Ekonomika ISSN 1392-1258 eISSN 2424-6166

2021, vol. 100(2), pp. 171–189 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2021.100.2.8

About the Calculation of the Compliance Value and its Practical Relevance

Hans-Ulrich Westhausen

ANWR GROUP eG, Germany

Email: hans-ulrich.westhausen@anwr-group.com

Abstract. Corporate investment in compliance in general and compliance management systems (CMS) in particular, follow the cardinal management obligation to always obey the law (so-called “management duty to legality”). But does the compliance function as any other corporate investment really add value favoring all shareholders? The socially desired answer should be probably “yes”, but the business reality shows a different picture: the measurement of the compliance value is a “blind spot” in the scientific theory and research as well as in the corporate practice. This paper analyzes reasons for that “blind spot” and explores the systematization of the compliance value drivers setting up a practical model that monetarizes these effects as well as calculating the added value and ROI of compliance. The author concludes that this quantification is particularly relevant to practice, as the compliance function must be able to measure the quantified impact(s) of the compliance function in order to demonstrate its value to management, shareholders, as well as all interested parties, and to justify and strengthen its role increasing the effectiveness of the CMS as part of the company’s “second line of defense”.

Keywords: Compliance Management System, added value, ISO 37301, Three lines of defense

_________

Received: 19/07/2021. Revised: 11/10/2021. Accepted: 03/11/2021

Copyright © 2021 Hans-Ulrich Westhausen. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

Corporations of all types, sizes, branches throughout the entire world are facing the same ambiguous monster called ‘compliance’. One side of this monster is its true belief that all problems can be solved with rules and laws. Therefore, it creates more and more rules and laws and changes them increasingly often. The other side is that the worldwide ‘regulating flood’ is enormous. It creates not only more complexity in the legislative corpus, but also soaring compliance costs for corporations.

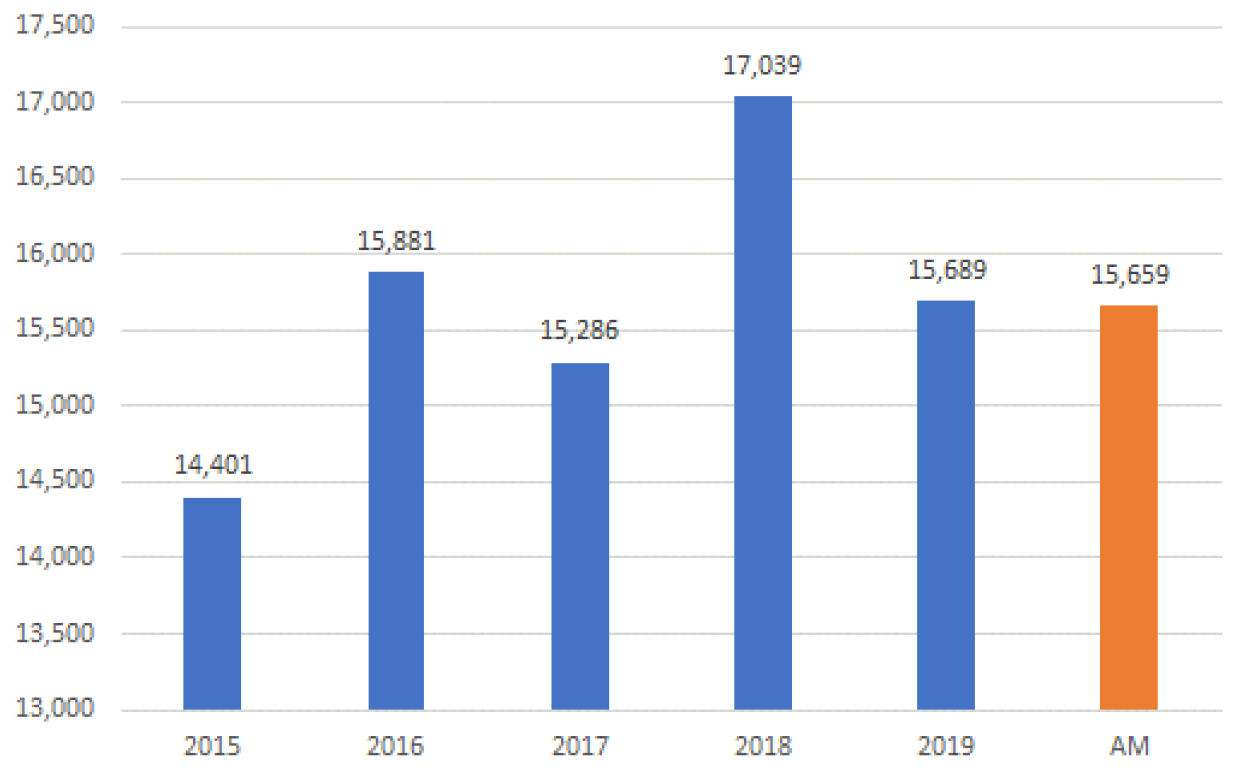

Calculations for 2019 resulted in a worldwide volume of 56,624 statutory changes, i.e., 217 legislative alterations on average per each single working day (Hammond and Cowan 2020). Furthermore, the ‘regulating flood’ within the EU is gigantic, too. On average 15,659 legally binding documents are released year by year continuously enlarging the overweight of the ‘compliance monster’ (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of legal documents (European Union).

Source: EUR-Lex (Oct 7, 2021)

At the national level, the ‘compliance monster’ follows the international trend. Currently, in Germany, there exist up to 27,461 different national legislative rules for corporations (Statistisches Bundesamt 2021) as well as municipal and local rules, regulatory and industrial specifications, voluntary obligations, declarations of intent and codes (the ‘soft law’) and, finally, internal rules within the corporations such as guidelines, working instructions or ‘codes of conduct’ that all are to be included in the ‘compliance inventory’. Corporations cannot casually face such a ‘compliance monster’, but need a multilevel and systematic approach, or, in other words, a company-specific CMS, based on recognized implementation standards (e.g., ISO-Norm 37301:2021 Compliance management systems) and regular tests for its effectiveness.

As soon as the significant implementation costs become visible, the management often gets more and more reserved about the further development of the new CMS. “Do we really need more staff for compliance?” or “Why can’t we simply distribute some relevant intranet news to all employees instead of conducting time-consuming compliance trainings?” are typical questions by the management then. If the compliance officer is unable to argue adequately at this point, the further introduction of the CMS will come under heavy pressure. It even runs the risk of being implemented only incompletely, so that the CMS under development could ultimately be less effective or not effective at all. The most important ‘point of attack’ is the insufficiently explained or even completely missing value aspect of compliance. This ‘argumentative gap’ extends not only to the corporate world, but also to academia. The measurement of the added value of compliance is still a ‘blind spot’ that needs to be explored. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to work out the value of compliance, to monetarize the value as far as possible, and to develop a generic ROI calculation model for this purpose.

2. Research method

The research method for this paper is divided into two parts: on the one hand, the current state of research on the calculation of compliance added value had to be identified, and, on the other hand, calculation models and statistical approaches that could possibly be used for the comparison of costs and benefits of compliance measures and the ROI calculation of compliance were of interest.

The systematic literature search (refer to Chapter 3) was subsequently used to obtain a detailed overview of calculation approaches for compliance costs and benefits within a reasonable timeframe. In systematic literature search, library catalogs and databases are searched for keywords, and the sources found are then analyzed further. In the present research, the search string value of compliance was pursued in the freely accessible web-based scientific database Google Scholar.

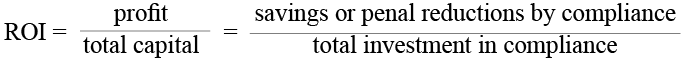

The generic calculation model of compliance added value was developed in two stages as follows: at first, compliance values could be calculated as shown in Figure 2. Afterwards, i.e., in the permanent evaluation and comparison of successive evaluation periods, the statistical tool of time series analysis could then be used.

Figure 2. Generic model to calculate the compliance value.

Source: Westhausen 2021

As a possible calculation method of different compliance values, especially within the early development steps of the CMS, the ‘ex ante/ex post’ added value comparison calculation came into focus. This involves determining and comparing the measurable effects on expenses and earnings before and after the introduction of compliance measures. Higher returns from compliance measures than their corresponding costs would then indicate a verifiable monetarized added value of compliance in a time series comparison. In order to analyze an already implemented CMS in the longer term for value creation, the statistical instrument of time series analysis – both retrospectively and in the direction of the future (trend extrapolation) – would be suitable.

3. Literature and research review

Scientific literature sources, as well as academic research projects about corporate compliance subjects such as relevant KPIs, costs and effects, value addition or ROI of compliance are rather uncommon. Therefore, one can also speak of a ‘blind spot’ or a research gap here. Some arguments are as follows:

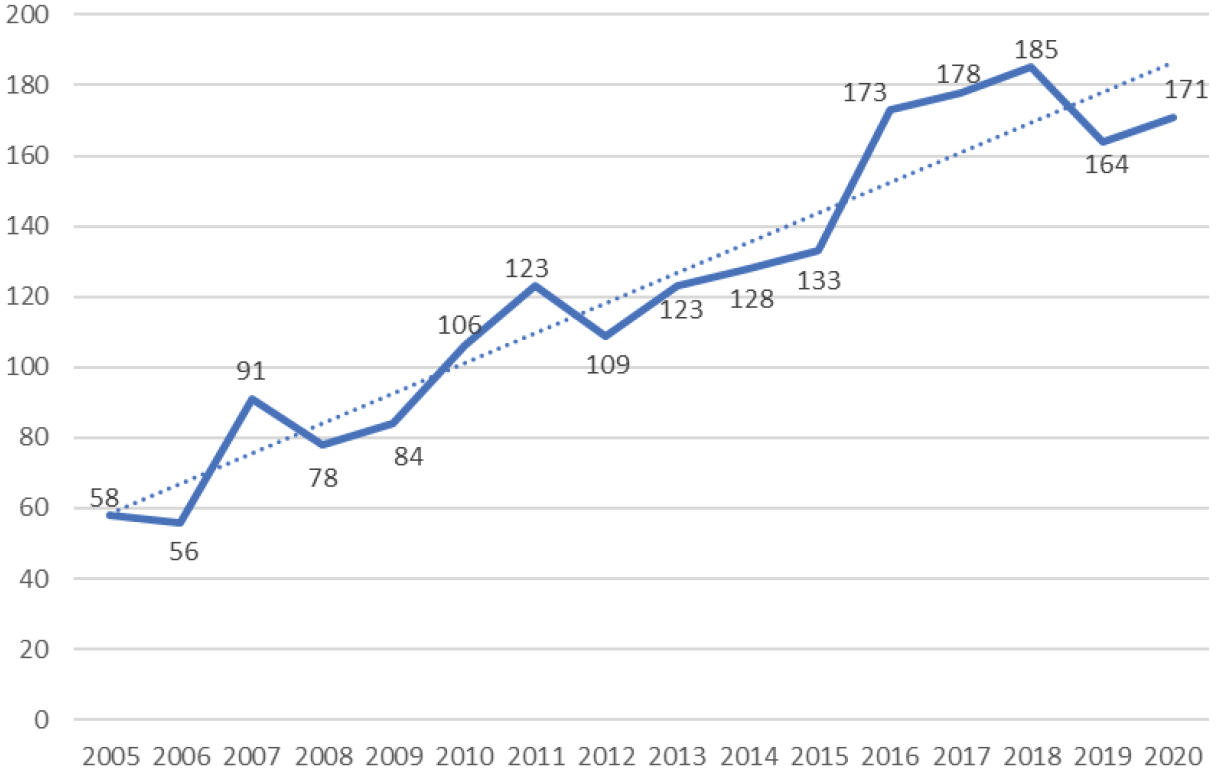

Firstly, the search for the keyword string ‘value of compliance’ in Google Scholar leads indeed to an increasing trend of scientific entries, but still at a low level of relevant hits (refer to Figure 3), especially because an estimated 60–70% of the sources had to be deducted from the total number due to their irrelevant connotation, e.g., as ‘medical compliance’ instead of corporate compliance.

Figure 3. Number of keyword hits for ‘value of compliance’.

Source: Google Scholar (Oct 7, 2021)

Secondly, beyond the limited sources identified in Google Scholar, the Overview of relevant literature (refer to Appendix 1) encompasses only 15 English and German sources (i.e., monographs, research studies, articles) that are related to the value of corporate compliance, but just one source is based on a quantified approach to measure costs, effects, and ROI of compliance (Hastenrath and Diem 2020), and only one other source is from 2021 (Giard and Leblanc).

Thirdly, the Competence Center Risk and Compliance Management of Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts (Switzerland) could be found as the one and only scientific institution currently exploring the value of compliance. The research project Return on Compliance, sponsored by the Swiss agency for innovation Innosuisse and guided by Mirjam Durrer and Stefan Hunziker, has been running since November 2020 and will continue over about 2.5 years until July 2023. Apart from the study on the effectiveness aspects of compliance, the main goal of the project is to bring corporations in the position to “quantify the value of compliance, so that compliance will not be understood as a cost factor anymore, but as added value, e.g., for the enhancement of the competitiveness” (Durrer and Hunziker 2021).

Fourthly, standard setting and opinion leading literature for the development of corporate compliance does not focus on the quantification of compliance effects. For example, the completely revised third edition of the Handbook Compliance-Management containing 1,405 pages does not include terms like value, added value, gain, KPI, ROI of compliance in the index (Wieland et al. 2020).

4. Corporate compliance is relevant, but the value of compliance is vague

The former Deputy Attorney General of the US Paul McNulty put it in a nutshell when he once said: “If you think compliance is expensive, try non-compliance” (YouAttest 2020). It seems that the corporate world has agreed to that statement as empirical data from Germany show (PWC 2018):

• 97% of all large-scale corporations with more than 10,000 employees had already implemented a CMS.

• 75% of all mid-sized corporations with more than 500 employees were already using an integrated CMS at that time.

• 10% had already planned the setup of a CMS.

Compliance is neither a ‘paper tiger’ nor practiced as an end in itself. The relevance of the compliance function is based upon its value for the corporate governance and business success of any corporation. Three selected arguments for compliance are as follows:

Firstly, following the organizational theory, the compliance function is – aside from risk management and controlling – one part within the second defense line of the world’s widely-favored corporate governance model of the ‘Three lines of defense’ (Westhausen 2016).

Secondly, compliance helps corporations to avoid enormous monetary fines for non-compliance, e.g., Airbus 2020 for corruption 3.6bn Euro (Deutsche Welle 2020) or Google 2018 for the abuse of its market power 4.3bn Euro (SZ.de 2018).

Thirdly, already released verdicts, e.g., in Germany since 2013 (refer to the verdict LG Munich I 2013 no. 5HK O 1387/10) and new legislative initiatives (e.g., in Germany the upcoming criminal law against organizations or Verbandssanktionengesetz) all point in the same direction: good compliance and an effective CMS can have significant positive effects for management and corporations: either disclaiming liability (i.e., partial or even complete reduction of liability) or at least mitigating (i.e., fine reducing).

But with the acceptance rates for corporate compliance in conjunction with the implementation rates of CMS nowadays reaching presumably 80–100%, depending on the company size, how can the value of compliance seem to be vague and a ‘blind spot’ in the corporate and academic world? Reasons for that can be manifold (refer to Chapters 4.1–4.5).

4.1. Ambivalent correlation between compliance and corporate value

Whether there is an added value of compliance or not, this is scientifically not yet conclusively proven. There is research underlining a positive correlation between good compliance and a better performance of corporations. The positive effects of compliance build a whole ‘positive cluster’ consisting of more transparency, increased trust and less risk for investors, better reputation of the corporation and therefore lower capital costs, higher ROI and higher market valuation (Aluchna and Kuszewski 2020), e.g., with regard to the total cost of acquisition and the target price in an M&A process (Giard and Leblanc 2021). The better is the CMS, the higher is the takeover price of an M&A acquisition. On the other hand, compliance can also lead to a neutral or even negative corporate value caused by intransparency in the declared fulfillment of corporate governance codes, concentrated ownership with insufficient protection of all investors (especially minority shareholders), emerging governance, principal-principal-conflicts and in the resulting reduced trust and higher risk for investors (Aluchna and Kuszewski 2020).

4.2. Non-existence of calculation standards for the value of compliance

Neither worldwide applicable norms for the standardization of management systems like the guidance norm ISO 19600:2014 nor the certifiable norm ISO 37301:2021 or other standard setting norms like the management standard of statutory auditors, e.g., the auditing standard IDW PS 980 of German statutory auditors include ideas regarding the measuring of costs of compliance or the calculation of effects, added value or the ROI resulting from single compliance activities or the CMS in total. Therefore, nobody can be surprised about the ‘blind spot’ value of compliance, if there are no standards given about how to identify and measure it.

4.3. Fading-out the human factor

Recent fraud cases, e.g., the Wirecard-fraud case, highlighted two behavioral aspects of compliance. Firstly, there is no ‘absolute compliance’. Even the best compliance program in the world could probably not have prevented several fraudulent managers of the German Wirecard AG from collusively embezzling 1.9bn Euro (McCrum and Storbeck 2020). Just because a corporation has a great compliance program does not mean people are not going to behave unethically. By the way, the CMS of Wirecard (Wirecard 2019) was good, including all ‘standard-elements’ of an ideal and effective CMS including organizational elements like a Chief Compliance Counsel, a Group Compliance Office, a Governance Risk & Compliance Committee (GRC) and cultural elements as the “Wirecard Code of Conduct” and an appropriate “tone from the top”. Secondly, all corporate personnel, beginning from the highly paid top management down to the modestly paid worker, need to understand the justification of compliance measures (e.g., reasons and value in a transparent, quantified structure). This requires a plausible and understandable argumentation line aligned for all levels of corporate hierarchy. Without understanding the sense of a compliance measure, one will probably not follow it. Managers will then only halfheartedly commit themselves to their compliance responsibility, just following the German proverb “What the farmer doesn’t know he doesn’t eat” (“Was der Bauer nicht kennt, frisst er nicht”).

4.4. Weak argumentative power of compliance staff

The top five qualifications compliance manager needs to have are the following (DGQ 2017): know-how in business economics, legal knowledge, leading and argumentative ability, communicative competence, and flexibility. Among all five qualifications, the argumentative and communicative skills are of special relevance for the success of compliance, because people need to be convinced of the sense and usefulness of compliance measures if they have to execute them. Unfortunately, the current personal profile of compliance staff seems to have an argumentative-communicative weakness. This conclusion results from a current survey in which about 70% of 370 top managers believed the compliance function was not sufficiently able to persuasively demonstrate the ROI of the compliance budget (Fechner und Baier 2020). Just as critical was a finding in another empiric study: Most compliance managers (71%; n: 574) saw themselves as “skillfully equal to the challenges of compliance” (Grundei et al. 2017). Doesn’t this overconfidence of compliance managers in their argumentative and communicative skills need to be questioned and changed?

4.5. Research gap

The gap already pointed out in the research of the value-addition of compliance is in itself a reason why the corporate world is less concerned with the quantification of compliance value and is still reluctant to address this topic.

5. Costs, returns, and added value of compliance

The general concept of the added value consists of the comparison of costs and returns of an investment with the result of a positive difference (i.e., added value) or a negative difference (i.e., loss). In the following, the concept of the added value is applied to the investment in compliance.

5.1. Costs of compliance

Usually, compliance costs are categorized into ‘one-off costs’ and ‘ongoing costs’ as follows (Westhausen 2021):

• one-off: all costs for the initial implementation of the CMS (e.g., project planning, consulting, IT-systems, recruiting costs for a compliance officer and if necessary for further compliance staff as well as their entrance training, installation of a whistleblowing-system), and

• ongoing: all costs of the ongoing operations (e.g., running personnel costs, compliance training for the entire workforce either in presence or online, internal realization costs of compliance requirements at process-related and functional level, running IT-costs, internal and external suitability and effectiveness audits of the CMS), lost sales due to compliance restrictions.

Following a survey of 173 German medium-sized corporations, each organization currently spends about 37,300 Euro p.a. to secure compliance (Becker et al. 2011; the calculation of the author is based on the total consumer price inflation of 13.6% between 2011–2021). Compliance budgets in large-scale enterprises and especially within the financial and insurance sector easily reach a double-digit million Euro-scope or even more in the long run. According to a 2017 survey of 141 banks and insurance companies in the European Union, about 2–4% of their ‘total operating costs’ were invested in compliance (one-off and ongoing): in absolute figures, banks invested 4.2m Euro (median) and 98.4m Euro (mean), whereas insurance companies invested 2.0m Euro (median) and 49.9m Euro (mean) (European Commission 2019).

5.2. Returns of compliance

The returns of compliance are subject to a known, but still unsolved, measurement dilemma. On the one hand, the multiple positive effects related to compliance are more or less undisputed in the corporate world, but, on the other hand, because of the difficulty in measuring these effects, an even bigger problem comes along. Due to the limited quantification of the compliance returns, the legitimization of the considerable compliance costs in front of the top management gets very challenging (Hastenrath and Diem 2020). Compliance returns, whether qualitative or partly quantitative, should become totally quantified and monetarized to have a comparable, transparent calculation methodology that convinces the management factually and not only by mellifluous, warm words. The systematic aggregation of compliance returns, categorized in effects of key performance indicators (KPI’s) and gains of compliance, is developed below (refer to Chapter 6).

5.3. Added value of compliance

There is no single definition or concept of an ‘added value’ of an activity, but a diffuse mixture of approaches, including the political surplus theory of Karl Marx, the fiscal concept of the taxation of each added value either at the production, trading, or services level (named VAT), or the difference between the output and the corresponding input of a process or a process step (Reineke and Bock 2007). Regarding the added value of compliance, the confrontation of compliance costs or ‘compliance input’ (5.1) and the quantified compliance returns or ‘compliance output’ (5.2) will lead to either positive or negative difference. Therefore, the added value of compliance could be defined as follows (Westhausen 2021):

The added value of compliance is the surplus over an investment in compliance resulting in a positive difference between in- and outbound cashflows representing the success of the compliance activity at the same time.

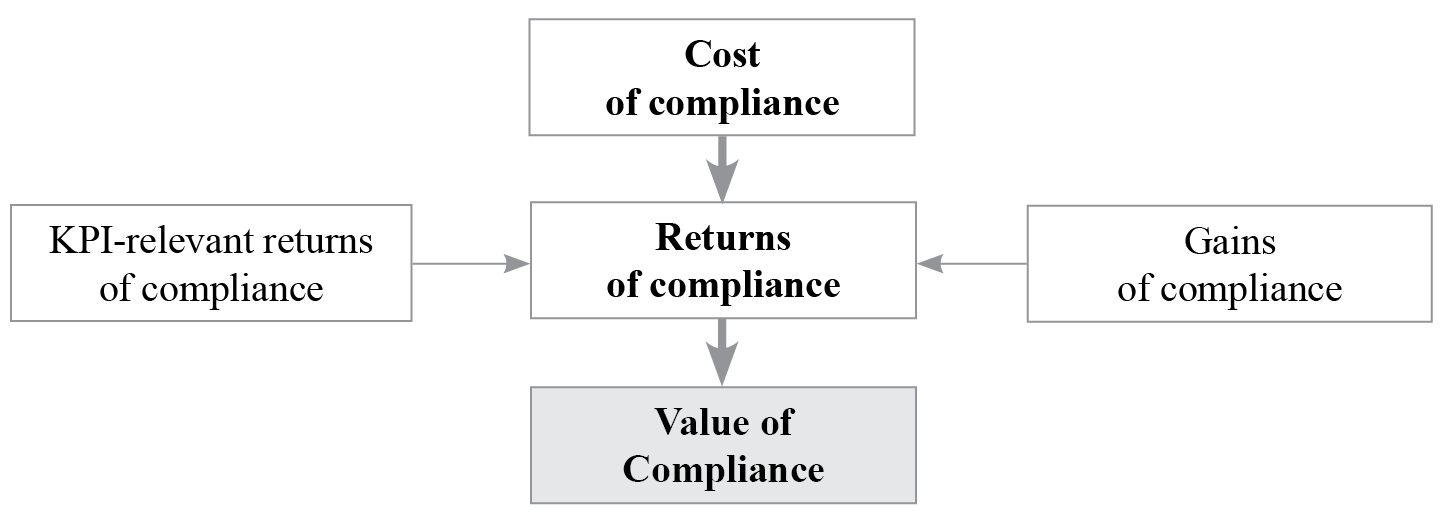

A quantified and monetarized added value (e.g., in Euro) could afterwards be transferred to other calculations such as “Return on Investment” (ROI). The generic ROI-formula is then transformed into the compliance-ROI-formula (Hastenrath and Diem 2020):

6. Systematization of the compliance returns

All compliance returns should be systematically collected and somehow clustered. One approach could be the following differentiation in two categories: KPI-relevant returns (6.1) and gains of compliance (6.2) which are explained below.

6.1. KPI-relevant returns

In scientific and practice sources, the segmentation of KPI’s is generally based on activities, results and behavior (refer to Table 1). In order to evaluate (and, later on, also to calculate) the added value of compliance, all KPI’s relevant effects have to be systematically covered. Obviously, effectiveness of a CMS can be derived if KPI’s or realization rates of compliance measures reach high percentages – especially result and behavioral based KPI’s, although this is not always valid, since there exists no ‘absolute compliance’ (refer to Chapter 4.3).

Table 1. Overview of selected activity, result and behavioral based compliance returns.

|

Activity based KPI’s |

Result based KPI’s |

Behavior based KPI’s |

|

|

- Frequency and significance of non-compliant behavior of employees - Frequency and amount of loss due to fines, sanctions, police reports, criminal prosecution of one’s own corporation - Effects of qualitative checks or audits - Effects of quantitative surveys of employees and qualitative interviews with multiplicators of compliance activities |

|

limited evaluation of the effectiveness of CMS only |

allows the evaluation of the effectiveness of CMS |

allows the evaluation of the effectiveness of CMS |

Sources: Jüttner 2020, Hastenrath and Diem 2020, Westhausen 2021

KPI based compliance returns are possibly easier to calculate and monetarize, since the structure of a KPI is quantitative in itself. However, the following example might clarify the calculation process of KPI-returns.

Assumption:

Due to an intensified anti-fraud compliance training, the number of fraud cases was reduced by 50% (refer to the fifth example in the second column of Table 1).

Calculation of the compliance return:

The average loss per case in the last five years was about 50,000 Euro with 12 cases per year. Then, the total annual compliance return is 300,000 Euro (i.e., 6 times 50,000 Euro).

6.2. Gains of compliance

The ‘gains of compliance’ are the second category of compliance returns. Here, there are manifold factors to be considered because all of them pay in the “returns of compliance” (refer to Table 2).

Table 2. Overview of selected gains of compliance.

|

Becker et al. (2011) |

PwC (2018) |

Westhausen (2021) |

- Increase of operative efficiency (25%) - Improvement of the company’s own reputation (24%) - Increase of the “operative confidence” (13%) - Improvement of the company’s own competitive position (7%) - positive correlation between compliance and the success of the corporation (53%) - positive influence on the corporate culture (no percentage given) |

|

- preventive effect (refer to Westhausen 2016) - Role model character, reputational plus - Continuity in the history of the corporation - Avoidance of non-compliant behavior and reaching penal reduction in lawsuits - Increase of the corporate value (refer to a range of empiric studies) - Reduction of additional fiscal payments and avoidance of other sanctions (e.g., by tax compliance) - better knowledge of suppliers’ and customers’ risks |

Sources: Becker et al. 2011, PwC 2018, Westhausen 2021

Measuring compliance returns based upon gains might become more difficult to calculate and monetarize in comparison to KPI based returns (e.g., how to measure the value of more legal certainty or the effect of positive influence on the corporate culture?). Yet – even if the value calculation might be difficult – the quantification of effects should be necessary for the further calculation of the added value of compliance. The following example should bring more light on the calculation of compliance gains.

Assumption:

Due to several business partner compliance measures, the operative efficiency increased (refer to the second example in the first column of Table 2).

Calculation of the compliance return:

Within the “Business partner compliance project,” the data quality of all suppliers and customers information in the relevant databases had to be updated and corrected. This step led to an improvement of the data quality of all digital data about business partners resulting in a significant time reduction in searching data and documents about business partners. The compliance return is about 20% less searching effort, i.e., 500 hours less working time for data search per year at an hourly cost rate of 50 Euro summing up to 25,000 Euro compliance return per year.

7. Calculation model for the compliance value and time series analysis

In this chapter, the previously described and quantified costs and returns of compliance are brought together in a tabular calculation model (7.1) and a statistical approach with the objective to compare the static value calculations on a dynamic, rolling basis (7.2).

7.1. Generic calculation model

The calculation model presented below can be used for any corporation as a generic prototype which is independent from the industry, company size or legal form of the corporation (Westhausen 2021). Furthermore, the model is also freely scalable, i.e., it is applicable for the calculation of an added value of a single compliance activity or segment (e.g., corruption or anti-trust) or a CMS of a whole international group. The calculation model is based on the consequent quantification and monetarization of each cost and return category that are afterwards compared with each other coming up with a surplus or minus.

In the following example, the calculation model is presented with hypothetical, but realistic business data and figures of a medium-sized corporation. The calculation basis is the annual basis. Multi-annual costs and returns are spread over the estimated years of utilization (refer to Table 3).

Table 3. Model for the calculation of the added value of compliance.

|

Costs and returns of compliance |

Utilization |

Total |

p.a. |

| Costs of compliance | |||

|

10 |

50,000 |

5,000 |

|

1 |

35,000 |

35,000 |

| Total costs of compliance | 40,000 | ||

| Returns of compliance | |||

|

5 |

100,000 |

10,000 |

|

5 |

75,000 |

3,000 |

|

5 |

100,000 |

6,000 |

|

5 |

50,000 |

10,000 |

|

5 |

50,000 |

1,000 |

|

5 |

25,000 |

500 |

|

8 |

91,000 |

11,375 |

|

1 |

25,000 |

25,000 |

| Total return of compliance | 66,875 | ||

|

Added value of compliance ROI of compliance |

26,875 67.2% |

||

Source: Westhausen 2021

It is recommended to adapt the calculation model on the KPI- and gain categories of the corporation and frequently (e.g., annually) review all positions up to the added value of all compliance activities as well as to report the calculation to the superior level (Westhausen 2021). Even if quantification and monetarization will not always be possible, it should be the goal within the model following the experience that a cautious estimation of effects is always better than a qualitative explanation. Or, as Peter Drucker used to say: “Only what gets measured, gets managed” (Klaus 2015).

7.2. Time series analysis

Initially, the comparison of the immediate quantitative effect of compliance measures is of interest, i.e., the two-period comparison between ex ante (i.e., before the introduction of compliance measures) and ex post (i.e., after the introduction of compliance measures). Later, a longer-term comparison of the development of compliance added value over several periods and an outlook (trend extrapolation) are also of interest.

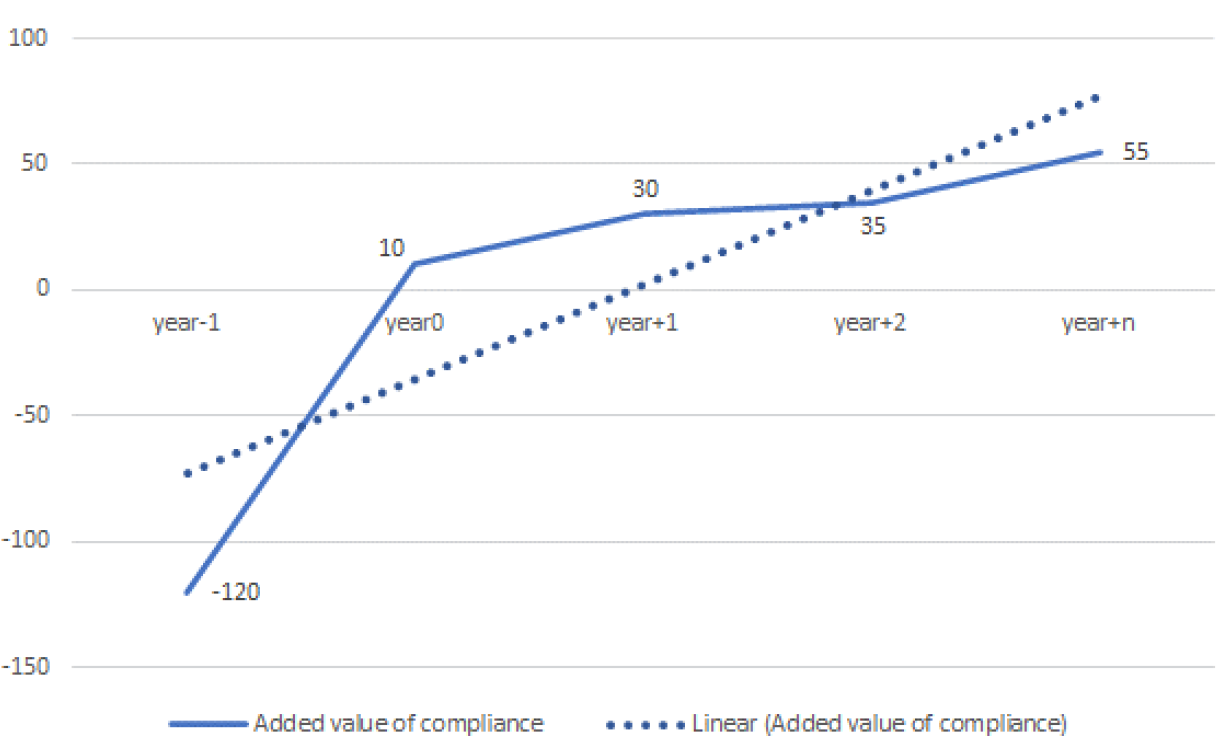

The fictitious corporate example illustrates the time series analysis (refer to Table 4) as well as the trend exploration of the compliance value (refer to Figure 4). While no CMS was in place in year-1 (ex ante), no direct compliance costs (one-off and ongoing) were incurred, but, on the other hand, 120,000 Euro was paid for assumed claims and litigation for antitrust violations. With the introduction of CMS in year0 (ex post) and the further strengthening of CMS in the following years, the implementation and maintenance costs for the CMS increase, but, at the same time, the returns of compliance increase even more. Consequently, the added value of compliance and the ROI of compliance increase (from 10,000 Euro to 55,000 Euro and from 13.3% to 68.8%).

Table 4. Comparison of five periods of compliance value calculations (in 1,000 EURO).

|

Calculation categories |

ex ante |

ex post |

|||

|

year-1 |

year0 |

year+1 |

year+2 |

yearn |

|

|

Cost of compliance |

120 |

75 |

85 |

85 |

80 |

|

Returns of compliance |

0 |

85 |

115 |

120 |

135 |

|

Added value of compliance |

-120 |

10 |

30 |

35 |

55 |

|

ROI of compliance |

-100.0% |

13.3% |

35.3% |

41.2% |

68.8% |

Source: Westhausen 2021

A look into the future of the fictitious company shows that the CMS will generate a significant added value for the owners. If we follow the corresponding linear trend equation (Y = 37.5x - 110.5), where Y corresponds to the annual compliance value and x to the respective period, we will achieve an added value of 452,000 Euro in the 15th year since the introduction of CMS. In total, the added value of the exemplary CMS appears even more impressive: 2.8 million Euro cumulative cashflow, which corresponds to a net present value of 1.6 million Euro (at 5% imputed interest).

Figure 4. Time series and trend extrapolation (based upon Table 4)

Source: Westhausen 2021

8. Discussion and conclusion

Compliance moves continuously in the focus of the corporate world, especially because of big business scandals with even bigger losses, but also as a result of the simultaneously increasing management and corporate liability for compliant organizational and operational action. A systematic and systemic approach such as the methodology of an integrated, holistic CMS seems to be an effective, practical instrument to ensure the ‘duty to legality’ in conjunction with the highest possible effectiveness of the compliance function within the ‘second line of defense’.

The general value of corporate compliance is, beyond doubt, the demonstrative power that compliance programs have for their management, employees, share- and stakeholders. Compliance is a must; non-compliance is no longer imaginable today. Managers need compliance to exclude their organizational liability, business partners hope to deal with reliable companies at lower risk levels if they are known to be compliant. From a business perspective, the detailed value of corporate compliance is of special interest because costs (or investments) need to perform well to payback soon, increasing the return (or the added value) of the investment. But here, as described in the paper, a problem with the uncertainty of the value of the compliance return and the missing quantification of the added value of compliance might (still) exist. Consequently, without a measurability of compliance effects, the manageability and acceptance of compliance activities were hard to realize.

Therefore, a standard calculation model based upon the costs and quantified returns of compliance resulting in a monetarized added value and a ROI of compliance should be developed. One drafted model calculation was presented within this paper to illustrate the discussed approach. Future research should be focusing on a generally accepted calculation model which should not only become integrated in auditing standards and ISO-norms as well as regular corporate controlling activities (‘compliance controlling’), but even more in the monitoring and quality assurance process of each CMS.

References

Aluchna, M., & Kuszewski, T. (2020). Does Corporate Governance Compliance Increase Company Value? Evidence from the Best Practice of the Board. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13(10), 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100242

Berufsverband der Compliance Manager (BCM) (2020). Der Märwert von Compliance. Compliance Manager 2, 58-59.

Becker, W., Ulrich, P., Kemmeter, S., Staffel, M., & Zimmermann, L. (2011). Compliance-Management im Mittelstand. Retrieved from https://fis.uni-bamberg.de/handle/uniba/329

Chen, H., & Soltes, E. (2018). Why Compliance Programs Fail: And How to Fix Them. Harvard Business Review 96(2), 116-125.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Qualität (DGQ) (2017, March 26). Schlüsselqualifikationen für den Compliance Officer. Retrieved from http://blog.dgq.de/5-schluesselqualifikationen-fuer-den-compliance-officer

Deutsche Welle (2020, January 31). Airbus zahlt Strafe in Milliardenhöhe. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/de/airbus-zahlt-strafe-in-milliardenh%C3%B6he/a-52219761#:~:text=Mit%20einer%20rekordverd%C3%A4chtigen%20Zahlung%20von,Airbus%20mit%20der%20Finanzstaatsanwaltschaft%20PNF

Durrer, M., & Hunziker, S. (2021). Return on Compliance. Retrieved from https://www.hslu.ch/de-ch/hochschule-luzern/forschung/projekte/detail/?pid=5709

EUR-Lex (Access to European Union law) (2021). Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/search.html?DTA=2019&SUBDOM_INIT=ALL_ALL&DTS_SUBDOM=ALL_ALL&DTS_DOM=ALL&type=advanced&excConsLeg=true&qid=1632051244315 [2015-2019]

European Commission (2019). Study on the costs of compliance for the financial sector. Retrieved from https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4b62e682-4e0f-11ea-aece-01aa75ed71a1

Fechner, R., & Baier, M. (2020). Compliance Kultur – Die Perspektiven der Organisationsleitung – Berufsfeldstudie 2020.

Giard, J., & Leblanc, C. (2021). Assessing the value of compliance Due Diligence in M&A – Insight into the challenges and benefits. Retrieved from https://www.kroll.com/en/insights/publications/financial-compliance-regulation/assessing-value-compliance-due-diligence-ma

Google Scholar (2021). Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=%22value+of+compliance%22&hl=de&as_sdt=0%2C5&as_ylo=2017&as_yhi=2017 [2005-2020]

Görtz, B., & Roßkopf, M. (2010). Kosten von Compliance-Management in Deutschland. Zeitschrift Risk, Fraud & Compliance 4, 150-154.

Grundei, J., Lopper, E., & Seidenglanz, R. (2017). Führung und Organisation der Compliance – Was macht erfolgreiche Compliance-Einheiten aus? Retrieved from https://www.bvdcm.de/sites/default/files/dateien/bcm_berufsfeldstudie_2017_issu_0.pdf

Haase, M., & Hamacher, K. B. (2012). Return on Compliance: Angemessenheit von Compliance aus betriebswirtschaftlicher Sicht. Zeitschrift Risk, Fraud & Compliance 3, 123-127.

Hammond, S., & Cowan, M. (2020). 2020 Cost of Compliance: New decade, new challenges. Retrieved from https://corporate.thomsonreuters.com/Cost-of-Compliance-2020

Hastenrath, K., & Diem, M. (2020). Indikatoren für eine erfolgreiche Compliance (ROI/KPI). Retrieved from https://docplayer.org/195878212-Indikatoren-fuer-erfolgreiche-compliance-roi-kpi.html

Institut der Wirtschaftsprüfer in Deutschland (IDW) (2011). IDW PS 980: Grundsätze ordnungsmäßiger Prüfung von Compliance Management Systemen [11.03.2011].

Jäkel, I. (2016). Compliance Management Systeme – messen und gemessen werden. Compliance Manager 3, 14-32.

Jüttner, M. (2020). Daten, die nichts bedeuten: Die (Ver-)Messung der Compliance. Compliance Business 2/2020, 18-21. Retrieved from https://www.deutscheranwaltspiegel.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/49/2020/06/Compliance-Business_Magazin_02_2020-L.pdf#page=18

Klaus, P. (2015). The Devil Is in the Details – Only What Get Measured Gets Managed, in: Measuring Customer Experience, 81-101.

KPMG (2016). Mehrwert schaffen durch die Interne Revision. Retrieved from https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/04/kpmg-compliance-internalaudit-mehrwert-sec.pdf

LG Munich I (2013). verdict December 10/2013, 5HK O 1387/10. Retrieved from https://openjur.de/u/682814.html

McCrum, D., & Storbeck, O. (2020). Wirecard says €1.9bn of cash is missing. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/1e753e2b-f576-4f32-aa19-d240be26e773

PwC (2020). Studie zum Stand der Implementierung von Tax Compliance Management Systemen. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.de/de/steuerberatung/stand-der-implementierung-von-tax-compliance-management-systemen.html

PwC (2018). Wirtschaftskriminalität 2018: Mehrwert von Compliance – forensische Erfahrungen. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.de/de/risk/pwc-wikri-2018.pdf

Reineke, R. D., & Bock, F. (ed.) (2007). Gabler Lexikon Unternehmensberatung. Rheinische Post online (2021). EU-Kommission: Die zehn höchsten Kartellstrafen. Retrieved from https://rp-online.de/leben/auto/news/eu-kommission-die-zehn-hoechsten-kartellstrafen_iid-9600361

Ruby Compliance (2020). Ist der Mehrwert von Compliance messbar? Retrieved from https://rubycompliance.com/ist-der-mehrwert-von-compliance-messbar

Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis) (2021). OnDEA – Online-Datenbank des Erfüllungsaufwands. Retrieved from https://www.ondea.de/DE/Home/home_node.html

SZ.de (2018). EU verhängt 4,3-Milliarden-Euro-Strafe gegen Google [18.07.2018]. Retrieved from https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/eu-google-android-rekordstrafe-1.4059410

Westhausen, H.-U. (2021). Compliance – Mär oder Mehrwert? Diskussion des Mehrwerts von Compliance und seiner Quantifizierung. Zeitschrift Risk, Fraud & Compliance 5, 199-206.

Westhausen, H.-U. (2016). Interne Revision in Verbundgruppen und Franchise-Systemen. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Wieland, J., Steinmeyer, R., & Grüninger, S. (ed.) (2020). Handbuch Compliance-Management.

Wirecard AG (2019). Fundamentals of the WIRECARD compliance management system. Retrieved from https://ir.wirecard.com/download/companies/wirecard/Compliance/EN_Compliance_Management_System_2018_final.pdf

YouAttest (2020). The cost of non-compliance is great [11.01.2020]. Retrieved from https://youattest.com/non-compliance

Appendix 1

Overview of relevant literature (Westhausen 2021)

|

No. |

Author(s) |

Source |

Year |

Category |

Key results regarding |

|

No. |

Author(s) |

Source |

Year |

Category |

Key results regarding |

| 1 |

Assessing the value of compliance Due Diligence in M&A – Insight into the challenges and benefits [Giard & Leblanc] |

Internet | 2021 | article |

The outcome of a pre-acquisition compliance due diligence review in an M&A process has a significant impact on the total cost of an acquisition. The better is the CMS, the higher is the takeover price of an M&A acquisition. |

| 2 |

2020 Cost of Compliance: New decade, new challenges [Hammond & Cowan] |

Internet | 2020 |

study (n: 750) |

34% of the surveyed companies had to abstain from profitable business chances due to compliance rules. |

| 3 |

Studie zum Stand der Implementierung von Tax Compliance Management Systemen [PwC] |

Internet | 2020 |

study (n > 150) |

61% of the surveyed companies graded the added value of their tax compliance systems with ‘high’. Furthermore, the added value of tax compliance was based on average at 6.7 (of 10) and above the corresponding additional costs for the operations at 6.4 (of 10). |

| 4 |

Der Märwert von Compliance [BCM] |

Compliance Manager 2/2020 | 2020 | article | Critical (ironic) challenging of the added value of compliance with a positive outlook. |

| 5 |

Indikatoren für eine erfolgreiche Compliance (ROI/KPI) [Hastenrath & Diem] |

Internet | 2020 |

study n: not available |

The measurability of compliance as activity and result based KPI’s is a ‘great challenge’. The relevance of the measurability of the success of compliance is estimated with 7.42 of 10. 40% of the surveyed companies struggle for measurement of the ROI of compliance. |

| 6 |

Ist der Mehrwert von Compliance messbar? [Ruby Compliance] |

Internet | 2020 | article | With regard to Hastenrath & Diem (refer to No. 5), it is argued that the added value of compliance is measurable if the economic consequence of the omission of the compliance function in relation to possible compliance losses is simulated (opportunity cost scenario). |

| 7 |

Daten, die nichts bedeuten: Die (Ver-)Messung der Compliance [Jüttner] |

Compliance Business 2/2020 | 2020 | article | The measurement of only activity- based compliance-KPI’s will lead to a wrong measurement and cannot answer the question regarding the effectiveness of a CMS. For that, behavioral based compliance-KPI’s will be necessary. |

| 8 |

Study on the costs of compliance for the financial sector [European Commission] |

Internet | 2019 |

study (n: 141) |

Detailed description of all costs (‘one-off’ and ‘ongoing’) to assure compliance within the finance sector of the EU. |

| 9 |

Wirtschaftskriminalität 2018: Mehrwert von Compliance – forensische Erfahrungen [PwC] |

Internet | 2018 |

study (N: 500) |

60% of the questioned companies evaluate their CMS as ‘rather beneficial’ or even as ‘clear competitive advantage’. The existing CMS had reportedly positively influenced the course of ongoing lawsuits (i.e., proceedings were closed at 43%, and penal fines were reduced at 37% of the surveyed cases). |

| 10 |

Why Compliance Programs Fail: And How to Fix Them [Chen & Soltes] |

Harvard Business Review 2/2018 | 2018 | article | Corporations spend millions of dollars for compliance as a ‘box-ticking exercise’ without watching the effectiveness of the corresponding measures, or they come to biased decisions based upon wrong KPI’s. |

| 11 |

Mehrwert schaffen durch die Interne Revision [KPMG] |

Internet | 2016 |

study (n > 400) |

The compliance function in most companies (45%) engages in the groupwide risks. |

| 12 |

Compliance Management Systeme – messen und gemessen werden [Jäkel] |

Compliance Manager 3/2016 | 2016 | article |

Reference to the ISO-norm 19600 which stipulates in Chapter 5.3.4 that the performance of compliance should come under scrutiny of a monitoring and a measurement according to defined KPI’s. An extensive compilation of success factors for compliance (KPI’s) is discussed. |

| 13 |

Return on Compliance: Angemessenheit von Compliance aus betriebswirtschaftlicher Sicht [Haase & Hamacher] |

ZRFC 3/2012 |

2012 | article |

Investment in compliance should follow the cost-benefit-optimum (marginal benefit/marginal cost). The more compliance measures are conducted, the more compliance risks should exist. The benefit of compliance consists of the risk reduction; the costs of compliance are 80% personnel costs (standard ratios are 1:240 FTE at banks and 1:11,300 FTE in the logistics/transportation sector). |

| 14 |

Compliance-Management im Mittelstand [Becker, Ulrich, Kemmeter, Staffel & Zimmermann] |

Internet | 2011 |

monograph with study (n: 173) |

No added value measurement of compliance is presented, but a qualitative compilation of compliance gains that are compared with the efforts for compliance. For 38% of the surveyed companies, the advantage of a CMS outweighs the efforts; for 48%, advantages and efforts of a CMS are level, whereas, for 14%, the efforts of a CMS outweigh the advantage(s). |

| 15 |

Kosten von Compliance-Management in Deutschland [Görtz & Roßkopf] |

ZRFC 4/2010 | 2010 | article | Elaboration of a risk and cashflow based decision rule: if the potential cashflow of the total loss due to the risk expectancy value of all compliance risks (i.e., monetary loss multiplied with the risk expectancy in %) is lower than the cashflow for the implementation of a CMS, then, a CMS should not get implemented, and vice versa. |