Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2021, vol. 76, pp. 228–259 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2021.76.82

Of Men and Masculinity: The Portrayal of Masculinity in a Selection of Award-Winning Australian Young Adult Literature

Kasey Garrison

Charles Sturt University

Locked Bag 588, Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678, Australia

E-mail: kgarrison@csu.edu.au

Mary Carroll

Charles Sturt University

Locked Bag 588, Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678, Australia

E-mail: macarroll@csu.edu.au

Elizabeth Derouet

Charles Sturt University

Locked Bag 588, Wagga Wagga, NSW 2678, Australia

E-mail: ederouet@csu.edu.au

Summary. This research investigates the portrayal of masculinity in Australian young adult novels published in 2019. The novels were taken from the 2020 Children’s Books Council of Australia (CBCA) Book of the Year for Older Readers Notables List. Established in 1946, these annual awards are considered the most prominent and prestigious in Australian children’s and young adult literature and are likely to be accessible and promoted to young readers in schools and libraries. The three texts studied were Four Dead Queens by Astrid Scholte, The Boy who Steals Houses by C.G. Drews, and This is How We Change the Ending by Vikki Wakefield. Using a Critical Content Analysis methodology (Beach et al., 2009), researchers completed a review of the literature and theories around masculinity and chose to analyse three exemplary texts using the attributes of the Hegemonic Masculinity Schema (HMS) and Sensitive New Man Schema (SNMS) as described by Romøren and Stephens (2002). Attributes from the HMS include traits and behaviours like being violent, physical or verbal bullying, and hostile to difference while attributes from the SNMS include being supportive, affectionate, and considerate and respectful of the space and feelings of others (especially females). In this method, researchers identify examples of the attributes within the main characters and minor characters from each of the three books, recording quotes and noting critical incidents depicting aspects of masculinity. Notable findings of the research include the acknowledgment and portrayal of a particular conception of hegemonic masculinity in the selected novels often informed or shaped by the presence of dominant father figures and the absence of the concept of “the mother.” The characters who aligned to the schema used within this research are often overshadowed by a dominant father figure who conformed to an extreme version of hegemonic masculinity and who shaped their child’s actions even if the fathers were absent from the novel. The research reveals commonly held conceptions of masculinity aligned to those used in the schema and demonstrated that young adult literature, like popular media, can be used as a vehicle for the dissemination of such concepts and reveal contemporary understandings of it. Outputs from this research include the development of a modified and more contemporary schema which could be applied to future research. Significantly, this interdisciplinary research bridges the library, education and literature fields to examine the different ways maleness and masculinity are depicted to young adult readers in prize-nominated Australian young adult novels.

Keywords: Hegemonic Masculinity, Critical Content Analysis, Young Adult Literature, You People’s Book Awards, Australian Book Awards, Australian Young Adult Literature.

Vyrai ir vyriškumas: vyriškumo vaizdavimas apdovanojimų sulaukusios Australijos jaunimo literatūros rinkinyje

Santrauka. Šiame tyrime nagrinėjamas vyriškumo vaizdavimas 2019 m. išleistuose Australijos jaunimui skirtuose romanuose. Romanai buvo pasirinkti iš 2020 m. Australijos vaikų knygų tarybos (angl. Children’s Books Council of Australia – CBCA) sudaryto Metų knygos vyresniems vaikams vertingų kūrinių sąrašo. Įsteigti 1946 m., šie kasmetiniai apdovanojimai yra laikomi žymiausiais ir labiausiai prestižiniais Australijos vaikų ir jaunimo literatūroje ir, tikėtina, bus pristatomi jauniesiems skaitytojams mokyklose bei bibliotekose. Trys nagrinėti tekstai buvo Astridos Scholte „Keturios mirusios karalienės“ (Four Dead Queens), C. G. Drews „Jaunasis įsilaužėlis“ (The Boy who Steals Houses) ir Vikki Wakefield „Štai kaip pakeičiame pabaigą“ (This is How We Change the Ending). Pasitelkdami kritinės turinio analizės metodiką (Beach ir kt., 2009), tyrėjai užbaigė literatūros ir vyriškumo teorijų apžvalgą ir pasirinko išnagrinėti tris pavyzdinius tekstus naudodami hegemoninio vyriškumo schemoje (HVS, angl. HMS) ir jautriojo naujojo žmogaus schemoje (JNŽS, angl. SNMS) nurodytus požymius, kuriuos aprašė Romørenas ir Stephensas (2002). HVS požymiai apima tokius bruožus ir elgesį kaip smurtą, fizines ar žodines patyčias ir nepakantumą kito skirtingumui, o JNŽS požymiai – palaikymą, švelnumą, dėmesingumą ir pagarbą kitų (ypač moterų) erdvei ir jausmams. Taikydami šį metodą, tyrėjai nustato kiekvienos iš trijų knygų pagrindinių ir nepilnamečių personažų požymių pavyzdžius išskirdami citatas ir atkreipdami dėmesį į esminius įvykius, atspindinčius vyriškumo aspektus. Įsidėmėtinos tyrimo išvados yra tam tikros hegemoninio vyriškumo sampratos pripažinimas ir vaizdavimas pasirinktuose romanuose, neretai pateikiamas ar formuojamas dėl dominuojančių tėvo paveikslo buvimo ir „motinos“ sąvokos nebuvimo. Šiuos herojus, siejamus su šiame tyrime naudojamos schemos požymiais, dažnai nustelbia dominuojanti tėvo figūra, atitinkanti kraštutinę hegemoninio vyriškumo versiją bei formavusi savo vaiko veiksmus tėvui net nedalyvaujant kūrinyje. Tyrimas atskleidžia dažniausiai pasitaikančias vyriškumo sampratas, suderintas su schemoje vartojamomis, ir atskleidė, kad jaunimo literatūra, kaip ir populiarioji žiniasklaida, gali būti naudojama kaip tokių sąvokų platinimo priemonė, atskleidžianti šiuolaikinį jos supratimą. Šio tyrimo rezultatai apima modifikuotos ir labiau šiuolaikiškos schemos sukūrimą, kurią būtų galima pritaikyti būsimiems tyrimams. Pažymėtina, kad šie tarpdisciplininiai tyrimai sujungia bibliotekas, švietimo ir literatūros sritis, kad būtų galima išnagrinėti skirtingus būdus, kaip vyriškumas yra pateikiamas jauniesiems skaitytojams apdovanojimams nominuotuose Australijos jaunimo romanuose.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: hegemoninis vyriškumas, kritinė turinio analizė, jaunimo literatūra, „Young People’s Book Awards“, Australijos knygų apdovanojimai, Australijos jaunimo literatūra.

Received: 2020 12 29. Accepted: 2021 04 10

Copyright © 2021 Mary Carroll, Kasey Garrison, Elizabeth Derouet. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

This research investigates the portrayal of masculinity in books nominated for the Children’s Books Council of Australia (CBCA) 2020 Book of the Year for Older Readers. The purpose of this research was to explore these depictions using a critical content analysis methodology and schemata adopted from the literature to identify traits associated with traditional Western images of masculinity. Our research question for this project is:

How is masculinity portrayed in contemporary award-winning Australian young adult literature?

This initial question led to further questions about the ways in which masculinity has been defined in the contemporary context, if such definitions have changed over time, and what role culture plays in definitions of masculinity. The idea of a single definition or construct which applies across time, cultures and place is difficult to establish; however, through the literature, a schema of traits commonly associated with “pervasive” or hegemonic masculinity was identified as providing a consistent definition to be applied to the selected texts.1

This project is significant as we posit that these portrayals send messages to youth about masculinity and gender roles, and thus, are important to understand, discuss, and, if necessary, combat. This interdisciplinary research bridges the library, education, and literature fields to examine the different ways maleness and masculinity are depicted to young adult readers in prize nominated and winning Australian young adult novels. The literature identified a need for greater understanding of the social, political and cultural contexts in which literature for youth is written and “the ways in which these texts shape how children view and interact with the social world.”2 Commentators such as Potter also note young adult literature has a “role in reflecting and refracting ideologies back into the culture in which they are read” and to “represent ways of behaving to the adolescent reader.”3

The development of a tool which can be used by educators and students in their analysis of texts can make a valuable contribution to discussions around gender norms and expectations. This addresses educators’ calls for disruptive approaches to “toxic masculinity” which is a harmful concept to society and to boys themselves.4 There have also been calls by scholars such as Bean and Harper for research which examines historic shifts occurring in realistic young adult literature novels in terms of masculinity.5 The current project addresses this gap in the research.

Conceptual Framework

A major question addressed by the authors prior to analysing the texts was how masculinity was to be defined and conceptualised and if there were common understandings or frameworks which could be applied by all researchers to the analysis. Through the literature review, the researchers explored changing definitions of masculinity and the complexities of applying historically accepted definitions of masculinity and gender roles to the 21st Century context. Characteristics were also considered as part of national identities with the consideration that some characteristics emerged from larger concepts about national identity. An example of this is the idea of “mateship” in the Australian national identity- reserved largely for definition of friendship, often in adversity between men- and considered part of the overarching definition of Australian masculinity. Exploring key concepts such as gender, masculinity and hegemony were critical to the research and led to the adoption of a critical framework and schemata developed by Romøren and Stephens’s in their comparative study on masculinity in Norwegian and Australian young adult fiction.6 These schemata called Hegemonic Masculinity Schema (HMS) and Sensitive New Man Schema (SNMS) frame masculinity in terms of hegemonic practices including domination, physical assertiveness and egocentric individualism and in contrast to each other.7 These definitions are derived from the work of Australian academic R.W. Connell. In Connell’s conceptualisation of hegemonic masculinity there is “a dynamic of dominance and subordination between groups of men” which also situates fiction and the construction of masculinity as part of global society and of complex institutional and community relationships.8

The focus of this study was on the portrayal of masculinity within the young adult novels, so they considered “novels, rather than authors” in their approach.9 This concept was applied to the current study which chose to focus on the novels rather than the authors in their selection. To conduct their research, Romøren and Stephens compiled young adult literature from Australia and Norway. Within the context of this study, concepts of masculinity and femininity are seen as changing, dynamic and relational. Drawing on Connell’s sociological methodologies and the use of life histories to explore “gendered lives,” Romøren and Stephens sought to explore these meta-narratives through the “constructed texts of fiction.”10 They believe that masculinity within the novel is created through a schema which then shapes the fictional characters and can be generalised from depictions in other popular media such as television and magazines. This current study employed hegemonic masculine attributes identified by Romøren and Stephens to examine the chosen novels, including to be self-regarding, a physical or verbal bully, and violent.11 This study also considered the concept of the Sensitive New Man through the Sensitive New Man Schema (SNMS) used by Romøren and Stephens to balance the attributes of hegemonic masculinity.

In working with normative definitions of masculinity and femininity, there is a lack of universal agreement on how these have led to contrasting stereotypical portrayals of masculinity. The Sensitive New Man is portrayed or represented in the media and fiction as “other” or in contrast to those characters representing or portraying hegemonic masculinity. Key characteristics used in this study of both hegemonic and Sensitive New Man masculinity are outlined in Table 2. Unpacking and defining key terminology and the shifting, dynamic definitions of masculinity were important considerations in the review of the literature.

Review of the literature

The mid-1990s saw increased attention shown to boys’ education, with a shift, according to Weaver-Hightower, from research in gender and education of girls to that of boys.12 Preparing for research on the representation of masculinity and gender in young adult literature requires a reading and defining of masculinity. According to Weaver-Hightower, “There is no single, universal, ahistorical version of masculinity to which all cultures subscribe or aspire. Rather, ideals of masculinity are historically and contextually dependent, making a nearly infinite number of masculinities possible.”13 Connell recognises that various types of masculinity exist within groups and communities.14 Not all of these can be defined, instead, a varying range exists. Some masculinities are dominant while others are considered inferior, or marginalised. Smiler studied ten types of stereotypical masculinities (Average Joe, Businessman, Family Man, Jock, Nerd, Player, Rebel, Sensitive New-Age Guy, Stud, Tough Guy) and the norms surrounding each of these.15 Communities, families and social groups create their own “versions of masculinity for their own uses within their own cultural frames.”16 Munsch and Gruys discuss orthodox and inclusive masculinity, with orthodox being present in a society where there is “widespread disapproval of homosexuality and femininity, and the need for men to publicly align with heterosexuality to avoid homosexual suspicion” and inclusive masculinity “characterized by emotional and physical intimacy and other behaviours historically associated with femininity and homosexuality.”17 Multiple masculinities also exist in societies without any hierarchy, where differences between masculinity and femininity do not exist and men adopt a range of behaviours without fear of reprisal or consequence. The most honoured or desirable type of masculinity in Western popular culture, according to Connell, is hegemonic masculinity which “is based on practice that permits men’s collective dominance over women to continue.”18 Hegemonic masculinity aligns with Munsch and Gruys definition of orthodox masculinity.19

While acknowledging that “there is no one pattern of masculinity found everywhere and that “we need to speak of ‘masculinities’, not masculinity,” this research focused on the portrayals of “hegemonic masculinity” and the “Sensitive New Man”, terms popularised and studied by Australian academic R.W. Connell20 and noted by other scholars of youth literature, particularly in the Australian context.21 Defined by “predominance,” the concept of hegemony can be applied across various contexts including class and gender.22 When speaking of hegemonic class structures, Connell and Irving describe it as “best thought of in terms of the institutional and cultural conditions of uninterrupted accumulation.”23 The concept of hegemonic masculinity is a complex one in relation to its portrayal in fiction and the media and emerging paradigms around gender and sexual identity. Overviews of critical concepts are provided through a broad definition in The Oxford Dictionary of Gender Studies in which hegemonic masculinity is described as being in juxtaposition to concepts of femininity and used “to explain the dynamic between women and men that supports men’s domination over women.”24 The Oxford Dictionary of Sociology defines the concept as “the configuration of gender practice that embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy—which guarantees (or is taken to guarantee) the dominant position of men and the subordination of women.”25 These definitions provide a broad overarching definition of the concepts framing this research.

On the other side of our studied masculinities sits the Sensitive New Man. The Sensitive New Man challenges stereotypes and power structures dictated by hegemonic masculinity and works in opposition to it as “other.” Connell’s study of six men fitting the label of Sensitive New Man were identified as pursuing equality in gender relations, having mostly female friendships, as able to fully express themselves emotionally, and being honest and caring people; they were also all heterosexual in contrast to the notion that the Sensitive New Man is homosexual.26

It has been argued that through the dominance of various media such as film and television, an understanding of a particular construction of hegemonic masculinity is disseminated and promoted and that fiction has a significant, if under researched, place in our understanding of the dominance of particular cultural practices. Romøren and Stephens argue that “fiction lays out a constructed view of experience, and requires as much attention to the processes of construction as to the represented content.”27 When exploring the depiction of Australian masculinity in particular, Potter describes it as a masculinity “which can be characterised by heterosexuality, a desire for mateship, a sense of responsibility or duty, actual or implicit misogyny, and an inability or unwillingness to express emotion and taciturnity.”28

Potter also argues that “Literature is of significant cultural importance in reaffirming or challenging cultural ideologies, including those of gender and masculinity.”29 This research aims to provide insight into this area of “significant cultural importance” through the analysis of masculinity in the selected young adult texts.

Methodology

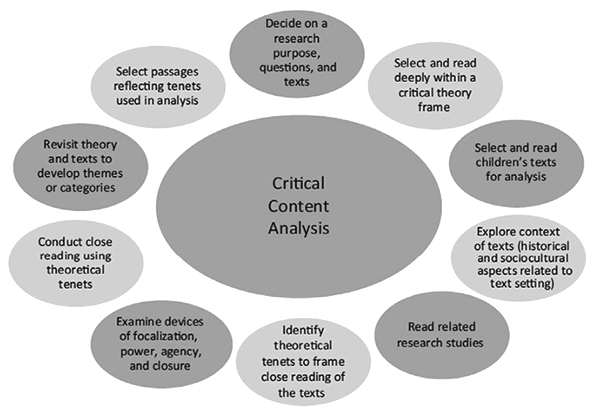

This study utilised a critical content analysis methodology, commonly used in analysing literature for youth to help researchers make methods and analytical processes more explicit.30 Beach et al. describes the methodology as combining content analysis (what the actual text is about from a particular perspective or framework) and literary analysis (what the authors are trying to say or do with the chosen literary conventions) with the critical piece coming in from the framework behind the analysis.31 Short notes “a definition of critical as a stance of locating power in social practices in order to challenge conditions of inequity.”32 In this study, our critical lens was masculinity and the power it afforded those who enacted it and those who did not. The steps in Figure 1 give specifics of critical content analysis as a methodology and are described in more detail in relation to this study in the subheadings below before the findings section.

Figure 1. Critical Content Analysis Methodology33

We began this methodology from the top of Figure 1, following the steps clockwise. First, as researchers and educators in youth literature and teacher education, we wanted to explore how masculinity was portrayed in Australian young adult literature and, thus, to young people reading these books.

Positionality statement. Short notes an important aspect of using critical content analysis is acknowledging the position a researcher brings to the process based on one’s own background and perspective.34 Recognising our own experiences and potential biases and how those may surface through our analyses and interpretations of our findings is a key part of this research. The authors of this study are all university educated, white, cisgender women with degrees in education and experience as educators across educational sectors and age groups. From mixed national backgrounds, two of the researchers were born in Australia and one in the United States. Two of the authors have adult male children and raised boys who were avid readers, influenced by a variety of media and their familial context. This parental perspective and extensive experience teaching young adults sparked an interest in the ways in which young adult fiction portrayed and could possibly influence the attitudes and perceptions of young adults. Considering our positionality, we read about masculine theory, different types of masculinity, and notable scholars in the field like R.W. Connell; thoughts surrounding this process are included in our literature review. Next, we needed to select the young adult texts.

Selecting the books. We chose the 2020 CBCA Book of the Year for Older Readers Notables List as those 20 award-winning titles are likely to be accessible and promoted to young adults whether that be in social media, public libraries, school libraries, book lists, or bookstores. The CBCA awards are Australia’s most prestigious literary awards for young people aged from birth to 18 years old. The CBCA was established in 1945 and the annual book awards began in 1946.35 The CBCA’s vision “creating a community that celebrates quality Australian literature for young people” is reflected in the national annual awards as they strive to promote and celebrate Australian children’s and young adult literature.36 For books to be eligible for the awards, they must be published in Australia the previous calendar year and created by an Australian citizen or a holder of Australian residency. A panel of three judges is appointed for each category and judging is based on literary merit. The six categories span fiction and non-fiction in all formats and include CBCA Book of the Year: Older Readers, Younger Readers, Early Childhood, CBCA Picture Book of the Year, the Eve Pownall Award for Information Books and CBCA Award for New Illustrator. The list of notable books in each category is announced in February, from which a shortlist of six is chosen and announced a month later. The winners and honours are announced during the annual Book Week held every August. (The announcements for 2020 were delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic and were made in May and October 2020.) This is an opportunity for the literature for Australia’s young people to shine and attracts attention worldwide. The lists of all categories are used for collection development in public and school libraries and provide a well-considered base for researchers. The CBCA Book of the Year: Older Readers category is for literature written for an audience aged from 13 to 18, stating readers will “require a degree of maturity to appreciate the themes and scope of emotional involvement.”37 The books in this category “can be described as having complex characters, they examine the thoughts and motivations of teens/characters to develop inner stories and subtexts.”38 Due to this criteria and the widespread collection and promotion of the books receiving attention from the CBCA, they made a quality pool of titles to use for this research.

To proceed with our method, we first divided the 20 books on the CBCA Book of the Year: Older Readers Notables List so that at least two researchers read each book. We created a table with basic characteristics of the books including age and gender of protagonists, setting, genre, and a summary. We also took notes and recorded specific quotes from the books that related to masculinity and gender issues. During these first readings, we met often to discuss what we were reading and the emerging themes of masculinity within the books. From these discussions, we decided to focus on three specific titles for a deeper analysis. These titles were selected because they had particularly interesting and illustrative instances of masculinity within the main and sub-characters, or in which “there was little doubt that masculinity was, in some way, an explicit theme.”39 Incidentally, these three books were also chosen for the CBCA Book of the Year: Older Readers Shortlist, Honour, and Winner announced in May and October. The three books were Four Dead Queens by Astrid Scholte (Shortlisted), The Boy who Steals Houses by C.G. Drews (Honour), and This is How We Change the Ending by Vikki Wakefield (Winner).40 Further information about the books is included in Table 1.

Table 1. Three Books Chosen for this Study

|

Title |

Author |

Genre |

Setting |

Selected Protagonist & Sub-character |

Summary |

|

Four Dead Queens |

Astrid Scholte |

Fantasy |

Kingdom of Quadara |

Keralie, female 17 y/o; Mackiel, male 19 y/o |

Pickpocket Keralie falls into a scheme concocted by her mentor Mackiel to murder the four ruling queens of Quadara, but has the chance to save them before it is too late. |

|

The Boy who Steals Houses |

C.G. Drews |

Contemporary Realism |

Melbourne |

Sammy, male 15 y/o; Moxie, female 15 y/o |

Homeless teen Sammy is running from the law as he tries to care for his autistic brother, often resulting to violence. Desperately searching for a home, he is accidentally adopted by Moxie’s large family. Through their care and love, Sammy realises he needs to face his violent past to have any kind of a future. |

|

This is How We Change the Ending |

Vikki Wakefield |

Contemporary Realism |

Australian city suburb |

Nate, male 16 y/o; Dec, father |

Living with his abusive father Dec, his father’s young partner Nance and their twin baby boys, Nate is looking for a way out of his bleak future. Through tense narrative, Nate discovers he must take control or his fear of becoming just like his father will eventuate. |

Coding for masculinity. In following the next steps in Figure 1, we searched for similar studies investigating masculinity and gender in young adult literature, particularly award-winning literature, while we read the titles and further into the theories. Then, we identified deeper, more specific tenets of the theories to inform closer readings of the books. These discussions resulted in identifying common themes of masculinity coming through the texts and research literature as well as a variety of different types of masculinities. While there were many others, we decided to focus on two relevant masculinity schemata: Hegemonic Masculinity Schema (HMS) and Sensitive New Man Schema (SNMS) as described by Romøren and Stephens41 as used in similar studies of young adult literature.42 Each of these schemata includes a range of attributes as shown in Table 2.

Romøren and Stephens note that only three to four of these attributes need to be present in a character to take on the whole schema in the mind of the reader (i.e., If a character is violent, short-tempered, and racist, the reader will think of that character as portraying the HMS.)43 The two schemata were considered in relation to and in contrast with each other. The schemata were not reserved for male characters only but applied to the selected characters regardless of sex or gender. In applying these schemata, we each read at least two of the three books again and focused on two characters from each book (the protagonist and a sub-character), taking notes and writing down quotes where the character exemplified attributes of the HMS and SNMS included in Table 2. We met weekly to discuss our emerging findings at this time across the three books and to check interrater reliability within the different attributes of HMS and SNMS for the six characters. During these close readings of the texts, we revisited the theoretical tenets described in our literature review in relation to masculinity and what other researchers have found in this space, specifically within literary analysis studies of youth literature. We identified passages and critical incidents in the texts exemplifying HMS and SNMS and describe them in detail in the findings.

Table 2. Attributes of HMS and SNMS44

|

Hegemonic Masculinity Schema (HMS) |

Sensitive New Man Schema (SNMS) |

|

to be self-regarding; a physical or verbal bully; overbearing in relation to women and children; (over)fond of alcohol; violent; short-tempered; neglectful of personal appearance; hostile to difference/otherness; actually or implicitly misogynistic; sexually exploitative; insistent upon differentiated gender roles and prone to impose these on others; classist; racist; generally xenophobic; sport-focused; insensitive; inattentive when others are speaking; aimless; and possessive. |

other-regarding in interpersonal relations; affectionate; well kempt, but unselfconscious about appearance; calm; self-possessed, but approachable; serious; polite; careful; attentive; supportive; considerate and respectful of the space and feelings of the (female) other; playful (as among equals); takes pleasure in female companionship; respects tum-taking in male-female conversations; artistic/ creative (but also practical); idealistic. |

Findings

The findings discussion includes an overview of the most noted attributes across the three books for the HMS and SNMS as well as more detailed focus on the six characters and their recorded attributes.

HMS attributes in the characters. The data in Table 3 give the total attributes found for each of the six characters for the HMS. More detailed data on the HMS attributes noted are included in Appendix A. As previously stated, only three to four of the attributes need to be present in a character to take on the whole schema in the mind of the reader.45 Researchers noted three or more examples of the nineteen HMS attributes for three of the six characters, two males and one female. Two antagonist characters displayed high instances of the attributes including twelve attributes for Dec, the father of protagonist Nate in This is How We Change the Ending, and eight attributes for Mackiel, the mentor and former best friend of protagonist Keralie in Four Dead Queens.

Table 3. HMS Totals for Each Character

|

|

Four Dead |

The Boy Who Steals Houses |

This is How We Change the Ending |

|||

|

Keralie |

Mackiel |

Sammy |

Moxie |

Nate |

Dec |

|

|

HMS (n= 19) |

3 |

8 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

12 |

In Four Dead Queens, both characters studied displayed enough HMS attributes to take on that schema. Protagonist Keralie was at times insensitive and violent, a physical and verbal bully to different characters in the story, including her boss Mackiel and the comm chip messenger Varin. From the very beginning of the story, the reader sees her taking advantage of others and working for Mackiel as a “dipper,” a pickpocketing thief. When she steals the comm chips with information on the Queens’ murders from Varin, she pretends to be a naive, innocent girl, but reflects to herself that “Hidden beneath my modest layers and pinching corsets, no one knew of my wickedness.”46 She sees herself as a bad person and enjoys it at times like when she stomps her shoe into a fellow dipper’s foot: “I revelled in the squelch as the spikes pierced through the leather and into his skin” and when she runs into a man on the street and steals his wallet: “The rotten part of me enjoyed the thwack as he hit the stones.”47 She shows enjoyment at the pain she instils on others; she thinks to herself after she pushes Mackiel into a lit incinerator: “I’d wanted destruction. So I lashed out. There was a fury in me I couldn’t control. A darkness attached, like a long shadow.”48 She showed this same darkness when she deliberately caused the boating accident which almost killed her father. Keralie is also insensitive throughout the story to Varin, never caring that her actions stealing the comm chip from his messenger bag could cost him not only his job, but also years on his life due to his sight ailment. Then, instead of being honest with him about wanting the life-saving medicine HIDRA for her father, she agrees to help him get it for himself, knowing she will end up betraying him when given the chance.

Mackiel shows a range of HMS attributes throughout the story as well. He is possessive of “his dippers”, especially Keralie, whom he constantly refers to as “his sweet Keralie” or “his darlin’ Keralie.” He shows similar possessiveness to the female character Arebella, who is the secret daughter of Queen Marguerite. Mackiel schemes with Arebella to take over the four queens’ thrones, convincing her to put him at her right hand when she succeeds. This also supports Mackiel’s misogynistic tendencies and overbearing attitude toward women as shown in the three submissive, feminine roles he suggests Keralie plays when she pickpockets Varin: “What do you feel like being today? A sweet young girl? A damsel in distress? A reluctant seductress?”49 He is insensitive and self-regarding, using other people, like the young dippers and his henchmen to get what he wants, which is to be rich and respected. He is violent and bullies others physically and verbally through his own actions and commands to his henchmen. Keralie reflects on his manipulative nature: “Mackiel took your weaknesses and twisted them for his gain,” and on his violence: “As a boy, he used to rescue rats from the Jetee sewers and now that was where he dumped the bodies of those who betrayed him.”50 His manipulation of Keralie and Arebella are clear in the minds of both girls as they often think of what Mackiel would tell them before they do something. Arebella uses Mackiel’s own words to help herself stay patient as she awaits her coronation and deals with the grief of her dead mother’s staff: “That’s it. Play upon his weakness. Mackiel’s voice was clear in her head.”51

In The Boy who Steals Houses, protagonist Sammy showed two attributes on the HMS, including many times in the violent and short-tempered attributes. Sammy’s violence is obvious early in the narrative as is his need to protect his brother Avery: “Sam spends his life hitting the world and smoothing over the rust corners so Avery won’t fall and hurt himself.”52 Sammy and Avery’s father Clay appears little in the story but the reader understands his nature: “His dad is a monster in the dark and Sammy will never be like him.”53 But Sammy is violent and this violence is repeated throughout the book. It is the only way he knows how to protect those he cares about; as Moxie states, “You lose it when someone else is getting hurt.”54 Moxie DeLainey is the oldest daughter of Reece DeLainey and the fourth of seven siblings. The children’s mother died a year ago and the family are still grieving her death while trying to get by. Moxie was included in the analysis and displayed two attributes in the HMS, including being short-tempered and insensitive.

The two main male characters in This is How We Change the Ending are Nate and his father Dec. Sixteen year-old Nate measures mostly within the SNMS, identifying with twelve of the sixteen attributes, while his father Dec shows mostly HMS, scoring 12 out of 19 attributes. Nate scored one on the HMS, that being violence, while Dec scored zero on the SNMS. Thirty-eight-year-old Dec is married to twenty-four-year-old Nance, his second wife and Nate’s step-mother. They have three-year-old twin sons, Otis and Jake. Otis has special needs causing a delay in his development and Jake is on trajectory to be a mini-Dec, constantly “crotch-grabbing” and swearing like his dad. The family is under Dec’s rule and they obey out of fear of retribution rather than respect. Nate reflects on this:

“I’ll make us something to eat,” Nance says. She swings her legs onto the floor, but he puts both hands around her waist to hand on. “Dec!” She slaps his forearm and pulls away. Otis slips sideways. He lands on his back, head in Dec's lap, and he starts bawling.

Jake springs to attention.

Nance leans down to pick him up, but Dec says, “Leave him. Let him work it out,” and she freezes. Jake does too, and it scares me that a three-year-old knows better.55

Dec’s need to be overbearing, and not just of women and children as seen here, is evident from the outset when the novel begins during a hunting trip when Nate was eleven years-old: “me, Dec, his mates Jarrod and Brett, one ute, two tents, three eskies, and a gun.”56 Dec is in charge, telling Nate to “pitch the tents and get a fire started while they sat on the back of the ute, drinking beer.” When Nate is not around, “they made Brett fetch the beers” and Dec and Jarrod bullied Brett when they “talked about him behind his back and laughed to his face. It made them feel big to make him feel small.” Nate learns early “the way to please my old man is to keep doing whatever he asked until he told me to stop.”57 The intensity of Dec’s overbearingness of anyone unlike himself, whether it be women, children, or men who do not show the hegemonic masculinity he strongly identifies with, is apparent as they begin hunting and come across a herd of wild goats. Stopping the vehicle, Nate stays inside with his eyes closed “I wouldn’t look. If I didn’t look, I wasn’t part of it.” Dec does not allow this:

The passenger door clicked. A rush of cold air and my eyes flew open.

“Man up.” Dec hissed, tugging my shorts.

“I can’t.”

“Come on. Quick.” I shook my head.

The ute heaved again. Brett came around to the side. “Might be better to let him take a rabbit his first time.”

“Did I ask you?” Dec said.

Brett drawled. “Come on, man-he’s a kid,” and gave me a crooked smile. I climbed out before Dec could wipe the smile off Brett’s face.58

Dec’s overbearing behaviour is repeated in several different ways throughout the novel, including locking his family out of their home on different occasions for different reasons. The first the reader knows of this is when Nate returns one night and finds Nance sitting on the verandah, “Her wide grey smiley eyes aren’t smiling. Her expression is so blank it’s scary.” His father had “locked her out again because that’s what he does when she won’t let up. He puts her out like a cat.”59

Dec exhibits other characteristics that align him with the HMS. He is overfond of alcohol, apparent from the first scene during the shooting trip when Nate counts the beers consumed: "I counted eight empty cans on the ground, but that was between three of them; I'd taken my eye off Dec so I wasn't sure where he was at. Three was okay. Five was borderline. Eight was dangerous.”60 Although he does not show instances of being classist, racist or xenophobic, he is insistent upon gender roles and imposes these strictly. Nance is the primary carer of the twins and performs all other domestic duties. When Nance injures her hand, Dec makes Nate take this role over: "Dec has been making me do all the things Nance can't do one-handed, which is basically everything, because Dec is the man of the house and the man doesn't do drone work."61

One trait in the HMS both Nate and Dec share is violence. Nate performs instances of violence towards his younger brother Jake as a form of discipline or to try and stop a behaviour, such as when he slaps Jake: “I reach behind me and slap Jake’s hand hard enough to shock him into letting me go.”62 This occurs on several occasions. On one other occasion, Nate surprises himself when he pushes his best friend Merrick: “I shove him, only I push him harder than I mean to and his feet get tangled up in his bag straps. He goes down hard and cracks his skull on the concrete.”63 Dec shows violence in other ways most of the time. According to Nate, Dec’s “rule is real men don’t hit women or children.”64 According to Connell however, “the hierarchy of masculinities is itself a source of violence, since force is used in defining and maintaining the hierarchy.”65 Dec may not always use physical violence, but he controls his household and his family. His language, in particular the use of the word “pussy” when trying to influence Nate to do something he does not want to, is according to Connell a “familiar way of training men and boys to participate in combat and violent sports,” in this case, smoking an illegal substance:66

“Leave him alone,” Nance says, “He doesn’t need it.”

“He wants it, though. Don’t you, mate?”

“No, thanks.’

“Pussy.’...

“I don’t smoke,” I say, looking at my feet. “You know that.”

“It’s a rite of passage. You need to chill the fuck out.”...

Dec’s watching me the way a cat watches a mortally wounded mouse. The shaking starts at my toes and builds; my knees are knocking together, my fingers are drumming on the counter, my teeth are chattering even though I’m not cold.67

Nate considers Dec’s rule of not hitting women and children will keep him safe from physical violence; however, Nate is sixteen and in Dec’s eyes, now a man.68 This threat becomes a reality when, after a series of events see all members of the family hit except for Otis, Dec advances on Nate:

For a big guy he moves fast. He shoots Otis a look of such intense hatred, it hurts like he's kicked me in the guts. He peels my fingers away from Jake's wrist and bends my hand so far back I have no choice but to kneel on a pile of dry cornflakes Jake spilt at breakfast. The instant agony makes my eyes water. With his free hand, Dec grabs my throat and digs his fingers into my Adam's apple. He forces my head back until my neck burns and I think I'll pass out, but Nance grabs his forearm and clubs the side of his face. Dec lets go and everything stops.69

SNMS attributes in the characters. The data in Table 4 give the total attributes found for each of the six characters for the SNMS. More detailed data on the SNMS attributes noted are included in Appendix B. Researchers note six or more examples of the sixteen SNMS attributes for four of the six youngest characters, two males and two females. The protagonists from the three books, Keralie, Sammy, and Nate, and sub-character Moxie showed high instances of the SNMS attributes from six to twelve total. These four characters are also much more “likeable” to the reader than the two main antagonist characters Dec and Mackiel, who showed high instances of the HMS attributes and only one SNMS attribute between the two of them.

Table 4. SNMS Totals for Each Character

|

|

Four Dead |

The Boy Who Steals Houses |

This is How We Change the Ending |

|||

|

Keralie |

Mackiel |

Sammy |

Moxie |

Nate |

Dec |

|

|

SNMS (n= 16) |

6 |

1 |

11 |

7 |

12 |

0 |

Keralie from Four Dead Queens is the only character in the novels to show three or more attributes of both schemata. The majority of her SNMS attributes show up later in the novel after she has already cemented her character with the HMS. Initially, when Keralie and Varin go to the castle to share information on the queens’ murders, Keralie’s main motivation is to get HIDRA for her father; this is a special medicine that would save his life. However, she also knows at this time that Varin wants HIDRA for his own malady. She makes him think she wants to help him get it, but by the end of the story, she has changed and actually does want to help him. She becomes other-regarding in interpersonal relationships and also develops an affectionate relationship with Varin. She becomes supportive to him and her father but also to the queens as she discovers they have not been murdered yet and genuinely wants to save them. This shows her consideration and respect for females as well. Keralie battles with this in her own mind as she is used to feeling a darkness and being a criminal: “Did I want to help the queens or not? Did I want to do the right thing? Was I more than a thief?”70

Nodelman’s assertion that qualities and behaviours previously accepted as being dependent on a boy’s testosterone, such as the adage “boys will be boys”, are changeable and are not dependent on biology are obvious in The Boy Who Steals Houses.71 As the novel progresses, Sammy evolves and becomes known to the reader as a sensitive young man, showing eight attributes in the SNMS. His other-regarding in interpersonal relationships, as exemplified by his protectiveness over his brother Avery, is prevalent from the start: "He's a mess, is Avery Lou, and Sam’s the only one who knows him, who cares.”72 This is also reflected as he gets to know the DeLainey family like his nervousness at staying at a party with Moxie; he stays because he knows Moxie wants to be there. Also, his affectionate nature becomes more apparent and he becomes more comfortable being close to others, physically and emotionally. This example shows growth with Moxie: “They fit together more comfortable this time, his arm not so awkwardly around her and her face nestled against his chest,” while this instance shows Sammy is letting his guard down with the father Reece: “Sam takes a deep breath and slowly, the last shred of his stamina failing away, he leans sideways until his head rests on Mr. DeLainey’s shoulder.”73 Prior to meeting this family, Sammy was scared to be around adults, but as the novel progresses and he gets to know Reece DeLainey, he lets go of this fear. Sammy is polite, calling Avery’s boss and Reece De Lainey “Sir.”74 He worries that he is not polite enough as in this example: “when he’s halfway through the explosion of flavours, he realises he didn’t even thank her because he’s so used to being silent. Seriously? He’s embarrassing.”75 He is attentive and supportive of Moxie and takes pleasure in her companionship as the novel progresses: “Sam turns out his pockets and discovers there are words in the bottom. They come out faster the more he’s around Moxie. And she doesn’t glare when he stammers or roll her eyes at his opinions.”76

After analysis Moxie showed seven attributes on the SNMS. She is affectionate and serious, “Instead she puts her arms around his neck - carefully, like she knows he's unravelling. And she hugs him" and attentive, as in this example after she laughs at Sammy’s reaction to a horror film, “‘I'm sorry.' Her voice is soft as sand and sea. 'I shouldn’t have laughed. Are you OK?'”77 She is artistic and creative, upcycling clothes with dreams of starting her own fashion label.

In This is How We Change the Ending, Nate shows 12 of the SNMS attributes, placing him on this trajectory to the reader.78 He is affectionate towards Nance and his brothers, and is calm and serious. When he is hit in the face with a ball during a physical education class at school, Nate remains calm even though he is knocked to the ground. Nate only reacts after the offender strikes him twice again with the ball and his best friend Merrick comes to assist him. Nate is serious and recognises this as being unlike his father: “I'm a worrier. Nance says it's weird considering I grew up with Dec for a dad, his mantra being 'no worries'.”79 He is polite, careful and attentive, picking up cigarette butts so his young brothers do not eat them and helping Nance when he can, even when it is not expected of him.80 He is considerate of Nance’s feelings and her situation with his father: “The last thing I want to do is make Nance cry.”81 He tries to make her life a little better: "Nance is the only one I can read to, but I have to be careful what I pick. If I choose right, she gets this look like I've taken her far away and she likes it there."82 He takes pleasure in female company and is respectful in turn-taking in conversations with females as shown through his relationship with Nance and females at the Youth Centre where he goes almost nightly to escape his homelife. Nate is also very creative; he fills up notebooks, constantly writing down his thoughts: “Mostly they're just random scenes, fragments of sentences or long letters to nobody. Ideas that probably wouldn't make sense to anyone but me.”83

Discussion

Developing from HMS to SNMS. “Coming of age” is a common theme in young adult literature but a bigger issue for the protagonists in all three books studied in this research was overcoming the circumstances they were born into (often related to attributes of the HMS) and transforming into someone different, exemplifying SNMS attributes. This idea is illustrated by the title of Nate’s book: This is How We Change the Ending. Protagonists Sammy and Keralie both had high levels of HMS attributes in the beginning of their stories. Sammy was violent and short-tempered, mostly to protect his brother Avery. Keralie was also violent, a physical and verbal bully insensitive to the needs of others including her parents and Varin. But as their stories progressed, they showed attributes of the SNMS and began to develop and grow into better people. They gave affection and support to other characters and became more empathic to the needs of others.

Influence of the father. The influence of the father emerged as an important contributor to HMS attributes of the three young male characters studied including Sammy, Nate, and Mackiel. As previously noted, Dec, the father of Nate, was also included in our analysis and showed 12 out of the total 19 HMS attributes, the most of any character. Sammy’s father Clay is described in a similar way to Dec, particular with the use of violence on his sons. Sammy credits him with his own violent tendencies as growing up, it was the only way to protect himself and Avery. Both Sammy’s mother and Nate’s mother left them with their fathers and play small parts in the books. Dec stays around for Nate, claiming he’s “done ten times better than [his own] old man,” a comment that alludes to another father showing HMS attributes like violence and bullying.84 Clay ends up giving Sammy and his brother Avery to their mother’s sister, Aunt Karen, who also uses physical and verbal abuse against the boys. While Sammy and Nate feared becoming like their violent fathers, Mackiel wanted to be just like his and took over the family crime business, auctioning off stolen goods, when his father died. Keralie reflects on this in thinking about Mackiel’s “meagre” appearance being “a fragment of his father, of who he wanted to be.”85 She notes that Mackiel “spent too many years pretending to be ruthless, too many years trying to impress his father with darker and darker deeds, desperate to earn his attention, his love.”86 Interestingly enough, the only time Mackiel showed an SNMS attribute was in response to the grief he felt for his father’s death. Romøren and Stephens also found the influence of the father on HMS attributes in the sons a consistent theme in their study of Norwegian and Australian young adult fiction.87

The fathers of the two female characters studied, Keralie and Moxie, are good counter examples to the fathers of the male characters. Keralie spends the early parts of the book hiding her guilt and grief for causing the boating accident which put her father into a coma with just weeks to live. As the book progresses, Keralie decides she can not only save her father by saving the queens, but also make him and her mother proud of her. In the last page of the book, they are finally reunited: “When my father broke into a smile and opened his arms- ready to embrace me- my heart restitched inside my chest.”88 While similar to Dec and Clay in that his wife is also absent having lost her battle with cancer, Moxie’s father Reece is the complete opposite as a parent. He is affectionate to and supportive of his seven children and even welcomes Sammy and Avery into his home by the end of the story despite Sammy stealing from him and breaking into his home: “he holds Sam like he knows how to keep boys who are slipping.”89

Further research

This study brought up further areas for research in this set of books regarding masculinity. Firstly, we chose only three exemplary novels from the 2020 CBCA Book of the Year for Older Readers Notables List so further research could investigate some of the other seventeen novels included on the list. For example, Invisible Boys tackles this topic widely and we plan to examine that title much more closely in our future study of this set of books.90 Also, as Connell notes, “there is no one pattern of masculinity that is found everywhere. We need to speak of ‘masculinities’, not masculinity. Different cultures, and different periods of history, construct gender differently.”91 Thus, future research should examine other forms of masculinity and not just the two schemata studied here. It is also notable that the three books chosen for this study were written by authors who identify as females. While the researchers did not make a deliberate choice to study masculinity in books written by women, it is still an interesting outcome and warrants further study. Further research should also involve the voice of young readers and examine how they respond to these books using these lenses.

Conceptual framework for future research. As a result of this study, the researchers saw a need to modify the HMS and SNMS as originally described by Romøren and Stephens.92 Our main goal in these changes was to streamline the analytical approach through these modified schemata of attributes as shown in Table 5. A clear focus on the modified schemata is a more nuanced approach to diversity and equity perspectives used in contemporary society. These elements are not limited to gender, but include wider sociocultural constructs related to race, ability, nationality, and the LGBTQIA community which may also reflect an emerging conception of hegemonic masculinity.

Emerging from this research is the need to re-evaluate the norms that have been applied to research investigating hegemonic masculinity. This includes considering a more nuanced consideration and description of gender identity in young adult fiction and developing an extended range of language in line with contemporary society. We also invite other researchers in this area to explore young adult literature using the modified schemata and even devise a new name for the MSNMS. We note that perspectives and research into gender issues and masculinity are fluid, changing and updating to reflect current trends and contemporary issues, so it may be possible to develop a more appropriate, comprehensive term to Sensitive New Man.

Table 5. Modified Masculinity Schemata

|

Modified Hegemonic Masculinity Schema (MHMS) |

Modified Sensitive New Man Schema (MSNMS) |

|

• Self-regarding and/or narcissistic; • Physical and/or verbal bully; • Violent and/or aggressive; • Short-tempered and/or reactive; • Sexually exploitative; • Hostile and/or controlling in relation to difference/otherness, including women, children and characters with different racial, gender, sexual and/or other sociocultural identities; • Displays misogynistic behaviours and/or attitudes; • Insistent upon differentiated and traditional gender roles and judgmental of those who do not conform. |

• Other-regarding and/or empathetic; • Affectionate and/or shows emotion; • Approachable; • Supportive; • Equity-minded; • Considerate and/or respectful of difference/otherness, including women, children and characters with different racial, gender, sexual and/or other sociocultural identities; • Enjoys the company of others including women, children and characters with different racial, gender, sexual, and/or other sociocultural identities; • Not confined or restricted by traditional gender role definitions. |

Conclusions

Short advocates for “a critical lens” in studying literature for youth which “moves from deconstruction to reconstruction and then to action.”93 Studying how masculinity is represented in young adult novels popularised and promoted through literary awards such as the CBCA Books of the Year Awards in Australia is important for many factors. It is important to analyse how masculinity is represented to young people through their literature so that we have some idea of how this may influence their thought processes and opinions of what it means to be masculine and a man. Bean and Ranshaw note the devastating effects hegemonic masculinity can have on at-risk populations of young males unable to rectify norms.94 There is a growing body of young adult literature like the titles studied here challenging these norms and engaging youth to consider what it means to be male and how they can explore their own complex identities using the books.95 With continual incidents of domestic violence and increasing links to toxic masculinity, it is critical to bring these issues into the open with our young people and those who work with them like educators, counsellors and administrators.96 Young characters such as Keralie, Sammy, Moxie, and Nate offer unique perspectives for discussion, illustrating to readers that there are many forms of masculinity and answering the call to “action” noted by Short.97

Academic References

1. BEACH, Richard; ENCISO, Patricia; HARSTE, Jerome; JENKINS, Christine; RAINA, Seemi Aziz; ROGERS, Rebecca; SHORT, Kathy G.; SUNG, Yoo Kyung; WILSON, Melissa; YENIKA-AGBAW, Vivian. Exploring the “Critical” in Critical Content Analysis of Children’s Literature. National Reading Conference Yearbook, 2009, vol. 58, p. 129–143.

2. BEAN, Thomas W.; HARPER, Helen. Reading Men Differently: Alternative Portrayals of Masculinity in Contemporary Young Adult Fiction. Reading Psychology, vol. 28, no.1, p. 11–30.

3. BEAN, Thomas W.; RANSHAW. Masculinity and Portrayals of African American Boys in Young Adult Literature: A Critical Deconstruction and Reconstruction of the Genre. In GUZZETTI, Barbara J.; BEAN, Thomas. In Adolescent Literacies and the Gendered Self: (Re)constructing Identities Through Multimodal Literacy Practices, Taylor & Francis Group, 2012, p. 22–30.

4. CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA. About the Children’s Book Council of Australia. [accessed 21 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://cbca.org.au/about>.

5. CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA. Entry Information for Publishers and Creators. [accessed 21 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://www.cbca.org.au/entry-information>.

6. CLEMENS, Colleen. Toxic Masculinity Is Bad for Everyone: Why Teachers Must Disrupt Gender Norms Every Day. Teaching Tolerance, 2018. [accessed 23 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/toxic-masculinity-is-bad-for-everyone-why-teachers-must-disrupt-gender-norms-every-day>.

7. CONNELL, R.W. Gender and Power: Society, the Person, and Sexual Politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1987, 334 p. ISBN 0804714290.

8. CONNELL, R.W. The Men and the Boys. St. Leonards, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2000. 259 p. ISBN 1865084166.

9. CONNELL, R.W. Masculinities. 2nd. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005, 324 p. ISBN 0745634265.

10. CONNELL, R.W.; IRVING, Terence H. Class Structure in Australian History: Poverty and Progress. Melbourne: Longham Cheshire, 1992. 525 p. ISBN 9780582711907.

11. CONNELL, R.W.; MESSERSCHMIDT, James. Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 2005, vol. 19, no. 6, p. 829–859.

12. GRIFFIN, Gabriele. A Dictionary of Gender Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. [accessed 29 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191834837.001.0001/acref-9780191834837>.

13. GUANIO-ULURU, Lykke. Female Focalizers and Masculine Ideals: Gender as Performance in Twlight and the Hunger Games. Children’s Literature in Education, 2016, vol. 47, p. 209–224.

14. INGGS, Judith. Transgressing Boundaries? Romance, Power, and Sexuality in Contemporary South African English Young Adult Fiction. International Research in Children’s Literature, 2009, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 101-114.

15. MUNSCH, Christin L.; GRUYS, Kjerstin. What Threatens, Defines: Tracing the Symbolic Boundaries of Contemporary Masculinity. Sex Roles, 2018, vol. 79, p. 375–392.

16. NODELMAN, Perry. Making Boys Appear: The Masculinity of Children’s Fiction. In STEPHENS, John; STEPHENS, John A. (ed.). In Ways of Being Male: Representing Masculinities in Children’s Literature. Taylor & Francis Group, 2002, p. 1–14.

17. POTTER, Troy. (Re)constructing Masculinity: Representations of Men and Masculinity in Australian Young Adult Literature. Papers, 2007, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 28–35.

18. ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities in Norwegian and Australian Young Adult Fiction: A Comparative Study. In STEPHENS, John; STEPHENS, John A. (ed.). In Ways of Being Male: Representing Masculinities in Children’s Literature. Taylor & Francis Group, 2002, p. 216–233.

19. SCOTT, John. A Dictionary of Sociology. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. [accessed 29 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199683581.001.0001/acref-9780199683581-e-992>.

20. SHORT, Kathy G. Critical Content Analysis as a Research Methodology. In JOHNSON, Holly; MATHIS, Janelle; SHORT, Kathy G. (ed.). Critical Content Analysis of Children’s and Young Adult Literature. New York: Routledge, 2016, p. 3–22. ISBN 9781315651927.

21. SHORT, Kathy G. Critical Content Analysis of Visual Images. In JOHNSON, Holly; MATHIS, Janelle; SHORT, Kathy G. (ed.). Critical Content Analysis of Visual Images in Books for Young People. New York: Routledge, 2019, p. 1-15. ISBN 9781138387065.

22. SMILER, Andrew P. Living the Image: A Quantitative Approach to Delineating Masculinities. Sex Roles, 2006, vol. 55, p. 621.-632.

23. STEPHENS, John. Editor’s Introduction: Always Facing the Issues – Preoccupations in Australian Children’s Literature. The Lion and the Unicorn, 2003, vol. 27, no. 2, v–xvii.

24. WEAVER-HIGHTOWER, Marcus. The “Boy-Turn” in Research on Gender and Education. Review of Educational Research, 2003, vol. 73, no. 4, p. 471-498.

Young Adult Literature References

1. BURTON, David. The Man in the Water. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2019. 256 p. ISBN 9780702262524.

2. CADDY, Meg. Devil’s Ballast. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2019. 288 p. ISBN 9781925773460.

3. CHIM, Wai. The Surprising Power of a Good Dumpling. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2019. 400 p. ISBN 9781760631581.

4. *DREWS, C.G. The Boy Who Steals Houses. Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2019. 258 p. ISBN 9781408349939.

5. DUGGAN, Cait. The Last Balfour. Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers, 2019. 288 p. ISBN 9781460757017.

6. FOX, Helena. How It Feels to Float. Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia, 2019. 384 p. ISBN 9781760783303.

7. FULLER, Lisa. Ghost Bird. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2019. 288 p. ISBN 9780702260230.

8. GRANT, Neil. The Honeyman and the Hunter. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2019. 288 p. ISBN 9781760631871.

9. KAUFMAN, Amie, & KRISTOFF, Jay. Aurora Rising. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2019. 496 p. ISBN 9781760295738.

10. KENWOOD, Nina. It Sounded Better in My Head. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2019. 288 p. ISBN 9781925773910.

11. KOSTAKIS, Will. Monuments. Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2019. 288 p. ISBN 9780734419224.

12. MORGAN, Anna. All That Impossible Space. Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2019. 280 p. ISBN 9780734419637.

13. NEWTON, Robert. Promise Me Happy. Sydney: Penguin Random House Australia, 2019. 288 p. ISBN 9780143796442.

14. NIX, Garth. Angel Mage. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2019. 496 p. ISBN 9781760630904.

15. NUNN, Malla. When the Ground is Hard. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2019. 272 p. ISBN 9781760524814.

16. *SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2019. 432 p. ISBN 9781760524418.

17. SHEPPARD, Holden. Invisible Boys. Fremantle: Fremantle Press, 2019. 337 p. ISBN 9781925815566.

18. *WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How We Change the Ending. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2019. 322 p. ISBN 9781922268136.

19. WHITE, Susan. Take the Shot. Melbourne: Affirm Press, 2019. 320 p. ISBN 9781925712957.

20. WILLIAMS, Sean. Impossible Music. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2019. 320 p. ISBN 9781760637156.

* Denotes three titles chosen for the study

Appendix A. HMS Attributes Across the Sample

|

HMS |

Four Dead |

The Boy Who Steals |

This is How We Change the Ending |

HMS |

|||

|

Keralie |

Mackiel |

Sammy |

Moxie |

Nate |

Dec |

||

|

Self-regarding |

|

|

|

|

|

✔ |

2 |

|

Physical or verbal bully |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

3 |

|

Overbearing in relation to women and children |

|

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

2 |

|

(over) fond of alcohol |

|

|

|

|

|

✔ |

1 |

|

Violent |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

✔ |

5 |

|

Short-tempered |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

3 |

|

Neglectful of personal appearance |

|

|

|

|

|

✔ |

1 |

|

Hostile to difference or otherness |

|

|

|

|

|

✔ |

1 |

|

Actually or implicitly misogynistic |

|

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

2 |

|

Sexually exploitative |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

Insistent upon differentiated gender roles and prone to impose these on others |

|

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

2 |

|

Classist |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

Racist |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

Generally xenophobic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

Sport-focused |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

Insensitive |

✔ |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

✔ |

4 |

|

Inattentive when others are speaking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

Aimless |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

Possessive |

|

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

2 |

|

HMS Character Totals |

3 |

8 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

12 |

|

Appendix B. SNMS Attributes Across the Sample

|

SNMS |

Four Dead |

The Boy Who Steals |

This is How We |

SNMS |

|||

|

Keralie |

Mackiel |

Sammy |

Moxie |

Nate |

Dec |

||

|

other-regarding in interpersonal relations; |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

|

4 |

|

affectionate |

✔ |

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

4 |

|

well kempt, but unselfconscious about appearance; |

✔ |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

calm |

|

|

|

|

✔ |

|

1 |

|

self-possessed, but approachable |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

serious |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

3 |

|

polite |

|

|

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

2 |

|

careful |

|

|

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

2 |

|

attentive |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

3 |

|

supportive |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

3 |

|

considerate and respectful of the space and feelings of the (female) other; |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

3 |

|

playful (as among equals); |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

takes pleasure in female companionship; |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

3 |

|

respects turn -taking in male-female conversations; |

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

3 |

|

artistic/ creative (but also practical); |

|

|

|

✔ |

✔ |

|

2 |

|

idealistic |

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

✔ |

|

3 |

|

SNMS Character Totals |

6 |

1 |

11 |

7 |

12 |

0 |

|

1 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities in Norwegian and Australian Young Adult Fiction: A Comparative Study. In STEPHENS, John; STEPHENS, John A. (ed.). In Ways of Being Male: Representing Masculinities in Children’s Literature. Taylor & Francis Group, 2002, p. 216–233.

2 BEACH, Richard; ENCISO, Patricia; HARSTE, Jerome; JENKINS, Christine; RAINA, Seemi Aziz; ROGERS, Rebecca; SHORT, Kathy G.; SUNG, Yoo Kyung; WILSON, Melissa; YENIKA-AGBAW, Vivian. Exploring the “Critical” in Critical Content Analysis of Children’s Literature. National Reading Conference Yearbook, 2009, vol. 58, p. 129–143.

3 POTTER, Troy. (Re)constructing Masculinity: Representations of Men and Masculinity in Australian Young Adult Literature. Papers, 2007, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 28.

4 CLEMENS, Colleen. Toxic Masculinity Is Bad for Everyone: Why Teachers Must Disrupt Gender Norms Every Day. Teaching Tolerance, 2018. [accessed 23 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/toxic-masculinity-is-bad-for-everyone-why-teachers-must-disrupt-gender-norms-every-day>.

5 BEAN, Thomas W.; HARPER, Helen. Reading Men Differently: Alternative Portrayals of Masculinity in Contemporary Young Adult Fiction. Reading Psychology, vol. 28, no. 1, p. 11–30.

6 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 220 & 225.

7 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 217.

8 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 216.

9 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 217.

10 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 218.

11 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 220 & 225.

12 WEAVER-HIGHTOWER, Marcus. The “Boy-Turn” in Research on Gender and Education. Review of Educational Research, 2003, vol. 73, no. 4, p. 472.

13 WEAVER-HIGHTOWER, Marcus. The “Boy-Turn” …, p. 479.

14 CONNELL, R.W. The Men and the Boys. St. Leonards, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2000, p. 10.

15 SMILER, Andrew P. Living the Image: A Quantitative Approach to Delineating Masculinities. Sex Roles, 2006, vol. 55, p. 621.

16 WEAVER-HIGHTOWER, Marcus. The “Boy-Turn” …, p. 479.

17 MUNSCH, Christin L.; GRUYS, Kjerstin. What Threatens, Defines: Tracing the Symbolic Boundaries of Contemporary Masculinity. Sex Roles, 2018, vol. 79, p. 376.

18 CONNELL, R.W.; MESSERSCHMIDT, James. Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 2005, vol. 19, no. 6, p. 840.

19 MUNSCH, Christin L.; GRUYS, Kjerstin. What Threatens…, p. 376.

20 CONNELL, R.W. Gender and Power: Society, the Person, and Sexual Politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1987, 334 p. ISBN 0804714290; CONNELL, R.W. Masculinities. 2nd. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005, 136 p. ISBN 0745634265; CONNELL, R.W. The Men…, p. 10.

21 GUANIO-ULURU, Lykke. Female Focalizers and Masculine Ideals: Gender as Performance in Twilight and the Hunger Games. Children’s Literature in Education. 2016, vol. 47, p. 212-215, 220-223; INGGS, Judith. Transgressing Boundaries? Romance, Power, and Sexuality in Contemporary South African English Young Adult Fiction. International Research in Children’s Literature. 2009, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 103; STEPHENS, John. Editor’s Introduction: Always Facing the Issues—Preoccupations in Australian Children’s Literature. The Lion and the Unicorn. 2003, vol. 27, no. 2, v–xvii.

22 GRIFFIN, Gabriele. A Dictionary of Gender Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. [accessed 29 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191834837.001.0001/acref-9780191834837>.

23 CONNELL, R.W.; IRVING, Terence H. Class Structure in Australian History: Poverty and Progress. Melbourne: Longham Cheshire, 1992, p. 19.

24 Griffin, G. A Dictionary of Gender Studies. 1 ed. ed. Oxford University Press; 2017. Accessed through https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/view/10.1093/acref/9780191834837.001.0001/acref-9780191834837. [Accessed , 29 December 2020)

25 SCOTT, John. A Dictionary of Sociology. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. [accessed 29 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199683581.001.0001/acref-9780199683581-e-992>.

26 SMILER, Andrew P. Living the Image…, p. 626.

27 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 219.

28 POTTER, Troy. (Re)constructing…, p. 28.

29 POTTER, Troy. (Re)constructing…, p. 28.

30 BEACH, Richard; ENCISO, Patricia; HARSTE, Jerome; JENKINS, Christine; RAINA, Seemi Aziz; ROGERS, Rebecca; SHORT, Kathy G.; SUNG, Yoo Kyung; WILSON, Melissa; YENIKA-AGBAW, Vivian. Exploring…, p. 129; SHORT, Kathy G. Critical Content Analysis as a Research Methodology. In JOHNSON, Holly; MATHIS, Janelle; SHORT, Kathy G. (ed.). Critical Content Analysis of Children’s and Young Adult Literature. New York: Routledge, 2016, p. 3–22. ISBN 9781315651927; SHORT, Kathy G. Critical Content Analysis of Visual Images. In JOHNSON, Holly; MATHIS, Janelle; SHORT, Kathy G. (ed.). Critical Content Analysis of Visual Images in Books for Young People. New York: Routledge, 2019, p. 1–15. ISBN 9781138387065.

31 BEACH, Richard; ENCISO, Patricia; HARSTE, Jerome; JENKINS, Christine; RAINA, Seemi Aziz; ROGERS, Rebecca; SHORT, Kathy G.; SUNG, Yoo Kyung; WILSON, Melissa; YENIKA-AGBAW, Vivian. Exploring…, p. 130;

32 SHORT, Kathy G. Research Methodology…, p. 1.

33 SHORT, Kathy G. Research Methodology…, p. 7.

34 SHORT, Kathy G. Visual Images…, p. 15–16

35 CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA. About the Children’s Book Council of Australia, para. 2. [accessed 21 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://cbca.org.au/about>.

36 Children’s Book Council of Australia. About…, para. 5.

37 CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA. Entry Information for Publishers and Creators, para 10. [accessed 21 December 2020]. Access through Internet: <https://www.cbca.org.au/entry-information>.

38 Children’s Book Council of Australia. Entry Information …, para. 3.

39 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 217.

40 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2019. 432 p. ISBN 9781760524418; DREWS, C.G. The Boy Who Steals Houses. Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2019. 258 p. ISBN 9781408349939; WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How We Change the Ending. Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2019. 322 p. ISBN 9781922268136.

41 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 220 & 225.

42 GUANIO-ULURU, Lykke. Female Focalizers…p. 212; INGGS, Judith. Transgressing Boundaries…p. 103.

43 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 220.

44 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 220 & 225.

45 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 220.

46 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 6.

47 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 32; 7.

48 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 222.

49 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 3.

50 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 33; 34.

51 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 379.

52 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 4-5.

53 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 61.

54 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 341.

55 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 27.

56 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 1.

57 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 2.

58 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 5-6.

59 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 15.

60 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 3.

61 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 74.

62 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 85.

63 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 61.

64 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 189.

65 CONNELL, R.W. The Men…, p. 217.

66 CONNELL, R.W. The Men…, p. 217.

67 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 72.

68 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 189.

69 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 264.

70 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 224.

71 NODELMAN, Perry. Making Boys…, p. 2.

72 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 18.

73 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 252; 338.

74 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 90; 80.

75 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 70.

76 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 213.

77 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 340; 79.

78 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 225.

79 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 19.

80 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 66.

81 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 17.

82 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 16.

83 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 14.

84 WAKEFIELD, Vikki. This is How…, p. 169.

85 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 51.

86 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 108.

87 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 222.

88 SCHOLTE, Astrid. Four Dead Queens, p. 418.

89 DREWS, C.G. The Boy…, p. 338.

90 SHEPPARD, Holden. Invisible Boys. Fremantle: Fremantle Press, 2019. 337 p. ISBN 9781925815566.

91 CONNELL, R.W. The Men…, p. 10.

92 ROMØREN, Rolf; STEPHENS, John. Representing Masculinities…, p. 220–225.

93 SHORT, Kathy G. Research Methodology…, p. 6.

94 BEAN, Thomas W.; RANSHAW, Theodore. Masculinity and Portrayals of African American Boys in Young Adult Literature: A Critical Deconstruction and Reconstruction of the Genre. In GUZZETTI, Barbara J.; BEAN, Thomas. In Adolescent Literacies and the Gendered Self : (Re)constructing Identities Through Multimodal Literacy Practices, Taylor & Francis Group, 2012, p. 27.

95 BEAN, Thomas W.; RANSHAW, Theodore. Masculinity and Portrayals…, p. 27.

96 CLEMENS, Colleen. Toxic Masculinity…, para. 2.

97 SHORT, Kathy G. Research Methodology…, p. 6.