Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2021, vol. 76, pp. 260–293 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2021.76.83

Roles of Local Information Professionals of the Thai Provincial University Libraries

Pussadee Nonthacumjane

Swedish School of Library and Information Science,

University of Borås, S-501 90, Borås, Sweden

E-mail: Pussadee.nonthacumjane@hb.se

Summary. This paper aims to investigate the roles of information professionals in local information departments. These roles were identified by interviewing the members of the Local Information Working Group of the Provincial University Library Network (PULINET) in Thailand. This study applied qualitative research methods, including the 23 interviews of the Local Information Working Group members and a qualitative observation. The need for investigation of the roles as perceived by local information professionals was prompted by the placement of local information departments in the provincial university libraries, which is different from the Western countries where similar work is carried out in public libraries. The activity theory was applied to understand the roles of these professionals as emerging within their community through the division of labor, norms as expressed in responsibilities, and actions as expressed in functions of local information professionals. The study has revealed eight professional roles including manager, curator, service provider, promoter, researcher, collaborator, learner, and educator that overlap with the roles identified in the library research of other countries. The study included a specific group of respondents – the members of a working group of the Thai provincial university library network. This group consists of the representatives of all Thai provincial university libraries and is producing the recommendations and standards for local information work, works with competence development and develops common local information resources. Thus, the results of interviews with its members are both limited to this group, but also can be generalized to a wider professional community of provincial university librarians.

Keywords: information professionals, local information departments, Local Information Working Group, Provincial University Library Network, Thailand.

Kraštotyros informacijos specialistų vaidmuo Tailando provincijų universitetų bibliotekose

Santrauka. Šiuo straipsniu siekiama atskleisti Tailando universitetų bibliotekų kraštotyros informacijos skyriuose dirbančių informacijos specialistų vaidmenis. Tyrimo respondentai buvo Tailando provincijų universitetų bibliotekų tinklo (PULINET) Kraštotyros informacijos darbo grupės nariai. Šiame tyrime buvo taikomi kokybiniai tyrimo metodai: interviu su 23 Kraštotyros informacijos darbo grupės nariais ir kokybinis stebėjimas. Poreikį ištirti, kaip kraštotyros informacijos specialistai suvokia profesinius vaidmenis, paskatino kraštotyros skyrių įkūrimas provincijos universitetų bibliotekose, o tai skiriasi nuo Vakarų šalių, kuriose panašus darbas atliekamas viešosiose bibliotekose. Veiklos teorija buvo naudojama siekiant suprasti šių specialistų vaidmenis, atsirandančius profesinėje bendruomenėje iš darbo pasidalijimo, nustatytų profesinės atsakomybės normų ir kraštotyros informacijos specialistų funkcijose numatytų veiksmų. Tyrimas atskleidė, kad aštuoni vaidmenys (vadybininko, kuratoriaus, paslaugų teikėjo, projektų rengėjo, tyrėjo, bendradarbio, praktikanto ir ugdytojo) buvo priskirti informacijos specialistams, dirbantiems Tailando provincijų universitetų bibliotekų kraštotyros informacijos skyriuose. Šis rezultatas iš dalies sutampa su kitose šalyse atliktų bibliotekininkystės studijų rezultatais. Tyrimas atliktas su Tailando provincijų universitetų bibliotekų tinklo Kraštotyros informacijos darbo grupės nariais. Šią grupę sudaro visų Tailando provincijos universitetų bibliotekų atstovai. Ji rengia kraštotyros darbo šiose bibliotekose rekomendacijas ir standartus, rūpinasi kompetencijos tobulinimu ir kuria bendrus kraštotyros informacijos išteklius. Todėl, viena vertus, tyrimo rezultatus riboja respondentų priklausomybė šiai grupei, kita vertus, juos galima apibendrinti platesnei kraštotyros informacijos specialistų bendruomenei provincijos universitetų bibliotekose.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: informacijos specialistai, kraštotyros informacijos skyriai, Kraštotyros informacijos darbo grupė, Provincijų universitetų bibliotekų tinklas, Tailandas.

Received: 2021 02 26. Accepted: 2021 04 23

Copyright © 2021 Pussadee Nonthacumjane. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The concept of local information is akin to the concepts of local history, local studies and community information or indigenous knowledge and even genealogy. It is related to the heritage and way of life of a community living in a particular territory. Different countries have different traditions in organising local information work and they can be a subject matter of other publications. In this article, the understanding or the roles of local information professionals in Thailand provincial university libraries will be explored.

There are several reasons to explore this issue from the Thai local information professionals perspective. First of all, local information work is a politically important task1 carried out by the provincial university libraries, which is quite different from the Western countries where this work as a rule is a responsibility of public libraries, archives and museums, which are close to their local communities2. The context of the university library, where the needs of students, lecturers and researchers are the principal concern of the library, may affect the local information professionals having their first responsibility to the local community residing in certain geographical locations.

In addition, technology development has also made an impact on the local information departments: as users change the ways they access local information resources, library staff need to adjust the ways in which they manage and deliver services. The development of information and communication technology has expanded in Thailand in recent years, as shown by increased internet usage in Thailand. Statistics have shown that the use of the internet by Thai people is rising each year: in 2014, 27.6 million people, in 2015, 39.4 million people, in 2016, 43.8 million people used the internet3. This increase has consequences for information seeking. These phenomena also impact significantly the understanding of local information as well as the roles of information professionals working in the local information departments. Beyond this, local information is critical for ancestry studies, local history and community and vital to the integrity of every local library. As the reports of the libraries and articles show, throughout the years the local information departments of the provincial university libraries (the Network members) increasingly apply information technology in their work4.

The information professionals of local information departments must constantly update not only their technology skills, but their understanding of library work, society, and a new generation of users. They have to combine their traditional roles with the handling of fast changing technology and new methods of professional work. Furthermore, the study of the local information professionals’ work area is very rare and not up to date. A preliminary literature review has revealed that most studies have focused on identifying roles of Thai information professionals in general5. Only one survey, conducted by Derdkhuntod6, has explored the numbers and opinions of library staff, working in the local information centres of twelve provincial university libraries, and the qualification requirements in these library departments. Thus, a study of the members of the local information professionals in order to explore the roles of the Thai local information professionals, seemed to be justified and closing an important gap in Thai library and information science research. In addition, this mix of a specific Thai context closely related to the direct tasks of local information departments and globally recognized developments in information profession can provide useful insights for the understanding of similar developments in other countries, especially with heterogeneous ethnic cultural heritage.

The purpose of this study is to examine what roles of information professionals in local information departments in the Thai provincial university libraries are identified by the key workers in local information area.

In relation to this purpose the following research questions were formulated for this article:

How do the local information professionals from the Thai university libraries explain their functions and responsibilities at their working places?

What roles of local information professionals emerge from their explanations?

The context of research

Local information embraces various materials linked to local areas, their history, events, and documents7. In this respect, local information reflects the way of living in a local community, giving pride and local identity. Thai local information represents the multicultural assets which have been created throughout the establishment of the Kingdom of Thailand. Thai local citizens have their own unique customs, languages, traditional costumes, beliefs, and lifestyles, which are specific and differ among people in different parts of Thailand. Thai local information has been a vital means among Thai citizens to process, preserve, and transform this knowledge from generation to generation8.

The Kingdom of Thailand was established in the mid-14th century. It is an independent country under a constitutional monarchy in the region of Southeast Asia. In addition, Thailand is the only Southeast Asian country that has never been colonized by a European power. As of April 2021, the Thai population was almost 70 million. While about half of the population live in rural areas and half in urban areas, 15 percent live in Bangkok. The official language is Thai; however, distinct dialects of the Thai languages are spoken in different regional parts of Thailand, while English is a second language of the elite. Thailand has four border countries: Myanmar and Laos to the north, Myanmar to the west, Malaysia to the south, and Cambodia to the east. The mainland area of Thailand is about 510 890 square kilometres9. Geographically, Thailand is divided into six regions: Northern Thailand, Northeastern Thailand, Western Thailand, Central Thailand, Eastern Thailand, and Southern Thailand.

The majority ethnic group is Thai (95.9%). Thai culture is heterogeneous and descends from various ethnic Thai people. Interestingly, a great variety of Indian, Chinese, Burmese, Cambodian, Malaysian, and Western cultures and traditions are embraced. Additionally, Thai culture is influenced by the religions practiced, including Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, with an overwhelming majority (94%) of people practicing Buddhism10.

In Thailand, public libraries have a mission to collect and provide local information to local people, which is similar to the public libraries worldwide. According to the non-formal education policy, Thai public libraries should be learning centres and focus on serving the community as the information education, non-formal education, and local information centre11. However, the evaluation of public libraries in Thailand funded by the Educational Council of Thailand, conducted by Sacchanand, Prommapun and Sajjanand12, has shown that their performance was less than average. They are still severely underfinanced, lack competent staff and other resources.

Srisa-ard13 has explained that to compensate for this deficiency, the government policies such as Thai Local Wisdom and Information, Thai Indigenous Knowledge, National Education Act 1999, and the Promotion of Thai Wisdom into Education Management have influenced the work of university libraries. They have to follow these policies by managing and organizing the local information for the users. The changes in the learning environment to the sustaining and lifelong learning have been forcing the university libraries to take responsibility and re-engineer their role to proactively provide local information resources. Srisa-ard also indicated that the government policies have influenced the university libraries on local information management.

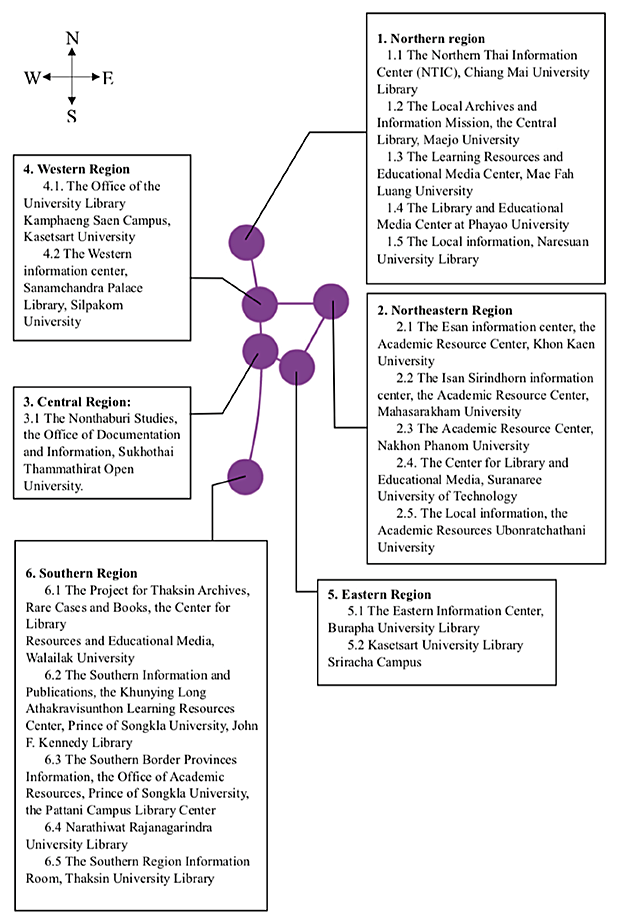

In order to manage library resources effectively and to promote information sharing among the provincial university libraries in Thailand, the Provincial University Library Network – formally abbreviated and referred to as PULINET – was established in 1986 by Chiang Mai University Library. PULINET unites 20 provincial public university libraries in regional areas of Thailand that have been established to support the main mission of the provincial universities: to support teaching, learning, researching, academic services, and preservation and conservation of arts and culture. These libraries undertake a range of collaborative projects within the network and benefit from sharing services and resources. The libraries PULINET members are located in six regional parts of Thailand (Northern, Northeastern, Central, Western, Eastern, and Southern). Each provincial university library (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The map of the PULINET and the location of the 20 local information departments

Within the PULINET organization, a Local Information Working Group was established in order to support Thai governmental policy on social and economic development in the regions, to support cultural education programs and to encourage the preservation and dissemination of local information. The Local Information Working Group consists of representatives from local information departments of the PULINET members14. The local information departments provide local information and services to the users and are a part of each provincial university library. The Local Information Working Group has become one of the most influential bodies setting the direction, creating the methods of work and even creating common databases in the area of local information. Its members bring the ideas and instructions on local information management, professional responsibilities and conduct back to their respective university libraries, thus cascading them further into the local information professional community and among librarians working with other library tasks.

The Thai provincial university libraries take part in management and delivering of local information to their researchers and students, but also to the communities, local people and other interested users. These Provincial university libraries support the local information work of public libraries and help them because they have more competent human resources, better budgets, and technology infrastructure than public libraries. Local information is viewed as part of the responsibility of the provincial university libraries for research and educational staff at the universities, for helping to further the development of research into Thai cultural heritage, and for promotions of the indigenous knowledge as well as the results of investigations of the local cultural heritage to the local community. The aim of the provincial university libraries work in local information is double – to keep the local traditional culture and lifestyle alive as a source of identity of local people; and to spread the idea of a multicultural Thai society, strengthening the sense of belonging to one nation.

This study is targeting the local information professionals working in the local information departments and representing them in the Local Information Working Group of the PULINET as the most experienced and influential in the area of local information work.

Literature review

Local information professionals as well as local studies librarians rarely figure as the objects or research in international literature because the main professional concerns are expressed and studied in national languages. But there are many more research publications exploring the roles of modern librarians. This literature is very vast. If we look at the investigations of the functions and responsibilities of modern librarians, we will find even more publications. They have been the focus of several exhaustive reviews. Thus, our literature review looks at the findings summarised in the reviews identifying and defining the roles of information professionals in modern libraries and presents what has been written on the roles of local information professionals or librarians in English literature.

Patrick Wilson explains the professional role is an outcome of education, traditions of the profession, its ideas, and expectations15. But the researchers of academic librarians related their roles to their work tasks, information services function and status16. Sometimes the functions in this context are understood widely, e.g., as educational, cultural, research, recreational, informational, and bibliographic, but sometimes they are as narrow as providing library services17, managing a collection or training information literacy skills18. Butler19 has related the essential role of the library and information professional to the main function of analysing information needs, planning and implementing services, and evaluating the impact of service. Ina Fourie20 used the analysis of literature to identify possible new roles for the librarians and has come up with a dozen of possible new roles. However, she has emphasized that “To take up these roles will require careful and timely preparation”21, including environmental scanning, research, collaboration and creative thinking.

Vassilakaki and Maniarou-Papaconstantinou have conducted an extensive systematic review of literature published over 14 years (from 2000 to 2014) and have identified that the existing and emerging roles of library and information professionals in university libraries were explored together with the involving specific skills sets, as follows: librarians as teachers, technology specialists, embedded librarians, information consultants, knowledge managers, and subject librarians22. Some of these roles were overlapping or synonymous, but each has attracted significant attention from researchers.

Studies of librarians’ role in the context of African countries reveal that librarians’ roles are defined by the specific context of users’ needs and conditions of library work23 and that some of them are conventional evolving roles, such as custodians of knowledge, information brokers, facilitators or educators; but others are emerging as revolutionary roles, such as research partners, advocators, copyright watchdogs, or media specialists24.

Looking for the studies about local information professionals’ roles we can point out that the earliest mentions are related to local history work in public libraries. Reed25 has suggested that the role of the local history librarian can be indicated as the manager of the local history collections and services for providing access to the public library users, which include researchers, local historians, students, local inhabitants, and other interested persons. Reed has pointed out the uniqueness of this work, claiming that “[i]f the local history librarian does not collect it, then no one else will”26. The British library and information association CILIP assigns similar three roles to the local studies librarians: “collecting local studies materials relevant to the whole of their community, making them accessible to as wide a range of users as possible and preserving those materials for the future”27.

Both Derryan28 and Reid29 agreed that the local history librarian must perform functions of collecting and disseminating the local history materials and to serve the users’ needs in terms of research and learning of the local history. This professional also supports these users in creating identity and historical awareness of the significance of locality and local history. My own investigation of the staff positions, related to local studies centres in English speaking countries, has shown that they mainly occupy positions of librarians30.

Digital technologies have not changed much the understanding of the professional functions and roles, but the study by Dewe31 has highlighted that the local studies librarian must act as a subject specialist and a good manager of resources and services in modern libraries. Furthermore, Sveum32 identifies the roles of the local studies librarian and the manager of the local studies collections as well as of a Norwegian local history wiki. Meanwhile, a strong emphasis on indigenous knowledge has stimulated a discussion about the role of libraries and information professionals in relation to its collection, recording, preservation and dissemination33. This last development, though not bringing much variation to the earlier discussed roles of local information professionals, except identifying one more advocacy role in relation to indigenous culture and knowledge, seems highly relevant to local information work in Thailand.

Another discussion pertinent for Thai local information professional work emerges in the studies about the rise of cultural heritage information professionals. Katherine Howard, in her dissertation on converging practice and role of professionals working in the sector of galleries, libraries archives, and museums, has identified broad roles for the information professionals in the whole cultural heritage sector. These roles are focused on securing the relevance of newly emerging broad work area (advocate and build relations with other professionals), but also on innovation in applying digital curation principles and adding value for users, but, most interestingly, on supporting social justice principles related to cultural heritage work34. This new type of role for local information professionals in helping to eliminate social inequalities and support inclusive indigenous public resources is emerging strongly in some recent research35, including the roles of academic librarians related to ensuring the diversity of local cultures36.

This overview of the previous research shows that the roles of local information professionals are strongly related to their activities, functions, tasks and service provision. This insight has helped us not only to identify the need of wider understanding how Thai local information professionals explain their roles, but also to select the theoretical framework based on the activity theory.

Theoretical approach

Activity theory is a multidisciplinary framework that can be applied to study human activity or practice37. Russian psychologists Lev Vygotsky and Alexei Leont’ev have developed it at the beginning of the 20th century to explore how individuals engage with historically developed and culturally shaped environments38. Different models were developed witin the activity theory. The Scandinavian activity theory enhanced by Yrjö Engeström is based on the concepts of Lev Vygotsky and Alexei Leont’ev39. Leont’ev has expanded the original activity theory to enable an examination of systems of activity at the macro level of the collective and community and added the social aspect, relationships between activity, action and operations, rules and norms, community, and division of labor were all added to the model by him40. Engeström41 has added community into the model. This version of the activity theory has included both the individual and group actions. This model was drawn from the concept that the joint activity or practices are units of analysis for activity theory. The model was developed as the conceptual tool to understand dialogue, multiple perspectives, and networks of interacting activities. Thus, it allows us to study the relationships between different activity systems42.

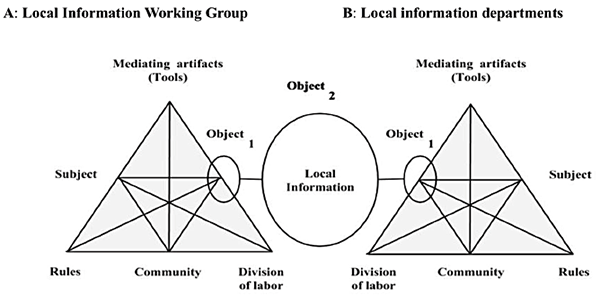

The different activity systems may be working on different but overlapping objects of activity and include different subjects, communities as well as apply different tools, norms and division of labor. However, the activity systems may be approaching the same object of activity, produce overlapping outcomes and even share tools and norms of their activities. The researcher has built her understanding of the local information activities on the basis of interacting activity systems’ model as developed by Engeström (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Interacting activity systems of the Local Information Working Group and the local information departments

This model explains the relationship between the activity systems of the Local Information Working Group and the various forms of local information departments in the university libraries. The Local Information Working Group includes the representatives of each provincial university library and operates at the interprovincial level developing common principles for and resources of local information (such as work guidelines, professional competence, or unified databases) serving all local information departments and their librarians. Its members are involved in local information work within the group, but also serve as mediators between it and the provincial university library that works with concrete local information on the provincial level and serves the users in the locality. Thus, these activity systems are united by the common object, shared community, division of labour and rules. They have overlapping subjects and tools, but different aims and outcomes of the activities. The latter two are not included in the figure.

The roles of the local information professionals working in the Thai provincial university libraries emerge through the examination of the interaction of these systems, as they are the feature of the subjects belonging to the communities of both activity systems. The roles are influenced by the division of labour, which is visible through the professional positions that local information professionals occupy in their libraries43. Their actions are guided by the rules of both communities and tools applied in working with local information. These features are visible in the functions and perceived responsibilities expressed by the librarians involved in both activity systems.

Research methods

The data was collected among the members of the Local Information Working Group of the Provincial University Library Network in Thailand. It is a working group of the PULINET that comprises 25 members. Each member of the group is a representative one of the twenty provincial university libraries and were specifically assigned to represent their libraries in the Local Information Working Group. The Group collaborates in the development of the local information management guidelines for the information professionals working in the local information departments of the provincial university libraries in Thailand. Furthermore, this group works together to collect and disseminate the local information through the internet to the public by creating the databases of local cultural heritage and other local information. Its members serve as mediators between the two activity systems (see Fig. 2).

During the study (2015–2017), two members were ill and did not participate in the Group activities. Therefore, twenty-three Group members participated in this study. They were all delegated by their respective libraries to the Local Information Working Group and worked with local information tasks full- or part-time depending on the size and focus of their libraries. As the libraries could assign the same persons as their representatives in the Group any number of times, the respondents had different duration of the experience in the Group – from one year to over 10 years. More experienced members occupied the leadership positions and were regarded as tutors of the younger members. Majority of the group members are women. To maintain the anonymity of the participant each member is assigned a personal number – PNxx.

The researcher has conducted twenty-three semi-structured interviews – one with each member of the Group. All the interviews were conducted at the end of 2017 using the social media LINE facility. These interviews lasted from 20 to 60 minutes. They were recorded and transcribed and analysed manually using the open coding scheme based on the chosen theoretical framework.

The interviews have covered a wide range of questions about the work of the Local Information Working Group activities and their relations with the whole community of local information professionals in the local information departments and elsewhere. Among others, one part of the interview dealt with different aspects of work in the local information departments at the provincial university libraries, another related to a more abstract understanding of roles of the local information professionals. The relevant interview material was coded in relation to the composite elements of the roles of local information professionals using the theoretical framework. However, the article was also informed by the observations of the Group meetings and field tours that were attended by the researcher, though this material is not used directly in this article.

According to the US Special Libraries Association, each professional has specific roles relating to the position, performed work tasks, and responsibilities44 of the librarians. This understanding of the librarians’ roles corresponds with the role elements identified using the activity system approach. Therefore, the data was analysed using the understanding of a role of a local information professional as related to the positions of local information professionals in libraries, the functions that they perform (activities and related work processes for achieving a particular aim), and responsibilities (rules governing duties to someone or being accountable for something). The roles emerge as a synthesis of these three elements.

Findings

This descriptive part of the results of the analysis is structured by first presenting the issues raised by the respondents about their jobs and work position in the provincial university libraries. The next part is highlighting the functions assigned to the local information professionals regardless of their job positions, related to the professional activities and their importance for the performance of the library itself. The last part is devoted to the responsibilities in a wider context of the local information profession and in relation to the served communities as well as to the wider Thai society.

Local information departments’ staff positions in libraries. Most of the participants of the study suggested that the provincial university libraries should establish a position of a local information professional at their local information departments as “the local information is important to each locality, and it represents the identity of each locality” (PN 20). These professional positions were closely related to the local information department as well as in other similar institutions:

Generally, there should be this position, whether, as a librarian or an information specialist. It is like an archivist in the archive (PN 03).

Some participants held position as librarians at the Local Information Departments and worked as full-time librarians, focusing on the local information work. However, most of the participants worked with local information part-time among other duties and responsibilities. One participant described her own working situation:

...some information professionals have many responsibilities. Our local information work is part of a library department. The local information is included in the service section. I am responsible for working in the service section for around 75% and the local information for 25% (PN 20).

The differences in librarians’ positions were related to the size and potential of university libraries and the participants were quite realistic in assessing these differences. When allocating jobs related to local information,

… it should be considered based on the possibilities, the policy, the budget of each university library, the potential of staff, IT, and resources (…) For some provincial university libraries, which have no local information collections or resources, the responsibility of the local information management should be a part of the general librarian’s job (PN 16).

But some participants suggested that the Local Information Working Group should take action to encourage the PULINET board to suggest setting positions for the local information work in all provincial university libraries, i.e. the members of the PULINET:

I would like to see the action of the Local Information Working Group to inform the PULINET committee (the directors of the provincial university libraries) to acknowledge the significance of the local information management and provide this special position at each university library (PN 04).

The professional status of librarians working with local information was emphasized by several participants, as “local information management requires a professional who thoroughly understands and has experiences to work in this area” (PN 23).

The local information professionals need specific job positions with designated time and work descriptions based on general aspects and procedures of information professionals in general and specializing to conduct local information work (PN 09). The issue of building expertise and achieving success while working with local information in a specified job position was strongly argued by the participants:

From my viewpoint, the position of “the local information professional” should be set by each provincial university library because it helps the development of local information management of each department and the Local Information Working Group. … Thus, he/she has more opportunities to learn and to successfully develop the local information projects and services, and collaboration projects with the Local Information Working Group (PN 04).

One of the participants has pointed out that when there is a position at a Local Information Department, only professionals should be eligible and they should be given more time to devote to the development of the local information work to do the duty. This will ensure their success while working directly, creatively, and effectively to develop the local information projects, services, activities and share the knowledge and experiences among the members of the local information department, with the colleagues in the Local Information Working Group, and with library users. The natural link between the job at and the benefit for the university library and the PULINET Working Group was stressed on several occasions. Two participants of the study pointed out that if there is a position of the local information professional at a Local Information Department, the person who holds this position will have a chance to develop activities at both their own department and the Local Information Working Group.

Functions of local information professionals. The participants claimed that an official job position could ensure the status of local information professionals in a library; however, they were even more relevant in fulfilling the functions of the library or the activities directed at achieving particular aims. Our participants have identified a range of such activities that characterize the work of the local information professional. Many of them have related these activities to the main processes of library or information work:

To work successfully the information professionals working in these local information departments should have their main role in the management of each process, including collection, storage, organization (classification, cataloguing), conservation, preservation, and dissemination of local information to users by using the library and information science methods (PN 23).

The need for planning of the whole work and collection development was identified as the initial point leading to information acquisition and further processes:

The information professionals should plan the local information management at the beginning stage. Then, they should collect the local information participating in the fieldwork. I think that this process is a core of the local information management (PN 18).

It is worth noting that the participants in the study have understood information acquisition in a very particular way, focusing on some particular sources and ways of collecting information:

They [local information professionals] should also develop the collection, by finding the local information (a primary source) from the local information specialists in the community and the local resources through fieldwork (PN 11).

Some of the participants mentioned that local information professionals collect not only information and documents, but also artefacts of tangible cultural heritage and evidence of local customs and traditions. Observations at two tours to local information departments in 2016 and 2017 have demonstrated that they collect artefacts and exhibit them for users. The organizing of exhibitions related to local culture and tradition is an accepted and routine practice in the provincial university libraries. Visited local information departments and libraries, in which they are situated, not only collect and provide local information in the printed or digital formats but also take care of and provide access to local cultural objects to users. This work is a natural part of local information department; therefore, local information professionals needed to take part in the acquisition, care, and displays of the collections of the tangible cultural heritage, for example, the artifacts or works of art. They also had to be responsible for the preservation of local information:

… Information professionals play the major role in preservation and conservation of the local information and cultural objects to support the sustainable learning (PN 09).

It is interesting that Local Information Working Group members recognize that material objects, other than documents, are part of the local information work and this confirms the close relationship between museum and library work:

The museums are recognized as the cultural heritage institutions. For this reason, the Local Information Working Group organizes the field trips to learn and study the management of the museums. Thus, the Group members can apply this knowledge in the local information work at their local information departments (PN 13).

In this respect, the participants saw libraries and museums and even archives as the same category of the cultural heritage institutions. The local information departments of the libraries in some cases performed the functions of museums or operated as archives.

The main aim with acquisition and managing of collections, “the information professionals’ role is to provide the local information to users, as the local information provider” (PN 07). The use of local information is increasing lately. It significantly affects the services of the local information departments. The information professionals working in them need to cope with the increasing use and interest in local information. Providing access to adequate local information sources and services to local people and other interested persons is one of the main functions of local information professionals.

Furthermore, two participants of this study indicated that the local information professionals should direct users to the local information sources (places, organizations) or the local information expertise in order to acquire more knowledge of local information.

The main role of information professionals working in the local information area is a local information referral mentor to guide the users for accessing to learn the local information from the local information specialists and local information sources by themselves (PN 21).

As more and more users are interested in accessing information in digital formats, local information professionals take care of information systems providing access to digital resources to community members (PN 18). Moreover, they cannot limit their function to service provision, but must get involved in promotion and persuasion of local people to understand and see the importance of local information. Thus, a local information professional’s duty is to promote awareness and appreciation of local information among different actors:

The information professional is a facilitator planning and managing the promotion of local information programs, services, and events through a variety of channels for the local community and interested users (PN 05).

Some participants of the study also indicated that the local information professionals must be local information supporters and teachers not only for users but also in their professional network:

They should act as local information supporters to educate and persuade the directors of provincial university libraries to see the importance of the local information and local information management. It is expected that the local information department will get more budget from the library, and the local information departments can apply these budgets on the development of local information management (PN 03).

Thus, local information professionals are involved in performing functions directed towards provision of local information through development of resources and ensuring access to the users and communities, but also in functions ensuring the internal capabilities of libraries to perform these functions. Many responsibilities of local information librarians are related to ensuring of these internal capabilities and service quality.

Responsibilities in the local information work. The responsibilities in our understanding involve duties towards certain communities, though sometimes these duties may pertain to more than one community.

Thus, most of the participants were acutely aware of the necessity to devote full-time attention to the local information to acquire experience, but mainly to set up an effective service and gain authority and respect in the university library. Thus, the acquisition and demonstration of expertise is seen as a responsibility towards the professional community working with local information. The respondents claimed that the local information is an extensive area, and takes time and effort for the related staff to gain experience and knowledge:

This local information work is wide and specific. Also, the local information professional requires time to learn because the local information work is related to the way of life of generations in various issues. These issues are critically sensitive, and the local information professional needs the experience to understand the local information context to work effectively in this field (PN 11).

Local information professionals could acquire expertise about their local area by attending the local activities such as meetings, trainings, workshops, seminars, conferences, field trips or other events:

They can also learn the local by going to study the real settings, events in the locality. For example, participating in the monk ordination ceremony should help the information professionals to understand the local tradition (PN 11).

Thus, the acquisition of expertise involves contacts with local communities and contexts and helps to ensure the quality of the service and resources provided for these communities. Therefore, one of the main responsibilities of a local information professional is learning always and everywhere, for example, at the job or in-service training, or self-educating themselves. A participant in this study expressed her view that:

I think that the information professionals working in this area should be a local information learner. They should continue learning about the local information and local information management to have more understanding in this area by reading and learning from different sources by themselves as well as learning from work (PN 11).

The acquired knowledge should be used in providing guidance to users as the main responsibility of the local information professionals is to assist their users in accessing required local information. Their understanding of users and local information helps in customization of the relevant local information to the users’ needs:

They must be able to identify the local sources for users. For instance, they can inform the users about the boat race at Phimai, and the temple that organizes this event. Or they can suggest the users get the information about the temples where they can go and learn about the candle carving during the Buddhist Lent candle parade (PN 15).

The management, maintenance and preservation of local information collections is helped by the digitalization and modern technologies of conservation and preservation. It was emphasized by some participants who also deal with digital curation that local information professional needs to master this digital environment “in this era, when the digital technology has affected all process such as the preservation” (PN 12).

In addition, as local information must be available to users in any form, printed and non-printed, the participants mentioned that the information professionals should know and understand how to disseminate local information in different formats through the IT channels to reach the needs of the users:

The information professionals working in the local information departments should learn and know how to disseminate the local information collections and services to the users in various formats by applying technology that is consistent with the behaviour of people in the present era (PN 21).

The participants have accentuated that the responsibility of the local information professionals extends not only to their users, but also to their communities as qualified and devoted investigators. They have related the quality of the services, collections and information resources to the conducting research and working with the data from the community:

There is a discussion on the role of an information professional as a researcher within the group. The questions on this issue: for instance, does a librarian have to participate in fieldwork to collect data? Is it the duty of a researcher? Afterward, we conclude that being a researcher is a part of an information professional’s role. So, we must conduct research to collect data (a primary data) and distribute the data to the users (PN 22).

In this case, the participants emphasized that information professionals must understand research, for example, the research process or distinguish qualitative research from quantitative research, but also be aware how to present its results to the public: “As a researcher, the information professional knows the data collection methods, data presentation, and data dissemination” (PN 11). On the other hand, working successfully as a researcher requires learning about the locality or a community: “The researchers should read a lot of books and study the basic information about the local matters before collecting the local information” (PN 04). This understanding and research competence also helps in expanding and updating relevant services:

We joined the fieldwork to collect data on the local culture and tradition, for example, about the belief on spirits in Phayao province, and disseminated this local information to the students and the interested people (PN 14).

The knowledge about a specific locality, also helps in teaching their users about it (PN 23). The participants argued that it is necessary to encourage the local people and the public to understand the value and importance of local information, and local information professionals should work to persuade them to conserve and preserve local information from generation to generation: “Furthermore, they must recommend the local people to study and conserve the local information” (PN 23). The local information professionals must be directly involved in teaching local information at all levels, for instance, secondary school, high school, higher education, and adult education. On each level, they must explain the value and the need for preservation of local information and how to do this. The content of local information lessons depends on the requirements of the schools and the cultural background of the learners. It was also indicated that effective teaching would assist the learners in having better or more understanding of their locality and the local information area (PN 23).

On the other hand, local information professionals are not the only experts of local cultures and knowledge. The empirical data of the study shows that the participants of the study agreed that the primary responsibility of local information professionals was to collaborate with the local experts, the local community and the local information organizations to perform their main functions of further development of the local information collections, and of dissemination and promotion of local information services to the local people:

The information professionals must play an essential role in connecting with the local experts who have the knowledge and understand the local aspects to learn the local information (PN 18).

Thus, local information professionals become a link in a chain of different interest groups and persons. Collaboration between the local organizations and people in each community or locality can be particularly fruitful for the development of the local information collections. The participants believed that the information professionals should create network of local information with the local organizations and people in each community. The local information professionals as collaborators must be diplomats. They need to involve in the collaboration the participants from both up and down, the experts and the learners, the organizations and the individuals.

The local information networks should be developed on the local and national levels. Basically, collaboration is related to working together for sharing knowledge and experiences, local information resources, duties and work to reach the mutual goals. The local information context included the collaborators of the local information professionals doing local information work, related local organizations, other local information departments, the provincial university libraries, the public libraries, the schools, the universities, and the local information network, namely, PULINET. The main responsibility of the local information professionals in this collaborative environment was to educate the local leaders, namely the local officers and local politicians and other participants to appreciate the importance of local information and local information collections. They must enlighten the local leaders and other participants about the value of local information and encourage to preserve it from generation to next generation.

Discussion of roles

This section of the paper synthesizes the descriptive part of the analysis and explains the roles emerging from the amalgamation of job positions and duties, functions of the local information professionals within the library work, and their wider responsibilities to different types of communities. This part not only synthesizes the results but also explores their significance in light of previous research.

Though the positions occupied by the local information professionals in libraries varied in terms of job descriptions, time allocated for local information work and organisational structures, the participants have agreed about the centrality of the local information professional in the Thai provincial university library. Though most of the participants seemed to be more worried about the status of a local information professional in the university library and consistency of their work, they were also relating these jobs and their status to the overall quality of local information service, its complexity and importance for the served university and local communities.

Examining the results of the analysis of the positions, functions and responsibilities, we can identify a number of local information professional roles.

One that is visible immediately can be identified as a role of the information manager, who as the main local information professional is responsible for the management of the local information and processes related to its maintenance, for example, acquisition, collection development, organization, access, and information dissemination. The role emerges from the functions of the professionals at the local information department and the responsibility to maintain and ensure the quality of the collections and services. This finding resonates with the previous studies showing that the local information professionals should manage the local information resources and work with them45. Dewe46 indicated that the local studies librarians have to be the good managers of the local studies resources and services. Reed47 talks about the management of local history collections. However, these differences in terminology and even in aspects of work do not affect the functional basis of the role and the responsibility to acquire necessary skills for performing it.

A role strongly associated with the previous one relates to the heterogeneous nature of local information collection, which includes not only physical (printed, handwritten and produced on different materials) and digital documents, but also artefacts and cultural heritage objects or data about cultural traditions. This makes the work of local information departments close to the work of museums and archives, and requires the local information professionals to perform the role of a curator. Philips48 actually writes in her book about the curators of local history collections. The curator has the major duties and responsibilities in all activities: the acquisition, development, organizing, preserving and conserving, and exhibiting the tangible and intangible cultural heritage collections in the cultural heritage institutions for providing access to professional and the general public. In this respect, the local information professional needs to deal with the management of the local information objects in their institutions, has to think of the ways to represent them digitally. This aspect makes them work as a curator and a digital curator in a modern museum49, or turns into a cultural heritage information professional50.

It is interesting that the participants have arrived to a conclusion that being a researcher is essential for ensuring the quality of the local information collections and a responsibility towards the served community, and that the data collection in the field is the activity that local information professionals should perform by using research methods. Hajibayova and Buente51 have identified the link between the understanding of local cultural phenomena and their representation through metadata, that was partly attributed to the role of a researcher in this study. This role is also visible in communicating with local information experts, researchers and helping users to find relevant information.

The finding also revealed that a service provider is a significant role of the local information professional. As a service provider, the professional has to prepare and deliver access to the local information resources and provide services to users, including referral services and guidance or selection and recommendation of the most appropriate resources. Previous research highlighted this role of the local studies librarian and local history librarian as well52. Dewe53 indicated that the local studies librarians should be adept at providing accessibility and accommodation resources and services in the local studies. Moreover, Reid54 indicated that the library professionals working in the local studies libraries in the digital era should provide online services for users.

Furthermore, the local information professionals must handle the role of a promoter of the local information resources, services, and activities to users, and encourage them to use and access the local information services. Consequently, these users might be able to foresee the significance of the local information. Three studies conducted by Derryan, Dewe, and Reid support this finding. Dewe55 indicated that the promoter needs to heighten the value of their local studies. Furthermore, Derryan56 and Reid57 indicated that the local history librarian has to create the identity and historical mindfulness of the importance of locality and local history. This role is quite close to the modern role of an advocate defending the necessity of local information work and the dignity of the local information professional.

Both roles of the service provider and the promoter are closely related to the role of an educator, who is involved in multiple educational activities of users helping their understanding of local heritage, personal and community histories and schooling members of communities, university management and researchers about the importance of local information and subtleties of its usage. This role was identified as one of the main roles of librarians in the extensive study of literature by Vassilakaki and Moniarou-Papaconstantinou58. Cherinet59 has also identified that an educator is one of the conventional evolving roles of librarians.

The role of an educator seems to be a mirror reflection of a role that emerges as having the utmost importance – the role of a learner. It is emphasized in the requirement to ensure full-time position for local information professionals so that they can learn and deepen their knowledge of local information. They need to visit other libraries and cultural heritage institutions, such as museums, to learn from them. Learning can involve reading and using various sources, studying the local setting, training research skills, or mastering digital technologies. The role of a learner was emphasised in other studies. Martin60 pointed out that at local studies, librarians obtain professional knowledge by studying in formal education institutions, and learn specific local studies topics while working. Reid61 claimed that the library staff in the local studies libraries should study the changes in users and their environments, and learn how to use the new technologies refining and updating their skills throughout their professional life. The same responsibilities to learn about local cultures, new technologies, changes in users are identified by the respondents of this study.

The local information professionals participating in the study have emphasized that they are required to work together with many others in their own library, from their local institutions, other libraries within the PULINET and outside of it. These persons may have different understanding, knowledge and experience and understand local information differently. Thus, they must have the ability to play the role of a collaborator in developing local information work and projects. Derdkhuntod and Dewe62 also have demonstrated that a local information professional or a local studies librarian should act as a collaborator. Derdkhuntod highlighted that the professionals working in the local information department should act as a collaborator in the local information area63. Dewe64 also indicated that the local studies librarians must be able to function successfully with the national and local governments.

All in all, it is evident that the participants of the study were focusing on conventional and evolving roles, such as information managers or service providers. Often they were speaking about the roles directly naming them in their utterances, e.g., talking about the roles of a mentor, a facilitator, a curator, or an information manager. Digital technologies require new skills; therefore, they figure mainly as tools that the local information professionals need to master and apply. However, there is also evidence that the participating librarians are thinking wider and reflect on such roles as a researcher of local traditional knowledge, advocator and promoter of it on various levels and to different users, curator of cultural heritage that is understood wider than just information and documentation. These roles have a potential to grow in their significance and give a start to different approaches and work with local information in Thailand.

Conclusions

In this final part of the article, the answers to the raised research questions will be provided and further directions for research will be suggested.

The first questions were related to the examination of how the local information professionals representing their libraries in the Local Information Working Group define and explain their professional functions and responsibilities. They have talked about the positions of local information professionals in the provincial university libraries, their activities and responsibilities in achieving the aims of local information departments in terms of the status of a specific area of information profession requiring special knowledge, training, and recognition. This recognition, knowledge and skills are necessary for developing local information resources and creating the necessary conditions for service provision to the communities and for the collaboration with other experts in the area of local information. Building networks of institutions and individuals on different levels working with local information is one of the conditions to ensure the necessary level of understanding and competence for preservation of local cultural heritage and promotion of its use and renewal in the modern Thai society.

By synthesizing the descriptive explanations of the job positions, functions and responsibilities we have identified eight roles of local information professionals as perceived by the Local Information Working Group members and provide an answer to the second research question. Some of these roles seem to be directly connected to the performance of the library functions, such as an information manager and a service provider, while others point to the interactions with other actors for various purposes, such as a collaborator, an educator, or a promoter. The role of a curator is interesting in this respect as it points to the common or at least similar responsibilities and work tasks of all cultural heritage institutions rather than to collaboration with them. The roles of a learner and a researcher underscore the importance of the acquisition and application of special competence related to the increase of the quality of the local information resources and services.

As we can see, the respondents in this study have understood their professional roles in a rather traditional way, though there are some pointers to the potential development in the future. With proper attention to the local information workers and training for the professionals they could expand and mature as suggested by Fourie65. However, the understanding of supporting social justice principles through or active inclusion of the communities in the local information work is not visible in this research. Thus, we have not identified any revolutionary roles66 of local information professionals.

References

1. ABELS, Eileen; JONES, Rebecca; LATHM, John; MAGNONI, Dee; MARSHALL, Joanne Gard. Competencies for information professionals of the 21st century. Revised ed. Alexandria, USA: Special Libraries Association, 2003, [accessed 7 March 2021] Access through Internet: <http://www.sla.org/PDFs/Competencies2003.pdf/>.

2. BENSON, Angela; LAWLER, Cormac; WHITWORTH, Andrew. Rules, roles and tools: Activity theory and the comparative study of e‐learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2008, vol. 39, no. 3, p. 456–467.

3. BUTLER, Pierce. An introduction to library science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1933. 201 p.

4. CHERINET, Yared Mammo. Blended skills and future roles of librarians. Library Management, 2018, vol. 39, no, 1/2, p. 93-105.

5. CHUPWA, Chalermsak. Naewthang Phattana Sakkayaphaph Khong ukhalakorn Khayngan Hongsamut Mahawitayarai Suanphumipak (PULINET) [A Guideline for the development of PULINET personnel potentials]. Mahasarakham: Academic Resources Center and Department of Library and information science, Mahasarakham University, 1998. 138 p.

6. CILIP. Local studies librarians. London, 2021. [accessed 7 April 2021]. Access through Internet https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/localstudieslibrarian

7. CORRALL, S. Roles and responsibilities: Libraries, librarians and data. In G. Pryor (Ed.), Managing research data. London: Facet Publishing, 2012, p. 105-133.

8. DERDKHUNTOD, Nayika. Bukhalakorn Lae Kan Pattana Bukhalakorn Ngan Kor Moon Thong Thin Nai Hongsamut. [Library staffs and development of local information staffs of university libraries]. Information, 2005a, vol. 12, no. 2, p. 63-74. ISSN 0859-015X.

9. DERDKHUNTOD, Nayika. Raingan Kan Sumrot Beongton Kopkhet Khamrubphidshop Lae Aadtrakumlang Thi Phatibatngan Dan Kormoon Thongthin Khong Hongsamut Samachik Khana Thamngan Kormoon Thongthin Khayngan Hongsamut Mahawitayarai Suanphumipak [A survey of the numbers; qualification and responsibility of library staffs working in the Local information center of the Provincial University Libraries Network]. Khon Kaen: The Academic Resource Center, Khon Kaen University, 2005b.

10. DERRYAN, Paul. Reference and information work in local history: Training for librarians. Education for Information, 1998, vol. no. 3, p. 323-328.

11. DEWE, Michael. (Ed.). Local studies collection management. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2002. 208 p. ISBN 0566083655.

12. ENGESTRÖM, Yrjö. Innovative learning in work teams: analysing cycles of knowledge creation in practice. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen & R.-L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 377-404.

13. ENGESTRÖM, Yrjö. Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 2001, vol.14, no.1, p. 133-156.

14. FOURIE, Ina. Librarians and the claiming of new roles: how can we try to make a difference. Aslib Proceedings, 2004, vol. 56, no. 1, p. 62-74.

15. GRANDA, R.; MACHIN-MASTROMATTEO, J.D. Recovering troubled cities through public spaces and libraries: The Caracas Metropolitan Strategic Plan 2020. Information Development, 2018, vol. 34, no. 1, p. 103-107.

16. HAJIBAYOVA, Lala; BUENTE, Wayne. Representation of indigenous cultures: considering the Hawaiian hula. Journal of Documentation, 2017, vol. 73, no. 6, p. 1137-1148. [accessed 7 March 2021] Access through Internet: <https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-01-2017-0010/>.

17. HOWARD, Katherine. Educating cultural heritage information professionals for Australia’s galleries, libraries, archives and museums: A grounded Delphi study. Doctoral dissertation. Queensland University of Technology, Australia, 2015.

18. KUHLTHAU, C. C. Seeking meaning: a process approach to library and information services. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited, 2004.

19. LEONT’EV, A. N. Activity, consciousness, and personality. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1978.

20. LERDSURIYAKUL, K. Public library in Thailand. In 65th IFLA Council and General Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, August 20- August 28, 1999, [accessed 8 April 2021] Access through Internet: <http://origin-archive.ifla.org/IV/ifla65/papers/106-79e.htm>

21. MAKEPEACE, C. E. Acquisition. In Michael D. (Ed.). Local studies collections: A manual, Volume 1. Hants: Gower, 1987, p. 181-210.

22. MARTIN, Don. (Ed.) Local studies libraries: Library Association guidelines for local studies provision in public libraries. (2nd ed.) London: Library Association Publishing, 2002. 80 p. ISBN 978-1856042772.

23. MIETTINEN, R.; SAMRA-FREDERICKS, D.; YANOW, D. Re-turn to practice: an introductory essay. Organization Studies, 2009, vol. 30, no. 12, p. 1309–1327.

24. Ministry of Culture. Ministry of Culture’s mission. Retrieved January 23, 2021, from http://www.m-culture.go.th/th/ewt_news.php?nid=3

25. MOSHOESHOE-CHADZINGWA, M.M. Diversity, inclusivity, social responsibility aspects, and outcomes of a mobile digital library and information service model for a developing country: The case of Lesotho. The International Journal of Information, Diversity & Inclusion, 2020, vol. 4, no. ¾, p. 51–68.

26. NAKITARE, Joel; SAWE, Emily; NYAMBALA, Joyce; KWANYA, Tom. The emerging roles of academic librarians in Kenya: apomediaries or infomediaries? Library Management, 2020, vol. 4, no. 6/7, p. 339-353. ISSN 0143-5124. [accessed 7 March 2021] Access through Internet: <https://doi-org.lib.costello.pub.hb.se/10.1108/LM-04-2020-0076/>.

27. NATHAN, L.P.; PERREAULT, A. Indigenous initiatives and information studies: Unlearning in the classroom. The International Journal of Information, Diversity and Inclusion, 2018, vol. 2, no ½, p. 67-85.

28. The Network Technology Lab (Ntl), National Electronics And Computer Technology Center (Nectec). NBTC Internet Statistics Report v 2.0. 2017. [accessed 28 September 2017] Access through Internet: <http://webstats.nbtc.go.th/netnbtc/HOME.php/>.

29. NONTHACUMJANE, Pussadee. Local studies in Western countries libraries. Borås: University of Borås, 2017, 14 p.

30. PHILIPS, Faye. Local history collections in libraries. Westport: Libraries Unlimited, 1995. 164 p.

31. The Provincial University Library Network. Members. PULINET, 2020, [accessed April 10, 2021]. Access through internet http://pulinet.org/member/.

32. REED, Michael. Local history today: Current themes and problems for the local history library. Journal of Librarianship, 1975, vol. 7, no. 3, p. 161–181, [accessed 7 March 2021] Access through Internet: <https://doi.org/10.1177/096100067500700304/>.

33. REID, Peter H. The digital age and local studies. Oxford: Chandos Publishing, 2003. 237 p. (Chandos Information Professional Series). ISBN 978-1-84334-051-5.

34. RICE-LIVELY, M. L.; RACINE, J. D. The role of academic librarians in the era of information technology. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 1997, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 31-41. doi:10.1016/S0099-1333(97)90069-0

35. SACCHANAND, C.; PROMMAPUN, B.; SAJJANAND, S. Development of indicators for performance evaluation of public libraries in Thailand. Bangkok: Education Council, 2006.

36. SAENWA, Sumattra. Bodbaht Lae Khamroo Khamsamat Khong Bannarak Hongsamut Sathabunudomsuksa [Roles and competencies of librarians in academic libraries]. Journal of Behavioral Science for Development, 2014, vol. 6, no. 1, p.104-120.

37. SARKHEL, Juran Krishna. (2017). Strategies of indigenous knowledge management in libraries. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries, 2017, vol. 5, no. 2, p. 427-439. ISSN 2241-1925.

38. SCHLUMPF, Kay; ZSCHERNITZ, Rob. Weaving the past into the present by digitizing local history. Computers in Libraries, 2007, vol. 27, no. 3, p. 10-15.

39. SOMBOONANEK, Sineenard. Kormoon Thongthin Kab Thang Leuxk Mai Khong Hongsamut [Local information and library new trends]. Academic Services Journal Prince of Songkha University, 2001, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 52-62.

40. SRISA-ARD, S. Academic libraries and local information management: Experiences of Academic Resource Center, a paper in ICAL, Mahasarakham University, Thailand, 2009. [accessed February 22, 2021]. Access through Internet from http://crl.du.ac.in/ical09/papers/index_files/ical-82_138_301_1_RV.pdf

41. STEVENS, Amanda. A different way of knowing: Tools and strategies for managing indigenous knowledge. Libri, 2008, vol.58, p. 25-33. ISSN 0024-2667.

42. SVEUM, Tor. Local studies collections, librarians and the Norwegian local history wiki. New Library World, 2010, vol. 111, no, 5/6, p. 236-246.

43. TANLOET, Piyasuda; TUAMSUK, Kultida. Bodbaht Khong Hongsamut Lae Nakwichacheep Sarasonted Sumrub Hongsamut Sathabunudonsuksa Thai Phuthasakrarach 2553-2562” [The roles of Thai academic libraries and its information professional in the next decade (A.D. 2010–2019)]. Songkhanakarin Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2011, vol. 17, no. 4, p. 34–36.

44. Thai parliament. Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, B.E. 2550 (2007), sec. 66. [accessed April 3 2021] Access through Internet http://library2.parliament.go.th/giventake/content_thcons/18cons2550e.pdf

45. Thailand population (live). Worldometer, [accessed April 10, 2021]. Access through Internet https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/thailand-population/

46. VASSILAKAKI, Evgenia; MONIAROU- PAPACONSTANTINOU, Valentini. A systematic literature review informing library and information professionals’ emerging roles. New Library World, 2015, vol. 16, no.1/2, p. 37–66. ISSN: 0307-4803.

47. VYGOTSKY, L.S. Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978.

48. WILSON, Patrick. Second-hand knowledge: an inquiry into cognitive authority. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood P, 1983. 210 p. ISBN 0313237638.

49. WILSON, Tom. Activity theory and information seeking. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, ARIST, 2008, vol. 42, p. 119–161.

50. YAKEL, Elizabeth; CONWAY, Paul; HEDSTROM, Margaret; WALLACE, David A. Digital Curation for Digital Natives. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 2011, vol. 52, no. 1 (Winter), p. 23–31.

1 Thai parliament. Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, B.E. 2550 (2007), sec. 66. [accessed April 3 2021] Access through Internet <http://library2.parliament.go.th/giventake/content_thcons/18cons2550e.pdf>

2 MARTIN, Don. (Ed.) Local studies libraries: Library Association guidelines for local studies provision in public libraries. (2nd ed.) London: Library Association Publishing, 2002; REED, Michael. Local history today: Current themes and problems for the local history library. Journal of Librarianship, 1975, vol. 7, no. 3, p. 161–181; REID, Peter H. The digital age and local studies. Oxford: Chandos Publishing, 2003. 237 p. ISBN 978-1-84334-051-5.

3 The Network Technology Lab (Ntl), National Electronics And Computer Technology Center (Nectec). NBTC Internet Statistics Report v 2.0. 2017. [accessed 28 March 2021] Access through Internet: <http://webstats.nbtc.go.th/netnbtc/HOME.php/>.

4 SOMBOONANEK, Sineenard. Kormoon Thongthin Kab Thang Leuxk Mai Khong Hongsamut [Local information and library new trends]. Academic Services Journal Prince of Songkha University, 2001, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 52–62; DERDKHUNTOD, Nayika. Bukhalakorn Lae Kan Pattana Bukhalakorn Ngan Kor moon Thongthin Nai Hongsamut. [Library staffs and development of local information staffs of university Libraries]. Information, 2005a, vol. 12, no. 2, p.63-74. ISSN 0859-015X.

5 CHUPWA, Chalermsak. Naewthang Phattana Sakkayaphaph Khong Bukhalakorn Khayngan Hongsamut Mahawitayarai Suanphumipak (PULINET) [A Guideline for the Development of PULINET Personnel’ Potentials]. Mahasarakha: Academic Resources Center and Department of Library and information science, Mahasarakham University, 1998. 138 p.; TANLOET, Piyasuda; TUAMSUK, Kultida. Bodbaht Khong Hongsamut Lae Nakwichacheep Sarasonted Sumrub Hongsamut Sathabunudonsuksa Thai Phuthasakrarach 2553-2562” [The roles of Thai academic libraries and its information professional in the next decade (A.D. 2010–2019)]. Songkhanakarin Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2011, vol. 17, no. 4, p. 34–36; SAENWA, Sumattra. Bodbaht Lae Khamroo Khamsamat Khong Bannarak Hongsamut Sathabunudomsuksa [Roles and Competencies of Librarians in Academic libraries]. Journal of Behavioral Science for Development, 2014, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 104–120.

6 DERDKHUNTOD, Nayika. Raingan Kan Sumrot Beongton Kopkhet Khamrubphidshop Lae Aadtrakumlang Thi Phatibatngan Dan Kormoon Thongthin Khong Hongsamut Samachik Khana Thamngan Kormoon Thongthin Khayngan Hongsamut Mahawitayarai Suanphumipak [A survey of the numbers; qualification and responsibility of library staffs working in the Local information center of the Provincial University Libraries Network]. Khon Kaen: The Academic Resource Center, Khon Kaen University, 2005b.

7 MAKEPEACE, C. E. Acquisition. In Michael D. (Ed.). Local Studies Collections: A Manual Volume 1. Hants: Gower, 1987, p. 184.

8 Ministry of Culture. Ministry of Culture’s mission. Retrieved January 23, 2021, from http://www.m-culture.go.th/th/ewt_news.php?nid=3

9 Thailand population (live). Worldometer, [accessed April 10, 2021]. Access through Internet https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/thailand-population/

10 Ministry of Culture, http://www.m-culture.go.th

11 LERDSURIYAKUL, K. Public library in Thailand. In 65th IFLA Council and General Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, August 20- August 28, 1999. Retrieved January 25, 2017, from http://www.glib.hcmuns.edu.vn/elib/iflanet/IV/IFLA65/PAPERS/106- 79E.HTM

12 SACCHANAND, C.; PROMMAPUN, B.; SAJJANAND, S. Development of indicators for performance evaluation of public libraries in Thailand. Bangkok: Education Council, 2006.

13 SRISA-ARD, S. Academic libraries and local information management: Experiences of Academic Resource Center, a paper in International Conference on Academic Libraries (ICAL-2009), Delhi, India, October 5–8, 2009. [accessed February 22, 2021]. Access through Internet from http://crl.du.ac.in/ical09/papers/index_files/ical-82_138_301_1_RV.pdf

14 The Provincial University Library Network. Members. PULINET, 2020. [Accessed April 10, 2021]. Access through internet http://pulinet.org/member/.

15 WILSON, Patrick. Second-hand knowledge: an inquiry into cognitive authority. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood P, 1983. 210 p. ISBN 0313237638.

16 RICE-LIVELY, M. L.; RACINE, J. D. The role of academic librarians in the era of information technology. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 1997, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 31–41. doi:10.1016/S0099-1333(97)90069-0

17 KUHLTHAU, C. C. Seeking meaning: a process approach to library and information services. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited, 2004, p. 114.

18 CORRALL, S. Roles and responsibilities: Libraries, librarians and data. In G. Pryor (Ed.), Managing research data. London: Facet Publishing, 2012, p. 105–133.