Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2023, vol. 14, no. 2(28), pp. 260–285 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2023.14.92

Proactive Service Recovery Performance in Emerging (vs. Developed) Market-Based Firms: The Role of Clients’ Cultural Orientation

Naghmeh Nik Bakhsh

Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7112-0593

nanikb@taltech.ee

Linda D. Hollebeek (corresponding author)

Vilnius University, Lithuania

Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia

Umeå University, Sweden

Lund University, Sweden

University of Johannesburg, South Africa

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1282-0319

linda.hollebeek@evaf.vu.lt

Iivi Riivits-Arkonsuo

Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9567-0386

iivi.riivits@taltech.ee

Moira K. Clark

Henley Business School, University of Reading, Greenlands Campus, United Kingdom

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7123-4248

moira.clark@henley.ac.uk

Ramunas Casas

Vilnius University, Lithuania

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2165-8285

ramunas.casas@evaf.vu.lt

Abstract. Though service recovery plays a key role in industrial clients’ post-recovery supplier evaluations, the impact of customers’ cultural orientation on the effectiveness of supplier-instigated proactive recovery (i.e., a supplier’s recovery efforts before clients notice/complain) remains tenuous, particularly in emerging (vs. developed) markets. Addressing this gap, we develop a model that examines (a) the moderating role of clients’ cultural orientation on the association of supplier-instigated proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related justice, and (b) the impact of customer-perceived justice on relationship quality in the emerging (vs. developed) market context. To test the model, we deploy a cross-cultural scenario-based experiment using 117 Danish industrial clients (i.e., developed market) and 109 Iranian industrial clients (i.e., emerging market). The results suggest that customers’ cultural orientation partially moderates the relationship of suppliers’ proactive recovery and customer-perceived justice, in turn boosting relationship quality in the emerging/developed market context.

Keywords: proactive service recovery, emerging markets, cultural orientation, perceived justice, relationship quality, scenario-based experiment

Received: 17/10/2022. Accepted: 30/3/2023

Copyright © 2023 Naghmeh Nik Bakhsh, Linda D. Hollebeek, Iivi Riivits-Arkonsuo, Moira K. Clark. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

While contemporary firms strive to minimize service failure, in some instances such failure is inevitable, yielding a need for firms to appropriately resolve these issues (e.g., Döscher, 2013). To do so, firms may deploy a host of tactics, including proactive or reactive service recovery approaches. While reactive recovery is initiated when customers complain (Hübner et al., 2018), its counterpart of proactive recovery reflects the supplier’s activation of the recovery process before customers notice failure and start to complain (Silva et al., 2020). Though proactive recovery incurs a higher upfront (e.g., failure prevention) cost, the literature suggests that it allows firms to better mitigate the consequences of failure-induced damage, including through the early identification of potential failure causes, preparing and/or informing customers, and solving issues at the earliest opportunity, thus minimizing customer frustration and damage to customer relationships (Döscher, 2013).

While the literature boasts a growing understanding of proactive service recovery, existing studies have primarily explored the concept in a single market context (e.g., Harper & Mustafee, 2019), revealing limited acumen of proactive service recovery performance in emerging (vs. developed) markets, which are likely to exhibit (e.g., cross-cultural/infrastructure-based) differences. However, in today’s increasingly globalized environment, service recovery scenarios are likely to involve individuals (e.g., clients) from differing cultural backgrounds, whether conducted in an emerging or a developed market, yielding a need to better understand the impact of proactive service recovery in these multi-cultural contexts, particularly those characterized by high cultural distance (Qin et al., 2011; Ozen & Kodaz, 2012; Horváth et al., 2013; Park et al., 2018).

Addressing this gap, we hypothesize that industrial clients’ cultural orientation moderates the association of a supplier’s proactive recovery activity and customer-perceived recovery-related justice and relationship quality. In other words, we posit that the strength of the latter association is affected by industrial clients’ cultural (e.g., individualism/collectivism) orientation, as explored empirically in this paper. Though prior literature has addressed related issues, including suppliers’ service failure responses to salvage customer satisfaction (e.g., Zhu & Zolkiewski, 2015), insight into these issues across emerging (vs. developed) markets remains scant (Döscher, 2013; Patterson et al., 2006) as, therefore, addressed in this research. We expect our findings to be of the utmost importance for internationally trading industrial firms across emerging/developed markets, as discussed further in the paper’s final section.

This paper makes two main contributions to the service recovery and emerging markets literature. First, we develop an equity theory-informed framework that explores whether the association of a supplier’s proactive recovery activity and client-perceived recovery-related justice is influenced (i.e., moderated) by the client’s cultural (e. g., individualist/collectivist) orientation, which to a significant extent corresponds to the individual’s developed (vs. emerging) market-based location. Relatedly, we also assess whether client-perceived justice affects the individual’s perceived B2B relationship quality (Hollebeek, 2019). We adopt an equity theory perspective, given our focus on understanding customer-perceived proactive recovery-related fairness and its impact on perceived relationship quality across emerging/developed markets (Silva et al., 2020).

Second, we empirically test the hypothesized associations in a developed (i.e., Denmark) and an emerging (i.e., Iran) market (Britannica, 2022; Serkland, 2021), which exhibit considerable cultural differences (Hofstede Insights, 2021). The reported analyses, thus, contribute important cross-cultural insight to industrial firms’ service recovery efforts across emerging (vs. developed) markets, which remains scant to date (Oflaç et al., 2021). The findings suggest that while clients’ cultural orientation moderates the association of supplier-instigated proactive recovery and client-perceived distributive and interactional justice in the studied emerging and developed market, no significant effect is found for procedural justice across clients of differing cultural orientations in these respective markets. The results also affirm that client-perceived justice enhances relationship quality, exposing pivotal strategic insight for cross-border operating firms, as discussed further in the implications arising from this research.

The paper unfolds as follows. We next review key literature on industrial service recovery, customers’ cultural orientation, perceived justice, and relationship quality, followed by the development of the research hypotheses. Next, we outline the methodology, followed by an overview of our main results, and a discussion of the findings and their implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Industrial Service Failure and Recovery

Koc (2017, p. 1) defines service failure as “any type of error, mistake, deficiency, or problem that occurs during [service] provision, causing a delay or hindrance in the satisfaction of customer needs.” Industrial service failure can stem from myriad issues, including supplier-induced problems, environmental factors (e.g., natural disaster), or customer-related issues (Borah et al., 2019). We focus on supplier-induced failure that transpires through lacking service provision (Zhu & Zolkiewski, 2015), including non-service delivery or delivery delays, which typically affect customers’ supplier evaluations. Industrial (vs. B2C)-based service failure features greater complexity, given the parties’ more relational partnership, which may arise through factors including long-term (e.g., supply) contracts, customers’ reliance on a sole supplier, switching costs, etc. Therefore, industrial service failure minimization and prevention (e. g., through proactive recovery) are pertinent (Baliga et al., 2020).

Döscher (2013, p. 18) defines industrial recovery management as “a systematic approach taken by seller[s]… for the development, implementation, and control of activities to handle …service failures to regain customer satisfaction and [retain customers] in B2B markets,” which can impact the post-failure customer/supplier relationship. As noted, recovery may be reactive or proactive. First, reactive recovery, which is most common, is initiated upon the firm’s receipt of a customer complaint (Döscher, 2013). Though this approach (e.g., offering clients financial compensation) tends to feature short-term monetary (e.g., maintenance cost) savings, it can, however, incur customer (e.g., recovery delay-related) frustration when things go wrong (Hübner et al., 2018; Guchait et al., 2019).

Second, proactive recovery entails the supplier’s activation of the recovery process before customers notice failure and start to complain (Hübner et al., 2018). These suppliers tend to use contingency planning that outlines procedures for tackling relevant failures (Baliga et al., 2020). On the downside, proactive recovery requires the firm’s additional failure prevention effort and cost (e.g., regular monitoring to identify/address looming failures; Hogreve et al., 2017). Proactive recovery thus mitigates failure-related damage, reduces recovery time, and enhances post-failure client-perceived relational outcomes (Döscher, 2013).

Though existing research highlights favorable effects accruing from proactive (vs. reactive) recovery strategies (Silva et al., 2020), few studies have investigated the role of industrial customers’ cultural orientation in assessing proactive recovery performance (Döscher, 2013), exposing a key literature-based gap, as outlined. We, however, argue that industrial clients of differing cultural orientations are expected to respond differently to a firm’s proactive service recovery efforts, yielding pertinent strategic implications. In other words, while industrial clients’ cultural orientation is widely acknowledged to impact their purchase-related sentiment and behavior (Lowe & Rod, 2020), little remains known regarding clients’ evaluation of suppliers’ proactive recovery strategies across cultures, as, therefore, explored in this article. We next review the concept of clients’ cultural orientation.

2.2 Clients’ Cultural Orientation

The literature affords extensive attention to (national) culture, defined as “the collective programming of the mind, which distinguishes the members of one group …of people from another” (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005, p. 3). Correspondingly, the scholarly discourse boasts several cultural frameworks, including Hofstede’s (1980, 1991) and Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s (1998) models of national culture. Of these, Hofstede’s (e.g., 1991) framework has been the most influential, as evidenced by its broad adoption, including in business, marketing, and cross-cultural studies (Tarka & Babeev, 2021).

Hofstede’s five-dimensional model comprises individualist/collectivist, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity/femininity, and short/long-term orientation (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005), which have been not only applied at the level of national culture, but also to assess individual-level cultural dynamics (e.g., Hollebeek, 2018; Heydari et al., 2021; Rinuastuti et al., 2014), as in this study. We focus on three of Hofstede’s more salient dimensions in industrial proactive recovery, including individualist/collectivist, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance orientation, which we expect to primarily affect industrial customers’ proactive recovery responses (Ye & Luo, 2016), as discussed further below.

First, individualist/collectivist orientation is anchored in individualism and collectivism. Individualism is “a social pattern that consists of loosely linked individuals, who view themselves as independent of collectives” (Triandis, 1995, p. 2). By contrast, this author defines collectivism as “a social pattern consisting of closely linked individuals, who see themselves as part of one or more collectives” (e.g., family/tribe; p. 2). We expect clients’ individualist (vs. collectivist) orientation to affect their proactive recovery responses. For example, collectivist-oriented clients, who tend to evaluate their supplier more holistically than their more individualist-oriented counterparts (Monga & Roedder-John, 2007), may be more accepting of a firm’s proactive recovery-related activity or delays.

Second, power distance orientation refers to “the extent to which the less powerful members in society accept the unequal distribution of power” (Hofstede, 1980, p. 390). In high-power distance societies, people obey their superiors’ orders. However, less power distance-oriented societies typically see more participatory/democratic decision-making. Though power distance orientation impacts clients’ assessment of service recovery-related explanations/apologies (Guchait et al., 2019), acumen of these dynamics characterizing proactive recovery-implementing industrial suppliers lags behind, necessitating further exploration. We expect clients exhibiting a high (vs. low) power distance orientation to display differing responses to supplier-instigated proactive recovery. For example, high power distance-oriented customers may respond more favorably to a high (vs. low)-status representative delivering proactive recovery-related communications.

Third, uncertainty avoidance orientation denotes the extent to which people tolerate ambiguous/unknown situations (Hofstede, 1980). While highly uncertainty-avoidant societies tend to minimize ambiguity, their low-uncertainty-avoidant counterpart exhibits greater tolerance of ambiguity. In the proactive recovery context, industrial clients high (vs. low) in uncertainty avoidance orientation are anticipated to be more open to a supplier’s proactive recovery efforts, given their desire to minimize ambiguity and uncertainty (Fillieri et al., 2021).

We, therefore, include these dimensions in our study. Following Patterson et al. (2006), we thus exclude Hofstede’s long/short term orientation, which denotes how people in a society associate the past, present, and future (Hofstede, 2015), and masculinity/femininity orientation, which reveals a society’s sex role pattern (Hofstede, 1980), given their limited applicability to B2B-based proactive recovery across emerging/developed markets (Patterson et al., 2006). We next review literature on customer-perceived justice.

2.3 Customer-Perceived Justice

Equity theory is widely-used in the service recovery literature, given its capacity to analyze recovery processes and outcomes (e.g., failure resolution/compensation), which in turn affect customer-perceived justice (Patterson et al., 2006). As service failure and its resolution’s perceived fairness are culturally dependent (Adams, 1965), we argue for equity theory’s suitability in this research. Specifically, we explore the role of industrial customers’ cultural orientation in shaping their evaluations of suppliers’ proactive recovery-related perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional fairness or justice (Williams et al., 2022).

Equity theory posits that individuals compare their perceived inputs/costs to their perceived returns/benefits, which they then contrast to their perception of another party’s (e.g., a fellow customer’s) costs/returns (Adams, 1965). Therefore, as customers evaluate their supplier’s proactive recovery effort, they will tend to consider their failure-induced loss and recovery-related gain (Smith et al., 1999). If clients feel they are treated unjustly during recovery, this perceived unfairness will be viewed as another loss, yielding their expected inflated negative response (Cheng et al., 2019).

In service recovery, customers typically perceive three justice types (Duffy et al., 2013). First, distributive justice reflects a customer’s “perceived fairness of the outcome of a [recovery] process” (Patterson et al., 2006, p. 2), as assessed by comparing one’s recovery outcome to that perceived to be had by fellow customers in the same/an equivalent exchange (Smith et al., 1999). In the B2B literature, distributive justice is shown to play an important role in affecting clients’ future firm-related sentiment and behavior (Hoppner et al., 2014).

Second, procedural justice denotes a customer’s “perceived fairness of the process employed [to] resolv[e] service failure,” including of recovery-related policies/procedures or communications (Patterson et al., 2006, p. 2). As firms typically regulate the allocation of recovery resources (e.g., among clients), customers evaluate this distribution in terms of their perceived procedural justice, in turn affecting their firm-related behavior (Oflaç et al., 2021).

Third, interactional justice represents the customer-perceived fairness of his/her treatment during the recovery process (e.g., perceived level of courtesy/empathy). It, thus, focuses on the “social aspect of the [recovery] processes” (Bouazzaoui et al., 2020, p. 131), which plays a key role in client-perceived recovery fairness. Collectively, distributive, procedural, and interactional justice determine the level of client-perceived service recovery fairness, thus influencing their future supplier-related behavior. We next review the relationship quality literature.

2.4 Client-Perceived Relationship Quality

The relationship quality construct has received extensive attention (Skudiene et al., 2021; Mohan et al., 2021). Though its conceptualization is debated, relationship quality is typically viewed as a higher-order concept comprising customer-perceived supplier trust, satisfaction, and commitment (Hollebeek, 2019), with higher levels of these variables denoting superior relationship quality. First, customer trust reflects the degree to which customers believe that their exchange partner is trustworthy and reliable (Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Guo et al., 2021). It comprises (a) credibility, or the customer’s expectancy that the word/promise made by a firm can be relied upon, and (b) benevolence, the customer’s confidence in the firm’s motives and the degree to which (s)he believes the firm acts in his/her best interest (Doney & Cannon, 1997; Hollebeek & Macky, 2019).

Second, customer satisfaction denotes a customer’s broad evaluation of his/her supplier experience (Döscher, 2013), which has been viewed as pertinent to customer retention (Kotler, 1994). It is also identified as key to firms’ (reactive) recovery efforts (McCollough et al., 2000). Third, customer commitment refers to a customer’s “valuing of an ongoing relationship with the supplier… to warrant maximum efforts at maintaining it” (Morgan & Hunt, 1994, p. 24), thus revealing a key link to customer loyalty (Döscher, 2013; Rather et al., 2021). We next develop the hypotheses.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1 Individualist/Collectivist Orientation and Perceived Recovery Justice

3.1.1. Distributive Justice. Though more individualist-oriented customers will primarily look after their own interests, collectivist-oriented clients will tend to focus on collective values, needs, and interests (Fillieri et al., 2021). As also discussed, distributive justice denotes a client’s perceived fairness of a recovery process outcome (Yani-de-Soriano et al., 2019). Given their concern for collective well-being and their tendency to evaluate a supplier more holistically (Monga & Roedder-John, 2007; Hollebeek, 2018), more collectivist (vs. individualist)-oriented clients are likely to view their outcome attained from a supplier’s proactive recovery as a sign of protection or security (e.g., to safeguard their future service experience), leading them to perceive greater proactive recovery-related distributive justice (vs. individualist customers). We posit:

H1a: The association of a supplier’s proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related distributive justice is moderated by the client’s collectivist (vs. individualist) orientation, such that clients displaying a collectivist (vs. individualist) orientation will perceive greater distributive justice.

3.1.2. Procedural Justice. As noted, collectivist (vs. individualist) customers’ more relational stance leads them to evaluate their supplier more holistically (Monga & Roedder-John, 2007). That is, rather than highlighting the supplier’s individual failure-related aspects, collectivist (vs. individualist)-oriented customers tend to primarily value the overall relationship, leading them to be more forgiving of the supplier’s service failure and proactive recovery efforts (Hollebeek, 2018). Consequently, suppliers’ proactive service recovery is likely to see their more collectivist (vs. individualist)-oriented clients’ higher proactive recovery-related procedural justice. Therefore,

H1b: The association of a supplier’s proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related procedural justice is moderated by the client’s collectivist (vs. individualist) orientation, such that clients displaying a collectivist (vs. individualist) orientation will perceive greater procedural justice.

3.1.3. Interactional Justice. As discussed, interactional justice denotes a customer’s perceived fairness of his/her treatment during the recovery process (e.g., level of courtesy/respect; Bouazzaoui et al., 2020). Collectivist-oriented customers tend to value social harmony/bonding, while abhorring confrontation (Hofstede, 1991). In B2B-based proactive recovery, we therefore posit that collectivist (vs. individualist)-oriented clients will tend to prefer the supplier’s recognition of the issue (vs. relying on them to raise it), as well as the supplier’s initiation of the recovery process, which is viewed as a sign of courtesy/respect toward the client (Mattila & Patterson, 2004). We hypothesize:

H1c: The association of a supplier’s proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related interactional justice is moderated by the client’s collectivist (vs. individualist) orientation, such that clients displaying a collectivist (vs. individualist) orientation will perceive greater interactional justice.

3.2 Power Distance Orientation and Perceived Recovery Justice

3.2.1. Distributive Justice refers to a client’s perceived fairness of the outcome of a recovery process (Yani-de-Soriano et al., 2019). Key proactive (vs. reactive) recovery outcomes include the removal of possible service failure causes, explanation of its likely causes to clients, and outlining the actions required to minimize incidents (Döscher, 2013). As proactive recovery efforts are typically communicated to clients by a supplier’s representative, we expect that clients displaying a high (vs. low) power distance orientation will respond more favorably to proactive recovery being conveyed by a high (vs. low)-status supplier representative (Fillieri et al., 2021). Consequently,

H2a: The association of a supplier’s proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related distributive justice is moderated by the client’s high (vs. low) power distance orientation, such that customers displaying a high (vs. low) power distance orientation will perceive greater distributive justice.

3.2.2. Procedural Justice entails a client’s perceived fairness of the process (e.g., procedures/policies) deployed to address service failure (e. g., Yani-de-Soriano et al., 2019). High power distance-oriented clients tend to conform to the provider’s expectations, particularly when these are conveyed by high- (vs. low)-status employees (Döscher, 2013). Correspondingly, these customers are expected to perceive higher proactive recovery-related procedural justice (vs. their low power distance-oriented counterpart). We posit:

H2b: The association of a supplier’s proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related procedural justice is moderated by the client’s high (vs. low) power distance orientation, such that customers displaying a high (vs. low) power distance orientation will perceive greater procedural justice.

3.2.3. Interactional Justice represents a client’s perceived proactive recovery-related fairness in terms of the courtesy/respect, etc. shown to the customer (Yani-de-Soriano et al., 2019). High power distance-oriented customers tend to value maintaining or enhancing (vs. losing) face (Fillieri et al., 2021), raising their likelihood of accepting or obeying the supplier’s proactive recovery instructions (e.g., to vacate a particular area), particularly when conveyed by higher-status employees (Döscher, 2013). High (vs. low) power distance-oriented clients are, thus, also more likely to accept the perceived interactional justice received from their supplier, particularly if communicated by high (vs. low)-status representatives (Hollebeck, 2018). Therefore,

H2c: The association of a supplier’s proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related interactional justice is moderated by the client’s high (vs. low) power distance orientation, such that customers displaying a high (vs. low) power distance orientation will perceive greater interactional justice.

3.3 Uncertainty Avoidance Orientation and Perceived Recovery Justice

3.3.1. Distributive Justice. Uncertainty avoidance orientation denotes the extent to which people tolerate ambiguous/unknown situations (Hofstede, 1980), while distributive justice reflects a client’s perceived fairness of a recovery process outcome. Clients exhibiting high uncertainty avoidance typically have a strong need to control (service failure) situations (Hogreve et al., 2017), including by identifying those responsible for resolving the failure or by implementing actions to minimize failure-induced damage, in turn reducing their perceived failure-related vulnerability and yielding enhanced recovery-related outcomes (Döscher, 2013). We postulate:

H3a: The association of a supplier’s proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related distributive justice is moderated by the client’s high (vs. low) uncertainty avoidance orientation, such that customers displaying a high (vs. low) uncertainty avoidance orientation will perceive greater distributive justice.

3.3.2. Procedural Justice reveals a customer’s perceived fairness of the recovery process (Yani-de-Soriano et al., 2019). In proactive recovery, suppliers offer their clients early failure-related warnings to reduce uncertainty (Döscher, 2013). We, in turn, expect highly uncertainty-avoidant customers to value these certainty-providing proactive recovery activities (e.g., as they permit clients’ preparation of a desired response; Johnston & Hewa, 1997), thus raising their perceived proactive recovery-related procedural justice. We propose:

H3b: The association of a supplier’s proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related procedural justice is moderated by the client’s high (vs. low) uncertainty avoidance orientation, such that customers displaying a high (vs. low) uncertainty avoidance orientation will perceive greater procedural justice.

3.3.3. Interactional Justice exposes a customer’s perceived fairness of a supplier’s proactive recovery-related courtesy/empathy, etc. shown to the client. The greater a client’s rapport with a supplier, the higher his/her expected interactional justice level (Döscher, 2013), particularly for highly uncertainty-avoidant clients, who aim to minimize recovery-related risk (Bouazzaoui et al., 2020). In other words, the existence of a close client/supplier relationship can reduce perceived risk, particularly for highly uncertainty-avoidance customers (Döscher, 2013). Correspondingly,

H3c: The association of a supplier’s proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related interactional justice is moderated by the client’s high (vs. low) uncertainty avoidance orientation, such that customers displaying a high (vs. low) uncertainty avoidance orientation will perceive greater interactional justice.

3.4 Perceived Proactive Recovery-Related Justice and Relationship Quality

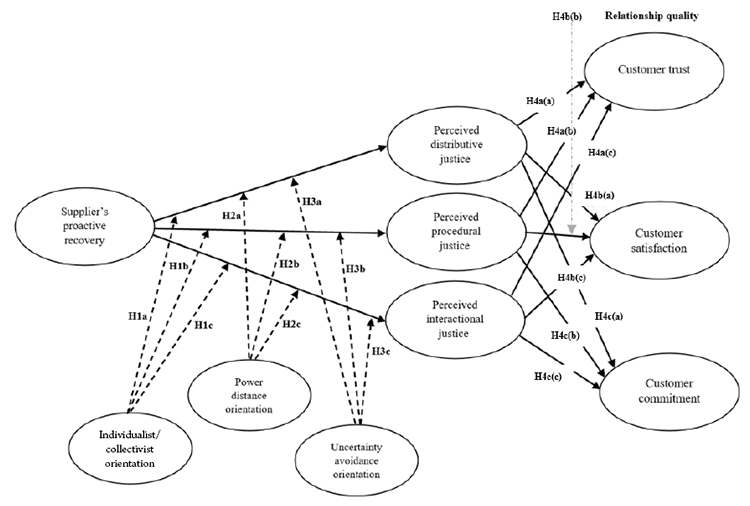

As shown in Figure 1, we also expect clients’ perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional justice to affect their perceived relationship quality. As outlined, relationship quality comprises client trust, satisfaction, and commitment (Marquardt, 2013). Though prior studies have explored the association of client-perceived justice and relationship quality (Giovanis et al., 2015), insight into the association of perceived justice dimensions and their respective effect on B2B-based relationship quality’s constituents remains tenuous.

Based on equity theory, we, therefore, propose that proactive recovery-instigated client-perceived justice will tend to boost the customer’s supplier evaluation, in turn cultivating customer-perceived relationship quality. Correspondingly, we postulate that client-perceived proactive recovery-related distributive, procedural, and interactional justice impact customer trust, or the extent to which the client believes a supplier is trustworthy and reliable (Doney & Cannon, 1997). That is, the more justly a client feels (s)he is treated overall in the supplier’s proactive recovery effort, the higher his/her anticipated trust in the provider. Therefore,

H4a: Customer-perceived proactive recovery-related (a) distributive, (b) procedural, and (c) interactional justice positively affect customer trust.

Second, customer satisfaction reflects a client’s broad evaluation of his/her supplier experience (Döscher 2013). The more fairly a client feels (s)he is treated in a supplier’s proactive recovery effort, in terms of his/her perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional justice (e.g., Yani-de-Soriano et al., 2019), the more satisfied the individual is likely to be with their supplier, as established in existing B2C-based research (e.g., McCollough et al., 2000). However, insight into this association in the industrial context remains scant, as outlined. Therefore,

H4b: Customer-perceived proactive recovery-related (a) distributive, (b) procedural, and (c) interactional justice positively affect customer satisfaction.

Third, customer commitment refers to the client’s valuing of his/her relationship with the supplier, warranting his/her effort at maintaining it (Roy et al., 2020). Like for customer trust and satisfaction, we posit that greater client-perceived proactive recovery-related distributive, procedural, and interactional justice will tend to yield elevated client commitment to their supplier (Kotabe et al., 1992), though B2B-based insight into this association, likewise, remains scant. We propose:

H4c: Customer-perceived proactive recovery-related (a) distributive, (b) procedural, and (c) interactional justice positively affect customer commitment.

A visual representation of the hypotheses is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Conceptual Model

4. Methodology

4.1 Scenario-Based Experimental Design and Survey Pretest

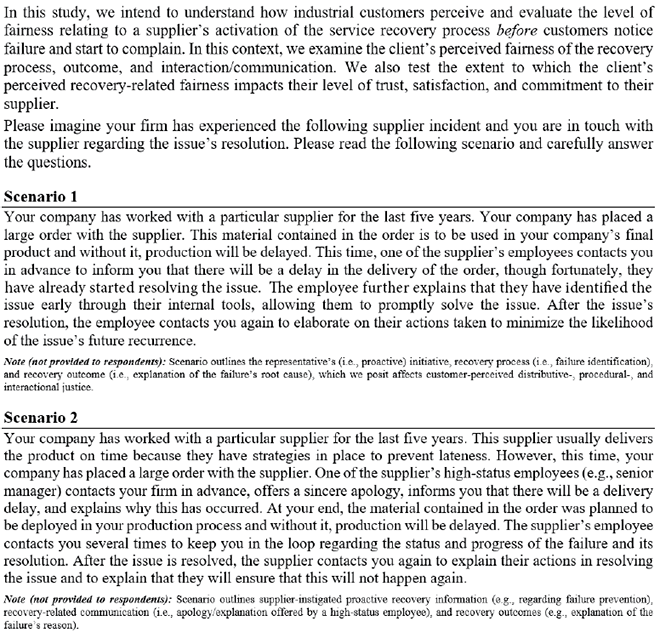

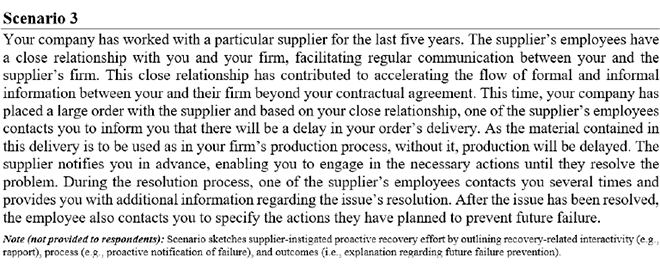

To test the hypotheses, we deployed a scenario-based experimental design that minimizes the potentially negative effect of intentionally placing customers in failure situations, while also abating potential (e.g., memory) bias inherent in the adoption of self-report measures (Smith et al., 1999; Patterson et al., 2006). To test the hypotheses, we employed three scenarios that each describes a proactive recovery approach taken for an industrial service delivery delay (see Appendix). Scenarios 1, 2, and 3 were designed to test the moderating effect of customers’ individualist/collectivist, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance orientation on the association of the supplier’s proactive recovery effort and client-perceived recovery-related justice, respectively. We requested a bilingual speaker familiar with the Danish/Iranian cultures to translate the original English scenarios into Danish/Persian, after which a different bilingual speaker back-translated the document to ensure translation equivalence.

We, then, pretested the survey by randomly assigning 30 Danish and 30 Iranian participants to one of the scenarios and examining their respective proactive recovery scores, rated on seven-point Likert scales, which revealed no issues. To compare the means of the Danish/Iranian sub-groups across our deployed dependent variables, we conducted a MANOVA, which revealed that both groups attained similar scores (mean Iran=4.90; mean Denmark=4.70; F=3.7, p >0.05).

4.2 Sampling Procedures

Individuals from Western (vs. non-Western) societies generally exhibit an individualist (vs. collectivist), and lower power distance and uncertainty avoidance orientations (Hofstede, 1991). We used purposive sampling to recruit the participants from Western (Danish/developed market) and non-Western (Iranian/emerging market) cultures, which display differing cultural orientations: On average, Danes (Iranians) reveal an individualist orientation of 74 (41) out of 100, a power distance orientation of 18 (58), and an uncertainty avoidance orientation of 23 (59), respectively (Hofstede Insights, 2021).

We surveyed 201 (310) employees in 50 Danish (76 Iranian) client companies, respectively, revealing our predominant attainment of multiple employees’ responses (vs. a single response) from each company across the Danish/Iranian sub-samples. To select our Danish firms, we used a leading database of industrial companies. Sectors in which the Danish companies operate include chemicals/chemical products, clothing/textile, construction/building materials, electronics, glass products, machinery, metalwork, packaging, paper (products), plastic products, printing, timber products, business services, information technology, and transportation. In each sector, we selected companies with an annual turnover exceeding €2m. Using the Iranian Business Register, we also selected 76 Iranian companies from the same sectors, with an annual turnover exceeding €2m, thus applying the same criteria.

We contacted the companies by email to identify the most suitable respondents. In each company, we selected the participants based on their organizational position (i.e., senior manager/team member). Most (97%) of the respondents were 35–56 years of age, 66% were male, and all participants had worked in the firm’s quality control, purchasing, or marketing departments for at least three years on the survey date. Given the research purpose, respondents were interviewed regarding their industrial customer role in dealing with their supplier. The respondents were also screened to ensure they engage in at least monthly supplier interactions.

As consent for a firm to participate in the study is likely taken by multiple individuals, we sent the questionnaire to 2–3 employees in each company. In our Danish client companies, we verified that all the participants were Danish, and likewise in the Iranian companies. After agreeing to participate in the study, participants randomly received one of the three proactive recovery scenarios (see Appendix). For the Danish sample, we received 117 complete responses (out of 201 distributed surveys), yielding a 58.2% response rate. For the Iranian sample, we received 109 (of 310 circulated surveys), yielding a 35.2% response rate. Though the data was collected at the individual (i.e., employee) level, it was subsequently aggregated based on respondents’ nationality. Given our research objective, we created two sub-samples of developed market-based Danish (i.e., individualist, low power distance, low uncertainty avoidance oriented) and emerging market-based Iranian (i.e., collectivist, high power distance, high uncertainty avoidance oriented) participants. Though Patterson et al. (2006, pp. 267–268) conducted a manipulation check, prior authors had outlined the potential threats to a study’s validity inherent in this approach (e.g., Hauser et al., 2018; Sigall & Mills, 1998). Following these authors, we did not conduct a manipulation check in this study.

4.3 Measures

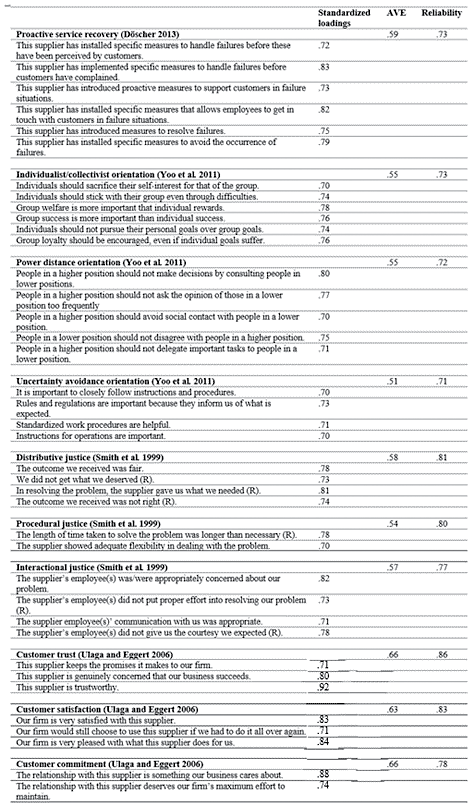

After reading their assigned scenario, participants were requested to report their cultural orientation, perceived recovery-related justice, and perceived relationship quality on seven-point Likert scales ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7), allowing us to compare the results for our individualist/collectivist-, high/low power distance-, and high/low uncertainty avoidance-oriented sub-samples.

We first measured the supplier’s proactive recovery activity by using Döscher’s (2013) proactive service recovery scale (Table 1). Second, we gauged clients’ individualist/collectivist, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance orientation by using Yoo et al.’s (2011) scales. To confirm the differing cultural orientation of our sub-samples, we conducted a MANOVA, which attested that Iranians indeed exhibit a higher collectivist (mean Iran=4.57; mean Denmark=2.63, F = 31.76; p < .05), power distance (mean Iran=4.53; mean Denmark=2.19, F = 30.37, p < .05), and uncertainty avoidance orientation (mean Iran=4.72; mean Denmark=2.97; F = 58.47, p < .05).

Adapting Smith et al. (1999) scale, we also measured customer-perceived proactive recovery-related distributive (4 items), procedural (2 items), and interactional justice (4 items). Finally, we used Ulaga and Eggert’s (2006) scales to measure customer trust, satisfaction, and commitment, which collectively comprise relationship quality. Using SPSS (v. 20) and AMOS (v. 24), we then conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) on these scales, which led to the removal of a small number of items for proactive recovery and customer commitment, due to their factor loadings being < .50. Table 1 presents an overview of the deployed items and their respective factor-analytic, AVE, and reliability results, which all met their respective criteria.

All factor loadings and fit indices were adequate: supplier’s proactive recovery (CMIN/df = 1.20, GFI = .95, AGFI = .87, NFI = .89, CFI= .93, IFI = .93, RMSEA = .04), client’s cultural orientation (CMIN/df = 1.06, GFI = .96, AGFI = .92, CFI = 97, NFI = .93, IFI =.97, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .053), client-perceived justice (CMIN/df = 1.21, GFI = .98, AGFI = .96, NFI = .98, IFI = .99, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .031), and client-perceived relationship quality (CMIN/df = 2.72, GFI = .95, AGFI = .88, NFI = .95, IFI = .97, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .060). Scale reliability, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was also acceptable (> .70) for each scale (Table 1). Moreover, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for the model’s latent variables ranged from 0.53–0.73, and the square root of the AVE for each latent variable exceeded its respective correlation with the other latent variables, confirming the existence of convergent and discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Table 1

Factor-Analytic, AVE, and Reliability Results

5. Results

5.1 Moderating Role of Cultural Orientation

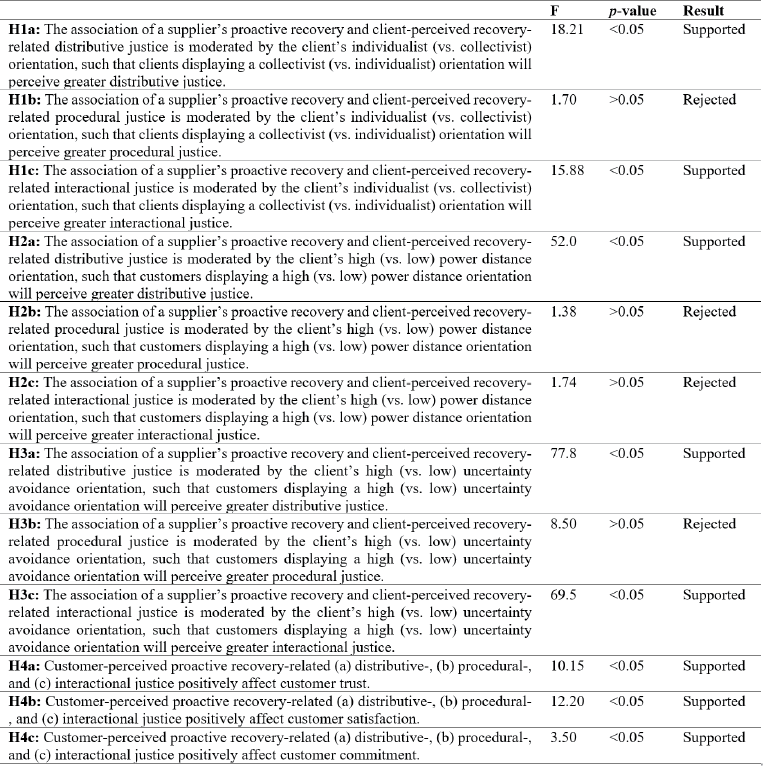

5.1.1. Individualist/Collectivist Orientation. Deploying Scenario 1, a MANOVA was conducted by using distributive, procedural, and interactional justice as the dependent variables for our collectivist (Iran/n=30) and individualist (Denmark/n=47) oriented sub-samples, thus testing H1a-c. As noted, we expect clients’ individualist/collectivist orientation to moderate these associations. The MANOVA results suggested that our emerging market-based Iranian respondents indeed displayed greater proactive recovery-related distributive justice (mean Iran=4.49; mean Denmark=3.40; F=18.21, p<0.05), supporting H1a. However, our Iranian/Danish respondents did not significantly differ in terms of their perceived proactive recovery-related procedural justice (mean Iran=4.1; mean Denmark=4.3; F=1.7, p >0.05), leading us to reject H1b. Conversely, the Iranian sample exhibited greater perceived proactive recovery-related interactional justice (mean Iran=5.5; mean Denmark=4.5; F= 15.88, p<0.05), supporting H1c.

5.1.2. Power Distance Orientation. Using Scenario 2, we conducted a MANOVA that used client-perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional justice as the dependent variables for our high (i.e., Iranian/n=34) and low (i.e., Danish/n=34) power distance-oriented sub-samples, thus testing H2a-c. For distributive justice, the results confirm that our high-power distance-oriented (emerging market-based Iranian) sub-sample indeed perceived greater proactive recovery-related distributive justice than its low power distance-oriented (developed market-based Danish) counterpart (mean Iran=4.73; mean Denmark=3.40; F=52.01, p<0.05), supporting H2a. However, the results suggest a non-significant difference in client-perceived proactive recovery-related procedural justice across our high/low power distance-oriented sub-samples (mean Iran=4.09; mean Denmark=4.50; F=1.38, p>0.05), rejecting H2b. Likewise, the high/low power distance-oriented sub-samples expose similar proactive recovery-related interactional justice scores (mean Iran=4.70; mean Denmark=4.50; F= 1.74, p >0.05), refuting H2c.

5.1.3. Uncertainty Avoidance Orientation. Using Scenario 3, we undertook a further MANOVA to test H3a-c, allowing us to compare the high (Iranian/n=45) and low (Danish/n=36) uncertainty avoidance-oriented sub-groups (Hofstede Insights, 2021). For distributive justice, the results confirmed our expectation (mean Iran=4.58; mean Denmark=3.11; F=77.8, p<0.05), supporting H3a. Surprisingly, our high/low uncertainty avoidance-oriented sub-samples were found to not significantly differ in terms of their respective proactive recovery-related procedural justice across the emerging (vs. developed) market sub-samples (mean Iran=5.05; mean Denmark=4.95; F=8.50, p >0.05), rejecting H3b. Finally, our high/low uncertainty avoidance-oriented sub-groups indeed differed in terms of their proactive recovery-related interactional justice (mean Iran=5.00; mean Denmark=3.4; F= 69.5, p <0.05), supporting H3c. Hypothesis testing results are shown in Table 2.

5.2 Client-Perceived Proactive Recovery-Related Justice and Relationship Quality

We next pooled the data from both samples (Danish: n=117; Iranian: n=109) to examine the effect of customer-perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional justice on relationship quality (i.e., customer trust, satisfaction, and commitment). We first ran a multiple regression by using customer trust as the dependent variable, and distributive, procedural, and interactional justice as the predictor variables (distributive justice: β = .31; procedural justice: β = .17; interactional justice: β = .13). The ANOVA results revealed that all three perceived justice sub-types positively affect customer trust (F = 10.15, p < 0.05), substantiating H4a.

Table 2

Hypotheses Testing Results

We, then, assessed the effect of proactive recovery-related client-perceived justice on customer satisfaction. Since distributive (β = .24), procedural (β = .31), and interactional justice (β = .14) displayed significant main effects (F = 12.20; p < 0.05), H4b was supported. Finally, we conducted a multiple regression using customer commitment as the dependent variable, and client-perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional justice as the predictor variables. The ANOVA results confirm the hypothesized positive effect of each of the three perceived justice dimensions on customer commitment (F = 3.50; p < 0.05), supporting H4c. Moreover, the standardized coefficient for procedural justice (β = .15) exceeded that of distributive (β = .12) and interactional justice (β = .05), implying that the impact of procedural justice on customer commitment was greater than that of distributive or interactional justice. We next discuss our results and draw implications from our analyses.

6. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

6.1 Discussion

Service failure in industrial relationships is not completely preventable. Therefore, when failure occurs, a key challenge lies in suppliers restoring clients’ post-failure perceived justice and relationship quality (e.g., Chi et al., 2020), which can be facilitated by deploying proactive (vs. reactive) recovery strategies (Silva et al., 2020), which, however, remain nebulous in international B2B marketing to date. In today’s globalized markets, cross-border recovery management brings the additional challenge of clients’ differing cultural orientations (e.g., Tower et al., 2019), including through interactions of clients from emerging (vs. developed) markets, which may differentially affect customers’ proactive recovery-related evaluations. However, despite existing literature-based acumen, insight into the role of customers’ cultural orientation on their proactive recovery-related perceived justice and relationship quality in emerging (vs. developed) markets lags behind, as, therefore, explored in this paper.

To address this gap, we collected data from industrial clients in Denmark (i.e., developed market) and Iran (i.e., emerging market). Our most notable finding is that clients’ individualist/collectivist, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance orientations partially moderate the association of supplier-instigated proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related justice (H1a-c, H2a-c, H3a-c), thus largely aligning with Patterson et al.’s (2006) B2C-based findings. The results also confirm that client-perceived post-recovery justice impacts perceived relationship quality (H4a-c), also Luo et al.’s (2019) results in the cross-border B2B context. Collectively, the findings highlight the key role of customers’ cultural orientation in proactive service recovery performance in the emerging and developed market context, suggesting that cultural orientation should be taken as a pertinent input in the design of B2B-based proactive service recovery strategy. Thus, industrial suppliers’ proactive service recovery performance cannot be effectively assessed without duly acknowledging customers’ cultural orientation, thus extending the work of Luo et al. (2019), Patterson et al. (2006), and Döscher (2013) in the B2B context.

First, the results for H1a-c reveal that industrial customers’ individualist/collectivist orientation moderates the relationship between a supplier’s proactive service recovery and client-perceived distributive/interactional justice for our emerging and developed market-based sub-samples. However, no significant difference was found across these groups for procedural justice (H1b). As procedural justice denotes a client’s perceived fairness of the recovery process (e.g., policies/procedures; Yani-de-Soriano et al., 2019), this finding suggests that industrial clients, regardless of their individualist/collectivist orientation, equally value proactive recovery-related procedural fairness. For example, if clients have to wait due to a supplier’s proactive prevention of a potential failure, they will expect other clients to have a similar wait, irrespective of whether they are more individualist- or collectivist-oriented customers (Casidy et al., 2021).

Second, the findings for H2a-c show that clients’ power distance orientation moderates the association of a supplier’s proactive service recovery and client-perceived distributive justice, with high (vs. low) power distance-oriented clients indeed perceiving greater distributive justice (H2a). However, our high (Iranian) vs. low (Danish) power distance-oriented clients were not found to significantly differ with respect to their proactive recovery-related procedural/interactional justice (H2b-c), despite their elevated cultural distance (Tower et al., 2019). That is, both high/low power distance-oriented groups were found to similarly value proactive recovery-related procedural/interactional justice.

Third, the results for H3a-c suggest that industrial clients’ uncertainty avoidance orientation moderates the relationship between supplier-instigated proactive service recovery and client-perceived distributive and interactional justice (H3a/H3c). However, our low (Danish/developed market) and high (Iranian/emerging market) uncertainty avoidance-oriented sub-groups equally value the supplier’s proactive recovery-related procedural justice (H3b). In other words, like clients’ individualist/collectivist and power distance orientation (H1b/H2b), their uncertainty avoidance orientation fails to discriminate these groups in terms of their respective importance attributed to proactive recovery-related procedural justice.

Finally, our findings for H4a-c indicate that client-perceived proactive recovery-related distributive, procedural, and interactional justice impact supplier relationship quality. Overall, client-perceived procedural (vs. distributive/interactional) justice, which was found to not significantly differ across clients’ cultural orientation, exerts a particularly strong effect on relationship quality. Our findings, therefore, differ from those of Patterson et al. (2006), as follows (Luo et al., 2019). Unlike these authors’ fully moderating B2C-based results, our results indicate that industrial clients’ individualist/collectivist, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance orientation partially moderate the association of supplier-instigated proactive recovery and client-perceived recovery-related justice in the emerging and developed market context. Specifically, none of the three explored cultural client orientations was found to affect client-perceived procedural justice, suggesting this dimension’s pertinence across customers of differing cultural profiles, or those across emerging and developed markets. A plausible reason is that the typically more relational/enduring or more interdependent nature of B2B (vs. B2C)-based dealings necessitates elevated levels of customer-perceived procedural fairness, irrespective of clients’ cultural orientation.

6.2 Theoretical Implications

This study yields important theoretical implications. First, we assimilate the literature streams of customers’ cultural orientation and B2B-based proactive service recovery in the emerging (vs. developed) market context, which remain disparate to-date. Specifically, we explored the effect of clients’ individualist/collectivist, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance orientation on their proactive recovery-related perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional justice and relationship quality across these markets (Luo et al., 2019). By illuminating the effect of industrial clients’ cultural orientation on proactive recovery effectiveness, this empirical study sets a pioneering milestone in the international marketing-based proactive service recovery literature across emerging/developed markets.

Second, our findings raise key issues for further inquiry. For example, little remains known regarding the effect of suppliers’ proactive recovery execution (e.g., timing/level of information offered) across emerging/developed markets, which may further affect clients’ supplier evaluations (Silva et al., 2020). Another natural progression of this work is to analyze failure severity or the duration of the client/supplier relationship and its effect on proactive recovery performance. Overall, our findings suggest that though customers’ cultural orientation may be used to segment industrial clients in supplier-instigated proactive recovery strategies, any client – regardless of his/her cultural orientation – values proactive recovery-related procedural justice, warranting its maintenance and effective management (Harper & Mustafee, 2019).

6.3 Managerial Implications

This study also yields implications for managers serving clients in emerging/developed markets. First, while it is important to minimize service failure, this is to some extent inevitable, highlighting the critical role of effective service recovery (Döscher, 2013). Our findings support the idea that proactive recovery plays a pivotal role in improving industrial client-perceived proactive recovery-related perceived justice and relationship quality in the emerging/developed market context, highlighting its strategic importance (Guchait et al., 2019). We, therefore, recommend managers to adopt a proactive (vs. reactive) recovery strategy to mitigate the effects of failure-induced damage, thus optimizing client outcomes. Proactive recovery can also be used to reduce firms’ recovery cost, as in the latter, they need to work harder to remedy customers’ already damaged satisfaction. Proactive recovery can, therefore, offer a first-mover-akin advantage where suppliers, by owning up to their (looming) failures before the customer notices these, have a strategic opportunity to boost client evaluations (Silva et al., 2020). We thus recommend the adoption of a proactive (vs. reactive) recovery strategy, given its positive expected effect on client-perceived justice and relationship quality in emerging/developed markets.

Second, our results suggest that supplier-led efforts to identify, notify, explain, and keep clients informed through the recovery process favorably impact customer-perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional justice, as well as relationship quality (Ulaga & Eggert, 2006). This finding indicates the pertinence of client-perceived fairness of proactive recovery-related processes, interactions, and outcomes, which should be considered in staff recovery training–design, monitoring, and implementation. For example, we expect employee sensitivity to clients’ cultural orientation to facilitate customer-perceived justice/relationship quality, thus further boosting proactive recovery performance.

Third, though the findings show that clients of differing cultural orientations differentially value proactive recovery-related distributive/interactional justice, procedural justice is rated equivalently across clients’ cultural orientations, or across clients in emerging/developed markets. As procedural justice was also found to exert the strongest effect on customer commitment (H4c), we recommend industrial suppliers to ensure elevated levels of client-perceived proactive recovery-related procedural justice in particular (e.g., by implementing fair, non-discriminatory recovery processes/policies across their clientele).

6.4 Limitations and Further Research

This study is also subject to several limitations, from which we identify additional research avenues. First, our analyses are drawn from a scenario-based experimental design, using two (emerging vs. developed market-based) sub-samples (i.e., from Iran/Denmark), incurring potentially limited external validity or generalizability of the findings. Thus, by using a different methodological (e.g., survey-based) approach, or by investigating industrial clients’ cultural orientation or distance in other (e.g., North American) cultures (Tower et al., 2019), future researchers may refine the reported findings. Relatedly, while we explored the effect of industrial clients’ cultural orientation on firm-based proactive recovery performance, we did not examine the firm’s cultural orientation, which may also affect its proactive recovery performance, particularly in cross-border operating firms. For example, if an individualistic firm deploys a proactive recovery strategy with collectivistic customers, their observed cultural mismatch may give rise to worthwhile future research opportunities.

Second, we used purposive sampling to collect the data. While offering a valid data collection technique (Malhotra & Birks, 2012), this approach may also limit the generalizability of the findings. We, therefore, advise researchers to deploy simple random sampling to collect their data. Moreover, though we attained 117 valid Danish and 109 Iranian responses, further research may wish to replicate our work by drawing on larger samples (e.g., n>200).

Third, though we explored the effect of a supplier’s proactive recovery activity on client-perceived justice/relationship quality, alternate dependent variables may be used, including customer experience, engagement, or brand love (e.g., Hollebeek, 2018). Moreover, additional factors, including client/supplier relationship depth or failure severity, or further (e.g., digital) contexts, are candidates for further exploration.

References

Adams, J. (1965). Inequity in Social Exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–299.

Baliga, A., Chawla, V., Sunder, V., Ganesh, L. & Sivakumaran, B. (2020). Service Failure and Recovery in B2B Markets: A Morphological Analysis. Journal of Business Research, 131(Jul), 763–781.

Britannica. (2022). Economy of Denmark. https://www.britannica.com/place/Denmark/Economy

Borah, S., Prakhya, S., & Sharma, A. (2019). Leveraging service recovery strategies to reduce customer churn in an emerging market. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48, 848–868.

Bouazzaoui, M., Wu, H., Roehrich, J., Squire, B., & Roath, A. (2020). Justice in inter-organizational relationships: A literature review and future research agenda. Industrial Marketing Management, 87(May), 128–137.

Casidy, R., Duhachek, A., Singh, V., & Tamaddoni A. (2021). Religious Belief, Religious Priming, and Negative Word of Mouth. Journal of Marketing Research, 58(4), 762–781.

Chi, C., Wen, B., & Ouyang, Z. (2020). Developing relationship quality in economy hotels: The role of perceived justice, service quality, and commercial friendship. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(8), 1027–1051.

Doney, P. & Cannon, J. (1997). An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller Relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 35–51.

Döscher, K. (2013). Recovery Management: Conceptual Dimensions, Relational Consequences and Financial Contributions. Ingolstadt, Germany: Springer.

Duffy, R., Fearne, A., Hornibrook, S., & Hutchinson, K. (2013). Engaging suppliers in CRM: The role of justice in buyer–supplier relationships. International Journal of Information Management, 33(1), 20–27.

Fillieri, R. & Mariani, M. (2021). The role of cultural value in consumers’ evaluation of online review helpfulness: A big data approach. International Marketing Review, 38(6), 1267–1288.

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Giovanis, A., Athanasopoulou, P., & Tsoukatos, E. (2015). The role of service fairness in the service quality-relationship quality-customer loyalty chain: An empirical study. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 25(6), 744–776.

Guchait, P., Han, R., Wang, X., Abbott, J., & Liu, Y. (2019). Examining stealing thunder as a new service recovery strategy: Impact on customer loyalty. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 931–952.

Guo, L., Hu, X., Lu, J. and Ma, L. (2021). Effects of customer trust on engagement in live streaming commerce: mediating role of swift guanxi. Internet Research, 31(5), 1718–1744.

Harper, A. & Mustafee, N. (2019). Proactive service recovery in emergency departments: A hybrid modelling approach using forecasting and real-time simulation. Proceedings of 2019 ACM SIGSIM Conference on Principles of Advanced Discrete Simulation, 201–204, https://doi.org/10.1145/3316480.3322892

Heydari, A., Laroche, M., Paulin, M., & Richard, M. (2021). Hofstede’s individual-level indulgence dimension: Scale development and validation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62(Sep), 102640.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values. Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2015). The Hofstede Centre: Strategy, Culture, Change.

Hofstede, G. & Hofstede, G. (2005). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede Insights (2021). Country comparison: Denmark vs. Iran. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/denmark,iran/.

Hogreve, J., Bilstein, N., & Mandl, L. (2017). Unveiling the Recovery Time Zone of Tolerance: When Time Matters in Service Recovery. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45, 866–883.

Hollebeek, L. (2018). Individual-level cultural consumer engagement styles: Conceptualization, propositions, and implications. International Marketing Review, 35, 42–71.

Hollebeek, L. (2019). Developing business customer engagement through social media engagement-platforms: An integrative S-D logic/RBV-informed model. Industrial Marketing Management, 81(Aug), 89–98.

Hollebeek, L., & Macky, K. (2019). Digital Content Marketing’s Role in Fostering Consumer Engagement, Trust, and Value: Framework, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 45(1), 27–41.

Hoppner, J., Griffith, D., & Yeo, C. (2014). The intertwined relationships of power, justice and dependence. European Journal of Marketing, 48(9/10), 1690–1708.

Horváth, C., Adigüzel., F., & Herk, H. V. (2013). Cultural Aspects of Compulsive Buying in Emerging and Developed Economies: A Cross Cultural Study in Compulsive Buying. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 4(8), 8–24.

Koc, E. (2017). Service Failures and Recovery in Tourism and Hospitality: A Practical Manual. European Journal of Tourism Research, 21, 158–160.

Kotabe, M., Dubinsky, A., & Lim, C. (1992). Perceptions of organizational fairness: A cross-national perspective. International Marketing Review, 9(2), 41.

Kotler, P. (1994). Marketing Management. Prentice-Hall.

Luo, A., Guchait, P., Lee, L., & Madera, J. (2019). Transformational leadership and service recovery performance: The mediating effect of emotional labor and the influence of culture. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77(Jan), 31–39.

Lowe, S. & Rod, M. (2020). Understanding culture as a dynamic holarchic duality. Industrial Marketing Management, 91(Nov), 82–91.

Malhotra, N., & Birks, D. (2012). Marketing Research. Winchester Business School.

Mattila, A., & Patterson, P. (2004). Service Recovery and Fairness Perceptions in Collectivist and Individualist Contexts. Journal of Service Research, 6(4), 336–346.

McCollough, M., Berry, L., & Yadav, M. (2000). An Empirical Investigation of Customer Satisfaction after Service Failure and Recovery. Journal of Service Research, 3(2), 121–137.

Mohan, M., Nyadzayo, M., & Casidy, R. (2021). Customer identification: The missing link between relationship quality and supplier performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 97(Aug), 220–232.

Monga, A., & Roedder John, D. (2007). Cultural Differences in Brand Extension Evaluation: The Influence of Analytic Versus Holistic Thinking. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(4), 529–536.

Morgan, R., & Hunt, S. (1994). The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Oflaç, B., Sullivan, U., & Aslan, Z. (2021). Examining the impact of locus and justice perception on B2B service recovery. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 36(8), 1403–1414.

Ozen, H., & Kodaz, N. (2012). Utilitarian or Hedonic? A Cross Cultural Study in Online Shopping. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 3(6), 80–90.

Park, H., Han, K., & Yoon, W. (2018). The Impact of Cultural Distance on the Performance of Foreign Subsidiaries: Evidence from the Korean Market. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 9(1), 123–134.

Patterson, P., Cowley, E., & Prasongsukarn, K. (2006). Service Failure Recovery: The Moderating Impact of Individual-Level Cultural Value Orientation on Perceptions of Justice. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(3), 263–277.

Qin, C., Remburuth, P., & Wang, Y. (2011). A Conceptual Model of Cultural Distance, MNC Subsidiary Roles, and Knowledge Transfer in China-based Subsidiaries. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 2(4), 8–27.

Rather, R., Tehseen, S., Hassan, M., & Parrey, S. (2021). Customer brand identification, affective commitment, customer satisfaction, and brand trust as antecedents of customer behavioral intention of loyalty: An empirical study in the hospitality sector. In S. Dixit, K. Lee, & P. Loo (Eds.), Consumer Behavior in Hospitality and Tourism. London: Routledge.

Rinuastuti, H., Hadiwidjojo, D., Rohman, F., & Khusniyah, N. (2014). Measuring Hofstede’s Five Cultural Dimensions at Individual Level and its Application to Researchers in Tourists’ Behaviors. International Business Research, 7(12), 143–152.

Roy, S., Gruner, R., & Guo, J. (2020). Exploring customer experience, commitment, and engagement behaviors. Journal of Strategic Marketing, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2019.1642937

Serkland (2021). Iran is not a frontier market, it is an emerging market in waiting. https://www.serklandinvest.com/insights/2021/10/14/is-iran-a-frontier-or-emerging-market.

Silva, G., Coelho, F., Lages, C., & Reis, M. (2020). Employee adaptive and proactive service recovery: A configurational perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 54(7), 1581–1607.

Skudiene, V., McCorkle, Y. L., McCorkle, D., & Blagoveščenskij, D. (2021). The Quality of Relationship with Stakeholders, Performance Risk and Competitive Advantage in the Hotel, Restaurant and Café Market. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 12(23), 198–221.

Smith, A., Bolton, R., & Wagner, J. (1999). A Model of Customer Satisfaction with Service Encounters Involving Failure and Recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(3), 356–372.

Tower, A., Hewett, K., & Fenik, A. (2019). The Role of Cultural Distance Across Quantiles of International Joint Venture Longevity. Journal of International Marketing, 27(4), 3–21.

Triandis, H. (1995). Individualism and Collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview-Press.

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1998). Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity in Global Business. McGraw-Hill.

Ulaga, W., & Eggert, A. (2006). Relationship value and relationship quality: Broadening the nomological network of business-to-business relationships. European Journal of Marketing, 40, 311–327.

Williams, D., Crittenden, V., & Henley, A. (2022). Third-party procedural justice perceptions: The mediating effect on the relationship between eWOM and likelihood to purchase. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 30(1), 86–107.

Yani-de-Soriano, M., Hanel, P., Vazquez-Carrasco, R., Cambra-Fierro, J., & Centeno, E. (2019). Investigating the role of customers’ perceptions of employee effort and justice in service recovery: A cross-cultural perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 708–732.

Ye, H., & Luo, Y. (2016). Research on the impact of service failure severity on customer service failure attribution in network shopping. WHICEB2016 Proceedings, 12.

Yoo, B., Donthu, N., & Lenartowicz, T. (2011). Measuring Hofstede’s Five Dimensions of Cultural Values at the Individual Level: Development and Validation of CVSCALE. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 23(3/4), 193–210.

Zhu, X. & Zolkiewski, J. (2015). Exploring service failure in a business-to-business context. Journal of Services Marketing, 29(5), 367–379.

Appendix

Scenarios