Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2019, vol. 10, no. 2(20), pp. 378–391 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2019.10.19

Economic Freedom, Globalization, and the Shadow Economy in the European Union Transition Economies: a Panel Cointegration Analysis

Yılmaz Bayar (Corresponding author)

Usak University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences

Department of Economics, Usak, Turkey

yilmaz.bayar@usak.edu.tr

Ömer Faruk Öztürk

Usak University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences

Department of Public Finance, Usak, Turkey

omerfaruk.ozturk@usak.edu.tr

Abstract. The presence of the shadow economy differs considerably among the countries. Therefore, determination of factors behind the differences in the size of cross-country shadow economy becomes more of an issue for designing and implementing the right policies to combat the shadow economy. This study investigates the influence of economic freedom and globalization on the size of the shadow economy in the European Union transition economies employing panel data analysis for the period of 2000–2015. The empirical analysis indicates that economic freedom reduces the size of the shadow economy in the long term in the overall panel, but globalization also has a relatively smaller detractive effect on the shadow economy in some countries.

Keywords: shadow economy, economic freedom, globalization, panel data analysis

Received: 1/31/2019. Accepted: 9/16/2019

Copyright © 2019 Yılmaz Bayar, Ömer Faruk Öztürk. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

The shadow economy includes the economic units of households and firms operating outside formal economy, and the decision to go underground mainly depends on cost-benefit analysis between working in formal and informal economies. The firms’ main benefits of working in the shadow economy are avoiding the taxes, transaction costs, social security spending and other costs resulting from the regulations, but the main costs are missing the cheaper formal financing and relatively lower productivity (Berdiev & Saunoris, 2018). Therefore, the shadow economy is a widespread problem of a varying dagree in all the countries. It was calculated that, on average, the shadow economy amounted to 31.9% of GDP in 158 countries during the 1991–2015 period (Medina & Schneider, 2018). However, the dimension of the shadow economy varies considerably among the countries depending on social, cultural, institutional, and economic development levels of the countries. For instance, the size of the shadow economy in 2015 was 6.94% in Switzerland, and 7.0% in the United States, while the shadow economy was 67% in Zimbabwe and 56.38% in Haiti (Medina & Schneider, 2018).

In this context, the researchers have concentrated on the factors behind cross-country differences in the size of the shadow economy considering its unfavorable social, institutional, and economic implications. The relevant literature has elicited that tax and social security burden, regulations, corruption, institutional and legal quality, GDP per capita, inflation, unemployment, and financial sector development are the major factors contributing to the survival of the shadow economy (Ruge, 2010; Bose et al., 2012; Mara & Sabău-Popa, 2013; Remeikiene et al., 2014; Buček, 2017). However, relatively fewer researchers have explored the influence of economic freedom and globalization, two prominent properties of the global economy during the past four decades.

Economic freedom is a composite index consisting of government size, legal system quality and property rights protection, sound money, trade freedom, and regulation (Fraser Institute, 2018). So improvements in economic freedom (lower taxes and regulations, higher institutional quality and business freedom) may contribute to the contraction of the shadow economy. On the other hand, globalization may lower the size of the shadow economy through improving institutions, decreasing trade barriers, raising the convergence of the countries in terms of economic development and governmental policies (Berdiev & Saunoris, 2018).

The European Union (EU) transition countries, the study sample, have made an institutional and economic transformation together with EU membership negotiations as of Berlin Wall fall. The rise in economic freedom and globalization accompanied the decrease in the shadow economy in the EU transition states as seen in Table 1.

The purpose of the article is to analyze the influence of economic freedom and globalization on the volume of the shadow economy in the sample of EU transition economies experiencing considerable improvements in economic freedom and globalization over the period of 2000–2015 employing second generation econometric tests taking cognizance of cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. The literature on determinants of the shadow economy generally has focused on tax and social security burden, regulations, corruption, institutional and legal quality, GDP per capita, inflation, unemployment, and financial sector development, but a lot fewer articles have questioned the influence of economic freedom and globalization on the shadow economy size. In this regard, the paper will make a contribution to the limited literature.

Table 1. Shadow Economy, Economic Freedom and Globalization in EU Transition Economies (1995, 2015)

|

Country |

Shadow economy size (% of GDP) |

Economic freedom index |

Globalization index |

|||

|

1995 |

2015 |

1995 |

2015 |

1995 |

2015 |

|

|

Bulgaria |

32.93 |

20.83 |

4.82 |

7.40 |

62.03522 |

80.12831 |

|

Croatia |

37.33 |

22.96 |

5.08 |

7.04 |

50.0238 |

80.06304 |

|

Czech Republic |

16.81 |

10.47 |

5.76 |

7.49 |

69.99019 |

85.11556 |

|

Estonia |

30.51 |

18.49 |

6.23 |

7.93 |

63.21937 |

83.62048 |

|

Hungary |

30.18 |

20.49 |

6.17 |

7.19 |

70.47316 |

85.11945 |

|

Latvia |

28.65 |

16.62 |

5.68 |

7.72 |

53.8493 |

76.12053 |

|

Lithuania |

32.49 |

18.65 |

5.47 |

7.86 |

56.23113 |

80.29535 |

|

Poland |

29.54 |

16.67 |

5.28 |

7.36 |

64.45012 |

81.13687 |

|

Romania |

33.40 |

22.94 |

4.15 |

7.70 |

57.61455 |

79.23736 |

|

Slovak Republic |

17.92 |

11.18 |

5.42 |

7.24 |

61.04082 |

83.0855 |

|

Slovenia |

28.17 |

20.21 |

5.31 |

7.08 |

54.97357 |

80.94021 |

Source: Medina & Schneider, 2018; Fraser Institute, 2018; KOF Swiss Economic Institute, 2018

The next section sums up the empirical literature on interaction among economic freedom, globalization, and the shadow economy. The dataset and analysis method is explained in Section 3, and empirical analyses are carried out in Section 4. The article ends up with Conclusion.

2. Literature Review

The unfavorable social, institutional, and economic effects of the shadow economy have encouraged the scholars to explore the causes in the differences of cross-country shadow economy. The scholars have generally focalized on the influence of tax and social security burden, regulations, corruption, institutional and legal quality, unemployment, and financial sector development on the size of the shadow economy as seen in Table 2. The tax and social security burden and labor regulations, corruption, unemployment, and trade liberalization from the aforementioned factors positively affect the shadow economy, while financial development, institutional and legal development negatively affect the size of the shadow economy.

Table 2. Literature Summary on the Determinants of the Shadow Economy

|

Determinant of |

The Impact of the Determinant on the Shadow Economy Size |

||

|

Positive |

Negative |

Insignificant |

|

|

Tax and social security burden and labor regulations |

Kanniainen et al. (2004), Manolas et al. (2013), Schneider and Williams (2013), Stankevičius and Vasiliauskaitė (2014), Gasparėnienė et al. (2016), Buček (2017) |

||

|

Unemployment |

Boeri and Garibaldi (20 02), Dell‘Anno and Solomon (2008), Buček (2017) |

Sahnoun and Abdennadher (2019) |

|

|

Financial development |

Blackburn et al. (2012), Bayar and Ozturk (2016) |

||

|

Trade liberalization |

Ghosh and Paul (2008), Fugazza and Fiess (2010) |

||

|

Institutional development |

Thießen (2010), Alm and Embaye (2013), Petreski (2014), Bayar and Ozturk (2016), Bayar (2016) |

||

|

Legal development |

Torgler and Schneider (2009), Thießen (2010), Bayar (2016), Bayar et al. (2018) |

||

|

Corruption |

Manolas et al. (2013), Albulescu et al. (2016), Borlea et al. (2017), Bayar et al. (2018) |

Dreher and Schneider (2010) |

|

As seen in Table 2, few researchers have investigated the influence of economic freedom and globalization on the size of the shadow economy., although both globalization and economic freedom are the prominent features of the economies, especially during the past four decades. The studies on the economic freedom – shadow economy nexus generally conclude that economic freedom reduces the shadow economy (e.g., Razmi et al., 2013; Remeikiene et al., 2014; Remeikiene & Gaspareniene, 2015; Schneider, 2016; Goel & Saunoris, 2017; Berdiev et al., 2018). The empirical studies on the nexus of globalization – shadow economy generally find that the globalization process decreases the shadow economy (Farzanegan & Hassan, 2017; Blanton et al., 2018; Berdiev & Saunoris, 2018).

Razmi et al. (2013) analyzed the interaction between institutional quality indicators and the shadow economy in 51 Organization of Islamic Cooperation states over the period of 1999–2008 with dynamic regression analysis and disclosed that economic freedom decreased the shadow economy. Manolas et al. (2013) researched the determinants of the shadow economy in 19 OECD states over the period of 2003–2008 with regression analysis and revealed that labor and product market deregulation decreased the shadow economy, while credit market deregulation raised the shadow economy. Zarra-Nezhad et al. (2014) researched the influence of economic freedom and globalization on the greatness of the shadow economy with dynamic regression analysis and disclosed that economic freedom and globalization decreased the shadow economy.

Remeikiene et al. (2014) also explored the determinants of the shadow economy in Greece during the period of 2005–2013 and discovered that business freedom had no significant effects on the shadow economy. Remeikiene and Gaspareniene (2015) used regression analysis to research the determinants of the shadow economy in Lithuania during the 2000–2011 period and revealed that improvements in business freedom decreased the shadow economy size. Schneider (2016) explored the major determinants of the shadow economy in different country groups and discovered that economic freedom components had a detractive influence on the shadow economy.

Goel and Saunoris (2017) researched the influence of economic freedom on the greatness of the shadow economy in the study investigating the unemployment – shadow economy nexus considering the gender differences in a panel of over 100 countries during 1990–2006 and disclosed that economic freedom reduced the shadow economy. Ouédraogo (2017) investigated the influence of economic freedom on the shadow economy in 23 Sub-Saharan countries using regression analysis and revealed that economic freedom had no significant effects on the shadow economy, but increase in fiscal freedom and business freedom, components of economic freedom index, raised the shadow economy, while increase in monetary freedom decreased the shadow economy. Sweidan (2017) also analyzed the influence of economic freedom on the shadow economy in 112 nations for the duration of 2000–2007 through regression analysis and disclosed that economic freedom decreased the shadow economy size.

Tekin et al. (2018) examined the influence of economic freedom on the tax evasion in 63 countries and found out that economic freedom affected the tax evasion negatively. Lastly, Berdiev et al. (2018) employed regression analysis to investigate the effect of economic freedom and the main components of economic freedom on the shadow economy in a panel of over 100 countries during the years 2000–2015 and disclosed that economic freedom and its main components reduced the shadow economy.

Aleman-Castilla (2006) analyzed the effect of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) on the shadow economy in Mexico and disclosed that reductions in import duties reduced the informality through raising the profitability for the firms. Farzanegan and Hassan (2017) investigated the influence of economic globalization on the shadow economy in Egypt during the 1976–2013 period with VAR analysis and disclosed that economic globalization had a decreasing influence on the shadow economy. Blanton et al. (2018) researched the influence of economic openness on the shadow economy size in 145 countries for the 1971–2012 period and concluded that economic openness decreased the shadow economy size. Lastly, Berdiev and Saunoris (2018) researched the influence of main globalization types on the shadow economy in 119 nations over 2000–2007 by regression analysis and discovered that globalization, economic, and political globalization reduced the shadow economy.

3. Data and Method

This study employs Westerlund (2008) co-integration test to investigate the influence of economic freedom, and globalization on the size of shadow economy in the European Union transition economies over the period of 2000–2015.

3.1. Data

The shadow economy is represented by the size of the shadow economy calculated with the Multiple Indicator Multiple Cause method (MIMIC) by Medina and Schneider (2018). Economic freedom is represented by Fraser Institute’s (2018) economic freedom index. The economic freedom index is composed of five dimensions such as government size, legal system and property rights, sound money, internationally trade freedom, and regulation. The five main dimensions include 24 components, and the components consist of sub-components. So the index totally includes 42 variables provided from third party sources such as the World Bank and the International Country Risk Guide. Each main and sub-component takes a rating between 0 and 10 (higher grades represent higher economic freedom). The component ratings in each main dimension are averaged to derive ratings of the five main dimensions. Then, the ratings of the five main dimensions are averaged to derive the economic freedom index of the countries (see Fraser Institute (2018) for detailed information about measurement of economic freedom index).

Lastly, globalization was substituted with the globalization index of KOF Swiss Economic Institute (2018), which comprises economic, social, and political globalization dimensions with equal weights. Economic globalization consists of trade and financial globalization, while social globalization consists of interpersonal, informational and cultural globalization. KOF Swiss Economic Institute calculates both de facto globalization based on actual international flows and activities and de jure measures of globalization based on policies and conditions which enable the international flows and activities. However, the KOF Globalization Index is the average of de facto and de jure globalization (see Gygli et al., 2018) for detailed information for detailed information about globalization index). All the series are calculated on an annual basis.

Table 3: Variable Definitions and Data Sources

|

Variables |

Definition |

Source |

|

SHA |

Shadow economy size (% of GDP) |

Medina and Schneider (2018) |

|

EF |

Economic freedom index |

Fraser Institute (2018) |

|

GI |

Globalization index |

KOF Swiss Economic Institute (2018) |

The objective of the study was to examine the influence of economic freedom and globalization on the greatness of the shadow economy. The cross-section dimension of the study was formed from 11 EU transition economies experiencing a considerable social, institutional, and economic transformation (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic, and Slovenia), and the study covers the period of 2000–2015. The data availability determined the sample and time duration of the paper. Lastly, the empirical analysis was conducted via Stata 14.0 and Eviews 10 software.

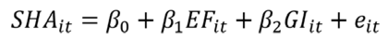

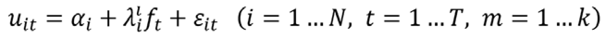

The following econometric model was established to investigate the influence of econometric freedom and globalization on the size of the shadow economy. We expected the growth of economic freedom and globalization to negatively affect the size of the shadow economy regarding the relevant theoretical considerations and empirical literature.

(1)

(1)

3.2. Method

At first, cross-sectional dependence was tested with the Breusch and Pagan (1980) LM test, Pesaran (2004) LM CD test, and Pesaran et al. (2008) LMadj test taking account of dataset characteristics. Then, the slope coefficients’ homogeneity was tested with the Pesaran and Yamagata (2008) adjusted delta tilde test.

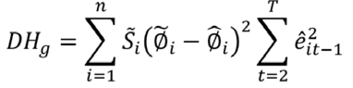

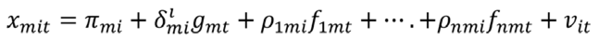

The integration levels of the series were researched with second generation unit root test of Pesaran (2007) regarding cross-sectional dependence. Then, the Durbin-Hausman co-integration test developed by Westerlund (2008) was utilized to analyze the co-integration relationship between the shadow economy, economic freedom, and globalization. The Durbin-Hausman co-integration test takes cognizance of cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. Further, the dependent variable should be I(1) in order to apply the test, but the independent variables can have different integration levels. Two test statistics are calculated while applying the test, called as Durbin Hausman panel statistic and group statistic (Westerlund, 2008). The group statistic posits that the autoregressive parameters are heterogeneous and is calculated as follows:

(2)

(2)

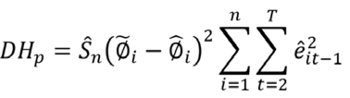

The panel statistic posits the autoregressive parameters are homogenous and is calculated as follows:

(3)

(3)

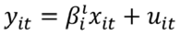

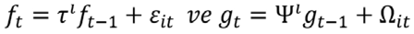

The mean group (MG) estimator (Pesaran & Smith, 1995), the Pesaran (2006) CCEMG (common correlated effects mean group) estimator and the AMG (augmented mean group mean) estimator (Eberhardt & Teal, 2010) are the major estimators of co-integration coefficients. However, panel AMG takes cognizance of heterogeneity and cross-sectional dependence, while other estimators regard only heterogeneity. Panel AMG estimators consider the cross-sectional dependence by including the common dynamic effect to the regression equation. The AMG estimator decomposes the variables in the following way:

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

where xit represents the vector of observable covariates in the above equations, ft and gt are the unobserved common factors, and the λi are the country-specific factor loadings.

4. Empirical Analysis

The pretests of cross-section dependence and homogeneity among the variables are crucial for the identification and application of the right econometric tests of unit root and co-integration. Hence, the cross-section dependence was questioned by the Breusch and Pagan (1980) LM test, Pesaran (2004) LM CD test, and Pesaran et al. (2008) LMadj test, and the results are shown in Table 4. The null hypothesis in favor of cross-sectional independence was rejected because the probability values were less than 5%. Therefore, the findings of the three tests showed a cross-sectional dependence between the series. Consequently, use of second-generation unit root and co-integration tests will yield more robust results, because the second generation test takes cognizance of cross-section dependence and heterogeneity.

Table 4: Cross-sectional Dependence Tests Results

|

Test |

Test statistic |

Prob. |

|

LM |

159.8 |

0.0000 |

|

LM adj* |

18.38 |

0.0000 |

|

LM CD* |

8.137 |

0.0000 |

*two-sided test

Furthermore, the slope coefficients homogeneity was analyzed by means of Pesaran and Yamagata’s (2008) homogeneity tests, and the findings are shown in Table 5. The null hypothesis in favor of homogeneity was rejected because the probability values were less than 5%. So the co-integration coefficients were revealed to be heterogeneous.

Table 5: Homogeneity Tests Results

|

Test |

Test statistic |

Prob. |

|

|

7.221 |

0.000 |

|

|

8.258 |

0.000 |

The question of a unit root in the series was investigated with the CIPS (Cross-Sectional IPS (Im-Pesaran-Shin, 2003)) unit root test of Pesaran (2007) while taking into consideration the presence of cross-sectional dependence, and the results are displayed in Table 6. The null hypothesis in favor of unit root’s presence cannot be rejected at level values of the series, but the null hypothesis was rejected after the first differencing, because the probability values were less than 5%. So the results revealed that SHA, EF, and GI were I(1).

Table 6: CIPS Unit Root Test Results

|

Variables |

Constant |

Constant+Trend |

||

|

Zt-bar |

p-value |

Zt-bar |

p-value |

|

|

SHA |

–1.934 |

0.127 |

0.688 |

0.754 |

|

d(SHA) |

–0.778 |

0.018 |

1.349 |

0.011 |

|

EF |

–0.660 |

0.255 |

–0.834 |

0.202 |

|

d(EF) |

–3.768 |

0.000 |

–2.024 |

0.021 |

|

GI |

–1.524 |

0.164 |

–1.655 |

0.149 |

|

d(GI) |

–2.772 |

0.003 |

–1.109 |

0.034 |

The co-integration relationship among the shadow economy, economic freedom, and globalization was questioned with Westerlund’s (2008) co-integration test while taking cognizance of cross-section dependence and heterogeneity among the series, and the results are shown in Table 7. The group statistic was taken into consideration by the reason of existing heterogeneity, and the null hypothesis in favor of nonavailability of co-integration relationship was rejected at the 10% significance level, because the probability values were found to be less than 10%. Consequently, we reached the end of the presence of co-integration relationship.

Table 7: Results of Westerlund (2008) Co-integration Test

|

Statistic |

p-value |

|

|

Durbin-Hausman Group Statistic |

0.957 |

0.069 |

|

Durbin-Hausman Panel Statistic |

–0.853 |

0.803 |

The slope coefficients were forecast by the panel AMG estimator of Eberhardt and Teal (2010) while taking notice of the cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. The test results are presented in Table 8. The panel co-integration coefficients revealed that economic freedom decreased the shadow economy size considerably because the probability value was found to be less than 5%, but globalization process had no significant effects on the size of the shadow economy in overall panel because the probability values were higher than 10% significance level. However, the individual co-integration coefficients disclosed that economic freedom negatively influenced the shadow economy in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Latvia, Poland, and Slovenia. The impact of economic freedom on the shadow economy size was the largest in Czech Republic with 7%, then in Slovenia and Poland with 3.5%, while the least impact of economic freedom on the shadow economy was observed in Bulgaria with 1.7%. Furthermore, globalization had a decreasing influence on the shadow economy in Bulgaria, Croatia, and Latvia, but a positive influence on the shadow economy only in Poland. The decreasing effect of globalization on the shadow economy was 2% in Croatia and 0.6% in Bulgaria. Furthermore, economic freedom was more effective on the shadow economy in the sample and also had much greater effect on the shadow economy when compared with the effect of globalization on the shadow economy.

Table 8: Co-integration Coefficients Estimation

|

Countries |

EF |

P-value |

GI |

P-value |

|

Bulgaria |

–1.766228 |

0.099 |

–0.6027677 |

0.078 |

|

Croatia |

–4.276711 |

0.288 |

–2.054425 |

0.008 |

|

Czech Republic |

–7.414848 |

0.053 |

–0.0353754 |

0.894 |

|

Estonia |

–5.975449 |

0.067 |

0.4403792 |

0.072 |

|

Hungary |

1.236634 |

0.293 |

–0.0324894 |

0.781 |

|

Latvia |

–2.490584 |

0.004 |

–0.439137 |

0.017 |

|

Lithuania |

–1.514709 |

0.410 |

0.0369133 |

0.835 |

|

Poland |

–3.509901 |

0.044 |

0.4387346 |

0.000 |

|

Romania |

2.410783 |

0.014 |

–0.1738189 |

0.407 |

|

Slovak Republic |

–0.6771052 |

0.479 |

–0.0078419 |

0.934 |

|

Slovenia |

–3.575528 |

0.099 |

–0.1739716 |

0.455 |

|

Panel |

–2.504877 |

0.004 |

–0.236709 |

0.248 |

The findings of the co-integration analysis disclosed that the improvements in economic freedom mainly resulting from the processes of transition and EU membership decreased the size of the shadow economy substantially in both overall panel and individual countries in harmony with related theoretical considerations and empirical findings. However, globalization had a decreasing effect on the shadow economy size in most of the countries, while statistically it was significant only in Bulgaria and Croatia. Both economic freedom and globalization affect the shadow economy through similar channels. Therefore, we can conclude that the effect of economic freedom dominates the effect of globalization. Furthermore, the EU transition economies are generally in relation with other EU member states.

5. Conclusion

The shadow economy is an extensive problem for all the nations to a varying degree and has many adverse social and economic implications for the nations. So, the countries always struggle with the shadow economy to keep it within a reasonable size. In this context, specification of possible common and country-specific determinants behind the shadow economy will be very useful to devise and realize the appropriate policies. This study researches the influence of economic freedom and globalization on the size of the shadow economy, two prominent characteristics of the global economy in EU transition economies over the period of 2000–2015, which are generally ignored in the relevant literature.

The co-integration analysis disclosed that economic freedom had a considerable decreasing influence on the shadow economy size in most of the countries, but the globalization reduced the shadow economy relatively less only in Bulgaria and Croatia. This finding can be explained by the fact that the EU transition states generally are in relation with the other member states. In an economically free, in other words, liberal society, the governments have a protective function for the economic units, and in turn economic units give their decisions freely. In this context, government size, legal system and property rights, sound money, internationally trade freedom, and regulation are designed in a way to provide a relatively economically free society and thus make a contribution to decreasing the shadow economy size. In this regard, the findings of the study for the EU transition economies also verify the aforementioned theoretical considerations. Consequently, structuring the public administration to protect property rights and provide a limited number of public goods such as national defense and sound money and establishing the efficiently market-oriented mechanisms will also make a significant contribution to decreasing the shadow economy.

References

Albulescu, C. T., Tamasila, M., Taucean, I. M. (2016). Shadow Economy, Tax Policies, Institutional Weakness and Financial Stability in Selected OECD Countries. Economics Bulletin, 36(3), 1868–1875.

Aleman-Castilla, B., (2006). The Effect of Trade Liberalization on Informality and Wages: Evidence from Mexico. CEP Discussion Paper No. 763, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Alm, J., Embaye, A. (2013). Using Dynamic Panel Methods to Estimate Shadow Economies around the world, 1984–2006. Tulane Economics Working Paper Series, No.1303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142113482353

Bayar, Y. (2016). Public Governance and Shadow Economy in Central and Eastern European Countries. Administraţie Şi Management Public, 27, 62–73.

Bayar, Y., Odabas, H., Sasmaz, M. U., Ozturk, O. F. (2018). Corruption and Shadow Economy in Transition Economies of European Union Countries: A Panel Cointegration and Causality Analysis. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 1940–1952. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677x.2018.1498010

Bayar, Y., Ozturk, O. F. (2016). Financial Development and Shadow Economy in European Union Transition Economies. Managing Global Transitions, 14 (2), 155–171.

Berdiev, A. N., Saunoris, J. W., Schneider, F. (2018). Give Me Liberty or I Will Produce Underground: Effects of Economic Freedom on the Shadow Economy. Southern Economic Journal, 85(2), 537–562. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12303

Berdiev, A. N., Saunoris, J. W. (2018). Does Globalization Affect the Shadow Economy? World Economy, 41(1), 222–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12549

Blackburn, K., Bose, N., Capasso, S.. (2012). Tax Evasion, the Shadow Economy and Financial Development. Journal of Economic Behavior &Organization, 83, 243–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2012.05.019

Blanton, R. G., Early, B., Peksen, D. (2018). Out of the Shadows or into the Dark? Economic Openness, IMF programs, and the growth of shadow economies. Review of International Organizations, 13(2), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-018-9298-3

Boeri, T., Garibaldi, P. (2002). Shadow Employment and Unemployment in a Depressed Labor market, CEPR Discussion Paper, No. 3433.

Borlea, S. N., Achim, M. V., Miron, M. G. A. (2017). Corruption, Shadow Economy and Economic Growth: An Empirical Survey across the European Union Countries. Studia Universitatis “Vasile Goldis” Arad – Economics Series, 27(2), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/sues-2017-0006

Bose, N., Capasso, S., Wurm, M. A. (2012). The Impact of Banking Development of the Size of Shadow Economy. Journal of Economic Studies, 39(6), 620–638. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443581211274584

Breusch, T. S., Pagan, A. R. (1980). The Lagrange Multiplier Test and Its Applications to Model Specification Tests in Econometrics. Review of Economic Studies, 47(1), 239–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297111

Buček, J. (2017). Determinants of the Shadow Economy in the Czech Regions: A Region-Level Study. Review of Economic Perspectives, 17(3), 315–329. https://doi.org/10.1515/revecp-2017-0016

Dell’Anno, R., Solomon, H. (2008). Shadow Economy and Unemployment Rate in USA: Is There a Structural Relationship? An Empirical Analysis. Applied Economics, 40(19), 2537–2555. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840600970195

Dreher A., Schneider F. (2010). Corruption and the Shadow Economy: An Empirical Analysis. Public Choice, 144, 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-009-9513-0

Eberhart, M., Teal, F. (2010). Production Analysis in Global Manufacturing Production. Economic Series Working Paper 515, University of Oxford, Department of Economics. http://www.economics. ox. ac. uk /research /WP/pdf/paper515.pdf (10.12.2018)

Farzanegan, M. R., Hassan, M. (2017). The Impact of Economic Globalization on the Shadow Economy in Egypt. Macie Paper Series 2017/06, http://www.uni-marburg.de/fb02/makro/forschung/magkspapers (10.12.2018)

Fraser Institute (2018). Economic Freedom, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom (18.12.2018)

Fugazza, M., Fiess, N. (2010). Trade Liberalization and Informality: New Stylized Facts. New York: United Nations, https://unctad.org/en/docs/itcdtab44_en.pdf (05.09.2019). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1596030

Gasparėnienė, L., Remeikienė, R., Heikkila, M. (2016). Evaluation of the Impact of Shadow Economy Determinants: Ukrainian Case. Intellectual Economics, 10(2), 108–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intele.2017.03.003

Ghosh, A., Paul, S. (2008). Opening the Pandora’s Box? Trade Openness and Informal Sector Growth. Applied Economics, 40(15), 1991–2003. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840600915273

Goel, R. K., Saunoris, J. W. (2017). Unemployment and International Shadow Economy: Gender Differences. Applied Economics, 49(58), 5828–5840, https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1343452

Gygli, S., Haelg, F., Sturm, J. E. (2018). The KOF Globalisation Index – Revisited. KOF Working Papers, No. 439, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-019-09357-x

Im, K.S., Pesaran, M.H., Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels. Journal of Economics, 115(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4076(03)00092-7

Kanniainen, V., Paakkonen, J., Schneider, F. (2014). Determinants of Shadow Economy: Theory and Evidence, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228592221_Determinants_of_shadow_economy_theory_and_evidence (10.09.2019)

KOF Swiss Economic Institute (2018). KOF Globalisation Index, https://www.kof.ethz.ch/en/forecasts-and-indicators/indicators/kof-globalisation-index.html (18.12.2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12546

Mara, E.R., Sabău-Popa, D.C. (2013). Determinants of Underground Economy in EU Countries. Theoretical and Applied Economics, Supplement, 213–220.

Manolas, G., Rontos, K., Sfakianakis, G., Vavouras, I. (2013). The Determinants of the Shadow Economy: The Case of Greece. International Journal of Criminology and Sociological Theory, 6(1), 1036–1047.

Medina, L., Schneider, F. (2018). Shadow Economies around the World: What did We Learn over the Last 20 years? IMF Working Paper WP/18/17, (18.12.2018). https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484338636.001

Ouédraogo, I.M. (2017). Governance, Corruption, and the Informal Economy. Modern Economy, 8, 256–271. https://doi.org/10.4236/me.2017.82018

Pesaran, M. H. (2004). General Diagnostic Tests for Cross-section Dependence in Panels. University of Cambridge Working Paper CWPE 0435.

Pesaran, M. H. (2006). Estimation and Inference in Large Heterogeneous Panels with a Multifactor Error Structure. Econometrica, 74, 967–1012. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2006.00692.x

Pesaran, M. H. (2007). A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross-section Dependence. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22(2), 265–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.951

Pesaran, M. H., Smith R. P. (1995). Estimating Long-run Relationships from Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 79–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01644-f

Pesaran, M. H., Ullah, A., Yamagata, T. (2008). A Bias-adjusted LM Test of Error Cross-section Independence. Econometrics Journal, 11, 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-423x.2007.00227.x

Pesaran, M.H., Yamagata, T. (2008). Testing Slope Homogeneity in Large Panels. Journal of Econometrics, 142, 50–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2007.05.010

Petreski, M. (2014). Regulatory Environment and Development Outcomes: Empirical Evidence from Transition Economies. Journal of Economic-Obsahyročníkov, 62(3), 225–248.

Razmi, M. J., Falahi, M. A., Montazeri, S. (2013) Quality and Underground Economy of 51 OIC Member Countries. Universal Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 3(2), 1–14.

Remeikiene, R., Gaspareniene, L., Kartasova, J. (2014). Country-level Determinants of the Shadow Economy during 2005–2013: The case of Greece. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(13), 454–460. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n13p454

Remeikiene, R., Gaspareniene, L. (2015). Evaluation of the Shadow Economy Influencing Factors: Lithuanian Case. 9th International Conference on Business Administration, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 148–154.

Ruge, M. (2010). Determinants and Size of the Shadow Economy – A Structural Equation Model. International Economic Journal, 24(4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/10168737.2010.525988

Sahnoun, M., Abdennadher, C. (2019). The Nexus between Unemployment Rate and Shadow Economy: A Comparative Analysis of Developed and Developing Countries using a Simultaneous-equation Model. Economics Discussion Paper, No. 2019–30.

Schneider, F. (2016). Out of the Shadows: Measuring Informal Economic Activity, https://www.heritage.org/index/pdf/2016/book/chapter4.pdf (10.12.2018)

Schneider, F., Williams, C. C. (2013). The Shadow Economy. London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

Stankevičius, E., Vasiliauskaitė, A. (2014). Tax Burden Level Leverage on Size of the Shadow Economy: Cases of EU Countries 2003–2013. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 156, 548–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.238

Sweidan, O. (2017). Economic Freedom and the Informal Economy. Global Economy Journal, 17(4), 1–10.

Tekin, A., Guney, T., Sağdıç, E. N. (2018). The Effect of Economic Freedom on Tax Evasion and Social Welfare: An Empirical Evidence. Yönetim ve Ekonomi, 25(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.18657/yonveek.299237

Thießen, U. (2010). The Shadow Economy in International Comparison: Options for Economic Policy Derived from An OECD Panel Analysis. DeutschesInstitutfürWirtschaftsforschung Berlin Discussion Papers, 1031. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1641039

Torgler, B., Schneider, F. (2009). The Impact of Tax Morale and Institutional Quality on the Shadow Economy. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30, 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2008.08.004

Westerlund, J. (2008). Panel Cointegration Tests of the Fisher Effect. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 23, 193–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.967

Zarra-Nezhad, M., Akbarzadeh, M. H., Hasanvand, S. (2014). The Shadow Economy and Globalization: A Comparison Between Difference GMM and System GMM Approaches. International Journal of Business and Development Studies, 6(2), 41–57.