Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2023, vol. 14, no. 2(28), pp. 286–303 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2023.14.93

The Role of Health-Consciousness and De-stress Motivation on Travel Desire and Intention

Rasuole Andruliene (corresponding author)

Vilnius University, Lithuania

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6664-3314

rasuole.andruliene@evaf.vu.lt

Sigitas Urbonavicius

Vilnius University, Lithuania

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4176-2573

sigitas.urbonavicius@evaf.vu.lt

Abstract. Health-consciousness is an important reason for travelling to resorts that offer health and wellness services. Additionally, during stressful periods, health-consciousness may trigger de-stress motivation, which is another reason to travel to destinations that help exiting from the stressful conditions. The post-pandemic context presents a situation in which health-consciousness, together with de-stress motivation, could play an important role for travelling to nearby resorts, the services of which together with opportunities to socialize could be seen as desired objectives. However, evidence on the impact of de-stress motivation on desire and intention to travel in post-restriction period is scarce, presenting a notable research gap. This gap is addressed with modelling on the basis of goal-directed behaviour that predicts travelling with the consideration of travel desire and travel intentions. This study concentrates on the impact of health-consciousness and de-stress motivation on desire and intention to travel, with the analysis of data collected from 793 respondents in Lithuania. It was found that health-consciousness and de-stress motivation are positively related to each other and have a significant impact on both travel desire and intention.

Keywords: de-stress motivation, health-consciousness, travel desire, travel intention

Received: 24/11/2022. Accepted: 6/4/2023

Copyright © 2023 Rasuole Andruliene, Sigitas Urbonavicius. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The world has experienced a difficult period during the pandemic, which has caused a lot of stress to people in many countries (Roy et al., 2020; Cusinato et al., 2020). This adds to already high levels of stress in the workplace and a hectic pace of life in general, generating a desire to find more healthy options for living (Lim et al., 2016). As a result, people have been seeking ways to relax and return to at least a pre-pandemic state of living. One method for achieving this is to travel to nearby resorts, since the short distance of travel helps them to avoid notable difficulties of the travelling itself, and the destination offers the relaxing and socializing atmosphere at these locations (Kim et al., 2021; Yousaf, 2021; Dar & Kashyap, 2022). This is particularly important for people who are health-conscious and therefore pay a lot of attention to keeping themselves healthy (Azman & Chan, 2010; Voight et al., 2011; Choi et al., 2015; Dryglas & Salamaga, 2018).

The impact of health-consciousness as a personal trait on the intention to travel to health and wellness destinations and on the intention to use relaxation services has been analysed in numerous studies; however, they generally did not consider the factor of desire (Widmar et al., 2016; Park et al., 2017; Pu et al., 2021; Anannukul & Yoopetch, 2022). Typically, the relationship between human characteristics and intentions has been assessed on the basis of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) and in several other ways (Zhang et al., 2021; Park et al., 2017). Much less is known on this relationship when not only intention but also desire is considered. Desire is a more emotionally coloured motivational factor that is not subject to the limitation of financial or time resources needed for a specific trip and is used in the model of goal-directed behaviour (MGB) (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2001). While desires are expected to be typically highly correlated with intentions, they are nonetheless different; intentions take into account facilitating and inhibiting factors, while desires do not (Prestwich et al., 2008). As suggested by Gursoy et al. (2022), travel desire is different from travel intention because desire is a feeling, while intention is a more concrete idea that individuals plan to carry out in the future. The MGB also provides a good grounding of the relationship between desire and intention, but the impact of health-consciousness on desire and, consequently, to the intention to travel to health destinations presents a notable research gap.

An even larger research gap is seen with regard to such relationships when stress pressure is considered. It seems logical that health-conscious people notice this pressure on their health and are willing to resolve any unfortunate resulting situation (Huang et al., 2019). However, it is largely unknown whether de-stress motivation impacts on desire and willingness to travel to resorts offering health and wellness services.

This study aims to reduce the research gaps in how health-consciousness and de-stress motivation together impact people’s desire and intention to travel to nearby resorts. The study deals with de-stress motivation for travelling in after-pandemic conditions, when the major stress is accumulated during the period of rigid restrictions to travel, to meet with other people and more. Therefore, the context (momentum) of this study itself presents an additional substantial scientific novelty, since the situation of going out of a similar period of restrictions is rather rear. The modelling is based on the model of goal-directed behaviour proposed by Perugini and Bagozzi (2001) – a concept the grounds the relationship between motivation, desire and intention. The study considers travel to relatively close destinations within the same country, as longer and more complicated trips themselves generate additional elements of stress (DeFrank et al., 2000; Waterhouse et al., 2004).

1. Literature Review

1.1 Motivation Factors in Tourism

Motivation to do something occurs as the reflection of a set of individual needs (Suddendorf, 2000; Maslow, 2000; Chang, 2007). The needs and desires of travellers can therefore be considered important psychological determinants of travel behaviour (You et al., 2000; Uysal et al., 2008). Tourist motivations depend on numerous personality factors (Plog, 2001; Kurtzman & Zauhar, 2005) and may change over time, depending on the external situation (Iso-Ahola & Clair, 2000; Harrill & Potts, 2002) and whether motivations are closely linked to external factors, such as the characteristics of specific destinations (Kozak, 2002; Yoo et al., 2018; Rita et al., 2019; Carvache-Franco et al., 2021). Internal motivations originate from the intangible intrinsic desires of individual travellers and may sometimes be summarised into an integrative motivational factor of the desire to travel (He & Luo, 2020). However, internal motivations (“push motivations”) are more frequently segregated and analysed as specific motivations for escape, rest and relaxation, health and fitness, adventure, prestige, and social interaction (Crompton, 1979). The specific motivations for travelling deserve continuous attention of researchers, and their list varies depending on the aim of a specific study. This is fully understandable, however, the analysis of travel motivations includes a more important issue: many types of motivations are not substantially grounded from the theoretical point of view and are measured with the help of a wide variety of scales, which makes cross-study comparisons and generalizations rather difficult (Lin et al., 2021). This is also applicable to the assessments of de-stress motivation that is one of the key elements in this study. De-stress motivation has similarities with escape motivation, relaxation motivation and more (Azman et al., 2010; Baloglu, 2019; Panda & Pandey, 2017; Težak Damijanić & Luk, 2017; Carvache-Franco et al., 2022). Though it is obvious that researchers segregate these motivations, since they have been assessed in the same studies as separate factors that have been measured with different scales, more precise conceptualisation of de-stress motivation is important for the purpose of this study.

The concept of de-stress roots from the very core understanding of stress, which is typically defined as a mental state of worry or mental tension caused by an unfavourable situation (Lecic-Tosevski et al., 2011; Choudhury, 2017; Panigrahi, 2016; Rana et al., 2019). The important element of the concept is acknowledgement of the existence of a long-lasting set of factors that is responsible for the occurrence of this mental state. Even if these factors are eventually disappearing, the mental state that is defined as a stress may remain (Troy & Mauss, 2011; Braquehais et al., 2020). This triggers a person to look for options to reduce the level of the stress (often accumulated during a significant period of time), which is formulated as de-stress motivation in the current study. This makes the de-stress motivation different from the escape motivation that is often analysed in travelling studies: de-stress motivation addresses the effort to cope with the unfavourable mental state (Carvache-Franco et al., 2022), while escape motivation mainly focuses on the exiting from the current situation that is abundant of unfavourable external factors (Fisher & Price, 1991; Jeong, 2015). However, both these motivations might address similar solutions or targets: for instance, people driven by both motivations could seek relaxation of any form that is appropriate for them individually. Therefore, if a study is more concentrated on the “pull” type motivations, de-stress and escape motivations may be omitted or replaced by general motivation for relaxation or motivations of more concrete forms of relaxation (Whiting et al., 2017; Težak Damijanić & Luk, 2017; Carvache-Franco et al., 2022; Sørensen & Høgh-Olesen, 2023). Since this study addresses the period when many people remain under the effect of the long-lasting stressful period of the Covid pandemic, this makes the de-stress motivation particularly important and requires a study of its effects outside of other travel motivations.

Travel motivation has always been considered an essential part of the process of tourist behaviour (Li & Cai, 2012). Such behaviour is typically predicted by behavioural intention, which is influenced by different types of travel motivation (Yoon & Uysal, 2005; Sparks, 2007). These relationships have been extensively analysed on various theoretical grounds (Baloglu, 2000; Lam & Hsu, 2006; Jang et al., 2009; Hsu & Huang, 2010; Li & Cai, 2012). As behavioural intentions and actual travel behaviours are integral parts of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), Hsu and Huang (2010) sought to integrate travel motivation factors into the TPB model. Their proposed model brought in the motivation component with four motivational factors and provided an alternative way to enable a deeper understanding of the impact of motivation on the process for formation of travel behaviour (Li & Cai, 2012).

A review of tourism literature suggests that studies on the relationship between motivation and travel intention are not numerous and include conflicting findings (Huang & Hsu, 2009; Li & Cai, 2012). In summarising them, Dean and Suhartanto (2019) concluded that the relationships between tourist motivations and behavioural intention have not been well-analysed and present a notable research gap in tourism studies.

One possible route to addressing this gap is to employ the model of goal-directed behaviour (MGB), which provides additional predictive power by adding the motivational component of desire (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2001). This not only helps in assessing the direct impact of motivations on intention, but also considers the mediating factor of desire, which is more general by nature than intention and less subject to characteristics of a trip such as costs and timing (Lee et al., 2020).

1.2 Desire and Intention

Perugini and Bagozzi (2001) proposed the model of goal-directed behaviour as an extension of the theory of planned behaviour to circumvent issues that may limit a fuller understanding of human behaviours through the lens of goal-setting and motivation. The main additional element is the factor of desire, which is understood as a complex integral element that includes the effects of numerous more specific motivations. It has been stated that desire reflects the general activation of a motivational force that “provides the direct impetus for intentions” (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2001, p. 80), while desire is defined as “a state of mind whereby an agent has a personal motivation to perform an action or to achieve a goal” (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2004, p. 71). Ko (2020) notes that desire is part of an individual’s internal motivation.

The importance of desire in decision formation is indicated by literature showing that desire strongly influences intention (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2004). Desire integrates the effects of emotional, cognitive, self-perception and social appraisals on decision-making, and then leads to an intention to act (Hunter, 2006; Han et al., 2014). Perugini and Bagozzi (2001) suggested that the stronger the motivational component embedded in desire, the more likely it is that desire will predict a person’s behavioural intention.

Several studies have confirmed that desire is an important factor for predicting intention (Song et al., 2012; Song et al., 2016), with some reaching an even stronger conclusion that the role of desire is pivotal in the decision-making process (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2004). In general, recognition of its importance in this is found in many studies (Hunter, 2006; Han & Kim, 2010; Lee et al., 2012; Han et al., 2014; Song et al., 2016).

Though desire seems somewhat similar to intention, the concept of desire – typically referred to as a wish – is explicitly distinguished from intention in literature on goals (Perugini & Bagozzi, 2004). Intention represents a self-commitment to performing a behaviour, but a person who lacks desire will not formulate a self-commitment to act (Hunter, 2006). Desire comprises solely what the individual wants to make happen, while intentions incorporate behavioural influences and commitment to action. Hence, facilitating and inhibiting factors are built into intentions but not desires (Han et al., 2014).

As there is evidence from tourism studies that desire has a positive effect on behavioural intention (Song et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021), we developed the following hypothesis as a starting point for further analysis:

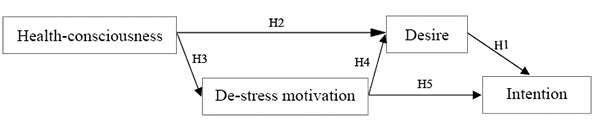

H1: Desire to travel positively impacts the intention to travel.

1.3 Health-Consciousness

Health-consciousness is a factor that reflects the degree to which someone attends to or focuses on their health – referring to an inner state of self-attention to self-relevant cues (Wang et al., 2019). In other words, health-consciousness reflects a perceived tendency to pay attention to one’s health (Xu et al., 2020). It is an indicator of a consumer’s intrinsic motivation to maintain good health and a reflection of his or her responsibility towards health. It therefore influences the individual’s health-preventive and health-maintenance behaviours (Dutta-Bergman, 2004; Michaelidou & Hassan, 2008; Karn & Swain, 2017; Ahadzadeh et al., 2019; Čvirik, 2020). People who are conscious about personal health are more motivated to take action to improve their health (Pu et al., 2021).

In tourism research, health motivation can be seen in a position between personal values and lifestyle (Chen et al., 2008). Chen (2013) made a parallel between an individual’s health-consciousness and their orientation towards a wellness lifestyle. Health-tourism behaviour is heavily grounded in health-consciousness as a key motivator of intention to travel to wellness resorts (Pu et al., 2021). Destinations with natural resources and health-promoting activities encourage tourists’ willingness and propensity to travel (Cheng et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). However, the relationship between health-consciousness and desire to travel remains largely unknown, with some studies reporting their relationship as being insignificant (Zhang et al., 2021). To examine this, we developed the hypothesis:

H2: Health-consciousness positively impacts desire to travel.

1.4 De-stress Motivation

The stress that has been accumulated during the long period of Covid forces people to look for options of going out of this unpleasant mental state. Since at least part of the mental tension has been created by requirements of staying at home together with restrictions of meeting with larger groups of people, the natural release from this situation could be associated with finally removed restrictions and possibilities to travel outside the domestic locations and to meet with broader groups of people. However, the perception of how much damaging the stress is largely depends on the personal health-consciousness (Martínez et al., 2021; Yun & Kim, 2022).

According to Pu et al. (2021), health-consciousness is linked to many factors that are linked to one’s health. Chen et al. (2008) found a significant relationship between health-consciousness and the benefits that people experience to personal health by using wellness services. In the mind of wellness customers, the pursuit of psychological benefits is the most important driving force that draws them to resorts (Chen et al., 2008). Health-related value attributes are particularly attractive for tourists whose goal is a healthier lifestyle that could improve their mental and physical well-being (Kerstetter et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2021). In other words, health-conscious individuals are better at noticing their mental discomfort (for instance, their level of stress) and then tend to behave in the direction of removing the unfavourable status – thus enhancing their travel motivation (Huang et al., 2019). Based on this, we proposed the hypothesis:

H3: Health-consciousness positively impacts de-stress motivation.

Studies in tourism also show that travel motivation is related to the wish to recover from the stress and tension of everyday life, relax mentally and physically, find peace and tranquillity (Aguirre et al., 2021). Travel is often regarded as an effective way to reduce the stress by enabling people to relax physically and emotionally (Chen et al., 2016; Io, 2021). Stress reduction, which is a common motivation for many tourists, has been identified as a primary cause and benefit in wellness studies (Kelly, 2012; Chen et al., 2013; Chen & Petrick, 2013; Hudson et al., 2017; Baloglu et al., 2019). Considering the specificities of resorts, Chien et al. (2012) showed the impact of travel motivation on intention to choose a beach-based resort. According to Chen et al. (2016), spending time in resorts can help individuals to recover from stress, and improve their health and psychological well-being. However, a statistically confirmed presence for the direct impacts of de-stress motivation on desire and intention remains unclear. To examine this, the following hypotheses were therefore developed:

H4: De-stress motivation positively impacts on desire to travel.

H5: De-stress motivation positively impacts on intention to travel.

2. Method

2.1 Model and Measures

The modelling in the study is based on the model of goal-directed behaviour, which links motivations with desire and intention. The essence of the model is based on the assessment of direct relationships between de-stress motivation and desire, and de-stress motivation and intention. However, this is also affected by health-consciousness, which is assumed to impact on desire to travel to resorts. Furthermore, it is predicted that an increase in health-consciousness increases de-stress motivation, a relationship that is a rather novel prediction in travel research. Altogether, the model presents a consistent sequence of impacts from health motivation towards intention to travel to resorts (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Research Model

Data was collected using a questionnaire including scales that have been successfully employed in earlier studies. It started with questions that measured health-consciousness, with the seven-item scale adopted from Zhang et al. (2021). De-stress motivation was then assessed with the help of a four-item scale used by Baloglu et al. (2019). Desire was measured using a four-item scale and intention with a five-item scale (both from Zhang et al., 2021), but items were minimally modified to ask about resorts rather than rural eco-sites, as in the original study. The preamble to the questions specified that we should ask about desire and intention to visit well-known local resorts. To avoid impacts that could occur from the specificities of particular resorts, half the respondents were asked about a resort by the sea and the other half about one away from the sea.

2.2 Procedure and Data

Data was collected through a representative survey in Lithuania by a research agency from March to April 2022. The survey included 793 respondents, of which 396 answered about seaside resorts and 397 about other resorts. The distribution of questionnaires with reference to particular resorts was random. As expected, this resulted in almost the same distribution of respondents in both groups according to all demographic parameters used, with no significant differences found. When the means of each measured factor were then compared between the two groups, no significant differences on the basis of resort type were observed with regard to any factor. This allowed us to conclude that the type of resort has no notable impact on the measured variables and to carry out further analysis without consideration of the resort type. All further analysis was therefore performed on data from the 793 questionnaires with the help of SPSS 28 and AMOS 28 software.

Respondents who participated in the study represented four age groups: those aged 16–30 (25.6%), 31–45 (26.3%), 46–60 (30.8%) and over 60 (17.3%). In the sample, 47.0% of respondents were male, while 53.0% were female, and 51.2% had university education. There were no significant differences in the means of assessed variables based on demographic parameters, meaning the sample was suitable for analysis without using demographic control variables.

In the process of confirmatory factor analysis, two items were removed from the scale of health-consciousness and one from the scale of desire. After that, the fit of the model was acceptable (CMIN/DF=3.390; TLI=0.971; CFI=0.976; RMSEA=0.055; PCLOSE=0.077 (according to Byrne, 2010)). The reliability and validity of the scales obtained was assessed by measuring composite reliability, which was above the required 0.70 (Bagozzi & Yi, 2012). As recommended by Fornell and Larcker (1981), the standardised factor loadings and the average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded 0.50, while the squared AVE values for each construct were greater than the correlation values of that construct (Table 1).

Table 1

Validity and Reliability of Scales

|

|

CR |

AVE |

Desire |

De-stress |

Intention |

Health- |

|

Desire |

0.942 |

0.844 |

0.919 |

|

|

|

|

De-stress motivation |

0.920 |

0.700 |

0.332 |

0.837 |

|

|

|

Intention |

0.959 |

0.825 |

0.613 |

0.301 |

0.908 |

|

|

Health-consciousness |

0.852 |

0.538 |

0.440 |

0.216 |

0.249 |

0.733 |

Note. CR – composite reliability; AVE – average variance extracted.

This level of reliability and validity of the measured variables was suitable for testing the hypotheses.

2.3 Findings

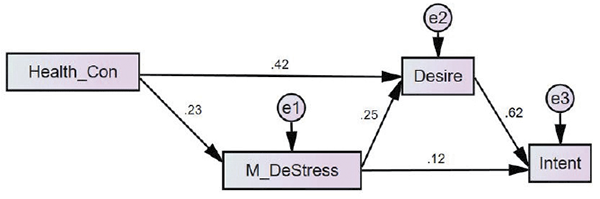

The hypotheses were tested using SEM modelling. The fit of the structural model (CMIN/DF=1.853; TLI=0. 990; CFI=0.998; RMSEA=0.023; PCLOSE=0.926) was satisfactory and allowed progression with further analysis. For the tests of the hypotheses, standardised regression weights were assessed in the structural model (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Structural Model

All direct relationships tested were significant at the p≤0.001 level, allowing the confirmation of all hypotheses (Table 2).

Table 2

Standardised Regression Weights

|

Hypothesis |

Relationship |

Estimate |

P |

Result |

||

|

H1 |

Intention |

← |

Desire |

0.624 |

p≤0.001 |

Accepted |

|

H2 |

Desire |

← |

Health-consciousness |

0.421 |

p≤0.001 |

Accepted |

|

H3 |

De-stress |

← |

Health-consciousness |

0.235 |

p≤0.001 |

Accepted |

|

H4 |

Desire |

← |

De-stress motivation |

0.249 |

p≤0.001 |

Accepted |

|

H5 |

Intention |

← |

De-stress motivation |

0.125 |

p≤0.001 |

Accepted |

The findings show that desire is a very strong predictor of intentions, as expected (β=0.624), and that health-consciousness strongly predicts desire to travel to resorts (β=0.421). There is important evidence on the significant positive impact of health-consciousness on de-stress motivation (β=0.249), empirically confirming the link between these two factors. Similarly, de-stress motivation appeared to be an important predictor of desire to travel to resorts (β=0.249). The direct impact of de-stress motivation on intention was also significant, but weaker (β=0.125).

3. Discussion and Conclusions

The initial element tested in the model was the presence of a positive impact of desire on intention to travel. Although this relationship is strongly theoretically grounded, empirical evidence on the basis of the data used was an essential prerequisite that would allow all other relationships to be tested. The findings confirm the presence of a positive relationship between desire and intention, and are therefore in line with the results of former studies that have reported the presence of this relationship (Song et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). This is also in line with conceptual elaboration by Perugini and Bagozzi (2001) that suggested including desire even in studies that use the classical model of the theory of planned behaviour (Shaw et al., 2007; Kovač & Rise, 2011).

Health-consciousness, as a personality trait, plays an important role not just in routine daily behaviours, but also in people’s leisure and holiday time and in travel (Novelli et al., 2006; Urh, 2015).

However, there are not many studies that have examined the relationship between health-consciousness and desire to travel, while the findings of other studies have not always reported the significance of the impact of health-consciousness on desire (Zhang et al., 2021). The findings in this study strongly confirmed the presence and significance of this impact. It is, however, necessary to mention the specific context of this study. First, it was performed after the major waves of the Covid pandemic, when the population’s sensitivity to health issues was higher than usual. Second, the analysed destinations (resorts) were directly linked to health-related aspects of travel and leisure activities. As expected, findings supported the notion of Chen et al. (2008) about health-consciousness being important for travellers going to resorts for wellness services. Nevertheless, the empirical evidence in the current study confirms the strong impact of health-consciousness on desire to travel, justifying the conclusion that health-consciousness is an important predictor of the desire to travel.

Even more importantly, the study has given insight into the strength of the link between health-consciousness and de-stress motivation. This has been assumed indirectly by Chen et al. (2008), but the current study presents clear empirical evidence of the significance of this relationship. Again, the importance of de-stress motivation might have been impacted by the long-lasting stressful period of the Covid pandemic. However, we believe this finding may be generalized, since stress can be generated by many other individual or societal factors at work and at home (Iso-Ahola & Mannell, 2004; Mannell, 2007; Karimi & Brazier, 2016).

The role of de-stress motivation in travel research has not been widely analysed in the past, presenting a notable research gap. More specifically, gaps existed in terms of its impact on travel desire and travel intention, with both these relationships remaining largely unknown and studied only indirectly (Chen & Petrick, 2013; Hudson et al., 2017; Baloglu et al., 2019). The findings of the current study allow two more conclusions to be made with regard to this. First, de-stress motivation is an important predictor of the desire to travel to wellness resorts and has a positive direct impact on it; and second, de-stress motivation directly impacts on intention to travel, at least when resorts are considered as destinations. This allows an additional conclusion to be drawn on the mechanism for how de-stress motivation impacts on intention to travel: it happens both directly and indirectly, with mediation of desire.

4. Managerial Implications

Health and wellness tourism involves tourist facilities (e.g., hotels) or destinations (e.g., health resorts) that seek to attract tourists by promoting their health and well-being services and facilities, in addition to their regular tourist amenities. After the COVID-19 crisis, people who have suffered from mental anguish in their homes need a place to relax, unwind, and de-stress. De-stress motivation becomes an important driver to visit resorts, especially for a health-conscious traveller. Therefore, the main managerial implication includes the suggestion to consider this in planning the corresponding marketing strategies for resorts. Specific emphasis in them should be paid not only to the de-stress linked services themselves, but also to communicating the whole atmosphere in the destinations that contrasts with the stressful conditions during the pandemics. In the post-COVID-19 period, it is not enough just to target health-conscious population; the direct addressing to de-stress motivation needs to be specifically outlined in the advertising appeal.

It is important to note that this type of a strategy could be used not just by resorts that offer services that include medical treatment for various diseases. The concept of de-stressing is much broader, therefore it might be explored by resorts that are not directly specialising in medical services. The stress reduction-related services at a resort or hotel could improve tourists’ mental and physical well-being with numerous related services, such as weight loss programmes, massages, meditation, yoga, acupuncture, breathing exercises, herbal remedies, and outdoor experiences. Even more – even convenient opportunities of socialization and group activities may serve as important relievers from stress.

5. Limitations and Further Research

The study has several limitations that outline potential directions for future studies.

First, this study assessed de-stress motivation after a two-year-long pandemic period and at a time when a military conflict started in a nearby country. These types of factors undoubtedly generate high levels of stress, triggering a strong motivation to reduce it. This might be less marked during less–stressful periods, though various reasons for stress are always present. Nevertheless, these factors would not be the same at other places and times, so there is a need to assess whether de-stress motivation has the same relationships with health-consciousness, desire and intention in these different instances.

Second, this study has concentrated on a specific type of destination: resorts at which health and wellness services are widely offered. However, other types of travel activity and destinations can be pursued and considered in order to escape from stress – such as travel to locations for nature exploration and involvement in active physical or mental pursuits during trips. Again, these are possible directions for further research on the importance of de-stress motivation in travel.

Finally, there may be cultural or generational specificities with regard to leisure and travel, with differing perceptions about personal health and stress. It would be advisable to consider a cross-cultural study to ensure the consistency of the current findings.

References

Ahadzadeh, A. S., Pahlevan Sharif, S., & Sim Ong, F. (2018). Online health information seeking among women: the moderating role of health consciousness. Online Information Review, 42(1), 58–72.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Anannukul, N., & Yoopetch, C. (2022). The determinants of intention to visit wellness tourism destination of young tourists. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 43(2), 417–424.

Azman, I., & Chan, J. K. L. (2010, September). Health and Spa Tourism Business: Tourists’ Profiles and Motivational Factors. In Health, Wellness and Tourism: Healthy Tourists, Healthy Business? Proceedings of the Travel and Tourism Research Association Europe 2010, Budapest, 9–24.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, Evaluation, and Interpretation of Structural Equation Models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34.

Baloglu, S. (2000). A Path Analytic Model of Visitation Intention Involving Information Sources, Socio-Psychological Motivations, and Destination Image. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 8(3), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v08n03_05

Baloglu, S., Busser, J., & Cain, L. (2019). Impact of experience on emotional well-being and loyalty. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(4), 427–445.

Braquehais, M. D., Vargas-Cáceres, S., Gómez-Durán, E., Nieva, G., Valero, S., Casas, M., & Bruguera, E. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(9), 613–617.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Carvache-Franco, M., Carvache-Franco, W., Víquez-Paniagua, A. G., Carvache-Franco, O., & Pérez-Orozco, A. (2021). The Role of Motivations in the Segmentation of Ecotourism Destinations: A Study from Costa Rica. Sustainability, 13(17), 9818.

Carvache-Franco, M., Contreras-Moscol, D., Orden-Mejía, M., Carvache-Franco, W., Vera-Holguin, H., & Carvache-Franco, O. (2022). Motivations and Loyalty of the Demand for Adventure Tourism as Sustainable Travel. Sustainability, 14(14), 8472.

Chang, J. C. (2007). Travel motivations of package tour travelers. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 55(2), 157–176.

Chen, C. C., & Petrick, J. F. (2013). Health and Wellness Benefits of Travel Experiences: A Literature Review. Journal of Travel Research, 52(6), 709–719.

Chen, C. C., Petrik, J. F., & Shahvali, M. (2016). Tourism Experiences as a Stress Reliever: Examining the Effects of Tourism Recovery Experiences on Life Satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 55(2), 150–160.

Chen, J. S., Prebensen, N., & Huan, T. C. (2008). Determining the Motivation of Wellness Travelers. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 19(1), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2008.9687056

Chen, K. H., Liu, H. H., & Chang, F. H. (2013). Essential customer service factors and the segmentation of older visitors within wellness tourism based on hot springs hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 122–132.

Chen, M. F. (2013). Influences of health consciousness on consumers’ modern health worries and willingness to use functional foods. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(1), 1–12.

Cheng, M., Wong, I. A., Wearing, S., & McDonald, M. (2017). Ecotourism social media initiatives in China. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(3), 416–432.

Chien, G. C., Yen, I. Y., & Hoang, P. Q. (2012). Combination of Theory of Planned Behavior and Motivation: An Exploratory Study of Potential Beach-based Resorts in Vietnam. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 17(5), 489–508.

Choi, Y., Kim, J., Lee, C.K., & Hickerson, B. (2015). The Role of Functional and Wellness Values in Visitors’ Evaluation of Spa Experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(3), 263–279.

Choudhury, J. (2017). Building Resilience to De-stress the Stress. ASBM Journal of Management, 10(2), 40–47.

Crompton, J. L. (1979). Motivations for Pleasure Vacation. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 408–424.

Cusinato, M., Iannattone, S., Spoto, A., Poli, M., Moretti, C., Gatta, M., & Misciosca M. (2020). Stress, Resilience, and Well-Being in Italian Children and Their Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 1–17.

Čvirik, M. (2020). Health Conscious Consumer Behaviour: The Impact of a Pandemic on the Case of Slovakia. Central European Business Review, 9(4), 45–58.

Dar, K., & Kashyap, K. (2022). Wellness travel motivations in the wake of COVID-19. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 12(1), 24–43.

Dean, D. L., & Suhartanto, D. (2019). The formation of visitor behavioral intention to creative tourism: the role of push–pull motivation. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 24(5), 1–11.

DeFrank, B., Konopaske, R., & Ivancevich, J. M. (2000). Executive travel stress: Perils of the road warrior. The Academy of Management Executive, 14(2), 58–71.

Dryglas, D., & Salamaga, N. (2018). Segmentation by push motives in health tourism destinations: A case study of Polish spa resorts. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 234–246.

Dutta-Bergman, M. J. (2004). An Alternative Approach to Social Capital: Exploring the Linkage Between Health Consciousness and Community Participation. Health Communication, 16(4), 393–409.

Fisher, R. J., & Price, L. L. (1991). International Pleasure Travel Motivations and Post-Vacation Cultural Attitude Change. Journal of Leisure Research, 23(3), 193–208.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Gursoy, D., Ekinci, Y., Can, A. S., & Murray, J. C. (2022). Effectiveness of message framing in changing COVID-19 vaccination intentions: Moderating role of travel desire. Tourism Management, 90, 104468.

Han, H., & Kim, Y. (2010). An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29(4), 659–668.

Han, H., Baek, H., Lee, K., & Huh, B. (2014). Perceived Benefits, Attitude, Image, Desire, and Intention in Virtual Golf Leisure. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 23(5), 465–486.

Harrill, R., & Potts, T. D. (2002). Social Psychological Theories of Tourist Motivation: Exploration, Debate, and Transition. Tourism Analysis, 7(2), 105–114.

He, X., & Luo, J.M. (2020). Relationship among Travel Motivation, Satisfaction and Revisit Intention of Skiers: A Case Study on the Tourists of Urumqi Silk Road Ski Resort. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 1–13.

Hsu, C. H. C., & Huang, S. (2010). An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior Model for Tourists. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 36(3), 390–417.

Huang, S., & Hsu, C. H. C. (2009). Travel motivation: linking theory to practice. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3(4), 287–295.

Huang, Y. C., Cheng, J. S., & Chang, L. L. (2019). Understanding Leisure Trip Experience and Subjective Well-Being: An Illustration of Creative Travel Experience. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(4), 1161–1182.

Hudson, S., Thal, K., Cárdenas, D., & Meng, F. (2017). Wellness tourism: stress alleviation or indulging healthful habits? International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 11(1), 35–52.

Hunter, G. L. (2006). The role of anticipated emotion, desire, and intention in the relationship between image and shopping center visits. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 34(10), 709–721.

Io, M. U. (2021). The moderating effect of daily emotional well-being on push-pull travel motivations in the context of COVID 19. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–14. DOI:10.1080/02508281.2021.1956218

Ibrahim, A. M., Aguirre, P. M. M., & Lee, E. P. (2021). Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions and Travel Motives: The Case of South Cotabato Province, Philippines. Journal of Tourism Quarterly, 3(4), 260–214.

Iso-Ahola, S. E., & Clair, B. S. (2000). Toward a Theory of Exercise Motivation. Quest, 52(2), 131–147.

Iso-Ahola, S. E., & Mannell, R.C. (2004). Leisure and Health. In J. T. Haworth & A. J. Veal (Eds.), Work and Leisure (pp. 184–199). Routledge.

Jang, S., Bai, B., Hu, C., & Wu, C. M. E. (2009). Affect, Travel Motivation, and Travel Intention: A Senior Market. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 33(1), 51–73.

Jeong, C. (2014). Marine Tourist Motivations Comparing Push and Pull Factors. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 15(3), 294–309.

Karimi, M., & Brazier, J. (2016). Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference? Pharmacoeconomics, 34(7), 645–649.

Karn, S., & Swain, S. K. (2017). Health consciousness through wellness tourism: A new dimension to new age travelers. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 6(3), 1–9.

Kelly, C. (2012). Wellness Tourism: Retreat Visitor Motivations and Experiences. Tourism Recreation Research, 37(3), 205–213.

Kerstetter, D. L., Hou, J. S., & Lin, C.H. (2004). Profiling Taiwanese ecotourists using a behavioral approach. Tourism Management, 25(4), 491–498.

Kim, E. E. K., Seo, K., & Choi, Y. (2021). Compensatory Travel Post COVID-19: Cognitive and Emotional Effects of Risk Perception. Journal of Travel Research, 6(8), 1895–1909.

Kim, J. S., Lee, T. J., & Kim, N. J. (2020). What motivates people to visit an unknown tourist destination? Applying an extended model of goal-directed behavior. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(1), 1–13.

Ko, H. C. (2020). Beyond Browsing: Motivations for Experiential Browsing and Goal-Directed Shopping Intentions on Social Commerce Websites. Journal of Internet Commerce, 19(2), 212–240.

Kovač, V. B., & Rise, J. (2011). The role of desire in the prediction of intention: The case of smoking behavior. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 70(3), 141–148.

Kozak, M. (2002). Comparative analysis of tourist motivations by nationality and destinations. Tourism Management, 23(3), 221–232.

Kurtzman, J., & Zauhar, J. (2005). Sports Tourism Consumer Motivation. Journal of Sport Tourism, 10(1), 21–31.

Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. C. (2006). Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination. Tourism Management, 27(4), 589–599.

Lecic-Tosevski, D., Vukovic, O., & Stepanovic, J. (2011). Stress and Personality. Psychiatriki, 22(4), 290–297.

Lee, C. K., Ahmad, M. S., Petrick, J. F., Park, Y. N., Park, E., & Kang, C. W. (2020). The roles of cultural worldview and authenticity in tourists’ decision-making process in a heritage tourism destination using a model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 1–12.

Lee, C. K., Song, H. J., Bendle, L. J., Kim, M. J., & Han. H. (2012). The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: A model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 33(1), 89–99.

Lee, S. J., Song, H. J., Lee, C. K., & Petrik, J. F. (2018). An Integrated Model of Pop Culture Fans’ Travel Decision-Making Processes. Journal of Travel Research, 57(5), 687–701.

Li, M., & Cai, L. A. (2012). The Effects of Personal Values on Travel Motivation and Behavioral Intention. Journal of Travel Research, 51(4), 473–487.

Lim, Y. J., Kim, H. K., & Lee, T. J. (2016). Visitor Motivational Factors and Level of Satisfaction in Wellness Tourism: Comparison Between First-Time Visitors and Repeat Visitors. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(2), 137–156.

Lin, Z. C., Wong, I. A., Kou, I. E., & Zhen, X. C. (2021). Inducing wellbeing through staycation programs in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 1–12.

Mannell, R. C. (2007). Leisure, Health and Well-Being. World Leisure Journal, 49(3), 114–128.

Martínez, M., Luis, E. O., Oliveros, E. Y., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Sarrionandia, A., Vidaurreta, M., & Bermejo-Martins, E. (2021). Validity and Reliability of the Self-Care Activities Screening Scale (SASS-14) during COVID-19 Lockdown. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 19(1), 1–12.

Maslow, A. H. (2000). A Theory of Human Motivation. Classics in Management Thought-Edward Elgar Publishing, 1, 450.

Michaelidou, N., & Hassan, L. M. (2008). The Role of Health Consciousness, Food Safety Concern and Ethical Identity on Attitudes and Intentions Towards Organic Food. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 32(2), 163–170.

Novelli, M., Birte, S., & Trisha, S. (2006). Networks, Clusters and Innovation in Tourism: A UK Experience. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1141–1152.

Panda, S., & Pandey, S. C. (2017). Binge watching and college students: Motivations and outcomes. Young Consumers, 18(4), 425–438.

Panigrahi, C. M. A. (2016). Managing Stress at Workplace. Journal of Management Research and Analysis, 3(4), 154–160.

Park, J., Ahn, J., & Yoo, W. S. (2017). The Effects of Price and Health Consciousness and Satisfaction on the Medical Tourism Experience. Journal of Healthcare Management, 62(6), 405–417.

Perugini, M., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2001). The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviors: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behavior. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(1), 79–98.

Perugini, M., & Bagozzi, R.P. (2004). The distinction between desires and intentions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34(1), 69–84.

Plog, S. C. (2001). Why Destination Areas Rise and Fall in Popularity: An Update of a Cornell Quarterly Classic. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 42(3), 13–24.

Prestwich, A., Perugini, M., & Hurling, R. (2008). Goal desires moderate intention – behaviour relations. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47(1), 49–71.

Pu, B., Du, F., Zhang, L., & Qiu, Y. (2021). Subjective knowledge and health consciousness influences on health tourism intention after the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective study. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(2), 131–139.

Rana, A., Gulati, R., & Wadhwa, V. (2019). Stress among students: An emerging issue. Integrated Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 44–48.

Rita, P., Brochado, A. & Dimova, L. (2019). Millennials’ travel motivations and desired activities within destinations: A comparative study of the US and the UK. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(16), 2034–2050.

Roy, D., Tripathy, S., Kar, S. K., Sharma, N., Verma, S. K., & Kaushal, V. (2020). Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 1–7.

Shaw, D. S., Shiu, E., Hassan, L. M., Hogg, G., & Bekin, C. (2007). Intending to be Ethical: An Examination of Consumer Choice in Seatshop Avoidance. Advances in Consumer Research, 34, 31–38.

Song, H. J., Lee, C. K., Kang, S. K., & Boo, S. J. (2012). The effect of environmentally friendly perceptions on festival visitors’ decision-making process using an extended model of goal-directed behaviour. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1417–1428.

Song, H., Lee, C. K., Reisinger, Y., & Xu, H. L. (2016). The role of visa exemption in Chinese tourists’ decision-making: A model of goal-directed behavior. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(5), 666–679.

Sørensen, A., & Høgh-Olesen, H. (2023). Walking for well-being. Exploring the phenomenology of modern pilgrimage. Culture & Psychology, 29(1), 27–44.

Sparks, B. (2007). Planning a wine tourism vacation? Factors that help to predict tourist behavioural intentions. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1180–1192.

Suddendorf, T. (2000). The Rise of the Metamind. In M. Corballis & S. E. G. Lea (Eds.), The Descent of Mind: Psychological Perspectives on Hominid Evolution (pp. 218–260). London: Oxford University Press.

Težak Damijanić, A., & Luk, N. (2017). The Relationship Between Travel Motives and Customer Value Among Wellness Tourists. In A. Correia, M. Kozak, J. Gnoth & A. Fyall (Eds.), Co-Creation and Well-Being in Tourism (pp. 19-32). DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-4410C8-5_2

Troy, A. S., & Mauss, I. B. (2011). Resilience in the face of stress: Emotion regulation as a protective factor. In S. M. Southwick, B. T. Litz, D. Charney & M. J. Friedman (Eds.), Resilience and Mental Health: Challenges Across the Lifespan (pp. 30–44).

Urh, B. (2015). Healthy Lifestyle and Tourism. Quaestus: Multidisciplinary Research Journal, 6, 132–143.

Uysal, M., Li, X., & Sirakaya-Turk, E. (2008). Push-pull dynamics in travel decisions. In Handbook of Hospitality Marketing Management (pp. 412–439). Routledge.

Voigt, C., Brown, G., & Howat, G. (2011). Wellness tourists: In search of transformation. Tourism Review, 66(1/2), 16–30.

Waterhouse, J., Reilly, T., & Edwards, B. (2004). The stress of travel. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(10), 946–966.

Whiting, J. W., Larson, L. R., Green, G. T., & Kralowec, C. (2017). Outdoor recreation motivation and site preferences across diverse racial/ethnic groups: A case study of Georgia state parks. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 18, 10–21.

Widmar, N. J. O., Byrd, E. S., Wolf, C. A., & Acharya, L. (2016). Health Consciousness and Consumer Preferences for Holiday Turkey Attributes. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 47(2), 83–97.

Xu, X., Wang, S., & Yu, Y. (2020). Consumer’s intention to purchase green furniture: Do health consciousness and environmental awareness matter? Science of the Total Environment, 704, 1–43.

Yoo, C. K., Yoon, D., & Park, E. (2018). Tourist motivation: An integral approach to destination choices. Tourism Review, 73(2), 169–185.

Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An Examination of the Effects of Motivation and Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty: A Structural Model. Tourism Management, 26(1), 45–56.

You, X., O’leary, J., Morrison, A., & Hong, G. S. (2000). A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Travel Push and Pull Factors. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 1(2), 1–26.

Yousaf, S. (2021). Travel burnout: Exploring the return journeys of pilgrim-tourists amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Management, 84, 1–11.

Yun, S., & Kim, T. (2022). Can Nature-Based Solutions (NBSs) for Stress Recovery in Green Hotels Affect Re-Patronage Intention? Sustainability, 14(6), 1–15.

Zhang, Y., Wong, I. A., Duan, X., & Chen, Y. V. (2021). Craving better health? Influence of socio-political conformity and health consciousness on goal-directed rural-eco tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(5), 511–526.

Appendix

Scales and Their Sources

|

Variable and scale items |

Source |

|

|

Health consciousness: |

Zhang et al. (2021) |

|

|

|

I reflect about my health a lot. |

|

|

|

I am very self-conscious about my health. |

|

|

|

I am generally attentive to my inner feelings about my health. |

|

|

|

I am constantly examining my health. |

|

|

|

I am alert to changes in my health. |

|

|

|

I am usually aware of my health. |

|

|

|

I am aware of the state of my health as I go through the day. |

|

|

De-stress motivation: |

Baloglu et al. (2019) |

|

|

|

To reduce my stress levels; |

|

|

|

To let go of my worries and problems; |

|

|

|

To escape the demands of everyday life; |

|

|

|

To be refreshed. |

|

|

Desire: * |

Zhang et al. (2021) |

|

|

|

I want to visit resorts for better health. |

|

|

|

I wish to visit resorts for health benefits. |

|

|

|

I am eager to visit resorts to attain health goals. |

|

|

|

My wish to visit resorts for health reasons can be described desirably. |

|

|

Intention: * |

Zhang et al. (2021) |

|

|

|

I intend to visit resorts in the near future. |

|

|

|

I am planning to visit resorts in the near future. |

|

|

|

I will make an effort to visit resorts in the near future. |

|

|

|

I will certainly invest time and money to visit resorts in the near future. |

|

|

|

I am willing to visit resorts in the near future. |

|

* Underlined words represent modifications of the original statements, changing the type of a destination from ‘rural-eco sites’ to ‘resorts’.