Respectus Philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2023, no. 43 (48), pp. 110–124 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2023.43.48.113

Creation and Analysis of Corpus of Short Prose by Latvian Women Writers

Zita Kārkla

University of Latvia, Institute of Literature, Folklore and Art

Mukusalas 3, Riga, LV-1423, Latvia

Email: zita.karkla@lulfmi.lv

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6805-2996

Research interests: women’s writing, feminism, history of literature

Haralds Matulis

University of Latvia, Institute of Literature, Folklore and Art

Mukusalas 3, Riga, LV-1423, Latvia

Email: haralds.matulis@gmail.com

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0142-7677

Research interests: digital humanities methods, computational methods

Abstract. The article aims to present the creation of the text corpus of short prose by Latvian women writers and a pilot study on the distribution of body words in the corpus. The corpus development is a part of the research process, which aligns with the goals and perspectives of feminist literary history. First, the paper introduces the design of the corpus. Consisting of 259 texts, published between 1893 and 2002, it is the first literary corpus focusing on Latvian women writers and on short prose. Given that short forms have long dominated women’s prose, this focus was a conscious decision to highlight women’s contribution to writing. Further, the article presents the methods of distant reading that were applied to identify the distribution of body words in the texts. The desire to reintroduce women into the history of literature has also led to a focus on the body. While writing is mediated through the body, it is also a space to explore and take possession of the body. Finally, by combining the results of distant reading with examples of close reading, the distribution of body words in different periods is compared.

Keywords: history of women’s writing; corpus development; body; distant reading; close reading.

Submitted 31 December 2022 / Accepted 5 March 2023

Įteikta 2022 12 31 / Priimta 2023 03 05

Copyright © 2023 Zita Kārkla, Haralds Matulis. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The history of women’s writing is a fascinating subject, and it is a vast, still under-explored field of study in the history of Latvian literature. Research on women writers started in the 1930s (Brante, 1931; Ķelpe, 1936) but was interrupted by historical and political circumstances1 and resumed only in the 1990s both in exile and Latvia (Cimdiņa, 1997; Ezergaile, 1998). It took almost two decades until more contemporary approaches were applied to the study of women’s writing (Meškova, 2009; Semjonova, 2017; Kārkla, 2022). Furthermore, whereas progress has been made in the conscious revision of literary canon by recovering women writers and making available their texts that have disappeared in literary history, it is still an ongoing work.

With the development of digital literary scholarship, feminist researchers face new challenges reopening questions that have been relevant since the 1970s, when efforts led to an increase in the number of printed collections and anthologies devoted to the work of women authors. In the process of digitizing literary works and building text corpora, women’s writing often tends to get “lost” again. Given that women authors are not as well represented as men in academic libraries and other digitized collections, the digital literary canon replicates the canonization that existed in print so that the marginalization of women inherent in archives, in general, is reinforced rather than compensated for by the amount of data. According to L. Mandell, in today’s digital environment, the call of feminist criticism to recover and preserve the works of women writers, to increase their presence and importance in the canon, and to examine the literary history and critical paradigms is again particularly relevant (Mandell, 2016, p. 521).

The growing interest in digital humanities within Latvian academia has prompted the creation of a more significant number of different text and speech corpora and has brought the issue of women’s representation in Latvian digital literary studies to the forefront. There is a limited number of specialized corpora of literary texts in Latvian, and, so far, digitization efforts of literary texts have been primarily focused on novels.2 The Corpus of Latvian Early Novels (LatSenRom3) is a text corpus of digitized Latvian novels first published before 1940. This corpus is dominated by male authors; for example, out of forty-six Latvian novels published between 1900 and 1914, only two were written by women (Daija, Kalnačs, 2019), prompting the question of why there is such a significant lack of representation of women authors. In 1912, prominent literary critic A. Birkerts (1912, p. 9) wrote:

It is also a strange phenomenon among our women that in the field of fiction they do not turn to the novel, which is so popular among foreign women writers... So the novel is still waiting for the Latvian woman.

It is important to note that while Latvian women began writing novels much later than men, women were prolific writers of short prose. Thus, a deliberate focus on creating a corpus of women’s short prose for digital research was primarily motivated by the fact that in the early period of Latvian literature, women tended to write predominantly in this form. Eventually, the creation of the corpus becomes part of the research and “recovery” process aimed toward gender inclusion in literary studies.

As several feminist scholars have pointed out, F. Moretti’s (2000) critique of the literary canon, seeking to de-centre the canon and revise what we read and study by the methods of distant reading, corresponds with the efforts of feminist researchers to expand the literary canon in order to include forgotten women writers and their texts (Houston, 2019; Koser, 2020). Distant reading, a method of analysis based on objective data from many texts, enables the detection of patterns and examination of broader cultural and historical changes that might be reflected in literature. According to T. Underwood (2017), the central practice that distinguishes distant reading from other forms of literary criticism is “the practice of framing historical inquiry as an experiment, using hypotheses and samples (of texts or other social evidence) that are defined before the writer settles on a conclusion.” With this in mind, the paper aims to present the development and basic design of the corpus of Latvian women writers’ short fiction, produced between 1893 to 2002, and report on a pilot study of the application of both distant and close reading methods to the corpus. After a review of the corpus design, the methodology employed and the results obtained, the paper focuses on the distribution of body words in different time periods. Combining distant and close reading methods, the paper aims to determine whether it is possible to identify any historical patterns in the use of body words in literary texts written by women.

Pilot corpus of women writers’ short fiction

The pilot corpus of short fiction by Latvian women writers in its current version consists of 259 texts by 93 authors, amounting to 925 000 words. The oldest included text is the first known Latvian women writer Marija Medinska–Valdemāre’s unfinished story Sērdienīte (The Orphan Girl, 1893). The latest text in the corpus, marking the turn of the century and the entrance of a new generation of women writers, is Inga Ābele’s story Mīlestības gadi (Years of Love, 2002). Feminist scholars J. Bergenmar and K. Leppänen (2017, p. 232)., working on the literary histories of minor languages, have brought forward the idea that digitization of a corpus of texts “may be thought of as part of the research process in projects oriented towards gender and cultural exchange”. We fully embrace this perspective and see the creation of a corpus of short prose by Latvian women writers as an essential component of our research.

For the purpose of this study, the corpus is divided into four sub-periods. Referring to the latest version of the history of Latvian literature (LLV, 1999–2003), the division is based on historical and political events that influenced and changed the literary situation, such as pre-independent Latvia, independent Latvia in the interwar period, the Soviet occupation, and the post-Soviet period. The four sub-periods in the corpus also reflect the historical development of the publication of prose texts by women authors. The first sub-period (1893–1917) represents the beginning of Latvian women’s writing, dominated by short forms. During this sub-period, only two novels written by women were published (Briedis, Rožkalne, 2014, pp. 121–122). The sub-period is also characterized by the fact that a large part of the texts have never been published in books and can be found only in periodicals. Digitizing these texts, published initially in old print, required a significant investment of time and careful manual editing.

The second sub-period (1918–1939) covers the flourishing of women’s writing in the inter-war period. Due to the changes in the role of women in society, greater educational opportunities, the economic prosperity that allowed women to pursue the arts, and, not least, the rise of newspaper and magazine publishing and the booming of women’s magazines opened up new opportunities for publication. However, many women’s books published before the Second World War are largely inaccessible today – they have not been republished and sometimes there are only a few copies in libraries, making studying difficult. Thus, one of the aims of the corpus is strategically to expand the representation of hitherto marginalized works, making them available for research.

The third sub-period (1940–1989) covers the timespan during and after the Second World War until the restoration of independence. This sub-period is the longest and thus is represented by the most authors in the corpus. Although women writers were writing and publishing their works both in Soviet Latvia and in exile, for the purpose of this study, texts written in exile and those written in Soviet Latvia are not separated, striving to view Latvian literature as a whole. The last sub-period, compared with the previous ones, is the shortest (1990–2002); therefore, it includes the fewest authors and texts, but given the aesthetic changes and different themes possible in literature after the Soviet censorship was lifted, even this small sample can bring valuable insights.

Table 1. Periods, number of authors, number of texts, and words per period. One author can be represented in the corpus in several time periods.

|

Period |

Authors |

Texts |

Words |

|

1893–1917 |

12 |

58 |

160,155 |

|

1918–1939 |

32 |

100 |

343,880 |

|

1940–1989 |

41 |

83 |

383,255 |

|

1990–2002 |

7 |

17 |

37,710 |

In constructing the corpus, we aimed to provide a comprehensive and representative overview of Latvian women’s writing by including a wide range of authors, as per Underwood’s (2019, p. xx). definition of distant reading as a means of understanding the contrast between samples drawn from different periods or social contexts rather than recovering a complete archive of all published works. Therefore, texts by both well-known women writers (Aspazija, Brigadere, Regīna Ezera, etc.) and lesser-known authors (Anna Rūmane, Angelika Gailīte, Erna Ķikure, etc.), as well as those who published only in periodicals and are not even mentioned in the history of literature (Anna Daugaviete, Ženija Pētersone, Irēne Blūmfelde, etc.) were included.

When creating the corpus of Latvian women writers’ short fiction, it was particularly important to represent authors whose works have been forgotten and have yet to attract any interest from literary scholars. Thus, the process of creating the corpus became an exploratory work, searching for texts by women writers in periodicals, as well as working with rare copies of women’s short prose collections in the library. Given that women writers who published before the Second World War, for various reasons, were erased from literary history after the war and during the Soviet occupation, the interwar period (1918–1939) in particular due to women’s higher literary productivity than the earliest sub-period is represented in the corpus with a proportionally higher number of words than the following sub-period, which is the most extensive (1940–1989).

Body in women’s writing

The wish to re-situate women in the history of cultural production has also led toward a focus on the female body. “The book has somehow to be adapted to the body,” writes Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own (Woolf, 2000, p. 78), underlining the relationship between fiction and gender and suggesting that a writer’s physical conditions play a major role not only in the development of her literary career but also influences the form of her work,

women’s books should be shorter, more concentrated, than those of men, and framed so that they do not need long hours of steady and uninterrupted work. For interruptions there will always be.

Again, it should be noted that Latvian women writers’ prose was for a long time dominated by short forms, which are less time demanding and thus more possible to combine with domestic duties and other responsibilities.

While writing is mediated by the body, at the same time, it is also a space to explore and take ownership of the body. By foregrounding the interactions of body, language, and subjectivity, S. de Beauvoir’s (1949) idea of embodied subjectivity was further developed by H. Cixous (1976), L. Irigaray (1985), and J. Kristeva (1980), among others, proposing feminine writing practices that are based on the interaction of language and the body – écriture féminine – they emphasized the materiality of language and created a space for the critical evaluation of established meanings. Cixous was particularly concerned with disrupting Western binary oppositions such as mind/body, which are directly related to male/female and also implicitly hierarchical. She believed that language that prides itself on its relationship to the body would help to break this classical opposition and allow writing to take on a new material dimension:

where the repression of women has been perpetuated... where woman has never her turn to speak – this being all the more serious and unpardonable in that writing is precisely the very possibility of change, the space that can serve as a springboard for subversive thought, the precursory movement of a transformation of social and cultural structures (Cixous, 1976, p. 879).

The focus on the body can also be seen as a strategy to overcome the alienation of women from writing, which was previously seen as a male-dominated discipline. However, feminist critics have argued that bodies and body parts cannot simply be seen as natural objects but must be viewed in relation to the historical, social, and cultural forces that have shaped their representation. The body is a site where discourse and power relations are simultaneously marked, embodied, and countered, and where identities are performed and constructed. Feminist interest in the body has influenced literary studies in various ways – by studying literary texts in different historical periods, by exploring particular genres, or by focusing on the representation of specific bodily experiences.

The body has also been explored in digital literary scholarship (Mahlberg, 2013, Johnsen, 2017). Underwood (2019, pp. 124–125), using computational methods and discussing volumes of English poetry and fiction across several centuries (1700–2000), points to a broad trend that “description of the human body becomes steadily more important in fiction” as a part of the growing emphasis on the physical description in general. Notably, he identifies that “bodily description is never quite as central for men as it is for women” thus highlighting importance of the corporeality in texts by women writers. In the next section of the article, the corpus of women’s short prose will be examined for the distribution of body words, asking what otherwise invisible patterns or relationships are revealed by the level of abstraction offered by quantitative methods. Moreover, is it possible to speak of an upward or a downward curve in the distribution of body names in certain time periods?

Detecting body words in a text corpus

This research compiled the list of body words by including all commonly used nouns to describe the body and its parts in everyday Latvian language. The decision was made to limit this list to nouns describing body parts to maintain simplicity and clear focus. Although it could be argued that other parts of speech and linguistic constructions, notably verbs related to bodily actions, can convey significant semantic information reflecting attitude towards the body, a more sophisticated methodology which goes beyond the computational methods used for this pilot study would be required to consider these linguistic constructions.

The initial list of body words (in total 44 words) was divided into four groups for greater structural clarity: the first group contains words referring to the full body, the second group consists of different body parts, the third group includes the head and all the different parts of the head, and the fourth group is miscellanea – body-related words which do not clearly belong to one of the first three groups. Most of the nouns describing body are used both in singular and plural in the texts; here, we list words in nominative case and singular, unless the plural is more often used for the particular word:

(1) body, flesh, stature, torso, limbs (ķermenis, miesa, augums, stāvs, locekļi)

(2) breasts, abdomen, sides, back, lap, arm, hand, wrist, finger, armpit, palm, shoulder, elbow, leg, knee, foot, heel, hips, thighs (krūtis, vēders, sāni, mugura, klēpis, roka, plauksta, pirksts, paduse, delna, plecs, elkonis, kāja, ceļgals, pēda, papēdis, gurni, gūža / ciska)

(3) head, neck, face, forehead, cheeks, chin, eye, eyelid, eyebrows, mouth, lips, teeth, ear, nose, nostrils (galva, kakls, seja, piere, vaigi, zods, acs, plakstiņš, uzacis, mute, lūpas, zobi, auss, deguns, nāsis)

(4) hair, curls, breath, skin, pulse (mati, cirtas, elpa / dvaša, āda, pulss)

In order to keep the list concise and maintain a clear structure for the pilot study, the decision was made not to include bodily fluids (blood, spit, puss, etc.) in the body word list. Also, Latin medical terms of body parts which are not part of everyday Latvian language are not included in the body word list. It is also worth noting that authors might use metaphors, idiosyncratic expressions and other circumspect means to refer to body parts or bodily actions which are not part of the accepted linguistic lexicon of the normative language; such creative references to body eludes our body words list and computational search for keywords, emphasizing the importance of close reading and domain expertise. All these examples illustrate that the operationalization process during which researchers arrive at the research question to measurable indicators (in this case, body words) usable by computational methods of digital humanities is not a purely technical but includes conceptual and epistemological decisions which leave their mark on the computational results.

The linguistic processing of texts to get all instances of body words was done using the natural language processing pipeline from nlp.ailab.lv (Znotiņš, Cīrule, 2018), developed by the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory of the University of Latvia, Institute of Mathematics and Computer Science. First, all words in 259 texts were converted to lemmatized forms and part of speech tags acquired for every word. As the Latvian language is morphologically rich, this step was necessary to disambiguate between multiple homonymous tokens.4

The processing yielded 18,855 instances of body words across all corpus of 259 texts. To ensure no significant number of body words was missed by the morphological parser, word forms that included other post-tags, like verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, were also checked. This allowed us to make sure that the process of morpho-tagging has generally been correct and make manual corrections where needed.

Upon close examination of the acquired body words in context (with five words before and five words after) using a close reading method, we observed a range of different groups among the instances found. The first group is “proper body words”, – referring to the human body and its parts in a literal sense. The second group is “idiomatic expressions”, which employ a body word, but the linguistic meaning has evolved, and the activity is not directly involving the body or its parts in a literal sense. Here we give some examples in Latvian and their literal translation in English and an expanded comment on the meaning:

pareizāki griezt nule piedzīvotam atgadījumam muguru / it would be more correct to turn our back to the experienced accident / meaning: move on and not reminisce on something bad that happened

visa pilsēta bija kājās / all the city was up on their legs / meaning: everybody in the city was agitated and ready to do something

The third group comprises body words used in a “metaphorical sense” where the distinction from “idiomatic expressions” is not always clear. However, this group often uses body words to refer to personification:

ezers gluds un plats kā plauksta / the lake was even and broad as a palm / meaning: the lake surface was even and broad as a human palm

zari kā brūni, mezglaini pirksti sliecas laukā no dziļā sniega / branches as brown, gnarled fingers were protruding out of the deep snow

The fourth group is “body words not referring to the human body”; some of them refer to animal body parts, and others are personifications:

tante aizdomīgi nopētīja krēslu tievās kājiņas / the old lady with suspicion inspected the thin legs of the chairs

droši liekat roku uz čūskas galvu / certainly put your hand on the snake’s head

The fifth group is “not a body word”, which is falsely found because of homonymy or a misrecognized part of speech by a morphological tagger. To assess how many words are not “proper body words”, a representative sample was taken of 5% of all found instances, choosing every 20th instance (in total 887 words in context) of found body words. This 5% sample was checked by close reading, assessing the found body word in its context. It provided the following distribution amongst the five categories mentioned above:

“proper body words” – 84,91%

“idiomatic expressions” – 5,21%

“metaphorical sense” – 1,06%

“body words not referring to the human body” – 1,49%

“not a body word” – 7,33%

Then 18,855 instances of total body words were further checked for common homonyms (stāvs, stāvi, stāvus, ceļš, celis, ceļgals, roku, cirta). After manual inspection, 1020 rows were removed, resulting in a dataset of 17,835 rows. As all 1020 words were removed from the group “not a body word”, the approximate distribution (of 17,835 body words) after this cleaning step is following: “proper body words” – 90,2%, “idiomatic expressions” – 5,5%, “metaphorical sense” – 1,1%, “body words not referring to the human body” – 1,6%, “not a body word” – 1,6%.

Analysis of body word frequencies and diachronic change

The analysis of the occurrences of individual body words reveals a noteworthy pattern. As shown in Table 2, “arm” and “eye” contribute to more than 30% of all body words. It could be argued that the high frequency of “arm” may be due to its instrumental role in the action, while “eye” is likely a prominent body part due to its role as the principal sensory and communication channel for humans. “Leg” appears roughly three times less frequently than “arm”, while “lip” and “mouth” are the next features of the face that appear in this list, each roughly five times less often than “eye”. The ten most frequent body words comprise 67,75% of occurrences, while the remaining 34 comprise only 32,25%.

Table 2. Ten most frequent body words in the corpus and their share in percentage

The mean frequency of body words in the entire corpus is 1.62 per 100. However, the mean frequency varies significantly between texts, ranging from 0.21 to 4.12., with a standard deviation of 0.76. Plotting body word frequencies of all 259 texts reveals that there is no specific period with higher intensity of body words, nor is there a consistent increase in body word frequency over time. Ten texts with the highest saturation of body words are distributed across all historical periods, as depicted in Picture 1.

This is a notable finding indicating that changes in body words across time are not characterized by the totality of body words used in a particular period but ask for a more nuanced reading. The aforementioned distinction between different uses of language (body words in metaphors, idiomatic expressions, etc.) might allow assuming that specific idiosyncratic decisions on body words use that mark a changing attitude towards the body in particular texts hinge on individual vivid cases and are not visibly reflected into a statistical change of the big picture. As words referring to the body also serve functional purposes in language and communication, the individual decisions of authors might not influence the statistics to an apparent effect.

Fig. 1. Relative frequency of body words per 100 words in every text of the corpus chronologically. The mean is 1.62 body words per 100 words, fluctuating from 0.21 to 4.13 in individual texts, and the standard variation is 0.76.

According to the generalized knowledge about literary history, during the Soviet period, intimate corporeality was not widely accepted in literature, including Latvian literature (Goscilo, 1993; Zelče, 2003; Kārkla, 2022). Although the description of the body above the shoulders was permissible, overall Socialist Realism pictured a “sanitized world swept virtually clean of corporeality”, occupied by “beings largely devoid of breasts, hips, thighs, loins, and genitalia” (Goscilo, 1993, p. 146). The human body was ignored, abstracted or veiled, often present, hidden in allusions, periphrases, euphemisms and other strategies, but it was not inscribed. Thus, it was expected that there would be noticeable differences in the distribution of body names in the Soviet period.

Despite the negative attitude towards overt corporeality in Soviet literature and the censorship of certain body parts and bodily experiences, the results obtained by distant reading do not support this assumption, showing no drastic decrease in the distribution of body words during this period. On the one hand, this may be due to the dominance of functional body words (“hand”, “eye”) in the corpus. On the other hand, certain distinctive short stories in the corpus which feature themes related to corporeality may have influenced the overall result due to the number of body words used in these texts, for example, Anna Sakse’s story “Māra” (1945) about a female war medic, or Vija Svīkule’s story “Dieviete pirtī” (Goddess in the sauna, 1966), where the setting is a women’s sauna.

The fact that the works of Soviet and exile writers were not separated might also have influenced the results. Although upon closer examination, the texts written in exile do not generally contain much frankness when it comes to the human body, there are a few notable exceptions that may have impacted the overall result. For example, Blūmfelde’s short story “Dejotāja” (Dancer, 1973) appears among the ten texts with the highest body word saturation. This is the only text from the period 1940–1989, indicating a relatively lower frequency of body words in texts from this period than others, as depicted in Picture 1. The presence of body words in this text, as in the works of the Soviet authors mentioned above, can be explained by the theme of the story that focuses on a performance of a dancer:

Augums saslejas, pēkšņi uzliesmo acis, tvirtā mute notrīs. Tad, it kā zvīļojošus gaismas kūļus aumaļaini plaukstās satvērusi, šķautnainām zemūdens klintīm, neticamām bēdām, dvēseles ēdām pāri tikusi, dejotāja dejo, dejotāja runā – ar augumu, atraisīto locekļu kustībām, vaibstu spēlēm un profila līnijām. Kustības dažādojas, ritmi mainās, maigo pēdu vieglie piesitieni riņķo apkārt telpai, augums šūpojas, vijas un lokās kā ūdens zāle. (Blūmfelde, 1973)5

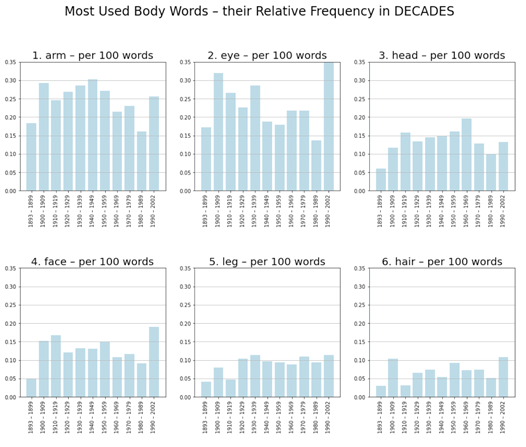

Fig. 2. Relative frequency per 100 words of most used body words (arm, eye, head, face, leg, hair) per decade.

When looking at the relative frequency per 100 words of most used body words (arm, eye, head, face, leg, hair) in Picture 2, there is a slight increase in the number of body words between the 1st (1893–1899) and 2nd decades (1900–1909) and between the 10th (1980–1989) and 11th decades (1990–2002). It is worth taking a closer look at these decades, given that these changes coincide with a time when changes are also taking place in the literary process.

The weakening of censorship in the 1980s and its abolition in 1990 provided an opportunity for greater physiological openness. The generation of women writers who entered the literary scene in the mid-1980s turned to feverish revelations of previously taboo subjects, also dealing more openly with issues of the body (Meškova, 2021; Kārkla, 2022). During “glasnost” in general, the body was rehabilitated as a means of expressive communication. According to H. Goscilo (1993, p. 149), the body “acquired formidable political and expressive powers precisely through the longevity and inflexibility of the comprehensive interdictions against it”. Compared to the previous decades, 1990–2002 shows an increase in the intensity of body words [see Table 4]. Upon closer examination, the texts that rank among the highest in terms of body word frequency for this decade (as shown in Picture 1): Aina Zemdega’s “Atgriešanās” (1994), Nora Ikstena’s “Atgadījums ar Kornēliju” (1994), and Inga Ābele’s “Nātres” (1998), feature themes related to intimate corporeality:

Kornēlija noģērbjas un spogulī redz, ka viņai ir skaistas krūtis. (..) Kornēlija sasien šalli virs krūtīm, viņai patīk asi kontrasti, un āda izskatās ļoti balta. Melnie, diegu saaustie ziedi sabirst gurnos, bārkstis, atmetušas savu lipīgo dabu, viegli pieskaras potītēm. (Ikstena, 1994, p. 6)6

Es savas rokas biju nolikusi atpakaļ, tālu pāri galvai, kur tās dega baltās ugunīs visu nakti cauri. Mēnesnīcā viņš glāstīja manu augumu ar savu skatienu, bet viņam nebij pirkstu, lai man pieskartos. (Ābele, 1998, p. 10)7

In these texts, the body is not linked to the main character’s occupation or the setting of the story, as in the previous examples. Rather, the search for female identity also means reconnecting with the physical, bodily self. Latvian women’s writing of the period is characterized by growing openness, demonstrating the recognition of the body as central to human experience (Kārkla, 2022). The examples examined here suggest that the inscription of the female body in the text, in line with Helene Cixous call for women to write themselves, opens up the possibility for further critical analysis using écriture féminine approach, which would allow speaking of deeper mechanisms of subversion and generation of textual and cultural forms in women’s writing.

Conclusion

The article represents one important part of a broader study of corpus building, which, on the one hand, is a research tool, but, on the other hand, the development of the corpus is also a research process in its own right. Given that women were initially published in small editions or their works remained scattered in periodicals, when compiling the corpus, it was particularly important to represent authors whose texts have been forgotten and thus hardly aroused the interest of literary scholars.

When examining the distribution of body words in the corpus of 259 texts by distant reading, no single distinct period with higher body word intensity stood out, nor was there a steady increase/decrease in the number of body words over time, leading to the conclusion that the distribution of body words in women’s short prose does not depend on the historical and social conditions of the period, but is rather a matter of individual authors’ style, which was confirmed by the fact that the ten texts with the highest body word saturation were found in all decades. At the same time, by applying a more nuanced reading to some of the texts with the highest body word saturation, different discursive attitudes towards the body and bodily experience could be observed.

While distant reading helps objectively to explore broader periods of literary history by offering a quantitatively grounded way of understanding texts through analysis of large amounts of data, changes in the distribution of body words over time require a more nuanced reading. The examples discussed suggested that a combination of distant reading and close reading approaches can reveal nuances and complexities of literature that cannot be revealed by distant reading alone. Thus, distant reading busing digital methodologies is only a starting point, providing useful and sometimes unexpected results that can be examined more closely with a careful reading of the texts.

Acknowledgments

The present research has been carried out within the project “Embodied Geographies: History of Latvian Women’s Writing” (No 1.1.1.2./VIAA/3/19/430).

Source code

https://github.com/haraldsDev/latvian_women_short_prose_corpus

References

Ābele, I., 1998. Nātres [Nettle]. Literatūra. Māksla. Mēs [Literature. Art. We], 32, p. 10. [In Latvian].

Beauvoir, S., 1974. The Second Sex. New York: Vintage Books. [First published in 1949].

Bergenmar, J., Leppänen, K., 2017. Gender and Vernaculars in Digital Humanities and World Literature. NORA, Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 25 (4), pp. 232–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2017.1378256.

Birkerts, A., 1912. Latviešu sieviete plašākā centienu laukā [Latvian Woman in the Broader Field of Aspirations]. Dzimtenes Vēstnesis [Homeland Herald], 79, p. 9. [In Latvian].

Blūmfelde, I., 1973. Dejotāja [Dancer]. Jaunā Gaita [The New Course], 96. Available at: <https://jaunagaita.net/jg96/JG96_Blumfelde.htm>. [Accessed 25 December 2022]. [In Latvian].

Brante, L., 1931. Latviešu sieviete [Latvian Woman]. Rīga: Valters un Rapa publishing house. [In Latvian].

Briedis, R., Rožkalne, A., 2014. Latviešu romānu rādītājs [Index of Latvian novels]. Rīga: LU LFMI. [In Latvian].

Cimdiņa, A., 1997. Feminisms un literatūra [Feminism and Literature]. Rīga: Zinātne. [In Latvian].

Cixous, H., 1976. The Laugh of the Medusa. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 1 (4), pp. 875–893.

Daija, P., Kalnačs, B., 2019. The Geographical Imagination in Early Twentieth-Century Latvian Novels. Primerjalna Knjizevnost, 42 (2), pp. 153–171. Available at: <https://www.proquest.com/openview/3ac75c80ab78b818711a1193aa83e1bb/1?cbl=1356345&pq-origsite=gscholar&parentSessionId=RVI%2BZn8OsVAJA%2FN7a4BaLLErBuYIQifZlLFVPTq%2B85M%3D> [Accessed 25 December 2022].

Ezergaile, I., 2011. Nostaļģija un viņpuse: 11 latviešu rakstnieces [Nostalgia and Beyond: Eleven Latvian Women Writers]. In: Raksti [Writings]. Rīga: Zinātne, pp. 309–546. [In Latvian].

Goscilo, H., 1993. Body Talk in Current Fiction. Speaking Parts and (W)holes. In: Russian Culture in Transition. Ed. Gregory Freidin. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 145–178.

Houston, N. M., 2019. Distant Reading and Victorian Women’s Poetry. In: The Cambridge Companion to Victorian Women’s Poetry. Ed. Linda K. Hughes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316856543.

Irigaray, L., 1985. This Sex which is Not One. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Johnsen, L. G., 2017. Body Parts in Norwegian Books. Digital Humanities. [online] Available at: <https://dh2017.adho.org/abstracts/566/566.pdf> [Accessed 25 December 2022].

Kārkla, Z., 2022. Iemiesošanās. Sievišķā subjektivitāte latviešu rakstnieču prozā [Embodied Experiences. Genealogy of Female Subjectivity in the Prose of Latvian Women Writers]. Rīga: LU LFMI. [In Latvian].

Kārkla, Z., Matulis, H., 2022. Corpus of Latvian Women Writers’ Short Fiction. CLARIN-LV digital library at IMCS. University of Latvia. Available at: <http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12574/69> [Accessed 25 December 2022].

Koser, J., 2020. Recovery and Obsolescence: Feminist Scholarship, Computational Criticism, and the Canon. Goethe Yearbook, 27, pp. 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787448612.013.

Kristeva, J., 1980. Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ķelpe, J., 1936. Sieviete latvju rakstniecībā [Woman in Latvian Literature]. Jelgava: Jelgavas Ziņas publishing house. [In Latvian].

Mahlberg, M., 2013. Corpus Stylistics and Dicken’s Fiction. Routledge.

Mandell, L., 2016. Gendering Digital Literary History: What Counts for Digital Humanities. In: A New Companion to Digital Humanities. Eds. Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, and John Unsworth. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 511–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118680605.ch35.

Meškova, S., 2009. Subjekts un teksts [Subject and Text]. Daugavpils: Saule. [In Latvian].

Meškova, S., 2021. ‘Angry Young Women’ Disrupting the Canon in Late Soviet Latvian Literature: Andra Neiburga’s Early Prose Fiction. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 22 (3), pp. 40–50. Available at: <https://vc.bridgew.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2409&context=jiws> [Accessed 25 December 2022].

Moretti, F., 2000. Conjectures on World Literature. New Left Review, 1, pp. 54–68.

Semjonova, M., 2017. Atmiņas paēnā: Latvijas un Somijas sieviešu prozas krutspunkti XX gadsimtā [Women in the Shadow: Crossroads of Latvian and Finnish Women’s Prose in the 29th Century]. Rīga: Latvijas Universitāte Akadēmiskais apgāds. [In Latvian].

Underwood, T., 2017. A Genealogy of Distant Reading. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11 (2). https://doi.org/10.1162/dhsi_a_00011. [online] Available at: <http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/2/000317/000317.html> [Accessed 25 December 2022].

Underwood, T., 2019. Distant Horizons. Digital Evidence and Literary Change. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226626971.001.0001. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Zelče, V., 2003. Dažas 60. gadu (re)konstrukcijas [Some 1960s (re)constructions]. Latvijas Arhīvi [Latvian Archives], 3, pp. 106–124. [In Latvian].

Znotiņš, A. and Cīrule, E., 2018. NLP-PIPE: Latvian NLP Tool Pipeline. Human Language Technologies – The Baltic Perspective, IOS Press. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-912-6-183.

Woolf, V., 2000. A Room of One’s Own. London: Penguin Books. [First published by the Hogarth Press, 1928.]

1 During the Soviet occupation, the state legally and politically guaranteed the equality of men and women in all spheres of life and it was out of the question to focus on women’s studies and feminist issues.

2 See the Latvian National Corpora Collection (https://korpuss.lv/en).

4 The source code of the corpus and all files of computations can be found in the github repository https://github.com/haraldsDev/latvian_women_short_prose_corpus.

5 The body is lean, the eyes suddenly flare, the firm mouth twitches. Then, as if glowing beams of light were grasped in her palms, the dancer dances, the dancer speaks – with her body, the movements of her limbs, the play of her features and the lines of her profile. The movements vary, the rhythms change, the light taps of delicate feet circle the space, the body sways, twists and bends like water grass.

6 Cornelia undresses and sees in the mirror that she has beautiful breasts. (...) Cornelia ties a scarf over her breasts, she likes sharp contrasts and her skin looks very white. The black woven flowers fall to her hips, the fringes, having given up their sticky nature, lightly touch her ankles.

7 I had put my hands back, far over my head, where they burned in white fire all through the night. In the moonlight he caressed my body with his gaze, but he had no fingers to touch me.