Politologija ISSN 1392-1681 eISSN 2424-6034

2019/3, vol. 95, pp. 83–100 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Polit.2019.95.6

Telegram as a Means of Political Communication and its use by Russia’s Ruling Elite

Alexey Salikov

PhD, Leading Research Fellow, Centre for Fundamental Sociology,

National Research University Higher School of Economics

Email: dr.alexey.salikov@gmail.com

Summary. This article examines the use of Telegram as a means of political communication by the ruling political elite in Russia (both external, i.e., communication with the society and other political forces, and internal, i.e., between different, often rival, groups within the elite itself). While Telegram is illegal at the official level, and attempts have been made to block it in Russia since April 2018, unofficially the Russian authorities continue to actively use Telegram channels for political communication and influencing public opinion as well as for monitoring the mood of the public. What is the reason for this ambivalent attitude toward Telegram? What makes it so attractive for the Russian establishment? How are the authorities using Telegram for their own purposes? Answering these questions is the main goal of this study.

Keywords: Telegram, Telegram channels, political communication, Russia, Russian establishment, Russian authorities, Russian political elite.

„Telegram“ kaip politinės komunikacijos priemonė ir jos naudojimas Rusijos valdančiojo elito rate

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje nagrinėjama, kaip socialinis tinklas „Telegram“ valdančiojo Rusijos politinio elito naudojamas kaip politinės komunikacijos priemonė (tiek išorinei komunikacijai, t. y. bendravimui su visuomene ir kitomis politinėmis jėgomis, tiek vidinei, t. y. tarp skirtingų, dažnai konkuruojančių elito grupių). Nors „Telegram“ oficialiai yra neteisėtas ir nuo 2018 m. balandžio Rusijoje buvo bandoma jį blokuoti, neoficialiai Rusijos valdžia ir toliau aktyviai naudoja „Telegram“ kanalus politinei komunikacijai, taip pat siekdama formuoti visuomenės nuomonę ir stebėti visuomenės nuotaikas. Kokios yra tokio dviprasmiško požiūrio į „Telegram“ priežastys? Kuo šis kanalas toks patrauklus Rusijos valdančiajam sluoksniui? Kaip valdžios institucijos naudoja „Telegram“ savo tikslams? Atsakymai į šiuos klausimus yra pagrindinis šio tyrimo tikslas.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: „Telegram“, „Telegram“ kanalai, politinė komunikacija, Rusija, Rusijos valdžia, Rusijos politinis elitas.

Received: 02/09/2019. Accepted: 30/10/2019

Copyright © 2019 Alexey Salikov. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

For a long time, until the beginning of the 2000s, the scientific community had been dominated by the optimistic idea that the Internet and the new information and communication technologies (ICT) would bring technological and social progress with their improvement and should therefore certainly contribute to democratization1 and “constitute a threat to authoritarian regimes.”2 Color revolutions and mass protest movements of the 2000s and the early 2010s (The Orange Revolution (2004) and Euromaidan (2014) in Ukraine, the Arab spring (2010–2012), protests against electoral fraud in Iran (2009) and Russia (2011–2013) etc.), during which social media played an important mobilizing function, were seen by many scholars as obvious evidence in support of this optimistic point of view.3 However, at the beginning of the 2000s, more skeptical opinions become widespread, claiming that authoritarian regimes are capable of not only meeting new technological challenges, but also using new communication technologies to strengthen their own power and obtain more control over society.4 These viewpoints were supported by many examples of nondemocratic countries, whose authorities managed to block unwanted Internet sites or even learned to use modern technology for their internal5 and foreign policy goals.6 However, it seems that the impact of the Internet and the ITC on politics in nondemocratic countries is far more complex.7 We need to take into account various aspects of this influence, its multi-vector and multi-level nature. The research on the impact of Internet-mediated communication on political communication in the nondemocratic or authoritarian context is mostly focused on the following three aspects: 1) use of the Internet and social media to organize opposition protests; 2) use of the new ICT by nondemocratic regimes to control their societies; 3) attempts of nondemocratic regimes to influence political processes and political decision-making in democratic countries. Still, a very important aspect of political communication is left out of sight, namely the fact that, even in an authoritarian context, the ruling elites may require a communicative platform for external and internal communication. Although this need is hard to satisfy through the official public sphere and traditional media, a new informal platform of communication could be of great help. Telegram is one of such new messaging services frequently used for informal political communication in several countries today. The role of Telegram as a means of political communication has not been studied well, probably due to its low popularity in developed democracies. Nevertheless, thanks to its technical characteristics, as well as to its established image (as a safe means of communication uncontrolled by the state), this messenger has gained notoriety, especially in nondemocracies or not fully democratic countries (as evidenced by its popularity in such countries as Russia, Iran, Uzbekistan, Brazil). Unfortunately, while there are relatively many studies on other social media in the nondemocratic context8, there is little research devoted to the role of Telegram as a means of political communication (a rare exception, for instance, is Azadeh Akbari and Rashid Gabdulhakov’s9 article “Platform Surveillance and Resistance in Iran and Russia: The Case of Telegram”). This paper attempts to fill the gap and examine the use of Telegram by the Russian ruling elite as a channel of political communication.

The peculiar phenomenon of Telegram appeared in the Russian public discourse in the middle of the 2010s. Telegram channels created a new media environment, strongly critical and politicized, which quickly began to gain popularity among Russians. Along with traditional media and mainstream social networks (in Russia, primarily VKontakte, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Odnoklassniki), Telegram started to have a tangible impact on the sociopolitical agenda and on the formation of public opinion. This led to the ambiguous relations between Telegram and the Russian authorities. On the one hand, Telegram is officially outlawed in Russia, and Roskomnadzor (the Russian Federal Supervision Agency for Information Technologies and Communications) has been trying to block its operation since April 2018. On the other hand, prior to the formal decision to block Telegram in Russia, many press services of various government departments had been using Telegram channels as a convenient and effective means of communicating their official position to the general public. As soon as Roskomnadzor started restricting access to Telegram, all official channels owned by government agencies were forced to close. Nevertheless, not only did the Russian authorities continue to monitor the main Telegram channels (including high-ranking government officials from the presidential apparatus of the Russian Federation), but they also unofficially control several news and political channels or pay for the publication of materials on independent channels. In this regard, the questions to ask would be: what is the reason for this dual attitude to Telegram by the Russian authorities? What makes it so attractive for representatives of the Russian establishment? How do they try to use Telegram and meanwhile bring it under control? What are the prospects of Telegram in Russia as a channel of political communication? In attempting to answer these questions, the main goal of this study is to find out what role Telegram plays today in the political communication of the Russian political elite.

The theoretical framework of this article is based on the paradigm of cyber realism, according to which the Internet “is an extraordinary communications tool that provides a range of new opportunities for people, communities, businesses, and government,”10 but “for every empowering or enlightening aspect of the wired life, there will also be dimensions that are malicious, perverse, or rather ordinary.”11 In a political context, this means that “the same technologies which give voice to democratic activists living under authoritarian rule can also be harnessed by their oppressors.”12 The research is also built on the thesis that modern undemocratic regimes have quite successfully (at least in the short term) learned to solve the “dictator’s dilemma” (with regard to Internet technologies and the risks to the regime that they bring with them),13 skillfully combining various ways of dealing with the modern ICT: from blocking the online platforms most dangerous to its power to various uses of these technologies to influence the public opinion and strengthen control over their countries. In addition, I proceed from the assumption that today, the Internet and social media provide an important channel of communication not only in democracies, but also in nondemocratic countries, whose ruling elites also need both external (reaching out to the society) and internal (between different elite groups) communication, but under the conditions of authoritarian or hybrid regimes, they cannot always achieve these goals. In democratic countries, this communication takes place mainly through open discussions in the public sphere.14 The citizens have the opportunity to convey their opinions to the authorities, and the ruling political elite can clearly monitor the public mood. In nondemocratic countries, public debate, open discussions between the government and the people, and dialogue between various groups of the political elite are largely difficult and sometimes not secure. However, the very need for such communication persists – it plays the role of “social glue,” sticking together various social groups into a single whole. Since it is completely impossible to fulfill this need within the framework of an authoritarian public sphere, the communicative activity begins to shift toward semi-public or partially public spaces, turning to other channels, forms, and ways of communication. In this study, we will consider the case of the use of the Telegram messenger platform by Russia’s ruling elite as an example of such kind of channels.

In the first part, I summarize a brief history of the emergence and transformation of Telegram into one of the most popular messengers in Russia and consider the reasons for its wide popularity, including its attractiveness for a politically active public. Next, I explore the political segment of Telegram channels, their audience, and influence on the public opinion. In the second part, I analyze the level of penetration and the use of political Telegram channels by the Russian authorities and different groups within the Russian establishment. Finally, I summarize all research results in the Conclusions and Discussion part of the paper and outline the issues that need to be clarified in further research on the political role of Telegram in Russia.

1. The Phenomenon of Telegram in Russia

Telegram first appeared in 2013 in Russia. It was launched by the brothers Nikolai and Pavel Durov, the founders of VKontakte, one of the largest and most popular social networking sites (SNS) in Russia and countries of the former USSR. From the very beginning, Telegram positioned itself as a reliable and secure means of communication, guaranteeing confidentiality to its customers, protecting them from the excessive curiosity of the security forces – a feature which was in high demand in Russia, as well as in some other non-democratic countries (Saudi Arabia, Iran, UAE, Uzbekistan, Belarus). Until late 2015, Telegram was a little-known message service used mainly by advanced Internet users who were concerned about the confidentiality of their communications. They used Telegram because it provided them with a high level of security (at that time only Telegram had protected end-2-end-encryption with self-deleting messages, which at the time was not the case with the more popular message applications in Russia – WhatsApp and Viber). In September 2015, channels appeared in Telegram – chat rooms that represent something between a news feed and a blog on a specific topic. A distinctive feature of Telegram channels, compared with chats in other instant messengers, is the opportunity for the channel’s author to share content with an unlimited circle of readers while maintaining their anonymity. Moreover, channels do not provide any feedback, subscribers cannot comment and rate the posts. The only criterion of a channel’s popularity is the number of subscribers, and the main form of feedback between authors and readers is users either subscribing or unsubscribing from the channel.

In 2016, these channels confidently gained popularity, and beginning with late 2016, when the number of subscribers to individual channels began to reach several thousands, Telegram became a significant platform for broadcasting various kinds of information, from rumors and outright speculations to completely reliable insider information, compromising materials, and leaks.15 From this point on, Telegram channels started to attract the interest of the Russian authorities, which only intensified after individual channels began to reach several tens of thousands of subscribers and the major media outlets began to use them as sources. Telegram’s popularity was not affected even by its official ban and attempts to block it.16 At the end of 2018, according to Telegram Analytics, there were about 63 000 channels identifying themselves as Russian.17 In 2018, a total of almost 40 000 new Russian-language channels appeared.18 Thus, despite the official ban, Telegram not only continues to work in Russia without significant problems, but even continues to grow and remains one of the most popular message services in Russia.

One of the important features of Telegram is its audience, which has a certain specificity that distinguishes it from the audience of the other two most popular messaging services in Russia – WhatsApp and Viber. In the second half of the 2010s, Telegram channels began attracting a specific audience of media content consumers largely focused on the constant consumption of information in an easily accessible and concise form. This way to deliver content is especially in demand among young people, and given the increasing politicization of this group, which became apparent from the 2011–2013 protests, it is quite understandable why Telegram and its channels have become a peculiar phenomenon in the Russian sociopolitical life of the 2010s. In absolute figures, the audience of Telegram channels is not very large – about 3.4 million daily users at the end of 2018. For comparison, WhatsApp has a daily audience in Russia of about 16.4 million, Viber – 9.3 million (All data for October 201819). An approximate profile of a Telegram user can be described based on a study conducted by the Telegram analytical service TGStat.ru in April 2019, in which more than 82 000 subscribers and authors of diverse channels were surveyed.20 According to this research, Russians aged 18–24 (27%) and aged 25–34 (38%) made up the two largest shares of Telegram users. Thus, Telegram is primarily popular among people from 18 to 34 years of age, the population group which the Russian authorities are actively trying to influence. By occupation, this group consists of students or young professionals with university degrees. According to the data of sociological studies, they form the most protest-minded group in Russia, who are unsatisfied with much of the country’s policy and who see no prospects for themselves under the current regime.21 In addition to young people, Telegram is also popular among another important population group, namely the middle-aged, well-educated citizens with higher-than-average incomes.22 Among them are many intellectuals, journalists, managers of advertising and PR agencies, IT specialists, and officials who play a key role in shaping public opinion.23 Most users are from Moscow (35.9%) and St. Petersburg (14.4%) – the cities where the most mass protests took place. In other words, Telegram’s audience is politicized, active, young, and educated. Many of them consciously use Telegram as an alternative source of information and for secure communication on political topics (which is relevant, given the periodic administrative and criminal prosecution for likes and reposts in Russia). This does not mean that Telegram’s audience is mostly oppositional; Telegram is often used by otherwise loyal authorities and those who cannot openly make critical remarks even in cases of a serious disagreement with the official policy of the ruling regime, because it would automatically threaten their career and well-being. Thus, for the Russian ruling elite, Telegram is a resource that allows them to reach a difficult but very important part of the population, which is almost impossible to achieve with the help of traditional media.

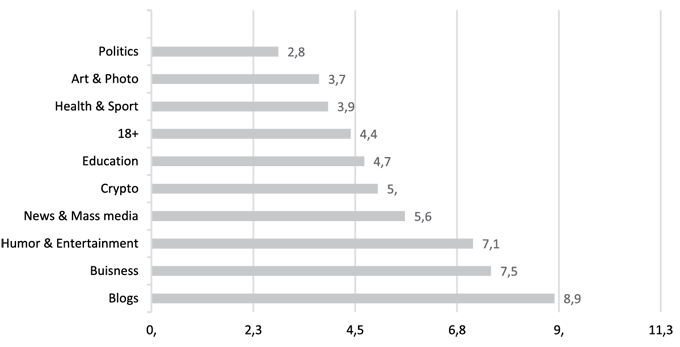

Political and news channels largely constitute the most original content of Telegram and occupy a central position among Telegram channels, even if their share has decreased significantly over the past few years. In recent years, the topics of Telegram channels have become considerably more diverse, and a significant part of them today are personal blogs, channels devoted to business and start-ups, humor, leisure, and entertainment (see Appendix 3: Telegram channels by topic). However, political and news channels (the content of which largely consists of political news and which mostly function as political channels) have the largest number of subscribers, especially considering the number of views and the citation index. Taking into account the average number of views per Telegram post, based on the results for the entire year 2018, political channels occupy almost the entire top ten of the most popular Telegram channels (see Rating of the top 30 channels from Medialogia24). The number of subscribers may contain a large percentage of bots or inactive users; however, the number of views and the citation index show that political and news channels occupy the leading positions among the Telegram channels. This indicates the activity, involvement, and interest of the audience of Telegram’s political segment. It also means that active users read political channels and news channels with mostly political content on purpose.

However, perhaps the main evidence that Telegram channels have become one of the main sources of information and an alternative to the traditional media in Russia today is not the size of the audience or even the viewing statistics, but the fact that many large media outlets (both traditional and new) and SNS actively refer to information obtained via Telegram channels (See Appendices 1 and 2). The media which refer to posts in Telegram channels are mostly either oppositional or critical of the ruling authorities in Russia (for instance, Echo Moskvy, Medusa, Novaya Gazeta). Nezavisimaya Gazeta has even a special weekly review of Telegram channels, which essentially represents a digest of the most interesting publications in Telegram about political events in the Russian regions. However, publications in Telegram channels are referred to not only by opposition and the liberal media, but also by relatively neutral and even pro-governmental ones (for example, by Rossiyskaya Gazeta, RIA Novosti, TASS). Telegram channels are playing an increasingly important role for the larger media, as they act as a source of content, follow political topics relevant to society, and give an understanding of the mood of key audiences. The anonymity of the Telegram channels seriously complicates administrative and/or criminal prosecution against their authors,25 which allows anonymous bloggers to express their opinions on burning issues more openly and receive feedback in the form of further subscriptions to the channel.26 All this makes Telegram an important source of influence on public opinion, for which and within which there is a serious struggle going on between different influence groups.

2. The Expansion of the Russian Ruling Elite into Telegram

The Russian ruling elite started to realize the importance of Telegram as an information environment in 2016, the year in which Telegram channels boomed in Russia and it became hard not to notice their influence on public opinion. Up to this point, Telegram had attracted scant attention from the Russian authorities besides the security services, since secret chats had been often used by oppositionists, radicals, and terrorists to coordinate and conduct their actions. In addition, the establishment was concerned with the appearance of leaks in the channels, which clearly indicated that information in some cases was coming from well-informed insiders. The lack of control over these channels caused serious concerns in the Kremlin. According to a study conducted by Project, this was further complicated by the fact that the team of Sergei Kiriyenko, who had become the first deputy chief of staff of the Russian Presidential Administration in October 2016, was tasked with planning and preparing for the 2018 presidential elections, and any leakage of unwanted information27 to the press and social media could make this task more difficult.28 After the 2011–2013 protests, the Kremlin started to carefully monitor the public mood on the Internet and sought to take control of SNS, which, apparently, completely succeeded with the most popular Russian SNS – Vkontakte and Odnoklassniki.29 However, at that time Telegram remained terra incognita for the Russian authorities. Reading anonymous Telegram channels coming into vogue caused them serious concern because they had not yet learned to work within the informational environment.30 In the meantime, Telegram channels were gaining dozens and then hundreds of thousands of subscribers. Aware of the growing popularity and influence of Telegram channels, the Russian establishment began its expansion into the messaging media environment. It was carried out in different ways and on different levels of the Russian establishment. First of all, the press services of many state departments started to monitor the most popular political channels and include the most significant content in the press digests for their heads. The fact that this practice exists even within the highest echelons of the Russian authorities is evidenced by the statements of Dmitry Peskov, the head of the presidential press service. According to him, the presidential press service tracks publications in the most well-known social and political channels of Telegram and prepares a special digest of the most significant content for Vladimir Putin.31 Moreover, before making an official decision on blocking Telegram, Putin’s press secretary used his own Telegram channel to hold conference calls, where he answered journalists’ questions.

However, the Russian authorities moved beyond the monitoring of Telegram channels, and in 2016 and 2017 several federal and regional agencies began to use it as a communication channel. By this time, many Russian federal and regional government agencies had started their own official Telegram channels. For instance, from 2016 to the blocking of Telegram in April 2018, the Russian Foreign Ministry, the Press Service of the President of Russia, the Investigative Committee, and the United Russia political party had created and used their own Telegram channels. News would sometimes break on the Telegram channels of these departments earlier than on their official sites. As a result, posts in Telegram channels became the main information source for the media. However, after the official decision to block Telegram, departmental channels were instructed to stop using it. As a result, most of the state Telegram channels, such as Vesti, TASS, and RIA Novosti, exist no longer or are no longer updated. However, the Telegram channels of many members of the Russian establishment continue to function — such as the channels of Head of the Chechen Republic Ramzan Kadyrov, Russia Today’s editor-in-chief Margarita Simonyan, the Liberal Democratic Party leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky, and the well-known pro-Putin TV host and one of the leading Russian propagandists Vladimir Solovyov.

Another, and perhaps more common, way the authorities use Telegram channels has been the unofficial funding of individual anonymous channels, or payment for certain publications in the most popular political channels. According to the independent media resource Project, which investigated the Kremlin’s influence on anonymous Telegram channels, the administration of the President had allocated a budget for expansion into Telegram at the end of 2016.32 According to the Project investigation, the Kremlin did not create its own channels, but hired contractors to spread the “right” kind of information through popular existing channels. For example, Kremlin contractors were former members of the Nashi (“Ours”) movement, including the former press secretary of this organization, Christina Potupchik.33 Under her leadership, entire networks, including groups of channels, started appearing and writing the “right” posts and reposting each other. This group included such channels as Akitilop, Ortega, and Polnyj P. The channels 338 and Media Technologist are said to be also connected to former members of Nashi.34

According to Project, many large Telegram channels represent, in one way or another, the interests of certain Kremlin influence groups.35 For example, Igor Sechin and the state corporation Rosneft are said to be backing the channel Karaulny. Nezygar channel is associated with the curator of Kremlin’s information policy Alexey Gromov. Mash and Boilernaya channels are said to relate to the Kovalchuk brothers, old friends and business partners of Vladimir Putin.36 Apparently, some political groups and security forces use Telegram channels to fight their rivals (leaking confidential information, mudslinging), and to promote their own position and political agenda. So, for example, in mid-November 2018, the channels controlled (according to unofficial sources) by the former spokesman for Putin and Medvedev, now Kremlin curator of information policy Alexey Gromov,37 “The Man Behind the Kremlin’s Control of the Russian Media,”38 disseminated information that Andrey Yarin39 (a subordinate to the Kremlin’s “systemic liberal” and curator of the internal policy Sergey Kiriyenko40) had been reprimanded by the leadership for incompetent performance and poor results in the regional elections. An answer came back immediately. The channels affiliated with the Kremlin’s internal political bloc and the Kovalchuks Kremlin clan (supporting Kiriyenko) – Bojlernaja, Mediatehnolog, IA Steklomoj, and Karaulnyj – reported that Yarin has no problems and that there could be no problems in principle.41 How can these information leaks in Telegram be interpreted, and who benefits from throwing a scandalous topic into the public sphere? The main target of the mudslinging apparently was not Andrey Yarin, a little-known and less powerful official, but Sergey Kiriyenko, his boss. Kiriyenko and Gromov are colleagues, they occupy similar and equal positions in the presidential administration, but they cannot be called allies, because they belong to different power groups and are fighting over spheres of influence. So, the cause of the alleged conflict between Gromov and Kiriyenko-Kovalchuk could be a struggle for influence in the media sphere: in the presidential administration, Gromov oversees traditional media (newspapers, TV), while Kiriyenko’s area of responsibility is digital media, the Internet, and social media. The Kovalchuk clan controls a number of large Russian media: for instance, in the media holding “National Media Group,” which includes the shares of REN TV, Pervyj kanal (Channel One Russia), Pjatyj kanal (Channel Five Russia), STS, Izvestia newspaper, and other media, a substantial part of the shares are owned directly by Yuri Kovalchuk. This example shows that it is wrong to consider the ruling elite as homogeneous. The members of the ruling elite are far from having the same interests and they can have very different points of view on many issues, including those different from the official position of the Kremlin. However, with the power vertical and an extremely clear “friend or foe” behavioral pattern, different wings in the ruling elite cannot openly express their opinions and discuss their differences and disagreements: they must show unity in the face of the ruling power. Therefore, they are bound to use some other communication channels, and Telegram is ideal for this. These separate groups, or clans, are also fighting to control the information field, as evidenced by the words of the editor-in-chief of one of the most popular near-political Telegram channels, Kremlevskij Mamkoved (@kremlin_mother_expert), who claims that there is a political order issued by the Kremlin to control the information realm.42 According to this popular blogger, about half of the political Telegram channels have been doing the Kremlin’s bidding, rotating between “honest” posts based on more or less reliable facts presented from their own political standpoint to paid progovernment posts.43

The corruptibility of Telegram channels has been confirmed by the Project study, during which a researcher offered money to the owners of a few popular political channels to post information he would feed them. It turned out that a significant number of the political channels were ready to publish almost any information, only the prices had differed.44 It is possible not only to buy the publication of certain information, but to also block publications on a specific topic, such as criticism of the authorities. In this sense, the Russian ruling elite can be quite satisfied with the current state of Telegram channels, since they lack solid principles and can be manipulated for money, which the Russian establishment can easily afford. In the opinion of the Project research group, the presidential elections showed an unexpected loyalty from many usually not-so-loyal Russian Telegram channels. Most of these channels wrote quite positively about the elections. Such loyalty, the researchers believe, was, most likely, not accidental, but the result of pro-Kremlin forces meddling with those Telegram channels.45

One of the programs of the progovernment, but officially independent, non-profit “Institute for Internet Development” (“Institut razvitija interneta,” IRI), which, according to the RBC agency, has been training regional authorities to work with social media, including Telegram, since February 2019, indicates that the authorities have been using Telegram even if it is officially banned in Russia. As a part of this program, regional elites have learned how to start and develop anonymous Telegram channels. Such projects to train regional managers to work with Telegram show that the Kremlin is fully aware of the importance of this medium of political communication and has been trying to seize the initiative in its use from non-state actors. As a result, the teams of many regional managers now include specialists responsible for social media who monitor the main federal and regional political channels and maintain at least one anonymous Telegram channel. Currently, regional governors allocate special funding for work with social media, and they support loyal media both directly and indirectly.46 Perhaps that is why Telegram, despite blocking attempts, has still been working consistently in Russia. The cause of the conflict between Telegram and the Russian authorities seems not to be the intention of the latter to completely stop its operation in the country but rather to control it.

Conclusions and Discussion

This study has shown that Telegram and its channels are an important means of political communication, which are actively and diversely used by the Russian establishment and political interest groups. First, Telegram is used as an information channel for presenting official viewpoints (many officials have their own channels, including the Press Secretary for the President of Russia Dmitry Peskov, or Head of the Chechen Republic Ramzan Kadyrov). Second, the Russian authorities use Telegram as a source of information about the public mood, about opposition activists, and to monitor various kinds of political activity on the Internet, including the organization of protest movements and demonstrations. Third, Telegram is considered by the political elite of Russia as an effective means of influencing public opinion by manipulating news feeds and news bias, leaking information, creating fake news, and throwing dirt; presenting pro-governmental points of view to a wider audience; and reaching out to some difficult, but very important parts of Russian population – young, well-educated, and political active urban dwellers. Fourth, Telegram channels are used by the Russian political elite to eliminate external and internal political rivals by publishing compromising materials or rumors and for horizontal communication between different power groups. Fifth, Telegram is used as a channel of vertical communication within the political elite itself, which is of particular importance in the power vertical and, given the lack of feedback, between higher and lower layers of the ruling political elite. All these ways of using Telegram by the Russian political elite testify to its important function as a secure and effective channel of communication, the need for which only increases with the tightening of the regime. This means that Telegram and its channels will retain their significant role as a crucial means of political communication in the coming years.

Even though the conclusions made in this article are based on the consolidation, summary, and analysis of all available open-source information on the use of Telegram by the Russian ruling elite, they remain largely hypothetical and require further theoretical and empirical research. First of all, we would need an empirical verification for the thesis that Telegram is used by various groups of the ruling elite as a channel for exchanging signals with each other. This requires a coherent analysis of content on Telegram channels, an analysis of connections between different channels (via reposts, references, etc.), and the identification, based on this analysis, of groups of channels connected by a common strategy and finding out whose elite group interests these channels represent. The thesis concerning the influence of information disseminated in Telegram on the public opinion in Russia also needs empirical verification. In order to meet this goal, it would be necessary to analyze the cases when publications in Telegram channels sparked off public debate in the Russian public sphere, as well as to evaluate the significance of these discussions for the formation of public opinion in the country.

References

Aday S., Farrell H., Lynch M., Sides J., Kelly J., & Zuckerman E., “Blogs and Bullets: New Media in Contentious Politics,” Peaceworks 65, 2010, United States Institute of Peace, p. 1–36, <https://doi.org/10.1163/2210-7975_hrd-0131-0103>.

Akbari A., Gabdulhakov R., “Platform Surveillance and Resistance in Iran and Russia: The Case of Telegram,” Surveillance & Society 17 (1/2), 2019, p. 223–231, <https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v17i1/2.12928>.

Astrom J., “Digital Democracy: Ideas, Intentions and Initiatives in Swedish Local Governments”, in: Gibson R., Römelle X., Ward S. (eds.), Electronic Democracy: Mobilisation, Organization and Participation Via New ICTs, London, UK: Routledge, 2004, <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203357989>.

“Auditorija zablokirovannogo Telegram priblizilas’ k rekordnym pokazateljam” [The banned Telegram’s audience about to set a record]. Available at: <https://www.rbc.ru/technology_and_media/14/12/2018/5c13a59c9a7947585724bcd6> (accessed 28 June 2019).

Bulovsky A., “Authoritarian Communication on Social Media: The Relationship between Democracy and Leaders’ Digital Communicative Practices,” International Communication Gazette 81 (1), 2018, p. 20–45, <https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048518767798>.

Churakova O., Muchametshina E., Sergina E., “V Kremle i FSB zanjalisʼ monitoringom telegram-kanalov. Messendzher stal «sistemoj privetov» odnih grupp vlijanija drugim” [Kremlin and FSB turn hand to monitoring Telegram channels. The messenger has become the “signalling system” of some influence groups to others]. Available at: <https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/articles/2017/09/24/735092-kremle-fsb-telegram-kanalov> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Cook S., “China’s growing Army of Paid Internet Commentators,” Freedom at Issue (October 10), 2011.

Deibert R., “Cyberspace under Siege”, Journal of Democracy 26 (3), 2015, p. 64–78, <https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2015.0051>.

Deibert R., Rohozinski R., “Beyond Denial: Introducing Next Generation Access Controls”, in: Deibert R. et al., eds., Access Controlled: The Shaping of Power, Rights, and Rule in Cyberspace, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2010, p. 3–13.

Deibert R., Rohozinski R., “Liberation vs. Control: The Future of Cyberspace,” Journal of Democracy 21, 2010, p. 43–57.

Diamond L., “Liberation Technology,” Journal of Democracy 22 (3), 2010, p. 69–83.

“Doklad «Novaja protestnaja volna: mify i realʼnostʼ»” [Report “New Protest Wave: Myths and Reality”]. Available at: <http://civilfund.ru/mat/view/37> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Ferdinand P.,ed., The Internet, Democracy and Democratization, London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2000.

Gore A., “Forging a New Athenian Age of Democracy,” Intermedia 22 (2), 1995, p. 4–6.

Göbel C., “The Information Dilemma: How ICT strengthen or weaken Authoritarian Rule,” Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift 115 (4), 2013, p. 385–402

Hacker K., van Dijk J., What is Digital Democracy? Digital Democracy: Issues of Theory and Practice, London, UK: SAGE, 2000.

Han R., “Manufacturing Consent in Cyberspace: China’s ‘Fifty-cent Army’”, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 2, 2015, p. 105–134, <https://doi.org/10.1177/186810261504400205>.

Hakim D., “Once Celebrated in Russia, the Programmer Pavel Durov Chooses Exile”. Available at: <https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/03/technology/once-celebrated-in-russia-programmer-pavel-durov-chooses-exile.html> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Hussain M. M., Howard P. N., State Power 2.0: Authoritarian Entrenchment and Political Engagement Worldwide, Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2014.

“Issledovanie auditorii Telegram 2019” [Telegram audience research 2019]. Available at: <https://tgstat.ru/research> (accessed 8 June 2019).

“Itogi 2018 goda dlja Telegram v cifrah” [Telegram 2018 results in numbers]. Available at: <https://tgstat.ru/articles/Itogi-2018-goda-dlya-Telegram-v-cifrah-12-29> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Kalathil S., Boas T. C., “The Internet and State Control in Authoritarian Regimes: China, Cuba, and the Counterrevolution,” First Monday 6 (8), 2001, <https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v6i8.876>.

Kalathil S., Boas T. C., Open Networks, Closed Regimes: The Impact of the Internet on Authoritarian Rule, Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment, 2003.

Khlebnikov V., „Ministerstvo trollinga: kak komanda alikhanova voyuet v internete“ [The Ministry of Trolling: how Alikhanov’s team fights on the Internet]. Available at: <https://www.newkaliningrad.ru/news/politics/20351854-ministerstvo-trollinga-kak-komanda-alikhanova-voyuet-v-internete.html> (accessed 8 June 2019).

King G., Pan J., Roberts M. E., “How the Chinese Government fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, not Engaged Argument,” American Political Science Review 111 (3), 2017, p. 484–501, <https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055417000144>.

Lim M., “Clicks, Cabs, and Coffee Houses: Social Media and Oppositional Movements in Egypt, 2004–2011,” Journal of Communication 62, 2012, p. 231–248, <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01628.x>.

Mackinnon R., “China’s “Networked Authoritarianism”, Journal of Democracy 22 (2), 2011, p. 32–46.

Maréchal N., “Networked Authoritarianism and the Geopolitics of Information: Understanding Russian Internet Policy,” Media and Communication 5 (1), 2017, p. 29–41, <https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v5i1.808>.

„Messendzher razryvaet ot kolichestva informatsii. Intervju glavreda telegram kanala Kremlevskij mamkoved” [The messenger is suffering from information explosion. Interview with the chief editor of Telegram channel Kremlin mamkoved]. Available at: <https://360tv.ru/news/tekst/messendzher-razryvaet-ot-kolichestva-informatsii-intervju-glavreda-telegram-kanala-kremlevskij-mamkoved/> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Michaelsen M., Glasius M., “Authoritarian Practices in the Digital Age,” International Journal of Communication 12 (2018), p. 3788–3794.

“Molodezhnyj” protest: prichiny i potencial. Uslovija zhizni i mirooshhushhenie rossijskoj molodezhi. [“Youth” protest: causes and potential. Living conditions and view of life of the Russian youth]. Available at: <http://cepr.su/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Молодежный-протест_причины-и-потенциал.pdf> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Morozov E., The Net Delusion: How not to liberate the World. London, UK: Allen Lane, 2011.

Oreskovic A., “Egyptian Activist Creates Image Issue for Google,” Reuters, 12 Februar, 2011.

Pearce K., Kendzior S., “Networked Authoritarianism and Social Media in Azerbaijan,” Journal of Communication 62, 2012, p. 283–298, <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01633.x>.

“Peskov: novosti Telegram-kanalov popadajut v dajdzhest dlja Putina, esli togo stojat“ [Peskov: news from Telegram channels end up in digests for Putin, if they are worth it]. Available at: <https://tass.ru/politika/4866702> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Potupchik K., Zapreshhennyj» Telegram. Putevoditelʼ po samomu skandalʼnomu internet-messendzheru [The “forbidden” Telegram. A guide to the scandalous messenger], M.: Buki Vedi, 2019.

“Principles of Technorealism.” Available at: <http://www.technorealism.org> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 743 of July 31, 2014. [The “Rules of Cooperation for Honest Internet Service Providers”]. Available at: <https://rg.ru/2014/08/04/internet-dok.html> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Reuter O. J., Szakonyi D., “Online Social Media and Political Awareness in Authoritarian Regimes,” British Journal of Political Science, Cambridge University Press, vol. 45 (01), 2015, January, p. 29–51, <https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123413000203>.

Rød E. G., Weidmann N. B., “Empowering Activists or Autocrats? The Internet in Authoritarian Regimes,” Journal of Peace Research 52 (3), 2015, p. 338–351, <https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343314555782>.

Rubin M., Zholobova M., Badanin R., “Master of Puppets. The Man Behind the Kremlin’s Control of the Russian Media”. Available at: <https://www.proekt.media/portrait/alexey-gromov-eng/> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Rubin M., Badanin R., “Telega iz Kremlja. Rasskaz o tom, kak vlasti prevratili Telegram v televizor” [Telega (Telega is a colloquial name for Telegram and sounds like ‘cart’ in Russian – A.S.) from the Kremlin. A story about how the authorities turned Telegram into a TV set]. Available at: <https://www.proekt.media/narrative/telegram-kanaly/> (accessed 8 June 2019), <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-4197-4>.

Rutenberg J., “RT, Sputnik and Russia’s New Theory of War,” The New York Times Magazine, September 13, 2017.

Salikov A., “Hannah Arendt, Jürgen Habermas and rethinking the Public Sphere in the Age of Social Media,” Russian Sociological Review 17 (4), 2018, p. 88–102, <https://doi.org/10.17323/1728-192x-2018-4-88-102>.

Shane S., “The Fake Americans Russia Created to Influence the Election,” The New York Times, September 7, 2017.

Shirky C., “The Political Power of Social Media,” Foreign Affairs 90 (1), 2011, p. 28–41.

“Telegram-kanaly: 2018 god” [Telegram channels: 2018]. Available at: <https://www.mlg.ru/ratings/socmedia/telegram/6430/> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Toepfl F., “Making Sense of the News in a Hybrid Regime: How Young Russians Decode State TV and an Oppositional Blog,” Journal of Communication, April 2013, 63 (2), p. 244–265, <https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12018>.

Torres-Soriano M. R., “Internet as a Driver of Political Change: Cyber-pessimists and Cyber-optimists,” Journal of the Spanish Institute of Strategic Studies 1 (1), 2013, p. 1–22.

Tsagarousianou R., Tambini D., Bryan C., eds., Cyberdemocracy. Technology, Cities and Civic Networks, London/New York: Routledge, 1998.

“V Kremle monitorjat osnovnye Telegram-kanaly, no ne pereocenivajut ih” [The Kremlin monitors the main Telegram channels but does not overestimate their quality]. Available at: <https://tass.ru/obschestvo/4589758> (accessed 8 June 2019).

Weare Ch., “The Internet and Democracy: The Causal Links between Technology and Politics,” International Journal of Public Administration 25 (5), 2002, p. 659–691, <https://doi.org/10.1081/pad-120003294>.

White S., McAllister I., “Did Russia (nearly) have a Facebook Revolution in 2011? Social Media’s Challenge to Authoritarianism,” Political Studies Association 34 (1), 2014, p. 72–84, <https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.12037>.

Appendix 1. Top-10 most-cited Telegram Channels.

|

N |

Channel |

Times cited, (thousands) |

Content category |

|

1. |

Незыгарь (Nezygar) |

701,78 |

Politics |

|

2. |

Mash |

699,02 |

News & Mass media |

|

3. |

Футляр от виолончели (Futlyar ot violoncheli) |

649,47 |

Politics |

|

4. |

Караульный (Karaulny) |

636,85 |

Politics |

|

5. |

360tv |

542,07 |

News & Mass media |

|

6. |

Медиатехнолог (Mediatechnolog) |

448,93 |

Politics |

|

7. |

Бойлерная (Boilernaya) |

418,30 |

Politics |

|

8. |

avast |

394,87 |

Politics |

|

9. |

338 |

378,67 |

Politics |

|

10. |

RT на русском (RT in Russian) |

365,28 |

News & Mass media |

Data source: Tеlegram Analytics service, https://tgstat.ru.

Appendix 2. Top-10 most-cited Telegram Channels in the Russian Media.

|

N |

Channel |

Times cited |

Content Category |

|

N |

Channel |

Times cited |

Content Category |

|

1. |

Mash |

43 982 |

News & Mass media |

|

2. |

Kadyrov_95 |

8 347 |

Politics |

|

3. |

Незыгарь (Nezygar) |

7 697 |

Politics |

|

4. |

Life Shot |

7 212 |

News & Mass media |

|

5. |

Directorate 4 |

6 661 |

News & Mass media |

|

6. |

WarGonzo |

4 793 |

News & Mass media |

|

7. |

Мутко против (Mutko protiv) |

3 373 |

Health & Sport |

|

8. |

Super |

3 241 |

News & Mass media |

|

9. |

Павел Чиков (Pavel Chikov) |

2 410 |

Politics |

|

10. |

Владимир Жириновский (Vladimir Zhirinovsky) |

1 599 |

Politics |

Data source: 2018 rating by Medialogia.47

Appendix 3. Telegram channels in Russia by topic, % (as of December 2018).

Data source: Tеlegram Analytics service, https://tgstat.ru.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47