Kriminologijos studijos ISSN 2351-6097 eISSN 2538-8754

2021, vol. 9, pp. 100–128 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/CrimLithuan.2021.9.4

Homicide Trends and Types in 1920s-1930s Lithuania: Limitations of Official Statistics

Sigita Černevičiūtė

Vilniaus universitetas, Filosofijos fakultetas

Sociologijos ir socialinio darbo institutas

Kriminologijos katedra

Vilnius University, Faculty of Philosophy

Institute of Sociology and Social Work

Department of Criminology

Universiteto g. 9, LT-01513 Vilnius

tel. (8 5) 266 7600

sigita.cerneviciute@fsf.vu.lt

ORCID iD https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4409-4961

Abstract. This article calls into question the reliability of the official historical statistical sources of homicides in 1920s-1930s Lithuania and aims to evaluate the limitations of the mentioned sources. With this in mind, we will attempt to make some assumptions about homicide types and trends in interwar Lithuania. The Central Statistical Bureau had been publishing statistical data relevant to the investigation of homicides in Statistical Bulletins and the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania since 1924. These statistical sources in the homicide study were problematic due to an unclear data collection methodology, the use of different homicide terms, unrealistic definitions of urban and rural areas and changes in Lithuania’s territory and population. We cannot determine the exact rates of the 1930s homicides due to the change in the homicide terminology and its content. Between 1924-1931 the term violent deaths, except suicides, was used, and homicides were not singled out. The analysis also shows that until 1931 violent deaths included homicides and accidental deaths too. From 1932 to 1939 violent deaths were divided into 4 groups: suicide, homicide, accidents and other violence. The more detailed data of the 1930s have revealed that the most frequent victims of homicide were in the 15-29 and 29-44 age groups for men, while the 15-29 age group stands out for females. The most common method of killing was shooting. The police-published homicide statistics also reveal a problem of terminology. According to the Penal Statute of Lithuania, deprivation of life was distinguished into the crimes of homicide; infanticide; abortion; preparation to murder; attempted murder and persuasion and help to commit suicide. However, this terminology was only partially reflected in the police statistics, as between 1927-1930 the police used the term homicides and classified them into the ones committed: for-profit; during brawls; for other purposes. Infanticide was separated from homicides. Leaving out others, infanticide was the most common murder type in interwar Lithuania. Since 1931 the statistics of the police had been using the term of deprivation of life and distinguished it into the 7 types according to the motive: for-profit; during brawls; defending one’s own life or the lives of others; involuntary; infanticide; abortion and for other purposes. It did not include dead bodies found, suicides and accidental deaths. After analysing the 1931-1938 data on deprivation of life, excluding abortions, homicides would vary from 200 to 300 per year. When comparing all the deprivations of life with homicides by the cause of death, it can be concluded that these figures included preparation for murder and attempted murder as well as persuasion and help to commit suicide. Thus, due to the change in the terminology and the inclusion of attempted murders, the police statistics can be considered unreliable. Homicides are the most precisely quantitatively defined by the rates of causes of death, which in 1932-1938 Lithuania were relatively stable with an amplitude of 93-139 murders per year. On a basis of the analysis of the police statistical data, it is possible to identify at least 4 main types of homicides in interwar Lithuania: reproductive – infanticide and abortions, aggressive – killings during brawls, economic - for profit as well as unintentional homicides that happened during accidents.

Keywords: historical statistics, homicides, homicide types, violent deaths, interwar Lithuania.

Nužudymų tendencijos ir tipai XX a. 3–4 dešimtmečio Lietuvoje: oficialios statistikos trūkumai

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje kritiškai analizuojama oficialių statistinių XX a. 3–4 dešimtmečio nužudymų šaltinių patikimumas ir siekiama įvertinti jų trūkumus. Atsižvelgiant į gautus rezultatus, bus mėginama padaryti galimas prielaidas apie nužudymų tipus ir tendencijas tarpukario Lietuvoje. Straipsnyje susitelkiama į medicinos įstaigų duomenų su mirties priežastimis ir policijos skelbtų nužudymų statistikos analizę, atsiribojant nuo teismų pateikiamos nužudymų bylų kiekybinės informacijos. Nužudymų statistiniai duomenys nuo 1924 m. buvo skelbiami Statistikos biuleteniuose ir Lietuvos statistikos metraščiuose. Šie statistikos šaltiniai nužudymų tyrime kelia klausimų dėl savo patikimumo, dėl neaprašytos duomenų rinkimo metodologijos, skirtingos nužudymų terminijos vartojimo, dirbtinio miesto ir kaimo vietovių apibrėžimo, Lietuvos teritorijos ir gyventojų skaičiaus kitimo. XX a. 3 deš. nužudymų skaičiaus negalime nustatyti dėl nužudymų terminijos kaitos ir jos turinio. 1924–1931 m. vartotas terminas prievartos mirtys, išskyrus savižudybes, o nužudymai nebuvo išskirti atskirai. 1932–1939 m. prievartos nusikaltimai skirstyti į keturias grupes: nusižudymus, nužudymus, nelaimingus atsitikimus ir kitokią prievartą. XX a. 4 deš. išsamesni duomenys atskleidė, kad vyrai buvo nužudomi 3–4 kartus dažniau nei moterys ir priklausė 15–29 ir 29–44 metų amžiaus grupėms, o moterys – 15–29 metų amžiaus grupei. Labiausiai paplitęs nužudymo būdas – nušovimas. Policijos publikuotuose nužudymų statistiniuose duomenyse taip pat išryškėja sąvokų problema. Remiantis Lietuvos baudžiamuoju statutu, kaip gyvybės atėmimas buvo apibrėžti nužudymai, pavainikių kūdikių nužudymai, abortai, rengimasis ir pasikėsinimas nužudyti, suteikimas priemonių ir kalbinimas nusižudyti. Tačiau policijos statistikoje ši terminija atsispindėjo tik iš dalies, 1927–1930 m. policija vartojo žmogžudysčių terminą ir jas skirstė į padarytas: pasipelnymo tikslu, per muštynes ir kitokias. Nesantuokinių vaikų žudymas buvo išskirtas atskirai. Jei neskaičiuotume kitokių nužudymų, infanticidas buvo dažniausias nužudymo tipas tarpukario Lietuvoje. Nuo 1931 m. policijos duomenyse gyvybės atėmimas buvo skirstytas į septynis tipus pagal įvykio motyvą: pasipelnymo tikslu, per muštynes, ginant savo ar kitų gyvybę, per neatsargumą, pavainikių kūdikių žudymas, gemalo sunaikinimas ir kitais tikslais. Nusižudymai, nelaimingi atsitikimai ir rasti mirusiųjų kūnai į šias kategorijas neįėjo. Išanalizavus 1931–1938 m. gyvybės atėmimo duomenis, neskaičiuojant abortų, nužudymai varijavo tarp 200–300 atvejų per metus, tačiau palyginus visus gyvybės atėmimus su nužudymais pagal mirties priežastį darytina išvada, kad šie skaičiai pateikti su rengimusi ir pasikėsinimu nužudyti bei suteikimu priemonių ir kalbinimu nusižudyti. Taigi, dėl sąvokų kaitos ir pasikėsinimų priskaičiavimo prie nužudymų policijos statistinius duomenis galima laikyti nepatikimais. Tiksliausiai kiekybiškai nužudymus apibrėžia mirties priežasčių rodikliai, kurie 1932–1938 m. Lietuvoje fiksavo gana stabilią 93–139 nužudymų per metus amplitudę. Remiantis policijos statistinių duomenų analize galima identifikuoti bent keturis pagrindinius nužudymų tipus tarpukario Lietuvoje: reprodukcinį – nesantuokinių kūdikių žudymą ir abortus, agresyvųjį – nužudymai muštynių metu, ekonominį – siekiant pasipelnyti, netyčinius nužudymus per nelaimingus atsitikimus.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: istorinė statistika, nužudymai, nužudymų tipai, prievartos mirtys, tarpukario Lietuva.

Introduction

Historical violence is one of the most favourite topics of nowadays crime historians, where homicide rates are generally considered as an indication of the level of serious violence (Spierenburg, 2001). However, when studying historical violence, researchers tend to rely on official statistics collected by state institutions; of course, it helps to provide a broader view of the phenomenon and helps with comparisons for different periods or levels of violence. Comparisons of crime levels and trends between different countries have been an object of statistical research since the 1820s.

It is reported in the literature that homicides are the most accurately recorded violent crimes, explaining the considerable body of literature on historical long–term trends of homicides that has researched murder since the Middle Ages to nowadays in the United States of America (Lane, 1979, Monkkonen, 2006) and western European countries (Aebi & Linde, 2016; Eisner, 2003; Spierenburg, 2008, 2012). Historical homicides are researched extensively in the Nordic countries (Ylikangas, Karonen, Lehti, 2001; von Hofer, 1990, Vuorela, 2018). Here, a new quantitative research tool of historical homicide monitor1 has been developed and used to transform qualitative data to quantitative, enabling comparisons cross-nationally and over time. The result of this tremendous work is a comparison of homicides in Denmark, Sweden and Finland from the early modern times to the present (Kivivuori, et al., 2022).

However, only some of the research has used and critically evaluated official historical statistical data on violent crimes (Gurr, 1981; Monkkonen, 2001), others have used their own created database or focused on the interwar period (Lehti, 2001b). The research on historical statistics of homicide in Eastern Europe remains limited; in particular, from the Baltic countries, only the interwar Estonian homicide trends have been analysed in comparison to Finland, concluding that the rise of criminal violence in 1930s Estonia was related to the modernisation of agriculture and pressures of uncertain future on youth, competitive values and normalised violence inherited from Czarist Russia (Lehti, 2001a).

In the Lithuanian historiography, research of long-term historical homicide trends is still waiting for its turn, and only a few historical criminology studies have shown interest in the interwar period crime trends in Lithuania. The historical statistics of homicides registered by the police in 1931-1939 without critical assessment have been presented in an overview of the development of crime in Lithuania between 1918-1993 (Smaliukas & Urbelienė, 1994). Babachinaitė and Paulikas (2002) have analysed the police-registered crime statistics without critically examining them. Even after noticing that only between 1937-1938 attempted murders were included in the deprivations of life statistical data, the researchers have concluded that the rates of criminal deprivation of life were not low in interwar Lithuania. In the history of the interwar criminalistics, the motives of murders have first been presented in the Lithuanian historiography by Palskys (1995), the content of homicides punished by the death penalty has been investigated by Černevičiūtė and Kaubrys (2014), and the statistics of femicide have been briefly analysed by Černevičiūtė and Kareniauskaitė (2021). A key problem with much of the literature regarding statistical research of the interwar Lithuania’s homicides is that it makes only superficial overviews of the homicide trends without critically evaluating the methodology of data collection and misuses the statistics to make conclusions without credibility.

Under the pseudonym Alfa, an author of an article on the crime statistics in 1930s Lithuania wrote: “Statistics are facts replaced by numbers; those numbers show us what path we have been on, where that path is leading us and, if necessary, how to better replace that path with another – new – path.”2 However, statistics should not be accepted without any doubts. Historical homicide research confronts many methodological challenges, which scholars do not always address. This article, for the first time in the Lithuanian historiography, calls into question the reliability of the official historical statistical sources of homicides in 1920s-1930s Lithuania and aims to evaluate the limitations of the mentioned sources. With this in mind, we will attempt to make some assumptions about homicide types and trends in interwar Lithuania.

When carrying out statistical research on the homicide phenomenon, there is no universal method for how to count murders. However, it could be studied from three different perspectives – a victim’s, a crime’s and from the perspective of a perpetrator’s punishment.

The first one could be called counting the bodies – calculating murder victims and checking body inspection reports. According to the crime historian Pieter Spierenburg (2001), homicide rates should always be calculated according to the reports about bodies found. Medical statistics about the causes of death are available in most European countries from the end of the nineteenth century or the beginning of the twentieth, and it is difficult to hide a body.

The second stage after the body is found is defining it as a crime and investigating the circumstances to find the perpetrator. For our research it means studying the police-recorded homicides. And the third one, we can research homicides via court statistical data and calculate convicted or acquitted criminals. All of these three angles have their own advantages and disadvantages. They can provide a different overview of the trends and types of homicides in Lithuania in the 1920s and 1930s. In this article, we will analyse the medical and police statistical records as one of the most reliable sources about the homicides’ phenomenon.

The mentioned methodological problems have inspired the author of this article to start rather scrupulous work of critically analysing and comparing the data of homicides in the Official Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania, official police periodicals, archival statistics and official governmental law editions related to the organisation of collection of statistics. It should be mentioned that at the beginning of the research on homicide statistics in interwar Lithuania, the primary sources were the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania (Lit. Lietuvos Statistikos Metraščiai, Vol. 1-12)3, Bulletin of Statistics (Lit. Statistikos Biuletenis, 1923-1940)4, while the journals Police (Lit. Policija, 1924-1940)5 and Reference Book of Criminalistics (Lit. Kriminalistikos Žinynas, 1935-1940)6 had only been scanned and published on the internet in Portable Document Format or as images without a possibility to copy the data en masse. Because of that, all the sources had to be reviewed thoroughly and numbers had to be collected manually and recalculated by the author of this article7.

We have not used the data published by the authors of the first historical statistics project in Lithuania8 in the present article, but it is important to acknowledge that at least 200 new datasets of the historical statistics about the Baltic States have been published, including the dataset Causes of Death of the Population in Lithuania, 1919-19399, where violent deaths have been mentioned. The compilers of the table have grouped the data of 1925-1939 according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10 chapter, version 2019). However, the researchers should have kept the methodological limitations of the causes of death statistics in interwar Lithuania in mind and separate the violent deaths until 1932 from the homicides since then (more about it in this article p. 112).

Institutionalisation of Interwar Lithuanian Statistics

Lithuania declared its Independence from the Russian Empire on February 16th, 1918. During the establishment of the First Republic of Lithuania, following an example of Tsarist Russia, the collection of statistics was decentralised, and each ministry had its own, usually weak statistical units (Martišius. 2009). However, as early as 1919, the General Statistics Department was established on 6 September by the order No 370 of the Minister of Trade and Industry Jonas Šimkus. Soon it was reorganised into a new statistics department with 6 staff members at the Credit Office10. Thus, the collection of statistical data started with only a few individuals. In addition to this, all ministries maintained their own statistical divisions. Because of that, it was decided to centralise the process.

The government’s resolutions establishing the Central Statistical Bureau and the Standing Statistics Committee entered into force on May 20th, 1921. The committee became Lithuania’s chief statistical body, and the Central Statistical Bureau was its executive body, functioning as a separate department under the Ministry of Finance. The objectives of the Central Statistical Bureau were:

“a) to draw up plans for the work in the field of statistics and to submit them to the Standing Statistics Commission for review and final editing;

b) to follow the work and research on statistics in foreign literature and to apply the most suitable methods of statistics to the State of Lithuania;

c) to collect, verify and manage statistical material, publish individual press releases and publish periodic statistical collections;

d) to inform the State institutions about the statistical data;

e) to perform other tasks at the request of the Minister”11.

One of the first tasks of the Central Statistical Bureau was to organise the General Population Census of Lithuania, which was conducted in 1923. The first results were published in the monthly Bulletin of Statistics12 and later in a separate book about the data on the Census13. In Lithuania at that time (53,242 km²), excluding the Klaipėda Region, 2,028,971 inhabitants were registered, 47.7 % of which were men and 52.3 % were women. When the Klaipėda Region was incorporated into Lithuania in 1923, it was also included in the activities of the Central Statistical Bureau since 1925.

The work of the statistical bureau improved over the years, and its participation in the international statistical organisations began. Lithuania joined the International Trade Statistics Bureau in Brussels in 1928. Although it should be borne in mind that Lithuania did not join many such international organisations simply because of finances – Lithuania was not a wealthy country and could not afford to pay a membership fee. Lithuania wanted to sign the International Convention on Statistics in 1929, but this decision was postponed for unknown reasons. It can be assumed that it was not signed because of a requirement to meet international standards that Lithuania was not eager to follow.

At the beginning of the 1920s, the Central Statistical Bureau had 16 people on staff and just 3 departments, but at the end of the decade it already had 6 departments: the office and the departments of demography, agriculture, industry and labour, foreign trade, and economic market14. As a result, the staff increased twice – to 34 people, which allowed the bureau to improve the quality of Lithuanian statistics.

The end of the development of the statistical data collection system can be considered in 1930 when the Law on State Statistics was adopted. It aimed to solve the problems that had arisen so far: to clarify the centralisation of the collection of statistics and define the right to request statistics from institutions and individuals. Since 1930 the Central Bureau of Statistics was appointed as the highest executive body of statistics; the Statistical Committee replaced the Standing Statistical Committee under the Central Statistical Bureau. The law provided that the Central Statistical Bureau:

“1) collects, verifies and processes statistical data required by law or the government;

2) conducts general population, agricultural and other censuses required by law;

3) publishes state statistical data and issues periodical statistical bulletins and yearbooks and other statistical publications;

4) unifies the statistical data on the work of public law institutions of the entire state;

5) co-operates with international and foreign statistical institutions.”15

The law also stipulated that all institutions and persons had to provide statistical data to the statistical bureau upon request. Persons who refused to provide such information or submitted false information without a legitimate reason had to be fined 250 litas. However, the new law on statistics was not perfect. The relations of the statistical bureau with other state institutions were not specified. It was not explained who could impose the fine for false information – administrative bodies or a court (Martišius, 2009).

The bureau of statistics itself, until 1940, was poorly funded and, therefore, poorly equipped. At that time, the calculations in Lithuania were performed using electric and manual arithmometers and perforating machines (Martišius, 2009). Although the statistical collection system had been improved at the beginning of the 1930s and a breakthrough in the official statistics had taken place, the detailed and sufficiently precise statistics began to be published only in 1935. However, there were many problems in conducting a quantitative study of homicides, even with the 1930s data.

Collection of Homicide Statistics of Lithuania in 1920s-1930s

According to the sociologist Zenonas Norkus, the beginning of statehood of the First Republic of Lithuania was “statistical darkness.” Most of the statistical data about the period of 1918-1920 when Lithuania was battling against the Bolshevik forces, Bermontians and Poland have been collected retrospectively (Norkus, 2014). The Central Statistical Bureau started to continuously publish official statistics with the causes of death based on some kind of methodology only starting from 192416 up to 1939 in the Bulletin of Statistics and the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania. The police-recorded homicides were started to be published in the Statistical Yearbooks only since 1931 (with the data from 1929-1930). These two primary sources for the statistical research of homicides have a few different problems.

First of all, the methodology of how the data had been collected was explained only vaguely in the Bulletin of Statistics, where the violent deaths of 1924 were mentioned for the first time. The methodologies used in the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania were not explained at all.

Secondly, various terms to describe the homicide phenomenon without exact definitions were used in different parts of the yearbook and for different years: violent death, homicide, and deprivation of life. As a result of the changing and vague methodologies, it is not clear what was included into the records and what was not. It should be mentioned that in the historical research of homicides, infanticide and abortions are usually not included because of their fundamental difference from other types of homicides (Lehti, 2001a). In this article, we attempt to understand the definition of homicide in the interwar Lithuanian statistics and include the mentioned types in the research. The archival sources of the Central Statistical Bureau (which led the publishing of the yearbooks) do not help as well – only a few documents with original statistical data of homicides by the cause of death from the years 1933-1934, 194017-1941 have survived until nowadays, but there is nothing to explain its methodologies18. Consequently, only comparisons and a careful analysis of the periodicals that published only partial statistics could help.

Thirdly, there were no realistic concepts of urban and rural areas. According to the Bulletin of Statistics of 1924, cities and towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants were considered urban areas, and this decision was based on international practice19. However, in the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania, the statistics of homicides by the causes of death were only divided into urban and rural areas since 193220.

It should be noted that the statistical data were also affected by Lithuanian territorial changes. Lithuania lost Vilnius in 1920 and regained it at the end of 1939, annexed the Klaipėda Region in 1923 and lost it in 1939 (Laurinavičius, 2009). Because of these territorial changes, we have the statistics in different years and different data sets; for example, homicide statistics by the cause of death were published with the Klaipėda Region for 1925, but without it between 1926-1927, and then again with the Klaipėda Region between 1928-1938, and without it in 1939. As a result, it is rather hard to have a complete set of homicide rates for the entire interwar period of Lithuania.

Changes in population growth also impact the rates of crime statistics. As mentioned, the general census of the Lithuanian population was conducted in 1923, recording 2 million people in the territory without the Klaipėda Region. In the Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania, the changes in the population were calculated on the basis of natural increase only, and migration was not taken into account, although many people were going abroad every year (Gaučas, 1978). A new census was planned to be completed in the 1930s. However, because of the global Great Depression of 1929-1933, the money was used for essentials with the thought that it would be possible to return to it later, but in 1940 the occupation of Lithuania by the Soviet Union changed these plans. Because of all these problems in this article, we have decided not to count homicide rates per 100,000 population and use only “bald” homicide numbers at the time.

Counting the Bodies: Trends of Violent Deaths in Lithuania between 1924-1939

As mentioned before, the official statistics of Lithuania were compiled by the Central Statistical Bureau. Medical records on homicides were collected and processed in the Department of Demography, which collected the statistics on the natural movement of the population – the information about the married, born and the deceased. Separate forms were to be sent to the Central Statistical Bureau by the registration points of the respective religions. For example, in 1930, there were 669 points in the main Lithuania (without the Klaipėda Region), 500 of whom were Catholic, 42 for Israelites, 53 for Old Believers, 27 for Orthodox, 26 for Evangelical Lutherans; 7 for Evangelical Reformed, 5 for Methodists, 4 for Baptists; 3 for Mahomethones, one for Adventists and one for Karaits21. The statistical bureau received about 2,500 to 3,000 death certificates per month, divided into counties, towns and villages by gender, major age groups, causes of death and religions22.

Although official Lithuanian statistics were published with French terms, international classifications were not followed, for example, in 1920, an international list of causes of death, entitled Chapter XIV, External causes, was divided into extremely specific categories, ranging from suicide, accidental deaths like drowning, accidental falling, right through to homicide by firearms, homicide with cutting or stabbing instruments, homicide by other means as well as infanticide. Also, violent deaths of unknown causation23 were also mentioned.

In Lithuania, this procedure was not followed. As mentioned before, there have been problems detected with the terminology of homicides in the official statistics. The first official statistical data with homicides as violent deaths in 1924 were published in the monthly Bulletin of Statistics in 1925, in a table of the deceased in 1924 sorted by months and causes of death. As the source states, only the minority of the deaths were stated by medical doctors; the majority were based on the testimonies of relatives. It was also explained that all the death certificates that did not clearly state the cause of death or were unreadable were considered to be other illnesses or unknown causes, which could have meant that some of the homicide cases were included in these numbers as well24. The same decision was made in the third chapter of the Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania, Natural Movement of the Population in Lithuania, were the deceased by cause of death were also recorded.

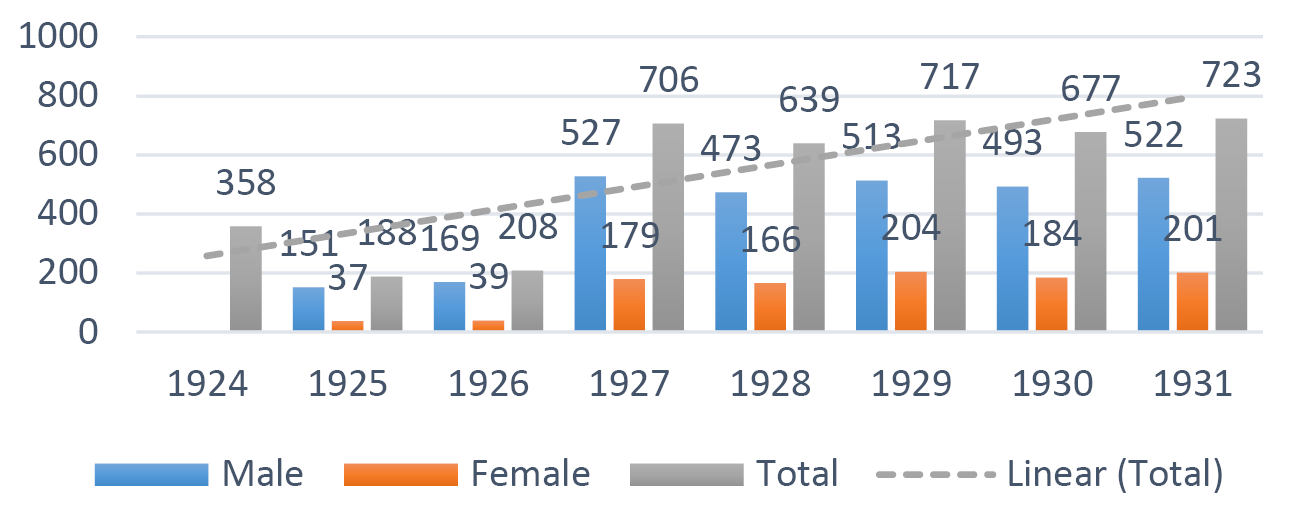

The term violent death was used in Lithuania between 1924-1931 in the Bulletin of Statistics and the Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania to describe homicides as violent deaths, except suicides with the French equivalent Morts violentes (suicide excepté), amounting to 723 violent deaths in 1931(Figure 1a). Suicides, other illnesses and the unknown or unexplored causes were mentioned separately. In these sources, homicides were not distinguished into a separate group. This complicates the study of the homicide statistics in interwar Lithuania and the comparison of the data with foreign countries.

Since 1932 violence was distinguished into 4 main groups of suicide, homicide, accidents and other violence25. Seeing homicides singled out from accidents in 1932, it can be assumed that until then violent deaths had included both homicides and accidental deaths. It should be mentioned that the term accidental death could be understood as involuntary manslaughter in the interwar Lithuanian context. As a result, in the first period of 1924-1931, before homicide was separated from other violent deaths, we cannot determine the exact rate of homicide victims (Figure 1a and 1b).

Figure 1a. Violent deaths (without suicides) in Lithuania between 1924-1931

Source: Statistical Bulletin No 5; Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania, Vol. 1-4.

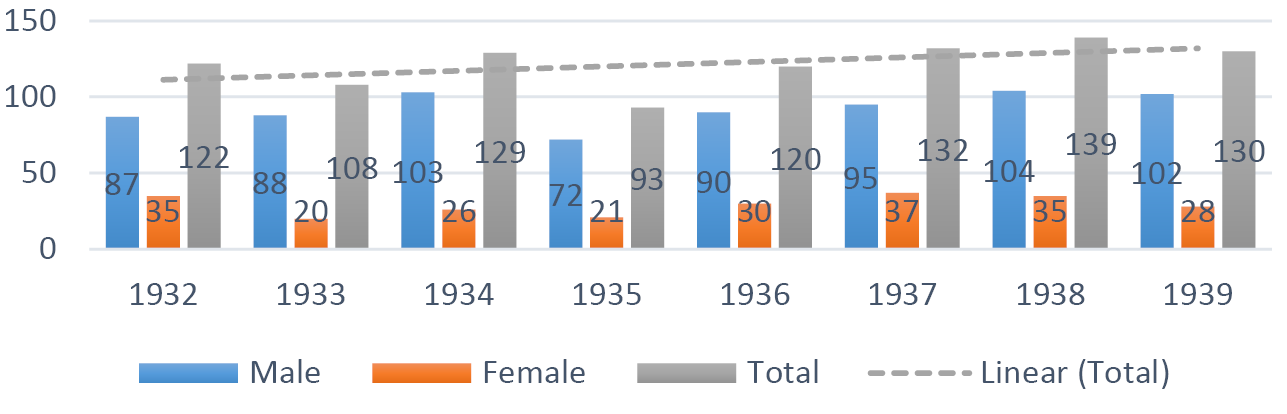

Figure 1b. Homicides in Lithuania between 1932-1939 (with the Klaipėda Region, except 1939)

Source: Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania, Vol. 5-12.

The period of 1932-1939 clearly shows that men were killed 3-4 times more often than women. When comparing the murder victims by gender and age, the most frequent victims of homicide were in the 15-29 and 29-44 age groups for men, while the 15-29 age group stands out for females (Table 1). The Finnish criminologist Veli Verkko has researched homicides in 1920s-1950s Finland and has been one of the first to discuss the need to analyse homicides by gender. In the so called Verkko’s laws, it was stated: “in countries with high homicide rates, the percentage of female offenders and victims is small, and vice versa, in countries with low overall homicide rates, the percentage of female offenders and victims is high.” (Kivivuori, 2017, p. 148). The high interwar Lithuanian rates of homicides are an echo of the Verkko’s laws with a small percentage of female homicide victims and perpetrators. The murders of men can be explained by comparing the statistics with the police data, which shows a high number of deaths in brawls (Figure 3). The female murder victims’ age group could be explained by the fact that at the peak of their reproductive age many women became victims of domestic violence (Černevičiūtė & Kareniauskaitė, 2021).

Table 1. Homicides by the cause of death in Lithuania between 1932-1939 (with the Klaipėda Region, except 1939) by age group and gender

|

Age group |

1932 |

1933 |

1934 |

1935 |

1936 |

1937 |

1938 |

1939 |

||||||||

|

M* |

F** |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

|

|

0 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

1-4 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

5-14 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

2 |

7 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

|

15-29 |

29 |

12 |

36 |

13 |

28 |

13 |

30 |

7 |

34 |

11 |

39 |

10 |

39 |

15 |

35 |

16 |

|

30-44 |

26 |

5 |

22 |

2 |

32 |

1 |

30 |

4 |

34 |

2 |

27 |

12 |

34 |

9 |

40 |

5 |

|

45-59 |

10 |

8 |

13 |

3 |

14 |

3 |

6 |

1 |

13 |

4 |

12 |

7 |

10 |

3 |

13 |

3 |

|

60-69 |

10 |

2 |

7 |

2 |

13 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

|

70-79 |

3 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

7 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

7 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

7 |

1 |

|

80 and more |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Unknown |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

Total: |

87 |

35 |

88 |

20 |

103 |

26 |

72 |

21 |

90 |

30 |

95 |

37 |

100 |

34 |

102 |

28 |

Source: Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania, Vol. 5-12.

M* – Male, F** – Female.

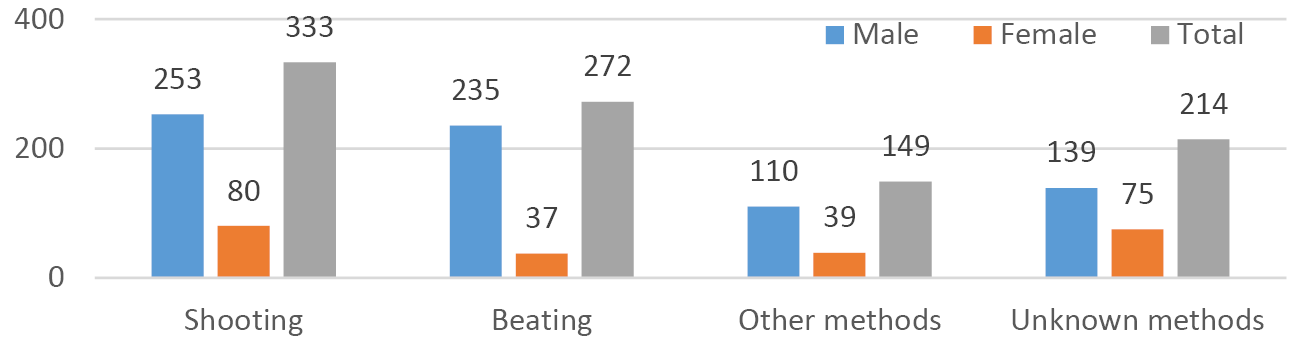

Since 1932 homicides were divided on a basis of the method used to commit it: shooting, beating, murder by other means and unknown methods.

Shooting was the most popular method of murder in 1930s Lithuania, and only the second one was beating (Figure 2). It can thus be reasonably assumed that the fact that shooting dominated reflected one of the technical factors of the homicides in interwar Lithuania since the First World War and the Lithuanian Wars of Independence, as guns may have been widely accessible in the Lithuanian society. It is worthwhile noting that homicide here was probably understood only as an intentional murder except for infanticide and abortion. As mentioned earlier, infanticide in interwar Lithuania was one of the most common murder types, so strangulation and suffocation would probably be added to the picture.

Figure 2. Homicide victims by the method used to commit the homicide in Lithuania in 1932-1939 (with the Klaipėda Region, except 1938-1939)

Source: Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania, Vol. 5-12.

Police Records of Deprivation of Life: Types and Content of Homicides in 1930s Lithuania

First, the crime-related statistics, including homicides, were published from the year of 1920. Based on the police records, 12,605 criminals were arrested that year, primarily murderers, robbers, thieves, deserters, illegal vodka producers and anti-state criminals. 258 of the cases were recorded as armed attacks, 77 % of these were carried out with the purpose of robbery and the rest – with a revenge motive. 183 men and 42 women were killed in these crimes among the total of 225 murder victims. There were 182 murderers arrested, and 5 of them were killed during the arrest26. The source states that the data for 1920 were not complete and were sorted out only at the end of the year, and uncritically presumes that it could be higher by 50 %27. To sum up, the mentioned criminal statistics are very problematic and need a careful evaluation: there are no other sources to compare and verify the data. It is also sporadic, therefore, what is left is only a partial view of the homicides’ phenomenon of that period.

The interwar Lithuanian police was subordinated to the Department of Civil Protection (the Police Department since 1934) and worked under the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The statistics used to be sent to the Department of Civil Protection28 every month. Even though there were some published crime statistics of the year 1920, complete and continuous official data sets were published of the years 1927-1930 in the journal Police, but the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania began to publish the statistical data collected by the police only from 1929. It should be mentioned that there were some discrepancies29 between the data published in the journal Police and in the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania, probably because of the rates stemming from the Klaipėda Region. Taking this into account, we have decided to analyse both sources separately.

Police, as a law enforcement agent, used crime classifications according to the Penal Statute of Lithuania. It should be explained that in 1918 the Lithuanian government decided to adopt the 1903 Criminal Code of the Russian Empire in as much as it did not contradict the temporary Constitution enacted on the 2nd of November, 1918 (Maksimaitis, 2001). The imperial Russian Criminal Code of 1903 came into force in Lithuania in 191930. Homicides were included in the XXII chapter of Deprivation of Life (Rus. O лишеніи жизни) and distinguished crimes into homicide; infanticide; abortion; preparation to murder; attempted murder; persuasion and help to commit suicide (defined in the articles 453-466). Homicide was defined in the article 453: “Whoever committed a crime by killing someone shall be punished by imprisonment with hard labour for no less than eight years.”31 It should be mentioned that although a definition of voluntary manslaughter was neither used in interwar Lithuania nor separated from other homicides in the statistics, the crime was defined in the article 458, describing it as a murder committed in a state of serious tension.

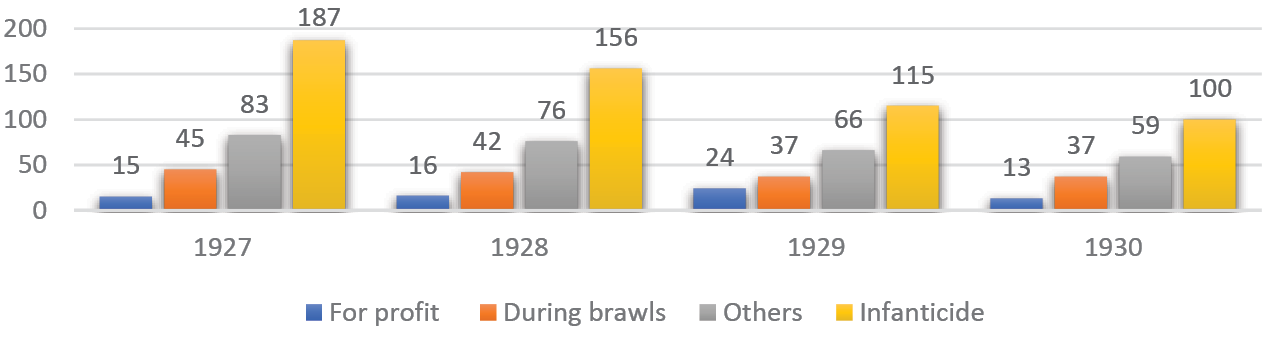

The legal term of deprivation of life and the types of homicides did not properly unify the data of the police records. In different sources and years, there were different terms used as well. Research shows that until the beginning of 1927 the police used to gather statistical data about the crimes from the police districts every month. However, it did not show a complete picture of the criminogenic situation in the country. The police was already struggling with mistakes in the data when same crimes were counted as different types of offences. For example, in older statistical data suicides were counted as homicides as well as accidental deaths32. However, starting with 1927 new rules for statistical data of crimes were applied, the term homicide was used and distinguished into three types of homicides committed: for-profit; during brawls; for other purposes. Infanticide was separated from homicides33. It should be noted that in the police sources, the exact term of infanticide was used as a murder of a bastard infant, already exposing a moral concept of the murder of the children born out of wedlock.

The statistics of the crimes between 1927-1930 were already criticised by the well-known economist at the time Albinas Rimka. He noticed that homicides defined as others are committed more often than for-profit and during brawls. He suggested that homicides should be distinguished into 5 groups: (1) deliberate murder for profit; (2) deliberate murder out of personal revenge or jealousy without a motive for profit; (3) unintentional murders during brawls; (4) random homicides when a victim and a perpetrator are the victims of an accident (for example: getting shot when playing with a gun or a driver kills someone in a street); (5) other homicides (low numbers for sadistic murders, etc.). In his opinion, the sum of all homicides was useful, along with infanticide rates34.

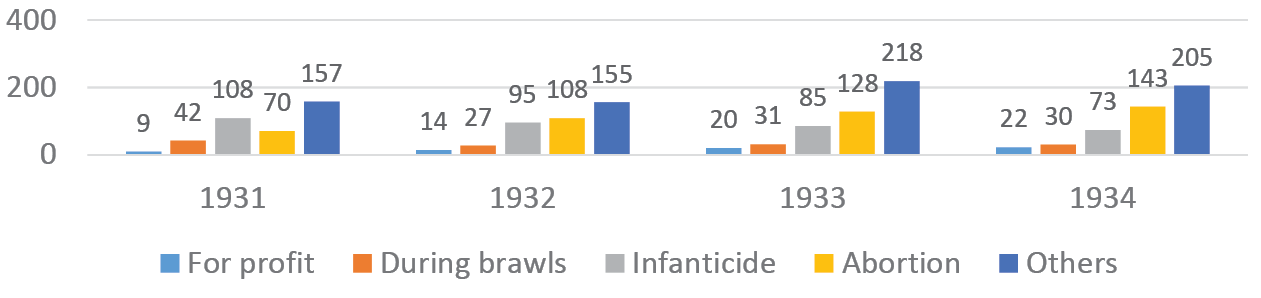

From this standpoint, while leaving out others, which probably included a variety of murders, including those committed for political reasons, infanticide was the most common murder type in interwar Lithuania. The majority of them were committed by single mothers, poor and unable to support a child financially and afraid of the consequences of having a bastard child in a conservative, religious society of interwar Lithuania. The second most common homicide used to happen in brawls, where the perpetrator and the victim were usually both males. In this type of murder, the social problem of alcohol was evident. Alcohol abuse was one of the main technical factors of homicide, potentially provoking and accelerating the numbers of violence in drunken conflicts at home, parties, weddings, etc. (Figure 3). A low number of murders for-profit may be explained by the fact that this type of homicide was punishable by death (Černevičiūtė & Kaubrys, 2014). The police rates provided evidence of the rise of homicides in 1931 (Figures 3, 5), when the world economic crisis of 1929 started to impact the Lithuanian economy35. Nevertheless, we should keep in mind that the police rates of homicides also included records of attempted murder.

Figure 3. Police-registered homicides by type between 1927-1930

Source: Police, 1937, No 2.

The problems of the statistics mentioned by Rimka were later addressed by the chief of criminal police Kazys Budrevičius. He explained that even though the procedure of collecting the statistics was not perfect, it was better than it had been until 1927 when it had been realised that the registration of different crimes, including homicides, was really problematic: “Some police agencies, reporting murders, classified suicides as homicides and burglaries as robberies etc. That is to say, many police officers have a poor ability to classify crimes.”36 As a result, a table for the statistical data of crimes was created as simple as possible. However, Budrevičius expected that the collection of the crime statistics would be taken over by the statistics professionals in the Central Statistical Bureau.

Public criticism may explain why new instructions for the statistical data collection were created just after a few years and came into force on January 1st, 1931. The statistics of the police already used the term of deprivation of life and distinguished it into 7 types: for-profit; during brawls; defending one’s own life or the lives of others; involuntary; infanticide; abortion and for other purposes37. It was clarified that these classifications had been made according to the causes of deprivation of life, and it did not include dead bodies found, suicides and accidental deaths38. Note that abortions at the time were considered deprivation of life.

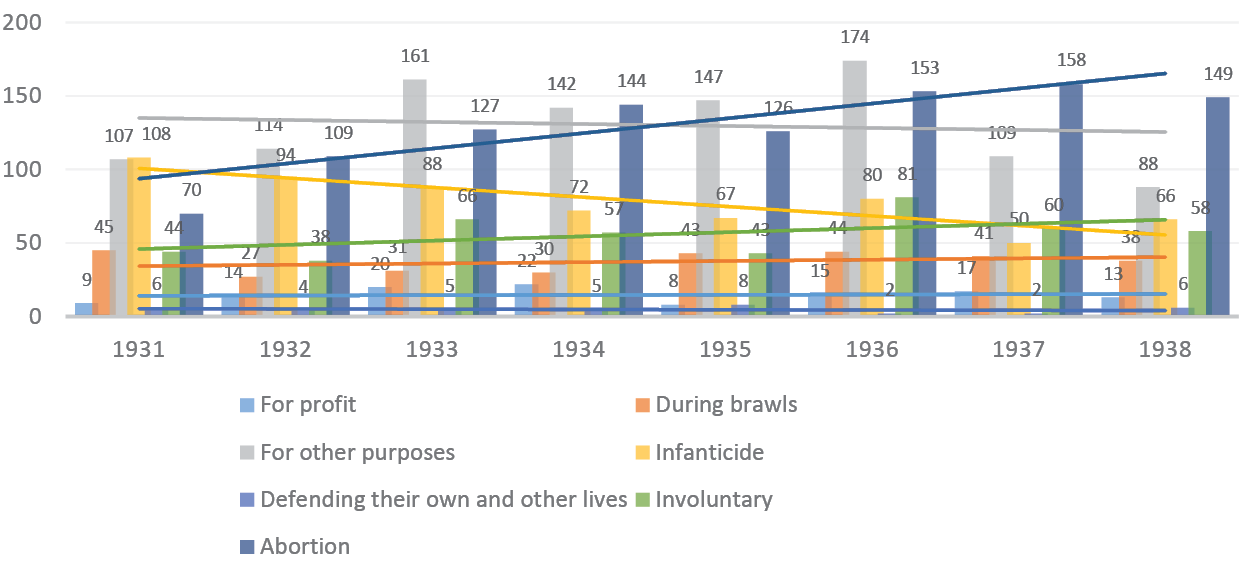

It may be assumed that as a result of the new rules of the police statistics’ collection the most informative records of the police on homicides were created between 1931-1938, where the mentioned 7 types of deprivation of life (Figure 4)39 give us a general view of the homicides in Lithuania. If we excluded abortion (which is usually not considered as a homicide, but we should take into account the concept of interwar Lithuania), it would vary from 200 to 300 murders per year. However, in the data provided by the source, there were some discrepancies in the sums of the different kinds of homicides, making the source only partially reliable.

Figure 4. Deprivation of life according to the causes recorded by the police in Lithuania between 1931-1938

Source: Police, 1939, No 27.

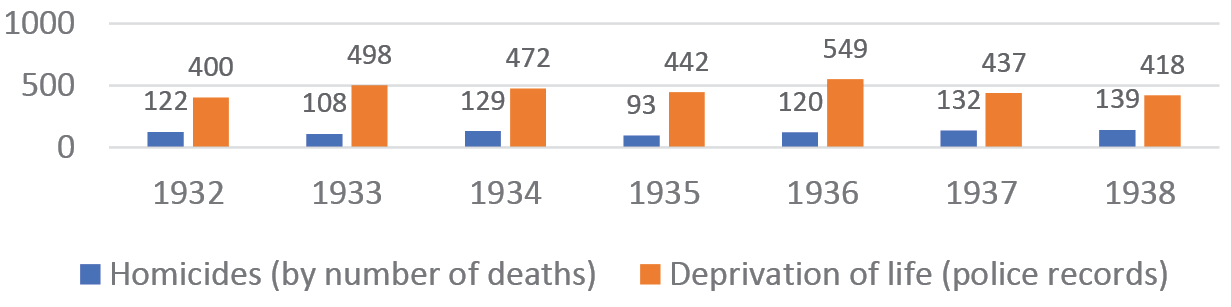

Also, when comparing the police records of deprivation of life with the homicides by the causes of death (from medical records), it must be pointed out that there are very significant differences between the actual victims and the police-reported homicides (Figure 5). 3-4 times bigger numbers of homicides reported by the police, apparently, show that the police records included not only homicide, infanticide and abortion but also preparation for murder and attempted murder as well as persuasion and help to commit suicide40. For example, in 1939, the police reported 136 homicides, 66 infanticide cases, 154 abortions, 87 cases of preparation to murder and attempted murder and 3 cases of persuasion and help to commit suicide41. It means that at least 20 % of the police-recorded cases of deprivation of life were attempted murders. The aforementioned attempted murders and homicides related to suicides were not collected until 1937, making medical records the only reliable source for statistical homicide research. It is important to highlight the fact that medical records do not reflect infanticide rates, simply meaning “pure” numbers of homicides in the 1930s Lithuania. Our data show that “pure” homicide rates were relatively stable at the time, varying from 122 in 1932, going down to 93 homicides in 1935 and rising to 139 in 1938 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Homicide victims versus deprivation of life in Lithuania between 1932-1938

Source: Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania, Vol. 5-11; Police, 1939, No 27.

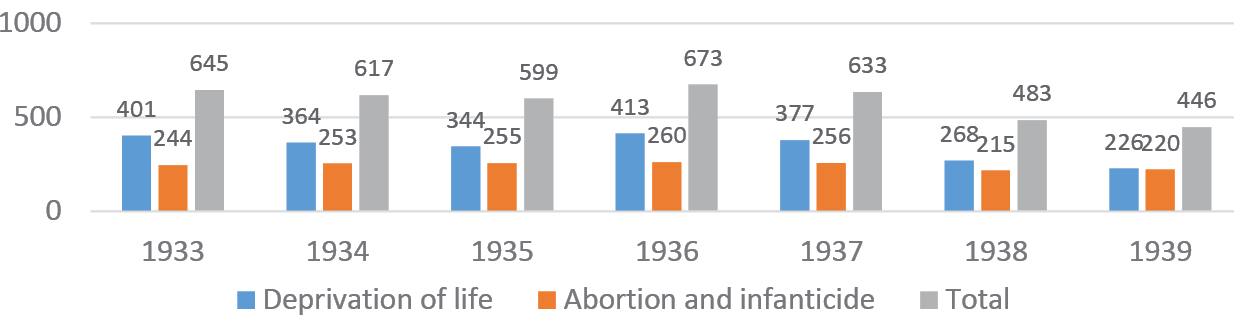

The most popular source in the Lithuanian historiography for crime statistics is the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania. Yet, the usage of the terms to define homicide, counting attempted murders and taking the territorial change (with the Klaipėda Region or without) into account, shows its disadvantages in comparison to the more accurate police data. In the police crime data of 1931-1934, the term deprivation of life was used and distinguished into 5 types: for profit, during brawls, infanticide, abortion and others (Figure 6). Between 1935-1939 the homicide-related police statistical data were distinguished only into two groups: deprivation of life and abortion and infanticide, making it even more complicated to use the data for actual research of homicides at the time (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Police-registered cases of deprivation of life by type between 1931-1934 (without the Klaipėda Region)

Source: Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania, Vol. 4-7.

Figure 7. Police-registered deprivations of life by type between 1935-1939 (with the Klaipėda Region between 1933-1935, without – between 1936-1939)

Source: Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania, Vol. 6-12.

Without critical evaluation, this data was used by Smaliukas and Urbelienė (1994). They have not explained their work methodology, only stating that they have analysed the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania, but the statistics that they have published only partially match the yearbooks. The scholars have used the term deprivation of life without any explanation, which is quite clear for the years 1935-1939 but is not in the period of 1931-1934, making the analysis of Smaliukas and Urbelienė untrustworthy.

However, even the unreliable police records reflect some tendencies of homicides as a social phenomenon. For example, statistics for the 1935-1936 murder motives in Lithuania show that revenge was the most common motive for murder. According to the source “It is true, it is very common to take revenge in Lithuania, sometimes for the smallest reasons, let’s say, for testifying against him in court, for an insult or when for some otherwise unimportant things one pays off his life.”42 It should be mentioned that the violence in the society was explained as a legacy of the First World War, believing that it demoralised the society, people lost the sense of responsibility for their actions and started to live in the present day without thinking about the future43. Family conflicts, unrequited love, quarrels and murders out of hate were typical homicides at that time, which signals domestic violence problems in Interwar Lithuania (Černevičiūtė & Kareniauskaitė, 2021). Most of the homicides were committed in the rural areas (except for infanticide) (Table 2), for example, in 1931, 1932, 1933, 1934 only 2, 3, 1 and 4 homicides were committed in the capital Kaunas, respectively. In other cities, there were one or two homicides registered per year44. These tendencies could be explained by the agricultural society of Interwar Lithuania, where most of the population was living in the villages but not in the cities.

Table 2. The police-registered homicides and attempted homicides by motives in Lithuania between 1935-1936

|

Motive |

1935 |

1936 |

|

Revenge |

38 |

24 |

|

Family conflict |

16 |

24 |

|

Unrequited love |

10 |

20 |

|

Quarrels |

14 |

17 |

|

In brawl fights |

16 |

9 |

|

In order to get an inheritance |

12 |

7 |

|

During a robbery |

5 |

8 |

|

Due to negligence |

4 |

2 |

|

For-profit |

5 |

2 |

|

Murders committed by the mentally ill |

2 |

4 |

|

Out of hate |

- |

5 |

|

To avoid paying a debt to a debtor |

- |

1 |

|

To avoid paying alimony and out of shame |

8 |

1 |

|

In an attempt to rape |

1 |

2 |

|

Self-defence |

- |

1 |

|

Obsession to kill |

1 |

- |

Source: Reference Book of Criminalistics, 1937, No 14.

The critical analysis of the official statistical data of medical and police records provides only a partial view of the homicides’ phenomenon in interwar Lithuania. Further analysis is welcome, the police-provided data of the 1930s could be recalculated taking only homicides committed for profit, during brawls and others in consideration and comparing them to the data of homicides by a cause of death. Additionally, the homicide rates per population with estimated errors would provide an opportunity for cross-national comparisons. Also, a study of the court statistical data records on homicides would reveal the characteristics of perpetrators and provide observations about the interwar Lithuania’s penal policy.

Conclusion

The Central Statistical Bureau had been publishing statistical data relevant to the investigation of homicides in Statistical Bulletins and the Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania since 1924. In the homicide studies, these statistical sources are problematic due to an unclear data collection methodology, the use of different homicide terms, unrealistic definitions of urban and rural areas and the changes in Lithuania’s territory and population.

We cannot determine the exact rates of the 1930s homicides due to the change in the homicide terminology and its content. Between 1924-1931 the term violent deaths, except suicides, was used, and homicides were not singled out. The analysis also shows that until 1931 violent deaths also included homicides and accidental deaths. From 1932 to 1939 violent deaths were divided into 4 groups: suicide, homicide, accidents and other violence. The more detailed data of the 1930s have revealed that most frequent victims of homicide were in the 15-29 and 29-44 age groups for men, while the 15-29 age group stands out for females. The most common method of killing was shooting.

The police-published homicide statistics also reveal a problem of terminology. According to the Penal Statute of Lithuania, deprivation of life distinguished crimes into homicide; infanticide; abortion; preparation to murder; attempted murder; persuasion and help to commit suicide. However, this terminology was only partially reflected in the police statistics, as between 1927-1930 the police used the term homicides and classified them into the ones committed: for-profit; during brawls and for other purposes. Infanticide was separated from homicides. If not counting others, infanticide was the most common murder type in interwar Lithuania.

Since 1931, the statistics of the police used the term of deprivation of life and distinguished it into 7 types according to the motive: for-profit; during brawls; defending one’s own life or the lives of others; involuntary; infanticide; abortion and for other purposes. It did not include dead bodies found, suicides and accidental deaths.

After analysing the 1931-1938 data on deprivation of life, excluding abortions, homicides would vary from 200 to 300 per year. When comparing all deprivations of life with homicides by the cause of death, it can be concluded that these figures included preparation for murder and attempted murder as well as persuasion and help to commit suicide. Thus, due to the change in the terminology and the inclusion of attempted murders, the police statistics can be considered unreliable.

Homicides are the most precisely quantitatively defined by the rates of causes of death, which in 1932-1938 Lithuania were relatively stable with an amplitude of 93-139 murders per year. On a basis of the analysis of the police statistical data, it is possible to identify at least 4 main types of homicides in interwar Lithuania: reproductive – infanticide and abortions, aggressive – killings during brawls, economic – for profit as well as unintentional homicides that happened during accidents.

Funding. This article is a part of the postdoctoral fellowship project Homicides and Punishments in Lithuania in 1918-1940. This project has received funding from the European Social Fund (project No 09.3.3-LMT-K-712-19-0144) under a grant agreement with the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT).

References

Aebi M. F., Linde, A. (2016) Long-Term Trends in Crime: Continuity and Change, P. Knepper, A. Johansen (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the history of crime and criminal justice, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 57-87;

Babachinaitė, G., Paulikas V. (2002). Nedarbas ir nusikalstamumas Lietuvos kaime 1918–1940 [Unemployment and Crime Rate in Lithuania in 1918-1990]. Jurisprudencija, Vol. 26, pp. 107-118, https://repository.mruni.eu/handle/007/14041;

Černevičiūtė S., Kareniauskaitė M. (2021). Pati kalta? Smurto prieš moteris istorija XX a. Lietuvoje [“It’s Her Own Fault?”: History of Violence Against Women in 20th Century Lithuania]. Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas;

Černevičiūtė S., Kaubrys S. (2014) Kartuvių kilpa, kulka ir dujų kamera: mirties bausmė Lietuvoje 1918–1940 metais: monografija [The Gallows’ Loop, the Bullet and the Gas Chamber: The Death Penalty in Lithuania in 1918-1940: the monograph]. Vilnius: Gimtasis žodis;

Eisner M. (2003). Long-Term Historical Trends in Violent Crime. Crime and Justice, Vol. 30, pp. 83-142; https://www.jstor.org/stable/1147697;

Gaučas P. (1978). Gyventojų skaičius Lietuvoje 1923–1939 metais [Population in Lithuania in 1923-1939]. Lietuvos TSR aukštųjų mokyklų mokslo darbai. Geografija ir geologija, No 14;

Gurr, T. R. (1981). Historical Trends in Violent Crime: A Critical Review of the Evidence. Crime and Justice, Vol. 3, pp. 295-353, https://doi.org/10.1086/449082;

Ylikangas, H., Karonen P., Lehti M. (2001) Five Centuries of Violence in Finland and the Baltic Area. Columbus: Ohio State University Press;

Kivivuori, J. (2017) Veli Verkko as an early criminologist: a case study in scientific conflict and paradigm shift. Scandinavian Journal of History, Vol. 42, No 2, https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2016.1265854;

Kivivuori, J., Rautelin, M., Büchert Netterstrøm, J., Lindström, D., Bergsdóttir, G.S., Jónasson, J.O., Lehti, M., Granath, S., Okholm, M.M. and Karonen, P. (2022). Nordic Homicide in Deep Time: Lethal Violence in the Early Modern Era and Present Times. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33134/HUP-15;

Lane R. (1979). Violent Death in the City: Suicide, Accident, and Murder in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia, Cambridge: Harvard University Press;

Laurinavičius Č. (2009). Lietuvos sienų raida XX amžiuje [Development of Lithuanian borders in the 20th century]. Ed. L. Daukšytė, Lietuvos sienos: tūkstantmečio istorija. [Borders of Lithuania: a millennium of history]. Vilnius: Baltos lankos;

Lehti, M. (2001a) Homicide Trends in Finland and Estonia in 1880-1940: Consequences of the Demographic, Social and Political Effects of Industrialization. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, Vol. 2, No 11, pp. 50–71, https://doi.org/10.1080/140438501317205547;

Lehti, M. (2001b). The Homicide wave in Finland from 1905 to 1932. Ed. T. Lappi-Seppälä, Homicide in Finland: Trends and Patterns in Historical and Comparative Perspective. Helsinki: National Research Institute of Legal Policy;

Maksimaitis M. (2001) Lietuvos teisės šaltiniai 1918–1940 metais [Law sources of Lithuania in 1918-1940]. Vilnius: Justitia;

Martišius S. A. (2009). Tarpukario Lietuvos statistika ir jos kūrėjai [Statistics of interwar Lithuania and its creators]. Lietuvos Statistikos Darbai, 48(1), pp. 4-14, https://doi.org/10.15388/LJS.2009.13952;

Monkkonen E. (2006). Homicide: Explaining America’s Exceptionalism. The American Historical Review, Vol. 111, No 1, pp. 76–94 https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.111.1.76;

Monkkonen E. (2001). New Standards for Historical Homicide Research. Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies, Vol. 5, No 2, pp. 5-26, https://doi.org/10.4000/chs.733;

Norkus Z. (2014). Du nepriklausomybės dvidešimtmečiai: kapitalizmas, klasės ir demokratija Pirmojoje ir Antrojoje Lietuvos Respublikoje lyginamosios istorinės sociologijos požiūriu [Two Twenty-Year Periods of Independence: Capitalism, Class and Democracy in the First and Second Republics of Lithuania from the Point of View of Comparative Historical Sociology]. Vilnius: Aukso žuvys, http://web.vu.lt/fsf/z.norkus/files/2014/02/Du20me%C4%8Diai.pdf;

Palskys E. (1995). Lietuvos kriminalistikos istorijos apybraižos: (1918–1940) [Outlines of Lithuanian criminalistics history (1918-1940)]. Vilnius: Lietuvos policijos akademija;

Smaliukas J., Urbelienė J. (1994) Nusikalstamumo raida Lietuvoje 1918–1993 m. m. [Development of crimes in Lithuania in 1918-1993]. Vilnius: Lietuvos respublikos prokuratūra;

Spierenburg, P. (2001). Encyclopedia of European social history: from 1350 to 2000, Vol. 3. Ed. P. N. Stearns, New York: Scribner, pp. 335–349;

Spierenburg, P. (2008). A History of Murder: Personal Violence in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present. Cambridge: Polity, 2008;

Spierenburg P. (2012) Long-Term Historical Trends of Homicide in Europe. Liem, M. C. A., Pridemore, W. A. (eds), Handbook of European Homicide Research: Patterns, Explanations, and Country Studies, New York: Springer, pp. 25–38, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0466-8;

Vuorela, M. (2018). The historical criminal statistics of Finland 1842-2015 – a systematic comparison to Sweden. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, Vol. 42, Is. 2-3, pp. 95-117, https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2017.1295395;

Von Hofer, H. (1990). Homicide in Swedish statistics, 1750-1988. Ed. A. Snare. Criminal Violence in Scandinavia: Selected Topics, Oslo: Norwegian University Press, pp. 29-45.

Sources of Official Statistics

1. 32 Nr. Mirimai mirties priežastimi. Didž. Lietuvos naturalinio gyventojų judėjimo 1924 m. daviniai. Statistikos biuletenis [Bulletin of Statistics], 1925, No 5, pp. 48-49;

2. Kaikurie stambesni, policijos užregistruoti, nusikalstamieji darbai 1931–1938 metais. Kriminalistikos žinynas [Reference Book of Criminalistics], 1939, No 27, pp. 132-135;

3. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1924-1926 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1924-1926], Vol. 1, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1927;

4. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1927-1928 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1927-1928], Vol. 2, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1929;

5. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1929-1930 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1929-1930], Vol. 3, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1931;

6. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1931 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1931], Vol. 4, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1932;

7. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1932 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1932], Vol. 5, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1933;

8. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1933 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1933], Vol. 6, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1934;

9. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1934 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1934], Vol. 7, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1935;

10. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1935 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1935], Vol. 8, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1936;

11. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1936 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1936], Vol. 9, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1937;

12. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1937 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1937], Vol. 10, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1938;

13. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1938 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1938], Vol. 11, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1939;

14. Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1939 [Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania 1939], Vol. 12, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1940;

15. Mirusieji miestuose ir kaimuose mirties priežastimi. Lietuvos centrinis valstybės archyvas [Lithuanian Central State Archives], fund 418, inventory 1, file 4;

16. Policijos užregistruotų nusikalstamų darbų statistika 1939 metų. Kriminalistikos žinynas [Reference Book of Criminalistics], 1940, No 33, pp. 138-139;

17. Statistikos žinios apie įvairius kriminalinius atsitikimus, įvykusius visoj Lietuvoj nuo 1928 m. sausio mėn. 1 d. iki 1928 m. gruodžio 31 d. Policija [Police], 1929, No 6, pp. 106-107;

18. Statistikos žinios apie įvairius kriminalinius atsitikimus, įvykusius visoj Lietuvoj laikotarpy nuo 1930 m. sausio mėn. 1 d. iki 1931 m. sausio 1 d. Policija [Police], 1931, No 2, p. 35.

1 The Historical Homicide Monitor (HHM) has been developed in the framework of the project Nordic Homicide from Past to Present led by prof. Janne Kivivuori (University of Helsinki), which has brought together the Nordic criminologists and historians researching lethal violence. More about the project and the HHM: https://blogs.helsinki.fi/historicalhomicidemonitor/project-2/.

2 Original in Lithuanian: “Statistika – tai faktai, pakeisti skaičiais; tie skaičiai parodo mums kokiu keliu mes ėjom, kur mus tas kelias veda ir, jeigu reikalinga, kaip geriau tą kelią pakeisti kitu, nauju keliu”. Alfa. Kriminalinė statistika. Policija, 1931, No 11, p. 215.

3 Volumes of Statistical Yearbooks of Lithuania have been published on the site of the Official Statistics Portal: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/.

4 Statistical Bulletin. https://www.epaveldas.lt/preview?id=C1C1B0000078024.

6 Reference Book of Criminalistics. https://www.epaveldas.lt/preview?id=C10000221382.

7 The author is thankful for valuable comments and suggestions on the historical homicide statistics research for Prof. Aleksandras Dobryninas, Prof. Zenonas Norkus, Prof. Paul Knepper and Prof. Janne Kivivuori.

8 The project Historical Sociology of Modern Restorations: A Cross-Time Comparative Study of Post-Communist Transformations in the Baltic States (2018-2022) led by the sociologist Zenonas Norkus. More about the project: https://lida.dataverse.lt/dataverse/HistatData_Baltic.

9 Norkus, Z., Ambrulevičiūtė, A., Markevičiūtė, J., Morkevičius, V., Žvaliauskas, G. (2021) Causes of Death of the Population in Lithuania, 1919-1939. Lithuanian Data Archive for the HSS (LiDA), V1, https://hdl.handle.net/21.12137/K4ZXOA.

10 Lietuvos statistika 1920-1930 metais. Kaunas: Centralinis statistikos biuras, 1931, p. 9.

11 Centralinis statistikos biuras. Vyriausybės žinios, 1921 05 20, No 60-587.

12 Pirmieji surašymo daviniai. Statistikos biuletenis, 1923, No 1, p. 3-4.

13 Lietuvos gyventojai. Pirmojo 1923 m. rugsėjo 17 d. visuotino surašymo duomenys. Kaunas: Finansų ministerija. Centralinis statistikos biuras, 1926.

14 Lietuvos statistika 1920-1930 metais. Kaunas: Centralinis statistikos biuras, 1931, p. 15.

15 Valstybės statistikos įstatymas. Vyriausybės žinios, 1930 07 14, No 332-2272.

16 32 Nr. Mirimai mirties priežastimi. Didž. Lietuvos naturalinio gyventojų judėjimo 1924 m. daviniai. Statistikos biuletenis, 1925, No 5, p. 48-49.

17 In 1940 (full year from January through December), there were 31 homicides registered in the urban areas, 89 in the rural, in total – 120. Mirusieji miestuose ir kaimuose mirties priežastimi. Lietuvos centrinis valstybės archyvas [Lithuanian Central State Archives – later on LCVA], fund 418, inventory 1, file 4, page 6.

18 It should be mentioned that only 20 files of the Central Statistical Bureau have survived until nowadays in the fund of No 418, that is preserved in LCVA. None of these files explain methodologies of the statistical data collection.

19 23 Nr. Miestų ir miestelių su gyventojų skaičiumi virš 2000 žm.*) sąrašas. Statistikos biuletenis, 1924, No 6, p. 25.

20 Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1932, T. 5, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1933, p. 32-33.

21 Lietuvos statistika 1920-1930 metais. Kaunas: Centralinis statistikos biuras, 1931, p. 28-29.

22 Lietuvos statistika 1920-1930 metais. Kaunas: Centralinis statistikos biuras, 1931, p. 29.

23 Knibbs, G. H. The International Classification of Disease and Causes of Death and its Revision. The Medical Journal of Australia. 1929 01 05, Vol. 1, p. 8-9.

24 32 Nr. Mirimai mirties priežastimi. Didž. Lietuvos naturalinio gyventojų judėjimo 1924 m. daviniai. Statistikos biuletenis, No 5, p. 48.

25 It is interesting to note that the execution of death sentences was mentioned among the other forms of violence, but no statistics were provided, although previous research on the death penalty proves that executions took place in Lithuania at least a few per year (Černevičiūtė, S., Kaubrys S. 2014). Ironically, the statistical yearbook explains, “Deaths from this violent death are included in other tables under the category of accidents.“ So, state violence was also recorded and executions were called accidental deaths.

26 The arrest was a dangerous situation also for others involved or around: 10 policemen and 3 civilians were killed, 12 policemen and 11 civilians got injured. Lietuvos policija 1918-1928. Ed. I. Tamašauskas, Kaunas: V. R. M. Piliečių apsaugos departamentas, 1930, p. 179

27 Ibid., p. 180.

28 Visiems apskričių viršininkams ir kriminalinės policijos viršininkui. 14417 nr. Kriminalinės Žinios Policijai. 1926, No 1, p. 8.

29 For example, the police-provided data in the journal Police show that the total number of deprivation of life cases was 389 in 1931 and 400 in 1932, but the Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania recorded 386 in 1931 and 399 in 1932, so the discrepencies are by only a few numbers. Kriminalistikos žinynas, 1939, No. 27, p. 132; Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1931, Vol. 4, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1932, p. 341; Lietuvos statistikos metraštis 1932, Vol. 5, Kaunas: Spindulio b-vės sp., 1933, p. 268-269.

30 It should be mentioned that in Czarist Russia only the sections on political and religious crimes came into effect, as the rest of the code was considered too liberal for Russia. In Lithuania, the German military administration introduced the 1903 Russian Criminal Code in full in 1917 (Maksimaitis, 2001, p. 55-56).

31 “Kas nusikalto ką nužudęs, tas baudžiamas kalėti sunkiųjų darbų kalėjime ne trumpiau kaip aštuoneris metus.” Baudžiamasis statutas su papildomaisiais baudžiamaisiais įstatymais ir komentarais, sudarytais iš Rusijos Senato ir Lietuvos Vyriausiojo Tribunolo sprendimų bei kitų aiškinimų. Red. Martynas Kavolis, Simanas Bieliackinas. Kaunas: D. Gutmano knygynas, 1934, p. 371.

32 Visiems apskričių viršininkams ir kriminalinės policijos viršininkui. 14417 nr. Kriminalinės Žinios Policijai. 1926, No 1, p. 8.

33 Statistikos žinios apie įvairius kriminalinius atsitikimus. Ibid.

34 Rimka, A. Policijos statistikos žinios. Policija, 1927, No 9, p. 8.

35 Povilaitis, A. Nusikaltimai, išeikvojimai ir jų baimė. Kova su piktu radijo bangomis, Kaunas: Kriminalistikos žinynas, 1938, p. 247.

36 „Kai kurios policijos įstaigos, paduodančios žinias apie žmogžudystes, pritaikydavo prie žmogžudysčių ir savižudybes; vagystes su išlaužimu - prie plėšimų ir t.t. T. y. buvo išaikinta, kad daugelis policijos valdininkų silpnai moka kvalifikuoti nusikaltimus.” Budrevičius, K. Policijos statistikos žinios. Policija, 1928, No 1, p. 27.

37 1930 m. lapkričio 21 d. visiems apskričių ir kriminalinės policijos rajonų viršininkams. Policija, 1930, No 23, p. 459; 1930 m. lapkričio 21 d. Piliečių apsaugos departamento aplinkraštis No 37. 200a. Piliečių Apsaugos Departamento Aplinkraščių Rinkinys. 1918 m. vasario 16–1931 m. gegužės 31 d. Kaunas: Piliečių Apsaugos Departamento leidinys, 1931, p. 216.

38 Statistinės žinios apie nusikalstamuosius darbus. Policijos departamento aplinkraščių sąvadas. 1937 m. birželio mėn. 1 d. Kaunas: “Policijos” laikraščio leidinys, 1937, p. 54.

39 Kai kurie stambesni, policijos užregistruoti, nusikalstamieji darbai 1931-1938 metais. Kriminalistikos žinynas, 1939, No. 27, p. 132-133.

40 Policijos užregistruotų nusikalstamų darbų statistika 1939 metų. Lentelių paaiškinimas. Kriminalistikos žinynas, 1940, No 33, p. 138.

41 Ibid.

42 „Tiesa, Lietuvoje kerštauti yra labai įprasta. Kai kada dėl menkiausių priežasčių, sakysime, dėl paliudijimo teisme jo nenaudai, dėl įžeidimo arba šiaip dėl kokių nesvarbių dalykų atsiteisiama gyvybe.” Valaitis, J. Žmogžudysčių priežastys Lietuvoje. Kriminalistikos žinynas. 1937, No 14, p. 84.

43 Budrevičius K. Ar nusikaltimų skaičius Lietuvoje didėja ar mažėja. Policija, 1931, No 2, p. 36.

44 Povilaitis, A. Nusikaltimai, išeikvojimai ir jų baimė. Kova su piktu radijo bangomis, Kaunas: Kriminalistikos žinynas, 1938, p. 247-248.