Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2026, vol. 16, pp. 6–26 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2026.16.1

Towards the Integration of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Dolphin-Assisted Therapy

Brigita Kreivinienė

Klaipėda University, Klaipėda, Lithuania

Dolphin-Assisted Therapy Centre of the Lithuanian Sea Museum, Klaipėda, Lithuania

E-mail: brigita.kreiviniene@ku.lt

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3316-096X

Elvyra Acienė

Klaipėda University, Klaipėda, Lithuania

E-mail: elvyra.aciene@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9680-6815

Abstract. The scientific article analyses the health care system of European countries and Lithuania in the context of complementary and alternative medicine. The article reviews the relationship between the traditions of conventional medicine and alternative and complementary medicine, patients’ attitudes towards the methods of complementary and alternative medicine, as well as dolphin-assisted therapy as one of the methods of complementary and alternative medicine. The impact on people with disabilities achieved by implementing the innovations of complementary and alternative medicine in the health system is reviewed. The aim is to investigate the links between conventional medicine and complementary and alternative medicine – specifically, dolphin-assisted therapy – through the impact on people with disabilities in implementing health system reforms. The research presents 147 interviews conducted with parents whose children with disabilities participated in dolphin-assisted therapy. The research data were processed by using qualitative content analysis. The research revealed that, from the point of view of parents raising children with disabilities, dolphin-assisted therapy is a health innovation that can be attributed not to complementary and alternative medicine, but rather to conventional medicine due to the complexity of the applied programme and methods. European Union countries treat complementary and alternative medicine methods in a different way, and the law adopted in Lithuania in 2020 opened opportunities for the development of conventional medicine and the regulation of complementary and alternative medicine, and the changes of health system reform expand the opportunities of integrative medicine for the choice of innovative methods for people with disabilities that affect the quality of life and better response to needs.

Keywords: dolphin-assisted therapy, disability, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), integrative medicine, healthcare innovation, healthcare policymaking, healthcare systems reforms.

Recieved: 2025-08-08. Accepted: 2025-12-01

Copyright © 2026 Brigita Kreivinienė, Elvyra Acienė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, the interest in animal therapy has been growing, and its benefits and value are increasingly recognized. Despite well-known criticism (Marino, 2014), dolphin-assisted therapy is increasingly being integrated into the content of medicine, rehabilitation and special education (Kreivinienė et al., 2012; Matamoros et al., 2020; Moreno Escobar et al., 2024; Kreivinienė et al., 2025). Although extensive scientific literature has already covered this topic, however, there is not much research on Human-Animal Interaction (HAI) and the explanations of the mechanisms of this interaction, and therefore it can be stated that the research base is not yet sufficiently saturated (Beetz et al., 2012; Žalienė et. al., 2018; Kreivinienė et al., 2025).

Animal-assisted therapy is one of the most recently developed methods of rehabilitation. It is a direct treatment with predetermined goals. Animal therapies focus on functional addictions, mental disorders, motor disorders, as well as situations of behavioural disorders (Radzevičienė, 2015; Žalienė et al., 2018; Taylor & Carter, 2018).

Research on the effectiveness of animal therapy confirms positive social, emotional, psychological, and pedagogical changes. The research revealed that the improvement was of a psychological (courage, openness in communication, better communication with peers) and functional (language development, better physical functioning) nature (Kreivinienė et al., 2025; Matamoros et al., 2020; Moreno Escobar et al., 2024).

Upon analysing the effects of animal therapy on humans, we find various assessments in the biomedical research space. The fact that animal therapy, despite the historical aspect that allows the animal-human relationship to be seen as a positive human-nature relationship, is still very little explored cannot be overlooked. The implementation of animal therapy research and health practice requires legal regulation that protects both the researcher and the client who chooses health services of animal therapy.

1.1 Legal Frameworks of Complementary and Alternative Medicine

The WHO policy 2030 framework “Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All”, adopted in 2019, has already emphasized the importance of cooperation between the governments and responsible institutions of the European Union states and scientists in improving public health and developing the legal framework (Jankauskienė, 2011, p. 22). One of the strategic goals of the WHO framework “Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All” is to Strengthen health systems to ensure quality and accessibility (WHO, 2022).

We can also treat the ‘accessibility’ of animal therapy by splitting it into the diversified fields of traditional medicine, education, and social support. At the same time, from late 2020, animal-assisted therapies came into the field of legal regulation of health policy, as the uptake of innovation. Recently, the results of scientists’ research and their contribution to the legislative process in the implementation of a long-term state strategy in various areas of health policy have been increasingly valued.

In this article, the authors overview and strengthen the links between dolphin-assisted therapy and conventional medicine in the context of the legal regulation of the health system. Here, dolphin-assisted therapy is a health innovation that can be attributed not to complementary and alternative medicine, but to conventional medicine due to the complexity of the applied programme and methods. However, without the search for legal frameworks of complementary and alternative medicine, it would not be possible to have such an assessment of this medical phenomenon and such a situation of dolphin therapy in Lithuania as it is today.

1.2 Legal Frameworks of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy

The experience and long-term work of the professionals of the Lithuanian Sea Museum in the field of dolphin therapy determined that Lithuania became the very first country in Europe where dolphin-assisted therapy was officially approved in 2013 as a method of wellness. Order No. V-374 of the Minister of Health of Lithuania dated 15 April 2013 approved the hygiene norm HN 133:2013 “Services of Psycho-Emotional and Physical Education Provided in Dolphinariums. General Health and Safety Requirements” (Order No. V-374 of the Minister of Health of Lithuania, 2013). The constant process of improvement impacted the review and revision of this hygiene standard, as adopted in 2025 (see LR SAM, 2025 the draft legislative act No. 25-12132).

This legal framework has played a very important role in the development of research on the effects of dolphin therapy on humans and practical activities in search of the most effective working model and methodology at both national and international levels. It can be stated that, out of the types of animal therapy, the attribution only of dolphin-assisted therapy to health services is the result of this legislation. A holistic programme of dolphin therapy, developed by the author of the article, included not only meeting the psycho-emotional, motor and sensory needs of a person with disability, but also the well-being of his/her relatives, which allows to see actual approaches of integrative medicine. In dolphin-assisted therapy sessions, professionals work with people with a variety of disorders ranging from autism, various developmental disorders to cerebral palsy (see Kreivinienė, 2011; Kreivinienė & Mockevičienė, 2020; Kreivinienė & Paone, 2023; Kreivinienė et al., 2025 and etc.). The sensory, motor and psychoemotional/psychosocial impact of dolphin-assisted therapy has been proven by pilot studies, and methodological guidelines for the implementation of practical activities have been developed.

According to the hygiene norm HN 133:2013 approved by the Republic of Lithuania, dolphin therapy involves specialists in biomedicine, medicine and social field who know the specifics of animal welfare and the person with disability (Order No. V-374 of the Minister of Health of Lithuania, 2013). Specialists of the Dolphin-Assisted Therapy Centre of the Lithuanian Sea Museum, in pursuit of the optimal result, have expanded the field of cooperation; they have been cooperating with specialists working in the client’s living environment – speech therapists, psychologists, social workers, family doctors, which, once again, confirms the importance of the integrity of medical and social services. Dolphin therapy in the Lithuanian Sea Museum has always been and is being developed as a scientific programme, and therefore, the joint work experience of a team of scientists and specialists is essential here (Kreivinienė & Žalienė, 2015). The aforementioned very first animal-assisted therapy defining Lithuanian hygiene norm HN 133:2013 opened the opportunities for further legal searches. However, many years later, Lithuania started to legislate and regulate complementary and alternative medicine on a scientific and legal basis (LR Seimas, 2020). The concept of complementary and alternative health care was not defined, either, and health services were not indicated in the Classification of Economic Activities. In 2014, the Department of Coordination of Non-Traditional Medicine Initiatives was established under the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Lithuania, one of the initiatives of which was the initiative of priority law enforcement – notably, to regulate the practice of non-traditional medicine as a construct of the assessment of the expected impact of legal regulation (Impact assessment of legislative initiatives, 2015). The aim of the initiative is to prevent unsafe services of the practice of non-traditional (complementary and alternative) medicine that can harm human health by creating a legal and safe environment of this activity for both service providers and consumers.

Option 1, which defines the concept of non-traditional medicine (CAM), was particularly important in this document, a new subclass of this activity was defined by CEA code 86 “Human Health Care and Social Work”, the scope of the activity of non-traditional medicine (CAM) and the nomenclatures of its groups, subgroups or services will be determined (see Annex 1 to the Certificate).

The Department of Parliamentary Research of the Seimas (i.e., the Parliament) of the Republic of Lithuania (hereinafter – DPR) performed a detailed analytical informational work “Regulation of Non-Traditional Medicine in the European Union” (see Annex 7 to the Certificate), which revealed that different methods of non-traditional medicine (CAM) have been legalized in EU countries. The legal regulation of the services in question differs substantially from one EU member state to another, although similar trends cannot be ruled out. The countries of the European Union also address the issues of qualification and licensing of specialists using the methods of non-traditional medicine (CAM) in different ways. It is a feature of EU countries that the practice of scientific medicine is always legally regulated, although various types of non-traditional medicine (CAM) are also tolerated to a certain extent. In some countries (e.g., Austria, Greece, Italy, France), the activity of individuals practising non-traditional medicine (CAM) is regulated by means of independent or state-sanctioned self-regulation. A voluntary register of providers of non-traditional medicine (CAM) services is available in Denmark and the United Kingdom to increase the protection of users of such services. In most European countries, state supervision is exercised of the regulation of medical practice, and consequently, the legal norms clearly define which methods of non-traditional medicine (CAM) can be used in the activity of healthcare professionals. In Central and Southern Europe, non-traditional medicine (CAM) is also allowed to be practised by doctors, and some methods are allowed to be practised only by doctors (for instance, in Slovenia, acupuncture, homeopathy, chiropractic, and osteopathy are allowed to be practised only by doctors); whereas, in Hungary, only doctors can practise homeopathy, anthroposophical medicine, traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture, chiropractic, osteopathy, ayurveda and traditional Tibetan medicine).

Meanwhile, in Northern Europe, non-traditional medicine (CAM) is mainly practised by people without medical education. In these countries, health care professionals are allowed to perform special medical procedures and treat serious illnesses, and other medical practices (such as non-traditional medicine (CAM)) are not subject to strict restrictions according to the list of regulated activities approved in the region. Only doctors with a university degree are allowed to treat infectious diseases, perform surgeries, anaesthesia, injections, radiographs, and prescribe medications. Legislation on non-traditional medicine (CAM) in some countries stipulates that this activity may be practised by both legal and self-employed persons (e.g., in Romania, Slovenia).

After evaluating the experience of various countries, the obtained results of scientific and expert activities, the legislative process initiated by the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Lithuania, in 2018, a draft Law on Complementary and Alternative Health Care was prepared, which, after lengthy discussions in the medical, scientific, legal and other professional communities, various professional organizations, has been submitted for approval. The Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania, on 14 January 2020, approved the Law on Complementary and Alternative Health Care (CAHC) No. XIII-2771, which took effect from the 1st of January, 2021. With this law, the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania regulates the frameworks of the functioning of complementary and alternative health care in the Republic of Lithuania. The adopted legal act regulates the authorization of complementary and alternative health care activities of legal and natural persons: the right to provide permitted complementary and alternative health care services; procedures for the issue, review, suspension and revocation of permits for complementary and alternative health care institutions. A separate chapter of the law is devoted to the establishment of rules for the assessment of complementary and alternative health care products, animals and other living organisms used in the provision of complementary and alternative health care services. In it, one of the groups in the field of health improvement services of complementary and alternative health care defined by law is a group of services in the field of folk medicine with one of the subgroups: a subgroup of services in the provision of which animals are used (see Chapter 2, Article 3, Part 2). With the enactment of the law (2021), subsidiary legislation was actively developed (see LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministro įsakymas dėl HN 135:2020), including rules for the assessment of animals involved in the therapeutic process (see LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministro įsakymas 2020, No. V-2634), descriptions of therapists (LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministro įsakymas, 2020, No. V-2701 and the creation of postgraduate study programs at universities for training specialists of this type.

In summarizing this part, it is necessary to pay attention to the fact that Lithuania, as a member of the WHO, based all its legislative activities in the field of health policy on WHO documents (directives, programmes, strategies). It coincided that the WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy for 2014–2023 was developed in parallel with the Lithuanian complementary and alternative medicine initiatives, which was highly favourable for the Lithuanian health policy makers within the future prospect to the goals for 2030. WHO documents provide information, context, guidance and support to health policy makers, health promotion and health service planners, public health professionals, traditional and complementary medicine communities and other stakeholders on traditional and alternative medicine, existing or planned innovative practices, approaches of specialist training. The new strategy encompasses many stakeholders in the health initiatives and opens up new opportunities to solve the problems related to the evaluation, regulation and integration of traditional and complementary medicine into the health care system as an expression of integrative medicine. The WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy for 2014–2023 summarizes all the experience gained in the process of implementing the previous strategies (2002–2005, 2004–2007, 2008–2013), assessing both the positive and negative aspects of this process (WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy, 2014–2023, p. 17).

The WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy for 2014–2023 clearly expresses the idea of national health policy autonomy, which provides opportunities for the flexibility of legal regulation for all European countries, including Lithuania, in the contexts of EU health policy, taking over the advanced and innovative practices of various countries in the field of complementary and alternative medicine. The newly launched WHO health strategy 2030 continues this perspective with the vision of involving intersectoral action by multiple stakeholders. This also presupposes a cooperative need to share the impact of the methods of complementary and alternative medicine on the human organism and the individual’s social network at both national and international levels, thereby developing best practices for integrating the methods of complementary and alternative medicine into conventional medicine.

2 Materials and Methods

In this article, the authors used qualitative research for the analysis of empirical research because qualitative research allows to study situations and events in the natural environment, which responds to the aspiration to describe and understand any phenomenon, revealing the expression of the quality of various senses and experiences avoiding digital meanings. According to Žydžiūnaitė and Sabaliauskas (2017), a researcher who needs a qualitative approach to his/her researched phenomenon must manage research strategies, because qualitative research includes studies about individuals. It is based on interviews and observations which help to identify the person’s internal psychological and behavioural characteristics in specific contexts and situations. This is especially important in conducting research in animal-assisted therapy programmes.

Longitudinal data were gathered from the Dolphin-Assisted Therapy Centre opening. Therefore, qualitative research was performed in 2015–2024 at the Dolphin-Assisted Therapy Centre of the Lithuanian Sea Museum. In a qualitative study, 147 parents (7 from Poland, 32 from Latvia, 1 from Russia, 3 from the UK, 1 from Estonia, and 103 from Lithuania), who raise children with disabilities and took part in therapeutic sessions with dolphins for two weeks, participated in a semi-structured interview. Purposive criterion sampling of the respondents was used according to three essential criteria:

• The children of all the respondents participated in a two-week complex dolphin-assisted therapy programme;

• Children participating in the programme were aged 5 to 12 years at the time;

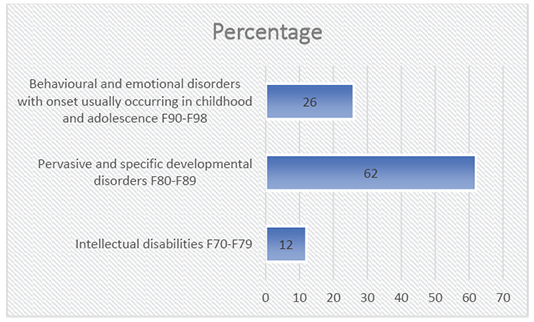

• All the respondents’ children who participated were diagnosed with ICD-10-CM: intellectual disabilities (F70–F79); pervasive and specific developmental disorders (F80–F89), and behavioural and emotional disorders with an onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence (F90–F98).

• Parents were willing to participate in research.

The criterion-based sampling method is very efficient; thus, quality data can be collected (Rupšienė & Rutkienė, 2016; Robinson, 2014). This method is useful as far the researcher decides what needs to be known and sets out to find people who can and are willing to provide the information by virtue of knowledge or experience (Etikan, 2016). The data were collected from the parents who provided information on changes in their children during the dolphin-assisted therapy and one month after completing the dolphin-assisted therapy, when the family returned to their place of residence. A total of 147 interviews were collected in this period about 62 girls (42%) and 85 boys (58%) with disabilities. The respondents’ children were diagnosed (see Figure 1) with ICD-10-CM: intellectual disabilities (F70–F79) – 12 percent; pervasive and specific developmental disorders (F80–F89) – 62 percent, and behavioural and emotional disorders with an onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence (F90–F98) – 26 percent.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the children of the respondents who participated in the complex dolphin-assisted therapy programme by disorder groups

Complex dolphin-assisted therapy for these children was implemented in accordance with the rules of good clinical practice. Each of the children received a 2-week intervention: 10 therapeutic sessions with dolphins 30 minutes each and neuro-sensory-motor function activities lasting 30 minutes three times per week (i.e., six sessions in total) after the dolphin-assisted therapy. They were provided at the Dolphin Therapy Centre’s sensory integration laboratory which has been adapted for carrying out activities of vestibular, proprioperceptive and tactile intervention. During the first week, the participants attended: five dolphin-assisted activity sessions in the water lasting 30 minutes each, conducted by a specialist and assisted by 1–3 Black Sea bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus ponticus); additionally, three times per week, individual neuro-sensory-motor interventions were carried out in the laboratory lasting 30 minutes each, delivered according to the testing results on the day of the arrival. The water pool where the neuro-sensory-motor interventions were held had a capacity of 60 m³ and an area of 55 m², with its depth ranging from 0.40 cm to 1.50 m. The neuro-sensory-motor intervention sessions assisted by dolphins were organised while considering individual testing results, stimulating purposeful interventions of the vestibular, proprioperceptive and tactile systems. The activities in the water were arranged in compliance with the animal welfare principles and applying positive reinforcement for the animals. A two-day break was made after the first week, and the same activities like those on the first week were organised on the second week as well. The programme of individual activities was designed in compliance with the main aspects of the development of sensory systems. The general principles of intervention were as follows:

• Gradual transition from a horizontal body posture to a vertical posture (from lying to sitting; from sitting to all-fours and/or standing);

• Performance of the movements on stable ground and gradually moving to unstable ground;

• Training of balance while changing the size, height of the ground and gradually involving more complex exercises requiring coordination of movements;

• Correction of pathological movements and teaching on correct movements in daily activities;

• Increasing social competencies;

• Increasing verbal language;

• Feeling the boundaries of modulation;

• Modulating emotions;

• Stimulation of functional independence;

• The activities were held in compliance with the principles of movement control and movement development.

The texts of the interviews were grouped into topics (see Table 1), and the topics were subdivided into categories, which were expanded into second-level categories, and content analysis then was performed (Henwood & Pidgeon, 1994). Open coding was applied, writing notes and titles in the transcribed interview text (Elo & Kyngä, 2008). The subcategory is accompanied by a number in parentheses indicating the respondent’s statement about the child’s condition, for example, (R5).

Таble 1.

Interview topics

|

I. Retrospective of the child’s condition and situation. |

|

The respondents are interviewed from the moment they choose to speak until they arrive for dolphin-assisted therapy: disorder, the condition of the child before the participation in the complex dolphin-assisted therapy, the main problems that led the parents to come to the complex dolphin-assisted therapy. |

|

II. Assessment of the change of the child’s condition in neuro-sensory-motor functions. |

|

The respondents are interviewed about the observed qualitative and quantitative changes in the child’s condition from the first day of the participation in the complex dolphin-assisted therapy programme to 2 weeks after its completion. |

The constructs of the research, despite a large sample, reflect the subjectively experienced world of the respondents who participated in the research – in terms of the change in children subjectively seen by them and the observed outcomes, and therefore they cannot always be generalized (Moilanen, 2000). For this reason, the reliability of research is constructed through the creation of the respondents’ realities (Newton, 2009). Foucault (1999) states that for ages nobody wanted to listen to or hear people with disabilities, as they were considered meaningless. Recently, however, there has been a growing interest in various sections of disability, according to Gudliauskaitė-Godvadė et al. (2008), qualitative research opens up the possibility of ‘giving a voice’ to people and revealing their individual experiences.

3 Results

The results of the research are summarized in Table 2. The research data present the so-called reality par excellence, which the respondents talk about – how they see the condition of their children before participating in the complex dolphin-assisted therapy programme and what has changed after its application and was still changing two weeks before the interview. The respondents talk about pluralistic contexts, the necessary help and the impact of complex dolphin-assisted therapy, name the changes observed both during the therapy itself and after returning to their daily lives.

Таble 2.

Statements illustrating the results of the research

|

Category |

Subcategory |

Number of statements |

Illustrating statements |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Retrospective of the condition of the child with a disability |

Psychosocial condition |

142 |

“Her social contact is very weak – eye contact is minimal” [R43]. “Her eye contact is very low... she is usually grumpy, in a bad mood, very non-autonomous, she seems all the time to be in ‘her own’ world” [R72]. |

|

Motor condition |

53 |

“He has a severe developmental delay, such a disturbance of movement can be seen, especially coordination and balance” [R1]. “It can be seen when walking it looks like the feet are ‘stretching’. These movements are very limited, not coordinated” [R16]. |

|

|

Sensory symptoms |

147 |

“Very low self-confidence, something like very low self-esteem” [R142]. “Can’t even say if feels bad. It would be good to say – ‘headache’, ‘bellyache’ or so” [R22]. |

|

|

Assessment of the condition of a child with a disability after complex dolphin-assisted therapy |

Psychosocial condition |

144 |

“We notice that a discussion appeared, what has never happened before – interest in new activities, new words, for example, we discuss what the difference between ‘allergy’ and ‘energy’ is, the dialogues on various topics appeared” [R11]. |

|

Motor condition |

15 |

“Coordination and balance have improved significantly” [R19]. “He is now taking the initiative himself to dress up, to put on shoes. Nervousness is reduced if something fails” [R61] |

|

|

Sensory symptoms |

147 |

“Everything improved significantly. For example, more spontaneity emerged. You can see that he is interested in the environment: in the cafe he chooses the type of juice himself and it’s easier for him to decide, he expresses desires more boldly… Or decides on a menu” [R3]. “Echolalia, saliva accumulation, and rolling in the mouth decreased. He is less ‘obsessed’ on some item, pays more attention to the environment where he is” [R113]. |

|

|

Dolphin-assisted therapy as complementary and alternative medicine |

Integrative medicine |

53 |

“I share my experience here through all sorts of social networks because it’s best not to spend money somewhere on all sorts of other rehabilitations, but here because there is a clear impact” [R22]. “I would definitely go again because, obviously, the child has improved as much as we have not achieved [anything similar] in other rehabilitations in many years” [R63]. |

|

Health innovation |

123 |

“I find it incredible how specialists work here with a child – so young, but come up immediately, start talking, everyone knows you, it seems that we have been here for a hundred years” [R18]. “I was very impressed that, after each therapy – whether on water or on land, the specialist tells so in detail, explains, shares what was successful, what the goals [were], what was not successful, what will be tried further. Definitely impressing” [R14]. |

The research revealed that almost all families raising children with mental and behavioural disorders look for complementary and alternative methods of help. The vast majority of the respondents consider dolphin-assisted therapy as part of integrative medicine and position the understanding that ‘treatment’ and ‘rehabilitation’ are applied here, ask about “reimbursement of procedures from health insurance funds”, it is likely that parents participating in the state support system (sanatorium, rehabilitation services) see most of the repetition of this formal support. Almost all the interviewees stated that, when participating in complex dolphin-assisted therapy, they observe the close relationship between the professionals and the child, the close attention of the professionals to parents, and the uniqueness of the dolphin’s communication with the child. According to the respondents, by participating in therapeutic sessions, it is possible to ‘rediscover’ a child with a disability, it seems like there is no longer a constant ‘struggle’ for the child’s well-being – he/she is accepted here, he/she is treated in a quality manner, his/her individual needs are assessed. Some respondents stated that their expectations regarding the child’s changes were realistic, and that they did not expect a miracle, but there is a lack of competent specialists, a lack of innovative care methods, and also there is the need for comprehensive care in the state medical care system. The interviews revealed that, for many families participating in the complex assistance, this programme is like relaxation after a tense period of life – everyone is especially looking forward to the first meeting with dolphins. Interestingly, the respondents say they were particularly afraid of the first meeting with the dolphins, it was unclear how the programme would be going, and, when they ultimately came, their anxiety subsided, they became very proud of their child that he/she managed to integrate perfectly in communication with dolphins, specialists, and overcame challenges in complementary programmes for neuro-senso-motor skills.

4 Discussion

The lowest share of the respondents participating in the research were raising children with intellectual disabilities (F70–F79), i.e., only 12 percent, meanwhile, the majority of the respondents were raising children with pervasive and specific developmental disorders (F80–F89) – 62 percent, and behavioural and emotional disorders with an onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence (F90–F98) – 26 percent. According to research, the same is true for complementary and alternative medicine services – complementary help in addition to medical, social, and pedagogical help is most commonly sought for children with behavioural and emotional disorders (Sandler et al., 2001).

Summarizing the results of the research, three main categories were distinguished: the category retrospective of the condition of the child with a disability, with subcategories: psychosocial condition, motor condition, sensory symptoms; the category assessment of the condition of a child with a disability after complex dolphin-assisted therapy, with subcategories: psychosocial condition, motor condition, sensory symptoms; the category dolphin-assisted therapy as complementary and alternative medicine, with subcategories: integrative medicine, health innovation. It can be stated that the respondents were able to identify very precisely the needs of the participating children with disabilities as well as the changes after the complex programme of therapeutic sessions.

Regarding the category retrospective of the condition of a child with a disability, the respondents singled out the most problematic areas, as almost all the respondents talked about the problems of psychoemotional condition and sensory symptoms. The research by Salgueiro et al. (2012) and Taylor and Carter (2018) showed that similar problems were also identified by parents who participated in quantitative research and whose children received dolphin-assisted therapy. The respondents mention the most common psycho-emotional problems, such as lack of eye contact, delay of linguistic development, emotional stability or amplitude of emotional expression, and reactivity to the social context in everyday life:

“Proactively does not use language at all. Usually just repeats the commercials – the same and the same. He can’t even start talking to people, there’s no communication at all, he won’t tell even if something is wrong” [R30].

“He likes the home environment very much – as soon as he leaves it – [he] closes [in], avoids contact with people” [R25].

“He started having depression. Very passive, no eye contact, very annoyed by smells, sounds, often cries, asks everyone for help. Sometimes it’s even hard to get him out of that trance state, he doesn’t even respond to his name” [R12].

The observed problems of motor condition – motor planning, initiation of action, etc. – were named by one-third of the respondents, although this is the least noticeable problem of the respondents, for which complex dolphin-assisted therapy is sought:

“Her movement coordination is impaired, but, at school, teachers say there are nervous tics as well” [R43].

“Her hands are as if paralysed because of tension – she keeps her fingers in a fist” [R19].

“He has a complex disability – walking is also disturbed, his development and fine motor skills are delayed. There seems to be no perception of the environment, no orientation” [R113].

Similar problems are mentioned in the works of other researchers, when parents name these motor problems as the reason for applying for dolphin-assisted therapy (Salgueiro et al., 2012; Nathanson et al., 1997; Nathanson, 1998; Stumpf & Breitenbach, 2014).

The respondents mention a lot of sensory needs when talking about sensory problems, and all the respondents named certain sensory problems that manifest by psychological, social, motor, emotional symptoms:

“At this age, he does not yet know how to read or write” [R5].

“A very frequent change of emotions (...) sometimes is stubborn and lies on the floor – wants neither to go nor stand up” [R8].

“He’s so sad... especially lately, often even angry, he speaks very little... he usually does what he likes – so he sits and cuts with scissors during the day” [R100].

“He coughs very much, wheezes, constantly moves, walks on his toes (...) well he doesn’t listen to an adult at all, a very complicated interaction. For example, sits, sways and sings the same song for himself. Sings...sings... sings and so the same and the same. Very many echolalias, and another big trouble is that he puts a lot of food in his mouth. He needs to be controlled all the time so that he doesn’t choke” [R115].

According to the authors Bundy and Murray (2002), children and adults with mental and behavioural disorders are often accompanied by sensory needs that need to be addressed in order to function better in society.

The respondents, when speaking about the category of assessment of the condition of a child with a disability after complex dolphin-assisted therapy, named essentially the same changes which they mentioned at arrival – they shared what changes they are observing, and how it changes their life as a family. Therefore, the following subcategories were distinguished: psychosocial condition, motor condition, and sensory symptoms. When speaking about the changes in psychosocial condition, they named: linguistic development, reduction of stereotypes, understanding of language, reduction of contradictory behaviour, better orientation in the environment and space, better concentration of attention, reduction of fears:

“Eye contact greatly improved. Immediately almost after the first session, we noticed a decrease in singing, he began to react to what I was saying – he turns around, does it. No more stuffing as much food into the mouth as before, he started dosing” [R115].

“His behaviour has improved significantly, he no longer objects so much, he seems to be more tolerant of change. He began to repeat more words, he seems to use them more purposefully. For example, he turns around and responds when you call him” [R141].

“In fact, he was very tired after the therapy, but very joyful, happy, he became so very positive, it seems that the child was changed. He is now basically so more positive and even performs tasks more willingly – he doesn’t resist as much as before” [R100].

“No longer afraid of darkness and adults” [R14].

Similar changes have been identified in studies by other authors (see Nathanson et al., 1997; Nathanson, 1998; Stumpf & Breitenbach, 2014; Griffioen & Enders-Slegers, 2014; Matamoros et al., 2020), although, in some research, no improvement in overall autism scores has been observed (Salgueiro et al., 2012).

Only 15 respondents pointed out changes in the motor condition, although about one-third of them described the symptoms. The research by Salgueiro et al. (2012) confirms such findings, and the research conducted by the authors revealed a statistically significant change in fine motor skills and verbal development after the dolphin-assisted therapy. The respondents mainly name the changes they noticed as changes in psychomotor skills – when they mention the child’s relaxation due to emotional stability, less muscle tension, better independence due to better motor planning, and self-empowerment in the environment:

“She smiles at me again every day, communicates... the language itself is so more significantly clearer and significantly more language than it was. After dolphin therapy she tells me about dolphins every day, would like to come back again very much, wants to visit them terribly. We even observe that the fingers of the hand seem outstretched, it is no longer as before that she is so worried about everything and her hands are in fists again” [R19].

“He became more agile, more confident, we even see that he started looking for communication with other children himself. He would never swing – he would run away just as soon as he saw the swing, and now he started to like the swing, we even started to teach him to ride a bike. The strangest thing is that he willingly goes to kindergarten, the educator said that more friendships were created” [R14].

Similar results were obtained in a study by Antonioli and Reveley (2005), which found greater relaxation in clients and a marked reduction in anxiety when assessing depressiveness. Physiological study of the dolphin as a relaxing factor in humans also confirms these results (Birch, 1998; Kreivinienė et al., 2025; Matamoros et al., 2020).

The reduction of sensory symptoms was assessed and noticed by all the respondents – the use of two hands, independence, emotional stability, tolerance of innovations, ability to wait, listen to instructions, motivation, better adaptation to unexpected situations, improved mood, sleep quality, etc. were mentioned:

“He became more relaxed, bolder, and became more interested in group activities” [R100].

“Started to use very many gestures, wants to express himself, and also that communication has become so more specific, in the sense that gentle endlessly” [R101].

“Walks, reads the names of the streets, began to enjoy walking different routes... we no longer need permanent notes when we want to change something. Now – we decided – we turned around and we are going the other way. Even started to taste new food, which was not the case before” [R106].

“No more drinking from a bottle, now just from a cup. Observes playing children and joins them specifically” [R8].

“He became more curious... He willingly climbs the stairs by himself, he is so much more positive than he used to be… Instead of high body tensions, only such twisting of fingers remained” [R135].

“You can see that self-esteem has changed significantly, he has even become consistent in his stories, self-confidence emerges in new situations” [R142].

Similar changes were recorded in the scientific study by Griffioen and Enders-Slegers (2014). It can be discussed that dolphin-assisted therapy also has an additional therapeutic effect due to the client’s being in the water. After all, water therapy has a positive effect on many components of human activity: the control of breathing and its regulation, body stability and mobility, body rhythmicity and coordination, body firmness improve, self-esteem increases, social and emotional development is noticed. Water also allows the use of playful elements to accept a challenging stimulus (Gjesing, 2002).

In the category dolphin-assisted therapy as complementary and alternative medicine, two subcategories have been distinguished: integrative medicine and health innovation.

The respondents mostly talk about the cohesion of the state system with the dolphin-assisted therapy programme, they consider that it is a programme that gives a boost, gives them the opportunity to combine traditional physiotherapy, art therapy, sensory integration methods with dolphin-assisted therapy, everything is provided in one place with good emotions, and the effect is felt not only on the child but also on relatives:

“You see, when my child is well, I am well, too, and the whole family is well” [R53].

“She burst with joy, happy, so full of good emotions, energy, constantly talked about dolphins, so I lived through and experienced everything with her” [R19].

“The relationship with the specialist is very close… this has never been the case and has never had such authority” [R101].

“Here material is prepared, you can see that the work is methodical and purposeful according to the very individual needs, what a child needs in particular” [R120].

Almost all the respondents consider dolphin-assisted therapy to be a health innovation that ‘cures’ by innovative methods:

“Well, this is a natural treatment here because, for us, the symptoms have decreased to such an extent that no medication has helped as much as the dolphins” [R145].

“It’s obvious, the dolphins do their job one hundred percent, that’s why I tell the child to try” [R102].

“For those two weeks, it was so much fun for me to observe both the dolphin therapies and the involvement of the professionals working at the centre and their relationship with me as a father, I have never seen such cooperation in medical institutions before” [R76].

“You really feel that your child and you are so important when you see how they all know how to work in another way only to achieve positive results and better well-being” [R89].

“Of course, therapy is expensive, but we haven’t received anywhere as much help as here, so we combine work and save money to just come, because the results tangibly compensate everything. We give our all to ensure that only the child is well and that only that improvement continues. With each arrival here, we have such a big leap forward... Such a really big step” [R103].

Summarizing the presented statements of the respondents about the changes in children, it is necessary to mention that the symptoms of children with mental and behavioural disorders and their severity depend to a large extent not only on individual developmental processes but also on the formed psychosocial experience. Many authors have shown that brain development depends on experience (research by Perry, Pollard, Blakley, Baker, and Vigilante, etc.). One of the essential principles of dolphin-assisted therapy is experience and triangulation of interactions: animal-child-specialist. Recent research suggests that interpersonal interaction is an important source of sensory experience. This development takes place by interacting with others in visual, auditory, and tactile ways (as researched by Trevarthen). Therefore, a well-chosen environment, communication, way of interaction, exercise or an enriching sensory diet promote human development and improve health (Kaiser, Gillette, & Spinazzola, 2010; Wilbarger & Wilbarger, 2002; Kreivinienė et al., 2025; Matamoros et al., 2020).

5 Conclusion

The theoretical implications and research results implicate and strengthen DAT as a method of complementary and alternative medicine with attributed functions of medicine and its different branches. From the point of view of parents raising children with disabilities, dolphin-assisted therapy applied in a complex way is a health innovation that can be attributed not to complementary and alternative medicine, but, instead, to rehabilitation service due to the complexity of its methods. According to the parents, most of the changes in children were observed one month after completing the dolphin-assisted therapy – the child’s psychoemotional state changed, autonomy skills were developed, social contact with others and verbal language expression improved, and neuro-senso-motor functions improved as well. The qualitative research conducted does not construct generalist knowledge; however, the content of the analysis essentially repeats the quantitative findings of other authors (such as Nathanson, Nathanson et al; Antonioli & Reveley; Griffioen & Enders-Slegers; Stumpf & Breitenbach, etc.). Such results could be attributed towards complementary methods which could be applied next to traditional methods based on the state-run level. Despite very positive results mentioned by families we must consider possible limitations of research itself, also individuality of child, DAT basic professional qualification, etc., which should not be a basis not to discuss DAT as an alternative method to early intervention or rehabilitation services.

In Lithuania, dolphin-assisted therapy as a method of complementary and alternative medicine began to take shape in 2013, with the enactment of the Hygiene Norm HN133:2013, which served as a basis for including, regulating, and licensing dolphin-assisted therapy as a method of complementary and alternative medicine in 2020. European Union countries treat complementary and alternative medicine methods differently. The research revealed unevenness in the base of the European Union’s health system and large gaps between countries in innovation in medicine and in the fields of health policy and integrative health policy. Supposedly, the differences that have emerged, on the one hand, open the way for medical tourism, and, on the other hand, presuppose a complicated situation with regard to the opportunity for people with disabilities to benefit from the complementary assistance.

Meanwhile, this law adopted in Lithuania in 2020 opens up opportunities for the development of conventional medicine and the regulation of complementary and alternative medicine. The adoption of the Law on Complementary and Alternative Health Care marked the beginning of a new and very responsible phase of work within WHO strategy 2030, which enables the Ministry of Health to mobilize competent specialists and improve many leading orders, laws for the actual implementation of the law in Lithuania.

Thus, it can be stated that the current reform of the health system expands the possibilities of the health policy for the choice, quality and better response to the needs of people with disabilities and animal welfare. In the field of animal-assisted therapy, this adoption of the law acquires a very important moment of the protection of a vulnerable client with a disability. Licensing of this service is the strictest form of public service regulation. However, clear animal welfare and testing requirements, requirements for specialists, methods, indications and contraindications will reduce the unsafe application of animal-assisted therapy in the country and are likely to professionalise this field and refine science and practice-based methods.

Author Contributions

Brigita Kreivinienė: conceptualization, investigation, project administration, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, data curation, formal analysis.

Elvyra Acienė: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing.

References

Antonioli, C., & Reveley, M. A. (2005). Randomised controlled trial of animal facilitated therapy with dolphins in the treatment of depression. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 331(7527), Article 1231. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7527.1231

Birch, S. (1998). Dolphin Sonar Pulse Intervals and Human Resonance Characteristics. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Bioelectromagnetism (Cat. No.98TH8269), Melbourne, Australia, 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICBEM.1998.666435

Bundy, A. C. & Murray, E. A. (2002). Sensory Integration: A. Jean Ayres’ Theory Revisited. In: A. C. Bundy, S. J. Lane, & E. A. Murray (Eds.), Sensory Integration: Theory and Practice (pp. 3–20). Philadelphia: FA Davis Company.

Elo, S. & Kyngä, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Foucault, M. (1999). Seksualumo istorija [The History of Sexuality]. Vaga.

Gjesing, G. (2002). Water-Based Intervention. In: A. C. Bundy, S. J. Lane, & E.A. Murray, (Eds.), Sensory integration: theory and practice (pp. 345–349). Philadelphia: FA Davis Company.

Griffioen, R. E. & Enders-Slegers, M. J. (2014). The Effect of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy on the Cognitive and Social Development of Children with Down Syndrome. Anthrozoös, 27(4), 569–580. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279314X14072268687961580

Gudliauskaitė-Godvadė, J., Godvadas, P., Malinauskas, G., Perttula, J., & Naujanienė, R. (2009). Understanding Identity of Social Work in Lithuania. Tiltai. 44(3), 65–76. https://research.ebsco.com/c/5f64xf/viewer/pdf/iecxirxepz

Henwood, K. & Pidgeon, N. (1994). Beyond the Qualitative Paradigm: A Framework for Introducing Diversity within Qualitative Psychology. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 4(4), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2450040403

Jankauskienė, D. (2011). Sveikatos politikos vertybės ir iššūkiai artimiausiame dešimtmetyje (Health policy values and challenges in the next decade). Sveikatos politika ir valdymas: mokslo darbų žurnalas, 1(3), 7–26. https://ojs.mruni.eu/ojs/health-policy-and-management/article/view/545/508

Kaiser, E. M., Gillette, C. S., & Spinazzola, J. (2010). A Controlled Pilot-Outcome Study of Sensory Integration (SI) in the Treatment of Complex Adaptation to Traumatic Stress. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19(7), 699–720. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2010.515162

Kreivinienė, B. (2011). The representations of social support from external resources by families raising children with severe disability in connection with dolphin assisted therapy [Doctoral dissertation, University of Lapland]. Acta Electronica Universitatis Lapponiensis openAccess https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:ula-2011611139

Kreivinienė, B., & Mockevičienė, D. (2020). Dolphin assisted therapy: evaluation of the impact in neuro-sensory-motor functions of children with mental, Behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 29(4), 292–307. https://revistaclinicapsicologica.com/data-cms/articles/20200917021617pmSSCI-117.pdf

Kreivinienė, B., & Paone, M. (2023). A New Approach Towards the Acquisition of Democratic Skills in Children: Building Skills Through Training Therapy Animals. Tiltai, 91(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.15181/tbb.v91i2.2551

Kreivinienė, B., Šaltytė-Vaisiauskė, L., & Mačiulskytė, S. (2025). Therapeutic effect of proprioceptive dolphin assisted activities on health-related quality of life and muscle tension, biomechanical and viscoelastic properties in major depressive disorder adults: case analysis. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 18, Article 1487293. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2024.1487293

Kreivinienė, B. & Žalienė, O. (2015). Delfinų terapija Lietuvos ir tarptautiniame kontekste: mokslinis įdirbis ir reglamentavimas. Po Muziejaus Burėmis: muziejininkų darbai ir įvykių kronika, 4, 68-72. https://epale.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2014-epale-lt-00098.pdf

LR Seimas. (2020). Lietuvos Respublikos papildomosios ir alternatyviosios sveikatos priežiūros įstatymas. Įsigalioja 2021-07-01 (Įstatymo 25 straipsnio 2 dalis įsigalioja 2020-01-30. Įstatymo įsigaliojimas pakeistas įstatymu Nr. XIV-147). Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/8b707e404a9511eb8d9fe110e148c770

LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministerija. (2013). Dėl patvirtinimo Lietuvos higienos normos HN 133:2013 „Delfinariumuose teikiamos psichoemocinio ir fizinio lavinimo paslaugos. Bendrieji sveikatos saugos reikalavimai“ (2013 m. balandžio 15 d., Nr. V-374). Teisės aktų registras, Nr. 1132250ISAK000V-374. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/TAR.DB415FC2215C

LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministerija. (2015). Netradicinės medicinos iniciatyvų koordinavimo skyriaus Teisėkūros iniciatyvų poveikio vertinimo pažyma, priedas 1 ir priedas 7.

LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministro įsakymas. (2020). Dėl Lietuvos higienos normos HN 135:2020 „Papildomosios ir alternatyviosios sveikatos priežiūros paslaugų teikimo visuomenės saugos reikalavimai“ patvirtinimo (2020 m. gruodžio 29 d., Nr. V-3042). Teisės aktų registras, Nr. 2020-28900. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/e70ae28049c411eb8d9fe110e148c770

LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministro įsakymas. (2020). Dėl Papildomosios ir alternatyviosios sveikatos priežiūros produktų, gyvūnų ir kitų gyvų organizmų, naudojamų teikiant papildomosios ir alternatyviosios sveikatos priežiūros paslaugas, vertinimo ekspertų komisijos personalinės sudėties, nuostatų ir darbo reglamento patvirtinimo (2020 m. lapkričio 17 d., Nr. V-2634). Teisės aktų registras, Nr. 2020-24118. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/caddf75028b811eb932eb1ed7f923910

LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministro įsakymas. (2020). Dėl papildomosios ir alternatyviosios sveikatos priežiūros specialistų veiklos licencijavimo taisyklių patvirtinimo (2020 m. lapkričio 23 d., Nr. V-2701). Teisės aktų registras, Nr. 2020-24881. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/9e44e1d02e5e11eb932eb1ed7f923910

LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministerija. (2020). Lietuvos Respublikos papildomosios ir alternatyviosios sveikatos priežiūros įstatymas (2020 m. sausio 14 d., Nr. XIII-2771). Teisės aktų registras, Nr. 2020-02006. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/ab6ef080429b11ea829bc2bea81c1194

LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministerija. (2020). Dėl Invazinių ir (ar) intervencinių procedūrų, kurios nepažeidžia audinių ir (ar) organų vientisumo ir gali kelti tik nedidelį nepageidaujamą laikiną poveikį paciento sveikatai, sąrašo patvirtinimo (2020 m. vasario 14 d., Nr. V-171). Teisės aktų registras, Nr. 2020-03459. Retrieved from https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/lt/legalAct/f8832b30515411ea931dbf3357b5b1c0

LR Sveikatos apsaugos ministerija. (2025). Lietuvos Respublikos sveikatos apsaugos ministras įsakymas “Dėl Lietuvos Respublikos sveikatos apsaugos ministro 2013 m. balandžio 15 d. įsakymo Nr. V-374”Dėl Lietuvos higienos normos HN 133:2013 Delfinariumuose teikiamos psichoemocinio ir fizinio lavinimo paslaugos. Bendrieji sveikatos saugos reikalavimai´ patvirtinimo´ pakeitimo” [Teisės akto projektas Nr. 25-12132].

Matamoros, O. M., Escobar, J. J. M., Tejeida Padilla, R., & Lina Reyes, I. (2020). Neurodynamics of Patients during a Dolphin-Assisted Therapy by Means of a Fractal Intraneural Analysis. Brain Sciences, 10(6), Article 403. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10060403

Marino, L. (2014). Cetacean captivity. In L. Gruen (Ed.), The ethics of captivity (pp. 22–37). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199977994.003.0003

Moreno Escobar, J. J., Morales Matamoros, O., Aguilar del Villar, E. Y., Quintana Espinosa, H., & Chanona Hernández, L. (2024). Employing Siamese Networks as Quantitative Biomarker for Assessing the Effect of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy on Pediatric Cerebral Palsy. Brain Sciences, 14(8), Article 778. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14080778

Moilanen, P. (2000). Interpretation, truth and correspondence. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30(4), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00136

Nathanson, D. E., de Castro, D., Friend, H., & McMahon, M. (1997). Effectiveness of Short-Term Dolphin-Assisted Therapy for Children with Severe Disabilities. Anthrozoös, 10(2–3), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279397787001166

Nathanson, D. E. (1998). Long-Term Effectiveness of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy for Children with Severe Disabilities. Anthrozoös, 11(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.1998.11425084

Newton, L. (2009). Reflexivity, Validity and Roses. Complicity: An International Journal of Complexity and Education, 6(2), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.29173/cmplct8820

Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in Interview-Based Qualitative Research: A Theoretical and Practical Guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

Rupšienė, L., Rutkienė, A. (2016). Edukacinis eksperimentas: vadovėlis. Klaipėdos universiteto leidykla.

Salgueiro, E., Nunes, L., Barros, A., Maroco, J., Salgueiro, A. I., & Dos Santos, M. E. (2012). Effects of a dolphin interaction program on children with autism spectrum disorders: an exploratory research. BMC research notes, 5, Article 199, [1–8]. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-199

Sandler, A. D. N., Brazdziūnas, D., Cooley, W. K., Pijem, L. G., Hirsch, D., Kastner, T. A., et al. (2001). Counseling Families Who Choose Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Their Child With Chronic Illness or Disability. Pediatrics, 107(3), 598-601. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.3.598

Stumpf, E., & Breitenbach, E. (2014). Dolphin-Assisted Therapy with Parental Involvement for Children with Severe Disabilities: Further Evidence for a Family-Centered Theory for Effectiveness. Anthrozoös, 27(1), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303714X13837396326495

Taylor, C. S., & Carter, J. (2020). Care in the contested geographies of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(1), 64–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1455217

World Health Organization (2014). WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014-2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/92455/9789241506090_eng.pdf;jsessionid=C588D84F6B0C8E6FB9A16A08C0357B9F?sequence=1

World Health Organization. (2021). Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a framework for monitoring and evaluating progress of the road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021−2030 [Global strategy]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010352

World Health Organization. (2022). The Road to 2030. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/358468/WHO-UCN-NTD-SAI-2022.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Wilbarger J., & Wilbarger P. (2002). Clinical Application of the Sensory Diet. In: A. C. Bundy, S. J. Lane, & E.A. Murray, (Eds.), Sensory integration: theory and practice (p. 338). Philadelphia: FA Davis Company.

Žalienė, L., Mockevičienė, D., Kreivinienė, B., Razbadauskas, A., Kleiva, Ž., & Kirkutis, A. (2018). Short-Term and Long-Term Effects of Riding for Children with Cerebral Palsy Gross Motor Functions. BioMed research international, Article 4190249, [1–6]. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4190249

Žydžiūnaitė, V. & Sabaliauskas, S. (2017). Kokybiniai tyrimai: principai ir metodai: vadovėlis. Vaga.