Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2020, vol. 11, no. 1(21), pp. 203–221 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2020.11.31

The Effect of Celebrity Endorsement on Instagram Fashion Purchase Intention: The Evidence from Indonesia

Halimin Herjanto (Corresponding author)

University of the Incarnate Word, United States of America

herjanto@uiwtx.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2917-0014

Michael Adiwijaya

Petra Christian University, Indonesia

michaels@petra.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6186-242X

Elizabeth Wijaya

Petra Christian University, Indonesia

michaels@petra.ac.id

Hatane Semuel

Petra Christian University, Indonesia

samy@petra.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5266-0137

Abstract. To maintain the significantly positive influence of celebrity endorsement (CE) on Instagram user consumption behavior, scholars and business practitioners are motivated to have a better understanding of this phenomenon. Literature on CE focuses on its direct effect on attitude toward various brand components; however, this study takes a different approach by developing a new conceptual model and a set of hypotheses that aims to generate a better picture of the relationship between two brand components (brand image and brand trust) and repurchase intention. The present study also examines the moderating role of CE in the relationship between brand image and brand trust as well as repurchase intention.

The hypotheses were tested using online survey data from 220 Indonesian respondents. To test the theoretical model, this study employs ordinary least square regression (OLS), as well as Baron and Kenny’s (1986) method to test moderating hypotheses. The results show that the hypothesized model of CE on brand image, brand trust and repurchase intention fits the data. In addition, the findings also demonstrate that CE moderates the relationship between brand image and brand trust, and between brand image and repurchase intention.

The findings offer important contributions to the academic by enriching the body of literature on online consumption behavior. They reveal the moderating effect of CE, and potentially inspire scholars to conduct further research. To business practitioners, this study suggests the importance of engaging with celebrities to endorse their brands. At the same time, to avoid the risk of reverse image, managers are recommended to think carefully about which celebrities are suitable to represent their brands.

Keywords: celebrity endorsement, brand image, brand trust, purchase intention.

Received: 10/3/2019. Accepted: 2/7/2020

Copyright © 2020 Halimin Herjanto , Michael Adiwijaya, Elizabeth Wijaya, Hatane Semuel. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

To improve their digital infrastructure, Indonesia introduced the Internet superhighway “Palapa Ring” that connects districts and cities across Indonesia (Beritasatu, 2019). As a result, 65% of Indonesian population, or 171 million Indonesians, have Internet access (Indonesia Investment, 2019). This Internet superhighway allows 96% of its users to experience online shopping through company websites and social media. Accordingly, in 2019 alone, Indonesian online shopping accounted for $20.3 billion, of which $2.3 billion, or nearly 12%, went to fashion-related purchasing (Datareportal, 2019). To encourage online spending, the Indonesian fashion industry employs local celebrities to represent and endorse their brands on their social media, such as Instagram (Danniswara et al., 2017). Although Instagram is claimed as Indonesian most preferable online shopping platform (Greenhouse, 2019) and is considered as a suitable marketing tool for the fashion industry (Moatti & Abecassis-Moedas, 2018), one third of the fashion industry suggests that CE on Instagram does not highlight their products, and therefore they do not view Instagram as an important platform (Ipsos, 2018). To ensure the fashion industry’s social media attractiveness and effectiveness, scholars attempted to find answers by more intensively examining the CE phenomenon. For example, Wahloonluck and Chokesamritpol’s (2013) study on Thai’s social media found that CE helps the ice cream industry reach its customers and promote its brands. To these authors, featuring celebrities on social media improves social media attractiveness. A different study by Phua, Syan and Lim (2018) on the effect of CE on US online E-cigarette consumption behavior revealed that CE improves customer engagement. Similarly, Djafarova and Rushworth’s (2017) investigation on British online purchasing habit documented that CE positively affects young female online purchasing decision. In contrast, other scholars have found that featuring celebrities on Instagram also potentially lowers a brand’s perceived uniqueness (De Veirman et al., 2017) and more importantly, the image of celebrities can overpower the fashion brand (Fong & Yazdanifard, 2014).

Adding to this inconsistency, none of these researchers above examined the effect of CE on Instagram in the context of the fashion industry. Thus, their findings may not be applicable to the fashion industry. In addition, most of this research was conducted outside Indonesia and thus the findings may not be suitable for Indonesian context. Based on these caveats, current studies into the effect of CE on Instagram are incomplete. Therefore, the subject is in need of further investigation (Totoatmojo, 2015). Thus, the present study aims to further explore the effect of celebrities on brand image and brand trust as well as purchase intention. In addition, this study also investigates the moderating effect of CE on the relationship among brand image, brand trust and repurchase intention in Indonesian context.

Conceptual framework

Purchase intention

Ajzen and Fishbein (2004) argue that intention is the most important mental state that serves as the gateway to determine customer behavior. Based on this definition, purchase intention can be translated as the degree of customer tendency to buy similar products or services in the near future (Diallo, 2012). To Lin and Lu (2010), the degree of purchase intention occurs when a customer simultaneously experiences a strong psychological state that stimulates willingness, wants and buying desire. According to Ajzen and Fishbein (2004), different psychological states are responsible for purchase intention. Among these psychological factors, Tseng and Lee (2013) suggest that different brand components are considered most important. It is because these brand components serve as evaluation tools that build stronger brand attitude that produces stronger purchase intention.

Brand image

Brand image is the product of a customer’s positive evaluation toward brand attributes which is stored in customer mind (Hsieh & Lindridge, 2015). According to Wang and Yang (2010), the strength of brand image is determined by its stability, favorability and uniqueness. That is, the consistency of quality performance, the likeability of brand attributes, and the distinctiveness of brand features generate stronger brand credibility and brand position in the customer-evoked set. This way, Chauhan (2013) concludes that strong brand image becomes a customer benchmark in making a decision. Accordingly, a strong brand image promotes brand trust (Liao et al., 2009) and repurchase intention (Wang & Yang, 2010).

Brand trust

Pribadi et al. (2019) argue that brand trust is one of the most important pillars of a strong brand. To these authors, brand trust is generated by the combination of brand personality and brand experience. That is, when a customer feels that their personality matches with the brand, they feel emotionally connected, and at the same time, it improves the positive experience with the brand. This way, this positive experience generates a higher brand trustworthiness and more importantly improves a customer’s sense of security and likability. As a result, brand trust positively contributes to a stronger brand attachment, brand commitment (Esch et al., 2006) and brand faithfulness (Pribadi et al., 2019).

Celebrity endorsement

CE can be explained as the validating statements made by celebrities or public figures in support of a brand with the aim of increasing the attractiveness of the brand (Zamudio, 2016). Seno and Lukas (2017) suggest that the more credible and attractive the celebrity is, the more effective the CE becomes. In other words, the celebrity’s degree of credibility enhances the trustworthiness of a brand, and his/her degree of attractiveness improves its likeability (Ohanian, 1990). In general, credibility is generated by a celebrity’s relevant knowledge, expertise and consumption experience of that brand (Forounhandeh et al., 2011) and a celebrity’s attractive physical characteristics, such as body shape or sexiness, promote the attractiveness of the brand (Erdogan et al., 2001). In today’s overflowing product availability, a customer has to decide which brands he/she needs to purchase. In this selection process, a customer tends to evaluate available brands based on personal experience as well as on the opinion of the public and experts. According to Bednall and Collings (2000), public and expert opinion is a strong influencer, particularly when a customer perceives the endorser as “fitting” with the brand. That is, the image of the endorser supports the image of the brand. Examples can include David Beckham and H&M fast clothing. David Beckham, a former England soccer captain, is represented as sporty, sexy and rebellious, and his image fits with the H&M motto “The H&M way”. According to Charbonneau and Garland (2010), celebrity “fitness” with a brand is crucial because the image of the celebrity transfers to and complements the brand. Accordingly, it improves customer brand awareness and differentiates the endorsed brand from its competitors (Sagar et al., 2011). A failure to find a perfect balance between a celebrity and a brand generates a reverse image, which leads to customer confusion and a negative attitude toward the brand (Charbonneau & Garland, 2010). Thus, the characteristics and image of the celebrity determine the success of the CE (Hakimi et al., 2011).

Celebrity endorsement on social media

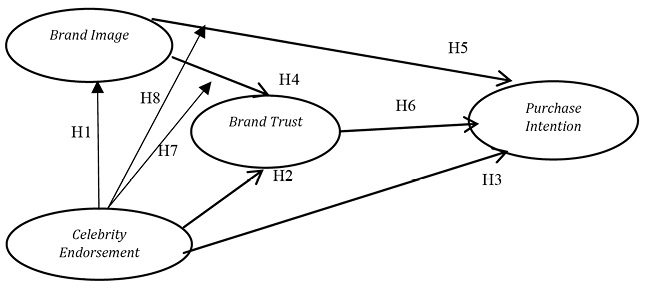

Recent studies show that CE boosts the fashion industry’s social media popularity and attractiveness (Danniswara et al., 2017). For example, based on 330 Korean Facebook users, Um (2013) found that CE helps to increase the need for affiliation and self-identity. To this author, following celebrity-endorsed fashion not only fulfils such need but also allows him/her to feel good about him/herself. Accordingly, this positive feeling promotes positive brand attitude and purchase intention. This finding confirmed Thanh’s (2016) Facebook study in Vietnam. Similarly, Cunningham and Bright’s (2012) study on the effect of CE on Twitter revealed that CE improves the perception of brand relevance. That is, Twitter users view an endorsed brand to fit with their interest. This finding supported Jin and Phua’s (2014) study on Twitter CE in the US. Laila and Sjabadhyni’s (2017) study on Indonesian Instagram online spending behavior noted that CE improves the online shopper’s willingness to repurchase. They argue that CE increases an Instagram user’s degree of perceived congruency. This finding reinforced Wahloonluck and Chokesamritpol’s (2013) study in Thailand. Despite these extensive efforts, Djafarova and Rushworth (2017) suggest that research on CE on social media is limited. Figure 1 presents a model of the direct and moderating effect of CE. This model offers a brief conceptual framework of the direct and indirect impact of the various constructs toward purchase intention.

Figure 1. The celebrity endorsement model

Source: Authors’ own contribution

Hypotheses development

The effect of celebrity endorsement on brand image

Traditionally, a brand is regarded as a unique product/service identifier that consists of name, design, style and words or logo (Omar & Williams, 2006). A customer views these brand characteristics as reflecting a manufacturer’s desire to distinguish their product’s value, culture and benefits. In other words, a customer perceives a brand as the manufacturer’s promise or guarantee to deliver a quality product (Merz et al., 2009). A manufacturer’s failure to fulfil its promise, or to fulfil it in a timely manner, hurts the brand experience (Pribadi et al., 2019). When a manufacturer’s promise is fulfilled, the image of the brand immediately improves (Maroko & Uncles, 2008); that is, it enhances a customer’s positive perception and beliefs (Nandan, 2005), which ultimately guides a customer to purchase the brand (Wijaya, 2013). Brand image is known as a customer’s overall impression and perception of the brand (Wymer, 2013). According to Wijaya (2013), building a strong brand image is a complex process that is determined by brand identity, brand competence, brand personality, brand attitude and brand association. Among these components, brand association is the only component that is always associated with external factors, such as a celebrity. For example, Under Armour is associated with Dwayne “The Rock” Jackson, and Nike is associated with Michael Jordan. This association encourages a customer who idolizes a certain celebrity to become more involved (Gong & Li, 2017) and to view the value and image of their celebrity idol within the brand (Chan et al., 2013). Accordingly, this study hypothesizes:

H1: CE positively influences brand image.

The effect of celebrity endorsement on brand trust

Brand trust is customer’s confidence in the brand’s ability to deliver a high-quality performance (Wang & Emurian, 2005). A high degree of customer confidence develops when a brand closely relates to a customer’s self-concept, is in line with a customer values and can fulfil a customer’s need (Mowen & Minor, 2000). Hegner and Jevons (2016) argue that when a brand is able to gain a customer’s confidence, it allows the customer to predict the brand’s future performance and accordingly, the customer is comfortable in continuing to consume the product (Laroche et al., 2012). However, Nick Black (2009), the managing partner of Intensions Consulting, suggests that to maximize the strength of brand trust, marketers should associate their brands with customer trust drivers. These include external opinion leaders such as celebrities (Erdogan et al., 2001). A celebrity is viewed as a famous person who enjoys public recognition for his or her achievements or dedication in a specific field (Karasiewicz & Kowalczuk, 2014). This definition shows that a celebrity is someone who is experienced and an expert in his or her field and therefore, a customer tends to view a celebrity as an alternative source of information. As a public figure, a celebrity’s behaviors are always subject to general public scrutiny. A customer evaluates a celebrity’s knowledge and behavior and decides whether the celebrity is capable of maintaining these to meet public expectations. This includes what he/she endorses and encourages people to use or wear. For example, a customer trusts that as a professional basketball player, Michael Jordan has a good knowledge about basketball. This includes what gear he needs to wear to achieve his best performance. When a customer sees him wearing his endorsed Nike shoes during his basketball matches or in his personal life, he/she is more likely to trust that Michael Jordan is genuinely wearing the shoes because of their performance. Accordingly, seeing Michael Jordan’s trust in the brand will encourage a customer to trust the brand as well. Based on this argument, the present study hypothesizes that:

H2: CE positively influences brand trust.

The effect of celebrity endorsement on purchase intention

Self-identity theory maintains that a customer compares and evaluates whether he/she meets the identity that he/she wants to portray to the rest of the group members or society (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). When a customer wants to maintain or improve his/her status or belongingness, the customer is more likely to enhance his/her self-image by adopting a brand that has been endorsed by celebrities. Psychologically, adopting a celebrity-endorsed brand reinforces a customer’s self-identity and to some extent, it provides a sense of personal and status similarity with their idol (Dib & Johnson, 2019). As a result, a customer feels better about him/herself with a boost in self-confidence, and life becomes more enjoyable and meaningful (Tantiseneepong et al., 2012). Consequently, to maintain such positive feeling, a customer tends to develop a better brand attitude (Chin et al., 2017), which encourages a stronger connection to the brand (Escalas & Bettman, 2015) and produces a solid brand preference (Albert et al., 2017). Ultimately, it improves a customer’s purchase intention. Based on this discussion, it can be said that:

H3: CE positively influences purchase intention.

The effect of brand image on brand trust

Makasi et al. (2014) suggest that a strong brand image provides a competitive advantage. That is, a strong brand image provides a strong indication of product quality (Khasawneh & Hasouneh, 2010) and conveys an overall positive impression (Chao et al., 2015), which helps reduce a customer’s perception of risk while improving a customer’s familiarity with the brand (Makasi et al., 2014). During this process of brand familiarization, brand image serves as the first brand characteristic that the customer encounters. Psychologically, a customer screens the overall brand attributes, and if these attributes match or exceed his/her expectations, a brand is awarded a positive brand image. To illustrate, Abercrombie and Fitch (A&F) portrays itself as a fashion leader amongst young people. When a customer visits A&F stores and encounters product design, store ambiance, floor staff and advertising materials, it confirms his/her expectations and creates a stronger brand image. Different studies have shown that brand image is responsible for strengthening brand trust. For example, based on 355 European participants, Esch et al. (2006) found that brand image strengthens brand trust. Similarly, Liao et al. (2009) confirmed that brand image is responsible for brand trust. Recently, Alhaddad’s (2015) Syrian study also found that brand image directly affects brand trust. Based on the literature review, this study also proposes that:

H4: Brand image positively influences brand trust.

The effect of brand image on purchase intention

Although online transactions offer convenience, Harridge-March (2006) argues that there are still customers who do not trust such transactions. One reason for this is that a brand may have a weak brand image (Wu et al., 2011). For a customer, brand image is a barometer to evaluate the acceptability and suitability of a brand. If a brand is involved in negative events, a customer is more likely to perceive the brand negatively and accordingly he/she will avoid association with the brand. For example, in early 2000, Nike was found to be using sweatshops in Asia. This scandal led to some of Nike’s customers switching brands because they did not want to be associated with Nike’s negative image. Thus, scholars concluded that brand image is important because it is responsible for building customers’ positive perception (Alhaddad, 2015) and dedication toward the brand (Malik et al., 2012), which in turn is responsible for loyalty and future purchase intention (Porral & Lang, 2015). These findings were confirmed by Tariq et al. (2013) and Wu et al. (2011), who also recognized the effect of brand image on purchase intention. These sets of studies show that brand image positively improves a customer’s purchase intention. Thus, the present study hypothesizes that:

H5: Brand image positively influences purchase intention.

The effect of brand trust on purchase intention

Pribadi et al. (2019) suggest that brand trust is crucial to building customer loyalty. That is, the more a customer trusts a brand, the higher his/her customer loyalty is and accordingly, the more profitable and sustainable the fashion brand becomes. In other words, brand trust encourages a stronger and more enthusiastic brand relationship (Xie et al., 2014). According to Kim et al. (2015), a close relationship can reduce negative perceptions and improve a customer’s tolerance towards the brand. This is because a customer is likely to believe that the brand will not take advantage of him/her and will always deliver good quality products. Accordingly, when a customer receives consistently good products and experiences, he/she is more willing to rely on the brand and ultimately to commit to future purchases (Hahn & Kim, 2009). Punyatoya (2014) has confirmed that strong brand trust leads to repurchase intention. Accordingly, this study hypothesizes that:

H6: Brand trust positively influences purchase intention.

The moderating effect of celebrity endorsement

The effect of brand image on brand trust is regarded as one of the most important relationships in building a strong brand (Esch et al., 2006). The authors suggest that without a strong brand image, a brand will have no relationship with a customer. Alfanda et al. (2018) maintain that this relationship is made more powerful through the use of CE. Dib and Johnson (2019) point out that when a customer views a celebrity image, he/she transfers it to the brand the celebrity is endorsing. That is, a customer no longer perceives the brand as ordinary; instead, the brand now serves as a tool to bring the customer one step closer to their idolized celebrity. For example, a basketball enthusiast customer feels that his/her performance improves by wearing a pair of Air Jordan, or a customer who wears something from the Love Bravery clothing line feels that he/she has a similar fashion sense to Lady Gaga. Accordingly, a customer feels that a brand improves their personal and social identity (Arsena et al., 2014). Over time, such positive experiences improve a customer’s confidence, trust in the brand, and ultimately encourage purchase intention. Thus, this study hypothesizes that:

H7: CE positively moderates the relationship between brand image and brand trust.

H8: CE positively moderates the relationship between brand image and purchase intention.

Methodology

Considering the aim of this research is to examine the effect of CE on Instagram users, the data for this study were collected online using a convenience sampling method between 1 September 2018 and 30 November 2018. The authors selected this time frame because during this particular period Indonesian Instagram traffic jumped significantly (Napoleon, 2020), and online fashion industries intensified their celebrity endorsements to boost their sales during this holiday season. An online survey was developed and posted to the Petra Christian University’s student announcement site. Al-Maghrabi et al. (2011) suggest that an online survey is suitable for online behavior related research. At the beginning of the online survey, participants were asked to answer screening questions by selecting at least one local celebrity (including Michelle Pangemanan, Ruth Stefanie, Lily Stephanie and Stephanie Gunawan) that they are currently following on Instagram. Participants accomplished this by choosing the celebrity from a drop down list, and followed the rest of the questions based on their Instagram online purchase experience. These screening questions ensure the eligibility of participants and suitability and quality of data collected. Those who had never bought from online shops endorsed by celebrities and who did not have an Instagram account were excluded. The characteristics of this sample are discussed in the next section.

All the scales adopted in this study were borrowed and adjusted from the published literature. These scales used five-point Likert-type scales anchored at extremely disagree to extremely agree. Two CE scales were borrowed from Ohanian (1990), two original brand image items were adopted from Aaker (1996), five brand trust items were modified from Delgado-Ballester and Munuera-Aleman (2000), and two purchase intention scales were transformed from Moon et al. (2008). To ensure the accuracy of the adopted items, this study followed McGorry’s (2000) double translation procedures. The questionnaire was first translated into Indonesian by a professional translator, then the Indonesian version was re-translated to English by one of the authors.

Data analysis and discussion

A total of 249 university students from different disciplines at the Petra Christian University in Indonesia participated in this study; however, 29 of these respondents were excluded due to incomplete responses. These respondents were Indonesian citizens currently living in Surabaya metropolitan. In total, 66 % or 144 respondents were female, and 34% or 76 respondents were male. All the respondents were between 17 and 37 years of age. In total, 43% of respondents earned between 3 and 5 million rupiah, 39% earned between 6 and 10 million rupiah, 9% earned between 11 and 15 million rupiah, and the final 9% earned more than 15 million rupiah. Out of the total number of respondents, 9%, 23%, 46% and 22% spent less than 1 hour, between 1 and 3 hours, between 3 and 5 hours and more than 5 hours on social media respectively. Altogether, 61% of respondents believed that celebrity endorsement affected their online purchases, while 39% did not. With regard to endorsements, 79%, 18%, 2% and 1% of respondents saw a celebrity endorsement a week ago, two weeks ago, one month ago and more than a month ago respectively, while 23% of respondents were exposed to 1- 3 celebrity endorsements per week, and 77% were exposed to more than 3 celebrity endorsements per week.

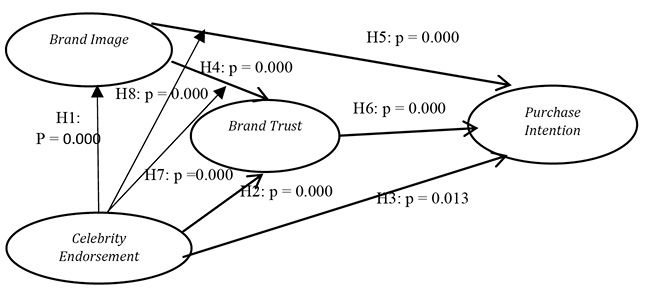

Figure 2. The statistic results of celebrity endorsement model

Source: Authors’ own contribution

To test the validity of each scale, a principle component analysis with Eigenvalue >1 was conducted and then rotated by varimax factor rotation. In addition, a minimum value of 0.40 was used to indicate the loading of any factors. Although the Cronbach alpha of brand image was 0.684, less than the standard consensus score of 0.7, Rahimnia and Hassanzadeh (2013) suggest that Cronbach alpha scores larger than 0.6 are acceptable. Table 1 provides the psychometric characteristics of the adopted scales. Displayed in this table are the suitableness of scale (validity), the consistency of scale (reliability) and the mean of each scale. Additionally, Figure 2 presents the model of the direct and indirect impact of CE with p values.

Table 1. Brief Overview of the Psychometric Properties Scale.

|

Scale |

Means |

λ |

α |

|

CE |

|

|

.858 |

|

A celebrity has good experiences in choosing their fashion. |

4.02 |

.847 |

|

|

A celebrity has a good expertise in choosing their fashion. |

3.96 |

.886 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brand image |

|

|

.684 |

|

This online shop has a reputable name. |

3.67 |

.772 |

|

|

This online shop is known as the trendiest fashion shop online. |

3.40 |

.822 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brand trust |

|

|

.885 |

|

This online shop will: |

|

|

|

|

Offer me the latest fashion style |

3.77 |

.665 |

|

|

Fulfil my fashion needs |

3.94 |

.744 |

|

|

Simplify my fashion transaction process |

3.78 |

.804 |

|

|

Be interested in my present and future satisfaction |

3.80 |

.795 |

|

|

Offer me good advice for my fashion needs |

3.67 |

.761 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Purchase intention |

|

|

.863 |

|

I will buy the fashion item again. |

3.48 |

.773 |

|

|

I have a strong likelihood of buying the fashion item again. |

3.50 |

.832 |

|

|

Notes: λ = factor loading and α = Cronbach alpha |

|

|

|

Source: Authors’ contribution

The hypotheses were tested by OLS, and Baron and Kenny (1986) procedures were used to examine the moderator hypotheses. The OLS regression analyses found that CE was positive and significantly affected brand image (β = .479 p = .000) and brand trust (β = .412 p = .000). This means that CE is a crucial factor in establishing strong branding. In today’s society, personal image is more important than ever. Thus, there is a strong attempt by people to maintain or improve their image in order to continue group membership and to gain validation from their social network. A failure to maintain this image leads to undesirable perceptions, negative judgments and wider personal spaces (Zorrilla, 2014) amongst the public, which further generates barriers and difficulties (Leung, 2014). Opinion leader theory suggests that in order to improve his/her personal image, a customer tends to look up to a celebrity, and this includes how the celebrity dresses. A customer believes that a celebrity wears a certain brand of fashion to support his/her image. Accordingly, when a customer wants to improve his/her self-image, he/she may choose to wear a similar brand to a celebrity, which automatically increases the image of the brand. It was also found that CE helps in building higher brand trust. The commitment of a celebrity to wear his/her endorsed brand shows that the celebrity genuinely believes in the brand, and witnessing this behavior is likely to develop stronger brand trust. It is important, then, that a celebrity shows commitment to his/her endorsed brand. As also predicted, CE was found to be responsible for higher purchase intention (β = .206 p = .013). One possible reason for this finding could be that a customer finds meaning and experiences a positive feeling by owning a celebrity endorsed brand product. For example, a customer who wears a celebrity endorsed fashion brand is viewed as a fashionable person – someone who is both “cool” and proud. Researchers such as Um and Kim (2016) also found this relationship to be significant. Thus, H1, H2 and H3 were supported.

This study also confirms that a strong brand image leads to stronger brand trust (β = .228 p = .000) and purchase intention (β = .410 p = .000). As Keller (1993) explains, brand image serves as a customer barometer to differentiate brands based on their uniqueness, strengths and favorability. That is, when a customer perceives a brand as exclusive, good quality and associated with tangible and intangible benefits (e.g., associated with his/her idolized celebrity), he/she views the brand as trustworthy. Thus, these three positive perceptions tend to reduce a customer’s sense of risk, eventually leading to higher brand trust. This study complements the study of Ke et al. (2016), who also found that brand image improves purchase intention. A positive brand image develops a favorable response from a customer based on his/her higher self-image. That is, when a customer wears a branded fashion product, he/she feels good and perceives himself/herself as having a higher status, leading to an increase in his/her future purchase intention. The findings of this study parallel those of Aghekyan-Simonian et al. (2012), whose study also examined the effect of brand image on purchase intention in the context of the online fashion environment and confirmed that brand trust improves purchase intention. That is, the more trustworthy the brand, the higher the purchase intention. Therefore, H4 and H5 were also supported.

The regression results also show that a strong brand trust is responsible for purchase intention (β = .554 p = .000). Stronger brand trust is likely to lead to a customer’s confidence in a brand’s attributes and qualities and his/her perception of the brand as reliable thus providing the customer with cognitive and affective peace of mind. Because of this positive experience, customers tend to maintain their business relationship with the brand (Sherriff & Yip, 2008) by showing their public commitment through spreading positive word of mouth (Chen et al., 2011) and increasing their repurchase intention. The findings lend support to the studies of Borzooei and Asgari (2013), who also found that brand trust increases purchase intention. Therefore, H6 was also supported.

Finally, the present study also confirmed the moderating effect of CE. The findings showed that CE affects the relationship between brand image and trust (β = .191 p = .000) as well as the relationship between brand image and purchase intention. This means that CE is responsible for determining how strongly brand image affects brand trust and purchase intention (β = .191 p = .000). The rationale behind these findings can be explained by Plummer’s (1985) brand personality theory. According to Plummer (1985), each brand has a different personality. That is, a brand has emotional characteristics that make it unique and allow it to connect to its customers. However, identifying a brand’s personality is challenging, and it is possible that a customer will fail to understand the brand’s image and therefore develop less attachment to the brand. CE of a brand is likely to help a customer identify with a brand’s image as the characteristics and image of the celebrity transfer to the brand, making it easier for the customer to identify with the brand. Thus, when a customer thinks about a brand, he/she is likely to think about the celebrity who endorses it and vice versa. Because of this, CE plays a crucial role in creating a strong brand image, which further leads to brand trust and purchase intention. Accordingly, it is crucial for fashion brands to employ celebrities who display similar characteristics to the fashion brand. The findings support the studies of Dib and Johnson (2019), who also found that CE has moderating effects in different contexts. Thus, H7 and H8 were accepted. Table 2 presents an overview of the hypotheses results.

Table 2. Summary of the Hypotheses Testing

|

Hypotheses |

F |

R2 |

β |

P |

Results |

|

|

H1 |

Celebrity endorsement à Brand image |

39.132 |

.152 |

.479 |

0.000*** |

Supported |

|

H2 |

Celebrity endorsement à Brand trust |

69.413 |

.389 |

.412 |

0.000*** |

Supported |

|

H3 |

Celebrity endorsement à Purchase intention |

74.044 |

.507 |

.206 |

0.013* |

Supported |

|

H4 |

Brand image à Brand trust |

69.413 |

.389 |

.228 |

0.000*** |

Supported |

|

H5 |

Brand image à Purchase intention |

74.044 |

.507 |

.410 |

0.000*** |

Supported |

|

H6 |

Brand trust à Purchase intention |

74.044 |

.507 |

.554 |

0.000*** |

Supported |

|

H7 |

BImageXCeleb à Brand trust |

61.400 |

.361 |

.191 |

0.000*** |

Supported |

|

H8 |

BImageXCeleb à Purchase intention |

78.216 |

.419 |

.191 |

0.000*** |

Supported |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

Source: Authors’ own research

Conclusion

The findings of this study offer an important additional insight into the CE phenomenon. The present model conceptualized CE as directly affecting brand image, brand trust and purchase intention. The study hypothesized that CE moderates the relationship between brand image and brand trust as well as between brand image and purchase intention. This model also hypothesized that brand image is responsible for brand trust and purchase intention. The statistical analyses confirmed all these hypotheses drawn from the proposed model. The findings show the importance of CE in building a stronger brand and increasing purchase intention. The authors believe that the findings of this study enrich CE studies and fill the gap in the academic literature by incorporating into one model the moderating effect of CE on branded products and the impact of brand image, brand trust and CE on purchase intention.

Implications and future research directions

The findings offer the fashion industry and scholars some important information to consider. For fashion industry managers, this study shows the importance of employing celebrities to endorse their brands. At the same time, to avoid the risk of reverse image, managers are recommended to think carefully about which celebrities are suitable to represent their brands. For scholars, the findings of this study enhance understanding of the moderating effect of CE. Very few prior studies have focused on the moderating role of CE. This research specifically identified the moderating effect of CE on two brand components – brand image and brand trust – and on purchase intention.

Although this research was designed and conducted carefully, several limitations existed and should be noted for future research. First, the data was solely collected through the online survey. According to Zong and Vowles (2013), an online survey experiences bias issues. That is, online survey accuracy depends on the participant’s subjective understanding of questions listed in the online survey and thus a participant’s answer may be not completely accurate and not represent reality. Hence, future research may replicate this study by employing a paper and pencil type of survey. Second, the context of this study was limited to fashion brands. The extension of this study to different contexts, such as services (e.g., hotel, airlines or restaurants), may provide a different picture of CE. Third, this study focused on four female celebrities only; therefore, the results may be biased toward females. Future researchers are recommended to include male celebrities in their investigations. Finally, the present model only tested a few constructs and may not provide a complete picture of the phenomenon. Therefore, future research could incorporate other constructs such as brand personality, brand experience and brand enthusiasm, as well as celebrities’ nationality as a potential moderator.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building Strong Brand. New York: The Free Press.

Aghekyan-Simonian, M., Forsythe, S., Kwon, W.S., &Chattaraman, V. (2012).The role of product brand image and online store image on perceived risks and online purchase intentions for apparel. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19, 325–331.

Albert, N., Ambroise, L., & Valette-Florence, P. (2017).Consumer, brand, celebrity: Which congruency produces effective celebrity endorsements? Journal of Business Research, 81, 96–106.

Alfanda, R., Ma’ruf, J.J., Darsono, N., & Chan, S. (2018). Celebrity endorsement as moderating variable on the relationship between loyalty and corporate credibility of travel companies in Aceh. International Journal of Contemporary Research and Review, 9(4), 20726–20734.

Alhaddad, A. (2015). Perceived quality, brand image and brand trust as determinants of brand loyalty. Journal of Research in Business and Management, 3(4), 1–8.

Al-Maghrabi, T., Dennis, C., Halliday, S.V., & BinAli, A. (2011). Determinants of Customer Continuance Intention of Online Shopping. International Journal of Business Science & Applied Management, 6(1), 41–66.

Arsena, A., Silvera, D., & Pandelaere, M. (2014). Brand trait transference: When celebrity endorsers acquire brand personality traits. Journal of Business Research, 67 (7), 1537–1543.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2004). Questions raised by a reasoned action approach: Comments on Ogden (2003). Health Psychology, 23(4), 531–434.

Baron, R.M., & Kenny, D.A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinctions in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical consideration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bednall, D.H.B., & Collings, A. (2000). Effect of public disgrace on celebrity endorser value. Australasian Marketing Journal, 8(2), 47–57.

Beritasatu (2019). Indonesia Completes Palapa Ring Internet Superhighway. Available at https://jakartaglobe.id/tech/indonesia-completes-palapa-ring-internet-superhighway. (Accessed 18 December 2019).

Black, N. (2009) The six drivers trust from Nick Black. Available at http://www.nickblack.org/2009/09/brand-trust-six-drivers-of-trust.html. (Accessed 5 July 2019).

Borzooei, M., & Asgari, M. (2013). The Halal brand personality and its effect on purchase intention). Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 5(3), 481–491.

Chan, K., Ng, Y.L., & Luk, E.K. (2013). Impact of celebrity endorsement in advertising on brand image among Chinese adolescents. Young Consumers, 14 (2), 167–179.

Chao, E., Fiore, A., & Belk, D.W. (2015). Validation of a fashion brand image scale capturing cognitive, sensory and affective associations: Testing its role in an extended brand equity model. Psychology & Marketing, 32 (1), 28–48.

Charbonneau, J., & Garland, R. (2010). Product effects on endorser image: The potential for reverse image transfer. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 22(1), 101–110.

Chauhan, N. M. (2013). Consumer Behavior and His Decision of Purchase. Management and Pharmacy, 2(5), 1–4.

Chen, Y., Fay, S., & Wang, Q. (2011). The Role of Marketing in Social Media: How Online Consumer Reviews Evolve. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 25(2), 85–94.

Chin, V.V., Choy, T.Y., & Pang, L.F. (2017). The effect of celebrity endorsement on brand attitude and purchase intention. Journal of Global Business and Social Entrepreneurship, 1(4), 141–150.

Cunningham, N., & Bright, L. (2012). The Power of A Tweet: An Exploratory Study Measuring the Female Perception of Celebrity Endorsement on Twitter. 2012 AMA Educators’ Proceedings, 416–423.

Danniswara, R., Sandhyaduhita, P. I., & Munajat, Q. (2017). The impact of EWOM referral, celebrity endorsement, and information quality on purchase decision: A case of Instagram. Information Resources Management Journal, 30(2), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.4018/IRMJ.2017040102

Datareportal (2019). Digital 2019 Spotlight: Ecommerce in Indonesia, Available at https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2019-ecommerce-in-indonesia. (Accessed 18 December 2019).

De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram Influencers: The Impact of Number of Followers and Product Divergence on Brand Attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828.

Delgado-Ballester, E., & Manuera-Aleman, J. L. (2000). Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 36(11/12), 1238–1258.

Diallo, M.F. (2012). Effects of Store Image and Store Brand Price Image on Store Brand Purchase Intention: Application to an Emerging Market. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19 (3), 360–367.

Dib, H., & Johnson, L.W. (2019). Gay male consumers seeking identity in luxury consumption: The self-concept. International Journal of Business Marketing and Management, 4(2), 25–39.

Djafarova, E., & Rushworth, C. (2017). Exploring the Credibility of Online Celebrities’ Instagram Profiles in Influencing the Purchase Decisions of Young Female Users. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 1–7.

Erdogan, B.Z., Baker, M.J., & Tagg, S. (2001). Selecting celebrity endorsers: The practitioner’s perspective. Journal of Advertising Research, 41(3), 39–48.

Escalas, J.E., & Bettman, J.R. (2015). Managing brand meaning through celebrity endorsement. Brand Meaning Management, 12, 29–52.

Esch, F.R., Langer, T., Schmitt, B.H., & Geus, P. (2006). Are brands forever? How brand knowledge and relationship affect current and future purchases. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 15(2), 98–105.

Fong, L.S., & Yazdanifard, R. (2014). Celebrity Endorsement as a Marketing Tool. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 14(4),1–4.

Forouhandeh, B., Nejatian, H., Ramanathan, K., & Forouhandeh, B. (2011). Determining advertisement’s efficiency: Celebrity endorsement versus non-celebrity models. Paper presented at 2nd International Conference on Business and Economic Research (2nd ICBER 2011), Lankawi, Malaysia.

Gong, W., & Li, X. (2017). Engaging Fans on Microblog: The Synthetic Influence of Parasocial Interaction and Source Characteristics on Celebrity Endorsement. Psychology & Marketing, 34, 720–732.

Greenhouse (2019). Indonesia’s Social Media Landscape: An Overview. Available at https://greenhouse.co/blog/indonesias-social-media-landscape-an-overview/. (Accessed 18 December 2019).

Hahn, K.H., & Kim, J. (2009). The effect of offline brand trust and perceived internet confidence on online shopping intention in the integrated multi-channel context. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 37(2), 126–141.

Hakimi, B.Y., Abedniya, A., & Zaeim, M.N. (2011). Investigate the impact of celebrity endorsement on brand images. European Journal of Scientific Research, 58(1), 116–132.

Harridge-March, S. (2006). Can the building of trust overcome consumer perceived risk online? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 24(7), 746–761.

Hegner, S. M., & Jevons, C. (2016). Brand trust: A cross national validation in Germany, India, and South Africa. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(1), 58–68.

Hsieh, M.H., & Lindridge, A. (2015). Product-, Corporate- and Country Image Dimensions and Purchase Behavior: A Multicountry Analysis. Academy of Marketing Science, 32 (3), 251–270.

Indonesia Investments (2019). Number of Internet Users in Indonesia Rises to 171 Million. Available at https://www.indonesia-investments.com/news/todays-headlines/number-of-internet-users-in-indonesia-rises-to-171-million/item9144. (Accessed 18 December 2019).

Ipsos (2018). Instagram’s Impact on Indonesian Businesses. Available at https://www.ipsos.com/en/instagrams-impact-indonesian-businesses. (Accessed 18 December 2019).

Jin, S.A.A., & Phua, J. (2014). Following Celebrities’ Tweets about Brands: The Impact of Twitter based Electronic Word of Mouth on Consumers’ Source Credibility Perception, Buying Intention and Social Identification with Celebrities. Journal of Advertising, 43(2), 181–195.

Karasiewicz, G., & Kowalczuk, M. (2014). Effect of celebrity endorsement in advertising activities by product type. International Journal of Management and Economics, 44, 74–91.

Ke, D., Chen, A., & Su, C. (2016). Online trust building mechanisms for existing brands: The moderating role of the e-business platform certification system. Electronic Consumer Research, 16, 189–216.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring and managing customer based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22.

Khasawneh, K., & Hasouneh, A.B.I. (2010). The effect of familiar brand names on consumer behavior: A Jordanian perspective. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 43, 34–57.

Kim, H., Hur, W.M., & Yeo, J. (2015). Corporate brand trust as a mediator in the relationship between consumer perception of CSR, corporate hypocrisy, and corporate reputation. Sustainability, 7(4), 3683–3694.

Laila, R., & Sjabadhyni, B. (2017). The influence of celebrity endorsement types and congruency celebrity with the body care products on Instagram users’ intention to purchase. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 139, 190–196.

Laroche, M., Habibi, M.R., Richard, M.O., & Sankaranarayanan, R. (2015). The effect of social media-based brand communities on brand community markers, value creation practices, brand trust and brand loyalty. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1755–1767.

Leung, K. (2014). Globalization of Chinese firms: What happens to culture?” Management and Organization Review, 10(3), 391–397.

Liao, S.H., Chung, Y.C., & Widowati, R. (2009). The relationships among brand image, brand trust, and online word of mouth: An example of online gaming. Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE IEEM, 2207–2211, Hong Kong.

Lin, L. Y., & Lu, C. Y. (2010). The Influence of Corporate Image, Relationship Marketing and Trust on Purchase Intention: The Moderating Effects of Word of Mouth. Tourism Review, 65(3), 16–34.

Makasi, A., Govender, K., & Madzorera, N. (2014). Re-branding and its effects on consumer perceptions: A case study of a Zimbabwean bank. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 2582–2588.

Malik, M. E., Ghafoor, M.M., & Iqbal, H.K. (2012). Impact of brand image, service quality and price on customer satisfaction in Pakistan telecommunication sector. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(23), 123–129.

Maroko, L., & Uncles, M.D. (2008). Characteristics of successful employer brands. Journal of Brand Management, 16(3), 160–175.

McGorry, S. Y. (2000). Measurement in a cross-cultural environment: Survey translation issues. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 3, 74–81.

Merz, M. A., He, Y., & Vargo, S.L. (2009). The evolving brand logic: A service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of the Academic Marketing Science, 37, 328–344.

Moatti, V., & Abecassis-Moedas, C. (2018). How Instagram became the Natural Showcase for the Fashion World. Available at https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/fashion/features/instagram-fashion-industry-digital-technology-a8412156.html. (Accessed 19 December 2019).

Moon, J., Chadee, D., & Tikoo, S. (2008). Culture, Product Type, and Price Influences on Consumer Purchase Intention to Buy Personalized Product Online. Journal of Business Research, 61, 31–39.

Mowen, J., & Minor, M. (2000). Consumer behavior – A framework. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Nandan, S. (2005). An exploration of the brand identity – brand image linkage. A communication perspective. Journal of Brand Management, 12(4), 264–278.

Ohanian, R. (1990). Constructions and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52.

Napoleon (2020). Instagram Users in Indonesia. Available at https://napoleoncat.com/stats/instagram-users-in-indonesia/2018/12

Omar, M., & Williams, R.L. (2006). Managing and maintaining corporate reputation and brand identity: Haier group logo. Journal of Brand Management, 13(4/5), 268–275.

Phua, J., Syuan, J., & Lim, D. J. (2018). Understanding Consumer Engagement with Celebrity Endorsed E-Cigarette Advertising on Instagram. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 93–102.

Plummer, J.T. (1985). How personality makes a difference? Journal of Advertising Research, 24(6), 27–31.

Porral, C.C., & Lang, M.F. (2015). Private labels: The role of manufacturer identification, brand loyalty and image on purchase intention. British Food Journal, 117(2), 506–522.

Pribadi, A. P., Adiwijaya, M., & Herjanto, H. (2019). The effect of brand trilogy on cosmetic brand loyalty. International Journal of Business Society, 20(2), 730–742.

Punyatoya, P. (2014). Linking environmental awareness and perceived brand eco-friendliness to brand trust and purchase intention. Global Business Review, 15(2), 279–289.

Rahimnia, F., & Hassanzadeh, J.F. (2013). The impact of website content dimension and e-trust on e-marketing effectiveness: The case of Iranian commercial saffron corporation. Information & Management, 50, 240–247.

Sagar, M., Khandelwal, R., Mittal, A., & Singh, D. (2011). Ethical Positioning Index (EPI): An innovative tool for differential brand positioning. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 16(2), 124–138.

Seno, D., & Lukas, B.A. (2017). The equity effect of product endorsement by celebrities. European Journal of Marketing, 41(1/2), 21–134.

Sherriff, L. T. K., & Yip. L. S. (2008). The Moderator Effect of Monetary Sales Promotion on the Relationship between Brand Trust and Purchase Behavior. Journal of Brand Management, 15(6), 452–464.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J.C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W.G. Austin, and S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey: Books-Cole.

Tantiseneepong, N., Gorton, M., & White, J., (2012). Evaluating responses to celebrity endorsements using projective techniques. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 15(1), 57–69.

Tariq, M. I., Nawaz, M.R., Nawaz, M.M., & Butt, H.A. (2013). Customer perceptions about branding and purchase intention: A study of FMCG in an emerging market. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 3(2), 340–347.

Thanh, T. H. H. (2016). The Impacts of Celebrity Endorsement in Ads on Consumer Purchasing Intention: A Case of Facebook. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research, 5(8), 25–27.

Totoatmojo, K.M. (2015). The Celebrity Endorser (Selebgram) Effect toward Purchase Intention on Instagram Social Media. Paper presented at 3rd ASEAN academic Society International Conference, Bangkok, Thailand.

Tseng, L. Y., & Lee, T. S. (2013). Investigating the Factors Influence Tweens’ Purchase Intention through Peer Conformity in Taiwan. Advances in Management & Applied Economics, 3(3), 259–277.

Um, N. H. (2013). Celebrity scandal fallout: How attribution style can protect the sponsor. Psychology & Marketing, 30(6), 529–541.

Um, N. H., & Kim, S. (2016). Determinants for effects of celebrity negative information: When to terminate a relationship with a celebrity endorser in trouble? Psychology & Marketing, 33(10), 121–134.

Wahloonluck, R., & Chokesamritpol, K. (2013). The Use of Celebrity Endorsement with the Help of Electronic Communication Channel (Instagram). Unpublished Master thesis, Available at http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:626251/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Wang, X., & Yang, Z. (2010). The Effect of Brand Credibility on Consumers’ Brand Purchase Intention in Emerging Economies: The Moderating Role of Brand Awareness and Brand Image. Journal of Global Marketing, 23(3), 177–188.

Wang, Y. D., & Emurian, H.H. (2005). An overview of online trust: Concepts, elements and implications. Computers in Human Behavior, 21(1), 105–125.

Wijaya, B. S. (2013). Dimensions of brand image: A conceptual review from the perspective of brand communication. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(31), 55–65.

Wu, P.C.S., Yeh, G.Y.Y., & Hsiao, C.R. (2011). The effect of store image and service quality on brand image and purchase intention for private label brands. Australasian Marketing Journal, 19, 30–39.

Wymer, W. (2013). Deconstructing the brand nomological network. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 10(1),1–12.

Xie, L.S., Peng, J.M., & Huan, T.C. (2014). Crafting and testing a central precept in service-dominant logic: Hotel employees’ brand citizenship behavior and customers’ brand trust. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 42, 1–8.

Zamudio, C. (2016). Matching with the stars: How brand personality determines celebrity endorsement contract formation. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 33, 409–427.

Zorrilla, A. (2014). Adult education for critical consciousness: Luis Camnitzer and his art as critical public pedagogy. Paper presented at Adult Education Research Conference, Harrisburg, PA.