Kriminologijos studijos ISSN 2351-6097 eISSN 2538-8754

2018, vol. 6, pp. 86–100 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/CrimLithuan.2018.6.5

Victims of Parental Kidnappings in Light of Polish Criminal Law (Based on the Results of Case Law Research)

Diana Dajnowicz-Piesiecka, PhD

Department of Criminal Law and Criminology

Institute of Criminology, Faculty of Law, University of Bialystok

d.dajnowicz-piesiecka@uwb.edu.pl

Abstract. This paper concerns the victims of parental abductions in Poland. The aim of the article is to present the victims of parental abductions in the light of the Polish criminal case law. The study has an empirical character because it presents the results of research carried out using a criminal case law analysis. The study included 59 criminal cases concerning the parental kidnapping of a child. The research revealed that the Polish law treats the person from whom the child was kidnapped as a victim of parental kidnapping. Interestingly, the child is not considered a victim. Based on the research, a conclusion was formulated that parental abductions are not only the result of disputes between the parents of a child, but that children can also be abducted from the care of other people, for example, the directors of orphanages or grandparents who look after the children. This article argues that parental abductions are not only a problem for families but also for institutions professionally involved in childcare.

Keywords: parental abductions, victim, child, crime against family and care, case law research.

Received: 14/6/2018. Accepted: 7/11/2018

Copyright © 2018 Diana Dajnowicz-Piesiecka. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction and Overview

Parental abductions are usually defined as the “taking, retention, or concealment of a child or children by a parent, other family member, or their agent, in derogation of the custody rights, including visitation rights, of another parent or family member” (Girdner 1994, p. 1–11). In the era of globalization and the disappearance of state borders, parental kidnappings are one of the most serious social and legal problems. In Europe, parental abductions are one of the main causes of missing children (Missing Children Europe 2016, p. 2). More importantly, children are sometimes abducted and brought to other countries. This proves that parental abductions are not just a regional problem, with which only the Polish judicial system fights, but a transnational issue that goes beyond state borders.

In Poland, this issue becomes substantial and more pressing. Nevertheless, the Polish definition of parental kidnappings differs from the definition that was created by L. K. Girdner. These differences arise from the fact that the same behavior is implemented in different countries, different legal systems and different societies. In Poland, the situation when a parent kidnaps their child against the will of the other parent (who is appointed at the time as the child’s carer), or against the will of another person appointed at the time as the minor child’s carer, is defined as parental kidnapping or parental abduction (Dajnowicz-Piesiecka 2017, p. 23). In the Polish interpretation of the problem, the person indicated to care for the child is significant. The will of this person and their acting in accordance with this will determine whether the parental abduction really took place.

Parental kidnappings are a significant problem in Poland, creating a challenge for the Polish legislator and the judiciary. Some European countries, such as Spain, Great Britain or Lithuania, consider parental kidnapping as a separate, independent crime. However, the Polish Criminal Code does not include parental abduction as a separate offense. Criminal liability for parental kidnaping is borne on the basis of Art. 211 of the Polish Criminal Code (CC). This regulation defines the child abduction offense without specifying the perpetrator’s category. It means that this legal provision applies to both the parents and to perpetrators unrelated to the child. This regulation reads as follows: whoever abducts or detains a minor person under 15 years of age or a person who is helpless due to his or her mental or physical condition against the will of the person appointed to take care of or supervise [the child] shall be subject to the penalty of deprivation of liberty from 3 months to 5 years.

A part of the Polish scientific community, as well as practitioners of the law and the Children’s Ombudsman, often appeal to the Polish legislator for an amendment to the penal code. This amendment would introduce a separate offense of parental kidnapping into the criminal code. This solution was made by the Lithuanian legislator, who points out, in Paragraph 2 of Article 156 of the Lithuanian Criminal Code, that a father, mother or a close relative who abducts their own or their relatives’ young child from a children’s establishment or from a person with whom the child lawfully resides shall be punished by community service, by a fine, by restriction of liberty, by arrest or by imprisonment for a term of up to two years. However, until now, the Polish legislator has not established any separate penalization for parental abductions. This was explained by the fact that there already exists a possibility to be charged with parental kidnapping under a general provision of the criminal code defining the kidnapping of a child.

The interesting thing is that Art. 211 of the Polish Criminal Code directly protects the will of the person indicated as a carer or supervisor of a child but not that of a minor. On the basis of this provision, it is stated that the victim of a child abduction crime is precisely the person designated to care or supervise the minor, against the will of which the perpetrator may abduct or detain the child.

It is important for the problem of parental abductions and their victims to determine who falls victim to this behavior most often and whose will is not respected by the perpetrator of the crime. The media, not only in Poland, most often show that parental abductions are related to divorce cases and disputes between parents about their children – one of the parents being the offender, and the other parent the victim. The aim of this study is to show that this topic is more complicated than it seems, and that in the Polish public discourse, the victim of parental abduction is not always one of the parents.

The investigation regarding from whom the child is most often kidnapped is connected with the fact that mass media show parental abductions as an aftermath of quarrels between parents about the scope of their parental authorities or about accusations related to divorce. In response to this stereotype, the author of this article formulated the hypothesis that parental abductions go beyond the area of parental conflicts and do not always violate the legal right of one of the parents. After all, a child is not always looked after by their parents – children are sometimes adopted or live in orphanages. They may also still have biological parents who can also commit a parental abduction.

Methodological Assumptions of the Research

This article presents a part of the results of a research that the author of this study carried out. A scientific examination of parental kidnappings proved necessary, as this problem has been growing in Poland yet so far has not been investigated by lawyers or criminologists. There are only a few articles about parental kidnappings in Polish literature, and only three of them have an empirical character (Kołakowska-Przełomiec 1995; Buczkowski, Drapała 2013; 2014).

The lack of scientific studies on parental abductions, while the problem is constantly intensifying, revealed the need to develop scientific knowledge about the title issue. For this reason, the author of the article has carried out the examination of the files of court cases for the offense specified in Art. 211 CC, in which the child’s parents were the perpetrators of the kidnapping.

The research was accomplished in connection with a scientific project called “Parental Child Abduction in Light of Polish Criminal Case Law: Legal and Criminological Aspects” (No. 2014/15/N/HS5/02688). The project was financed by the National Science Centre – one of the most important state-owned research funding agencies in Poland. The author of this article was the grant’s manager and carried it out during the period of 2015–2017 under the supervision of Professor Emil W. Pływaczewski. The doctoral dissertation of the author of this article was written as a result of this research grant. The first monograph about parental kidnappings in Poland, titled Parental Abductions in Legal and Criminological Terms, was developed on the basis of that dissertation.

The court case investigations concerned cases that took place between September 1, 1998 and December 31, 2014, examined in 36 Polish district courts across 18 Polish provincial cities. Courts located in provincial cities were selected for the study because they are spread throughout Poland, and thanks to that, it was possible to collect information about the situation of parental kidnappings depending on the location in particular regions of the country. Although not all Polish cases of parental kidnappings were examined, the analysis of these court cases allowed the author to understand the specificity of parental kidnappings in Poland. It may not be necessary to examine all court cases to comprehend the typical circumstances and characteristics of the cases (Maxfield, Babbie 2008, p. 334).

In the period from September 1, 1998 to December 31, 2014, in 36 courts, where the research was conducted, 99 child kidnapping cases were examined based on Art. 211 CC. Fifty-nine of these cases concerned parental kidnappings. In the other 40 cases, the perpetrators were people other than the parents – mainly those who were related to the kidnapped child (for example, grandparents, aunts or uncles). The remaining 59 cases of parental kidnappings constituted the entire research material for the project.

In general, the research methods can be divided into two somewhat different domains called quantitative research methods and qualitative research methods (Bachman, Schutt 2011, p. 16). The project used the court case study method, which combines the examination of quantitative and qualitative information. Court cases are characterized by high cognitive value; they show the actual operation of institutions applying the law and provide important information about social events regulated by law. The court case study was conducted using a quantitative method, supplemented by a qualitative method, which is common in research in social sciences (Juszczyk 2005, p. 27).

The research tool was a questionnaire. The questionnaire contained 17 open questions to provide information on qualitative analysis. In addition to open questions, the questionnaire contained 95 questions that were used for quantitative analysis. The questions in the questionnaire were divided into seven main topics concerning general information about the case, information about the perpetrators, information about the victims, information about kidnapped minors, information about the criminal act committed by the offender, information on evidence in the case and information on court proceedings. This study was created based on the research results obtained as part of the questions from the part devoted to the victim of crime.

Victims in Light of the Research Results

In research, pursuant to Art. 49 § 1 and 2 of the Polish Code of Criminal Procedure, it has been assumed that the victim is a natural person, a legal entity, a state institution, a self-governing institution or another organizational unit whose legal interest has been directly violated or threatened by a crime.

The legal good that is violated or threatened by a crime specified in Art. 211 CC is the will of the person appointed to take care of or supervise a minor under 15 years of age. Therefore, in cases of parental kidnappings, a victim is a person who has been appointed the custody or supervision over a minor and who experiences a direct violation or threat of this right to care or supervise through the offense specified in Art. 211 CC. Therefore, while only a mother or a father of a child could be the perpetrators of parental kidnapping, anyone appointed to look after the child can be a victim.

Parental abductions seem to be a family problem, especially related to the parents who are in conflict with each other, but the court cases of parental kidnappings prove that this is not true. Parental abductions constitute a problem that goes beyond the area of parental conflicts. These are complicated situations in which the victims could also be people other than the child’s mother or father. Information on this subject is presented in the chart below; it shows who was a victim of a parental abduction in the examined cases.

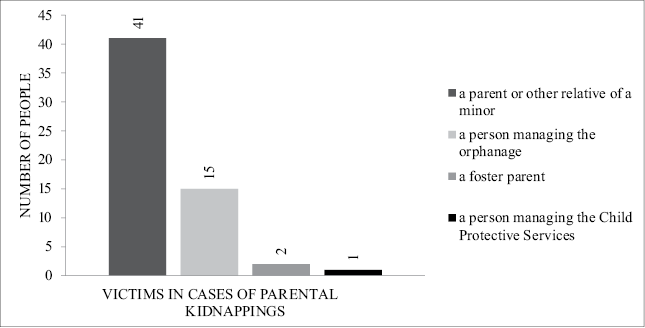

Chart 1. Victims in cases of parental kidnappings

The graph shows that the minor’s parent or another relative was the most frequent victim (a detailed description of the structure of people in this area is presented in Chart 2). In 41 cases (69% of examined cases), the victim of a child abduction was the child’s parent or another related person who was indicated to care for the minor during the offence. In 15 analyzed cases (25%), the head of the orphanage was also the victim. In these 15 cases, children were abducted from the orphanage, where the head of the orphanage performed legal protection over children (on the basis of Art. 1121 of the Polish Family and Guardianship Code). The head of the orphanage was obliged and entitled to carry out the current custody of the child placed in the orphanage as well as to raise that child, to represent his or her interests and to obtain the benefits intended to meet the child’s needs.

In the next 2 cases (4%), the victims of parental kidnapping were foster parents. In one case (2%), the victim was a person managing the Child Protective Services. The child has been placed in this facility because of demoralized behavior – the minor committed a punishable act and the family court proceeded in his case.

In those cases, in which the head of the orphanage, the foster parents and the head of the Child Protective Services were victims, the biological parents have been restricted or deprived of parental rights. The circumstances of the restriction or deprivation of parental rights were varied. In one case, in which the head of the orphanage was the victim, the parents did not abduct their daughter, but they had detained her in their home. The perpetrator’s daughter escaped from the orphanage to the family home because she was getting involved in quarrels with other children in the establishment. The parents decided to keep the girl at home instead of informing the manager of the orphanage about the incident. When asked, they lied to the police that the child was not with them. That way, they prevented the head of the orphanage from taking care of the child, which was his obligation imposed by the family court (case from the District Court in Białystok, reference number: III K 1754/06).

An interesting issue was also one in which the foster parents were the victims. The child was placed in a foster family, as the biological parents were struggling with alcohol addiction and neglecting their parental responsibilities. The social workers had assessed the family as dysfunctional and threatening the good of the minor. The girl was placed in a foster family, but the biological parents could meet her when the court allowed it and set dates for meetings. After some time, the girl’s parents had requested to have more meetings, because they did not agree with having to limit their contact with the child. Upon the court’s refusal, they decided to kidnap the girl. When the child was on a walk with her foster father, the biological parents attacked him and then escaped with the child. Then, they hid from both the police and the foster parents. The police, however, found them, and the child returned to the care of the foster family (case from the District Court in Kielce, reference number: IX K 1016/10).

The parents and relatives of minors are the largest group of victims. The graph below shows how the structure of this group of people was shaped.

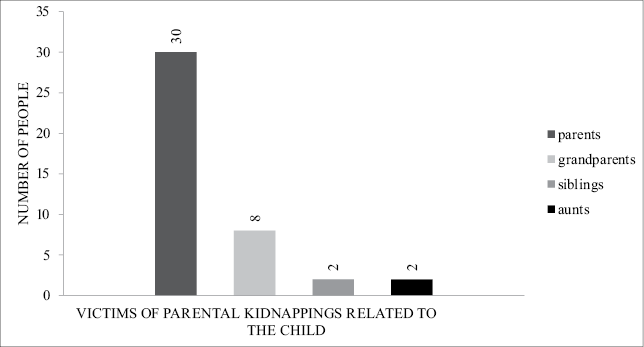

Chart 2. Victims of parental kidnappings related to the child

The data from the chart above show that in the majority of examined cases, children were abducted and taken away from one of their parents. Among the victims were 30 parents of a kidnapped minor. This means that almost half of the parental kidnappings were caused by misunderstandings between the parents of the child.

Grandparents were also victims in the examined cases. In the studied cases, there were 8 such persons (they constituted 13% of all victims). Among the other victims were 2 siblings of kidnapped children (3% of the entire group of victims) and 2 aunts of kidnapped children (3% of the group of victims).

In most cases, one of the parents was a victim because the other parent took the child against the will of the first one. These parental abductions were motivated by a conflict on the way and frequency of having contact with the child. The perpetrating parent usually wanted to meet their child on any day and for any period of time and did not respect the court’s decisions and agreements with the other parent. The wish to meet the child in an arbitrary and uncompromising way, inconsistent with previous decisions made by the court, was a very common reason for parental kidnappings (Dajnowicz-Piesiecka 2017, p. 195).

Different motivations occurred in cases in which grandparents, siblings or aunts were victims. Grandparents were victims because their grandchildren were kidnapped from their care, after the courts have chosen them for legal guardians of children. Grandparents were appointed to care for children because the parents of these children were irresponsible, neglected their children and even harmed them.

In one of the cases, the victim was a grandmother of a minor girl. The child was taken away from her parents and transferred to the grandmother’s care by the family court because both the mother and the father were suffering from alcohol addiction.

The grandmother took great care of her minor granddaughter. The girl was happy, she attended school and settled in among her peers. When the grandmother found out that the girl’s parents had separated, she agreed to let the girl’s mother live in her residence. For some time, the grandmother, the girl’s mother and the girl lived together. However, the father of the child wanted his wife and daughter to come back to him; he argued that he would heal his addiction and that he wanted to rebuild the family. The girl’s grandmother did not agree for the child to move back in with her father, while the woman still remained the legal guardian of the girl and had the exclusive right to decide for her.

The girl’s mother also preferred to stay at the grandmother’s home because the elderly woman helped her in therapy and supported her financially. The child’s father did not accept this decision. He kidnapped the child in order to force his wife to change her mind. The man had burst into the grandmother’s apartment and brutally taken the child. The man was aggressive and used violence. When the police stopped the man, the girl finally returned to her grandmother and remained under her protection (case from the District Court for Łódź-Śródmieście, reference number: IV K 775/06).

In another case, which was also very moving, a grandmother took care of her granddaughter because the girl’s mother had abandoned her when she was little. The mother of the minor left her under the care of her own mother, which means that the victim was a minor’s grandmother and the mother of the perpetrator.

The perpetrator abandoned her daughter and moved from Poland to France. She lived in France for several years. At that time, the girl’s grandmother was appointed her legal guardian. After some time, the mother of the girl returned to Poland. She notified her mother about it. Later, the woman came to her mother’s house and wanted to see her daughter. However, the victim of parental kidnapping was reluctant to deal with any contacts between her daughter and the granddaughter, fearing negative influence on the minor. She did not know what had been happening with her daughter for many years or why she had abandoned her child.

The perpetrator did not accept that her mother had decided to hinder her ability to contact the child. Therefore, the young woman caught her daughter on her way home from school and took her from the grandmother’s care. The woman escaped and hid with the child at another family members’ house. However, the police established her whereabouts and took the child back to her grandmother. During the court proceedings, the perpetrator testified that she knew she was committing a crime and that she was acting against her mother’s will. However, she explained that she felt the need to spend time with her child (case of the District Court in Lublin-West in Lublin, reference number: XV K 159/10).

It is also worth mentioning one case, in which a sibling of a kidnapped child was a victim of parental abduction. In that case, a little boy’s sister was a victim. She became the guardian of the child after the death of their mother. When their mother died, their father began to abuse alcohol. He argued with his daughter, was aggressive and neglected his family. His daughter decided to take her younger brother from the family home. She and the boy moved to a relative, and the woman settled the boy’s legal situation, having the court appoint her the legal guardian of the boy.

The minor’s sister raised him for several years. The siblings did not have contact with their father during this time. However, after a few years, the father of the siblings started treatment from alcohol addiction. The man and his new wife, a woman that he had established a romantic relationship with during this period, decided to fight to regain the guardianship of the younger child. The man wanted to take the boy away from his older daughter and initiated court proceedings for this purpose.

The family court allowed the man to meet his son. A few months later, the father received permission to take his son to his apartment on weekends. At one occasion, the man took his son to his place of residence but did not return the child back to his daughter after the weekend. The man had broken the court order, detained the minor at his place and told the legal guardian of the boy that he would not give the child back. As a consequence, the woman reported the crime. The police took the boy from his father’s apartment and returned the child to the care of his sister (case from the District Court in Olsztyn, reference number: VII K 317/02).

The author of the article also researched cases in which the aunts of juveniles were the victims of crimes. In one such case, the victim was a little girl’s aunt and a sister of the biological mother of the child.

The girl’s mother was the perpetrator of the crime. The woman, after the birth of her daughter, was abandoned by her husband. She wanted to give her daughter for adoption, but instead she gave her child to the care of her mother and sister. Then she abandoned her child and moved to Germany. Before leaving, she assured her family that she was going to Germany to settle her financial situation. She explained that as soon as she found a job, she would come and take her daughter to Germany. Despite these assurances, the woman did not communicate with her family for a very long time.

In the meantime, the court granted care for the child to the sister of the biological mother of the abandoned girl. The woman adopted the child. She looked after the girl and raised her like her own daughter. The biological mother of the child returned to Poland after a few years, knowing that her sister would not let her meet her daughter, and that she did not forgive her for abandoning her own child. That is why the mother waited for the child at school one day and then took her and brought the girl back with herself to Germany.

The victim of parental kidnapping – the sister of the perpetrator and the legal guardian of the minor – reported the incident to the police. She reported the crime and initiated the procedure based on the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction.

However, the kidnapped child did not return to the protection of her aunt. The German court considered that the provision in which the victim was appointed the legal guardian of the child was temporary. The court decided that the girl would live in Germany under the care of her biological mother (case from the District Court in Opole, reference number: II K 297/12).

On the basis of the described cases, it is possible to state that they are different in their causes. The cases in which the guardians were foreign people, the reasons were different than in cases where the carers were family members. When the victim was a person professionally obliged to take care of the child, there was no personal animosity or anger between that person and the perpetrator. However, the situation was different when the victim was someone from the family. Emotional factors between the victim and the perpetrator were important in these cases. Among such elements, there occurred, for example, the desire to take revenge on the former partner or the desire to show the family members that the parent is more important and has more rights to decide about the child than the other relatives.

The cases described in the article clearly characterize the victims of parental child abduction. These examples show the differences between individual victims. The cases show also that parental abductions are not only the result of an argument between parents, but that they sometimes are also the result of the perpetrators’ struggles with systemic and legal circumstances that they do not understand or do not want to understand.

Final Remarks

All cases described above prove that parental abductions are undoubtedly complicated situations. The research results presented in this article provide knowledge about who in Poland becomes a victim of parental kidnapping the most often. A revealing conclusion from our study is the fact that parental abductions are not only the result of misunderstandings between spouses, either in terms of them as marital partners or parents. The presented research results unveil a new perspective of the title problem.

In the examined court cases, the victims of parental kidnapping were not only parents of the abducted minors but also people related to the child, as well as third persons who looked after the child because of professional obligations.

The analysis of the court cases revealed that in 15 cases, the victim was the head of an orphanage in which children were abducted. In the next two cases, foster parents were victims of parental kidnapping. The director of the Child Protective Services was also a victim. These data show that 30% of the examined criminal cases concerned persons who implemented the institutional custody for the child.

The victims were third persons who professionally looked after the child. In these court cases, the family courts first took the children away from their families and then placed them in orphanages, foster families or Child Protective Services. These children were taken from their family homes because their biological parents were unable to guarantee the right conditions for living and raising them (due to alcoholism, for example).

The child’s relatives were victims in 60% of the examined cases. In this group, there were 30 parents, 8 grandparents, 2 siblings and 2 aunts of kidnapped children.

The circumstances of each case were different. The persons who were victims of parental kidnapping in the analyzed cases have revised the stereotypical image of this group of people. Polish society has shaped the image of victims of parental kidnapping based on press reports or television intervention programs. However, the results of the research prove that the media image of the victim of parental abduction differs from reality. The victims of parental kidnappings are not only the mothers or fathers of kidnapped children but also their grandmothers or grandfathers, sisters or aunts.

More importantly, the results of the study also showed another aspect of parental kidnappings. Polish courts, which adjudicate in cases concerning the offence specified in Art. 211 CC, recognize that the victims of parental kidnappings are persons who have been designated to care for the child and whose will was violated. Such an interpretation extends the group of victims to persons who, on behalf of the state, professionally deal with the custody of a child. This means that parental abductions are not just a problem for parents who are in conflict. These are also problems that create obstacles in institutionalized custody. Parental abductions are a multifaceted problem that poses a threat to both the proper functioning of the family as well as the adequate care of children in orphanages or other facilities of a similar type.

Finally, there is one more issue to consider. In court cases concerning parental abductions, there is always one more person who is not treated as a victim, even though these parental abductions affect and hurt them. That person is the child itself who was kidnapped by a parent. After all, parental abductions hurt children the most. Children have the right to grow up in a safe and peaceful environment. Although parental abductions violate that right of children, it is still considered that the child’s legal guardian is the victim of the offence. This conclusion proves that there is still much to do in Poland in the area of counteracting the problem of parental kidnappings.

References:

Girdner, L. 1994. Chapter 1: Introduction. In Obstacles to the Recovery and Return of Parentally Abducted Children: Final Report, edited by L. Girdner and P. Hoff. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/e321262004-004

Missing Children Europe, Figures and trends 2016 from hotlines for missing children and cross-border family mediators, http://missingchildreneurope.eu/Portals/0/Docs/Annual%20and%20Data%20reports/Missing%20Children%20Europe%20figures%20and%20trends%202016.pdf, p. 2, [access date: 11.05.2017].

Dajnowicz-Piesiecka D., Porwania rodzielskie w ujęciu prawnym i kryminologicznym [Parental kidnapping in legal and criminological terms], Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, Poland, Torun 2017, p. 23.

Kołakowska – Przełomiec H., Przestępstwa przeciwko rodzinie i opiece w projekcie kodeksu karnego [Offences against family and custody in the draft criminal code], Przegląd Prawa Karnego [Review of Criminal Law], 1995, no. 12.

Drapała K., Buczkowski K., Porwania rodzicielskie. Analiza umorzeń i odmów wszczęcia postępowania w sprawach o przestępstwo z art. 211 k.k. [Parental abductions. Analysis of cancellations and refusals to initiate proceedings in cases concerning offenses under Art. 211 CC], Instytut Wymiaru Sprawiedliwości [Institute of Justice], Warsaw 2013.

Buczkowski K., Uprowadzenie lub zatrzymanie małoletniego wbrew woli osoby powołanej do opieki. Analiza orzeczeń sądowych w sprawach o przestępstwo z art. 211 k.k [Abduction or detention of a minor against the will of the person called to care. Analysis of court judgments in offense cases under art. 211 CC], Prawo w Działaniu [Law in Action], 2014, no. 19. https://doi.org/10.21697/pk.2017.60.2.08

Bachman R., Schutt R. K., The Practice of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice, SAGE, United States of America 2011, p. 16.

Juszczyk S., Badania ilościowe w naukach społecznych [Quantitative research in social sciences], Wydawnictwo Śląskiej Wyższej Szkoły Zarządzania im. gen. Jerzego Ziętka [Publisher Silesian School of Management of gen. Jerzy Ziętek], Katowice 2005.

Jurisdiction:

Case from the District Court in Opole, reference number: II K 297/12).

Case from the District Court for Łódź-Śródmieście, reference number: IV K 775/06).

Case of the District Court in Lublin-West in Lublin, reference number: XV K 159/10).

Case from the District Court in Olsztyn, reference number: VII K 317/02).

Case from the District Court in Białystok, reference number: III K 1754/06).

Case from the District Court in Kielce, reference number: IX K 1016/10).

Tėvų įvykdytų vaikų grobimų aukos Lenkijos baudžiamojo įstatymo šviesoje (remiantis jurisprudencijos analize)

Diana Dajnowicz-Piesiecka, PhD

Santrauka

Šis straipsnis yra apie tėvų įvykdytų vaikų grobimų aukas Lenkijoje. Jo tikslas – parodyti vaikų grobimo aukas Lenkijos jurisprudencijos šviesoje. Studija yra empirinio pobūdžio, joje pristatomi jurisprudencijos analizės rezultatai. Studijoje buvo analizuojamos 59 baudžiamosios bylos, iškeltos dėl vaikų grobimų, kuriuos įvykdė tėvai. Tyrimas parodė, kad Lenkijos įstatymas asmenį, iš kurio buvo pagrobtas vaikas, laiko tokio grobimo auka. Tačiau įdomu tai, kad pats vaikas auka nelaikomas. Remiantis tyrimu, prieita prie išvados, kad tėvai vaikus grobia ne tik vieni iš kitų dėl kilusių tarpusavio nesutarimų, bet vaikai gali būti pagrobti ir iš kitų žmonių, pavyzdžiui, vaikų namų direktorių arba senelių, kurie globoja vaiką. Šiame straipsnyje teigiama, kad vaikų grobimai (įvykdyti pačių tėvų) yra ne tik šeimų, bet ir institucijų, įtrauktų į vaiko globą, problema.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: tėvų įvykdyti vaikų grobimai, auka, vaikas, nusikaltimai šeimai ir globai, jurisprudencijos analizė.