are usually not analysed in detail and are only briefly mentioned in the publications. In Lithuania, only few papers focus solely on bird bones (e.g. Bilskienė and Daugnora, 2000; 2001a; 2001b; Daugnora et al., 2002; Blaževičius et al., 2012; Blaževičius and Kalėjienė, 2014; Rumbutis et al., 2018), and in some cases, bird bones have been added to a broader scientific analysis (e.g. Stančikaite et al., 2009) or only briefly mentioned (e.g. Masiulienė, 2009; Žulkus and Daugnora, 2009). In Latvia and Estonia, few detailed studies have been conducted (e.g. Mannermaa and Lõugas, 2005; Mannermaa, 2013; Maltby et al., 2019). In Estonia, where the overall number of bird studies has been increasing, the meaning and usage of eagles in archaeological context have also been discussed by Maldre et al. (2018) and shortly by Jonuks and Rannamäe (2018).

With this paper we contribute to the research of archaeological bird remains in the Baltic region by introducing one specific assemblage from the Klaipėda Castle in Lithuania. The analysed bones come from a narrow time frame from the end of the 13th to the beginning of the 14th century, that is, from the beginning of the Middle Ages. There were altogether 75 bird bones in the analysed assemblage, which is too little to discuss the overall proportion and diversity of the utilised bird species in that time period. However, the assemblage is exceptional, because it consists several eagle bones with clear indications of human use and thus presents an excellent possibility to look into the role of eagles in human–bird interaction. Therefore, the main aim of this paper is to discuss the complex meaning of eagles in the Baltic region during the Middle Ages, and to compare them to the preceding and following periods of the Late Iron Age and Early Modern Period in order to provide a better understanding of how the relationship between the people and eagles has developed in the past.

Material and methods

In total, 75 bird bones and bone fragments were studied. The identifications were based on morphology, using the reference collections of the Department of Archaeology and the Natural History Museum at the University of Tartu, Estonia, and a personal reference collection of Ülo Väli (Estonian University of Life Sciences). Morphologically very similar species were distinguished with the help of handbooks (Kraft, 1972; Bocheński and Tomek, 2009; Tomek and Bocheński, 2009). Geese bones were identified as Anser sp. and ducks were recorded as Anatinae – both groups include wild and potentially domestic species, because in their morphology and size they are almost indistinguishable. Additionally, cut marks were registered and traumas noted. For galliforms, sex was identified based on medullary bone for females and presence of spurs (usually) for males (for more detail, see Ehrlich et al., 2020). Measurements were taken after standards by von den Driesch (1976).

The results are presented as the total number of identified specimens (NISP), which includes both complete and fragmented bones, and the minimum number of individuals (MNI), which includes bones identified to species. The material is stored in the zooarchaeological collections of Vilnius University.

Results and discussion

Overview of the birds in the Klaipėda Castle

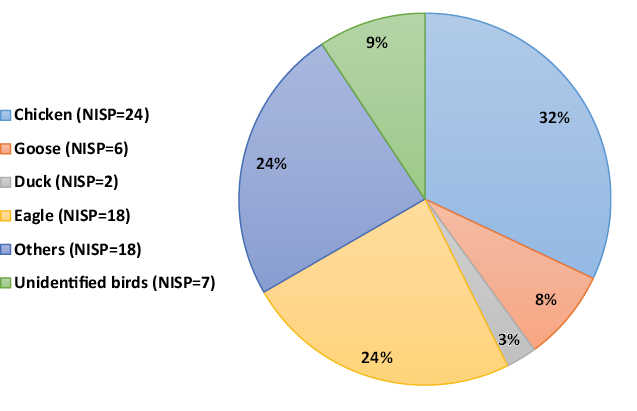

The bird bone assemblage from medieval Klaipėda included several species (Table 2; Table 3; Fig. 2). Most of them belonged to the orders galliforms and anseriforms and one individual to the order pelecaniforms. Interestingly, the material revealed a relatively large proportion of eagles in the order accipitriforms, who are the focus of this study and will be discussed in length below. Few specimens remained unidentified.

Table 2. The analysed bird taxa from the Klaipėda Castle. NISP – number of identified specimens; MNI – minimum number of individuals. Sex: F – female, M – male. Cut and gnaw marks, juveniles, and pathologies are presented as NISP.

2 lentelė. Klaipėdos pilyje rastų paukščių rūšinė sudėtis. NISP – identifikuotų kaulų skaičius; MNI – minimalus individų skaičius. Lytis – F – patelė, M – patinas. Kapojimo ir graužimo žymės, jauniklių skaičius bei patologijos nurodytos skaičiuojant identifikuotų kaulų skaičių

|

Taxon |

NISP |

MNI |

Sex |

Cut marks |

Gnaw marks |

Juveniles |

Pathologies |

|

|

No. of sp. |

% |

|||||||

|

Goose (Anser sp.) |

6 |

8 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ducks (Anatinae) |

2 |

3 |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

Unidentified anseriforms |

5 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

Domestic chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) |

24 |

32 |

5 |

3 F, 2 M |

6 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Grey partridge (Perdix perdix) |

2 |

3 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unidentified galliforms |

10 |

13 |

|

1 F |

2 |

|

2 |

|

|

Great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

White-tailed sea-eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) |

10 |

13 |

2 |

|

3 |

|

|

1 |

|

White-tailed sea-eagle / Golden eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla / Aquila chrysaetos) |

7 |

9,5 |

2 |

|

1 |

|

5 |

|

|

Eagle |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unidentified birds |

7 |

9,5 |

|

|

1 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

75 |

100 |

14 |

6 |

15 |

1 |

12 |

1 |

Table 3. Measurements of bird bones (mm). Measured after von den Driesch 1976. GL – greatest length; L – length of metacarpus II; Lm – medial length; BF – breadth of the basal articular surface; Bb – basal breadth; Bp – breadth of the proximal end; Dp – diagonal of the proximal end (includes Tp for femur); KC – smallest breadth of the corpus; Bd – breadth of the distal end (includes Dd for ulna and carpometacarpus and Bb for coracoid); Td – depth of the distal end. Juvenile birds and small fragments are excluded from the table.

3 lentelė. Paukščių kaulų matmenys (mm). Matavimai atlikti pagal Driesch, 1976. GL – didžiausias ilgis; L – plaštakos kaulo II ilgis; Lm – medialinis ilgis; BF – sąnarinio paviršiaus pagrindo plotis; Bb – pagrindo plotis; Bp – proksimalinio galo plotis; Dp – proksimalinio galo įstrižainė (šlaunikaulio kartu su Tp); KC – mažiausias kūno plotis; Bd – distalinio galo plotis (alkūnkaulio ir riešadelnio – ir Dd, varnakaulio – ir Bb); Td – distalinio galo gylis. Jauniklių kaulai ir smulkūs fragmentai į lentelę neįtraukti

|

Species |

Skeletal element |

Side |

GL |

L |

Lm |

BF |

Bp |

Dp |

KC |

Bd |

Td |

|

Anser sp. |

Ulna |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16,8 |

|

|

Anser sp. |

Phalanx proximalis digiti majoris |

dex |

40,8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anser sp. |

Tarsometatarsus |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19,2 |

|

|

Anser sp. |

Tarsometatarsus |

dex |

|

|

|

|

19,2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Anatinae |

Coracoideum |

sin |

|

|

|

20,1 |

|

|

|

19,1 |

|

|

Anatinae |

Ulna |

sin |

|

|

|

|

7,9 |

10,2 |

4,3 |

|

|

|

Anseriform |

Tarsometatarsus |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

11,1 |

|

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Coracoideum |

sin |

52 |

|

50,6 |

10,9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Humerus |

dex |

66,7 |

|

|

|

18,3 |

|

6,3 |

14,5 |

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Humerus |

sin |

64 |

|

|

|

18,5 |

|

6,5 |

14,4 |

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Ulna |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Ulna |

dex |

63,7 |

|

|

|

7,9 |

11,4 |

3,8 |

8,5 |

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Femur |

dex |

79,3 |

|

74,1 |

|

16,3 |

10,8 |

7,3 |

16,6 |

11,9 |

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Femur |

sin |

78,8 |

|

|

|

16,5 |

10,6 |

7,2 |

|

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tibiotarsus |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5,8 |

10,7 |

10,4 |

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tibiotarsus |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5,7 |

10,1 |

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tibiotarsus |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,3 |

|

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tibiotarsus |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

11,3 |

11,4 |

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tibiotarsus |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10,4 |

10,5 |

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tibiotarsus |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11,7 |

12,3 |

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tibiotarsus |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,6 |

|

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tibiotarsus |

sin |

115,7 |

|

111 |

|

|

10,8 |

7,3 |

11,6 |

12,4 |

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tarsometatarsus |

sin |

83,6 |

|

|

|

14,3 |

|

7,4 |

14,3 |

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tarsometatarsus |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7,4 |

14,3 |

|

|

Gallus gallus domesticus |

Tarsometatarsus |

sin |

72,6 |

|

|

|

13 |

|

6,5 |

12,3 |

|

|

Perdix perdix |

Humerus |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10,1 |

|

|

Perdix perdix |

Tibiotarsus |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,9 |

6,3 |

|

Galliform |

Tibiotarsus |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3,7 |

|

|

|

Galliform |

Tibiotarsus |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,9 |

|

|

|

Galliform |

Tibiotarsus |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,1 |

|

|

|

Phalacrocorax carbo |

Tarsometatarsus |

sin |

66,2 |

|

|

|

|

|

6,7 |

|

|

|

Haliaeetus albicilla |

Ulna |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17 |

|

|

Haliaeetus albicilla |

Carpometacarpus |

dex |

111,3 |

106,3 |

|

|

25,7 |

|

|

17,4 |

|

|

Haliaeetus albicilla |

Carpometacarpus |

dex |

115,3 |

111,1 |

|

|

26,1 |

|

|

17,8 |

|

|

Haliaeetus albicilla |

Femur |

sin |

127,3 |

|

120,9 |

|

28,2 |

17,1 |

14,2 |

29,1 |

21,2 |

|

Haliaeetus albicilla |

Femur |

dex |

127 |

|

120,1 |

|

27,8 |

16,7 |

|

28,4 |

20,7 |

|

Haliaeetus albicilla |

Tarsometatarsus |

sin |

101,4 |

|

|

|

24,8 |

|

13 |

28,4 |

|

|

Haliaeetus albicilla |

Tarsometatarsus |

sin |

101,6 |

|

|

|

23,3 |

|

|

26,3 |

|

|

Eagle |

Ulna |

sin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

9,7 |

16,8 |

|

|

Aves |

Tibiotarsus |

dex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

7,1 |

|

|

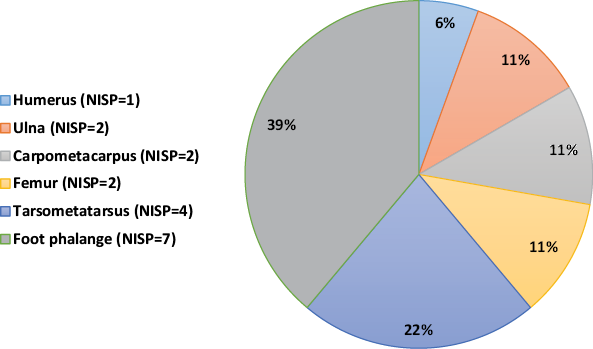

Fig. 2. Proportion of the analysed bird taxa from the Klaipėda Castle. For details, see Table 1. Drawing by Freydis Ehrlich.

2 pav. Klaipėdos pilyje rastų paukščių rūšinė sudėtis. Detalesnė informacija pateikta 1 lentelėje (F. Ehrlich pav.)

Chicken

Chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) was the most numerous taxon in the 13th to mid-14th century Klaipėda Castle. In medieval Lithuania chicken was the most commonly eaten bird (e.g. Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 115, tab. 7; Blaževičius et al., 2012, p. 316), but for Klaipėda it was previously thought that chicken breeding there became common only by the mid-16th century (Masiulienė, 2009, p. 102). Few juvenile bones among the analysed specimens even indicate on-site chicken husbandry. Breeding chicken in the castles was in general not exceptional: parallels are known, for example, from the medieval castles of Karksi in Estonia and Āraiši in Latvia, both with a considerable number of young chicken remains (Maltby et al., 2019, p. 156). In Klaipėda, the main reason for breeding chicken was most probably meat production, evidenced with cut marks on the bones from the meatier parts of the bird. Nevertheless, bones without cut marks were also likely food leftovers, since birds could have been cooked whole (Corbino and Albarella, 2019, p. 453). Even though no direct evidence such as egg shells were recorded, eggs were probably consumed as well. Three medullary chicken bones showed that egg-laying hens were present.

Geese and ducks

Generally, geese (Anser sp.) have been seen as expensive elite food with their bones found in the residences of wealthy people, e.g. castles and manors (Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 109). Geese were probably used not only for meat, but also for feathers, fat, and liver (Tikk et al., 2008, p. 105; Serjeantson, 2009, p. 298–299). Usually, geese and ducks (Anatinae) have been the second and third most recorded birds in zooarchaeological material, like in the 14th to 16th century Vilnius Castle (Rumbutis et al., 2018, tab. 7; Blaževičius et al., 2012, p. 316) or in the medieval and early modern Viljandi Castle in Estonia (Ehrlich et al., 2020). However, in case of Klaipėda, eagles were the second most numerous group after the chicken, while geese and ducks were in the third and fourth position, respectively. Here a small sample size of only 75 bones might have distorted those proportions, because in a previous research regarding Klaipėda (although with a small sample size as well), geese and ducks have been in the second and third position among the listed taxa. For example, from the mid- and second half of the 15th century castle, there were few chicken and goose bones (Bilskienė and Daugnora, 2001a, p. 255), and from the mid-16th to the second half of the 17th century town there were chicken, goose, and duck bones (Masiulienė, 2009, p. 102–103).

Wild resources

Game animals and birds have been associated with people of higher social status in the Baltic region, and in Europe in general (Michael, 1970; Manning, 1993; Zarankaitė-Margienė, 2018; Piličiauskienė and Blaževičius, 2018, p. 47–48; Ehrlich et al., 2020). Furthermore, historical records and isotopic data have shown that they were absent in the diet of medieval Prussian-Lithuanian peasants (Skipityė et al., 2020). For the Klaipėda Castle, it is known that the people provisioned themselves with game from Lithuania and Prussia (Žulkus and Daugnora, 2009, p. 77). It is unknown where exactly the wild birds analysed in this assemblage originated from, but they were both from aquatic and terrestrial environments. The wild species represented were ducks, grey partridge (Perdix perdix), cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo), and eagles; and the geese could be wild as well. It is known that among other birds, the partridges and ducks were hunted up until the 18th century on the Curonian Spit (Žulkus and Daugnora, 2009, p. 77). Among them, the grey partridge has been referred to as an expensive bird associated with the table of an upper class (Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 103; Dambrauskaitė, 2018, p. 223–228) – this seems to apply also to other medieval castles like Vilnius and Viljandi, where its bones have been found (Rumbutis et al., 2018, 123; Ehrlich et al., 2020).

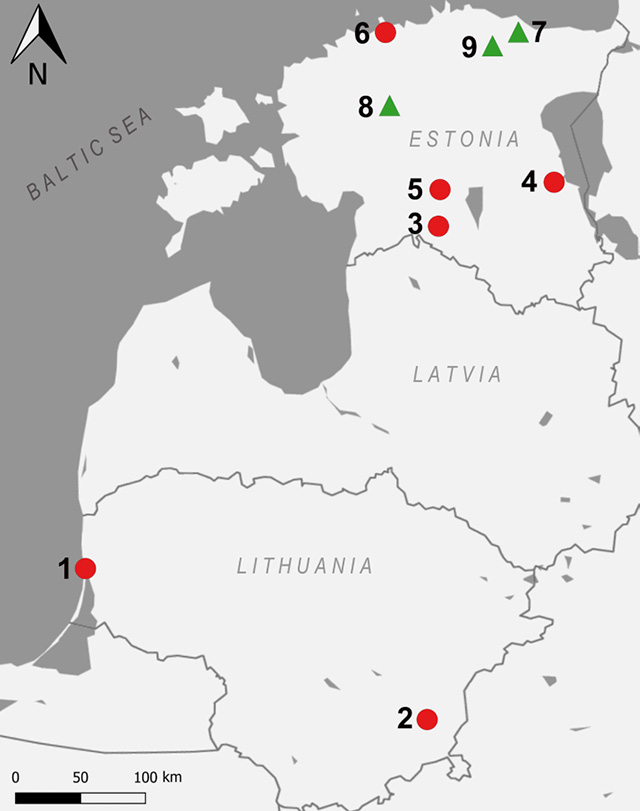

The eagles

In Klaipėda, eagles alone formed 23% of all analysed bird bones. Compared to the Vilnius Castle, where game birds, including the eagles, comprised only 1% (NISP = 2 out of the total 1355 bird bones; Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 119, tab. 7), the difference is remarkable. As mentioned before, the percentage might be distorted because of the small sample size, but it is nevertheless informative. About half of the identified eagle bones belonged to the white-tailed sea-eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla). Another half was not clearly identifiable and was attributed to whether white-tailed sea-eagle or golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), and one bone might belong to smaller eagle as well. Both white-tailed sea-eagle and golden eagle have been present in other archaeological sites in the Baltic region. In Lithuania, for example, the golden eagle has been recorded in the Vilnius Castle, where two bones of a male individual (sternum and tarsometatarsus, unpublished data by Rumbutis and Piličiauskienė) were found from the 14th–17th century material (Fig. 3.; Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 211); the white-tailed sea-eagle has been found only in a few Stone Age sites (Bilskienė and Daugnora, 2000). In Estonia, the white-tailed sea-eagle has been present, for example, in Late Iron Age Pada cemetery and Iru hillfort, medieval Karksi Castle1, medieval and early modern Viljandi Castle, and early modern Viljandi suburb (Luik, 2003, p. 162, 166; Luik and Maldre, 2005, p. 269; Maldre et al., 2018, p. 1233; Maltby et al., 2019, tab. 6.1; Ehrlich et al., 2020), while both the white-tailed sea-eagle and golden eagle have been present in Late Bronze Age Asva hillfort (Maldre et al., 2018, p. 1233). No data are known from Latvia – probably the bones of these two species are still undiscovered or unpublished. The material from Klaipėda is particularly interesting, because there were specimens with cut marks and one with pathology (Table 2), providing information on the variety of how the eagles might have been used in the past.

Fig. 3. Archaeological sites mentioned in the text, where the remains of the white-tailed sea-eagle and/or golden eagle have been found. Bone finds are marked with a red circle, pendants with a green triangle: 1 – Klaipėda Castle; 2 – Vilnius Castle; 3 – Karksi Castle; 4 – Kastre Castle; 5 – Viljandi Castle; 6 – Iru hillfort; 7 – Pada hillfort; 8 – Linnaaluste III settlement site; 9 – Rakvere settlement site. Map data: Snazzy Maps and QGIS. Drawing by Freydis Ehrlich and Ragnar Saage.

3 pav. Tekste minimos archeologinės vietovės, kuriose rasta jūrinių ir (ar) kilniųjų erelių kaulų. Kaulų radimo vietos pažymėtos raudonu apskritimu, kabučių radimo vietos – žaliu trikampiu: 1 – Klaipėdos pilis; 2 – Vilniaus pilis; 3 – Karksi pilis; 4 – Kastre pilis; 5 – Viljandi pilis; 6 – Iru piliakalnis; 7 – Pada piliakalnis; 8 – Linnaaluste III gyvenvietė; 9 – Rakvere gyvenvietė (žemėlapio duomenys: „Snazzy Maps“ ir QGIS, F. Ehrlich ir R. Saage pav.)

Eagles as scavengers

Golden eagles are unlikely to live in urban settlements as they nest in the forests and on cliffs, well away from people (Mulkeen and O’Connor, 1997, p. 442; Holmes, 2020, p. 77). On the other hand, the natural occurrence of white-tailed sea-eagles overlaps with human habitation, which might be the reason why they are more abundant in the archaeological material than the golden eagle (Bochenski et al., 2016, p. 665; Holmes, 2020; Mulkeen and O’Connor, 1997, p. 441–442; Serjeantson, 2009, p. 376). White-tailed sea-eagles have known to be commensal at least since the beginning of animal husbandry, which provided them with carcasses to scavenge on (Serjeantson, 2009, p. 376, 378). For example, in Poland, a clear predominance of the white-tailed sea-eagle, also of goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus), has been noted since the Middle Ages, which has been connected to the increased number of settlements and higher amount of human refuse (Bochenski et al., 2016, p. 665). In some countries, like in the Netherlands, the historical sources show that the white-tailed sea-eagle was seen as a pest: there were rewards for killing them and their nests were destroyed as soon as they started nesting (Zeiler, 2019). Similar explanation has been suggested for the eagle bones found in Novgorod, Russia (Hamilton-Dyer, 2002, p. 104). For Klaipėda, it remains unclear if eagles were killed as scavengers, but as discussed below, other explanations seem more plausible.

Hawking

In hawking, mainly falcons and hawks are used, also other Accipitridae like eagles. The golden eagle is widely used for this sport in the open landscapes of Central Asia, but rarely in Europe (Serjeantson, 2009, p. 317; Bartosiewicz, 2012, p. 183), and although the white-tailed sea-eagle is far less suited for hunting, it has been mentioned to be popular among falconers in Russia (Bartosiewicz, 2012, p. 183). Eagles could bring down animals as big as roe deer or wolf (Bartosiewicz, 2012, p. 183), but they are useful for hunting also small game, like in Poland, where white-tailed sea-eagles were used for hare hunting (Makowiecki and Gotfredsen, 2002, p. 77). However, in Lithuanian wooded lands, eagles would not be very suitable because of their size (Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 121). Moreover, they would be too heavy to be carried on the fist, and therefore, smaller birds like goshawk, sparrowhawk, and falcon have been preferred in general (Prummel, 1997, p. 333). This seems to have been the case for Baltic area as well.

Historical sources about the 16th–17th century Prussia mention the most popular birds for falconry to have been the peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus), who were caught from Curonian Spit near Klaipėda (Bezzenberger, 1889, p. 30). Therefore, it is possible that falcons were used in the 13th–14th century Klaipėda as well. On the other hand, in Vilnius, the most popular bird for hawking has been the goshawk. This is demonstrated by a well-preserved partial skeleton and hawking equipment found in the castle (Blaževičius et al., 2012; Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 119, fig. 69). And from Estonia, there is a possible example of using sparrowhawks in the early modern Viljandi Castle (Ehrlich et al., 2020).

Feathers

In many archaeological sites, the white-tailed sea-eagle has been mainly represented by its wing bones, which has led to the idea of exploiting them for feathers. Feathers are known to have had a symbolic significance and they were highly desired in many cultures: feathers have been associated with qualities needed in hunting and warfare and with the hope of the raptor’s qualities to be imparted to the arrow (Serjeantson, 2009, p. 186, 188). Another reason has been more practical. In several regions like Germany, Novgorod in Russia, and Denmark, it has been suggested that cuts on wing bones point to the extraction of feathers, which were then used for decorative purposes and arrow fletching (Mulkeen and O’Connor, 1997, p. 443; Hamilton-Dyer, 2002, p. 104; Gotfredsen, 2014, p. 372). Cut marks have also been recorded on the wing bones of eagles from Estonia, from the medieval castle of Viljandi (Ehrlich, 2018, p. 43).

It seems that not only slaughtered birds were exploited for feathers. They could have also been kept captive for that purpose. For example, a 16th century book from Poland suggests keeping the birds in a special basket in order to obtain feathers two or three times a year (Makowiecki and Gotfredsen, 2002, p. 77). Also, in the Middle Volga region in Russia, the eagles have been thought to have been kept captive in special aviaries for the use of feathers and ritual purposes (Galimova et al., 2014, p. 353).

Eagles could have been hunted for feathers in Lithuania too (Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 123), although in Klaipėda, there were no cut marks recorded on their wing bones and thus their exploitation for this purpose remains unclear. However, the use for feathers cannot be ruled out, because the osteological evidence is scarce (only few wing bone specimens were present) or the feathers were deplumed from live birds, leaving no marks on the bones.

Cut marks, claws, and pendants

In the Baltic countries, eagle bones with cut marks and pendants made of distal phalanges – the claw bones – are relatively rare. They are known only from Estonia, while in Latvia and Lithuania they are probably still undiscovered or unpublished.

In Estonia, eagle bones with cut marks on hindlimb have been found from the Late Bronze Age Asva hillfort, where phalanges and claws dominate, and to those with cut marks a ritual meaning or practical purpose have been attributed (Maldre et al., 2018, p. 1236). Cuts have also been recorded on tarsometatarsi of smaller Accipitridae from the Late Iron Age and Early Modern Period (Rannamäe and Lõugas, 2019, p. 72; Ehrlich et al., 2020). The above given examples might be related to separating talons from the legs and could therefore be indirect evidence for making pendants.

Eagle claws have their own meaning and their use for decoration and talismans has been widespread (Serjeantson, 2009, p. 225). Raptor claws are larger and more distinctive than those of the other birds and they have been associated with power and hunting skill of the hunters (Serjeantson, 2009, p. 225). The claw bones have been found as parts of necklaces or as isolated finds in contexts where they appear to have been collected or worn (Serjeantson, 2009, p. 225). For Estonian Late Iron Age (800–1250), it has been suggested that wearing pendants could have been more valued during the person’s lifetime and not in the afterlife, which is why pendants are sparse in graves, but more often present in settlement sites (Luik, 2010a, p. 50). Not only the distal, but also proximal and medial phalanges of birds of prey seem to have been worn or used as amulets, often carrying scrape marks from cleaning (Serjeantson, 2009, p. 226).

Several examples of claw pendants made from white-tailed sea-eagle bones are known from Estonia, all from the Late Iron Age: Linnaaluste III settlement site, Pada cemetery, and Rakvere settlement site (Konsa et al., 2003, fig. 4; Luik, 2003, p. 162; Luik and Maldre, 2005, p. 269; Maldre et al., 2018, p. 1233; Malve et al., 2020). Amulets or ornaments made of white-tailed sea-eagle claws are also known from the Middle Volga region in Russia (Galimova et al., 2014, p. 353). It seems that in Estonia during the Late Iron Age, both domesticated species like the chicken and birds of prey like the white-tailed sea-eagle and osprey were valued for pendants (Jonuks and Rannamäe, 2018, p. 170). Important symbolic meaning of the eagles is also evidenced by eagle-headed handles from the late 12th or early 13th century Estonia, of which two are made of bronze (from Kolu and Otepää) and one of antler (from Lõhavere); similar handles have been found in Visby in Sweden, and Karjala, Ladoga, and Novgorod in Russia (Mandel, 2003, p. 63–64; Luik, 2010b, p. 130; Mäesalu, 2014, p. 26–29; Jonuks and Rannamäe, 2018, p. 174; Maldre et al., 2018, p. 1239).

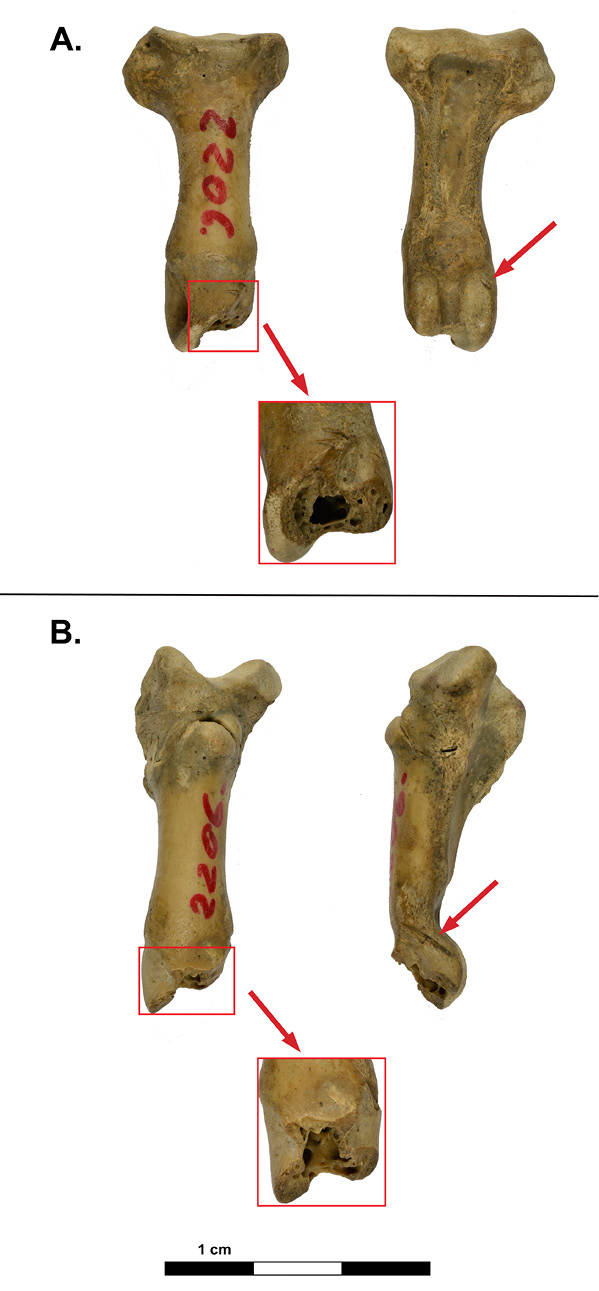

In the Klaipėda Castle, in total four eagle bones – two tarsometatarsi and two phalanges – had cut marks (Fig. 4; Fig. 5). It is important to note that in general, bones from the hindlimb dominated with as many as 72% (Fig. 6.). A large proportion of hindlimb elements is not a unique feature, the same has been noted in other archaeological sites in Europe (e.g. in Germany, see Mulkeen and O’Connor, 1997, p. 443). In Klaipėda, the abundance of hindlimb bones and cut marks on four of them could be an indirect evidence for extracting the talons.

Fig. 4. Two tarsometatarsi with cut marks: A – tarsometatarsus of a white-tailed sea-eagle with cut marks on the lateral side; B – tarsometatarsus of a juvenile white-tailed sea-eagle/golden eagle with proximal-lateral part cut through. Photo by Freydis Ehrlich and Eve Rannamäe.

4 pav. Du pastaibio kaulai su dorojimo žymėmis: A – jūrinio erelio su įkartomis lateralinėje kaulo pusėje; B – jauno jūrinio erelio arba kilniojo erelio pastaibis nukirsta proksimalinio galo lateraline dalimi (F. Ehrlich ir E. Rannamäe nuotr.)

Fig. 5. Two proximal phalanges of a white-tailed sea-eagle with cut marks: A – proximal phalanx with cut marks on the plantar side; B – proximal phalanx with cut marks on the lateral side. Photo by Freydis Ehrlich and Eve Rannamäe.

5 pav. Du jūrinio erelio proksimaliniai pirštakauliai su kirtimo žymėmis: A – proksimalinis pirštakaulis su įkartomis plantarinėje pusėje; B – proksimalinis pirštakaulis su įkartomis lateralinėje pusėje (F. Ehrlich ir E. Rannamäe nuotr.)

Fig. 6. Proportion of the analysed eagle bones by skeletal element from the Klaipėda Castle. Drawing by Freydis Ehrlich.

6 pav. Klaipėdos pilyje rastų erelių kaulų anatominis pasiskirstymas (F. Ehrlich pav.)

Other explanations for cut marks are also possible. Eagles have been suggested to have been eaten in prehistoric northern Europe (Mannermaa, 2003, p. 19 and references therein), also in medieval Europe like in the 12th–13th century Kána, Hungary (golden eagle tibiotarsus with cut marks; Daróczi-Szabó, 2014, p. 542), 15th–16th century Kastre Castle, Estonia (femur of a white-tailed sea-eagle; Lõugas et al., 2019, p. 434, 437), and 16th–18hth century Malbork Castle, Poland (coracoid of a cf. white-tailed sea-eagle; Pluskowski et al., 2009, p. 194, 211). Moreover, such powerful birds like eagles were included in cookbooks and might have been a “must” in characterising the imperial glory in England (Bartosiewicz, 2012, p. 184). However, for the eagles in the Klaipėda Castle, cut marks were positioned on bone elements poor in meat – tarsometatarsus and phalanges – which means that exploiting them for meat seems unlikely.

Pathologies

In the Klaipėda Castle, there was one pathological eagle bone: a white-tailed sea-eagle tarsometatarsus with pathological modification on the diaphysis (Fig. 7). It seems to be a case of healed bone fracture or some other trauma that has resulted in thickening of the bone (e.g. Gál, 2013, p. 219–223). Since bone reacts in a similar manner to most traumas, the exact cause here would be difficult to determine (Reitz and Wing, 2008, p. 171). A bird of prey with a fractured bone would not survive in the wild (Prummel, 2018, p. 470), and therefore, we could assume that the bird was kept captive. The same has been suggested for a case from medieval Staraya Ladoga, where a partial skeleton of a white-tailed sea-eagle showed pathological lesion both on carpometacarpus and tibiotarsus, and was therefore thought to have been kept captive in the settlement (Shaymuratova et al., 2019, p. 104–106). In Lithuania, there are no other examples of pathological eagle bones, but there is an almost complete skeleton of a goshawk from the end of the 14th century Vilnius Castle with some broken bones and few signs of healing (Blaževičius, Kalėjiene, 2014; Rumbutis et al., 2018, p. 119, fig. 69).

Fig. 7. Tarsometatarsus of a white-tailed sea-eagle with a pathology: A – dorsal side; B – lateral side. Photo by Freydis Ehrlich and Eve Rannamäe.

7 pav. Jūrinio erelio pastaibis su patologija: A – dorsalinė pusė; B – lateralinė pusė (F. Ehrlich ir E. Rannamäe nuotr.)

Conclusion

The analysed material from the Klaipėda Castle reflects bird exploitation in the 13th–14th century Lithuania and provides new data for a further discussion on bird utilisation in the Baltic region. The study revealed new species, which in Klaipėda had not been reported before, like the grey partridge, white-tailed sea-eagle/golden eagle, and great cormorant. The overall proportion of the bird bones compared to other faunal remains (mammals and fish) was quite high compared to other contemporaneous castles – even 2.5% – which could be associated with the elite. Among the chicken, geese, ducks, grey partridge, and great cormorant that were associated with meat consumption, the geese, ducks, and grey partridge in particular were those interpreted as being part of the diet of the higher social status. Regarding chicken, it had been previously thought that breeding them in Klaipėda became common only by the mid-16th century, but the presence of juvenile bones in the studied assemblage suggests that chicken might have been bred there already in the 13th–14th century.

The second most numerous group of birds besides chicken were the eagles. The use and meaning of the eagles is strongly related to the nature of the remains. In Klaipėda, only disarticulated bones were present, suggesting that the birds were used for a particular anatomical part. The domination of tarsometatarsi and foot phalanges further supported the idea of a specific use. Cut marks on those bones strongly indicate that birds were used for their claws. Using eagles for feathers or killing them as scavengers cannot be ruled out entirely either, but in Klaipėda, the use for hawking or meat seems unlikely.

Whether the eagle bones in Klaipėda could unambiguously be associated with activities by the higher social status, remains open. The overall archaeological context together with the rest of the faunal remains (including a relatively large proportion of game animals and the variety of species) seem to support that assumption. However, more analysis on the material from the medieval suburban and rural sites should be studied in order to see if the use of eagles could be expanded to other social strata as well.

Funding. This work was supported by the Estonian Research Council grant No PRG29.

Acknowledgements. We would like to thank Andrei Miljutin for access to the reference collection in the Natural History Museum at the University of Tartu, Ülo Väli for access to his personal reference collection and for confirming some uncertain identifications, Martin Malve for assistance in identifying the pathology, Liina Maldre for the help with literature, and Ragnar Saage for helping with the QGIS.

Bibliography

Bartosiewicz L. 2012. Show me your hawk, I’ll tell you who you are. D. C. Raemaekers, E. Esser and R. C. G. M. Lauwerier (eds.) A Bouquet of Archaeozoological Studies, Essays in honour of Wietske Prummel. Groningen: Bakhuis & University of Groningen Library, p. 179–187.

Bezzenberger A. 1889. Die Kurische Nehrung und ihre Bewohner. Forschungen zur deutschen Landes- und Volkskunde, band 3. Stuttgart.

Bilskienė R., Daugnora L. 2000. Paukščiai akmens amžiaus gyvenvietėse. A. Girininkas, V. Juodagalvis ir J. Stankus (sud.) Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje 1998 ir 1999 metais. Vilnius, Lietuvos istorijos institutas, p. 567–580.

Bilskienė R., Daugnora L. 2001a. Paukščiai Lietuvos pilyse. J. Genys ir V. Žulkus (sud.) Lietuvos pilių archeologija. Klaipėda: Klaipėdos universitetas, p. 251–259.

Bilskienė R., Daugnora L. 2001b. Osteometrinė vištų skeleto analizė. Veterinarija ir zootechnika, 16 (38), p. 15–30.

Blaževičius P., Kalėjiene J. 2014. Medieval Falconry – Archaeology and Reconstruction. Latvijas Restauratoru biedriba, p. 4–17.

Blaževičius P., Rumbutis S., Zarankaitė T. 2012. Medžiokliniai, medžiojamieji ir naminiai paukščiai Vilniaus pilyje XIV–XVI a. naujausių tyrimų duomenimis. Chronicon Palatii magnorum Ducum Lithuaniae, t. II (76). Nacionalinis muziejus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovų rūmai, Vilnius, p. 299–319.

Bocheński Z. M., Tomek T. 2009. An identification key for the remains of domestic birds in Europe. Preliminary determination. Krakow: Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Sciences.

Bochenski Z. M., Tomek T., Wertz K., Wojenka M. 2016. Indirect Evidence of Falconry in Medieval Poland as Inferred from Published Zooarchaeological Studies. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 26 (4), p. 661–669. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2457.

Corbino C. A., Albarella U. 2019. Wild birds of the Italian Middle Ages: diet, environment and society. Environmental Archaeology, 24 (4), p. 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2018.1516371.

Dambrauskaitė N. 2018. Mėsos ir žuvies vartojimo reikšmė Lietuvos didžiųjų kunigaikščių virtuvėje XV–XVII amžiaus pirmoje pusės rašytinių šaltinių duomenimis. Vilniaus pilių fauna: nuo kepsnio iki draugo. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, p. 215–242.

Dambrauskaitė N. 2019. Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės bajorų namai XVI a. – XVII a. pirmoje pusėje. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla.

Daróczi-Szabó M. 2014. Animal remains from the mid 12th–13th century (Árpád Period) village of Kána, Hungary. D. Bartus (ed.) Dissertationes Archaeologicae. Ex Instituto Archaeologico Universitatis de Rolando Eötvös nominatae. 3 (2). Budapest, p. 541–548.

Daugnora L., Bilskiené R., Hufthammer A. K. 2002. Bird remains from Neolithic and Bronze Age settlements in Lithuania. Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia, 45 (special issue), p. 233–238.

Dembińska M. 1999. Food and Drink in Medieval Poland. Rediscovering a Cuisine of the Past. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Ehrlich F. 2018. Linnud Viljandi keskaegses ja varauusaegses zooarheoloogilises materjalis. Unpublished MA thesis. Manuscript in the Institute of History and Archaeology at the University of Tartu.

Ehrlich F., Rannamäe E., Valk H. 2020. Bird exploitation in Viljandi (Estonia) from the Late Iron Age to the Early Modern Period (c. 950–1700). Quaternary International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.07.018.

Gál E. 2013. Pathological changes in bird bones. L. Bartosiewicz (ed.) Shuffling Nags, Lame Ducks. The Archaeology of Animal Disease. Oxford, Oakville: Oxbow Books, p. 217–238.

Galimova D. N., Askeyev I. V., Askeyev O. V. 2014. Bird Remains from 5th–17th Century AD Archaeological Sites in the Middle Volga Region of Russia. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 24 (3), p. 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2385.

Gotfredsen A. B. 2014. Birds in Subsistence and Culture at Viking Age Sites in Denmark. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 24, p. 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2367.

Hamilton-Dyer S. 2002. The bird resources of medieval Novgorod, Russia. Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia, 45 (special issue), p. 99–107.

Holmes M. 2020. Legends, legions and the Roman eagle. Quaternary International, 543, p. 77–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.02.006.

Jonuks T., Rannamäe E. 2018. Animals and worldviews: a diachronic approach to tooth and bone pendants from the Mesolithic to the Medieval period in Estonia. A. Livarda (ed.) The Bioarchaeology of Ritual and Religion. Oxbow Books, p. 162–178.

Kisielienė D., Masiulienė I., Daugnora L., Stančikaitė M., Mažeika J., Vaikutienė G., Petrošius, R. 2012. History of the environment and population of the Old Town of Klaipėda, Western Lithuania: multidisciplinary approach to the last millennium. Radiocarbon, 54 (3–4), p. 1003–1015.

Konsa M., Loolaid L., Lang V. 2003. Settlement site III of Linnaaluste from archaeological complex of Keava. Arheoloogilised välitööd Eestis 2002 / Archaeological fieldwork in Estonia 2002, p. 51–55.

Kraft E. 1972. Vergleichend morphologische Untersuchungen an Einzelknochen Nord- und Mitteleuropäischer kleinerer Hühnervögel. München: Institut für Paläoanatomie Domestikations forschung und Geschichte der Tiermedizin.

Laužikas R. 2014. Istorinė Lietuvos virtuvė. Vilnius: Briedis.

Luik H. 2003. Luuesemed hauapanustena rauaaja Eestis. V. Lang and Ü. Tamla (eds.) Arheoloogiga Läänemeremaades. Uurimusi Jüri Seliranna auks. Muinasaja teadus 13. Tallinn; Tartu, p. 153–172.

Luik H. 2010a. Beaver in the economy and social communication of the inhabitants of South Estonia in the Viking Age (800–1050 AD). A. Pluskowski, G. K. Kunst, M. Bietak and I. Hein (eds.) Bestial Mirrors. Using Animals to Construct Human Identities in Medieval Europe. Animals as Material Culture in the Middle Ages. Vienna: Vienna Institute for Archaeological Science, p. 46–54.

Luik H. 2010b. Linnupeakujuline sarvest käepide Lõhavere linnamäeld. Ü. Tamla (ed.) Ilusad asjad. Tähelepanuväärseid leide Eesti arheoloogiakogudest. Muinasaja teadus 21. Tallinn: Ajaloo Instituut, p. 125–138.

Luik H., Maldre L. 2005. Bone and antler artefacts from Pada settlement site and cemetery in North Estonia. H. Luik, A. M. Choyke, C. E. Batey and L. Lõugas (eds.) From Hooves to Horns, from Mollusc to Mammoth. Manufacture and Use of Bone Artifacts from Prehistoric Times to the Present. Proceedings of the 4th Meeting of the ICAZ Worked Bone Research Group at Tallinn, 26th–31th of August 2003. Muinasaja teadus 15. Tallinn, p. 263–276.

Lõugas L., Rannamäe E., Ehrlich F., Tvauri A. 2019. Duty on fish: Zooarchaeological evidence from Kastre Castle and customs station site between Russia and Estonia. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 29 (3), p. 432–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2764.

Mäesalu A. 2014. Kas Otepää linnuselt leiti muinaseestlaste sõjasarv? Tutulus: Eesti arheoloogia aastakiri, 2014, 26–29.

Makowiecki D., 2009. Animals in the landscape of the medieval country side and urban agglomeration of the Baltic Sea countries. A. Castagnetti (ed.) Cittá e campagna nei secoli altomedievali: Spoleto, 27 marzo – 1 aprile 2008. Settimane di studio del Centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo, 56/1, p. 427–444.

Makowiecki D., Gotfredsen A. B. 2002. Bird remains of Medieval and Post-Medieval coastal sites at the Southern Baltic Sea, Poland. Acta zoologica Cracoviensia, 45 (special issue), p. 65–84.

Makowiecki D., Tomek T., Bochenski Z. M., 2013. Birds in Early Medieval Greater Poland: Consumption and Hawking. L. Bejenaru and D. Serjeantson (eds.) Birds and archaeology: New research. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 24 (3), p. 358–364.

Maldre L., Tomek T., Peets, J. 2018. Birds of prey from Vendel Age ship burials of Salme (c. 750 AD) and in Estonian archaeological material. K.-H. Gersmann and O. Grimm (eds.) Raptor and human – falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale. Kiel: Wachholtz Murmann Publishers, p. 1229–1250.

Maltby M., Pluskowski A., Rannamäe E., Seetah K. 2019. Farming, hunting and fishing in Medieval Livonia: zooarchaeological data. A. Pluskowski (ed.) Environment, Colonisation and the Crusader States in Medieval Livonia and Prussia: Terra Sacra I. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, p. 136–174.

Malve M., Viljat J., Rannamäe E., Vilumets L., Ehrlich F. 2020. Archaeological fieldwork at the Rakvere St Michael’s churchyard and at Pikk Street. Arheoloogilised välitööd Eestis 2019 / Archaeological fieldwork in Estonia 2019, p. 189−212.

Mandel M. 2003. Läänemaa 5.–13. sajandi kalmed. Tallinn: Eesti Ajaloomuuseum.

Mannermaa K. 2003. Birds in Finnish Prehistory. Fennoscandia archaeologica XX, p. 3–39.

Mannermaa K. 2013. Powerful birds. The Eurasian jay (Garrulus glandarius) and the osprey (Pandion haliaetus) in hunter-gatherer burials at Zvejnieki, northern Latvia and Yuzhniy Oleniy Ostrov, northwestern Russia. Anthropozoologica, 48 (2), p. 189–205. https://doi.org/10.5252/az2013n2a1.

Mannermaa K., Lõugas L. 2005. Birds in the subsistence and cultures on four major Baltic Sea Islands in the Neolithic (Hiiumaa, Saaremaa, Gotland and Åland). G. Grupe and J. Peters (eds.) Feathers, Grit and Symbolism: Birds and Humans in the Ancient Old and New Worlds: Proceedings of the 5th Meeting of the ICAZ Bird working group in Munich 26.7–28.7.2004. Documenta Archaeobiologiae 3, p. 179–198.

Manning R. B. 1993. Hunters and Poachers. A Cultural and Social History of Unlawful Hunting in England 1485–1640. Oxford: Clarendon.

Masiulienė I. 2009. 16th–17th cen. Klaipėda town residents’ lifestyle (by archaeological, palaeobotanical, and zooarchaeological data of Kurpių street plots). Archaeologia Baltica, 12, p. 95–111.

Michael L. W. 1970. The history of German Game Administration. Forest Conservation History, 14 (3), p. 6–16.

Mulkeen S., O’Connor T. P. 1997. Raptors in Towns: Towards an Ecological Model. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 7 (4), p. 440–449.

Orton D. C., Makowiecki D., de Roo T., Johnstone C., Harland J., Jonsson L., Heinrich D., Enghoff I. B., Lõugas L., Van Neer W., Ervynck A., Hufthammer A. K., Amundsen C., Jones A. K. G., Locker A., Hamilton-Dyer S., Pope P., MacKenzie B. R., Richards M., O’Connell T. C. & Barrett J. H. 2011. Stable isotope evidence for late medieval (14th–15th c.) origins of the eastern Baltic cod (Gadus morhua) fishery. – PLoS ONE, 6: e27568.

Piličiauskienė G., Blaževičius P. 2018. Žinduoliai Vilniau pilyse. Vilniaus pilių fauna: nuo kepsnio iki draugo. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, p. 18–101.

Piličiauskienė G., Blaževičius P. 2019. Archaeoichthyological and historical data on fish consumption in Vilnius Lower Castle during the 14th–17th c. Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 23 (1), p. 39–55.

Pluskowski A., Maltby M., Seetah K. 2009. Animal Bones from an Industrial Quarter at Malbork, Poland: Towards an Ecology of a Castle Built in Prussia by the Teutonic Order. Crusades, 8, p. 181–212.

Prummel W. 1997. Evidence of Hawking (Falconry) from Bird and Mammal Bones. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 7 (4), p. 333–338.

Prummel W. 2018. The archaeological-archaeozoological identification of falconry – methodological remarks and some Dutch examples. K.-H. Gersmann and O. Grimm (eds.) Raptor and human – falconry and bird symbolism throughout the millennia on a global scale. Wachholtz: Murmann Publishers, p. 467–478.

Rannamäe E., Lõugas L. 2019. Animal Exploitation in Karksi and Viljandi (Estonia) in the Late Iron Age and Medieval Period. A. Pluskowski (ed.) Ecologies of Crusading, Colonization, and Religious Conversion in the Medieval Baltic: Terra Sacra II. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers, p. 61–76.

Reitz E., Wing E. 2008. Zooarchaeology. Second edition. Cambridge University Press.

Rumbutis S., Blaževičius P., Piličiauskienė G. 2018. Paukščiai Vilniaus pilyse. Vilniaus pilių fauna: nuo kepsnio iki draugo. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, p. 104–130.

Serjeantson D. 2009. Birds. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

Shaymuratova (Galimova) D., Askeyev I., Askeyev O. 2019. The Studies of Archaeological Bird Remains from Medieval Staraya Ladoga. New Results and Interpretations. K. Mannermaa, M. A. Manninen, P. A. P. Pesonen and L. Seppänen (eds.) Monographs of the Archaeological Society of Finland. Helsinki Harvest. Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Conference on the Application of Scientific Methods in Archaeology. Suomen arkeologinen seura, Helsinki, p. 93–114.

Skipitytė R., Lidén K., Eriksson G., Kozakaitė J., Laužikas R., Piličiauskienė G., Jankauskas R. 2020. Diet patterns in medieval to early modern (14th–early 20th c.) coastal communities in Lithuania. Anthropologischer Anzeiger, 77 (4), p. 299–312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1127/anthranz/2020/1092.

Stančikaite M., Daugnora L., Hjelle K., Hufthammer A. K. 2009. The environment of the Neolithic archaeological sites in Šventoji, Western Lithuania. Quaternary International, 207 (1–2), p. 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2009.01.012.

Tikk H., Tikk V., Piirsalu M. 2008. Linnukasvatus II. Eestis vähelevinud põllumajanduslinnud. Tartu: Tartu Põllumeeste Liit, Eesti Maaülikool.

Tomek T., Bocheński Z. M. 2009. A key for the identification of domestic birds in Europe: Galliformes and Columbiformes. Krakow: Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Siences.

Ubis E. 2018. Archaeological Data as Evidence of Cultural Interaction between the Teutonic Order and Local Communities: Problems and Perspectives. Archaeologia Baltica (25), p. 164–176.

von den Driesch A. 1976. Das Vermessen von Tierknochen aus vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Siedlungen. München: Institut dür Paläoanatomie, Domestikationsforschung und Geschichte der Tiermedizin der Universität München.

Zabiela G. 2017. Klaipėdos pilies (10303) 2016 m. detaliųjų archeologinių tyrimų ataskaita. Tyrimai. Vol. 1. Unpublished excavations report. Lithuanian institute of history, file 8452.

Zabiela G. 2019. History of Investigations at the Castle Site of Klaipėda. G. Zabiela (ed.) Klaipėdos pilis: tyrimai ir šaltiniai. Klaipėda, p. 8–9.

Zabiela G., Kraniauskas R., Ubis E., Ubė M. 2017. Klaipėdos pilies šiaurinė kurtina. Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje 2016 metais. Vilnius: Lietuvos archeologijos draugija, p. 183–193.

Zarankaitė-Margienė T. 2018. Laukiniai žvėrys Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės valdovo aplinkoje XIV–XVII amžiuje. Vilniaus pilių fauna: nuo kepsnio iki draugo. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, p. 246–273.

Zeiler J. T. 2019. The white-tailed eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) in the Netherlands: changing landscapes, changing attitudes. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 11 (12), p. 6371–6375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-018-0600-3.

Žulkus V. 2002. Viduramžių Klaipėda. Vilnius: Žara.

Žulkus V., Daugnora L. 2009. What did the Order’s brothers eat in the Klaipėda castle? (The Historical and zooarchaeological data). Archaeologia Baltica (12), p. 74–87.

Erelių reikšmė Baltijos regione. Vokiečių ordino pilies Klaipėdoje atvejis (XIII–XIV a.)

Freydis Ehrlich, Giedrė Piličiauskienė, Miglė Urbonaitė-Ubė, Eve Rannamäe

Santrauka

Publikacijoje aptariamos faunos lieknos, surinktos 2016 m. vykdant Klaipėdos pilies šiaurinės dalies archeologinius tyrimus (1 pav.). Jų metu iškastas 1 598,5 m2 plotas ir aptiktos XIII a. pabaigos–XVI a. pradžios struktūros, iš kurių itin reikšmingos – XIII a. pabaigos–XIV a. pradžios medinių pastatų bei kitų statinių lieknos (Zabiela, 2017; Zabiela et al., 2017). Jas galima sieti su šalia pilies besikuriančiu miestu ir pirmaisiais jo gyventojais (Ubis, 2018).

XIII a. pabaigos–XIV a. pradžios sluoksniuose ir struktūrose buvo aptikti 2 439 žinduolių, 439 žuvų ir 75 paukščių kaulų fragmentai (1 lentelė). Naminiams gyvuliams priklausė 93 %, laukiniams gyvūnams – 7 % identifikuotų žinduolių kaulų, t. y. laukinių gyvūnų pilyje aptikta daugiau negu įprastai randama viduramžių piliakalniuose ir gyvenvietėse. Didesnė laukinių gyvūnų dalis yra būdinga vietovėms, kuriose rezidavo aukštesniojo socialinio statuso atstovai (Piličiauskienė, Blaževičius, 2018). Beveik visos žuvų liekanos buvo gėlavandenių žuvų, tačiau du kaulai buvo stambių, greičiausiai nevietinės kilmės menkių ar menkės (Gadus morhua) skeletų liekanos. Minėti menkių kaulai yra prmosios šiuolaikinės Lietuvos teritorijoje aptiktos viduramžių jūrinių žuvų liekanos.

Paukščių kaulų rasta palyginti nedaug – 75 vnt., t. y. 2,5 % visos zooarcheologinės medžiagos. Nors tai nėra daug, tačiau iki šiol buvo ištirta vos 40 Klaipėdoje rastų paukščių kaulų (Bilskienė, Daugnora, 2001a; Masiulienė, 2009), be to, Klaipėdos pilyje surinkta paukščių kaulų kolekcija išskirtinė – joje itin daug erelių kaulų, kai kurie jų – su kapojimo žymėmis. Todėl pagrindinis šio straipsnio tikslas ir yra aptarti, kam ir kaip ereliai buvo naudojami Baltijos regione viduramžiais.

Dauguma ištirtų kaulų priklausė vištiniams ir žąsiniams paukščiams, vienas individas buvo irklakojų būrio atstovas (2 ir 3 lentelės, 2 pav.). Vis dėlto įdomiausia, kad nemažai kaulų priklausė vanaginių būrio paukščiams – ereliams. Daugiausia pilyje aptikta vištų kaulų. Vištos buvo populiariausias paukštis ir viduramžių Lietuvoje. Jauniklių kaulai rodytų, kad vištos pilyje turėjo būti ir veisiamos. Keletas kaulų priklausė patelėms, tai liudytų pilyje buvus ir kiaušinius dedančių vištų. Žąsų ir ančių kaulų rasta nedaug, pagal gausą jos užėmė trečią ir ketvirtą vietas, nors paprastai užima atitinkamai antrą ir trečią pozicijas, o daugiausia žąsinių paukščių yra aptinkama turtingesnių žmonių aplinkoje. Antri pagal gausą paukščiai Klaipėdos pilyje – ereliai. Laukiniai paukščiai ir apskritai laukiniai gyvūnai tiek Baltijos regione, tiek Europoje yra siejami su elito aplinka, o Klaipėdos pilyje laukinių paukščių kaulų rasta daug ir įvairių – ne tik erelių, bet ir ančių, kurapkų, didysis kormoranas, laukinės galbūt buvo ir žąsys. Erelių kaulai sudarė net 23 % visų paukščių kaulų. Palyginimui – Vilniaus žemutinėje pilyje plėšriųjų paukščių kaulai apskritai sudarė vos 1 % paukščių kaulų (Rumbutis et al., 2018). Kiek daugiau negu pusė erelių kaulų priklausė jūriniam ereliui. Likusiųjų tiksliai identifikuoti nepavyko, jie jūrinio arba kilniojo erelio. Vienas kaulas priklausė mažesniam ereliui. Keletas erelių kaulų buvo su kapojimo žymėmis, vienas – su patologija (2 lentelė).

Kaulų dorojimo žymės ir pažeidimai yra geriausios tiesioginės nuorodos, kam ereliai galėjo būti naudojami. Pirmiausia galima atmesti mažiausiai tikėtiną jų paskirtį – vargu ar pilyje rasti ereliai buvo skirti medžioklei. Mat su kilniaisiais ereliais Europoje medžiota retai, paprastai su jais medžiojama atvirose vietovėse Centrinėje Azijoje, dėl miškingų vietovių Baltijos regione šie paukščiai medžioklei visai netiko. Žinoma, kad jūriniai ereliai aplinkiniuose kraštuose (Lenkijoje, Rusijoje) kartais naudoti medžioklei, tačiau jiems taip pat reikia atvirų, o ne miškingų vietovių, tad sunkiai tikėtina, kad šie paukščiai galėjo būti skirti medžioklei.

Ereliai taip pat galėjo teikti plunksnas. Plunksnos naudotos strėlių gamyboje ir kaip puošybos elementas, todėl gyvenvietėse dažnai randama erelių sparnų kaulų su kapojimo žymėmis. Lenkijoje ir Rusijoje dėl plunksnų ereliai buvo specialiai laikomi nelaisvėje (Makowiecki, Gotfredsen, 2002; Galimova et al., 2014). Negalima atmesti, kad Klaipėdoje rasti ereliai sumedžioti ar laikyti būtent dėl plunksnų, juo labiau kad laikymą nelaisvėje rodytų ir rastas traumuotas erelio kaulas. Tikėtina, kad ereliai galėjo būti medžiojami dėl pirštakaulių, iš kurių gaminti kabučiai. Kabučiai iš erelių nagų (distalinių pirštakaulių), o kartais ir pirmųjų bei antrųjų pirštakaulių vertinti kaip amuletai ir nešioti įvairiuose kraštuose, taip pat netolimoje Estijoje (Serjeantson, 2009; Luik, 2010a; Galimova et al., 2014; Konsa et al., 2003; Luik, 2003). Tiesa, Lietuvoje ir Latvijoje tokia tradicija iki šiol nežinoma.

Klaipėdos pilyje keturi erelių kaulai – du pastaibiai ir du pirštakauliai – buvo su kapojimo žymėmis (4 ir 5 pav.), be to, kojų kaulai apskritai dominavo (72 %) tarp visų erelių liekanų (6 pav.). Didelė erelių kojų kaulų dalis, ant jų likusios kapojimo žymės ir įkartos rodytų, kad greičiausiai buvo naudoti erelių nagai. Dar viena galima erelių paskirtis – mėsa. Ereliai Europoje valgyti įvairiais laikais, tokius atvejus liudija kapoti jūrinių ir kilniųjų erelių kaulai iš Vengrijos, Estijos, Marienburgo ir kitų vietovių, patiekalai iš erelių buvo įtraukti į Anglijos diduomenės kulinarijos knygas (Mannermaa, 2003; Daróczi-Szabó, 2014; Lõugas et al., 2019; Pluskowski et al., 2009; Bartosiewicz, 2012). Tačiau Klaipėdoje buvo kapoti visiškai menkaverčiai mėsos požiūriu kaulai – pastaibis ir pirštakauliai, tad jų nebūtų galima sieti su erelių darinėjimu, mėsos ruošimu ar valgymu. Itin įdomu, kad vienas jūrinio erelio pastaibis yra su patologija – kaulas buvo arba lūžęs ir sugijęs, arba patyręs kitokio pobūdžio traumą (7 pav.). Plėšrūs paukščiai sulūžusiais kaulais gamtoje neišgyvena, tad paukštis turėjo būti laikomas nelaisvėje. Panašiai traumuoto jūrinio erelio skeleto dalis rasta Senojoje Ladogoje – manoma, kad paukštis taip pat laikytas nelaisvėje (Shaymuratova et al., 2019).

Mūsų atlikti tyrimai suteikė žinių apie paukščių naudojimo ypatumus XIII–XIV a. Klaipėdoje, jų metu buvo identifikuotos iki šiol Klaipėdoje nerastos laukinių paukščių rūšys – kurapka, jūrinis / kilnusis erelis, didysis kormoranas. Paukščių kaulų dalis tirtoje medžiagoje – 2,5 % – vertintina kaip nemaža ir būdinga elito gyvenamajai aplinkai. Be to, beveik visos aptiktos paukščių rūšys, tarp kurių gausu laukinių paukščių, yra sietinos su aukštesniojo socialinio sluoksnio mityba. Specifinė anatominė erelių kaulų sudėtis – vyraujantys apatiniai kojų kaulai – rodytų, kad nagai galėjo būti pagrindinis erelių eksploatacijos tikslas, nors negalima atmesti, kad ereliai medžioti kaip kenkėjai ir dėl plunksnų. Mažiausiai tikėtina, kad ereliai naudoti maistui ar auginti kaip medžiokliniai paukščiai. Neaišku, ar gausius erelių kaulus galima tiesiogiai sieti su Klaipėdos pilies elitu ir jo veiklomis. Šią teoriją palaikytų likusios zooarcheologinės medžiagos pobūdis – didesnė negu įprastai laukinių gyvūnų dalis ir didelė jų įvairovė, o tai yra būdinga diduomenės aplinkai. Vis dėlto reikėtų atlikti daugiau su elitu nesiejamų vietovių – kaimaviečių, miestų – zooarcheologinės medžiagos tyrimų, norint sužinoti, ar ereliai buvo naudojami ir kitų socialinių sluoksnių atstovų.

1 Cf. white-tailed sea-eagle. Identification confirmed by Teresa Tomek (Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Sciences) in 2016.