Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2022, vol. 23, pp. 79–87 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2022.23.4

A Newly Discovered Anthropomorphic Vessel from Eastern Bulgaria

Veselin Danov

Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, Bulgaria

veselindanov87@gmail.com

Abstract. The topic of prehistoric anthropomorphic sculpture, its presentation and interpretation are widely covered in the works of Marija Gimbutas. In her honor is the submitted paper, which presents a representative and very interesting vessel. It is a vessel in the shape of a human body, rare in the Eneolithic era.

The vessel was found accidentally on the surface of a settlement mound. It is partially preserved, but the available fragments allow to restore its shape and ornamentation. The massive legs and long feet allow the vessel to be placed upright. It is one of the most impressive specimens among this type of finds which represents a female mythological image, probably the Mother Goddess. Specific shape and ornamentation of the vessel suggest representative functions, probably used in various rites associated with prayers for fertility.

Keywords: Eneolithic, Anthropomorphic Vessel, Mother Goddess, Bulgaria.

Rytų Bulgarijoje naujai aptiktas antropomorfinis indas

Anotacija. Priešistorinės antropomorfinės skulptūros tema, jos analizė ir interpretacija plačiai gvildenamos Marijos Gimbutienės darbuose. Šis straipsnis, kuriame pristatomas reprezentatyvus ir labai įdomus indas, dedikuojamas jos garbei. Tai žmogaus kūno formos indas, retas eneolito eroje.

Indas atsitiktinai aptiktas senovės gyvenvietės paviršiuje. Indas išlikęs tik iš dalies, tačiau turimi fragmentai leidžia atkurti jo formą ir ornamentiką. Masyvios kojos ir ilgos pėdos leidžia indą pastatyti vertikaliai. Tai yra vienas įspūdingiausių tokio tipo radinių pavyzdžių, kuris reprezentuoja moters, tikriausiai Motinos deivės, mitologinį vaizdą. Specifinė indo forma ir ornamentika nurodo reprezentacines indo funkcijas – galbūt buvo naudojamas įvairiose apeigose.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: eneolitas, antropomorfinis indas, Motina deivė, Bulgarija.

__________

Received: 31/10/2022. Accepted: 28/11/2022

Copyright © 2022 Veselin Danov. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

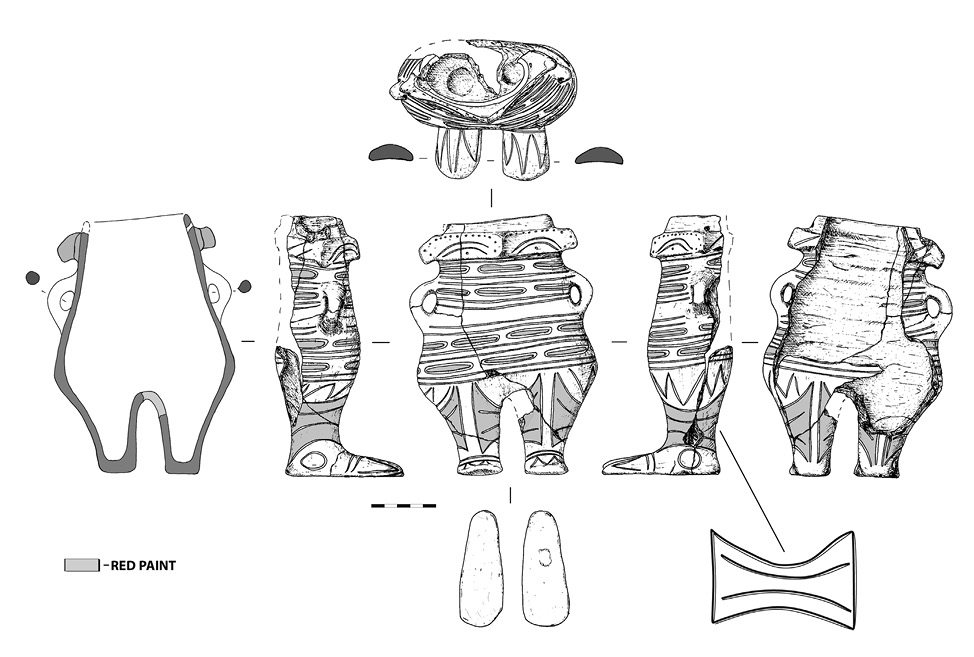

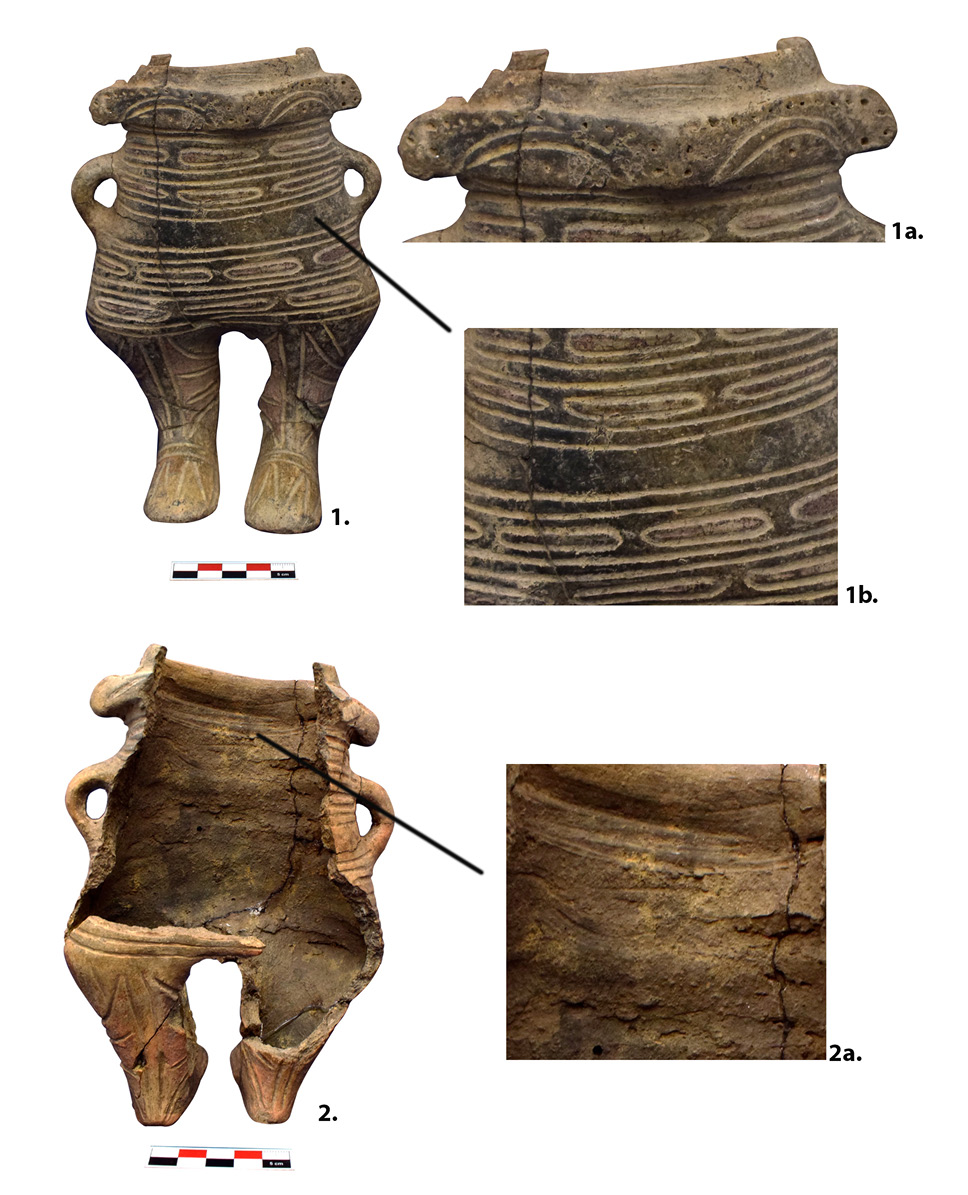

The subject of the present report is a newly discovered Late Eneolithic vessel of the rarely found anthropomorphic type (fig. 1; fig. 2). It was found on the surface of a settlement mound in some earth dug up at the making of animal dens. The vessel is partially preserved, with 13 surviving fragments belonging mainly to the frontal part.

Fig. 1. The anthropomorphic vessel from Goritsa (Drawings by V. Danov).

1 pav. Antropomorfinis indas iš Goricos (V. Danovo pieš.)

Fig. 2. The vessel from Goritsa (1, 2), details (1a, 1b, 2a). Photos by V. Danov.

2 pav. Indas iš Goricos (1, 2), detalės (1a, 1b, 2a). V. Danovo nuotrauka

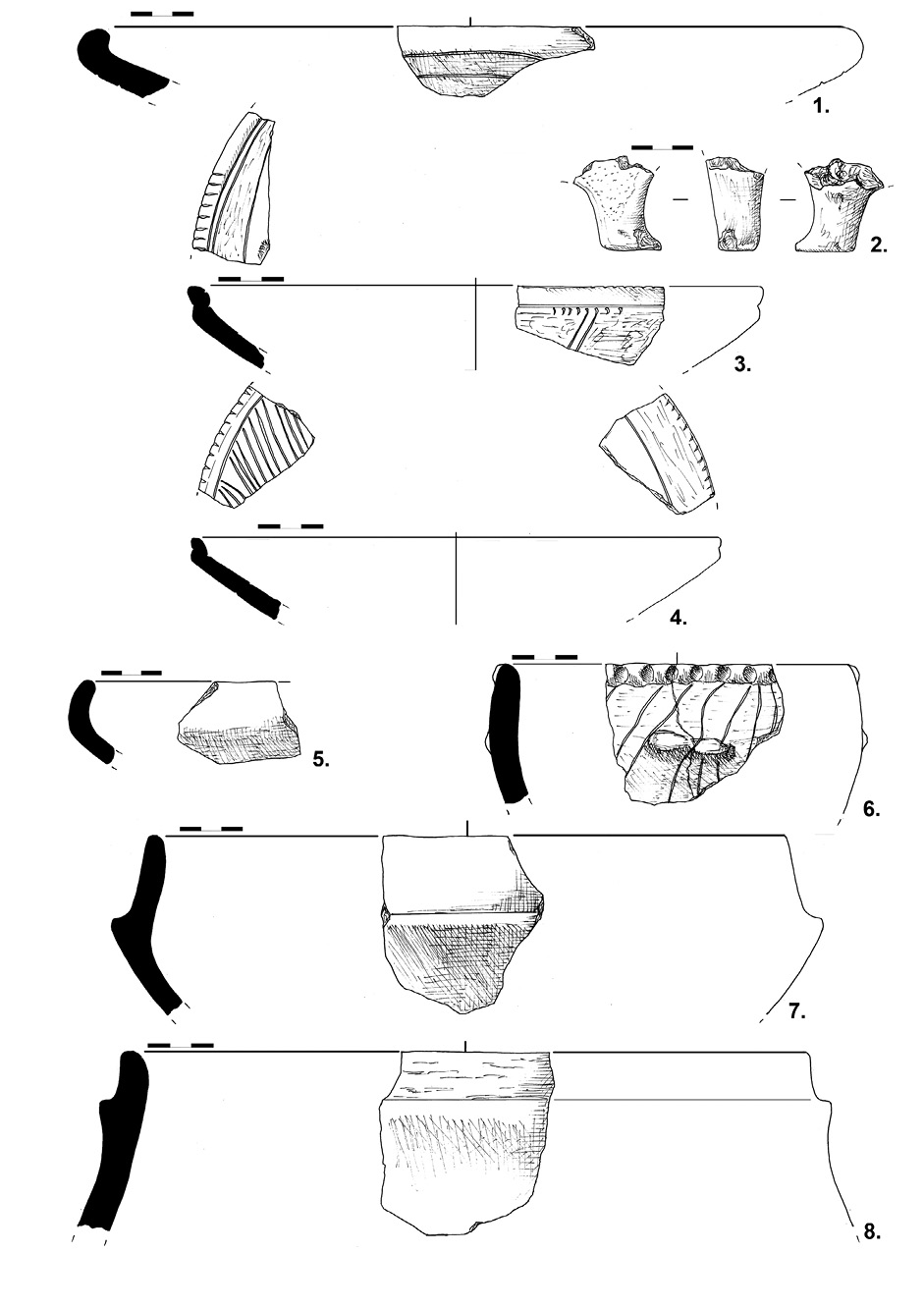

Location of find

The settlement mound from which the vessel originated is known by the name of Ploskata Mogila (fig. 3) to the local population. It is situated in the Kroushaka locality, 2 km southwest of Goritsa village, Pomorie municipality (Eastern Bulgaria), approximately 20 km away from the present Black Sea shore. Its diameter at the base is approximately 80 m and it is about 3 m high. Nearly the entire surface is cultivated by agricultural machines. The only exception is the highest part where many entrances to animal burrows were found (probably made by foxes or badgers). The latter, because of their large dimensions and considerable depth, limit the work of the machines. Numerous pottery fragments (fig. 4), isolated stone and bone items, as well as fired wall plaster are found on the surface.

Fig. 3. Photo of the settlement mound (1). Map of settlement mound Ploskata mogila near Goritsa (2).

3 pav. Gyvenvietės kalvoje nuotrauka (1). Ploskata mogila gyvenvietės prie Goricos žemėlapis (2)

Fig. 4. Pottery fragments found on the surface of settlement (Drawings by V. Danov).

4 pav. Gyvenvietės paviršiuje rastos keramikos šukės (V. Danovo pieš.)

The contemporary interurban road passes 150 m to the north of Ploskata Mogila. Here the Hadjiiska river forms a picturesque valley lying between the southern slopes of Mount Eminska and the northern slopes of Mount Aitoska.1 It is open to the east towards the Black Sea shore. Other prehistoric settlement mounds are known to exist along the flow of the river, forming a relatively thick settlement network in the upper and middle flow (Карайотов, 1986а, 1986б, 1986в, 1993а, 1993б; Райчевски, 2007, p. 38, 129; 132, 144, 151, 153). The site has not been studied by means of archaeological excavations.

Vessel description

Technological data

The vessel’s surface has irregular coloring, mostly beige. There are dark grey and grayish-beige stains at places. The outer surface is polished. The inner is coarse. The exception is the area directly under the mouth, which is well smoothed. This was the only clearly visible part of the interior of the vessel. The near-complete absence of additional work on the inner surface allows one to distinguish the outlines of the individual strips of clay dough superimposed on each other during its modelling (fig. 2: 2, 2a). The vessel is made of fine clay. Inorganic contaminants such as sand and small quartz grits were used (in low concentration), with sizes up to 2–3 mm.

Form

The Goritsa find belongs to vessels in the shape of a human body (Niţu, 1969, p. 22–24).2 About 2/3 of it have survived to this day. The frontal side is entirely preserved, as well as the feet and the handles. The buttocks and the back of the legs are partially represented. This allows reconstruction of the general shape, decoration and dimensions.

The vessel has a height of 20 cm and a maximum width (coinciding with the area of the hips) of 14 cm. The horizontal section at the mouth and the middle of the vessel is elliptical. The maximum diameter at the mouth is 8 cm.

The face is conveyed in a schematically manner (fig. 2: 1, 1a). It was made by sticking the clay strip in the upper portion of the vessel, directly below the mouth. The strip underwent additional modeling for the ears and the face, the latter divided into two planes which meet at an obtuse angle, the apex of which represents the nose of the figurine. Two pairs of parallel arcuate, incised lines mark the contours of the eyes. The pupils and eyebrows are suggested by pricks. The ears are presented as strongly marked lateral protrusions. Their front sides are perforated, but the holes do not extend through their entire volume to their back side. A hole is formed above the left ear, just below the edge of the mouth. It has a diameter of about 3–4 mm. There was probably also a similar one above the right ear, but now this part is broken off. It could be assumed that a thin cord was passed through these holes by which the vessel was suspended to hang in a certain place. It is possible that a lid was attached through it (again by means of a cord), which has not come down to us. Indirect evidence of its presence is the rougher treatment of the mouth (and the space below it) than the rest of the outer surface of the vessel. It is likely that this part was hidden under the lid.

The hands are stylized. They are represented as two small, vertical handles modeled in the upper part of the vessel. The legs are hollow and massive, shaped apart from each other. They have proportionally large, forward projecting feet made of compact clay.

Decoration

A large portion of the vessel’s surface is covered with incised decoration, made with the help of a wooden or bone object before it was completely dry. The incised lines are up to 2–3 mm wide, filled with lighter incrustations now preserved at places.

Four low, grouped two by two horizontal fields cover the upper and middle part of the vessel (fig. 1). Each is framed by two parallel incised lines within which elliptical motifs were incised in a row. The interior of the markedly elongated motifs was covered with partially preserved red paint. Now there are barely discernible traces of it.

The upper thighs are decorated with incised triangles (fig. 1). Four motifs cover a much of the surface of the legs, two on each leg. They have a near rectangular shape, with longitudinal sides curving strongly inwards. They are filled with red paint. Two curved lines facing each other are depicted in the middle of each.

The area of the ankles is marked with incised circles on the outer side of the feet (fig. 1). The upper side of the feet is also decorated with two parallel horizontal lines each, located in the middle, while the area at the front of the foot is decorated with triangular motifs.

Discussion

The tradition of making anthropomorphic vessels dates back to the Neolithic period and continued through the Eneolithic period throughout Southeastern Europe (Schwarzberg, 2011). They are undoubtedly among the most interesting and attractive objects made in the ceramic industry.

The Late Neolithic dating of the vessel from Goritsa is beyond doubt. The known similar finds originating from the territory of present-day Eastern Bulgaria and Eastern Romania are far from numerous. Their spatial and chronological distribution most generally coincides with that of the Late Eneolithic ethno-cultural complex of Kodjadermen–Gumelniţa–Karanovo VI. The most striking examples of such vessels are those from Gabarevo (Миков, 1933), Radingrad (Иванов, 1981; 1984а; 1984б), Starozagorski Mineralni Bani spa resort (Калчев, 2010), Pietrele (Hansen, Beutler, 2017, p. 32–33, fig. 3; Hansen et al., 2017, p. 28, Abb. 41–42), Vidra (Andreescu, 2002; Rosetti, 1939), Măgura Jilavei (Andreescu, 2002) and two vessels from Sultana (Andreescu, 2002; Marinescu-Bîlcu, Ionescu, 1967, p. 30–33, pl. IX, pl. X; Voina, 2005, pl. 106: 3, 4; Isăcescu, 1984, p. 17–19, fig. 2) (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Distribution of the most striking examples of Late Eneolithic anthropomorphic vessels in South-Eastern Europe.

5 pav. Ryškiausių vėlyvojo eneolito antropomorfinių indų pavyzdžių paplitimas Pietryčių Europoje

The specific shape and the very low percentage of anthropomorphic vessels found in relation to the total amount of household pottery suggest their different function compared to that of standard vessels. Most researchers associate them with the cult practices of ancient societies. Discussing the vessel from Gabarevo, V. Mikov assumed that it was used in an ancient “religious phallic cult” (Миков, 1933, p. 99). According to other scholars, its function was related to rites performed in connection with autumn sowing (Николов, 2006, p. 122; Николов, 2011, p. 176). H. Todorova believed that this type of vessels played “a certain role in primitive magic, having the task to ensure abundance” (Тодорова, 1986, p. 202). The vessel from Radingrad was also discussed in the context of agricultural cult practices associated with the invocation of fertility (Иванов, 1981, p. 71).

According to R. Andreescu, the anthropomorphic vessels belonged to people with a leading function in society. They were used in ceremonies and therefore had representative functions (Andreescu, 2002, p. 83–84). The researchers of the Pietrele vessel offered a similar interpretation. The situation of its discovery gives them grounds to assume the use of the vessel in feasts (Hansen, 2018, p. 234–235; Brummack, Karaucak, 2019, p. 111).3 These vessels are discussed in the context of the subject of social inequality in Eneolithic society and the role of feasts in bringing the community together (Hansen, 2018). The proliferation of this type of vessel and the probable beginnings of the creation of monumental sculpture in the late Eneolithic has been associated with changes in the social organization of ancient society (Георгиева, 2018, p. 123).

The number of common features shared in the shape and ornamentation of the clay figurines and anthropomorphic vessels suggest that they depict the same or very similar mythological characters. It is possible to assume their use in similar ritual practices. The shaping of the vessels as receptacles is leading in their functional differences. They are deep and closed. They were used to carry and store liquids or liquid foods (Тодорова, 1986, p. 202; Andreescu, 2002, p. 83–84, Opriș et al., 2017; Schwarzberg, 2011, p. 185).

The use of the Goritsa vessel in ancient cult practices, which undoubtedly had an important role for Eneolithic society, seems a logical assumption (especially in the context of opinions already expressed about similar finds). We could assume it was used in rites related to fertility. These rites should not necessarily be associated with the fertility of ‘Mother Earth’. It is possible that liquids (decoctions) having a beneficial effect on fertility in some family couples were placed in the vessel. We may assume its involvement in marital rituals or others associated with begging the continuation of the lineage.

The Goritsa vessel reveals the greatest similarities in overall shape and size with one of the vessels from Sultana. As regards decoration, the closest parallels are those of the Vidra vessels and ‘The Goddess of Sultana’ (although another decoration technique was used in its case). All are dated in the second or third phase of the Late Eneolithic. The dating of the other anthropomorphic vessels is similar, with the exception of the one from Radingrad. What has been said so far allows us to date the Goritsa vessel most generally in the second half of the Late Eneolithic.

Conclusion

Anthropomorphic vessels are among the most representative ceramic finds of the Late Eneolithic. They illustrate the high level of development of prehistoric culture in the second half of the 5th millennium BC. Some of the most striking examples of such are the “The Goddess of Sultana” (Marinescu-Bîlcu, Ionescu, 1967) and “The Goddess of Vidra” (Marinescu-Bîlcu, Ionescu, 1967, p. 29–30; Voinea, 2005, p. 65).

Whether these vessels should be perceived as an intermediary form between the anthropomorphic figurines and table pottery (Niţu, 1969, p. 22) or rather seen as a transition to monumental sculpture (Георгиева, 2018, p. 123), are questions that are difficult to answer definitively at this stage. Undoubtedly, their distribution falls in a period in which the presence of social differentiation is clearly perceptible in the necropolises (especially those of the Varna culture). In this context, the assumption that the owners of the vessels in question were distinguished by an important social status seems logical (Andreescu, 2002, p. 83–84; Hansen, 2018). On the other hand, the appearance of these vessels marks changes in religious rites and rituals, where they probably played an important role.

Although not fully preserved, the Goritsa vessel is one of the most impressive examples among anthropomorphic vessels. It completes our picture of them and marks their distribution in the southern part of the western Black Sea coast.

References

Andreescu R. 2002. Plastica antropomorfă gumelniţeană. Analiză primară. București.

Brummack S. & Karaucak M. 2019. Offsite studies at Pietrele, Măgura Gorgana: flat settlement formation around a Copper Age tell site in the Lower Danube. П. Георгиева (ред.) Филови четения. Балканска археология. Доклади от международна докторантска конференция 17–20 ноември 2016 г. – Bulgarian e-Journal of Archaeology/ Българско е-Списание за Археология, Supplementum 7, p. 93–117 [interactive]. Available at: <https://be-ja.org/index.php/supplements/article/view/197> [accessed on 20 April 2022].

Hansen S. 2018. Arbeitsteilung, soziale Ungleichheit und Surplus in der Kupferzeit an der Unteren Donau 4600–4300 v. Chr. H. Meller, D. Gronenborn, R. Risch (eds.) Überschuss ohne Staat – Politische Formen in der Vorgeschichte. 10. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 19. bis 21. Oktober 2017 in Halle (Saale). Tagungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle. Band 18. Halle, p. 221–245.

Hansen S. & Beutler K. 2017. Pietrele on the Lower Danube River. A settlement from the 5th millennium BC. S. Hansen (ed.) German Archaeological Institute Eurasia Department. Current Reserch in Eurasia. Berlin, p. 32–33.

Hansen S., Toderaş M., Wunderlich J., Beutler K., Benecke N., Karaucak M., Müller M., Nowacki D., Price T. D., Ritchie K., Steiniger D. & Vachta T. 2017. Pietrele am ‘Lacul Gorgana’. Bericht über die Ausgrabungen in der neoltischen und kupferzeitlichen Siedlung und geomorphologischen Untersuchungen in den Sommern 2012–2016. Eurasia Antiqua, 20, p. 1–116.

Isăcescu C. 1984. Staţiunea eneolitică de la Sultana – comuna Mînăstirea. Documente recent descoperite şi informaţii arheologice. București, p. 11–20.

Marinescu-Bîlcu S. & Ionescu B. 1967. Catalogul sculpturilor eneolitice din Muzeul Raionului Olteniţa. Sibiu.

Niţu А. 1969. Reprezentări antropomorfe pe ceramica de tip Gumelniţa A. Danubius II – III, p. 21–43.

Opriș V., Ignat T. & Lazăr C. 2017. Human-shaped pottery from the tell settlement of Sultana-Malu Roşu. H. Schwarzberg and V. Becker (eds.) Bodies of Clay. On Prehistoric Humanised Pottery. Proceedings of the Session at the 19th EAA Annual Meeting at Pilsen, 5th September 2013, p. 191–212.

Rosetti D. V. 1939. Steinkupferzeitliche Plastik aus einen Wohnhügel bei Bukarest. JPEK, XII, p. 29–50.

Schwarzberg H. 2011. Durch menschliche Kunst und Gedanken gemacht: Studien zur anthropomorphen Gefäßkeramik des 7. bis 5. vorchristlichen Jahrtausends. Münchner Archäologische Forschungen Band 1.

Voinea V. 2005. Ceramica complexului cultural Gumelniţa – Karanovo VI. Fazele A1 şi A2. Ex Ponto.

Георгиева П. 2018. Социално-икономически промени през късния енеолит в района на културите Варна, Коджадермен–Гумелница–Караново VI и Криводол–Сълкуца. Studia Archaeologica Universitatis Serdicensis, 6, p. 101–151.

Иванов Т. 1981. Два култови съда от Разградско. Изкуство, № 9–10, p. 71–73.

Иванов Т. 1984a. Радинград. Селищна могила и некропол (V – IV хил. пр. н. е.). София: Печатна база „Офсетграфик”.

Иванов Т. 1984б. Многослойное поселение у с. Радинград Разградского района. Studia praehistorica, VII, p. 81–98.

Калчев П. 2010. Неолитни жилища Стара Загора. Каталог на експозицията.

Карайотов И. 1986а. Праисторически идоли от Руен. в. Черноморски фронт (Бургас), ХXXXIII, N 13483, 11 юни 1986, p. 4.

Карайотов И. 1986б. Праисторически надпис от Руен. в. Черноморски фронт (Бургас), ХLIII, N 13525, 30 юли 1986.

Карайотов И. 1986в. Праисторически надпис в Руен. в. Камчия (Руен), N 15, 20 окт. 1986, p. 4.

Карайотов И. 1993а. Старини по пътя на солта. сп. Море (Бургас), I, N 8 и 9, p. 14–18.

Карайотов И. 1993б. Селищните могили по долината на р. Хаджийска. в. Бургас днес и утре, I, N 124, 28 юли 1993.

Миков В. 1933. Селищна могила в с. Габарево (Казанлъшки окръг). Годишник на Народния музей, V, p. 83–114.

Николов В. 2006. Култура и изкуство на праисторическа Тракия. Пловдив.

Николов В. 2011. Праистория на българските земи. Българска национална история. Том I. Българските земи през древността. В. Търново, p. 13–310.

Райчевски С. 2007. Крайбрежна Стара планина. Топоними и хидроними. София.

Тодорова Х. 1986. Каменно-медната епоха в България. Пето хилядолетие преди новата ера. София.

1 Mounts Eminska and Aitoska are separate parts of the Eastern Balkan Mountains range.

2 Presented by Anton Niţu more than 50 years ago, the classification of the Gumelniţa anthropomorphic vessels and lids is still largely valid to this day (Niţu, 1969). It has been adopted in a number of later studies (for example, see Andreescu, 2002, p. 72–80; Voinea, 2005, p. 64).

3 The vessel was found in a dwelling studied in the space beyond the settlement mound. Along with it, there was a large number of other vessels, which researchers think are part of one set used in feasts. For more information about the context of the finding, see: Hansen et al., 2017; Brummack, Karaucak, 2019.