Politologija ISSN 1392-1681 eISSN 2424-6034

2019/4, vol. 96, pp. 92–139 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Polit.2019.96.4

History and Methodology of Research of the Subnational Topic in Political Science

Volodymyr Hnatiuk

PhD student in Department of Political Science

at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Ukraine

E-mail v.v.hnatiuk@gmail.com

Summary. Subnational topic has come a long way from its inception fifty years ago to formation of an independent research direction. This period consists of three phases. In the first phase (early 1970’s – mid 90’s) scholars start discussing a topic that was still unexplored at the time and examine it as a fragmentary part of whole studies. The second phase (mid 1990’s – first half of 2010’s) sees changes in methodology: studies become more complex, focused solely on subnational phenomena and are carried out using a special tool – the subnational comparative method. A methodological dichotomy is outlined as a model for the analysis of subnational regimes and their types, as well. Finally, the third (current) phase (mid 2010’s – present) is where the key changes take place: formation of independent research direction, overcoming theoretical constructs (whole-national bias and federal monism) and increase of complexity and depth of political studies. These features are entrenched in the form of methodological synthesis as a modern model for the analysis of subnational regimes and their types. The article focuses on the coverage of the classical and the modern foundations of the subnational comparative method. The author notes that modern methodology juxtaposes with ontology in the context of subnational discourse. However, in the process of studying such issues there is an urgent need to clarify, update and supplement some methodological foundations of the method.

Key words: subnational topic, subnational regime, subnational comparative method, methodological dichotomy, methodological synthesis, objective and subjective measurements.

Subnacionalinių tyrimų istorija ir metodika politikos moksluose

Santrauka. Subnacionalinių tyrimų tema nuo atsiradimo iki jos, kaip nepriklausomos tyrimų krypties susiformavimo per pastaruosius penkiasdešimt metų, nuėjo ilgą kelią. Šis laikotarpis susideda iš trijų etapų. Pirmajame etape (XX amžiaus aštuntojo dešimtmečio pradžioje–dešimtojo dešimtmečio viduryje) mokslininkai pradeda diskutuoti tuo metu dar netirta tema ir nagrinėja ją kaip fragmentinę visų studijų dalį. Antrame etape (XX amžiaus dešimtojo dešimtmečio vidurys–XXI amžiaus antrojo dešimtmečio pirmoji pusė) atsiranda metodikos pokyčių. Tyrimai tampa sudėtingesni, jie orientuojami tik į subnacionalinius reiškinius ir yra vykdomi naudojant specialų įrankį – subnacionalinį lyginamąjį metodą. Taip pat pateikiama metodinė dichotomija kaip subnacionalinių režimų ir jų tipų analizės modelis. Galiausiai, trečiajame (dabartiniame) etape (XXI amžiaus antrojo dešimtmečio vidurys–ir iki šiol) vyksta pagrindiniai pokyčiai: formuojama savarankiška tyrimų kryptis, įveikiamos varžančios teorinės konstrukcijos (nacionalinis šališkumas ir federalinis monizmas), tyrimai darosi sudėtingesni ir nuodugnesni. Šios savybės yra įtvirtintos per metodinę sintezę kaip modernus subnacionalinių režimų ir jų tipų analizės modelis. Straipsnyje nagrinėjami klasikinio ir modernaus subnacionalinio lyginamojo metodo pagrindai. Autorius pažymi, kad moderni metodika subnacionalinio diskurso kontekste atitinka naudojamą ontologinį pagrindą. Kita vertus, tiriant subnacionalinių studijų klausimus būtina paaiškinti, atnaujinti ir papildyti kai kuriuos metodologinius pagrindus.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: subnacionaliniai tyrimai, subnacionalinis režimas, subnacionalinis lyginamasis metodas, metodinė dichotomija, metodinė sintezė, objektyvūs ir subjektyvūs matavimai.

Received: 30/06/2019. Accepted: 15/12/2019

Copyright © 2019 Volodymyr Hnatiuk. Published by Vilnius University Press.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Today the study of subnational topic in political science, with its well-developed theoretical and methodological framework, is in its heyday. On the other hand, the establishment of such situation was preceded by a complicated and lengthy process of finding a specific research object, its specification and methodological support.

Studies of the last quarter of the 20th century by political scientists, especially comparativists, were noted for their limited observation of subnational issues.1 Scholars were actively analysing the democratic and autocratic transitions at the national level, especially in the 1980’s and 90’s. However, in the context of such political practices, decentralization eventually determined the interest in subnational politics in the unitary and federal countries that had embarked on democratization. Therefore, at the beginning of the 21st century a new approach to the study of political institutions and processes was formed, but it was separated from the practice that flowed for almost thirty years.2 Thus, there was a need to elucidate the evolution and theoretical basis of subnational topic in political science in order to understand such phenomena of political practice that is its “ontology”. This is extremely evident, given the fact that current research increasingly addresses the analysis of subnational units. After all, the term “subnational level” has long been used as a matrix, but not as a direct research object. As of today, the number of works that comprehensively cover the theoretical and methodological aspects of the problem is rather insignificant and does not reflect the completed view, which actualizes the direction of scientific research proposed in the article.

Hence, the purpose of this article is focused on discovering and solving two key tasks: 1) to investigate the evolution of subnational topic in political science, chronologically outlining its stages and characterizing its specifics; 2) to consider methodological and conceptual foundations of the subnational comparative method and supplement them with own topical observations. At the same time, such combination is justified by the achievement of the expected purpose of exploration. It is important that the first and second issues (tasks) are concrete gaps in modern political science that are not properly (i.e. completely) studied. Accordingly, proposed article is an attempt to find a place in this complex gap in order to reflect historically, theoretically and methodologically the evolution of topic of the subnational field through the construction of questions: what was, what is, and what might subnational issue become in political science.

The article is structured into two key parts. First part has accumulated historical and theoretical elements that reproduce dynamics and basis of evolution of the phenomenon of the “subnational topic”. Second part combines methodological and conceptual aspects that outline ways and means of research and techniques for their implementation (so-called instrumental emphasis).

1. Towards a history and evolution of subnational topic in political science

First stage of history and evolution: “discovery” of the unexplored

The 1970’s marked the beginning of a long-lasting political process on a global scale. This was described as the “third wave” of democratization (S. Huntington)3, which was implemented as a transition of the national political regime from undemocratic to democratic. These processes culminated in the 1980’s and 90’s, when a significant number of countries entered transit phase – democratic or autocratic. This issue has received considerable theoretical and methodological emphasis in achievements of scholars4 who have studied the specificities of institutional (or non-institutional) changes at the national level. As a consequence, both political science and political practice have largely entered the trend and the period of decentralization.5

The processes of democratization and decentralization have determined the objective accumulation of considerable potential of centrifugal forces in transformed countries. This condition, in the end, has led to a shift of emphasis in comparative political studies – from a national (and cross-national) to a subnational level of analysis. Although the ideas for the study of this topic emerged in the early 1970’s, it began to gain scientific autonomy only in the early 21st century. The reasons for such a temporal split are hidden in the specific circumstances that were expressed in the form of theoretical constructs of the time – specific “prejudices”.

For a long period, researchers have analysed policy processes exclusively at the national level. Generally, there was an idea in science that any manifestation of political life on a smaller spatial scale – regional or local – is merely a projection of a national manifestation come to life. On the other hand, lack of interest in local politics has led to doubts about the reliability of data on subnational phenomena and processes, as well as scepticism about the possibility of generalizations due to the increase of cases on the basis of subnational units. Taken together, these reasons represent the phenomenon of “major bias”6 in political science theory. In the second half of the 20th century the main part of research that connected with democratization and autocratization was national.7 Therefore, the “whole-national bias” as a kind of prejudice has proved to be an appropriate attribute of political science from the 1970’s in comparative research.

Discussion of subnational issue8 was initiated by R. Dahl in his work “Polyarchy. Participation and Opposition”. In this work author has identified several problems that are related to it and are important to us here. The main thesis was the idea of uneven political participation and contestation within a state:

“Both past and present regimes also differ in what proportion of the population is allowed to participate relatively closely in the control and contestation of government actions, that is, the extent of their participation in the public contest system.”9

Such an outline of this idea regarding specifics of the above processes did not reflect the complete form of R. Dahl’s thought, which would integrate all possible cases of political practice. That is why the theoretical moment of extrapolation of this idea to a lower – subnational – level of analysis has become an important aspect. Accordingly, the scholar made a hypothetical classification of countries based on the possibilities of public contests by citizens. Among four types of states identified by R. Dahl, two of them are important to us: a) a competitive regime at the national level and a hegemonic regime at the level of subnational organizations; b) a competitive regime at the level of subnational organizations and hegemony at the national level. Within these types correlation between analysis of political phenomena on subnational level and the idea of uneven political participation and contestation within the whole state and in its parts is directly reflected.10 This is how the phenomenon of “juxtaposition of situations” originated, when conceptual frameworks of political science and political practice were simultaneously traced, which did not always fit into these methodological definitions. Moreover, both sides existed together in a single spatial dimension.

Thus, his achievement was the discovery of subnational theme in political science through practical (new investigations are relevant), methodological (such investigations are a necessity), and methodical (their embodiment while impossible) aspects. Although R. Dahl did not develop this issue in his work (later he called it a “great omission” of the whole study), the scholar made a key hypothesis about differentiation of regimes at national and subnational levels within a single state.11

Political researcher A. Lijphart emphasized the importance of the comparative method as a necessary tool in understanding logical series, and also separated it from interpretation as solely a technique for such implementation.12 In expressing instrumental nature of the method, he relied on an understanding of the “form of measurement”, or nonmetric ordering.13 In his work A. Lijphart highlighted weaknesses of the comparative method and moments that influence the reduction (elimination) of their negative effect in investigations. The first problem was identified as many variables, small number of cases and raised the issue of verification and reliability of the analysis results. Moreover, evidence obtained in such circumstances led to the existence of specific errors which called into question scientific value of the results. A fallibility hyperbolized in negative conclusions was the second problem of the comparative method at the time. Thus, using a comparative method was carried out within the research framework that influenced the initial data, which in turn distorted generalizability of the cases analysed.

Ways to solve (optimize) the above problems were based on the following steps: a) to increase the number of cases as much as possible (it makes it possible to more accurately represent cases in a “horizontal” section and show historical and geographical picture in unity of perception); b) to reduce analysis of “spatial properties” in cases (grouping cases based on their approximation to variables, not through spatial inclusion factor); c) to focus on variables only in controlled cases (detection of partial generalizations and operationalization of variables within controlled cases); d) to focus on key variables (generalization of main variables leads to verified results for analysed cases). If “a” and “b” refer to a problem of small number of cases, then “c” and “d” refer to a large number of variables. In applying the comparative method, A. Lijphart believed that it should be based on a small number of empirical cases. However, later the scholar noted that one of the ways to solve this complexity is increasing the number of empirical cases through “longitudinal extension”, that is, events of one kind and rank.14

In his research G. Sartori made the correlation between national and subnational levels of analysis, general understanding of system and electoral system as a cluster of specific political conditions. He noted:

“states of the Union are not sovereign… Hence, Florida or Louisiana or Mississippi, or any of the other one-party states of the United States, are not states in the sense in which Mexico and Tanzania are such.”15

However, logic behind such thinking is the path to a specific “theoretical trap”. After all, when we define different (in particular more specific than previous) criterion for analysis, we go down the ladder of conceptualization, where correlation changes. That is why:

“… subnational units are analysed in terms of system properties, also conceived at the national level. It seems that the state is actually a state.”16

Such construction reflects idea of variability objects to study and their dialectic. Because of new political realities (practices), they can often express unknown/undetected features (novelty of study). In most cases such processes go beyond current conceptual framework of their time.

These scholars were representatives of the theoretical construct “whole-nation bias” that existed during 1970’s and 80’s in political science. Such “prejudice”17 reflected the then-methodological toolkit, which was based on national level analysis of political processes. Moreover, analysis was carried out in the countries in transit. Accordingly, subnational issues (or whole topic) emerged as mediated (secondary or non-major) scientific outcomes in investigations at that time.18

Thus, an important “step to get acquainted” with subnational issue in political science was made in the period from the beginning of 1970’s to mid 90’s. Although this topic was not presented by a large number of papers, relevant theoretical background and practical results, but the main achievement was isolation of the problem and “acquaintance” with it. It became a symbolization of the first stage of subnational research in political science – period of “meeting” and opening of unexplored theme.

Second stage of history and evolution: first “contacts” and change of “prejudices”

Dominance of theoretical construction of the “whole-national bias” in comparative political science ended in the last decade of the 20th century, when various aspects of politics at the subnational level began to be studied. It has been reflected in the studies on the territorial continuation of democratization (and autocratization) in various parts of the whole country. It is very often the case that a completed transit (its democratization) did not guarantee observance of civil rights and freedoms of individuals on the ground – in subnational units. Thus, there was necessity to “scale down” in order to verify results of transits for compliance with their institutional orientation in the subnational units.

This tendency elevated local politics to prominence in comparative research in the mid 1990’s. Moreover, under influence of democratization and decentralization processes, subnational unit began to reflect qualitative-quantitative equivalent of state-level change (and its parts as well), and became a phenomenon of political life that was no longer regarded as a minimized manifestation of national politics. This situation was appropriate of both unitary and federal states.19

Argentine political researcher G. O’Donnell was one of the first who began to study some of issues within subnational topic. He put forward the idea of correlation of spatial factor with the principle of rule of law and its observance that operates in specific territory.20 Accordingly, the scholar divided the territory of Latin America into “blue” (rule of law works), “green” (rule of law works to an extent) and “brown” (rule of law is virtually absent) zones. Afterwards, G. O’Donnell noted that a democratic national regime is just a shell of complex institutional process that integrates territory in which it operates, adding:

“... polyarchy regime, which outlines entire system of regional regimes in the state, often has journalistic information and reports from human rights organizations that some of these regions function less than in the polyarchical way, that is, they are not polyarchies.”21

An important aspect is reporting from direct participants of local political life who carry out such monitoring – mass media and socio-political public organizations. After all, monitoring subnational governments and fixing their abuse of power is what should be the prerogative of active citizens in the region. Any violation otherwise is an aggravation of the principle of rule of law. In other words, “hegemony is borne from below”22 because it emerges as a result of individuals’ passive stance on subnational political processes and, consequently, territorial violations of rights and freedoms.23

Analysis of subnational units has begun to play an increasing role in comparative political science. A considerable amount of research has been conducted on issues such as ethno-national conflicts, economic, political and social reforms and democratization, which depended on comparisons of capacity between subnational units.24 However, by the end of the 20th century insufficient attention was paid to various methodological issues that arose in the course of such investigations.25

Some important gaps were eliminated thanks to the article by R. Snyder.26 He appropriately identified advantages of subnational method when applied in comparative studies within and between countries.27 The scholar has included such elements to them: a) better management of limited number of cases; b) higher accuracy in coding of analysed cases; and c) a clearer understanding of complex processes.28 They (it can be described as instrumental features of subnational method) underlie its two strengths, namely: 1) as a means of increasing number of cases for observation; and 2) as a relief for comparison of controlled cases. How does this contribute to these types of research?

Process of magnifying elements of the analysis (cases) helps to more accurately reflect averages on national scale, that is, to mitigate their shape. After all, very often an “average indicator” is an expression of something “improper” (unusual) for cases that are being compared:

“… many societies we call semi-developed on the basis of a number of national indices are really a mixture of developed and underdeveloped sectors.”29

Thus, the problem of reliability of information (its refinement or improvement) at the national and subnational levels is partially eliminated. Moreover, it enables checking reversibility of the output information within interaction of the system and its parts. As a consequence, we come to understand the nature of uneven flow of processes in the state and its parts at the same time.30 This vision outlines the prospect of concurrent research31 as an alternative to exploring problems in pursuing a common goal to understand cases better at different levels of analysis and “catch” their nature in more detail with relation to systemic discourse. R. Snyder notes the subnational method as a favourable tool for verifying such a linkage:

“... a shift to a territorially-differentiated framework in analysing a paradigmatic case serves both to call into question a longstanding model of industrialization and to open a new theoretical agenda that focuses on the linkages between distinct modes of industrialization within a single national unit.”32

Not limited to the above, the subnational method is suitable and specific for comparative studies. Its important feature is an ability to combine theories of different scales and different levels of analysis in one case. It displays as a process where theory can combine territorial units of different levels of analysis, and these territorial units can be equivalent objects in applying this theory. In this construction the concept of “subnational” allows to implement different theoretical and methodological techniques more flexibly than its counterpart “national”. After all, in subnational comparative studies, political researchers very often use either system theory, or subnational theory, or combination of these, but never the other way around.33

R. Snyder in his article identified three elements that make up the structure of the subnational method: a) research design; b) measurement; and c) theory-building. Such “combination”34 not only laid the direction of future research, but also gave it an algorithm for understanding subnational processes through the construction of “theory-concept-measurement”.35 In principle, for almost two decades, research has been subject to this scenario.36

This view on subnational issues, which now focused on deterministic rather than probabilistic causality, led to the “opening of doors” for new research in comparative political science. Additionally, cause and effect linkages contribute to research situation with a moderate number of cases where the findings can be interpreted as true.37 In short, probabilistic causality provides the average of the outcomes as too hybrid (or mixed), considering individual reports for each case in the analysis.

The first decade of the 21st century was characterized by the presence of research that showed a much greater interest in subnational issues. These studies were supported by measurement techniques and case classifications within subnational units of analysis. Furthermore, an integral attribute of most works was the presence of scholars’ concepts38 as innovative (theoretically grounded) ideas that explained why subnational units should be regarded as something more in the political and social dimension than just parts of the state.

The research39 by E. Gibson was based on cases where authoritarian regional units (autocratic enclaves) exist in a democratic state. This situation constructs a sphere of “boundary control”, which by its nature is a large-scale system of territorial governance that consists of three structural elements: the parochialization of power, the nationalization of influence, and the monopolization of national-subnational linkages. A significant contribution was the introduction of the term “territoriality” as a strategy of influence, control and management of resources, and people in the territory that are controlled by subnational governance.

Argentine political researcher C. Gervasoni in his main work40 analysed the processes of fiscal decentralization within framework of the theory of rentier state, which predetermines certain forms of subnational political regime in units of the state. He notes that “province rentierism” is a political phenomenon, not a fact that is predicated on geographical factors of resource availability. Therefore, such studies are characterized by the use of objective and subjective techniques for measuring subnational regimes and then their classifications.41

Work42 by A. Giraudy discusses problem of subnational undemocratic regimes alongside national democratic government/regime and shows it as specific cases. Moreover, she explored the factors that contributed to reproduction of such regimes in Argentina and Mexico, which in the recent past have experienced territorially uneven national democratization. Thus, the achievement of the scholar was a demonstration of an interesting concept – “the reproduction of the undemocratic regime” – in the context of democratic institutional discourse and its development.

Research43 by J. Behrend was also based on political practice in Argentina. She has developed an analytical framework – the concept of “closed game”, which reflects the completeness of political dynamics in the subregions (provinces). “Closed games” of provincial politics are a kind of subnational political regimes in which a family or group of families dominate provincial politics (in subnational unit), control access to top government positions, the media, and other business opportunities. Although, the main focus is on the power aspect, conceptually, this position expresses a more complex structure of political and social linkages between actors and citizens of whole subnational unit. As a result, the system of methods, means and ways of exercising power is fully reflected at such territorial level.

Finally, in her work A. Benton analysed and systematized the role of subnational politicians in autocratic regimes44 (as exemplified by the state of Oaxaca in Mexico). The scholar believes that their functional range is within the national level as satellite (favoured), but argues that officials often support the national regime only through meeting their local requirements. In general, all variations of strategies within national and subnational power linkages depend on the bureaucratic level of political control by politicians over all settlements in their subnational units. Some strategies are implemented on behalf of the national regime, but other strategies allow local politicians to “play” where national influence is weak.

The period between the mid 1990’s and the mid 2010’s was chronologically distinguished as the second period of subnational topic in comparative political science – the “contact” stage. The “communication” between political practice and new theory started for the first time, because only then scholars could understand it. This operation was seen as a form of constructing scholars’ concepts that not only expressed new perspective on political processes at the subnational (territorial) level, as a unique (exclusive) idea, but also created an algorithm for analysing such phenomena. It has also contributed to creation of two methodics for measuring quality of subnational unit development in relation to national democratic institutional orientation. An important change was transformation of the theoretical constructions – “prejudices” – namely: from “whole-national bias” to “federal monism”.45 Therefore, only federal states prevailed in the works of that time: Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Russia, India, the USA and others, and unitary states were dropped from this list. However, such problem has only become a matter of time.

Third stage of history and evolution: “affirmation” and scientific diversity

Tendencies of comparative research have opened up new practical areas (territorial levels) for testing concepts and techniques of measurement in subnational topic since mid 2010’s. This situation was caused by two factors.

First was a process of democratization in many unitary Latin American countries, and later economic market reforms that led to process of political decentralization.46 A common feature was that the decentralization of power has become a general tendency and process that has led to institutional change in all countries of the region, regardless of the form of government. So, Latin American countries began to elect their subnational governments. And, notwithstanding, pace, depth, and degree of decentralization of the power varied, countries were positioned as similar cases within single process, that is, formed a coherent cluster for comparative analysis. In any case, the result of this process reflected increasing relevance of political life in country, both at national, local and (or) subnational levels.47

Second factor was the result of testing a subnational comparative method in political research. With this toolkit, important conclusions were received from analysis of subnational political and social processes in many countries of the world. Scholars were not only able to demonstrate degree of uneven economic and political processes in different parts of the country (in subnational units), but also correlate them with national level in different forms in: definition, formalization and typologization.48

Thus, the above two factors have led to relevant interest in subnational issues both in theoretical and practical aspects. Moreover, scholars pursued two related goals: a) expansion of theory and methodology through political practice as a test of the “theory-concept-measurement” construct in action; and b) delineating of political processes at the subnational level and its sub-levels, based on current theoretical knowledge.

An important point for recent research was to overcome the theoretical construction of “federal monism” in comparative political science. Nowadays scientific investigations49 directly apply to unitary states as well. Furthermore, the criterion of “political order” now appears in completely different aspect, namely: status of “monopoly” has been transformed into status of “one of several”.50 The studies were not limited by phenomenological and territorial identification of the subnational political regime and limits of the administrative units of the state.51 Instead, new research areas were highlighted. It is an analysis of municipal units as an expression of some type of the subnational political regime.52 Scholars have also come up with local economic development strategies within the idea of “fragile governance” (informal planning processes),53 expanded the theory of subnational electoral communication,54 identified the economic diversification as a factor of subnational authoritarianism,55 and outlined the concept of “subnational democracy” through the phenomenon of “trajectory of development”.56 After all, studying and comparing subnational regimes was of interest not only to Latin American and American scholars (however, their contribution to this case is the largest). Additionally, such studies were complemented by works from Europe and Africa.57 Moreover, number of political researchers who are interested in this topic is constantly increasing. Today subnational topic has begun to actively internationalize, that is, become a topical issue for many countries around the world. And this is not yet the “end” for such research, since the concept of “subnational regime” is extremely variant in manifestations of political practice, multifaceted to analyse and ambiguous to interpretations.58

Accordingly, the process of “affirmation” of subnational field/theme in political science has ended. It was characterized by the fact that this topic was freed from theoretical constructs – whole-national bias and federal monism, which prevailed in comparative studies earlier and limited them. Now scholars have entered into third period – the stage of “cooperation”, which combined dynamism and variability in testing some theoretical and methodological foundations, autonomy of special tools and heterogeneous political practices at the subnational level. Simultaneously it is a system that takes a new look at objects that were still in shadow of national discourse, but are evolving according to certain rules that go beyond it.59

In the period of its institutionalization in political science, the subnational theme has accumulated some important problems that have not been sufficiently resolved at the moment, namely: a) correlation of measurement techniques (methodics) with each other and their proportionality; and 2) alignment of methodology and ontology in subnational comparative studies.

The issue of measuring processes in subnational units has emerged as an objective need to test validity of the thesis about uneven functioning of political and economic processes in different parts of the country. At the same time, the result was a confirmation of the view that democratization at the national level does not necessarily lead to democratization in all subnational parts of the country. On the other hand, scholars have received an answer about the causes of unsuccessful long-term democratization in countries with hybrid national regimes, which were based on weak institutional compliance to the democratic development in most (as not all) subnational units. Generally, a comparison of institutional development at national and subnational levels has become possible thanks to the measurement of political regimes at these two levels and their typologization as an expression of such conformity. In the course of carrying out such research, two techniques (or methodics) for measuring subnational regimes were built – objective and subjective. Until now political researchers have used only one of its species in their investigations, but very rarely have combined them in single study.60 Thus, the issue of correlation of the measurement results was not raised at the theoretical level and not confirmed by practical studies. The problem of the proportionality between these techniques was also omitted. It means that there is still a gap in subnational studies regarding measurement results. For now, conclusions that obtained in the process of validation of objective or subjective techniques are equivalent, but not because they produce identical results (there are no examples of such studies), but are methodologically equivalent as tools for study of subnational units. Not only will the solution of this issue strengthen the position of the two techniques as alternative and valuable,61 but it will also help to formulate a probable unified measurement technique in the future.62

The aligning of methodology and ontology in subnational studies also has been put in the category of “unresolved” because of lack of the direct investigations in such formulation. On the other hand, researcher P. Hall has come up with this issue in the context of comparative political science, which may well coincide with subnational level of analysis in such view.63 Accordingly, his view is right to “scale down”, that is, lower to a level below – from the national to subnational, to understand the idea in relevant aspect. It was important for subnational studies that such “aligning” became indispensable, since its implementation was impossible during existence of theoretical constructs (whole-national bias and federal monism) in political science. There was an urgent need to eliminate them. For a long time, scholars only noted about the problem, that is, appealed to its “ontology”, but could not study it due to the lack of methods of the observation, i.e. “methodology”. P. Hall emphasizes:

“If a methodology consists of techniques for making observations about causal relations, an ontology consists of premises about the deep causal structures of the world from which analysis begins and without which theories about the social world would not make sense. At a fundamental level, it is how we imagine the social world to be.”64

Accordingly, only in such a synthesis (or form) it is possible to fully reflect social processes that are not only properly understood, but also appropriately measured. There are times when an ontology is often ahead of methodology that is simply incapable of “understanding” processes that it displays through causation and effects of their interaction. As a consequence, development of methodology was stimulated thanks to scholars and their new methods and tools.

P. Hall notes that analysis of social phenomena and their explanation is based on the principle of multivariate. That is why ontology objectively does not require a single methodology, because:

“There is no single solution to the methodological quandaries posed by contemporary ontologies. That they pose genuine dilemmas is reflected in the growing range of responses from thoughtful scholars.”65

He also adds that their “alignment” should be carried out in a new approach that is based on variables and cause and effect linkages.66 Its specificity is manifested in the fact that it emphasizes actions concerning processes that unfold in specific cases and the results in those cases. All this is done to make sure that the actions and causes that affect showing the processes become a reflection of the theory that defines them. As a consequence, we need to see cases not solely in causality and effects of their interaction, but to observe (understand) them within holistic approach, because:

“Progress in social science is ultimately a matter of drawing fine judgments based on a three-cornered comparison among a theory, its principal rivals, and sets of observations.”67

In such vision highlights the problem of “alignment” of ontology and methodology in comparative studies. The above idea is also appropriate for subnational level. The new approach that is capable to combine necessary method attributes and fundamental understanding of processes in cases may well be expressed as the “theory-concept-measurement” construction which was mentioned above in details in this part of the article.68

2. Towards a methodology and conceptualization of subnational comparative method in political science

Classic foundation of the subnational comparative method

Comparison of controlled cases at the subnational level were quite clearly outlined in work69 by R. Snyder. The researcher notes two strategies for carrying out such research: a) within-nation; and (b) between-nation. On the one hand, they are limited by a certain territorial space (country or countries) that reflect their forms of orientation. On the other hand, their content was determined by research goals, that is, what scholar wants to learn when choosing one of them. Therefore, R. Snyder observed that in “within-nation” comparisons, political researchers seek clarification, or detail, for processes that are characterized by ambiguous interpretations at the level of the whole system, and thus by a possible fallacy in subnational cases. In “cross-nation” comparisons, scholars are trying to get a more objective picture of the processes that are more appropriate to view in such an intersystem format than within a single system and cases within it. However, these strategies were not only focused on territorial orientation, but also based on two different grounds (foundations) regarding the role of “territory” in achieving their aforementioned goals. The first basis could be defined as an “approximation effect”, consistent with “first law of geography” by W. Tobler – “everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant ones.”70 The second foundation was characterized by D. Rustow’s classic opinion about understanding of spatial consequences of the territory interactions – “mere geographic proximity does not necessarily furnish the best basis of comparison.”71 In general, it can be describe as an “effect of spatial consequences”. Moreover, two strategies can be actively combined in one study. Thus, the advantage of the subnational comparative method and its implementation strategies relate to situations where it is possible to apply theories that explain dynamic interconnections between different levels and regions of the political system.

Scholar L. Tillin in her work72 posed a group of questions – “what, how and why” – as a kind of methodological support for analysing the subnational level of politics. She also identified status of subnational level as autonomous in relation to national expression. As a consequence, the above questions became a kind of methodological toolkit for identifying fundamental grounds for phenomenon, that is, its ontology. The question of “why” made it possible to carry out analysis in the context of “false exclusivity” or understand the cases of “erroneous universality”.73 Instead, the question of “what” and “how” are a positive reduction to attributes and characteristics of the phenomena which are being analysed.74 These are basics that are expressed through various processes in subnational units and are interpreted as inherent to them. At the same time, L. Tillin adds about the task of existing literature that exposes subnational issues as to become an experienced tool and source from which new ideas emerge.

E. Gibson’s views concern several methodological aspects whereas we study subnational political regimes75 – autocratic and democratic. First of all, we should start by identifying subnational processes. He understands them as processes that unfold in their own specificity, not processes that are identical to national, but in different territorial perception. Thus, not only the idea of separation of the levels of analysis is formed, but their peculiar uniqueness and identity are emphasized.76

The scholar contemplated two conceptual questions in his work. Their purpose was outlining the concept of “subnational democratization” as a separate political phenomenon and identifying fundamental grounds on which such operation was carried out.

The first question was about democratization at the national and subnational levels and need to differentiate them (“democratization: national or subnational, does it matter?”). The scholar points to vertical and horizontal sovereignty that allows for an alternative institutional path in the state, that is, the ability to “move differently”. It led to creation of various strategies for political actors that influenced democratization processes at the local level. As a consequence, scenarios that reflect ways of transformation within subnational autocracy/democracy can be very diverse if one understands clearly the relationship between national and subnational political dynamics in territorial units. Moreover, system effects became key reasons of changes, namely: in each system, transformation in one subsystem causes changes in another, and therefore specificity of one subsystem will, of course, affect other units of that system.77

The second question was about situation of the existence of two types of democracy in the state – substantive and territorial (“territory, politics, and democratization”). And if the first is a grant of rights that were not previously available in the country (for example, a new constitution or spread of existing rights for new categories of population), then the second is an extension of the rights in certain subnational units. It is consistent with situation where residents of one part of the country are granted rights that are available to residents of other parts of this country. In general, territorial policy does not have to interpret the territory itself, but how this policy emerges through that territory. Therefore, an important contribution of E. Gibson’s work was introduction of new terms: a) “territoriality” as a strategy of influence, control and management of resources, and people in the territory that controlled by subnational governance; (b) “territorial system” as a synthesis of interacting national and subnational political jurisdictions whose governments exercise sovereignty over territorially restricted territories; c) “territorial regime”, which regulates the interaction between territorial units of the state and directs the division of powers between the governments of subnational territorial units and the national government.78

One of the most important conceptual bases of the subnational comparative method is the idea of “political conflict”, which will be considered here in three forms.79 In a way, this is a basis that explains the algorithm for deploying and emergence of the subnational regimes and their duration.

The first form is based on the view of the American political scientist E. E. Schattschneider80 and expresses the general logic of political conflict. The scholar notes that in any situation of political conflict between two parties the main incentive of the stronger side is to keep the conflict as private as possible. Thus, in this situation there is an unequal power match between the two parties, and in the conflict stronger side is likely prevail.81 E. E. Schattschneider emphasized the weaker party wants the number of parties of the conflict to increase. As a consequence, the extension of conflict field affects the balance between two original parties. Such process was defined as the “socialization” of that conflict. This idea not only reflects a political conflict at the level of small territory, but establishes an “ontology” on which phenomenon of subnational regimes arises.

In view of the idea of political conflict described above, E. Gibson took it as basis and presented its second form. He designed a framework that covers the context of conflict control and changes in authoritarian provinces in situations where whole-national politics are democratic. Thus, the idea of subnational regime arises from an awareness of the heterogeneity of system in its subsystems, which are interdependent and exist as completeness in territorial space of that system. Therefore, the presence of another institutional set of rules and behaviours in the subnational unit leads to the “way out” of democratic national discourse. Political researcher displayed political conflict, logic of its course and consequences of this process for establishing a subnational political regime in the state in the following way:

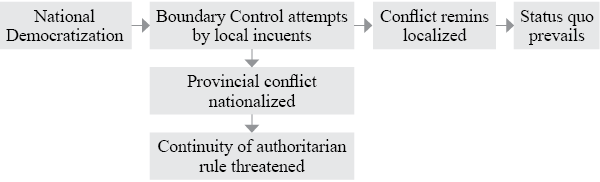

Figure 1. Political conflict and its unfolding in the view of E. Gibson

Accordingly, the localization of the conflict leads to establishment and long-term functioning of subnational autocratic regimes within framework of nation-wide democracy. This phenomenon has been outlined as an enclave of authoritarianism in political practice.

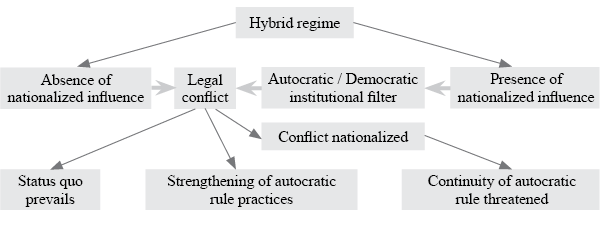

The third form of political conflict is embodied within existing hybrid regime at the national level.82 In general, there are three “plots” that cover the effects of the interaction of national influence, local conflict, and subnational unit in which this occurs. They can be displayed in a single scheme:

Figure 2. Political conflict in hybrid regime (author’s elaboration)

The explanation for these “plots” is as following:

1) the nationalization of influence with regard to local conflict does not occur, its socialization is not carried out, and the subnational regime remains autocratic, that is, as it was before. Balance of power between two original parties remains unchanged;

2) the socialization of local conflict does not occur, because local authority is in partnership with national government, which only strengthens autocratic rule in the subnational unit. In this situation, there is an unequal power match between two original parties and in the conflict, of course, the stronger side will prevail;

3) the nationalization of influence with regard to local conflicts begins with a specific autocratic-democratic institutional filter which dominated democratic practices. Expanding of the conflict field breaks balance between two original parties. Upon completion of the process, that is, the nationalization of the conflict, there is a direct threat to the continuation of autocratic ways of governing in the subnational unit. Democratization begins again.

The view, which combined the three forms of political conflict, reflects two deterministic mechanisms – the “top” and the “bottom” factor. In short, the first is a projection of how the national authorities may or may not influence the establishment of subnational political regime in the units of the state.83 On the other hand, the second is a construction that integrates the concept of “self-reproduction” of the hybrid national regime through subnational regimes and ontological principle of exclusivity as an expression of the peculiarities of this phenomenon.84

It should also be noted about the concept of “space” as a geoinformation structure that determines the development of spatial thinking in the three stages of the analytical project – conceptualization, theorization and analysis. I. Harbers and M. C. Ingram in their study85 considered that a spatial perspective can increase potential of the subnational method. Moreover, the “perception of space seriously” integrates empirical and theoretical meaning into one context. An important consequence is a neediness to fully recognize the structural dependence that exists among observation units, and therefore study of subnational units always reflects an instrumental manifestation of conceptual basis of the theory.86

Thus, the classical basis of the subnational comparative method described above is represented by a small group of views, but with relevant theoretical observations and concepts. The methodology that has encompassed toolkit for study of phenomena at the subnational level is quite corresponding to its own ontology. Although, in the process of studying such theme, there is an urgent neediness to clarify, update and supplement some methodological foundations of the method in our time.

Modern basis of the subnational comparative method

As a result of overcoming theoretical constructs in political science, new features emerged in the process of comparative research. First of all, there was a transformation of “research range”, that is, extension of the number of criteria (their system) that determine the number of allowed objects87 for analysis. Thus, it is necessary to note the “development of objects” feature.

For such studies a central notion is the subnational political regime.88 This category is a result of the relationship between political phenomena, not a constant of political being. In short, it is an expression that reflects connections between elements of this being. As a result, the concept is not “obligatory”, but appears in the “exception” or “rule” status. These linkages are outlined in three specific ways – the correlation forms.

The first correlation form is noted by political researchers G. Sartori and his ideological colleagues,89 who believed that policy analysis was carried out only at the state and sub-state levels. This choice was caused by the state system and its forms as a key factor for such determination.90 Therefore, this binding was formulated by them as:

in the state with polarized national regime – democratic or autocratic – the existence of subnational political regime is conditioned by state system – unitary or federative.91

Within the second correlation form the attention was focused on the linkages between ambivalent political regime (anocracy) and state system (unitary or federal). In this context the situation with built-in “hybrid regime” emerged as a specific expression of nature of the power relations between the state and its administrative parts. Thus, a type of regime is the main factor in determination of subnational processes in the country.92 This form was expressed as:

the hybrid regime (anocracy) causes an emergence of subnational political regimes, regardless of structure of the political system in which it flows.93

Accordingly, the third correlation form reflects the linkages between the “national regime” and local self-government. The last of both above is a special refinement of subnational processes, reflecting their course and specific nature of the social sector.94 Therefore, this idea was outlined as:

a form of functioning of the local self-government conditioned by the type of national regime in the state in which this form operates. As a consequence, it gives а “strengthening effect” for actual regime in the subnational unit.95

Based on this statement,96 there are three possible combinations that display institutional linkages between these elements of political being, namely:

1) if the national regime is democratic, then the functioning of the local self-government is successful and effective and, as a result, local politics proceed in the form of local democracy, and therefore the type of subnational political regime is also democratic;

2) if the national regime is autocratic, then the functioning of the local self-government acquires the status of formal continuation of state power on the ground, and the policy proceeds in the form of local autocracy, so the type of subnational political regime is also autocratic;

3) if the national regime is “hybrid”, then the functioning of the local self-government can take different forms: a) active; b) neutral; and c) passive. This determines a particular type of local politics – democratic or autocratic as exceptional, relatively democratic or relatively autocratic as characteristic, and thus the type of subnational political regime is completely extrapolated to the type of local politics.

As a result of this relationship a unity was obtained, which was expressed through the interdependence of the three categories and additionally took into account the factor of state system. It can be displayed as:

Table 1. Logic of interdependence of the categories “national regime”, “state system” and “local self-government” and its results (author’s elaboration)

|

National regime types |

Democratic |

Autocratic |

Hybrid (Anocratic) |

|

Regime dependence of the state system |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

The status of the subnational political regime |

Exception |

Exception |

Rule |

|

The status of functioning of the local self-government |

Active |

Passive |

Forms of alternation |

Hence, the category of “subnational political regime” should be analysed solely in the context of discourse in which role of elements of political being – national regime, state system and local self-government – are criteria that arrange types of subnational regimes.97 Such a formulation emphasizes the feature of the “development of objects” through historical retrospective, process of “scientific liberation” from theoretical constructs, and extension of “research range” in current subnational studies.98

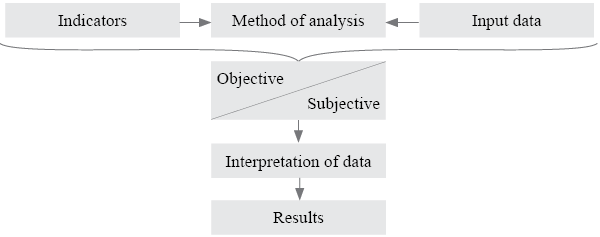

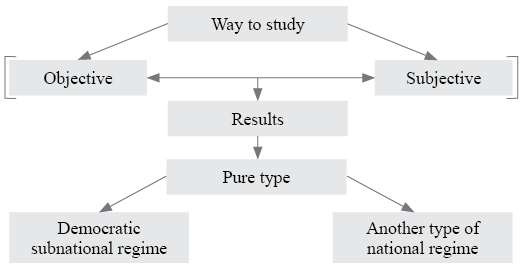

An equally important aspect has been the development of ways to study subnational regimes. Such methodological peculiarity was accompanied by an understanding of the political processes (their direction) at the subnational level through interpretation of indicators of different nature. It led to emergence of methodological dichotomy.99 In general, it was a situation where scholars designed the techniques (or methodics) in two forms100 – objective and subjective. The ways of study reflected specific aspects when selecting the source on which it was based, namely: a) electoral and institutional indicators, or b) opinions of local experts. As a consequence, these sources have become the key factors for technique building. Therefore, the model of their occurrence can be schematically represented through the following algorithm:

Figure 3. Methodological dichotomy as a model for analysis of the subnational regimes types (author’s elaboration)

Accordingly, the methodic is a synthesis of general and special parts of the study, where the first includes a source of the technique, and the second – specific indicators that are selected for analysis. As a result, scholars received a group of subnational regimes that can be classified, correlated, and displayed in the context of comparison with national regime.101 The purpose of such research is demonstrating the uneven flow of political and economic processes throughout the country.102 These studies have been implemented in two forms.103

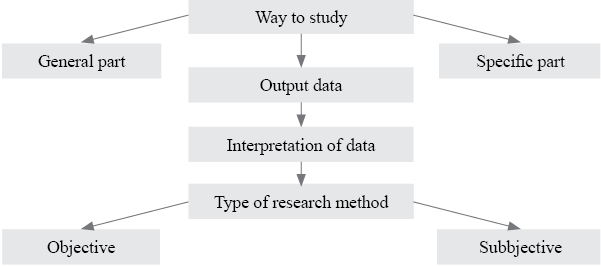

However, the research tendency has sufficiently quickly modified into a new approach.104 The model of methodological dichotomy has been replaced by the model of methodological synthesis. The feature of the new view was characterized by an integrity of discourse, which combined two kinds of sources for foundation of the methodics, which contributed to the results at a more complex level than before. Thus the model of methodological synthesis can be displayed through the following algorithm:

Figure 4. Methodological synthesis as a model for analysis of the subnational regimes types (author’s elaboration)

Studies that were conducted through such model integrate both types of sources of the methodics (objective and subjective indicators), and therefore analyse subnational phenomena much more fully. As a consequence, it helped to obtain more accurate institutional results in reflecting processes in subnational units, and expand the theoretical basis for application of such toolkit.105

Another feature was methodical.106 It is based on the principle of A. Karenina107 and combines two important moments: a) articulation and aggregation of the all factors that determine a course of political processes at the subnational level; and b) synthesis of factors into integrity that determine specific types of subnational political regimes. It can be outlined as follows:

there are number of ways in which a combination of data breaks the null hypothesis, and only one option in which this hypothesis works.

As a result, the principle reflects the situation where any success is probable only if all the factors are present at the moment, and therefore the absence of at least one condition contributes to the process of transformation of this “success” into something else. If the “success” can be denoted as S0, then any other situation will be expressed as S0 – (∑d1+d2+...dn).108 Moreover, the variability of situations will fluctuate from the number of determinants that are absent in the analytical case. The important thing is not only the representation of the horizontal determinants (the number of conditions), but also their vertical expression (the degree of deviation of the conditions from the standard value).109 Thus, “success” is a subnational democratic regime, and all other forms are a plurality of political regimes from anocratic to autocratic types.

The implementation of objective and subjective techniques in the study of subnational regimes is quite appropriately based on the principle of A. Karenina. In fact, in the presence and actual functioning of all democratic institutions, the type of regime will be defined as “purely democratic”,110 and all other types will be numerous variations in the linear development from autocracy to democracy. Furthermore, the degree of remoteness from “ideal condition” leads to establishment of the subnational political regime type that reflects the extent and intensity of these processes depending on regime of “pure type”. Such comparison demonstrated the degree of democratic rapprochement and autocratic distinction between subnational and national levels, as well as their institutional conformity to “pure type” of democracy. As a result, the algorithm of formation of the research technique was as follows:

Figure 5. Formation of research techniques which were based on the principle of A. Karenina (author’s elaboration)

Especially important was the understanding of what a democratic regime is and how its conceptual definition is expressed. Accordingly, there were two possible interpretations. The first form expressed R. Dahl’s view about of democracy as an ideal. In such context the functioning of the political system is aimed at the development of democratic institutions. Thus, democracy is seen as a process of regime self-realization that can always be improved upon. Therefore, achieving finish is unrealistic, because a process is primary and goal is secondary. Hence, the classification of regimes is carried out throughout the discourse of “another type of subnational regime”, where there are regimes – close to democracies, full-fledged anocracies and different autocracies. The second form addresses democracy as a real phenomenon that is quite achievable for the political system. As a result, democracy is an actual set of institutional practices that make it possible to establish such type of regime, if adhered to them. In other cases, there are regimes with distinct institutional features – both anocracy and autocracy.111 Comparative studies are currently dominated by the second version for the study of subnational regimes and their classification. Its advantage is a clearer correspondence between theoretical underpinnings of democracy and actual political practice than only relation to the ideal, in order to demonstrate the form of democratic proximity as maximize of functioning of the regime.

Thus, the modern basis of the subnational comparative method emerges as an intense result of scientific research in ways of study of the specific political practices in different parts of the world. Nowadays a considerable number of issues have been solved within methodological, methodical and conceptual aspects. On the other hand, subnational research field remains an open topic for various innovations, which are attracting more and more scholars.

Conclusions

Over the last half-century, subnational topic has gone a long way toward becoming a part of comparative political science: from “discovery” of unexplored to forming an independent research direction, its “affirmation” and scientific diversity. As any scientific research field, it has its evolutionary stages, which outline their originality. Also additional markers for each period became key figures, basic ideas and concepts, and field of scientific exploration, which can be summarized as a single data set, which is as follows:

Table 2. Evolution of subnational topic and features of its methodology in political comparative science (author’s elaboration)

|

Stage |

І |

ІІ |

ІІІ |

|

Chronological framework |

Early 1970’s – |

Mid 1990’s – |

Mid 2010’s – present |

|

Key personalities |

R. Dahl, S. Rokkan, A. Lijphart, G. Sartori |

G. O’Donnell, R. Snyder, E. Gibson, C. Gervasoni, A. Giraudy, E. Benton, J. Behrend |

F. Freidenberg, J. Suárez-Cao, M. Batlle, L. Wills-Otero, J. F. Pino Uribe, K. Eaton, L. Tillin |

|

Basic ideas and concepts |

Subnational contestation and participation, whole-national bias, longitudinal expansion, situation of correlation change |

Regional regime, territorial and law correlation, subnational comparative method, boundary control, territoriality, rentierism, subnational undemocratic regime, “closed games” of provincial politics, federative monism |

Synthetic dynamism of the theoretical and practical field of research, trajectory of development of the political regime, subnational economic nationalism, subnational structures and practices |

|

Field of scientific researches |

National political regime, transit states |

Federal states |

Federal and unitary states, structural subdivision of subnational units (municipality) |

|

Peculiarities of researches |

Indirect, fragmentary, minimal remarks |

Direct, selection, within methodological dichotomy |

Direct, combined, within methodological synthesis |

From the beginning of evolution of the subnational topic, there was a long confrontation between its “ontology” and “methodology”. It is due to the fact that scholars understood subnational phenomena through inappropriate toolkits to carry out such analysis. The process of their “alignment” began in the 21st century, when political researchers identified the subnational comparative method, its strengths and research capabilities. That is, the methodology “caught up” with the ontology. Moreover, on the basis of the subnational method, techniques were developed for the study of subnational regimes. The typical feature of these techniques was the methodological dichotomy as a division of the source into objective and subjective dimensions. However, this feature was later transformed into the methodological synthesis. As a result, it influenced the style of subnational research: at first it was fragmentary and then it became combined.

Hence, the value of subnational research in the end of 2010’s is only intensified, given that the political life of the society is moving in two interdependent directions: it simultaneously internationalizes and localizes. A subnational unit became not only a form, where economic and political processes flow, but also a basis for their interpretation on a larger scale. The specificity of subnational topic contributes to changes and innovations in the implementation of various methodological techniques in study of subnational units and their structural elements. Flexibility of applying the subnational comparative method allows to hope for creating unified methodic in the future, but now this issue in political science is difficult to solve.

List of references

Beer C. C., “Institutional Change in Mexico: Politics after One-Party Rule,” Latin American Research Review 37 (3), 2002, p. 149–161.

Behrend J., “The Unevenness of Democracy at the Subnational Level: Provincial Closed Games in Argentina,” Latin American Research Review 46 (1), 2011, p. 150–176, <https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2011.0013>.

Behrend J., Whitehead L., “Prácticas iliberales y antidemocráticas a nivel subnacional: enfoques comparados,” Colombia Internacional 91, 2017, p. 17–43, <https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint91.2017.01>.

Benton A., “How Does the Decentralization of Political Manipulation Strengthen National Electoral Authoritarian Regimes? Evidence from the Case of Mexico,” Paper prepared for the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago, August 29–September 1, 2013.

Borges A., “Rethinking State Politics: The Withering of State Dominan Machines in Brazil,” Brazilian Political Science Review 1 (2), 2007, p. 108–136.

Botana N., “El Cénit del Poder,” La Nacion, May 4, 2006.

Collier D., Levitsky S., “Democracy with Adjectives: Conceptual Innovation in Comparative Research,” World Politics 49 (3), 1997, p. 430–451, <https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.1997.0009>.

Dahl R., Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972.

Diamond J. M., Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1997.

Fishman R. M., “Divergent Paths: Labor Politics in Barcelona and Madrid,” Gunther R. (ed.), Politics, Society, and Democracy. The Case of Spain, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1993.

Fox J., “How does Civil Society Thicken? The Political Construction of Social Capital in Rural Mexico,” World Development 24 (6), 1996, p. 1089–1103, <https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750x(96)00025-3>.

Fox J., “Latin America’s Emerging Local Politics,” Journal of Democracy 5 (2), 1994, p. 105–116.

Fox J., The Politics of Food in Mexico. State Power and Social Mabilization, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993.

Freidenberg F., Suárez-Cao J., eds., Territorio y poder: Nuevos actores y competencia política en los sistemas de partido multinivel en América Latina, Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 2014.

Gervasoni C., “A Rentier Theory of Subnational Democracy: The Politically Regressive Effects of Fiscal Federalism in Argentina,” PhD Thesis at Graduate School of the College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame, Indiana, 2011.

Gervasoni C., “A Rentier Theory of Subnational Regimes: Fiscal Federalism, Democracy, and Authoritarianism in the Argentine Provinces,” World Politics 62 (2), 2010, p. 302–340, <https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043887110000067>.

Gervasoni C., “Measuring Variance in Subnational Regimes: Results from an Expert-Based Operationalization off Democracy in the Argentine Provinces,” Journal of Politics in Latin America 2 (2), 2010, p. 13–52, <https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802x1000200202>.

Gervasoni C., “Subnational Democracy in (Cross-National) Comparative Perspective: Objective Measures with Application to Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, Uruguay and the United States,” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the APSA, New Orleans, 2012.

Gervasoni C., Nazareno M., “La relación entre gobernadores y legisladores nacionales: Repensando la ‘conexión subnacional’ del federalismo político argentino,” Política y gobierno 24 (1), 2017, p. 9–44.

Gibson E. L., “Boundary Control: Subnational Authoritarianism in Democratic Countries,” World Politics 58 (1), 2005, p. 101–132, <https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2006.0018>.

Gibson E. L., “Politics of the Periphery: An Introduction to Subnational Authoritarianism and Democratization in Latin America,” Journal of Politics in Latin America 2 (2), 2010, p. 3–12, <https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802x1000200201>.

Gibson E. L., Calvo E., “Federalism and Low-Maintenance Constituencies: Territorial Dimensions of Economic Reform in Argentina,” Studies in Comparative International Development 35 (3), 2000, p. 32–55, <https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02699765>.

Gibson E. L., “Subnational Authoritarianism and Territorial Politics: Charting the Theoretical Landscape,” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the APSA, Hynes Convention Center, Boston, August 28, 2008.

Giraudy A., “The Politics of Subnational Undemocratic Regime Reproduction in Argentina and Mexico,” Journal of Politics in Latin America 2 (2), 2010, p. 53–84, <https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802x1000200203>.

Giraudy A., Democrats and Autocrats: Pathways of Subnational Undemocratic Regime Continuity within Democratic Countries, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Hall P. A., “Aligning Ontology and Methodology in Comparative Research,” Mahoney J., Rueschemeyer D. (eds.), Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 373–404, <https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511803963.012>.

Hansen M. P., “Becoming Autonomous: Indigeneity, Scale, and Schismogenesis in Multicultural Mexico,” PoLAR Political & Legal Anthropology Review 41 (S1), 2018, p. 133–147, <https://doi.org/10.1111/plar.12258>.

Harbers I., Matthew C. I., “Politics in Space: Methodological Considerations for Taking Space Seriously in Subnational Comparative Research,” Paper prepared for the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington, DC, August 28–31, 2014, <https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2552002>.

Harrison J., “From Competitive Regions to Competitive City-Regions: A New Orthodoxy, but Some Old Mistakes,” Journal of Economic Geography 7 (3), 2007, p. 311–332, <https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm005>.

Heller P., “Degrees of Democracy: Some Comparative Lessons from India,” World Politics 52 (4), 2000, p. 484–519, <https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043887100020086>.

Hendriks F., Loughlin J., Lidström A., eds., “European Subnational Democracy: Comparative Reflections and Conclusions,”The Oxford Handbook of Local Regional Democracy in Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 715–742.

Huntington S. P., The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

Kalleberg A. L., “The Logic of Comparison: A Methodological Note on the Comparative Study of Political Systems,” World Politics 19 (1), 1966, p. 69–82, <https://doi.org/10.2307/2009843>.

Kenawas Y., “The Rise of Political Dynasties in Decentralized Indonesia,” Master Thesis at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Academic Year 2012/2013.

Kent E., “Disciplining Regions: Subnational Contention in Neoliberal Peru,” Territory, Politics, Governance 3 (2), 2015, p. 124–146, <https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2015.1005126>.

Kent E., Prieto J. D., “Subnational Authoritarianism and Democratization in Colombia: Divergent Paths in Cesar and Magdalena,” Hilgers T., Macdonald L. (eds.), Violence in Latin America and the Caribbean Subnational Structures, Institutions, and Clientelistic Networks, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017, p. 153–172.

Kent E., Territory and Ideology in Latin America: Policy Conflicts between National and Subnational Governments, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Kesselman M., Rosenthal D., Local Power and Comparative Politics, Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1974.

Kikuchi H., ed., “Political Careers and the Legislative Process under Federalism,” Presidents versus Federalism in the National Legislative Process, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan IDE-JETRO Series, 2018, p. 19–89, <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90113-8_2>.

Lijphart A., “Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method”, American Political Science Review 65 (3), 1971, p. 682–693, <https://doi.org/10.2307/1955513>.

Linz J. J., Miguel A. de, “Within-Nation Differences and Comparisons: The Eight Spains,” Merritt R. L., Rokkan S. (eds.), Comparing Nations: The Use of Quantitative Data in Cross-National Research, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966.

Locke R. M., Jacoby W., “The Dilemmas of Diffusion: Social Embeddedness and the Problems of Institutional Change in Eastern Germany,” Politics and Society 25 (1), 1997, p. 34–65, <https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329297025001003>.

Locke R. M., Remaking the Italian Economy, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Makara S., “Decentralisation and Good Governance in Africa: A Critical Review,” African Journal of Political Science and International Relations 12 (2), 2018, p. 22–32.

Mera M. E., “Subnational Autocratic Governments in Latin America: The Impact of Economic Diversification,” Revista de Globalización, Competitividad y Gobernabilidad 12 (1), 2018, p. 63–77.

Montero A. P., “Delegative Dilemmas and Horizontal Logics: Subnational Industrial Policy in Brazil and Spain,” Paper presented at the Third Meeting of International Working Group on Subnational Economic Governance in Latin America and Southern Europe, San Juan, August 26–28, 2000.

Montero S., Chapple K., “Peripheral Regions, Fragile Governance: Local Economic Development from Latin America,” Montero S., Chapple K. (eds.), Fragile Governance and Local Economic Development: Theory and Evidence from Peripheral Regions in Latin America, London: Routledge, 2018, p. 1–18.

O’Donnell G., “On the State, Democratization and Some Conceptual Problems: A Latin American View with Glances at Some Post-Communist Countries,” World Development 21 (8), 1993, p. 1355–1370, <https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750x(93)90048-e>.

O’Donnell G., “Polyarchies and the (Un)Rule of Law in Latin America: A Partial Conclusion,” Mendez J., Pinheiro P., O’Donnell G. (eds.), The (Un)Rule of Law and the Under privileged in Latin America, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999, p. 303–338.

Putnam R. D., Leonardi R., Nanetti R. Y., Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Rokkan S., Citizens, Elections, Parties: Approaches to the Comparative Study of the Processes of Development, Nueva York: McKay, 1970.

Rubin J. W., Decentering the Regime. Ethnicity, Radicalism, and Democracy in Juchitân, Mexico, Durham: Duke University Press, 1997.

Rustow D. A., “Modernization and Comparative Politics: Prospects in Research and Theory,” Comparative Politics 1 (1), 1968, 37–51, <https://doi.org/10.2307/421374>.

Samuels D. J., “Careerism and its Consequences: Federalism, Elections, and Policy-Making in Brazil,” Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Political Science, University of California, San Diego, 1998.

Sartori G., Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Schattschneider E. E., The Semisovereign People: A Realistʼs View of Democracy in America, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1960.

Snyder R., “Scaling Down: The Subnational Comparative Method,” Studies in Comparative International Development 36 (1), 2001, p. 93–110, <https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02687586>.

Suárez-Cao J., Batlle M., Wills-Otero L., “El auge de los estudios sobre la política subnacional latinoamericana,” Colombia Internacional 90, 2017, p. 15–34.

Tarrow S. G., From Center to Peripherv: Alternative Models of National-Local Policy Impact and an Application to France and Italy, Ithaca, NY: Western Societies Program, Cornell University, 1976.

Tarrow S. G., Peasant Communism in Southern Italy, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967.

Tendler J., Good Government in the Tropics, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Tillin L., “National and Subnational Comparative Politics: Why, What and How,”

Studies in Indian Politics 1 (2), 2013, p. 235–240, <https://doi.org/10.1177/2321023013509153>.

Tilly Ch., The Vendée, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1964.

Tobler W. R., “A Computer Movie simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region,” Economic Geography 46 (1), 1970, p. 234–240, <https://doi.org/10.2307/143141>.

Uribe J. F. P., “Entre democracias y autoritarismos: una mirada crítica al estudio de la democracia subnacional en Colombia y Latinoamérica,” Colombia Internacional 91, 2017, p. 215–242, <https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint91.2017.07>.

Uribe J. F. P., “Régimen y territorio. Trayectorias de desarrollo del régimen político a nivel subnacional en Colombia 1988–2011,” Documentos del departamento de Ciencia Política 23, 2013.