Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2023, vol. 24, pp. 115–123 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2023.24.7

Crocodile Rock! A Bioarchaeological Study of Ancient Egyptian Reptile Remains from the National Museum of Lithuania

Dario Piombino-Mascali

Department of Anatomy, Histology, and Anthropology,

Faculty of Medicine, Vilnius University,

M.K. Čiurlionio 21, 03101 Vilnius, Lithuania

dario.piombino@mf.vu.lt

Rimantas Jankauskas

Department of Anatomy, Histology, and Anthropology,

Faculty of Medicine, Vilnius University,

M.K. Čiurlionio 21, 03101 Vilnius, Lithuania

Giedrė Piličiauskienė

Department of Archaeology, Faculty of History,

Vilnius University,

Universiteto 7, 01122 Vilnius, Lithuania

Rokas Girčius

Radiology and Nuclear Medicine Center,

Vilnius University Hospital,

Santariškių 2, 08661 Vilnius, Lithuania

Salima Ikram

Department of Sociology, Egyptology, and Anthropology, American University in Cairo,

AUC Avenue, P.O. box 74, 11835 New Cairo, Egypt

Luigi M. Caliò

Department of Humanities, University of Catania,

Via Biblioteca 4, 95124 Catania, Italy

Antonio Messina

Department of Humanities, University of Catania,

Via Biblioteca 4, 95124 Catania, Italy

Abstract. Remnants of what was believed to be a single baby crocodile, originating from ancient Egypt and curated in the National Museum of Lithuania, have been recently assessed using noninvasive and nondestructive techniques. These had been donated in 1862 to the then Museum of Antiquities by the prominent Polish-Lithuanian collector Count Michał Tyszkiewicz. After careful investigation of the three mummified reptile fragments available, the authors were able to identify at least two individuals based on morpho-anatomical characteristics. This indicates that the two small crocodiles originally described in historic records are still present within the collection and that none of these items was lost during the different lootings perpetrated throughout the museum’s history. Information regarding the post-mortem treatment of these animals was also obtained. This is the first scientific study of animal mummies in the Baltic States, and it should be followed by proper conservation and display of these findings.

Keywords: crocodile, mummification, bioarchaeology, Egyptology, Lithuania.

Crocodile rock! Senovės Egipto roplių iš Lietuvos nacionalinio muziejaus bioarcheologinis tyrimas

Anotacija. Pasitelkus neinvazinius ir neardomuosius metodus, ištirtos trys, kaip iki šiol manyta, vieno mumifikuoto krokodiliuko dalys, saugomos Lietuvos nacionaliniame muziejuje. Buvo žinoma, kad 1862 metais dvi senovės Egipto krokodiliukų mumijas tuometiniam Senienų muziejui padovanojo žymus Lenkijos ir Lietuvos kolekcininkas, egiptologas grafas Mykolas Tiškevičius. Šiuo metu muziejuje saugomi trys nedideli roplių fragmentai leido manyti, kad iki mūsų dienų yra išlikęs tik vienas individas. Kruopščiai ištyrę mumifikuotas krokodilo dalis nustatėme, kad jos yra ne vieno, o mažiausiai dviejų individų liekanos. Tai rodytų, kad istoriniuose dokumentuose minimi du M. Tiškevičiaus dovanoti krokodiliukai tebėra muziejaus kolekcijoje ir nė vienas iš šių eksponatų nebuvo prarastas per pastarųjų amžių muziejaus grobstymus ir kitas negandas. Be to, atlikti tyrimai suteikė informacijos, kaip ropliai buvo apdoroti mumifikacijos metu. Tai pirmas mokslinis gyvūnų mumijų tyrimas Baltijos šalyse, kurio rezultatai turėtų padėti tinkamai saugoti ir eksponuoti tokio tipo radinius.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: krokodilas, mumifikacija, bioarcheologija, egiptologija, Lietuva.

_______

Acknowledgments. We are most grateful to the National Museum of Lithuania’s curator Tadas Šėma and conservator Simona Matuzevičiūtė for their input into this research. Antonio Messina was partly supported by the Specializing School of Archaeological Heritage, University of Catania, Italy, headed by Professor Daniele Malfitana.

Received: 16/03/2023. Accepted: 02/12/2023

Copyright © 2023 Dario Piombino-Mascali, Rimantas Jankauskas, Giedrė Piličiauskienė, Rokas Girčius, Salima Ikram, Luigi M. Caliò, Antonio Messina. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Although ancient Egyptians are well known to have practiced human mummification throughout their civilization’s history, they also treated animal remains (Ikram, Dodson, 1998; Ikram, Iskander, 2002; Aufderheide, 2003). Animal mummies have been investigated for centuries, and are unique in that they open a window into past religion, food, and even affection (McKnight et al., 2018; Ikram, Iskander, 2002). The scientific assessment of this valuable bioarchaeological resource, which dates from the Late to the Roman Empire periods (circa 664 BC - AD 395), can provide information on their nature, their manufacture, and even on the pathological conditions the animal suffered over its lifespan (Ikram, 2005a; 2005b; Atherton-Woolham, McKnight, 2014; McKnight et al., 2015; Richardin et al., 2017; Johnston et al., 2020; Tamburini et al., 2021). In particular, crocodile mummies appear to be of great interest because they have been less studied as compared to other animals (De Cupere et al., 2023). This article deals with some reptile remains curated in the National Museum of Lithuania at Vilnius, which have been researched for the first time within the framework of the Lithuanian mummy project, a multidisciplinary investigation of mummified remains kept in this country (Piombino-Mascali et al., 2014). Historic records indicate that these were donated to the then Museum of Antiquities (a predecessor of the National Museum of Lithuania) by Count Michał Tyszkiewicz (1828–1897), a prominent antiquities collector and amateur archaeologist who carried out excavations in Luxor in 1861–1862 (Veprauskienė, 2009; Snitkuvienė, 2011). Specifically, the 1879 and 1885 catalogs of that museum report on the donation of two small crocodiles coming “from the Pyramids” (No 2559–2560, then renumbered as 255–256). However, an overview of the collections reveals that only one specimen, consisting of three different pieces, has survived the different lootings (Mulevičiūtė, 2003), and reports some of its details, and gives both the old (No 255) and the new accession numbers (Inv. No IM 4979) (Snitkuvienė, 2011). With this background in mind, the purported specimen was included in a recent exhibition and displayed according to the available information (Piombino-Mascali et al., 2021). In particular, this research aims to understand the nature of the remains by applying a zooarchaeological approach based on macroscopic and noninvasive techniques. Thus, in December 2022, a thorough examination of the items took place, supplemented by paleoimaging techniques to view the interior of the pieces. Broadly speaking, paleoimaging is the use of varied imaging modalities to capture visual representations of objects of antiquity for the purpose of data collection for interpretation (Beckett, 2014).

Materials and methods

The remains concerned are curated in the National Museum of Lithuania deposits in Vilnius, where they lie in a cardboard box (dimensions: 18 x 10.7 x 2.9 cm). They consist of three fragments comprising one head, one trunk, and one caudal third half of a baby crocodile (Fig. 1). The first two mummies are wrapped in coarse linen bandages, which in the case of the head, can be removed (Fig. 2). The noninvasive and nondestructive approach included both visual inspection and paleoimaging methods such as photography, X-ray analysis, and computed tomography (CT) (Beckett, 2014). Photo documentation was carried out using two reflex cameras, namely Nikon D90 and Nikon D7200. The images were acquired in NEF (RAW) + JPEG Fine format and were later modified using Photoshop. X-rays taken from the ventral part of the remnants were obtained via a SOFTEX M-150W device, employing 50kV, 1mA, and an exposure of 40 seconds. Lastly, CT was obtained using a LightSpeed VCT scanner (GE Medical Systems) with a slice thickness of 0.6 mm and a dose of 120 kVp. The bone data was recorded from the images available in dedicated manuals (Reese, 1915; Higgins, 1923; Romer, 1976).

Fig. 1. The reptile fragments held in a paper box at the National Museum of Lithuania in Vilnius.

1 pav. Lietuvos nacionaliniame muziejuje popierinėje dėžutėje saugotos reptilijų liekanos

Fig. 2. The three specimens juxtaposed after inspection.

2 pav. Krokodiliukų fragmentai atlikus tyrimus

Results

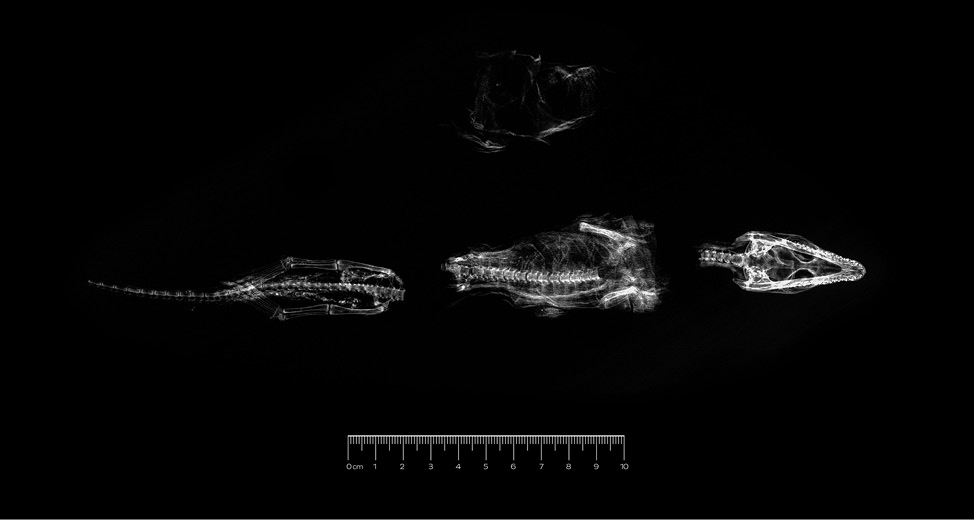

Three separate parts of a purported individual mummified baby crocodile have been analyzed with X-ray and CT images and sorted based on their anatomical features (Figs. 3 and 4). Part I of the mummy includes a baby crocodile skull, both mandibles and six cervical vertebrae including the atlas and axis. Part II of the mummy, which represents the trunk of a small crocodile, contains six thoracic vertebrae with thoracic ribs attached to each, five lumbar, two sacral, and two caudal vertebrae, as well as the pectoral girdle (coracoid process and scapula), both forelimbs (represented by a scapula, radius, ulna, carpal bones, metacarpals 1–5, and all phalanges), and the pelvis still articulated with the proximal parts of both femurs. The forelimbs were flexed in an ambulating position and held close to the body. Part III of the set is represented by one lumbar, two sacral, 25 caudal vertebrae, and the pelvis with both complete hind limbs, containing the femur, tibia and fibula, the tarsal bones, metatarsals 1–4, and all phalanges. The hind limbs are extended, close to the body along the tail. The left foot is placed on the tail and the right foot is placed under it. About one-third of the tail is missing. No evidence of trauma or lesion related to evisceration was observed on the fragments. However, dense agglomerations on the caudal fragment were observed both in the radiograph and upon the skin surface.

Fig. 3. The X-ray image of the three specimens shows the presence of two pelvic areas. Radiodense patches are also seen on the caudal part.

3 pav. Tiriamų krokodiliukų fragmentų rentgeno nuotraukos, kuriose matosi dvi dubens sritys. Uodeginėje dalyje matomi didesnio tankio židiniai

Fig. 4. A CT reformatted image of the trunk reveals the absence of any anthropogenic incision and stuffing with foreign material.

4 pav. Kompiuterinės tomografijos vaizdas, kuriame matyti, jog mumifikuojant krokodiliukus nebuvo padaryta jokio antropogeninio pjūvio ar įdėta svetimkūnių

Discussion

Mummies of crocodiles are of particular bioarchaeological interest. The ancient Egyptians associated these animals with the Nile, fertility, and military power (Moussa, 2021). Starting in the Middle Kingdom, crocodiles became very popular, as they embodied the god Sobek, who became a universal deity during the Ptolemaic and Roman eras (Bresciani, 2005). Hence, crocodile mummies could represent this specific god, but could also be votive offerings to him, or hold another religious meaning. The large number of findings indicates that there was an organized rearing system, aimed at their commercial distribution, with the most relevant worship centers being Fayum and Kom Ombo (Bresciani, 2005; Wilimowska, 2020). This is also confirmed by the large quantities of eggs, which suggest the existence of crocodile nurseries, possibly built next to watercourses or oases (Molcho, 2014). Baby crocodiles have also been found in great numbers, sometimes in association with adult specimens (Bresciani, 2005; Furmage, 2017; Anderson, Antoine, 2019). Either bred, hunted in the wild, or randomly retrieved, in ancient Egypt these animals were regularly mummified and carefully wrapped (Porcier et al., 2019; Berruyer et al., 2020). Their fascination has even lasted until today, as crocodiles continue to protect modern Egyptians against evil forces and natural calamities (Ikram, 2010).

The remains described in this paper likely belong to the first of the aforementioned categories and can be interpreted as votive offerings (Ikram, 2005a). Thus, their study can provide us with a more nuanced understanding of their nature and post-mortem treatment. In this respect, the adopted approach has been valuable and it helped us to carry out a virtual assessment, allowing correct anatomical positioning and interpretation. First of all, based on the presence of two pelvic areas in the observed specimens visible on both X-rays and CT images, it is clear that the three crocodile fragments analyzed here belong to at least two young individuals of the “true crocodiles” of the crown genus Crocodylus. Most likely these are the remains of the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), though it is possible that they may be the West African crocodile (Crocodylus suchus), as indicated by genetic tests of other mummified crocodiles from ancient Egyptian animal cemeteries (Hekkala et al., 2011; Hekkala et al., 2020).

Crown-group crocodilians share the same number of precaudal vertebrae: nine cervical, fifteen dorsal, two sacral vertebrae, and a slightly variable number of caudal vertebrae, which should generally be around 37 (Reese, 1915; Higgins, 1923; Romer, 1976; De Cupere et al., 2023). Therefore, Part I of the mummy (head and neck) is missing cervical vertebrae 7–9, and Part II of the crocodile (trunk) lacks thoracic vertebrae 1–4. The body of the mummy also lacks the sternum and almost all bones of the hind limbs, except for the pelvis and the two 3–5 mm long proximal parts of both femurs. Lastly, the tail of the crocodile (Part III) lacks about 12 vertebrae.

Judging from their size (total length < 0.5 m), the crocodile fragments examined in this paper belong to at least two very young individuals, which are classified as hatchlings and yearlings (Fergusson, 2006; Wallace et al., 2013). It is highly probable that the crocodile’s head (Part I) and body (Part II) belong to the same individual, i.e., a single broken animal mummy. Based on the information from the museum’s inventory, this mummy has been damaged in recent times. The separation of these two parts, and possibly a later attempt to connect them, may have damaged the cervical and thoracic parts of the crocodile and caused the loss of some skeletal elements. However, morphological analysis alone cannot prove if both pieces belong together, and only an ancient DNA test could help solve this question in a definite manner.

The third part of these mummified remains, which shows a pelvis, hind legs, and more than half of the tail definitely belongs to a different individual, as both this and the second part (the trunk) possess complete pelvic bones. However, based on the presence of the same wrapping in the first two parts, the most likely explanation is that the individuals represented here are only two: one consisting of the head and the trunk, and the other consisting of the caudal part of the body. Since the crocodile mummies donated to the museum in the 19th century were reportedly two, the hind legs and tail are probably associated with the second mummy that is mentioned in the inventory book (Snitkuvienė, 2011). The fact that only two out of the three fragments are covered by the same linen enables us to rule out that this is a “composite mummy”, as has often been found in similar cases, and that the original description of the two items is genuine (Atherton-Woolham, McKnight, 2014).

As far as the manner of the death of these two small crocodiles is concerned, the lack of any traumatic lesion on the skull and trunk of the first individual allows us to state that the killing of the animal was likely performed in a way that did not leave any obvious sign on the remains. This may have included drowning, suffocation, and heating exposure (De Cupere et al., 2023). No clear hypothesis can be put forward for the second individual, as most of the body is missing. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that such small animals were executed in the same way as you would expect for adult individuals.

A last point of interest is the way in which these baby crocodiles were treated to be preserved after death. Both X-rays and CT scans could not identify any clear incision suggestive of either evisceration of the trunk, or filling of the cavities with exogenous material. A crack that is observable on the body is, in all likelihood, a post-mortem defect unrelated to any embalming process (Fig. 4). In addition, only a small amount of bandages is visible in Part I and II. Overall, the most likely explanation is that these mummies were dehydrated, without internal organ removal, possibly through the use of salts or via burial in the sand, which is known to have absorbing properties and may have led to the desiccation of the specimens, perhaps supplemented by the use of resins prior to final bandaging (Aufderheide, 2003). In this respect, it is interesting to note that small reptiles mummify more easily than mammals, as their protective integument may delay the decomposition process (Cooper, 2012). The fact that radiographs of the caudal part revealed radiodense patches consistent with dehydrating material (possibly an admixture of sand and resin based on the dark color), which is absent from the other two findings, may be suggestive of a different treatment for the first individual.

Conclusions

The scientific study of the three fragments of baby reptiles from ancient Egypt held in the collection of a local museum in Vilnius, and believed to form only one single individual, has enabled us to establish that at least two separate mummified animals are present, which is consistent with historical records. This indicates that the two crocodiles donated by Count Michał Tyszkiewicz after his travel to Africa in 1861–1862 have survived until today.

The lack of lesions, at least on the best-preserved specimen, speaks for a modality of sacrifice that did not leave any sign on the remains, while the absence of evisceration indicates that these small reptiles were probably mummified via the use of sand or natron salt and possibly the addition of resin. This is the first research on animal mummies in Lithuania and it adds to the growing body of ancient Egyptian crocodiles being investigated by bioarchaeologists and other professionals alike.

References

Anderson J., Antoine D. 2019. Scanning Sobek. Mummy of the crocodile god. S. Porcier, S. Ikram, and S. Pasquali (editors), Creatures of earth, water, and sky. Essays on animals in ancient Egypt and Nubia. Leiden: Sidestone Press, p. 31–37.

Atherton-Woolham S.D., McKnight L.M. 2014. Post-mortem restorations in ancient Egyptian animal mummies using imaging. Papers on Anthropology, 23 (1), p. 9–17.

Aufderheide A.C. 2003. The scientific study of mummies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Beckett R.G. 2014. Paleoimaging: a review of applications and challenges. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology, 10 (3), p. 423–436.

Berruyer C., Porcier S.M., Tafforeau P. 2020. Synchrotron “virtual archaeozoology” reveals how ancient Egyptians prepared a decaying crocodile cadaver for mummification. PLoS ONE, 15(2), p. e0229140.

Bresciani, E. 2005. Sobek, lord of the land of the lake. S. Ikram (editor), Divine creatures. Animal mummies in ancient Egypt. Cairo: AUC Press, p. 199–206.

Cooper J.E. 2012. The estimation of post-mortem interval (PMI) in reptiles and amphibians: current knowledge and needs. Herpetological Journal, 22: p. 91–96.

De Cupere B., Van Neer W., Barba Colmenero V. Jiménez Serrano A. 2023. Newly discovered crocodile mummies of variable quality from an undisturbed tomb at Qubbat al-Hawā (Aswan, Egypt). PLoS ONE, 18(1), p. e0279137.

Fergusson R. 2006. Populations of Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) and hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) in the Zambezi. Zambezi Heartland: African Wildlife Foundation.

Furmage A. 2017. Two crocodile mummies from Late Period Egypt. The Inscriptions, 42: p. 9–11.

Hekkala E.R., Aardema M.L., Narechania A., Amato G., Ikram S., Shirley M.H., Vliet K.A., Cunningham S.W., Gilbert M.T.P., Smith O. 2020. The secrets of Sobek – a crocodile mummy mitogenome from ancient Egypt. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 33, p. 102483.

Hekkala E.H., Shirley M.H., Amato G., Austin J.D., Charter S., Thorbjarnarson J., Blum M.J. 2011. An ancient icon reveals new mysteries: mummy DNA resurrects a cryptic species within the Nile crocodile. Molecular Ecology, 20 (20), p. 4199–4215.

Higgins G.M. 1923. Development of the primitive reptilian vertebral column, as shown by a study of Alligator mississippiensis. American Journal of Anatomy, 31, p. 373–407.

Ikram S. 2005a. Divine creatures: animal mummies. S. Ikram (editor), Divine creatures. Animal mummies in ancient Egypt. Cairo: AUC Press, p. 1–15.

Ikram S. 2005b. Manufacturing divinity: the technology of mummification. S. Ikram (editor), Divine creatures. Animal mummies in ancient Egypt. Cairo: AUC Press, p. 16–43.

Ikram S. 2010. Crocodiles: guardians of the gateways. Z. Hawass and S. Ikram (editors), Thebes and beyond: studies in honour of Kent R. Weeks. CASAE, 41, Cairo, p. 85–98.

Ikram S., Dodson A. 1998. The mummy in ancient Egypt. Equipping the dead for eternity. Cairo: AUC Press.

Ikram S., Iskander N. 2002. Catalogue général of Egyptian antiquities in the Cairo Museum. Non-human mummies. Cairo: Supreme Council of Antiquities.

Johnston R., Thomas R., Jones R. Graves-Brown C., Goodridge W., North L. 2020. Evidence of diet, deification, and death within ancient Egyptian mummified animals. Scientific Reports, 10, p. 14113.

McKnight L.M., Atherton-Woolham S.D., Adams J.E. 2015. Imaging of ancient Egyptian animal mummies. Radiographics, 35 (7), p. 2108–2120.

McKnight L.M., Bibb R., Mazza R., Chamberlain A. 2018. Appearance and reality in ancient Egyptian votive animal mummies. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, 20, p. 52–57.

Molcho M. 2014. Crocodile breeding in the crocodile cults of the Graeco-Roman Fayum. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 100, p. 181–193.

Moussa W.F.I. 2021. Significance of the Egyptian crocodile on the Roman Imperial coinage. International Journal of Heritage, Tourism and Hospitality, 15 (1), p. 17–29.

Mulevičiūtė J. 2003. Forbidden monuments: the reorganization of the Vilnius Museum of Antiquities and its results [in Lithuanian with English summary]. The Year-book of Lithuanian History, 2, p. 45–64.

Piombino-Mascali D., Jankauskas R., Tarasenko M. 2021. What’s hidden in the sarcophagus? The first-ever Lithuanian mummy exhibition (2021-2022). Journal of the Hellenic Institute of Egyptology, 4, p. 141–144.

Piombino-Mascali D., McKnight L.M., Jankauskas R. 2014. Ancient Egyptians in Lithuania: a scientific study of the Egyptian mummies at the National Museum of Lithuania and the M.K. Čiurlionis National Museum of Art. Papers on Anthropology, 23 (1), p. 127–134.

Porcier S.M., Berruyer C., Pasquali S., Ikram S., Berthet D., Tafforeau P. 2019. Wild crocodiles hunted to make mummies in Roman Egypt: evidence from synchrotron imaging. Journal of Archaeological Science, 110, p. 105009.

Reese A.M. 1915. The alligator and its allies. New York: The Knickerbocker Press (G. P. Putnam's Sons).

Richardin P., Porcier S., Ikram S., Louran G., Berthet D. 2017. Cats, crocodiles, cattle, and more: initial steps toward establishing a chronology of Ancient Egyptian animal mummies. Radiocarbon, 59 (2), p. 595–607.

Romer A.S. 1976. Osteology of the reptiles. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Snitkuvienė A. 2011. Lietuva ir Senovės Egiptas. XVI a. pab. – XXI a. prad. Kaunas: Nacionalinis M.K. Čiurlionio dailės muziejus.

Tamburini D., Dyer J., Vandenbeusch M., Borla M., Angelici D., Aceto M., Oliva C., Facchetti F., Aicardi S., Davit P., Gulmini, M. 2021. A multi-scalar investigation of the colouring materials used in textile wrappings of Egyptian votive animal mummies. Heritage Science, 9, p. 106.

Veprauskienė S. 2009. Work of Lithuanian researchers in Egyptian archaeology [in Lithuanian with English summary]. Lietuvos archeologija, 35, p. 71–82.

Wallace K.M., Leslie A.J., Coulson T., Wallace A.S. 2013. Population size and structure of the Nile crocodile Crocodylus niloticus in the lower Zambezi valley. Oryx, 47 (3), p. 457–465.

Crocodile rock! Senovės Egipto roplių iš Lietuvos nacionalinio muziejaus bioarcheologinis tyrimas

Dario Piombino-Mascali, Rimantas Jankauskas, Giedrė Piličiauskienė, Rokas Girčius, Salima Ikram, Luigi M. Caliò, Antonio Messina

Santrauka

Publikacijoje pristatomi Lietuvos nacionaliniame muziejuje saugomų nedidelių mumifikuotų krokodilų fragmentų tyrimų rezultatai. Buvo žinoma, kad 1862 metais dvi nedideles senovės Egipto krokodilų mumijas tuometiniam Senienų muziejui padovanojo žymus Lenkijos ir Lietuvos kolekcininkas, egiptologas grafas Mykolas Tiškevičius (1828–1897). Šiuo metu muziejuje yra saugomos trys nedidelės krokodilų mumijų dalys (1 pav.). Manyta, kad tai vieno apie 25–30 cm ilgio krokodiliuko liekanos, mat vienas iš fragmentų buvo galvinė dalis, kitas – roplio kūnas, trečia – dubens sritis ir uodega (2 pav.). J. Mulevičiūtė (2003) taip pat mini, kad išlikęs tiktai vienas iš dviejų M. Tiškevičiaus atvežtų krokodiliukų, kuris yra sulūžęs į tris dalis.

Pasitelkus neinvazinius ir neardomuosius metodus – rentgeno ir kompiuterinės tomografijos tyrimus, taip pat atidžiai apžiūrėjus tiriamus fragmentus paaiškėjo, kad jie neabejotinai priklausė ne vienam, o dviem individams. Tai tapo akivaizdu dviejuose kūno fragmentuose identifikavus dubens kaulus (2 pav.). Be to, uodeginėje dalyje buvo išlikę ir jie, ir sveikos užpakalinės galūnės, o krūtinę ir juosmens sritį apimančioje dalyje, be apysveikių dubens kaulų, buvo matomi abiejų šlaunikaulių fragmentai. Tai rodytų, kad istoriniuose dokumentuose minimi du M. Tiškevičiaus dovanoti krokodiliukai tebėra muziejaus kolekcijoje ir nė vienas iš šių eksponatų nebuvo prarastas per pastarųjų amžių muziejaus grobstymus ir kitas negandas.

Greičiausiai galva ir kūnas priklausė vienam, uodeginė dalis – kitam krokodilui. Abu jie buvo labai panašaus dydžio naujagimiai ar kiek vyresni ropliai. Labiausiai tikėtina, kad tai Nilo krokodilai (Crocodylus niloticus), nors gali būti ir Vakarų Afrikos krokodilų (Crocodylus suchus) jaunikliai. Kaip parodė genetiniai tyrimai, buvo mumifikuojami abiejų rūšių ropliai. Krokodilų mumijų laidojimas senovės Egipte ypač išpopuliarėjo Vidurinės karalystės laikotarpiu. Jie buvo siejami su vaisingumu ir karine jėga. Mumifikavimui krokodilai buvo ir veisiami, ir medžiojami. Aukoti įvairaus dydžio ropliai – nuo naujagimių krokodiliukų iki itin didelių suaugusių individų.

Jokių dorojimo ar specifinių mumifikavimo žymių mūsų tirtuose krokodilų kūnuose neužfiksuota. Greičiausiai mumijos buvo padarytos neišimant gyvūnų vidaus organų, o roplius išdžiovinant natūraliai – smėlyje arba naudojant druską. Galbūt naudotos ir specialios dervos. Uodeginėje dalyje matomi didesnio tankio židiniai galbūt ir yra dehidruojančios medžiagos, pavyzdžiui, smėlio ir dervos mišinio, liekanos. Jų nesimato ant kitų mumifikuotų fragmentų. Turint omenyje, kad uodeginė dalis priklausė vienam, o kūnas ir galva – kitam individui, galima manyti, kad mumijos buvo gamintos skirtingu būdu. Tai pirmas mokslinis gyvūnų mumijų tyrimas Baltijos šalyse, kurio rezultatai turėtų padėti tinkamai saugoti ir eksponuoti tokio tipo radinius.