Vertimo studijos eISSN 2029-7033

2020, vol. 13, pp. 128–140 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/VertStud.2020.8

Reviewing the Reviewers:

(Re)Translations and the Literary Press

Mary Wardle

Department of European, American

and Intercultural Studies

Sapienza University of Rome

mary.wardle@uniroma1.it

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7225-7433

Abstract. Within the wider context of (re)translation and reception, this paper outlines a model for assessing how literary review publications address (re)translated works and whether there has been any discernable evolution in their approach over the period during which Translation Studies has emerged and consolidated itself as an academic discipline: the corpus comprises all issues over three separate years (1980, 2000 and 2018) of two international, English-language literary reviews (The New York Review of Books and London Review of Books). The analysis covers all reviews of works of literature translated from any language into English, both for the first time and retranslations, assessing whether there is any observable diachronic change over the time period in question. Although the scope of the material under inspection is limited, this study outlines the methodology developed for analyzing the manner in which reviews address translated texts and, more specifically, retranslations: this methodology, which involves classifying the corpus according to a taxonomy of features typical of the genre, is applicable to wider investigations across different languages, text types, time spans, platforms. Issues examined include how the reviewers assess the quality of the (re)translations; how texts are quoted; the significance of paratextual elements; the figure of the reviewer; whether retranslation is highlighted and/or reviewed differently to first translations. Future applications of the model are also considered.

Keywords: translation reviews; literary press; retranslation; model for review analysis

Recenzijų vertinimas: vertimai ir literatūrinė spauda

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje pristatomas modelis, kurį galima taikyti norint įvertinti, kaip recenzijose literatūrinėje spaudoje pristatomi knygų vertimai, ir keliamas klausimas, kaip keitėsi vertimų recenzijos ir verstinių knygų recepcija per maždaug 50 metų, per kuriuos vertimo studijos iškilo ir įsitvirtino kaip atskira akademinė disciplina. Autorė pateikia platesnį vertimų (ir pakartotinių vertimų) kontekstą, remdamasi 1980, 2000 ir 2018 metais išleistomis literatūros apžvalgomis ir recenzijomis, paskelbtomis dviejuose tarptautiniuose anglakalbiuose laikraščiuose – The New York Review of Books ir London Review of Books. Analizuojamos visos literatūros kūrinių, išverstų iš bet kurios kalbos į anglų kalbą, recenzijos, nepriklausomai nuo to, ar knyga išleista pirmą kartą, ar tai jos pakartotinis vertimas, vertinant, ar analizuojamu laikotarpiu pastebimas diachroninis jų vertinimo pasikeitimas. Nors tiriamosios medžiagos imtis yra ribota, šis tyrimas padeda parodyti sukurtos metodikos taikymo vertimų ir ypač pakartotinių vertimų recenzijų analizei galimybes: metodika, kurios esmė – tekstyno medžiagos klasifikavimas pagal žanrui būdingų ypatybių taksonomiją, gali būti taikoma platesniems tyrimams lyginant vertimus keliose kalbose, tekstų tipus, įvairaus ilgio laikotarpius, platformas. Tarp nagrinėtų aspektų yra kaip recenzentai vertina vertimo kokybę, kaip tekstai cituojami, paratekstinių elementų svarba, recenzento asmenybė, ar pabrėžiama, kad aptariamas pakartotinis vertimas, ir (ar) pastarųjų vertinimas skiriasi nuo pirmojo vertimo vertinimo. Aptariamas ir modelio taikymo galimybės ateityje.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: vertimų recenzijos, literatūrinė spauda, pakartotinis vertimas; recenzijų analizės modelis

Copyright © 2020 Mary Wardle. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

__________

As Hansjörg Bittner’s volume on translation quality assessment illustrates, there is a significant amount of research into “how to distinguish the acceptable translation products from the unacceptable ones and [how] to determine what makes for a successful target text” (2020: 2). Instructors, evaluators and editors follow a series of more or less prescriptive guidelines, often unwritten, in deciding who passes a university translation module, who gains membership of a given professional association, whose translation makes the cut for publication. Before suggesting a number of parameters for carrying out this task as objectively as possible, Bittner summarises the content of over sixty papers published on the topic, proof that the area is undergoing academic scrutiny. The discussion, however, is concerned solely with how to assess the suitability of the translation, with no regard for the qualities of the source text, the merits of the author, how the text exists within its original polysystem and might be received by the target culture. Yet, ideally, these are the functions we expect the review of a translated (literary) text to perform. Rainer Schulte sums up the situation as follows:

Since artistic creations affirm the complexity of the world, critics should help us to decipher that complexity and make us comfortable navigating through intricate layers of artistic insights. […] They can establish meaningful links with present and past authors who might have influenced the texts under consideration [and have] the ability to illuminate aesthetic affinities between a new work and its anchor in past literary traditions (2000:1).

If we turn our attention to how the literature engages with how translations are evaluated specifically in the context of reviews, the situation is quite different: what we find are sporadic expressions of disapproval at how translations (and, by extension, translators) are ill-treated, or rather, more often overlooked, and dismay at the general lack of awareness or consistency displayed by the reviewers. At the root of this is what Cecilia Alvstad refers to as the “translation pact”, “a rhetorical construction” through which “readers, including critics, literary scholars and other professional readers, often talk and write about translations as if they were originals composed solely by the author” (2014: 270). A case in point is that highlighted by Ronald Christ who, in 1982, publishes an exchange of letters in the Translation Review, entitled On Not Reviewing Translation: the correspondence begins with him taking a number of American literary reviews to task for not acknowledging the role played by the translator Helen R. Lane in the US publication of Ernesto Sábato’s novel Sobre héroes y tumbas, that had appeared the previous year. As Christ reports:

The San Francisco Chronicle and the Los Angeles Times not only ignored the translation in their reviews but also eliminated all credit to it in the book’s listing, as though Sábato had written a novel, On Heroes and Tombs, in English. And when it came to the so-called New York establishment–literary or trade–neither Publishers Weekly, The Saturday Review, The New York Times Book Review, nor The New York Review of Books mentioned the translation (1982: 16).

The exchange unfolds with various letters, subsequently sent in by some of the parties in question: reviewers, editors of literary reviews, Helen Lane herself who asks “shouldn’t major reviewers of major translations be routinely expected to do a bit of research regarding the relationship between the author and the translator that has resulted in the book that the American reader is reading?” (21) What emerges from these letters, for Christ, is that “while the reviewer or critic is the obvious target of a translator’s complaint, the editors, or more precisely, the editorial policy of the publications in question should be the prime target” (21). Indeed, the reviewer for the New York Times Book Review, Robert Coover, feels compelled to defend himself, confirming the low priority afforded to discussion of the translation when he states: “I’ve found […] that whenever cuts are requested by the publishers of a review, the first to go are usually the remarks about the translation” (17). In the letter Christ writes to the New York Times Book Review, amongst others, he concludes:

The Times […] has failed to insist, as a matter of editorial policy1, that its writers review the author we read in English —namely, the translator—as well as the author whose work that translator makes available to us. Each time the Book Review fails in this responsibility, it contributes to the economic pressure and literary neglect that make translating, all too often, an unrewarded struggle (17).

Other studies into how translations are reviewed tend to concentrate on the reception of individual authors or specific literary traditions at one synchronic moment in time. One such example is the research carried out by Meg Brown into the way German critics reviewed South American literature during the 1980s, again, like Schulte, focusing on the importance of the reviewers’ role in informing the new audience about a tradition with which they are less familiar:

the critic is vital in the diffusion of literature, in this instance Spanish American works of fiction. Critics respond to the Spanish American novels by analyzing the books and by formulating verbal images which are then to passed on to the public. Reviewers are thus ‘opinion-makers’ and ‘opinion-multipliers’ as they reflect the current social, literary, and ideological tendencies in a different culture and with a dissimilar set of norms from the culture in which the Spanish American novels were written” (1994: 89-90).

These studies, however, are few and far between: in 1995, thirteen years after Christ’s J’accuse, Rainer Schulte still has cause to write a very similar call to arms. He quotes the example of the then recent English-language translation of Isabel Allende’s Paula, translated by Margaret Sayers Peden, listing nine US newspapers or journals whose reviews make no mention of the translation whatsoever, a further eight who limit themselves to including mention only in the bibliographical heading, without any discussion in the review itself. Where the reviewers do engage with the translation, it is only perfunctorily, with statements such as “magnificently translated” or “[the] translation does ample justice to the original”; the survey also includes such logic-defying gems as “There’s no way an American reader can know if all this reflects the Spanish original. If not, Allende deserves a better translator”. As editor of The Translation Review, Schulte returns to the subject (2000; 2004), reporting little discernible light at the end of the proverbial tunnel.

While it should be stated that professional reviewers’ comments do not necessarily mirror public opinion or single-handedly exert a direct effect on the (un)popularity of any text–translations included–it is true that reviewers are part of the editorial process. As such, they contribute to the creation of the author’s identity and, along with all the other cultural gatekeepers–the translators themselves, the publishers and booksellers–they impact the reception of the textual content, whether online or on the printed page. It appears, therefore, that a systematic survey of translation reviewing is long overdue and, in light of Jeremy Munday’s observation that “there is no set model for the analysis of reviews in translation” (2016: 242), this article presents the initial phase of a project to investigate the lie of the land, with the aim of identifying the specificities involved in the reviewing of translated texts as opposed to texts published in their source language. It outlines the stages involved in establishing a model for analyzing the discourse of translation reviews, with objective criteria that can potentially be applied to corpora from diverse traditions, genres and eras. The guidelines also include parameters for distinguishing first translations from retranslations so as to assess whether the two categories are reviewed differently.

The corpus was selected to represent mainstream literary review publications around which to develop the model and test the methodology. As it stands, it is limited to two English-language publications, both published fortnightly: the British London Review of Books (LRB) and the American New York Review of Books (NYRB). The investigation presented here covers all issues published across three separate years for each, to provide a diachronic view of the field. An earlier hypothesis of analyzing one issue per year for all years was discarded to avoid potential idiosyncrasies tied to selecting only one given month (e.g. books being recommended for summer holiday reading around the months of July and August, as ideal Christmas gifts in the case of December or books linked to the Booker prize shortlist in September and so on). The three years chosen were 1980, 2000 and 2018. If we recognize the mid- to late-70s as the period in which Translation Studies begins to emerge as an autonomous academic discipline, 1980 can therefore provide an idea of the status quo within the publishing industry before translation becomes an object of more mainstream cultural debate: the reviews written in this period will presumably reflect the contemporary discourse of literary publications before any widespread contact with the meta-discourse of translation theory. The year also slightly pre-dates Christ’s piece (1982) and can therefore be useful in helping us form a picture of the situation to which he was reacting.

The next year under analysis is 2000: as well as being a halfway point between 1980 and the present, a twenty-year interval appears sufficient to monitor any noticeable change in attitudes or practices. Future research might include shorter intervals to ‘fill in any gaps’ that might manifest themselves in this initial phase. The third and final year, for now, is 2018, chosen as it was the last available ‘full year’ when the project was launched partway through 2019. A further criterion in drawing up the corpus was that of establishing the genre of texts being reviewed to include. Initially the decision has been to concentrate on works of fiction (novels, short stories, theatre and poetry) and consequently, material such as (auto)biographies, memoirs, essays, travelogues, and any other kind of non-fiction has not been included. From an initial cursory look at the publications in questions, non-fiction works appear to stimulate very little in the way of attention to translation and it was therefore considered that their analysis would contribute only to a limited extent in establishing parameters for any future study of criticism of translated works.

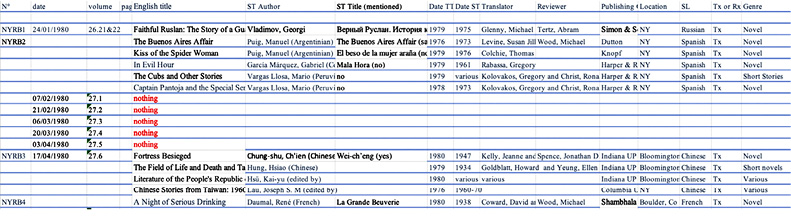

The first step was to consult the index of each issue where all reviewed volumes are listed: in the case of translations, alongside the title and the author of the ST, both publications include the translator’s name. All this information was uploaded into a spreadsheet (see table below) with columns for each of the following items: the number assigned within the corpus to each individual review of one or more volumes; the date of the issue; volume and issue number; page number; the English title of the work reviewed; author of source text; source text title (where mentioned); translation date of publication; ST date of publication; name of translator; name of reviewer; publishing company; place of publication; source language; whether 1st translation or retranslation; genre of ST.

Table 1: Example of data as collected in spreadsheet

The table above shows, for example, that in the first issue of the NYRB included in the corpus, published on the 24th January 1980, there was one review (here coded as NYRB1) of Michael Glenny’s translation of Georgi Vladimov’s novel Faithful Ruslan. The book had initially appeared in Russian in 1975 and had been published in 1979 for the first time in English, in New York, by Simon and Schuster. The same issue also includes a second review of translated literature, namely NYRB2, in which Michael Wood reviews two Manuel Puig novels and another by Gabriel García Márquez, alongside a collection of short stories and a novel by Mario Vargas Llosa. This first issue of NYRB is then followed by five further issues in which no translated works of fiction are reviewed.

The spreadsheet, therefore, already provides the researcher with precious information: which source languages/literary traditions are being selected for review; the identity of the reviewer (whether they are literary scholars, specialists in a particular field/language, or translators themselves); the way certain works are defined as belonging to a given tradition–as in the example above that groups three South American writers and their respective works together in one single review. Further data that emerges from the spreadsheet, before we actually begin to read the articles themselves, is the number of reviews of translated works present and, conversely, the number of issues in which no translations are reviewed. In the case of both publications–albeit less markedly in the LRB–there is a progressive inclusion of literature in translation and a gradual reduction in issues without reviews of translated works, as illustrated in the table below:

Table 2: Data regarding number of reviews of translated works

|

Year |

N° of issues in corpus |

N° of reviews of translated works |

N° of issues without reviews of translated works |

|||

|

LRB |

NYRB |

LRB |

NYRB |

LRB |

NYRB |

|

|

1980 |

24 |

21 |

9 |

14 |

16 |

12 |

|

2000 |

24 |

20 |

12 |

17 |

14 |

10 |

|

2018 |

24 |

20 |

12 |

24 |

12 |

6 |

Other positive trends observed at this stage of the project include the fact that by 2000, the NYRB has added a mention of the source language of translated works to the information in the index of each issue. We are therefore told, for example, that Edward W. Said’s article, The Cruelty of Memory, is a review of Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth by Naguib Mahfouz, translated from the Arabic by Tagreid Abu-Hassabo (emphasis added, NYRB 30th November 2000). Further prominence of the role played by translation can also be perceived in the inclusion of two essays dealing directly with the subject–Tim Park’s Perils of Translation (NYRB 20th January 2000) and Marina Warner’s The Politics of Translation (LRB 11th October 2018)–and one review of a volume about translation–Emily Wilson’s review of Sympathy for the Traitor: a Translation Manifesto by Mark Polizzotti (NYRB 24th May 2018). No such essays or reviews were present in any of the 1980 issues.

The next stage consisted in identifying the characteristics specific to reviews of translations and drawing up a list of these features, assigning a code for each and, subsequently, tracing them throughout the corpus. In this way it would be possible to observe any recurring behaviors, identify patterns, track changes over time. After the collection of data in the spreadsheet, therefore, the next task was that of compiling a database of all the reviews. In the case of both the NYRB and the LRB, all materials within this survey are available in digital format and, therefore, a file was created for each publication and all reviews were copied, so as to have a searchable resource. It was then necessary to read through a cross-section of reviews, from each publication, from different time periods, relating to translations belonging to a range of traditions: the purpose of this was to identify what would emerge to be recurring characteristics and draw up a taxonomy or standardized categorization of certain features typical of the genre–this list can naturally be added to subsequently. Once these features had been identified, it was then a case of returning to the corpus in its entirety and marking all occurrences of said features. Although ultimately the goal is to tailor a software program allowing the different parts of the corpus to be tagged according to the features they present, this first version of the project relied on color coding the material with the highlighting feature available in the standard word processing program. The following chart was developed:

Table 3: Taxonomy of features identified in reviews of translated texts

|

Color |

Features highlighted in text |

|

Color |

Features highlighted in text |

|

Pink |

Any general mention of the translation |

|

Bright green |

Any evaluation of the translation, whether positive or negative |

|

Grey |

Any material quoted in the source language (title, terminology, parts of the source text itself) |

|

Dark blue |

Quotes from the translation, acknowledging that it is a translation |

|

Yellow |

Quotes from the translation, with no acknowledgment that it is a translation |

|

Light blue |

Any mention of the translation/translator from an editorial or paratextual point of view (preface, notes, description of the cover, etc.) |

|

Red |

Any mention or discussion of retranslation and previous translators/translations |

|

Dark green |

Anything of general interest (e.g. prizes awarded to author, ST, TT or translator) |

A practical example of this might be the division of the following sentence as illustrated in the table below:

This long essay, published as a small book in German in 1969 and in English in 1974 as Kafka’s Other Trial, excellently translated by Christopher Middleton (Schocken Books), has been retranslated by Joachim Neugroschel and is included in The Conscience of Words, the selection of Canetti’s essays in Continuum Books’s admirable program for bringing virtually all of Canetti into English (Susan Sontag reviewing seven works by Elias Canetti, NYRB 25th September 1980).

Table 4: Example of color-coding applied to review excerpt

|

This long essay, published as a small book in German in 1969 |

Light blue |

|

and in English in 1974 as Kafka’s Other Trial, |

Pink |

|

excellently translated |

Bright green |

|

by Christopher Middleton |

Pink |

|

(Schocken Books), |

Light blue |

|

has been retranslated by Joachim Neugroschel |

Red |

|

and is included in The Conscience of Words, the selection of Canetti’s essays in Continuum Books’s admirable program for bringing virtually all of Canetti into English. |

Light blue |

The benefit of such a system is that, once all the colors have been added to the file, certain behaviors become apparent at a glance. Reviews such as that of W.G. Sebald’s Vertigo–translated by Michael Huse and reviewed by Tim Parks–end up with conspicuous amounts of text highlighted in yellow, as the translation is repeatedly quoted as though it were the source text. Typical sentences include:

“Afterwards” we are told, “he could no longer recall the name or face of the donna cattiva who had assisted him in this task.” The word “task” appears frequently and comically in Vertigo, most often in Thomas Bernhard’s sense of an action that one is simply and irrationally compelled to do, not a social duty or act of gainful employment (NYRB 15th June 2000).

The use of colors also draws the eye to how little attention is routinely dedicated to translation, especially in the earlier time frame. Michael Wood’s review of the five works by South American writers mentioned above (NYRB 24th January 1980), for example, while displaying copious passages in yellow–where the reviewer quotes extensively from the English TTs–does not engage with the translations in any way, leaving the almost 5000-word article with no traces of pink or green. It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, to notice that two of the volumes reviewed here–the works by Llosa–are in fact translated by Gregory Kolovakos and Ronald Christ, the same Ronald Christ who, two years later, would publish the exchange of letters in the Translation Review, lamenting the poor treatment afforded to translators. One cannot help but feel that this review must have contributed to the frustration that motivated his cri de cœur. As well as the frequently occurring features outlined in the color-coding table, there are a number of further characteristics that emerge, some with such low statistical frequency that they underline the often highly idiosyncratic nature of the corpus. One such atypical situation becomes evident from reading the very first article in the NYRB corpus: the review for the book listed as Michael Glenny’s English translation of Georgi Vladimov’s The Faithful Ruslan is in fact a review originally written in Russian by Abram Tertz about the Russian source text. Tertz’s review has then been translated into English (and abridged by William E. Harkins): so what appears to be the review of a then recent translation–the listing refers to the 1979 Simon and Schuster edition–was presumably written five years earlier when the book was first published in Russian and, of course, contains no trace of a reference to the English translation.

One of the many questions that arise from a study of the corpus is that of the reviewers’ qualifications for assessing translations. From the data collected in the spreadsheet, we can already observe how certain reviewers concentrate on one literary tradition while others range across a number of different source languages; some reviewers work on both journals simultaneously–a wider corpus would better highlight the true extent of their activities; reviewers are at times literary critics or academic figures; sometimes they are authors in their own right. There are some intriguingly revelatory comments such as that by Anthony Hetch in his review of a collection of verse by the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai, translated from the Hebrew by Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld (NYRB 2nd November 2000). Hetch quotes extensively from Amichai’s verses, or rather the translation of his verses, eliding the translation process, as evidenced by the heavy highlighting in yellow in the file created. Typical of this behavior is the way in which he introduces the quotations in English with expressions such as “we encounter this passage […]”, “in the following rather jazzy passage […]”, “the poet observes […]” or “a little later we come upon these lines […]. The 3600-word essay finally mentions the translation in its penultimate paragraph–163 words–where the translators are recognized as having “performed more than a commendable job”. The reviewer then states “I do not know the poem in its original”, revealing that he does not read Hebrew but is reassured by the fact that the translators had access to the author himself who “spoke fluent English”. This evaluation of the translation–the only part colored in bright green–concludes with the following statement: “It succeeds as a poem in English, and does so in ways that persuade us that it must be those very ways2 in which the Hebrew succeeds”. This somewhat enigmatic assertion–in which the reviewer clearly abdicates from any serious discussion of the translation–is coherent with the proportions of colored text.

The use of color-coding, therefore, as in the example cited above, outlines certain traits that, when gathered together and viewed as a whole, can reveal patterns of behavior. One such pattern that emerges quite clearly from the corpus is that related to the reviews of retranslations. There are a number of examples that do not engage with the fact that previous English-language translations of the text exist, such as John Bayley’s review of Richard Howard’s 1999 translation of Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma (LRB 17th February 2000). The only reference Bayley makes to the retranslation–or any previous translation for that matter–is the following sentence: “Any orthodox novel reader, picking up this excellent new translation by Richard Howard, would be stimulated into a desire to read further”. It must be said, however, that this reveals itself to be very much the exception when reviewing retranslations. The paragraph quoted below, from Gary Saul Morson’s review of translations of a number of Russian works by Isaac Babel, clearly illustrates a feature of retranslation reviews that can be traced across many other such articles. The names of previous translators are listed, often with accompanying editorial information, and passages from the different translations are compared:

The new translations by Boris Dralyuk and Val Vinokur, like Morison’s classic one, provide a readable text that captures much of what makes Babel’s stories great, but they often explain—that is, explain away—Babel’s oddities. In the story “Pan Apolek,” Babel begins a sentence: “V Novograd-Volynske, v naspekh smyatom gorode, sredi skruchennykh razvalin,” which, as literally as possible, means: “In Novograd-Volynsk, in the hastily crumpled city, amid the crooked ruins….” Vinokur gives us “In Novograd-Volynsk, among the twisted ruins of that swiftly crushed town,” while Dralyuk offers “In Novograd-Volynsk, among the gnarled ruins of that hastily crushed city.” And Morison: “In Novograd-Volynsk, among the ruins of a town swiftly brought to confusion…” (NYRB 8th February 2018).

This mode of review discourse foregrounds the translation, quotes from the translated texts clearly stating that they are translations and, in the process, implicitly underlines the fact that no single definitive version exists. Again, the color-coding highlights what emerges as a typical strategy in such cases: the names of the three (re)translators appear in red, closely followed by the excerpts from their (re)translations colored in dark blue. This red/dark blue combination (retranslation/quoting from translation, acknowledging it as such) can be recognized as typical in many reviews of retranslations and stands in contrast to the bulk of reviews of first translations with their predominant yellow color (signalling that translations are quoted as though they are the source text). Still on the topic of retranslation, another feature that the corpus highlights is the almost total lack of any terminology as having filtered through from Translation Studies. It is interesting to notice that, although the corpus includes twenty-seven reviews dealing with retranslations (12 in the LRB, 15 in the NYRB), there are only two mentions of the verb ‘retranslate’ in the NYRB and not one single mention of the noun ‘retranslation’. Similarly, throughout the corpus, there are only two occurrences of the verb ‘domesticate’ (in the NYRB), while neither publication contains the terms ‘domestication’ or ‘foreignize/foreignization’.

Despite this lack of translation studies terminology, one aspect that does appear to have migrated from academia to the corpus is the increased degree of general attention to translation over the forty-year span under investigation. An essay such as that by Emily Wilson, reviewing Barry Powell’s ‘new translation’ of Hesiod (NYRB 18th January 2018) is unlikely to have appeared in either of the two previous years included in the corpus. As with the example cited earlier, retranslation occasions a series of comparative assessments, with the mention of no fewer than seven previous translations, and an eighth forthcoming. Wilson comments on the paratextual elements–the translator’s introduction, the inclusion of maps and genealogical tables–and enters into detailed criticism of the translation itself before moving on to support her argument with elements of translation theory: “As Lawrence Venuti has reminded us, there is not necessarily anything wrong with a translation that draws attention to its own status as translation.” She then moves on to focus her attention on the treatment of gender in Powell’s translation, after pointing out, tellingly, that “reviewers, especially male reviewers, rarely comment on the gendered assumptions and biases of male translators.” From the title of Wilson piece (Doggish Translation) through to her conclusion, the entire essay centers on the translation and consciously includes comments relating to the meta-discourse of review-writing. It might be the only such review among those analyzed but it, arguably, indicates a certain degree of progression and, hopefully, bodes well for the future of reviewed works in translation.

While the project is still in its initial phase, the model developed already affords an empirical overview of the phenomena at play in the reviewing of translated works. Establishing a corpus, collecting the data in spreadsheets, compiling a database of reviews and color-coding the reviews allows the researcher to recognize patterns of behavior, to posit further questions, to interrogate the material for possible explanations and formulate hypotheses. Ideally, the corpus will be augmented, broadening the field of enquiry to include different genres of texts and different time spans; investigating cultures other than the English-speaking literary world analyzed here; looking at online reviews by both professionals and amateur critics. Future coding, carried out with descriptive markup language rather than colors, would mean being able to include a wider range of features, providing more nuanced and statistically accurate harvesting of data for subsequent analysis. Some of the questions that it would be interesting to investigate, through the prism of this model, include, amongst others, the criteria for selecting which works to review; the role played in this selection by literary prizes and the significance of their mention in the reviewing process; the influence of the professional standing of the reviewers–do ‘literary’ critics, academics, authors in their own right review differently? Is the translation reviewed differently when the translators are ‘famous’ in their own right, as in the examples in the corpus of Ted Hughes translating Euripides or Seamus Heaney translating Beowulf? Is there any correlation between the paratextual elements related to the translation–prefaces, notes, name on cover, etc.–and how the translation is subsequently reviewed?

In conclusion, as Rainer Schulte writes:

[I]t would be appropriate to start a study of the reviews that are published in many international newspapers and journals […]. A Critical investigation of how translations are reviewed […] might provide us with some guideposts toward a revitalization and expansion of reviewing translations (2004:1).

Although his comments refer specifically to the reception of foreign literature in the United States, the statement is equally valid when applied to all traditions, genres and platforms. I hope this paper can go some way towards laying the groundwork for a more systematic methodology to be adopted in the collection and assessment of data surrounding the practice of reviewing both translations and retranslations. The initial findings from the application of this model are encouraging in that they seem to indicate–although the size and nature of the corpus analyzed so far is not statistically representative of the more general picture–that certain trends can be identified, namely that translations of literary works, and more specifically retranslations, are beginning to attract increasing attention and that, overall, current reviews of such works appear to display a greater degree of awareness of translation discourse than their counterparts from forty or even twenty years ago.

References

Alvstad, Cecilia. 2014. “The Translation Pact.” Language and Literature 23 (3): 270–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947014536505.

Bittner, Hansjörg. 2020. Evaluating the Evaluator: A Novel Perspective on Translation Quality Assessment. New York: Routledge.

Christ, Ronald. 1982. “On Not Reviewing Translations: A Critical Exchange.” Translation Review 9: 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/07374836.1982.10524048.

Munday, Jeremy. 2016. Introducing Translation Studies. Introducing Translation Studies. Fifth Edition. | Milton Park; New York: Routledge.

Schulte, Rainer. 1995. “Editorial: The Reviewing of Translations: A Growing Crisis.” Translation Review 48–49 (1): 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1080/07374836.1995.10523655.

———. 2000. “Editorial: Reflections on the Art and Craft of Reviewing Translations.” Translation Review 60 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/07374836.2000.10523773.

———. 2004. “Editorial: Reviewing Translations: A History to Be Written.” Translation Review 67 (1): 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1080/07374836.2004.10523850.