Sociologija. Mintis ir veiksmas ISSN 1392-3358 eISSN 2335-8890

2025, Nr. 1 (56), pp. 34–53 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SocMintVei.2025.56.2

Drug Trading Locations and Criminogenic Change in a Post-Soviet City

Arūnas Acus

Klaipėdos universitetas / Klaipėda University

arunas.acus@ku.lt

https://ror.org/027sdcz20

Liutauras Kraniauskas

Klaipėdos universitetas / Klaipėda University

liutauras.kraniauskas@ku.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9343-8818

https://ror.org/027sdcz20

Abstract. The study examines the spatial relationship between drug trading locations and crime in a post Soviet urban context using location quotients and cluster mapping techniques. By analysing long term drug distribution sites in Klaipeda, Lithuania, across two periods, 2001 to 2005 and 2006 to 2010, the research evaluates changes in the concentration and structure of criminal activity in their surrounding environments. The findings demonstrate that drug trading spots exert a strong localised influence on criminogenic conditions, with crime levels near drug selling locations substantially exceeding citywide averages. While overall crime declined during the study period, the spatial concentration of violent crime intensified, particularly around socially marginalised facilities such as shelter houses and former industrial apartment buildings. At the same time, drug related activity and associated crime increasingly shifted towards spaces of conspicuous consumption, including night clubs and shopping centres. The results highlight the continued relevance of social disorganisation and routine activities theories while also pointing to a reconfiguration of crime patterns shaped by urban transformation and enforcement priorities.

Keywords: drug trade, crime geography, crime generators, spatial analysis, pos-Soviet city.

Narkotinių medžiagų platinimo vietos, jų kaita ir kriminogeninis poveikis posovietiniame mieste

Santrauka. Straipsnyje tiriamos erdvinės sąsajos tarp narkotinių medžiagų platinimo vietų ir nusikaltimų koncentracijos posovietinėje urbanistinėje aplinkoje. Pasitelkus teritorinės koncentracijos koeficientą ir erdvinių klasterių identifikavimo metodiką, analizuojama, kaip Klaipėdoje nuo 2001 iki 2010 m. kito nusikaltimų skaičius ir struktūra aplink narkotikus platinančius taškus. Duomenys rodo, kad narkotikų platinimo vietos daro stiprų lokalizuotą poveikį kriminogeninei situacijai, o nusikalstamumo lygis šalia šių vietų gerokai viršija miesto vidurkį. Nors apskritai nusikalstamumas tiriamuoju laikotarpiu mieste mažėjo, smurtinių nusikaltimų erdvinė koncentracija aplink narkotikų platinimo vietas, ypač aplink socialiai marginalizuotus urbanistinius objektus, kaip antai nakvynės namai ir buvusių pramonės įmonių bendrabučio tipo daugiabučiai, didėjo. Kita vertus, analizuojamu laikotarpiu matoma ir narkotinių medžiagų platinimo taškų slinktis į klubus ir prekybos centrų prieigas, demonstratyvaus vartojimo erdves. Kriminogeninės aplinkos ir jos permainų analizė suponuoja, kad socialinės dezorganizacijos ir rutininės veiklos teorijos vis dar išlaiko savo interpretacinę galią aiškinant nusikaltimų koncentraciją miesto erdvėse. Tačiau šias teorijas būtina papildyti naujomis įžvalgomis apie tai, kaip nusikalstamumo struktūrą keičia urbanistinės transformacijos ir kintantys teisėsaugos institucijų prioritetai.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: narkotinės medžiagos, nusikaltimų geografija, nusikaltimų generatoriai, erdvinė analizė, posovietinis miestas.

Received: 14/05/2025. Accepted: 09/11/2025.

Copyright © 2025 Arūnas Acus, Liutauras Kraniauskas. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Drug use is closely related to a wide range of criminal activities. Intoxicated people and drug users may commit crimes for different reasons. Criminologist Paul Goldstein (1985) identified three main causal connections between drug use and crime. First, crime may be committed due to psychopharmacological reactions, when the direct effect of a narcotic substance such as cocaine or methamphetamine, and especially alcohol, causes aggressive and violent behaviour towards others. Second, crimes are often committed for economic reasons, when a drug user needs to raise money to obtain drugs or alcohol. This need for money leads some individuals to commit theft or robbery. Third, crimes are also stimulated by the structural conditions of illegal drug trading. Typical examples include competition among criminal gangs for territories and markets, the use of illegally acquired weapons for self-defence by drug users or drug dealers, and robberies of people intending to buy drugs, committed by delinquent teenagers living in the neighbourhood. This means that drug trading locations can act as crime generators, a fact that has been demonstrated in many previous studies (Brantingham and Brantingham 1995a).

Alongside this interpretation of psychosocial behaviour, which localises causal connections between drugs, alcohol and crime at the level of individual action, there is a tradition in environmental sociology that emphasises the impact of the living environment on human behaviour. For almost one hundred years, studies in urban ecology have shown that drug users often live in the poorest and least safe areas of cities, where various socially marginalised groups are concentrated, such as ethnic minorities, the unemployed, the homeless, single mothers, and uneducated youth. Most crimes occur in such areas of social exclusion, transit zones, and spatial urban pockets due to weakened social control, poor community relations, abandoned urban infrastructure, and pessimism about future opportunities (Zorbaugh 1929; Faris and Dunham 1939; Wilson 1987; Pandey and Coulton 1994; Morenoff and Sampson 1997; Jean 2007; Ceccato and Oberwittler 2008). Therefore, locations of drug distribution and the physical spaces of other crimes often overlap to a significant extent.

In this article, we aim to examine criminogenic differences between drug trading locations and to answer two key questions. First, which environment is more dangerous, one where drugs are sold in nightclubs or one where they are sold near shelter houses? We seek to identify which crimes prevail in each environment and to examine the differences between these locations. Second, what is the most effective method for evaluating changes in the criminogenic environment of these areas over the long term? Here, we address a methodological issue that is rarely discussed in environmental criminology, namely how to adequately assess observed changes and how to visualise them.

Although the selected theme relates to a post-Soviet city whose urban and social structure differs significantly from that of traditional Western cities, the limited scope of this article restricts the analysis to empirical material only. Historical and social contexts of drug distribution, which reveal important peculiarities of these phenomena, are therefore left aside.

The analysed crimes of drug production, storage, and distribution differ significantly in both their scope and consequences. However, they share several common features. First, these are crimes in which there are usually no victims who publicly demand the restoration of social justice or the intervention of the criminal justice system. As a result, the detection of illegal drug trade is often a matter of preventive action rather than a response to direct harm. Second, in all cases, there is an illegal economic exchange involving both the seller and the buyer. Third, the level of attention paid to these offences by law enforcement institutions depends heavily on prevailing ideological and political priorities. This means that both the perception of the fight against drug addiction and the detection of such crimes are shaped by broader discourses of social control.

Literature review

Criminological literature offers numerous explanations of how particular crimes and crime patterns are related to specific characteristics of the geographical environment. For example, the presence of commercial facilities and parking lots increases the likelihood of crimes such as theft and robbery (Canter 1997; Hill 2002). Brantingham and Brantingham (1994) have shown that crack houses have a significant impact on the neighbourhoods in which they are located. Such locations contribute to higher levels of theft and burglary, as drug users seek to obtain money to purchase drugs.

Rengert and Wasilchick (1990) found that burglaries committed to raise money are often concentrated in the vicinity of drug trading locations. Burglary clusters tend to move through urban space together with these drug trading sites. Crimes committed by drug users, as well as the spatial patterns of these crimes, change when drug trading is displaced from one area of a city to another.

Rengert, Ratcliffe, and Chakravorty (2005) examined drug distribution locations in Wilmington, the largest city in the state of Delaware in the United States, and found that illegal drug trade is often situated near liquor stores, homeless shelters, and check-cashing businesses. Santiago, Galster, and Pettit (2003) studied crime concentration within a radius of 600 metres around public housing sites in Denver, Colorado. Although public housing is often perceived as potentially dangerous due to a higher concentration of low-income residents, the researchers found no significant evidence of increased crime levels in the surrounding areas. McCord and Ratcliffe (2007) analysed drug trade in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and identified drug arrests near pawnshops, pubs, check-cashing stores, and subway stations. Drug arrests were less frequent near homeless shelters and addiction rehabilitation centres. The authors explain this pattern by suggesting that drug users avoid purchasing drugs near treatment facilities because they fear losing their place in the centre or being expelled from rehabilitation programmes.

Facilities where alcohol is sold are associated with higher crime rates (Roncek and Bell 1981; Roncek and Maier 1991; Lawton 2009; McCord and Ratcliffe 2007). Numerous studies using different methods and examining various types of facilities have demonstrated a relationship between alcohol sales locations and crimes committed in their surrounding areas. Researchers have analysed a range of liquor outlets, including restaurants, bars, liquor stores, shopping centres, and stores selling various types of alcohol. What effect does the location of alcohol sales have on crime rates? Such locations can be understood as stimulating or attractive factors for criminal activity. Groff (2011) noted that a higher number of crimes occur not in the immediate vicinity of bars, but slightly farther away, within a distance of 100 to 200 metres.

For a drug distribution location to persist over a long period, it must be situated in a residential area or neighbourhood that ensures a sufficient number of drug users, or that is easily accessible to users travelling from other parts of the city (Eck 1995). This implies that drug distribution sites tend to be spatially concentrated in communities where residents are not deterred from breaking the law and are capable of distributing drugs, or in areas where there is a sufficient number of drug users with adequate financial resources. In other words, social disorganisation and poverty are not essential preconditions for the long-term existence of drug distribution sites within a particular facility. More important are the opportunities for developing illegal business, since drug trading is primarily an economic activity aimed at generating profit (McCord and Ratcliffe 2007).

In some cases, the concentration of drug users in particular locations within a city may be influenced by both land use patterns and the presence of other facilities. Many criminological studies have shown that the areas surrounding liquor stores and bars are characterised by a more dangerous criminogenic environment (Roncek and Maier 1991; Roncek and Pravatiner 1989), and that crime hotspots are often located very close to alcohol outlets (Sherman et al. 1989). Many drug users also consume alcohol, which means they often experience multiple addictions (Best et al. 2000; Wadsworth et al. 2004). As a result, drug distribution locations and nearby alcohol sales outlets can often be mutually profitable.

Studies of drug trading locations and their spatial characteristics in post-Soviet societies are limited. Drug use and drug trade are typically interpreted as phenomena of social disorganisation resulting from ideological, political, and economic transformations. The growing number of drug users has shifted attention toward harm reduction programmes, HIV and AIDS prevention, and the social integration of marginalised groups. As a result, studies focusing on the spatial aspects of crime have often been neglected. Researchers have tended to focus on broader regional geographies of drug markets in post-Soviet societies (Paoli 2002; Grogan 2006; Zabransky et al. 2010), rather than on empirical micro-level studies of city districts or specific facilities.

Within this research context, our study (Kraniauskas and Beteika 2014) examined residential areas of drug users and drug trading locations in Klaipėda, a post-Soviet port city in Lithuania, during the period from 1990 to 2010. The findings showed that between 1990 and 2000, the living spaces of drug users and drug distribution locations largely coincided. This overlap was influenced by a drug market dominated by plant-based opioids, whose preparation for consumption required considerable skill, time, space for raw material storage, and secrecy. Drugs were supplied by users themselves, and trading occurred exclusively within the group. Drug dealers were also drug users.

Around 1995, with the development of the synthetic drug market, drug trading locations began to change. Whereas drugs had previously been sold in multistore residential buildings and flats where drug users lived with their families or parents, trading locations gradually moved into public spaces. Drugs became available near markets and marketplaces. This spatial shift marked the emergence of an anonymous drug market, with production oriented toward anonymous users rather than a closed subculture. Since 2005, another trend has been observed, namely the increasing number of synthetic drug seizures in nightclubs. Although the initial boom of nightclubs in post-Soviet societies began around 1994 and was accompanied by pharmacological practices associated with rave subculture, law enforcement agencies initially paid little attention to drug trading and consumption in nightclubs. Instead, they focused primarily on combating opioid use rather than regulating leisure spaces that promoted the use of amphetamines and ecstasy. Consequently, between 1995 and 2005, the locations of drug arrests were closely linked to policy priorities within the broader war on drugs.

While our earlier study focused on identifying the spatial relationship between drug addiction and illegal drug trade, the present article aims to evaluate the relationship between drug trading locations and other types of crime, including murder, robbery, and theft.

Data sources and time periods

Information on long-term drug and moonshine distribution locations and crimes committed in their vicinity during the period from 2001 to 2010 was provided by the Klaipėda Police Headquarters in Klaipėda, Lithuania. During this period, drug substances were seized on 1,308 occasions. Although these seizures occurred at 629 different locations, only locations where drugs were seized more than three times were selected for analysis. In total, this resulted in 52 locations, including 33 locations active during the period from 2001 to 2005, 34 locations active during the period from 2006 to 2010, and 15 locations that remained active drug trading sites throughout the entire period from 2001 to 2010.

Between 2001 and 2010, a total of 54,445 crimes were recorded in the city. The following types of crime were selected for analysis: murder, grievous bodily harm, minor bodily injury, robbery, theft, hooliganism, sexual assault, and criminal damage. Since not all crimes contained geographical attributes that allowed precise location identification, 34,596 crimes were included in the final analysis. These accounted for 63.5 percent of all registered crimes.

All crime data were grouped into two five-year periods, namely 2001 to 2005 and 2006 to 2010. This division was based on the natural comparability of these periods. In selecting these time frames, additional artificial modifications of the data were avoided, such as calculating equalised indices for periods of unequal length or deriving average values. The first period was characterised by an overall increase in crime, while the second period showed crime stabilisation. Throughout the entire decade, a steady increase in drug seizures was observed, rising from 96 cases in 2001 to 186 cases in 2010.

The chosen periods allow for a clearer assessment of change and make it possible to identify continuity in social processes. This form of periodisation also serves an additional methodological purpose. Five-year crime data enrich the empirical dataset and allow for the application of analytical and visualisation techniques that require larger datasets, such as the location quotient.

Although drugs and moonshine were most often seized in individual residential apartments, the distribution locations identified in the analysis were divided into four additional subcategories: former apartment buildings associated with Soviet industries, shopping centres and marketplaces, nightclubs, and shelter houses. These locations share many similarities with urban environments found elsewhere in Europe, although some fundamental differences are shaped by the post-Soviet context. Former apartment buildings of Soviet industries represent a distinct legacy of the Soviet period. Since approximately 1994, socially marginalised groups have increasingly concentrated in these buildings following extensive industrial restructuring and privatisation. These five-storey buildings, constructed during the Soviet era, typically contain around 120 individual dwellings. They are characterised by small one-room apartments and shared facilities such as kitchens and toilets. Due to the high concentration of residents, many of these buildings have deteriorated structures and have not been renovated. From a sociological perspective, they resemble the locations described by scholars of the Chicago School as transit zones that, through urban processes, lose their original function and become areas of concentrated poverty.

When drugs were sold in apartment buildings, shelter houses, or nightclubs, the situation differed from that observed in shopping centres and marketplaces. In these locations, drug trade typically occurred in nearby parking areas and close to major pedestrian flows. Structurally, these sites resemble what criminological literature describes as open-air drug markets. No other types of open-air markets, such as abandoned buildings, former industrial areas, central tourist areas, or playgrounds and sports grounds, were identified during the study period.

Table 1. The cases of drug arrests in Klaipeda, 2001–2010.

|

Facility |

The cases of drug arrest |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n (locations) |

2001–2005 |

n (locations) |

2006–2010 |

|

|

In the city (in total) |

308 |

546 |

430 |

762 |

|

In long-term drug distribution spots |

33 |

167 |

34 |

168 |

|

- in former apartment buildings of Soviet industries |

10 |

61 |

5 |

26 |

|

- in night clubs |

1 |

8 |

4 |

51 |

|

- in surroundings of shopping centres and in marketplaces |

3 |

26 |

7 |

31 |

|

- in shelter houses |

2 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

The analysis has certain limitations, as no additional indicators of social disorganisation or poverty were included, despite their frequent use in similar studies. Official data on the local distribution of socio-demographic characteristics are not collected and are therefore unavailable. As a result, the analytical model is relatively simple, with drug and moonshine distribution locations serving as the independent variable and other types of crime as the dependent variable.

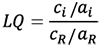

Methodology: location quotient of criminogenic locations

To evaluate differences between social environments and specific locations from a criminogenic perspective, the location quotient (LQ) was calculated for each category of location. This measure indicates how much more dangerous one area is compared with others, identifies which crimes prevail in the analysed environment, and highlights which objects, such as bars, schools, or alcohol shops, function as centres of criminogenic attraction. The location quotient is a relatively simple ratio that allows comparison of areas of different sizes based on the number of crimes committed within them. For this reason, it has been widely used in crime spatial studies for more than two decades (Brantingham and Brantingham 1995b, 2003; Santiago et al. 2003; Lawton et al. 2005; Newton et al. 2004; Groff 2011; Rengert et al. 2005; Eck et al. 2005; McCord and Ratcliffe 2007; Eismontaitė and Beconytė 2012).

The size and shape of the areas being compared depend on the research design. These areas may include administrative units such as residential districts, city quarters, census tracts, cities, regions, or hypothetically defined territories. Despite differences among the territorial units under comparison, the location quotient is calculated using the following formula:

LQ = Location quotient;

ci = total amount of crime in a study area i (where i is a sub-area of the larger region R) (for example, number of robberies registered in a particular city quarter during the selected period);

ai = the area of study area i (for example, the area of the city quarter expressed in square metres);

cR = total amount of crime in the larger region R (for example, the total number of robberies in one city registered during the selected period);

aR = the area of the larger region R (for example, the total city area expressed in square metres).

In this study, the location quotient was calculated not for city quarters or administrative districts, but for hypothetical buffer zones constructed around each long-term location of narcotics distribution and moonshine trading, using a selected radius. All defined circles and concentric rings represent Euclidean space. Together, they form the total study area within which the number of registered crimes was calculated. When a particular event fell within several overlapping circles or concentric zones, it was counted as a single event in order to avoid duplication.

Location quotients were calculated for four hypothetical zones created by circles of different sizes, with radii of 100, 200, 300, and 400 metres. The use of different radii made it possible to observe changes in crime frequency as distance from the selected point increased and to assess whether crimes occurred more frequently in the immediate or more distant environment. The study distinguished four buffer zones: first, circles with a radius of 100 metres; second, concentric rings at a distance of 100 to 200 metres from the selected points; third, concentric rings at a distance of 200 to 300 metres; and fourth, concentric rings at a distance of 300 to 400 metres. The shortest radius of 100 metres was selected because some of the longest multi-storey residential buildings in Klaipėda are approximately 100 metres in length. The longest radius of 400 metres was chosen because buffer zones in criminological research rarely exceed this distance, which is equivalent to approximately 0.25 miles. This decision is supported by studies in urban public transport, which suggest that people tend to walk distances of up to 400 metres, while longer distances are typically covered using public transport (Calthorpe 1993; Duany and Plater-Zyberk 1993; Nelessen 1994).

In many criminological studies, such an approach allows researchers to evaluate the impact of a particular location on the surrounding criminogenic situation and to determine whether the location encourages or discourages criminal activity.

The location quotient is always a non-negative value (LQ>0). If the location quotient for a particular area is greater than one, this indicates that a higher number of the analysed crimes occurred in that area compared with the city average. For example, LQ=2 means that twice as many crimes were committed in that area as in other parts of the city. A location quotient equal to one indicates that the concentration of crime in the area corresponds to the overall crime level of the city. Values below one indicate lower levels of crime than the city average, while a value of zero indicates that no crimes were registered in the analysed area.

The location quotient allows for the comparison of differences between territories, but there is no universally accepted threshold for determining when an area should be considered more dangerous than others. Some researchers consider an area to be at higher risk when the location quotient exceeds one by one tenth (Eismontaitė and Beconytė 2012). Others identify a critical value of 1.31 (Miller et al. 1991), while still others use a threshold of 2.00 (Rengert et al. 2005; Groff 2011).

Many scholars have noted that the location quotient has important methodological limitations (Groff et al. 2008; McCord and Ratcliffe 2009; Groff 2011). First, all crimes within a buffer zone are treated as equivalent events regardless of their actual distance from the reference point. For example, if the radius of the Euclidean buffer is 400 metres, a crime committed 10 metres from the reference point is treated the same as one committed 300 metres away, resulting in identical LQ values. Second, the selection of the radius for the Euclidean buffer is inherently subjective and difficult to justify theoretically. It is often unclear why a radius of 100 metres is chosen instead of, for example, 57 metres. Although distances in criminological studies are measured using various units, round numbers such as 100 or 400 metres are frequently preferred, which raises methodological questions regarding the interpretation of buffer zones. Third, multiple criminogenic objects, such as shops, shopping centres, or warehouses, may fall within the same buffer zone and influence crime levels in that area. In such cases, the impact of the selected reference point may be overstated or misinterpreted. Fourth, Euclidean distance represents the shortest possible distance between two points, but actual movement is often constrained by street networks and physical barriers such as rivers, water bodies, or restricted areas. These constraints are not captured in LQ calculations. In the case of Klaipėda, some Euclidean buffers included uninhabited areas and parts of the Curonian Lagoon that are effectively empty in terms of crime, making it difficult to control their influence on the location quotient. Fifth, in cities with extensive green spaces or water bodies, the location quotient for residential areas may be artificially inflated. To address this issue, the calculation of LQs in this study did not include the entire administrative area of Klaipėda, which covers 98 square kilometres. Instead, a reduced area of 59 square kilometres was used, excluding green and water areas that account for approximately 37.4 percent of the total city area.

Despite these limitations, the location quotient is relatively easy to interpret and makes it possible to avoid double counting crimes that fall within overlapping buffer zones. For these reasons, it remains a widely used method in criminological research.

Measuring change

To what extent does the criminogenic environment of a particular facility change over the long term? Efforts to answer this question often focus on the analysis of micro-level interventions. For example, studies examine whether improved street lighting reduces the likelihood of robbery, or whether relocating a bus stop closer to residential buildings decreases incidents of vandalism and property damage. In such research, it is essential to assess the effectiveness of specific interventions and to determine whether they reduce criminogenic risk or have no measurable impact.

However, when examining how drug or moonshine distribution locations influence the criminogenic environment over the long term, new methodological approaches focused on dynamic analysis are required. In cases where a drug distribution site persists over many years, it is often evident that interventions are either ineffective or have only a minimal impact. This situation raises two key analytical challenges. First, how can the effect of a crime-generating facility on the surrounding criminogenic environment be analysed when no interventions or preventive measures have been implemented? In other words, how can changes in criminogenic conditions be explained within a relatively stable urban and physical environment? Second, how can improvements or deteriorations in the criminogenic situation around a particular facility, such as crime rates near a long-term drug trading location, be accurately assessed when these rates depend on broader citywide crime trends? More specifically, can indicators of spatial dynamics such as the LQ, which are commonly used to evaluate variations in criminogenic risk across space, also be applied to analyse changes in the criminogenic environment over time?

The easiest way to evaluate long term changes in the criminogenic environment is to use differences in LQs calculated for different time periods. LQ(1) from an earlier period, for example 2001 to 2005, is subtracted from LQ(2) from a later period, for example 2006 to 2010. A positive value indicates a relative deterioration in the criminogenic situation, while a negative value indicates improvement. However, this simple method is not very suitable because the LQ of a particular period depends on the broader criminogenic context of the city. For example, if the crime rate around a particular facility increases together with the overall crime rate in the city or region, the LQ may remain unchanged even though the crime situation in the specific environment and its surroundings is worse than before. This raises the question of how to evaluate changes adequately without losing the relationship with reality.

One methodology is offered in economic geography, where LQ is also commonly used to analyse the competitiveness of individual regions and territorial industrial clusters (Porter 2000; Ellison and Glaeser 1997; Carroll et al. 2008; Sommers and Beyers 2010; Billings and Johnson 2012). This approach is known as cluster mapping. To identify strong and growing industrial sectors that are concentrated in a particular region, a graphical quadrant or coordinate space is constructed. This framework allows the analysed industrial sectors to be grouped into four main categories.:

• industries under transformation (contains clusters that are underrepresented in the region (low concentration);

• mature industries (contains clusters that are more concentrated in the region but are declining (negative growth);

• developed industries or ‘stars’ (contains clusters that are more concentrated in the region and are growing);

• emerging industries (contains clusters that are underrepresented in the region but are growing, often quickly).

Table 2. Opportunity buffer location quotient around the long-term drug selling locations

|

Crime |

2001–2005 |

2006–2010 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0-100 m |

100-200 m |

200-300 m |

300-400 m |

0-100 m |

100-200 m |

200-300 m |

300-400 m |

|

|

Homicide |

7,36 |

5,07 |

2,83 |

1,84 |

11,03 |

3,66 |

2,59 |

3,30 |

|

Grievous bodily harms |

9,38 |

4,41 |

2,03 |

1,64 |

13,86 |

5,92 |

3,85 |

1,23 |

|

Light bodily injuries |

9,59 |

3,87 |

2,50 |

1,91 |

11,27 |

2,94 |

2,37 |

2,15 |

|

Robberies |

7,92 |

4,36 |

3,28 |

1,92 |

8,77 |

3,90 |

2,81 |

2,65 |

|

Disorderly conduct |

7,34 |

3,75 |

1,67 |

1,51 |

9,25 |

2,83 |

2,04 |

2,05 |

|

Sexual assaults |

13,88 |

4,63 |

2,37 |

2,05 |

8,73 |

4,79 |

3,88 |

4,37 |

|

Thefts |

7,89 |

3,74 |

2,67 |

1,87 |

9,10 |

3,33 |

2,61 |

2,16 |

|

Criminal damages |

7,00 |

3,74 |

2,59 |

1,90 |

6,55 |

3,78 |

2,68 |

2,28 |

The quadrant is constructed as a coordinate space with two axes. The vertical axis represents the recent territorial concentration, measured by the LQ, of a particular industry. The horizontal axis represents the difference in LQs between the current and previous periods, calculated as LQ(2) minus LQ(1). Based on these two variables, each industrial area is positioned within the coordinate space, making it possible to clearly observe differences between individual industrial areas and to identify the cluster category to which they belong.

Table 3. Opportunity buffer location quotient for homicide, robberies and thefts around different drug-selling locations

|

Crime |

2001-2005 |

2006-2010 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

0-100 m |

100-200 m |

200-300 m |

300-400 m |

0-100 m |

100-200 m |

200-300 m |

300-400 m |

|

|

All long-term drug selling locations |

||||||||

|

All crimes |

7,91 |

3,83 |

2,68 |

1,86 |

9,04 |

3,39 |

2,60 |

2,22 |

|

Homicide |

7,36 |

5,07 |

2,83 |

1,84 |

11,03 |

3,66 |

2,59 |

3,30 |

|

Robberies |

7,92 |

4,36 |

3,28 |

1,92 |

8,77 |

3,90 |

2,81 |

2,65 |

|

Thefts |

7,89 |

3,74 |

2,67 |

1,87 |

9,10 |

3,33 |

2,61 |

2,16 |

|

Long-term drug selling locations at former apartment buildings of Soviet industries |

||||||||

|

All crimes |

8,15 |

3,35 |

2,44 |

2,26 |

4,12 |

1,45 |

1,98 |

1,41 |

|

Homicide |

15,14 |

3,58 |

2,81 |

3,91 |

18,29 |

1,15 |

3,02 |

4,58 |

|

Robberies |

10,12 |

3,71 |

2,70 |

2,92 |

6,74 |

1,63 |

2,10 |

1,59 |

|

Thefts |

7,89 |

3,36 |

2,46 |

2,21 |

3,24 |

1,43 |

1,99 |

1,40 |

|

Long-term drug selling locations at night clubs |

||||||||

|

All crimes |

4,07 |

2,09 |

1,93 |

1,55 |

9,05 |

3,25 |

3,14 |

2,56 |

|

Homicide |

0,00 |

0,00 |

0,00 |

0,00 |

0,00 |

4,35 |

5,22 |

1,86 |

|

Robberies |

2,55 |

2,55 |

1,70 |

1,33 |

9,94 |

4,89 |

3,68 |

3,73 |

|

Thefts |

3,16 |

2,18 |

1,90 |

1,55 |

7,02 |

3,24 |

3,17 |

2,57 |

|

Long-term drug selling locations around shopping centres and markets |

||||||||

|

All crimes |

21,17 |

3,47 |

3,07 |

2,66 |

21,38 |

4,67 |

3,45 |

2,91 |

|

Homicide |

0,00 |

1,67 |

2,06 |

2,24 |

7,59 |

10,95 |

4,36 |

4,16 |

|

Robberies |

11,83 |

5,15 |

4,38 |

3,09 |

12,93 |

5,20 |

3,42 |

3,66 |

|

Thefts |

19,03 |

3,08 |

2,91 |

2,49 |

19,91 |

4,06 |

3,35 |

2,74 |

|

Long-term drug selling locations at shelter houses |

||||||||

|

All crimes |

5,17 |

3,20 |

2,52 |

1,16 |

7,78 |

3,62 |

3,22 |

1,52 |

|

Homicide |

8,09 |

2,70 |

3,24 |

4,63 |

39,13 |

0,00 |

5,22 |

1,86 |

|

Robberies |

7,21 |

3,68 |

2,72 |

1,15 |

14,91 |

3,48 |

4,18 |

1,42 |

|

Thefts |

4,74 |

3,12 |

2,42 |

1,14 |

5,76 |

3,78 |

3,11 |

1,55 |

A similar methodology can also be applied to the evaluation of the criminogenic environment. Instead of industries, the analysis would focus on criminogenic facilities or on long term changes in particular types of crime. The interpretation of the data would also be similar. Some facilities could be viewed as locations with few crimes where the level of danger is decreasing over time. Others could be seen as facilities with few crimes but with danger that is increasing. A third group would include facilities with many crimes but with decreasing danger. The fourth group would consist of facilities with many crimes where danger is increasing over time. These four categories can be represented very clearly in graphical form. However, this methodology requires a small correction.

In economic studies, the construction of the cluster quadrant has certain limitations. The vertical axis always intersects the horizontal axis at zero, which indicates that the LQ values in the two periods are the same and that no substantial changes in spatial concentration have occurred over time. The horizontal axis intersects the vertical axis at the value of one, which represents an even distribution of industry within the analysed area and indicates that the concentration of a particular industrial sector does not differ from the general context. Since LQ is always a positive value, the lower part of the cluster quadrant is very limited, while the upper part is relatively large. This creates a graphical distortion, as a large number of cases tend to cluster around the intersection point. To highlight differences more clearly, it is preferable to construct the quadrant using transformed rather than absolute values. Specifically, the values on the vertical axis can be converted into z-scores. This approach places the intersection point at zero, and the visible relative differences then represent positive or negative deviations from broader trends.

In our study, this methodology was used to construct a number of quadrants. Some of them illustrate the dynamics of specific crimes occurring in the surroundings of long-term drug selling locations, as shown in Figure 1. Others demonstrate changes in the degree of danger associated with particular facilities by focusing on specific crimes such as murder, robbery, and theft, as shown in Figures 2 and 3.

![[Figure 1 illustrates changes in crime concentration within a 100 m radius of long term drug selling locations using a quadrant chart. The horizontal axis shows changes in LQ over time, while the vertical axis shows standardised crime concentration in 2006 to 2010. Crimes located in the upper right quadrant, such as homicide, grievous bodily harm, and light bodily injuries, show both high concentration and increasing intensity. Thefts and disorderly conduct cluster near the centre, indicating moderate growth and average concentration. Robberies and criminal damages appear below the horizontal axis, reflecting declining relative concentration. Sexual assaults are positioned far left, indicating decreasing concentration despite remaining spatially distinctive. Overall, the figure highlights the growing prominence of violent crime around drug selling locations.]](https://www.journals.vu.lt/sociologija-mintis-ir-veiksmas/lt/article/download/44979/version/41123/41354/129992/Paaaaa1.png)

Figure 1. Crime dynamics around long-term drug selling locations (radius – 100 m)

![[Figure 2 shows changes in the robbery environment within a 100 m radius of long term drug selling locations using a quadrant diagram. The horizontal axis represents changes in LQ for robberies, while the vertical axis shows standardised robbery concentration in 2006 to 2010. Drug selling locations near shopping centres and night clubs appear in the upper right quadrant, indicating increasing robbery concentration and above average risk. All drug selling locations combined are positioned near the centre, suggesting moderate growth and average concentration. Former industrial apartment buildings and shelter houses appear on the left side of the figure, reflecting declining robbery concentration, with shelter houses showing the lowest levels. The figure highlights clear differences in robbery dynamics across facility types.]](https://www.journals.vu.lt/sociologija-mintis-ir-veiksmas/lt/article/download/44979/version/41123/41354/129993/Pavvvvvv2.png)

Figure 2. Change in robbery environment around long-term drug selling locations (radius – 100 m)

Note: Numbers in the bubbles indicate numbers of robberies committed in 100 m radius around the facilities during 2006-2010

![[Figure 3 presents changes in the theft environment within a 100 m radius of long term drug selling locations using a quadrant chart. The horizontal axis shows changes in LQ for thefts, while the vertical axis shows standardised theft concentration in 2006 to 2010. Drug selling locations near shopping centres appear in the upper right quadrant, indicating increasing theft concentration and above average risk. Night clubs show increasing theft but with below average concentration. Former industrial apartment buildings and shelter houses are positioned in the lower left quadrant, reflecting declining theft concentration and lower relative risk. The combined category of all drug selling locations lies near the centre, indicating moderate growth and average concentration.]](https://www.journals.vu.lt/sociologija-mintis-ir-veiksmas/lt/article/download/44979/version/41123/41354/129994/Pkkkkkkis3.png)

Figure 3. Change in theft environment around long-term drug selling locations (radius – 100 m)

Note: Numbers in the bubbles indicate numbers of thefts committed in 100 m radius around the facilities during 2006-2010

Findings

The concentration of crime within a radius of 100 m around long term drug distribution locations is very high in terms of the total crime rate, as shown in Table 2. The average LQ for total crime in the period 2001 to 2005 is 8.8, while in the period 2006 to 2010 it is 9.8. This indicates that significantly more crimes are committed in this environment than in other urban areas, and that the level of threat is very high. As mentioned earlier, criminological literature states that an area is considered dangerous when the LQ is higher than 2, meaning that the probability of becoming a victim of crime or suffering damage in such a location is twice as high. In our case, this implies that eight to nine times more crimes are recorded in areas associated with drug trade than elsewhere. Drug trade locations therefore represent some of the most dangerous crime hotspots. Differences in LQs between the two periods indicate an overall deterioration of the criminogenic situation in these environments.

With respect to the relationship between crime rate and distance, the results of our study confirm the crime distance decay theory, which states that both the number of crimes and their territorial concentration decrease with increasing distance from crime hotspots. Within a radius of 200 m from a drug trade location, the probability of becoming a victim of crime is reduced by two to three times, while increasing the distance further reduces the probability several times more. This pattern of decay is clearly observed in both periods.

Although the overall concentration of crime around drug trade locations is very high, the greatest threat is associated with violent crime. Within a radius of 100 m, the probability of becoming a victim of murder or assault is much higher than the probability of becoming a victim of robbery or theft. In addition, these environments show a relatively high concentration of sex crimes, even though such offences represent a very small share of crimes in the overall pattern.

Since drug trade locations are situated in different types of facilities, such as former apartment buildings, shelter houses, and night clubs, it is important to evaluate the criminogenic environment of each facility separately. It is most appropriate to compare them using three traditional types of crime, namely homicide, robbery, and theft, which are frequently discussed in analyses of illegal drug trade and the relationship between drug use and crime.

Murder or homicide is a relatively rare crime, and only a small number of such offences are committed. In the period 2001 to 2005, there were 116 homicides in the city, of which 52.6 percent occurred within a radius of 400 m around drug trading locations. A total of 11.2 percent of all murders were registered within a radius of 100 m. In the period 2006 to 2010, there were 72 cases of murder, of which 68.1 percent occurred within a radius of 400 m and 18.1 percent within a radius of 100 m. Although the overall number of murders in the city declined, their territorial concentration near drug trading locations increased.

In the period 2001 to 2005, the most dangerous facilities were former apartment buildings associated with Soviet era industries and shelter houses. Within a radius of 100 m around these facilities, the LQ for murder was 15.1 and 8.1, respectively. At distances greater than 100 m from these facilities, the probability of becoming a victim of murder decreased by three to four times. These facilities are associated with a concentration of poverty, as former apartment buildings are inhabited primarily by low income residents, while shelter houses provide services to people without permanent housing. In the period 2006 to 2010, the criminogenic environment in these facilities deteriorated further. The concentration of murders in the immediate surroundings of shelter houses within a radius of 100 m increased fivefold. It should be noted that homeless individuals frequently became victims of murder, either as a result of conflicts with other homeless individuals or due to violence by aggressive youth gangs.

An interesting spatial pattern emerges in relation to murders around former apartment buildings and shelter houses. At distances of 100 to 200 m from these facilities, the LQ decreases sharply, indicating that crimes are primarily committed in the immediate areas where drug trade is organised. However, at greater distances, the LQ begins to increase again. This suggests a spatial structure in which drugs are sold in highly dangerous facilities that are surrounded by relatively safer zones, beyond which the probability of becoming a victim of violent murder increases.

Night clubs where drugs can be purchased are characterised by a different spatial pattern. No murders were recorded within these facilities themselves, but as distance from them increases, particularly in the period 2006 to 2010, the probability of becoming a victim of murder rises rapidly. The environment becomes more dangerous, especially within a radius of 100 to 300 m. This tendency may be explained by the fact that night club visitors, particularly those who consume alcohol or drugs, often become easy victims of robbery involving minor violence. If a victim resists or a weapon is used, robbery can escalate into murder. At the same time, a relatively safe environment inside night clubs is typically ensured by security systems and guards, whose aim is to remove violent conflicts from the club premises as quickly as possible.

A similar spatial pattern is observed in the case of shopping centres and marketplaces, where the concentration of violent crimes also increases with greater distance from the facilities.

The relationship between robberies and drug trade can be interpreted in different ways. On the one hand, it is often assumed that drug users commit robberies in order to obtain money to purchase drugs. On the other hand, individuals travelling to buy drugs often become victims of robbery themselves, as they tend to carry cash and may be physically vulnerable, which makes them easy targets.

In the period 2001 to 2005, a total of 2213 robberies were recorded. Of these, 12.1 percent occurred within a radius of 100 m from drug trade locations, and 53.3 percent within a radius of 400 m. In the period 2006 to 2010, 1889 robberies were recorded, with 14.3 percent occurring within a radius of 100 m and 62.8 percent within a radius of 400 m. As in the case of murders, there was an overall decline in the number of robberies, while their spatial concentration around drug trading locations increased.

During the period 2001 to 2010, most robberies were concentrated around shopping centres and in their immediate surroundings. This pattern is easily explained by the fact that shopping centres attract large numbers of people carrying money, making them attractive targets for robbers. As a result, the LQ remained relatively high even at greater distances from shopping centres, particularly because drugs could also be purchased in nearby areas.

More notable changes are observed in other types of facilities. In the period 2001 to 2005, many robberies occurred near apartment buildings, whereas in the period 2006 to 2010 their territorial concentration declined by approximately one and a half times. In contrast, the concentration of robberies around night clubs and shelter houses increased rapidly. The LQ of robberies near night clubs where drugs were distributed increased fourfold, while the LQ of robberies near shelter houses increased twofold.

However, a paradox emerges in the period 2006 to 2010, when the highest LQ of robberies was observed near shelter houses rather than near shopping centres. Robberies were not concentrated in places where monetary transactions and cash were most prevalent, but in areas with a higher concentration of people living in poverty. This can be explained by the fact that homeless individuals, similar to victims of murder, often become victims of violent robbery, particularly after receiving monthly social benefits. However, they rarely contact the police to seek compensation or pursue criminal justice. It is also unlikely that drug users who become victims of robbery report these crimes to the police, as this group is criminalised by the mere fact of drug use. A more convincing explanation is that shelter houses are located in areas populated by socially vulnerable groups, where local residents become victims of robbery, most often elderly people, women, or students. Although the material loss in such robberies is usually limited, the violence involved is often perceived by these groups as an offence that requires the intervention of law enforcement institutions and the restoration of criminal justice.

Theft is the most common type of crime and typically results only in financial loss. It is the predominant offence among drug users, as it provides a means to obtain money, does not require good physical condition as in the case of robbery, and does not require the use of weapons.

In the period 2001 to 2005, approximately 16.1 thousand thefts were recorded. Of these, 12.1 percent occurred within a radius of 100 m around drug distribution locations, and 47.8 percent within a radius of 400 m. In the period 2006 to 2010, the number of thefts decreased by about one third, with approximately 10.8 thousand cases recorded. Of these, 14.9 percent occurred within a radius of 100 m and 56.9 percent within a radius of 400 m.

As expected, the highest concentration of theft occurs in markets, where cash transactions take place and a wide variety of goods are available. The fact that drugs are sold near such facilities does not necessarily increase the number of thefts in these areas. Shops in general function as crime generating and crime attracting locations, where theft is more frequent due to greater opportunities. A similar situation is observed in night clubs, where visitors may misplace their belongings or become victims of pickpocketing. As a result, it is difficult to establish a direct relationship between drug trade in these facilities and theft. Rather, the overlap appears to be coincidental, as drug trading locations may coincide with areas of higher theft without any meaningful or causal connection between the two offences.

More informative patterns emerge in other drug trade locations and their relationship to theft. It is evident that theft is less common in environments characterised by poverty, as there are fewer valuable items to steal. Consequently, the concentration of theft around shelter houses and former apartment buildings is relatively low compared to trading locations and violent crimes occurring there. In these environments of poverty, the concentration of violent crimes is five to ten times higher than the concentration of theft.

A brief analysis of the spatial concentration of different types of crime indicates that drug trade locations are more closely associated with the concentration of violent crime than with theft. Violent crimes are more pronounced in environments of poverty, such as shelter houses and former apartment buildings associated with Soviet era industries, than in areas of conspicuous consumption, such as night clubs or the surroundings of shopping centres.

Conclusions

In examining patterns of drug market arrests, this study draws on established criminological frameworks, particularly social disorganisation theory and routine activities theory. The findings indicate that drug markets exert a direct influence on the criminogenic conditions of their immediate surroundings. Crime patterns in post-Soviet urban environments are increasingly converging with those observed in Western cities in the United States and Europe. One of the most important findings is the growing spatial concentration and density of violent crime in proximity to drug selling locations, especially in socially marginalised areas characterised by a high concentration of economically disadvantaged populations.

These results support the argument that more strategic measures are required to address drug markets in urban areas. The strength of variables used as proxy measures of social disorganisation highlights the close relationship between neighbourhood decline and criminal opportunities. However, a more interesting and important issue in post-Soviet societies is the relocation of drug trade and crime from socially disorganised environments to spaces of conspicuous consumption, such as night clubs and shopping centres. These two types of facilities consistently appear in the ‘star’ quadrant, indicating a growing concentration of crime in the immediate surroundings of consumption spaces.

Nevertheless, it is premature to dismiss the explanatory power of social disorganisation indicators and opportunity structures in relation to criminogenic environments on the basis of this study. It should be kept in mind that crime statistics are influenced by criminal justice priorities and crime recording practices. Shifts from socially neglected neighbourhoods towards spaces of conspicuous consumption may therefore reflect changes in institutional priorities of police and criminal discourse, in which safety concerns in middle class leisure spaces receive greater attention than issues affecting poorer populations.

References

Best, David; Rawaf, Salman; Rowley, Jenny; Floyd, Karen; Manning, Victoria; Strang, John. 2000. „Drinking and Smoking as Concurrent Predictors of Illicit Drug Use and Positive Drug Attitudes in Adolescents“, Drug and Alcohol Dependence 60 (3): 319–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00113-7

Billings, Stephen B.; Johnson, Erik B. 2012. „A Non-Parametric Test for Industrial Concentration“, Journal of Urban Economics 71 (3): 312–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2011.12.001

Brantingham, Patricia L.; Brantingham, Paul J. 1994. „Location Quotients and Crime Hot Spots in the City“ in Carolyn R. Block and Margaret Dabdoub (eds.) Proceedings of Workshop on Crime Analysis through Computer Mapping. Chicago: Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority and Loyola University: 129–149.

Brantingham, Patricia L.; Brantingham, Paul J. 1995a. „Criminality of Place: Crime Generators and Crime Attractors“, European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 3 (3): 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02242925

Brantingham, Patricia L.; Brantingham, Paul J. 1995b. „Location quotients and crime hotspots in the city“ in Carolyn R. Block, Margaret Dabdoub and Suzanne Fregly (eds.) Crime Analysis Through Computer Mapping. Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum: 129–149.

Brantingham, Patricia L.; Brantingham, Paul J. 2003. „Anticipating the Displacement of Crime Using the Principles of Environmental Criminology“ in Martha J. Smith and Derek B. Cornish (eds.) Theory for Practice in Situational Crime Prevention. Crime Prevention Studies Vol. 16. Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press: 119–148.

Calthorpe, Peter. 1993. The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community and the American Dream. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Canter, Philip R. 1997. „Geographic Information Systems and Crime Analysis in Baltimore County, Maryland“ in David Weisburd and Tom McEwen (eds.) Crime Mapping and Crime Prevention. Crime Prevention Studies Vol. 8. Monsey, NY: Willow Tree Press: 157–190.

Carroll, Michael C.; Reid, Neil; Smith, Bruce W. 2008. „Location Quotients versus Spatial Autocorrelation in Identifying Potential Cluster Regions“, The Annals of Regional Science 42 (2): 449–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-007-0163-1

Ceccato, Vânia; Oberwittler, Dietric. 2008. „Comparing Spatial Patterns of Robbery: Evidence from a Western and an Eastern European City“, Cities 25 (4): 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2008.04.002

Duany, Andres; Plater-Zyberk, Elizabeth. 1993. „The Neighborhood, the District and the Corridor“ in Petr Katz (ed.) The New Urbanism: Toward an Architecture of Community. New York: McGraw-Hill: xvii–xx.

Eck, John E. 1995. „A General Model of the Geography of Illicit Retail Marketplaces“ in Joh E. Eck and David Weisburd (eds.) Crime and Place. Crime Prevention Studies Vol. 4. Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press: 67–95.

Eck, John E.; Chainey, Spencer; Cameron, James G.; Leitner, Michael; Wilson, Ronald E. 2005. Mapping Crime: Understanding Hotspots. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

Eismontaitė, Agnė; Beconytė, Giedrė. 2012. „Spatial Distribution of Events Registered by Police in Vilnius City in 2010 and 2011“, Filosofija. Sociologija 23 (4): 215–227. https://doi.org/10.6001/fil-soc.2012.23.4.1

Ellison, Glenn; Glaeser, Edward L. 1997. „Geographic Concentration in U.S. Manufacturing Industries: A Dartboard Approach“, Journal of Political Economy 105 (5): 889–927. https://doi.org/10.1086/262098

Faris, Robert E.L.; Dunham H. Warren. 1939. Mental Disorders in Urban Areas: An Ecological Study of Schizophrenia and Psychoses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goldstein, Paul J. 1985. „The Drugs/Violence Nexus: A Tripartite Conceptual Framework“, Journal of Drug Issues 15 (4): 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204268501500406

Groff, Elizabeth R. 2011. „Exploring ‘Near’: Characterizing the Spatial Extent of Drinking Place Influence on Crime“, The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 44 (2): 156–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865811405253

Groff, Elizabeth R.; Weisburd, David; Morris, Nancy A. 2008. „Where the Action Is at Places: Examining Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Juvenile Crime at Places Using Trajectory Analysis and GIS“ in David Weisburd, Wim Bernasco and Gerne J. N. Bruinsma (eds.) Putting Crime in its Place: Units of Analysis in Spatial Crime Research. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag: 60–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09688-9_3

Grogan, Louise. 2006. „Alcoholism, Tobacco, and Drug Use in the Countries of Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union“, Substance Use & Misuse 41 (4): 567–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080500521664

Hill, Bryan. 2002. „Operationlizing GIS to Investigate Serial Robberies in Phoenix, Arizona“ in Mark R. Leipnik and Donald P. Albert (eds.) GIS in Law Enforcement: Implementation Issues and Case Studies. London: Routledge: 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203217955

Jean, Peter K. B. St. 2007. Pockets of Crime. Broken Windows, Collective Efficacy, and the Criminal Point of View. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kraniauskas, Liutauras; Beteika, Laimonas. 2014. „Kvaišalų geografija posovietiniame mieste: nelegali narkotinių medžiagų apyvarta ir narkomanija Klaipėdoje 1990-2010 m.“, Sociologija. Mintis ir veiksmas 2 (35): 271–332. https://doi.org/10.15388/SocMintVei.2014.2.8782

Lawton, Brian A. 2009. Liquor Licenses and Crime: An Analysis of Stable Crime Patterns Over Time in Houston. Paper presented at the Mapping and Analysis for Public Safety Conference.

Lawton, Brian A.; Taylor, Ralph B.; Luongo, Anthony J. 2005. „Police Officers on Drug Corners in Philadelphia, Drug Crime, and Violent Crime: Intended, Diffusion, and Displacement Impacts“, Justice Quarterly 22 (4): 427–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820500364619

McCord, Eric S.; Ratcliffe, Jerry H. 2007. „A Micro-Spatial Analysis of the Demographic and Criminogenic Environment of Drug Markets in Philadelphia“, The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 40 (1): 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1375/acri.40.1.43

McCord, Eric S.; Ratcliffe, Jerry H. 2009. „Intensity Value Analysis and the Criminogenic Effects of Land Use Features on Local Crime Patterns“, Crime Patterns and Analysis 2 (1): 17–30.

Miller, Mark M.; Gibson, Lay James; Wright, N. Gene. 1991. „Location Quotient: A Basic Tool for Economic Development Analysis“, Economic Development Review 9 (2): 65–68.

Morenoff, Jeffrey D.; Sampson, Robert J. 1997. „Violent Crime and the Spatial Dynamics of Neighborhood Transition: Chicago, 1970-1990“, Social Forces 76 (1): 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/76.1.31

Nelessen, Anton C. 1994. Visions for a New American Dream: Process, Principle and an Ordinance to Plan and Design Small Communities. Chicago: Planners.

Newton, Andrew D.; Johnson, Shane D.; Bowers, Kate J. 2004. „Crime on Bus Routes: An Evaluation of a Safer Travel Initiative“, Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 27 (3): 302–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510410553086

Pandey, Shanta; Coulton, Claudia. 1994. „Unravelling Neighbourhood Change Using Two-Wave Panel Analysis: A Case Study of Cleveland in the 1980s“, Social Work Research 18 (2): 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/18.2.83

Paoli, Letizia. 2002. „The Price of Freedom: Illegal Drug Markets and Policies in Post-Soviet Russia“, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 582 (1): 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271620258200112

Porter, Michael E. 2000. „Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy“, Economic Development Quarterly 14 (1): 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124240001400105

Rengert, George; Ratcliffe, Jerry H.; Chakravorty, Sanjoy. 2005. Policing Illegal Drug Markets: Mapping the Socio-economic Environments of Drug Dealing. Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

Rengert, George; Wasilchick, John. 1990. Space, Time, and Crime: Ethnographic Insights into Residential Burglary. Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice.

Roncek, Dennis W.; Bell, Ralph. 1981. „Bars, Blocks and Crimes“, Journal of Environmental Systems 11 (1): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.2190/R0G0-FRWY-100J-6KTB

Roncek, Dennis W.; Maier, Pamela A. 1991. „Bars, Blocks, and Crime Revisited: Linking the Theory of Routine Activities to the Empiricism of ‘Hot Spots’“, Criminology 29 (4): 725–753. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1991.tb01086.x

Roncek, Dennis W.; Pravatiner, Mitchell A. 1989. „Additional Evidence that Taverns Enhance Nearby Crime“, Sociology and Social Research 73 (4): 185–188.

Santiago, Anna M.; Galster, George C.; Pettit, Kathryn L. S. 2003. „Neighbourhood Crime and Scattered-site Public Housing“, Urban Studies 40 (11): 2147–2163. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000123222

Sherman, Lawrence W.; Gartin, Patrick R.; Buerger, Michael E. 1989. „Hot Spots of Predatory Crime: Routine Activities and the Criminology of Place“, Criminology 27 (1): 27–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1989.tb00862.x

Sommers, Paul; Beyers, William B. 2010. „Identifying Clusters in the Puget Sound Region“ in Blandine Laperche, Paul Sommers and Dmitri Uzunidis (eds.) Innovation Networks and Clusters. The Knowledge Backbone. Bruxelles, Belgium: Peter Lang Verlag: 201–224.

Wadsworth, Emma J. K.; Moss, Susanna C.; Simpson, Sharon A.; Smith, Andrew P. 2004. „Factors Associated with Recreational Drug Use“, Journal of Psychopharmacology 18 (2): 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881104042628

Wilson, William Julius. 1987. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass and Public Policy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Zabransky, Tomas; Mravcik, Viktor; Talu, Ave; Jasaitis, Ernestas. 2014. „Post-Soviet Central Asia: A Summary of the Drug Situation“, International Journal of Drug Policy 25 (6): 1186–1194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.05.004

Zorbaugh, Harvey Warren. 1929. The Golden Coats and the Slum. A Sociological Study of Chicago’s near North Side. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.