Politologija ISSN 1392-1681 eISSN 2424-6034

2022/1, vol. 105, pp. 8–52 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Polit.2022.105.1

The Impact of Significant

Events on Public Policy and Institutional Change: Towards

a Research Agenda*

Inga Patkauskaitė-Tiuchtienė

PhD student at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University

Email: inga.patkauskaite-tiuchtiene@tspmi.vu.lt

Rasa Bortkevičiūtė

PhD student at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University

Email: rasa.bortkeviciute@tspmi.vu.lt

Vitalis Nakrošis

Professor at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University

Email: vitalis.nakrosis@tspmi.vu.lt

Ramūnas Vilpišauskas

Professor at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University

Email: ramunas.vilpisauskas@tspmi.vu.lt

Abstract. Data shows that significant events, such natural disasters, anthropogenic disasters and malign activities by hostile actors, often having cross-border effects, have been on the rise. However, the studies of the effects of those events on public policies, governance and institutions remain inconclusive. In this article we present a research agenda that proposes the classification of the significant events on the basis of their characteristics, backing it with a newly compiled data set on significant events that took place in Lithuania in 2004–2020. It also offers three main pathways to change setting out causal mechanisms of how those events can affect policy and institutional change. We conclude with concrete proposals for further research that could provide both theoretically innovative and policy-relevant insights on crisis management and policy changes affecting welfare institutions and the resilience of society.

Keywords: crisis, focusing event, significant event, mapping, policy change, Lithuania.

Reikšmingų įvykių poveikis viešosios politikos ir institucijų kaitai: tyrimų darbotvarkė

Santrauka. Pastaruoju metu susiduriama su vis didėjančiu reikšmingų įvykių skaičiumi. Tokio pobūdžio įvykiai apima stichines, antropogenines nelaimes ir sąmoningus priešiškai nusiteikusių veikėjų veiksmus, o neretai pasižymi ir sektoriaus, valdymo srities ar valstybės ribas peržengiančiu poveikiu. Nepaisant to, išvados apie šių įvykių poveikį viešajai politikai, valdymui ir institucijoms – labai nevienodos. Šis straipsnis įvairiai papildo esamas akademines diskusijas, siūlydamas reikšmingų įvykių tyrimų darbotvarkę. Joje pateikiama tokio pobūdžio įvykių klasifikacija pagal jų charakteristikas, kuri empiriškai patikrinama remiantis naujai sudarytu duomenų apie 2004–2020 m. laikotarpiu Lietuvoje vykusius reikšmingus įvykius rinkiniu. Darbotvarkėje taip pat pasiūlomi trys pagrindiniai kaitos keliai, turintys savus priežastinių ryšių mechanizmus, galinčius atskleisti reikšmingų įvykių poveikį viešosios politikos, valdymo ir institucijų pokyčiams. Straipsnio išvadose išskiriami pasiūlymai ateities tyrimams, reikšmingi tiek dėl teorinių inovacijų, tiek dėl praktinio sprendimų priėmimo. Jų įgyvendinimas leistų paaiškinti krizių valdymą ir viešosios politikos pokyčius, darančius įtaką gerovės valstybės institucijų veikimui ir visuomenės atsparumui.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: krizė, sutelkiantis įvykis, reikšmingas įvykis, viešosios politikos pokyčiai, instituciniai pokyčiai, Lietuva.

__________

Received: 03/01/2022. Accepted: 15/03/2022

Copyright © 2022 Inga Patkauskaitė-Tiuchtienė, Rasa Bortkevičiūtė, Vitalis Nakrošis, Ramūnas Vilpišauskas. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Contemporary societies and governments are facing an increasing number of turbulent events, including crises, disasters, accidents, emergencies, fiascos, and catastrophes as well as their variations1. They cover episodes of various nature, ranging from natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes or outbreaks of diseases to anthropogenic disasters and incidents, such as plane crashes, cyber-attacks or forced migration2. These events pose a threat for the core norms and functions of governance systems3 and require urgent action under conditions of deep uncertainty4.

In addition, various crises, disasters and emergencies are frequently named as causes of policy or institutional changes. By drawing attention to a policy problem, these events illuminate failures of established policies or their implementation5, promote the formation of new policy alternatives or the reconsideration of policies that have been previously discussed but not implemented. Finally, they provide opportunities to learn and reduce vulnerability to similar risks in the future6, preventing a repeat of the crisis in this way.

The potential of significant events to increase the likelihood of policy changes within disaster-affected governments is also foreseen in the main theories of public policy process. For example, the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) refers to the relevance of an external shock or perturbation for policy change7; the Punctuated Equilibrium Theory (PET) stresses the impact of triggering events that help focus public, media and government attention to an issue8; and the Multiple Streams Framework (MSF) highlights focusing events that can attract attention to major public problems and open a window of opportunity to couple problem, policy and politics streams9. By linking the “divergent vocabulary”10 of research on crisis management and public policy process, we propose using the term “significant event”. It refers to events or situations that damage or threaten the fundamental values of society and (or) life-sustaining systems – social welfare, health, security, governance and (or) critical infrastructure – and requires rapid response and (or) decision-making by public authorities.

There is a common agreement that not every significant event has transformational potential to cause a policy, governance or institutional change11. While some of these events might lead towards various types of inaction12, some of them have a potential to focus attention of decision-makers and serve as precursors for policy change13. In other words, it is difficult to foresee whether an event will have a great deal of focal power. In addition, crises alone are not sufficient for policy change, but they can open a window of opportunity that otherwise would not be available14. However, the mechanisms behind this process remain largely unclear, with rather puzzling evidence on the role and impact of crises on developments of public policy and institutional change.

First, it was found that similar crises might lead towards different results in public policy change15. Second, despite the observed dominance of incremental policy responses in the aftermath of crises or disasters16, sometimes even small events can initiate major consequences, spanning different fields of public policy17. Third, while some evidence suggests that gradually accumulating events have a higher potential to open a window of opportunity18, ample evidence points to policy change after single, sudden-onset events19. Taken together, this suggests that there is no linear relation, and the characteristics of a significant event allow only a partial explanation of the reasons for subsequent change in public policy and its nature. While some researchers point to characteristics of the events to explain their focusing potential20, and others focus on the public policy process following the significant event21 that encourages or limits policy change, we point to the need to connect both approaches to fully understand causal pathways that lead to these outcomes.

Considering this gap in existing literature, the aim of this article is to clarify the interplay between the characteristics of a significant event and its context, dynamics in policy subsystems, as well as policy, governance and institutional change. We do this by suggesting three main pathways that link a significant event to policy, governance and institutional change. Based on the “big bang” approach, the first pathway leads to major and sudden policy change through mobilising the attention of the public, media, and political institutions. Our second pathway brings only incremental change through the interaction of advocacy coalitions in different public policy subsystems, in line with the metaphor of “muddling through”. Our third pathway to policy change is based on learning from policy implementation results, especially when decision-makers are confronted with similar recurring events.

We structure our argument by providing a research agenda built on an extensive literature review in the fields of crisis and disaster management as well as public policy process. As it highlights the need to thoroughly explore manifestations of alternative policy change pathways in practice, we also present results on the mapping of significant events in Lithuania from 2004 to 2020. During this period Lithuania encountered two economic crises, managed a growing number of emergency situations and events, as well as faced some other significant events. Their mapping reveals the distribution of significant events among various fields of public policy (i.e., it points to the occurrence of events of different magnitude and nature in a particular policy area)22 and thus highlights the most promising areas for further in-depth analysis through case studies.

The article proceeds with a detailed overview of factors from the policy process and crisis management literature, which could contribute to the explanation of policy, governance and institutional change caused by significant events. It also includes a brief discussion on the main pathways towards policy and institutional reform. A methodology of our empirical research is presented in the second part of the article, followed by the mapping of significant events in Lithuania from 2004 to 2020 in the third section. Finally, the concluding section summarises the main arguments of the article and proposes a way forward for researching the impact of significant events on different types of policy, institutional or governance change.

1. Research agenda

Thomas A. Birkland posits that extreme events attract attention to a certain public policy issue or problem and open a window of opportunity for the implementation of public policy change through group mobilisation and increased discussion of ideas23. Building on this explanation, three groups of variables determining the impact of significant events on policy change should be considered.

First, significant events have a different nature, which may have an impact on their role for public policy change. When the damage caused by the event is not only large-scale but also indisputable, easily visualised and concentrated geographically or within a certain community, it has a high focusing potential and thus, might serve as a stronger stimulus to act24. Second, numerous studies have shown that the amount and the content of media coverage afforded to a particular issue shape the public and politicians’ opinion towards a significant event25, which can, in turn, affect how resources are allocated and policies are developed around these issues26. However, the evidence is not unanimous: increased attention of the media and the public does not always lead to policy action27. This points to a need for a deeper analysis, treating political, media, and public attention as intermediary variables between significant events and subsequent public policy developments. Finally, activities of advocacy coalitions within public policy subsystems draw attention to existing public policy alternatives and might encourage policy change28. Nevertheless, this explanation lacks clarity on causal mechanisms, connecting the influencing factors with the actual policy change29.

1.1. Characteristics of significant events

Nature and proximity. The distinction is usually drawn between natural (caused by geographical and climatic forces) and anthropogenic or “man-made” (caused by malfunctioning of political-administrative systems or consciously hostile activities against the state) disasters30. In addition, these significant events might be marked with varying geographic and policy proximity in relation to policy subsystems. It is expected that more proximate events will highlight drawbacks of the current system and thus cause a greater mobilisation of resources, which may lead to an increased need for policy change31. However, due to the interdependence of governance systems, the impact of significant events is likely to “rapidly snowball through the global networks, jumping from one system to another”32.

Speed of development and duration. Crises that quickly scale up and terminate are labelled as “fast-burning crises”, while those with a gradual development might put a “long shadow” on the governance system. On the contrary, events with a slow build-up and fast termination are named as “cathartic”, while the ones with a slow termination are known as “slow-burning crises”33. These categories might serve as a useful analytic tool to explain more extraordinary measures taken in the face of sudden incidents and a rather incremental approach towards gradually developing crises34. In addition, there is an extensive debate on the potential impact of one-off crises and the accumulation of several turbulent events over time. It points out that the latter frequently leads towards experiential learning, which gradually changes the beliefs of decision-makers and can evoke policy change35.

Magnitude. The research focuses on the negative impact of the event36, including its harms (e.g., injuries, deaths, property damage) and scope (e.g., population of the area or the size of the group affected by the event)37. Usually, a linear explanation is drawn, claiming that the bigger (potential) damage caused by the event is, the greater attention it will attract and, in turn, the higher chances for the policy, governance or institutional changes are38. However, the objective measurement of damage might be complicated, as its perception is sensitive for the context (e.g., safer societies with lower risks exposure are more vulnerable to hazardous events)39 and might be strategically framed by political actors, depending on their willingness to protect the status quo or implement policy changes40. The public perception of an event and the positioning of policy actors associated with it can constrain or facilitate policy or institutional action by defining an urgency for change. The latter depends on the extent of a mismatch between the state of policy design and execution, on the one hand, and the needs and expectations of some policy stakeholders or affected target groups on the other.

1.2. Political, media, and public attention

Political attention. The distribution of limited political attention affects the decision-making process and the choice of public policy actions. To be precise, while political attention is focused on a particular public policy issue, other policy areas receive significantly less attention. Often, the problem does not come to the attention of decision-makers until unusually strong information signals reach them41. This might be caused by a high-magnitude event or a rapid accumulation of indicators42. Meanwhile, political attention puts the issue on the political agenda and ensures the allocation of time, financial and human resources that are necessary for changes in public policy to take place43. In addition, the sustainability of political attention plays a major role: research reveals that public policy subsystems, marked by a lack or lower stability of political attention, are characterised by less significant changes in public policy44.

Media attention. Greater media attention can lead to a growth of public interest and put pressure on decision-makers (hence, the media determines what is visible). In addition, the media can frame the problem, suggesting certain ways of thinking about the event and facilitating the implementation of public policy changes designed to address it (thus, it determines how specific events are perceived)45. As a result, the impact of a significant event might depend on intensity, substantiality and sustainability of attention paid for it in the media. These terms respectively refer to the comparative amount of attention in the media for the event, the narrative chosen (is it only about a particular event or broader public issues behind it) and the duration of attention devoted to the event46. Finally, the media can act both as an independent contributor to policy debates and a conduit for decision-makers narratives47 or, in other words, be used as a strategic political resource by advocacy coalitions48.

Public attention. Significant events attract an uneven amount of public attention. For example, minor, even though relatively frequent incidents might attract lower attention due to public trust in authorities’ capacity to deal with routine emergencies49. In turn, events that are marked with a visible harm for a society or its groups might increase the salience of an issue, related with a cause or the field of the significant event. Salience, which is a synonym for attention to an issue, covers the elements of importance for the society and problematic nature50. Although significant events can attract public interest and, in turn, put salient issues on the political agenda51, the window of opportunity for public policy change remains open for a rather short time: research points to a short-term effect of disasters on public opinion52.

1.3. Variables within a public policy subsystem

Activities of advocacy coalitions. ACF treats significant events as affecting the prospects for policy change. Their occurrence might pave the way for major changes in the coalition structure as well as in the distribution of resources in the public policy subsystem53. Resources include formal legal authority, public opinion, information, mobilizable supporters and skilful leadership, but they are not equivalent: research highlights that even resourceful coalitions fail to realise their beliefs without having decision-making power54. In addition, strategies employed by coalitions can also change the balance of power in the subsystem and pave the way for public policy change. For instance, coalitions might employ new policy venues, forming “convenience coalitions” to mobilise resources by collaborating with or attracting actors from other coalitions55, or strategically apply framing to persuade stakeholders about the problem, its causes, and the appropriateness of the public policy solutions to address them56. On the other hand, a great deal of competing frames on the event impedes the possibility of significant public policy changes57.

Leadership. Various public policy process theories associate political entrepreneurs with the same goal: to formulate favourable conditions for the implementation of the decisions they represent58. The activities of political actors who take leadership are linked with defining problems and offering an attractive vision, changing stakeholders’ beliefs on a particular public policy issue, making effective use of available resources, and attracting support for the transformative ideas they represent59. Some authors suggest that it is up to the efforts of the leaders how the political issue be perceived and whether it will be seen as relevant by the other stakeholders60. The role of leadership can be attributed to a wide range of actors, seeking to draw attention to their proposed public policy solution, including policymakers, civil servants, interest groups, experts and non-governmental organisations61.

Learning. Significant events reveal deficiencies in existing policy regimes, and can prompt learning about why they happened, what can be done to respond to them and prevent their recurrence62. Several overlapping concepts of (crisis-induced) learning permeate the policy literature, but they are usually related with crisis-triggered collection, processing and application of new knowledge in decision-making63. Research also draws a distinction between different types of learning, including political, instrumental and social, which significantly differ in terms of their content (more technical or substantial)64. Accordingly, they may have a varying impact on policy change, ranging from the first- or second-order change (adjustment of the public policy measures) to the third-order change or, in other words, a paradigm shift (a thorough review of causal links between policy aims and tools used to achieve them)65. In addition, learning might occur both after and during the crisis. In the latter case, learning opportunities may be limited by the need to act immediately under uncertainty and pressure66. Thus, learning is less likely to cause a change in the core beliefs, increasing the probability of a more incremental policy reform67. There are higher chances that learning will take place following an accumulation of crises68, when the definition of a problem is settled down and it is more difficult to dismiss these events as isolated ones69.

1.4. Pathways towards policy change

Despite some attempts to explain varying “postcrisis trajectories”70, the existing research rarely includes public policy process approach and in turn, provides only a limited explanation on the impact of crises on policymaking. Meanwhile, the policy process literature is typically focused on rather nuanced insights into the crises-policy change relationship71. Aiming for a more versatile explanation, we build on the logics of PET and ACF to link our variables (focused on characteristics of significant events, their context and interplay within a public policy subsystem) into coherent pathways that connect a significant event to policy, governance and institutional change.

Major, sudden policy change (the “big bang” approach). According to PET, a change in public policy occurs when external information signals are unusually strong, or their influence accumulates over time. Significant events, characterised by sudden appearance and high magnitude of (potential) damage immediately attract attention of public, media and policymakers. The growth of salience of the public policy issue in the society, taken together with an intensive, sustainable and problematic presentation of the respective event in the media sends a strong information signal to decision makers and helps the issue reach the political agenda. In addition, it opens a window of opportunity for public policy change that can be exploited by public policy entrepreneurs. However, the initial attention of the media and politicians allocated to the issue tends to be quite short-lived. Besides, it is more likely that major changes will happen straight after the event before the urgency vanes and opponents to further change begin to debate proposed solutions72. As a result, a rapid and fundamental change of public policy, governance or institutions is expected. It is described using the metaphor of the “big bang”.

Incremental change (the “muddling-through” approach). A vast body of research concludes that significant events cause incremental rather than large-scale changes in public policy, governance, or institutional structure73. Based on ideas of ACF, significant events might have an (in)direct impact on the distribution of resources and various strategies of advocacy coalitions. This can be even further fostered by a change of leadership that plays an important role in individual advocacy coalitions or in relationships between competing coalitions, with leaders acting as mediators to find an acceptable compromise. However, in case of this path of change, a gradual change in public policy, which is described by the metaphor of “muddling-through”, as the impetus for change is more likely to be suppressed or mitigated by various factors inherent in the usual public policy process74. Following this explanation, despite the nature, magnitude or duration of the events, public policy change will proceed at a usual pace, similar to the one in other public policy subsystems.

Policy learning. Learning from policy implementation results is one of the most important pathways to policy change75, while the crisis induced learning holds a promise of durable alterations in behaviour to improve the collective performance76. It is especially likely to take place in the face of similar recurring events, which allows for accumulation of knowledge about the functioning of specific policies or governance practices and justification of the need for their change77. However, learning process might also occur in the aftermath of a hazardous event, when the sudden emergence of new information causes members of the dominant coalition to reconsider their policy beliefs78. Hence, regardless of the features of the event, learning process can contribute to the proper identification of the causes of failure and, while collaborating with a wide range of stakeholders, lead towards policy, governance or institutional change to achieve better public policy outcomes. Nevertheless, the content and scope of the change can vary depending on the type of learning that motivates it79.

We suggest that while each of these pathways could be dominant in a particular situation, policy learning could also compliment the first two trajectories of change. Nevertheless, a thorough empirical analysis of the proposed mechanisms is necessary to find out their interplay and actual manifestation, which would allow for even more precise identification of the causal mechanisms driving policy change.

2. Methodology

Nohrstedt and Weible point to a common confirmation bias when the policy change is falsely attributed as a consequence of a selected significant event80. To minimize this risk, we begin our analysis with an extensive mapping of significant events which took place in Lithuania from 2004 to 2020. Focusing on their characteristics (in particular, magnitude and nature as indicated in section 1.1.), we compile a new original dataset, which reveals the distribution of significant events among various fields of public policy. This, in turn, allows us to indicate policy areas for the further selection of cases for an in-depth analysis while using process tracing and other relevant methodologies (i.e., issue framing by the media). The time period chosen for the study is related to the date of Lithuania’s accession to the EU, as until then the main agenda driving public policy and governance reforms was considered to be the EU agenda and the requirements related to accession81.

The mapping of events is based on the review of primary and secondary sources. The annual reports of the Fire and Rescue Department under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania on the state of the civil system in Lithuania, the additional data provided by the Fire and Rescue Department on emergency events and emergencies in Lithuania, the annual reports of the National Electronic Communications Networks and Information Security Incident Response Team of the Communications Regulatory Authority of the Republic of Lithuania (CERT-LT), the annual national cyber security status reports of the National Cyber Security Centre under the Ministry of National Defense in Lithuania, as well as the data provided by the news agency BNS on the most important political and public life events in Lithuania every year was used as the main sources for collecting data on significant events in Lithuania during the period of 2004–2020.

3. Empirical research

As mentioned in section 1.1, the key characteristics of significant events that may affect their focusing potential and (or) the extent of impetus for public policy and (or) institutional change are the following: the nature of a significant event, the magnitude of the event and the speed of its development and duration. Each country has its own accumulated historical experience of significant events as well as the most inherent threats or risks, due to geographical location, the mix of topography and climate, the nature of national industry, transport and other economic activities or other factors82. Therefore, there is no one-size-fits-all typology for classification of significant events that could be applicable to each country or context. Taking this into account, in order to provide the mapping of significant events in Lithuania from 2004 to 2020 and to reveal the most significant cases for further analysis, we adapted the typologies of significant events presented in the scientific literature to the Lithuanian context.

Thus, based on the national legislation currently in force and considering the specificities of significant events in the country, we divided these events into two main categories depending on their nature – natural disasters and anthropogenic disasters and incidents – and three main categories depending on their magnitude – low-impact/low-threat, medium-impact/medium-threat and high-impact/high-threat events. Natural disasters include all events caused by geographical and climatic forces (i.e., geological and hydrometeorological events; communicable diseases in humans, other acute disorders of human health; and animal and plant diseases, insect infestations and outbreaks of agricultural diseases in the soil), whereas anthropogenic disasters and incidents – various types of events caused by malfunctioning of social-technical and (or) political-administrative systems (i.e., ecological, technological, social disasters, economic downturns, political scandals), as well as consciously hostile activities against the state inside or outside the country (i.e., cyber-attacks).

Significant events of low-impact/low-threat include emergency events. According to the Law on Civil Protection of the Republic of Lithuania, these events are defined as events of natural, technical, ecological or social character which have reached or exceeded the established criteria and pose a hazard to the life or health of residents, the social conditions of their life, property and/or the environment83. In Lithuania, emergency events meet the following criteria: people were injured (killed, poisoned, etc.); the life, health, property and/or environment of at least 100 people were endangered; the social conditions of the population were disrupted (e.g., road, rail, air or water traffic was interrupted for a sufficiently long time); environmental damage has been caused (e.g., to forests, water bodies, air, the earth’s surface and/or its deeper layers); immovable cultural property or objects of state importance or state security were endangered84.

Significant events of medium-impact/medium-threat include municipal-level emergencies as well as events that have an impact at the level of organisations or groups of organisations, whereas significant events of high-impact/high-threat are state-level emergencies and crises. In accordance with the aforementioned Law on Civil Protection, emergencies are defined as the situations resulting from an emergency event that could cause a sudden and serious threat to the life or health of the population, property, the environment or the death, injury or other damage to the population. When the duration of an emergency is no longer than 6 months and the limits of the spread of its effects do not exceed the boundaries of the territories of three municipalities, the latter is considered a municipal-level emergency. A state-level emergency occurs when the spread of the emergency exceeds the boundaries of the territories of three municipalities and (or) lasts for more than 6 months85.

According to the current Law on the State of Emergency of the Republic of Lithuania, crises in Lithuania are the situations caused by external or internal events or processes that threaten the vital or overriding national security interests of the Republic of Lithuania86.Unlike in the case of emergency events or emergencies, the national legislation does not contain criteria describing the scale or consequences of an event, according to which the event or the situation caused by it would be considered a crisis. For this reason, the distinction between a crisis and a state-level emergency remains unclear in Lithuania. Therefore, declaring the situation as a crisis can require a political decision of the Government.

In the new crisis and emergency management model submitted to the Government of the Republic of Lithuania at the end of July 202187, the concept of a crisis is developed in greater detail. For example, crises are said to include emergencies which, by their nature and scale, threaten national security interests, i.e. may have significant consequences for human health, the environment, state governance, the provision of essential services to society and the functioning of critical infrastructure, as well as incidents of a hybrid nature. The new model also provides that a crisis would cover such legal situations as a state of emergency or mobilisation in the country.

Following this typology, we mapped significant events in Lithuania from 2004 to 2020. The breakdown of crises and other significant events by the nature and magnitude is presented in the table below. We discuss each type of significant events in the following sections of the article.

Table 1. Breakdown of significant events in Lithuania by nature and magnitude, 2004–2020

|

Magnitude of the significant event |

||||

|

Low-impact / low-threat |

Medium-impact / medium-threat |

High-impact / high-threat |

||

|

Nature of the significant event |

Natural disasters |

MINIMUM NEED TO RESPOND |

Municipal-level emergencies due to: - geological and hydrometeorological events (62) (2006–2020); - communicable diseases in humans, other acute disorders of human health (2) (2007; 2017); - animal and plant diseases, insect infestations and outbreaks of agricultural diseases in the soil (29) (2006–2020) |

State-level emergencies due to: - outbreaks of African swine fever (2014); - damage to the agricultural sector caused by heavy rains (2017); - the risk of landslides on Gediminas Hill Upper castles (2017); - the effects of the drought in the agricultural sector (2) (2018, 2019); - the risk of spreading the new coronavirus (COVID-19) (2020) |

|

Anthropogenic disasters and incidents |

• Municipal-level emergencies due to: - technological disasters (16) (2006–2020); - ecological disasters (23) (2006-2020); - social disasters (2) (2006; 2009); - other disasters (11) (2006–2020) • Cyber incidents (~949 000) (2006–2020); • Violations of children’s rights, domestic violence, other outbreaks of violence in society causing scandals or large-scale public outrage (10) (2004–2020); • Environmental scandals, governance political scandals, other events causing large-scale public outrage (~70) (2004–2020) |

• The economic crisis (2008-2009); • State-level emergency due to a malfunctioning medical waste management and disposal system (2011); • Russia’s aggression against Ukraine (Annexation of Crimea) (2014); • The economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (2020)

|

||

Source: based on the reports of the Fire and Rescue Department under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania on the state of the civil system in Lithuania in 2006–2020; the additional data provided by the Fire and Rescue Department on emergency events and emergencies in Lithuania in 2006–2020; the reports of the National Electronic Communications Networks and Information Security Incident Response Team of the Communications Regulatory Authority of the Republic of Lithuania (CERT-LT) in 2006–2017; the national cyber security status reports of the National Cyber Security Centre under the Ministry of National Defense in Lithuania in 2016–2020; the data provided by the news agency BNS on the most important political and public life events in Lithuania every year during the period analysed in this study; and the results of the monitoring of articles on political scandals in Lithuania in 2004–2018, conducted on the website delfi.lt and presented in: Inga Patkauskaitė-Tiuchtienė, “The Impact of Political Scandals on Trust in State Institutions: Lithuanian Case Analysis”, Politologija 98, no. 2 (2020): 8–4588.

3.1. Significant events of high-impact/high-threat

State-level emergencies and crises. During the period analysed in this article, 7 state-level emergencies were declared in Lithuania and two significant crises occurred. In 2011, the first state-level emergency in Lithuania was declared due to a malfunctioning medical waste management and disposal system in the country with an accumulation of more than 119 tons of medical waste. Their storage sites threatened to create the outbreak of an epidemic and endangered the population of the country89. Other state-level emergencies in Lithuania were declared in 2014, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020. Depending on their nature, they may be classified as natural disasters. In 2014, a state-level emergency was declared due to the spread of swine fever in many Lithuanian municipalities including Alytus, Varėna, Lazdijai, Šalčininkai, Trakai and Druskininkai90. In 2017, a state-level emergency was declared due to the damage caused to the agricultural sector by heavy rains, as well as the risk of landslides on the Gediminas Hill Upper castle91. In 2018 and 2019, a state-level emergency was declared due to the effects of the drought in the agricultural sector92.

In 2020, the risk of spreading the new coronavirus (COVID-19) led to another state-level emergency and in a nationwide quarantine. Therefore, this pandemic can undoubtedly be named as one of the most significant events in Lithuania because it not only claimed lives but also disrupted the normal functioning of the health care and education systems, and the work of state and municipal institutions. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic and the public health measures adopted to control the spread of the coronavirus led to an economic crisis in the country. However, Lithuanian authorities were not properly prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic and encountered significant difficulties in managing its second wave. Therefore, in its programme the 2020–2024 Lithuanian government led by Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė made a commitment to develop an effective crisis and emergency management model in the country by establishing a national emergency centre, as well as strengthening the resilience of the health system to various threats and preparing for future challenges93.

Another significant event of high-impact/high-threat in Lithuania was the economic crisis of 2008–2009, caused by the global financial crisis of 2008 (the so-called Great Recession). The latter has had a major negative impact on the Lithuanian economy and public finances, as well as on many state-funded public sectors services. In 2009, Lithuania’s GDP fell by almost 15%, which was one of the largest indicators among all EU countries (with the EU average in that year amounting to –4.3%)94.

Other significant events of high-impact/high-threat. As already mentioned, significant events may arise not only from the occurrence of natural risks or the malfunctioning of social-technical and (or) political-administrative systems, but also from the deliberate actions of actors with hostile goals inside or outside the country. The latter threats have become particularly pronounced in a “hyper-connected” world, as shown by the prevalence of cyber-attacks, the use of various sanctions or migratory flows to put pressure on other countries’ politicians and society in recent years95. Increasing global competition between democracies and autocracies, especially the growing rivalry between the US and China, are exacerbating such threats. In addition, Lithuania’s geopolitical position also reinforces the potential impact of this type of external influence, as demonstrated by Russia’s sanctions on Lithuanian companies or Belarus’s attempts to put pressure on Lithuania and other EU countries by instrumentalising illegal migration flows. Even hostile activities not directly targeted against Lithuania can have a significant impact on domestic policymaking processes. For instance, the country’s politicians and society reacted to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2014 in general and to large-scale cyber and information attacks carried out during this aggression more specifically.

After the annexation of Crimea, the attention of decision-makers to territorial defence in Lithuania increased significantly. For instance, an agreement was reached between the parliamentary parties to increase defence spending in Lithuania, as well as to re-introduce the conscript army. Also, the need to strengthen information and cyber security became more urgent in the country. The increased attention to information and cyber security in Lithuania and the need to strengthen it after Russia’s aggression against Ukraine in 2014 is well illustrated by the annual speeches of President Dalia Grybauskaitė (see the President’s annual speeches of 2014, 2015, 2016). In addition, the National Security Strategy of the Republic of Lithuania, updated in 2017, also identified information and cyber incidents as threats to which the country’s security institutions must pay special attention96.

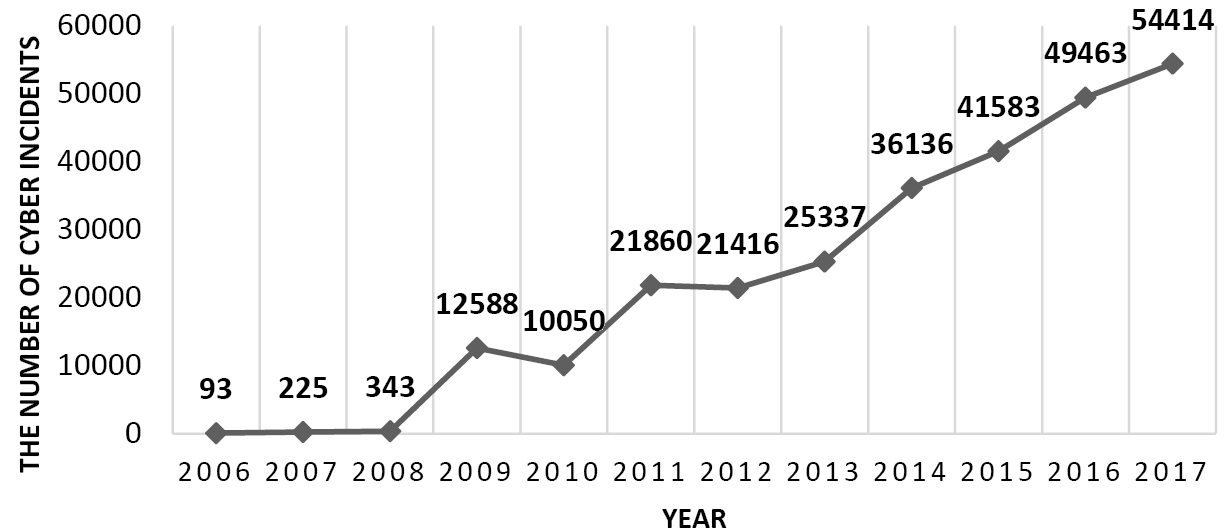

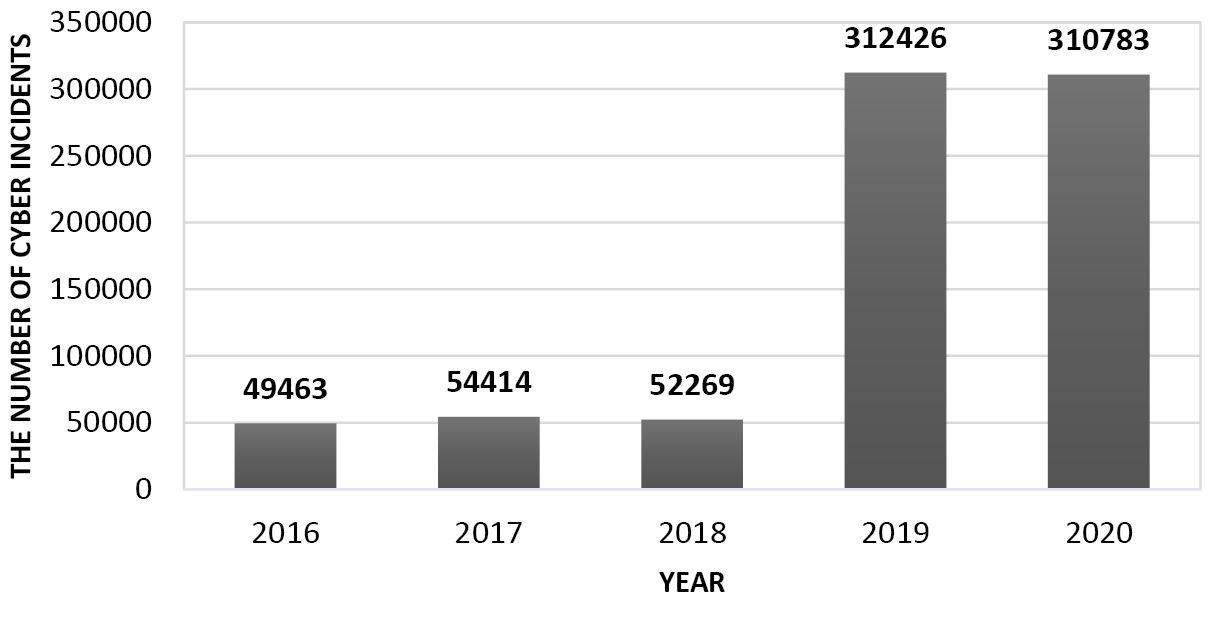

It is likely that domestic cyber incidents have also provided an important background for the need to strengthen information and cyber security in Lithuania. The reports on cyber incidents in Lithuania clearly demonstrate an upward trend, though it might be an outcome of both greater intensity of incidents and better capacities of detecting them (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). However, cyber incidents in Lithuania in 2004–2020 were not large-scale but were mostly limited to the level of organisations or groups of organisations. Therefore, we classify them as medium-impact/medium-threat events.

Figure 1. The number of cyber incidents in Lithuania (processed by automatic means and manually), 2006–2017

Source: based on the reports of the National Electronic Communications Networks and Information Security Incident Response Team of the Communications Regulatory Authority of the Republic of Lithuania (CERT-LT), 2006–2017.

Figure 2. The number of cyber incidents in Lithuania (processed by automatic means), 2016–2020

Source: based on the national cyber security status reports of the National Cyber Security Centre under the Ministry of National Defence in Lithuania, 2016–2020.

3.2. Significant events of medium-impact/medium-threat

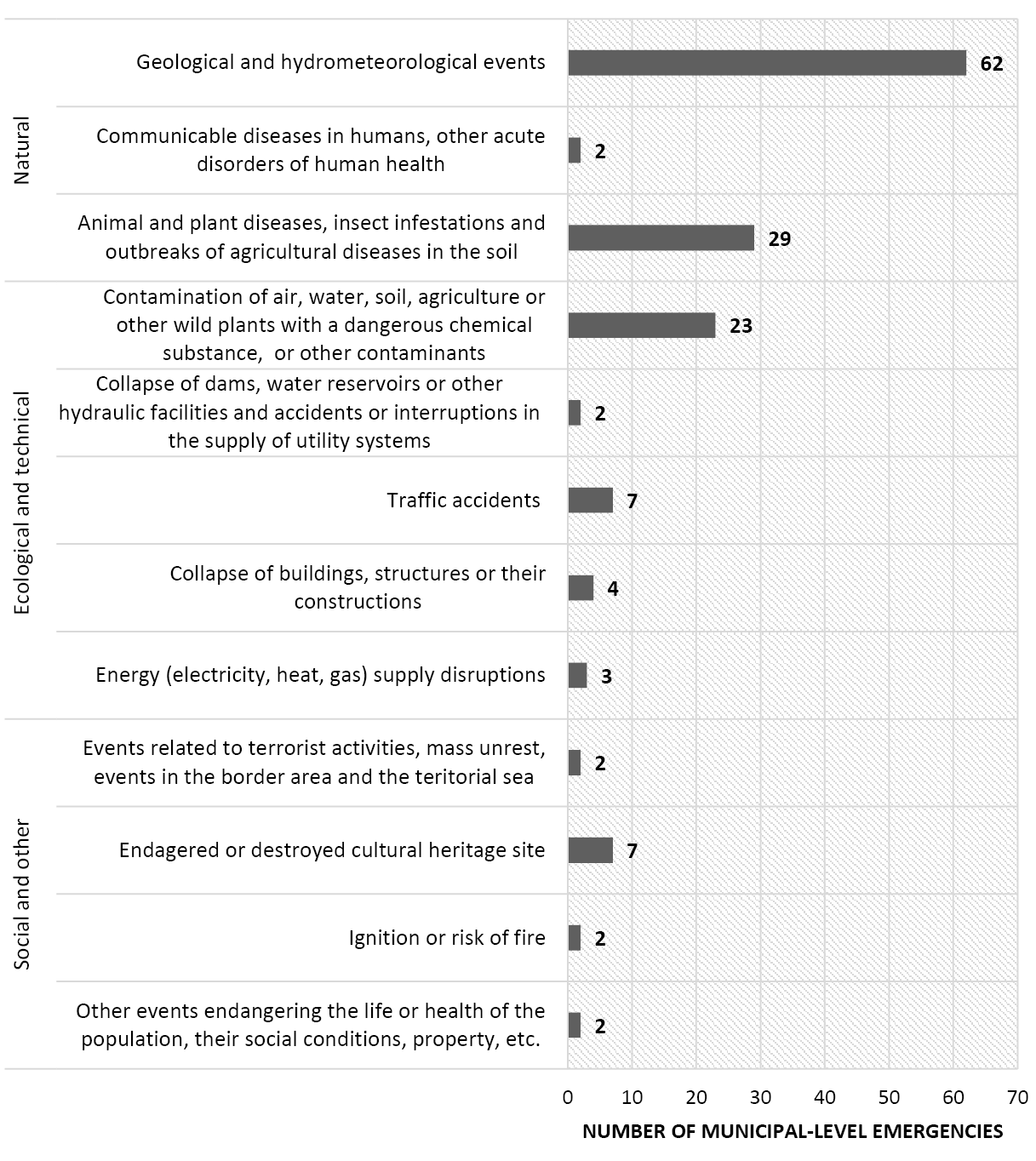

Municipal-level emergencies. During the period analysed in this article, 145 municipal-level emergencies were declared in Lithuania. Most of them were natural emergencies (93 or ~64%), which can be divided into three main subtypes: (1) geological and hydrometeorological events (62 or ~43%); (2) communicable diseases in humans, other acute disorders of human health (2 or ~1%); and (3) animal and plant diseases, insect infestations and outbreaks of agricultural diseases in the soil (29 or ~20%). Other municipal-level emergencies in Lithuania, depending on their nature, can be classified as anthropogenic disasters and incidents (59 or ~39%). Most of them were ecological (23 or ~16%), i.e., declared due to a contamination of air, water, soil, agriculture or other wild plants with a dangerous chemical substance, radioactive substances or other contaminants. Some of them were also of technological nature (16 or ~11%), falling into these following main subtypes: (1) energy (electricity, heat, gas) supply disruptions (3 or ~2%); (2) collapse of buildings, structures or their constructions (4 or ~3%); (3) traffic accidents (7 or ~5%); and (4) collapse of dams, water reservoirs or other hydraulic facilities and accidents or interruptions in the supply of utility systems (2 or 1%). The lowest number of municipal-level emergencies that occurred in Lithuania during 2004–2020 was of social nature (2 or 1%)97. A more detailed distribution of municipal-level emergencies in Lithuania during this period depending on their nature is presented in Figure 3.

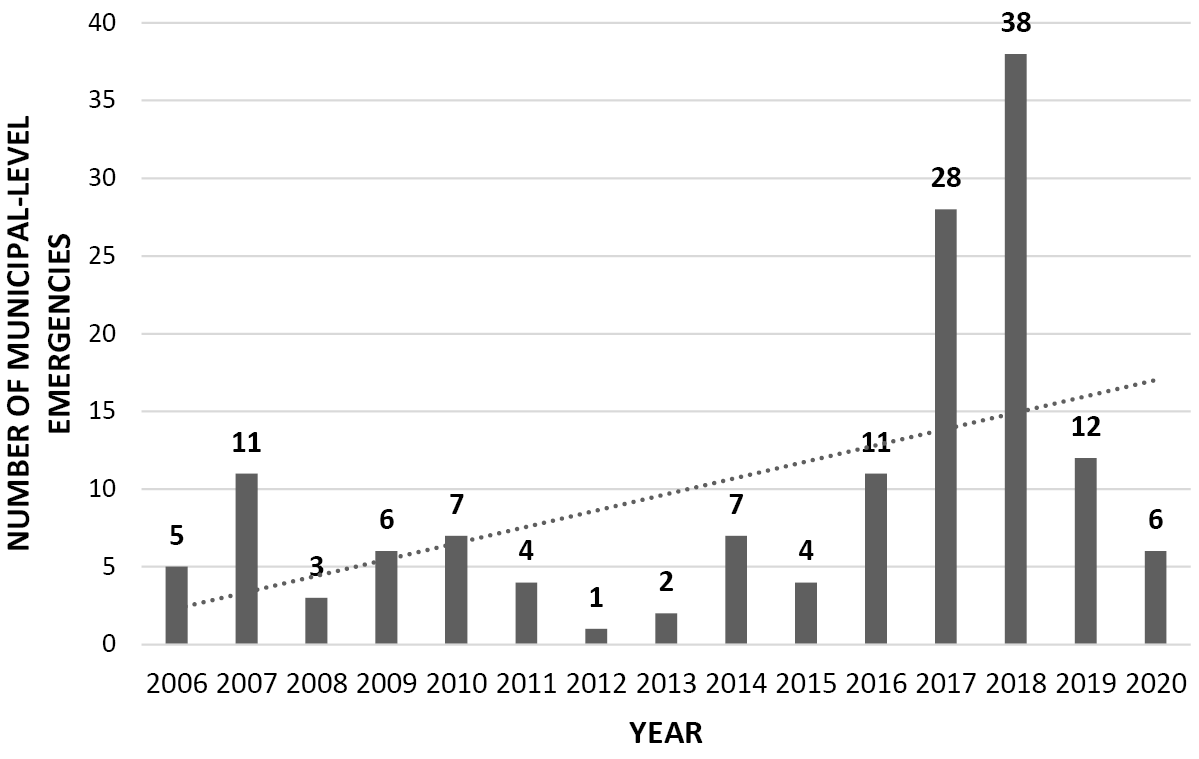

The collected data on emergencies in Lithuania also reveal a significant increase in the number of declared municipal-level emergencies observed in the country in the last five years (excluding 2021). In 2016–2020, a total of 95 municipal-level emergencies were declared in Lithuania, which exceeds the number of municipal-level emergencies declared in 2011–2015 by five times, and the number of such emergencies declared in the ten-year period from 2006 to 2015 by almost two times (see Figure 4)98. This sharp increase in the number of municipal-level emergencies was due largely to the intensification of dangerous meteorological events, such as droughts, rains, or floods99. According to the forecasts of the Lithuanian Hydrometeorological Service, the number of such events is likely to further increase in the future due to climate change100, possibly leading to an increasing number of related emergencies in Lithuania. However, due to the country’s geographical location, floods, rains, droughts or other meteorological events related to climate change have posed relatively low risks or damages. This probably explains the relatively low attention paid by policymakers or society in Lithuania to these natural events.

Figure 3. Distribution of municipal-level emergencies in Lithuania by nature, 2006–2020

Source: based on the reports of the Fire and Rescue Department under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania on the state of the civil system in Lithuania in 2006–2020 and the additional data provided by the Fire and Rescue Department on emergency events and emergencies in Lithuania in 2006–2020.

Figure 4. Trends in the number of municipal-level emergencies in Lithuania, 2006–2020

Source: based on the reports of the Fire and Rescue Department under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania on the state of the civil system in Lithuania in 2006–2020.

It is important to mention one municipal-level event that recently attracted a lot of attention from the public, media, and politicians not only locally, but also at the national level. It was the fire at the Alytus tire processing plant Ekologistika that took place in October 2019 and lasted for as long as 10 days. Two municipal-level emergencies were declared in Alytus city and Alytus district municipalities as a result of this ecological disaster. Such focus on this event may be attributable to the fact that it was not considered to be merely an accident but that it also revealed that Lithuanian authorities were not prepared to prevent ecological disasters and respond adequately to a sudden large-scale disaster. Also, this significant event highlighted shortcomings in the performance of the Ministry of Environment and its subordinate institutions responsible for the implementation of environmental policy, as well as the Fire and Rescue Department under the Ministry of the Interior101.

Less than three months after the fire at the Ekologistika plant, information about another major case of environmental pollution in Lithuania appeared in the media. The so-called Grigeo wastewater scandal broke out when it became clear that the company Grigeo Klaipėda illegally discharged untreated wastewater into the Curonian Lagoon, thus causing enormous damage to nature102. In January 2020, other cases of environmental pollution were registered in Lithuania, including an illegal discharge of wastewater into the environments in Utena103 and Kėdainiai104 or a discharge of wastewater containing plastic particles into the Neris River in Vilnius105. All these successive cases of environmental pollution shocked the Lithuanian society, policymakers and officials106. As a result, in January 2020, the Lithuanian parliament called a special parliamentary session and adopted amendments to the legislation. The so-called “Klaipėda package” tightened state control over environmental protection, pollution prevention requirements, the regulation of pollution permits, and introduced significantly higher taxes on pollution107.

Other significant events of medium-impact/medium-threat. As already mentioned in section 1.1. on the characteristics of significant events, the focusing potential of events or their impetus for public policy and (or) institutional change does not necessarily depend directly on the magnitude of the damage done or the level of risk posed, as perceptions of the latter may depend very much on the context. As revealed by the data provided by the news agency BNS on the most important political and public life events in Lithuania every year, events with relatively low risk or damage may cause large-scale public outrage and may be widely regarded as significant events.

Violations of children’s rights, domestic violence and other outbreaks of violence in society can be distinguished as a group of such events. Despite their relatively small scale or magnitude, they received exceptional national level media, public and political attention in Lithuania. This may be due to the fact that both in the media and among political actors the occurrence of such events and their outcomes was closely linked to a lack of political attention to important societal issues, gaps in the implementation of some public policies, or shortcomings in the performance of responsible state or municipal institutions and civil servants. This could have clearly demonstrated a mismatch between the state of policy design and execution in the country on the one hand, as well as the society’s expectations on the other.

For example, even though there was a continuously increasing trend (with some deviations in 2014 and 2018) in the number of children who might have experienced violence between 2006 and 2020108, there were no significant changes in this policy subsystem, while attempts to reform the children rights protection system were struggling to overcome political disagreements. The situation has significantly changed after two major events: the tragedies of Saviečiai (2016) and Matukas (2017), in both of which children became victims of their parents’ violence. These incidents highlighted the shortcomings of the children rights protection system in the country and mobilised the society, resulting in an urgent need to reform.

In February 2017, a special parliamentary session was called, resulting in amendments of the Law on the Fundamentals of the Protection of the Rights of the Child of the Republic of Lithuania109, which included a distinction between different forms of violence and a complete prohibition of corporal punishment or violent behaviour against children. In September 2017, the Parliament laid out the new version of the Law to implement the so-called “Matukas reform”, based on the centralisation of the children rights protection system. The reform allowed clarifying responsibilities of state and municipal institutions in safeguarding the rights and legitimate interests of children as well as introduced prevention measures to ensure their safety (e.g., the establishment of criteria and procedures to determine the level of threat to a child, creation of mobile teams to provide support for families, as well as introduction of “case management”).

Another group of medium-impact/medium-threat events that caused scandals or great public outrage in Lithuania in 2004–2020 can be attributed to the actions of policymakers or civil servants who were suspected of breaking the law or exceeding the boundaries of values, norms or moral convictions established and/or prevailing in society. Most of these events were related to various types of suspected corruption (e.g. bribery, trading in influence or abuse of office when the position was used not in the interests of the service but for personal gain), as well as to the actions of policymakers or civil servants that led to suspicions that the principles of conduct and ethics have been violated.

Research in Lithuania also shows that political scandals in Lithuania have a significant negative but short-term impact on public confidence in state institutions, such as the parliament and the government110. However, the short-term negative impact of political scandals does not in itself mean that political scandals can be considered “less dangerous” or do not cause significant damage to trust in the political authorities, as political scandals in Lithuania are not exceptional but permanent – they occur approximately every three and a half months111. Thus, it means that the negative impact of political scandals on public confidence in state institutions is constantly being exerted.

However, as political scandals, often seen as examples of “bad governance”, fall horizontally into all areas of governance, their impact on public policy or institutional change is proposed to be analysed not in isolation but as a complementary variable that can act as both a barrier and an impetus to implement changes in relevant public policy areas.

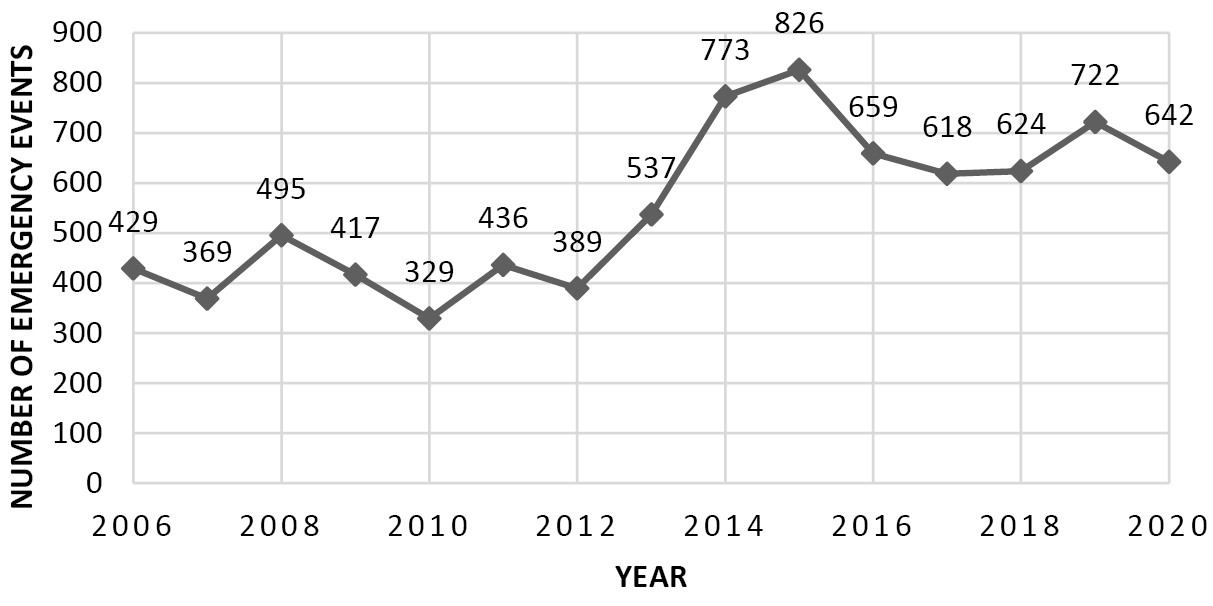

3.3. Significant events of low-impact/low-threat

Emergency events. During the period analysed in this article more than 8,000 emergency events occurred in Lithuania. From 2014 to 2020, the annual number of these events increased significantly compared to 2006–2013 (see Figure 5). This was due to an increase in the number of explosives found due to the intensified excavation works during the expansion of the country’s infrastructure, construction of residential houses, and implementation of projects of state significance. The explosives found accounted for about 90% of emergency events each year112.

Figure 5. Trends in emergency events in Lithuania, 2006–2020

Source: based on the reports of the Fire and Rescue Department under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania on the state of the civil system in Lithuania in 2006–2020.

However, as emergency events are relatively common and have a relatively low level of threat or damage, local rapid response services are usually sufficient to deal with their consequences. Therefore, their impetus for public policy or institutional change is the least likely compared to other significant events presented earlier.

To sum up, our empirical research revealed the extent and distribution of varying magnitude and nature significant events in different public policy areas, indicating the most promising fields for further analysis. Therefore, the following public policy areas and significant events within them were chosen for the in-depth exploration of suggested pathways towards policy change: (1) COVID-19 infectious disease and its impact on the Lithuanian health care system; (2) Cyber incidents and their impact on the Lithuanian information and cyber security system; (3) Environmental (ecological) disasters and their impact on Lithuanian environmental policy; and (4) Cases of violence against children and their impact on Lithuanian child protection policy. A further analysis of the effects of those significant events, which differ in terms of their characteristics, should allow for a fruitful comparison of the causal mechanisms that mediate how these events affect public policy and institutional change and the comparison of the trajectories of these changes.

Conclusions and discussion

There is a common agreement on the growing global importance of significant events for the contemporary functioning of societies and welfare states, especially due to the cross-border effects of many natural phenomena and anthropogenic activities. Coupled with these events, fast technological and scientific developments add to turbulence in the everyday policy environment, producing highly variable and unpredictable demands on policymaking and implementation113. These developments are expected to continue in the future due to the proliferation of global risks such as climate change, pandemics, irregular migration and military conflicts. Their occurrence within a complex network of interdependencies could be exploited for malign activities such as cyber-attacks or conventional large-scale military conflicts as initiated by Russia against Ukraine in late February 2022. The latter has a potential to trigger significant policy and institutional changes in the EU and its member states such as transformation of energy trade in fossil fuels, defence policy and others.

Some authors argue that humanity is now living in an “era of compounded economic, environmental, geopolitical and technological risks” that might deepen existing societal divisions, put pressure on democratic models of governance and values as well as complicate proper policy responses aimed at adapting welfare institutions and increasing the resilience of societies114. Therefore, it is extremely relevant to explore how governance systems react to various significant events and how precisely they lead towards different outcomes, including inaction, paradigmatic or incremental policy change. Responding to a call for a “more careful theorizing regarding the role and impact of crises on policymaking”115, in this article we outlined the research agenda on assessing the effects of significant events on public policies, governance and institutions.

The novelty of our approach lies within moving away from an event-based focus116 towards an interplay of contextual, public policy subsystem, and event characteristics. We argue that different configurations of these variables might activate diverging policy responses and thus, lead towards varying impact on public policies, governance and institutions. In addition, instead of developing rather nuanced explanations from the field of public policy or attempts to theorize trajectories of change in the field of crisis management, our central interest was to combine both approaches. By linking the insights of research on crisis management and public policy process, we suggested three pathways (in particular the “big bang”, the “muddling through” and policy learning) that connect a significant event with the following policy change.

Even though they shed more light on the relationship between a significant event and policy change, there is a clear need for a more thorough exploration of these pathways. Therefore, we suggest a future research agenda with an aim to better theorize the mechanisms of change based on their actual manifestations in practice and define the interplay of different pathways (i.e., whether and which explanations could support each other). In other words, complementing a range of insights and synthesising them provides us with an opportunity to accumulate more knowledge on policymaking and implementation in turbulent environments, as well as to combine innovative academic ideas with practical policy suggestions.

We aim to overcome the typical confirmation bias and thus propose analysing the effects of significant events by first looking into their characteristics, which determine the transformational potential of these events and define an urgency (need) for change. Since these events mainly act as critical junctures opening different windows of opportunities, it is then necessary to trace the trajectories of change originating from the concrete events by exploring political, public and media attention, as well as the variables related to the interaction of advocacy coalitions within different policy sub-systems. We suggest analysing how events of different nature and magnitude in four different policy areas (health care, environmental protection, protection of children rights and cyber security) shaped popular, media and policy-makers’ responses, how these responses were filtered through coalition politics, and how learning from implementation informed the public policy process.

We offer to use the methodology of process tracing to assess the effects of the selected events on public policies, governance, and institutions in Lithuania with particular attention to the nature of change, the causal mechanism of change and the effects of those events on the country’s welfare institutions. We are aware of the potential complications of having to trace causal relationships by analysing a relatively large set of variables within proposed case studies. However, effectively complementing the three pathways and focusing on the most appropriate conceptual framework would allow to produce a sound synthesised explanation instead of ending up with a series of different perspectives on change within specific policy areas. Also, a rigorous application of research methods – an analysis of primary and secondary information sources (including discursive analysis), and interviews with policymakers and stakeholders, which ensure the triangulation of information, would help to achieve reliable research results.

Overall, our study confirms the increasing relevance of significant events and thus highlights the need for more encompassing approaches towards their impact on policy change. We suggest that the latter should go beyond a mere focus on their characteristics. Instead, we offer to look at the complex interplay among contextual, public policy subsystem, and event characteristics that shape different pathways towards public policy, governance and institutional change. The results of our empirical research set the ground for implementing the proposed research agenda by indicating public policy areas for further in-depth analysis through case studies.

References

“Law on Civil Protection of Republic of Lithuania.” Valstybės žinios, no. 115-3230 (1998). Accessed December 3, 2021. https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.69957/asr

„Lietuvos Respublikos nepaprastosios padėties įstatymo Nr. IX-938 2, 3, 13, 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 24 ir 31 straipsnių pakeitimo įstatymas.“ TAR, no. 10927 (2019). Accessed December 3, 2021. https://e seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/0ca15e80997b11e9aab6d8dd69c6da66?jfwid=-kyruxeds4

„Lietuvos Respublikos Seimo 2017 m. sausio 17 d. nutarimas Nr. XIII-202 „Dėl Lietuvos Respublikos Seimo 2002 m. gegužės 28 d. nutarimo Nr. IX-907 „Dėl Nacionalinio saugumo strategijos patvirtinimo“ pakeitimo.“ TAR, no. 1424 (2017). Accessed December 30, 2021. https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/4c80a722e2fa11e6be918a531b2126ab

„Lietuvos Respublikos vaiko teisių apsaugos pagrindų įstatymo Nr. I-1234 2, 6, 10, 49, 56, 57 straipsnių pakeitimo ir įstatymo papildymo 2–1 straipsniu įstatymas.“ TAR, no. 2780 (2017). Accessed December 04, 2021. https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/7d592952f37411e6be918a531b2126ab

„Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybės 2006 m. kovo 9 d. nutarimas Nr. 241 „Dėl ekstremaliųjų įvykių kriterijų sąrašo patvirtinimo.“ Valstybės žinios, no. 29-1004 (2006). Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/TAR.F2432CA5A7F8/asr

„Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybės 2021 m. kovo 10 d. nutarimas Nr. 155 „Dėl Aštuonioliktosios Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybės programos nuostatų įgyvendinimo plano.“ TAR, no. 5318 (2021). Accessed December 04, 2021. https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/d698ded086fe11eb9fecb5ecd3bd711c

15min. „Mažasis Černobylis Alytuje: pasitikėjimo valdžia ir vadovais krizė.“ Accessed December 4, 2021. https://www.15min.lt/media-pasakojimai/mazasis-cernobylis-alytuje-pasitikejimo-valdzia-ir-vadovais-krize-846

Albright, A. Elizabeth and Deserai A. Crow. “Capacity Building toward Resilience: How Communities Recover, Learn, and Change in the Aftermath of Extreme Events.” Policy Studies Journal 49, no. 1 (2021): 89–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12364

Albright, A. Elizabeth. “Policy Change and Learning in Response to Extreme Flood Events in Hungary: An Advocacy Coalition Approach.” Policy Studies Journal 39, no. 3 (2011): 485–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00418.x

Alimi, Y. Eitan and Gregory M. Maney. “Focusing on Focusing Events: Event Selection, Media Coverage, and the Dynamics of Contentious Meaning-Making.” Sociological Forum 33, (2018): 757–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12442

Ansell, Christopher, Sørensen, Eva and Jacob Torfing. “The COVID-19 Pandemic as a Game Changer for Public Administration and Leadership? The Need for Robust Governance Responses to Turbulent Problems.” Public Management Review 23, no. 7 (2021): 949–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1820272

Balleisen, J. Edward, Lori S. Bennear, Kimberly D. Krawiec and Jonathan B. Wiener. “Recalibrating Risk: Crises, Learning, and Regulatory Change.” In Policy Shock: Recalibrating Risk and Regulation after Oil Spills, Nuclear Accidents and Financial Crises, edited by E. J. Balleisen, L. S. Bennear, K. D. Krawiec, J. B. Wiener, 540–561. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Baumgartner, R. Frank and Bryan D. Jones. Agendas and Instability in American Politics (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Baužytė, Malvina, BNS, ELTA. „Klaipėdos paketas“ priimtas: Seimas sugriežtino aplinkos taršos kontrolę.“ Lrytas.lt. Accessed December 01, 2021. https://www.lrytas.lt/gamta/eko/2020/01/28/news/-klaipedos-paketas-priimtas-seimas-sugrieztino-aplinkos-tarsos-kontrole-13422076

Bernardinai.lt. „Dėl vaiko teisių apsaugos – neeilinė Seimo sesija.“ Accessed November 30. 2021. https://www.bernardinai.lt/2017-02-14-del-vaiko-teisiu-apsaugos-neeiline-seimo-sesija/

Birkland, A. Thomas and Kathryn L. Schwaeble. “Agenda Setting and the Policy Process: Focusing Events.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics (2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.165

Birkland, A. Thomas. “Disasters, Lessons Learned, and Fantasy Documents.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 17, no. 3 (2009): 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00575.x

Birkland, A. Thomas. “Learning and Policy Improvement after Disaster: The Case of Aviation Security.” American Behavioral Scientist 48, no. 3 (2004): 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0002764204268990.

Birkland, A. Thomas. After Disaster: Agenda Setting, Public Policy and Focusing Events. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1997.

Birkland, A. Thomas. Lessons of Disaster: Policy Change after Catastrophic Events. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

BNS. „Baigtas tyrimas dėl „Grigeo Klaipėdos“ taršos.“ Delfi. Accessed December 02, 2021. https://www.delfi.lt/verslas/verslas/baigtas-tyrimas-del-grigeo-klaipedos-tarsos.d?id=88069743

Böhmelt, Tobias. „Environmental Disasters and Public-Opinion Formation: A Natural Experiment.“ Environmental Research Communications 2, no. 8 (2020): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/abacaa

Boin, Arjen and Paul ‘t Hart. “Between Crisis and Normalcy: The Long Shadow of Post-Crisis Politics.” In Managing Crises: Threats, Dilemmas, Opportunities, edited by U. Rosenthal, A. Boin, L. Comfort, 28–46. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 2001.

Boin, Arjen and Paul ‘t Hart. “Organising for Effective Emergency Management: Lessons from Research.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 69, no. 4 (2010): 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2010.00694.x.

Boin, Arjen, Paul ‘t Hart, and Sanneke Kuipers. “The Crisis Approach.” In Handbook of Disaster Research. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research, edited by H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, J. Trainor, 23–38. Springer, Cham, 2017.

Boin, Arjen and Paul ‘t Hart. “From Crisis to Reform? Exploring Three post-COVID Pathways.” Policy and Society 41, no. 1 (2022): 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puab007.

Boin, Arjen. “From Crisis to Disaster: Towards an Integrative Perspective.” In What is a Disaster? New Answers to Old Questions, edited by R. W. Perry and E. L. Quarantelli, 153–172. Philadelphia: Xlibris, 2005.

Brown, C. G. David and Jacek Czaputowicz. “Governance and Public Administration Capacities for Dealing with Disaster.” In Dealing with Disaster: Public Capacities for Crisis and Contingency Management, edited by D. C. G. Brown, J. Czaputowicz. Brussels: IIAS–IISA, 2021.

Burstein, Paul. “The Impact of Public Opinion on Public Policy: A Review and an Agenda.” Political Research Quarterly 56, no. 1 (2003): 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F106591290305600103

Crow, A. Deserai, Elizabeth A. Albright and Elizabeth Koebele. “The Role of Coalitions in Disaster Policymaking.” Disasters 45, no. 1 (2021): 19–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12396

Crow, A. Deserai, John Berggren, Lydia A. Lawhon, Elizabeth A. Koebele, Adrianne Kroepsch and Juhi Huda. “Local Media Coverage of Wildfire Disasters: An Analysis of Problems and Solutions in Policy Narratives.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35, no. 5 (2017): 849–871. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0263774X16667302

Danauskienė, Vilma. „Po Alytaus gaisro prokurorai tiria ir aplinkosaugininkų bei „Ekologistikos“ vadovų veiksmus“. Delfi, accessed December 4, 2021. https://www.delfi.lt/news/daily/lithuania/po-alytaus-gaisro-prokurorai-tiria-ir-aplinkosaugininku-bei-ekologistikos-vadovu-veiksmus.d?id=82653847

DeLeo, A. Rob, Kristin Taylor, Deserai A. Crow and Thomas A. Birkland. “During Disaster: Refining the Concept of Focusing Events to Better Explain Long-Duration Crises.” International Review of Public Policy 3, no. 1 (2021): 8–28. http://journals.openedition.org/irpp/1868

Deverell, Edward. “Learning and Crisis.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics (2021). https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1558

European Commission. “2021 Strategic Foresight Report: The EU’s Capacity and Freedom to Act.” Secretariat General, European Commission, Brussels, Belgium, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2792/55981

Farrell, Henry and Abraham L. Newman. „Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion“. International Security 44, no. 1 (2019): 42–79. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00351

Fire and Rescue Department under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania. Overview of the State of the Civil System in Lithuania in 2006–2020. Accessed December 04, 2021. https://pagd.lrv.lt/lt/veiklos-sritys-1/civiline-sauga/civilines-saugos-sistemos-bukle

Grigaliūnaitė, Violeta. „Po informacijos apie Neries taršą plastiku „Vilniaus vandenys“ ėmėsi tyrimo: tokių teršalų neturi būti“. 15min, accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.15min.lt/naujiena/aktualu/lietuva/po-informacijos-apie-neries-tarsa-plastiku-vilniaus-vandenys-emesi-tyrimo-tokiu-tersalu-neturi-buti-56-1263108

Hall, A. Peter. “Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain.” Comparative Politics 25, no. 3 (1993): 275–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/422246

Jones, D. Bryan and Frank R. Baumgartner. “From There to Here: Punctuated Equilibrium to the General Punctuation Thesis to a Theory of Government Information Processing.” The Policy Studies Journal 40, no. 1 (2012): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00431.x

Jones, D. Bryan and Hank C. Jenkins-Smith. “Trans-Subsystem Dynamics: Policy Topography, Mass Opinion, and Policy Change.” Policy Studies Journal 37, no. 1 (2009): 37–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00294.x

Kingdon, W. John. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (2nd ed.). Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1995.

Lančinskas, Kęstutis. „Darbo grupės pasiūlymai dėl krizių ir ekstremaliųjų situacijų valdymo modelio.“ July 28, 2021, Meeting of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania, accessed 31 December, 31, 2021. https://lrv.lt/lt/posedziai/lietuvos-respublikos-vyriausybes-pasitarimas-182

Leonard, Mark. Weaponizing Interdependence: Why Migration, Finance and Trade are the Geo-Economic Battlegrounds of the Future. London: European Council on Foreign Relations, 2016. Accessed December 4, 2021. http://www.ecfr.eu/europeanpower/geoeconomics

Lithuanian Hydrometeorological Service. „Klimato kaitos priežastys ir pasekmės.“ Accessed December 4, 2021. http://www.meteo.lt/lt/klimato-kaita

LRT. „Aplinkosaugininkai Kėdainiuose veikiančią įmonę įtaria teršus bevardį upelį.“ Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/verslas/4/1135571/aplinkosaugininkai-kedainiuose-veikiancia-imone-itaria-tersus-bevardi-upeli

McConnell, Allan and Paul ’t Hart. “Inaction and Public Policy: Understanding why Policymakers ‘do nothing’.” Policy Science 52, (2019): 645–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-019-09362-2

McConnell, Allan. “The Politics of Crisis Terminology.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1590

Ministry of Social Security and Labour. Children, who Potentially suffered from Violence 2006–2020. June 11, 2021. Distributed by Official Statistics Portal. Accessed December 31, 2021. https://osp.stat.gov.lt/en/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize?hash=8b601ba8-7960-421a-83f3-c49f20f60cef

Mintrom, Michael and Phillipa Norman. “Policy Entrepreneurship and Policy Change.” Policy Studies Journal 37, no. 4 (2009): 649–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2009.00329.x

Monahan, Brian and Matthew Ettinger. “News Media and Disasters: Navigating Old Challenges and New Opportunities in the Digital Age.” In Handbook of Disaster Research. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research, edited by H. Rodríguez, W. Donner, J. Trainor, 479–495. Springer International Publishing, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_23

Nakrošis, Vitalis, Ramūnas Vilpišauskas and Egidijus Barcevičius. “Making Change Happen: Policy Dynamics in the Adoption of Major Reforms in Lithuania.” Public Policy and Administration 34, no. 4 (2019): 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0952076718755568

Nohrstedt, Daniel and Christopher M. Weible. “The Logic of Policy Change after Crisis: Proximity and Subsystem Interaction.” Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 1, no. 2 (2010): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.2202/1944-4079.1035

Nohrstedt, Daniel. “External Shocks and Policy Change: Three Mile Island and Swedish Nuclear Energy Policy.” Journal of European Public Policy 12, no. 6 (2005): 1041–1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500270729

Nohrstedt, Daniel. “Shifting Resources and Venues Producing Policy Change in Contested Subsystems: A Case Study of Swedish Signals Intelligence Policy.” Policy Studies Journal 39, no. 3 (2011): 461–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00417.x

Nohrstedt, Daniel. “The Politics of Crisis Policymaking: Chernobyl and Swedish Nuclear Energy Policy.” Policy Studies Journal 36, no. 2 (2008): 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00265.x

O’Donovan, Kristin. “An Assessment of Aggregate Focusing Events, Disaster Experience, and Policy Change.” Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 8, no. 3 (2017): 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12116

Patkauskaitė-Tiuchtienė, Inga. “The Impact of Political Scandals on Trust in State Institutions: Lithuanian Case Analysis.” Politologija 98, no. 2 (2020): 8–45. https://doi.org/10.15388/Polit.2020.98.1

Ragulskytė-Markovienė, Rasa. „Klaipėdos paketas“ – aplinkos taršos kontrolės ir atsakomybės griežtinimo rezultatas.“ Lietuvos teisė 2020. Esminiai pokyčiai. 2 dalis (2020): 45–51. https://doi.org/10.13165/LT-20-02-05

Sabatier, A. Paul and Christopher M. Weible. “The Advocacy Coalition Framework: Innovations and Clarifications.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by P. A. Sabatier, 189–220. West Press: Colorado, 2007.

Sabatier, A. Paul. “The Advocacy Coalition Framework: Revisions and Relevance for Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 5, no. 1 (1998): 98–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501768880000051

Savickas, Edgaras. „Taršos skandalas atsirito ir iki Utenos: įmonė nevalytų atliekų duobę slėpė po tentu.“ Delfi, accessed December 3, 2021. https://www.delfi.lt/verslas/verslas/tarsos-skandalas-atsirito-ir-iki-utenos-imone-nevalytu-atlieku-duobe-slepe-po-tentu.d?id=83340623

Schwarzer, Daniela. “Weaponizing the Economy.” Berlin Policy Journal (January/February 2020). Accessed December 4, 2021. https://berlinpolicyjournal.com/weaponizing-the-economy/

The World Bank. Accessed December 4, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=EU-LT

Touchant, Lauren and Aaida A. Mamuji. “Theoretical Perspectives on Disasters.” In Dealing with Disaster: Public Capacities for Crisis and Contingency Management, edited by D. C. G. Brown, J. Czaputowicz. Brussels: IIAS–IISA, 2021.

Vilpišauskas, Ramūnas, Vitalis Nakrošis. Politikos įgyvendinimas Lietuvoje ir Europos Sąjungoje. Vilnius: Eugrimas, 2003.

Walgrave, Stefaan and Frederic Varone. “Punctuated Equilibrium and Agenda-Setting: Bringing Parties Back in: Policy Change after the Dutroux Crisis in Belgium.” Governance 21, (2008): 365–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00404.x

Weible, M. Christopher, Paul A. Sabatier, Hank C. Jenkins-Smith, Daniel Nohrstedt, Adam D. Henry and Paul de Leon. “A Quarter Century of the Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Introduction to the Special Issue.” The Policy Studies Journal 39, no. 3 (2011): 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00412.x.

Wenzelburger, Georg, Pascal D. König and Frieder Wolf. “Policy Theories in Hard Times? Assessing the Explanatory Power of Policy Theories in the Context of Crisis.” Public Organizations Review 19 (2019): 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-017-0387-1

Wlezien, Christopher. “On the Salience of Political Issues: The Problem with ‘Most Important’ Problem.” Electoral Studies 24, no. 4 (2005): 555–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2005.01.009

Wolbers, Jeroen, Sanneke Kuipers and Arjen Boin. “A Systematic Review of 20 Years of Crisis and Disaster Research: Trends and Progress.” Risks, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 12, no. 4 (2021): 374–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/rhc3.12234

World Economic Forum. “The Global Risks 16th Report.” Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2021.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92