Language Policy at Universities in the Process of Internationalisation: Vilnius University Students’ Views

Roma Kriaučiūnienė

Institute

of Foreign Languages, Faculty of Philology, Vilnius

University

Universiteto str. 5 LT- 01131, Vilnius,

Lithuania

Email: roma.kriauciuniene@flf.vu.lt

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9356-1098

Research Interests: Doctor of Social Sciences (Education), Professor, Director of the Institute of Foreign Languages, Faculty of Philology, Vilnius University. Her professional interests include multilingualism and plurilingualism, foreign language didactics, future foreign language teachers’ value attitudes, personality development in the teaching/learning process at universities, social responsibility, and intercultural communication.

Rasa Šlikaitė

Vilnius University

Universiteto str. 3 LT- 01131, Vilnius,

Lithuania

Email: rasa.slikaite@cr.vu.lt

ORCID

ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5974-0984

Research Interests: Head of the Study Quality Unit, Central Administration of Vilnius University, Vilnius University. Her professional interests include study quality issues regarding the development of new study programmes, internal and external evaluation procedures, competency-based learning in medical education, and study regulation issues at the University.

Abstract. In the processes of internationalisation, universities face the need to develop their institutional language policies in order to define the use of language(s) in all areas of university life: studies, research, community and governance. However, before a university language policy can be drawn up, there are many factors that should be taken into consideration starting with the state language policy and its harmonisation with the stakeholders’ expectations and needs.

This article therefore has several objectives: to identify the necessity of an institutional language policy in the process of internationalisation at Vilnius University (VU), to give an overview of the preparatory stages for the development of the VU Language Policy, and to present findings of the research into VU students’ viewpoints on one of the aspects of language policy – teaching and learning languages at university. The methodology of the research was based on the experience of universities in the LERU Association (Kortmann 2019). The research instrument consisted of questions about subject-specific Lithuanian and English language courses, and possibilities of other language studies. The results of the students’ viewpoints revealed a rather positive evaluation of the VU Language Policy and provided some insights into its improvement.

Key words: internationalisation, university, language policy, teaching and learning languages, students’ viewpoints

Copyright © 2022 Roma Kriaučiūnienė, Rasa Šlikaitė. Published

by Vilnius University Press.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are

credited.

Pateikta / Submitted on 01.01.21

Introduction

The emergence of alliances among European universities is the most recent trend in internationalisation that makes language policies at the institutional and alliance levels indispensable. As stated in the EPICUR European Model Language Policy (2021, p. 3), language policies have an essential role to play in consolidating European linguistic diversity and safeguarding accessibility to higher education for young, talented Europeans. A robust language policy that outlines the policies regarding languages of instruction, language use in governance, and guidelines for language proficiency is an essential prerequisite to achieving these goals. The EPICUR model language policy is a good model framework to use to formulate language policies at European higher education institutions and European university alliances. As such, this model language policy invites institutions and European university alliances to think about language use in the context of their own needs, wishes and vision for the future of the university. The final decisions in terms of language policy need to be made by the university leaders themselves as they know what suits their university best (EPICUR, 2021, p.6).

Preserving its traditions, Vilnius University both maintains its impact on Lithuanian society and seeks to enhance its international acknowledgment by being recognised in the world and actively participating in European life. This idea is expressed in Vilnius University’s Statute (https://www.vu.lt/site_files/Adm/statutas/Vilniaus_universiteto_Statutas.pdf), ‘which, inter alia, enshrines the University’s mission as the responsibility to the Nation and the State of Lithuania, openness and accountability to society, and the aspiration to educate active and responsible citizens of the State of Lithuania and leaders of society so that the quality of studies in all their forms would meet the needs of the students, the society and the State, and would comply with the highest international standards’ (p. 5).

Thus, Vilnius University remains committed to disseminating knowledge in the official language of Lithuanian to the Lithuanian citizens and ensuring the sustainable development of the academic Lithuanian discourse. It also seeks to enlarge its participation in the European Higher Education Area and increase its international recognition on a wider scale. The latter could be attained through the communication of its research achievements in English and other languages. It has been considered that the right balance should be maintained between the national language and English as a lingua franca as well as other languages in all areas of university operations. Depending on the aims of communication, Lithuanian is used for the purposes of communication inside Lithuania, and English and/or other languages are used for external communication. However, taking into consideration a rather slow but steady increase of international students and academic staff at Vilnius University, communication in the areas of studies and services at VU are becoming increasingly more multilingual. Evidently, the process of internationalisation and membership in the Arqus European University Alliance have established the need for the development of an institutional language policy at VU. It is expected that it will define when we agree to use other languages alongside our main first Lithuanian language to create a more welcoming multilingual, intercultural and inclusive environment at VU.

As stated in the EPICUR European Model Language Policy (2021) and in the briefing paper on the language policies at the LERU Member Institutions (Kortmann, 2019), university leadership should carry strategic responsibility for all aspects of the language policy and for the key decisions made to steer, guide and support its successful implementation. However, the procees of developing the institutional Language Policy at VU revealed that there seemed to be a lack of agreement as well as commitment among the stakeholder groups. There were several attempts to develop an institutional VU Language Policy. The first attempt was in 2013, but it was not approved by the VU Senate. The second attempt started in 2019 and the process of preparing and implementing the VU Language Policy was still ongoing when the current article was being written. The experience of developing the institutional Language Policy at VU made it evident that its need should be elucidated more explicitly to the stakeholder groups so that their divergent viewpoints could be fully discussed and possibly harmonised in order to reach an agreement. The current paper therefore has several objectives. Firstly, it makes an attempt to specify the need for an institutional language policy in the process of internationalisation at Vilnius University; secondly, it describes the preparatory stages of the development of the VU Language Policy and its structure. Finally, it aims at identifying one of the stakeholder groups: VU students’ viewpoints on one of the important aspects of the language policy – teaching and learning languages at Vilnius university.

1. Literature Review

1.1. Language Policy and its Needs at Higher Education Institutions

Language policy is considered a complicated concept. According to Schiffman (1996, p. 276), language policy is determined by the historical and cultural factors of the country and is viewed as the following:

‘a cultural construct that rests primarily on other conceptual elements – belief systems, attitudes, myths – the whole complex that we are referring to as linguistic culture, which is the sum totality of ideas, values, beliefs, attitudes, prejudices, religious strictures, and all the other cultural ‘baggage’ that speakers bring to their dealings with language from their background.’

This definition highlights the importance of a country’s historical heritage, which influences the country’s views of how they shape their language policy. In the opinion of the Lithuanian scholars Kėvalienė and Raipa (2007, p. 47), language policy is an ambiguous concept, which in the first place is:

‘what the government does formally – by legislating, enforcing court decisions, creating various authorities, in other words, determining what must be the public use of the language(s), developing the language skills necessary to meet the priorities of the state by setting the rights and educational opportunities of individuals or groups of individuals to use and nurture their language(s). Language policy is the decisions (rules, instructions, recommendations, directives, guidelines) made by the state on the status, use, areas of use and users of the language(s)’ (translated by the author).

Evidently, language policy has a judicious force and this shows how language policy-making is carried out at the state level and defines language usage in state institutions, educational ones as well. Language policy determines three important issues: the use of the language within a state, the right and opportunity for its citizens to use the language, and the obligation to preserve and nurture the language. Clearly, the way the language policies are implemented depends on a specific country’s decision on how they want to maintain the use of their languages, for example, by issuing laws and establishing various institutions and authorities to protect their language(s).

The Center for Applied Linguistics (https://www.cal.org/areas-of-impact/language-planning-policy) provides an explanation of language policy with the incorporation of language planning and highlights the importance of decisions of language policy and planning that influence the rights of language use and maintenance.

The Universal Lithuanian encyclopedia (Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija) (https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/kalbu-politika/) defines language policy as a set of measures to implement the pre-determined language provisions of the society. Language policy is said to be determined and implemented by state institutions and is carried out in three areas: language status regulation, language corpus (language system and usage) planning, and language teaching.

In Lithuania the Law on the State Language of the Republic of Lithuania (https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.15211?jfwid=rivwzvpvg) defines the status of the Lithuanian language as a state language and, among other things, defines the right guaranteed by the state to the residents of the Republic of Lithuania to obtain higher education in the state language. The Law on Science and Studies of the Republic of Lithuania (https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.343430), states, inter alia, that the language of instruction in state higher education institutions is Lithuanian, but that it is also possible to teach in other languages when: the intended study results are related to the knowledge of a foreign language; lecturers or other academic activities are led by foreign lecturers; international students study at a higher education institution according to a certain study programme; or studies are carried out in accordance with joint study programmes with foreign higher education institutions.

The European Union's language policy is based on respect for linguistic diversity in all member states and the development of intercultural dialogue throughout the Union. To make mutual understanding truly possible, the EU promotes the teaching and learning of foreign languages and the mobility of every citizen through specific education and training programmes. Knowledge of a foreign language is considered one of the key skills that all citizens of the European Union need to acquire in order to have more opportunities for learning and employment. In 2017 at the Gothenburg Social Summit, the European Commission set out the idea of a European Education Area becoming ‘the norm to speak two languages in addition to the mother tongue’ (COM (2017) 0673).

The role of language is important in the processes of internationalisation in the Area of Higher Education in Europe. This raises the need for universities to define their institutional language policies in order to suit the needs of the incoming linguistically diverse academic staff and international students and to create more favorable educational environments for all. It is clear that the institutional language policy should be in harmony with the state language policy. Therefore, the reasons for institutional language policies at universities as highlighted by scholars (Kaša and Mhamed 2013; Kuteeva 2014; Mortensen 2014; Kibbermann 2017) are academic mobility, demographic decline, and thus increased internationalisation. The mobility of students and staff requires a common language of communication for both hosts and visitors, which in most cases is English as a lingua franca. As Kibbermann (2017) observes, internationalisation is closely related to the increasing use of English in academic settings where it has never before been used so extensively.

A similar view is expressed by Mortensen (2014), who states that English is commonly seen as the ‘natural’ choice for university internationalisation, and English is accordingly promoted as the ‘obvious’ language of instruction for international education in many university policies. As a result of internationalisation, many universities have adopted English-medium instruction (EMI) programmes. And the declining demographic situation in many countries has made many universities look for ways to attract international students (Kuteeva 2014). Given the fact that English has recently held the dominant role as the language of academia, universities in many countries have been under pressure to open study programmes in English. As Kaša and Mhamed (2013) claim, the way out for the universities of non-Anglo-Saxon countries is also to offer more study programmes in the English language in order to keep up in the competition with universities in the English-speaking countries.

The international dominance of the English language has been a much-discussed issue among scholars. Many researchers have analysed the consequences of an extensive introduction of EMI programmes in various countries and have taken a variety of perspectives. The latest research carried out by Orduna-Nocito and Sánchez-Garcia (2022) revealed that with the introduction of EMI there has been a misalignment between the institutional language policies of universities and teachers’ views on their teaching and learning. The authors argue that although many universities are drafting policies to guide their academic staff in this process, what has to be examined is whether teachers’ views and experiences are aligned with what these policies determine and if they are complementary or far removed from each other.

Similar issues have been raised by Airey, Lauridsen, Räsänen, Salö and Schwach (2017) in their study on the consequences of the extensive use of EMI programmes in the universities of the Nordic countries. The authors (pp. 563–564) revealed that Danish universities introduced EMI programmes very quickly and attracted a growing number of international students. They claimed that lecturers and students were able to switch to English in higher education teaching and learning without any problems; however, they also highlighted that in addition to learning other languages Danes also needed to strengthen their English. In Finnish universities, the quality of teaching and advising, demonstration of skills in the language of instruction, and promotion of national languages and culture are highlighted. The institutional language policy in Finnish universities usually provides that both Finnish/Swedish and English academic communication is to be supported systematically in order to empower the communication of disciplinary expertise to various audiences. The authors (Airey, Lauridsen, Räsänen, Salö and Schwach 2017, pp. 569–570) draw attention to the fact that university language policies should encourage the faculty discussion that disciplinary literacy goals be specified for each course in compliance with the language-learning outcomes. This includes detailing how these goals relate to the overarching disciplinary literacy goals of the curriculum and how these skills will be taught and assessed.

Another important issue that was raised by Airey, Lauridsen, Räsänen, Salö and Schwach (2017, p. 568) is the Nordic universities’ concern about the loss of the domain of their national languages with the increase of the EMI courses. In defence of their national languages, the Nordic countries authorised the Nordic language policy that recommended the adoption of parallel language use, which was explained as follows: ‘the concurrent use of several languages within one or more areas. None of the languages abolishes or replaces the other; they are used in parallel’ (Nordic Council of Ministers 2007, p. 93, as cited in Airey, Lauridsen, Räsänen, Salö and Schwach 2017, p. 568). This was a pragmatic solution that was constructed in order to deal with the rapid expansion of English in Nordic higher education with the aim of protecting their state languages.

A slightly different situation in the Baltic countries has been observed by the study carried out by Kaša and Mhamed (2013, p. 33-47) and Bulajeva, Hogan-Brun (2014). In the Baltic context, policy decisions regarding the use of language have been framed by the thorny historical legacies of Soviet occupation. Although English is the most commonly used foreign language in higher education in the Baltic countries, contemporary language policy is impacted by prior historical context and is aimed at sustaining and developing the use of national languages in higher education. Their research demonstrated that institutions of higher education in the Baltic countries attempt to keep the balance between the promotion and strengthening of their native languages on the one hand and making an attempt to become more open to international students on the other, thus offering more study programmes in English and other languages. The predominance of the English language, however, might be viewed as a threat to native languages. The authors conclude that in the Baltic countries, the official policies toward the use of language in higher education at the beginning of the twenty-first century were guided by assertions of strengthening national official languages while advancing the international profile by using instruction in English.

It should be pointed out that language policy in the context of internationalisation does embrace a wider use of languages and does not limit itself to the number of EMI programmes or the description of the use of languages in the area of teaching and learning. Language use is diverse and it is of great importance in other areas of university life as well, such as communicating with the academic community and disseminating research to local as well as international communities. According to Saarinen and Taalas (2017), language policy reflects our approach to understanding the functions of language in society as well as in the research field. Moreover, as Kibbermann (2017) claims, science and research in higher education are international by nature. Depending on the target audience to be achieved, the transfer of research is to be carried out not only in English but in other languages as well. While drafting institutional language policies, universities must therefore pay attention to the use of languages in all areas of university life.

Since drafting and authorising institutional language policies is a part of universities’ internationalisation policies, the universities themselves must devote significant resources to this endeavor (Block 2016). Furthermore, in order to draw up a university language policy, there are many factors that should be taken into consideration starting with the state language policy and harmonising it with the stakeholders’ discourses, needs, and interactions. The following sections of the article will describe the reasons for developing an institutional language policy at Vilnius University, the process of its preparation, and its structure, and will reveal the research findings of one of the stakeholders’ groups – students’ views on the current state of the language policy at VU.

1.2. The Reasons for the Development of the VU Language Policy Guidelines

As stated by Kortmann (2019, pp. 3–4), two central questions should be answered before deciding on an institutional language policy: why should the higher education institutions (HEIs) want a language policy in the first place (e.g. as an important strategic instrument in the institutional internationalisation policy or as a measure for quality assurance and enhancement)? What are the HEIs overall goals and strategies? These were also the questions that were addressed at the beginning of the development process of the VU Language Policy Guidelines.

It could be stated that the development of Vilnius University’s Language Policy Guidelines alongside its Implementation Plan was determined by several factors that are inherently connected with the processes of internationalisation. The Guidelines for Internationalisation of Teaching and Learning at Vilnius University (https://www.vu.lt/apiemus/dokumentai#kiti-dokumentai) were developed and authorised by the VU Senate with its main goal to integrate an international dimension into studies at the University in order to contribute to the achievement of strategic directions specified in the University’s Strategic Plan (https://www.vu.lt/site_files/VILNIAUS_UNIVERSITETO_STRATEGINIS_PLANAS_20212025.pdf). The language policy document was therefore seen as a necessary strategic instrument that would complement the process of internationalisation.

The fact that Vilnius University has been a member of the Arqus European University Alliance has also contributed to the need of drafting an institutional language policy. Moreover, the Alliance has been working on the development of the Arqus Language Policy Charter, which has accordingly inspired member universities to rethink and reshape their institutional language policies.

Although VU has a document defining the teaching and learning of languages – The Concept of Foreign Language Teaching of VU (https://www.vu.lt/site_files/Reguliaminas/U%C5%BEsienio_kalb%C5%B3_mokymosi_koncepcija.pdf) – authorised by the VU Senate in 2012, this covers only the area of foreign language teaching. It needed to be renewed in line with the challenges for internationalisation that VU faces today.

The other questions as outlined in LERU (Kortmann 2019) had to be addressed as well. Firstly, it was important to look at the role English and other foreign languages play in the classroom and in academic discourse as compared to the national Lithuanian language, the use of which is determined by Lithuanian laws. Clearly, appropriate linguistic skills are necessary for academic discourse in the national language as well as in other languages as these are key to academic education and scholarly publications at higher education institutions. Consequently, another important issue was to define the necessary level of foreign language(s) for students and the academic staff relevant to the academic discipline, and to (academic) English. Next, the quality assurance and enhancement of teaching of foreign languages and the use of English as the medium of instruction for entire degree programmes also had to be considered. This involved the preparedness of the academic staff for the delivery of EMI courses. The other issue of importance was the preparedness of the non-academic staff (e.g. librarians and administrators) to communicate with international students and scholars and provide support. Finally, the support provided to international researchers and their families, as well as to international students concerning the acquisition of Lithuanian also had to be addressed.

1.3. The Process of the Development of the VU Language Policy Guidelines and its Structure

The process of developing the VU Language Policy Guidelines involved an establishment of an initial working group, which was later extended to a larger group to integrate representatives of all the faculties of Vilnius University, the Central Administration, and Students Representation in order to make the preparation process participatory and transparent. Firstly, a thorough analysis of language policies at several European universities (Austrian, Belgian, Check, German, Polish, Scandinavian, and Baltic), including the universities of LERU (Kortmann 2019), as well as several US universities was carried out by the initial working group before the discussions with the larger extended working group started. This analysis revealed the reasons why universities have their institutional language policies. Evidently, universities seek to have a balance between internationalisation and the use of English as a language of communication on the one hand, and their state national languages on the other, thus defining the extent to which these languages are to be used in the areas of studies, research, governance and university community life.

The analysis of information about institutional language policies at the above-listed universities served as a basis for further steps of the extended working group to be taken. The working group was divided into three subgroups to discuss language policy issues in multiple areas of university life: studies, research, community and governance. The discussions within the subgroups took place in a bottom-up manner in order to identify the needs for the language policy at VU.

The first subgroup responsible for studies analysed the internationalisation process of the study programmes, the need for more EMI courses, the teachers’ preparedness for EMI courses as well as the necessary support to be provided to them, and students’ responses to the quality issues of EMI courses. Concern has been expressed that the quality of the Lithuanian language courses for academic purposes needs to be raised and that the courses for Lithuanian as a foreign language need to be also offered to international students more extensively. In addition, ESP courses needed to be provided to students in all BA-cycle study programmes at VU, and opportunities to study other languages also need to be made available.

The emergent issues discussed within the second subgroup in charge of research revolved mainly around the languages of scholarly publications, dissemination of research in Lithuania and abroad, the creation and sustainability of academic discourse in the Lithuanian language with a strong focus on the development of terminology in many areas of research, and the publication of textbooks and teaching materials in the Lithuanian language. The group highlighted the need to publish research in English and/or other languages in order to raise the visibility of the Lithuanian researchers and to obtain more international acknowledgement of their research.

The third group discussed issues pertaining to multilingualism and the use of other languages than the state language within the university community in the context of internationalisation, highlighting the need for support for the improvement of linguistic-communicative competence and the possibility of English and other language courses for academic and non-academic staff in order to meet the needs of the multilingual and multicultural environment at the university.

The VU Language Policy Guidelines were drafted on the basis of the insights gained from the discussions within the subgroups of the extended working group. Reference was made to the following documents: VU Statute[1], VU vision, mission, and values[2], VU Strategic Plan of 2021–2025[3], VU Guidelines of Internationalisation[4], the Law of the State Language of the Republic of Lithuania5, and the Law of Research and Studies of the Republic of Lithuania6. The institutional Language Policy document of VU was meant to have two major parts: the Language Policy Guidelines and the Implementation Plan. The Guidelines consisted of six parts: 1. The Preamble, 2. The Aims of the Language Policy, 3. The Use of Languages at University with the following subsections: the Lithuanian Language Use, English Language Use and the Use of Other Languages, 4. Studies, 5. Research, 6. University Communication, Administration and Community.

In order to maintain the participatory and transparent nature of the development of the document, the blueprint for the VU Language Policy Guidelines was introduced to the academic community, the governing bodies and the Vilnius University Senate. Although numerous rigorous cycles of presentation and discussion as well as feedback and correction lasted for two years, the document has not yet been approved. There was a necessity to provide a plan for the implementation of the Language Policy Guidelines to show the necessary steps to be taken in order to show how the policy will work in practice. As it has been discussed before, another important aspect that emerged in the preparatory process was that the main opinions held by the stakeholder groups diverged. A more detailed analysis of the main stakeholder groups’ attitudes to language policy issues at VU was therefore initiated. The following section presents the students’ viewpoints on the language policy and the development of multilingualism at VU, mostly focusing on the teaching and learning process of a range of various languages.

2. Methodologyand data

The research into students’ viewpoints on how to improve language policy and the development of multilingualism at Vilnius University was carried out at Vilnius University in March–April 2022. The methodology of the research was based on the experience of the LERU universities (Kortmann 2019). The aim of the research was to identify students’ viewpoints on the studies of the subject-specific Lithuanian language, the subject-specific English language studies and the possibilities of conducting studies of other languages. The instrument used for the research was a questionnaire consisting of 19 questions. It was compiled in reference to the main parts of the VU Language Policy Guidelines in terms of the languages used in the study process. Questions 1–5 were devoted to determining which faculties and what year students participated in the survey, what their study programme was and what languages their study programme was delivered in. Questions 6–9 aimed to determine the students’ viewpoints on the subject-specific Lithuanian language courses (modules) within their study programmes. Questions 10–13 were meant to identify what languages students read academic literature in that is necessary for their studies, as well as students’ opinions of the subject-specific English language courses offered within their study programmes. The last part of the questionnaire (questions 14–19) were dedicated to specifying the respondents’ views on the possibilities of second foreign language studies at VU, the languages that students would like to study, students’ preparedness to pay for the language courses as well as the students’ suggestions for improvement of the foreign language teaching process at VU. The questionnaire contained mainly closed questions, with several open questions encouraging students to provide comments on the improvement of language teaching at VU. The frequencies of students’ answers to closed questions were calculated, and content analysis of the answers to open questions was performed by identifying categories and subcategories of the repetitive answers.

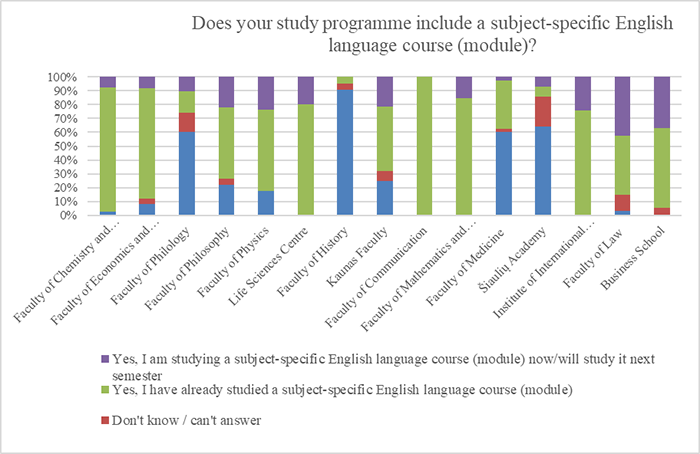

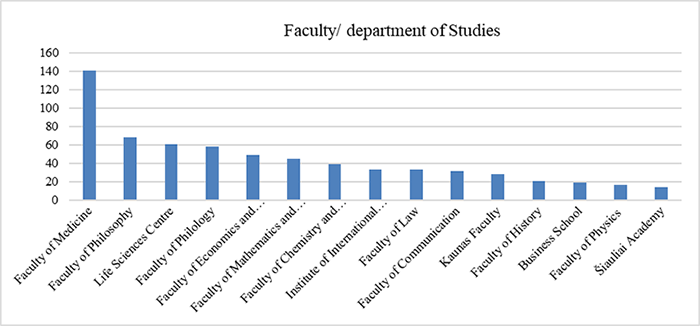

In total, 659 undergraduate students completed the survey. Figure 1 below presents the faculties at Vilnius University and the research participants represented in the survey.

Figure 1: Faculties at Vilnius University the research participants represented.

Evidently, the largest number of students who participated in the research study were from one of the largest faculties at VU, the Faculty of Medicine (N=141), then a similar number of students were from the Faculty of Philosophy, the Life Sciences Centre and the Faculty of Philology (N=68, N=61, N=58, respectively), followed by participants from the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, the Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics and the Faculty of Chemistry and Geosciences (N=49, N=45, N= 39 respectively). A nearly equally lower number of students were studying at the Institute of International Relations and Political Sciences, the Faculty of Law, the Faculty of Communication, and Kaunas Faculty (N=33, N=33, N= 32, N=28 respectively). The lowest number of participants were from the Faculty of History, the Business School, the Faculty of Physics and Šiauliai Academy (N=21, N=19, N=17, N=14 respectively).

The research participants represented a total of 93 study programmes from the above-listed faculties at Vilnius University. Most of the students were in first-cycle study programmes (506 BA study programmes), with 148 in integrated study programmes, and very few being from professional (pedagogical) study programmes at VU.

Table 1: The VU study programmes represented by the research participants

The type of the study programme |

|

BA |

506 |

Integrated studies |

148 |

Professional (pedagogical) studies |

4 |

Table 2 provides information on the students’ current year of studies.

Table 2: The year of studies

The year of studies |

|

Year 2 |

201 |

Year 1 |

194 |

Year 3 |

137 |

Year 4 |

99 |

Year 5 |

21 |

Year 6 |

6 |

The most active in answering the survey questions were the second-year students (N=201), the first-year students (N=194) and the third-year students (N=137), followed by a slightly lower number of fourth-year students (N=99) with fifth-year and sixth-year students representing the lowest number in the research study ((N=21 and N=6 respectively).

Table 3 provides information on the languages that the study programmes are delivered in as indicated by the research participants.

Table 3: The languages the study programmes are delivered in at VU

The languages of the study programmes |

|

Lithuanian |

562 |

English |

74 |

Other |

22 |

Evidently, most of the students who participated in the research study indicated that the study programmes they represented were delivered in the Lithuanian language. The participants indicated that the other languages (depending on the type of study programme with most of them being philological ones) included Chinese, Danish, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Russian, Spanish, Swedish and Turkish.

3. Research results

3.1 Students’ viewpoints on the subject-specific Lithuanian language studies at Vilnius University

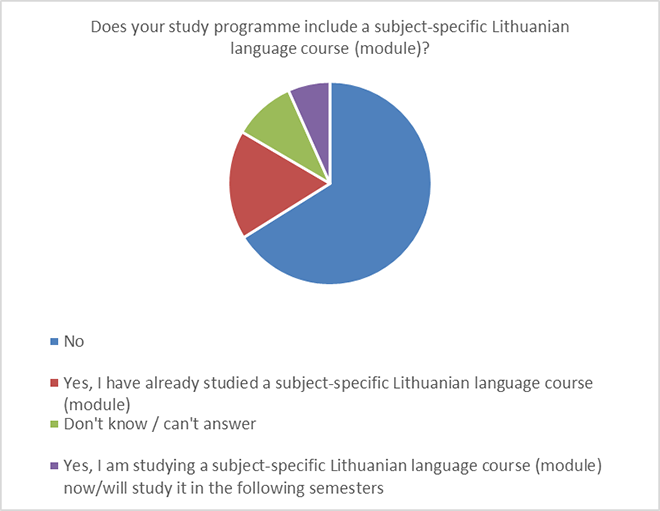

One of the research objectives was to determine students’ viewpoints on the studies of the subject-specific Lithuanian language. Figure 2 provides information on how many of the students had already studied such a subject within the framework of their study programmes or were still studying this.

Figure-2: The percentage of the respondents who had taken a subject-specific Lithuanian language course (module) in their study programme

It seems clear that only one-third of the respondents were able to express their opinion on a subject-specific Lithuanian language course in their study programmes or modules as they had either taken it or were taking it at the time the research study was being carried out. This could be explained by the fact that not all the study programmes at VU include such a course or module in their study programmes.

The following question was included in order to determine if students were satisfied with the quality of their subject-specific Lithuanian language course (module) (in terms of progress, content and teaching/implementation). This question was answered only by one-third of the respondents as well. Their answers to this question are provided in Table 4.

Table 4: The respondents’ satisfaction with the quality of their subject-specific Lithuanian language course (module) (in terms of student progress, content and teaching/implementation)

Are you satisfied with the quality of your subject-specific Lithuanian language course (module) (in terms of your progress, the content and teaching/implementation)? |

|

Rather yes |

52 |

Yes |

37 |

Mostly no |

15 |

No |

16 |

Don't know/difficult to say |

12 |

It should be again pointed out that the data presented in Table 4 refer only to those students (N=132) who had a subject-specific course in their study programmes. It is evident that a fairly positive evaluation prevails as 89 students answered yes or rather yes, around 30 students expressed their negative opinion, and the minority (12 students) did not have an opinion about their subject-specific Lithuanian language course.

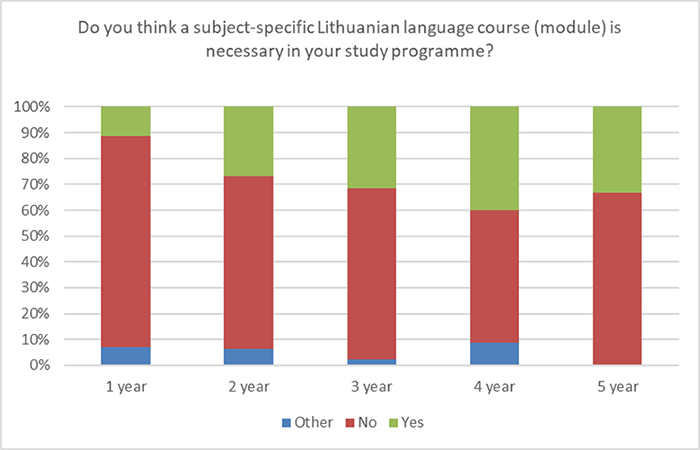

The other question that the students had to answer in the survey was about the necessity of a subject-specific language course in their study programmes. Figure 3 below provides the respondents’ views.

Figure-3: Students’ viewpoints on the necessity of a subject-specific Lithuanian language course (module) in their study programmes.

Clearly, the fourth-year students are the group who view a subject-specific Lithuanian course to be most necessary. Generally, the trend to evaluate such a course within their study programmes as important seems to increase through the years of studies. Presumably, when students write their BA papers, they come to understand that they lack subject-specific terminology in the Lithuanian language.

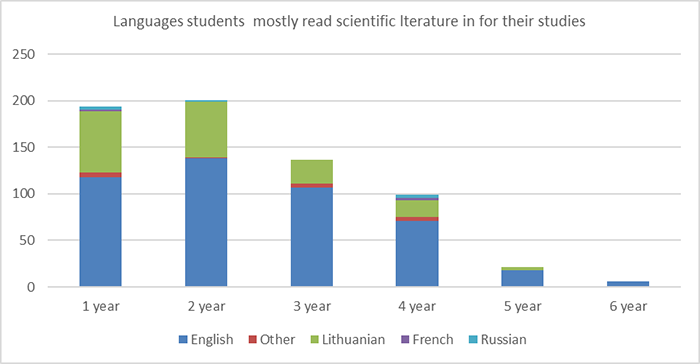

Another important issue of the research study was to establish in what languages students generally read the academic literature for their studies. Figure 4 shows the distribution of languages as identified by the students who participated in the research study.

Figure 4: Languages students mostly read academic literature in for their studies

As is seen from the data provided in Figure 4, students mostly read academic literature necessary for their future professional areas in the English language. Evidently, English remains the prevailing language throughout all the years of their studies. It can be assumed that the most recent literature is mainly found in the English language; therefore, students read more in English than in Lithuanian.

3.2 Students’ viewpoints on the subject-specific English language studies at Vilnius University

The other important aspect of the survey was to determine the respondents’ views on a subject-specific English language course at Vilnius University. As our Language Policy Guidelines have not yet been approved, the foreign language teaching is based on the official document the Concept of Foreign Language Teaching and Learning at Vilnius University, which was approved by the Vilnius University Senate in 2012. According to this document, the first foreign language should be included in BA study programmes as a compulsory subject.

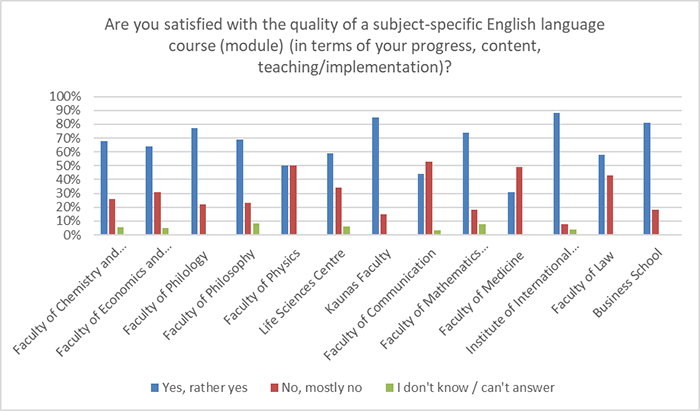

Figure 5 demonstrates the inclusion of a subject-specific English language course in a study programme per faculties at VU.

Figure 5: Inclusion of a subject-specific English language course (module) in the study programmes offered by the faculties at VU.

It is evident from the data provided in Figure 5 that a subject-specific English course is not included in all study programmes. At the Faculty of Philology, mainly languages are studied as a major subject and then there is an option to study other languages as a minor subject. In addition, there are study programmes that offer studies in the philology of two languages at once, for instance, English and another foreign language (Spanish, French, Norwegian, German or Russian). However, it should be pointed out that some BA study programmes at faculties other than the Faculty of Philology have excluded a subject-specific English course from their study programmes by either replacing it with courses in other languages (e.g. at the Faculty of History, German, Russian and Polish are taught instead to meet the specific needs of the subject of history) or by eliminating it completely (e.g. at the Faculty of Medicine in the study programme of medicine and the study programme of odontology). More research should be conducted on the study programmes offered by Šiauliai Academy (the former University of Šiauliai) as it has only recently been joined with Vilnius University.

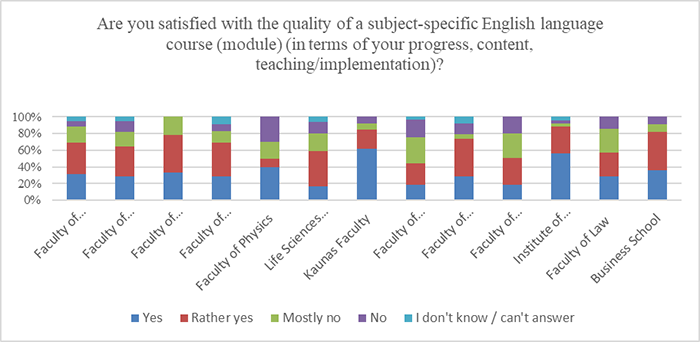

Figures 6a and 6b demonstrate the level of satisfaction of VU students with their subject-specific English language course (module) (in terms of students’ progress, the content and teaching/implementation) within their study programmes in the faculties.

Figure 6a: Satisfaction with the quality of a subject-specific English language course (module) (in terms of student progress, content and teaching /implementation) of VU students

Figure 6b: Satisfaction with the quality of their subject-specific English language course (module) (in terms of student progress, content and teaching/implementation) of VU students

As is evident from the figures presented above, generally the research participants expressed a more positive than negative view of the quality of their subject-specific English language course (module) (in terms of progress, content and teaching /implementation). In Figure 6b, the respondents’ positive answers yes and rather yes were calculated together, whereas negative responses incorporated all answers under the headings no and mostly no. It should be pointed out that since the academic year 2019/20 all of the ESP courses at VU have been remodified to follow task-based and action-oriented approaches, which might have generated more positive students’ attitudes towards subject-specific English language courses (see Kriaučiūnienė, Targamadzė, Arcimavičienė, 2020).

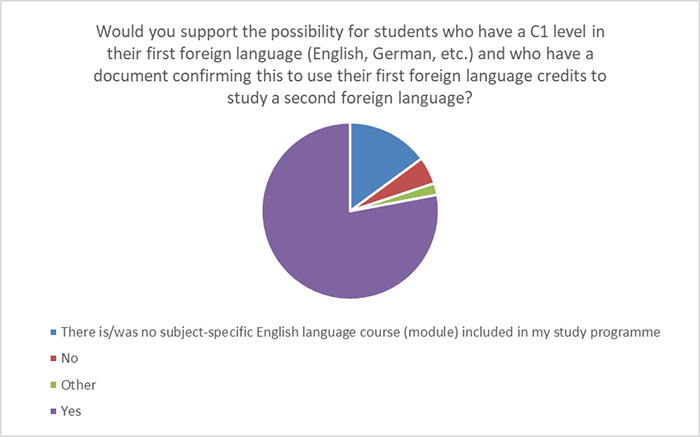

We were also interested to determine if students wanted to study a second foreign language instead of their first foreign language (in most cases English) if the level of that language was at C1.

Figure 7: Students’ opinion on the option to use their first foreign language credits to study a second foreign language

Evidently, the majority of students would like to use the opportunity to exchange their first foreign language credits for the studies of a second foreign language.

3.1 Students’ viewpoints on the possibilities of other language studies at Vilnius University

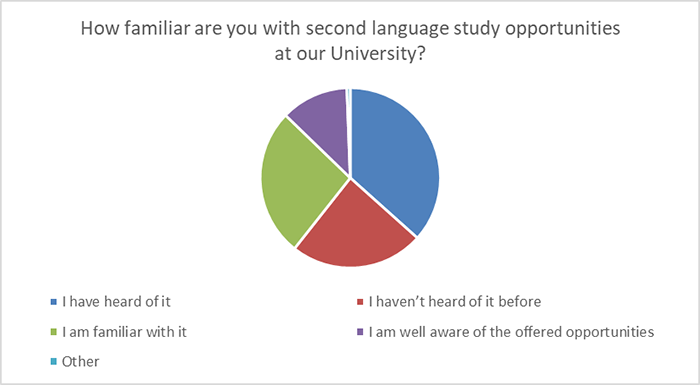

The final part of the survey was meant to identify students’ views on the possibilities of second language studies at Vilnius University. Figure 8 below demonstrates students’ awareness of the opportunities at Vilnius University to study other languages.

It can be seen from the pie chart above that there is a generally positive trend in students’ awareness of the possibilities of second language studies at VU. One-fifth of the respondents are well aware of the opportunities offered, well over one-quarter acknowledge that they have heard of the opportunities, and just over one-quarter say that they are familiar with all of the possibilities, whereas the students who have not heard of these before make up only one-quarter of the total answers. An evaluation of this data suggests that students are informed about the possibilities to learn a second foreign language at VU.

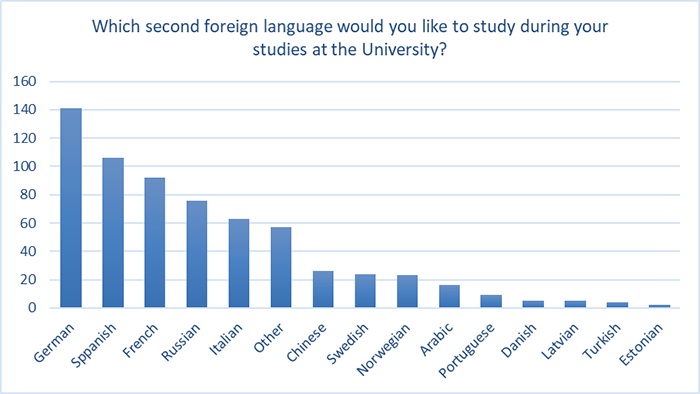

It was also interesting to identify the languages (other than English) that students wanted to master during their studies at VU. Figure 9 presents the data on VU students’ language preferences.

Figure 9: Students’ preferences of languages that they would like to study at VU

Evidently, German stands out as one of the most favourable choices among the second languages offered followed by Spanish and French respectively. The respondents also expressed interest in Russian and Italian, and nearly an equal number left their language choices unidentified. Further down the row were Chinese, Swedish and Norwegian, which seemed quite attractive choices for nearly the same number of students with the Arabic language being the last in this sequence. The lowest level of interest was expressed in studying Portuguese, Danish, Latvian, Turkish and Estonian.

The students commented that the choice of second languages is limited, and again repeated the same information about the lack of real possibility to enroll in these courses. Students regretted that the possibility of really attending the courses is limited, that the language modules have been removed from their study programmes, and that only the possibility to learn the languages in an extra-curriculum programme remained. The main problems are the decrease in the choice of languages, and the limited number of places on extra-curricular language courses.

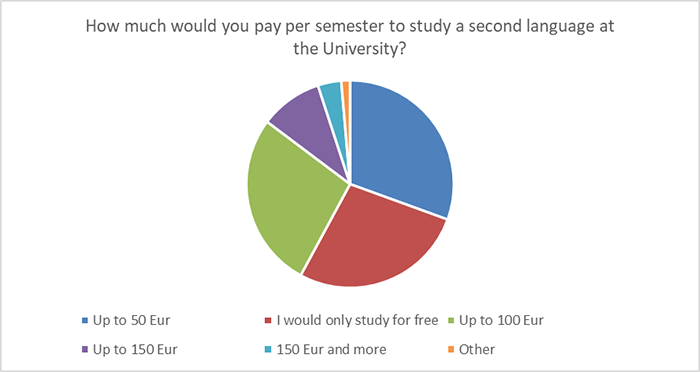

The last question in the survey was about students’ readiness to pay for the courses to study a second language at VU. Figure 10 provides the data on students’ answers.

Figure 10: Students’ readiness to pay for second language studies at VU

It seems clear from Figure 10 that more than one-quarter of students say that they would only study a second language for free (N=180). Nearly the same number of students would be willing to pay either 50 euros (N=201) or 100 euros (N=180). The minority of the respondents would be willing to pay 15 euros or more (N=64, N= 24 respectively).

4. Students’ suggestions to improve language courses at Vilnius University

During the research study, the respondents were invited to provide their comments on how the current state of teaching languages at Vilnius University could be improved. Having performed the content analysis of their answers, several recurrent categories and subcategories have been identified.

Category 1. Suggestions for the overall language policy at VU.

It seems clear that students are fully aware of the value of studying languages. They also understand that foreign language studies are a valuable asset to the university and its prestige on the international level. Some of their answers are intertwined with the repetition of the same idea – the lack of opportunities for foreign language studies at VU. Some of the students’ answers are presented below:

‘In order to raise the indicators of internationality, the university should promote language education – a graduate must know more languages than a student when entering higher education.’

‘A university graduate must know more languages than a student entering university.’

‘There should be an opportunity to expand knowledge of a foreign language. The more languages you learn, the more acquaintances and opportunities you have around the world.’

‘Please, if it is possible make more groups, because our world is becoming more open, and I really want to take advantage of the opportunity to learn a new language at university, but for now it is practically impossible.’

Category 2. Not all study programmes provide professional English courses (courses of English for specific purposes – ESP).

The students in the Faculty of Medicine expressed dissatisfaction with the absence of a course for professional English courses. According to the Concept of Foreign Language Teaching at Vilnius University, these courses are compulsory and should be included in all first-cycle study programmes; however, several of them (e.g. medicine and dentistry) have excluded them from their curriculum. Students’ answers were as follows:

‘The most relevant problem is that not all study programmes include professional ENGLISH. In medical studies, this is unfathomable, why is there inequality between the study programmes, for example, the Life Sciences Center students of the microbiology programme had professional English language courses, and the students of the Faculty of Medicine of the study programme of Medicine did not.’

Category 3. Limitations in the choice of the second foreign language offers, and limitations of places for the courses.

Subcategory 1. More places for second language courses, more information about their choice, and other opportunities to study languages. As stated above, currently, students have the possibility to study a second language as an extracurriculur course; however, the choice of languages and places is limited. The students’ responses are as follows:

The only suggestion is to expand the number of places so that all students have the opportunity to study a second foreign language and thus expand their knowledge and opportunities in the labor market.’

‘Previously, more foreign languages were offered. I really wish it would come back.’

‘To provide equal opportunities for foreign language education in all the faculties of the University by adapting the learning format (contact/distance/hybrid) accordingly.’

‘I’m glad that there are options, but I think they are somewhat limited.’

‘It would be nice if there was a wider choice of languages, as well as levels, and it would be great if master’s degree students (both Lithuanians and foreigners) could also choose languages.’

‘For now, language education at the university is superficial. I would like more advanced foreign language learning, more frequent lectures, and a wider choice of levels.’

‘I don’t know what the possibilities are, but perhaps it would be possible to make extracurriculur second language teaching groups separately for each faculty of VU (probably it would be easier to coordinate schedules, and more students would be able to take advantage of the opportunity), especially for those who would find it relevant in terms of further careers. For example, at the Institute of International Relations and Political Sciences, I really think there should be groups of French or German languages.’

‘I would also like to speak more loudly about other language courses. I personally learned about it after finding a section on additional subjects in VU IS. I think it would be possible to tell freshmen about it.’

Subcategory 2. Continuity of second language studies.

‘There should be continuity of courses at one level and then a possibility provided to continue depending on students’ abilities (e.g. if they studied at B1 they could continue at B2 already in the next semester).’

‘Our university should promote natural multilingualism. Also, it should offer a choice of locations and more language proficiency levels!’

Subcategory 3. The need for language courses because students have to read literature for their studies in multiple foreign languages.

Evidently, students highlighted the need for foreign languages for their studies as most of the literature is in foreign languages.

‘The university should organise as many different language courses as possible for students and publicise this information, because, in my opinion, knowing languages not only allows a person to be more culturally knowledgeable but also gives the opportunity to read articles, textbooks, and other literature in a foreign language, not only in Lithuanian or English. This would be a huge benefit, especially for those students whose literature (that is required for their studies) is practically non-existent in Lithuanian (like in the area of studies of molecular biotechnology), and it would allow us to better understand the relevant aspects of our studies.’

‘Language-level support classes or those during which you can get help in studying the material relevant to the subject studies would be relevant. For example, we have to read a lot of literature in English and it would be really interesting to have the advice of a linguist.’

Subcategory 4. The second language courses should be free of charge for all students.

According to the Concept of Foreign Language Teaching at Vilnius University, students have the possibility to study a second language as an extracurriculur course. that is partly paid for by the university and partly by the students themselves. The research participants wanted second-language studies to be included in their study programmes so that they could study languages within the framework of their curricula.

‘I noted that I would pay up to 50 euros, but I think that the university should give the opportunity to learn languages for free.’

Category 4. The possibility to choose another language instead of English for students who have C1 level.

According to the Concept of Foreign Language Teaching at Vilnius University, all the study programmes are to have compulsory first foreign language courses. Nearly all the study programmes (with the exception of very few) at VU follow this requirement.

“Stop torturing students who studied in the best Lithuanian schools in the 11th–12th grade according to the C1 programme and cancel those English lectures that do not bring any benefit apart from wasting time and filling credits.”

‘In my opinion, VU provides sufficient opportunities for students to learn foreign languages, but for students who have reached the C1 level of the first foreign language, it would be beneficial to transfer the credits of this language to learning the second foreign language.’

Category 5. Reference to various teaching options of teaching languages (ways, methods, modes).

The analysis of students’ answers revealed that they have many ideas and seem to be very creative in their suggestions on how to improve language teaching and learning at universities. Students encourage the use of more active teaching and learning methods, and the involvement of Erasmus students in the process of learning languages. Some of their suggestions are found below:

‘We need high-quality courses that encourage not only mutual communication of Erasmus students with Lithuanian students but also that there would be the possibility to talk with Erasmus students at VU during at least a couple of seminars. Currently, when foreigners come for exchange, they teach their languages to those who want to. I think it would be possible to encourage foreigners to join the teaching process more actively. ‘

‘Since I am studying four foreign languages at university, I would suggest giving up textbook teaching, when written exercises are to be done, thus in this way learning the language for two years and acquiring only B1 level. More active, lively, and effective language teaching could certainly be applied.’

‘It is rather difficult to interest students, especially those with advanced foreign language skills. Integration of real-life tasks, and lively discussions not only among students but also among teachers or visiting persons from Erasmus projects. Updating or replacing textbook assignments with case studies, court commentaries, or research articles.’

‘To prepare teachers so that their teaching is not dismissive, but truly inclusive. Even for a student who is learning languages and already knows them, the third language is also interesting, so teachers should not think ‘this is just a temporary thing for them’.

Category 6. Lithuanian language courses for Erasmus and international students.

The respondents’ answers revealed that they are concerned with the insufficient number of Lithuanian language courses offered to international students.

‘It is great that exchange students have the opportunity to learn Lithuanian, but I have heard quite a few complaints from permanent international students that they do not have such an opportunity (or are not informed about it). When you think about it, it is illogical that the University does not give them (enough?) opportunities to learn the national language, which should help later integration into our labor market...’

This study revealed that students’ suggestions for the improvement of the current language policy at Vilnius University are very accurate and insightful. Many of them have already been included in the draft of the Language Policy Guidelines and its Implementation Plan and hopefully will be put into practice as soon as the documents are approved and authorised by the Senate of Vilnius University.

Conclusions

Institutional language policy is considered a part of the university’s internationalisation process, and the universities themselves therefore devote significant resources to this endeavour. Evidently, universities seek to have a balance between internationalisation and the use of English as a language of communication on the one hand, and their state languages on the other, thus defining the extent to which these languages are to be used in the areas of studies, research, governance and university community life.

The development of Vilnius University’s Language Policy Guidelines alongside its Implementation Plan is also related to the processes of internationalisation. VU membership in the Arqus European University Alliance, as well as the development of the Arqus Charter of Language Policy, have been strong contributing factors to the initiation of the development of the VU Language Policy Guidelines.

The preparatory stages of the development of this important policy document at VU were based on the analysis of language policies at several European universities followed by an establishment of a working group to carry out the bottom-up process of its development. Numerous cycles of discussion and presentation as well as feedback, discussion and correction of the document revealed the necessary steps that still had to be taken. There was a need to provide a plan for the implementation of the Language Policy Guidelines to show how the policy would work in practice. Moreover, it became clear that the stakeholders’ discourses, needs and interactions also needed to be taken into consideration. Therefore, a more detailed analysis of the main stakeholder groups’ attitudes to language policy issues at VU was initiated.

The research study was carried out to identify one of the stakeholder groups – VU students’ viewpoints on one of the important aspects of the language policy – teaching and learning languages at Vilnius university. The research focused on three areas: a subject-specific Lithuanian language course and a subject-specific English language course (in terms of progress, content and teaching /implementation) and evaluation of the current state of the second foreign language teaching and learning at VU. Clearly, the most favourable evaluation of the necessity of a subject-specific Lithuanian language course is seen by fourth-year students. Generally, the trend to evaluate such a course within their study programmes as important seems to increase as the students go through their years of studies. The majority of the research participants expressed a more positive than negative view of the quality of subject-specific English language courses (in terms of their progress, content and teaching /implementation). However, students’ preferences to exchange their first foreign language credits for the studies of a second foreign language was quite clear. The analysis of the empirical research data suggests that students are informed about the possibilities to learn a second foreign language at VU but they would like to have a wider choices of languages, continuity of levels of proficiency, and additional opportunities to learn a second foreign language.

Thus, it can be assumed that the results of the research into students’ viewpoints revealed a rather positive evaluation of teaching and learning languages at VU. However, students clearly highlighted the areas of VU language policy where improvement seems to be necessary. The results of the research study appear to be valuable for the further development of the VU Language Policy Guidelines as well as its Implementation Plan.

References

AIREY, J., LAURIDSEN, K., RÄSÄNEN, A., SALÖ, L., & SCHWACH, V., 2017. The expansion of English-medium instruction in the Nordic countries: Can top-down university language policies encourage bottom-up disciplinary literacy goals? Higher Education, 73(4), 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9950-2

BLOCK, D., 2016. Internationalisation policies and practices in European universities: the development of language proficiency, intercultural competence and European citizenship awareness. Language Learning Journal, 44(3), 272–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2016.1198096

BULAJEVA, T., & HOGAN-BRUN, G., 2014. Internationalisation of higher education and nation building: resolving language policy dilemmas in Lithuania. Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development, 35(4), 318–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874431

EPICUR European Model Language Policy, 2021. Available from: URL https://epicur.education/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/EPICUR-European-model-language-policy7.pdf (accessed on April 4, 2022).

Center for Applied Linguistics. Available from: URL https://www.cal.org/areas-of-impact/language-planning-policy (accessed on April 4, 2022).

European Commision, 2017. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Strengthening European Identity through Education and Culture. The European Commission's contribution to the Leaders' meeting in Gothenburg, 17 November 2017. Available from: URL https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017DC0673&from=FI (accessed on April 4, 2022).

KAŠA, R., & MHAMED, A. A. S., 2013. Language Policy and the Internationalization of Higher Education in the Baltic Countries. European Education, 45(2), 28–50. https://doi.org/10.2753/EUE1056-4934450202

KĖVALIENĖ, D., & RAIPA, A., 2007. Pagrindiniai valstybinės kalbos politikos bruožai ir tendencijos. Viešoji politika ir administravimas, 19, 46–53.

KIBBERMANN, K., 2017. Responses to the Internationalisation of Higher Education in Language Policies of Estonia and Latvia. Journal of Estonian & Finno-Ugric Linguistics / Eesti Ja Soome-Ugri Keeleteaduse Ajakiri, 8(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2017.8.1.06

KORTMANN, B., 2019. Language Policies at the LERU Member Institutions. Briefing Paper No. 4 - November 2019. LERU: Publishing the Frontiers of Innovative Research. Available from: URL https://www.leru.org/files/Publications/Language-Policies-at-LERU-member-institutions-Full-Paper.pdf (accessed on January 15, 2022).

KRIAUČIŪNIENĖ, R., TARGAMADZĖ, V. & ARCIMAVIČIENĖ, L., 2020. Insights into the Application of Action-oriented Approach to Language Teaching and Learning at University Level: a case of Vilnius University. International Journal of Multilingual Education, 16, 1–22. Available from: URL http://multilingualeducation.org/en/article/51 (accessed on January 15, 2022).

KUTEEVA, M., 2014. The parallel language use of Swedish and English: the question of ‘nativeness’ in university policies and practices. Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development, 35(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874432

Lietuvos Respublikos mokslo ir studijų įstatymas. Available from: URL https://e- seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.343430 (accessed on March 20, 2022).

Lietuvos Respublikos valstybinės kalbos įstatymas. Available from: URL https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.15211?jfwid=rivwzvpvg (accessed on March 20, 2022).

MORTENSEN, J., 2014. Language policy from below: language choice in student project groups in a multilingual university setting. Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development, 35(4), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874438

ORDUNA-NOCITO, E., & SÁNCHEZ-GARCÍA, D., 2022. Aligning higher education language policies with lecturers’ views on EMI practices: A comparative study of ten European Universities. System, 104, Article 102692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102692

SAARINEN, T., & TAALAS, P., 2017. Nordic language policies for higher education and their multi-layered motivations. Higher Education, 73(4), 597–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9981-8

SCHIFFMAN, H. F., 1996. Linguistic Culture and Language Policy. London: Routledge.

The Guidelines for Internationalisation of Teaching and Learning at Vilnius University. Available from: URL https://www.vu.lt/apiemus/dokumentai#kiti-dokumentai (accessed on March 20, 2022).

The University’s Strategic Plan. Available from: URL https://www.vu.lt/site_files/VILNIAUS_UNIVERSITETO_STRATEGINIS_PLANAS_20212025.pdf (accessed on March 20, 2022).

The Concept of Foreign Language Teaching of VU. Available from: URL https://www.vu.lt/site_files/Reguliaminas/U%C5%BEsienio_kalb%C5%B3_mokymosi_koncepcija.pdf (accessed on March 20, 2022).

Vilniaus universiteto statutas, 2014. Available from: URL https://www.vu.lt/site_files/Adm/statutas/VU_statutas_2021_11_01.pdf (accessed on March 20, 2022).

Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija. Available from: URL https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/kalbu-politika/ (accessed on March 20, 2022).

Roma Kriaučiūnienė: Doctor of Social Sciences (Education), Professor, Director of

the Institute of Foreign Languages, Faculty of Philology, Vilnius

University.

Office address: Universiteto str. 5 LT- 01131, Vilnius,

Lithuania, telephone number +370 5 268 7266. Email:

roma.kriauciuniene@flf.vu.lt

Rasa Šlikaitė: Head of the Study Quality Unit, Central Administration of Vilnius University, Vilnius University.

Office address: Universiteto str. 3 LT- 01131,

Vilnius, Lithuania, telephone number +370 5 268 7055. Email:

rasa.slikaite@cr.vu.lt