Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2022, vol. 78, pp. 225–245 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2022.78.113

Talking Books: A New Approach to Biblioforensics

Sydney J. Shep

Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington

Wai-te-ata Press, PO Box 600, Wellington 6140, New Zealand

E-mail: Sydney.Shep@vuw.ac.nz

Summary: Bibliographers are trained in the forensics of the material book and consider every material component as a piece of evidence assembled for a ‘Crime Scene Investigation.’ But what if the books themselves could talk? How can we tell research-informed, imaginatively-inspired stories that reanimate objects when confronted with the wholesale destruction of buildings, material goods and business records as a result of war? Drawing on research on the nineteenth-century book trades in Southampton, this paper enacts a new model of situated knowledges to question our current biblioforensic practices. It proposes that archival loss enables book historians to reconsider our relationship with our objects of study and opens the door to new forms of archival encounter as well as new forms of scholarly expression.

Keywords: biblioforensics, locative storytelling, digital humanities

Kalbančios knygos: naujas požiūris į bibliokriminalistiką

Santrauka. Bibliografai yra parengti popierinių knygų kriminalistikai ir kiekvieną materialią sudedamąją dalį laiko įrodymu, surinktu „nusikaltimo vietos tyrimui“. Tačiau kas nutiktų, jei pačios knygos prabiltų? Kaip galėtume papasakoti moksliniais tyrimais pagrįstas, vaizduotės įkvėptas istorijas, kurios atgaivina tyrimo objektus, kai susiduriama su didelio masto karo sukeltu pastatų, materialiųjų vertybių ir verslo dokumentų sunaikinimu? Remiantis XIX amžiaus prekybos knygomis Sautamptone tyrimais, šiame darbe pateikiamas naujas tam tikromis sąlygomis egzistuojančių žinių modelis, leidžiantis suabejoti mūsų dabartine bibliokriminalistikos praktika. Jame teigiama, kad archyvų praradimas leidžia knygų istorijos specialistams persvarstyti mūsų santykį su mūsų tyrimo objektais ir atveria duris naujoms netikėto susitikimo su archyvine medžiaga bei mokslinės raiškos formoms.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: bibliokriminalistika, lokatyvinis (vietininko) pasakojimas, skaitmeniniai humanitariniai mokslai.

Received: 2021 11 07. Accepted: 2022 03 01

Copyright © 2022 Sydney J. Shep. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

-----------------

We cannot bring back to life those whom we find cast ashore in the archives. But this is not a reason to make them suffer a second death. There is only a narrow space in which to develop a story that will neither cancel out nor dissolve these lives, but leave them available so that another day, and elsewhere, another narrative can be built from their enigmatic presence.

Arlette Farge1

On the evenings of 30 November and 1 December 1940, Southampton sustained 712 aerial bombardments by German forces that destroyed much of the city’s commercial heartland and industrial infrastructure. A once vibrant Victorian town was reduced overnight to craters, twisted metal, and rubble. The book trades likewise suffered along with their buildings, material goods, and business records. In this landscape of archival loss, how do we stitch together a narrative of a world now physically absent, if not virtually forgotten? Can digital interventions facilitate a new kind of storywork? The secondhand trade is rich with stories of lost treasures, silent witnesses, and perambulating books. But, as Walter Benjamin provocatively asked in 1916, ‘What if things could speak? What would they tell us? Or are they speaking already and we just don’t hear them?’2 Drawing from research on the nineteenth-century book trades in Southampton,3 this paper questions our current biblioforensic practices. It proposes that archival loss enables book historians to reconsider our relationship with our objects of study and opens the door to new forms of archival encounter as well as new forms of scholarly expression.

Set in Barcelona in 1945 as the city emerges from its war-torn past, Carlos Ruis Zafón’s novel The Shadow of the Wind features a secondhand bookseller, his son, and a book. Like Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose and its Piranesian shadow, a library also figures prominently: The Cemetery of Forgotten Books:

A labyrinth of passageways and crammed bookshelves rose from base to pinnacle like a beehive, woven with tunnels, steps, platforms and bridges that presaged an immense library of seemingly impossible geometry [...] This is a place of mystery, Daniel, a sanctuary. Every book, every volume has a soul. The soul of the person who wrote it and of those who read it and lived and dreamed with it. Every time a book changes hands, every time someone runs his eyes down its pages, its spirit grows and strengthens.4

Zafón evokes a long-established trope of the animistic book. In Thoughts on Various Subjects (1711), Jonathan Swift claimed that his books ‘seemeth to be alive and talking to me.’5 In 1678, Anne Bradstreet addressed ‘Thou ill-formed offspring of my feeble brain’6 when she penned her poem ‘The Author to her Book.’ Most famously in Areopagitica (1644), that resonant homage to the liberty of unlicensed printing, John Milton wrote

for Books are not absolutely dead things, but doe contain a potencie of life in them to be as active as that soule whose progency they are [...] as good almost kill a Man as kill a good Book; who kills a Man kills a reasonable creature, Gods image; but hee who destroyes a good Booke, kills reason it selfe, kills the image of God, as it were in the eye. Many a man lives a burden to the earth; but a good Booke is the pretious life-blood of a master spirit, imbalm’d and treasur’d up in purpose to a life beyond life.7

The idea of a book being a living, breathing thing punctuates western literature at least since the proliferation of medieval verse riddles.8 In the field of book history, the trope is likewise alive and well. In his 1983 address to the Bibliographical Society in which he proposed a sociology of texts, D. F. McKenzie suggested that the book is ‘a friskier and therefore more elusive animal than the words “physical object” will allow’.9 Riffing on Milton’s iconic phrase, Nicolas Barker edited a collection of eight essays entitled A Potencie of Life: Books in Society based on the 1986-7 William Andrew Clark Library Lectures. Notably, the volume introduced Barker and Thomas Adams’ ‘New Model for the Study of the Book’ which revised Robert Darnton’s 1982 communications circuit, shifting the focus from historical actors to functions and foregrounding the importance of historical processes, specifically transmission.10 And yet, whether as bibliographers, historians, or literary critics, book historians continue to describe books as objects and insist on telling their academic stories in their own dispassionate, third-person voice. By so doing, do they deny a book’s subjectivity, its fundamental right to life, its agency, its aliveness?

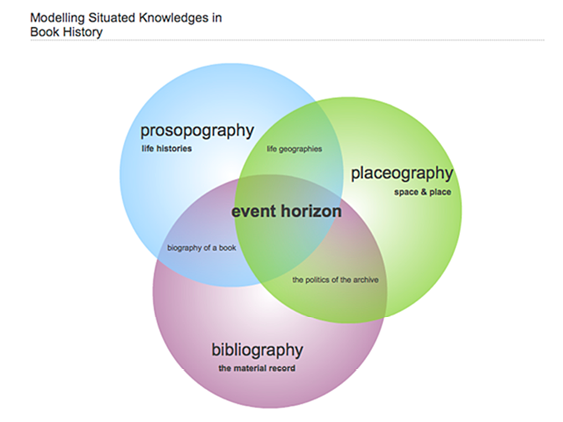

At SHARP’s 2012 conference in Dublin, I started exploring models of postnational and translocal book history. By 2015, I published a new ‘Situated Knowledges for Book History’ model which proposed a networked, relational world to counter the ubiquitous communications circuit.11 In the wake of popular commodity biographies and compilations of museum object stories, I wanted to interrogate similar kinds of object-oriented biblio-narratives that we as bibliographers and book historians tell. In the model’s event horizon where people, places, and things meet up, I imagined a new kind of materiality that would enhance and enliven our conversations (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The premise of the model is that knowledge is the product of multi-dimensional transactions between people (prosopography), places (placeography), and material records or things (bibliography) in the nexus of event horizons. This model is a research framework, a research ontology, and a research methodology. People acquire information either directly or indirectly in particular places, at particular times, and through particular channels. The exchange of information can be modelled as a time-stamped event shaped by the specific site of knowledge acquisition and mediated by the specific communication form, whether a letter, a lecture, a conversation, a published pamphlet, or a book. The circulation of such ‘situated knowledge’ is both mobile and mutable, polychronic and multi-temporal; it changes over time and is moulded by socially, culturally, economically, and politically-embedded and embodied practices. Like a rhizomorphic network, it is also a fluid field of production characterised by cycles of connectivity, multiplicity, and rupture. Such ‘knowledge in transit’12 requires an understanding of both location and locution; that is, space and language re-conceptualised as the ‘geosemiotics’13 of knowledge transfer.

Having written an object biography on William Colenso’s composing stick and investigated it-narratives in nineteenth-century typographic journals, I was also inspired by Leah Price’s call to think through what Roger Chartier called an ‘internalist’ account of reading. In The Order of Books, Chartier urges book historians to look, not at the reading habits of a group defined by ‘a priori social oppositions,’ but rather at ‘the social areas in which each corpus of texts and each genre of printed matter circulates.’14 Price elaborates on this brief In How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain: ‘instead of starting from a person and asking what books he owned,’ she proposes a method that ‘starts from a book and asks into whose possession it came. In this model, the book would exemplify Arjun Appadurai’s argument that while “from a theoretical point of view human actors encode things with significance, from a methodological point of view it is the things-in-motion that illuminate their human and social context.”’15

However, as I applied the situated knowledges model in my everyday practice, I became increasingly uncomfortable with the notion of a ‘biography’ of a book that privileged anthropogenic authority and denied agency to the more-than-human. I turned to the work of Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour, and Jane Bennett, amongst others, where the debates about the western nature|culture binary, agency, and thing-formation were being interrogated. Donna Haraway, for instance, claims that ‘situated knowledges require that the object of knowledge be pictured as an actor and agent, not as a screen or ground or resource, never finally as slave to the master that closes off the dialectic.’16 In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari propose that ‘a book has neither object nor subject; it is made of variously formed matters, and very different dates and speeds. To attribute the book to a subject is to overlook this working of matters, and the exteriority of their relations.’17 Like Latour’s ‘actant,’ a book symbiotically both translates actions and shapes them. Reading becomes, then, a co-mingling of matter/s that embraces both peritext and epitext and, as in Appadurai’s formulation, is subject to ‘individual manipulation.’ The intersection between people, places, and things that constitutes the event horizon in the situated knowledges model resonates with Philippe Lejeune’s notion that autobiography is a mode of reading negotiated between writer and reader. His ‘pacte autobiographique’ liberates the subject/object dichotomy, and energises the idea of identity co-creation, thus underscoring Charlie Gleek’s contention that ‘a bibliographic document (book) articulates its own autobiography, and that a reader only apprehends this autobiography when they encounter or read the object in a specific textual condition.’18 Inserting the work of Clifford Geertz and Mika Bal into the world of commodity exchange, Simon Frost notes that ‘the exchanged object, its wording and other material signs, does not have meaning in and of itself but that meaning, along with value in toto, is created in the event of the sign-objects framed […] an idea that can be clarified by thinking of the “book” itself as a social event.’19

Frost’s solution to the book as social event is to stage a series of five encounters between readers and books in Henry March Gilbert’s ‘Ye Olde Booke Shoppe’ at 26, Above Bar Street, Southampton, around 1900. These ‘imaginative acts’ are less pieces of creative non-fiction than examples of historical fiction, constrained by verifiable historical facts whose measure is plausibility, yet self-consciously fashioned by a culturally, temporally, and spatially embodied twenty-first-century author. ‘The figures populating the following narratives have existed. Traces of them are extant in the historical record, but their voices are lost: a dilemma faced by historical reading studies.’20 The reading profile of each character is deftly shaped, punctuated by mentions of contemporary newspapers, periodicals, and books: often named, sometimes priced, and incidentally, described. As we voyeuristically eavesdrop on these engaging inner soliloquies, the focus remains firmly on how individual readers may have experienced the process of exchange in commodity culture. In the process, paradoxically, the individual book’s thingness, its vibrant materiality is erased. This is particularly evident in the enumeration of titles that may have been in Gilbert’s bookshop as well as the assumption that the preliminary bibliography of Gilbert’s publications in Frost’s appendix functions as a placeholder if not surrogate for the absence of any extant bookseller’s catalogues or provenance research documenting known copies with Gilbert’s distinctive yellow bookseller’s ticket. Thus, each reader’s life is a concatenation of possibilities based on generic distinctions between class, gender, and political leanings. Is there another way of giving voice to these artefacts of attention, these workings of matter?

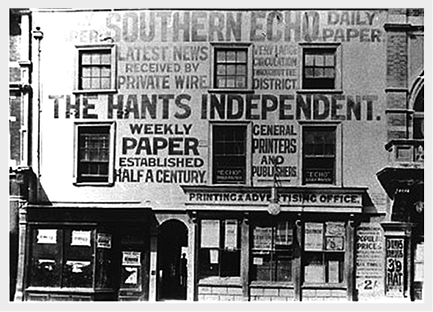

Exhibit A: Southern Daily Echo, 1910. Southampton City Libraries.

He stands, shimmering in the half light, almost not there. A silhouette framed by text. An apron, the emblem of his trade. A boy. A devil, perhaps. A pixel.

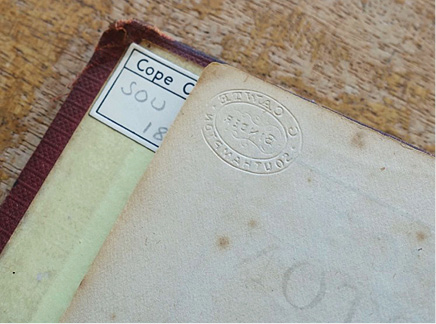

Exhibit B: Cawte blind embossed stamp. Southampton Directory 1878, Cope Collection Southampton University Library.

My skin is smooth, crisp to the touch and ear, smelling of old age, tasting of many hands. My flyleaf is crushed by an oval stamp, raised on the recto, indented on the verso. My senses trace G. Cawte, binder, Southampton.

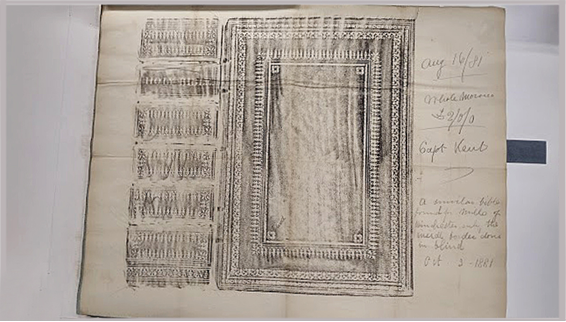

Exhibit C Captain Kent’s Bible, August 16, 1881. Cox Papers, Southampton City Archives, (D/Cox.G 1/6/1)

Large gestural swashes of graphite expose the blind embossed surface of my fine morocco binding. I belonged to Cap’t Kent who paid an astonishing £2/2/0 for me in 1881. Today, I exist only as a tracing.

These three exhibits exemplify what I call ‘ghosts in the archive.’ They may be an apparition, a spectre; a shadowy outline or semblance, an unsubstantial image (of something), hence, a slight trace or vestige; bibliographically, they may be a non-existent book or edition or issue erroneously included in some work of reference which by repetition has achieved a misleading semblance of reality.21 They are not documented in the catalogue record or metadata. They rarely survive the transition into digitised spaces and may only appear as a shadowy digital presence. For all intents and purposes they might not even exist. And yet, they have lives to be acknowledged and stories to be told. But who can tell their stories? Or more particularly, who has the right to tell their stories?

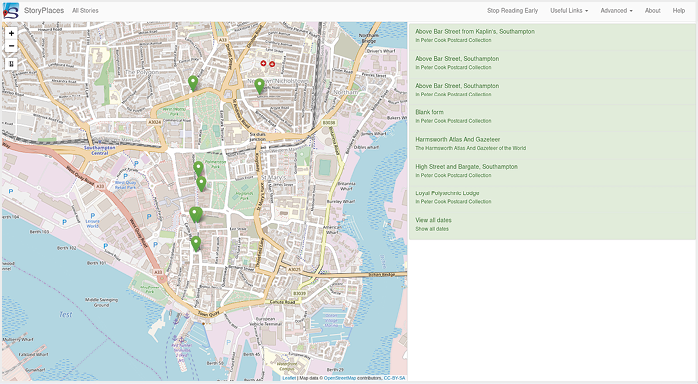

Locative, site-specific, or ambient storytelling22 has emerged as a way of generating interactive narratives that position the reader as storymaker prompted by moving through physical or virtual spaces. These experiences can be multimodal, often featuring a combination of visual, audio, and spatial cues that shape the reader’s actions and decisions. They are also influenced by game theory and its focus on play, open-ended scripting, and collaboration. From 2015, the Leverhulme Trust funded the University of Southampton to explore the poetics of location-based storytelling. The outcome was StoryPlaces,23 a platform for telling and authoring locative stories on the web using a mobile app.24 For my 2018-19 British Academy-funded Southampton Book Trades Project, one of StoryPlaces’ main developers and PhD candidate Callum Spawforth, created a bespoke instance of the app that interfaced with the Southampton University’s Virtual Reading Room (VRR) where the project’s digitised images, metadata, and captions were stored.25 Geolocated digital assets in the VRR were pinned to a Google map in StoryPlaces26 so that users could undertake a heritage walking tour of Southampton’s commercial spine where most bookworkers and their places of business were located.

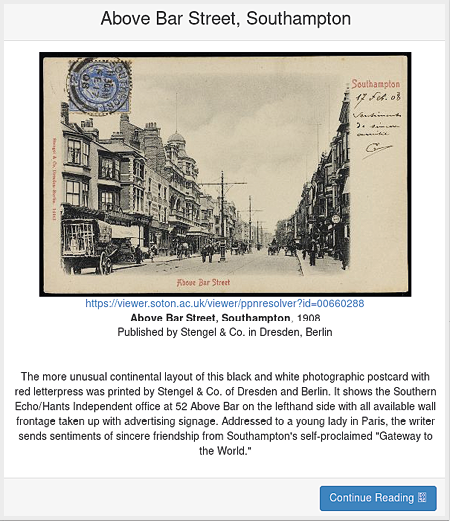

Once clicked, each node (signalled by the green flag  on the map and listed alphabetically on the right) displays a thumbnail of the VRR image with a link to the artefact, as well as salient details about the artefact such as author, publisher, bookworker, and a caption.

on the map and listed alphabetically on the right) displays a thumbnail of the VRR image with a link to the artefact, as well as salient details about the artefact such as author, publisher, bookworker, and a caption.

Three stories enable different modes of user interaction: simultaneous access to all artefacts; access while in situ at the specific physical location triggered by a GPS alert on your mobile; and temporal slices by decade. As Spawforth explains,

the first story produced provides access to all of the artefacts simultaneously, with no requirements that the reader visit the location. This allows a reader to freely explore the artefacts, while still being able to view the location of the associated bookworker within Southampton. This also provides a useful view for authors who wish to view the locations they have to work with while hand-crafting a story. The second story is nearly identical to the first, except it requires readers to be present at the location in order to read the content. By mandating in-situ reading, we can give a sense of place to each of the artefacts. This is particularly true for the artefacts that present images of Southampton. The third story provides the reader with a list of time periods to choose from: by default, these have been chosen as decades. When selected, all of the artefacts published in that decade are shown. While this story demonstrates a means of filtering content, locations are not shown on the map for each decade, limiting its ability to be read on location.27

Although we did not have time to rigorously test the prototype in the field or gather statistical evidence of its use, we recognised that future refinements should include using georectified historical maps as the base map, a feature not possible in the current software configuration; the addition of creative non-fiction narratives, specifically in the genre of the ‘it-narrative’ which focus on the book or archive object telling its own story generated by the researcher and/or through public interactions; and a customised StoryPlaces instance to enhance the artefact-driven experience, making it more accessible to the public and delivering greater impact.

One example of an artefact narrative brings us back to Gilbert’s bookshop. William Williams’ A Dictionary of the New Zealand language, and a concise grammar; to which are added a selection of colloquial sentences travelled from its birthplace in Paihia, New Zealand in 1844 to Gilbert’s bookshop in Southampton, and back to the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington (New Zealand). Drawing on research in two hemispheres that documented over two centuries of material peregrinations, I recently offered a biography of this book followed by a thought experiment, an autobiography.28 Could the latter have existed without the former? Can the evidence upon which a new approach to biblioforensics is based be conveyed solely through an it-narrative, though a talking book?

Tīhei mauri ora!

My skin has been cut, dampened, folded, and torn. How many times do I have to go through this blasted Columbian? I’m kissed and bitten, blackened and embossed, tattooed, hung out to dry. My head and tail have been trimmed, my spine folds pierced with a sharp needle, waxed linen thread sliding through my raw portholes. Then put into another press and squeezed until the breathe in me is almost gone, slapped between two boards like a sandwich, and cased-in to protect me from any horny-handed reader. More pressing and gluing, my name in all caps printed on the cloth-covered spine, with price in italics, ready to be sold and shelved, but where? Under ‘Dictionaries and Other Reference Works’? Rubbing shoulders with other books in the language of my whānau? Beside Kendall (that raho kau /adulterer) and Lee, the Cambridge professor who regularised te reo after talking with two Ngā Puhi chiefs, Hone Hika and Waikato? Adjacent to Maunsell’s 1842 noble effort? If I were William Shakespeare, I’d certainly have something to say if Kit Marlowe were slid in beside me.

And what would the Reverend William Colenso think? He had already set and printed 12 pages of these kupu in 1840 and now three years later his colleague John Telford is starting all over again. I hope Telford has a better arrangement of letters in the typecase. Colenso set so much in te reo that he designed a special lay of the case, but when it came to setting English, ah me, he had to go scrabbling through all the twisted packets on the shop floor to find what he was looking for. Where’s those blasted ‘h’s, I can hear Telford cry. His predecessor filed off the lower bowl of his ‘b’s to make more sorts since it was a six month return sea voyage at least before any more type would arrive. And what about those high and low commas? I know there was a perennial debate about how to typographically interpret the aspirated ‘wh’ and the ‘ng’, but really, can print actually do justice to sound? Williams’ solution was to indicate the ‘wh’ sound with an inverted comma before the ‘w’. Later in my life I overheard his grandson, Herbert William Williams, talk about a different approach: creating a kerned pair with a ‘v’ and an ‘h’ as well as filing the bowl off the ‘g’ and making it look like an ‘n’ with a long tail. But alas, that suggestion didn’t get very far; expense intervened and no one quite knew how to move te reo forward even as the language was dying out along with its orators.

Colenso and Williams didn’t always see eye-to-eye, particularly when it came to te reo, but the Bishop wielded greater influence and my 5,380 words and 138 colloquial expressions became the official textbook. For most of his life poor Colenso worked away on his Māori-English Lexicon, wanting to show his superior just how this dictionary-making enterprise should be done. But when he died in 1899, all he had to show as evidence of his labours were several manuscript lists and the letter “A” printed by the Government Printing Office. At the time, it was remarked that “if he could have completed it on the scale on which it was commenced, [it] would have been a monumental record of the language, but it would have been of little use except in the realm of philology.”

I don’t mind, really. I have 550 siblings and I’m sure they have had, like me, the time of their lives. Telford reported that ‘there seems to be a common cry for it at present, at all hands.’ He sold copies at 7s6d from the Mission Press in Paihia and through a keen Auckland bibliophile Dr William Davies. As its compiler had predicted, the need for two languages in Aotearoa was increasingly important in order to avoid misunderstandings and defuse tensions. In fact, even though the list of colloquial expressions included the usual categories of Christian preparedness, Bible reading, work ethics, bad habits, and illness, Williams began by positioning me between two cultures – almost as if he were speaking to me and through me. ‘Where do you come from? No hea koe; When did you come? Nona hea koe i haere mai ai; What are you come for? He aha koe i haere mai ai?’

Five years later, Edward Marsh Williams, son of Henry Williams and nephew of William Williams, dashed off his abbreviated signature with a flourish, “Faithfully May 1849” on my half title page and sent me on my way. I even heard some books were grangerised, disbound, interleaved, and rebound so local scholars like Sir George Grey, Alfred Domett and Thomas Hocken could study me, annotate me, correct me, add to me, rendering my language living and far from dead. It didn’t take long before Williams’ son, William Leonard Williams, continued the family’s lexicographical enterprise. My text began to go viral, with editions in 1852 and 1871 printed in London and Edinburgh. Just like the Māori Bible, poor Telford didn’t have a chance to repeat his leaden performance. As Colenso predicted in 1842: it would be quicker, cheaper and better to print it in England. It certainly made it easier for H.K. Taiaroa to buy a copy which he inscribed with the date Tihema 9 1881 and which eventually travelled to Rhodes House in Oxford – that bastion of colonial power. Sadly, unsupervised printing offshore had its downside: this 1871 third edition had ‘a deplorable number of typographic errors that disfigured the page’ and made a mockery of Williams’ scholarship. By the 1892 edition, printing was repatriated to New Zealand where Robert Coupland Harding, friend to both Colenso and the Williams family, completed the typesetting and printing, his distinctive pressmark appearing on the title-page.

But where did I end up? Believe it or not, I travelled all the way to England, packed in a tin-lined crate along with some of my siblings and other theological rarities. It was dark in there and between the smell of stale salt water, the incessant scratching of rats and silverfish looking for their next meal, it was all I could do to hold my insides tightly together and wait for the incessant rocking and rolling to end. We finally saw the light of day at the Church Missionary Society Head Office in Salisbury Square just off Fleet Street in London and across from St. Bride Church, that sanctuary dedicated to printers and journalists. And what a city it was: from quiet of Paihia’s shoreline to the bustling maritime epicentre of empire. CMS Secretary Dandeson Coates breathed his prayerful utterances over my head and fingered me a little too fondly, so I was rather glad to escape to another set of, as yet unknown, hands and another adventure. This time, I travelled southwards by the new railway, to the port of Southampton. As soon as I arrived, I immediately felt at home. Henry March Gilbert was a local bookseller who ran Ye Olde Boke Shoppe on the main street. Having apprenticed with Henry Sotheran, he knew his trade. Why, not only did I now have 50,000 friends, but at any one moment, I could be taken off the shelf, opened up, admired and read. In fact, I even wore a badge of honour, a yellow and black engraved bookseller’s sticker that was affixed to my inside front cover, partially covering my price tag of 7/6-. H.M Gilbert & Son had formerly adopted me. But sadly, not for life.

One day, Henry’s son Owen pulled me off the shelf, examined me inside and out like a medical doctor, and parcelled me up firmly in brown paper and string. I overheard heard something about an auction and London before he dropped me at the General Post Office. Another rail journey, another long boat trip and, guess what, I was back in New Zealand! But this time it wasn’t sleepy Paihia, it was the bustling capital city, Wellington. The local auction house, J.H. Bethune and Sons had assembled a job lot of New Zealand rarities from a number of overseas booksellers including Bernard Quaritch and Frank Redway. I was next on the block with my lot number 193 printed in Ultra Bodoni and pasted on my back cover. The atmosphere was tense, bidding was fierce, but my new owner was a bibliophile with the grandest of names: Alexander Horsburgh Turnbull. They said he was a merchant, but I had my doubts. He always seemed to be sailing on his classic yacht the Rona, entertaining his friends over port and cigars, admiring his cabinet of Māori and Pacific curiosities, reading in his enormous, three-room library, ordering books from a stack of overseas catalogues, processing the contents of tin-lined cases which arrived on every other mail, or drifting in a laudanum-induced fug. After paying 20/- for me (a grand sum compared to my original price of 7/6-) he claimed me as his own, gently gluing his newest albeit least popular woodcut armorial bookplate to my inside front cover, annotating my flyleaf with references to Hocken’s Bibliography (p. 118) and Grey’s Catalogue (n.6), and carefully thumbing through my pages with great interest and care. He shelved me beside my cousins, the later editions of Williams’ Dictionary, in the New Zealand Room on the second floor of his new red brick abode, a quirky mix of Scottish Baronial, Queen Anne and medieval architecture. He also added me to his own catalogue, pasting a handwritten slip into his huge folio volume under the year 1844. It was quite clear from his long quest and quiet boasting that I was his ‘rarissima.’ Williams 4 concurred, and he should know. He was printed by Colenso’s dear friend, Robert Coupland Harding, who himself was gifted Colenso’s own ‘rarissima’ copy of the New Testament in Māori when he relocated from Napier to Wellington in 1890.

Unfortunately, Mr Alex, the ’handsome dandy’ died in on 28 June 1918 and my fate was sealed. Turnbull gifted his entire collection to the nation, but what a scramble it was to make me presentable to the clamouring public. Three ‘lady assistants’ were deputised to catalogue the collection. I was never sure which pair of soft hands pulled me off the shelf, but on the 8.03.1920, one of the Misses Cowles, Davidson, or Gray entered me into a huge leather-bound Accession Register, transcribed the number ‘6691’ onto my flyleaf, added a typographic cipher (a blackletter “T”) to page 21, and pencilled 1920 discreetly on the verso of my titlepage. All dressed up and ready for the fanfare of opening day, 28 June 1920, I waited patiently for the first eager readers to explore my pages. Horace Fildes, a local collector, James Cowan the ethnographer, Professors Von Zedlitz, Beaglehole, and Rankine Brown from Victoria University College all plumbed the depths of Turnbull’s collection and, in particular, the rich seams of Māori history. Alas, no-one seemed to be interested in me and the dust gathered on my head.

During WWII, I was parcelled up with my shelf-mates and sent north to the provincial gown of Masterton for safe-keeping. When I returned, there was talk of a purpose-built library, given the shelves at Turnbull’s home were bursting with new acquisitions and readers needed more space. I wandered temporarily just around the corner to The Terrace in 1973, but once the National Library of New Zealand was completed in 1987, I shifted to its climate controlled basement. Boxed up and sent travelling once more during building renovations in 2009, today I live in the bowels of this library within a library. Most of the time, I stand at attention, enclosed in a grey solander box, in lockstep with my siblings and cousins. My skin is no longer pristine but itches insistently with the spidery blooms of mould and metal foxing. My spine has been knocked about and my head has been reinforced with Japanese tissue. Some years ago, I was the centre of attention when Penny Griffith and Phil Parkinson compiled the long-awaited annotated bibliography, Books in Maori bestowing upon me the name BIM 217. Today, I am rarely asked for and virtually never taken up to the Katherine Mansfield Reading Room. I haven’t even been digitised like my cousins. I sit alone and forgotten.

A second example moves us from Gilbert’s bookshop to the world of George Cawte and Henry Daubney Cox, bookbinders, whose tissue ledger documents this firm’s pivotal role in the Southampton shipping trade. These extant records attest to the range of mobile clientele, their literary interests, and their imperial aspirations. Captains and Commanders alike ordered bespoke bindings for their precious intellectual cargo. Between 1909-1910, eighteen steamships sent their libraries to 5 West Street for repair, rebinding, resewing, rebacking, and relettering. Often the monthly orders were simply described as a ‘box of books’; at other times we have the citation of precious titles: Germinal, Lorna Doone, Richard Feveral, Don Quixote, Plain Tales from the Hills, In Japan, Innocents Abroad and Round the World in 80 Days. Embarking from Southampton, locally-made leather bindings, blind and gilt tooling, paper, glue and linen thread wandered all over the world.

Here is an example:

CHE DICE is my name. I am in a double bind, my titled spine piece and spattered paper mounted over yet another spine, another cover, another set of decorated papers. My insides are filled with outsides. I am a part of all I have met. My cheap, unbleached, heavy binders’ pressing papers chafe against tissue rubbings of front covers and spines; patterns on stiff board created from fillets, roulettes, pallets inked in violet and pressed into graphite-gridded paper; lighter-weight maquettes bearing the tattoos of blind embossing; shiny black-and-white photo-reproductions of Grolier bindings from Paris clipped from The American Bookmaker and choice Rivières from The British Bookmaker. I am bound but a-part: a maker’s visual diary composed of fragments, jottings, imaginings made stenographically manifest, the in-dwelling precision of the bookbinder’s skilled hand, forearm, and shoulder jostling against the staccato tempo of rubbing flourishes, the lively energy of space distributed by glyphs of rabbit skin glue, oils from leather and crayon from rubbings ghosting, offsetting, transferring. I am filled with an orgy of books I haven’t read: cloth and leather spine pieces and covers; the shadows of titles, volumes, dates, publishers, places rising out of the shimmery strokes of graphite and crayon rubbings: Apostles and Martyrs, Partingtonian Patchwork, The Arabian Nights, Longfellow’s Poems, Roman de la Violette, Life of Dr. Arnold, A History of the Art of Printing, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Vingt Milles Lieues Sous la Mer, Trochten der Völker, Rheinfahrt, True Robinson Crusoe. The Aldine Poets – Pope vol. III, Don Quixote, Golden Treasury. My world of actual size is punctuated by horizons of temporality and time knots: the flyleaf signature 1880; the date of gift 2009; a torn half sheet of feint-ruled folio foolscap with Britannia watermark and countermark Snelgroves 1827 annotated with ‘It was a paper book. It is cheap paper and glazed; 10 hours – finish, 2 hours forward, July 21, 1898; ‘Books will be done before Dec. 25 if patterns are returned early – yes’; ‘My Dear Mary you look a little sleepy’ ‘Yes Mam.’ The material commerce of my workshop increasingly impinges on my rubbing, drawing, drafting. My thinking body shifts from a record of imagining and making to spaces of teaching and replication. The hand of an apprentice joins the hand of the master; textual instructions join visual mnemonics; errors are corrected; measurements are cited; materials and tools specified: Green Levant full, one line on edges of bands, one line five lines on headband, single medium line roll round side, red glove leather inlay, green Morris paper. CHE DICE is my name.29

To conclude, in June 2021, Times Higher Education correspondent Matthew Reisz reflected on an emergent scholarly genre that foregrounds personal experience, travelogue and the quest to find answers alongside archival research. He asked ‘At a time when the humanities are widely seen as being under threat, should more academics overcome their reluctance to put themselves at the heart of their writing?’ According to Professor Hazel Carby’s Imperial Intimacies, juggling memory, history and poetics provided the only way of doing justice to the range of issues she wanted to address: ‘If we are going to tell stories that involve us [...] conventional modes of writing [...] cannot possibly encompass the multiplicity of the tales that we want to tell.’ Although there is healthy scepticism amongst academic historians regarding these experimental approaches, Philip Carter, research and communications officer at the Royal Historical Society, hoped that ‘academic history is now much more open to experimentation in forms and approaches to writing about the past, and that the personal narrative (the historian within and as part of the history) is appreciated widely – not least because it engages openly with questions of the role of the historian in creating their “personal” version of the past.’30

Bibliographers are trained in the forensics of the material book and consider every material component as a piece of evidence assembled for a ‘Crime Scene Investigation.’ But what if the books themselves could talk? When Walter Benjamin asked ‘What if things could speak?’ he provocatively added ‘and who is going to translate them?’ As Gleek suggests, ‘we need not write a biography of a book because an autobiography already exists when we encounter the object. Instead, our scholarly goals become apprehending and articulating the stakes that such autobiographies play in mediating meaning.’31 If a new approach to biblioforensics inserts the book historian into the story and gives voice to artefacts, then locative storytelling becomes a compelling and innovative form of scholarly expression – assuming the institutionalised metrics for scholarly performance can embrace creative and generative approaches to new knowledge formation.

In her highly evocative work, The Allure of the Archives, French eighteenth-century historian Arlette Farge suggests that ‘the reality of the archive lies not only in the clues it contains, but also in the sequences of different representations of reality.’ Farge likens the historian’s approach to unpick the infinitude of these realities to that of a prowler

searching for what is buried away in the archives, looking for the trail of a person or event, while remaining attentive to that which has fled, which has gone missing, which is noticeable by its absence. Both presence and absence from the archive are signs we must interpret in order to understand how they fit into the larger landscape.32

Similarly, Walter Benjamin, who wrote about the ‘aura’ of objects in the age of photomechanical reproduction also crafted an essay ‘Excavation and Memory,’ in which he posits that it is not the object itself or the inventory of the archaeologist’s findings that is important, but rather, the act of marking the precise location where it is found.33

What are the stakes in apprehending and articulating the fusion of location and locution? By accepting the zoomorphic vitality of things, book historians can recalibrate the terms of material engagement, acknowledge their complicity in the construction of narratives, and forge new understandings of the interrelationship between people, places and things. As Farge muses,

Words are windows; they will let you catch a glimpse of one or several contexts. But words can also be tangled and contradictory. They can articulate inconsistences whose meaning is far from clear. Just when you think you have finally discovered the framework underlying the way events unfolded and individuals acted, opaqueness and contradiction begin to creep in. Incongruous spaces emerge with no apparent connection to the landscape that seemed to be taking shape only a few documents earlier. These discordant spaces and gaps harbour events as well, and the hesitant and unfamiliar words used to describe them create a new object. These words reveal existences or stories that are irreducible to any typology or attempt at synthesis, and do not neatly fit into any easily described historical context […] History is not a balanced narrative of results of opposing moves. It is a way of taking in hand and grasping the harshness of reality, which we can glimpse through the collision of conflicting logics.34

Reference list

BARKER, Nicolas ed. A Potencie of Life: Books in Society, London: The British Library, 1993. ISBN 9780712347204.

BENJAMIN, Walter. Excavation and Memory. In Selected Writings, Vol. 2, part 2 (1931–1934), ‘Ibizan Sequence’ 1932, ed. M.P. Bullock, M.W. Jennings, H. Eiland, and G. Smith. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0674945869.

BENJAMIN, Walter On language as such and on the language of man, in One-way street, and other writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott. Kingsley Shorter, London: New Left Books, 1979, pp. 107–123. ISBN 9780674052291.

BRADSTREET, Anne. ‘The Author to her Book’ (1678). Access through Internet: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43697/the-author-to-her-book.

CHARTIER, Roger. The Order of Books, trans Lydia G. Cochrane. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1994. ISBN 9780804722667.

DELEUZE, Gilles, GUATTARI, Felix. Introduction. Rhizome in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987, pp. 3-25. ISBN 9780816614028.

FARGE, Arlette. The Allure of the Archives, trans. Thomas Scott-Railton. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013. ISBN 9780300198935.

FARMAN, Jason ed. The Mobile Story: Narrative Practices with Locative Technologies. New York: Routledge, 2014. ISBN 9781136169557.

FROST, Simon R. Reading, Wanting, and Broken Economies: A Twenty-First-Century Study of Readers and Bookshops in Southampton around 1900, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2021. ISBN 9781438483511.

GLEEK, Charlie. Posting on discussion forum SHARP-L, 05.01.20. Access through Internet: https://www.sharpweb.org/main/sharp-l/

GREENSPAN, Brian. The New Place of Reading: Locative Media and the Future of Narrative. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 2011, 5:3. Access through Internet: http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/3/000103/000103.html ISSN 1938-4122.

HARAWAY, Donna. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 1988, 14:3, pp. 575-599. ISSN 2153-3873.

HARDY, Molly O’Hagan. Access through Internet: https://tenpound.com/bookmans-log/2019/10/the-disappearing-ghost-book

MCKENZIE, D. F. The Sociology of a Text: Orality, Literacy and Print in Early New Zealand. The Library, 1984, Sixth Series 4, p. 334. ISSN 0024-2160.

MILLARD, PACKER, HOWARD and HARGOOD. The Balance of Attention: The Challenges of Creating Locative Cultural Storytelling Experiences. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage, 2020, 13:4. https://doi.org/10.1145/3404195 ISSN 1556-4673.

MILTON, John. Areopagitica (1644). Access through Internet: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/areopagitica-by-john-milton-1644

PRICE, Leah. How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012. ISBN 9780691114170.

REISZ, Matthew. Is the future of history writing in the first person? Times Higher Education, 3 June 2021. Access through Internet: https://mailchi.mp/timeshighereducation.com/is-future-of-history-writing-in-the-first-person?e=393c1ce2e4 ISSN 0049-3929.

SANFORD, Peleg Burroughs. Scrapbook (Bookbinder’s visual diary), Chelsea MA, 1880-1910. American Antiquarian Society, Graphic Arts Bound Volumes F007 F.

SCOLLON, Ron & S.W. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World, London: Routledge, 2003. ISBN 9780415290494.

SECORD, James. Knowledge in Transit. Isis, 2004, 95:4, pp. 654-672. ISSN 1545-6994.

SHEP, Sydney J. Books in Global Perspectives. In The Cambridge Companion to the History of the Book, ed. Leslie Howsam. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 53–70. ISBN 9781107625099.

SHEP, Sydney J. Fluid Geographies and Global Mobilities: The Peregrinations of Williams’ Māori Dictionary 1844–2020. Bibliologia, 2020, is. 15, pp. 97-120. ISSN 1824-7733.

SOPER, Harriet. Reading the Exeter Book Riddles as Life-Writing. The Review of English Studies, 2017, 68:287, pp. 841–865. ISSN 1471-6968.

SPAWFORTH, Callum. Final British Academy Visiting Fellowship project report, April 2019, (unpublished).

SWIFT, Jonathan. Thoughts on Various Subjects (1711).

ZAFÓN, Carlos Ruiz. The Shadow of the Wind, trans. Lucia Graves. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004. ISBN 0-297-84897-6.

1 FARGE, Arlette, The Allure of the Archive, New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2013, pp. 121–2 (original edition Le Goût de l’Archive, Paris: Seuil, 1989).

2 BENJAMIN, Walter, On language as such and on the language of man, in One-way street, and other writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott. Kingsley Shorter, London: New Left Books, 1979, pp. 107–23.

3 Funded through a British Academy Visiting Fellowship, 2018-19; hosted by Professor E.M. Hammond, University of Southampton, UK.

4 ZAFÓN, Carlos Ruiz, The Shadow of the Wind, trans. Lucia Graves. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004, p. 3.

5 SWIFT, Jonathan, ‘Thoughts on Various Subjects’ (1711).

6 BRADSTREET, Anne, ‘The Author to her Book’ (1678), https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43697/the-author-to-her-book

7 MILTON, John, Areopagitica (1644), https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/areopagitica-by-john-milton-1644

8 SOPER, Harriet, Reading the Exeter Book Riddles as Life-Writing. The Review of English Studies 68:287 (2017), pp. 841–65.

9 MCKENZIE, D. F. The Sociology of a Text: Orality, Literacy and Print in Early New Zealand. The Library, Sixth Series 4 (1984), p. 334.

10 BARKER, Nicolas ed. A Potencie of Life: Books in Society, London: The British Library, 1993.

11 SHEP, Sydney J. Books in Global Perspectives. In The Cambridge Companion to the History of the Book, ed. Leslie Howsam. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 53–70.

12 SECORD, James. Knowledge in Transit. Isis 95:4 (2004), pp. 654–72.

13 SCOLLON, Ron & S.W. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World, London: Routledge, 2003.

14 CHARTIER, Roger. The Order of Books, trans Lydia G. Cochrane. Cambridge UK: Polity Press, 1994, p. 7.

15 PRICE, Leah. How to Do Things with Books in Victorian Britain, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012, p. 131.

16 HARAWAY, Donna. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies 14:3 (1988), pp. 575–99: 592.

17 DELEUZE, Gilles and Felix GUATTARI (1987). Introduction. Rhizome in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1987, pp. 3–25: 3.

18 GLEEK, Charlie posting on discussion forum SHARP-L, 05.01.20. https://www.sharpweb.org/main/sharp-l/

19 FROST, Simon R. Reading, Wanting, and Broken Economies: A Twenty-First-Century Study of Readers and Bookshops in Southampton around 1900, Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2021, p. 264.

20 Ibid., p.194.

21 ‘ghost’ in Oxford English Dictionary https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/78064?rskey=iMnDkC&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid and HARDY, Molly O’Hagan. https://tenpound.com/bookmans-log/2019/10/the-disappearing-ghost-book

22 GREENSPAN, Brian. The New Place of Reading: Locative Media and the Future of Narrative. Digital Humanities Quarterly 5:3 (2011). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/3/000103/000103.html. See also FARMAN, Jason ed. The Mobile Story: Narrative Practices with Locative Technologies. New York: Routledge, 2014.

24 http://storyplaces.soton.ac.uk/publications.php and more recently, MILLARD, PACKER, HOWARD and HARGOOD. The Balance of Attention: The Challenges of Creating Locative Cultural Storytelling Experiences. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 13:4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1145/3404195

26 story.sotonbooktradehistory.org. Sadly, this domain has expired and the link is now no longer live: a not uncommon fate of many digital projects.

27 SPAWFORTH, Callum. Final British Academy Visiting Fellowship project report, April 2019, unpublished.

28 SHEP, Sydney J. Fluid Geographies and Global Mobilities: The Peregrinations of Williams’ Māori Dictionary 1844–2020. Bibliologia 15 (2020), pp. 97–120.

29 SANFORD, Peleg Burroughs. Scrapbook (Bookbinder’s visual diary), Chelsea MA, 1880–1910. American Antiquarian Society, Graphic Arts Bound Volumes F007 F.

30 REISZ, Matthew. ‘Is the future of history writing in the first person?’ Times Higher Education, 3 June 2021. https://mailchi.mp/timeshighereducation.com/is-future-of-history-writing-in-the-first-person?e=393c1ce2e4

31 GLEEK, Charlie. posting on discussion forum SHARP-L, 05.01.20. https://www.sharpweb.org/main/sharp-l/

32 FARGE. Allure of the Archives, pp. 30, 71.

33 BENJAMIN, Walter. ‘Excavation and Memory,’ in Selected Writings, Vol. 2, part 2 (1931–1934), “Ibizan Sequence” 1932, ed. M.P. Bullock, M.W. Jennings, H. Eiland, and G. Smith. Cambridge MA: Belknap Press, 2005, p. 576.

34 FARGE. Allure of the Archive, p. 85-6.