Politologija ISSN 1392-1681 eISSN 2424-6034

2022/1, vol. 105, pp. 92–132 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Polit.2022.105.3

Appeals to Human Rights in the Context of Managing the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of Government Hours in the Lithuanian Parliament in 2020–2021

Vytautas Valentinavičius

Ph.D. student and junior researcher at the Faculty of Social Sciences,

Arts, and Humanities of Kaunas University of Technology and a visiting scholar

at the University of Central Florida

Email: vytautas.valentinavicius@ktu.lt

Vaidas Morkevičius

Chief Researcher at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities

of Kaunas University of Technology

Email: vaidas.morkevicius@ktu.lt

Giedrius Žvaliauskas

Researcher at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities

of Kaunas University of Technology

Email: giedrius.zvaliauskas@ktu.lt

Monika Briedienė

Ph.D. student and junior researcher at the Faculty of Informatics

of Vytautas Magnus University

Email: monika.briediene@vdu.lt

Abstract. The securitization of the COVID-19 pandemic allowed governments in democratic countries to introduce extraordinary management measures that involved limiting various human rights. However, sound democratic governance always requires public debate on any policies introduced. These debates occur in multiple arenas and the parliament is among the most notable. In the context of human rights, some studies identified parliament as one of the most important agencies that promote human rights protection and oversee executive authorities (Lyer, 2019; Ncube, 2020). This article examines whether and how Lithuanian parliamentarians and government members addressed human rights during the Seimas debates when issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic were discussed. It investigates whether the Seimas could be considered an important agent contributing to the oversight of human rights in Lithuania. The article employs transcripts from the Seimas plenary debates as a data source, particularly speeches from the government question time from 2020.03 to 2021.01. The results of the qualitative thematic analysis revealed that human rights were generally not the main topic of the COVID-19 pandemic debates on the Seimas floor during government hours. It also showed that the attitudes of political parties toward specific human rights tended to shift when they switched from the opposition to the ruling majority and vice versa.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, human rights, political discourse, parliamentary debates, the Government Hour.

Dėmesys žmogaus teisėms COVID-19 pandemijos valdymo kontekste: Vyriausybės valandų debatų analizė Seime 2020–2021 metais

Santrauka. COVID-19 pandemijos sugrėsminimas leido demokratinių šalių vyriausybėms imtis ypatingų valdymo priemonių, ribojančių įvairias žmogaus teises. Visgi demokratiniais principais paremtas valdymas grįstas viešomis diskusijomis apie bet kokias politines iniciatyvas, kurių ėmėsi vyriausybės. Šios diskusijos vyksta įvairiose arenose, o parlamentas yra viena žymiausių iš jų, kur aptariamos politinės iniciatyvos. Žmogaus teisių kontekste kai kuriuose tyrimuose parlamentas buvo identifikuotas kaip viena svarbiausių institucijų, skatinančių žmogaus teisių apsaugą ir prižiūrinčių vykdomąją valdžią (Lyer, 2019; Ncube, 2020). Šiame straipsnyje nagrinėjama, ar ir kaip Lietuvos parlamentarai ir Vyriausybės nariai sprendė žmogaus teisių klausimus Seimo debatų metu, kai buvo svarstomi su COVID-19 pandemija susiję klausimai. Straipsnis siekia išsiaiškinti, ar Seimas galėtų būti laikomas svarbiu veikėju, prisidedančiu prie žmogaus teisių apsaugos Lietuvoje. Straipsnyje kaip duomenų šaltinis naudojamos Seimo plenarinių sesijų stenogramos, ypač kalbos Vyriausybės valandų 2020 m. kovą–2021 sausį debatų metu. Kokybinės teminės analizės rezultatai atskleidė, kad žmogaus teisės paprastai nebuvo pagrindinė COVID-19 pandemijos debatų tema Seimo salėje Vyriausybės valandomis. Tyrimas taip pat parodė, kad politinių partijų požiūris į konkrečias žmogaus teises keitėsi, kai tų partijų vieta parlamente keitėsi iš opozicijos į valdančiąją daugumą ir atvirkščiai.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: COVID-19 pandemija, žmogaus teisės, politinis diskursas, parlamento debatai, Vyriausybės valanda.

________

Received: 28/11/2021. Accepted: 01/06/2022

Copyright © 2022 Vytautas Valentinavičius, Vaidas Morkevičius, Giedrius Žvaliauskas, Monika Briedienė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The rule of law and respect for human rights are among the fundamentals of liberal democracies. However, during periods of crisis, various human rights are challenged and limited “for the better good.” The COVID-19 pandemic, identified as one of the most significant challenges since World War II, has been described as a global health crisis that requires rigorous, sophisticated, and even drastic measures to manage its consequences. For example, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, the Secretary-General of the United Nations stated that people (nations) are “at war with a virus […]. At war which cannot be dealt with by conventional means. This war needs a wartime plan to fight it.”1 When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, most countries, including Lithuania, imposed restrictions on civil, political, and economic rights (namely, freedom of movement, freedom of assembly, the right to work, etc.), some of which are among the most cherished in democracies.

However, encroachment on human rights becomes tolerable, according to the pioneers of securitization studies (Buzan et al.,2 Wæver,3 Balzacq4), when the state recognizes a particular phenomenon as a threat to national security and the society supports these measures. Indeed, wartime rhetoric was harnessed to frame the COVID-19 pandemic, and wartime metaphors were used to take the situation seriously and justify the austerity measures proposed to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.5 In Lithuania, for example, the Minister of Justice in the Lithuanian parliament stated that the legislation passed during the peace period was not suitable because people lived in wartime.6 As a result, the measures taken against the COVID-19 pandemic (including human rights restrictions) have been highly securitized. In turn, the securitization of COVID-19 gave governments extraordinary decision-making powers to address a threat to national security by limiting human rights.

However, any limitations of human rights should be reasonable and proportionate, and specific human rights cannot be restricted even during an emergency.7 There are many institutions in democratic countries (such as ombudsman institutions, human rights commissions, or constitutional and supreme courts) that monitor the internal situation of human rights, since these countries subscribe to various international acts and treaties as well as have specific basic national laws (constitutions in particular) regulating the rights of their citizens. Some scholars have also identified parliaments as human rights actors among these institutions.8 In fact, many parliaments have internal and external structures responsible for human rights oversight.

Furthermore, since the parliament is the most diverse representative institution in democracies, its members may also act as human rights protection and oversight agents. Quite a few studies focus on a parliament as an avenue contributing to the human rights agenda and an institution promoting human rights and overseeing executive authorities (see, for example, Ncube,9 Lyer10). Other studies examine the role of parliament members in human rights oversight and contestation of human rights issues in parliamentary debates as a platform for agenda-setting and policymaking.11 There is also a strand of research investigating the role of the parliamentary opposition in democratic countries, which explains that among the many functions of opposition is the preservation of democratic values, such as liberty, political equality, and the rule of law.12, 13, 14

In this article, our objective was to study the human rights that (if any) were addressed by parliamentarians and government members during debates in the Lithuanian Parliament (the Seimas) when issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic were discussed. In our analysis, we employ the full spectrum of human rights identified in the International Bill of Human Rights, namely, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CoESCR), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its two Optional Protocols (CoCPR). These are the leading human rights treaties of the United Nations, which aim to promote fundamental freedoms and protect the rights of all citizens. The regular government question time (the government hours), when preregistered parliament members (MPs) are allowed to pose (almost) any question to the Prime Minister or any minister during the publicly recorded floor debates, has been chosen to narrow the volume of the debates at the Seimas and allow for qualitative coding of the relevant content of the speeches. Furthermore, the almost free agenda of questioning in the Lithuanian Parliament allows one to grasp the pressing issues of the day, in contrast to more regularized and structured (according to the agenda of the ruling coalition) “normal” (regular) debates on the parliamentary floor.

Finally, attention to the relative differences in discursive practices (appeals to human rights) of the Government members and opposition is analyzed more closely. Special attention is paid to the discursive practices of MPs changing positions between the government and the opposition. In general, this paper focuses on whether human rights were referred to in parliamentary debates when various management measures of the COVID-19 pandemic were considered during government question time. Therefore, we investigate whether the Lithuanian parliament could be regarded as an essential avenue contributing to human rights oversight in Lithuania.

In terms of structure, the article provides a contextual background on human rights restrictions during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. It introduces the role of the parliament as an agent of protection and oversight of human rights. In addition, the article presents the data sources, coding schemes and processes, and data analysis methods. The results of the data analysis are presented and discussed later. Finally, the article provides conclusions.

COVID-19 Pandemic and Parliament as an Arena of Human Rights Oversight

Reacting to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries, including Lithuania, imposed restrictions on various civil, political, and economic rights. As the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) reports, nine EU countries declared an official state of emergency based on constitutional provisions. At the same time, the other five were in a state of emergency under their ordinary laws.15 Furthermore, thirteen additional states, including Lithuania,16 adopted emergency and restrictive measures without introducing the state of emergency specified in the constitutions, but amending existing legislation or providing a legal basis for emergency measures.17 The state of emergency granted extraordinary powers to the governments of EU states, including the discretion to make decisions related to human rights restrictions. In many EU countries, freedom of movement, the right to assembly, private and family life, and access to goods and services, education, or healthcare were restricted. For example, many states, including Lithuania, invoked border control and forced isolation of civilians returning from abroad, and other human rights restrictions to prevent the spread of disease.

Moreover, entire cities and regions were placed under quarantine (e.g., in Austria, Bulgaria, Italy, and Lithuania), or permission to leave home was required (e.g., France, Greece, Italy, and Spain). Furthermore, legal provisions under a state of emergency allowed one to forward personal data obtained by police to sanitary inspectors in Poland, and nonurgent specialized healthcare, including surgeries, was postponed in Finland, Lithuania, and many other countries. Many children of low-income families in Bulgaria were denied the right to education due to lack of access to computers and the internet.18

However, even to protect the “higher good,” human rights restrictions are not unconditional. The Venice Commission already in 2006 declared that limitations of human rights must be reasonable and proportionate, and specific human rights cannot be restricted even during an emergency.19 Similarly, Lebret20 maintains that it is of great importance to be able “to scrutinize the necessity and proportionality of government measures.” Therefore, democratic countries willing to limit human rights had to find plausible justifications. In general, securitization of issues21, 22 has become one of the essential tools for justifying the restriction of human rights in modern democracies, in which restrictions of human rights without weighing the proportionality of limitations are possible only in emergencies or for the sake of national security. As Sears23 argues, “for liberal-democratic societies, the political risks of securitization are the sacrifice of individual liberties […] for the security of society as a whole.” Securitization occurs when the problem is presented as an existential threat to national security, requiring emergency measures and justifying actions outside the ordinary political activity, and the society supports these measures. Securitization is also about reducing the timing and scope of the debate to discuss the necessity and proportionality of the measures taken.24

In the Lithuanian context, the rhetoric of securitization was also extensively used. First, the President, who is also the head of the State Defense Council, pointed out that COVID-19 has weakened our country, hampered economic and business competitiveness, and therefore threatened national security.25 This speech served as one of the first speech acts, which, according to Buzan et al.,26 was needed for an issue to be securitized. Furthermore, when introducing the amendments to the Code of Administrative Offences and the Criminal Code, which included fines and imprisonment for violations of quarantine rules, the Minister of Justice proclaimed at the Seimas that the laws that were passed in peacetime are no longer suitable, because people now live in a time of war: “[t]he laws that are in force today were adopted in peacetime. Now we have a case of war against the COVID-19 virus. We are all in no doubt that we will win this war together.”27 Furthermore, the head of the State Security Department informed the state leaders of the need to strengthen medical intelligence capabilities in response to the global COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic.28 These views have been reiterated by the head of military intelligence, guaranteeing assistance in the development of medical intelligence.29 Furthermore, these ideas were supported by a member of the Seimas Committee on National Security and Defense, the current chairman of this committee, stating that “viruses, epidemics, communicable diseases have already been part of the national security agenda since AIDS began to spread.”30

The securitization narrative launched by the previous government was echoed by the newly elected leader of the ruling majority and the Prime Minister, who noted that COVID-19 shows that the state of emergency can turn into a “crisis that poses a threat to national security.”31 Furthermore, the global COVID-19 pandemic was identified as one of the national threats in the 2021 National Threat Assessment report published by the State Security Department and the Defense Intelligence and Security Service under the Ministry of National Defense.32 Therefore, the COVID-19 pandemic was widely framed as a threat to national security, and from this time on, all measures to combat it were considered appropriate and could be legitimized. After the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in most countries, human rights derogations were explained following securitization logic. The response to COVID-19 included a referent object, namely, a threat, audiences, securitizing (speech) acts and actors, and emergency measures, which were the essential elements of securitization.33 The COVID-19 pandemic was considered a threat to national security, and wartime metaphors were used intensively.34 In particular, the securitization of COVID-19 has been studied by various scholars who examined the techniques used to justify the state of emergency,35 its sociopolitical implications on the community,36 and the impact of pandemic control measures on human rights in the long term globally.37

Studies of the latter aspect are of utmost importance, as international human rights are a vital component of the legal system of liberal democracies.38 The link between democracy and human rights is complicated, since it depends on how one defines democracy.39 There are many models and ways to define democracy40; however, the protection of human rights is an essential component of all those models that transcend the so-called “minimal” (or procedural) conception of democracy.41 The most crucial dilemma here is between two principles: the rule of the majority and the protection of fundamental rights of citizens against the will of the majority. The liberal model of democracy advocates for the primacy of protection of fundamental rights against governmental encroachment and against the will of the majority of elected representatives to limit these fundamental rights.42, 43 Human rights (and their restrictions) are generally regulated by the most important national and international legal documents, such as national constitutions, the International Bill of Human Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, and other international treaties. Furthermore, liberal democracies set up various institutions that perform the function of human rights oversight, such as ombudsman institutions, human rights commissions, or constitutional and supreme courts.

Some scholars have also identified parliaments as human rights actors among these institutions.44 Many recent studies focus on parliament as an avenue that contributes to the human rights agenda.45, 46, 47 Lyer and Webb48 maintain that “[o]verseeing and monitoring human rights in the state is the role of the parliament.” In fact, most parliaments in liberal democracies have found institutions responsible for human rights oversight. For example, the Lithuanian parliament has at least two institutions directly responsible for human rights oversight: the internal, which is the Seimas Committee on Human Rights, and the external – the Seimas Ombudspersons’ Office, which is an independent body that helps ensure the observance of human rights in the country by reporting to the Lithuanian parliament.

In exercising their powers, legislators are guided by the constitution and international human rights obligations, and these documents serve as guidelines for legislative initiatives. Webber et al.49 argue that legislators are obligated to provide a clear form of protection of human rights that reflects the fundamental human rights principles enshrined in the International Bill of Human Rights. In highlighting the role of parliaments in making institutions stronger, Chungong50 asserts that the role of parliaments is to lead debates by providing moral and social foundations. Furthermore, parliaments may employ their powers vested in national constitutions to strengthen democratic institutions and provide them with the necessary resources to fulfil their duties. Also, democratic regimes allow civil society to be a part of decision-making through inquiries, public hearings, debates in committees, and other formats. These avenues also allow parliaments to contribute to the human rights agenda. Some studies examine the role of lawmakers in bringing human rights issues into parliamentary debates.51 However, other studies investigate the role of parliamentary opposition and, among functions of opposition, identify those related to preserving democratic values, such as liberty, political equality, and the rule of law.52, 53, 54 All in all, parliaments in liberal democracies are institutions of direct oversight of human rights and act as a public space where issues related to the protection of human rights are put on the political agenda and discussed.

In this article, we examine the latter role of the parliament in bringing human rights issues to the Seimas political agenda. As the COVID-19 pandemic was highly securitized by the government, and many restrictions on human rights were imposed appealing to national security and/or public safety, we investigated to what extent the Lithuanian Parliament and different MPs assumed the role of human rights guardians in public debates, especially when confronting representatives of the government. Therefore, our study remains at the discursive level and does not attempt to assess whether parliamentary debates impacted policymaking related to combating and managing the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as already mentioned, the purpose of parliamentary debate is not only symbolic; it is also essential as an avenue of expressing public grievances, especially those represented by opposition MPs.55 Therefore, we pay special attention to the differences in discursive behavior concerning appeals to human rights between the Government members and the ruling majority MPs vs. opposition MPs. In this regard, we also investigate how the political position on specific issues of representatives of certain parties (in particular, the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union (LFGU) and the Homeland Union – Lithuanian Christian Democrats (HU-LCD)) have altered (or remained stable) when the composition of the ruling majority changed after parliamentary elections. This type of analysis would allow us to better grasp how the power position is influencing the discursive behaviour of politicians. More extensive appeals to human rights may be the only rhetorical measures employed by the opposition to blame the government for the “grave” consequences of its policies (in this case, the mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic).

Data and Methods

We used transcripts from the plenary of the Seimas debates as our data source to study appeals from MPs to human rights when discussing COVID-19 pandemic measures. However, parliamentary debates produce large amounts of textual data (speeches) that can only be analyzed by computerized means. The major problem here is that it is rather difficult for computers to identify appeals to abstract concepts, usually the main object of analysis. For example, Rooduijn & Pauwels56 report that they had to abandon measuring one of the two components of populism (people-centrism) precisely because the concept is expressed with pronouns, such as “we” or “our,” and it would be impossible to distinguish when they represent populist references. In the context of references to human rights during discussions of COVID-19 pandemic measures, it would be difficult to discern automatically (by employing computer algorithms) when pandemic management is discussed and when references to human rights are made.

Therefore, we resorted to human coding, which requires that the data for analysis (coding) be limited. Consequently, we opted to employ speeches from the government question time (the government hours) during the plenary debates on the Seimas floor. Government question time, where lawmakers ask members of the government (“government meets the opposition”), is a relatively established institution in parliaments around the world (however, mostly missing in the US Congress). Usually, MPs pose written or oral questions that must be answered by the Prime Minister or any minister during the parliamentary floor debates. Of course, some questions (especially written) are also answered in written form. However, in most cases, government question time involves live debates between lawmakers and members of the government. Some parliaments (as in Nordic countries) require that all the questions (and their contents) be reported beforehand to the Speaker; others (as, for example, in Lithuania) only require notification of intent (presented to the Speaker) to pose a question (content is not declared or scrutinized). Any MP is allowed to pose a question, and in most countries, ministers answer them (even though in most countries they are not required to respond or may answer later in written form). In Lithuania, according to Article 208 of the Statute of the Seimas,57 the government question time (the government hour) is held every Thursday (for max. an hour) when the Seimas is in session.58 Any question deemed “relevant and important for the society” can be posed, and the sitting chair decides on its relevance and importance. The opposition leader starts the questioning and is allowed to pose two questions. Then, all the other MPs are allowed to pose a question with priority given to MPs from the opposition. A question can be no longer than one minute and the answer no longer than two minutes. Therefore, institutional arrangements allow for an almost free agenda of questioning, which in turn provides following the pressing issues-of-the-day (week), in contrast to much more regularized and structured (according to the agenda of the ruling coalition) “normal” debates on the parliamentary floor.

Of course, parliamentary questions are a specific genre of speech. Questions may be information-seeking or knowledge-searching, or information-probing.59 However, questions during the government question time serve not only government control or information seeking, but also many other purposes, like improving the political profile of a lawmaker by posing a question, attacking ministers or their policies, and showing concern for some local issues in the constituencies. In particular, questions may contain presuppositions and various contextual information that reveal positions the questioning person takes or attribute blame to the person to whom the question is addressed.60 In our case, both questions and answers can be understood as statements that contain information and symbolic expression relevant to studying appeals to human rights in discussing COVID-19 pandemic measures.

During the 2016–2020 Seimas, the 17th government comprised the parliamentary election winners, the LFGU, and the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party (LSDP). Although the latter party withdrew from the ruling coalition in September 2017, two delegated ministers refused to obey the party’s will to step down and remained in office. The ruling alliance since August 2019 consisted of the LFGU, the Lithuanian Social Democratic Labor Party (LSDLP), Order and Justice (OJ), and the Lithuanian Polish Electoral Action, the Union of Christian Families (EAPL-CFA). After the Seimas elections in 2020, the Homeland Union – Lithuanian Christian Democrats (HU-LCD) (50 MPs), which won the most seats, formed a coalition with the liberal political forces, the Liberal Movement of the Republic of Lithuania (LMRL) (13 MPs) and the Freedom Party (FP) (11 MPs). On 7 December 2020, the President approved the composition of the 18th government headed by the appointed Prime Minister I. Šimonytė, and the Government of S. Skvernelis completed its work. In the new government, the HU-LCD received ten positions (including the Prime Minister), the LMRL 3 positions, and the FP 2 positions.

In total, there were 20 government hours during the study period (starting from 10 March 2020, just before the COVID-19 pandemic-related quarantine was first imposed in Lithuania and ending on 14 January 2021, the last plenary sitting of the first session of the newly elected parliament). Government hours contained 1238 speeches divided into paragraphs; most of the questions and answers during a government hour span one paragraph. However, some speeches include two questions or two different aspects of the same question, answered one by one. Therefore, we opt for paragraphs (as identified by the Seimas stenographers) as our coding units (for a similar strategy, see Rooduijn & Pauwels61).

Furthermore, we included only those paragraphs in the analysis in which the main topic was the COVID-19 pandemic and its containment measures (N=549).62 Information about the government hours sample, the distribution of paragraphs and documents according to the year/month, and whether the main topic of the paragraph is the COVID-19 pandemic is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics about the sample selected for the analysis.

|

Government |

Year and month |

Main topic: COVID-19 pandemic (%) |

N (paragraphs in speeches/questions, excluding speeches of the Speaker of the Seimas) |

N |

|

|

No |

Yes |

||||

|

XVII government |

2020–03 |

7.61 |

92.39 |

92 |

1 |

|

XVII government |

2020–04 |

30.47 |

69.53 |

128 |

2 |

|

XVII government |

2020–05 |

53.74 |

46.26 |

281 |

4 |

|

XVII government |

2020–06 |

72.84 |

27.16 |

232 |

4 |

|

XVII government |

2020–09 |

65.55 |

34.45 |

119 |

2 |

|

XVII government |

2020–10 |

85.86 |

14.14 |

99 |

2 |

|

XVII and XVIII government |

2020–11 |

69.05 |

30.95 |

84 |

2 |

|

XVIII government |

2020–12 |

21.57 |

78.43 |

51 |

1 |

|

XVIII government |

2021–01 |

59.87 |

40.13 |

152 |

2 |

|

Total |

55.65 |

44.35 |

1238 |

20 |

|

References to COVID-19 pandemic subtopics and references to human rights identified in CoCPR and CoESCR were hand-coded for presence in each paragraph. Each paragraph could contain more than one reference to the topic of the COVID-19 pandemic and the human rights article. The coding in both cases was performed using MAXQDA qualitative data analysis software (version 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic subtopics discussed during the government hours were identified inductively. First, coding categories representing these subtopics were developed using data-driven thematic coding on the entire corpus of government hours texts with the main topic related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Coding at this stage was performed by a single researcher seeking coding stability. The entire corpus was used for the first stage, since subtopics related to the COVID-19 pandemic developed over time. In the second stage, another researcher coded randomly selected 100 paragraphs from the whole sample with the expanded categories of the COVID-19 pandemic subtopics. In the last stage, the two coded sets of data were compared and resolved in cases where the coding did not match. Additionally, the coding of the rest of the paragraphs was amended in the case of similar inconsistencies. A complete list of the categories of COVID-19 pandemic subtopics (22 in total) is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Subtopics of the COVID-19 pandemic identified in MP speeches during the government hours of the analyzed period.

|

• Military Use • Spread of the virus within the country • Regulation of prices • Lessons from the first wave and preparation for the second wave • Credits and borrowing • EU support (financial, etc.). • Plans to combat the COVID-19 pandemic • Personal responsibility and responsible behavior • Restrictions on public events • Effects on people and society • Support and consultation from experts |

• Crisis and crisis management communication • Effects on business and budget • Bringing the virus from abroad • Introduction to the emergency situation • Effects on risk groups • Effects on public health • Restrictions on social contacts and movement • Problems related to support and other measures • COVID-19 prevention, treatment of the disease, and its consequences • Restrictions on personal, institutional, and business activities • Government support for various sectors |

References to human rights were coded according to articles 6–27 of the CoCPR and articles 6–15 of the CoESCR. We selected these two documents because they are among the most important ones that regulate the political, social, cultural, and economic rights of citizens in democratic countries. International agreements also have a special place in the Lithuanian legal system. The Constitutional Court emphasizes that “the observance of international obligations undertaken on its own free will, concerning universally recognized principles of international law (as well as the principle pacta sunt servanda) is a legal tradition and a constitutional principle of the restored independent state of Lithuania.”63 Coding was performed following the logic of theory-driven thematic coding.64 In the first stage, one of the authors coded the entire corpus of the Government Hours texts with the main topic related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the second stage, another researcher coded 100 randomly selected paragraphs from the entire sample. In the last step, the two coded sets of data were compared,65 discussed, and the coding of individual paragraphs was amended in the cases of inconsistencies (also for the entire sample). The categories representing separate human rights articles from the CoCPR and the CoESCR with abbreviations used in the graphs are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Coding categories representing human rights from CoCPR and CoESCR.

|

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CoCPR) |

International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CoESCR). |

||||

|

Article |

Topic |

Abbreviations |

Article |

Topic |

Abbreviations |

|

6 |

The right to life |

Life |

6 |

The right to work (work) |

To work |

|

7 |

The right not to be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment |

No torture |

7 |

The right to just and favorable conditions of work |

Work conditions |

|

8 |

The right not to be enslaved or otherwise trafficked. |

No enslavement |

8 |

The right to form and join trade unions |

Trade unions |

|

9 |

The right to the integrity of the person |

Personal integrity |

9 |

The right to social security |

Social security |

|

10 |

The right of persons deprived of their liberty to humanity and respect for their dignity |

Dignity |

10 |

The right to start a family and to the protection of it |

Family protection |

|

11 |

The right not to be deprived of liberty for failure to fulfill a contractual obligation |

Contractual |

11 |

The right to an adequate standard of living |

Living standard |

|

12 |

The right to move freely and to choose a place of residence |

Free movement |

12 |

The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health |

Health |

|

13 |

The right of foreigners to a lawful expulsion process |

Expulsion |

13 |

The right to education and the full development of the human personality |

Education |

|

14 |

The right to a fair trial |

Fair trial |

14 |

The right to primary education |

Primary education |

|

15 |

Protection of the principle of “there is no punishment without law”. |

Fair penalty |

15 |

The right to participate in cultural life and enjoy the benefits of scientific progress |

Culture and science |

|

16 |

The right to be a legal subject |

Legal subject |

|||

|

17 |

The right to protection of private life: the inviolability of the home, the secrecy of correspondence, the protection of honor and dignity |

Privacy |

|||

|

18 |

The right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion |

Free thought |

|||

|

19 |

The right to self-expression, adherence to personal beliefs |

Free self-expression |

|||

|

20 |

The right not to suffer incitement to national, racial, or religious hatred, prohibition of war propaganda |

No hatred |

|||

|

21 |

The right to peaceful assembly |

Peaceful assembly |

|||

|

22 |

The right to join associations and to form trade unions |

Free association |

|||

|

23 |

The right to family protection |

Family |

|||

|

24 |

The right of minors to protection from discrimination |

Minors |

|||

|

25 |

Right to participate in public affairs: the right to vote, to enter civil service (public affairs) |

Participation |

|||

|

26 |

The right to equal protection before the law |

Legal equality |

|||

|

27 |

The right of national minorities to foster their culture, to practice religion and language. |

Cultural freedom |

|||

In terms of data analysis, we resort mainly to quantitative descriptive statistics, showing relative distributions of appeals to human rights in the Seimas debates during the government hours. We offer two types of relative distributions: 1) per speech (paragraph), that is, how frequently each speech (paragraph of the speech) of an MP or minister (when the main topic of that speech was the COVID-19 pandemic) contained an appeal to specific human rights of the CoCPR and CoESCR, and 2) per government hour, that is, we register if the whole debate during the government hour contained any references to human rights of the CoCPR and CoESCR. Furthermore, we show the relative distributions of appeals to human rights in speeches by lawmakers representing government and opposition parties. Finally, we provide excerpts from the debates, which illustrate how the appeals to human rights were framed in the government hour debates in the Seimas.

Results

In spring 2020, the introduction of extraordinary measures, a state-level emergency,66 and a quarantine regime – to combat the threat of COVID-19 – received little resistance in the Seimas. On the contrary, these measures were introduced as unavoidable instruments in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, the introduction of a quarantine resulted in limiting human rights, such as the prohibition of public events and gatherings of more than two people; a ban for Lithuanian nationals from leaving the country; all elective surgeries were postponed; primary outpatient personal health care services were provided only by phone; compulsory and enforced two-week isolation of persons returning from abroad was imposed. Furthermore, the right to enjoy freedom of assembly, education, and the right to engage in business or commercial activities was limited (in specific sectors, mainly catering and non-food merchandise). Data protection was compromised because there was no information on how the government will process personal data collected from returning people, those diagnosed with COVID-19 or those forced to be tested, how long it will be stored, and when it will be destroyed.

In parliamentary debates, these measures and human rights restrictions were securitized, since the COVID-19 pandemic was presented as a threat to public health that needs to be protected. The interior minister stressed that an emergency state and quarantine were introduced to protect public health at a government hour. One of the opposition leaders appreciated the government’s efforts to protect public health. Therefore, both government and opposition leaders saw the COVID-19 pandemic as a threat to public health and national security. However, the measures designed to combat the COVID-19 pandemic imposed on the society resulted in criticism from human rights experts when applied in practice. As Dagilytė et al.67 pointed out, while the state of emergency allows the Seimas or the President to temporarily restrict human rights, such as the right to privacy, the right to housing, or freedom of expression, “quarantine requires that limitations be provided by law, comply with principles of necessity and proportionality, and pursue a legitimate goal, which varies depending on the right in question.” Furthermore, the Seimas Ombudsperson criticized some of the introduced emergency management measures, indicating that they do not comply with international human rights treaties, namely the enforced isolation of people returning from abroad, compulsory hospitalization of infected people for up to one month without a court decision, and a decision to postpone all non-life-threatening health care services, including elective surgeries.68 Therefore, it is essential to investigate whether (and how) any of the Lithuanian parliamentarians advocated for human rights issues when they debated measures taken to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and whether the Seimas (and its members) acted as a human rights agent.

An analysis of the Seimas debates during government hours revealed that the extraordinary measures proposed by Lithuanian governments to combat the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in more extensive discussions in parliament. From Table 1, we see that the topic of the COVID-19 pandemic dominated in March and April 2020 during the government hours when the XVII government was in office. Later, up until the first government hour of the newly appointed government, other topics prevailed during government hour. However, during the only government hour in December 2020 (when the second quarantine was imposed in Lithuania), the COVID-19 pandemic was again the most important topic on the agenda.

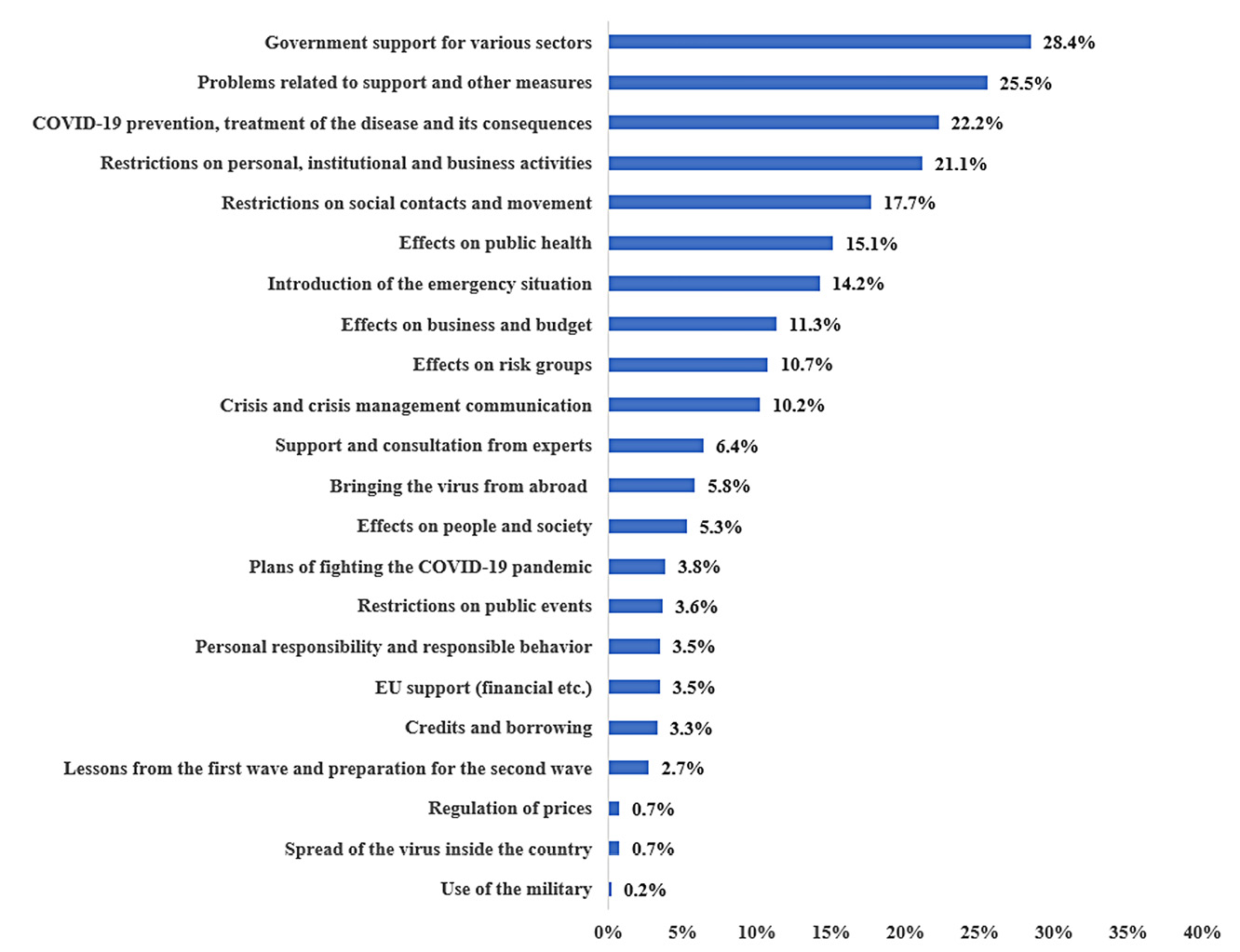

Looking at the results of the analysis of the subtopics of the COVID-19 pandemic during government hour debates, we can see that the MPs (and ministers) were primarily concerned with different socioeconomic issues and government help for those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (28.4 percent of all speeches (paragraphs) were related to this subtopic, see Figure 1). The other highly discussed subtopics were related to problems of governmental support and other measures (25.5 percent), medical prevention of the COVID-19 pandemic (22.2 percent), restrictions on personal, institutional, and business activities (21.1 percent), as well as restrictions on social contacts and movement (17.7 percent). In particular, various limitations directly related to the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic and fundamental human rights (activities of individuals, institutions, businesses, social contacts, and movement) were frequently discussed during government hours during the studied period. However, other restrictions, such as the prohibition of public events, were rarely mentioned (3.6 percent of all speeches (paragraphs) were related to this subtopic, see Figure 1) by the lawmakers (and ministers) during the analyzed debates.

Figure 1: Subtopics of the COVID-19 pandemic mentioned during government hours in the Seimas 12.03.2020–14.01.2021 (percent of the paragraphs with the main topic of the COVID-19 pandemic, N=549).

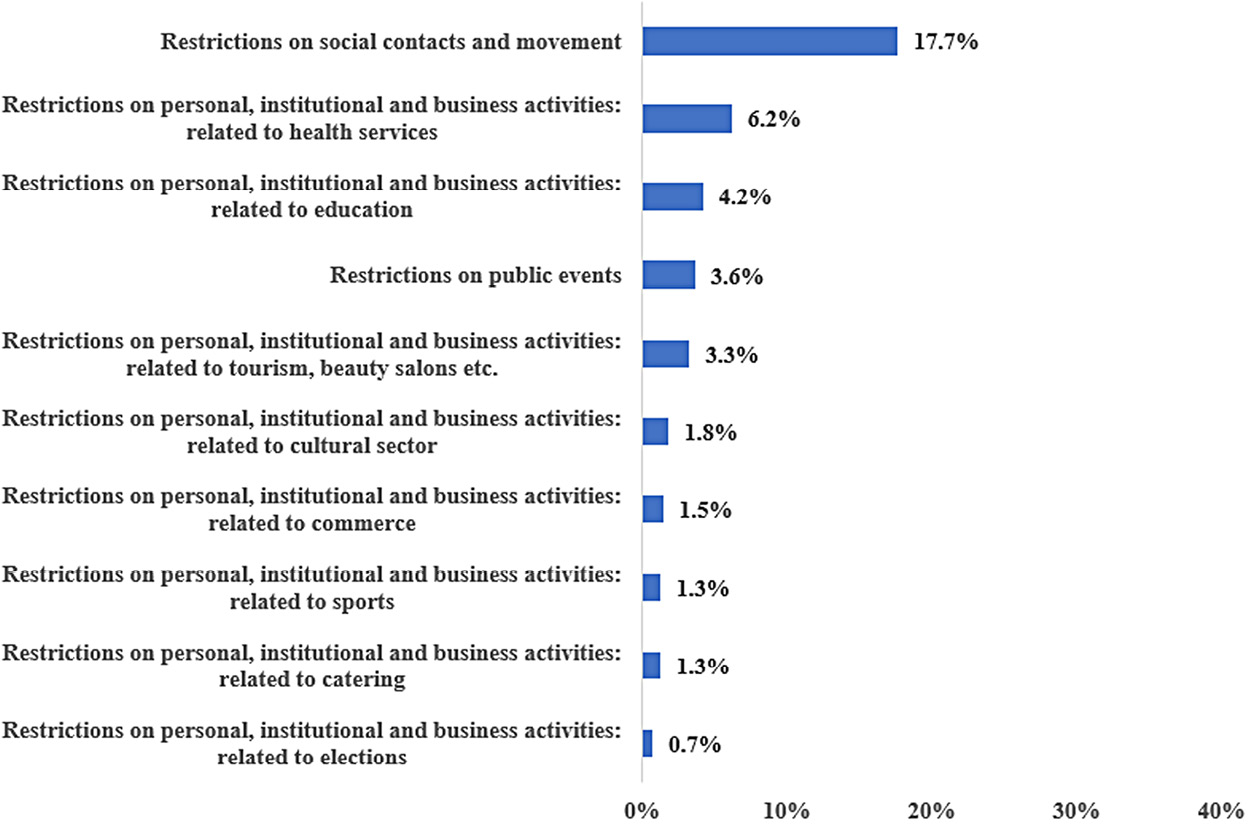

Furthermore, we analyze the subtopics most directly related to various restrictions resulting from COVID-19 pandemic management measures (see Figure 2). An analysis of government hour debates revealed that parliament members and ministers most frequently discussed restrictions on social contacts and movement (17.7 percent). Furthermore, they quite often referred to restrictions on personal, institutional, and business activities related to health services (6.2 percent of total speeches) and education (4.2 percent of all speeches), and restrictions on public events (mentioned in 4.2 percent of speeches) (see Figure 2). Other restrictions were discussed less frequently, and limitations related to the coming parliamentary elections were mentioned only four times (0.7 percent of all speeches).

Figure 2: COVID-19 management measures related to human rights restrictions discussed during government hours in the Seimas on 12.03.2020–14.01.2021 (percent of paragraphs with the main topic of the COVID-19 pandemic, N=549).

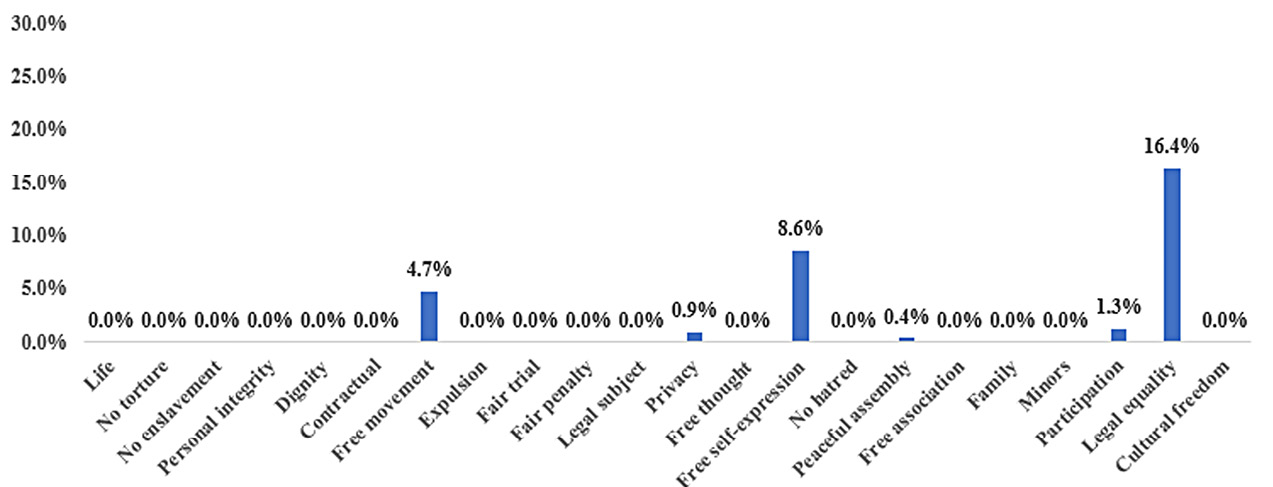

Furthermore, we investigate the frequencies of appeals to human rights identified in CoCPR and CoESCR. From Figures 3a and 3b, we can see that various civil and political rights of the CoCPR have not been at the center of the debates during the government hour. If we look at the relative frequency of mentions during the government hours, only two of these rights were mentioned at least once in three out of four government hours: the right to equal protection before the law (legal equality) and the right to self-expression, adherence to beliefs (free self-expression). Rights related to free movement, privacy, peaceful assembly, and participation in public life were mentioned on some occasions (in two to seven government hours of the twenty analyzed). And the rest of the rights (sixteen out of twenty-two) were not mentioned in the debates. Of course, not all human rights were within the scope of the COVID-19 management measures, so there was no need for the parliament to focus specifically on them. However, the focus on only certain human rights might partially be explained by the fact that lawmakers may have discussed the most burning and worrying rights for Lithuanians. For example, a public poll of almost 800 Lithuanian residents conducted at the beginning of December 2020 on social networks, asking which rights were most affected by restrictions imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, showed that restrictions on the right to health (33 percent) and restrictions on freedom of movement (30 percent) were mentioned by the population more frequently.69

Figure 3a: Mentions of topics related to separate articles of the CoCPR during government hours in the parliament on 12.03.2020–14.01.2021 (percent of the paragraphs with the main topic of the COVID-19 pandemic, N=549).

Figure 3b: Mentions of topics related to separate articles of the CoCPR during the government hours in the parliament on 12.03.2020–14.01.2021 (percent from separate government hour debates, N=20).

However, in terms of the frequency of mentions in separate speeches (paragraphs), appeals to the human rights of the CoCPR have been even less prevalent. The most frequently mentioned human right related to legal equality was in only one of six speeches made by lawmakers or ministers during government hours. The right to self-expression and adherence to beliefs (free self-expression) was mentioned in less than one out of ten speeches, and the right to move freely and choose a place of residence (free movement) was mentioned in less than one out of twenty speeches. The rest of the human rights mentioned were even less frequent. As already mentioned, protecting the right to free movement70 was one of the biggest concerns of Lithuanian residents. Furthermore, since freedom of movement, freedom of expression, and equality before the law are constitutional rights, the limitations of these rights might have attracted particular concern. In addition, since constraints on these rights have affected a large part of the society, the parliament may have purposefully paid more attention to them.

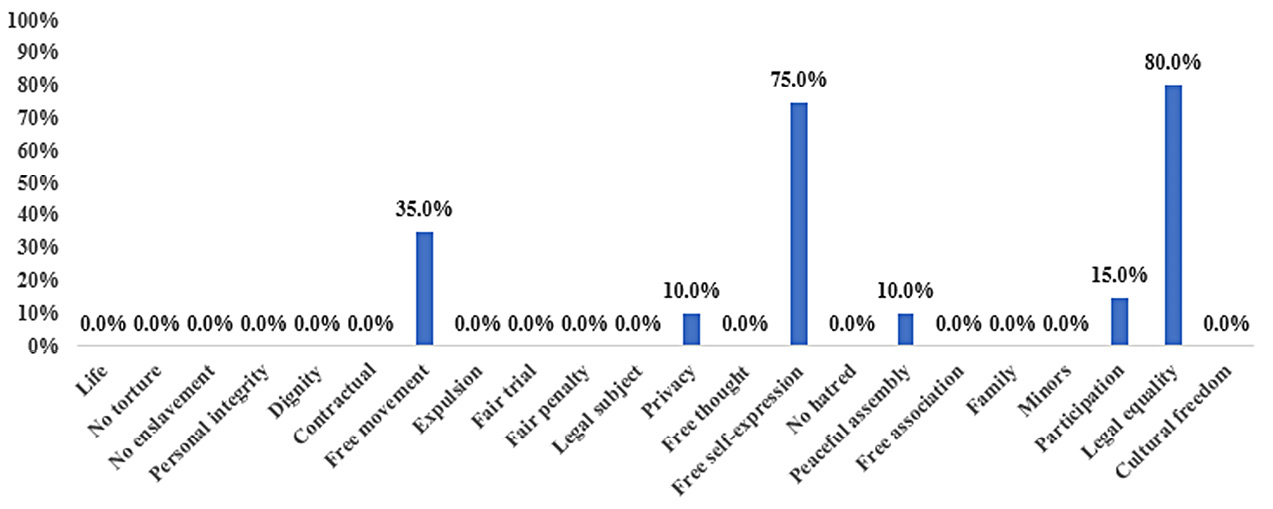

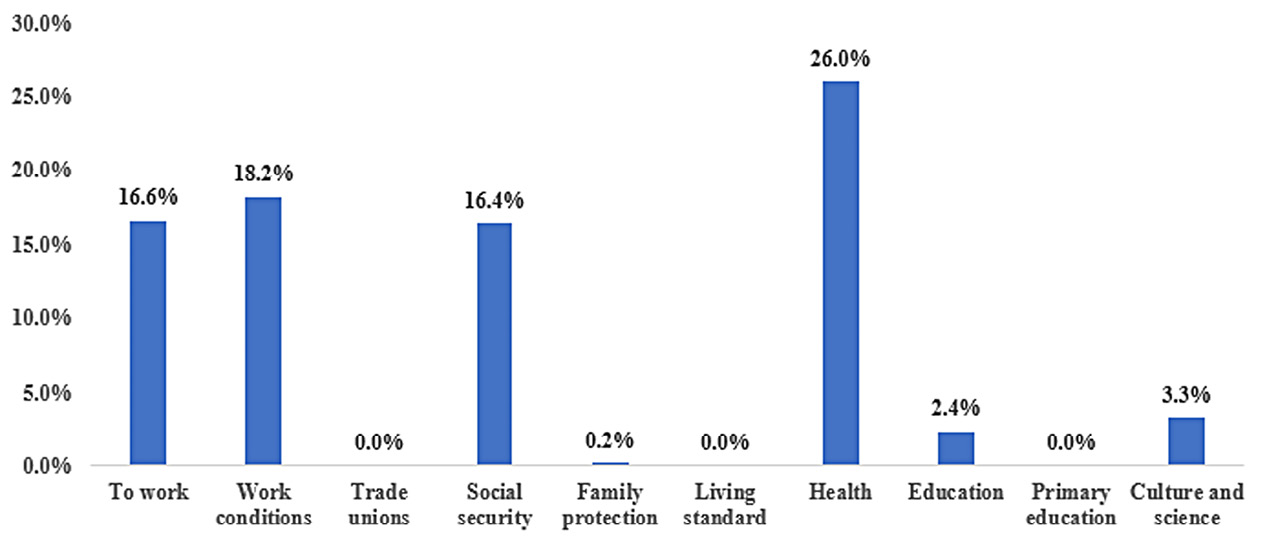

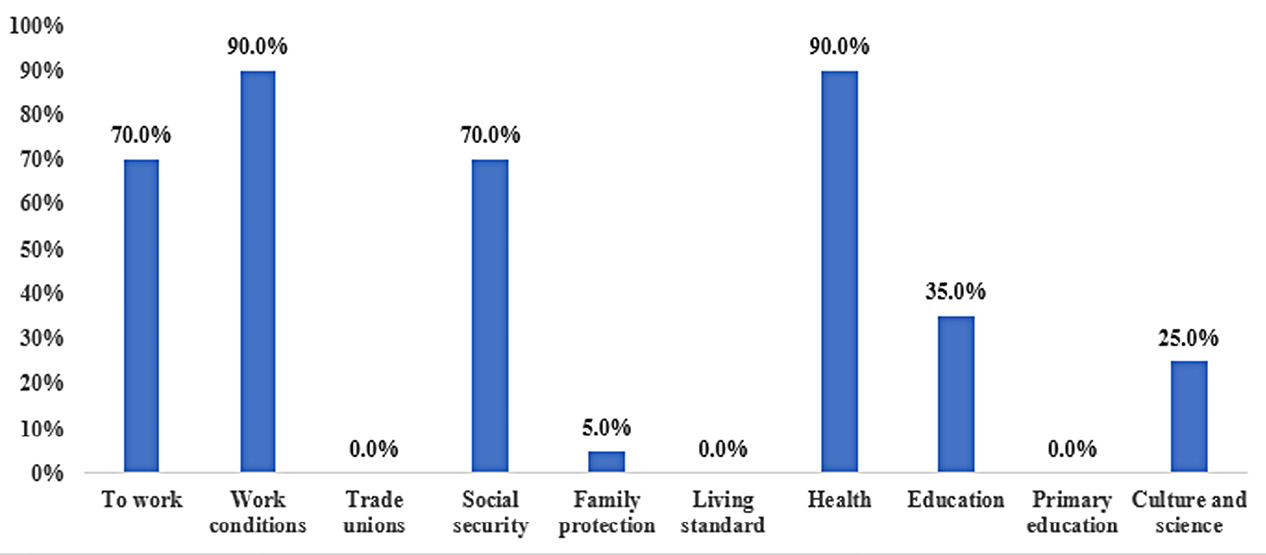

The analysis of the government hour debates also revealed that among the CoESCR rights, the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (26 percent from total speeches), the right to the enjoyment of just and favorable conditions of work (18.2 percent), or the right to social security (16.4 percent) were at the center of parliamentary debates. In comparison, the right to education (2.4 percent) or the right to participate in cultural life (3.5 percent) has received significantly less attention (see Figure 4a). However, suppose that one looks at how frequently the CoESCR rights were mentioned not in separate speeches but during the entire government hours when discussing the COVID-19 pandemic; in that case, the results show that at least some human rights (among the CoESCR rights) were discussed during almost all government hours.

Figure 4a: Mentions of topics related to separate articles of the CoESCR during government hours in the parliament from 12.03.2020 to 14.01.2021 (percent of the paragraphs with the main topic COVID-19 pandemic, N=549).

For example, the right to enjoy just and favorable conditions of work was mentioned at least once in eighteen out of twenty government hours, or the right of everyone to enjoy the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health was mentioned at least once in eighteen out of twenty government hours. However, other human rights (among the CoESCR rights) received less attention – for example, the right to participate in cultural life (mentioned at least once in five of the twenty government hours) (see Figure 4b).

Figure 4b: Mentions of topics related to separate articles of the CoESCR during government hours in the parliament on 12.03.2020–14.01.2021 (percent of separate government hour debates, N=20).

The results of the analysis show that the Lithuanian parliament specifically targeted the human rights that were most directly related to COVID-19. That is, the management measures of the COVID-19 pandemic affected certain rights more seriously than others, such as social security (for example, people became less socially secure because the management measures of COVID-19 imposed restrictions on certain businesses), or the enjoyment of some rights became more difficult (for example, health services were more readily available for the upper class of society, since they could afford private health services). On the other hand, the parliament has been criticized for paying little attention to specific human rights, such as the protection of the family, as families have faced problems not only in caring for the well-being of their members but also in engaging in the education of children or maintaining the work-life balance, as many family providers were forced to work from home because of teleworking conditions being massively introduced in the labor market. However, this burden affected women more than men (European Parliament, 2022).71

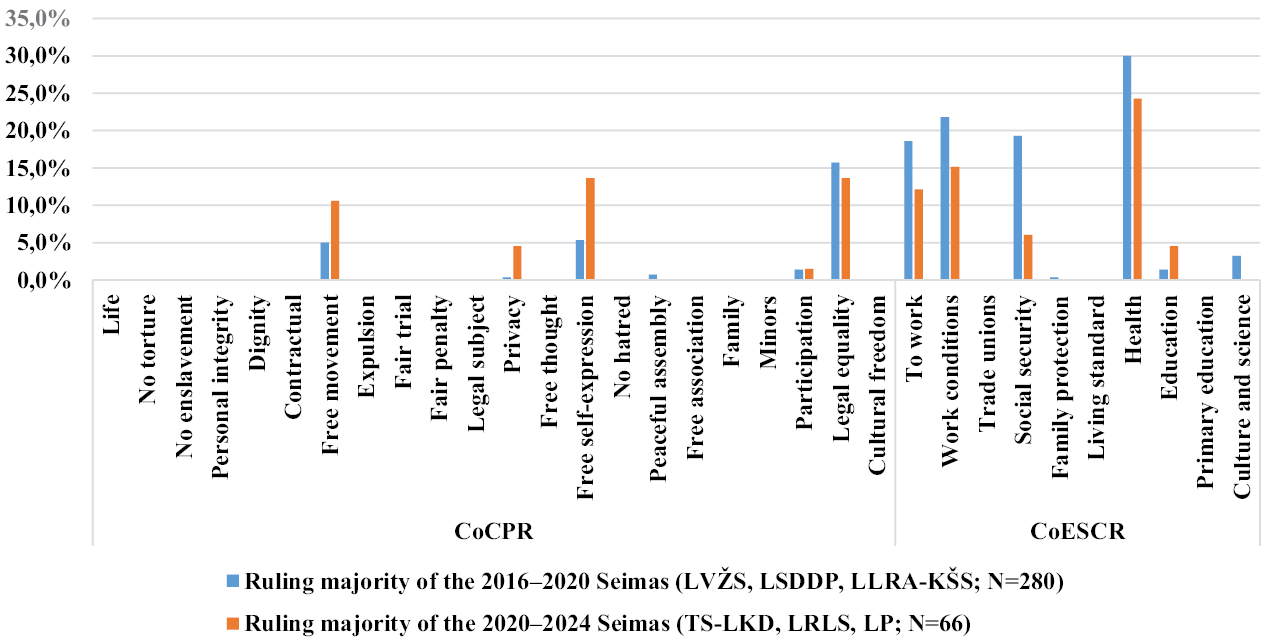

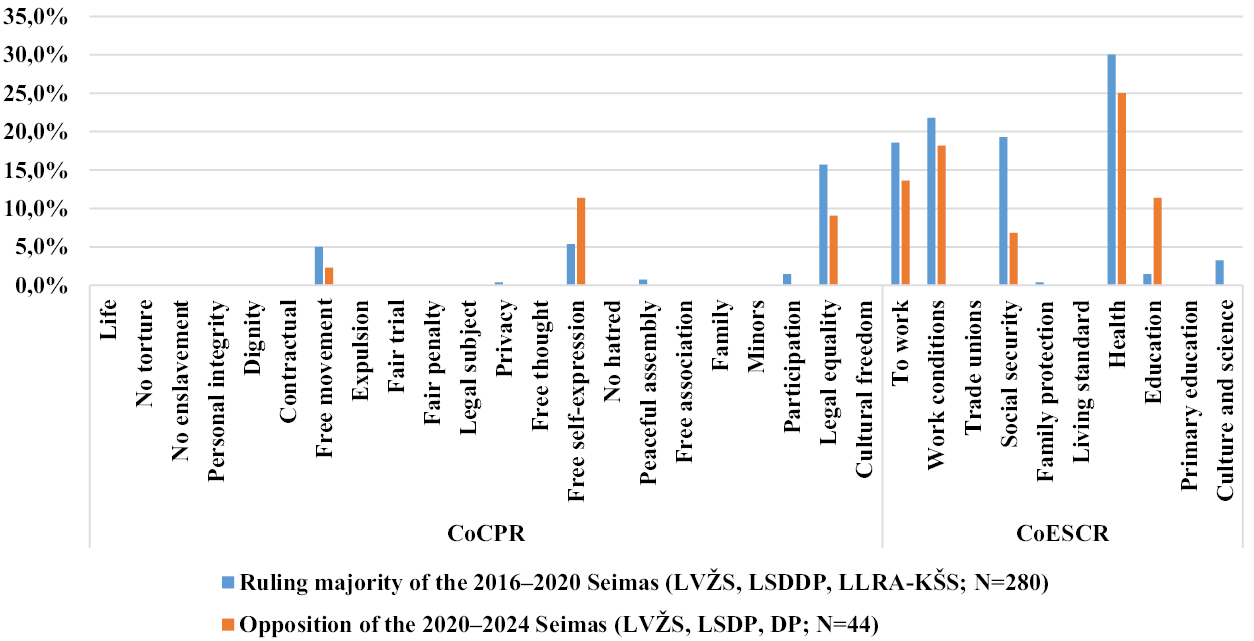

Next, we examine the relative distributions of appeals to human rights by representatives of the ruling majority and opposition factions. First, in Figure 5, we see that members of parliament and ministers of different ruling majorities paid primary attention to the same human rights issues even during different COVID-19 pandemic management periods. However, some human rights received more attention from the ruling majority in the Seimas of 2016–2020 than in the Seimas of 2020–2024 when the issues of COVID-19 were discussed. In particular, the right to social security, the right to work, the right to just and favorable work conditions, and the right to enjoy the highest possible standard of physical and mental health received more attention from the previous ruling majority than from the incumbent one. On the other hand, the right to move freely, the right to self-expression, the right to the protection of private life, and the right to education were mentioned much more frequently by the incumbent ruling majority only (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Mentions of topics related to separate articles of the CoCPR and CoESCR during government hours at the parliament by lawmakers representing the ruling majority parties from 12.03.2020 to 14.01.2021.

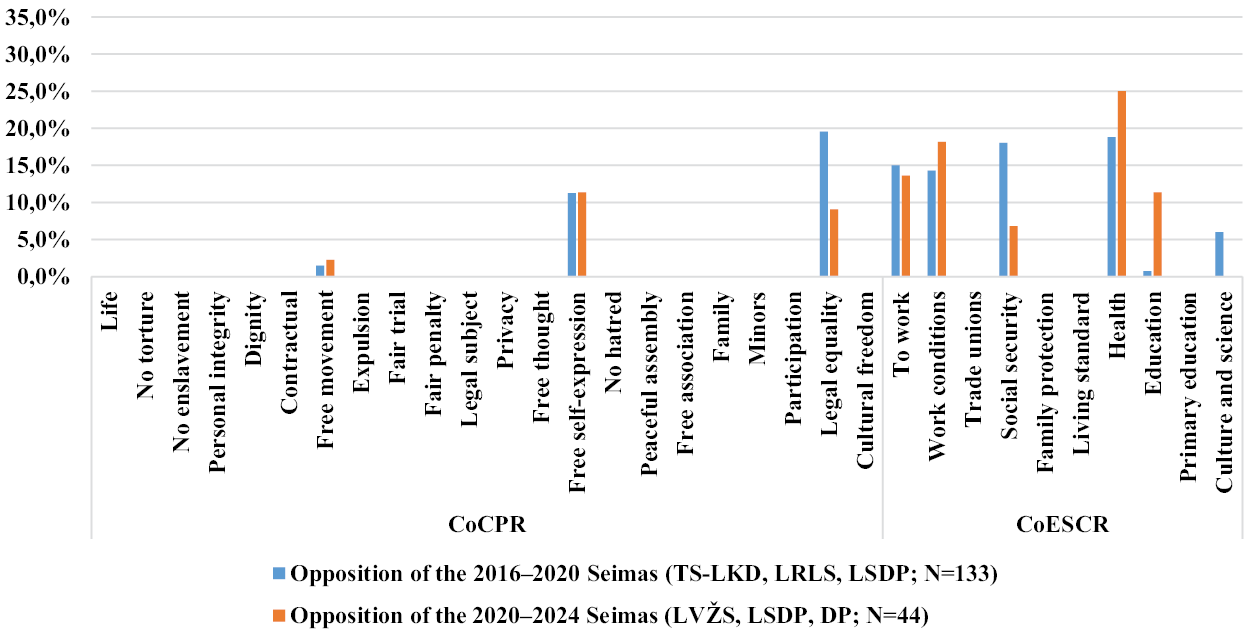

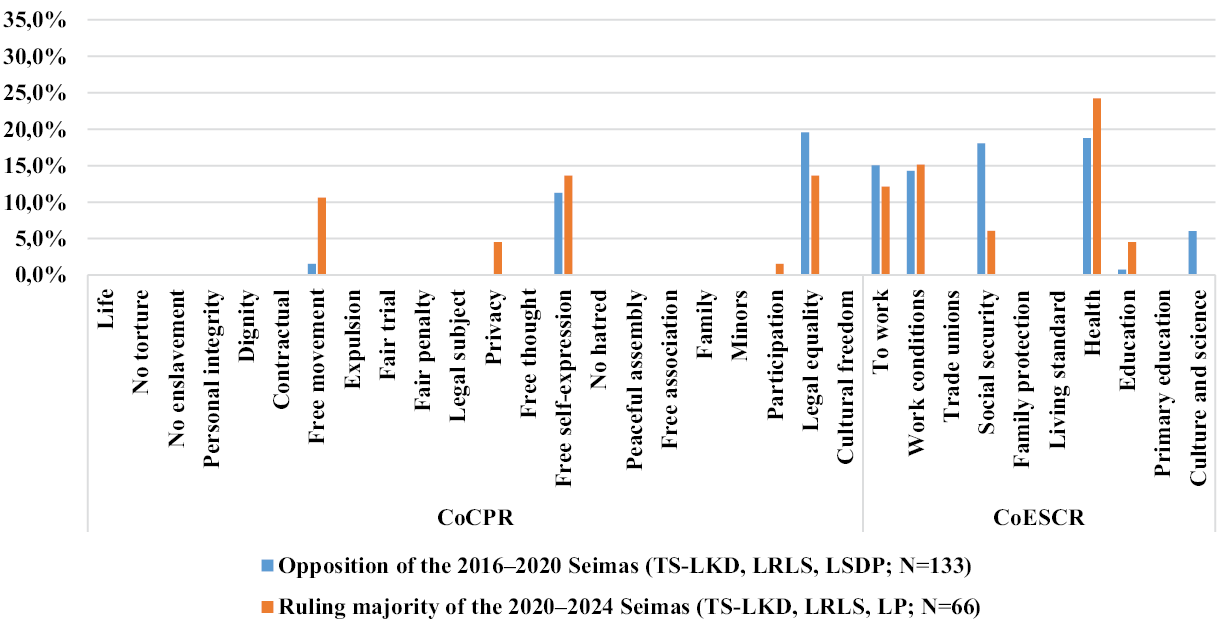

Furthermore, Figure 6 reveals that opposition in the Seimas of 2020–2024 focused more on the right to education and the full development of the human personality. This human right received little attention from the opposition in the 2016–2020 Seimas. Furthermore, the right to the highest possible standard of physical and mental health and the right to just and favorable work conditions were relatively more important to the opposition in the 2016–2020 Seimas when issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic were debated during government hours. However, equality before the law, the right to participate in cultural life and enjoy the benefits of scientific progress, and the right to social protection received much more attention from the opposition in the Seimas of 2016–2020 (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Mentions of topics related to separate articles of the CoCPR and CoESCR during government hours at the parliament by lawmakers representing opposition parties from 12.03.2020 to 14.01.2021.

Data analysis also revealed a shift in the attention of parties to specific human rights as they were in the ruling majority (opposition) during the 2016–2020 Seimas and in the opposition (ruling majority) during the 2020–2024 Seimas (see Figures 7a and 7b). The most apparent shifts of attention can be seen concerning the right to self-expression, the right to equal protection before the law, the right to social security, the right to education, and the full development of the human personality. The opposition of the 2020–2024 Seimas (representatives of the LFGU, LSDP, and the LP) discussed more frequently the right to equal protection before the law and the right to social security as compared to the ruling majority of the 2016–2020 Seimas (representatives of the LFGU, LSDLP, and EAPL-CFA). However, the opposition of the Seimas 2020–2024 paid more attention to the right to education and the full development of the human personality and the right to self-expression than the ruling majority of the Seimas of 2016–2020 (see Figure 7a).

Figure 7a: Mentions of topics related to separate articles of the CoCPR and CoESCR during the government hours at the Seimas by MPs representing the ruling majority parties in the 2016–2020 Seimas and opposition parties in the 2020–2024 Seimas.

The data also showed that the ruling majority of the 2020–2024 Seimas (representatives of TS-LKD, LRLS, and LSDP) was more focused on the right to move freely, the right to privacy, the right to the highest level of physical and mental health, and the right to education as compared to the opposition of the 2016–2020 Seimas (representatives of TS-LKD, LRLS, and LP). On the other hand, the right to social protection, the right to participate in cultural and scientific life, and the right to equal protection before the law received more attention from the opposition of the Seimas of 2016–2020 as compared to the ruling majority of the Seimas of 2020–2024 (see Figure 7b).

Figure 7b: Mentions of topics related to separate articles of the CoCPR and CoESCR during the government hours at the Seimas by MPs representing the opposition in the 2016–2020 Seimas and the ruling majority in the 2020–2024 Seimas.

In summary, data analysis revealed that most of the human rights identified in CoCPR and CoESCR were rarely discussed during government hours in the Lithuanian parliament when talking about issues related to COVID-19, and some were completely ignored. Data analysis showed that only human rights related to the highest attainable standards of physical and mental health, social security, work, just and favorable conditions of work, and equal protection before the law were relatively more frequently mentioned in COVID-19 topics. In particular, the center-left ruling majority of the 2016–2020 Seimas focused more on social and economic rights. The center-right-governing majority formed after the 2020–2024 Seimas elections appealed to civic freedoms relatively more frequently. This seems to be related to the composition of the government coalitions. However, if we look at the appeals to human rights by opposition MPs during the 2016–2020 and 2020–2024 Seimas, we see entirely different trends, as opposition representatives in the 2016–2020 Seimas mentioned rights related to social security more frequently than opposition MPs in the Seimas of 2020–2024. We look at the context of the latter appeals to the rights to social security. We found that the opposition in the Seimas of 2016–2020 mentioned rights to social security primarily when discussing the effects of the management of the COVID-19 pandemic, while the opposition in the Seimas of 2020–2024 also mentioned these rights in the context of vaccination. Overall, the latter finding shows that the discursive ruling majority-opposition interplay in the Seimas is (at least partially) influenced by the attempts of the MPs to present their positive political profiles and show concern for the pressing issues of the day.72

Conclusions

Framing the COVID-19 pandemic as a threat to public health and national security opened a window of opportunity for politicians to seek extraordinary measures to address this threat. The securitization of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a derogation of human rights, which are cherished and protected in liberal democracies in ordinary situations. Both governments considered COVID-19 a threat to national security, so the limitations of human rights, namely freedom of assembly, right to movement, right to quality health services, and right to engage in business activities were supported by ruling majorities; however, they were not challenged by the opposition. The securitization of the COVID-19 pandemic encouraged the government to shape the discourse of the COVID-19 pandemic as a threat to national security, thus ignoring the public debate and unequivocally promoting the only way to combat the pandemic without seeking alternative measures, but framing the general opinion that the proposed measures are the only ones available.

The analysis revealed that, in general, human rights were not a frequent accompanying topic in the COVID-19 pandemic debates on the Seimas floor during the government hour. Thus, we can hardly say that the parliament acted as an agent of human rights during the analyzed period. It appears that only human rights related to the highest attainable standards of physical and mental health, social security, work, just and favorable conditions of work, and equal protection before the law were relatively more frequently mentioned in the COVID-19 debates. Even if some human rights were discussed during the government hour, others, such as the right to participate in public affairs and the right to be protected from unlawful interference with individual privacy, family, home, or correspondence, received little attention. In particular, even the opposition (primary agent of the criticism for the government representatives) ignored certain human rights, even though human rights experts have expressed concerns about them. In particular, the right to freedom of movement and the right to peaceful assembly did not reach the horizon of the opposition.

The analysis also revealed that the attitudes of political parties toward specific human rights tended to shift when they switched from the opposition to the ruling majority and vice versa. Specifically, the center-left ruling majority of the Seimas of 2016–2020 focused more on social and economic rights. The center-right-governing majority formed after the 2020–2024 Seimas elections relatively more frequently appealed to civic freedoms. However, opposition representatives in the Seimas of 2016–2020 mentioned human rights related to social security more frequently than opposition MPs in the Seimas of 2020–2024. Identified shifts of the focus on human rights, depending on the power position in the parliament, may be interpreted as showing that without decision-making powers and without taking responsibility for decisions, representatives of opposition parties are less constrained in their debate topics and are prone to appeal to values (human rights in our case) that are, first of all, deemed pleasing to more significant segments of the society (this may be illustrated by appeals to social security rights by the right-leaning parties).

References

Ahrens, Petra, Barbara Gaweda, and Johanna Kantola. “Reframing the Language of Human Rights? Political Group Contestations on Women’s and LGBTQI Rights in European Parliament Debates.” Journal of European Integration 10 (2021): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2021.2001647.

Apter, D. E. “Some Reflections on the Role of a Political Opposition in New Nations.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 4, no. 2 (January 1962): 154–68. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0010417500001316.

Arat, Zehra F. “Human Rights and Democracy: Expanding or Contracting?” Polity 32, no. 1 (September 1999): 119–144. https://doi.org/10.2307/3235336.

Bächtiger, A. “Debate and Deliberation in Legislatures.” In The Oxford Handbook of Legislative Studies, edited by Shane Martin, Thomas Saalfeld, and Kaare W. Strøm, 126–144. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Balzacq, Thierry. “A Theory of Securitization: Origins, Core Assumptions, and Variants”. In Understanding Securitisation Theory: How Security Problems Emerge and Dissolve, edited by Thierry Balzacq, 1–30. Routledge, 2010.

Beniušis, Vaidotas. „Karinės žvalgybos vadovas: galime padėti vystyti medicininę žvalgybą“ (interviu). Kauno diena, 1 June 2020. https://kauno.diena.lt/naujienos/lietuva/salies-pulsas/karines-zvalgybos-vadovas-galime-padeti-vystyti-medicinine-zvalgyba-interviu-970105.

Boyatzis, Richard E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. SAGE, 1998.

Buzan, Barry, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998.

Chungong, M. “Parliaments as Promoters of Human Rights, Democracy, and the Rule of Law”, 2018 Forum on Human Rights, Democracy, and the Rule of Law, 22 November 2018“. Inter-Parliamentary Union, 18 November 2018. https://www.ipu.org/documents/2018-11/parliaments-promoters-human-rights-democracy-and-rule-law-2018-forum-human-rights-democracy-and-rule-law-22-november-2018.

Constitutional Court of the Republic of Lithuania. “On the Limitation of Ownership Rights in Areas of Particular Value and in Forest Land, Case No. 17/02-24/02-06/03-22/04”. Lrkt.lt, 14 March 2006. https://www.lrkt.lt/en/court-acts/search/170/ta1357/content.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Steven Fish, Allen Hicken, Matthew Kroenig et al. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: A New Approach”. Perspectives on Politics 9, no. 2 (June 2011): 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1537592711000880.

Dagilytė, Eglė, Aušra Padskočimaitė, and Aušra Vainorienė. “Lithuania’s Response to COVID-19: Quarantine through the Prism of Human Rights and the Rule of Law.” Verfassungsblog, 14 May 2020. https://verfassungsblog.de/lithuanias-response-to-covid-19-quarantine-through-the-prism-of-human-rights-and-the-rule-of-law/.

Diamond, Larry, and Leonardo Morlino. “Introduction.” In Assessing the Quality of Democracy, edited by Larry Diamond and Leonardo Morlino. JHU Press, 2005.

Donnelly, Jack. “Human Rights, Democracy, and Development.” Human Rights Quarterly 21, no. 3 (1999): 608–632. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.1999.0039.

European Parliament. Teleworking, Unpaid Care, and Mental Health during Covid-19’. European Parliament, 3 July 2022. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20220303STO24641/teleworking-unpaid-care-and-mental-health-during-covid-19.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. The Coronavirus Pandemic and Fundamental Rights: A Year in Review, 26 May 2021. https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2021/coronavirus-pandemic-focus.

Government of the Republic of Lithuania. The Decree on the Declaration of State emergency, TAR, No. 4023 (2020). https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/8feb1a7658a111eaac56f6e40072e018.

Gozdecka, Dorota Anna. “Human Rights During the Pandemic: COVID-19 and Securitisation of Health.” Nordic Journal of Human Rights 39, no. 3 (July 3, 2021): 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/18918131.2021.1965367.

Guterres, António. “Remarks at the Virtual Summit of the G-20 on the COVID-19 Pandemic.” United Nations Secretary-General, 26 March 2020. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2020-03-26/remarks-g-20-virtual-summit-covid-19-pandemic.

Hassan, Hamdy A. “What Does Securitization of the ‘Corona Virus’ Mean for African Countries?” Future Center for Advanced Research & Studies, 2020.

Held, David. Models of Democracy. Stanford University Press, 2006.

Jakulevičienė, Lyra, Toma Birmontienė, Regina Valutytė, Dovilė Gailiūtė-Janušonė, Andrejus Novikovas, Dalia Vasarienė, Jolita Miliuvienė, Dangis Gudelis, and Gintarė Giriūnienė. „COVID-19 pandemijos metu priimtų sprendimų vertinimas teisiniu, vadybiniu ir ekonominiu požiūriu.“ Mruni. Mykolo Riomerio universiteas, 2020. https://www.mruni.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/COVID_sprendimu_tyrimo_santrauka.pdf.

Jankevčius, Elvinas. “Set of Transcripts of the Seimas Sittings no. 29 (10 March–21 April 2020; 379–389 Sittings),” 204. https://www.lrs.lt/sip/getFile3?p_fid=44054.

Kumar, Devendra. “Role of Opposition in a Parliamentary Democracy.” The Indian Journal of Political Science 75, no. 1 (2014): 165–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/24701093.

“Law on the Basics of National Security of Lithuania.” Valstybės žinios, no. 55–1520 (1998). Accessed 30 December 2021. https://e-the Seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.120108?jfwid=pd6eq4zc3.

Lebret, Audrey. “COVID-19 Pandemic and Derogation of Human Rights.” Journal of Law and the Biosciences 7, 1 (January 2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/jlb/lsaa015.

Levickytė, Paulina. „I. Šimonytė, A. Armonaitė, V. Čmilytė-Nielsen COVID-19 krizės valdyme atimtų ir vadovavimą iš A. Verygos.“ Lrytas.Lt, 15 October 2020. https://www.lrytas.lt/lietuvosdiena/aktualijos/2020/10/15/news/i-simonyte-a-armonaite-v-cmilyte-nielsen-sutaria-ka-keistu-covid-19-krizes-valdyme-atimtu-ir-vadovavima-is-a-verygos-16710854.

LRSKĮ. “Investigation: Did the Measures taken by the Executive during the Quarantine Period Comply with the Principles of Human Rights and Freedoms?” 17 November 2020. https://www.lrski.lt/en/naujienos/investigation-did-the-measures-taken-by-the-executive-during-the-quarantine-period-comply-with-th.

Lyer, Kirsten Roberts. “Parliaments as Human Rights Actors: The Potential for International Principles on Parliamentary Human Rights Committees.” Nordic Journal of Human Rights 37, no. 3 (July 3, 2019): 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/18918131.2019.1681610.

Lyer, Kristien Roberts, and Philippa Webb. “Effective Parliamentary Oversight of Human Rights.” In The International Human Rights Judiciary and National Parliaments: Europe and Beyond, Matthew Saul, Andreas Follesdal and Geir Ulfstein, 32–58. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Meškaitė, Margarita. „Saugumas užsimojo burti medicinos žvalgus.“ Lsveikat.lt, 30 April 2020. https://lsveikata.lt/aktualijos/saugumas-uzsimojo-burti-medicinos-zvalgus-12159.

Mihr, Anja. “Europe’s Human Rights Regime after 9/11: Human Rights versus Terrorism.” In Human Rights in the 21st Century, edited by Michael Goodhart and Anja Mihr, 131–49. Springer, 2011.

Molnár, Anna, Lili Takács, and Éva Jakusné Harnos. “Securitization of the COVID-19 Pandemic by Metaphoric Discourse during the State of Emergency in Hungary.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 40, no. 9/10 (2020): 1167–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijssp-07-2020-0349.

Ncube, Swikani. “Human Rights Enforcement in Africa: Enhancing the Pan-African Parliament to promote and protect Human Rights.” African Human Rights Law Journal 20, no. 1 (2020). https://doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2020/v20n1a4.

Parry, Geraint. “Opposition Questions.” Government and Opposition 32, no. 4 (October 1997): 457–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.1997.tb00440.x.

Rooduijn, Matthijs, and Teun Pauwels. “Measuring Populism: Comparison of Two Methods of Content Analysis.” West European Politics 34, no. 6 (2011): 1272–1283. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.616665.

Sears, Nathan Alexander. “The Securitization of COVID-19: Three Political Dilemmas.” Global Policy Journal, 25 March 2020. https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/25/03/2020/securitization-COVID-19-three-political-dilemmas.

“Statute of the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania”. Valstybės žinios, no. 15–249 (1994). Accessed 3 March 2022. https://e-the Seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/d9766070c2f511e883c7a8f929bfc500?jfwid=39x432mh7.

Venice Commission. “Opinion on the Protection of Human Rights in Emergencies.” Venice.coe.int/. Council of Europe, 16 March 2006. https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2006)015-e.

Venice Commission.“Interim Report on Measures Taken in EU Member States Due to the COVID-19 Crisis and Their Impact on Democracy, the Rule of Law, and Fundamental Rights.” Venice.coe.int. Council of Europe, 8 October 2020. https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2020)018-e.

VSD and AOTD. “National threat assessment.” Vsd.lt. State Security Department of the Republic of Lithuania and Defense Intelligence and Security Service under the Ministry of National Defence, 2021. https://www.vsd.lt/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2021-EN-el.pdf.

Wæver, Ole. “Securitization and Desecuritization.” In On Security, edited by Ronnie D. Lipschutz, 46–86. Columbia University Press, 1995.

Walton, Douglas Neil. Question-Reply Argumentation. New York and Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1989.

Webber, Grégoire, Paul Yowell, Richard Ekins, Maris Köpcke, Bradley W. Miller, and Francisco J. Urbina. Legislated Rights: Securing Human Rights through Legislation. Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2018.

Wiberg, Matti, and Antti Koura. “The logic of Legislative Questioning.” In Parliamentary Control in the Nordic Countries: Forms of Questioning and Behavioural Trends, edited by Matti Wiberg. Helsinki, Finland: The Finnish Political Science Association, 1994.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72