Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2023, vol. 14, no. 1(27), pp. 83–109 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2023.14.83

Customer Empowerment and Engagement Behaviours Influencing Value for FinTech Customers: An Empirical Study from India

Archana Nayak Kini

Manipal Institute of Management, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India

netarcmail@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3512-4180

Savitha Basri (corresponding author)

Department of Commerce, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India

savitha.bs@manipal.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0402-403X

Abstract. The article aims to study the impact of consumer empowerment on customer engagement behaviours (CEBs) and their effect on customer value in the FinTech industry of India. A cross-sectional analytical study was carried out to collect data from 380 Indian FinTech app users using a survey questionnaire. The Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) method was applied to test the conceptual model. This is one of the first research studies during the COVID-19 pandemic to show that customer-empowered behaviours predict positive CEBs such as reviews and testimonials, which then contribute to customer value. The indirect effects indicate that CEB mediates the relationship between customer empowerment and value. This study also operationalizes and validates customer engagement behaviour as a formative higher-order construct formed by four dimensions such as customers’ social media influence, form/modality, the scope and channel of engagement. To create customer value, FinTech practitioners and e-marketers should foster online communities and identify and manage customers’ need for control and empowerment for a particular service or product under study thus guiding them in designing customized marketing strategies. The study directs academicians and researchers to build engagement models that can enforce positive CEBs namely e-word of mouth, customer reviews and testimonials.

Keywords: customer engagement behaviour, customer empowerment, experiential marketing, tech-enabled financial services, customer value, e-wom, FinTech

Received: 26/2/2022. Accepted: 26/1/2023

Copyright © 2023 Archana Nayak Kini, Savitha Basri. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

The financial services industry in India is experiencing an immense disruption with digital innovation and financial technologies involving artificial intelligence, virtual, augmented, mixed realities and robotics that foster redesign and delivery of financial products and services (Lee & Shin, 2018; Flavián et al., 2019; Sheth, 2020). Moreover, physical banking transactions have been significantly reduced as a result of the COVID-19 epidemic, mandating the usage of FinTech and virtual banking services for payment needs and other financial services. Intense competition is also seen in the sector as a result of the high adoption rate and entry of FinTech companies (Reserve Bank of India, 2021). In addition, the power shift in the digital environment has forced companies to align with customer needs, who no longer functions as a ‘product taker’ but is actively engaged as a ‘product maker’. Therefore, it has become crucial to understand consumer expectations and their online interaction behaviour in digital financial services. The issue is that CEBs for financial services provided in technology-intensive virtual environments, such as FinTech, are different from those for financial services provided in physical, offline settings. The nature of customer engagement behaviours (CEBs) in a highly interconnected and interactive world of FinTech-related services requires companies to share power in the truest sense of the word if they want to achieve better, meaningful, and lasting engagement. FinTech companies should be aware of shifts in consumer expectations in digital platforms and seek to meet them by assisting their clients in making decisions that fulfil their needs. Thus, empowerment has an impact on CEBs if the personalized solution makes it easier for clients to access financial resources that assist them in making prudent decisions about insurance, credit, and mortgages. CEBs can be fostered by the FinTech firms as a source of competitive advantage by establishing customer relationships that are empowered and self-assured. Since businesses must cede power to consumers and create platforms to support their actions, whether positive or negative, risking the reputation of their brands, prior studies have identified the risks and conundrum of engagement marketing (van Doorn et al., 2010; Morrongiello et al., 2017). Since some companies may lack trust in their customers due to worries about negative e- word of mouth (e-WOM), they would try to exercise control over the comments and viewpoints expressed on social media platforms, contradicting the primary goal of participation (Morrongiello et al., 2017). These companies tread a tight line between upholding corporate control and allowing consumers more sway in the present complicated and non-linear buying process, where influencers are important. Hence, in the customer-driven future, the new power that consumers wield through social media activities like blogs, social networking sites, opinion platforms, and discussion forums would either increase customer value and CEBs or bring forth negative effects. If customers are empowered, will this enhance CEBs and customer value on FinTech platforms? Despite growing in popularity, research on empowerment techniques is still in its early stages, and many issues remain unanswered (Hur, 2019). Despite having the highest rate of FinTech adoption among emerging economies, most earlier studies conducted in India only looked at how CEBs affected consumer loyalty for offline service brands. These studies failed to consider how CEBs and customer value were impacted by empowerment in the context of FinTech digital financial services.

India has a FinTech adoption rate of 87%, which is higher than the global adoption rate of 64% (Ernst & Young, 2017; RBI, 2021). The nascent and innovative financial technology or FinTech companies in India provide services such as digital payments (GooglePay, Paytm), peer-to-peer-lending services (Lendbox, GyanDhan), and personal finance (Scripbox, PolicyBazaar and BankBazaar). Faster and more efficient loan approval, credit scoring, remittances, and enterprise financing services reduce transaction costs and time/distance barriers faced by people to access financial services.

FinTech ecosystem includes a persistent market demand, regulatory support, skilled human and growth capital but has given rise to cut-throat competition. Digital media and technologies come to the rescue by offering customer-centric approaches. Social media and other opinion platforms have given the customers a level playing ground as that of the firms. Customers now have an equal right to information on products, prices, and distribution channels and the power to compare and hand-pick the best option available in the market (Turnquist, 2004; Strauss et al., 2006). The redistribution of power between firms and customers is providing more choices to customers, empowering them to make better consumption decisions and express their opinions. The customers have transformed into brand carriers involved in non-purchase C2C (customer-to-customer) behaviours. Customers who are empowered and involved have a say in the design and building of the product features and brand identity through their expertise, competencies, viewpoints, suggestions, online assessments, and referrals (Jaakkola & Alexander et al., 2014). Nurturing strong customer management of relationships (CMR) through empowered and positively engaged customers is therefore essential and critical to gain competitive edge (Pansari & Kumar, 2017; Bhat & Darzi, 2016; Glavee-Geo, 2019).

Despite having social networks and opinion platforms, the majority of customers are found to be information seekers or lurkers who have taken a more passive stance while contributing to online conversations (Moe & Trusov 2011; Minazzi 2015). A few opinion leaders influence the vast majority of opinion seekers. Hence, what is published online reflects the opinion of a very small group of customers. Investigating further into the reasons behind it tells us that companies are seeking out these few numbers of engaged customers who become influencers to write product reviews and generate e-word of mouth (e-WOMs) (van Doorn et al., 2010). Hence firms must first share power in the true sense of the way for enhanced and desirable engagement to happen. Many previous studies have assessed the drivers of e-WOM, referral and engagement behaviour, but have not yet addressed it in association with customer empowerment or customer value (Morrongiello et al., 2017). The social media networks, blogs and customer-friendly websites facilitate and empower FinTech customers to voice their opinions through feedback, online and offline reviews and testimonials influencing and benefiting other customers. Consequently, the various brand-centred, non-purchase and non-transactional interactions, engagements and shared activities of the technologically empowered and engaged customers positively and emotionally create and enhance customer value (Hollebeek, 2011). Thus, customer value is observed to be an expression of customer engagement and empowerment that assists in retaining existing customers as well as gaining new customers in this emerging service industry (Youssef, 2018; Pires et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 2010). Thus, the present study fills a gap in the literature on the relationship between empowerment and engagement and demonstrates that consumers who are empowered are more engaged with the company and also generate better customer value. Thus, identifying the dimensions of empowerment and engagement which result in customer value is crucial for the FinTech industry. The customer-centric metrics and strategies act as a differentiator in the emerging industry of FinTech to bring forth the necessary CEB (van Doorn et al., 2010; Muniz & O’Guinn, 2001) and customer value (Rust et al., 2004; Hollebeek, 2011). Therefore, the objective of this study is to assess the direct and indirect influence of empowerment on customer value generation with customer engagement acting as the mediator. The present study offers advice to FinTech practitioners on how best to manage and control customers’ tech-enabled power and control needs. Thus, the present study emphasizes that FinTech managers develop personalized marketing strategies and closed feedback mechanisms and systems to create positive customer engagement behaviours (CEBs) such as e-WOMs, reviews, and testimonials. These strategies and mechanisms help the FinTech industry to build trust and confidence resulting in long-term customer value. Theoretically, the current study confirms the tenets of approach/inhibition theory in the context of the FinTech industry and supports the idea that customer empowerment influences reward perception (customer value), which is mediated by the approach/inhibition mechanism. Also, the findings of the study corroborate the SD logic viewpoint by noticing a strong influence of CEB on customer value.

The introduction section is followed by the literature review of the variables forming the conceptual framework. The study design, approach, methods and study tools used for this quantitative research study are explained, which is followed by the analysis and results. The results from the evaluation of the measurement model and the structural model following structural equation modelling based on a partial least squares approach are outlined. Finally, we discuss the findings of our study in comparison to previous literature. It provides theoretical and managerial implications, states the limitations and paves the path for future research in this domain before providing the concluding remarks of the study.

2. Literature Review

Customer Value is the value perceived and moulded by the customers in their minds through the various interactions, engagements and shared activities with the brand and other customers (Hollebeek, 2011). This notion was endorsed by Jaakkola and Alexander (2014) further assimilating more resources to form a system-oriented value-creation process.

Customer Empowerment. The customer value creation process in an internet-enabled service industry can be explained through the approach/inhibition theory of power. A highly empowered person displays an approach-oriented mechanism (Anderson & Berdahl 2002; Keltner et al., 2003). Customers who are approach oriented are comfortable voicing their concerns, opinions and suggestions, engaging with the brand and building value in the process. However, customers who exhibit imitating behaviour are less empowered and display an inhibition-oriented mechanism, which makes them reluctant to voice their problems out of concern for potential disputes with the company and other clients. As a result, agentic/communal disorientation inhibits any value creation (Shin et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2016).

According to van Doorn et al. (2010), firms are now beginning to develop experiential marketing strategies driven by customer empowerment to influence the emotional/affective side of the customer. Customer empowerment is defined as the customers’ perception of authority over service experience produced by organisations’ empowerment strategies that help to make their own choices at their convenient time and terms and that drives customer behaviour (Han et al., 2019). Turnquist (2004) defined consumer empowerment as the process of increasing consumer value by providing the required access, materials, training and systems which are easily available to customers. Pires (2006) further stated that customer-managed relationship (CMR) has empowered individual consumers to make decisions on the service types and choices as per their need. It is a collective system of elements, namely customers, system, firm and the brand, where the firm has information on customer likes, dislikes and actions, and similarly, each consumer has information on the available product features and communication channels enabling customer value. Several researchers have similarly validated that empowered customers help firms to create value compared to the customers who are disempowered due to the approach/inhibition mechanisms (Shin et al., 2020; Jaakkola & Hakanen 2013; Wu et al., 2016; Prahalad & Ramaswamy 2004). The highly empowered people tend to differentiate themselves from the lesser empowered customers by being more vocal and comfortable to express their opinions regularly. In comparison to highly empowered customers, the lesser empowered customers are community-oriented and believe in conforming to the group’s beliefs (Wu et al., 2016; Anderson & Berdahl, 2002). Thus, the two groups tend to differentiate themselves in terms of engagement and value by their level of empowerment. As per the approach/inhibition theory of power, access to rewards (for example, customer value) is correlated with the amount of power that customers are granted. We hypothesize that:

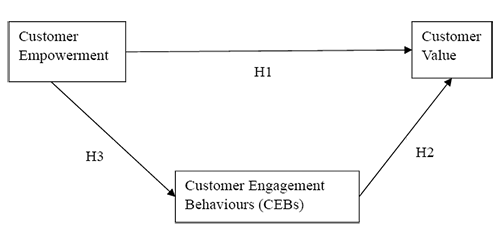

H1: Higher levels of customer empowerment are associated with increased customer value.

Customer Engagement Behaviours. There are two approaches to studying customer engagement. Brodie et al. (2011) embrace the psychological perspective, consisting of cognitive, emotional, and behavioural elements. On the other hand, customer engagement can be studied strictly from a behavioural point of view. In the current study, our research focuses more on customer engagement behaviours (CEBs) than on customer engagement.

The Service-Dominant (SD) logic proposes that all value exchanged in the market is service-based, in which various businesses and consumers interact to create value (Vargo & Lusch, 2004). It helps to understand the impact of customer-to-customer relational behaviours on co-creation and customer value. The SD logic stressed proactive efforts and contributions by both the seller and the buyer in value creation. In a network of dyadic, triadic, and complex relationships, the value-in-context is produced when several actors interact as an operant resource (Chandler & Vargo, 2011). Chandler and Lusch (2015) identified that customer value co-creation behaviour is a dynamic expression of CEBs, which denotes firm or brand-centred non-transactional behaviours that manifest positively or negatively depending on the customers’ motivators (van Doorn et al., 2010). The higher-order model for CEBs consists of valence (positive or negative), form or modality, scope, choice of channel and customers’ social media influence.

The Form/Modality component measures customer expression types and resources that a customer spends on the brand at the most basic level based on time and money spent. Bolton and Saxena-Iyer (2009) describe ‘form’ in terms of in-role behaviours, extra-role behaviour and elective behaviours. Scope of engagement encompasses customers’ extra-role behaviours which include providing reviews and suggestions on their product experiences to the company and helping to improve or develop new products based on customer needs (van Doorn et al., 2010; Kumar & Pansari, 2016). Customers’ choice of a channel depicts the preference shown by the customer to communicate via phone, in-person, in a retail atmosphere or via email or website communication affecting the CEB (van Doorn et al., 2010). Customers’ social media influence (CSMI) symbolizes the C2C conversations happening in social media communities where customers exchange views and opinions on product features and benefits. This mechanism inspires and guides other customers positively increasing customer value through influence and referrals (Kumar & Pansari, 2016; Kumar et al., 2010). Table 1 outlines the results of the most recent literature review on customer engagement behaviour, empowerment and value.

Table 1

Summary of Recent Studies on Customer Empowerment, Engagement and Value

|

|

Country |

Study |

Sample |

Variables |

Key findings |

|

Hollebeek et al. (2022) |

New |

Mixed Bibliometric and network analysis |

- |

Mapping CE‘s landscape based on the past 15 years‘ literature |

CE measurement/methods, online CE, CE’s value co-creating capacity, CE conceptualization and customer/consumer brand engagement were identified as themes for future research. |

|

Barari et al. (2021) |

Australia |

A meta‐analysis of customer engagement behaviour |

184 publications with a sample size of 146,380 |

Customer Engagement Behaviour was studied. The findings expose that the engagement happens through two channels: an organic channel that is relationship-oriented (perceived quality, perceived value and relationship quality) and a firm-sponsored channel (functional and experiential initiatives). |

|

|

de Oliveira Santini et al. (2020) |

Brazil |

A framework and meta-analysis |

97 studies with 161,059 respondents |

Examines customer engagement in social media (CESM); Results state that satisfaction is a stronger predictor of CE in high (vs. low) convenience, B2B (vs. B2C), and Twitter (vs. Facebook and Blogs). Twitter can improve CE twice as likely as other social media platforms. CE is revealed to yield value in terms of firm performance, behavioural intention, and WOM. Hedonic consumption gives higher customer engagement to firm performance effects vs utilitarian consumption. |

|

|

Glavee-Geo et al. (2019) |

Ghana |

Cross-sectional/Quantitative/ PLS technique using SmartPLS 3.0 |

595 mobile money service users of Ghana |

Researchers examine the drivers and consequences of CE through the experiences of users in a developing country. Perceived risk, consumer empowerment, subjective norm, performance expectancy and effort expectancy influence the affect component of CE and explain around half of its variance. |

|

|

Prentice et al. (2019) |

Australia |

Quantitative |

- |

Examines how customer and firm-based factors are related to CE |

The study shows that customer-based factors such as brand experience and brand love impact CE. |

|

Moliner-Tina et al. (2019) |

Spain |

Cross-sectional/quantitative |

1,790 customers of two Spanish banks |

Bank customer engagement, customer experience, non-transactional customer behaviours |

Established the role of the bank’s CE as the mediator in a significant relationship between customer experience as the influencer and non-transactional behavioural outcomes. |

|

Youssef et al. (2018) |

Egypt |

Review |

- |

CRM, CE and Customer Equity framework for a B2B environment. Findings indicate that CE is a multidimensional construct with three dimensions: cognitive, emotional or behavioural engagement. Customer satisfaction, commitment, trust and involvement were regarded as antecedents to CE, and customer equity as the outcome. |

|

|

Morrongiello et al. (2017) |

France |

Qualitative and a quantitative study |

753 |

The link between Empowerment and Power Sources such as personal capacities (expert power), relational capacities (legitimate power), or collective capacities (power to reward or punish) |

Customers engage for the following reasons: belief that they can help companies without resorting to the venting of negative feelings (punishment), brand attachment, and reciprocity. |

|

Jaakkola & Alexander (2014) |

Scotland (UK) |

Qualitative / embedded case study approach |

42 |

The impact of CEB in the value creation for a traditional non-digital environment |

They defined CEB to be a system process with 4 categories and involving various resources to form customer value and co-created offerings and value. |

|

Hollebeek et al. (2013) |

New Zealand |

Qualitative/ depth-interviewing/focus group findings |

14 consumers |

Customer value - CV Customer engagement- CE |

CV and CE are related in a curvilinear manner. Thus, a more hedonic brand positioning is to be followed so that optimum value is derived. |

|

Goyal & Srivastava (2015) |

India |

Review |

Indian bank customers |

Competition and Customer engagement model and strategies |

Relationship-building technologies can help financial services companies to slowly nurture and deepen customer engagement thus forming an interactive, personalized experience across channels. |

|

Kumar et al. (2010) |

India |

Conceptual |

- |

The CE model consists of CLV, CRV, CIV and CKV 1) Customer Lifetime Value [CLV] represents customers’ purchasing behaviour (repeat purchases or more purchases through up-selling and cross-selling). (2) Customer Referral Value [CRV] relates to the acquisition of new customers through the firms’ referral programs. (3) Customer influencer behaviour [CIV] (4) Customer Knowledge Value [CKV] CE’s secondary offerings consist of customer referrals, SM brand-related conversations/feedback/suggestions to the firm. |

|

|

van Doorn et al. (2010) |

The Netherlands |

Conceptual Model |

- |

CEBs are the customers’ behavioural expressions about the company/brand in their non-purchase interactions. Valence, form/modality, scope, nature of the impact, and customer goals are the dimensions of the CEB in the model. |

Developed a conceptual model of the predictors and outcomes of CEB with views from the customer, company and society. |

|

Pires (2006) |

Australia |

Qualitative/ Historical quality gap analysis |

- |

Usage of information and communication technologies (ICT), customer empowerment and the role of marketing strategies |

ICT-based marketing strategies can regulate delegation thus nurturing consumer empowerment. |

Customer value provides the reasons for firms to invest in the maintenance of meaningful customer associations making them stay with the brand and also helping to bring in new customers (Youssef, 2018). Lemon (2001) defined customer value as the aggregate value generated from both the present and future expected customers. Hollebeek et al. (2013) further stated that value and engagement follow a curvilinear fashion of relationship, where customer value shows an increase with an increasing level of engagement but drops after a further increase in engagement, especially for hedonic brands. Customer value is believed to represent the value created through customer interactions with the brand and thus provides a measure of the customer’s perceptions about the value derived from these engagements (Pansari & Kumar, 2017). Thus, CEB acts as a mechanism for customers to enhance value for themselves and the firm. We posit that:

H2: Higher levels of customer engagement behaviours are associated with increased customer value.

Van Doorn et al. (2010) observed that although managers encourage customers to engage online, they also attempt to retain control over the review system specially to circumvent or remove any negative customer reviews and opinions. Thus, managerial control over CEBs reverses the very purpose which requires sharing control over communications representing empowerment (Morrongiello et al., 2017). Thus, customer empowerment is a precondition for desirable and positive customer engagement. A satisfied, empowered and committed individual can only spread positive word of mouth and brand engagement (Matos & Rossi, 2008). According to the approach/inhibition approach of power, when a consumer is empowered, approach-related processes like CEBs are triggered (Anderson & Berdahl, 2002; Keltner et al., 2003). Thus, we hypothesize that:

H3: Higher levels of customer empowerment are associated with increased customer engagement behaviours.

The above-hypothesised relationships are shown in the theoretical model (Figure1).

Figure 1

Theoretical Model

3. Methods

3.1 Research Design

The customers’ levels of empowerment, engagement and perceived value generation through the use of FinTech apps were investigated by adopting the positivism philosophy as it gives the researchers a scientific and systematic process to follow. As the sampling frame was not accessible, a snowball sampling method was adopted (Chih-Pei & Chang, 2017). The initial sample of respondents were FinTech app customers comprising individuals and businesses, who then referred their customers and acquaintances who used the FinTech apps. A snowball effect was created to capture the required sample respondents. The principal theories of SD-Logic, approach-inhibition and agentic-communal orientation formed the basis to understand the non-transactional behaviours and phenomena happening through a system-centric approach. These theories coupled with the literature review helped to frame the various hypotheses concerning the conceptual model. The hypotheses were later empirically verified and tested.

3.2 Measurement Tools

The survey questionnaire was designed by using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To verify the survey validity, we derived all the measurement scales in this investigation from measures used in similar earlier studies. It consisted of questions to capture the response related to the variables such as customer empowerment consisting of 13 items (Han et al., 2019; Pires et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2019) and customer value (Pansari & Kumar, 2017; Vivek et al., 2014) related to the use of the FinTech app. The higher-order model for CEBs included valence (positive or negative), form or modality, scope, choice of channel and customers’ social media influence consisting of 22 items (Hoang, 2019; van Doorn et al., 2010; Moliner et al., 2018). The working definition of these constructs was explained in the previous section.

SmartPLS 3.0 was used to carry out the structural equation modelling (SEM) following the PLS (Partial Least Squares) guidelines provided by Hair et al. (2013) and Henseler et al. (2012). The reliability of the constructs is increased by PLS-SEM, which minimizes the consequences of measurement errors. PLS-SEM can concurrently incorporate the model’s structure as a whole when estimating variables, eliminating any possibility of measurement error or endogeneity problems (Hair et al., 2019).

The measurement model was initially assessed by calculating the reliability and validity values of the constructs under study. The higher-order model of CEB was validated via the disjoint two-stage approach (Sarstedt et al., 2019). The structural model was then computed to check the significance of relationships between the variables stated in the hypotheses.

3.3 Data Collection

The sampling frame consisted of customers in South India who were using FinTech apps such as Google Pay, PhonePe, Amazon Pay, BHIM, PayTM, BankBazaar, Policy Bazaar and so on to carry out their payment and financial advisory needs. Karnataka in south India falls among the states which have a high level of financial inclusion score as well as the highest FinTech adoption rate (about 26.64%) in India. The tentative sample size was calculated to be 380 customers (margin of error of 5% and a confidence level of 95%), and 10% were further added to accommodate non-response errors, thus the final target sample consisted of 418 customers. The survey was administered to this sample digitally as well in person during January and April of 2021. Both individuals as well as businesses including retail shop owners helped to refer and communicate more leads by sharing the email addresses and phone numbers of their contacts who use payment and advisory apps. This new group of leads referred more people from their network with a snowball effect and thus the final sample size of 418 was met. Out of the 418 responses, 29 had incomplete responses, and 9 exhibited a straight-lining trend, therefore 38 were removed, and 380 responses were kept for analysis.

3.4 Common Method Bias

The common method bias was controlled by several measures (Podsakoff et all., 2012); the effect of proximity was reduced by changing question ordering to a dimensional level. During the pilot study, judges or experts were asked to score the items’ social desirability, and the language of highly rated questions was altered to lessen their perceived social attractiveness. The effect of acquiescence and disacquiescence bias was controlled by including positive and negative items (later reversed for data analysis). The well-established and validated measures were used, which effectively controlled item word bias. Instructions, research motivation and the significance of the study were provided to maximise respondents’ motivation.

3.5 Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

The EFA indicated that CEB (customer engagement behaviour) has four factors which are the four lower-order constructs making CEB a higher-order construct. In the context of PLS-SEM, when the study construct is multidimensional, it is often referred to as HCM (Hierarchical Component Model) (Sarstedt et al., 2019).

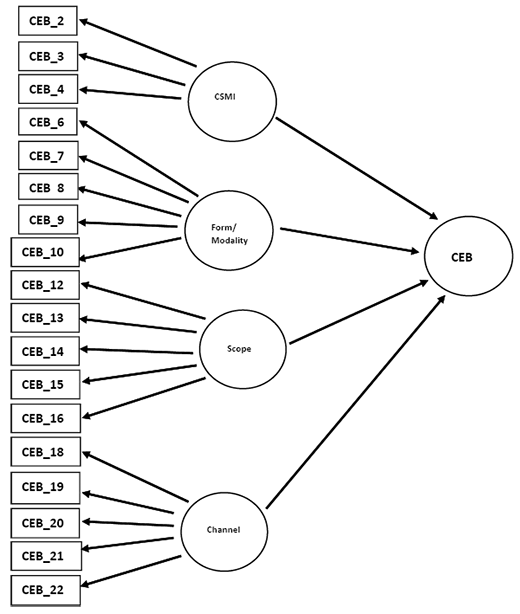

Higher-order components (i.e., constructs that capture a more abstract idea, HOC) and lower-order components (i.e., constructs that capture the dimensions of higher-order concept, LOC) are the two main components of these constructs (Hair et al., 2017). Correspondingly, we carried out a literature study to help understand and validate the nature of CEB. The support of literature validated CEB to be a formative second-order construct defined by four reflective first-order constructs or components such as form/modality (FM), scope, customers’ social media influence (CSMI) and the choice of the channel (CC) (van Doorn et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2016). A visual representation of the construct CEB with its four lower-order constructs is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Visualization of the Higher Order Construct of Customer Engagement Behaviour

Note. The indicators (CEB_1 through CEB_22) of the lower order construct are detailed out in Table 2. CEB- Customer engagement behaviour, CSMI- Customer social media influence.

Based on the recommendations provided by Jarvis et al. (2003) and Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer (2001), this study operationalizes customer engagement behaviour as a formative higher-order construct with four reflective dimensions.

4. Results

4.1 Profile of the Respondents

The app customer data which was collected from the sample population showed a profile consisting of 46% of Google pay users, 17% PhonePe and PayTM users each, and the rest 37% users of Yono (SBI), Imobile (ICICI), AmazonPay, BHIM, Bankbazaar and Policybazaar. The sample consisted of a majority of male users (about 55% of the sample population), and the rest 45% were female customers. Millennials in the age group of 25-40 consisted of almost 50% of the sample population followed by the below 25 age group with 31%, the 41-60 age group comprising 18% and a mere 2% of customers above the age of 60 years. The income level of the sample was anywhere between $1-$13,468 per year (1 US$= Rs 82.34, 10 October 2022). The majority of the sample, i.e., 57% had attained education of post-graduation.

4.2 Measurement Model

From the exploratory factor analysis and literature study, it was observed that CEB is a second-order construct having four dimensions. Hence, the measurement model consisting of a second-order reflective-formative construct was validated using a two-staged disjoint analysis (Sarstedt et al., 2019). The reliability and validity of all the lower-order constructs which formed the reflective measurement model were initially examined, and the values were calculated (see Table 2). Construct validity, indicated by Cronbach’s alpha (α) value, was above 0.7 satisfying Henson’s (2001) threshold limit. Indicator and composite reliabilities met the threshold values of Hulland (1999) being higher than 0.7. The constructs also established the convergent validity specified by AVE (Average Variance Explained) being greater than 0.5 (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 2

Construct Reliability, Validity & Multi-Collinearity

|

Construct |

Indicators |

CA |

CR |

AVE |

OL |

IR |

|

Customer Value

|

CV_1: My transactions with this app make me content. |

0.906 |

0.928 |

0.683 |

0.757 |

0.579 |

|

CV_2: Owning this app on my phone makes me happy. |

|

|

|

0.841 |

0.700 |

|

|

CV_3: I enjoy referring this app to my friends and relatives because of the monetary referral incentives. |

|

|

|

0.775 |

0.595 |

|

|

CV_4: I feel valued in my interactions with the company. |

|

|

|

0.870 |

0.746 |

|

|

CV_5: My app-related engagement has a lot of advantages resulting from it. |

|

|

|

0.860 |

0.716 |

|

|

CV_6: I like my app-related engagement because it benefits me in the end. |

|

|

|

0.872 |

0.760 |

|

|

CEB |

CSMI: Customers’ Social Media Influence |

0.891 |

0.925 |

0.754 |

|

|

|

CEB 2: I actively discuss this app with other customers on social media. |

|

|

|

0.892 |

0.795 |

|

|

CEB 3: I seek advice from other customers on how to solve problems. |

|

|

|

0.855 |

0.731 |

|

|

CEB 4: I love talking about the benefits and positive app experiences with other customers on social media. |

|

|

|

0.887 |

0.786 |

|

|

FM Form/Modality: |

0.894 |

0.923 |

0.705 |

|

|

|

|

CEB 6: I would organize a public action against the firm in the case of a dispute. |

|

|

|

0.824 |

0.678 |

|

|

CEB 7: I tend to spend time blogging to express my experiences. |

|

|

|

0.744 |

0.553 |

|

|

CEB 8: I actively participate in charity events organized by the firm, thus donating both money and time. |

|

|

|

0.885 |

0.783 |

|

|

CEB 9: I generally donate through charity events but do not have the time to participate in them. CEB 10: I tend to complain about the app/firm on social media or website forum. |

|

|

|

0.893

0.736 |

0.797

0.542 |

|

|

CEB |

Scope |

0.926 |

0.947 |

0.819 |

|

|

|

CEB 12: I intend to help other customers through my conversations. |

|

|

|

0.747 |

0.558 |

|

|

CEB 13: My product-related expressions and actions help my company. |

|

|

|

0.859 |

0.737 |

|

|

CEB 14: I provide feedback about my experiences with the app to the firm. |

|

|

|

0.916 |

0.839 |

|

|

CEB 15: I provide suggestions for improving the performance of the app. |

|

|

|

0.934 |

0.872 |

|

|

CEB 16: I provide feedback/suggestions for developing new service offerings for my app. |

|

|

|

0.907 |

0.822 |

|

|

Choice of Channel Preference for communication channels while dealing with other customers and companies |

0.867 |

0.900 |

0.602 |

|

|

|

|

CEB 18: with other customers via the Internet (social media or website) |

|

|

|

0.795 |

0.632 |

|

|

CEB 19: with other customers via phone, mail, or e-mail |

|

|

|

0.834 |

0.695 |

|

|

CEB 20: with company in-person customer to the firm |

|

|

|

0.734 |

0.538 |

|

|

CEB 21: with the company via the Internet (social media or website) |

|

|

|

0.801 |

0.642 |

|

|

CEB 22: with the company via phone, mail, or e-mail |

|

|

|

0.741 |

0.549 |

|

|

CEMP |

EMP_1: I have a wide variety of choices of service applications to choose from. |

0.909 |

0.930 |

0.687 |

0.619 |

0.481 |

|

EMP_2: I have access to service portfolio information from the firm. |

|

|

|

0.750 |

0.521 |

|

|

EMP_3: The app provides the facility and platforms to interact with the customers who have used the service. |

0.756 |

0.494 |

||||

|

EMP_4: Customers are empowered by the app’s relationship management technology. |

0.783 |

0.619 |

||||

|

EMP_5: There is a periodic feedback review after raising complaints. |

0.777 |

0.536 |

||||

|

EMP_6: The app encourages me to share my experiences. |

0.666 |

0.629 |

||||

|

EMP_7: I feel free to provide suggestions in the discussion forum. |

0.672 |

0.629 |

||||

|

EMP_8: I feel a higher sense of empowerment when my ideas receive more positive support from the company. |

0.779 |

0.587 |

||||

|

EMP_9: I have the freedom to adjust the service delivery according to my needs and situations. |

|

|

|

0.763 |

0.607 |

|

|

EMP_10: The firm will customize the service according to my personal needs. |

|

|

|

0.755 |

0.689 |

|

|

EMP_11: I am empowered through personalized messages and recommendations. |

|

|

|

0.748 |

0.651 |

|

|

EMP_12: The service provider gives me the feeling that I am involved in the service development process. |

|

|

|

0.743 |

0.724 |

|

|

EMP_13: I feel I have an impact on the company’s service-related decisions. |

|

|

|

0.777 |

0.691 |

Note. CA= Cronbach Alpha; CR = Composite Reliability; AVE = Average Variance Extracted; OL = Outer Loadings (Standardized); IR = Indicator Reliability; CEB = Customer Engagement Behaviour; CEMP = Customer Empowerment. Source: Primary Survey.

Discriminant validity specified by Henseler (2015)’s heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlation is less than 0.9 (threshold value) hence establishing discriminant validity (see Table 3). All the constructs were found to be reliable and valid.

As a precursor to the second stage, the latent scores of the lower-order constructs associated with CEB were included in the data set. These four latent variables formed the indicators of the higher-order construct CEB in stage two. A 5000-sample bootstrapping procedure was run to endorse the measurement model containing this formative higher-order construct (HOC) CEB. The outer weights of Scope, FM (Form/Modality), CSMI and Channel were checked and as they were below 0.5, the outer loadings were also checked. As the outer loadings were found to be above 0.5, the model was well-validated for significance.

Table 3

Discriminant Validity using (HTMT) Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio

|

|

CEMP |

CEB |

|

CEB |

0.560 |

|

|

CV |

0.518 |

0.576 |

Note. CEMP=Customer Empowerment; CEB=Customer Engagement Behaviour; CV=Customer Value.

4.3 Structural Model Assessment

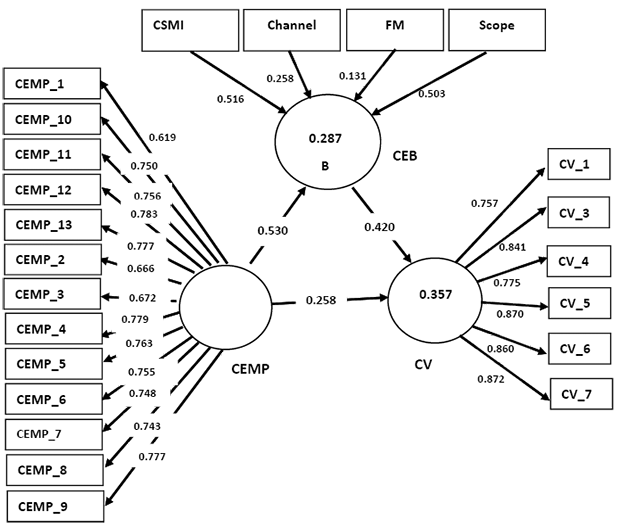

The PLS path model depicted in Figure 3 assists in understanding the direct effects.

4.3.1 Direct effects and effect sizes. Statistics shown in Table 2 indicate the hypotheses on direct paths are supported when the p-value is less than 0.05. Path-coefficient (β) further indicates the strength of influence of a particular antecedent on its subsequent endogenous variable. Here, CEB has a higher influence on customer value (CV) with β=0.420 than customer empowerment (CEMP) with β=0.258. CEMP has a significant influence on CEB suggested by the β of 0.530. Moreover, the effect size indicated by the f2 value is a measure of the impact of a particular predictor construct on an endogenous construct (see Table 4) (Hair et al., 2013). The f2 value of CEB on the endogenous construct customer value (CV) is 0.198, approximately 0.2, which signifies that CEB has a medium effect on the construct CV’s R2, whereas the f2 value of CEMP on CV is 0.072, which is considered a small effect. The f2 effect size value of CEMP on CEB is 0, which is a large effect.

Figure 3

PLS Path Model for CEMP-CEB-CV Model

Note. CEMP= Customer Empowerment; CEB = Customer Engagement Behaviour; CV = Customer Value.

4.3.2 Indirect and Mediation Effects. CEMP has a significant indirect effect on Customer value (CV) mediated by CEB, defined by the path co-efficient (β) of 0.224, t value of 6.345 and the p-value of 0.000 (see Table 4).

VAF further calculates the mediation effect (Variance Accounted For) = Indirect Effect/ Total Effect. Here, the VAF value is 0.468, or 46.8%, which indicates that CEB mediates the path CEMP>CEB>CV, and the mediation is observed to be complementary.

Table 4

Direct and Indirect Effects and Effect Sizes (f2 )

|

Hypothesised path relationships |

β |

t |

p |

f2 |

Hypothesis |

|

Direct Effects |

|||||

|

H1: CEMP -> Customer Value |

0.258 |

4.307 |

0.000 |

0.072 |

Supported |

|

H2: CEB -> Customer Value |

0.420 |

7.392 |

0.000 |

0.198 |

Supported |

|

H3: CEMP -> CEB |

0.530 |

11.476 |

0.000 |

0.395 |

Supported |

|

Indirect Effects |

|||||

|

CEMP>CEB>Customer Value |

0.224 |

6.345 |

0.000 |

|

|

Note. CEMP=Customer Empowerment; CEB = Customer Engagement Behaviour. Source: Primary Survey.

4.3.3 Predictive validity. The coefficient of determination R2 value largely helps to assess the structural model for its predictive validity (Henseler et al., 2012). Customer value (CV) has a large R2 value of 0.357 indicating that almost 35.7% of the variance in CV is described by its antecedents, which are CEB and customer empowerment (CEMP). CEB has an R2 value of 0.280, indicating that only about 28% of the variance in CEB can be defined by CEMP. The above R2 values thus establish the model’s predictive validity. The model fit indices were checked. SRMR value is 0.0673, which is less than 0.10 or 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999) and hence is considered to be a good fit, and NFI (normed fit index) of 0.856 represents an acceptable fit.

4.3.4 Predictive relevance. The predictive relevance of the model is indicated by the Q2 value. CEB has a Q2 value of 0.188, and CV has a Q2 value of 0.254. As the Q2 values are considerably above 0.15, it provides support for the model’s medium predictive relevance for the two endogenous constructs, CEB and CV.

5. Discussion & Findings

Our results demonstrate that customer empowerment has a strong beneficial impact on customer engagement behaviour, as defined by e-WOM, reviews, and testimonials from FinTech consumers in India. Similarly, the CEB has a strong positive influence on customer value. This means that the financial app customers’ perception of control over service experience due to empowerment strategies employed by the financial company has a significant direct impact on their engagement behaviours. Our findings agree with Han’s (2010) and Pires’s (2006) results that consumer empowerment represented by CMR (Customer Managed Relationships) is the driver of customer behaviour. The study findings of 2008, which reveal that boosting customer empowerment increases trust and security, leading to more active engagement with the product and brand, also corroborate the findings of the present study (Bonsu & Darmody, 2008; DeMatos & Rossi, 2008). More recently, Morrongiello’s (2017) study findings support the idea that true occurrence of customer engagement necessitates empowerment that shares control over customer communications. Thus, FinTech startups need to focus on CMR which gives more power to the individual consumers to decide upon the type and delivery of service. This control over customer choices advances their ability to make better consumption decisions, and they positively engage with businesses.

Customer empowerment has a major indirect impact on customer value, which is mediated in part through CEB. As a result, customers who are technologically empowered by the firm tend to get more value from the brand when they are positively engaged. These discussions validate previous study conceptualizations and findings by Shin et al. (2020), Jaakkola and Hakanen (2013), Wu et al. (2016), and Prahalad and Ramaswamy (2004). FinTechs must further identify customers’ contributions achieved through empowerment mechanisms, and their views must be acknowledged, valued, and rewarded. Positive e-WOM, review, and referral behaviour on online platforms demonstrates empowered engagement, benefiting other customers in their social media communities and thereby boosting their value. However, if the company fails to engage empowered customers due to a lack of social media platforms or by failing to close the feedback loop, closely work on the reviews or implement good customer suggestions, the potential for customer value generation could be harmed. Furthermore, if the company fails to empower customers in the first place, disempowerment may result in a significant level of unfavourable reviews and word of mouth (Porter et al., 2011) The resulting animosity and customer anger will almost certainly erode rather than increase the customer value that has already been established. Thus, if used systematically, digital technology can help FinTech firms develop interactive, personalized, and empowered interactions that improve consumer engagement, confirming the findings of Goyal and Srivastava (2015).

Our findings on the significant relationship between CEB and customer value agree with study results that discovered a cause-and-effect relationship between engagement and customer value, which is curvilinear. Our findings also conform to previous study findings by Kumar et al. (2010) and Hollebeek (2011) based on CEBs aiding brands both explicitly through customer purchases and implicitly through social media brand dialogues, customer-provided feedback, recommendations, referrals, interactions, engagements, and shared activities that generate customer value. Our study also ratifies Hollebeek’s (2013) study, where researchers suggest that a hedonic positioning involving empowered and engaged customers be followed to derive optimum value from customer engagement initiatives.

Our findings are also in line with several other studies that believe in a system-oriented value generation process being a dynamic representation of customer engagement (Jaakkola & Alexander, 2014; Hollebeek, 2011; Chandler & Lusch, 2015). We present the theory/research contributions in Section 5.1 and the managerial implications in Section 5.2.

5.1 Theory/Research Contributions

Firstly, the cluttered CEB and customer value literature has been distinguished by incorporating SD logic and approach/inhibition theories in evaluating the impact of empowerment and engagement behaviours on customer value in the service industry. These theories have not been tested in the context of financial services. Secondly, the study considers customer empowerment as an antecedent to CEB, and also CEB as the moderator, which has not been examined before. Thirdly, it also provides conceptual clarification by operationalizing and validating CEB as a formative higher-order construct formed by four dimensions such as customers’ social media influence, form/modality, scope, and channel of engagement using a variance-based SEM method.

Our findings suggest that customer empowerment has a strong beneficial impact on CEBs as well as customer value, as proposed by the approach/inhibition theory. The current paper empirically tests this hypothesis in the context of the FinTech industry and reinforces the notion that customer empowerment affects reward perception (customer value), which is mediated by the approach/inhibition mechanism. Customers who are empowered are more approachable, communicate their ideas or opinions, and exhibit more positive emotions. A high degree of power (here, empowerment) defined by the availability of resources or physical comfort but less intervention from others to obtain prospective rewards (say, customer value) activates the approach system (namely CEBs) (Keltner et al., 2003). Low power, on the other hand, initiates an inhibitory system that diminishes consumer value.

The present study, from empirical testing, supports the SD logic perspective by observing a positive effect of CEB on customer value in the context of the FinTech industry in India. The SD logic focuses on a customer-centric approach, in which the customer serves as both an operant resource and a value co-creator participating in a number of real-time networks. Engaged customers contribute to co-creating value in triadic and intricate social networks and virtual brand communities by spreading e-WOMs. Academicians and researchers could use the findings of the present study to create and analyse a customer interaction model that may include numerous other antecedents and consequences unique to the industry under investigation.

5.2. Managerial Implications

This paper gives FinTech managers and engagement marketing professionals in the FinTech sector guidance to design and develop strategies for empowerment and engagement that can create customer value. Customers with reduced empowerment, according to approach/ inhibitory theory, do not express their opinions or e-WOMs and self-censor by activating an inhibition process that limits customer value. Therefore, the present study proposes that firms need to be customer-centric and establish processes and practices around empowering their customers. It requires establishing and sustaining a social media community in which customers may freely share their opinions, reviews and remarks. FinTech firms need to technologically empower customers to boost CEB. There are various ways in which a FinTech firm can empower its customer base. Once onboarded, the apps need to be well-organized, and transparent. Apart from an easy interface, the payment app needs to include various amenities such as the ones associated with shopping convenience, POS (point-of-sale) payments, mobile recharges, sending and receiving money, utility bill payments (e. g., electricity and water bills), buy and sell gold, e-commerce payments and the like. An easy app interface helps all age groups to comprehend the features and also older cohorts who may be onboarding for the first time. Moreover, the study results authorize that the engagement of a customer depends on the app’s relationship management technology, which is one of the dimensions of customer empowerment. Hence, as part of the app’s relationship management technology, customers need to have access to platforms to interact with the firm and other users of the app. There should be adequate information and platforms to report service deterioration, slow downloads or vague product information.

FinTech start-ups must identify customers’ contributions achieved through these empowerment mechanisms. Further, customers’ contributions must be valued and rewarded. Customers feel more empowered when a FinTech company regularly evaluates their ideas, suggestions and feedback, recognizes them for their input, and adapts the app and service to meet their demands. Acknowledging, implementing and rewarding customer contributions this way could create more engaged customers in the FinTech industry time after time.

When the firm implements customers’ suggestions and recommendations, customers perceive themselves to be part of the service delivery and development process. These empowered customers could further foster engagement behaviours in the form of positive word of mouth and reviews in the community boosting the customer empowerment–CEB and customer empowerment–customer value associations. Most notably, empowered customers are more likely to assume that they can influence the development of products or services, which increases their desire to work with service providers and create knowledge value. Consumers who are knowledgeable, empowered, and engaged can thus create value for both businesses and customers strengthening the bond of customer empowerment-CEB-customer value. Furthermore, engaging the empowered customer by pull strategies such as feedback and reward systems may save on the marketing budget, which is otherwise being spent on push marketing such as promotional activities.

According to the SD logic, companies are required to engage with customers over a variety of platforms while employing an agile and long-term strategy for creating value. FinTech firms must devise a variety of systems to collect customer data, as well as leverage user feedback and suggestions to improve their product or service. Facilitating and rapidly closing the loop on consumer demands and feedback could foster trust and positive word of mouth and reviews in the community. The firm needs to provide all possible avenues to customers such as discussion forums, company webpages and social media pages to share their experiences and to make suggestions spontaneously. The existing customer communities need to be redesigned in a way that can foster open dialogue to understand and solve customers’ problems mutually.

6. Limitations, Future Research Agenda and Conclusion

This empirical study was limited to customers of FinTech apps dealing with payment and personal advisory services. Hence there is further scope to include other FinTech apps dealing with lending and InsureTech services. Future researchers could combine a quantitative approach with a qualitative one to capture subjective dimensions of empowerment and engagement. Congruently, the study could be undertaken for other context-based factors, other service-oriented industries such as media, healthcare, tourism and hospitality, and other emerging economies/geographies. A longitudinal study could prove fruitful to examine empowerment and engagement perceptions as they keep evolving through the COVID-19 pandemic. The study outcomes provide academicians and researchers valuable inputs to design and analyse a customer engagement model with several other antecedents and outcomes specific to the industry under study.

Positive engagement behaviours are manifested in e-WOMs, reviews and testimonials and are reciprocated by empowered customers. This is one of the few studies in the FinTech industry to validate CEB as a second order construct with its four lower-order constructs (Customers’ Social Media Influence, Scope, Form/Modality, Channel). The study also proves empirically that customer empowerment increases customer value generation both directly and indirectly during the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, it advises FinTech companies to take a systemic and individualised strategy that involves customers, enterprises, and online networks. The technological, marketing and personalization mechanisms discussed contribute to enriching the indirect relationship paths where CEB mediates the relationship between empowerment and customer value. They also assist in boosting the direct relationships of customer empowerment influencing CEB and empowerment creating customer value in the long run. These strategies can foster and systematically create engaging behaviours to create value for customers with customer empowerment behaviour as a prerequisite in an emerging FinTech market.

References

Anderson, C., & Berdahl, J. L. (2002). The Experience of Power: Examining the Effects of Power on Approach and Inhibition Tendencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1362–1377. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1362

Barari, M., Ross, M., Thaichon, S., & Surachartkumtonkun, J. (2021). A meta‐analysis of customer engagement behaviour. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), 457–477.

Bhat, S. A. & Darzi, M. A. (2016). Customer relationship management: An approach to competitive advantage in the banking sector by exploring the mediational role of loyalty. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 34(3), 388-410. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-11-2014-0160

Bonsu, S. K., & Darmody, A. (2008). Co-creating Second Life: Market Customer Cooperation in Contemporary Economy. Journal of Macromarketing, 28(4), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146708325396

Chandler, J. D., & Lusch, R. F. (2015). Service Systems: A Broadened Framework and Research Agenda on Value Propositions, Engagement, and Service Experience. Journal of Service Research, 18(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670514537709

Chandler, J. D., & Vargo, S. L. (2011). Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange. Marketing Theory, 11(1), 35–49.

Chih-Pei, H. U. & Chang, Y. Y. (2017). John W. Creswell, Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Journal of Social and Administrative Sciences, 4(2), 205–207.

de Matos, C. A., & Rossi, C. A. V. (2008). Word-of-Mouth Communications in Marketing: A meta-Analytic Review of the Antecedents and Moderators. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(4), 578–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-008-0121-1

de Oliveira Santini, F., Ladeira, W. J., Pinto, D. C., Herter, M. M., Sampaio, C. H., & Babin, B. J. (2020). Customer engagement in social media: A framework and meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(6), 1211–1228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00731-5

Diamantopoulos, A. & Winklhofer, H. M. (2001). Index Construction with Formative Indicators: An Alternative to Scale Development. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 269- 277.

Ernst & Young (2017). EY FinTech Adoption Index – The rapid emergence of FinTech. https://www.ey.com/en_in/ey-global-fintech-adoption-index, FILE/ ey-global-fintech-adoption-index-2019.pdf (Accessed 14 September 2021)

Flavián, C., Ibáñez-Sánchez, S., & Orús, C. (2019). The impact of virtual, augmented and mixed reality technologies on the customer experience. Journal of Business Research, 100, 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.050

Glavee-Geo, R., Shaikh, A. A., Karjaluoto, H., & Hinson, R. E. (2019). Drivers and outcomes of consumer engagement: Insights from mobile money usage in Ghana. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 33(1), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-11-2017-0286

Goyal, E., & Srivastava, S. (2015). Study on Customer Engagement Model-Banking Sector. SIES Journal of Management, 11(1), 51-58.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Hair, J. F, Hult, T., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M., (2019). Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2018-0665

Han, X., Fang, S., Xie, L. & Yang, J. (2019). Service fairness and customer satisfaction: Mediating role of customer psychological empowerment. Journal of Contemporary Marketing Science, 22(4), 482–498. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCMARS-01-2019-0003

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-based Structural Equation Modelling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2012). Using Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in Advertising Research: Basic Concepts and Recent Issues. In S. Okazaki (Ed.), Handbook of Research on International Advertising Edward Elgar Publishing.

Henson, R. K. (2001). Understanding Internal Consistency Reliability Estimates: A Conceptual Primer on Coefficient Alpha. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34(3), 177–189.

Hoang, D. P. (2019). The central role of customer dialogue and trust in gaining bank loyalty: An extended SWICS model. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(3), 711–729. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-03-2018-0069

Hollebeek, L. D., Sharma, T. G., Pandey, R., Sanyal, P., & Clark, M.K. (2022). Fifteen years of customer engagement research: A bibliometric and network analysis. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(2), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2021-3301

Hollebeek, L. (2011). Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 19(7), 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2011.599493

Hollebeek, L. D. (2013). The Customer Engagement/Value Interface: An Exploratory Investigation. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 21(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2012.08.006

Hulland, J. (1999). Use of Partial Least Squares (PLS) in Strategic Management Research: A Review of Four Recent Studies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(2), 195–204. https://doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(199902)20:2<195::aid-smj13>3.0.co;2-7

Hur, S. (2019). How Brand Empowerment Strategies Affect Consumer Behavior: From A Psychological Ownership Perspective [PhD dissertation, University of Tennessee]. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5465

Jaakkola, E., & Alexander, M. (2014). The Role of Customer Engagement Behavior in Value Co-Creation: A Service System Perspective. Journal of Service Research, 17(3), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670514529187

Jaakkola, E., & Hakanen, T. (2013). Value Co-creation in Solution Networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 42(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.11.005

Jarvis, C. B., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2003). A Critical Review of Construct Indicators and Measurement Model Misspecification in Marketing and Consumer Research. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(2), 99–218.

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110(2), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.265

Kumar, V., Aksoy, L., Donkers, B., Venkatesan, R., Wiesel, T., & Tillmanns, S. (2010). Undervalued or Overvalued Customers: Capturing Total Customer Engagement Value. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375602

Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2016). Competitive Advantage through Engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(4), 497–514. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0044

Lee, I., & Shin, Y. J. (2018). Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Business Horizons, 61(1), 35–46. https:///doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2017.09.003

Lemon, K. N., Rust, R. T., & Zeithaml, V. A. (2001). What Drives Customer Equity?. Marketing Management, 10(1), 20–25.

Minazzi, R. (2015). Social Media Marketing in Tourism and Hospitality. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Moe, W. W., & Trusov, M. (2011). The Value of Social Dynamics in Online Product Ratings Forums. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(3), 444–456. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.48.3.444

Moliner-Tena, M. A., Monferrer-Tirado, D., & Estrada-Guillén, M. (2019). Customer engagement, non-transactional behaviors and experience in services: A study in the bank sector. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 37(3), 730–754. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-04-2018-0107

Moliner, M. Á., Monferrer-Tirado, D. & Estrada-Guillén, M. (2018). Consequences of customer engagement and customer self-brand connection. Journal of Services Marketing, 32 (4), 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-08-2016-0320

Morrongiello, C., N’Goala, G., & Kreziak, D. (2017). Customer Psychological Empowerment as a Critical Source of Customer Engagement. International Studies of Management & Organization, 47(1), 61–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2017.1241089

Muniz, A. M. & O’guinn, T. C. (2001). Brand Community. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(4), 412–432.

Pansari, A., & Kumar, V. (2017). Customer engagement: the construct, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0485-6

Pires, G. D., Stanton, J., & Rita, P. (2006). The internet, consumer empowerment and marketing strategies. European Journal of Marketing, 40(9/10), 936–949. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560610680943

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569.

Porter, C. E., Donthu, N., MacElroy, W. H., & Wydra, D. (2011). How to Foster and Sustain Engagement in Virtual Communities. California Management Review, 53(4), 80–110. https://doi.10.1525/cmr.2011.53.4.80

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation Experiences: The Next Practice in Value Creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

Prentice, C., Wang, X., & Loureiro, S. M. C. (2019). The influence of brand experience and service quality on customer engagement. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50, 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.04.020

Reserve Bank of India (2021). FinTech: The Force of Creative Disruption. RBI Bulletin November. Available at https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/Bulletin/PDFs/7FINTECHEED4C43FC31D43C9B9D7F8F31D01B08E.PDF

Rust, R. T., Lemon, K. N., & Zeithaml, V. A. (2004). Return on Marketing: Using Customer Equity to Focus Marketing Strategy. Journal of Marketing, 68(1),109–127.

Sashi, C. M. (2012). Customer engagement, buyer-seller relationships, and social media. Management Decision, 50(2), 253-272.https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211203551

Sheth, J. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: Will the old habits return or die?. Journal of Business Research, 117, 280–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.059

Shin, H., Perdue, R. R., & Pandelaere, M. (2020). Managing Customer Reviews for Value Co-creation: An Empowerment Theory Perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 59(5), 792–810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519867138

Strauss, J., & Frost, R. (2006). E-Marketing (6th international edition). Upper Saddle River, NY: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Turnquist, C. (2004). VP value chain services, Syntegra and Stan Elbaum, VP. Strategic Solutions, Aberdeen. Available at www. retailsystems. com/index. cfm.

van Doorn, J., Lemon, K. N., Mittal, V., Nass, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P., & Verhoef, P. C. (2010). Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. Journal of Service Research, 13(5), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375599

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/30161971

Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., & Morgan, R. M. (2012). Customer Engagement: Exploring Customer Relationships beyond Purchase. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 20 (2), 122–46. https://10.2753/mtp1069-6679200201

Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., Dalela, V., & Morgan, R. M. (2014). A Generalized Multidimensional Scale for Measuring Customer Engagement. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 22(4), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679220404

Wu, L., A. S., Mattila, C. Y., Wang, & Hanks, L. (2016). The Impact of Power on Service Customers’ Willingness to Post Online Reviews. Journal of Service Research, 19(2), 224–38. https://10.1177/1094670516630623

Youssef, Y. M. A., Johnston, W. J., Abdel Hamid, T. A., Dakrory, M. I., & Seddick, M. G. S. (2018). A customer engagement framework for a B2B context. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(1), 145–152. https://doi:10.1108/jbim-11-2017-0286