Ekonomika ISSN 1392-1258 eISSN 2424-6166

2020, vol. 99(1), pp. 50–68 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2020.1.3

Employment at 55+: Do We Want to work Longer in Lithuania?

Kristina Zitikytė

Department of Quantitative Methods and Modeling,

Faculty of Economics and Business Administration,

Vilnius University, Lithuania

Email: kristina.zitikyte@evaf.vu.lt

Abstract. The Lithuanian population is aging, and it causes many difficulties for public finances by increasing expenditures on health care, long-term care, and pensions, and also for the labor market by creating labor shortages. One of the ways to cope with demographic aging is to rise the employment rate of older people. According to Eurostat, the employment rate of the elderly aged 55–64 years increased from 49.6 percent in 2005 to 68.5 percent in 2018 in Lithuania and it is higher than the average employment rate of older workers in European Union, which was 58.7 percent in 2018. This paper focuses on older people in Lithuania, aged 55 and over, trying to answer a question whether the elderly in Lithuania willingly work or try to find alternatives such as receiving long-term social insurance benefits. The research findings show that the activity of older people in the labor market grows, and even the share of people with disabilities staying in the labor market increases. However, this analysis also shows that older people are more under risk to lose their job during an economic crisis, and this suggests that trying to find work alternatives can be closely related to one’s economic situation. Moreover, health problems remain one of the main factors limiting the activity of older people in the labor market. It is also noticeable that some labor force reserves exist among people with disabilities and this supposes that creating better adapted working conditions for older and disabled workers in Lithuania could probably contribute to meeting the needs of an aging workforce.

Keywords: older people, employment, elderly, early retirement benefit, disability pension

Received: 02/02/2020. Revised: 21/02/2020. Accepted: 02/03/2020

Copyright © 2020 Kristina Zitikytė. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

Mainly as a result of the aging process, older workers are becoming an increasingly important part of the European labor market. According to the Ageing Report (2018), the share of older workers (aged 55 to 64) on the employment (aged 20 to 64) at the European level is projected to rise from 16.8 percent in 2016 to 21.0 percent in 2030, and then to reverse to 20.4 percent in the long run.

Towards full employment. The European Union sees full employment as an important way of coping with the challenge of aging populations. A greater involvement of women, older workers and the better integration of migrants should help to increase the work force. As life expectancy improves, longer working lives “will be vital to enable men and women to acquire adequate pensions” (Pensions adequacy report, 2018). The idea of a “full employment” has been going on for many years in various important statements in one or another form.

In 2001, Stockholm Council defined an ambitious target: a rise in the employment rate of older workers (55–64) to 50 percent by 2010. Barcelona European Council (2002) supported the idea of full employment as the essential goal of economic and social policies, underlying that reforms of employment and labor market policies are needed. In 2003, Brussels European Council underlined the importance of discouraging early retirement incentives. The White Paper (2012) also recommended to restrict access to early retirement schemes and other early exit pathways, and support longer working lives by providing better access to life-long learning, adapting workplaces to a more diverse workforce, developing employment opportunities for older workers and supporting active and healthy aging. Pertaining to Europe’s strategy, the 2020 European Commission proposed that the employment rate of the population aged 20–64 should increase from the current 69 percent to at least 75 percent, including through a greater involvement of women, older workers, and the better integration of migrants in the workforce. According to Eurostat, the employment rate of the population aged 20–64 in the European union was 73.2 percent. and the employment rate of older workers aged 55–64 was 58.7 percent in 2018; therefore, it is moving towards the goals that were set earlier.

Employment of the elderly in Lithuania. In 2005, the employment rate of older workers aged 55–64 years was 49.6 percent, and it increased to 68.5 percent in 2018. The employment rate of the population aged 20–64 in Lithuania was 77.8 percent in 2018. There is not so much talk about the employment of older people in Lithuania, but one recent strategy can be mentioned that focused on the employment of older people. The strategy for demography, migration, and integration policy for 2018–2030 in Lithuania has highlighted three tasks: (1) to ensure older people’s participation in the labor market and their financial security; (2) to create a family-friendly environment, and (3) to ensure the management of migration flows that meet the needs of the state (Lietuvos respublikos seimas, 2018). The Strategy emphasizes that the poverty rate of older persons is still high in Lithuania. Moreover, it is emphasized that “the status of older people is aggravated by the short duration of their healthy lives and the lack of social and health care services for older people.” Because of the growing importance of older workers’ employment, the author of this paper sees firstly the need to better understand the extent of the alternatives of work people may choose in Lithuania.

The author aims to evaluate if Lithuanians willingly want to work longer or try to find some alternatives. Work alternatives in older age considered in this paper are receiving various social insurance benefits, for example, a disability pension or early retirement benefit. Also, the aim is to evaluate whether the institutional environment today in Lithuania does not create any incentive to leave labor market earlier. A statistical analysis of the data will allows to discover whether there are any visible negative signals that one or the other alternative is preferred.

The novelty of this research is that for first time the activities of the elderly are evaluated in a single study looking at this topic from the social insurance perspective, because this will help in composing a complete picture of the employment of older people in Lithuania. Moreover, this paper uses data not published anywhere before and long time series to understand the trends of choices of alternatives.

The results of the analysis imply that activity in the labor market grows among both older workers and people with disabilities in Lithuania. However, this analysis shows that older people are more at risk during an economic crisis, and they are the first one who must leave the labor market under those circumstances.

2. Literature review

The labor market situation of older has become very important in recent years. Increasing the labor force participation of the population aged 55–64 is critical for sustaining social-protection systems. The most common measure adopted to tackle with the pension sustainability challenge was raising pension ages with the expectation that this would ensure the higher employment rate by itself. Statistics shows that the employment rate of the elderly does increase in European Union countries, but many difficulties are still present because of the limited work opportunities for elders.

Negative employers’ attitudes to older workers still exist. Older workers may face a number of difficulties keeping their jobs because employers may have a belief that older workers may be less productive than younger ones, that they have been trained through a different educational system; they may be less mobile, less entrepreneurial, and generally less flexible; the quality of their human capital might be lower; and, even if they have acquired experience, it is often not useful in new, expanding sectors (Bussolo et al., 2015). On the other hand, there are employers who especially value the work ethic of older workers, appreciate low rates of absenteeism, and welcome older workers serving as mentors to younger workers (Cummins & McGrew, 2018).

Despite various points of view, the activity of older workers in the labor market tends to decrease with age. McNair et al. (2004) says that economic activity drops rapidly around the age of 60, but while the proportion of people still economically active between 60–65 falls to just over a third (35 percent), 17 percent of people between the state pension age and 69 are still economically active in Britain.

Changing technologies are becoming a challenge for older workers. Villosio et al. (2008) found that the introduction of new technology is biased against low-skilled workers, and while it appears to have improved job opportunities in some fields, it has resulted in job losses for older workers. Zientara (2009) interviewed entrepreneurs and employees from Polish enterprises and found out that despite recognizing the value of older employees and the need to accommodate them, most of the entrepreneurs perceive older workers as inflexible, IT-incompetent, and having difficulty learning new things.

Older people face age discrimination. Choi et al. (2018) found that age discrimination is a compelling factor in diminishing work enjoyment later in life: older workers who perceived a higher level of retirement pressure from colleagues and promotion preference for younger workers reported a lower level of work enjoyment. Desmette and Gaillard (2008) argued that self-categorization as an “older worker” is related to negative attitudes towards work (stronger desire to retire early, stronger inclination towards intergenerational competition), while the perception that the organization does not use age as a criterion for distinguishing between workers supports positive attitudes towards work.

Despite the difficulties in finding and maintaining a job, work makes older people’s lives healthier and happier. Choi et al. (2018), analyzing employees in U.S., found out that the level of work enjoyment among older workers on average was high, suggesting that older employees generally view working positively. Calvo (2006) found out that longer working lives will help most people maintain their overall well-being and working longer seems beneficial for most people.

On the one hand, health is very important for staying in the labor market. McNair et al. (2004) observes that people with formal qualifications are much more likely than the unqualified to stay later in work, and this is closely related to health. The unqualified workers are twice as likely to be long-term sick or disabled than those with any qualification, and by this reason they are more likely to leave the labor market earlier. On the other hand, staying in the labor market for longer allows one to feel needed for society, which has a positive impact on one’s well-being and health, too.

Older workers favor flexible working arrangements and highlight the importance of fair treatment. Institutional factors are very important in determining the transition from work to retirement (Eichhorst 2011, AARP 2014, Choi et al. 2018). AARP (2014) and Choi et al. (2018) find that older workers view the ideal job as one with flexible work arrangements, such as a flexible schedule, the opportunity to work part-time, and the ability to work from home. Bell and Rutherford (2013) also showed that many older workers would prefer to reduce their working hours.

McNair et al. (2004) also emphasized that part-time employment and other labor arrangements can play an important role in filling the gap between full-time employment and retirement and providing flexibility which allows older people to better combine their personal and health needs with working life. Plomp, de Breij & Deeg (2019) suggest that a higher variation in work activities and fewer repetitive movements at work might also lead to fewer older workers with health limitations exiting early from the workforce.

However, in many countries, older workers are still more likely to be made redundant (Meadows 2003), which can cause “involuntary” early retirement.

Early retirement – an attractive possibility to exit the labor market earlier. Early retirement was implemented in many European countries in the 1970s and 1980s as a policy to contain unemployment in a situation of weak economic growth, but since the late 1990s, a major policy reversed in European Union member countries, finding that member states should reduce incentives for early withdrawal from the labor force and raise the employment rate of older workers.

Researchers find strong interaction between early retirement policies and the discouragement of participation for older workers (Eichhorst 2011, Bassanini and Duval 2006, Staubli & Zweimuller, 2013). Echhorst (2011) argued that institutional settings that can provide pathways out of the labor market do not only concern specific early retirement schemes but also options to receive old-age pensions at an early stage such as disability pensions, extended unemployment benefits for older workers, long-term sickness benefits, and a number of other pathways to retirement such as old-age part-time work. Bassanini & Duval (2006) showed that the removal of early retirement incentives, a later statutory retirement age, as well as less generous unemployment benefits and lower income taxes lead to higher employment rates of older workers. Bell and Rutherford (2013) showed that those who want to work fewer hours are more likely to retire early, while those who want more hours delay their retirement compared with otherwise similar workers. Sewdas et al. (2018) confirmed in their study that a higher risk of voluntary early retirement was observed among those with a higher physical workload, lower job satisfaction, and a lack of job control.

Increasing the early retirement age can extend the employment rate of older people. Calvo (2006) says an increase in the early retirement age reduces the ability of people to voluntarily decide their labor force participation. Less control in the work and retirement decision could have an adverse impact on the well-being of older individuals. For example, Eichorst (2011) pointed out that Germany has successfully increased the employment of older workers in the last decade by using institutional factors, such as removing incentives to early retirement, activation strategies and enhanced training for older workers.

Staubli and Zweimuller (2013) showed in their paper that raising the early retirement age increased employment by 9.75 percentage points among affected men and by 11 percentage points among affected women. Analyzing increasement of early retirement age in Austria showed large spillover effects on the unemployment insurance program and disability insurance claims. Staubli and Zeimuller (2013) finished with the results finding that unemployment increased by 12.5 percentage points among men and by 11.8 percentage points among women. The employment response was largest among high-wage and healthy workers, while low-wage and less healthy workers either continued to retire early via disability benefits or bridged the gap to the early retirement age via unemployment benefits.

Another alternative is the disability pension. Disability in older people is a common problem and, in most cases, a chronic condition (Tas et al., 2011). Older workers in Europe with poor self-rated health are at risk of exit from paid employment, most notably through disability benefits followed by unemployment (Reeuwijk et al., 2017).The older people are, the bigger probability is to face bigger health problems and to lose part of capacity for work. But does it deprive them of access to the labor market?

People with disabilities are willing to work, but they desperately need special conditions. Older people with disabilities (aged 50–64 years) are more likely to have a part-time job compared with their non-disabled counterparts, and they use part-time employment as a means of achieving a much better balance between their personal and health needs and working life (especially those with depression and other mental problems) (Pagan, 2009). This suggests that policymakers must encourage part-time employment as a means of increasing employment opportunities for older workers with disabilities and support gradual retirement opportunities with flexible and reduced working hours (Pagan, 2009). Part-time employment provides flexibility to older disabled people, thus enabling them to remain in the labor market despite their health limitations.

Stricter conditions of receiving disability benefits can affect labor participation. Kantarci, van Sonsbeek & Zhang (2019) analyzed the new benefit regime which substantially decreased disability benefit receipts in 2006 in the Netherlands, and its impact had been persistent during the ten years of the study period because a stricter benefit regime of the reform limited the access to disability insurance substantially, and increased labor participation and unemployment benefit receipts to a limited extent.

Therefore, the literature review thus suggests that lower activity among older people may be influenced by health problems and difficulties older people face in labor market. However, researchers also note that alternatives such as early retirement or disability pensions can distract older people from the labor market, although sometimes they could be active there. In next section, hypotheses for the Lithuanian case will be formulated.

3. Hypotheses

The literature review allows the author to formulate some hypotheses in this section.

First, it is easy to predict that activity in the labor market declines with age, but a more detailed analysis is needed to find out at what age group activity drops sharply in Lithuania and how close that age is to retirement age. If activity in the labor market fades before reaching retirement age, knowing that retirement age will continue to increase to 65 in 2026, it would be evident that in Lithuania we have and will have problems in promoting the employment of older people. This would show that although we live longer, we are either unable to work longer or we do not want to do that. According to McNair et al. (2004), economic activity drops rapidly around the age of 60, and for this reason, the author of this paper ends up with a hypothesis saying that:

Hypothesis 1. Labor market activity is decreasing with age and drops rapidly around the age of 60 in Lithuania.

It is often heard that older workers find it more difficult to find a job and are more likely to be laid off. The data collected for this study do not include data on elders’ layoffs. But the fact of receiving unemployment insurance benefits may be considered an eloquent factor:

Hypothesis 2. The number of older unemployment benefit recipients is increasing due to the worse labor market position of older people.

To test this hypothesis, unemployment benefit recipients will be analyzed, because increasing the share of older unemployment benefit recipients could show that these people are leaving the labor market more intensively than the younger ones. On the other hand, the age structure of working people may change in the context of an aging population, and maybe this factor mostly affects the age structure of unemployment benefit recipients.

Previous paper of the author (Zitikytė, 2020) showed that health status is one of the most important factors affecting the choice to work in old age. Bridge employment was less likely with being more often sick. Individuals who were sick more, were 7 percent less likely to work than those who were sick less. Previous study included only cases of illness with certificates of incapacity, and those variables were significant, and it meant that health status is very closely related to bridge employment. Thus, when examining the employment of pre-retirement age people, it is appropriate to look at their health status and check whether their morbidity is different from that of other age groups. In context of previous work, the author ends up with a hypothesis saying that:

Hypothesis 3. Older workers are sick longer than the younger ones and it determines that health status is a very important factor limiting the employment of older people.

The paper will analyze diseases according to the number of cases where sick leave certificates are paid from the State Social Insurance Fund (SSIF).

In the face of even more serious health problems, some or all of a person’s working capacity is sometimes lost. In this case, people can receive disability pensions, thus compensating for the loss of work incapacity. On the one hand, facing disability can sometimes mean leaving the labor market at all and can in no way be linked to looking for work alternatives. These are cases where health problems require older people to leave the labor market. On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that in some cases people lose part of their capacity to work, but they do not return to the labor market, though it could simply be done by reducing working hours or choosing a job more suited to their new capabilities. The main idea here is to find out if, in the context of an aging population, the number of disability pension recipients grows, and it does not matter whether it means that health is deteriorating the rates of staying in the labor market for longer, or whether raising the retirement age discourages people to work longer and encourages them to look for some alternatives.

In this work, the author analyzes if people with disabilities in Lithuania enter the labor market, because being in the labor market is not only financially important but also due to the needs of socialization and the possibility of feeling needed in society. Nevertheless, the author ends up with a hypothesis saying that:

Hypothesis 4. The number of recipients of a disability pension is increasing in Lithuania and people with disabilities are not active in the labor market.

Researchers find a strong interaction between early retirement policies and the discouragement of older workers participation (Eichhorst 2011, Bassanini & Duval 2006, Staubli & Zweimuller, 2013). People in Lithuania can be entitled to early retirement benefits, too. Some detailed analysis is needed here because a growing number of people choosing early retirement benefits could be a serious signal that older people withdraw from the labor market whenever presented with such opportunity. In order to determine whether this assumption is correct in the case of Lithuania, the study ends up with a hypothesis saying that:

Hypothesis 5. In light of an aging population and increasing retirement age, more and more people are opting for early retirement in Lithuania. Moreover, this alternative is more popular among people who are in worse situations in the labor market, for example, when losing their jobs or earning relatively low income.

Perhaps in times of crisis more alternatives are being sought than in times of a growing economy. In a previous paper (Zitikytė, 2020) the author showed that activity in labor market among retirees is closely related to their economic situations. The share of working retirees decreased in 2009–2011, when economy was in crisis, and is increased in the period of 2012–2018. To sum up, the economic situation can be a crucial factor for older workers to realize them in the labor market. So, the last hypothesis is thus formulated:

Hypothesis 6. Older workers are more sensitive to economic downturns and they are more likely to look for alternatives in bad times.

To analyze the situation of older people in Lithuania and to test the hypotheses raised after the literature analysis, the next section uses graphical and statistical analysis.

4. The method and results

In order to test the hypotheses regarding the employment choices of older people, this paper conducted a thorough descriptive statistical analysis of the data without which it would be difficult to adopt more rigorous approaches. The aim of this research is to find out as much as possible from statistical data about older people’s activity in the labor market in order to lay the foundations for other studies. This baseline analysis allows for the first time in Lithuania to assess the disability pensions and early retirement benefits as alternatives of work for older people in the context of an aging population. The study also looks at how the employment of older people is influenced by their occupations and the sector which they work in.

The descriptive statistical analysis is enough in this case, since the data analyzed cover the entire population, not a sample. Therefore, descriptive statistical analysis is used to validate the hypotheses that allow us to highlight trends in Lithuania and further possible directions of research.

The structure of older people employment is analyzed simultaneously using the data of the Lithuanian Department of Statistics on the number of older people in Lithuania at the beginning of 2019 and checking the proportion of these people who receive one or another social insurance benefit. The data about people who work includes only employees, and self-employed people go into category called “others.”

The analysis is based as much as possible longer-time series, which allows for a detailed analysis of trends in the number of beneficiaries of social insurance benefits and the employment of older people. Moreover, in the part of the health situation of older workers in Lithuania data, diseases with paid sick leave certificates from SSIF are analyzed. Thus, it is important to emphasize that cases of diseases that are not covered by the SSIF are excluded.

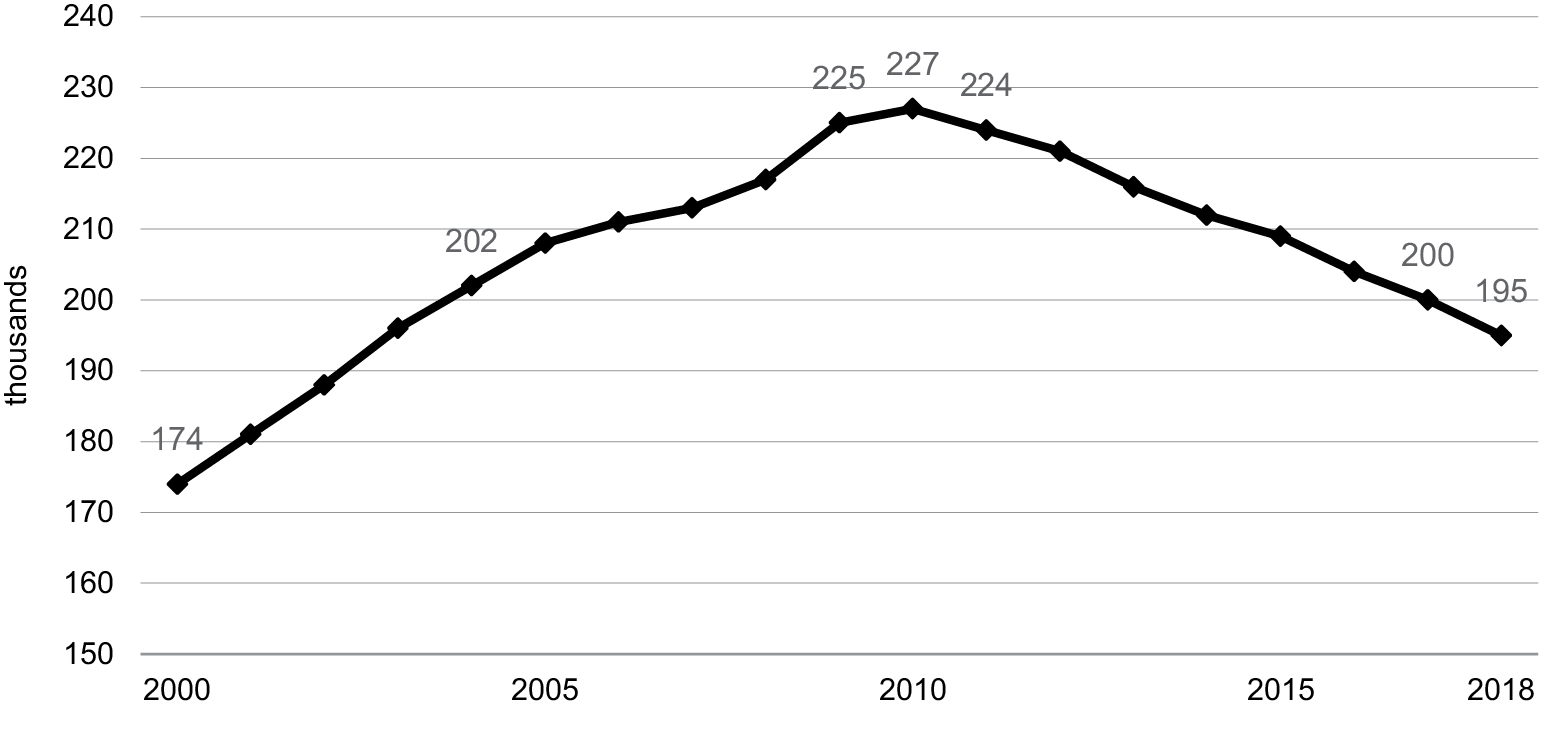

Older people are quite active in the market, but one in ten has a disability. Statistical analysis shows that the biggest share, 55 percent of people aged 55 and over, are already old-age pension recipients (FIGURE 1).

Fig. 1. Employment of older people aged 55+ in Lithuania at the beginning of 2019, in percent

Source: The Lithuanian Department of Statistics and SSIF, author’s calculation

Nineteen percent of elderly in Lithuania work, additional 7 percent work and receive old-age pension, and other additional 3 percent work and receive disability pension. It is evident that a significant number of people choose to contribute to pensions by working. The employment rate among old-age pension recipients in Lithuania increased from 9.2 percent in 2010 to 11.4 percent in 2018 (Zitikytė, 2020). To sum up, 29 percent of older people aged 55 and over in Lithuania work.

Second, ten percent of older people receive disability pensions and do not work. This large number surprises and suggests that the disability pension in Lithuania is one of the more viable alternatives to labor income among older people. About one percent of elders receive early retirement benefits. The rest 5 percent of elderly are neither recipients of social insurance benefits nor employees. For example, these people can be long-term unemployed or recipients of social assistance benefits, but this remains undefined within the framework of this study.

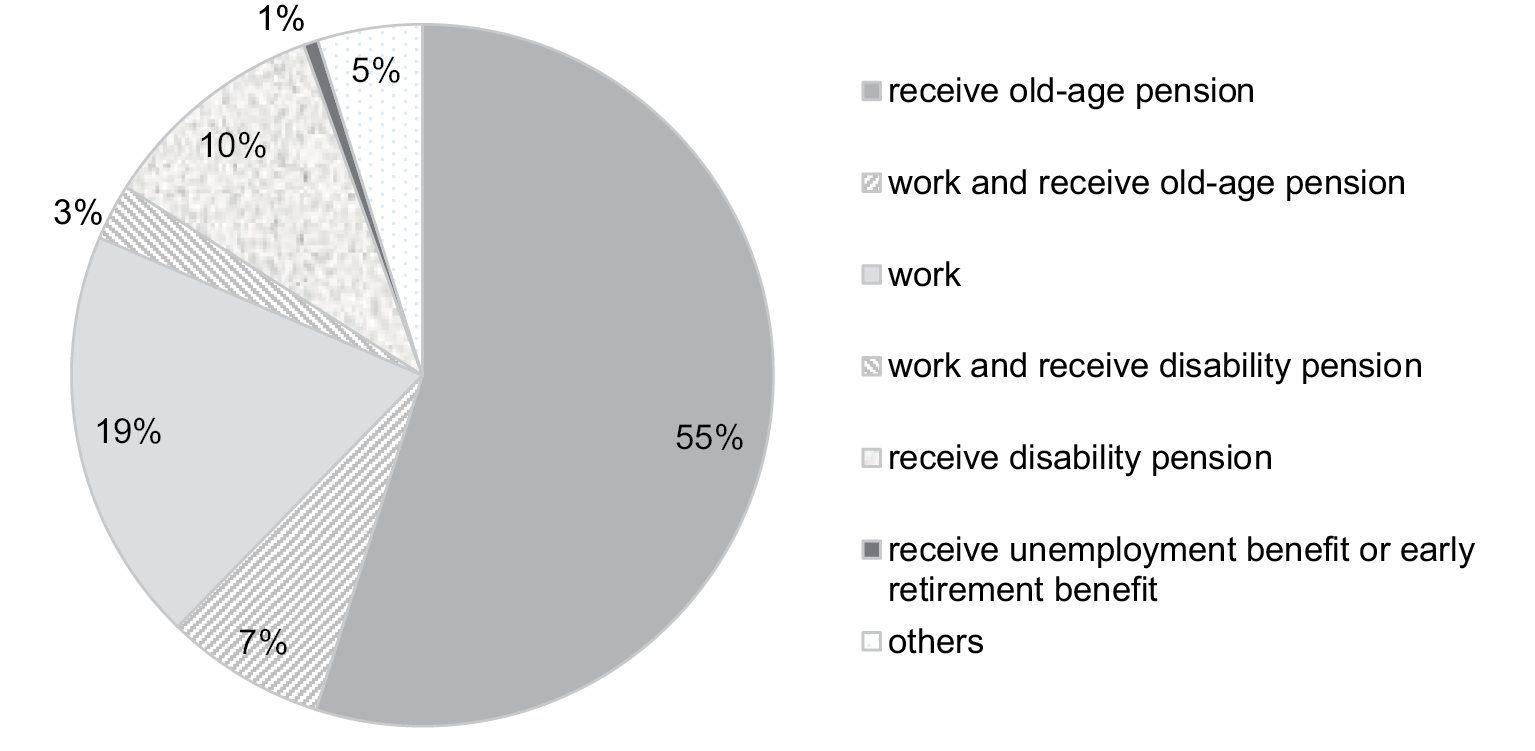

Activity in labor market is closely related to age. Labor activity increases until 35–44 years of life (FIGURE 2). The biggest activity is among people aged 35–44 years, which reaches 70 percent.

Fig. 2. Share of employees in total population (left) and average labor income of employees, January of 2019 (right)

Source: SSIF, The Lithuanian Department of Statistics and SSIF, author’s calculation

Since people reach 35–44 years, their activity starts to decrease and during the period of 55–64 years it reaches 57 percent. This supports Hypothesis 1 saying that labor market activity is decreasing with age and drops rapidly around the age of 60. Other 23 percent of people in 55–64 age group receive old-age or disability pensions. Not only the employment rate but also the amount of labor income depends on age. When the labor activity is the biggest, in ages 35–44, the average labor income is the highest. When a person reaches ages of 55–64 years old, their wages are 23 percent less than those received by 35–44-year-olds.

Employment opportunities can be determined by the choice of occupation and the sector which people work in. Data shows that the biggest share of older workers is employed in the public sector. Older workers aged 55+ take the share of 39 percent of all employees in the public sector, while in the private sector older employees, take the share of 26 percent of all employees. This shows that in Lithuania, the public sector is more friendly for older workers, and people see this sector as more attractive to work in old age.

Analyzing the employment of older people by occupation, the largest share of elderly is among (>45–50 percent of employees) unskilled workers, housekeepers, cleaners, and bus drivers. The smallest share of elderly is among (<5 percent of employees) waiters and various IT professions (application developers, IT employees, and communications services sales specialists). So, older people seem to regard working in new economic activities as a harder task.

Moreover, a significant proportion of older workers are among managers: one third of managers are older than 55 years. Most senior executives are (40–60 percent of employees) among municipal elders, childcare managers, education leaders, health service executives, and legislators. The least senior executives are among (20 percent of employees) advertising and public relations executives, managers in the field of information technology and communications services, human resources managers, heads of financial and insurance services. These facts show that for older workers it is easier to lead in fields where experience is more appreciated but in new fields where added value is growing rapidly, while where new knowledge and skills to work with changing technologies are needed, older workers feel not so comfortable. This poses major challenges for Lithuania, as with the aging of population and the rapid change in technology, people should be able to upgrade their skills, adapt faster to changing job requirements, and remain in demand in the labor market. However, a more detailed analysis will be needed to evaluate the impact of the technology and digital economy on older people (55+).

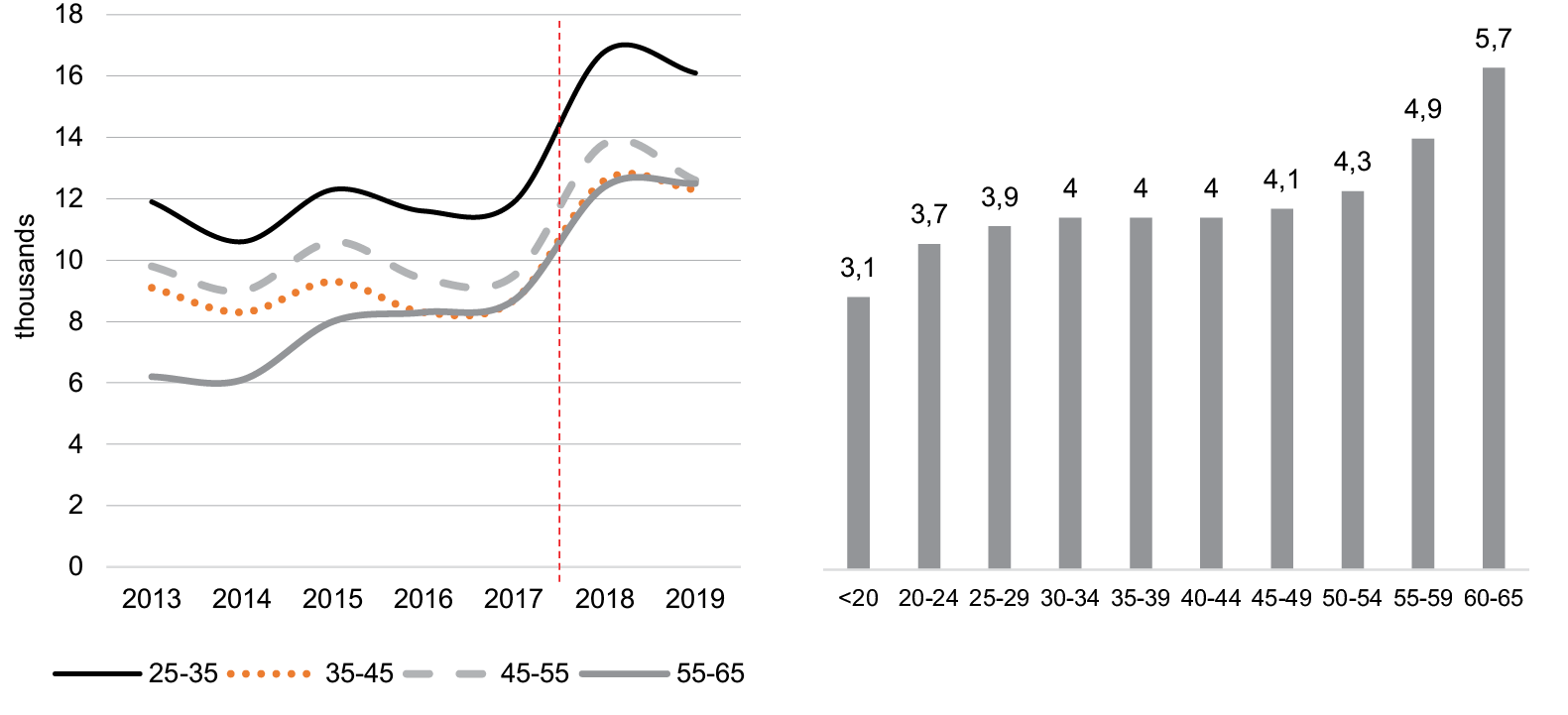

Facing unemployment in older age can be painful and it takes more time to overcome it than at a young age. During the last years the number of older unemployment benefit recipients grew most rapidly (FIGURE 3).

Fig. 3. Number of unemployment benefit recipients, in thousands (left) and average duration of unemployment benefit payment by age, in months (right)

Source: SSIF

In the overall structure, senior recipients increased from 17 percent in 2013 to 23 percent in 2019. All change can be explained by an aging population because in the structure of population, the share of older people aged 55–64 increased by the same 6 percentage points.1

Statistics of the average duration of unemployment benefit payment shows that older people seek employment opportunities longer than younger people. The average duration of an unemployment benefit payment is 4 months. Older people aged 55–59 receive unemployment benefits for almost 5 months, and people aged 60–65 years receive it for almost 6 months on average.

To sum up, the rise in the number of older people among the recipients of unemployment insurance benefits is more related to the aging population than to the greater incidence of unemployment among these people, which rejects Hypothesis 2 saying that the number of older unemployment benefit recipients is increasing due to the worse labor market position of older people. The data used in this study do not reveal such facts. However, it is noticeable that older people tend to receive unemployment insurance benefits for a longer period than the younger people, indicating that elders are in a more difficult position in the labor market.

One of the reasons why it is harder for people to work in older age are health problems. Older workers are more likely to receive longer-term sick pay (TABLE 1). Older people are more likely to suffer from diseases that have more serious consequences, such as lumbar and heart disease. Meanwhile, younger workers are more likely to be sick with shorter-term, seasonal illnesses, for example, flu or colds.

Moreover, the average duration of illness for employed persons aged 25–54 years is 11 working days, while the average duration of illness for employed persons aged 55–64 years is 18 working days. Longer periods of illness lead to more distraction and, in the long term, reduce the chances of staying in the labor market for longer.

Table 1. TOP 5 diseases with paid sick leave certificates from SSIF budget of 25–54 years old (left) and 55–64 years old (right), 2019, 1–9 months

|

No. |

Top 5 diseases 25–54 years old |

Average duration of one case (days) |

No. |

Top 5 diseases 55–64 years old |

Average duration of one case (days) |

|

1 |

Respiratory diseases, bronchitis |

5.2 |

1 |

Respiratory diseases, |

6.7 |

|

2 |

Acute tonsillitis |

5.0 |

2 |

Diseases of the lumbar and other intervertebral discs with radiculopathy |

26.0 |

|

3 |

Acute pharyngitis |

4.9 |

3 |

Lumbar and sacral nerve root disorders, not elsewhere classified |

16.3 |

|

4 |

Acute nasopharyngitis (colds) |

4.6 |

4 |

Flu with other respiratory |

6.3 |

|

5 |

Flu with other respiratory lesions |

5.5 |

5 |

Hypertensive heart disease without heart failure |

10.6 |

Source: SSIF, selected by number of cases of disease

To sum up, older workers are sick longer and they have more severe, chronic, and age-related diseases. Thus, as expected in the formulation of Hypothesis 3, health status is very important factor restricting the employment of older people.

Confrontation with disability is common among older people in Lithuania, which shows that some workforce reserves are located here. If people have bigger health problems, they can face work incapacity. Persons who have lost 45 percent or more of their capacity for work and have minimum seniority may be entitled to a disability pension.

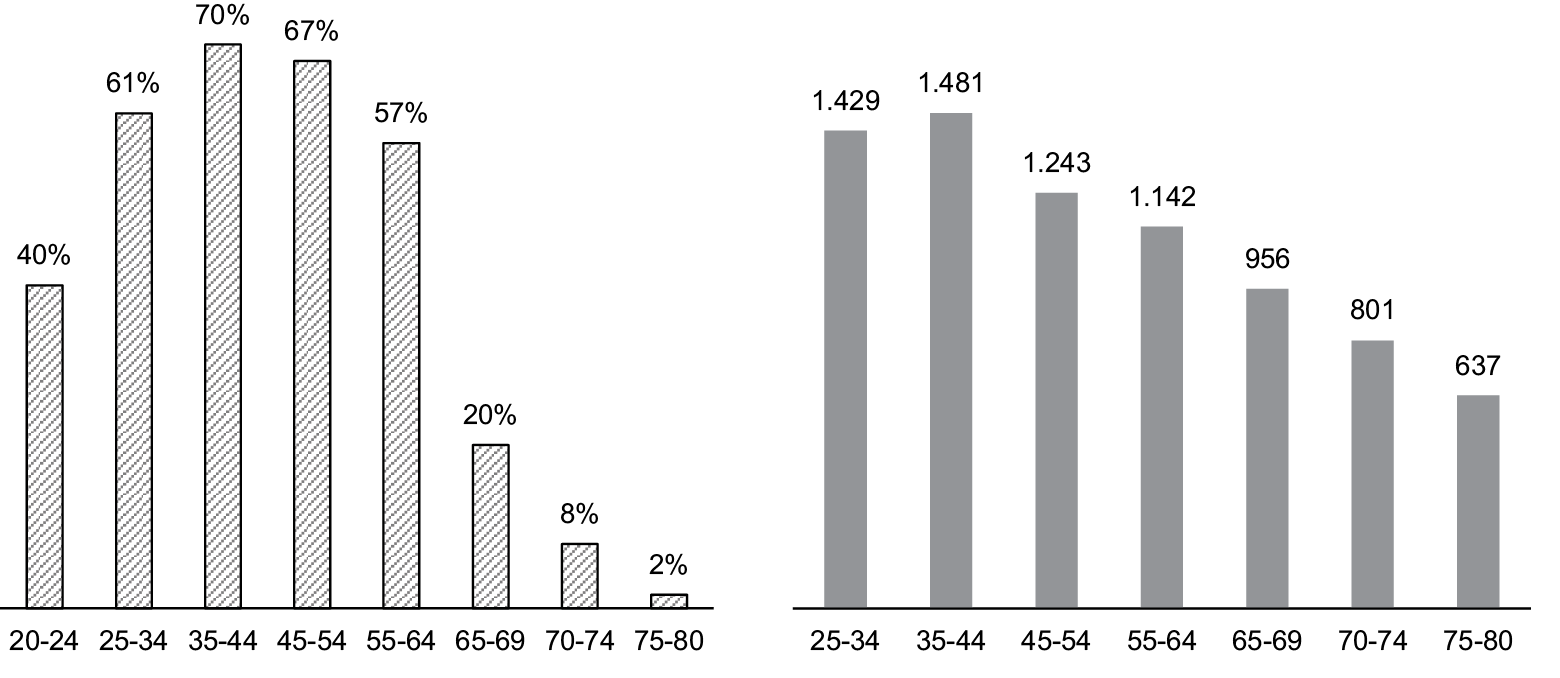

The number of people receiving disability pensions has increased since 2000 and reached the peak during the period of 2009–2010 (FIGURE 4). During the last 8 years, the number of these people decreases but still seeks about 195 thousand in Lithuania. This decrease can be affected by many reasons, including improving health, more strictly described disability determination procedures and economic growth.

Fig. 4. Recipients of disability pensions in 2000–2018, in thousands

Source: SSIF

The probability to face incapacity increases when people reach 55 years. Among all recipients of disability pensions, almost 68 percent are older than 55 years.

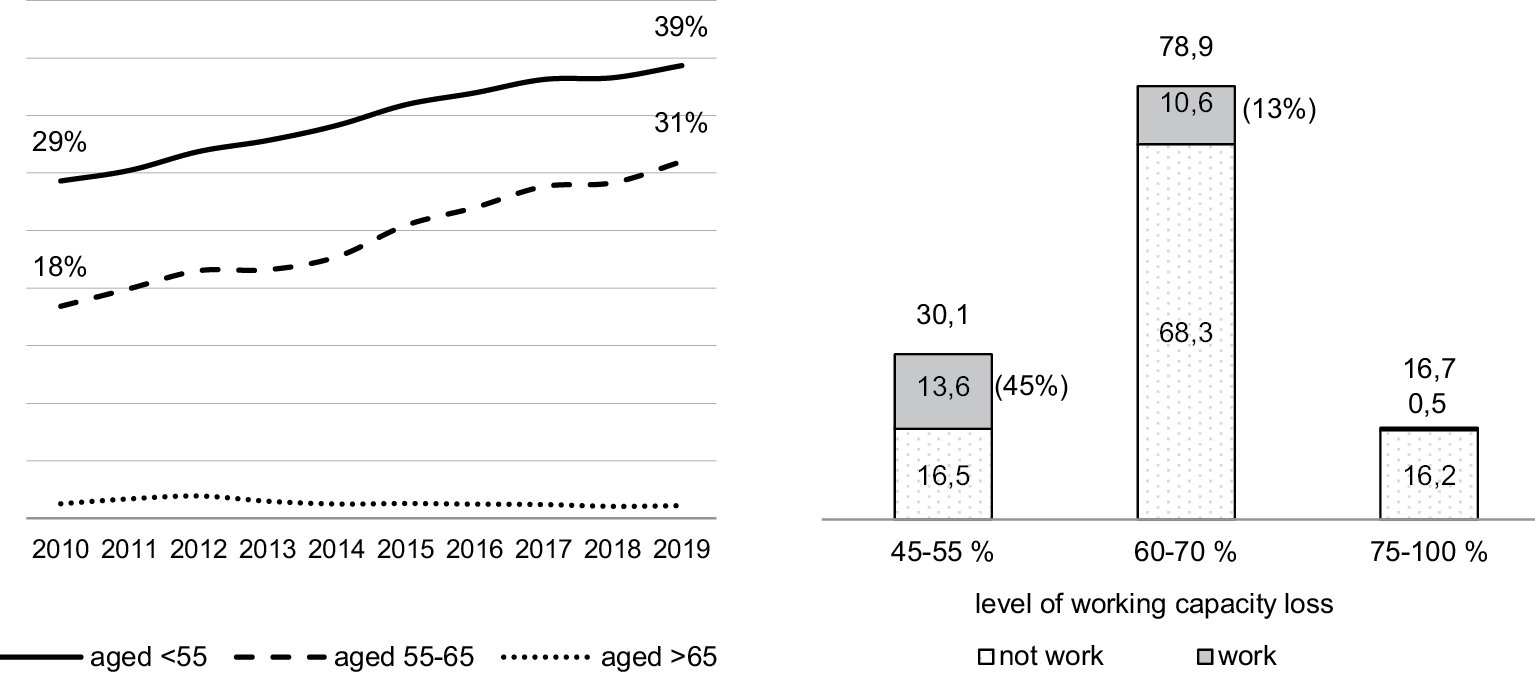

More and more people with disabilities stay in the labor market and work. One third of recipients of old age disability pension recipients work. Activity in the labor market among the elderly increased from 18 percent in 2010 to 31 percent in 2019 (FIGURE 5).

Of course, opportunities to work depend on the level of working capacity loss. Among older people who lost 45–55 percent working capacity, almost half still work – 45 percent. Among those who lost 60–70 percent, only 13 percent still work. Finally, almost all people who have lost most of their working capacity (75–100 percent) do not work.

Statistical data shows that disabled people in Lithuania earn 30 percent less than others (TABLE 2). Most disabled people work as cleaners and housekeepers. Their average income is 16 percent less than of others. Disabled workers working as corporate executives earn 30 percent less than other corporate executives. There is also a significant difference in labor income between accountants and nursing professionals, with disabled people earning 13–19 percent less than others.

Fig. 5. Working disability pension recipients in total number of disability pension recipients, in percent (left) and disability pension recipients 55+, in thousand (right)

Source: SSIF

Table 2. Top 10 occupations of disabled according to the number of employees

|

Occupation |

Difference in labor income compared |

|

Cleaners and housekeepers |

-16 % |

|

Shop sellers |

-12 % |

|

Unskilled workers |

-6 % |

|

Heavy truck drivers |

0 % |

|

Corporate executives |

-30% |

|

Nurses |

-13 % |

|

Security staff |

-16 % |

|

Accountants |

-19 % |

|

Primary and secondary school teachers |

-9 % |

|

Taxi drivers |

-16 % |

Source: SSIF

Disabled heavy truck drivers and unskilled workers earn almost as much as the rest of the workforce. The small differences in unskilled labor income are attributable to paying minimum wage to these people, not to productivity. These jobs are low-paid, so both disabled and non-disabled workers work for the same minimum monthly wage. The incomes of heavy truck drivers often do not reflect the real income because they get the big share of their labor income from non-taxable daily allowances. Data about daily allowances is not collected in official statistics. Thus, it is difficult to compare the labor income of heavy truck drivers, as their potential real labor income is probably much higher than that seen in official statistics. Therefore, it is possible that the labor income of disabled people in this area is lower as well.

Therefore, the number of recipients of a disability pension is decreasing in Lithuania and people with disabilities are more active in the labor market – this rejects Hypothesis 4. Although the income earned by disabled people from work is one third lower than others, the total income from the pension and wage (which is subject to a higher tax-free rate) is almost equal to the national average net income. For example, the labor income for all employed persons was 811 euros, and for disabled people, the total income (wage plus pension) was 795 euros in the end of 2019. Thus, the social security system compensates lost income and working disabled people may have income close to the average labor income of the country, but a large proportion of the disabled people do not work at all and their only source of income relies on disability pensions.

The scale of early retirement recipients in Lithuania is small, but those receiving these pensions choose this alternative because of the inability to stay in the labor market. In Lithuania, a person is eligible for early retirement pension if they are less than 5 years from retirement age, have an obligatory retirement record, have no other income, and do not receive any other pension or benefit.

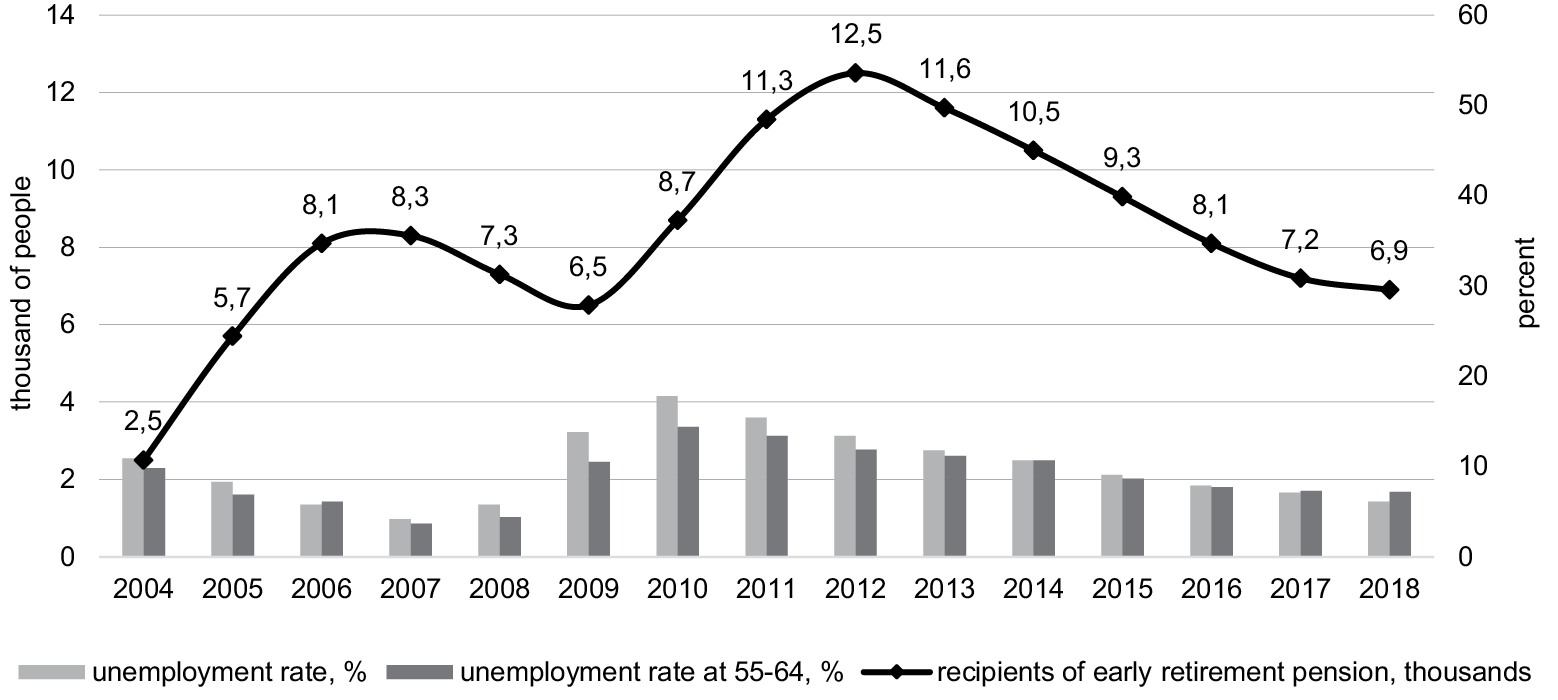

In Lithuania, about 7 thousand people each year take early old-age pension, and this represents about 1 percent of all retirees. The number of early retirement benefit recipients increased after the financial crisis from 6.5 thousand in 2009 to 12.5 thousand in 2012 (FIGURE 6). This supports Hypothesis 6 saying that the correlation between early retirement benefits recipients and economic cycle is strong.

Fig. 6. Recipients of early retirement benefits and unemployment rate

Source: SSIF

Half of early retirement benefit recipients receive pensions 5 years before retirement, another 21 percent decide to receive this pension 4 years before retirement; 56 percent of early-retirement benefits recipients a year before they have been entitled to benefit, do not have any labor income and 44 percent have had some income but very low. For example, in 2017 their labor income was 450 Eur, when the average labor income of all employees was about 730 Eur. Early retirement benefit recipients, before receiving this benefit, work as cleaners, housekeepers, shop sellers, or sweepers. The vast majority, 80 percent of all early-retirement benefit recipients, before receiving this pension, were employed in the private sector. This again demonstrates that the added value of the public sector is due to its demonstrated sensitivity to employees. In the private sector, however, other rules based on merit, results exist. This means that more older people are facing unemployment in the private sector, and this is also the reason for choosing to get early retirement when other sources of finance are lost.

The thought of taking an early retirement benefit can look as an attractive opportunity to get an early leave from work, but it is worth pointing out that such a pension is being reduced. The early retirement pension is decreased by 0.4 percent per each early retirement month. After reaching the standard retirement age, the reduction is recalculated according to the number of months for which an early pension was paid; therefore, receiving the early retirement pension decreases old-age benefit. In September of 2019, average early old-age pension was 250 Eur (one third less than the average old-age pension with the required record, which was 365 Eur).

5. Conclusions

The aim of this research was to evaluate if Lithuanians willingly want to work longer or try to find some alternatives. The results of the research show that labor market activity is decreasing with age and drops rapidly around the age of 60. These trends are closely related to literature where McNair et al. (2004) also referred to 60s as a time of declining labor market activity. This study reveals that poorer health with harder and longer-lasting job searches also contribute to this.

An analysis of the occupations of older workers has revealed that older workers are more likely to hold managerial positions in the public sector and in occupations where long-term experience is more valued. Meanwhile, fewer senior executives are emerging in new areas such as information technology, financial insurance, or advertising and marketing. This signals that older people are finding it harder to adapt to the changing labor market and new technologies and this will pose greater challenges in the face of rapid technological change in the future.

Although at first sight the share of older people in unemployment benefits is increasing, this is due to a change in the overall population structure as the population ages. It is true that older people look for a job longer than the younger ones. It cannot be ruled out in the framework of this study that perhaps some of these people are simply retiring and therefore withdrawing from the unemployment insurance benefit list.

Older workers are sick longer and they have more severe, chronic, and age-related illnesses and this often becomes a major barrier to staying in the labor market for longer. As the population ages, it will be difficult to achieve higher employment rates for older people if their health is not improved.

The number of recipients of a disability pension is decreasing in Lithuania and people with disabilities are more active in the labor market. Analysis has shown that people with lower incapacity for work adapt to the labor market and can work, but because of their lower productivity their income is on average about 30 percent lower than other workers. Today, the social security system compensates for the loss of working capacity, and working disabled people can raise their income by adding their efforts to bring them closer to the average income of the country.

Contrary to cases analyzed by other authors, Staubli and Zweimuller (2013) and Eichhorst (2011), Lithuania had no periods of very favorable and attractive incentives to early retirement, but a more difficult moment was captured during the crisis, when the number of these recipients had grown significantly. In times of recession and with the labor market primarily closing to older workers, elders are more likely than ever to seek alternatives. The results showed that people who choose to receive early retirement benefits have faced unemployment before or earned a relatively low income, which correlates with literature findings (Sewdas et al., 2018).

Also, this study highlighted a group of disability pension recipients as the subject of future research, because these people comprise a significant part of the older population and, according to literature analysis, these people are another source of the labor force that would be willing and able to be recruited if there were better opportunities to do it – as some authors highlight, for example, the possibility of a flexible schedule (Choi et al., 2018; Bell & Rutherford, 2013). The findings of this analysis can serve as a background for future research of evaluating the probabilities of leaving the labor market in different age groups. A survival analysis could help to evaluate at which age people with one or other features are more probable to leave the labor market in Lithuania.

References

AARP. (2014). Staying ahead of the curve 2013: The AARP work and career study.

Barcelona European Council 15-16 March 2002. Presidency conclusions. [EU European Council]

Bassanini, A., & Duval, R. (2006). Employment Patterns in OECD Countries: Reassessing the Role of Policies and Institutions. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 486. OECD Publishing (NJ1). Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1787/846627332717

Bell, D. N., & Rutherford, A. C. (2013). Older workers and working time. The journal of the economics of ageing, 1, 28-34. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2013.08.001

Brussels European council 20 and 21 March 2003 Presidency conclusions

Bussolo, M., Koettl, J., & Sinnott, E. (2015). Golden aging: Prospects for healthy, active, and prosperous aging in Europe and Central Asia. The World Bank. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0353-6

Calvo, E. (2006). Does working longer make people healthier and happier? Issue Brief WOB, 2. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2302705

Choi, E., Ospina, J., Steger, M. F., & Orsi, R. (2018). Understanding work enjoyment among older workers: The significance of flexible work options and age discrimination in the workplace. Journal of gerontological social work, 61(8), 867-886. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2018.1515140

Cummins, P., & McGrew, K. (2018). Employers and older workers: changing attitudes in a changing economy. Innovation in Aging, 2(Suppl 1), 320. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igy023.1170

Desmette, D., & Gaillard, M. (2008). When a “worker” becomes an “older worker” The effects of age-related social identity on attitudes towards retirement and work. Career Development International, 13(2), 168-185. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810860567

Eichhorst, W. (2011). The transition from work to retirement. IZA Discussion Paper. Retrieved from: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:iza:izadps:dp5490

European Commission (2012) White Paper. An agenda for Adequate, Safe and Sustainable pensions. COM (2012) 55 final, 16 February 2012, Brussels. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258912452236

European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth: Communication from the commission. Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurostat. (2018). Eurostat database.

Kantarci, T., van Sonsbeek, J. M., & Zhang, Y. (2019). The impact of the disability insurance reform on work resumption and benefit substitution in the Netherlands. Retrieved from: https://www.netspar.nl/en/publication/dutch-employers-responses-to-an-aging-workforce/

Lietuvos respublikos seimas (2018). Dėl demografijos, migracijos ir integracijos politikos 2018-2030 metų strategijos patvirtinimo, 2018 m. rugsėjo 20 d. Nr. XIII-1484. Retrieved from: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/fbb35e02c21811e883c7a8f929bfc500?jfwid=-35aaxldoi

McNair S, Flynn M., Owen L., Humphreys C., Woodfield S. (2004). Changing work in later life: a study of job transitions. Centre for Research into the Older Workforce, University of Surrey. Retrieved from: http://eprints.kingston.ac.uk/id/eprint/19759

Meadows, P. Retirement ages in the UK: a review of the literature. Employment Relations Research Series No. 18. London: Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform, 2003. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237212832

Nerlich, C. (2018). The 2018 Ageing Report: population ageing poses tough fiscal challenges. Economic Bulletin Boxes, 4. doi: https://doi.org/10.2765/615631

Pagán, R., & Malo, M. Á. (2009). Job satisfaction and disability: lower expectations about jobs or a matter of health? Spanish Economic Review, 11(1), 51-74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10108-008-9043-9

Plomp, N., de Breij, S., & Deeg, D. (2019). Personal and work-related predictors of early exit from paid work among older workers with health limitations. Retrieved from: https://www.netspar.nl/en/publication/hr-policy-plays-important-role-in-preventing-early-exit-of-elderly-employees-with-health-problems/

Reeuwijk, K. G., van Klaveren, D., van Rijn, R. M., Burdorf, A., & Robroek, S. J. (2017). The influence of poor health on competing exit routes from paid employment among older workers in 11 European countries. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 24-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10108-008-9043-9 10.5271/sjweh.3601

Sewdas, R., van der Beek, A. J., de Wind, A., van der Zwaan, L. G., & Boot, C. R. (2018). Determinants of working until retirement compared to a transition to early retirement among older workers with and without chronic diseases: results from a Dutch prospective cohort study. Scandinavian journal of public health, 46(3), 400-408. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817735223

Staubli, S., & Zweimüller, J. (2013). Does raising the early retirement age increase employment of older workers? Journal of public economics, 108, 17-32. Retrieved from: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/5863/does-raising-the-retirement-age-increase-employment-of-older-workers

Stockholm European Council 23-24 March 2001. Presidency conclusions and annexes. [EU European Council].

Taş, Ü., Steyerberg, E. W., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M., Hofman, A., Koes, B. W., & Verhagen, A. P. (2011). Age, gender and disability predict future disability in older people: the Rotterdam Study. BMC geriatrics, 11(1), 22. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-11-22

The 2018 pension adequacy report (2018). Current and future income adequacy in old age in the EU. Volume I. doi: https://doi.org/10.2767/406275

Villosio, C., Di Pierro, D., Giordanengo, A., Pasqua, P., & Richiardi, M. (2008). Working conditions of an aging workforce. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. ISBN 978-92-897-0815-9

Zientara, P. (2009). Employment of older workers in Polish SMEs: employer attitudes and perceptions, employee motivations and expectations. Human Resource Development International, 12(2), 135-153. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860902764068

Zitikytė, K. (2020) “To Work or not to Work: Factors Affecting Bridge Employment Beyond Retirement, Case of Lithuania”, Ekonomika, 98(2), pp. 33-54. doi: https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2019.2.3.

1 The number of recipients of unemployment benefits for all age groups has increased since 2017 due to the change in the legal basis for receiving these benefits (reduction in length of seniority requirement, lengthening of the payment period).