Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2019, vol. 10, no. 2(20), pp. 212–226 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2019.10.11

Influence of Religiosity on the Behavior of Buying Sports Apparel: A Study of the Muslim Market Segment in India

Hasnan Baber

Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University,

Jayang-Dong, Dong-gu, Daejeon, South Korea

Email: h.baber@endicott.ac.kr

Abstract. The paper is aimed to study the influence of religiosity on the behavior of buying sports apparel in the Muslim market segment of India. The data was collected from 1000 Muslim respondents from four states: Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Uttarakhand, and Jammu & Kashmir. The paper has found that religion plays no role when Muslims buy sports apparel. They shop as any other religious person does. No other factor, even fashion and religious obligation, is influenced by religion, except for shopping enjoyment responsiveness, which is influenced by intrapersonal Islamic religiosity. The paper’s perspective in studying the religious influences will assist sporting apparel manufacturers to design new products that will meet the requirements of the large Muslim segment in India, which is neglected so far. It will help marketers to save their effort and energy which would be utilized for Muslim Population.

Keywords: Islam, religion, buying behavior, sports apparel, India

Received: 12/6/2018. Accepted: 8/2/2019

Copyright © 2019 Hasnan Baber. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

After Globalization, international sports companies are always on the hunt to tap new markets. This effort to enter overseas markets is to achieve numerous goals such as increasing brand awareness all across the world, increasing products sales, and successively gain more revenues (Luna & Gupta, 2001). The best lucrative arcades for global marketers are those regions which have a large population, teenage groups, and high income, characters that are all present in the Indian population (Salzman, 2008). Puma, Reebok, Adidas, and Nike are the major sellers of athletic apparel worldwide (Andreff, 2009).

Religion is a non-figurative notion. Religion symbolizes an amalgamated system of practices and beliefs in relation with the holy things, “while religiosity is viewed as the degree to which beliefs in specific religious values and ideal are held and practiced by an individual” (Delener, 1990). Some studies on buying behavior (Ilyas et al., 2011), explicit advertisement (Run et al., 2010; Sabri, 2012), product involvement (Yousaf & Malik, 2013), halal cosmetics and labelling (Jamal & Sharifuddin, 2015), shopping enjoyment (Mokhlis, 2009), and consumer satisfaction (Eid & El-Gohary, 2015) found a positive relationship of religiosity with these marketing areas.

Religions everywhere in the world are understood to have a certain set of laws that impact ritually and emblematically consumer behavior: from work to play, from dawn to dusk purchases and behaviors. Religion, here, denotes not only something which is supernatural, but here it is binding of beliefs. Average or high-level religiosity does not do or permit anything which is against such religious beliefs.

Muslims demand for Islamic products reveals an innovative prospect in the contemporary international marketplace. An approach which marketers design for the regular market will bring numerous intimidations if such approaches are not brought into line with Sharia laws in order to be used in Islamic Market place (Morphitou & Gibbs, 2008). In the words of Hassan et al. (2008), “The Islamic marketing values combine the value-maximization theory through the faith of uprightness for the wider welfare of the humankind”.

In today’s world, sport is becoming a worldwide sensation. The volume of folks involved in sports, either as players or as an audience, is amassed, and thus sport-related consumption has augmented accordingly (Lera-Lopez & Rapun-Garate, 2007). Watson and Parker (2013) stated that despite the fact that sport and religion have been clearly related with each other for over 3000 years, the numerous studies are secular in nature and tend to keep sports out of religious context. Some authors studied the factors which have an impact on the consumption of sport-related goods, such as sex, race, income, age, socio-culture and sports involvement (Mirzazadeh, 2017; Abdolmaleki, 2016; Pan & Gabert, 1997; Taks & Mason, 2004; Armstrong & Stratta, 2004). Nevertheless, the impact of religion, and Islam in particular in my awareness, has not yet been researched in the context of sports apparel buying behavior in India.

The objective of the study is to explore the influence of religiosity in Islam on the buying behavior of Muslims while buying sports apparel. Currently, big brands like Zara are targeting the niche segment of Muslim women who prefer to wear branded clothes, yet according to the ruling of Islamic law. The study will be helpful to the sport apparel brands to understand the behavior of Muslims in purchasing sports apparel. Indian Muslim market is huge, so it will be important for apparel brands to design the clothes as per the requirements of this segment.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Religiosity vs. buying behavior

Muslim market is not homogenous inside, the level of commitment towards Islam, i.e. religiosity, varies within Muslim segment, and therefore, has varying influence on the buying decision of Muslims (Essoo & Dibb, 2004). Muslims who are highly committed towards Islam will always tend to follow the Sharia (Islamic laws and rules) more strictly than those Muslims who do not follow sharia with high religiosity (Mokhlis, 2006). The former group will buy clothes in general and sports apparel in particular which stringently match Islamic ruling. As in Islam women are asked to wear clothes which will cover their physique completely, only face and hands can be revealed, while men are supposed to nominally hide their skin from the navel to the knee (Khan, 2003). Islam strictly rules about the design of clothes which need to be not so tight that they will reveal the shape of body or body parts, clothes should be neat and decent (About.com: Islam, 2009). Muslims residing in non-Muslim countries (e.g., an Indian Muslim living in the US) tend to have more variation in the level of religiosity, and that has again impact on their buying behavior (Salzman, 2008).

Gayatri et al. (2005) in their study on Muslim consumers and service quality of restaurant, hotel, and airlines business revealed that religiosity has an influence on the lifestyle, risk appetite in purchasing, attitude towards advertisement and purchasing behavior of some durable and selected retail products. Wilkes et al. (1986) have come to the conclusion that when gender, income, and age are constant, people with high religiosity level have a reputation of good opinion holder and are believed to buy products according to the religious laws. Various studies have found a relationship between religion and buying behavior (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, 2002; Schneider et al., 2011; Al-Hyari et al., 2012; Mukhtar & Butt, 2012; Kassim & Zain, 2016; Dekhil et al., 2017; Baber, 2019), and Islam in particular (Razzaque & Chaudhry, 2013; Yousaf & Malik, 2013).

2.2 Islam vs. Sport

Islam stresses the importance of sports to maintain a good physique and to be powerful and capable of resisting enemies, diseases and upholding the safety of homeland. It is recommended in Islam to train young people for sports like shooting, swimming, etc. Prophet Mohammad (ﷺ) said “Teach thy children shooting and train them on horsemanship till they excel”, and only these sports were known at that time, so all sports are allowed until specifically prohibited (Khan, 2003).

In Islam, women are also allowed to participate in sports. It was reported that Prophet Mohammad (ﷺ) used to race with his wife “Aisha” and once she beat him in the race. And in another race the prophet outran her, whereupon he said: “This time makes up for the other.” There is no specific ruling about sports apparel in Islam so the same requirements for clothes also apply here.

2.3 Muslim Market segment in India

According to the census data 2011, Indian population comprises various religions, and 14 % of the population is Muslim; 11% of the Muslim population of the world lives in India, which is the third highest proportion after Indonesia and Pakistan. Though India is a Hindu majority country, some states have Muslim majority, e.g., Jammu and Kashmir. Table 1 presents the data on the four Indian states selected for this study.

Table 1. Statewise religion statistics

|

State |

Majority Religion |

Hindu (Percentage of the population) |

Muslim (Percentage of the population) |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

Hindu |

79.73 |

19.26 |

|

Jammu and Kashmir |

Muslim |

28.44 |

68.31 |

|

Uttara khand |

Hindu |

82.97 |

13.95 |

|

Delhi |

Hindu |

81.68 |

12.86 |

* Figures are copied from the official website of census 2011 (http://www.census2011.co.in).

3. Methods

3.1 Conceptual Framework

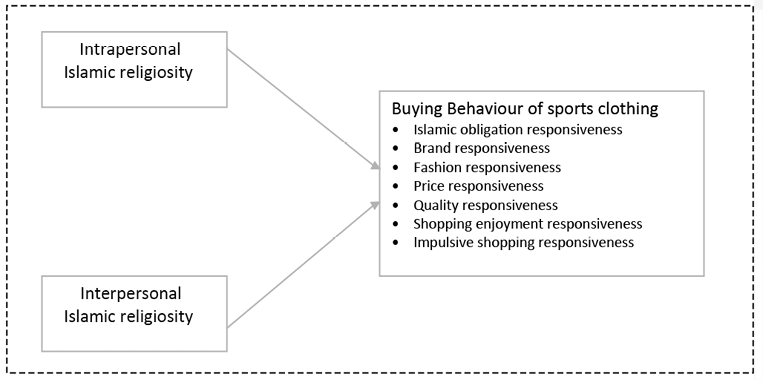

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of the Study

Mokhlis (2006) and Taks and Shreim (2009) studied shopping for clothes behavior and proposed six variables which can impact the purchasing behavior of consumers with regard to clothes. The same model will be applied in understanding the sports clothes shopping behavior of Muslim consumers. Mokhlis (2006) proposed six responsiveness variables which shape the consumer behavior towards buying clothes, which are: price, fashion, quality, brand, shopping enjoyment, and impulsive shopping responsiveness. Islamic obligation perception will be added to the model to make it relevant to Muslim consumers. Lindridge (2005) revealed that Islamic religion has the influence on societal and personal life of Muslims, so the role of Islam is deep in Muslim’s life including buying behavior. This study will take Islamic religiosity, which is further divided into intrapersonal and interpersonal religiosity commitment as an independent variable and seven responsiveness aspects as dependent variables as shown in Figure 1.

4. Measurements

Islamic Religiosity (IR): Muslims do not show the same level of religiosity towards Islam. Some Muslims follow religion strictly in their life, while others are not so religious (Youssef et al., 2011). Religious Commitment Inventory (RCI-10) proposed by Worthington et al. (2003) is employed in this study to measure Islamic religiosity. The RCI-10 measures intrapersonal religiosity, which focuses on a personal devotion towards religion, and interpersonal religiosity, which measures the involvement of a person in religious communities and affairs, as shown in Table 2. A 5-point Likert scale is used to measure the response of the sample, where “1 = strongly disagree” and “5 = strongly agree”.

Table 2. Constructs of the Religious Commitment Inventory

|

Intrapersonal Islamic religiosity (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.76) |

|

• I follow Islam strictly in my life. • I always spend time in prayers and in other religious activities. • My whole life is directed according to Islamic laws and rules. • My all dealings in life are influenced by Islam. • I learn Islam continuously from religious bodies to grow my understanding better about Islam. • I spend time reading the Quran and Hadiths books to get a clear understanding of religion. H1: Intrapersonal Islamic religiosity has a positive influence on the sports clothing buying behavior of Muslim consumers. |

|

Interpersonal Islamic religiosity (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.74) |

|

• I usually make friends in my religion, and we discuss Islam with each other. • I always take part in Islamic seminars and conferences. • I give charity and help the poor as it is directed in Islam. • I always try to utilize my time for religious activities and discussion with Muslims. H2: Interpersonal Islamic religiosity has a positive influence on the sports clothing buying behavior of Muslim consumers. |

Reliability test was done to check the internal consistency of the data. Cronbach’s Alpha for both factors - Intrapersonal and interpersonal religiosity - was more than 0.7, at 0.76 and 0.74 respectively for this sample, which is standard (Cronbach, 1951). To measure the internal reliability of data, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for all factors in Table 3. In impulsive shopping responsiveness, the value of alpha was 0.58 (less than 0.70). The statement “I buy sports clothing without thinking much” was excluded from impulsive shopping responsiveness construct to increase the internal consistency of the construct.

Table 3. Interreliability of Shopping for Sports Clothing Behaviour Responsiveness

|

Sports clothing shopping behavior responsiveness |

|

Price responsiveness (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.77) |

|

I always check for discounts and sale on clothes. I keep track of advertisements showing discounts on sport clothes. I bargain with the seller whenever I purchase sports clothes. |

|

Quality responsiveness (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.88) |

|

I am quality conscious and can pay any price to get good quality. I am generally more concerned to pay more for quality sport clothing. Quality of sports clothes is essential compared with normal clothes. |

|

Brand responsiveness (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.89) |

|

Branded sports clothing increases my status and ego. I always look for brand whenever I purchase any sport clothing. I like to wear branded accessories and show off. I always try to find the best brand while buying sport clothing. |

|

Fashion responsiveness (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.86) |

|

I usually buy fashionable and trendy sport clothes. I keep track of changing fashion in sport clothes. It is important to have the latest fashionable sport clothes. I consider myself to be fashionable with regard to my sport clothing. |

|

Shopping Enjoyment responsiveness (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.78) |

|

I enjoy buying sport clothes. I like to go shopping when I have to purchase sport clothes. I usually go to other shops even after the purchase of sport clothing. |

|

Impulsive Shopping responsiveness (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.75) |

|

I often make a decision about what to buy in a shop and sometimes buy things I have not decided on. I often buy clothes which I do not need. I buy sports clothing without thinking much (excluded). |

The nine-item Islamic obligation responsiveness construct was developed from Shreim (2009) as shown in Table 4. Islamic obligation responsiveness follows the Shariah (Islamic law) while buying the sport clothes.

4.1 Factor Analysis for Islamic Obligation Responsiveness

To reduce the factors into a similar construct and to authenticate the model, factor analysis is used. The principal component method is used on the construct Islamic obligation responsiveness with Varimax rotation for this study. Keiser – Meyer – Olkin measure of sampling adequacy test was 0.933, which is greater than 0.5 standard value (Leech et al., 2013), and Barlett’s test of sphericity value was significant as the value was less than 0.05 (Field, 2001).

All the factors were retained as eigenvalues were greater than 1.0 and also items had rotated factor loadings of 0.40 or greater (Field, 2001). The result of the cumulative variance explained is above 71%, which is acceptable. To check the internal reliability of data, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for all factors of Islamic obligation of sports clothing shopping behavior, which was 0.81, above the standard 0.7 (Churchill, 1979) as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Factor analysis of Islamic Obligation Responsiveness

|

Factor and variables |

Factor loadings |

|

Factor 1: Islamic obligation responsiveness (Eigenvalues: 4.04 & 2.42, variance explained: 71.88%, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.81) |

|

|

I take Islamic laws into consideration while wearing sports clothes. |

0.814 |

|

I take Islamic laws into consideration while buying sports clothes. |

0.903 |

|

Taking Islamic obligation into consideration while wearing sports clothes shows commitment to religion. |

0.644 |

|

I prefer stores that sell sports clothing according to Islamic rulings. |

0.727 |

|

I would like to show my Muslim identity with sports clothing according to Islam. |

0.910 |

|

Islamic obligation holds more importance than the price of clothes. |

0.910 |

|

Islamic obligation holds more importance than the quality of clothes. |

0.932 |

|

Islamic obligation holds more importance than the brand of clothes. |

0.892 |

|

Islamic obligation holds more importance than the fashion of clothes. |

0.892 |

Participation in sport

This variable was taken from Shreim (2009), in which four questions were asked related to sports participation: (a) Sports preference; (b) Time spent in participation; (c) Level of participation, and (d) Sports expenditure.

4.2 Demographic profile

The demographic information of the respondents is shown in Table 5. There were slightly more male respondents (58.8%) than females (41.2%). The age of respondents ranged from 15 to 45 years, where 94.6 % are in the range between 25–45 years, who are usually involved in sports. In terms of marital status: 18% were single, 76% were married, and 4.3% were reluctant in disclosing their marital status. Around 65% of population had the annual household income between 100,000 and 500,000 rupees, while 31.1% earned between 500,000 and 1,000,000 as shown in Table 5. Most of the respondents had a Bachelor’s degree (61%), and 27.5% held Master’s degree. The sample seems to be educated, representing a higher middle-income group, from both genders, mostly young and married.

Table 5. Demographic profile

|

Number of respondents |

% |

|

|

Age |

||

|

15–25 |

54 |

5.4 |

|

25–35 |

434 |

43.4 |

|

35–45 |

512 |

51.2 |

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

588 |

58.8 |

|

Female |

412 |

41.2 |

|

Marital status |

||

|

Single |

188 |

18.8 |

|

Married |

769 |

76.9 |

|

Unstated |

43 |

4.3 |

|

Income |

||

|

Below 100,000 |

19 |

1.9 |

|

100,000–500,000 |

653 |

65.3 |

|

500,000–1,000,000 |

311 |

31.1 |

|

Above 1,000,000 |

17 |

1.7 |

|

Education level |

||

|

High School |

36 |

3.6 |

|

Bachelor’s Degree |

617 |

61.7 |

|

Master’s Degree |

275 |

27.5 |

|

Ph.D. |

65 |

6.5 |

|

Others |

7 |

.7 |

|

Total number of respondents |

1000 |

100 |

With respect to sports participation, 49% of respondents were involved in Cricket, 30% in running/walking and the rest in hockey, football and other sports. 51% of the sample spent 5–10 hrs on sport, 25% dedicated 2–5 hrs and 20% spent more than 10 hrs a week on sport. 47% were involved in a sport mostly for competition and some recreational activities, and 35% were purely participating in competitions. More than half of the sample, 54%, spent between 5,000–10,000 rupees on sport per year, whereas 24% spent more than 10,000 Rs, and 15% spent between 1k–5k Rs on sports apparel per year. From these statistics, we see that we had the sample who were actively participating in competitive sport and spent a good amount of their income on sports apparel.

5. Analysis

5.1 Measurement Model Analysis

There are seven dependent latent variables in this study: Price Responsiveness, Brand Responsiveness, Quality Responsiveness, Fashion Responsiveness, Impulsive Shopping Responsiveness, Shopping Enjoyment Responsiveness, and Islamic Obligation Responsiveness. Likewise, the study uses two independent variables: intra Islamic religiosity and inter Islamic religiosity. In order to examine the relative contribution to all the dependent variables by intra and inter Islamic religiosity, path analysis using Generalised Least Square (GLS) approach was employed. Data was analyzed using the AMOS Structural Equation Modelling Software. Amidst a number of model fit indices, Bollen’s (1990) recommendations are followed to examine the model fit. It is possible for a model to be acceptable on one fit index but to be short on many other fit measures (Tzafrir, 2005). The selection of indices was therefore based on the recommendation of Muller (1996), Hu and Bentler (1995) and Tzafrir (2005). They suggested using chi-square statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the normed fit index (NFI), and non-normed fit index (NNFI). Before structurally analyzing the model, measurement model analysis using Anderson and Gebing’s (1998) approach is conducted.

Table 6 shows the values of fit indices obtained for our nine-factor model produced by the AMOS 20 program. As given in the table, the overall chi-square is significant (X2 = 161.75, df = 101, p<.00). The data indicates that the measurement model does not satisfactorily account for the observed co-variation among the latent variables. Nevertheless, this is expected, given that covariance-based SEM models are sensitive to sample sizes (Bagozzi & Yi, 1998). Loehlin (1998) and Bandalos (1996) have noted that a large sample produces statistically significant chi-square, therefore, we accept the index.

Table 6. Goodness of fit results

|

Model |

X2 |

Df |

P |

CFI |

NFI |

NNFI |

RMESA |

|

Measurement Model |

161.75 |

101 |

.00 |

0.988 |

0.961 |

.0989 |

0.07 |

Source: AMOS output

However, NFI, CFI, and NNFI are all well above .90 threshold level which is accepted by almost all the researchers. This is an indication of a good fit (Bandalos, 1996). Additionally, RMESA of .07 suggests that the factor model represents a good approximation. These indices imply that the specification of the measurement model is suitable for testing the structural model. We also examined standardized regression weights and modification indices, which met all the established criteria for the distinctive nature of the model and all the items loaded significantly on one construct only. Therefore it is concluded that the model is well specified and ready to be tested structurally.

The second step of the analysis was to run the path analysis depicting the relationship between all the exogenous and endogenous variables as stated in the hypothesis. The relationship was tested using only one model by introducing both the explanatory variables simultaneously.

5.2 Structural Model Analysis

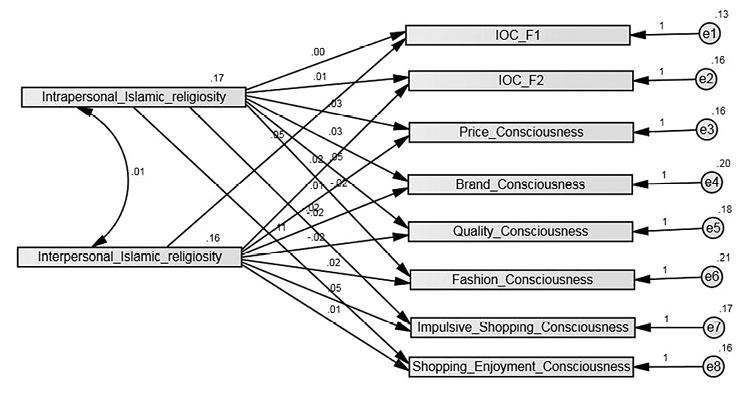

Structural model estimates the beta coefficients of regression paths. Data performed imputation in AMOS and performed structural analysis using observed variables represented by rectangular boxes in the software. The structural model is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Structural Model of the Influence of Religion on the Buying of Sport Apparel Behavior

Examination of unstandardized parameter estimates indicates insignificant hypothesized relationships. Table 7 shows barring from the significant relationship between intrapersonal Islamic religiosity and shopping enjoyment, all the paths have reported insignificant path coefficients with p values >0.01.

Table 7. Structural Model Coefficients

|

Endogenous Constructs |

Exogenous |

Estimate |

S.E. |

C.R. |

P |

|

IOC_F1 |

Intrapersonal Islamic religiosity |

–.005 |

.028 |

–.167 |

.867 |

|

IOC_F2 |

.010 |

.031 |

.308 |

.758 |

|

|

Price Responsiveness |

.031 |

.031 |

.996 |

.319 |

|

|

Brand Responsiveness |

.031 |

.035 |

.905 |

.365 |

|

|

Quality Responsiveness |

.050 |

.033 |

1.516 |

.130 |

|

|

Fashion Responsiveness |

–.015 |

.035 |

–.427 |

.670 |

|

|

Impulsive Shopping Responsiveness |

–.020 |

.032 |

–.614 |

.539 |

|

|

Shopping Enjoyment Responsiveness |

.113 |

.031 |

3.667 |

*** |

|

|

IOC_F1 |

Interpersonal Islamic religiosity |

.053 |

.029 |

1.839 |

.066 |

|

IOC_F2 |

.018 |

.031 |

.587 |

.557 |

|

|

Price Responsiveness |

.013 |

.031 |

.404 |

.686 |

|

|

Brand Responsiveness |

–.025 |

.035 |

–.700 |

.484 |

|

|

Quality Responsiveness |

–.018 |

.033 |

–.547 |

.584 |

|

|

Fashion Responsiveness |

.018 |

.036 |

.494 |

.621 |

|

|

Impulsive Shopping Responsiveness |

.054 |

.033 |

1.635 |

.102 |

|

|

Shopping Enjoyment Responsiveness |

.007 |

.031 |

.210 |

.834 |

AMOS also produces squared multiple correlations (R2) for each dependent variable. It indicates the proportion of variance accounted for by the explanatory variables (Arbuckle & Worthke, 2001). The results are presented in Table 8. The data in the table show that the explained variance of all the variables is insignificant. In other words, there are other variables that explain the variance in endogenous variables. These estimates indicate that Islamic religiosity plays no role in the behavior of buying of sports apparel.

Table 8. Squared Multiple Correlations

|

Constructs |

Estimate |

|

Shopping Enjoyment Responsiveness |

.013 |

|

Impulsive Shopping Responsiveness |

.003 |

|

Fashion Responsiveness |

.000 |

|

Quality Responsiveness |

.002 |

|

Brand Responsiveness |

.001 |

|

Price Responsiveness |

.001 |

|

IOC_F2 |

.000 |

|

IOC_F1 |

.003 |

Statistically, regression models are prone to multicollinearity issues which influence estimates unevenly. Multicollinearity is a statistical phenomenon in which two or more independent variables are highly correlated with each other. Coefficient estimates may change erratically in response to small changes in the model or the data with highly correlated predictors. We estimated the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and Tolerance Values for both the predictors to test multicollinearity. The application of Sánchez and Roldán (2005) and Alsos et al. (2006) criteria showed that the model was not affected by multicollinearity, indicating the model has predicted correct estimates.

6. Results and Conclusion

Both the hypotheses studied in this research have rejected the supposition that religion has any influence on the decision of purchasing sports apparel in Muslim consumers. Hence, it is turned down that behavior of a sports clothing consumer is governed by Islamic religious injunctions in India; maybe in some other Muslim majority country this would be true. The present study also indicates that intrapersonal Islamic religiosity only has influence on shopping enjoyment, which may be explained by the assumption that a person who is more religious does not have anything to enjoy in shopping. This study shows that Muslim consumers are no different from other consumers and they buy sports apparel like those of other religion. The study shows that the level of religiosity has no role to play in buying behavior of Muslim population towards sports clothing.

As a conclusion of this study, the results reveal that the Islam religion has no influence on the purchase decision of Muslim consumers except the fact that a person whose life approach is based on Islam does not enjoy such shopping. This finding has formed a behavior model of Muslim consumers where marketers will now no more treat Muslim sports consumers as different. They are not influenced by religion to buy priced, branded, quality, fashion-oriented clothes and pay no heed to Islamic obligation while purchasing sports clothes. The study also suggests that demographic characteristics have no impact on the buying behavior of Muslims in the case of sports clothing. Marketers who want to penetrate the Indian market should not consider religion as a basis for segmenting market. If Muslim consumers, who are regarded as most conservative among all religions, do not have any influence of religion, then probably all religions will not have any such influence.

The sample states in this study were from the northern area. India has a rich ethnic diversity so Muslims in the north and south region may exhibit a different level of religiosity. The findings are potentially valuable and interesting but they cannot be generalized beyond the sample employed, states studied, product class and religion.

References

About.com: Islam (2009). Beliefs & worship, clothing. Retrieved November 9, 20015, from http://islam.about.com/od/dress/p/clothing_reqs.htm.

Abdolmaleki, H., Mirzazadeh, Z., & Ghahfarokhhi, E. A. (2016). The role played by socio-cultural factors in sports consumer behavior. Annals of Applied Sport Science, 4(3), 17–25.

Al-Hyari, K., Alnsour, M., Al-Weshah, G., & Haffar, M. (2012). Religious beliefs and consumer behaviour: from loyalty to boycotts. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 3(2), 155–174.

Alsos, G. A., Isaksen, E.J., Softing, E. (2006), Youth enterprise experience and business start-up intentions, Paper presented at the 14th Nordic Conference on Small Business Research, Stockholm, May, pp. 11–13.

Andreff, W. (2009). The sports Goods Industry. In W. Andreff & S. Szymanski (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of sport (2nd ed.) (pp. 27–39). Cornwall: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988) Structural Equation Modelling in Practice: A review and Recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–23.

Arbuckle, J. L., & Wothke, W. (2001). AMOS 4.0 User’s Guide. Chicago, IL: Small Waters.

Armstrong, K. L., & Peretto Stratta, T. M. (2004). Market Analyses of Race and Sport Consumption. Sport Marketing Quarterly,13(1).

Baber, H. (2018). Factors Influencing the Intentions of Non-Muslims in India to Accept Islamic Finance as an Alternative Financial System. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, 7, 317–323.

Bagozzi, R., & Yi, Y. (1998). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 77–94.

Bandalos, D. (1996). Confirmatory factor analysis. In J. Stevens (Ed.), Applied Multivariate Statistics for the social science, 3rd ed. (pp. 389–428). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bollen, K.A. (1990). Overall Fit in Covariance Structural Models: Two types of Ample size effects. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 256–9.

Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2002). Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer research, 29(3), 348–370.

Dekhil, F., Boulebech, H., & Bouslama, N. (2017). Effect of religiosity on luxury consumer behavior: the case of the Tunisian Muslim. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 8(1), 74–94.

Delener, N. (1990). The effects of religious factors on perceived risk in durable goods purchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 7(3), 27–38.

Eid, R., & El-Gohary, H. (2015). The role of Islamic religiosity on the relationship between perceived value and tourist satisfaction. Tourism Management, 46, 477–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.003

Essoo, N., & Dibb, S. (2004). Religious influences on shopping behaviour: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(7–8), 683–712.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage.

Gayatri, G., Chan, C., & Hume, G. S. M. M. (1989). Understanding service quality from the Islamic customer perspective.

Hassan, A., Chachi, A., & Abdul Latiff, S. (2008). Islamic marketing ethics and its impact on customer satisfaction in the Islamic banking industry. Islamic Economics, 21(1).

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1995). Evaluating Model Fit. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural Equation Modelling: Concepts, issues and Applications (pp.76–99). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ilyas, S., Hussain, M. F., & Usman, M. (2011). An Integrative Framework for Consumer Behaviour: Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(4), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v6n4p120

Jamal, A., & Sharifuddin, J. (2015a). Perceived value and perceived usefulness of halal labelling: The role of religion and culture. Journal of Business Research, 68(5), 933–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.09.020

Kassim, N. M., & Zain, M. M. (2016). Quality of lifestyle and luxury purchase inclinations from the perspectives of affluent Muslim consumers. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 7(1), 95–119.

Khan, K. (2003). Islam: The Source of Universal Peace. New Delhi: Good Word Books.

Lera-López, F., & Rapún-Gárate, M. (2007). The demand for sport: Sport consumption and participation models. Journal of Sport Management, 21(1), 103.

Lindridge, A. (2005). Religiosity and the construction of a cultural-consumption identity. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 22(3), 142–151.

Loehlin, J.C (1998) Latent variable models: An introduction to factor, path and structural analysis 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Luna, D., & Forquer Gupta, S. (2001). An integrative framework for cross-cultural consumer behaviour. International Marketing Review, 18(1), 45–69.

Mirzazadeh, Z. S. (2017). The Role played by socio-cultural factors in sport consumer behavior. Annals of Applied Sport Science, 4.

Mokhlis, S. (2006). The effect of religiosity on shopping orientation: an exploratory study in Malaysia. Journal of American Academy of Business, 9(1), 64–74.

Mokhlis, S. (2009). Relevancy and Measurement of Religiosity in Consumer Behavior Research. International Business Research, 2, 75–84.

Morphitou, R., & Gibbs, P. (2008). Insights for Consumer Behaviour in Global Marketing: an Islamic and Christian comparison in Cyprus. Retrieved from www.escpeap.net/conferences/marketing/.../Morphitou_Gibbs.pdf

Mukhtar, A., & Mohsin Butt, M. (2012). Intention to choose Halal products: the role of religiosity. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 3(2), 108–120.

Muller, R.O. (1996). Basic Principles of structural equation modelling: An introduction to LISREL and EQS. New York: Springer.

Ohl, F., & Taks, M. (2006). Secondary socialisation and the consumption of sporting goods: cross cultural dimensions. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 2(1–2), 160–174.

Razzaque, M. A., & Chaudhry, S. N. (2013). Religiosity and Muslim consumers’ decision-making process in a non-Muslim society. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 4, 198–217.

Run, E. C., De, Butt, M. M., Fam, K.-S., & Jong, H. Y. (2010). Attitudes towards offensive advertising: Malaysian Muslims’ views. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1(1), 25–36.

Sabri, O. (2012). Preliminary investigation of the communication effects of “taboo” themes in advertising. European Journal of Marketing, 46(1/2), 215–236.

Salzman, M. (2008). Marketing to Muslims. Business Source Complete, 48(18), 18–39.

Sanchez-Franco, M. J. & Roldán, J. L. (2005). Web acceptance and usage model. Internet Research, 15(1), 21–48.

Schneider, H., Krieger, J., & Bayraktar, A. (2011). The impact of intrinsic religiosity on consumers’ ethical beliefs: does it depend on the type of religion? A comparison of Christian and Moslem consumers in Germany and Turkey. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 319–332.

Shreim, M. (2009). Religion and sports apparel consumption: an exploratory study of the Muslim market. Retrieved from https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/277/

Solomon, M. R., Zaichkowsky, J. L., & Polegato, R. (1999). Consumer Behaviour: Buying, Having, and Being. (Canadian ed.). Ontario: Prentice Hall Canada Inc.

Taks, M., Ohl, F., & Mason, C. (2005, January). Sport culture and material culture: an analysis of teenagers’ consumption. In Book of Abstracts: Celebrating the past, looking to the future (pp. 167–168). NASSM.

Tzaffir, S.S., & Dolan, S. (2005). Trust me: A multiple item scale for measuring managers’ employees trust. Management Research, 2(2), 115–32.

Valor, C. (2007). The influence of information about labour abuses on consumer choice of clothes: a grounded theory approach. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(7–8), 675–695.

Watson, N. J., & Parker, A. (2013). Sports and Christianity: Mapping the Field. In N. J. Watson & A. Parker (Eds.), Sports and Christianity: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives (pp. 9–88). New York: Routledge.

Worthington Jr, E. L., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J. W., ... & O’connor, L. (2003). The Religious Commitment Inventory--10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 84.

Wilkes, R. E., Burnett, J. J., & Howell, R. D. (1986). On the meaning and measurement of religiosity in consumer research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 14 (1), 47–56.

Youssef, M. A., Kortam, W., Aish, E. A., et al. (2011). Measuring Islamic-driven buyer behavioral implications: A proposed market-minded religiosity scale. Journal of American Science, 7, 728–741.

Yousaf, S., & Malik, M. S. (2013). Evaluating the influences of religiosity and product involvement level on the consumers. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 4(2), 163–186.