Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2023, vol. 80, pp. 147–174 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2023.80.127

Production of Vernacular Catechisms in Early Modern Königsberg (1545–1575), Its Dynamics and Goals Defined by the Print Agents

Wojciech Kordyzon

University of Warsaw, Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28,

00-927 Warsaw, Poland

E-mail: wojciech.kordyzon@uw.edu.pl

-------------------------------------------

This research was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland (Grant No. 2020/37/N/HS2/00467). The author holds the scholarship START 2022 awarded by the Foundation for Polish Science (FNP).

-------------------------------------------

Summary. This paper discusses the development of the vernacular catechism as a printed genre. The process is exemplified by the editions published in Königsberg between 1545 and 1575 where the catechisms were printed in several vernacular languages (German, Lithuanian, Polish, Prussian) in printing shops run by Hans Weinreich, Aleksander Aujezdecki, and Hans Daubmann. The paper seeks to analyse the material in terms of linguistic coverage in the Duchy of Prussia and, via analysis of the peritextual elements, how the print agents presented their work to the recipients. The aspects of book design, such as the volume, format, and decorations, are included in the analysis to indicate the intended book prestige and usage.

Keywords: Königsberg, Duchy of Prussia, vernacular catechism, early modern book industry, Hans Daubmann, Hans Weinreich, Aleksander Aujezdecki, Protestantism, Lutheran Reformation

Katekizmų vietinėmis kalbomis rengimas Karaliaučiuje ankstyvuoju moderniuoju laikotarpiu (1545–1575): jo dinamika ir rengėjų tikslai

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje aptariama katekizmo vietinėmis kalbomis kaip spausdinto leidinio žanro tematika. Šis procesas nagrinėjamas pasitelkiant pavyzdžius leidinių, publikuotų nuo 1545 iki 1575 m. Karaliaučiuje, kur tuo metu Hanso Weinreicho, Aleksandro Aujezdeckio ir Hanso Daubmanno spaustuvėse katekizmai buvo spausdinami keliomis vietinėmis kalbomis (vokiečių, lietuvių, lenkų, prūsų). Šiuo straipsniu siekiama ištirti minėtą tematiką, nagrinėjant su tyrimo medžiaga susijusią Prūsijos Kunigaikštystės kalbinę aprėptį. Be to, ištiriant peritekstinius elementus, nustatyta, kaip leidybos proceso veikėjai pateikė savo darbo rezultatus tikslinei auditorijai. Ši analizė apima knygos dizainą, t. y. tokius aspektus kaip knygos apimtis, formatas ar puošiamieji elementai, iš kurių galima nustatyti, kokio prestižiškumo ar vartojamumo knygai buvo siekiama suteikti.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: Karaliaučius, Prūsijos Kunigaikštystė, katekizmas vietine kalba, ankstyvoji Naujųjų laikų knygų pramonė, Hansas Daubmannas, Hansas Weinreichas, Aleksandras Aujezdeckis, protestantizmas, liuteroniškoji Reformacija.

Received: 2022 12 19. Accepted: 2023 04 15

Copyright © 2023 Wojciech Kordyzon. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Despite its location at the periphery of early modern Europe, during the sixteenth century, Königsberg became a complex and linguistically diverse urban environment. Although it became the capital of a newly created state called the Duchy of Prussia in 1525, this role was not entirely new, as the city had previously been one of the main centres for the state of the Teutonic Knights. This state’s secular prince – Duke Albrecht – announced that he was a follower of Martin Luther. He decided to establish a national church that would be independent from Rome and free to implement the recommendations of Lutheran theologians regarding religious ceremonies.1

Prussia thus became a significant centre for the development of the Protestant culture in the region. The country’s relative distance from other German-speaking lands and its internal diversity also made it a sort of laboratory for the development of its own non-German vernacular cultures.2 This was achieved through the use of – among other tools – the medium of print. I propose to examine how the genre of catechism as a printed book was adapted to the needs of the new Lutheran devotion implemented in the Duchy of Prussia.3 This task was set by the main actor of the newly constructed religious system, the Duke of Prussia Albrecht, who thus became the main patron of the local printing industry, in terms of creating the conditions and incentives to develop printing in the regional languages as well as deciding to directly support the chosen initiatives. Keeping in mind that the Protestant education model appreciated vernacular communication, my aim is to pay particular attention to the actors responsible for providing vernacular books for the Prussian market. Apart from the printers, the activities of those actors who translated, published, compiled, edited, or – broadly speaking – prepared the vernacular texts for publication should be traced. To avoid overcomplicating the description of their multifaceted function, I use the general term ‘print agent’ to refer to these actors.4

The catechism, as a genre of basic religious education and pedagogy, was essential to shaping the new Lutheran piety constructed for the state religion. As such, it underwent constant negotiation between the various print agents influencing the production of books until it eventually reached a satisfactory level of stabilisation and wider acceptance among book producers.

Vernacular print agents must have had some conceptualisation of their work and – one may assume – implemented various strategies to achieve their goals, both those that were officially declared and those kept confidential (such as business goals). Vernacular catechisms, used as a rudimentary tool to spread the religious message, serve as an example of the constant efforts to print in the vernacular in the Prussian context. From this perspective, I seek to observe how the print agents planned their production in terms of linguistic coverage in the Duchy of Prussia and, via analysis of the peritextual elements of their books, how they presented their work to the recipients. Naturally, since this method limits my observations to the message intended to be publicly available to each reader, no hidden motives are revealed. However, such an approach remains informative, as it enables one to focus on the coherence and contents of the message received by the readers who were often unaware of the internal quarrels among the print agents. To deepen the analysis and to confront the declared goals found in the paratexts, I also include in my arguments the methods derived from other fields of book history, such as the aspects of book design, such as the volume, format, and decorations, which together indicate the intended book prestige and usage informing about the functions of the produced books. Finally, I seek to trace how the subsequent typographical solutions led to a stabilised form of printed vernacular catechisms.

Three printers active in the city in the 16th century shall be discussed. Hans Weinreich became the first permanent printer in the city in 1524. He served as a leading typographer in the city for over three decades.5 Aleksander Aujezdecki (also spelled Augezdecki) was invited to Königsberg from Prague in 1549. Because of his Czech origin, the Königsberg propaganda centre for Polish speakers saw Aujezdecki’s presence as an opportunity to develop and improve the technique of printing in vernacular Polish.6 However, he failed to win the competition with the enterprising Hans Daubmann of Nuremberg who came to Königsberg at Duke Albrecht’s invitation in 1554. Daubmann soon dominated the municipal book market. Formally, he was not allowed to print any material before obtaining approval from the Duke, the president of the Samland (Sambia) consistory, or the Rector and Senate of the Academy. In fact, Daubmann’s status lacked clear definition of the relationships between these actors and the right to censor his publications, which resulted in controversies between the pro-Osiandric Duke and anti-Osiandric academicians, with both parties accusing the printer of publishing undesirable texts. Nonetheless, these minor quarrels did not undermine the printer’s dominant position which was explicitly stated in another ducal privilege granted to Daubmann in 1564, providing the printer with the exclusive right to print in German, Latin, and Polish, as well as the permission to trade and import books from abroad. This privilege encompassed the entire territory of Ducal Prussia.7

Catechism as a printed genre – overview of vernacular editions in Königsberg

A distinctive feature of catechisms is their educational purpose, which makes them a medium that conveys the rudimentary knowledge of religion. Catechisms were used not only to teach religion but also as the very first readers for schoolchildren who were learning how to read and write in both vernacular languages and in Latin; this was often supplemented by the so-called ABCs. For the majority of early modern Christian confessions, catechisms became formative books that marked the first steps of religious education, and they were designed to give essential information on devotional practices, such as praying habits, raising children, or the conditions for receiving sacraments.8 What is significant, the word ‘catechism’ meant both abstract ‘basic articles of faith’ and a material object, a book containing these articles.9

Luther’s catechisms were published in 1529. The so-called Large Catechism was published under the title Deutsch catechismus. Later that same year, Luther prepared its shortened version which was printed as Enchiridion. The Greek word used in the title means ‘handbook’ or ‘something that one has on hand’. The Small Catechism was closely related to the catechetical broadsheet that was presumably published simultaneously, later known as the Haustafel genre. Thus, a small book containing comparable elements would be a portable, pocket-sized version of large sheets that were meant to be hung in visually accessible places in both churches and households. The functional distinction between small and large catechisms that had been introduced in Luther’s catechisms, later was frequently reproduced in subsequent books in this genre, regardless of their religious affiliation. While the small tomes were designed to provide information that was to be learned by heart, the large ones provided deeper insight into articles of faith, which was the next step in the reader’s religious education.

I estimate that the three printers – Weinreich, Aujezdecki, and Daubmann (including direct heirs who published as ‘Heirs of Hans Daubmann’ before Georg Osterberger, Daubmann’s son-in-law, took over the business in 1575) – produced over 500 editions between 1524 and 1575. Of this total, I have identified over 30 editions as vernacular catechisms edited in various languages. However, some of these remain unconsultable, as I was not able to find a surviving copy.10 Thus, I analysed a limited number of editions, the 21 publications that I was able to consult, many of which were unique copies preserved in the libraries of Germany, Lithuania, and Poland. The complete list of consulted editions can be found in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. List of consultable vernacular catechisms printed in Königsberg (1545–1574)

|

VD16 no. |

Year |

Title |

Printer |

Contributors |

Language |

Format |

No. of folios |

No. of sheet per one edition |

|

L 5342 |

1545 |

Katechismv text prosti dla prostego lvdv wkrolewczv |

Hans Weinreich |

Jan Seklucjan |

Polish |

8 |

8 |

1 |

|

L 5200 |

1545 |

Catechismus jn preüsznischer sprach vnd dagegen das deüdsche. |

Hans Weinreich |

unknown |

German, Old-Prussian |

4 |

8 |

2 |

|

L 5001 |

1545 |

Catechismus jn preüßnischer sprach gecorrigiret vnd dagegen das deüdsche. |

Hans Weinreich |

unknown |

German, Old-Prussian |

4 |

8 |

2 |

|

M 385 |

1546 |

Catechismvs To Iest Nauka Krzescianska od Apostołow dla prostich ludzi we trzech cząstkach zamkniona, y z drugiemi cząstkami ku teyże nauce krzescianskie przileżącemi |

Hans Weinreich |

Jan Malecki |

Polish |

8 |

8 |

1 |

|

not included |

1547 |

Catechismvs to iest nauka naprzednieisza y potrzebnieisza ku zbawyenyu o wierze krzescianskiey |

Hans Weinreich |

Jan Seklucjan |

Polish |

8 |

95 |

11,875 |

|

ZV 10050 |

1547 |

Catechismvsa prasty Szadei, Makslas skaitima raschta yr giesmes del kriksczianistes |

Hans Weinreich |

Martinas Mažvydas |

Lithuanian |

8 |

40 |

5 |

|

S 5406; S 5409 |

1549 |

CATECHISMVS to iest krotka a prosta starey wiary Chrzescianskiey nauka … Ktemu przydana krotka nauka czytania y pyssania. Jtem Oeconomia albo nauka wßelkiego stanu Ludziom potrzebna zpysma swietego. |

Hans Weinreich |

Jan Seklucjan |

Polish |

8 |

96 |

12 |

|

not included |

1552– 1556 |

[Small Catechism – copy partially preserved]* |

Aleksander Aujezdecki? |

unknown |

Polish |

8 |

16 |

2 |

|

O 1057 |

1554 |

Catechismus oder kinderpredig |

Hans Daubmann |

Andreas Osiander |

German |

4 |

114 |

28,5 |

|

K 155 |

1554 |

Catechismus Der Rechtgleubigen Behemischen Brüder, Welche der Antichrist mit seinem Gotlosen anhang verfolget, vnd auss Teuffelischem eingeben ... für Verfürer, Piccarden, vnd Waldenser, etc. schilt |

Hans Daubmann |

Johann Gyrk |

German |

8 |

120 |

15 |

|

K 156 |

1555 |

Catechismus Der Rechtgleubigen Behemischen Brüder Welche der Antichrist mit seinem Gottlosen Anhang verfolget vnd auß Teuffelischem Eingeben ... für Verfürer, Piccarden vnnd Waldenaser etc. schilt vnd lestert |

Hans Daubmann |

Johann Gyrk |

German |

8 |

120 |

15 |

|

H 5378 |

1555 |

Der Kleine Catechismus Mit vil schönen Sprüchen heiliger schrifft gegründet/ Für die Jugent zu gebrauchen |

Hans Daubmann |

Caspar Huberinus |

German |

8 |

103 |

12,875 |

|

B 7666 |

1556 |

Catechismus To iest zupelna nauka Chrześciańska … z pisma Prorockiego i Apostolskiego zniesiona ktory mozesz dobrze małą Biblią nazwać |

Hans Daubmann |

Johannes Brenz, Ostafi Trepka |

Polish |

4 |

308 |

77 |

|

V 672 |

1556 |

Upominek, ktory Vergerius jasnemu panu Mikolajowi, oswieconego pana Mikolaia Radźiwila, kxiąźęćia w Olice y Wnieswieżu … synowi pierwssemu, poslal. |

Aleksander Aujezdecki |

Pierpaolo Vergerio, Ostafi Trepka |

Polish |

8 |

24 |

3 |

|

not included |

1560 |

Das ander theil des Heyligen Catechismi, Das ist: Lehre und Bericht von der Heyligen Tauff, Beicht, Vergebung (oder Aufflösung) der Sünden, und dem Abentmal des Herren |

Hans Daubmann |

Johann Gyrk |

German |

4 |

40 |

10 |

|

O 1077 |

1561 |

Catechismus Albo Dziećinne Kazania o Nauce Krześćiańskiey, z Niemieckiego yezika na Polski pilnie przelożone … |

Hans Daubmann |

Andreas Osiander, Hieronim Malecki |

Polish |

4 |

210 |

52,5 |

|

L 5202 |

1561 |

ENCHIRIDION. Der Kleine Catechismus Doctor Martin Luthers Teutsch vnd Preussisch |

Hans Daubmann |

Abel Will |

German, Old-Prussian |

4 |

68 |

17 |

|

L 5343 |

1562 |

ENCHIRIDION. Catechismus Maly prze Plebany y kaznodzieie niedouczone y lud prosty |

Hans Daubmann |

Jan Radomski |

Polish |

8 |

72 |

9 |

|

S 5407; S 5410 |

1568 |

Catechismús To iest. Dziecinna á prosta náuká Chrzesciańskiey wiáry która Chrzesciáıski cźłowiek powinien wiedzieć y vmieć … Przydána teź iest náostátku Oeconomia káźdemu cźłowieku przynależąca |

Hans Daubmann |

Jan Seklucjan |

Polish |

8 |

104 |

13 |

|

ZV 4293 |

1569 |

ENCHIRIDION. Der Kleine Catechismus Doctor Martini Luth. gantz ordentlich inn Gesangweys, Sambt Andern Christlichen Liedern mit fleiß zusamen getragen. Mit einer schönen Concordantz vnd Zeiger der Heiligen Schrifft |

Hans Daubmann |

Hans Daubmann |

German |

8 |

176 |

22 |

|

L 5345 |

1574 |

ENCHIRIDION. Catechismus mály dla pospolitych Plebanow y Káznodzieiow |

Hans Daubmann |

Hieronim Malecki |

Polish |

8 |

68 |

8,5 |

The state-sponsored push for Lutheran evangelisation in the Duchy of Prussia supported the printers’ efforts to publish catechisms in various languages that were spoken in the country. Although a major part of catechization was conducted orally for the sake of illiterate adherents, the preachers and the literate heads of the family were encouraged to own a printed catechism as a foundation for the teachings they were intended to provide. The children who were taught the catechism were to remember it by heart, and their knowledge was later tested by their church teachers. The Kirchenordnung of 1558 explicitly recommended preaching the catechism from the printed version and respecting the languages spoken by the non-German groups in the city by providing the information in a language understandable to them.11

The indirectly recognised local ethnicities in the Duchy of Prussia were Poles, Lithuanians, Prussians, and Sudovians,12 though the last two groups were considered speakers of two variants of the same language. Vernacular catechisms, to some extent, reflected this diversity, yet all linguistic communities were not targeted equally. In terms of the number of editions, the catechisms in Polish were the most significant group, with 11 editions identified. Other non-German languages were significantly less represented. As the number of titles is not always the most comprehensive way to assess the size of book production, the volume in sheets per copy was also calculated for each edition (Fig. 1) and then amassed for each language (Fig. 2). It is clear that the total volume of Polish catechisms is almost double that of the second most represented language, German.

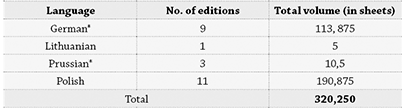

Figure 2. Number of editions and printing sheets of vernacular catechisms printed in Königsberg (1545–1574) by language.

* Note that all the Prussian editions are bilingual (with the accompanying German text), so each of these editions was counted in the table twice, while the volume in sheets was divided into two halves.

Dynamics

To grasp the development of catechisms in Königsberg, I have grouped the consulted editions into phases that are intended to illustrate the implementation of the catechetical genre by various print agents in the local book market. The first phase (ca. 1545–1549) refers to the innovative actions taken by Weinreich, who agreed to experiment with the little-tried (such as Polish) or so-far-non-existent (such as Lithuanian or Prussian) traditions of vernacular printing. Daubmann’s appearance in Königsberg eventually resulted in the displacement of his competitors. However, the print agents who previously collaborated with Weinreich and Aujezdecki adapted to the new dominant workshop. The process of their adaptation to the monopoly won by Daubmann constitutes phase two (1554–1556). Those events were followed by the third and fourth overlapping phases of activities (ca. 1561–1574). On the one hand, the print agents attempted to use the advantages of Daubmann’s technological potential, represented here by the third phase; simultaneously, they internally negotiated the previously introduced improvements to the texts in order to stabilise their form for further use (phase four).

Vernacular innovation and testing. The earliest catechisms printed in Königsberg were for the purposes of experimentation. Among them, no editions were prepared solely for the German-speaking community. These thus mark the earliest attempts to print catechisms in languages that did not yet have any established printing traditions or stabilised orthographic solutions, that is, in Lithuanian, Prussian, and Polish. At the time, print agents filled this gap in the industry and produced vernacular communication in the languages spoken within Prussia and its neighbouring states (such as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania). These printings increased the reach within the local communities of teaching that accorded with the new Protestant principles. These catechisms only loosely alluded to the structure of Luther’s text and thus should be considered original works.

The sizes of these earliest catechisms were rather inconsiderable. Seklucjan’s (Katechizmu tekst prosty…, 1545) and Malecki’s (Katechizmus, to jest Nauka krześcijańska…, 1546) first editions were little octavos, and only one sheet of paper was used to print them. Meanwhile, Prussian catechisms (Catechismus in preüßnischer sprach…, 1545; in two variants, the second of which was printed after minor corrections testifying to the ongoing work regarding how the Prussian language should be written) demanded double the number of sheets, as the bilingual text was accompanied by a German version. All of these booklets were intended to communicate the very basics of the faith, and introduced the Lord’s Prayer, the Decalogue, the Apostles’ Creed, and very brief information on the sacraments (i.e. Baptism and Eucharist) with scarce additional commentary.

In the foreword to his edition, Seklucjan clarified how he envisaged the use of the catechism. Introducing himself as a preacher in Königsberg for the Polish-speaking community (a job for which he was hired by the Duke), he declares that the articles of faith are intentionally printed without commentary so that they may be learned by heart, and it is assumed that their explanation will be provided in sermons and teachings by the church. Only later, he adds, will the text with commentary be provided as a printed book.13 Malecki, in his catechism, relied less on personal reading by the congregation members. His catechism was directed towards the learned preachers who were considered to be responsible for transferring the knowledge to the unlearned. His foreword ‘to all the pious priests of the Polish Churches’ (Omnibus piis parochis ecclesiarum Polonicarum) was printed in Latin. There, Malecki explains that the simple people should always be taught catechism in the same form.14 For this reason, he additionally provided a note in Polish before the colophon, addressing the printers ‘who are going to print this catechism in the future’ and urging them not to change ‘any word, syllable, nor point’.15 A similar mediated mode of using was designed for the Prussian catechism which targeted not the faithful themselves but their preachers: ‘With it [the catechism], every Sunday from the pulpit the parish priests should read it aloud word by word, without interpreting, and repeat with diligence for the non-German Prussian people in Prussian language’.16 Surprisingly, it seems that the only German-language catechism printed by Weinreich was the text accompanying the Prussian translation. For German speakers, books imported from the Holy Roman Empire were thus probably sufficient at the time.

As promised in 1545, Seklucjan soon published extended versions of his catechism. The editions in 1547 (Katechizmus, to jest Nauka naprzedniejsza…) and 1549 (Katechizmus to jest Prosta starej wiary … nauka …) were larger due to the expansion of commentary on the basic articles of faith. Still using the handy octavo format, these versions contained Seklucjan’s catechetical text on about 12 sheets. It seems that the growth of the catechism was a direct response to needs expressed by the community. In the foreword to the 1549 edition, Seklucjan introduces the additions, which he made after the previous edition was out of stock and there was still an audience willing to purchase the catechism. He notes that the book is for use by those who ‘are not living here near the congregation and cannot listen to the preaching all the time’.17 Whether or not the demands were real, Seklucjan thus emphasises how religious teaching can be achieved remotely through the medium of print and be used by those who do not have direct access to a vernacular preacher, thus expanding the projected audience of the booklet. Seklucjan often published his books and pamphlets, indicating himself as a sponsor of the print run, which means that no direct financial support of the Duke was provided. Even if neither of the earliest catechisms inform on the agent taking the financial burden of printing the catechisms, it is most likely that it was self-financed by Seklucjan.18

Both of Seklucjan’s expanded editions were provided with educational ABCs informing how the emerging Polish orthography was conceptualised in the printed text and how the words should be pronounced when read aloud. This reveals that the religious teaching was here strictly connected to the process of the rising literacy among the faithful who were given tools to practice their reading abilities (even if such a solution demanded the assistance of a literate person). For comparison, Prussian editions were not accompanied with the ABCs, though some remarks were made on the pronunciation differences between Prussian speakers from Natangen and Wehlau.19 These were, however, for the sake of the preachers and teachers, not the vernacular readers themselves. This was similar to the first catechisms by Seklucjan (1545) and Malecki (1546) which belong to the group of texts that were designed only to support learning the articles of faith by heart. Editions from 1547 and 1549 are thus examples of an emergent trend in the Prussian print market toward a more comprehensive approach that combined religious education with literacy.

The Lithuanian catechism (Katechizmusa prasty Szadei…, 1547) was, on the other hand, a more complex publication from the start, and the print agent responsible for its creation, Martynas Mažvydas (ca. 1520–1563), built upon the experiences of his Polish-speaking predecessors (Seklucjan and Malecki) when forming the structure (while the contents were derived from multiple sources: apart from the Polish predecessors, other Latin and German publication should also be named).20 Apart from the faith articles with brief commentary, Mažvydas included the Lithuanian ABCs (while using a structure analogous to that introduced earlier that year by Seklucjan) and a hymnbook (in fact, larger than the catechetical part, as it comprised both lyrics and scores). He addressed the book to ‘Lithuanians and Samogitians’, announcing the materialisation of teaching that ‘their fathers dreamed of and yet they could not have had it’.21 Such a statement presents him as belonging to the Lithuanian ethnicity and positions his endeavour as the fulfilment of many years of expectation. It also reveals Mažvydas’s awareness of the pioneering nature of the project – his catechism was the first work to be printed in Lithuanian. Thus, he conceptualised the origin of his work slightly more than Seklucjan did, who, despite all of the innovations he introduced, still used the language that had already been in print for at least 25 years. Mažvydas’s self-identity was also an opposite of an anonymous author of the Prussian catechism who seemed to be external to the community of Prussian speakers, not least because he also provided teaching material for those who were not necessarily of the Prussian descent.

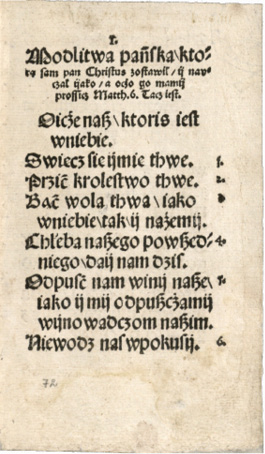

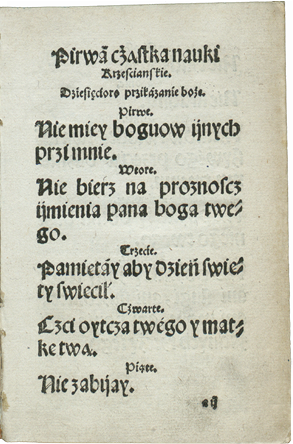

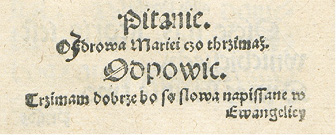

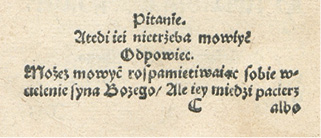

In terms of the typography and design, all the early catechisms mentioned above tended to be rather modestly decorated. For some editions (1545 in Polish, 1545 in Prussian; 1547 in Lithuanian), a decorative frame was provided on the title page; for others (1547, 1549 in Polish), letterpress two-tone printing in red and black was applied to chosen parts of the title page. Inside the books, no peculiar methods were used to increase their quality or attractiveness. However, there is some consistency in the general appearance of these publications. Weinreich employed similar typefaces for all the discussed editions and tended to diversify page composition and visually emphasise the contents by alternating between two font sizes (e.g. the content of the commandment in the Decalogue is in a larger font than is the commandment number; see Fig. 3). The page of the catechism by Malecki (Fig. 4) appears deceptively similar to Seklucjan’s, even though the two were rivals and Malecki’s intentions were polemical to Seklucjan’s.22 The famous disagreement over the Polish orthography is only suggested in the peritextual frame of the catechisms, while the book design and composition of catechisms printed by Weinreich created potential mutual resemblance in the eyes of the readers.

Figure 3. [SEKLUCJAN, Jan]. Katechizmu tekst prosty dla prostego ludu. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1545, fol. [5]r. Vilnius, Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka, L.16/61.

Figure 4. [MALECKI, Jan]. Katechizmus to jest Nauka krześcijańska od apostołów dla prostych ludzi. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1546, fol. [2]r. Toruń, Biblioteka Uniwersytecka, Pol.6.II.4 adl.

As it turned out, the coverage of non-German languages recognised in Prussia was unequal from the very beginning of catechetical and educational printing in the country. While the Prussian initiative was purely driven by basic catechisation purposes, and the Lithuanian edition offered a comparatively exhaustive tool built on several segments (in particular, the ABC, the catechism, and the hymnbook), the Polish print agents were in fact driven by internal dissent. Once Seklucjan published the first catechism with an adherent promise of an extended edition, Malecki soon replied with his own version and his own promise of a more extensive text (which, however, was never printed in Königsberg). This resulted in Seklucjan’s swift reaction; the next year, the previously announced larger catechism was ready to be disseminated. If Seklucjan’s own account is credible, only two years later, a second revised edition was demanded by potential readers. On the other hand, the printer did not make much of an effort to reflect this competitive relationship and applied a uniform typesetting to all publications falling into the category of catechism. This may mean that Polish print agents made it to outnumber the production of other vernacular actors, not only because of their own controversial purposes, but also because the reduced costs in terms of typesetting creativity was sufficiently profitable for the printing shop.

Building a single printing shop monopoly. Due to Daubmann’s arrival in Königsberg, the print agents needed to adapt to the new market conditions. Despite being active in the city from 1554, Daubmann was not in the avant-garde of the printing technology, yet he offered more modern typefaces than Weinreich and provided more diversified resources, so the choice of his printing shop, which also enjoyed the ducal support, seemed reasonable. However, Daubmann’s lack of experience with vernacular printing in languages other than German may have appeared to be a serious drawback.

In the beginning of his career in Königsberg, Daubmann printed four editions of catechisms in German. Two editions of the catechism by Johann Gyrk were printed for the Czech Brethren (the so-called Unity) and published in 1554 and 1555 (Catechismus Der Rechtgleubigen Behemischen Brüder…; the typesetting of the second edition was redone, but no significant content additions were included). These publications suggest that winning the support of this confessional group was considered one of the subjects of political-religious controversy in the region, and Daubmann’s press was one of the many tools used to achieve this, as their congregation was active in Neidenburg, and Gyrk was their minister. The confession of the Czech Brethren was also accepted by the Prussian theologians as not erroneous, which Gyrk emphasised in the foreword.23 The Brethren, as religious refugees from Moravia, thus found acceptance in the public sphere in Prussia, having received the opportunity to publish a catechetical instruction for their own use. As Margarita Korzo observes, the structure of the catechism was significantly modernised compared to the earlier catechetical texts used by the Czech Brethren and divided into clear sections.24 Similarly, Andreas Osiander’s catechism (Catechismus oder kinderpredig), published in 1554, was a sign of Albrecht’s support for this theologian who had been rejected by some scholars in the academy (despite Osiander’s death in 1552, the controversy continued for over a decade). Though it was not the first edition of the text, which had been previously published in other German printing centres (such as Nuremberg),25 the Königsberg edition was supplemented with a demonstrative prefatory letter by Duke Albrecht, famously Osiander’s protector, that in fact resembled the rules of teaching the catechism later formulated in the Church Order from 1558.26 The Duke indicates the need to standardise the tools for vernacular teaching, thus implicitly recommending the attached Osiander’s catechism as a basis for religious teaching.27 Surprisingly, this was the first attempt to provide such a tool in German, almost a decade after catechisms in the other languages used in Prussia had already been published. This indicates that Albrecht might have wanted to secure Osiander’s position as an orthodox theologian despite the ongoing controversy and simultaneously provide a model text for the parish priests.

Printing Huberinus’s catechism in 1555 (Der Kleine Catechismus…), on the other hand, might have been Daubmann’s own investment, yet it was still compatible with the Lutheran demands and the direction of his Prussian protectors. Daubmann had already published the same text twice before in Nuremberg (1549 and 1550).28 His Königsberg reprint can thus be understood as a demonstration of his skills for new potential users of his presses and the buyers of his books. Combined with his implementation of the policies of his patrons, this suggests an effort to build a stable position in the local market.

Even though Daubmann’s catechisms in German were designed as plainly as Weinreich’s, with modestly decorated title pages, a comparison of their format and volume can still draw some attention. While Gyrk’s and Huberinus’s catechisms were printed in octavo, which was typical for an instructional booklet, and needed 15 and approximately 13 sheets, respectively, per copy, the format and volume of Osiander’s catechism stands out. It was by far the most extensive catechetical book printed in Königsberg up to that time, and it consisted of approximately 28.5 sheets folded into a relatively large quarto.

Other non-German vernacular print agents decided to use the existing printing infrastructure for catechetical purposes some time later; the first to do so was a Lutheran preacher, Ostafi (Eustachy) Trepka, in 1556. It seems that he was to some extent testing the potential of the two printers active in Königsberg at that time, as he had also begun using Aujezdecki’s presses since the arrival of Daubmann. Aujezdecki printed Trepka’s translation of Pier Paolo Vergerio’s Lac sprituale (Upominek… – Mleko duchowne…, 1556), a small Bible-based narrated catechism designed for children. It seems to have been a side publication, benefitting from the presence of Vergerio in Prussia and his efforts to build a coalition that included Prussian Lutherans. Aujezdecki was limited to using only three sheets of paper per copy of the catechism. At the same time, Daubmann was given a much larger task (even though he had not printed any vernacular Polish text before 1556).29 Trepka translated the catechism by Johannes Brenz from Tübingen (Katechismus, to jest Zupełna nauka chrześcijańska…, 1556), the text of which applied the genre of the large catechism for the first time in vernacular Polish, while also providing detailed insight and commentary to the articles of faith and expanding the horizons encompassed by small catechisms. Printed in quarto, each copy demanded 77 sheets of paper. The edition is furnished with the ducal coat of arms, thus visually conveying the acceptance and support of Duke Albrecht. In addition, Albrecht himself informed Brenz of the translation, which suggests that he was interested in having this text translated.30 More information is delivered by the foreword. There, Trepka introduces Brenz as a scholar and a respectable preacher who created this catechism simply, honestly, and based on Holy Scripture. He notes that Brenz’s catechism contains everything that was not included in the previously published Polish catechisms and postils, thereby highlighting that the presented catechism can be thought of as a ‘small Bible’.31 Later, he reveals to the readers that the print run was financed by the Duke who was moved to finance the publication due to its necessity and utility. Moreover, the reader of the translated book need not necessarily live in Prussia; Trepka explicitly shares the Duke’s wish to disseminate the Lutheran thought in vernacular Polish in the Kingdom of Poland. The scope of the Polish-language catechetical printing is here defined not only for local use but also for export beyond the Duchy. The sources confirm that Trepka took care of the dissemination of the works he had translated or edited and on his own distributed the copies in Poznań.32

This example implies that Daubmann’s printing shop, which was committed to more time- and labour-consuming orders than was Aujezdecki’s, was valued as the more productive of the two. This is to some extent surprising, as Aujezdecki’s shop – led by a Slavic-speaking Czech printer – was likely to have initially been thought to be more suited to the needs of Polish print agents. However, it might have been the efficiency of Daubmann’s shop that changed their mind.

Quality enhancement. Once chosen to cooperate in serious undertakings with Daubmann, the vernacular print agents, perhaps inspired by the more confident and reliable printer, generally began to produce work of enhanced quality. Catechisms published in the 1560s were furnished with additional decorations, perhaps to make the books more appealing to the readers.

A Polish translation of Osiander’s catechism was published in 1561 (Katechizmus albo Dziecinne kazania…). The responsible print agent was Hieronim Malecki; however, he did not provide any individual testimony, such as a foreword. Instead, he is simply listed as the translator on the title page. The prefatory epistle from Duke Albrecht was included, as had been the case for the German edition published in 1554. It is the first of the Königsberg catechisms to be so richly decorated. First, the title page is printed with black and red letterpress. Second, the two-tone printing in red and black was used to highlight such material as the Decalogue. Third, the typographical frames, though simple, were considered decorative at the time and certainly demanded additional effort while typesetting, and these appear consistently throughout the entire book. Fourth, the catechism employs illustrations to decorate and emphasise the structural delimitations of the text.

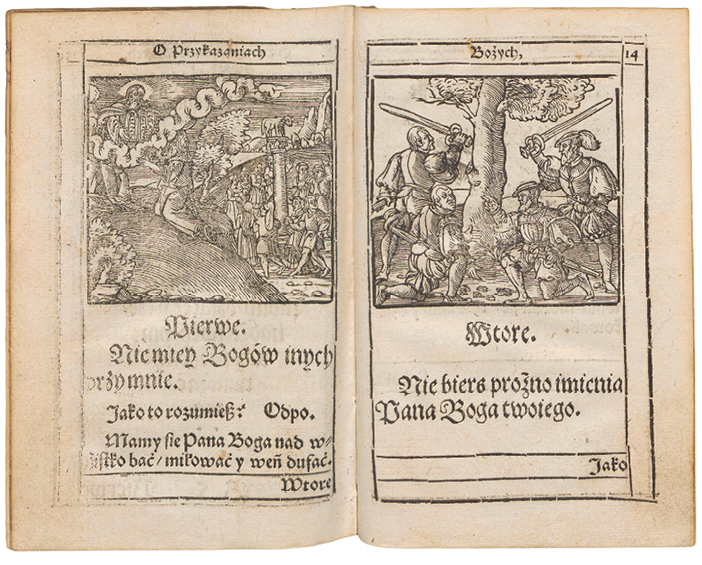

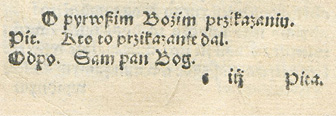

A year later, in 1562, the first exact translation of Luther’s small catechism was prepared by Jan Radomski and printed by Daubmann (Enchiridion. Katechizmus mały przez plebany i kaznodzieje…). The same methods to beautify the final product were used as previously: the two-tone printed title page in red and black, simple page framing throughout the entire book, and illustrations. In this case, the same woodblock set was used to decorate Enchiridion as was used for the previous project, Osiander’s catechism. A new level of quality was achieved: not only was the teaching in its scriptural form repeated after Luther, but the customary appearance of the small catechisms printed in the German cities of the Holy Roman Empire was fully imitated. The text was visually organised by the presence of related woodblock pictures impressed at the beginning of each section, followed by a headline title, and the question-and-answer structure was emphasised by using headlines to delimitate each part (Fig. 5). Additionally, a running title was placed at the top of each page to facilitate navigation of the book and potentially enable one to read the volume discontinuously. No foreword from the translator was provided; only Luther’s preface was reprinted in most of the original editions.

Figure 5. LUTHER, Martin; [RADOMSKI, Jan (transl.)]. Enchiridion. Katechizmus mały przez plebany i kaznodzieje… . Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1562, fol. 13v–14r. Gdańsk, PAN Biblioteka Gdańska, XX Bo 687.

The German Enchiridion of 1569 (Enchiridion. Der kleine Catechismus … gantz ordentlich inn Gesangweys…) is a somewhat different example of the same process. It reuses the illustration pattern encountered in the Polish catechisms from 1561 and 1562 but differs from the previous editions regarding the content. Most notably, it contains a broad collection of hymns. According to the foreword, the catechism was rewritten into verses by Daubmann himself. He also dedicated the book to the Danzig (Gdańsk) mayor and the members of the city council. It is possible that the book was also geared towards readers in Danzig (especially because Danzig languished without hymnbooks until two decades later, and this volume contained hymns potentially in response to that lack).33 Still, in Königsberg, the hymnbooks could have been much desired, too, as the Church Order of 1558 recommended that the catechism be sung during each divine service.34 More than 50 impressions illustrated the publication. The book also presents a variety of the printer’s capabilities: the typefaces are diversified, most of the hymns are provided with adherent musical scores, all the pages are framed, and marginal references are provided to facilitate use in accordance with an external source – the vernacular German Bible. In this way, the creation of a convenient and aesthetic catechetical hymnbook was achieved. In the same year in which the catechism was published, Daubmann was inscribed in the catalogue of the Frankfurt book fair.35 It is tempting to assume that a neatly prepared edition of the poeticised Enchiridion was distributed at the fair, thereby helping to promote Daubmann as a keen printer.

The introduction of illustrated catechisms in Königsberg is a significant innovation in terms of the local book design. It was not the lack of proper woodcut stock that had prevented Daubmann from earlier implementation. At least some of the woodblocks used to decorate the catechisms in the 1560s had already been in use in 1550, when the printer was still working in Nuremberg.36 Moreover, his position in Königsberg was already secure enough to invest in printing richly illustrated vernacular postils in 1556 and 1557, which was a costly market endeavour, even if subsidised by the Duke.37 It seems, then, that the quality enhancement might have been driven by more complex factors. This was the first time that illustrations were used for the Polish vernacular catechism. The market for catechetical instruction in Polish had grown since the 1540s – not only in Prussia and not only Protestant38 – so the Lutheran print agents may have wanted to offer not only more reliable texts but also more attractive books. However, the choice of titles was not necessarily connected to that need. It might have been a matter of prestige for Duke Albrecht to oversee both a translation of Osiander’s catechism, which would expand the audience of his protégé, and the first accurate translation of Luther’s Small Catechism, as it was one of the principal texts designating orthodoxy in early Lutheranism. Nothing is known about the involvement of the vernacular print agents in the process of choosing the illustrations. It would be most reasonable to assume that it was Daubmann who, as the printing executor, implemented the general illustration pattern for the catechetical texts published in 1561 and 1562 and that he then reused the very same pattern when publishing his richly decorated ‘signature’ hymnbook.

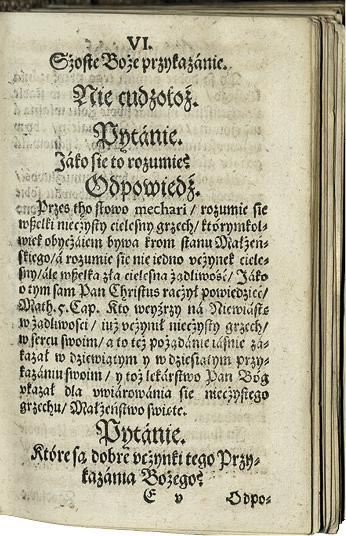

Genre stabilisation. In the late 1560s and early 1570s, along with the efforts to increase the quality of the produced books, the process of cementing the printed form of the catechism genre can be observed. At that time, print agents provided multiple versions of catechisms, as necessitated by updates and corrections, while preserving the general appearance of the books via a stabilised typesetting style.

In 1568, Seklucjan had his original catechism reprinted (Katechizmus, to jest Dziecinna a prosta nauka chrześcijańskiej wiary…). In the reprint, he introduced some minor textual changes and wrote a new preface (which did not provide any additional information about his intentions for the third edition). More importantly, the typesetting in the new edition seems to be more consistent than in the previous volumes. This exemplifies the trend toward clearer typographical solutions, which then became conventional over time. Local printers developed consistent ways of using these solutions to express the catechetical contents. Seklucjan’s catechism was a reedited and extended version of the text from 1549. In the 1549 edition, instructional questions and answers are introduced in at least four manners (high typefaces for the section title, regular typefaces for the section title, abbreviated inline section title, and indents, cf. Fig. 6). That changed substantially in the next edition in 1568: throughout it, information is introduced consistently, with larger typefaces to indicate headlines and smaller ones for the main text (Fig. 7). The application of such solutions most probably occurred without Seklucjan’s intervention, yet these updates prove the development and consolidation of the typesetting patterns that were expected to facilitate the text readability and clear delimitation and were specific to the catechism genre.

Figure 6. [SEKLUCJAN, Jan]. Katechizmus, to jest Krótka a prosta starej wiary chrześcijańskiej nauka. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1549. Warszawa, Biblioteka Narodowa, SD XVI.O.6247 adl.

Figure 7. [SEKLUCJAN, Jan]. Katechizmus, to jest Dziecinna a prosta nauka chrześcijańskiej wiary… . Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1568. Kórnik, PAN Biblioteka Kórnicka, Cim.O.292.

A tendency to stabilise the printed genre is also noticeable in Abel Will’s translation of Luther’s Enchiridion (Der kleine Catechismus … Teutsch und Preussisch). The translator was a Protestant minister in Pobethen (Samland). Published in 1561, the work preserves the structural solutions applied in the first Prussian catechisms in 1545: the publication is bilingual, with the German and Prussian content mirrored on the opposite pages. The original concept of teaching was also preserved, and the book seems to have been designed for those preachers who would teach in Prussian, and not the original speakers of this language, as indicated by the brief information on the pronunciation of vowels in Prussian (this was not, however, as detailed as the ABCs provided with the Polish and Lithuanian editions).39 The fact that this new Prussian catechism was presented as a faithful translation of Luther’s Small catechism is indicative of attempts to further standardise the instructional writings for vernacular groups in Prussia. As with the German and Polish editions of Osiander’s catechism, the Prussian translation of Luther was legitimised by a prefatory letter signed by Duke Albrecht that recognised the importance of communicating ‘single godly and heavenly teaching in many different languages.’40

A similar process is exemplified by the next Polish translation of Luther’s Enchiridion, which was prepared by Hieronim Malecki to replace the previous 1562 translation by Radomski. The first consultable edition comes with a reformulated title from 1574 (Enchiridion. Katechizmus mały dla pospolitych plebanów i kaznodziejów…; with a dedicatory letter dated in 1571 that suggests the existence of earlier editions not yet found). In his preface, Malecki explains, ‘There were some who had translated this catechism and whom I do not rebuke for their zeal, […] yet their Polish translations were imperfect, so I have gladly undertaken this work and […] translated it more accurately’.41 Surprisingly, Malecki is not strongly polemical towards his predecessor, and his statement declares his translation to be both perfected compared to Radomski’s and accurate enough not to require revision by successors. The entire book preserves the general appearance of the previous edition in terms of the typesetting style and the woodcut illustration disposition. By this visual resemblance, the new textual variant declared itself to be a continuation of the past endeavours, and the subsequent reprints of Malecki’s version testify to its stability. The same text was reprinted in a similar typesetting with analogous woodcut illustrations at least three times in the shops run by the heirs of Daubmann: Georg Osterberger and Johann Fabritius.42

Conclusions

The development of catechism as a printed genre in Königsberg was a process that took over 30 years of experiments, innovative additions, heated competitions, and the eventual stabilisation of the way the vernacular catechism was shaped in its printed form. The changes were dictated both by the usability of the object (that is, the navigation and readability of the textual elements) and by its decorative aspects. Even though such a process of adaptation a genre to its printed version was most likely influenced by multiple factors not discussed here, the example of the Prussian printing centre in Königsberg may still be an informative case study. Artefacts from the Königsberg printing industry enable the study of the evolving choices made by the Polish-speaking print agents who dynamically shaped the catechetical genre in their language. German editions seem to fulfil a complementary role to the publications imported from the Holy Roman Empire and the potent German-language printing centres. They served local political and theological goals, while the catechisms printed in Polish not only provided vernacular readers with access to texts, but also testified to the actions taken to establish a new means of expression in a language experiencing a transition to the relatively new medium of print. This eventually led to the standardisation of typesetting and book decoration that both facilitated the work of printers and fulfilled the readers’ expectations.

The development of the Lithuanian and Prussian vernacular printing in Prussia was less dynamic. The latter’s fate is rather sad, as the community of Prussian-speakers did not manage to preserve their language, and catechetical attempts by Lutheran preachers were not sufficient. The Lithuanian printed heritage, on the other hand, was mostly created by a single person, Mažvydas, whose heirs later published some of his remaining manuscripts, and later preacher Bartholomaeus Willentus. In sharp contrast, the lively Polish circle was in fact driven by its internal competition and the involvement of several print agents who both collaborated and jockeyed for position.

What is really striking almost all the vernacular catechisms printed in Königsberg should be considered the ‘small’ ones due to their contents. Only the Polish translation of Brenz’s work provides deeper insight into the articles of faith. In terms of the format and volume, a gradual trend towards more extensive and larger tomes can be observed. Even though it may come as no surprise due to the need to provide more precise instructions for the adherents, the overview also shows a tendency to build a comprehensive catechetical ‘toolbox’ targeting different virtual readers. While the earlier catechisms in the 1540s were brief and flexible to use, the 1550s bring pragmatic diversification: Brenz’s large catechism for the learned, Osiander’s catechisms that were basic yet insightful, or Vergerio’s Lac spirituale which was considered more rudimentary. From this perspective, the forthcoming standardisation towards Luther’s Enchiridion of the 1560s was a sign of setting clearer confessional boundaries yet it significantly limited the earlier diversification of the potential resources for teaching the religion.

Bibliography

Sources

1. BRENZ, Johannes; TREPKA, Ostafi (transl.). Katechizmus, to jest Zupełna nauka chrześcijańska … z pisma prorockiego i aspostolskiego zniesiona. Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1556. Biblioteka Narodowa, Warszawa, SD XVI.Qu.6467.

2. Catechismus in preüsznischer sprach und dagegen das deüdsche. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1545. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Libri impr. rari qu. 91.

3. [GYRK, Johann]. Catechismus der Rechtgleubigen Behemischen Brüder. Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1554. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 80.L.65 ALT PRUNK.

4. LUTHER, Martin, MALECKI, Hieronim (transl.), Enchiridion. Katechizmus mały dla pospolitych plebanów i kaznodziejów. Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1574. Sächsische Landes- und Universitätsbibliothek, Dresden, Theol.ev.gen.720.f,misc.2.

5. LUTHER, Martin; [WILL, Abel (transl.)]. Enchiridion. Der Kleine Catechismus Doctor Martin Luthers Teutsch und Preussisch, Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1561. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Libri impr. rari qu. 182.

6. [MALECKI, Jan]. Katechizmus to jest Nauka krześcijańska od apostołów dla prostych ludzi. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1546. Biblioteka Uniwersytecka, Toruń, Pol.6.II.188.

7. [MAŽVYDAS, Martynas]. Katechismusa prasty Szadei…, Könisgberg: Hans Weinreich, 1547. Biblioteka Uniwersytecka, Toruń, Pol.6.II.189 adl. 3.

8. OSIANDER, Andreas. Catechismus oder kinderpredig. Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1554. Biblioteka Narodowa, Warszawa, SD XVI.F.302 adl.

9. REJ, Mikołaj. Kupiec, to jest Kształ a podobieństwo Sądu Bożego ostatecznego. [Königsberg: Aleksander Aujezdecki], 1549. Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Kraków, St. Dr. Cim. 1526.

10. [SEKLUCJAN, Jan]. Katechizmu tekst prosty dla prostego ludu. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1545. Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka, Vilnius, L.16/61.

11. [SEKLUCJAN, Jan]. Katechizmus, to jest Krótka a prosta starej wiary chrześcijańskiej nauka, Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1549. Biblioteka Narodowa, Warszawa, SD XVI.O.6247 adl.

12. SEKLUCJAN, Jan. Pieśni duchowne a nabożne. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1547. Biblioteka Narodowa, Warszawa, SD XVI.O.6249 adl.

13. VOIGT, Johannes. Briefwechsel der berühmtesten Gelehrten des Zeitalters der Reformation mit Herzog Albrecht von Preußen. Königsberg: Gebrüder Bornträger, 1841.

Secondary literature

14. Aleknavičienė, Ona. Pirmasis Baltramiejaus Vilento Enchiridiono leidimas: terminus ad quem – 1572-ieji. Archivum Lithuanicum, 2009, vol. 11.

15. ARP, Ingrid. Hans Daubmann und der Königsberger Buchdruck in 16. Jahrhundert – Eine Profilskizze. In WALTER, Axel E. (ed.), Königsberger…

16. BOCK, Vanessa. Die Anfänge des polnischen Buchdrucks in Königsberg. Mit einem Verzeichnis der polnischen Drucke von Hans Weinreich und Alexander Augezdecki. In WALTER, Axel E. (ed.), Königsberger…

17. Braziūnienė, Alma. Martynas Mažvydas i początki słowa drukowanego na Litwie, Acta Universitatis Nicolai Copernici. Bibliologia, 2000, vol. 4(340).

18. BUCHWALD-PELCOWA, Paulina. Aleksander Augezdecki. Królewiec – Szamotuły 1549–1561(?), Wrocław: Zakład-Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1972 („Polonia Typographica Saeculi Sedecimi”, vol. 8).

19. GRENDLER, Paul F. Schooling in Renaissance Italy. Literacy and Learning 1300–1600. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1989. ISBN 9780801837258.

20. GUNDERMANN, Iselin. Die Anfänge der ländlichen evangelischen Pfarrbibliotheken im Herzogtum Preussen. Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte, 1974, vol. 110.

21. HUBATSCH, Walther. Geschichte der evangelischen Kirche Ostpreussens. Vol 1–3. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968.

22. JURKOWLANIEC, Grażyna. Postylle Arsatiusa Seehofera i Antona Corvinusa w przekładzie Eustachego Trepki. Addenda et corrigenda do badań nad początkami postyllografii w języku polskim, Terminus, 2020, vol. 22/1(54).

23. JURKOWLANIEC, Grażyna; HERMAN, Magdalena. Szesnastowieczny królewiecki druk w Herzog August Bibliothek w Wolfenbüttel: ilustracje, oprawa i właściciele. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki, 2021, vol. 83(2), p. 312–313.

24. KAWECKA-GRYCZOWA, Alodia; KOROTAJOWA, Krystyna (eds.), Drukarze dawnej Polski. Od XV do XVIII wieku. T. 4: Pomorze. Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1962.

25. KOLB, Robert. Pastoral Education in the Wittenberg Way. In BALLOR, Jordan et al. (eds.), Church and School and Early Modern Protestantism. Leiden: Brill, 2013. ISBN 9789004258280.

26. KOCIUMBAS, Piotr. Kancjonały luterańskiego Gdańska, 1587–1810. Studium nad źródłami lokalnej niemieckiej pieśni kościelnej. Warszawa: Sub Lupa, 2017.

27. KÖRBER, Esther-Beate. Öffentlichkeiten der frühen Neuzeit. Teilnehmer, Formen, Institutionen und Entscheidungen öffentlicher Kommunikation im Herzogtum Preußen von 1525 bis 1618. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1998. ISBN 3110156008.

28. KORDYZON, Wojciech. Rzymskie korzenie herezji. Słowo Boże w perspektywie historycznej. In: BIELAK, Alicja; KORDYZON, Wojciech (eds.). Figura heretyka w nowożytnych sporach konfesyjnych. Warszawa: Sub Lupa, 2017, p. 130-132.

29. KORZO, Margarita A. O tekstach religijnych w XVI-wiecznych elementarzach polskich, Pamiętnik Literacki, 2015, vol. 106(1).

30. KORZO, Margarita A. „Spis tento Otázek trojiech” Łukasza z Pragi: przyczynek do historii katechizmów braci czeskich i ich roli w piśmiennictwie polskim (XVI wiek – pierwsza połowa XVII stulecia), Res Historica, 2013, vol. 36.

31. LOHMEYER, Karl. Geschichte des Buchdrucks und des Buchhandels im Herzogthum Preussen, Archiv für Geschichte des deutschen Buchhandels, 1896, vol. 18.

32. LukŠaitė, Ingė. Kontinuität des Vorgehens von Protestanten und Katholiken bei der Änderung der Formen des Volks glaubens (letztes Viertel des 16. Jh.-1. Drittel des 17. Jh.). In Dolinskas, Vydas. Lietuvos krikščionėjimas Vidurio Europos kontekste. Vilnius: Lietuvos dailės muziejus, 2005.

33. MAŁŁEK, Janusz. Reformacja i protestantyzm w Polsce i Prusach (XVI–XX w.). Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2012. ISBN 9788323129882.

34. MICHELINI, Guido. Įvadas. In: Martyno Mažvydo raštai ir jų šaltiniai, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas, 2000. ISBN 5420014491.

35. PAWLIK, Wojciech. Katechizmy w Rzeczypospolitej od XVI do XVIII wieku. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL, 2010.

36. SHEVCHENKO, Nadezda. Eine historische Anthropologie des Buches. Bücher in der preußischen Herzogsfamilie zur Zeit der Reformation. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007. ISBN 9783525358832.

37. SILVA, Andie. The Brand of Print: Marketing Paratexts in the Early English Book Trade. Brill: Leiden, 2020. ISBN 9789004410237.

38. STANG, Christian. Die Sprache des litauischen Katechismus von Mažvydas. Oslo: J. Dybwad, 1929.

39. VOIGT, Johannes. Briefwechsel der berühmtesten Gelehrten des Zeitalters der Reformation mit Herzog Albrecht von Preußen. Königsberg: Gebrüder Bornträger, 1841.

40. WALTER, Axel E (ed.). Königsberger Buch- und Bibliotheksgeschichte (Aus Archiven, Bibliotheken und Museen Mittel- und Osteuropas: Editionen – Studien – Verzeichnisse). Bd. 1. Köln: Böhlau, 2005. ISBN 9783412085025.

41. WANDEL, Lee Palmer. Reading Catechisms, Teaching Religion, Leiden: Brill, 2015. ISBN 9789004305199.

42. WINIARSKA, Izabela. Słownictwo religijne polskiego kalwinizmu od XVI do XVIII wieku (na tle terminologii katolickiej). Warszawa: Semper, 2004. ISBN 9788389100559.

43. WINIARSKA-GÓRSKA, Izabela. The Impact of Lutheran Thought on the Polish Literary Language of the 16th Century. In KAUKO, Mikko et al. (eds.). Languages in the Lutheran Reformation: Textual Networks and the Spread of Ideas. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019.

44. WINIARSKA-GÓRSKA, Izabela. Szesnastowieczne przekłady Pisma Świętego na język polski (1551–1599) jako gatunek nowożytnej książki formacyjnej. Warszawa: Wydział Polonistyki Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2017. ISBN 9788365667656.

1 For the general overview of the religious and political changes in the Duchy of Prussia, see particularly: MAŁŁEK, Janusz. Reformacja i protestantyzm w Polsce i Prusach (XVI–XX w.). Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2012. HUBATSCH, Walther. Geschichte der evangelischen Kirche Ostpreussens. Vol. 1. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968.

2 Book production in Prussia with its cultural and societal implications was studied by a few researchers. For most recent comprehensive studies, see: SHEVCHENKO, Nadezda. Eine historische Anthropologie des Buches. Bücher in der preußischen Herzogsfamilie zur Zeit der Reformation. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007. WALTER, Axel E. (ed.). Königsberger Buch- und Bibliotheksgeschichte (Aus Archiven, Bibliotheken und Museen Mittel- und Osteuropas: Editionen – Studien – Verzeichnisse). Bd. 1. Köln: Böhlau, 2005. KÖRBER, Esther-Beate. Öffentlichkeiten der frühen Neuzeit. Teilnehmer, Formen, Institutionen und Entscheidungen öffentlicher Kommunikation im Herzogtum Preußen von 1525 bis 1618. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1998. Further and more specific bibliography can be consulted there.

3 Such an approach was proposed by Izabela Winiarska-Górska towards printed Bibles. See: WINIARSKA-GÓRSKA, Izabela. Szesnastowieczne przekłady Pisma Świętego na język polski (1551–1599) jako gatunek nowożytnej książki formacyjnej. Warszawa: Wydział Polonistyki Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2017.

4 For definition and justification of the term, see: SILVA, Andie. The Brand of Print: Marketing Paratexts in the Early English Book Trade. Leiden: Brill, 2020, p. 3–7.

5 For an overview of Weinreich’s activity, see: BOCK, Vanessa. Die Anfänge des polnischen Buchdrucks in Königsberg. Mit einem Verzeichnis der polnischen Drucke von Hans Weinreich und Alexander Augezdecki. In WALTER, Axel E. (ed.), Königsberger…, p. 129–134. KAWECKA-GRYCZOWA, Alodia; KOROTAJOWA, Krystyna (eds.), Drukarze dawnej Polski. Od XV do XVIII wieku. T. 4: Pomorze. Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1962, p. 447–462.

6 For an overview of Aujezdecki’s activity in Königsberg, see: BOCK, Vannessa. Die Anfänge…, p. 134–139. BUCHWALD-PELCOWA, Paulina. Aleksander Augezdecki. Królewiec – Szamotuły 1549–1561(?). Wrocław: Zakład-Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1972 (Polonia Typographica Saeculi Sedecimi, vol. 8). KAWECKA-GRYCZOWA, Alodia; KOROTAJOWA, Krystyna (eds.), Drukarze…, p. 17–34.

7 For overviews of Daubmann’s acitivty in Königsberg, see: ARP, Ingrid. Hans Daubmann und der Königsberger Buchdruck in 16. Jahrhundert – Eine Profilskizze. In WALTER, Axel E. (ed.), Königsberger…, p. 87–126. KAWECKA-GRYCZOWA, Alodia; KOROTAJOWA, Krystyna (eds.), Drukarze…, p. 70–91.

8 See more: KOLB, Robert. Pastoral Education in the Wittenberg Way. In BALLOR, Jordan et al. (eds.), Church and School and Early Modern Protestantism. Leiden: Brill, 2013, p. 75. GRENDLER, Paul F. Schooling in Renaissance Italy. Literacy and Learning 1300–1600. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1989, p. 338–362. WANDEL, Lee Palmer. Reading Catechisms, Teaching Religion, Leiden: Brill, 2015, p. 7–8.

9 WINIARSKA, Izabela. Słownictwo religijne polskiego kalwinizmu od XVI do XVIII wieku (na tle terminologii katolickiej). Warszawa: Semper, 2004, p. 146.

10 Several editions may be listed among the those that most probably had been printed (either due to more credible archival sources and historical bibliographical records of currently lost copies or less credible indirect mentions being the ground for further assumptions):

– three editions of earliest Polish translations before Seklucjan (from 1530, 1533, 1536; cf. BOCK, Vannessa. Die Anfänge…, p. 144, not found in VD16),

– 1567 reprint of Luther’s Enchiridion in Jan Radomski’s translation (first printed in 1562; cf. GUNDERMANN, Iselin. Die Anfänge der ländlichen evangelischen Pfarrbibliotheken im Herzogtum Preussen. Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte, 1974, vol. 110, p. 143–144),

– Polish translation of Luther’s Enchiridion by Hieronim Malecki (from 1571, edition assumed on the foreword date from the 1574 edition, VD16 L 5345),

– Lithuanian translation of Luther’s Enchiridon by Bartholomaeus Willentus from ca. 1572 (in fact editio princeps of the te known from the copy of a later Königsberg edition from 1579, VD16 L 5340; cf. Aleknavičienė, Ona. Pirmasis Baltramiejaus Vilento Enchiridiono leidimas: terminus ad quem – 1572-ieji. Archivum Lithuanicum, 2009, vol. 11, p. 129–130).

11 HUBATSCH, Walther. Geschichte der evangelischen Kirche Ostpreussens. Vol 3: Dokumente. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968, p. 100–101.

12 For example, the scholarships for studying at the local academy granted by the Duke were reserved for the representatives of these four ethnicities, see: Lukšaitė, Ingė. Kontinuität des Vorgehens von Protestanten und Katholiken bei der Änderung der Formen des Volks glaubens (letztes Viertel des 16. Jh.-1. Drittel des 17. Jh.). In Dolinskas, Vydas. Lietuvos krikščionėjimas Vidurio Europos kontekste. Vilnius: Lietuvos dailės muziejus, 2005, p. 274.

13 [SEKLUCJAN, Jan]. Katechizmu tekst prosty dla prostego ludu. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1545, fol. [2]r: ‘Przetom wam naprzód sam tekst katechizmu krom wykładu dał wydrukować, abyście się go nauczyli a w kościele na kazaniu pilno wykładu słuchali. Potym, jeśli nam Pan Bóg raczy użyczyć zdrowia, dam wam wespółek i z wykładem, którego was uczę, w drukarni wytłoczyć ku waszej i waszym potomkom nauce i wiecznej pamiątce.’ Citations from the early printed sources are given in the modernised transcript and modern punctuation.

14 [MALECKI, Jan]. Katechizmus to jest Nauka krześcijańska od apostołów dla prostych ludzi. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1546, fol. [1]v: ‘Homines simpliciores, et qui natu minores sunt, non possunt catechismum feliciter doceri, quam una atque eadem forma sepius proposita, ita ut ne una quidem syllaba immutotur. Nam si iam istis, iam aliis verbis eadem docebimus, facile perurbantur simpliciores animi, et peribit omnis opera quam in docendo ponimus, id quod re ipsa compertum esse videmus.’

15 Ibidem, fol. [8]r: ‘Proszę wszytkich impresorów, którzy ten katechizm będą potym wybijać, aby k temu nic nie przydawali ani odejmowali, ani żadnego słowa, sylaby, punktu odmieniali, ale wszytko w całości swe zachowali. Bo my dobrze wiemy, cośmy uczynili, a jakośmy wyłożyli a położyli. Widziemy też, co inni w tym uczynili.’

16 Catechismus in preüsznischer sprach und dagegen das deüdsche. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1545, fol. A2r: ‘Damit [= dem Catechismus] die pfarherrn … denselbigen alle Sontage von der Cantzel von wort zu wort one Tolken selbs ablesen und dem undeüdschen preüßnischem volcke in derselbigen sprache mit fleys fürsprechen söllen.’

17 [SEKLUCJAN, Jan]. Katechizmus, to jest Krótka a prosta starej wiary chrześcijańskiej nauka, Königsberg: Han Weinreich, 1549, fol. a2r: ‘którzy sami nie mogą obecznie przy nas mieszkać, a kazania ustawicznie słuchać.’

18 Seklucjan informs, for instance, that investment was his own in the hymnbook from 1547 (cf. SEKLUCJAN, Jan. Pieśni duchowne a nabożne. Königsberg: Hans Weinreich, 1547, p. 5: ‘ty święte pieśni […] dałem wydrukować nakładem swym’) and he got into debt to finance the print run of a Polish translation of Naogeorg’s Mercator (cf. REJ, Mikołaj. Kupiec, to jest Kształ a podobieństwo Sądu Bożego ostatecznego. [Königsberg: Aleksander Aujezdecki], 1549, fol. a6r: ‘nakładu nie lutując, że wam dał ty książki w drukarni wytłoczyć, i zadłużyłem się o półtora sta złotych, krom pracej i korygowania, ale o to nic nie dbam’).

19 Cf. Catechismus in preüsznischer…, fol. [2]r.

20 Braziūnienė, Alma. Martynas Mažvydas i początki słowa drukowanego na Litwie, Acta Universitatis Nicolai Copernici. Bibliologia, 2000, vol. 4(340), p. 54–55. On the contents, see: STANG, Christian. Die Sprache des litauischen Katechismus von Mažvydas. Oslo: J. Dybwad, 1929; MICHELINI, Guido. Įvadas. In: Martyno Mažvydo raštai ir jų šaltiniai, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas, 2000, p. 10.

21 [MAŽVYDAS, Martynas]. Katechismusa prasty Szadei…, Könisgberg: Hans Weinreich, 1547, fol. A4v: ‘Knigeles paczias byla Letuvininkump ir Szemaicziump: | … | Maksla schito tewai iusu trakszdawa tureti | Ale to negaleia ne venu budu gauti.’

22 WINIARSKA-GÓRSKA, Izabela. The Impact of Lutheran Thought on the Polish Literary Language of the 16th Century. In KAUKO, Mikko et al. (eds.). Languages in the Lutheran Reformation: Textual Networks and the Spread of Ideas. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019, p. 89–94.

23 [GYRK, Johann]. Catechismus der Rechtgleubigen Behemischen Brüder. Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1554 fol. ***4v.

24 KORZO, Margarita A. „Spis tento Otázek trojiech” Łukasza z Pragi: przyczynek do historii katechizmów braci czeskich i ich roli w piśmiennictwie polskim (XVI wiek–pierwsza połowa XVII stulecia), Res Historica, 2013, vol. 36, p. 111–112.

25 E.g., editions from Nuremberg from 1533 to 1543: VD16 O 1036 to VD16 O 1051.

26 Cf. HUBTASCH, Walther. Geschichte…, vol. 3, p. 100.

27 OSIANDER, Andreas. Catechismus oder kinderpredig. Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1554, fol.) (3v: ‘Dieweil denn sölche Ordnung der Kinder leere in allen obgedachten Herrschafften der gestalt angenommen und von allen der Augsburischen Confession verwanten bisher hochgehalten, haben wir dieselben in unsern Kirchen auch für stellen wöllen, das man zu ördentlichen zeiten, wie das in der Visitation oder sönsten an einem jeden ort nach gelegenheit wird geordnet werden, dem gemeinem Mann und der armen Jugend eine Predigt auff eine lection nach der ordnung furlese und wenn sie alle gelesen, das man wider vorn anfahe, damit also einerley leer stetigs den Unerfarnen fürgetragen werde, und sie nit durch newerung verirret.’)

28 VD16 H 5371 (Nuremberg 1549; edition furnished with woodcuts not included in the Königsberg edition). Cf. also the Nuremberg edition of a large catechism by Huberinus: VD16 H 5372 (Nuremberg 1550).

29 The other Polish texts printed in 1556 were: Stanisław Lutomirski’s confession (VD16 L 7645) and postils edited by Trepka (cf. JURKOWLANIEC, Grażyna. Postylle Arsatiusa Seehofera i Antona Corvinusa w przekładzie Eustachego Trepki. Addenda et corrigenda do badań nad początkami postyllografii w języku polskim, Terminus, 2020, vol. 22/1(54), p. 1–17).

30 Cf. VOIGT, Johannes. Briefwechsel der berühmtesten Gelehrten des Zeitalters der Reformation mit Herzog Albrecht von Preußen. Königsberg: Gebrüder Bornträger, 1841, p. 56.

31 BRENZ, Johannes; TREPKA, Ostafi (transl.). Katechizmus, to jest Zupełna nauka chrześcijańska … z pisma prorockiego i aspostolskiego zniesiona. Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1556, fol. [2]v: ‘ten katechizm małą Biblią nazwać możesz, w którym tyż tu wiele najdziesz, czego wszyscy postyllarze i ci, którzy przedtym katechizmy pisali, nie dołożyli.’

32 For the sources confirming the dissemination of books edited by Trepka, see: JURKOWLANIEC, Grażyna; HERMAN, Magdalena. Szesnastowieczny królewiecki druk w Herzog August Bibliothek w Wolfenbüttel: ilustracje, oprawa i właściciele. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki, 2021, vol. 83(2), p. 312–313. KORDYZON, Wojciech. Rzymskie korzenie herezji. Słowo Boże w perspektywie historycznej. In: BIELAK, Alicja; KORDYZON, Wojciech (eds.). Figura heretyka w nowożytnych sporach konfesyjnych. Warszawa: Sub Lupa, 2017, p. 130–132.

33 KOCIUMBAS, Piotr. Kancjonały luterańskiego Gdańska, 1587–1810. Studium nad źródłami lokalnej niemieckiej pieśni kościelnej. Warszawa: Sub Lupa, 2017, p. 45–49.

34 KÖRBER, Esther-Beathe. Öffentlichkeiten…, p. 193.

35 LOHMEYER, Karl. Geschichte des Buchdrucks und des Buchhandels im Herzogthum Preussen, Archiv für Geschichte des deutschen Buchhandels, 1896, vol. 18, p. 108.

36 Several impressions found in the catechisms were made from the same woodblocks as in VD16 A 1626, VD16 ZV 5617, VD16 C 1820.

37 E.g., VD16 E 4611 and VD16 C 5361.

38 Due to the loss of such highly usable objects as catechisms, it is often assumed that many editions would remain unknown (cf. KORZO, Margarita A. O tekstach religijnych w XVI-wiecznych elementarzach polskich, Pamiętnik Literacki, 2015, vol. 106(1), p. 169; the researcher operates mainly on fragments which illustrate the problem well). For the general numbers of the printed catechetical text at the time, cf. PAWLIK, Wojciech. Katechizmy w Rzeczypospolitej od XVI do XVIII wieku. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL, 2010, p. 270–271 (yet note that the quoted study was not aiming at assessing the scope of Protestant editions, so Pawlik’s estimations in this regard are rather unreliable).

39 LUTHER, Martin; [WILL, Abel (transl.)]. Enchiridion. Der Kleine Catechismus Doctor Martin Luthers Teutsch und Preussisch, Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1561, fol. B1r.

40 Ibidem, fol. [3]r

41 LUTHER, Martin, MALECKI, Hieronim (transl.), Enchiridion. Katechizmus mały dla pospolitych plebanów i kaznodziejów. Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1574, fol. A8v: ‘Bo acz niektórzy ten też katechizm na polski język wyłożyli, których ja przychylności w tym nie ganię …, ale iże jeszcze niedoskonale i nie wszystek na polski język był przełożony, przetoż tę pracę radem podjął i czegokolwiek oni w wyłożeniu na polski język nieprawie doszli i niedoskonale wyłożyli, tom ja to wszystko pilniej i wierniej wyłożył, dopełnił i dokończył.’

42 Reprints by Osterberger in 1588 (VD16 L 5345) and 1593 (VD16 L 5346), by Fabritius in 1615 (VD17 12:740759Z). Note that Osterberger also reprinted the German original in 1596 (published as Enchiridion. Der kleine Catechismus für die gemeine Pfarherr und Prediger).