Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2023, vol. 14, no. 3(29), pp. 464–485 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2023.14.1

The Impact of Perceived Procedural Justice on Dimensions of Customer Citizenship Behaviours: The Mediating Effect of Customer Perceived Support

Ahmed Hassaan Ali

School of Economics and Management, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Faculty of Commerce, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt

ahmed.hassan2013@commerce.aun.edu.eg

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7834-9251

Jing Song (corresponding author)

School of Economics and Management, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Key Laboratory of Service Science and Innovation of Sichuan Province, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

jsong@swjtu.edu.cn

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8764-3268

Abstract. The present study examines the influence of perceived procedural justice (PPJ) on four fundamental dimensions of customer citizenship behaviours (helping other customers, advocacy, customer tolerance, and feedback) and the mediating role of customer perceived support (CPS). Our research setting is the smartphone after-sales service sector in China. Structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS is employed to empirically test our hypotheses on the basis of survey data from 368 smartphone customers. We find that PPJ significantly contributes to the customer citizenship behaviours of helping other customers, advocacy, and feedback. Surprisingly, we do not find a significant relationship between PPJ and customer tolerance. Our evidence indicates that CPS partially mediates the relationships between PPJ and helping other customers, advocacy, and feedback, but fully mediates the effect of PPJ on customer tolerance. This research contributes to managers’ understanding of how voluntary behaviours can be effectively managed by enhancing PPJ and CPS. Further, it enriches our theoretical understanding of key antecedents of customer citizenship behaviours.

Keywords: perceived procedural justice, customer citizenship behaviours, customer tolerance, customer perceived support, smartphone after-sales service, China

Received: 8/11/2022. Accepted: 14/8/2023

Copyright © 2023 Ahmed Hassaan Ali, Jing Song. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

The smartphone sector has witnessed growth in the Chinese market. According to the statistics announced in the first two months of 2022, China’s smartphone production volume was approximately 212.7 million units. Furthermore, China produced about 1.5 billion smartphones in 2020. China’s domestic mobile phone industry represents one of the largest industries in the world, and it is expected to continue to grow gradually. In October 2021, smartphone subscribers in China numbered around 1.6 billion, with a monthly growth rate of a few million subscribers (Daniel, 2022). In terms of software systems, iOS and Android maintained their market dominance, with over 21% and 78% of the mobile phone operating system market share in China, respectively (Daniel, 2022), which resulted in intense competition in this sector. Thus, smartphone businesses today take customer relations and after-sales service very seriously, as a great customer experience increases the return rate of the customers.

Services differ from products in that they need consumer interaction throughout service delivery, are more intangible and heterogeneous, and are generated and consumed at the same time (Groth & Gilliland, 2001). As a result, the service experience, or the customer’s perception of service delivery, is frequently a critical standard (Bitner et al., 1990). Consequently, when evaluating the quality of a service, customers pay more attention to delivery-related aspects like procedural justice (Fisk et al., 1993). Moreover, customers experience numerous ‘moments of truth’ when dealing with service organisations. These are times when customers interact with a representative of the service organisation and assess the interaction in terms of the justice of the service delivery and the manner in which they were treated (Fisk et al., 1993).

There has been much discussion in the literature about ‘perceived procedural justice’ (PPJ) and its effect on marketing outcomes such as behavioural intentions, customer emotions, satisfaction, customer affection, and relationship quality, and research has identified a strong influence on reactions to the service delivery process (Ali et al., 2022; Chang et al., 2012; Choi & Choi, 2014; La & Choi, 2019; Namkung & Jang, 2010; Nikbin et al., 2016; Ortiz et al., 2017; Singh & Crisafulli, 2016). Further, Chebat and Slusarczyk (2005) reveal that people’s perceptions of justice affect their emotional reactions, such as happiness, and anger, which in turn affect loyalty.

On the other hand, a growing number of studies have investigated the effect of PPJ on employee citizenship behaviour (Lim & Loosemore, 2017; Rahman & Karim, 2022; Seth et al., 2022; Song et al., 2012; Van Dijke et al., 2012), relying on theories of social exchange (Blau, 1964) and equity (Adams, 1965). However, few studies have examined the effect of customer perceived justice (CPJ) on customer citizenship behaviours (CCBs) (Choi & Lotz, 2018; Cintamür, 2022; Kim et al., 2018; Tonder & Petzer, 2022; Yi & Gong, 2006). Although prior studies of CPJ and CCBs are valuable, they have numerous significant limitations. First, there is still debate over the direct effect of PPJ on the various dimensions of CCBs. For example, most studies of CPJ and CCBs (Kim et al., 2018; Tonder & Petzer, 2022; Yi & Gong, 2006) address overall CCB. Yi and Gong (2013) propose that the fundamental dimensions of CCB are helping, advocacy, tolerance, and feedback. Further, of the three types of justice (interactional, procedural, and distributive) the direct effect of PPJ on the dimensions of CCBs has not been sufficiently examined in the services marketing literature.

Second, whereas in the context of employment there is conceptual awareness of the role of perceived support in the relationship between PPJ and organisational citizenship behaviour (Dominic et al., 2021; Moorman et al., 1998), no empirical studies in the marketing literature have investigated the role of customer perceived support (CPS) in the PPJ–CCBs relationship. Recent research has shown that CPS is positively impacted by overall CPJ (Choi & Lotz, 2018), and CPS is considered a vital antecedent of customer voluntary performance (i.e., citizenship behaviours) (Bettencourt & Brown, 1997; Ning & Hu, 2022; Rosenbaum & Massiah, 2007), which implies a possible mediating effect of CPS in the PPJ–CCBs relationship—an effect that has not yet been investigated.

Finally, despite the significance of PPJ as a key antecedent of CCBs, this relationship has not yet been tested in the context of the smartphone after-sales service industry. The current research addresses this deficit by experimentally investigating the role of PPJ in enhancing CCBs in China’s smartphone after-sales service. The present research addresses three research questions as follows: (1) Does PPJ directly influence the four fundamental dimensions of CCBs (helping, advocacy, tolerance, and feedback)? (2) Does CPS directly influence the dimensions of CCBs? (3) Does CPS have any mediating effects between PPJ and the dimensions of CCBs (helping, advocacy, tolerance, and feedback)?

This research is organized as follows: The following section gives a succinct overview of the theoretical underpinnings, and Section 3 discusses the study hypotheses. Section 4 presents the study’s methodology. Section 5 reports the findings, while the findings are discussed in Section 6. Section 7 reports the theoretical and managerial implications. Finally, Section 8 offers limitations and recommendations.

2. Theoretical Underpinnings

2.1 Perceived Procedural Justice (PPJ)

During the delivery of services, customers regard justice as an issue of whether a service organization has met its responsibility to achieve the outcomes and benefits it promised to provide (Yi & Gong, 2008). Customers’ expectations are focused on both the promised advantages and the way in which these benefits are offered (Bowen et al., 1999). Procedural fairness in a service delivery setting describes the perceived justice of the organization’s policies and procedures (Voorhees & Brady, 2005; Yi & Gong, 2008). In addition, Tax et al. (1998) identified procedural fairness as a relevant and critical component in the context of customer-service provider exchanges for service organizations. According to Gokmenoglu and Amir (2021), procedural fairness is related to the justice of procedures used to provide a result; consequently, it is associated with the actions performed by service providers. Procedural justice involves issues such as the helpful behaviour of service staff, the duration of waiting for the service, the efficiency of service, and the handling of unusual requests (Bowen et al., 1999; Cintamür, 2022). Leventhal (1980) argued that PPJ is enhanced when consumers perceive that the procedures necessary for the desired result are accurate and consistent.

Hence, in line with the arguments preceded above, the authors define PPJ as consumers’ perceptions of justice relating to the procedures and policies of the after-sale services provided by smartphone organizations.

2.2 Customer Perceived Support (CPS)

CPS is an adaptation of the concept of perceived organisational support for employees, applied to the interactions between an organisation and its customers (Bettencourt & Brown, 1997). It is founded on organisational support theory (Eisenberger et al., 1986), which holds that employees construct opinions about how much a firm values their contributions and cares about their well-being to evaluate whether the company will reward additional employee effort (Eisenberger et al., 1997). Similar to employees, customers may also construct opinions about the organisation’s support. Customers may experience improved service delivery as a result of knowing that the firm recognises and appreciates their performance (Im & Qu, 2017; Keh & Wei Teo, 2001). According to Yi and Gong (2009), CPS is ‘the degree that a firm values the contributions of its consumers and cares about their well-being’. Customers perceive the organisation’s support via various factors, such as its policies on responsiveness to customers’ needs, employees’ fair and honest behaviour, and staff voluntarism (Im & Qu, 2017).

2.3 Customer Citizenship Behaviours (CCBs)

Because CCBs play a crucial role in generating competitive advantage, they have attracted the interest of academics, and an increasing number of studies are being carried out (Zhu et al., 2021). The term CCBs is derived from organisational citizenship behaviour. Customers are increasingly being viewed as ‘partial employees of the firm’ by academics (Bowen et al., 2000). As defined, CCBs are voluntary and discretionary behaviours that are not required for the effective production and/or delivery of the service but that, generally, assist the service firm (Groth, 2005; Zhu et al., 2016). CCBs are voluntary (extra-role) actions that customers take during or after the service delivery phase (Nguyen et al., 2014).

Yi and Gong (2013) have demonstrated that CCBs consist of the following four aspects: (1) Helping refers to ‘customer behaviours aimed at helping other customers to search for service information and clarify how to utilise it in a correct manner’ (Yi & Gong, 2013). Rosenbaum and Massiah (2007) contend that by being helpful, customers show empathy for other consumers. Help from prior customers decreases the time and effort put in by new customers and enhances the value they get from services (Liao et al., 2023; Thompson et al., 2016). (2) Advocacy refers to consumers actively recommending services to friends, colleagues, or other individuals (Groth, 2005). Customers are a cheap source of recommendations and may be experts on other customers’ perspectives (Bettencourt, 1997). Organisations should therefore make the most of this vital information source (Keh & Wei Teo, 2001). (3) Tolerance denotes the willingness of the customer to remain flexible when the service does not match their expectations of service quality, like in the instance of delays (Yi & Gong, 2013). (4) Feedback refers to consumers offering the organisation suggestions for service improvements to assist the firm in enhancing the way services are delivered (Groth, 2005; Hui & Wenan, 2022; Yi & Gong, 2008).

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1 Perceived Procedural Justice (PPJ) and Customer Citizenship Behaviours (CCBs)

Organisational behavior literature reveals that procedural fairness perception influences the behavioral responses of individuals (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001). An increasing number of organisational studies have investigated the effect of PPJ on employee citizenship behaviour and have identified a link between procedural justice and citizenship behaviour (Nguyen & Tran, 2022; Ramdeo & Singh, 2019). The theories of social exchange (SET) and equity provided strong support for explaining the relationship between them. According to SET, individuals seek to reciprocate with those who have helped them. One type of behaviour that employees display to reward those who benefit them is organisational citizenship behaviour (Tansky, 1993). In addition, equity theory posits that individuals will feel stress in the presence of injustice and will seek to resolve it (Adams, 1965). Masterson (2001) claims that if employees believe they are treated fairly in the workplace, they will be loyal to the company and feel obligated to reciprocate by giving something of value in return. By adopting this logic to the context of the consumer, it becomes clear that if customers feel that a firm treats them fairly, they will prefer to express their gratitude by displaying CCB in order to maintain the social exchange. Some prior empirical investigations examined the vital role of perceived justice and its influence on customer citizenship behaviours in various industries. Earlier studies have adopted the justice theory to seek the antecedents of CCBs. The empirical findings (Yi & Gong, 2008; Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara et al., 2015) demonstrate that guests’ perceptions of the fairness of the treatment they received from hotel staff during the service interaction prompt them to participate in citizenship behaviours. Besides, Ortiz et al. (2017) confirmed that a customer’s perception of justice might affect their psychology and could lead to behavioural responses from customers towards the organization.

In contrast, most marketing studies focus on the connection between overall perceived justice or interactional justice and CCBs (Choi & Lotz, 2018; Yi & Gong, 2006). Therefore, attention has not been placed on the influence of PPJ on the dimensions of CCBs in the context of customers. Drawing on the theories of SET and equity, our investigation argues that when customers perceive the policies and procedures of the smartphone after-sales service as fair, this leads them to reciprocate towards this organisation with increased citizenship behaviours (e.g., helping other customers, advocacy, customer tolerance, and feedback). Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a. PPJ positively affects helping other customers.

H1b. PPJ positively affects advocacy.

H1c. PPJ positively affects customer tolerance.

H1d. PPJ positively affects feedback.

3.2 PPJ and Customer Perceived Support (CPS)

Research indicates that fair treatment enhances the creation of social exchange relationships (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). More specifically, how fairly firms treat their staff members (i.e., organisational justice) might indicate the extent to which individuals perceive that the corporation cares about their welfare and supports them (i.e., perceived organisational support, POS) (Herda & Lavelle, 2011). Several scholars in organisational behaviour have proven that PPJ affects POS positively and have regarded it as a vital antecedent of POS (e.g., DeConinck, 2010; Dominic et al., 2021; Loi et al., 2006; Masterson et al., 2000; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). In keeping with the organisational support theory (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Shore & Wayne, 1993), the POS of individuals might be influenced by the corporation’s actions based on how the staff members perceive organisational procedures. By expanding this logic to the consumer context, researchers in consumer behaviour studies (Choi & Lotz, 2018) have revealed that customers’ perceptions of fairness through service providers boost their perceptions of support from those firms. Furthermore, a recent investigation in the tourism marketing field demonstrates even more evidence that PPJ influences perceived support. A survey of a sample of 453 Gulangyu Island inhabitants in China confirmed that PPJ positively impacts perceived community support (Su et al., 2019). The following hypothesis can therefore be made in light of the theoretical discussion and study data shown above:

H2. PPJ positively affects CPS.

3.3 CPS and CCBs

According to organisational support theory (OST), workers act in line with the reciprocity principle (Chen et al., 2009). In a similar manner, OST can be applied to the customer context, to posit that when an organisation cares about the requirements of its customers, values their opinions, acts in their best interests, and provides the best service it can, leading customers to perceive support from the organisation, customers who perceive organisational support may cultivate positive thoughts and feelings that may influence their assessment of the organisation because of the reciprocity principle (Keh & Wei Teo, 2001). Bettencourt (1997) and Rosenbaum and Massiah (2007) provided evidence that organisational support impacts consumer feedback, suggestions, and word-of-mouth recommendations. Crocker and Canevello (2008) demonstrated the perceived support from others leads people to reciprocate with similar supportive behaviours. In accordance with social exchange theory, customers exhibit positive behaviours when they believe that businesses offer good social support during the consumption process (Ning & Hu, 2022). Similarly, theories of organisational climate and social support predict that supportive climates enhance customer voluntary behaviours (Liao et al., 2022; Schneider, 1990), and Ning and Hu (2022) demonstrate that social support has a significant effect on consumer citizenship behaviour.

Previous studies on CPS and CCB have been limited to discussing overall CCB (e.g., Ning & Hu, 2022) or focussing on particular dimensions of CCBs (e.g., Bettencourt & Brown, 1997). The current study examines the correlations between CPS and various dimensions of CCBs in the after-sales service industry. Based on the above theories and studies, the authors propose the following hypotheses:

H3a. CPS positively affects helping other customers.

H3b. CPS positively affects advocacy.

H3c. CPS positively affects customer tolerance.

H3d. CPS positively affects feedback.

3.4 The Mediating Role of CPS

In the organisational literature, prior studies have demonstrated that POS mediates the relationship between organisational justice and organisational citizenship behaviour (Noruzy et al., 2011). More specifically, Moorman et al. (1998) and Dominic et al. (2021) have revealed that POS mediates the relationship between procedural justice and organisational citizenship behaviour. However, prior studies have not investigated the role of CPS in the PPJ–CCBs relationship in the customer context, although the marketing literature shows that customer perceived justice positively affects CPS (Choi & Lotz, 2018) and CCBs (Tonder & Petzer, 2022) and that CPS positively affects CCBs (Ning & Hu, 2022). Consequently, both PPJ and CPS are vital elements for enhancing CCBs. Therefore, we suggest that CPS may be an underlying mechanism by which PPJ affects the various dimensions of CCBs. Thus, the authors propose the following hypotheses:

H4a. CPS mediates the relationship between PPJ and helping other customers.

H4b. CPS mediates the relationship between PPJ and advocacy.

H4c. CPS mediates the relationship between PPJ and customer tolerance.

H4d. CPS mediates the relationship between PPJ and feedback.

4. Methodology

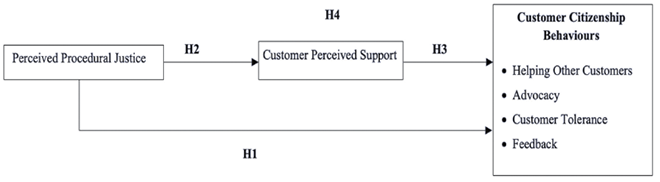

4.1 Conceptual Framework

Our research model is based on an analysis of the theoretical literature discussed above. It comprises three parts: PPJ is the independent variable; CPS is the mediator in our model; and the dimensions of CCBs (helping other customers, advocacy, customer tolerance, and feedback) are dependent variables. The conceptual framework is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Conceptual Framework

4.2 Population and Sample

We used a specialised online survey website (e.g., Credamo) and some Chinese social media platforms (Weibo, WeChat, and Baidu Tie Ba) to collect data from users of smartphone after-sales services in Chengdu, China. In total, 391 completed questionnaires were collected between September and November 2021. We employed a strict screening procedure to remove questionnaires with blatant regularity or brief response times, and so we excluded 23 questionnaires. Therefore, 368 valid questionnaires are included in our analysis. The sample size was determined based on Thompson’s equation (n = 384.144; probability 50%; confidence level 95%; error proportion (0.05); population size = 9,306,000) (Thompson, 2012, pp. 59–60).

4.3 Study Design

The primary method of gathering data is the online questionnaire. We used scales that had high confidence and validity ratings based on prior studies. The first section requested respondents’ demographic data. The second section used a Likert scale with a 5-point range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

4.4 Study Instruments

The scales for the six types of variables used in this study are as follows:

Perceived Procedural Justice (PPJ): We adapted a three-item scale developed by Maxham and Netemeyer (2002) and Voorhees and Brady (2005) to measure PPJ. We obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.846. A sample item is “The mobile phone brand has fair practises and policies for dealing with users”.

Customer Perceived Support (CPS): We adapted the three-item scale of Choi and Lotz (2018) to measure CPS. We obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.878. A sample item is “The service provider really cares about my well-being”.

Helping Other Customers (HC): We adapted the four-item scale of Yi and Gong (2013) to measure HC. We obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.875. A sample item is “I have helped other customers when they seemed to have problems”.

Advocacy: We adapted the three-item scale of Yi and Gong (2013) to measure advocacy. We obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.897. A sample item is “I have said positive things about this brand to others”.

Customer Tolerance: We adapted the 3-item scale of Yi and Gong (2013) to measure customer tolerance. We obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.768. A sample item is “I have put up with the situation when the after-sales services were not delivered as expected”.

Feedback: We adapted the three-item scale of Yi and Gong (2013) to measure feedback. We obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.813. A sample item is “When I experienced a problem, I let the service provider of this brand know about it”.

The questionnaire was developed in English and then translated into Chinese. A pilot version of the survey was exhibited to a group of participants to ensure that all questions were clear, and all of their suggestions and observations were taken into consideration.

4.5 Analysis Techniques

We summarised and analysed the data via AMOS v. 24 and SPSS v. 26 statistical software. The hypotheses were empirically examined through structural equation modeling (SEM). As proposed by Preacher and Hayes (2008), the mediation model was also evaluated utilising bootstrapping analysis via AMOS.

5. Results

5.1 Measurement Model

The 368 questionnaire responses were analysed in AMOS using SEM. In the first stage, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was run to check the model fit and validity, and the CFA indices showed good model fit (p-value = .000; minimum discrepancy divided by degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) = 2.221 < 3; goodness of fit index (GFI) = .922 ≥ .90; comparative fit index (CFI) = .959 ≥ .90; TLI (Tucker-Lewis’s index) = .948 > .90; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .058 < .08; normed fit index (NFI) = .928 > .90; adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) = .890 > .80; root mean square residual (RMR) = .040 closer to 0).

5.2 Common Method Bias (CMB)

CMB was statistically examined in the current investigation. Harman’s one-factor test was conducted utilising the unrotated factor solution. The findings revealed that the CMB issue with the data was not serious, with a variance explained of 35.90% (< 50%) (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

5.3 Reliability and Validity Analysis

Table 1 shows constructs’ factor loadings, which are all above 0.50. Therefore, the results exhibit convergent validity, in line with Gerbing and Anderson (1988). The reliability of the constructs was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α). As illustrated in Table 1, an acceptable degree of reliability was achieved since all construct values are greater than 0.70 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The reliability and validity of the constructs were estimated through the composite reliability (CR) approach (Brunner & Sub, 2005), as seen in Table 1. The constructs’ CR values are higher than the required level of > 0.60. To further confirm the validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) was computed. In accordance with Hair et al. (2010), obtaining values > 0.50 demonstrates good construct validity.

Table 1

Construct Validity and Reliability

|

Q |

M |

SD |

FL |

α |

CR |

AVE |

|

PPJ Q1

Q2

Q3 |

3.75

3.78

3.84 |

.827

.766

.752 |

.701

.831

.897 |

.846

|

0.853 |

0,662 |

|

CPS Q4

Q5

Q6 |

3.37

3.22

3.35 |

.864

.865

.894 |

.800

.888

.839 |

.878

|

0.880 |

0.711 |

|

HC Q7

Q8

Q9

Q10 |

3.59

3.63

3.78

3.60 |

.813

.795

.885

.902 |

.893

.877

.743

.686 |

.875

|

0.871 |

0.633 |

|

Advocacy Q11

Q12

Q13 |

3.69

3.85

3.91 |

.970

.891

.855 |

.839

.939

.828 |

.897

|

0.903 |

0.757 |

|

Tolerance Q14

Q15

Q16 |

3.13

3.33

3.20 |

.951

.900

.928 |

.737

.739

.703 |

.768

|

0.770 |

0.528 |

|

Feedback Q17

Q18

Q19 |

3.45

3.68

3.49 |

.878

.763

.880 |

.823

.724

.763 |

.813 |

0.815 |

0.595 |

Note. PPJ = Perceived Procedural Justice; CPS = Customer Perceived Support; HC = Helping other Customers; M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation; FL = Factors loading; α = Cronbach’s alpha; CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted.

Two methods were used to evaluate discriminant validity. First, in line with Fornell and Larcker (1981), we tested whether all the off-diagonal correlations for a given construct are less than the square root of the AVE for that construct on the diagonal. The outcomes reveal the squared AVE is larger than the squared correlations for all variables, indicating a satisfactory level of discriminant validity. Second, we employed the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) method (Henseler et al., 2015). The value of HTMT below the maximum threshold of 0.85 indicates satisfactory discriminant validity. As seen in Table 2, all HTMT values fall below 0.62, demonstrating good discriminant validity.

Table 2

HTMT Results

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

1. PPJ 2. CPS 3. HC 4. Advocacy 5. Tolerance 6. Feedback |

0.497 0.467 0.392 0.271 0.461 |

0.532 0.469 0.614 0.596 |

0.581 0.457 0.502 |

0.467 0.410 |

0.592 |

|

Note. PPJ = Perceived Procedural Justice; CPS = Customer Perceived Support; HC = Helping other Customers; HTMT = Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio. Source: calculated by the authors using AMOS v. 24.

5.4 Demographic Profile

Respondents in this study were different-aged Chinese customers. The distribution of gender was nearly equal: 43.75% female, 56.25% male. Around two-thirds of the participants were between the ages of 21 and 40 (67.39%). Table 3 shows the demographic profile.

Table 3

Demographic Profile

|

Variable |

Type |

N |

% |

|

Gender |

Male Female |

207 161 |

56.25 43.75 |

|

Age |

Under 20 20-30 31-40 41-50 Above 50 |

45 183 65 55 20 |

12.23 49.72 17.66 14.94 5.43 |

|

Education |

Under High School High School Bachelor’s Master’s and Higher |

9 31 230 98 |

2.44 8.42 62.5 26.63 |

|

Brand of smartphone |

HUAWEI OPPO Xiaomi or Redmi iPhone Others |

130 30 56 126 26 |

35.32 8.15 15.21 34.23 7.06 |

Source: Calculated by the authors.

5.5 Structural Model

The hypothesised model offered an acceptable fit to data (CMIN/DF = 2.560 < 3.00; p-value < .001; GFI = .907 ≥ .90; CFI = .945 ≥ .90; NFI = .914 > .90; TLI = .934 > .90; RMR = .062 closer to 0; IFI = .945 > .90; RMSEA = .065 < .08).

5.6 Hypotheses Testing

The SEM approach was used to examine direct effects. Table 4 reports results for hypothesised direct effects. We find a statistically significant impact of PPJ on HC (Std. β = 0.230, p < 0.01), confirming H1a. PPJ statistically significantly affects advocacy (Std. β = 0.188, p < 0.05), confirming H1b. PPJ also statistically significantly affects feedback (Std. β = 0.201, p < 0.05), confirming H1d. However, the results show that PPJ is not significantly related to customer tolerance. Thus, H1c is rejected. A statistically significant impact of PPJ on CPS is observed (Std. β = 0.474, p < 0.01), supporting H2. The effects of CPS on both customer-oriented dimensions of CCBs, helping other customers and advocacy, are significant (Std. β = 0.454, p < 0.01; Std. β =0.387, p < 0.01, respectively); thus, H3a and H3b are supported. CPS is also significantly related to firm-oriented dimensions of CCBs, customer tolerance, and feedback (Std. β = 0.659, p < 0.01; Std. β=0.538, p < 0.01 respectively); therefore, H3c and H3d are supported.

Table 4

Test Results for Hypothesized Direct Effects

|

Hypothesis |

Path |

Std. β |

CR |

P |

Supported / |

|

H1 H1a H1b H1c H1d H2 H3 H3a H3b H3c H3d |

PPJ -> HC PPJ -> Advocacy PPJ -> Tolerance PPJ -> Feedback PPJ -> CPS

CPS -> HC CPS -> Advocacy CPS -> Tolerance CPS -> Feedback |

.230 .188 .004 .201 .474

.454 .387 .659 .538 |

3.940 3.079 -.502 3.333 8.046

7.439 6.118 8.914 8.186 |

.007** .033* .757 ns .014* .001**

.001** .001** .001** .001** |

Supported Supported Not supported Supported Supported

Supported Supported Supported Supported |

Note. * = p-value < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01. PPJ = Perceived Procedural Justice; CPS = Customer Perceived Support; HC = Helping Other Customers; ns = Non-Significant; CR = Composite Reliability. Source: Calculated by authors by using AMOS v.24.

5.7 Testing Mediating Effect of CPS

The mediating effect of CPS is tested using the bootstrapping procedures in AMOS v.24. According to Preacher and Hayes (2008, p. 883), “the bootstrapping analysis testing indirect effects gives a rigorous test of mediation and generates empirical evidence”. The findings of our bootstrapping analysis with 2,000 samples identify the effects, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values for indirect impacts in our model. To obtain a bias-correlated confidence interval and execute significance tests, the bias-correlated percentile approach is utilised. Results are reported in Table 5.

We find a statistically significant effect of PPJ on helping other customers that is partially mediated by CPS (PPJ -> CPS -> HC) (0.226; p < 0.01). The effect of PPJ on advocacy partially mediated by CPS (PPJ -> CPS -> advocacy) is statistically significant (0.221; p < 0.01). The effect of PPJ on tolerance fully mediated by CPS (PPJ -> CPS -> tolerance) is statistically significant (0.337; p < 0.01). Finally, the effect of PPJ on feedback partially mediated by CPS (PPJ -> CPS -> feedback) is also statistically significant (0.270; p < 0.01).

Table 5

Bootstrapped Mediation Results

|

H |

Path |

Estimate |

95% CI |

P-valve |

Relationship |

|||

|

Total |

Direct |

Indirect |

Lower |

Upper |

||||

|

H4a

H4b

H4c

H4d |

PPJ -> CPS -> HC PPJ -> CPS -> Advocacy PPJ -> CPS -> Tolerance PPJ -> CPS -> Feedback |

0.456

0.409

0.337

0.471 |

.230

.188

-

.201 |

.226

.221

.337

.270 |

.145

.136

.231

.184 |

.328

.347

.491

.381 |

.001**

.001**

.001**

.001** |

Partial Partial Full Partial |

Note. ** = p-value < 0.01. PPJ = Perceived Procedural Justice; CPS = Customer Perceived Support; HC = Helping other Customers; CI = Confidence Intervals. Source: Calculated by authors by using AMOS v.24.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Results from testing H1 reveal that PPJ has a positive effect on three of the four dimensions of CCBs (helping other customers, advocacy, and feedback). This finding can be explained by social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), which argues that individuals desire to reciprocate to people who have helped them. Thus, an organisation’s efforts to meet customers’ needs for procedural justice make customers more inclined to engage in citizenship behaviours (Yi & Gong, 2006). Our findings are consistent with existing literature, such as Choi and Lotz (2018), who similarly find that customers’ perceived justice impacts their citizenship behaviours. On the other hand, we find that PPJ does not have a significant relationship with customer tolerance, which suggests that customers seek to receive their service as expected, regardless of their level of PPJ. That result is consistent with Yi and Gong (2008), who found no evidence that perceived justice directly impacts CCBs.

We also find that PPJ positively affects CPS (H2). This result agrees with organisational support theory, which claims that perceived organisational support increases when individuals receive positive treatment from a firm (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Shore & Wayne, 1993). Extending this theory to the customer context, when customers receive positive procedural justice from a firm, they perceive greater levels of organisational support. This finding also aligns with past research such as the study by Su et al. (2019), which similarly finds that perceived justice impacts CPS.

Our findings also illustrate the positive effects of CPS on the dimensions of CCBs (H3). Our results can be explained by the theories of organisational support (Chen et al., 2009) and social exchange (Blau, 1964). Customers who recognise the support provided by a firm are more motivated to engage in voluntary behaviours that show their citizenship towards that firm by helping other customers, advocacy, tolerance, and feedback (Keh & Wei Teo, 2001). Further explanation of these results is found in organisational climate theory (Liao et al., 2022; Schneider, 1990; Shumaker & Brownell, 1984), which argues that supportive climates enhance customer citizenship behaviours. This result is consistent with prior studies (Bettencourt & Brown, 1997; Ning & Hu, 2022) revealing the positive effects of CPS on dimensions of CCBs. Thus, high levels of CPS are thought to create feelings of obligation in customers to exhibit more voluntary behaviours.

The existing marketing literature has not examined the mediating role of CPS in the relationship between PPJ and CCBs. Thus, an important contribution of the current study is verifying the mediating role of CPS in relationships between PPJ and dimensions of CCBs (H4). We observe that CPS partially mediates the relationships between PPJ and helping other customers, advocacy, and feedback. This finding is consistent with the organisational literature, such as Moorman et al. (1998) and Dominic et al. (2021), who show that organisational support mediates the relationship between procedural justice and organisational citizenship behaviour. On the other hand, CPS fully mediates the relationship between PPJ and tolerance, implying that PPJ in the after-sales service causes customers to perceive support from the company, which causes customers to display tolerance behaviour.

7. Contribution and Implications

7.1 Theoretical Contribution

This paper’s findings have several significant theoretical implications for the literature on customer citizenship behaviours. The current research claims its novelty in investigating CCBs from the perspectives of perceived procedural justice and customer perceived support in the after-sales services field. Our investigation confirms the vital roles of PPJ and CPS in improving CCBs (helping other customers, advocacy, customer tolerance, and feedback).

The research expands the studies on perceived procedural justice in the smartphone after-sales service context and enriches the studies on the factors that drive customer citizenship behaviour. At present, existing studies on the effect of perceived justice on CCBs mainly focus on overall customer perceived justice (Choi & Lotz, 2018) and interactional justice (Yi & Gong, 2006). Thus, this paper sheds light on PPJ and how it could impact each one of the CCBs’ dimensions individually.

Furthermore, drawing on the theories of social exchange and organisational support, the present analysis extends knowledge of the crucial role of CPS in the after-sales services context by exploring the effect of PPJ on the dimensions of CCBs through the mediation mechanism of CPS. Hence, these results provide a comprehensive answer to how PPJ influences CCBs. This contributes to extending the existing literature on CCBs, which thus enriches the research context of PPJ and the existing theories on the factors that boost customer citizenship behaviours.

Lastly, the present findings contribute to the customer behaviour literature by confirming the relevance of the theories of organisational support, equity, social exchange, and organisational climate in predicting the links between PPJ, CPS, and dimensions of CCBs.

7.2 Managerial Contribution

This study offers practical implications for managers of smartphone after-sales services to enhance effective strategies to improve customer citizenship behaviours. According to the present investigation results, customers reward organisations that care about procedural fairness and customer support by helping other customers, engaging in advocacy, tolerating the organisation if its service fails to meet their expectations, and providing constructive feedback. Thus, after-sales service managers should reinforce procedural fairness in order to improve CCBs. When customers perceive the service delivery procedures and policies as fair, that will motivate them to participate in citizenship behaviours towards their organisation. Therefore, managers of after-sales service should clearly explain the procedures and make certain the process is fair and clear, with the aim of enhancing CPS, which in turn boosts CCBs.

Based on the present results, after-sales service managers should pay more attention to increasing customer support to enhance customer voluntary behaviours since these factors are positively associated with CPS. Thus, smartphone firms should establish a mechanism for encouraging after-sales service individuals to provide higher levels of support to customers.

Finally, the present analysis shows a vital result that customers become more tolerant of smartphone organisations that care about customer support. Hence, to improve CPS (Cintamür, 2022), service managers should create communication programmes that convey that the service corporation cares about the customers’ suggestions and well-being and is ready to solve every problem related to service delivery.

8. Limitations and Recommendations

This research makes a vital contribution to the growing literature on the use of PPJ as a marketing tool that contributes to creating competitive advantage by affecting customers’ voluntary behaviours (i.e., citizenship behaviours) and to investigating the mechanism behind such direct effects. Specifically, we introduce CPS as a mediating variable. This research, however, is subject to several limitations, which suggest avenues for future investigation. First, our conceptual framework does not include any moderating effects. Future research may extend the present study model by testing potential moderating variables such as relationship duration, contact frequency, and the collectivism/individualism cultural orientation, which may affect the strength or even the direction of the impact of PPJ on dimensions of CCBs. Second, we only studied the impact of overall PPJ on CCBs. Future research could investigate, in a more granular way, the impact of dimensions of PPJ (e.g., perceived wait time, waiting procedures, and efficiency) (Groth & Gilliland, 2001) on CCBs. The relative importance of each dimension of PPJ may also vary depending on the nature of the service setting. Third, the present research is a cross-sectional study. Future research may test the present model using a longitudinal research method. Finally, our research context is China, potentially restricting the generalizability of our findings to non-Chinese markets. Thus, the research model could be further tested and verified in other countries with different social, cultural, and economic contexts.

References

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity In Social Exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2(C), 267–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60108-2

Ali, M. A., Ting, D. H., Isha, A. S. N., Ahmad-Ur-Rehman, M., & Ali, S. (2022). Does service recovery matter? Relationships among perceived recovery justice, recovery satisfaction and customer affection and repurchase intentions: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Asia Business Studies. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-02-2021-0060

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment: Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378802500207

Bettencourt, L. A. (1997). Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. Journal of Retailing, 73(3), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90024-5

Bettencourt, L. A., & Brown, S. W. (1997). Contact employees: Relationships among workplace fairness, job satisfaction and prosocial service behaviors. Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90014-2

Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The Service Encounter: Diagnosing Favorable and Unfavorable Incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400105

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203792643

Bowen, D. E., Gilliland, S. W., & Folger, R. (1999). HRM and service fairness: How being fair with employees spills over to customers. Organizational Dynamics, 27(3), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-2616(99)90018-9

Bowen, D. E., Schneider, B., & Kim, S. S. (2000). Shaping Service Cultures Through Strategic Human Resource Management. In T. Swartz & D. Iacobucci (Eds.), Handbook of Services Marketing and Management (pp. 439–454). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Brunner, M., & Sub, H.-M. (2005). Analyzing the Reliability of Multidimensional Measures: An Example from Intelligence Research. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164404268669

Chang, H. H., Lai, M.-K., & Hsu, C.-H. (2012). Recovery of online service: Perceived justice and transaction frequency. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(6), 2199–2208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.027

Chebat, J.-C., & Slusarczyk, W. (2005). How emotions mediate the effects of perceived justice on loyalty in service recovery situations: An empirical study. Journal of Business Research, 58(5), 664–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.09.005

Chen, Z., Eisenberger, R., Johnson, K. M., Sucharski, L., & Aselage, J. (2009). Perceived Organizational Support and Extra-Role Performance: Which Leads to Which ? The Journal of Social Psychology,149(1), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.1.119-124

Choi, B., & Choi, B.-J. (2014). The effects of perceived service recovery justice on customer affection, loyalty, and word-of-mouth. European Journal of Marketing, 48(1/2), 108–131. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-06-2011-0299

Choi, L., & Lotz, S. L. (2018). Exploring antecedents of customer citizenship behaviors in services. Service Industries Journal, 38(9–10), 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2017.1414194

Cintamür, İ. G. (2022). Linking Customer Justice Perception, Customer Support Perception, and Customer Citizenship Behavior to Corporate Reputation: Evidence from the Airline Industry. Corporate Reputation Review, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1057/S41299-022-00141-Z

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The Role of Justice in Organizations: A Meta-Analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(2), 278–321. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2001.2958

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2008). Creating and undermining social support in communal relationships: The role of compassionate and self-image goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(3), 555–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.555

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

Daniel, S. (2022). Production of cell phones by month in China 2021-2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/226434/production-of-cell-phones-in-china-by-month/

DeConinck, J. B. (2010). The effect of organizational justice, perceived organizational support, and perceived supervisor support on marketing employees’ level of trust. Journal of Business Research, 63(12), 1349–1355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.01.003

Dominic, E., Victor, V., Nathan, R. J., & Loganathan, S. (2021). Procedural Justice, Perceived Organisational Support, and Organisational Citizenship Behaviour in Business School. Organizacija, 54(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.2478/orga-2021-0013

Eisenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S., & Lynch, P. (1997). Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5), 812–820. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.5.812

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived Organizational Support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

Fisk, R. P., Brown, S. W., & Bitner, M. J. (1993). Tracking the evolution of the services marketing literature. Journal of Retailing, 69(1), 61–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(05)80004-1

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

Gokmenoglu, K. K., & Amir, A. (2021). The impact of perceived fairness and trustworthiness on customer trust within the banking sector. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 20(3), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332667.2020.1802642

Groth, M. (2005). Customers as Good Soldiers: Examining Citizenship Behaviors in Internet Service Deliveries: Journal of Management, 31(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206304271375

Groth, M., & Gilliland, S. W. (2001). The role of procedural justice in the delivery of services. Journal of Quality Management, 6(1), 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1084-8568(01)00030-X

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective (7th ed.). Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11747-014-0403-8/FIGURES/8

Herda, D. N., & Lavelle, J. J. (2011). The effects of organizational fairness and commitment on the extent of benefits big four alumni provide their former firm. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 36(3), 156–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2011.02.005

Hui, Z., & Wenan, H. (2022). Egoism or Altruism? The Influence of Cause-Related Marketing on Customers’ Extra-Role Behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.799336

Im, J., & Qu, H. (2017). Drivers and resources of customer co-creation: A scenario-based case in the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 64, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.03.007

Keh, H. T., & Wei Teo, C. (2001). Retail customers as partial employees in service provision: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 29(8), 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550110396944

Kim, M. S., Shin, D. J., & Koo, D. W. (2018). The influence of perceived service fairness on brand trust, brand experience and brand citizenship behavior. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(7), 2603–2621. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2017-0355

La, S., & Choi, B. (2019). Perceived justice and CSR after service recovery. Journal of Services Marketing, 33(2), 206–219. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-10-2017-0342

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What Should Be Done with Equity Theory? In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social Exchange: Advances in Theory and Research (pp. 27–55). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-3087-5_2

Liao, J., Wang, W., Du, P., & Filieri, R. (2023). Impact of brand community supportive climates on consumer-to-consumer helping behavior. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 17(3), 434–452. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-03-2022-0069

Lim, B. T. H., & Loosemore, M. (2017). The effect of inter-organizational justice perceptions on organizational citizenship behaviors in construction projects. International Journal of Project Management, 35(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.10.016

Loi, R., Hang-yue, N., & Foley, S. (2006). Linking employees’ justice perceptions to organizational commitment and intention to leave: The mediating role of perceived organizational support. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79, 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X39657

Masterson, S. S. (2001). A trickle-down model of organizational justice: Relating employees’ and customers’ perceptions of and reactions to fairness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4), 594–604. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.4.594

Masterson, S. S., Lewis, K., Goldman, B. M., & Taylor, M. S. (2000). Integrating justice and social exchange: The differing effects of fair procedures and treatment on work relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 738–748. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556364

Maxham, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002). Modeling customer perceptions of complaint handling over time: the effects of perceived justice on satisfaction and intent. Journal of Retailing, 78(4), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(02)00100-8

Mills, P. K., & Morris, J. H. (1986). Clients as “Partial” Employees of Service Organizations: Role Development in Client Participation. The Academy of Management Review, 11(4), 726–735. https://doi.org/10.2307/258392

Moorman, R. H., Blakely, G. L., & Niehoff, B. P. (1998). Does perceived organizational support mediate the relationship between procedural justice and organizational citizenship behavior? Academy of Management Journal, 41(3), 351–357. https://doi.org/10.2307/256913

Namkung, Y., & Jang, S. C. (Shawn). (2010). Effects of perceived service fairness on emotions, and behavioral intentions in restaurants. European Journal of Marketing, 44(9/10), 1233–1259. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561011062826

Nguyen, H., Groth, M., Walsh, G., & Hennig-Thurau, T. (2014). The Impact of Service Scripts on Customer Citizenship Behavior and the Moderating Role of Employee Customer Orientation. Psychology &Marketing, 31(12), 1096–1109. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20756

Nguyen, P. D., & Tran, L. T. T. (2022). On the relationship between procedural justice and organizational citizenship behavior: a test of mediation and moderation effects. Evidence-Based HRM, 10(4), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-05-2021-0107

Nikbin, D., Marimuthu, M., & Hyun, S. S. (2016). Influence of perceived service fairness on relationship quality and switching intention: an empirical study of restaurant experiences. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(10), 1005–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.801407

Ning, Y. M., & Hu, C. (2022). Influence Mechanism of Social Support of Online Travel Platform on Customer Citizenship Behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(April). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.842138

Noruzy, A., Shatery, K., Rezazadeh, A., & Hatami-Shirkouhi, L. (2011). Investigation the relationship between organizational justice, and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of perceived organizational support. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 4(7), 842–847. https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2011/v4i7/30123

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ortiz, J., Chiu, T.-S., Wen-Hai, C., & Hsu, C.-W. (2017). Perceived justice, emotions, and behavioral intentions in the Taiwanese food and beverage industry. International Journal of Conflict Management, 28(4), 437–463. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-10-2016-0084

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Rahman, M. H. A., & Karim, D. N. (2022). Organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: the mediating role of work engagement. Heliyon, 8(5), e09450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09450

Ramdeo, S., & Singh, R. (2019). Abusive supervision, co-worker abuse and work outcomes: procedural justice as a mediator. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-09-2018-0060

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

Rosenbaum, M. S., & Massiah, C. A. (2007). When Customers Receive Support From Other Customers: Exploring the Influence of Intercustomer Social Support on Customer Voluntary Performance. Journal of Service Research, 9(3), 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670506295851

Schneider, B. (1990). The climate for service: An application of the climate construct. Organizational Climate and Culture, 1, 383–412.

Seth, M., Sethi, D., Yadav, L. K., & Malik, N. (2022). Is ethical leadership accentuated by perceived justice?: Communicating its relationship with organizational citizenship behavior and turnover intention. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 27(4), 705–723. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-09-2021-0095

Shore, L. M. M. F., & Wayne, S. J. (1993). Commitment and employee behavior: Comparison of affective commitment and continuance commitment with perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(5), 774–780. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.5.774

Shore, L. M., & Shore, T. H. (1995). Perceived organizational support and organizational justice. Organizational Politics, Justice, and Support: Managing the Social Climate of the Workplace, 149, 164.

Shumaker, S. A., & Brownell, A. (1984). Toward a Theory of Social Support: Closing Conceptual Gaps. Journal of Social Issues, 40(4), 11–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1984.tb01105.x

Singh, J., & Crisafulli, B. (2016). Managing online service recovery: procedures, justice and customer satisfaction. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 26(6), 764–787. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-01-2015-0013

Song, J. H., Kang, I. G., Shin, Y. H., & Kim, H. K. (2012). The Impact of an Organization’s Procedural Justice and Transformational Leadership on Employees’ Citizenship Behaviors in the Korean Business Context. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 19(4), 424–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051812446659

Su, L., Sam, S., & Nejati, M. (2019). Perceived justice, community support, community identity and residents ’ quality of life: Testing an integrative model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 41(January), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.08.004

Tansky, J. W. (1993). Justice and organizational citizenship behavior: What is the relationship? Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 6(3), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01419444

Tax, S. S., Brown, S. W., & Chandrashekaran, M. (1998). Customer Evaluations of Service Complaint Experiences: Implications for Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299806200205

Thompson, S. A., Kim, M., & Smith, K. M. (2016). Community Participation and Consumer-to-Consumer Helping: Does Participation in Third Party–Hosted Communities Reduce One’s Likelihood of Helping? Journal of Marketing Research, 53(2), 280–295. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.13.0301

Thompson, S. K. (2012). Sampling. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118162934

Tonder, E. Van, & Petzer, D. J. (2022). Factors promoting customer citizenship behaviours and the moderating role of self-monitoring: A study of ride-hailing services. European Business Review, 34(6). https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-09-2021-0197

Van Dijke, M., De Cremer, D., Mayer, D. M., & Van Quaquebeke, N. (2012). When does procedural fairness promote organizational citizenship behavior? Integrating empowering leadership types in relational justice models. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 117(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.10.006

Voorhees, C. M., & Brady, M. K. (2005). A Service Perspective on the Drivers of Complaint Intentions. Journal of Service Research, 8(2), 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670505279702

Yi, Y., & Gong, T. (2006). The antecedents and consequences of service customer citizenship and badness behavior. Seoul Journal of Business, 12(2), 145–176.

Yi, Y., & Gong, T. (2008). The effects of customer justice perception and affect on customer citizenship behavior and customer dysfunctional behavior. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(7), 767–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.01.005

Yi, Y., & Gong, T. (2009). An integrated model of customer social exchange relationship: the moderating role of customer experience. The Service Industries Journal, 29(11), 1513–1528. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060902793474

Yi, Y., & Gong, T. (2013). Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research, 66(9), 1279–1284. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2012.02.026

Zhu, D. H., Sun, H., & Chang, Y. P. (2016). Effect of social support on customer satisfaction and citizenship behavior in online brand communities: The moderating role of support source. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 31, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.04.013

Zhu, T., Liu, B., Song, M., & Wu, J. (2021). Effects of Service Recovery Expectation and Recovery Justice on Customer Citizenship Behavior in the E-Retailing Context. 12(May), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.658153

Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P., Suárez-Acosta, M. A., & Guerra-Báez, R. M. (2015). Customer citizenship as a reaction to hotel’s fair treatment of staff: Service satisfaction as a mediator. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(2), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415613394