Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2022, vol. 78, pp. 46–79 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2022.78.106

Cicero, Voltaire and the Bible: French Best-Sellers in the Age of Enlightenment?*

Simon Burrows

School of Humanities and Communication Arts

Western Sydney University

Locked bag 1797, Penrith Mail Centre

Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia

E-mail: s.burrows@westernsydney.edu.au

* Research for this article was supported by the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Project DP160103488 ‘Mapping Print, Charting Enlightenment’ (MPCE).

Summary. Since the early twentieth century, when Daniel Mornet conducted his path-breaking survey of private library catalogues in an attempt to determine what people read during the enlightenment, historians have debated how to identify the best-selling texts in the distant past. Besides library catalogues, scholars of eighteenth-century France have ransacked will inventories, publishers’ archives, print licence registers, book auction records, the titles available in cabinets de lecture, and even the extraordinarily rich records of books stamped in an amnesty for pirated editions in 1777–1781. This article suggests that none of these sources taken in isolation can give us sufficient insight to provide a reliable overview of the book trade and the market for books. Taken together and analysed digitally, however, they give important representative insights into the best-selling texts, genres and authors of the eighteenth century. The article compares and contrasts the findings of several large-scale digital projects to identify and explore the best-selling – or most frequently-encountered-texts across a number of genres including school-books, self-help manuals, popular medical texts, creative literature and religious works. In the process, it will help us to think more critically about what constituted a best-seller in the early modern period. By revealing some broad contours of eighteenth-century print culture, it will also challenge existing narratives of the enlightenment, secularisation, popular literacy and the book trade.

Keywords: Enlightenment, eighteenth-century France, publishing, private libraries, Imitation of Christ, philosophes

Ciceronas, Volteras ir Biblija: prancūzų bestseleriai Apšvietos amžiuje?

Santrauka. Nuo XX a. pradžios, kai Danielis Mornet atliko savo inovatyvų privačių bibliotekų katalogų tyrimą siekdamas nustatyti, ką žmonės skaitė Apšvietos amžiuje, istorikai diskutavo, kaip atpažinti perkamiausius tekstus tolimoje praeityje. Be bibliotekų katalogų, XVIII amžiaus Prancūzijos mokslininkai įnirtingai tyrinėjo testamentų registrus, leidėjų archyvus, spaudos licencijų registrus, knygų aukcionų įrašus, skaityklose (pranc. ca binets de lecture) esančius kūrinius ir net nepaprastai gausią amnestuotų piratinių 1777–1781 m. knygų leidimų dokumentaciją. Šiame straipsnyje teigiama, kad nė vienas iš šių šaltinių atskirai negali suteikti mums pakankamai įžvalgų, kad galėtume pateikti patikimą prekybos knygomis ir knygų rinkos apžvalgą. Tačiau paimti kartu ir analizuoti skaitmeniniu būdu jie suteikia svarbių reprezentatyvių įžvalgų apie XVIII amžiaus geriausiai parduodamus tekstus, žanrus ir autorius. Straipsnyje lyginamos ir supriešinamos kelių didelio masto skaitmeninių projektų išvados, siekiant nustatyti ir ištirti perkamiausius arba dažniausiai aptinkamus įvairių žanrų tekstus, įskaitant mokyklinius vadovėlius, savigalbos vadovus, populiariosios medicinos tekstus, kūrybinę literatūrą ir religines knygas. Tai padės mums kritiškiau įvertinti, kokie kūriniai ankstyvajame moderniajame laikotarpyje buvo laikomi bestseleriais. Kai kurių plačių XVIII amžiaus spaudos kultūros kontūrų atskleidimas taip pat meta iššūkį esamiems Apšvietos amžiaus, sekuliarizacijos, visuotinio raštingumo ir knygų prekybos naratyvams.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: Apšvietos amžius, XVIII amžiaus Prancūzija, leidyba, privačios bibliotekos, Kristaus imitacija, filosofai.

Received: 2021 11 07. Accepted: 2022 03 18

Copyright © 2022 Simon Burrows. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

On 18 October 1782, Parisian customs inspectors confiscated 70 copies of Saint Thomas à Kempis’ renaissance Christian masterpiece L’Imitation de Jésus Christ from a Parisian bookseller, Jean-François Colas, during one of their routine twice-weekly inspections of book consignments passing through the Chambre Syndicale de la Librairie et de l’Imprimerie [the guildhall of the Parisian booksellers and printers].1 It was not unusual for innocuous devotional books to be ‘suspended’ in this way, because popular religious works were frequently ‘counterfeited’ in violation of legal privilèges [i.e. monopolistic rights over the production of a title]. In this case, rather unusually, the books turned out to be legitimately produced and their release was ordered on the day of the confiscation. This instance is unique among 2,162 consignments recorded in the confiscation registers because it contained no less than four editions of the same work. There were ten copies of a duodecimo edition of père Jean Brignon’s translation and a further six copies of a smaller, pocket-sized edition in-24 format. There were also 20 copies of a rival translation by de Beuil – a.k.a. Louis Isaac Le Maistre de Sacy – in duodecimo format and 34 more in-24. Conspicuously absent were any copies of the yet more popular translation by the Jesuit theologian père Jérome de Gonnelieu (1640–1715), which was just one of several other versions circulating in late eighteenth-century France. The others included translations by the abbé Joseph Valart (1698–1781) and a verse translation by the seventeenth-century tragedian Pierre Corneille.

Shareholdings in the various translations were hot property. They typically traded among Parisian guild members in much smaller parcels than for popular secular works, even though profits per copy for the Imitation du Christ were generally far less on account of their small formats and the cheap paper on which they were printed. In October 1781, at the bankruptcy sale of Edmé-Jean Le Jay père, the Parisian bookseller Jean-Gabriel Mérigot, jeune, bought shares for 1/20th, 1/60th and 1/180th of the privilège in the Corneille verse translation in a single lot, together with ‘un quart [i.e. a quarter share] dans les lettres de Crebillon; [et] une dans les lettres et romans de Boursault’ [‘a quarter [share] in the letters of Crébillon; [and] one in the letters and novels of Boursault].2 The contrast between the size of share-holdings in religious books and secular titles is revealing. Clearly the Imitation du Christ was a perennial religious blockbuster. It circulated in multiple translations and dozens of licenced editions, and it was so frequently counterfeited that on finding four editions in a single consignment, the authorities’ knee-jerk reaction was to assume that they were all pirated.

The success of the Imitation du Christ problematises the concept of a best-seller as it has emerged since the late nineteenth century, since it lacks many of the defining characteristics associated with the genre. The Imitation du Christ was not a new work, nor – since it first appeared on the eve of the print revolution – was it written for the commercial market.3 Neither was its success fleeting, and it cannot therefore be used as a barometer of passing trends or tastes. Instead, the stability of its sales, not just month on month or year on year, but also decade by decade and century by century, mark it out as something rather different, perhaps not so much fashionable reading as popular spiritual sustenance. These observations raise interesting questions about the appropriateness and value of applying the twentieth- and twenty-first century concept of a ‘best-seller’ to earlier historical periods. They should at the very least cause us to define our terms.4

The success of the Imitation du Christ is also disconcerting for historians engaged in the quest, initiated by Daniel Mornet’s seminal ‘Les Enseignements des bibliothèques privées, 1750–1780’ (1910), to uncover the best-sellers of the age of Enlightenment.5 For the Imitation du Christ was decidedly not a French enlightenment work, both because of its Christian piety and its antiquity. Moreover, the Imitation du Christ is merely the most striking example of a spiritual literature which had an enduring appeal throughout and well beyond the eighteenth century in France. For example, when book trade inspectors visited the premises of a dozen Besançon booksellers to stamp and thus legalise pirated books during an amnesty in August and September 1778, they stamped, on average, four pirated editions and 1,550 copies of another popular religious best-seller, L’Ange conducteur [The Guiding Angel], in each. They recorded ten editions at the premises of both Faivre and of Girard and 3,768 copies of twelve different editions chez la veuve Tissot. They stamped 5,275 further copies, comprising two freshly-printed editions, at Jean-Félix Charmet’s store.6 Whilst the number of copies circulating in the Franche-Comté, where the Ange conducteur was approved for diocesan use, seems to have been exceptional, across all eight chambre syndicale districts for which records survive in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, inspectors stamped a grand total of 25,686 copies of the Ange conducteur.7

Broadly similar numbers are recorded for another devotional work, La Journée du Chrétien sanctifiée par la prière et la méditation [The Christian’s Day Sanctified by Prayer and Meditation], with 17,509 copies stamped, and the Imitation du Christ with 20,378. Together with the Ange conducteur, they were most stamped works in the estampillage exercise records of 1778–1781. These three titles collectively accounted for over 15% of all stampings.8 Yet like the Imitation du Christ, both the Ange conducteur and the Journée du Chrétien were not enlightenment texts. The Ange conducteur was a work of baroque piety first published in 1681. Its unique selling point was the prayers to the believer’s guardian angel which accompanied each devotion, a feature which indicates it was intended more for private than liturgical use.9 The Journée du Chrétien, first published in 1754, was also a devotional work. For those enlightenment scholars who consider the Enlightenment a progressive, rationalist movement explicitly opposed to Christianity, such works contain the very antithesis of Enlightenment.

Given these introductory observations, this article sets out to do three things. First it will reflect upon the nature of the ‘best-seller’ and what historians hope to learn from counting them. Then it will consider the methods used by historians including the present author to uncover enlightenment best-sellers, and explore and reflect upon the results and value of recent digital surveys. Finally, it will explore the implications of these observations for our understanding of the print culture of the later eighteenth century.

Best-seller lists serve many purposes, but their insinuation into our lives and spending decisions has been driven by business imperatives. Since their emergence in the 1890s,10 lists of best-selling books have had two main commercial functions. First, they serve as a marketing tool, designed to stimulate interest in the latest and momentarily popular sounds or writings.11 At the same time, they are a stock control tool, indicating up-to-the-minute (or at least weekly) trends for time-pressed stock-buyers in swift moving markets, particularly in the days before electronic inventory tools and online megastores. In addition, many high street book stores still have displays of the weekly best-selling books prominent to attract and assist readers and influence their purchasing decisions.

Best-seller lists have further ancillary functions. Intellectually they help us to organise the way we view the world, telling us what is trending and what fellow readers consider important, interesting or entertaining. Hence ‘they offer us tantalizing glimpses of the common knowledge, shared tastes, inner lives and secret desires of our fellow beings’.12 Equally, for many consumers, best-seller lists impact their reading choices. Laura J. Miller tells of interviewing a British-born American reader who made clear that following best-seller lists in her reading made her feel ‘au courant’. The lists also operated, in that reader’s mind, as a quality control: she praised Americans as better readers that the British because ‘everyone’ read the best-sellers, whereas the British would read ‘just anything’.13 Furthermore, as Miller observes, best-seller lists are an object of fascination in their own right, speaking to and reflecting a Western obsession with ranking systems. Despite concerns in the industry that the methods used to compile best-seller lists reflect the interests of larger players in the trade and hence are not representative of the real state of the market, modern best-seller charts are widely consulted and enjoy a high degree of confidence. Both researchers and the wider public have often assumed that they are objective and reliable.14 The same might perhaps be said of historians and historical best-seller tables.

Of course, there were no best-seller charts in the long eighteenth century. Despite the anachronism, historians of Enlightenment have nevertheless found the idea of compiling best-seller tables to be beguiling. Whilst, as Martyn Lyons notes, we can only compile such lists ‘from indirect evidence’, our hope is that they will ‘provide an invaluable guide to popular preferences, and to the fluctuating tastes of an emerging mass consumer market.’15 The partial nature and biases of the sources are, however, an obstacle to getting to the ‘popular’ market, whilst ‘fluctuating tastes’ have proved difficult to track across anything but long time periods. Lyons own survey of early nineteenth-century France, where the records are generally richer and more complete than for the previous century, only breaks up his 35-year time period into five-year chunks. The analogue era work on the eighteenth century similarly offers a flat tableau covering longish time periods – Mornet’s foundational survey of 500 private libraries spanned the period 1750–1780, whilst Robert Darnton’s striking statistical tables of ‘forbidden best-sellers’ cover only 20 years of uneven and relate to only one Swiss publisher, the Société typographique de Neuchâtel (henceforth STN).16

Besides problems of temporality, taken in isolation, all the historical approaches used to study the circulation of books in the eighteenth century present methodological issues. In what remains of this article, I would therefore like to consider individual sources and approaches, and whether by bringing work on these different sources together, we can indeed get an indicative or general sense of the best-selling – or to be more precise, most widely circulating – books and categories of book in late enlightenment France.

Daniel Mornet’s work on private libraries is the traditional starting point for statistical attempts to reconstruct eighteenth-century reading. Undertaken at the dawn of the twentieth century, Mornet’s work was impressive in scale, taking in some 500 Parisian private libraries, and seemed to show the rich potential of library surveys. It also challenged existing pre-conceptions of the Enlightenment, arguing that many major works of the philosophes, particularly the religiously sceptical and politically radical, were found in relatively few libraries. Instead, Mornet recorded that Pierre Bayle’s Dictionnaire critique [Critical Dictionary], a pre-cursor to Enlightenment in its application of literary critical methods to Biblical texts, was the most frequently occurring work. It was present in 288 libraries. The next most popular works were Buffon’s Histoire naturelle [Natural History] (210 libraries) and the Henriade, an epic poem by Voltaire – who Mornet suggested was more appreciated as poet, historian and dramatist than as a philosophe. The Henriade celebrates the life of the perennially popular warrior King Henri IV, whose capture of Paris in 1589 (the main theme of the poem) and promulgation of religious toleration in the Edict of Nantes put an end to the French wars of religion: it was found in 188 libraries. However, Mornet’s most stunning discovery, at least to outward appearance, was that there was only one copy of the Jacobin Bible, Rousseau’s Du Contrat social [The Social Contract], in the 500 libraries surveyed.17 Later scholarship has shown that Rousseau’s other works, including editions of his collected works containing Du Contrat social (of which Mornet found 33 copies), circulated much more widely than this oft-quoted emblematic example suggested.18 It has also highlighted problems with relying on private libraries to trace best-sellers.

The most significant of these issues is temporal. Private libraries are typically built up over a period of several decades, and in many cases include legacy items inherited or bought from previous collectors. More positively, such older works as they contain may also reflect the strong trade in second-hand works across the enlightenment period, a commerce that according to David McKitterick, was more extensive than the market for new works.19 It is clear, then, that best-seller tables based on private libraries are problematic from a temporal point of view. The data on which they are based involves decisions and accidents around acquisition that occurred over many decades, and sometimes generations. Nevertheless, collectively they provide valuable insights for historians interested in medium to longue-durée trends around reading and print culture.

This is evident from the published findings of the most extensive survey of private library catalogues attempted since Mornet. Alicia Montoya’s European Research Council-funded MEDIATE database project tries to compensate for problems around legacy or vanity collecting, at least in part, by exploring only medium-sized libraries – typically those included in sales catalogues comprising 500–1,000 items. The theoretical underpinning for such a focus is that these libraries were likely to belong to serious readers from the middling orders, but contained few enough books that it could be assumed that many, most, or perhaps all, were for use and read in some way across the owner’s lifetime. Nevertheless, this method does not entirely negate a further issue: private library catalogues also generally reflect the holdings of socially elite collectors and bibliophiles, who may value a book for reasons other than content. There is also a possibility that vendors or booksellers held back or added volumes from other sources.20

MEDIATE currently draws its data from almost 580 such catalogues drawn unevenly across a period of almost 200 years and four countries (France, Britain, the Netherlands and Italy), and contains almost 500,000 items.21 Whilst inspiring in scope, this leads to an average coverage of only three catalogues per year surveyed, and less than one per country. Further, although the MEDIATE team were able to date both editions and the date of library sales, time lags made it impossible to chronologically nuance their data down to individual decades. For assessing collections containing late enlightenment works Montoya offers a single overview table of the leading enlightenment authors listed in catalogues dated 1790–1830. To produce best-selling tables over time, she divided the years 1670–1830 into 20-year swathes, again listing not works but authors by frequency of appearance. Her sample includes between 36 and 105 catalogues per 20-year period. In both cases Montoya’s tables were based on the presence of an author in a catalogue, rather than the absolute number of their books listed.

Such an approach, though uneven, proved revelatory. Although, as we might have expected, the composite authorial listing, ‘the Bible’, headed all eight of Montoya’s author rankings, classical authors otherwise dominate. Although their numbers thin over time, these writers still account for 16 of her top 30 in 1791–1810, and 15 out of 30 in 1811–1830.22 The MEDIATE project has thus shown, among other things, the enduring importance of classical authors, at least for that swathe of society which owned significant, but not excessive, numbers of books. This group were, of course, likely to be classically educated. According to Montoya’s overlapping professional categories, the library owners comprised lawyers and officials (22%), clergy (18%), scholars and educators (12%), arts and literature (6%) and medical professionals (6%), all of whom are likely to have studied Latin and the classics, and sometimes Greek. Only 13% of owners had backgrounds in industry, commerce, finance, or the armed forces, sectors where a classical education was less obligatory. In addition, the professions of 23% of the library owners are not known.23

Thus whilst the library owners in the MEDIATE survey may have represented a significant cross-section of the middle class elite and the occasional noble, it is open to question how far their enduring preference for classical reading and – as Montoya suggests – owning classical texts as material objects tied to the past, was shared by less educated and less wealthy readers.24 Despite its breadth and the nuance which computational analysis can bring, the MEDIATE survey on its own is not sufficient to help us to identify definitively the best-sellers of the period, especially within a single geo-political entity or shorter time periods, though it has highlighted that French provincial libraries were very different to the Parisian libraries in Mornet’s survey.25 What it does allow us better than any previous survey is to see the ownership preferences of avid readers and book owners within certain strata of society. It also reveals more than any other method the co-existence of new and older texts and editions in their libraries and perhaps their reading diets.

With the exception of the Bible, however, authors of ouvrages de piété (widely defined) are conspicuously absent from the MEDIATE 20-year rankings. It seems reasonable to assume for now that there is a fairly obvious reason for this. Most religious authors wrote in denominational and / or national religious traditions and had relatively limited markets beyond their denominational and / or national communities. Those that do appear in the listings had an international and inter-denominational appeal: Thomas à Kempis appears at no. 17 among authors on the 1751–1770 list, John Milton features in the lower levels of the 1751–1770 and 1771–1790 rankings, and Saint Augustine is at no. 24 in the table for 1670–1689. Another category of religious writer, the renaissance humanists Erasmus and Grotius also feature prominently in early decades. They rank ahead of all classical authors for the period 1671–1690, before gradually slipping from the tables over the following century. However, the significance of their presence is open to interpretation given their scholarly links to the classical past. Their prevalence, alongside the classical authors, Montoya argues, seems to support Dan Edelstein’s contention that the Enlightenment is an outgrowth or late form of civic humanism.26 But Montoya’s findings also reveal that by the 1790s, French enlightenment authors, notably Voltaire and Fénelon, followed at some distance by Montesquieu, Marmontel and Rousseau, were by far the most frequently encountered contemporary authors in the European private libraries catalogued by the MEDIATE project (see table one).

Table One: Top ranked francophone authors in private libraries surveyed in MEDIATE database, by presence in collections, 1790–1830.*

|

Ranking francophone authors |

Author name |

Ranking all authors |

|

1 |

Voltaire |

5 |

|

2 |

Fénelon |

7 |

|

3 |

Montesquieu |

22 |

|

4 |

Marmontel |

23 |

|

5 |

Rousseau |

30 |

|

6 |

Rollin |

32 |

|

7 |

Boileau-Despréaux |

35 |

|

8 |

Vertot |

40 |

|

9 |

Lesage |

41 |

|

10 |

Buffon |

46 |

* This table derived from MONTOYA. Enlightenment? What Enlightenment? p. 927.

Surprisingly, when MEDIATE changed the optic and produced national best-selling author tables by country based on edition-counts for editions published between 1769 and 1794 (a date range corresponding with the period when the STN traded), religious authors did not re-appear as we might have expected. In France there was only one religious author, ‘the Bible’ among their twenty most frequently encountered authors and in Britain just two (the Bible and John Milton). Yet classical authors disappeared, too: four remained on the French list, two on the British and none on the Dutch.27 Now it should be stressed here that counting by edition will produce different results from merely recording whether an author’s works were present in a catalogue. The former will tend to emphasise authors who were prolific more than the latter, which counts an author once regardless of whether one or many of their titles were present in an individual library. Nevertheless, the MEDIATE results are both striking and puzzling: they may indicate a cultural gulf between the classically-educated mainly urban elite owners of the private libraries in the database and a wider society where religious titles were being consumed in large numbers. They may also reflect the prevalence of national literatures within the catalogues drawn from each country and the fact that the most popular classical authors penned at most only a few extant works.

Given the social status of the owners of catalogued private libraries, historians have used many other sources to try to gauge book ownership and popular reading habits in past societies. One of the most promising has seemed to be records of books from will inventories. By the eighteenth century, as Daniel Roche has shown, books were being left by people well down the social scale, reflecting relatively high levels of literacy. In his sampling of Parisian inventories dating from 1750 to 1790, Roche found that 22.6% listed books, including, by 1780, around 35% of labourers’ and 40% of domestic servants’ wills.28 Roger Chartier found an even higher incidence of ownership in large provincial centres such as Nancy, Angers, Caen, Nantes, Rennes and Rouen, in each of which 33–36% of legatees left books.29

Roche’s work might be more socially inclusive than the MEDIATE approach, but it also has limitations, especially as many libraries are not fully itemised. Thus whilst Roche’s statistics of book ownership are quantitative, his descriptions of literary culture tend to be qualitative. It is also not clear whether people who left wills are the exceptions rather than the rule, nor whether will inventories record all books – or sorts of books – owned by the deceased? This issue is highlighted by rival approaches to the presence of religious books in the Franche-Comté. Surveys of will inventories by Michel Vernus found that 6% of peasants bequeathed books, though they very rarely owned more than half a dozen, and frequently only one. Moreover, most of these books were religious texts: religious reading was found in 80% of peasant ‘libraries’, and in the majority of cases was the only genre present.30

However, these numbers seem inconsistent with the volume of religious works held by the booksellers of Besançon in 1778, as noted above. The Besançon evidence suggests that the most popular works of private devotion, including the Ange conducteur, were reaching one household in three across the region, an incidence six times greater than suggested by Vernus’s survey.31 This hints that best-seller tables based on private library surveys and will inventory evidence may be critically under-reporting religious books. It also raises questions about what else these surveys might miss, including other cheap genres of print such as textbooks, chapbooks, pamphlets, the bibliothèque bleue and other literature of colportage, as well as illegal books or practical manuals such as accounting tables, popular medical texts, and cookbooks, which may have been stored apart from other books in their places of use.

These concerns and the contrasts between surveys hint at the advantages of conducting a supply side approach to discovering which books were in circulation. This approach was pioneered by Robert Darnton in Forbidden Best-sellers of Prerevolutionary France (1996), his award-winning study of the STN’s clandestine book trade with France. Technically, Darnton did not study supply at all, since he drew his statistical data from the orders booksellers placed by mail order with the STN, regardless of whether the STN could fulfill them, or the books reached their intended destinations. However, he argued that generally supply and demand married up pretty well, since the STN drew its stock through an international network of publisher-wholesalers across a ‘fertile crescent’, stretching from Belgium and the Netherlands through the German Rhineland to French-speaking Switzerland. These publisher-wholesalers could generally supply almost any popular title published anywhere across the continent. Thus its trade and the STN’s best-seller list could be considered broadly representative of the wider French clandestine book trade. According to Darnton this illicit trade in so-called livres philosophiques [philosophical books] was enormous.32

Darnton’s Forbidden Best-sellers list was thus explosive. It found that although the STN catalogue contained numerous works by the philosophes, their best-sellers list was headed by very different material. At its pinnacle were Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s futuristic utopian Rousseauistic thought-experiment L’An 2440 [The Year 2440], in which a Parisian awakes in a morally perfected future, and Mathieu-François Pidansat de Mairobert’s Anecdotes sur Madame la Comtesse du Barry [Anecdotes about Madame the Countess du Barry], a scandalous biography recounting a royal mistress’ rise through the Parisian demi-monde from shop-girl to royal bed.33 These two works Darnton abridged and anthologised, together with the title at number 15 on his best-seller list, Thérèse philosophe [Theresa the philosophe], a salacious novel in which the central protagonist undertakes a sexual and intellectual voyage of discovery. Splicing together pornographic and materialist philosophic interludes, and linking them to a real-life scandal involving a priest deflowering one of his pénitentes through spiritual deception, Thérèse philosophe is sensational material.34 Darnton’s Forbidden Best-sellers thus offered an alternative view of Enlightenment, where progressive or cutting-edge ideas were embedded in a literature of sex and political and religious scandal which sapped the old regime at its foundations, desacralising both throne and altar. Hence in Darnton’s telling, these illegal best-sellers contributed to the moral and political collapse of a regime which had ‘lost its legitimacy’.35

But to what extent can these ‘forbidden best-sellers’ be considered best-sellers at all? Darnton’s argument derives much of its force from his decision to concentrate in texts not authors. Had he concentrated on his authors’ list he would have presented a much more traditional view of Enlightenment. That list is headed by Voltaire, who due to his prolific output accounted for approximately 12% of books ordered in Darnton’s sample, and perhaps more surprisingly, the arch-materialist d’Holbach ‘(and collaborators)’, who accounted for a further 10%. Three other leading philosophes (Raynal, Rousseau and Helvétius) and the arch-anti-philosophe Simon-Nicolas-Henri Linguet are also in his top ten. Collectively these six authors account for almost a third of all orders in Darnton’s sample.36

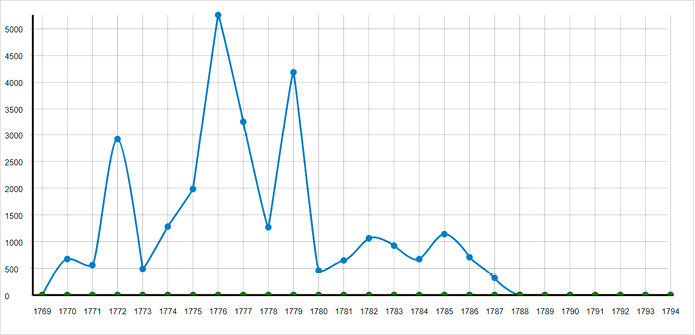

A further set of issues with Robert Darnton’s data have been raised by the ‘French Book Trade in Enlightenment Europe’ (FBTEE) project, which between 2007 and 2012 created an award-winning online database of the entire trade of the STN using their surviving accounting records.37 Whereas Darnton’s survey covered 3,266 orders sent to the STN for 28,212 copies of libertine books from a sample of 63 French bookdealers, the STN database records sales of 413,710 copies and acquisitions (including printings) for 445,496 books in all genres in 70,584 ‘transactions’ across a network of 2,895 correspondents distributed across 512 European towns. The first issues raised by the FBTEE database are problems of temporal bias.38 Although Darnton’s appendices are entitled The Corpus of Clandestine Literature in France, 1769–1789, the vast majority of commercial sales of books in his libertine corpus to France took place in the five-year period 1774–1779, together with an initial surge in 1772 caused by sales of the STN’s edition of Voltaire’s Questions sur l’Encyclopédie [Questions concerning the Encyclopédie].39 This becomes evident when we graph total French STN sales of books in his corpus by year (see fig. 1). Further, the STN archives indicate that following a set of decrees on the book trade on 30 August 1777, which gave significantly more bite to local inspection regimes, most STN clients retreated from the libertine sector.40 This collapse appears to be discernible in the Parisian confiscation registers, too, and can be confirmed in the FBTEE database.41 After 1777, only two STN clients in France continued to deal in pornographic works: the STN dumped a large consignment of otherwise unsellable libertine books on one of them in 1779 (which explains the blip in 1779 in fig. 1).42 If these clients are excluded, the bulk of the STN data relates to the period up to 1777 and editions produced in or before that year.

Figure 1. Sales of books in Darnton’s Libertine Corpus to France by the STN (not including author-commissioned works)

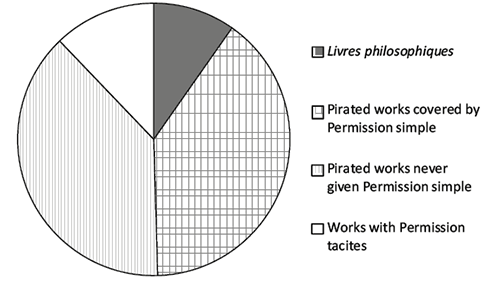

Equally, Darnton’s Forbidden Best-sellers tables reflect a very niche area of the illegal book trade. Although perhaps half of all books sold in late ancien régime France were ‘illegal’ in some way, very few were ‘libertine’ books.43 Instead, the typical illegal book was a pirated religious work, most likely a liturgical or devotional title, such as the Ange conducteur or Imitation du Christ. Less than 10% of clandestinely traded books by volume were libertine titles of the sort that comprised Darnton’s corpus of clandestine books (see fig. 2).44 Within that corpus, only a small minority were the sort of anti-clerical, materialist, scandalous or pornographic titles on which Darnton’s argument set so much store.

Figure 2. The structure of the French illegal and quasi-legal book trade, 1769–1789 (excluding unlicensed innocuous works).

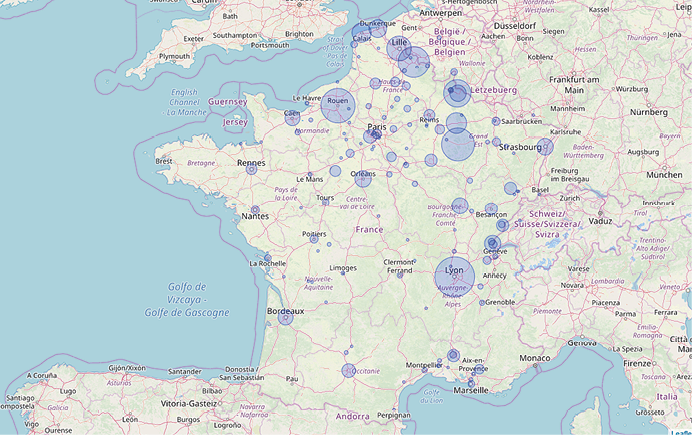

Finally, the STN database revealed that the STN data was far less representative than the FBTEE team and Darnton before them had assumed.45 Indeed, analysis run through the STN database has called into question almost every assumption on which Darnton’s argument for the wider significance of the STN rests. Mark Curran insists that the STN’s clients generally ordered from their trade catalogues, and only a very few gullible or inexperienced dealers demanded anything else, since they knew it would not be supplied.46 Nor did the STN generally attempt to supply everything from everywhere. Curran highlights that two-thirds of the books the STN sold were its own publications, and the bulk of the rest were Swiss editions.47 Likewise, what the STN traded or chose to supply was determined largely by the legal framework in which it operated. For example, after early run-ins with French customs and local authorities in Neuchâtel they eschewed publishing hardcore atheism or pornographic works.48 Louise Seaward has shown, moreover, the extent to which the STN negotiated to get their books permitted inside France (something that would not have been necessary had the borders been as open as Darnton originally argued).49 This is something Darnton now tacitly acknowledges: the STN’s trade negotiations with the authorities of Versailles are a major feature of his most recent book.50 Finally, the market for illegal books was less integrated than Darnton’s argument requires, as becomes clear when we map the origins of books confiscated by customs in Paris (see fig. 3). There was in fact very little merchandise coming from the German Rhineland.51 Far from providing evidence of a ‘fertile crescent’ of French publishing centres stretching from the Low Countries to Swiss Romandie, this map supports Mark Curran’s contention that the publishing worlds of the North were largely separate from the South, and tended to produce different fare.52 All these considerations weaken the case for considering most of Darnton’s Forbidden Best-Sellers to have been genuine best-sellers.

Figure 3. Point of entry into French postal system of consignments of books confiscated by Parisian customs, 1769–91.* The size of the dots is scaled to number of consignments.

* The map plots the places where consignments of books were recorded to have entered the French postal system, which for consignments from abroad meant an authorised frontier post. The source data for the map is the Confiscations Registers (BNF, MS Fr. 21,933-21,934), which were then cross-referenced against the Customs Registers (MS Fr. 21,914-21,926) and register of confiscated works at MS Fr. 21,935.

In exploding its own foundational assumptions, the FBTEE project appeared also to undermine its vision of drawing up ‘representative’ best-seller lists for every year and the various states, provinces and towns of old regime Europe. If the STN was really a parochial Swiss publisher awash with Swiss stock, its wider significance in the Enlightenment seemed limited. This was the underlying message of Mark Curran’s study of the STN, Selling Enlightenment. Yet as a digital project, FBTEE could compensate for these biases by changing its optic – in particular it could filter its data to reduce known biases. By excluding works known to have been published by the STN itself, which accounted for two thirds of the books (units) it sold, FBTEE could produce ‘best-seller tables’ of livres d’assortissement or marchandise générale, the general stock it had bought in from other publishers in Switzerland and beyond.53 About a quarter to one third of this marchandise générale came from beyond Switzerland.54

Table 2: STN commercial best-sellers in France, 1769–1794*

|

Rank |

Author |

Short Title |

Copies |

|

1. |

[Bible] |

Pseaumes |

2,141 |

|

2. |

Mairobert |

Anecdotes sur Madame du Barri |

954 |

|

3. |

Mercier |

L’An 2440 |

904 |

|

4. |

[Bible] |

Le Nouveau Testament |

589 |

|

5. |

Aretino |

Histoire et vie de l’Arrétin |

545 |

|

6. |

Berquin |

Lectures pour les enfans |

542 |

|

7. |

J.-R. Ostervald |

Nourriture de l’âme |

493 |

|

8. |

Voltaire et al. |

Lettre philosophique |

486 |

|

9. |

Cleland |

La Fille de joie |

468 |

|

10. |

Gottshed |

Maître de la langue Allemande |

444 |

* This table excludes all STN editions including commissioned and joint editions. One further work has been deleted from the table, as close interrogation of the data suggested that most copies of the Collection complète des oeuvres de M. Dorat sold by the STN appear to have been their own edition.

The resulting table of the STN’s ‘commercial’ best-sellers to France (table two), based on 47,504 sales of their marchandise générale, is deeply suggestive, despite its known chronological biases and relatively flat structure (only the top two works accounted for over 2% of total sales). First, it reaffirms that as a retailer-wholesaler of other publishers’ works, the STN did indeed until the late 1770s, as Darnton suggested, specialise in highly illegal libertine works. This is evident from the presence of Darnton’s two leading ‘forbidden best-sellers’, the Anecdotes sur Madame du Barry and Mercier’s L’An 2440, in second and third spot on the table, but also from the presence of pornographic classics L’Histoire et vie de l’Arretin [The Story and Life of [Pietro] Aretino] and John Cleland’s Fille de joie [i.e. Fanny Hill] in the top ten. In all, at least fifteen erotic works feature in the top fifty titles on the list, almost all of them pornographic or sexually libertine texts. Equally, religion is prominent, with two works of scripture, the Pseaumes [Psalms] and Nouveau Testament [New Testament] in the top ten, as well as Nourriture pour l’âme [Nourishment for the Soul]. However, only two other explicitly religious works, the Bible and a prayer book appear in the top fifty. As Protestant books, these, too, were technically illegal in France and the huguenot market that they served there was small. Their sales tell us little about the market for popular religious works among French Catholics. The STN’s top ten also contains precious little philosophie, with the exception of the Lettre philosophique, an anthology containing pieces by Voltaire and others, which should not be confused with the great philosophe’s more famous Lettres philosophiques. However, just off the list are Rousseau’s Oeuvres (416 copies) and Raynal’s Histoire philosophique et politique des établissemens et du commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes [Philosophical and Political History of the Colonies et Commerce of the Europeans in the two Indies] (441 copies). The latter ran through multiple versions and numerous editions in the 1770s and 1780s and is now widely recognised by historians for its significance, though not everyone shares Jonathan Israel’s conviction that it was the book that ‘made a global revolution’.55

Table 3: Event counts for authors in MPCE database, covering 1769–1790

|

Rank |

Primary Author |

Event count (n. = 18232) |

|

1 |

Voltaire |

332 |

|

2 |

Bible |

271 |

|

3 |

Jacques Coret |

131 |

|

4 |

Thomas à Kempis |

120 |

|

5 |

Jean-Jacques Rousseau |

78 |

|

6 |

Denis-Xavier Clément |

77 |

|

7 |

François Bertrand Barrême |

74 |

|

8 |

Jeanne-Marie Le Prince de Beaumont |

71 |

|

9 |

Louis-Sébastien Mercier |

64 |

|

10 |

Claude Fleury |

63 |

|

11 |

Samuel Tissot |

62 |

|

12 |

Albrecht Haller |

57 |

|

13= |

Claude-Joseph Dorat |

56 |

|

13= |

Pierre-Hubert Humbert |

56 |

|

15 |

Jacques Bossuet |

54 |

However, a different story emerges when we combine all items of merchandise générale by the same author to create a best-selling authors’ list for France. Similarly to Darnton’s author table, this list is headed by Voltaire, who accounted for almost 11% of sales, and the Bible (6.33%). They are followed by the Swiss doctor and author of popular medical treatises, Samuel Tissot (3.16%). Next on the list come Mairobert, Mercier, d’Holbach, Marmontel, Berquin, La Fontaine and Salomon Gessner, followed by Montesquieu, Fénelon, J.-R. Ostervald and Rousseau. Philosophie is much more in evidence on this composite list and erotica much less. Moreover, with the exception of d’Holbach, the five figures on this list who are generally considered to be enlightenment philosophes, that is to say Voltaire, Marmontel, Montesquieu, Fénelon and Rousseau, also occupied five of the top six ranks in MEDIATE’s table of francophone authors appearing in private library catalogues between 1790 and 1830 (the sixth on the MEDIATE list was Diderot). This appears a significant finding. When it comes to measuring the dissemination of enlightenment authors, the MEDIATE and STN databases mutually reinforce each other.

Because of doubts about the representativeness of the STN data, the FBTEE project has since 2013 been gathering and compiling into a new database further data from a range of other French book trade sources. This endeavour has been underpinned by funding from the Australian Research Council for a follow-on project entitled ‘Mapping Print, Charting Enlightenment’ (MPCE). A new MPCE database currently contains 18,212 discreet records on four different types of event. There are 10,186 sales records relating to titles sold at stock sales for bankrupt or deceased Parisian booksellers between 1769 and 1787; 3,489 records of confiscations at Parisian customs between January 1770 and (currently) 19 July 1785; 2770 records of pirated titles being stamped during the estampillage exercise and pirate amnesty of 1778–1781; and 1767 records of print-runs licenced under the permission simple between 1777 and 1790.56 Altogether these records relate to over three million books.

The MPCE database contains very different datasets, but cumulatively they cover most sections of the book trade. They include the Parisian and the provincial; the licit and the clandestine; the licenced and the pirated, the domestic and the international. The permission simple licence covered works thought popular enough that French publishers were prepared to pay a small fee to the privilège holder, implying also that before 1777 they would probably have been pirated. The estampillage records reveal which works were circulating in pirated editions in the period 1778–1780 for eight of France’s twenty Chambre syndicale districts. The similarity between the works topping the ‘best-seller lists’ for the estampillage and permission simple records strongly suggests that these records indeed capture the pirate publishing sector effectively. The Parisian stock sales records, by contrast, capture the legal sector controlled by the major Parisian publishers, who held a stranglehold and privilèges over much of the legal trade in books. Finally, the confiscation registers, which record all titles suspended by customs during their twice weekly inspections, give insights into several sectors of the trade. They contain confiscations of the heavily illegal works in Darnton’s Corpus, and pirated editions, but also often new works (nouveautés) suspected of lacking a formal permission or trafficked en nombre to individuals who were not licenced to sell books. This final dataset, it should be noted, was incomplete at time of writing – 500 consignments of confiscated books covering the period 19 July 1785 to 1791 had yet to be added.

Counting the number of times individual authors or works appear in such a heterogenous yet broad-ranging selection of datasets, provides further indicative insights into some of the most circulated texts in France in the two decades before the revolutionary crisis (see table three). Not surprisingly, such a list is headed by Voltaire and the Bible, followed by Jacques Coret, author of the Ange conducteur, Thomas à Kempis, author of the Imitation du Christ, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The top ten ranks are rounded out by Denis-Xavier Clément, author of the Journée du Chrétien; the mathematician François-Bertrand de Barrême, author of Le Livre des comptes faits [The Book of Accounts Completed] a set of accounting tables essential to any business; the educationalist and writer of fairy tales, Madame Le Prince de Beaumont; Louis-Sébastien Mercier; and the ecclesiastical historian and royal tutor Claude Fleury. Fleury’s patrons and associates Bossuet and Fénelon appear in 15th and 34th position on the same list. All these authors appear across multiple datasets.

This list is interesting in several ways. First, of the ten leading authors listed, only five were alive in 1771, and four of those were dead by the end of 1780 (Clément died in 1771, Rousseau and Voltaire in 1778; and Le Prince de Beaumont in 1780). Only Mercier lived to see the French Revolution of 1789. Of the other five ‘authors’, the Bible represents a collection of known and unknown ancient writers; Thomas à Kempis wrote in the mid-fifteenth century; Barrême, Fleury and Coret all produced their key works in the late seventeenth century. As with the MEDIATE list, popular authors do not generally seem to have been keeping readers ‘au courant’. The MPCE rankings diverge from the MEDIATE list, however, due to the marked presence of non-Biblical religious writers rather than classical authors (‘the Bible’ is the dominant religious work on both lists). In distinct contrast with the MEDIATE rankings, the highest ranked classical author, Cicero, only makes 33rd position, with Horace coming in at equal 34th. If we changed our optic from authors to works, the dominance of religion would seem all the more apparent. Eight of the top ten works were religious, headed by the Ange Conducteur (134 events), Imitation du Christ (121), Journée du Chrétien (89) and Pseaumes (66).

Nevertheless, enlightenment philosophie is also present in the MPCE author table, in the persons of Rousseau and Voltaire. Their overarching popularity confirms the insistence of tradition historiography that for the revolutionary generation they were, even before 1789, the personification of the Enlightenment. No other philosophe made the top 20, although several others were ‘bubbling under’, notably Montesquieu at number 21, Marmontel (#22), Raynal (#24), d’Holbach (#28) and Fénelon (#34=). This grouping of philosophes is almost identical to the leading seven philosophes in the STN database rankings (Raynal is pushed into eighth position in the FBTEE ‘commercial’ rankings by Jean-François Saint-Lambert, but this is because most of the STN’s sales of the Histoire philosophique et politique des deux Indes were their own edition). More significantly, the top five francophone authors on the MEDIATE 1790–1830 rankings all feature among the MPCE cluster of seven top enlightenment authors. Finally, the presence on the MPCE list of Barrême, and of the medical populariser Samuel Tissot (#11) as well, perhaps, the polymath anatomist, poet, romancer, botanist and natural scientist Albrecht von Haller (#12), reflects the importance of books that aimed to address the everyday needs of readers, whether for health advice or practical mathematics for business.

Despite their striking overlaps in terms of enlightenment authors, the discrepancies between the MPCE list and the MEDIATE lists are also worthy of reflection. MEDIATE seems to have produced a more cosmopolitan list reflecting the reading among the middle orders of society – the group generally seen as the drivers of Enlightenment. But their published library catalogues seem not to have contained devotional literature and apparently self-help texts such as Barrême’s accounting tables, and in all probability many forms of text book (though perhaps not classical texts produced for classroom use, which may have been valued and saved long enough to feature in the catalogues). But neither the STN database nor the MPCE database picked up more than a whisper of the volume of classical texts circulating among urban elites, as revealed by the MEDIATE project. What still remains unclear is whether this was because local markets could sustain production, diffusion and turnover levels sufficient that these books did not pass through wholesale trade networks, or because the libraries studied by the MEDIATE project represented only a narrow elite. Alternatively, cheap editions of self-help books, mathematical tables, or works of popular piety did not feature in the MEDIATE corpus because they lacked commercial value. For as Rindert Jagersma points out, private library auction catalogues, which make up the bulk of the MEDIATE sample, were designed to ‘sell the profitable books for as much profit as possible’.57

Given the difficulties of source-based methods, some historians have considered edition counts might be a more suitable proxy for book circulation. This approach has been facilitated by the advent of global collective research library database search engines, notably Worldcat, or for more sophisticated users, the Carlsruhe portal.58 The effectiveness of such an approach is based on two assumptions. First, it assumes that most editions, at least of the more popular works, are preserved somewhere in the world’s research library collections. This may be warranted for certain genres of eighteenth-century works, or luxury formats, but across the entire print record it is problematic.59 Whilst most editions of novels found in book trade sources consulted for the FBTEE project survive, often in multiple copies, in the world’s research libraries, the same is not true of text books, the accounting manuals and mathematical tables essential to most eighteenth-century small businesses, popular pamphlets and ephemera, or liturgical and pious works. For example, of 46 editions of the Imitation de Jesus Christ granted permits in the Permissions simple registers, FBTEE researchers were unable to locate 39 in Worldcat. Likewise, of 32 authorised permit editions of Barrême’s Livre des comptes faits, only nine were found.60 Most tellingly, just 21 editions of the Journée du Chrétien dating from between 1754 and 1848 were identified in Worldcat, whereas the permission simple records suggest 73 licenced editions were printed in France alone in just a dozen years between 1778 and 1790.61 If production was constant across the century c.1750-1850, this suggests that Worldcat contains only around 3% of editions of the Journée from this period, and even this may be an over-estimate, given that some editions were produced outside France.

The second assumption, likewise problematic, is that print runs for individual editions were roughly constant over time and between genres. Although Mornet drew attention to this issue, historians and bibliographers have frequently assumed print runs of around 1,000 were usual, in part due to technical limits. For genres such as novels and more academic works this may not be unwarranted, though 500–1000 seems more likely.62 However, small format religious works, accounting manuals and school textbooks seem to have printed habitually in much larger numbers. The 32 permission simple licences for the Livre des comptes faits authorised a total print run of 69,000, with an average of almost 2,250 copies per edition, whilst the 46 editions of the Imitation de Jesus Christ had 75,800, or just under 1,750 copies per edition. Similar, and often higher average print-runs were found across other religious works. Typical textbook print-runs for the STN, derived from incomplete data, included 4,000 copies of an edition of the Abrégé de l’histoire sainte et du catéchisme [Abridgement of the Sacred History and the Catechism], 3,000 for their third edition of Frédéric-Samuel Ostervald’s Géographie élémentaire and similar numbers for the third edition of his Cours abrégé de géographie historique, ancienne & moderne, et de sphère: par demandes et réponses [Abridged course of ancient and modern historical geography and of the globe: by questions and answers].

Taken in combination, these findings suggest that edition counts may drastically under-represent the production of genres such as pious and liturgical works, technical manuals and self-help books or textbooks – works generally produced in cheap and flimsy formats – in comparison to genres such as novels, histories, scientific works or philosophy, which were usually produced in more durable formats and valued by librarians and collectors. If, as the permission simple evidence suggests, around 80% of editions of pious and liturgical works, technical manuals, self-help books and school books are lacking from our research collections, and print runs for such editions were generally double or more those of other genres, studies based on edition counts may well under-estimate the number of copies these genres by 90% or more in comparison with novels, histories, philosophy and scientific works. In the case of the Journée du chrétien the figures derived from counting editions might possibly understate real production by as much as 98–99%.

Whilst these figures are striking, they do not to invalidate studies based on edition counts, per se. If surveys of editions confine themselves to individual genres, or ones where we might assume that print runs were broadly comparable and survival rates of editions consistent, the best-sellers’ tables that such studies produce can be highly suggestive. This would be true, for example, of the work of Gary Kates and a team of his students, which set out to explore the dissemination of Enlightenment by conducting an edition count of fifty major enlightenment texts. These included some of the underground texts highlighted by Robert Darnton’s work as well as the traditional enlightenment canon. The count extended to eighteenth-century editions identified in any European language.

In some ways, the findings of Kates and his team set the historiographical pendulum back by two or three generations, as they highlight the prevalence of political works, particularly moderate constitutional texts, written in the first half of the long-eighteenth century. Their figures reinforce the central importance of politics and history to enlightenment publishing, emphasising the role of Montesquieu, but they also reveal the supreme significance of Fénelon’s Aventures de Télémaque [Adventures of Telemachus], first published in 1699. Télémaque went through around 450 editions, more than 50% more than any other work in Kates’s pre-defined corpus. Remarkably, only six other works had edition counts above 100. Three of these were by Montesquieu,63 along with Robertson’s History of Charles V, Voltaire’s Histoire de Charles XII and, in second place, on 284 editions, Madame de Graffigny’s political novel of the conquistadors, Les Péruviennes [The Peruvian Women].64

Across the century it might thus appear that Fénelon, a champion of monarchie tempérée, produced the Enlightenment’s number one best-seller. Tellingly, Alicia Montoya’s team also identified Fénelon as the most frequently encountered enlightenment author in their sampling of library catalogues. His works were recorded in 53% of catalogues in the MEDIATE database. However, he ranked only 19th among all authors in her survey, behind the Bible, Erasmus, Grotius and fifteen classical authors.65 In part, of course, Fénelon’s standing is due to his life dates: Télémaque, for example, was published in 1699, so could potentially feature in most of the libraries surveyed by the MEDIATE project. This was not possible for those ‘enlightenment classics’ that were first published after 1750. However, this only serves to make his ranking behind so many classical authors all the more striking. On this evidence, canonical enlightenment texts seem to have been relatively marginal to the reading fare of many eighteenth-century readers. Further, the prevalence of writers like Fénelon and Montesquieu supports Annalien de Dijn’s claims that the Enlightenment was neither politically or religiously radical nor the harbinger of either radical secularism or democratic political modernity.66

What then can we draw from these contrasting attempts to produce best-seller and frequency tables, and their striking disparities and equally surprising overlaps? First they serve to reinforce the importance of using more than one type of source, approach, or optic. All the methods described here contain pitfalls for the unwary, whether Darnton’s ‘20-year’ snapshot of STN orders; MEDIATE’s author frequency tables; FBTEE’s database of STN transactions or counting of heterogenous events in the MPCE database; and the Kates’ team’s counting editions. However, through skilful construction of queries, the database projects described here can be weighted or filtered to remove biases or bring out chronological or geographic nuance. Third, when compared, there is a remarkable congruence between rankings for enlightenment authors in the MEDIATE, MPCE, STN and Kates databases. This does not extend to other genres, such as religious and classical authors/works, where FBTEE/MPCE and MEDIATE methods each provide unique insights.

Thus although the quest to find ‘enlightenment best-sellers’ is anachronistic and, except in very specific contexts (such as the STN data), we may never be able to calibrate ‘weekly’ or even ‘annual’ best-sellers’ tables, these attempts have had valuable collateral benefits.67 They have, for example, revealed the impact of measures to control the book trade in 1777, and helped us to contextualise, quantify and map the clandestine and pirate trades in particular, and to draw important international comparisons. Moreover, however hazily, a picture of the consumption of print culture in eighteenth-century Europe is emerging that has the potential to change perspectives on the Enlightenment. Religious texts appear to have been produced in much greater numbers than once thought and on a scale that in eastern France, and presumably elsewhere, may challenge prevailing ideas of reading literacy levels, and popular reading, and hint at the existence of a previously unsuspected widespread Roman Catholic book-based piety in the later Enlightenment. But equally MEDIATE provides compelling evidence for the longevity and popularity of classical authors among the mostly urban elites who owned medium-sized libraries. This came as a surprise, even though historians have long been aware of the way that the French revolutionary generation of politicians steeped their rhetoric, actions and even their costume in classical allusion. Among consumers of enlightenment texts, it is now clear that the most popular class of texts were moderate monarchist treatises such as Fénelon’s Télémaque or the works of Montesquieu. Collectively Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Marmontel and Fénelon appear to have been the most read French enlightenment authors both in France and north-western Europe more generally. However, the spear carriers for Israel’s radical enlightenment, d’Holbach, Diderot and Raynal also emerge as significant in the final twenty years before the French revolution.68 In contrast, the kinds of sexually salacious and desacralising works described by Darnton were, at most, a relatively marginal part of an illegal sector dominated by piracies of innocuous works, many of them religious best-sellers. Further, in France, where these works supposedly did most damage, the heyday of the libertine book trade was brought to an end a decade or more before the revolution.

Of course, none of the digital projects discussed here has yet linked the bibliometric data to evidence on how readers responded to specific texts.69 Indeed, understanding reader response remains a major challenge in book history (as indeed in cognitive and educational science), as well as an area ripe for further exploration by digital methods. In the analogue era, scholars tended to rely on isolated or highbrow sources, such as printed reviews by academically-minded literary reviewers or the equally atypical reading journals or common-place books of diarists like Samuel Pepys or the Sheffield apprentice Joseph Hunter.70 This material was frequently hard to locate: Robert Darnton’s seminal article on reader responses to Rousseau was based on just two readers.71 To date, the most valuable digital attempts to explore historical reader response remain the Reading Experience Databases (REDs) that exist for several, mainly English-speaking countries. These projects depend largely on volunteer crowd-sourced labour to capture and analyse examples of reader experience, using complex online data-entry forms to capture structured data on details such as the time of day, location, social context and postures in which acts of reading took place, as well as readers’ critical responses to texts.72 This labour-intensive, comprehensive, data-rich approach has proved hard to sustain and has generally been biased towards the experience of the most voracious readers. However, other approaches, which harvest existing digital resources, are possible, and this is particularly true for the field of eighteenth-century studies, which boasts a number of fabulous digital resources, including Oxford University Press’s ‘Electronic Enlightenment’ and Gale-Cengage’s ‘Eighteenth-Century Collections Online’ (ECCO), whose publishers are keen to collaborate with academic researchers. With the proliferation of digitised sources, the harnessing of optical character recognition (OCR) technology, and the application of machine learning and sentiment analysis techniques, locating and harvesting the scattered traces of past reading experiences is increasingly feasible, and the potential sources extensive. They include published book reviews; private correspondence; manuscript newsletters; reading journals; accounts of reading in fictional and non-fiction works; footnote citations and commonplaces which cross reference texts and are already an object of digital study;73 readers’ marginal annotations; school exercise books and university essays; publishers’ correspondence; censorship records; police spy reports; court, police and inquisitorial records. The MEDIATE and MPCE teams and their collaborators are already discussing ways to capture these forms of information and link them to their bibliometric records in order to show in more systematic ways than hitherto just how readers responded to texts.

Nevertheless, even before integrating reader response evidence, the bibliometric evidence is already suggesting important revisions to the enlightenment narrative. Comparing the frequency and ‘best-seller’ lists discussed here is fraught with difficulties and peril, especially as they do not compare like with like, and some are more nationally focussed than others. However, particularly when it comes to the French enlightenment canon, the tale they tell is remarkably consistent. Furthermore, that story calls into question Darnton’s influential assertion that the enlightenment canon was a scholarly creation of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, together with its corollary that historians should concentrate their efforts on building ‘a literary history from below’.74 When all is said and done, any survey of French enlightenment print culture – and enlightenment culture more generally – needs to begin by acknowledging and reflecting upon the ubiquity of the Bible and pious works with inter-denominational appeal, such as the Imitation du Christ; the enduring popularity among urban and aristocratic educated elites of the canonical works of classical antiquity and renaissance humanism; and the undeniable preference of enlightened readers for political writings by moderate authors of the enlightenment canon, together with the voluminous writings of Voltaire, the inescapable King of the philosophes. On one level, this may not seem very surprising, but to identify these three corpora as our big stories runs contrary to much of the scholarship of the last four decades, including the aforementioned attempts to construct literary histories from below, explore radical Enlightenments, or move away from a predominantly political view of enlightenment thought. It also points to hitherto unsuspected levels of religious commitment, engagement with classical learning, and devotion to tempered monarchy right down to the eve of the French Revolution. Based on the bibliometric evidence, it would have been hard to predict the coming storm.

Reference list

BURROWS, Simon. Charmet and the Book Police: Clandestinity, Illegality and Popular Reading in Late Ancien Régime France. French History and Civilization, 2015, t. 7, p. 34–55.

BURROWS, Simon. The French Book Trade in Enlightenment Europe II: Enlightenment Best-sellers. London: Bloomsbury, 2018. ISBN 9781441182173.

BURROWS, Simon. The Geography and Control of the Clandestine Book Trade in France, 1770–1789. French History and Civilisation, 2021, t. 10, p. 53–69.

BURROWS, Simon and FALK, Michael. Digital Humanities. In FROW, John; BYRON, Mark; GOULIMARI, Pelagia; PRYOR, Sean (eds.). The Oxford Encyclopaedia of Literary Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, online version 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.971.

CHARTIER, Roger. Book Markets and Reading in France at the End of the Old Regime. In ARMBRUSTER, Carol (ed.). Publishing and Readership in Revolutionary France and America. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1993, p. 117–137. ISBN 9780313287930.

CHARTIER, Roger. Lecture et Lecteurs en France d’Ancien Régime. Paris: Seuil, 1987. ISBN 9782020094443.

COLCLOUGH, Stephen M. Procuring Books and Consuming Texts: The Reading Experience of a Sheffield Apprentice, 1798. Book History, 2000, t. 3, p. 21–44.

CURRAN, Mark. The French Book Trade in Enlightenment Europe I: Selling Enlightenment. London: Bloomsbury, 2018. ISBN 9781441111692.

CURRAN, Mark. Beyond the Forbidden Best-sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France. Historical Journal, 2013, t. 56, p. 89–112. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X12000556.

DARNTON, Robert. The Business of Enlightenment: A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1979. ISBN 9780674087866.

DARNTON, Robert. The Corpus of Clandestine Literature in France, 1769–1789. New York and London: Norton, 1995. ISBN 978-0393332674.

DARNTON, Robert. The Forbidden Best-sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France. New York and London: Norton, 1996. ISBN 978-0393314427.

DARNTON, Robert. The high enlightenment and the low-life of literature in prerevolutionary France. Past and Present, 1971, no. 51, p. 81–115.

DARNTON, Robert. A Literary Tour de France. The World of Books on the Eve of the French Revolution. (Oxford: OUP, 2108). ISBN: 9780195144512.

DARNTON, Robert. Pirating and Publishing. The Book Trade in the Age of Enlightenment. Oxford: OUP, 2021. ISBN: 9780195144529.

DARNTON, Robert. Readers respond to Rousseau: the fabrication of Romantic sensibility. In DARNTON, Robert, The Great Cat Massacre and other episodes in French Cultural History. New York: Basic Books, 1984), p. 217–56. ISBN 0-394-72927-7.

DIJN, Annelien de. The Politics of Enlightenment from Peter Gay to Jonathan Israel. Historical Journal, 2012, t. 55, p. 785–805. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X12000301.

EDELSTEIN, Dan. The Enlightenment. A Genealogy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0226184494.

EVRARD, Sébastien. L’Estampillage des contrefaçons en 1777 et l’édition juridique, d’après les archives des chambres syndicales d’Orléans, de Dijon et de Nancy. Histoire et civilization du livre, 2017, t. 13.

GASKELL, Philip. New Introduction to bibliography. Oxford: O.U.P., 1972. ISBN: 9781884718137.

GLADSTONE, Clovis and COONEY, Charles. Opening new paths for Scholarship: algorithms to track text reuse in Eighteenth-Century Collections Online. In BURROWS, Simon; ROE, Glenn (eds.). Digitizing Enlightenment. Digital Humanities and the Transformation of Eighteenth-Century Studies. Oxford University Studies in Enlightenment. Liverpool: Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment, 2020, p. 353–371. ISBN: 978178962195.

ISRAEL, Jonathan. Democratic Enlightenment: Philosophy, Revolution, and Human Rights 1750–1790. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN: 9780199668090.

ISRAEL, Jonathan. A Revolution of the Mind. Radical Enlightenment and the Intellectual Origins of Modern Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010. ISBN: 9780691152608.

JAGERSMA, Rindert. ‘Dutch Printed Private Library Sales Catalogues, 1599–1800: A Bibliometric Overview’. In WEDUWEN, Arthur der; PETTEGREE, Andrew; KEMP, Graeme (eds.). Book Trade Catalogues in Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, 2021, p. 87–117. ISBN: 9789004422247.

KATES, Gary. The Books that made the European Enlightenment: A History in 12 Case Studies. London and New York: Bloomsbury, forthcoming.

KORDA, Michael. Making the List. A Cultural History of the American Bestseller, 1900–1999: as Seen Through the Annual Bestseller Lists of Publishers Weekly. New York: Barnes and Noble, 2001. ISBN: 978-0760725597.

LYONS, Martyn. In Search of the Best-sellers of Nineteenth-Century France, 1815–1850. In LYONS, Martyn. Reading Culture and Writing Practices in Nineteenth-Century France. Toronto, Buffalo & London: University of Toronto Press, 2008, p. 15–42. ISBN: 9780802093578.

MARTIN, Angus; FRAUTSCHI, Richard. Towards a New Bibliography of Eighteenth-Century French Fiction. In BURROWS, Simon; ROE, Glenn (eds.). Digitizing Enlightenment: Digital Humanities and the Transformation of Eighteenth-Century Studies. Liverpool: Oxford University Studies in the Enlightenment, 2020, p.151–166. ISBN: 9781789621945.

MARTIN, Philippe. Une religion des livres, 1640–1850. Paris: CERF, 2003. ISBN: 2204071633.

MCKITTERICK, David. The Invention of Rare Books: Private Interest and Public Memory, 1600–1840. Cambridge: C.U.P. 2018. ISBN: 978-1108428323.

MILLER, Laura J. The Bestseller List as Marketing Tool and Historical Fiction. Book History, 2000, t. 3, p. 286–304.

MONTOYA, Alicia. Enlightenment? What Enlightenment? Reflections on Half a Million Books (British, French, and Dutch Private Libraries, 1665–1830). Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2021, t. 54 (4), p. 909–934.

MONTOYA, Alicia. Mornet reloaded: counting enlightenment bestsellers. In BOUTCHER, Warren; GRAHELI, Shanti (eds.). Bestsellers in the pre-Industrial Age. Forthcoming, Leiden: Brill, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/ecs.2021.0097.

MORNET, Daniel. Les Enseignements des bibliothèques privées, 1750–1780. Revue d’histoire littéraire de France, 1910, t. 17, p. 449–496.

PETTEGREE, Andrew (ed.). Lost Books: Reconstructing the Print World of Pre-Industrial Europe. Leiden: Brill, 2016. ISBN: 978-900431181-7.

ROCHE, Daniel. The People of Paris. Leamington Spa: Berg, 1987. ISBN: 0-907582-46-X.

RUELENS, Charles Lewis (ed.). The Imitation of Christ: being the autograph manuscript of Thomas à Kempis, De imitatione Christi, reproduced in facsimile from the original preserved in the Royal Library at Brussels. London: Elliott Stock, 1879.

SCHLUP, Michel. La Société typographique de Neuchatel (1769–1789): points de repère. in SCHLUP, Michel (ed.). L’Edition neuchâteloise au siècle des Lumières: la Société typographique de Neuchâtel (1769–1789). Neuchâtel: B.P.U.N., 2002, p. 61–105. ISBN: 978-2882250179.

SEAWARD, Louise. Censorship through co-operation: the Société typographique de Neuchâtel (STN) and the French Government, 1769–1789. French History, 2014, t. 28 (1), p. 23–42.

SEAWARD, Louise. The Société Typographique de Neuchâtel (STN) and the Politics of the Book Trade in Late Eighteenth-Century Europe, 1769–1789. European History Quarterly, 2014, t. 44 (3), p. 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265691414535025.

SORENSON, Alan T. Bestseller Lists and Product Variety: The Case of Book Sales. Stanford Graduate Business School Research Paper, No. 1878, June 2004. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.647608.

VERNUS, Michel. A Provincial Perspective. In DARNTON, Robert; ROCHE, Daniel (eds.). Revolution in Print: The Press in France, 1775–1800. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1989, p. 124–38. ISBN: 9780520064317.

1 Bibliothèque nationale de France [BnF], MS Fr. 21,934 fo. 41; MS Fr. 21,935 fo. 32, item 400.

2 MS Fr. 22,037, fo. 46v, item 7. Quite what was intended by the Boursault reference is uncertain because the wording is ambiguous: presumably ‘une’ was intended to indicate either the entire privilège or a quarter share, as in the previous item. Edmé Boursault was a seventeenth-century dramatist.

3 An autographed and dated 193 fo. manuscript of the Imitatio Christi from 1441 (the very moment Johannes Gutenberg was first experimenting with movable type printing) survives in the Belgian Royal Library (KBR). The online library catalogue lists it under MS 5455-61 ‘Thomas a Kempis. Opera’ but does not give a precise reference. For a facsimile edition see RUELENS, Charles Lewis (ed.). The Imitation of Christ: being the autograph manuscript of Thomas à Kempis, De imitatione Christi, reproduced in facsimile from the original preserved in the Royal Library at Brussels. London: Elliott Stock, 1879.

4 Alicia Montoya concludes a forthcoming paper by referring to ‘the hitherto heuristically useful but perhaps ultimately obsolete notion of the “Enlightenment Bestseller”.’ MONTOYA, Alicia. Mornet reloaded: counting enlightenment bestsellers. In BOUTCHER, Warren; GRAHELI, Shanti (eds.). Bestsellers in the pre-Industrial Age. Forthcoming, Leiden: Brill, 2022. I thank the author for permission to refer to the content of this article.

5 MORNET, Daniel. Les Enseignements des bibliothèques privées, 1750–1780. Revue d’histoire littéraire de France, 1910, vol. 17, p. 449–496.

6 BnF, MS Fr. 21,834 fos 118–193. See also BURROWS, Simon. Charmet and the Book Police: Clandestinity, Illegality and Popular Reading in Late Ancien Régime France. French History and Civilization, 2015, vol. 7, p. 45–46.

7 These estampillage records are dispersed across MS Fr. 21,831-21,834. A ninth set of records, for the local Chambre syndicale district, have recently surfaced in Dijon, Archives Départementales de la Côte d’Or, C 380-381. The Dijon estampillage is discussed in EVRARD, Sébastien. L’Estampillage des contrefaçons en 1777 et l’édition juridique, d’après les archives des chambres syndicales d’Orléans, de Dijon et de Nancy. Histoire et civilization du livre, 2017, vol. 13.

8 The estampillage records are spread across BNF, MS Fr. 21,831-21,834. Figures remain provisional. Figures for stamped copies of the Imitation de Jésus Christ have been consolidated and updated since previous publications.

9 MARTIN, Philippe. Une Religion des livres, 1640–1850. Paris: CERF, 2003.

10 MILLER, Laura J. The Bestseller List as Marketing Tool and Historical Fiction. Book History, 2000, vol. 3, p. 286–304. At p. 289. In Britain the first bestseller lists appeared in The Bookman in the early 1890s and in the United States a similarly-titled publication published the first American list in 1895. The New York Times only began publishing its weekly bestseller list in October 1931.