The impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Language Teaching in Higher Education, CercleS survey

Sabina Schaffner

University of Zurich, University of

Bath

Language Center of UZH and ETH Zurich, Rämistrasse 71, 8006

Zürich, Switzerland

Email: sabina.schaffner@sprachen.uzh.ch

Orcid

ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4929-0171

Isabella Stefanutti

University of

Zurich, University of Bath

Language Center of UZH and ETH

Zurich, Rämistrasse 71, 8006 Zürich, Switzerland

Email: isabella.stefanutti@outlook.com

Orcid

ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0272-4278

Research Interests: Language and Intercultural communication; Methodology and didactics of foreign language teaching; International Education; Global Citizenship.

Abstract. In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic forced a move online of language teaching in Higher Education (HE). The CercleS survey on the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on language teaching in HE aimed to study teachers’ reflections on teaching during the pandemic and on the future of foreign language instruction. Data was collected between March and May 2021, and the answers reflect the voices of 725 teachers from CercleS member institutions of both national associations and associate members. The survey was written using a mixed method approach, based on a pragmatic epistemology. The findings indicate that the teachers moved flexibly into the online mode of teaching despite limitations in technological resources and the absence of training. Learning outcomes were met, and language skills were effectively taught, except for speaking skills. Generally, the respondents see the benefits of a blended/hybrid mode of instruction. Implications for teaching practices and stakeholders are as follows: develop guidelines and training for sustainable online and hybrid teaching; negotiate conditions needed to carry out efficient and sustainable language teaching with university management; and develop international collaboration between LCs in HE.

Key words: COVID-19 pandemic, language centres, online teaching/learning, teachers

JEL Code: G35

Copyright © 2021 Sabina Schaffner,

Isabella Srefanutti. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is

an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are

credited.

Pateikta / Submitted on

01.01.21

Introduction

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a major change in the work of Higher Education (HE) in Europe, forcing the teaching to move online (EUA, 2020). This move also affected teaching in language centres (LCs). Anecdotal evidence indicates that teaching and learning in LCs did not stop. There was a need to explore what happened, how LCs reacted to the move to online teaching, what staff learned from the experience, what worked, and what support LCs staff needed and might still need. The Confédération Européenne des Centres de Langues de l’Enseignement Supérieur (CercleS), is the main European umbrella organization that promotes networking and support of LCs in HE. Volunteers from CercleS member institutions formed a working group that designed and conducted a study, in the form of two surveys, on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on language teaching in HE. The surveys were sent, respectively, to LCs‘ teachers and LCs‘ managers.

The aim of both surveys was to identify the conditions and modes of delivery of language teaching and learning in HE during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to identify lessons learnt. This first step was considered essential in order to achieve further aims of the survey, namely to define criteria and policies for the different modes of future language teaching and learning in HE, and inform future planning of CercleS training and professional development events.

The analysis of the results of the teachers’ survey is the main scope of this paper.

1. Literature Review

By the end of March 2020, 95% of universities in Europe had entered lockdown and had moved, suddenly and disruptively, to online teaching (EUA, 2020). The closure of premises also affected LCs, with language teachers expected to carry on their tuition, often adapting face to face classes to synchronous and/or asynchronous online teaching (MacIntyre et al., 2020). This happened with little warning, technical preparation, or training (Ibid.), and teachers often lacked the necessary pedagogical competences and technical equipment to meet the requirements of technology enhanced instruction (Zamborova et al., 2021). The abruptness of the change in teaching practice, the uncertainty of how long the lockdowns would last, and the low familiarity (in some cases) with remote teaching, contributed to stress and turmoil for teachers (UNESCO, 2020). Further stress was caused by some teachers’ difficult personal circumstances and competing responsibilities, such as poor mental health, caring for vulnerable relatives or homeschooling young children (Kim and Asbury, 2020).

Online language teaching has been present in HE for over 30 years in different modes: web-enhanced Face to Face (F2F); synchronous or asynchronous online; blended (Kessler, 2017; Gacs et al., 2020; Maican and Cocorada, 2021). On top of the obvious benefits of removing temporal and geographical barriers, online language teaching has been found to be as effective as F2Fteachingand it offers several added advantages (Gacs et al., 2020). These advantages are: flexibility and adaptability; individualised learning; the use of authentic materials; richer communicative tasks; autonomous learning; and multilingual communities (Goertler, 2019). For some researchers, though, these advantages are limited by teachers’ and/or students’ poor digital skills, problems with internet connection, by some students’ low active participation or by some students’ dominance in synchronous online sessions (Artino, 2010). Furthermore, an effective teaching and fair evaluation of all language skills might be challenging in an online context (Maican and Cocorada, 2021).

Gacs et al. (2020), in agreement with Hodges et al. (2020), state that the HE move to online teaching in March 2020 was not actually a move to ‘proper’ online teaching, as it lacked all the pedagogical thinking and preparation necessary for teaching languages online. It was simply a move online to what would have been taught in the classroom if there had been no pandemic. This had some advantages: firstly, the fact that continuity was offered to students by teachers’ efforts to comply with the planned curriculum (Maican and Cocorada, 2021) and secondly, the fact that synchronously delivered interactive language classes brought normality to students who, otherwise, might have been experiencing fear and chaos their life (Egbert, 2020). Compromises, though, had to be found in relation to assessment and standards had to be lowered (Gacs et al., 2020). Even courses that were originally planned to be delivered online required some modifications, given the changed circumstances of teachers and students in the context of the global pandemic (Ibid.). However, students and teachers who either expected or had previous experience of online tuition displayed less discontent and lower levels of anxiety than students and teachers who experienced online tuition for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kamal et al. 2021; Zamborova et al., 2021).

HE has seen a digital acceleration because of the Coronavirus pandemic and digital models of learning and teaching are more widely used, also by teachers who had never used them before 2020 (Jics, 2020). Maican and Cocorada (2021) note that, during the lockdowns, students from humanities and social sciences disciplines (hence languages) felt synchronous lessons delivered through videoconferencing were useful, as they tended to replicate F2F interactions, even if they were broadly preferred by academically stronger students. In general, the flexibility to access resources at any time and the use of familiar tools (e.g., PowerPoint slides) were considered effective teaching tools, whereas any delayed form of communication with students was not considered as valuable, including individualised feedback on students’ performance, as it lacked immediacy and, hence, perceived relevancy (Maican and Cocorada, 2020).

What’s next, then, for language teaching in HE? The collective need of adapting language teaching in answer to the COVID-19 emergency has brought online teaching at the forefront of practitioners’ minds (Gacs et al., 2020; MacIntyre et al., 2020), and consequently it has become more familiar and better understood (Zamborova et al., 2021). Until recently, online and F2F, or synchronous and asynchronous teaching, were considered separate and mutually exclusive. With better understanding the boundaries between these forms of language teaching have become more blurred, and the benefits of each have become more apparent, both for the teaching and the learning communities (Kessler, 2017). It might be difficult, therefore,to go back to pre-COVID 19 times (Maican and Cocorada, 2020). However, if technology has great potential, any kind of technology used in an education context needs to be located within proven practices and models of teaching and needs to have a pedagogical value to enhance learning (Beetham and Sharpe, 2007).Any form of online teaching needs to be carefully planned and designed, teachers need to be clear on communication practices, stay visible and present for the students, establish a learning community, offer prompt feedback, and teach students how to learn online (Gacs et al., 2020). Furthermore, teachers should be given some release time or other compensation to adapt their teaching to online delivery and professional development opportunities (Ibid.). Finally, teachers’ professional identity and job motivation are often linked to their interpersonal relations with students, so particular attention needs to be paid in maintaining these in all teaching contexts (Kim and Asbury, 2020).

2. Methodology and data

Five volunteers from CercleS member institutions formed a working groupto investigate the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Language Teaching in HE. Two surveys were distributed to CercleS members between March and May 2021. The surveys were sent, respectively, to LCs teachers and LCs managers and aimed at investigating:

- The changes in professional practice forced by the lockdowns in European universities in spring 2020

- The lessons learnt from the experience

- Members‘ opinions on the future of language teaching in HE

For the scope of this article, we concentrate on the teachers’ answers only.

2.1. Research design

CercleS brings together almost 400 Language Centres, varying in nature and size. Given this variety, a sizable amount of data had to be collected to obtain statistically significant data, and a survey was sent to 365 CercleS institutional members and 23 CercleS associate members.

The survey was written using a mixed method approach, based on a pragmatic epistemology. Adopting Bryman’s (2016) definition, a mixed method approach combines quantitative and qualitative research. Quantitative data was collected through 75% of the questions in the survey: these were close-ended questions and could be answered by selecting from a limited number of options, usually multiple-choice answers, or rating scales. However, some further information was required to understand the quantitative data better, and also to acknowledge the different experiences in each European country and the cultural, linguistic, institutional, personal and contract differences of each individual respondent. For this reason, respondents were asked further information, and 25% of the questions were open-ended, offering valuable qualitative data. Microsoft Forms was used to publish the survey, and it was chosen for its user-friendly features and for its universal accessibility. The survey included 31 questions divided into sections: demographic information (5 questions), changes in professional practice (14 questions), lessons learnt during the pandemic (7 questions), the future of language teaching and learning in HE (5 questions). The approximate time for completing it was 15–20 minutes.

2.2 Data collection and ethical considerations

The results were analysed by the team of researchers, divided into two subgroups. Each subgroup analysed a different set of questions. A Microsoft Teams team was created to allow collaboration in the analysis, and the results were discussed during regular videoconferencing meetings. The collaborative analysis of the qualitative data resulted in a more informed and unbiased investigation, as it was enriched by different perspectives and not affected by individual interpretation (Cornish et al., 2014). No data was excluded from the analysis.

Ethical guidelines were followed in completing this research. At the time of accessing the survey respondents were informed of the goals of the research. Furthermore, they were told how the data would be used, that their participation was anonymous and voluntary, and that all data was collected and stored securely in accordance with the 1998 UK Data Protection Act (https://www.bath.ac.uk/guides/data-protection-guidance/).

3. Empirical Research findings, Discussion and Limitation

3.1 Empirical Research Findings

The CercleS survey aims to enrich the understanding of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on language teaching. Other investigations have been done on this topic, but the originality of this study is its interest in exploring the teaching in European HE and, in particular, in LCs. Furthermore, its final aim is developing a common vision and policy for the future of language teaching in HE. Information was sought about the respondents’ work place, the changes in their professional practice in spring 2020, the lessons learnt from this change, and their thoughts about the future of language learning in HE.

Statistically, with a probability of 99% (confidence level), this result of the survey is valid with a margin of error (confidence interval = accuracy) of +/−5% for the entire population. The Z-value, which is 2.58 based on the confidence level, is constant and represents the usual mean or denotes the number of standard deviations that lie between the chosen value and the population average. Standard deviation is 0.5, which indicates how densely the data cluster around the mean. A value of 50% (worst case) ensures that the sample size is large enough.

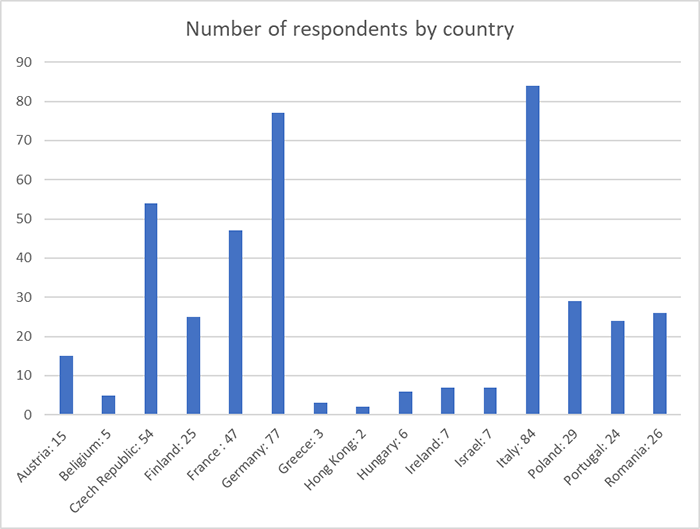

Information was sought about the country (Figure 1) and place of work of respondents, and about the nature of their contracts. (It was supposed that the kind of contract held might have affected the experience of teaching during the pandemic, therefore this was considered important).

Of the 725 teachers, 66.3% worked in LCs, 14.9% worked in departments with a degree programme, and 16.8% worked in both LCs and language degree courses, hence the majority worked in LCs. Of the respondents, 86.3% were language teachers, lecturers or teaching fellows, and 45.4% had a full-time permanent contract, while 21% had a part-time permanent contract.

Figure 1: Representation of countries of work

According to the data, most respondents had to start teaching online (in some form) in March 2020. Respondents identified that, almost overnight, their workload changed. For some the transition was very difficult: 32.4% of them were not provided with adequate hardware by their university, 40.6% of them were not relieved from other duties and only 24,8% of respondents received encouragement and/or professional recognition in response to their efforts.

‘All language instructors were left overnight to our own devices. The only indication we were informed about was that our University had paid for the Microsoft Teams Licence, so as to ‘facilitate’ our on-line teaching. We had to survive as best as we could’ (Respondent from Spain).

And:

‘My home computer was eight years old and not suitable for video so I managed to get them [the University] to pay for a small upgrade in the way of a new RAM, but it did not improve things much. I have had to purchase my own laptop. I was told that I had to pay for it myself’ (Respondent from the UK).

For some respondents the transition was less problematic: 63% of them said that their university provided them with adequate and ongoing IT and training support and 56% of them thought they had all necessary dedicated workspace and technical equipment to guarantee a smooth transition.

‘My University provided me and other lecturers or academic teachers with a series of IT training courses. We have become familiar with all technological devices and platforms to use during classes’(Respondent from Germany).

And:

‘The University reacted quite quickly, providing us online support and new tools’ (Respondent from France).

The four most challenging aspects of the pandemic for the respondents were as follows: coping with an increased workload, coping with the uncertainties of the pandemic, lack of knowledge about online teaching, and lack of support in the change of teaching practice. To face these challenges, respondents found the following support useful: online support spontaneously organised by peers (57%), online support on remote teaching set up by the department (49%), and the IT support organised centrally by universities (38%). Generalist webinars and online courses (31%) as well as health and well-being practices (for instance, exercise and mindfulness) (22%) were not considered as valuable.Despite the difficulties, 62% of respondents felt confident that the learning outcomes of their courses were achieved, with only 1% thinking they were not achieved. 37% of respondents answered that the learning outcomes were partially achieved. This ambiguous answer was explained in several ways in the qualitative data.

Firstly, learning outcomes were partially achieved because the original ones were modified:

‘For the most part the learning outcomes were achieved, as these were revised and adapted during the spring semester’ (Respondent from Germany).

Secondly, due to the modification of evaluation, it seemed impossible to assess students’ learning:

‘The exams became open-book exams and organised online. The students did not take them very seriously’(Respondent from France).

Thirdly, partial achievement may be explained because stronger students met the learning outcomes, while the weaker ones did not:

‘Distance learning does not suit everyone. Weaker students would need more face-to-face communication, the online form was not efficient enough’ (Respondent from Germany).

Finally, for some respondents it is too early to evaluate if teaching was effective:

‘My view is that we all had to convince ourselves, each other, participants and management that the quality of teaching and learning was not compromised. We must do it to convince ourselves and others that we are competent. However, as time goes by, we will be more willing to admit that this was simply not the case’ (Respondent from Germany).

Asked to reflect on the lessons learnt by teaching synchronously online in comparison to F2F teaching, respondents agreed on several points.

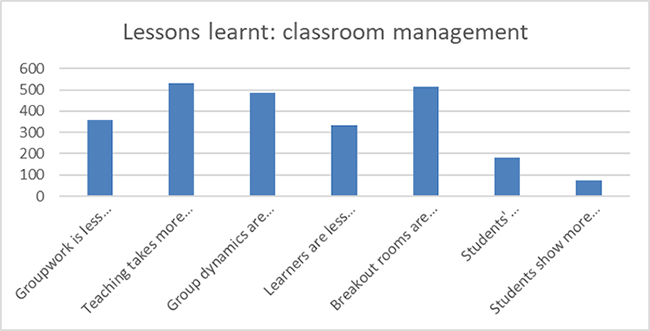

Figure 2: lessons learnt on classroom management

In relation to classroom management, 73% of respondents agreed that teaching takes more time and 70% that breakout rooms are effective for peer and group work. However, 67% said that group dynamics were more difficult and 49% said that group dynamics were less diverse when teaching online, and 90% thought students were less satisfied.

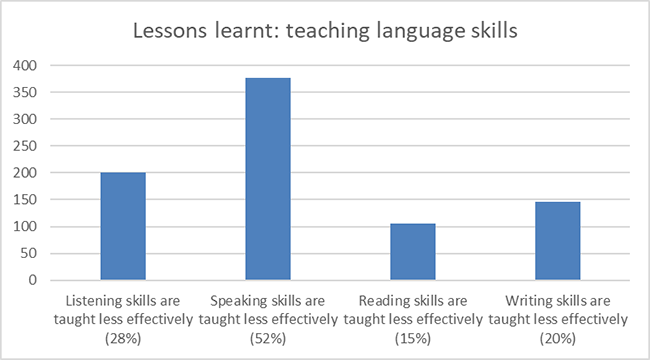

Figure 3: lessons learnt on teaching language skills

In relation to teaching language skills, most respondents agree that reading, listening and writing skills are taught effectively also online, but 52% of the respondents think that speaking skills are better taught in F2F teaching.

Thinking of learning outcomes and students’ motivation, the answers were less homogenous. 28.5% of the answers indicated that students showed more commitment during the forced online learning than before the pandemic, with 40.6% unable to comment. 37.5% of the respondents said that the students showed more commitment to self-study tasks than before the pandemic, and 38.6% said that the learning outcomes were as high as before the pandemic.

The future of language teaching in HE was considered positively by 64% of respondents, and negatively by only 12%. The remaining 24% of respondents did not know.

Languages and intercultural competence are considered too important to be challenged by online learning:

‘Languages, intercultural communication and soft skills will be needed in the future, and I do not think they will disappear from HE. The format may change, the methodology as well, however the disciplines will still have their place there’ (Respondent from Germany)

Furthermore, the new skills learnt by teaching online will stand teachers and students in good stead for a positive future for languages.

‘The remote teaching experience gave me the opportunity to try new methods and tools, which can be also implemented once we are back F2F. Students gained familiarity with technology and this will help them with their studying and working career and with lifelong learning, including language learning. Foreign languages will be more and more important’ (Respondent from Germany).

However, a less positive outlook is also presented, although this seems to be limited geographically to the UK and France.

The decline of language learning in the UK has continued and Brexit has had a negative effect. To be honest, I am tired of having to raise the profile of languages in my institution – I feel sapped of energy and enthusiasm’ (Respondent from the UK).

Looking forward, 64% of teachers would like to capitalise on the lessons learnt during the pandemic, teaching remote synchronous courses and F2F courses, depending on students’ needs. 51% of respondents would like to teach courses in hybrid mode, as it is considered convenient for both students and teachers. Only 31% of respondents would like to go back to teaching F2F only, as it was done before the pandemic.

In the qualitative data, three main concerns appear. Firstly, some mistrust towards university management, with the fear that online learning will be ‘imposed’ on foreign language teaching as a money-saving exercise:

‘The Governing Council of my university is in favour of the digital world and, using the pandemic as an excuse, I hope it doesn’t decide that it is easier and cheaper to go on with online learning. Language teachers continually claim in favour of F2F teaching and face to face assessment, but in vain’ (Respondent from Spain).

Secondly, the fear that the interpersonal relations with students can be damaged if teaching is solely done online:

‘Classroom discussions are essential for both students and teachers. Communicating with students F2F and the atmosphere in class is something I miss a lot, it’s my favourite part of being a teacher. It wouldn’t make sense for me to continue teaching without this aspect’ (Respondent from France).

Thirdly, the awareness that more training is needed to teach online, and that emergency online teaching is different from planned online teaching:

‘Although I would welcome the idea of introducing hybrid courses, I think enough time needs to be allowed to prepare for this. Impromptu hybrid classes are the worst thing ever to happen to language courses’ (Respondent from the UK).

4. Discussion

The CercleS survey described how language teachers in HE had to quickly adapt their F2F teaching to online format in March 2020, often with no planned training or even suitable IT equipment, as McIntyre et al. (2020) and Zamborova et al. (2021) apprise. This abrupt change, together with the uncertainties of the pandemic, was particularly challenging: workloads increased, most teachers were unfamiliar with online teaching, and they felt unsupported in the change of teaching practice. This is in line with other studies, which remark the increase in teachers’ levels of stress and turmoil at the start of the pandemic in March 2020 (UNESCO, 2020; Kim and Asbury, 2020). Despite the difficulties, teachers found that teaching was effective online, with most believing courses’ learning outcomes were met and that language skills can be effectively taught online, even if some concerns were expressed about speaking skills. Therefore, like Gags et al. (2020), most respondents believe that online teaching was as effective as F2F teaching, yet they fail to find added advantages, identified instead by Goertler (2019). Rather, some problems were identified by the respondents: firstly, the negative effects of teachers’ or students’ poor digital skills; secondly, the need to adapt evaluations and lowering assessment standards; thirdly, the observation that online teaching might suit stronger students, rather than weak ones. These problems were also identified by Artino (2010) and by Maican and Cocorada (2020).

Thinking of the future of language learning in HE, even if some teachers would like to go back to pre-pandemic teaching, most of them are ready to capitalise on the lessons learnt and adapt their work to the needs of the students, teaching online if required. Maican and Cocorada (2020) found the same in their researchconducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey notes that teachers are aware that more training is needed to teach online. The emergency course adaptations of March 2020 are now in need to be pedagogically refined, as it was discussed by Gacs et al. (2020). Teachers are also aware that training will be needed to ensure that interpersonal relations between teachers and students can be fostered even if the teaching is done online: these are essential to teachers’ identity and job motivation, as identified by Kim and Asbury (2020).

4.1 Limitations

The limitation of this survey is also its strength. Aiming to understand language teaching in HE after the COVID-19 pandemic, the survey was sent in March 2021 to 365 CercleS institutional members and 23 CercleS associate members. To achieve the aims of this study and to distinguish it from others, it was considered important to send the survey promptly and to ensure that respondents are professionals working in universities and connected to CercleS. However, it might be too early, even now, to define the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on language learning and teaching in HE. Furthermore, the selective group of respondents and the fact that participation in the survey was voluntary could have influenced the answers.

Conclusion

This study on the impact of the COVID 19-pandemic on foreign language teaching in HE adds significantly to other studies related to the same topic. The responses on the survey reflect the organizational, technical, social and pedagogical challenges encountered, while testifying of the commitment of language teachers in HE and their high performance as emergency teachers successfully coping with the pandemic.

Furthermore, the results of the survey also show the respondents’ interest to use the lessons learnt for their future teaching.,

Based on the survey’s outcomes, workshops with teachers (and managers) were organized to deepen the understanding of the results and get more meaningful insights into the respondents’ experience and acquired knowledge.

The analysis of the workshop outcomes led to the drafting of two papers informing future language teaching and learning in Higher Education – to the “CercleS Guide for LC managers on Language Teaching and Learning in Higher Education” on the one hand, and to the “CercleS Policy Paper on Language Teaching and Learning in Higher Education” on the other.

Both papers will be presented at the CercleS 2022 International Conference in Portoin September 2022. The first will hopefully support LC managers in their curriculum and personnel planning activities, and also inform future planning of CercleS training and professional development events and international projects.

The latter should contribute to present the LC managers’ needs and expectations and to successfully discuss them with University Management.

References

Artino, A., 2010. Online or face-to-face learning? Exploring the personal factors that predict students’ choice of instructional format. Internet Higher Education (13), pp. 272–276.

Beetham, H. and Sharpe, R. (2007). An introduction to rethinking pedagogy for a digital age. In H. Beetham and R. Sharpe (eds.), Rethinking pedagogy for a Digital Age. Abingdon: Routledge.

Bryman, A., 2016. Social Research Methods (5th edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cornish, F., Gillespie, A. & Zittoun, T. (2014). Collaborative analysis of qualitative data. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 79-93). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Egbert, J., 2020. The new normal?: A pandemic of task engagement in language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 53, pp. 314-319.

European University Association (EUA), 2020. European Higher Education in the Covid-19 crisis[Online]. Brussels: European University Association. Available from: https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/briefing_european%20higher%20education%20in%20the%20covid-19%20crisis.pdf [Accessed 30 March 2022].

Gacs, A., Goertler, S. and Spasova, S., 2020. Planned online language education versus crisis‐prompted online language teaching: Lessons for the future. Foreign Language Annals, 53, pp. 380–392.

Goertler, S., 2019. Normalizing online learning: Adapting to a changing world of language teaching. In L. Ducate and N. Arnold (Eds.), From theory and research to new directions in language teaching. Sheffield: Equinox, pp.51-92.

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., and Bond, A., 2020. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online teaching[Online]. Boulder: Educause. Available from: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the‐ difference‐between‐emergency‐remote‐teaching‐and‐online‐learning[Accessed 31 March 2022].

Kamal, M., Zubanova, S., Isaeva, A., Movchun, V., 2021. Distance learning impact on the English language teaching during COVID-19. Education and Information Technologies, 26, pp.7307-7319.

Kessler, G., 2017. Technology and the future of language teaching. Foreign Language Annals, 51, pp. 2015-1018.

Kim, L. and Asbury, K., 2020. ‘Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: The impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, pp. 1062–1083.

Jisc, 2020. Learning and teaching reimagined: A new dawn for higher education? Bristol: Jisc.

MacIntyre, P., Gregersen, T., Mercer, S., 2020. Language teachers’ coping strategies during the Covid-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System, 94, pp. 1-13.

Maican, M., Cocorada, E., 2021. Online Foreign Language Learning in Higher Education and Its Correlates during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 13, pp. 781 – 802.

Spilt, J., Koomen, H., and Thijs, T.,2011. Teacher wellbeing: The importance of teacher– student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 23, pp. 457–477.

UNESCO, 2020. Adverse consequences of school closures [Online].Paris: UNESCO. Available from: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/consequences [Accessed 30 March 2022].

Veldman, I., van Tartwijk, J., Brekelmans, M., and Wubbels, T., 2013. Job satisfaction and teacher– student relationships across the teaching career: Four case studies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 32, pp. 55–65.

Zamborova, K., Stefanutti, I., Klimova, B., 2021. CercleS survey: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on foreign language teaching in Higher Education. CercleS 11(2), pp. 269–283.