Informacijos mokslai ISSN 1392-0561 eISSN 1392-1487

2020, vol. 89, pp. 43–54 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2020.89.39

Types of Film Production Business Models and Their Interrelationship

Ieva Vitkauskaitė

PhD student, Institute of Social Sciences and Applied Informatics, Vilnius University, Kaunas Faculty

Email: vvvieva@gmail.com

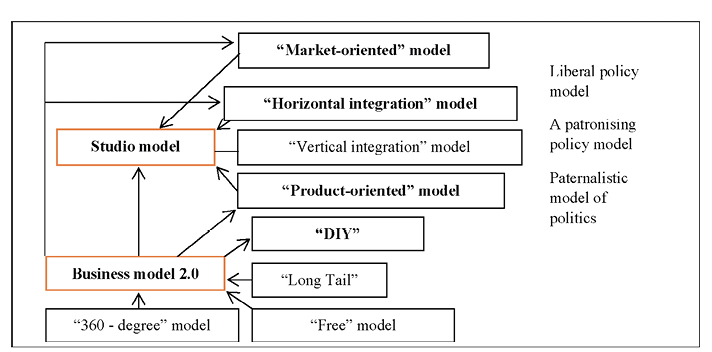

Summary. Types of film production business models are not a widely studied area in the scientific literature, and more attention is paid to the production of individual films, specifics. In this article, ten types of business models of film production companies were analysed and systematized, and the relationships between them were established. The analysis of the models identified two main, major business models: the studio model and the Business model 2.0, which becomes part of all other business models. The studio model directly includes the vertical integration model. It also consists of a “Market-oriented” model, “Horizontal integration”, “Product-oriented” model. Business model 2.0 can consist of: “Long Tail”, “Free” model and “360 - degree” models.

Keywords: Film business, business models of film production companies, relationships between film production company business model types, film production company, business model types.

Received: 01/12/2019. Accepted: 01/03/2020

Copyright © 2019 Ieva Vitkauskaitė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Like all businesses, the film business works by making money, but that is all to be the same. In this business, tens of millions of dollars can be invested to create a single product without a real guarantee that the public will buy it (Squire, 2017). Film production, which is mostly not part of the Hollywood system is fragmented, poorly structured, making it an even more complex business (Finney, 2008). It should be noted that for the film production companies it is essential not only to generate direct economic value, creating a fun user-per-view film, but, depending on the film character, can convey particular social messages, to cultivate artistic perception, to raise the debate on specific issues, sometimes even “install” society with certain ideologies, political beliefs. Through the films produced, it is often possible to predict the company’s goals.

Globalisation and technological change are creating a global film industry, accelerating competition, so to remain in the market; they are even more encouraging companies to develop and improve business models. At the moment, for instance, digital technologies allow the distribution of films on the internet, the user can be accessed anywhere, regardless of the available device. In addition to theatrical (physical) distribution, digital distribution and alternatives to film display are emerging.

The focus on the business model in the scientific literature ranges from the product, business, company levels to a much more general industrial level (Wirtz, Pistoia, Ullrich, Gotell, 2016). However, what concerns the business models of film production companies, it is not a widely studied area. More attention is paid to the production of individual films, especially when analysing the European Film Industry. The film is a complex product. Based on the levels of the business model, it is assumed that each film also has a particular business model. It means that the company’s business model also incorporates the product level. The company’s overall business model (and vice versa) is taken into account when developing the product, but at the same time, some aspects of the business model can be adjusted and adapted for each film individually. Each level of the business model is interconnected.

The article aims at revealing the business models of film production companies and the relationships between them. To this end, the article aims to systematize and analyse the types of business models of film production companies. This article contributes to the development of the management of film production companies in academic discourse, since the types of the business model of film production companies are not a widely studied area in the scientific literature, in general, more research is done on individual films, production.

Types of business model

Studio model

J. E. Squire (2017) argues that it is a traditional business with an addiction to a costly global franchise. It is assumed that the film franchise is developed from a series of films to completely new, different products (for example, theme parks). However, there is no explanation as to how traditional business should be perceived, because, as mentioned in the introduction, the film business, like a traditional business, exists to make money, but it ends up being compared to other businesses. It is assumed that the main feature of the model is the pursuit of profit through the satisfaction of consumer needs. The main product – the film – is created to please the “taste” of mass society. According to M. Lorenzen (2008), consumers’ taste for films is difficult to predict (Lorenzen, 2008), but predictive attempts are made through film screenings, focus group tests, positioning tests, idea tests (Marich, 2005). According to F. M. Simon, R. Schroeder (2019), big data analysis is now increasingly used to predict the film’s future viewer-ship and profitability. Massive amounts are allocated to film commercials; for example, in the United States, the average marketing costs can reach 35-45 million dollars per film. Thus by using the analysis of the volume of big data allows for a more accurate, detailed analysis of customer information and narrow, specific segmentation of customers. By analysing various data sources, individual, targeted film marketing strategies are applied, films are sold to target consumers. New technologies make it possible to measure audiences systematically, allowing better control over which audience is targeted and how to tailor products to the right users. However, questions remain about how the databases are to be analysed, as in France, for example, film directors have a more considerable influence on revenue forecasting than in other countries where genres are the determining factors.

It is argued that the analysis of big data in the future can change the entire film industry, because various data, methods of analysis can be combined, fully used for all types of films, marketing tools. However, what concerns the production process it is debatable, as the artistic values of the creators may not coincide with the “rationalization” of the film (Simon, Schroeder, 2019). F. M. Simon, R. Schroeder (2019) provides an example of the film “Casablanca” (directed by M. Curtiz, USA, 1942) that this film would not have become a classic if the main characters had met again at the end of the film. What the audience wants does not mean it needs it. It is also assumed that if company executives put pressure on creators to make films as consumers want, resistance is possible, creation of new cinema movements (the positive consequence of cinematography, development of art), independent film companies. Big data analysis is more useful in marketing.

The studio model is used by major film companies/studios, Hollywood companies, where the state pursues a liberal film policy model. The studio model includes a horizontal integration model, since, concerning A. Finney, E, Triana (2015), studios exploit this. Various types of productions are included; the audience is maximized with the production, distribution of films, television, games and other production. There is no narrowing of the user base to a single sector or demographic unit. It is assumed that the components of the company’s business model are expanded to international and new markets, not limited to the development of just one product.

Large film studios use a vertical integration model (Finney, Triana, 2015). For instance, the film company Paramount uses a three-sector vertical integration model, which consists of stages of production, distribution, display. Funds remain in one company (Silver, 2007). A classic example of a vertical integration model is Hollywood studios in 1920 and 1930. At that time, they included actors, directors, production studios, a distribution network and networks of cinemas. Studios controlled everything strictly (Bloore, 2013). Therefore, this model is attributed to the studio model.

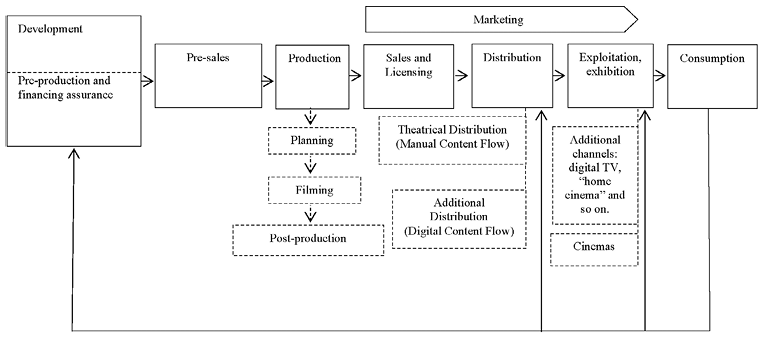

It should be noted that at present, there is no need to have a network of cinemas in order to keep all the funds in one company. Films can be shown through digital technologies, the creation of paid online film bases, the use of internet TV, etc. The advent of the internet has adjusted the display stage in the film value chain (Fig. 1). It should be pointed out that parts of the value chain are also reflected in the structure of the film industry. Film studios try to control as many parts of the value chain as possible. It indicates the market share the company owns.

The value chain includes all companies and individuals working at the stage of film production, distribution (Kehoe, Mateer, 2015) and exhibition/exploitation: from major film studios, independent film production companies, independent distributors to major exhibition companies (for example, a network of cinemas) (Eliashberg, Elberse, Leenders, 2006).

As seen in Fig. 1., the production stage consists of planning, filming and post-production. However, the production stage can only consist of filming, and the post-production become another critical part of the film value chain after the production stage. The final works of the film, like the development ones, can be done by another company, independent developers. In Europe, international co-production in film production is developing, which allows to strengthen the European Film Industry and expand the market.

Fig. 1 Film Value Chain

Source: compiled by Eliashberg, Elberse, Leenders, 2006; Kill, Taylor, 2010; Küng, 2008; Finney, 2014.; Wirtz, 2011; Nilsen, Smistad, 2012.

The distribution phase consists of theatrical (through a flow of manual content) and additional distribution (through a flow of digital content) (Fig.1). According to J. Eliashber, A. Elberse, M. Leenders (2006), large film studios not only distribute their created products, but also independent filmmakers who work for them to that. It is assumed that they also distribute the products of other companies following certain agreements. It should be argued that each element of the value chain is interdependent and closely interdependent. As seen in Fig. 1, this is a cyclical process, consumption is analysed, and specific factors are constantly being improved at the distribution, display stage and the new films created. A distinction is also made between the marketing stage, which begins after the production stage is completed and continues until the display stage reaches the end-user. N. Daidj (2015) argues that marketing must take place at all stages, starting with the preparatory work. However, it is assumed that launching marketing in the first stage, when the budget is still being planned, and funding is being sought, is risky. It can be done by major film companies, not by independent film companies because they are not guaranteed that their planned film will receive funding. The film producer is looking for various sources of financing, which are grouped into three main types of financing:

- industry sources (e.g. pre-distribution funds);

- lenders, creditors (for example, banks);

- investors (Vogel, 2007).

C. Chapain, K. Stachowiak, (2017) distinguishes an innovative way of financing: crowdfunding and specialized banks or film investment funds. However, it is assumed that crowdfunding benefits low-budget films and calls into question whether the company can raise the necessary funds for each film. It is more relevant for a new player in the market, who is just starting to build a film and has no initial capital. It should be noted that K. H. Hofmann (2012) distinguishes between slate financing, where a bank or investment company creates and manages a film fund by raising funds, capital from various private and institutional investors. The funds are invested in the co-financing of many projects for several years. Slate funding can also be described as a group of funds involving a group of individual investors, but can also refer to co-financing partnerships between major film studios. The duration of participation in profit sharing depends on the terms of the contracts concluded and can last from three years to eternity. Typically, a group investor finances 10 to 30 films and covers 10 to 50 per cent of the production costs of a single project. It is assumed to be financing through the pooling of investors through the creation of funds, or cooperation, through the sharing of production costs and profits, between film production companies for the production of a film. However, this is more likely in countries where there is a liberal policy model, and investment is more focused on the production of dominant films.

It makes sense for European companies to start marketing at a time when the initial funding is available, and the production of the film starts. European film production companies must not be limited to the national market if they want to expand and produce as many films as possible. If the analysis from a financial perspective, A. Finney, E. Triana (2015) argues that it is not ordinarily possible for a national film producer to recover funds for a film produced from a single territory, especially in Europe, where most territories are not large enough, as in Japan, for example.

In independent film production, more market players are involved, on which the creation, realization of the film depends. The most complex is the financing and pre-sale phase. P. Bloore (2009) argues that, from an investment point of view, film is the most expensive art form (next to architecture). Each investor has his own needs, creative approaches that can affect the film. At this stage, independent film often involves a large group of business collaborators, consultants, investors (Bloore, 2009).

Each stage of the value chain extends for a specified time interval. For example, the stage of development includes 2-8 years, financing and pre-sale – ½-2 years, production – ½ year, and so on. However, this does not mean that such time intervals are always present. For each film, the time interval varies; it all depends on the volume of the film and other aspects (Bloore, 2009). It is claimed that some film projects do not even reach the production stage because some of the previous stages have not been completed. There is no assurance that the work of producers, writers, ideas will create value. The relationship between the European film producer, the sales and the distributor is not stable in principle (Finney, 2014), which gives an additional risk to the film product. It is assumed that at the moment independent film production companies are increasingly trying to enter prestigious film festivals, awards, fairs. That is, first of all, films are created for the festival market. A. Finney, E. Triana (2015) states that, in most cases, independent filmmakers do not have a Hollywood-type studio infrastructure (Finney, Triana, 2015). It is assumed that the studio model is not easily implemented in European countries. However, a film production company may sell part of the shares, for example to a distribution company or expand its company and “take” another part of the value chain, not to use the full vertical integration model, but to use the horizontal integration model, to introduce new products, services into the market.

“Product-oriented” model

Decisions focus on the product, trying to achieve the best possible quality of the product. It is expected that the market will appreciate the quality of the product presented. This model is most often used by film producers (Guild, Joyce, 2006). It is considered that the model does not represent the total product, the “way” of the company, but, like every film, has its value chain. If European film production companies use this model, films are more focused on the international festival awards market. Companies do not analyse the mass market.

“Market-oriented” model

Films are adapted to the market, and all decisions are made according to the film market (Guild, Joyce, 2006). It is believed that, contrary to the “Product-oriented” model, this model does not emphasize product quality. However, this largely depends on the selected market. If the European film production company takes into account the subtleties of the film festival market, the products to be developed will be of a certain quality, if the masses are likely to be the mainstream cinema, if a particular segment of the consumer, depending on the educational characteristics, is expected to be art-house, etc. The production and content of films also depend on the policy model pursued, especially if the paternalistic model is followed. It should be noted that the “Market-oriented” model can also become part of other models.

The basis of Business model 2.0

is the internet, online platform (Finney, Triana, 2015). W. Nilsen, R. Smistad (2012) argue that the internet and information technologies have the intention to adjust the value chain by allowing innovation to develop more in the stages of film production, licensing, distribution and exploitation.

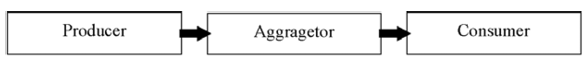

As digital technologies evolve, companies’ business models are also being adjusted. For example, digital animation is created through computer graphics programs; a film is viewed through an online video feed, various international contracts with distribution companies, etc., are signed and concluded electronically. It should be noted that digital technologies adjust the value chain (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 New value chain

Source: Finney, 2014, p. 6.

The new value chain (Fig. 2) highlights the main participants in the film industry: producers, aggregators, and consumers. In this case, the aggregators are considered to be companies such as Google, Amazon, Apple, Netflix (Finney, 2014). Distribution, exploitation face a great revolution. In the future, aggregators will have increasing influence and control over the structure of the emerging industry structure. In comparison with traditional distribution, the producer becomes closer to the consumer, resulting in revenue streams being restored (Finney, Triana, 2015). The digital distribution gives filmmakers more control over usage, more success in reaching their target audience. Independent filmmakers see the internet as the future of a more democratic distribution platform. However, the question for most leading online film database remains: how to attract a new audience without the release of films by major film companies (major film releases) (Finney, Triana, 2015).

Business model 2.0 includes the business model “Long Tail” – many niche products in online trade. Many different products are presented, but sold in small units, irregularly (Osterwald, Pigneur, 2010). Free products can also be provided to consumers (Jucevich, UUS, 2012). It is believed that this model can also be joined by a “Free” model, based on which at least one client segment can access the offer free of charge because it is paid for by another part of the business model or another customer segment (Osterwalder, Pigneur, 2010).

“360 - degree” model – “the future is now” – a multichannel world, where the consumer has a vast choice among the products created (Finney, Triana, 2015). The model consists of value creation, proposal, catch, delivery, communication. As an example of the model can be companies such as Netflix, Spotify (Rayna, Striukova, 2016). This model can also be part of Business model 2.0. New products, projects available to most users. It is assumed that significant film studios can be regarded as more of distribution companies because they focus on distribution in different markets and exploit this model. More revenue channels appear. For example, the company Netflix at the moment not only distributes films and uses this online business model, but also began to produce films. It means that this model, with the establishment of digital film databases and the expansion of markets, later becomes an opportunity to take on more significant risks and finance, control the film budget, the production process. Digital distribution companies are adjusting their business model with new activities – film production. It means that the 360 - degree model is combined with the vertical integration model.

It should be noted that with the development of digital technologies, the entire film industry is faced with the problem of illegal online distribution (also known as online piracy). According to F. M. Simon, R. Schroeder (2019), big data analysis is now increasingly used to understand online piracy. Analysis of film piracy and its tracking allow us to understand the pre-release demand. However, box-office revenue can be reduced by up to 19% by piracy. It is assumed that this is an incentive to adjust the theatrical distribution business model, since, according to P. Aversa, A. Hervas-Drane, M. Eveou (2019), digital distribution can surpass piracy by improving the consumer experience. There is a strong focus on accessibility, convenience, better browsing, facilitating social interaction and sharing experiences that do not exist in digital piracy. It is thought that not only does it encourage the development of digital business models, but the analysis of piracy enables the analysis of new markets. For example, when a company sees high levels of piracy in the country and the analysis shows that consumers have little or no access to legal digital content, it can start to develop a horizontal business model and “enter” a new market by offering access to a legal and high-quality product, etc. It is like testing a new market.

“DIY” – a micro-budget model that is increasingly developing in the online space, often with the limited theatrical display. It is a new model that interests developers most (Squire, 2017). The basis is the distribution of films on online platforms. Sometimes it gives filmmakers more opportunities than traditional distribution.

The model also includes attracting money by electronic means, determining marketing strategies, demographics of the target audience before filming, sales at film festivals and so on, by bypassing traditional theatrical distribution, which means the use of video-on-demand services (for example, Amazon Prime, iTunes, Netflix, Hulu Plus, Youtube). The filmmaker or team retains all rights to the project (Squire, 2017).

Essential parts of the “DIY” model:

- team building (talent pool, often friends working together on small projects), script, budget;

- setting target demographics; achievement of financing (crowdfunding; most effective using particular websites such as Kickstarter.com), money from friends, family, wealthy individuals, credit cards, affinity group;

- strategic planning;

- website launches, short film trailer, and social media drivers, festivals and distribution choices;

- production; digital marketing tools;

- the final works of the film, testing the film, preliminary review usually take place with family, friends;

- applications for festivals;

- realization (Squire, 2017).

It is assumed that the “DIY” model is often used in or after film schools when young filmmakers are still trying to “enter” the market. In Europe, small film production companies or emerging market players can also combine this model with other models.

Relationship between business model types

The analysis of the types of the business model identified the links between them (Fig. 3). As can be seen from the figure, the vertical integration model is the central part of the studio model. The studio model also includes the “Market-oriented” model, “Horizontal integration”, “Product-oriented” model and “Business model 2.0”, which may also exist as stand-alone business models or integrate, complement each other or other business models. The “Market-oriented” model is the opposite of the “Product-oriented” model. “Business model 2.0 consists of: “Long Tail”, “Free” model and “360 - degree” model. It should be noted that these models do not have to be used all at once, but they can complement each other.

With the increasing development of digital technologies, business model 2.0 is becoming part of all other business models. Thus, close links and various mutual variations are possible between all types of business models.

Fig. 3 Business model relationships

Source: compiled by the author with regard to Squire, 2017; Finney, Triana, 2015; Guild, Joyce, 2006; Osterwald, Pigneur, 2010.

It should be noted that the use, choice, and adaptation of business models depend on the country’s film policy, as the state policy affects the business model of film production. The state controls the sphere of art, culture. According to A. Rimkutė (2009), the incentives for policy implementation are financial, legal and socio-psychological. The state can support directly (for example, education, subsidies) or indirectly (for example, the tax system) (Hagoort, 2001). However, the state can also use restrictive measures: taxes, public condemnation, censorship, various fines, restrictive legislation (Rimkutė, 2009). It is assumed that financial and legal instruments have the most influence on the business model of the film production company.

The use of the measures depends on the state model of cinema policy. It should be noted that each state has its separate level of state control, as do companies: how many companies, and business models, which can be classified according to recurring vital features. Thus, three main policy models are distinguished according to the level of state control (Fig. 3):

- Liberal model – culture (film sector) is left to the market (Rimkutė, 2009). The state has almost no control over the film industry. It supports indirectly through a particular tax system, etc. Film companies operate under market conditions. The content of films often depends on the attitude of investors, the needs of consumers. The liberal model of film policy is carried out in countries, for example, the USA.

- Patronising model – “Arm’s length” principle – funding is carried out on the principle of “respectful distance” (Rimkutė, 2009). It means that the state is setting particular political objectives and allocating funding, but does not regulate whom it will go to. All decisions on who award funding to are taken by the board formed from professional film experts. Support is given to ensure the quality, distribution, etc. of products developed by the film industry. The closest to such a model are Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, and other Nordic countries. Since 2012 this model has also been launched in Lithuania, the Lithuanian Film Centre has been established, and the Film Council has been formed.

- Paternalistic model – the state controls the cultural sector (Rimkutė, 2009). It regulates, supports, supervises the film industry through various means: direct, indirect, sponsorship. The state becomes the leading financier of the film sector. An example of such a model of film policy can be Azerbaijani cinematography since all film production is financed from the state budget. Support is provided to various studios and independent filmmakers, producers. National cinematography is the priority (Huseynli, 2016).

Although the influence of politics is an external factor and is not part of the business model, as can be seen from policy models, the state can even provide direct funding (paternalistic model). It means that a film production company can have financial stability, and its functioning does not depend solely on market conditions as in a liberal policy model. The business model is developed and improved not only concerning markets but also to the policy model, as it directly affects the company’s activities not only in the financial aspect but also, for example, censorship.

Conclusions

Ten types of the business model are identified and systematized. The vertical integration model, which incorporates elements of the film value chain, is a vital part of the studio model (a business with a costly global franchise). The studio model also includes a “Market-oriented” model (the full role goes to the market), horizontal integration (expansion to new markets), a “Product-oriented” model (film quality plays a vital role) and a business model 2.0 (digital business model, internet-based), which can also exist as stand-alone business models or integrate, complement each other or other business models. Business model 2.0 consists of: “Long Tail” (many niche products in online commerce), a “Free” model (at least one customer segment can use the offer for free) and a “360 - degree” model (“the future is now” – multichannel world). They do not need to be used all at once but can complement each other. Business model 2.0 usually combines with other business models. The “DIY” model is developing in the online space, bypassing traditional distribution, involves raising money by electronic means and most often these are micro-budget films.

Ongoing state policy affects the business models of film production companies. Three main policy models are distinguished according to the level of state control: liberal (film sector is left for the market), patronising (funding is carried out on the principle of “Arm’s length” principle) and paternalistic (state control of the film sector). Business models are developed, improved concerning the level of state control.

References

Aversa, P., Hervas-Drane, A., Eveou, M., 2019. Business Model Responses to Digital Piracy. California Management Review, 2019, 1-19 psl.

Bloore, P., 2009. Re-defining the Independent Film Value Chain. London: UK Film Council.

Bloore, P., 2013. The Screenplay Business: Managing Creativity and Script Development in The Film Industry. New York: Routledge.

Chapain C., Stachowiak K., 2017. Innovation dynamics in the film industry: The case of the Soho cluster in London. In: Chapain C., Stryjakiewicz T. (eds), Creative industries in Europe: Drivers of new sectoral and spatial dynamics. Springer, Cham: 65-94.

Daidj, N., 2015. Developing Strategic Business Models and Competitive Advantage in the Digital Sector. US: IGI Global.

Eliashberg, J., Elberse, A., Leenders, M. A. A. M., 2006. The Motion Picture Industry: Critical Issues in Practice, Current Research, and New Research Directions. Marketing Science, 25(6):368-661.

Finney, A., 2008. Learning from Sharks: Lessons on Managing Projects in the Independent Film Industry. Long Range Planning, 41:107-115.

Finney, A., 2014. Brave New World an Analysis of Producer / Distribution Joint Ventures. A report commissioned by Film Cymru Wales and Creative Skillset [pdf].

Finney, A., E. Triana, 2015. The International film business: a market guide beyond Hollyvood. New York: Routledge.

Guild, W. L., Joyce, M. L., 2006. Surviving in the Shadow of Hollywood: A Study of the Australian Film Industry. From Lampel, J., Shamsie, J., Lant, T. (ed.), 2006. The Business of Culture: Strategic Perspectives on Entertainment and Media. UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hagoort, G. 2001. Meno vadyba verslo stiliumi. Vilnius: Kronta.

Hofmann, K. H., 2012. Co-Financing Hollywood. Film Productions with Outside Investors. An Economic Analysis of Principal Agent Relationships in the U. S. Motion Picture Industry. Germany: Springer Gabler.

Huseynli, Y. 2016. Country profile Azerbaijan. Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe [pdf].

Jucevičius, G., UUS, I., 2012. Verslo modelio inovacijos: teorija ir atvejai. Mokomoji knyga. Kauno technologijos universitetas.

Kehoe, K., Mateer, J., 2015. The Impact of Digital Technology on the Distribution Value Chain Model of Independent Feature Films in the UK. International Journal on Media Management, 17(2):93-108.

Kill, R., Taylor, L., 2010. Cinema and Film. From Moss, S. (ed.), 2010. The Entertainment Industry: An Introduction, UK: CABI.

Küng, L., 2008. Strategic Management in the Media: theory to practice. London: SAGE Publications LTd.

Lorenzen, M., 2008. On the Globalization of the Film Industry. Creative Encounters Working Papers. Copenhagen Business School, p. 1-16.

Marich, R., 2005. Marketing to Moviegoers: A Handbook of Strategies Used by Major Studios and Independs. Oxford: Focal Press.

Nilsen, A. W., Smistad, R., 2012. ICT challenges and opportunities for the film industry – a value chain perspective on digital distribution. Project report [pdf].

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., 2010. Business Model Generation. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Rayna, T., Striukova, L., 2016. 360° Business Model Innovation: Toward an Integrated View of Business Model Innovation. Research – Technology Management, 59(3):21-28.

Rimkutė, A., 2009. Kultūra kaip politikos objektas. Iš Svičiulienė, J. (sud.), 2009. Kultūros vadyba, 1 t. Vilnius: VU leidykla, 17-46.

Silver, J. D., 2007. Hollywood‘s dominance of the movie industry: How did it arise and how has it been maintained? A thesis submitted in accordance with requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy [pdf].

Simon, F. M., Schroeder, R., 2019. Big Data Goes to Hollywood: The emergence of Big Data as a Tool in The American Film Industry. From Hunsinger, J., Matthew, M. A., Klastrup, L. (ed.), 2019. Second International Handbook of Internet Research, 1 t. UK: Springer.

Squire, J. E., 2017. Introduction. From Squire, J. E. (ed.), 2017. The Movie Business Book, Fourth Edition. NY: Routledge.

Vogel, H. L., 2007. Entertainment Industry Economics. A guide for financial analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wirtz, B. W., 2011. Media and Internet Management. Germany: Gabler Verlag.

Wirtz, B. W., Pistoia, A., Ullrich, S., Gotell, V., 2016. Business Models: Origin, Development and Future Research Perspectives. Long Range Planning, 49:36-54.