Respectus Philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2022, no. 41 (46), pp. 67–82 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2022.41.46.109

Modal Verb “Shall” in Contemporary American English: A Corpus-Based Study

Maria Caroline Samodra

Sanata Dharma University

Tromol Pos 29, Mrican, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Email: s.mariacaroline@gmail.com

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9108-8065

Research interests: applied linguistics, language skills, language education

Barli Bram

Sanata Dharma University

Tromol Pos 29, Mrican, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Email: barli@usd.ac.id

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2102-9676

Research interests: linguistics, language education, writing skills

Abstract. This paper explored the modal verb shall in formal and informal writings in academic and fiction registers. It focused on the frequencies of shall across academic and fiction domains in contemporary American English and the differences in the usage of shall between academic and fiction registers of contemporary American English. The researchers used a corpus linguistic method. Data were collected from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) and analysed using Hanks’ (2004) Corpus Pattern Analysis technique. All occurrences of shall in academic and fiction writing styles of COCA were retrieved, and 400 concordance lines consisting of 200 texts from each domain were collected. The texts were analysed and described in accordance with their syntactic, stylistic, and semantic characteristics. Results showed that shall was rare in COCA’s academic and fiction registers as the overall frequencies were 59.77 and 68.34 words per million, respectively. From all the 400 tokens being analysed, the researchers found that shall in the observed data could be classified as rules and regulations, direction, prediction, volition, and etc. The uses of shall in both domains in COCA varied syntactically, semantically, and stylistically.

Keywords: American English; COCA; corpus; modal; register; shall.

Submitted 18 July 2021 / Accepted 31 January 2022

Įteikta 2021 07 18 / Priimta 2022 01 31

Copyright © 2022 Maria Caroline Samodra, Barli Bram. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Modality plays an essential part in communication. It is commonly found in spoken and written language. Portner (2009) defines modality as a linguistic phenomenon that allows speakers to talk about various situations. “Modality, as one of the complex areas of English grammar, reflects the writer’s attitude and is extremely important in academic written discourse” (Yang, 2018, p. 122). Some purposes of modality are to express futurity, necessity, obligation, possibility, and even belief. Those expressions can be uttered in the English language through modal verbs, for example, will, shall, may, can, might, should, or must, with each verb performing different functions.

Presently, shall in American English is declining, and it occurs more frequently in British English because it is regarded as formal and old-fashioned (Darragh, 2000; Leech, 2004; Williams, 2009). According to Schluter (2009), American English has more colloquialisation than British English. This suggests that American English tends to use more informal patterns. Linguistically, shall is an English modal verb that has existed for centuries (Larreya, 2009, p. 23). In the past, its usage was mainly to deliver futurity and command, especially in legal or biblical texts. “In formal discourse, shall is used to emphasize the legal effect, indicates command and promise, and is used in second and third-person statements” (Chen, Jiang, Song, and Wang, 2020, p. 91). Umeh and Anyanwu (2020, p. 7) conclude that “shall invariably expresses intention, willingness, and insistence.” Over time, the use of shall is declining. Biber, Conrad, and Leech (2002), for instance, claim that shall in American and British English is the least frequent modal verb among will, may, can, might, should, and must. The most used modal verb nowadays is will. Meanwhile, shall and will are synonymous in expressing futurity (Darragh, 2000). To illustrate, “I shall arrive at 7 o’clock” is interchangeable with “I will arrive at 7 o’clock.”

Generally speaking, shall is regarded as formal and old-fashioned (Biber et al., 2002; Williams, 2009), and thus it is unlikely to be used in daily life. Portner (2009, p. 2) underlines that a modal verb can perform different functions in certain situations. Accordingly, the modal verb shall, in specific ways, can promote meanings that cannot be delivered through other modal verbs, making it still exist in current English. Some studies on several aspects of the modal verb shall have been conducted by several researchers, such as Biber et al. (2002), Darragh (2000), Gotti (2003), and Williams (2009). Gotti (2003), for example, investigates how the modal verb shall is used in Middle English and Early Modern English; the findings show that shall appears in diverse texts of Middle English and Early Modern English.

On the other hand, Williams (2009) examines the modal verb shall specifically in legalistic texts. It is revealed that although shall causes multi-interpretation of the texts, it has not been abolished altogether. Interestingly, Krapivkina (2017, p. 312) concludes that “the verb shall is semantically diverse, performing some functions in legal discourse.”

Although shall has been investigated previously, it still raises some issues. One cause is the inadequacy of data for the research. Gotti (2003), for instance, used the Helsinki corpus, while Williams (2009) mainly relied on the “world data” corpus (140,000 words) and the “shall-free” corpus (160,000 words). Those corpora, unfortunately, contain a relatively small number of words, which is considered weak in representing the language being used (Meyer, 2004, pp. 41–42). In contrast, Biber et al. (2002) have utilised a relatively large corpus, namely the Longman Spoken and Written English Corpus (LSWE), which consists of 40 million words. Nevertheless, their investigation has not clarified the use of shall exhaustively because the analysis only covers a few general points of how this auxiliary is used.

Therefore, the researchers investigate the use of shall in contemporary American English using a corpus. American English is chosen as the focus of the study since, nowadays, it is one of the most common English varieties used by native speakers, and it is studied by most foreign learners (Algeo, 2006, p. 1). It is also a standard variety of English (Rohdenburg, Schluter, 2009, p. 2) to which English teachers and students frequently refer.

Specifically, the researchers focus on the use of shall in formal and less formal written contexts represented by academic and fiction registers in COCA, respectively. A register or domain is language variety related to specific situations of use and certain communicative purposes (Biber, 1996). The study of shall in formal and informal written contexts of American English means to provide enrichment for English language teachers and learners on how shall is used, especially in writing academic and non-academic works.

Based on the background, the formulated questions are as follows. First, what are the frequencies of the modal verb shall across academic and fiction registers in contemporary American English? Second, how does the modal verb usage differ between academic and fiction registers of contemporary American English?

Method

This study employed a corpus linguistic method, relying on quantitative and qualitative techniques (Biber, Conrad, Reppen, 1998). It is quantitative because it involves calculating the occurrences of a particular linguistic item. Besides, it interprets the patterns found in the quantitative data functionally or qualitatively (Biber et al., 1998). Using a corpus-based approach means that corpus linguistics is the research method (Baker, 2010; Kennedy, 1998; McEnery, Hardie, 2012; Meyer, 2004).

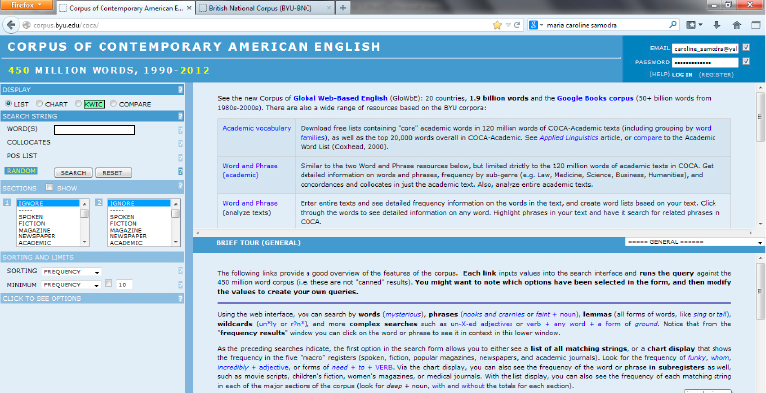

The research data source was the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), a corpus of American English created by Mark Davies (2008). There are 450 million words in this corpus. It presents raw data from spoken contexts, fiction, magazines, newspapers, and academic journals (Figure 1).

Using a purposeful sampling method, one can comprehensively select and study information-rich cases (Patton, 1990). In this study, purposeful sampling was used to select instances of shall in academic and fiction registers of COCA. Purposeful random sampling increases the credibility so that the texts have the same probability of being included in the sample (Patton, 1990).

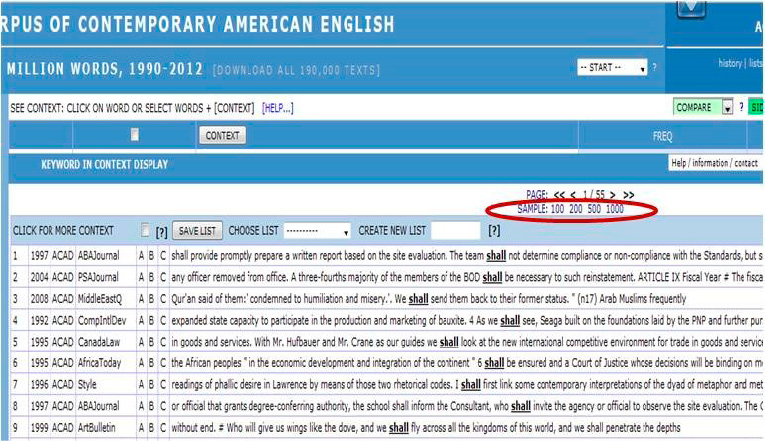

To collect the data, the researchers used COCA by typing the modal verb shall in the search string of COCA. To examine the patterns of usage of shall, the researchers took 400 samples containing the modal verb shall from the corpus. The researchers adapted the Corpus Pattern Analysis (CPA) technique proposed by Hanks (2004) to analyse the qualitative data. The data were obtained in two steps. Firstly, 200 random concordance lines from the academic register were taken. Next, the other 200 concordance lines were retrieved from the fiction register of COCA. The researchers selected the option sample in COCA to take a random sample, which automatically randomized the data (Figure 2).

Figure 1. COCA interface

Figure 2. Data randomisation in COCA

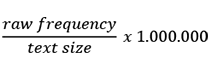

Quantitative and qualitative analysis techniques were employed to answer the research questions. After obtaining the raw data from COCA, the researchers examined the frequency counts of the modal verb shall in each register to answer the first research question. To compare academic and fiction registers, the normalised frequencies of the modal verb shall be used instead of the raw frequencies.

Hanks’ (2004) Corpus Pattern Analysis (CPA) was employed to answer the second research question. First, CPA was used to extract a concordance list of the target word from the corpus and examine the “general overview of the word’s behaviour” (Hanks, 2004, p. 91). Second, the analysis was done by selecting the sample consisting of 200 to 1000 concordance lines. After that, each concordance line was classified with those having the same meaning and similar syntactic structure.

To categorise the uses of shall from both registers, the researchers referred to the checklist adapted from Leech’s (2004) classification of modal verb shall and Palmer’s (2001) typology of modality.

Findings and discussion

A. Frequency of modal verb shall across registers in COCA

This section discusses the occurrences of modal verb shall in academic and fiction registers of COCA. It provides the frequency of modal verb shall across academic and fiction registers in numerical data. After that, an explanation of the frequency of modal verb shall is given to describe the numbers. Therefore, to obtain valid results, the frequency is normalised. Based on Biber et al. (1998, p. 263), the researchers concluded that the formula for frequency normalisation per million words is:

Fortunately, COCA has provided the normalised frequency per million words for each domain. The results show that shall is slightly less dominant in the academic domain with the value range of 59.77 and 68.34 for academic and fiction registers. With those numbers, it is expected that there exist approximately 60 occurrences of shall in one million words of academic register and approximately 68 occurrences of shall in one million words of fiction register.

Table 1. Results for shall overall frequencies across written registers in COCA

|

No. |

Register |

Raw frequency |

f per million |

|

1 |

Academic |

5443 |

59.77 |

|

2 |

Fiction |

6180 |

68.34 |

The possible cause for slightly higher overall frequency in the fiction register is that the writers of fiction genres have more freedom to use diverse language elements as they are not required to comply with grammatical or semantical rules (Sanger, 2003). Thus, it allows various usages of the modal verb shall in a large number of fictional discourses. Meanwhile, there are rules in writing the journals in the academic domain, limiting certain functions of modal verb shall. Nevertheless, the minor difference in the overall frequency still signifies that shall is rare in the academic and fiction registers of contemporary American English. This, therefore, supports the idea that shall is rare (Biber et al., 2002; Sujatna, Sujatna and Pamungkas, 2019).

However, when the sub-registers of the academic and fiction domains are observed individually, results show that shall is used dominantly in COCA’s law/political science domain with the frequency rate of 158.95 words per million. The second highest frequency is in the field of philosophy/religion, with 124.48 words per million. The numbers mean that, among the examined sub-registers, shall is highly used in legal and religious texts. The high frequency is likely to be caused by the retention of the modal verb shall in the Present-Day contexts. In Old English, back to the history shall was used to express command or obligation (Fowler, Fowler, 1931). Command or obligation is associated with legal texts and religious treatises. Additionally, Americans have been using shall in writing legal texts since 600 years ago (Williams, 2009, p. 199). The examples of how shall are used in COCA’s law/political and philosophy/religion sub-registers are presented in (1) and (2).

(1) […] the circumstances constituting fraud or mistake shall be stated with particularity. (COCA:LawPublicPol)

(2) […] therefore, suspended until he shall manifest Such Repentance as Shall be Satisfactory to the Church. (COCA:ChurchHistory)

Example (1) reflects law enforcement using shall and (2) is related to church rules in old times. The high frequencies of shall in those two sub-registers are consistent with the earlier research conducted by Gotti (2003), who reveals that the frequent appearance of shall is located in legal texts, religious treaties, and the Bible in Middle English and Early Modern English.

On the contrary, the lowest frequencies are in the field of education and medicine. The normalised frequencies are subsequently 20.86 and 9.25. It implies that the use of shall in education and medicine fields is not significant compared to other sub-registers.

Table 2. Frequencies across written sub-registers of shall in COCA (sorted based on f per mil)

|

No. |

Sub-registers |

Raw frequency |

f per million |

|

1. |

Academic-Law/PolSci |

1367 |

158.95 |

|

2. |

Academic-Philosophy/Religion |

839 |

124.48 |

|

3. |

Fic-Juvenile |

348 |

110.18 |

|

4. |

Fic-SciFi/Fantasy |

1748 |

87.59 |

|

5. |

Academic-History |

1038 |

84.77 |

|

6. |

Fic-Journal |

2072 |

64.6 |

|

7. |

Academic-Humanities |

768 |

64.39 |

|

8. |

Fiction (Book) |

1497 |

61.14 |

|

9. |

Fic-Movies |

503 |

56.25 |

|

10. |

Academic-Geography/Social Science |

449 |

27.75 |

|

11. |

Academic-Science/Technology |

329 |

23.37 |

|

12. |

Academic-Education |

197 |

20.86 |

|

13. |

Academic-Medicine |

62 |

9.25 |

Table 2 shows that shall is used in various domains. Although considered rare in American English, it is predicted that this modal verb has some usages in academic and fiction registers, as seen in the different frequencies of each sub-register. Therefore, in the next section, shall across academic and fiction registers is examined comprehensively.

B. The usage of modal verb shall across registers in COCA

From a total of 400 random tokens, it is discovered that there are differences in the usage of shall across both domains. With the designed category scheme adapted from Leech (2004) and Palmer (2001), the researchers can classify uses of shall into rules and regulations, direction, permission, prediction, volition, and others. Table 3 presents the frequencies of the modal verb shall based on its usage.

Table 3. 400 random tokens of shall from academic and fiction registers of COCA

|

No. |

Registers Usages |

Academic |

Fiction |

|

1 |

Rules and Regulations |

65 |

0 |

|

2 |

Direction |

28 |

23 |

|

3 |

Permission |

10 |

11 |

|

4 |

Prediction |

32 |

46 |

|

5 |

Volition |

58 |

100 |

|

6 |

Others |

7 |

20 |

|

Total |

200 |

200 |

|

1. Rules and regulations

Based on Palmer’s (2001) types of modality, shall as rules and regulations is classified as deontic modality because an obligation applies to the addressee of the statement.

a. Prescriptive shall in the academic register

The modal shall as rules or regulations still primarily occur in the COCA academic register data sample. There are 65 occurrences of shall functioning as rules or regulations. According to Garner (2004, p. 4288), in legal texts, shall with the sense has a duty to is the only acceptable meaning. Therefore, in this case, shall is supposed to be used only to express a strong sense of obligation. Shall with prescriptive meaning has various preceding subjects, depending on who is given the obligation. All statements from the sample occur with third-person subjects. Examples are in (3), (4), and (5).

(3) The Judges, […] shall hold their respective offices … (COCA:LawPublicPol)

(4) The chairperson […] shall present the Committee findings, conclusions ... (COCA:ABAJournal)

(5) each Party shall ensure that persons with a legally recognized […] its law ... (COCA:CanadaLaw)

In those cases, the Judges, Chairperson, and Party are the subjects being ordered to do something. The verbs following shall explain the deeds which the subjects are required to do. However, shall does not necessarily mean obligation in legalistic contexts. The first condition is when shall conveys negative senses as seen below:

(6a) a lawyer shall not reveal information relating to the representation of a client ... (COCA:ABAJournal)

(7a) No Federal court shall have jurisdiction under Federal ... (COCA:EnvirAffairs)

In examples (6a) and (7a), it would be irrelevant to categorise the meaning of shall as having a duty. If interpreted with that meaning, it would negate the duty. For instance, in (6a), the meaning would become “A lawyer does not have the duty to reveal information relating to the representation of a client.”

That interpretation does not convey the intended meaning since the expressions deliver prohibition. As Garner (2004, p. 4288) proposes, when shall is combined with negative words such as no or not, the meaning of shall changes into may. Because the example statements (6a) and (7a) are negated, the permission conveyed by may is invalidated. Therefore, if interpreted based on Black’s Law Dictionary, the meanings become:

(6b) a lawyer may not reveal information …

(7b) No Federal court may have jurisdiction …

The researchers also discovered that although passive forms are undesired in American legal texts (Williams, 2009, p. 200), sentences with passive shall still occur. Passive verbs from the sample follow 14 expressions with shall. Examples are in (8) and (9).

(8) and the provisions […] as outlined above shall be largely externally determined. (COCA:ArabStudies)

(9) On all matters and questions […] , a majority of votes cast shall be required to carry any action. ... (COCA:PSAJournal)

In (8) and (9), the actors are unclear. The actions to determine and to require are apparent.

b. Prescriptive shall in fiction register

While the use of prescriptive shall is dominant in the academic contexts, the fiction register contains no shall functioning as rules or regulations. This means that the use of prescriptive shall in informal writing is rare or even absent in COCA because academic and fiction registers are two different genres with different content.

2. Direction

The directive shall is also classified as deontic modality, of which the type is an obligation (Palmer, 2001). Since it involves giving orders to the addressee, the preceding subjects are other than first-person pronouns (I and we). As an order or instruction, shall is used with second-person you or third-person personal pronouns.

a. Directive shall in the academic register

In the sample from the academic register, there are 28 concordance lines with shall classified as direction. The patterns are similar to shall occurring in rules or regulations because the modal verb functions to express the obligation that the addressees must fulfil. The difference is that they do not occur in legal contexts, thus making them less incumbent. Based on Leech’s (2004) usage classification of shall, the use of shall instead of will makes the situation formal. The patterns of use are represented in (10) and (11).

(10) Instructor shall use Instructor’s best efforts to cause all guest lecturers taking part in UNEX Classes ... (COCA:October)

(11) And if that question shall be decided in the affirmative by two-thirds of the Senators … (COCA:LawPublicPol)

Example (10) shows that shall is used to ask someone to do something. Meanwhile, example (11) implies that directive shall can be expressed through if-conditional sentences. If that particular event does not happen, the other action will not occur, either.

Among all the 28 concordance lines with shall, 10 are passives. Comparable to rules and regulations, passive shall causes the subjects or agents to be unclear. In examples (12) and (13), the agents are not apparent, making the addressee of the direction or to whom the necessity is given vague.

(12) Baudrillard-style market-driven popularity shall henceforth be called (COCA:AnthropolQ)

(13) […] the President of the United States, and that the laws […] shall be continued in force (COCA:AmerIndianQ)

b. Directive shall in the fiction register

In the fiction domain, there are 23 excerpts classified as directive shall. The subjects are also mostly second-person and third-person. The second-person subject you appears to be slightly more frequent than in the academic register with five occurrences. Regarding the frequency, shall as a direction in this field has no significant difference from an academic domain.

Nevertheless, although shall is typically used in formal situations (Darragh, 2000; Leech, 2004; Williams, 2009), it is reflected from this register that the use of directive shall in COCA is not limited to formal contexts as there are minor non-standard expressions found in the data. The language used to express a directive shall contains more colloquial vocabulary items. It is, in fact, closer to the language in everyday life.

(14) La-la-la-la-la-la-la, # … La-la-la-la, … # For the Russians shall not have ConstantinOPLE! (COCA:USCatholic)

(15) […] the dismal bells of harsh music: shall not, shall not, shall not. You shall not learn; you shall not earn (COCA:CriticalMatrix)

(16) […] And Ru-rulii, bow-bow: you shall act our will in this matter. I lower my nose … (COCA:Analog)

Examples (14), (15), and (16) show that directive shall is applied in various unconventional styles. In (14), the non-standard parts are located in the absence of the subject and the chanting. (14) is not a complete sentence because it starts with for without any main clause. Besides, the chanting of the lalala sound and the capitalisation of OPLE in “Constantinople” make the situation informal. In (15), the repetition of shall not makes the utterance unusual. Meanwhile, in (16), the informality lies in the speaker’s saying, “Ru-rulii, bow-bow,” which is considered colloquial style.

3. Permission

The researchers identified a new usage category of shall in academic and fiction registers in the data analysis, which differs from Leech’s (2004) classification of shall usage. Limited to rules and regulations or directions, shall with second-person and third-person subjects be used to express permission. When one encounters shall with second-person or third-person pronouns, it might be misinterpreted as rules, regulations, or other mandative meanings because of the similar characteristics. However, if being observed comprehensively, it can be shown that shall as permission involves giving someone the right to do something.

a. Permissive shall in the academic register

In the academic register, permissive shall is not dominant compared to other usages of shall in this domain as there are only ten texts classified from all 200 excerpts. In addition, permissive shall in the academic register with second-person subjects are not found in the sample. There are only occurrences with third-person subjects. The use of shall to express permission in the academic register is given in example (17).

(17) The last words shall be his: # Genuine politics, politics ... (COCA:PerspPolSci)

b. Permissive shall in the fiction register

There are 11 occurrences of permissive shall. The use of shall in this domain is similar to that in the academic domain related to its syntactic structure. Nevertheless, there are both second-person and third-person subjects in this register, and it is used to express the act of granting something to someone.

(18) […] clean stroke himself. […] Frike, you have done very well. You shall enter my employ at once ... (COCA:BkSF:BringMeHead)

Example (18) represents permissive shall with the second-person subject you. It occurs five times, and the situations are all conversational. The second-person you and its absence in the academic register imply that, in fiction writing, you is a common pronoun because the conversation is one feature of fiction writing (Sanger, 2003). Similar to the patterns in other usages of shall in fiction register, utterances with permissive shall have minor unusual characteristics, as seen in (19).

(19) Ophelia is even now our captive. Should you exact thy vengeance, the maiden shall unto you be delivered … (COCA:Mov:BourneSupremacy)

Example (19) contains an archaic second-person pronoun thy and the adverbial phrase unto you is put before the verb be. Example (19) reflects the characteristics of the common sentence patterns in Early Modern English, allowing diverse subject, auxiliary, or verb inversion (Singh, 2005).

4. Prediction

Predictive shall is categorised when the expressions involve the knowledge of the speaker. In other words, it belongs to the epistemic modality (Palmer, 2001). Predictive shall focuses on the events that are predicted to happen in the future using speculative or assumptive judgements.

a. Predictive shall in the academic register

Based on the investigation of the tokens in COCA, it is revealed that there are 32 occurrences of shall in academic discourse that are used to express futurity. Shall as prediction is primarily used with first-person personal pronouns I and we, as seen in (20).

(20) And let us not be weary […], we shall reap if we faint not. (COCA:Church&State)

Example (20) shows that the uttered facts deliver either assumptive judgements. Unlike the usage of predictive shall suggested by Leech (2004), shall as prediction does not always start with first-person subjects.

(21) Look to Africa for the crowning of a black king; he shall be the redeemer […] (COCA:NaturalHist)

(22) The righteous shall flourish like the palm tree […] the workers of iniquity shall be destroyed ... (COCA:AmerScholar)

In (21), the agent predicts that there will be a redeemer, and in (22), the speaker predicts that there will be more righteous people in the future, “flourish like a palm tree” Predictive shall is chosen in the academic contexts because it is considered more formal than will and may.

b. Predictive shall in the fiction register

The fiction register uses richer sentence patterns with shall, conveying predictive meanings. Similar to that of the academic register, the use of predictive shall in this register is not limited to first-person personal pronouns as there are occurrences of shall with pronouns other than I and we.

The researchers find that variant forms are used with predictive shall in fiction. The results are that archaic words or inverted sentence patterns used with predictive shall be represented in examples (23–24).

(23) […] White is White and never the twain shall meet. (COCA:FantasySciFi)

(24) […] the grasses of the Valley of Elah, then shall my brother’s seed flow out from him. (COCA:SouthernRev)

Predictive-shall expressions show patterns in which adverbials are placed in inverted manners. For example, in (23), the adverb never is located before the subject the twain. Additionally, example (24) represents auxiliary inversion, in which shall is placed before the subject although it is not an interrogative form.

5. Volition

The most complex patterns of usage of modal verb shall are in the volitive shall. Based on Palmer’s (2001) modal typology, volitive shall can be categorised as either deontic or dynamic modality. Shall is classified as deontic when it expresses the speaker’s commission to do something. It is said to be dynamic, or specifically volition, because it is unrelated to the speakers’ knowledge and expresses willingness. The preceding subjects of volitive shall are first-person pronouns.

a. Volitive shall in the academic register

From the 200 random tokens of the COCA academic register, the use of shall as volition occurs 58 times. The sentence patterns are in the form of statements and interrogatives. When the subject of the statement with shall is the first person I, the speakers are identified as expressing their willingness to do specific actions. Examples are (25) and (26).

(25) I shall discuss the relation between the verbal ... (COCA:Symposium)

(26) I shall refer indifferently to the EC or the EU. ... (COCA:AcademicQs)

When the subjects are the first person we, the meaning of shall slightly changes. In this case, the speaker initiates suggestions or offers to others.

(27) These same visitors may also ask what we shall find to be a closely related question: ... (COCA:AnthropolQ)

(28) We shall see that at least one text is difficult ... (COCA:Monist)

In (27) and (28), the subjects, we, suggest that other people do something with them together.

The use of interrogatives with shall in the samples of academic domain, however, is rare. In the academic register, volitive questions using shall only occur five times. All of them appear in conversational situations, as shown in (29), (30), and (31).

(29) Or shall I set in motion that works which I can carry out ... (COCA:CrossCurrents)

(30) Shall we alternately witness a broad shift towards radicalism [...] Muslim moderates? (COCA:MiddleEastQ)

(31) Shall we put that down, sir? (COCA:ContempFic)

Examples (29–31) have the same meaning as statements using volitive shall with first-person subjects I and we, respectively. Example (29) shows that the speaker offers to do something. In examples (29–31), the speakers ask the addressees to do something with them.

b. Volitive shall in the fiction register

In the fiction domain, shall as volition is significantly more frequent than that of academic register. There are a total of 100 occurrences with volitive shall. The characteristics of shall usage in this domain are similar to that in the academic domain. First, the sentence patterns are in the form of statements or questions. Secondly, the researchers found that shall is used to express personal intentions when it is preceded by the first-person subject I and suggestions when it starts with the first-person subject we. Excerpt (32), for example, uses we to deliver suggestions to the addressee, Mister Souter.

(32) We shall speak later, Mister Souter. I believe I have a few obligations ... (COCA:Bk:EnglishHorses)

Thirty-six of the tokens are interrogatives expressing volition or willingness. Apparently, the interrogative forms appearing in the data are more variable. Besides questions that start with shall we, which conveys suggestions, some questions start with shall I functioning to express one’s intention to do something. Example (33) shows that I intends to get everything prepared at seven.

(33) That would be very nice. Shall I be ready then at seven? […] Yes, I should be finished ... (COCA:Bk:InterviewVampire)

Apart from the fundamental question pattern (33), four of the utterances are question tags as represented in (34). All the examples of shall with question tag use we, and the expressions are always preceded with let’s. In this case, it delivers the meaning that question tags with shall, in this case, are used to provide a suggestion.

(34) Let’s abandon the pretense that you know nothing, shall we? You don’t care … (COCA:BkSF:SlowWaltz)

From the data, it is also identified that there are expressions with two modal verbs, shall and have to, at the same time. Six concordance lines from the sample are identified using this form. Meanwhile, have to is a modal verb used to express obligation. This reflects the speakers’ volition, which is based on their obligation. Examples (35) and (36) show that the speakers or subjects have the intention to do certain deeds; however, the addition of have to makes the willingness driven by a particular force, either inside or outside the speakers.

(35) I shall have to confess this […] , she thought, for... (COCA:Bk:DaughterYork)

(36) […] be forced to pay the killer’s brutal toll because of this decision? We shall have to wait and see ... (COCA:Bk:NightPrey)

The more novel forms of volitive shall in the fiction domain are reasonable because fiction allows writers to use various language elements (Sanger, 2003). Therefore, it makes sense that volitive shall in the data of COCA fiction register mostly occurs in conversational contexts.

Conclusion

The researchers conclude that shall occur more frequently in the fiction register than that in the academic register with the overall frequencies of 68.34 and 59.77 words per million, respectively. Results revealed that the highest frequencies of shall were in law and religion/philosophy sub-registers. These frequencies implied that shall was significantly used in legal and religious contexts. On the contrary, the least occurrence of shall was located in the education and medicine sub-registers, which suggested that shall was not remarkable in those fields.

Usages of shall in academic and fiction registers varied syntactically, semantically, or stylistically. The researchers found out that the usage of shall could be classified as rules and regulations, direction, permission, prediction, and volition. The most significant difference of shall in academic and fiction registers was in rules and regulations. In the academic domain, shall occurred 65 times, but there was no occurrence of shall in the fiction domain. This could be true because both registers were domains with different content.

Shall was categorised as direction when it used second-person or third-person subjects, and it was used to express order or obligation. The distinction from that of rules and regulations was that directive shall was not written in legal contexts, thus making it less binding. In terms of frequency, there was no meaningful difference between academic and fiction registers in using directive shall. In the fiction domain, the difference was that there were patterns in which shall was used with inverted sentences or archaic language features.

The most variable patterns of usage of the modal verb shall were found in the concordance lines with volitive shall. The preceding subjects of volitive shall were first-person personal pronouns I and we. From the usage patterns being examined, it could be seen that when the subject was the first person I, shall was used to express one’s intention. However, when the subject was the first person we, shall delivered suggestions to the addressee. In the academic field, volitive shall occurred 58 times. The fiction registers had more frequent volitive shall as there were 100 occurrences.

The limitation of this research lies in the number of data collected based on purposeful random sampling. Thus, it is possible that some minor patterns of shall usage have been excluded because they were not drawn as the sample. For further research, various aspects of shall can be explored. Future researchers are encouraged to investigate shall in spoken registers and other English varieties, such as British English and Australian English.

Sources

Davies, M., 2008. The corpus of contemporary American English: 450 million words, 1990-present. Available at: <http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/>.

Garner, B. A., ed., 2004. Black’s law dictionary. 8th ed. New York: Thomson West.

References

Algeo, J., 2006. British or American English? A handbook of word and grammar patterns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, P., 2010. Corpus methods in linguistics. In: Litosseliti, L., ed. Research methods in linguistics. London: Continuum, pp. 93–113.

Biber, D., 1996. University language: A corpus-based study of spoken and written registers. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., Leech, G., 2002. Longman student grammar of spoken and written English. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., Reppen, R. 1998. Corpus linguistics: Investigating language structure and use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, H., Jiang, R., Song, Y., Wang, J. H., 2020. A corpus-based study of the central modal verbs in legal English. Frontiers in Educational Research, 3 (11), pp. 88–92. https://doi.org/10.25236/FER.2020.031115.

Darragh, G., 2000. A to zed, a to zee: A guide to the differences between British and American English. Irun: Editorial Stanley.

Fowler, H. W., Fowler, F. G., 1931. The King’s English. 3rd ed. London: Clarendon Press.

Gotti, M., 2003. Shall and will in contemporary English: A comparison with past uses. In: Facchinetti, R., Krug, M. G., & Palmer, F.F.R., eds. Modality in contemporary English, 44. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 267–300.

Hanks, P., 2004. Corpus pattern analysis. Computational Lexicography and Lexicology, pp. 87–97. Available at: <http://www.euralex.org/elx_proceedings/Euralex2004/009_2004_V1_Patrick%20HANKS_Corpus%20pattern%20analysis.pdf> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

Kennedy, G. D., 1998. An introduction to corpus linguistics. London: Longman.

Krapivkina, O. A., 2017. Semantics of the verb shall in legal discourse. Jezikoslovlje, 18 (2), pp. 305–317. Available at: <https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=583956> [Accessed 20 June 2020].

Larreya, P., 2009. Towards a typology of modality in language. In: Salkie, R., Busuttil, P., & van der Auwera, J., eds. Modality in English: Theory and description, 58. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 9–30.

Leech, G., 2004. Meaning and the English verb. Harlow: Pearson Longman.

McEnery, T., Hardie, A., 2012. Corpus linguistics: Method, theory, and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, C. F., 2004. English corpus linguistics: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Palmer, F. R., 2001. Mood and modality. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Patton, M., 1990. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Portner, P., 2009. Modality: Oxford surveys in semantics and pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rohdenburg, G., Schluter, J., eds., 2009. One language, two grammars? Differences between British and American English, 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–12.

Sanger, K., 2003. The language of fiction. London: Routledge.

Schluter, J., 2009. Phonology and grammar. In: Rohdenburg, G. & Schluter, J., eds. One language, two grammars? Differences between British and American English, 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 13–37.

Singh, I., 2005. The history of English: A student’s guide. London: Hodder Education.

Sujatna, M. L., Sujatna, E. T. S., Pamungkas, K., 2019. Exploring the use of modal auxiliary verbs in Corpus of Contemporary of American English (COCA). Sosiohumaniora, 21 (2), pp. 166–172. https://doi.org/10.24198/sosiohumaniora.v21i2.19970.

Umeh, I., Anyanwu, E., 2020. The semantics of modal auxiliary verbs in the 2018 second term inaugural speech of governor Willie Obiano In Anambra state. Interdisciplinary Journal of African & Asian Studies (IJAAS), 6 (1), pp. 1–9. Available at: <https://nigerianjournalsonline.com/index.php/ijaas/article/viewFile/835/820> [Accessed 2 July 2021].

Williams, C., 2009. Legal English and the ‘modal revolution’. In: Salkie, R., Busuttil, P. & van der Auwera, eds. Modality in English: Theory and description, 58. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 199–210.

Yang, X., 2018. A corpus-based study of modal verbs in Chinese learners’ academic writing. English Language Teaching, 11 (2), pp. 122–130. http://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v11n2p122.