Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2023, vol. 14, no. 2(28), pp. 242–259 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2023.14.90

Impacts of Store Trust Antecedents

on Willingness to Disclose Personal Data

in Online Shopping

Sigitas Urbonavicius (corresponding author)

Vilnius University, Lithuania

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4176-2573

sigitas.urbonavicius@evaf.vu.lt

Mindaugas Degutis

Vilnius University, Lithuania

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5464-052X

mindaugas.degutis@evaf.vu.lt

Ignas Zimaitis

Vilnius University, Lithuania

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0067-6513

ignas.zimaitis@evaf.vu.lt

Vatroslav Skare

University of Zagreb, Croatia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0541-4187

vskare@efzg.hr

------------------------------------------------------

Acknowledgement: this project has received funding from the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT), Agreement No S-MIP-19-19

------------------------------------------------------

Abstract. Personal data disclosure is crucially important to modern business, and specifically – to online stores. It is largely predicted by the willingness to disclose personal data that significantly varies among emerging economies due to impacts of numerous factors. One of the important factors that impacts willingness to disclose personal data in online shopping is trust in an online store. However, the importance of trust in a store partly occurs because it mediates effects of other antecedents. This study conceptualizes three groups of important antecedents: personal, infrastructural and store-related factors. The study tests indirect effects of the most typical factors from each group: general trust (personal factor), legal regulations (infrastructural factor) and presence of an off-line selling channel in addition to the online channel offered by a store (e-store factor) on willingness to disclose personal data online. The findings show that all these factors, mediated by store trust, have significant positive effects on willingness to disclose personal data. The findings contribute to the knowledge of the groups of factors that impact willingness to disclose personal data online and help to set directions for future research.

Keywords: willingness to disclose personal data, store trust, perceived regulatory effectiveness, selling channels

Received: 5/7/2022. Accepted: 6/3/2023

Copyright © 2023 Sigitas Urbonavicius, Mindaugas Degutis, Ignas Zimaitis, Vatroslav Skare. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Trust and privacy concerns are two important factors that largely predetermine willingness to disclose personal data in online shopping (Swani et al., 2021; Chen, 2022). The levels of these factors and their interactions are different among countries due to their technological, cultural and economic characteristics (Markos et al., 2017; Robinson, 2017; Tikhomirova et al., 2021).

Willingness of online buyers to disclose personal data is an important topic on the agenda of numerous researchers (Gupta et al., 2010; Pizzi & Scarpi, 2020; Urbonavicius et al., 2021). The issue is often linked with privacy paradox and addressed from numerous theoretical perspectives (Gerber et al., 2018; Kehr et al., 2015). Numerous studies ground the research on the privacy calculus (Wang et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Fernandes & Pereira, 2021). However, social exchange theory is also increasingly applied for studies on this issue (Urbonavicius et al., 2021; Zimaitis et al., 2022). The use of social exchange theory (SET) as a grounding theory has opened several new research avenues in addition to the ones researched on other theoretical bases. Since social exchange theory considers two types of social exchange (reciprocal and negotiated; Molm, 2003), this allows us to simultaneously consider various types of online activities. Particularly, it helps to link the disclosure behaviours in social networking (which represents a case of reciprocal exchange) and e-shopping, which is a case of negotiated exchange (Urbonavicius et al., 2021). Additionally, the way how social exchange theory considers benefits of social exchanges helps to extend analysis about the importance of perception of benefits of data disclosure (Cao et al., 2022).

One of the key observations of these studies includes rather firm evidence about the importance of trust factor that often takes a more concrete form such as trust in a store (here and further specifically meaning the case of an online store), a platform or internet site (Wang & Emurian, 2005; Godoy et al., 2015; Bansal et al., 2016). Differing from a dispositional factor of propensity to trust (also named general trust, trustfulness), trust in a store is a typical situational factor that prevails in situations of personal data disclosure (Delgado-Márquez et al., 2012; Masur, 2019; Kim & Kim, 2021). Although the strong positive impact of trust in a store on willingness to disclose personal data has been extensively analysed, the sources of this trust remain presenting a noticeable research gap. This aspect is important for data disclosure studies, since the antecedents of store trust have an indirect (mediated by store trust) impact on willingness to disclose personal data, which remains largely underexplored.

In order to address this research gap, the three sources of the trust in a store are considered in the study; they include personal factors, infrastructural factors and factors that are linked with a store itself. The personal aspect refers to the intrinsic characteristics of a person that have direct impact on their trust in various processes, individuals and objects, including stores. This group mainly includes variables of dispositional nature, such as personality traits and psychographic characteristics (Bansal et al., 2016; Robinson, 2017). Among them, dispositional propensity to trust is the one that is exceptionally important, having positive impact on trust in a store (Moody et al., 2014; Degutis et al., 2021). Infrastructural factors refer to the context, characteristics of an environment in which both a potential buyer and a store interact (Masur, 2019). Among them, legal regulations, procedures and institutions that assure safety of data use are among the most important factors (Pal et al., 2020; Mutimukwe et al., 2020). Finally, trust in a store comes from the characteristics of the store itself. Though the number and variety of these characteristics may be very large, one aspect is rather universal: an e-store may operate only online or may have physical outlets that make its physical presence in a market more tangible (Wang et al., 2021). This is important for buyers to involve themselves in a cross-channelling behaviours, and contribute to the overall sense of tangibility of a store. Since tangible elements are important sources of trust in services (including ones of retailing) (Lian, 2021; Toufaily et al., 2013), the presence of a physical outlet may substantially contribute to the trust in a store. However, this aspect remains heavily under-researched, and presents a second research gap addressed by the current study.

The study addresses the above-mentioned research gaps by modelling the impact of store trust on willingness to disclose personal data together with the three antecedents of store trust: propensity to trust, perceived regulatory effectiveness and presence of an off-line channel used by a store. The aim is to find indirect impacts of the three antecedents of the store trust on willingness to disclose personal data in online shopping and contribute to the knowledge of the importance of the personal, infrastructural and store factors in this regard.

1. Literature Review

1.1 Theoretical Grounding of Willingness to Disclose Personal Data

The willingness to disclose personal data is a variable that is typically understood as the main predictor of the subsequent disclosure of personal data. Even considering the known privacy paradox (Barth & de Jong, 2017; Gerber et al., 2018), this makes willingness to disclose personal data a very important factor in studies that are not assessing the factual disclosure of personal information (Parker & Flowerday, 2021).

There are numerous very strong arguments why willingness to disclose personal data is a situational factor (Masur, 2019). This is mainly grounded with the arguments that willingness to disclose personal data represents a reaction of buyers to a number of circumstances that are present at the moment of data disclosure, and therefore is driven by a specific situation (Anic et al., 2018). In this sense, willingness to disclose personal data often becomes very similar to intention to disclose personal data, since the latter is even more tied to a particular situation (Wang et al., 2016). Despite this, we believe that willingness to disclose personal data has more characteristics of an attitudinal variable than intention (Robinson, 2018), as the willingness to disclose personal information occurs not only in very precisely defined situations, but also in more general instances, when the circumstances of data disclosure are not very clear (Urbonavicius, 2020; Aboulnasr et al., 2022). Additionally, the variable of willingness to disclose personal data itself includes several aspects that might be assessed and analysed separately, which justifies the specificity of this factor (Degutis et al., 2020).

Analysis of the willingness to disclose personal data roots from a broader field of privacy research and is assessed on the basis of several theoretical grounds (Li, 2012). There were attempts to use theories ranging from Theory of Planned Behaviour (Keith et al., 2015), Regulatory Focus Theory (Wirtz & Lwin, 2009) or Equity Theory (Barto & Guzman, 2018) to privacy-specific approaches such as Privacy Calculus (Kehr et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016; Parker & Flowerday, 2021). All of them contributed to the broadening knowledge on the issue, however, all of them also included limitations that are linked with the specifics of the theories themselves. For instance, the widely employed approach of Privacy Calculus was often criticized for the over-estimation of rationality of buyers (Kehr et al., 2015). Recently, privacy issue started to be more frequently analysed on the basis of social exchange theory (King, 2018; Urbonavicius et al., 2021; Zimaitis et al., 2022). Among other aspects of privacy, studies that use this background strongly consider relationship between factors of trust and willingness to disclose data, since trust is a key factor employed by social exchange theory (Bernerth & Walker, 2009).

Analysis of willingness to disclose personal data includes assessment of its antecedents and the mechanism how they interact (Robinson, 2018; Skare et al., 2020; Urbonavicius et al., 2021). Typically, an important role among them belongs to the trust-linked factors that reflect propensity to trust (general trust, trustfulness) (Moody et al., 2014; Zimaitis et al., 2020; Jadil et al., 2022) or more situational types of the trust, such as trust in a store, a platform, or a website (Cho, 2006; Delgado-Márquez et al., 2012; Castaldo et al., 2016). Trust-related factors become even more important when a study is based on social exchange theory, since this theory largely concentrates on the development of trust on the basis of interactions among exchange partners (Molm et al., 2000).

1.2 Trust in a Store as a Factor of Data Disclosure

The factor of trust in a store stems from the general institutional trust that is found to impact intention to disclose personal data both directly and indirectly (Kehr et al., 2015). The trust may be specified as being linked not only with a store (e-store), but also to an internet platform or a site (Jarvenpaa et al., 2000; Wang & Emurian, 2005; Li, 2014). Trust or distrust in a store reflects the relationship of a person with a store and is based on accumulation experience of interactions (Murphy, 2003). This is matched with the concept of reciprocal exchanges, as suggested by social exchange theory (Molm et al., 2000). These reciprocal relationships reach an equilibrium in terms of interactions (Lwin et al., 2007), and the level of the developed trust is partially expressed in a level of willingness to disclose personal data to the store (Cho, 2006).

In online commerce, a store is an essential exchange partner of a buyer for a transaction to occur (Urbonavicius, 2023), therefore the importance of this type of trust is very high. Trust in a store is seen as an important variable in analysis of various types of commerce and is often considered as an important mediator (Guenzi et al., 2009; Asma & Afreen, 2022; Chaudhuri & Ligas, 2016). Some evidence on store trust in social shopping shows its importance on shopping intentions (Yasa & Cop, 2022; Wu et al., 2023), but the empirical evidence of its direct impact on willingness to disclose personal data in online shopping remains rather scarce and limited (Degutis et al., 2021). This requires to develop and test the hypothesis that store trust has positive impact on willingness to disclose personal data in online shopping:

H1: Store trust positively impacts willingness to disclose personal data to an online store.

1.3 Personal Sources of Store Trust: The Role of Propensity to Trust

It is well agreed that personal characteristics of consumers impact their data disclosure to internet stores (Kolotylo-Kulkarni et al., 2021). The group of personal characteristics is wide and typically includes personality traits that generally impact consumers interactions as well as engagement with brands and institutions (Hollebeek et al., 2022). It is empirically confirmed that personality traits of extroversion, agreeableness, emotional instability, conscientiousness and intellect influence ability to trust a store (Bansal et al., 2016). Additionally, the group of personal characteristics includes experience (positive and negative), online competency, innovativeness, and more (Kolotylo-Kulkarni et al., 2021; Kim & Kim, 2018).

When social exchange theory is employed, the propensity to trust is considered among the most important predictors of other types of trust that are included into an analysis (Kim & Kim, 2021). According to this theory, trust towards a store develops gradually on the basis of reciprocal interactions between a buyer and a store (Delgado-Márquez et al., 2012). The interaction between the two parties of the exchange is comparable to the reciprocal social exchange between people: the initial trigger is made by the propensity to trust, and then the trust in a partner develops based on the success of the interactions (Bernerth & Walker, 2009).

The outcome of the interactions with a store is not just the increase of trust in it; the store trust itself further impacts various outcomes, ranging from the increase of willingness to disclose personal data to the store to developments of loyalty to it (Swoboda & Winters, 2021; Zimaitis et al., 2022). This way propensity to trust impacts other forms of trust, and these mediate its effects towards the willingness to disclose personal data (Heirman et al., 2013). There is empirical evidence on how propensity to trust impacts store trust (Yasa & Cop, 2022), but the knowledge about its impact on willingness to disclose personal data with mediations of store trust is scarce. Therefore, we propose that propensity to trust exerts positive indirect (mediated by store trust) impact on willingness to disclose personal data in e-shopping:

H2: Propensity to trust has a positive indirect (mediated by store trust) effect on willingness to disclose personal data to an online store.

1.4 Infrastructural Sources of Store Trust: Importance of Legal Aspect

We define infrastructural sources of trust as the contextual factors that impact both participants of the online data exchange. In the case of analysis of personal data disclosure, the most important factors include various forms of legal regulations, policies and institutions that implement them together with consumer perceptions about their effectiveness. The concept of this group of variables roots from “external” institutional trust (Kehr et al., 2015). These regulations typically take the form of legal acts, and the most typical examples of such acts would be General Data Protection Regulation (EU) or Data Protection Act (USA) (Goddard, 2017). The presence of strict regulatory environments develops additional trust in institutions that work under these regulations (Zhang et al., 2020). This way legal regulations work as a supporting factor for the assurance of individual institutions, including stores (Xu et al., 2011). Institutions that work under these legal regulations develop their own policies and procedures that match the requirements (Weydert et al., 2019). All these privacy regulation-linked measures result in consumer’s perceptions about the effectiveness of privacy regulation (Mutimukwe et al., 2020). These perceptions impact store trust, and consequently – the willingness to disclose personal data to a store. Based on this, we propose:

H3: Perceived regulatory effectiveness has a positive indirect (mediated by store trust) effect on willingness to disclose personal data to an online store.

1.5 Store Characteristics and Store Trust: The Presence of an Alternative Channel

Trust in service providers (including online stores) is developed not only on the basis of the personal characteristics of buyers, infrastructural factors, but also based on the characteristics of the stores themselves. The characteristics of online stores range from minor specificities of their web-pages and procedures to numerous more specific tangible and intangible attributes (Castaldo et al., 2016; Yasa & Cop, 2022). Among them probably the most noticeable tangible attribute is the presence (or absence) of a traditional selling channel offered by an e-store in addition to its online channel (Verhagen et al., 2019). The presence of another channel may be very practical from a buyer perspective: for example, it helps to consider a ‘buy online/pickup in‐store’ option (Song et al., 2020). Additionally, this allows buyers to use the most suitable purchasing channel, which is heavily different in various countries and across various products (Rossolov et al., 2021). From a store perspective, the online channel may interact with the off-line channel in many ways; however, its presence may increase not just total, but also online sales (Wang & Goldfarb, 2017; Grosso et al., 2020). Partly, this happens because consumer trust towards stores is different when so called ‘pure click’ and ‘click-and-brick’ retailers are considered (Toufaily et al., 2013). The presence of the two channels not only generates different levels of trust to themselves, but also has trust transfers occurring between the channels and increases total trust in a store that employs two channels (Xiao et al., 2019). This results in differences of willingness to disclose their personal data to retailers that have one versus two sales channels, since the latter case includes an important characteristic of a store tangibility (Pallant et al., 2022). Therefore, the hypothesis is:

H4: The number of selling channels used by a store has a positive indirect (mediated by store trust) effect on willingness to disclose personal data to an online store.

2. Method

2.1 Research Model and Measures

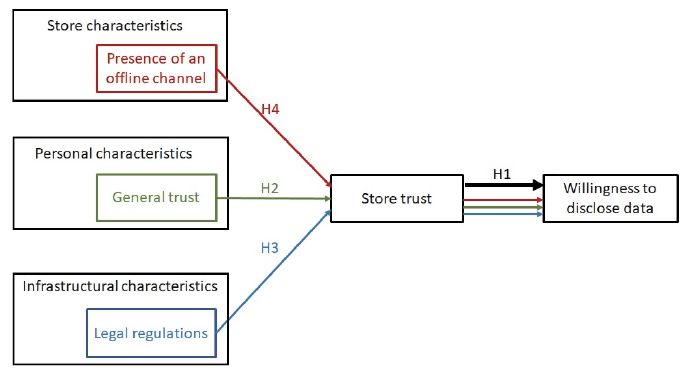

The research model is aimed to test direct effect of store trust on willingness to disclose personal data online and three indirect effects mediated by store trust. In order to test them, the first hypothesis tests the direct impact of store trust on the willingness to disclose personal data (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Research Model

Following this, the model tests indirect effects of three groups of antecedents; each of them is represented by one important variable of that group. As it is suggested by social exchange theory, trust is among the most important personal characteristics, therefore the most general form of it (propensity to trust) represents that group. Since it is very important how privacy and data disclosure are legally regulated, infrastructural characteristics are represented by perception about legal regulation and its implementation effectiveness. Store characteristics are represented by a tangible and easily noticeable attribute of an online store: the presence (or absence) of the second (offline) selling channel that a store offers to its buyers.

In order to measure the variables included in the model, the study employed known scales that have been successfully used to measure them in the past. Propensity to trust was assessed with the four-item scale (Frazier et al., 2013). The effects of legal regulations generate certain perceptions of buyers about their effectiveness (Mutimukwe et al., 2020); therefore, the scale of perceived regulatory effectiveness that includes three-items was employed. The scale was proposed by Lwin et al. (2007) and later used in many other studies. Trust in a store was assessed with a scale suggested and successfully used by King (2018). Willingness to disclose personal data was measured with the scale suggested by Gupta et al. (2010) and Heirman et al. (2013), later used with modifications by Robinson (2017), Urbonavicius et al. (2021) and other researchers. All modifications typically differed just in the number of the types of personal data included. This study included six items that referred to the most frequently required types of personal data: first name, last name, age, home address, mobile phone number and e-mail address. All items of all above mentioned scales were assessed with a 7-point Likert scale (see Appendix).

The measure of the number of channels was obtained indirectly. Half of the sample received a scenario that suggested that they have a possibility to purchase durable products in an online store that operates only online. Another half of the sample received the same scenario except that they were informed that the online store also has a physical store that is located in a destination that is convenient to the respondent. The two situations were coded, thus resulting in a binary variable, where 1 means presence of just online selling channel, and 2 – presence of the online and off-line channels for selling goods.

2.2 Data

Data was collected using a representative survey in Lithuania. The initial sample included 1000 respondents, but after elimination of 36 unengaged respondents, the analysis was performed on the basis of data from 964 questionnaires. In this sample, 41.1% were males, and 59.9% females. They were aged from 18 to 65; 30.0% of respondents belonged to the group aged 18–34; 31.8% represented the age group 35–49, and 38.2% were between 50 and 65 years of age. 50.5% of the respondents answered the survey being informed that a store uses only online channel, while 49.5% – that a store uses both online and offline channels.

3. Analysis

3.1 Reliability and Validity

Since the study used known and well tested scales, exploratory factor analysis was not needed, and scale parameters were assessed on the basis of confirmatory factor analysis. The variable that measured the number of channels used by a store was assessed with one item, therefore was not included in this analysis.

The measurement model had satisfactory parameters of fit: CMIN/DF=4.168; TLI=0.960; CFI=0.968; RMSEA =0.057; PCLOSE=0.026 (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012). All factors showed good convergent validity (loadings averaged at above 0.7); covariances between them below 0.8 showed good discriminant validity (the highest covariance was 0.55). Additional tests of validity and reliability were also satisfactory. Composite reliability was higher than 0.70, which was appropriate (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012). The average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded 0.50, satisfying the criterion of Fornell and Larcker (1981); squared AVE for each factor was higher than the correlation values of that factor (Table 1).

Table 1

Validity and Reliability of Factors

|

Factors |

CR |

AVE |

ST |

PRE |

PT |

WTD |

|

Store trust (ST) |

0.882 |

0.789 |

0.888 |

|

|

|

|

Perceived Regulatory Effectiveness (PRE) |

0.887 |

0.724 |

0.518 |

0.851 |

|

|

|

Propensity to trust (PT) |

0.890 |

0.670 |

0.280 |

0.249 |

0.818 |

|

|

Willingness to disclose personal data (WTD) |

0.889 |

0.573 |

0.550 |

0.352 |

0.177 |

0.757 |

Note. CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted; ST = store trust; PRE = perceived regulatory effectiveness; PT = propensity to trust; WTD = willingness to disclose personal data.

Common latent factor test came back positive; therefore, the common latent factor was considered for further modelling. The model with consideration of a common latent factor had a good fit (CMIN/DF=2.603; TLI=0.980; CFI=0.987; RMSEA=0.041; PCLOSE=0.980). Based on that, factors for further analysis were imputed including the common latent factor.

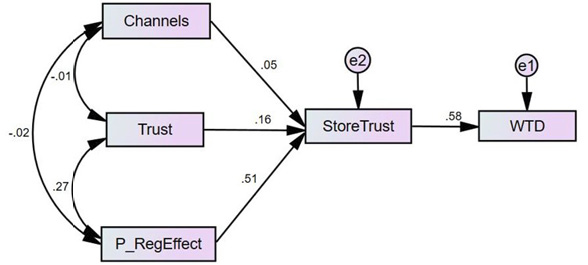

3.2 Tests of Hypotheses

The fit of the structural model was satisfactory: CMIN/DF=4.370; TLI=0.961; CFI=0.988; RMSEA =0.059; PCLOSE=0.271 (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012). All direct relationships between factors in the model were significant at level p≤0.001, the impact of channels on the store trust – at level p≤0.01. Therefore, all relationships of the structural model (Figure 2) were used for the tests of hypotheses.

Figure 2

Structural Model

Tests of hypotheses were performed on the basis of the standardised regression weights.

H1 predicted that the store trust positively impacts willingness to disclose personal data; this was aimed to re-assess the relationship that was observed in some former studies. The hypothesis was confirmed (β=0.584; p≤0.001), which provided basis for further tests of indirect effects, mediated by store trust.

Three other hypotheses tested indirect impacts of propensity to trust, perceived regulatory effectiveness and the number channels, used by a store on willingness to disclose personal data. The results of the tests are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2

Standardised Indirect Effects

|

Indirect effects |

β |

|

Propensity to trust → Store trust → Willingness to disclose personal data |

0.096*** |

|

Perceived Regulatory Effectiveness → Store trust → Willingness to disclose personal data |

0.300*** |

|

Channels → Store trust → Willingness to disclose personal data |

0.029* |

Note. ***significant at p≤0.001; *significant at p≤0.01

Hypothesis H2 predicted that propensity to trust has a positive indirect effect on willingness to disclose personal data. This indirect effect included the impact of propensity to trust on store trust (β=0.164; p≤0.001) and the impact of store trust on willingness to disclose personal data (β=0.584; p≤0.001). Total indirect effect (β=0.096; p≤0.001) was significant and positive, as predicted, therefore, H2 was confirmed.

Hypothesis H3 formulated the presence of positive indirect relationship between perceived regulatory effectiveness and willingness to disclose personal data in e-shopping. The effect included the impact of perceived regulatory effectiveness on store trust (β=0.514; p≤0.001) and the impact of store trust on willingness to disclose personal data (β=0.584; p≤0.001). Total indirect effect (β=0.300; p≤0.001) was significant and positive, and H3 was confirmed.

Hypothesis H4 predicted the positive indirect effect of the number of channels used by a store on willingness to disclose personal data. This indirect effect included the impact of channels on store trust (β=0.049; p=0.061) and the impact of store trust on willingness to disclose personal data (β=0.584; p≤0.001). The p-value of the relationship between channels and store trust is understandable because of the bivariate nature of the predictor and does not hinder assessing the indirect effect of channels on WTD. This indirect effect (β=0.029; p≤0.01) was significant and positive, as predicted, therefore H4 is confirmed.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The current study was built on the findings of the earlier studies and aimed to analyse sources of trust in a store and their contribution to willingness to disclose personal data that is mediated by store trust. There are several valuable elements in the findings.

First, the study confirmed the importance of the store trust on willingness to disclose personal data in an online store. The relationship was positive and strong, which is in line with earlier findings of Degutis et al. (2021). This shows the robustness of this finding and leads to a conclusion that store trust is an important antecedent of willingness to disclose personal data in online buying, which is important both theoretically and as a managerial implication.

Next, the conceptualization of the three groups of factors that impact store trust (personal, infrastructural and store-related) appeared to be relevant, since the factors of each group had significant direct influence on store trust. The general importance of a personal factor ‘propensity to trust’ in trust-linked and disclosure-linked studies was rather well justified (Murphy, 2003; Bernerth & Walker, 2009; Delgado-Márquez et al., 2012; Urbonavicius et al., 2021), but the current study extended the knowledge specifically regarding its impact on the store trust, which expands previous rather limited observations (Yasa & Cop, 2022). The knowledge about the impact of infrastructural factors (specifically – perceptions of effectiveness of regulations) on willingness to disclose personal data was even more fragmented and rarely specifically linked with the trust in a store. Therefore, this study extended the previous base of the knowledge in this regard. This has an important managerial implication that buyers pay attention to the strictness of legal regulations and the compliance of the used data collection procedures with them.

The impact of the presence of one channel versus two channels on willingness to disclose personal data was just briefly included in the earlier studies (Toufaily et al., 2013), and the knowledge about the importance of this aspect on trust in a store was very limited. The current study contributed towards filling this knowledge gap and extended the knowledge about other benefits of channel integration (Wang & Goldfarb, 2017; Verhagen et al., 2019; Rossolov et al., 2021) that could serve as a managerial implication.

However, the main aim of the current study was to assess indirect effects of the personal, infrastructural and store-linked factors on willingness to disclose personal data, considering the mediation of store trust. The findings confirmed the assumption about importance of these factor groups on willingness to disclose personal data. This suggests that all three above mentioned groups of variables are important indirect predictors of willingness to disclose personal data; their effects are mediated by store trust. This is the main input of the current study regarding understanding the roots of willingness to disclose personal data to online stores.

5. Limitations and Further Research

The current study has several limitations that could be considered in future studies. First, this study has its value because of formulating the concept of the three groups of antecedents and testing the impacts of one factor per group on store trust, which is a strong exploratory start for the direction of further studies. However, the conceptualization of the three types of factors is rather preliminary, and their importance for developing store trust can be more elaborated both theoretically and empirically.

Second, the study has measured the presence of one versus two selling channels offered by a store indirectly, using the scenario and two groups of the respondents. This was converted into a binary variable that might have lower predicting value than other latent variables, measured with well-tested scales, ranging from 1 to 7. Thus, future studies may aim to find other ways of how the presence of tangible characteristics of stores could be assessed.

Finally, the perceptions regarding the disclosure of personal data are changing rather rapidly and have various dynamics across countries. The differences occur both among highly developed countries and among countries that are less developed economically. These differences are subjected to variations in the developments of infrastructures that predetermine levels of the development online technologies, legal regulations, cultural changes and more. This offers a research avenue that would consider comparison between markets and groups of respondents that are differently involved in online activities.

References

1. Aboulnasr, K., Tran, G. A., & Park, T. (2022). Personal information disclosure on social networking sites. Psychology & Marketing, 39(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21595

2. Anic, I.-D., Budak, J., Rajh, E., Recher, V., Skare, V., & Skrinjaric, B. (2018). Extended model of online privacy concern: what drives consumers’ decisions? Online Information Review, 7(3), 43(5), 799–817. DOI: 10.1108/OIR-10-2017-0281

3. Asma, & Afreen, A. (2022). The Antecedents of Instagram Store Purchase Intention: Exploring the Role of Trust in Social Commerce. Vision – the Journal of Business Perspective, 0(0), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/09722629221133887

4. Bagozzi, R. P. & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34.

5. Bansal, G., Zahedi, F. M., & Gefen, D. (2016). Do context and personality matter? Trust and privacy concerns in disclosing private information online. Information & Management, 53(1), 1–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2015.08.001

6. Barth, S., & de Jong, M. D. T. (2017). The privacy paradox – Investigating discrepancies between expressed privacy concerns and actual online behavior – A systematic literature review. Telematics and Informatics, 34(7), 1038–1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.04.013

7. Barto, T. P., & Guzman, I. R. (2018). An equity theory view of personal information disclosure in an online transactional exchange. Revista Eletrônica de Sistemas de Informação, 17(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.21529/RESI.2018.1701002

8. Bernerth, J., & Walker, H. J. (2009). Propensity to Trust and the Impact on Social Exchange. An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 15(3), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051808326594

9. Cao, E., Jiang, J., Duan, Y., & Peng, H. (2022). A Data-Driven Expectation Prediction Framework Based on Social Exchange Theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 783116. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.783116

10. Castaldo, S., Grosso, M., Mallarini, E., & Rindone, M. (2016). The missing path to gain customers loyalty in pharmacy retail: The role of the store in developing satisfaction and trust. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 12(5), 699–712. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.10.001

11. Chaudhuri, A., & Ligas, M. (2016). The Role of Store Trust and Satisfactions in Creating Premium Prices. Marketing Management Journal, 26(1), 1–17.

12. Chen, X., Sun, J., & Liu, H. (2022). Balancing web personalization and consumer privacy concerns: Mechanisms of consumer trust and reactance. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 21(3), 572–582. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1947

13. Cho, J. (2006). The mechanism of trust and distrust formation and their relational outcomes. Journal of Retailing, 82(1), 25–35. DOI: 10.1016/j.jretai.2005.11.002

14. Degutis M., Urbonavicius S. & Skare, V. (2021), Willingness to disclose personal data in online shopping as a case of reciprocal social exchange. Proceedings of the European Marketing Academy Annual Conference, 50 (104265).

15. Degutis, M., Urbonavicius, S., Zimaitis, I., Skare, V., & Laurutyte, D. (2020). Willingness to Disclose Personal Information: How to Measure it? Engineering Economics, 31(4), 487–494. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.31.4.25168

16. Delgado-Márquez, B. L., Hurtado-Torres, N. E., & Aragón-Correa, J. A. (2012). The dynamic nature of trust transfer: Measurement and the influence of reciprocity. Decision Support Systems, 54(1), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.05.008

17. Fernandes, T., & Pereira, N. (2021). Revisiting the privacy calculus: Why are consumers (really) willing to disclose personal data online?. Telematics and Informatics, 65, 101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101717

18. Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

19. Frazier, M. L., Johnson, P. D., & Fainshmidt, S. (2013). Development and validation of a propensity to trust scale. Journal of Trust Research, 3(2), 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2013.820026

20. Gerber, N., Gerber, P., & Volkamer, M. (2018). Explaining the privacy paradox: A systematic review of literature investigating privacy attitude and behavior. Computers & security, 77, 226–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2018.04.002

21. Goddard, M. (2017). The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): European Regulation that has a Global Impact. International Journal of Market Research, 59(6), 703–705. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJMR-2017-050

22. Godoy, S., Labarca, C., Somma, N., Gálvez, M., & Sepúlveda, M. (2015). Circumventing Communication Blindspots and Trust Gaps in Technologically-Mediated Corporate Relationships: The Case of Chilean Business-to-Consumer E-commerce. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 10(2), 19–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-18762015000200003

23. Grosso, M., Castaldo, S., Li, H. A., & Larivière, B. (2020). What Information Do Shoppers Share? The Effect of Personnel-, Retailer-, and Country-Trust on Willingness to Share Information. Journal of Retailing, 96(4), 524–547. DOI:10.1016/j.jretai.2020.08.002

24. Guenzi, P., Johnson, M. D., & Castaldo, S. (2009). A comprehensive model of customer trust in two retail stores. Journal of Service Management, 20(2), 290–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230910964408

25. Gupta, B., Iyer, L. S., & Weisskirch, R. S. (2010). Facilitating Global E-commerce: A Comparison of Consumers’ Willingness to Disclose Personal Information Online in the US and India. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 11(1), 41–52.

26. Heirman, W., Walrave, M., Ponnet, K., & van Gool, E. (2013). Predicting adolescents’ willingness to disclose personal information to a commercial website: Testing the applicability of a trust-based model. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 7(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2013-3-3

27. Hollebeek, L. D., Sprott, D. E., Urbonavicius, S., Sigurdsson, V., Clark, M. K., Riisalu, R., & Smith, D. L. (2022). Beyond the Big Five: The effect of machiavellian, narcissistic, and psychopathic personality traits on stakeholder engagement. Psychology & Marketing, 39(6), 1230–1243. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21647

28. Jadil, Y., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2022). Understanding the drivers of online trust and intention to buy on a website: An emerging market perspective. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(1), 100065. DOI: 10.1016/j.jjimei.2022.100065

29. Jarvenpaa, S. L., Tractinsky, N., & Vitale, M. (2000). Consumer trust in an Internet store. Information Technology and Management, 1(1), 45–71. DOI: 10.1023/A:1019104520776

30. Kehr, F., Kowatsch, T., Wentzel, D., & Fleisch, E. (2015). Blissfully ignorant: The effects of general privacy concerns, general institutional trust, and affect in the privacy calculus. Information Systems Journal, 25(6), 607–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12062

31. Keith, M. J., Babb, J. S., Lowry, P. B., Furner, C. P., & Abdullat, A. (2015). The Role of Mobile‐Computing Self‐Efficacy in Consumer Information Disclosure. Information Systems Journal, 25(6), 637–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12082

32. Kim, D., Park, K., Park, Y., & Ahn, J. H. (2019). Willingness to provide personal information: Perspective of privacy calculus in IoT services. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.022

33. Kim, M. S., & Kim, S. (2018). Factors influencing willingness to provide personal information for personalized recommendations. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 143–152. DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.031

34. Kim, S. H., & Kim, S. (2021). Particularized Trust, Institutional Trust, and Generalized Trust: An Examination of Causal Pathways. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 33(4), 840–855.

35. King, J. (2018). Privacy, disclosure, and social exchange theory [Doctoral Dissertation. University of California, Berkeley].

36. Kolotylo-Kulkarni, M., Xia, W., & Dhillon, G. (2021). Information disclosure in e-commerce: A systematic review and agenda for future research. Journal of Business Research, 126, 221–238. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.006

37. Li, Y. (2012). Theories in online information privacy research: A critical review and an integrated framework. Decision Support Systems, 54(1), 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2012.06.010

38. Li, Y. (2014). The impact of disposition to privacy, website reputation and website familiarity on information privacy concerns. Decision Support Systems, 57, 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2013.09.018

39. Lian, J. W. (2021). Determinants and consequences of service experience toward small retailer platform business model: Stimulus–organism–response perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62, 102631. DOI: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102631

40. Lwin, M., Wirtz, J., & Williams, J. D. (2007). Consumer online privacy concerns and responses: a power–responsibility equilibrium perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(4), 572–585.

41. Markos, E., Milne, G. R., & Peltier, J. W. (2017). Information Sensitivity and Willingness to Provide Continua: A Comparative Privacy Study of the United States and Brazil. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 36(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.15.159

42. Masur, P. K. (2019). Situational Privacy and Self-Disclosure. Springer, Cham.

43. Molm, L., Takahashi, N., & Peterson, G. (2000). Risk and Trust in Social Exchange: An Experimental Test of a Classical Proposition. American Journal of Sociology, 105(5), 1396–1427. https://doi.org/10.1086/210434

44. Molm, L. D. (2003) Theoretical Comparisons of Forms of Exchange. Sociological Theory, 21(1), 1–17.

45. Moody, G. D., Galletta, D. F., & Lowry, P. B. (2014). When Trust and Distrust Collide Online: The Engenderment and Role of Consumer Ambivalence in Online Consumer behavior. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 13(4), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2014.05.001

46. Murphy, G. B. (2003). Propensity to Trust, Purchase Experience, and Trusting Beliefs of Unfamiliar E-commerce Ventures. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 6(2), 53–64.

47. Mutimukwe, C., Kolkowska, E., & Grönlund, Å. (2020). Information privacy in e-service: Effect of organizational privacy assurances on individual privacy concerns, perceptions, trust and self-disclosure behavior. Government Information Quarterly, 37(1), 101413. DOI:10.1016/J.GIQ.2019.101413

48. Pal, D., Funilkul, S., & Zhang, X. (2020). Should I Disclose my Personal Data? Perspectives from Internet of Things Services. IEEE Access, 9, 4141–4157. DOI: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3048163

49. Pallant, J. I., Pallant, J. L., Sands, S. J., Ferraro, C. R., & Afifi, E. (2022). When and How Consumers are Willing to Exchange Data with Retailers: An Exploratory Segmentation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 64, 102774. DOI: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102774

50. Parker, H. J., & Flowerday, S. (2021). Understanding the disclosure of personal data online. Information & Computer Security, 29(3), 413–434. DOI: 10.1108/ics-10-2020-0168

51. Pizzi, G., & Scarpi, D. (2020). Privacy threats with retail technologies: A consumer perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 56, 102160. DOI: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102160

52. Robinson, S. C. (2017). Disclosure of personal data in ecommerce: A cross-national comparison of Estonia and the United States. Telematics and Informatics, 34(2), 569–582. DOI: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.09.006

53. Robinson, S. C. (2018). Factors predicting attitude toward disclosing personal data online. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 28(3), 214–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/10919392.2018.1482601

54. Rossolov, A., Rossolova, H., & Holguín-Veras, J. (2021). Online and in-store purchase behavior: shopping channel choice in a developing economy. Transportation, 48(6), 3143–3179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-020-10163-3

55. Skare, V., Urbonavicius, S., Laurutyte, D., & Zimaitis, I. (2020). Dispositional willingness to provide personal data online: antecedents and the mechanism. Proceedings of the European Marketing Academy Annual Conference, 50 (60890).

56. Song, P., Wang, Q., Liu, H., & Li, Q. (2020). The Value of Buy‐Online‐and‐Pickup‐in‐Store in Omni‐Channel: Evidence from Customer Usage Data. Production and Operations Management, 29(4), 995–1010. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13146

57. Swani, K., Milne, G. R., & Slepchuk, A. N. (2021). Revisiting Trust and Privacy Concern in Consumers’ Perceptions of Marketing Information Management Practices: Replication and Extension. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 56, 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2021.03.001

58. Swoboda, B., & Winters, A. (2021). Reciprocity within major retail purchase channels and their effects on overall, offline and online loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 125, 279–294. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.024

59. Tikhomirova, A., Huang, J., Chuanmin, S., Khayyam, M., Ali, H., & Khramchenko, D. S. (2021). How Culture and Trustworthiness Interact in Different E-Commerce Contexts: A Comparative Analysis of Consumers’ Intention to Purchase on Platforms of Different Origins. Frontiers in Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746467

60. Toufaily, E., Souiden, N., & Ladhari, R. (2013). Consumer trust toward retail websites: Comparison between pure click and click-and-brick retailers. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(6), 538–548. DOI: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.05.001

61. Urbonavicius, S. (2020). Willingness to disclose personal data online: not just a situational issue. Proceedings of AIRSI 2020 Conference, Zaragoza University, 66–90.

62. Urbonavicius, S. (2023). Relative power of online buyers in regard to a store: how it encourages them to disclose their personal data? International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising. (unpublished).

63. Urbonavicius, S., Degutis, M., Zimaitis, I., Kaduskeviciute, V., & Skare, V. (2021). From social networking to willingness to disclose personal data when shopping online: Modelling in the context of social exchange theory. Journal of Business Research, 136, 76–85. DOI:10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2021.07.031

64. Verhagen, T., van Dolen, W., & Merikivi, J. (2019). The influence of in‐store personnel on online store value: An analogical transfer perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 36(3), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21172

65. Wang, J., Huang, Q., Li, Y., & Gu, J. (2021). Reducing transaction uncertainty with brands in web stores of dual-channel retailers. International Journal of Information Management, 61, 102398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102398

66. Wang, K., & Goldfarb, A. (2017). Can Offline Stores Drive Online Sales?. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(5), 706–719. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0518

67. Wang, T., Duong, T. D., & Chen, C. C. (2016). Intention to disclose personal information via mobile applications: A privacy calculus perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 36(4), 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.03.003

68. Wang, Y. D., & Emurian, H. H. (2005). An overview of online trust: Concepts, elements, and implications. Computers in Human Behavior, 21(1), 105–125. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2003.11.008

69. Weydert, V., Desmet, P., & Lancelot-Miltgen, C. (2019). Convincing consumers to share personal data: double-edged effect of offering money. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 37(1) 1–9. DOI: 10.1108/JCM-06-2018-2724

70. Wirtz, J., & Lwin, M. O. (2009). Regulatory Focus Theory, Trust, and Privacy Concern. Journal of Service Research, 12(2), 190–207.

71. Wu, W., Wang, S., Ding, G., & Mo, J. (2023). Elucidating trust-building sources in social shopping: A consumer cognitive and emotional trust perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 71, 103217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103217

72. Xiao, L., Zhang, Y., & Fu, B. (2019). Exploring the moderators and causal process of trust transfer in online-to-offline commerce. Journal of Business Research, 98, 214–226. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.069

73. Xu, H., Dinev, T., Smith, J., & Hart, P. (2011). Information Privacy Concerns: Linking Individual Perceptions with Institutional Privacy Assurances. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 12(12), 798–824.

74. Yasa, Y. A., & Cop, R. (2022). Factors creating consumer trust in Instagram stores and the influence of trust in Instagram stores on purchasing intention. Business and Economics Research Journal, 13(4), 687–705. http://dx.doi.org/10.20409/berj.2022.397

75. Zhang, J. Hassandoust, F., & Williams, J.E. (2020). Online Customer Trust in the Context of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 12(1), 86–122. https://doi.org/10.17705/1pais.12104

76. Zimaitis, I. Urbonavicius, S, Degutis, M., Kaduskeviciute, V. (2020) Impact of age on the willingness to disclose personal data in e-shopping. Proceedings of EMAC 11th Regional Conference, Zagreb.

77. Zimaitis, I., Urbonavicius, S., Degutis, M., & Kaduskeviciute, V. (2022). Influence of Trust and Conspiracy Beliefs on the Disclosure of Personal Data Online. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2022.16119

Appendix

Scales and their Sources

|

Variable and scale items |

Source |

|

|

Propensity to trust scale: |

Frazier et al. (2013) |

|

|

|

I usually trust people until they give me a reason not to trust them. |

|

|

|

Trusting another person is not difficult for me. |

|

|

|

My typical approach is to trust new acquaintances until they prove I should not trust them. |

|

|

|

My tendency to trust others is high. |

|

|

Willingness to disclose personal data: |

Gupta et al. (2010) and Heirman et al. (2013) |

|

|

|

While purchasing goods or services online, you are often asked to provide to them your personal data. Please, specify, how much you are willing to provide personal data of each type: |

|

|

|

First name |

|

|

|

Last name |

|

|

|

Age |

|

|

|

Home address |

|

|

|

Mobile phone number |

|

|

|

E-mail address |

|

|

Perceived regulatory effectiveness: |

Lwin et al. (2007) |

|

|

|

The existing laws in my country and internationally (such as General Data Protection Regulation, GDPR)* are sufficient to protect consumers’ online privacy. |

|

|

|

There are stringent international laws to protect personal information of individuals on the Internet. |

|

|

|

The government is doing enough to ensure that consumers are protected against online privacy violations.

|

|

|

Trust in a store: |

King (2018) |

|

|

|

Based on what I have read, I find the .............................................. |

|

|

|

Based on the information given in the scenario above, I trust the |

|

Note. * Modifications of the original statements