Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2022, vol. 23, pp. 88–106 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2022.23.5

Cow, Bull, Woman, Man (Relief on a Vessel from the End of the Fifth Millennium BC from the Western Black Sea Coast)

Petya Georgieva

Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski”

pggeorgiev@uni-sofia.bg

Abstract. In the Varna Eneolithic necropolis three gold applications were found with shapes presenting cattle in profile. They have no clear sexual characteristics. These figures are usually interpreted as bulls. Images with analogous shapes occur rarely on ceramic vessels as well.

This paper presents a vessel from the settlement mound Kozareva Mogila (Bulgaria). Two anthropomorphic and two zoomorphic figures are depicted on it. The images are schematic, modeled in relief along the entire middle part, arranged in a horizontal belt and alternating anthropomorphic and zoomorphic. The anthropomorphic ones are presented facing the observer, differing from each other only in that one has embossed female breasts. The zoomorphic ones are presented in profile. In shape they are very close to the gold cattle figures from Varna. Like the human figures, one has a clearly marked sex: a phallus in relief. This indicates that one depicts a bull and the other a cow, a rare example of simultaneous presentation of female and male anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images with clearly marked sex. This scene is a key to identifying the gender of the gold zoomorphic figures from the Varna necropolis, commonly called bulls.

Keywords: gender in prehistory, gold, Varna Eneolithic necropolis, late Eneolithic, prehistory of the Balkans.

Karvė, jautis, moteris, vyras

Anotacija. Varnos eneolito nekropolyje buvo rastos trys auksinės galvijų formos plokštelės. Nors jos neturi aiškių lytinių požymių, galvijų figūros dažniausiai interpretuojamos kaip jaučiai. Panašių formų vaizdai gana retai pasitaiko ir ant keraminių indų. Straipsnyje pristatomas indas iš Kozareva Mogila (Bulgarija) gyvenvietės. Ant jo pavaizduotos dvi antropomorfinės ir dvi zoomorfinės figūros. Atvaizdai schemiški, reljefiški, išdėstyti horizontalia juosta aplink puodo vidurinę dalį. Antropomorfinės ir zoomorfinės figūros sudėliotos pakaitomis. Antropomorfinės figūros vaizduojamos pasisukusios veidu į stebėtoją. Tarpusavyje jos skiriasi tik tuo, kad ant vienos iš jų yra įspaustos moteriškos krūtys. O zoomorfinės figūros vaizduojamos profiliu. Savo forma jos labai panašios į Varnoje aptiktas auksines galvijų figūrėles. Viena iš jų, kaip ir žmonių figūrėlės, turi aiškiai išreikštą lytį – reljefinį falą. Tai rodytų, kad viena iš figūrėlių vaizduoja jautį, o kita – karvę, o tai yra retas atvejis, kai vienu metu kuriami moteriškieji ir vyriškieji antropomorfiniai bei zoomorfiniai atvaizdai, kurių lytis aiškiai išreikšta. Ši scena yra raktas nustatant Varnos nekropolio auksinių zoomorfinių figūrų, paprastai vadinamų jaučiais, lytį.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: lytis priešistorėje, auksas, Varnos eneolito nekropolis, vėlyvasis eneolitas, Balkanų priešistorė.

____________

Acknowledgements. I thank Dr. Veselin Danov for his efforts to collect the pieces of the vessel published here, as well as the restorer Svetlozar Lisichkov. I thank Prof. Rabadzhiev, a specialist in classical archaeology, for the fruitful discussions.

Received: 10/11/2022. Accepted: 05/12/2022

Copyright © 2022 Petya Georgieva. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Maria Gimbutas has made contributions in two main directions in the study of the prehistory of Europe and these are the two sections of the conference dedicated to her. Some of her ideas have been criticized, sometimes fairly, sometimes unfairly, as are most interpretations of prehistory. Her enormous contribution to archaeology, which does not depend on nuances in interpretations, is the popularization of the prehistory of Europe. This contribution is not limited to the quantity and volume of books, but to how much people read them. Here is an illustration of this. My family and I were visiting a friend’s mother at a resort in North Carolina. The hostess, Rebecca McEnally, an economist by profession, a university teacher, now retired, was very kind and asked everyone about our activities. I found out that she knew a lot about the prehistory of Europe and especially about the prehistory of Bulgaria, and I was impressed. All her relatives were economists or IT professionals. I asked her how she knew all this and the answer was “From Maria Gimbutas’s book on the Mother Goddess, I have it.” She didn’t know Maria Gimbutas personally, she didn’t go on a trip to Southeast Europe to be impressed by some museum, but she just came across the book, read it and learned an impressive amount of things. This is an excellent attestation for the work of Maria Gimbutas. No matter how much prehistorians’ ideas about the number of steppe invasions or the interpretations of Neolithic and Eneolithic anthropomorphic figurines of southeastern Europe may change, her books will remain as a wonderful, interesting study, in which many facts about prehistory of Europe have been collected, which will always command respect.

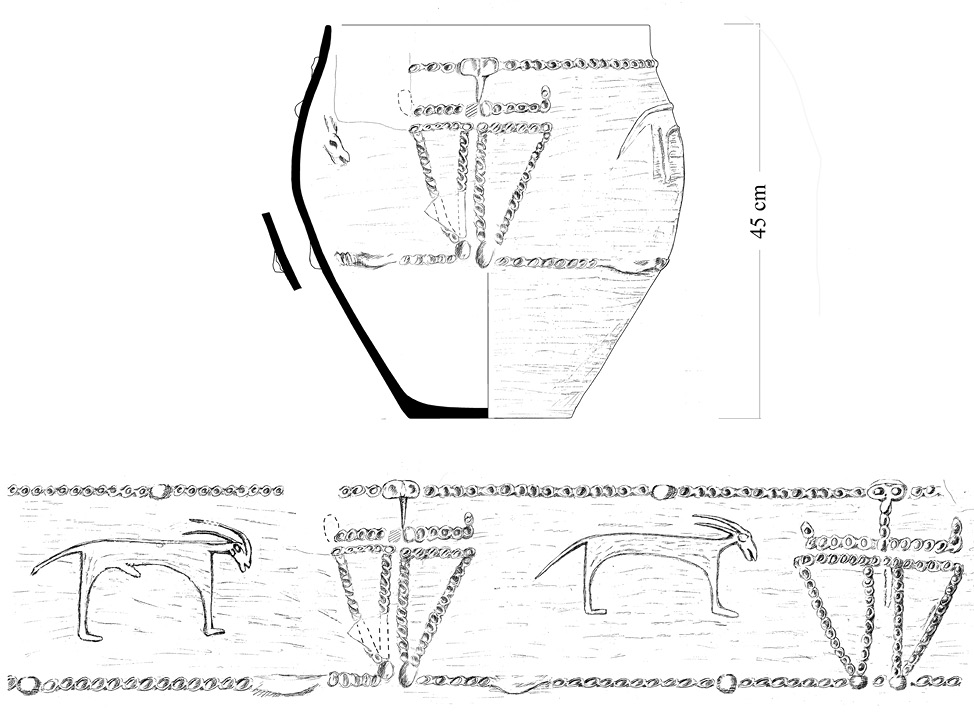

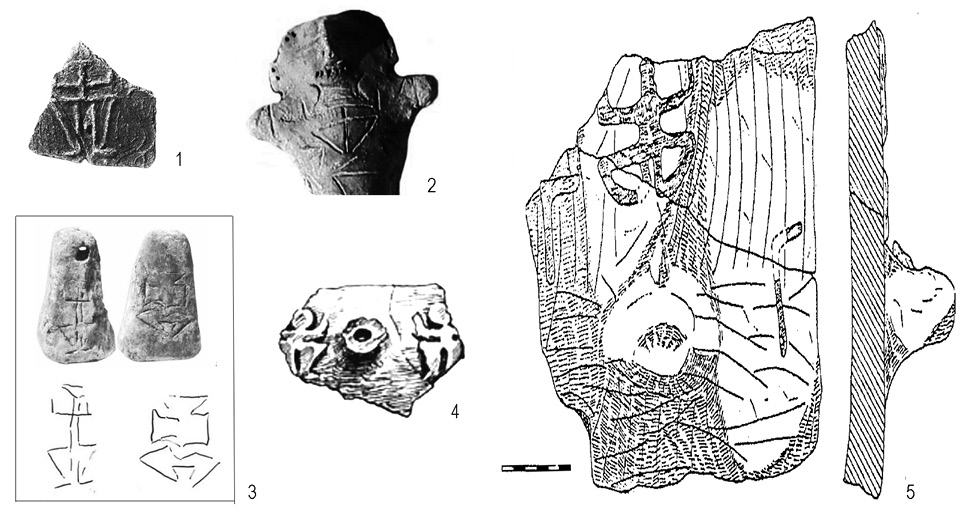

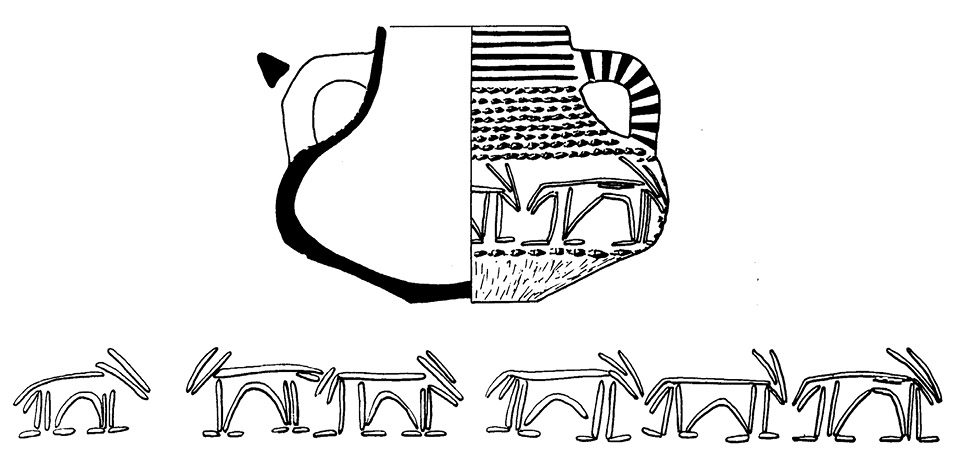

For the event dedicated to Maria Gimbutas, I chose to present a very interesting new find, which allows for a different interpretation of some of the zoomorphic images from the Eneolithic and especially the most famous among them, the appliqués in the form of “bulls” from the Varna Necropolis. It is a large vessel, 45 cm high, with a maximum diameter of 45 cm, decorated with relief executed anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures with clearly marked gender: female and male, cow and bull (Fig. 1). It was found in a settlement mound in a burned Late Eneolithic settlement and was badly deformed by the high temperature. Its restoration was difficult, but still successful. The photos presented here are from different stages of restoration (Fig. 2, 3).

Fig. 1. A vessel decorated with relief anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures from Kozareva Mogila (drawing by P. Georgieva).

1 pav. Indas iš Kozareva Mogila, papuoštas reljefinėmis antropomorfinėmis ir zoomorfinėmis figūromis (P. Georgievos pieš.)

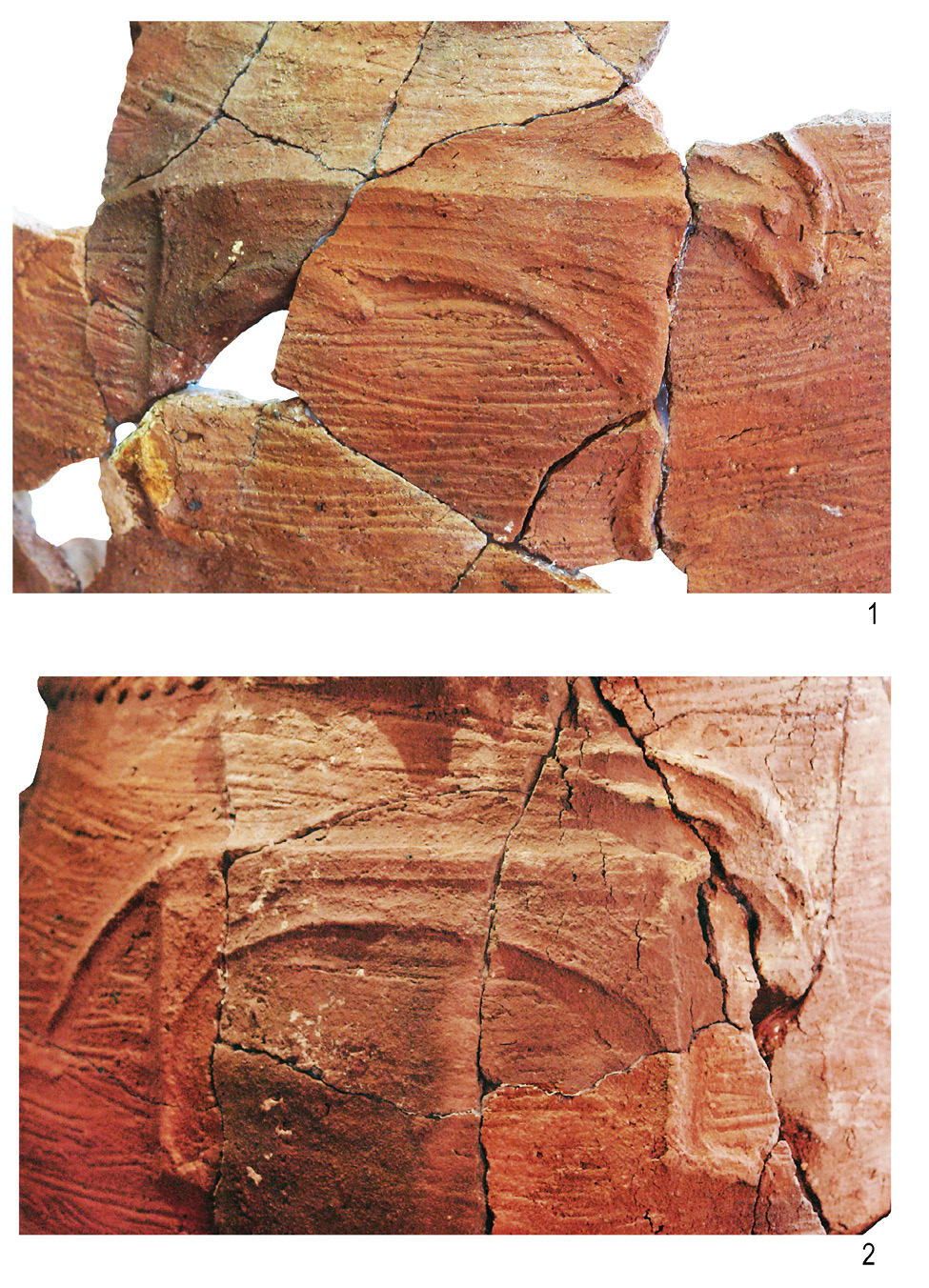

Fig. 2. First stage of the restoration of a vessel decorated with relief anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures from Kozareva Mogila (photos by P. Georgieva).

2 pav. Pirmasis indo iš Kozareva Mogila, puošto reljefinėmis antropomorfinėmis ir zoomorfinėmis figūromis, restauravimo etapas (P. Georgievos nuotraukos)

Fig. 3. Second stage of the restoration of a vessel decorated with relief anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures from Kozareva Mogila (photos by P. Georgieva).

3 pav. Antrasis indo iš Kozareva Mogila, puošto reljefinėmis antropomorfinėmis ir zoomorfinėmis figūromis, restauravimo etapas (P. Georgievos nuotraukos)

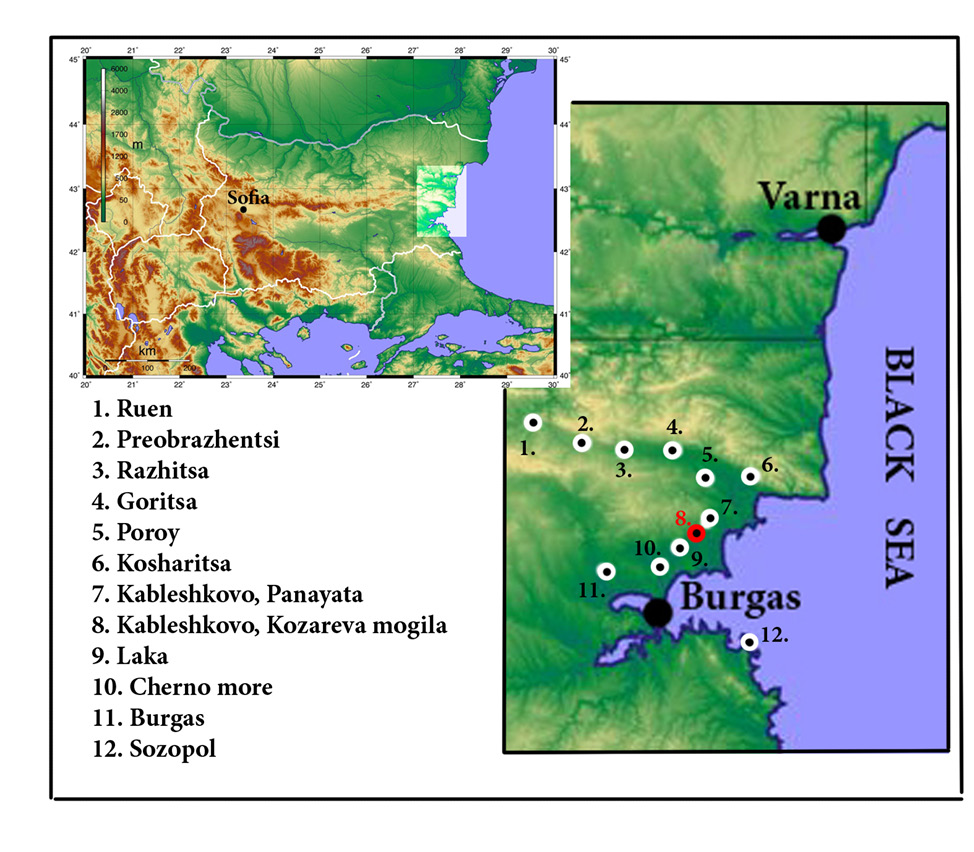

Discovery context. The Kozareva Mogila site is located in the Western Black Sea region, south of Stara Planina, about 4.5–5 km in a straight line from the modern Black Sea coast (Fig. 4). Administratively, it is in the territory of the town of Kableshkovo, Burgas region. It is a settlement mound from the Eneolithic (Georgieva, 1998; Georgieva, P. / Popova, M. / Danov, V., 2018). The necropolis was also discovered and is being explored (Georgieva, 2012; Georgieva, Danov, 2021). The vessel I present here was found in a late Eneolithic burnt horizon building, which chronologically refers to the final phase III of the Kodjadermen-Gumelnita-Karanovo VI (Георгиева, 2003) culture, at the end of the fifth millennium BC (calibrated dates). In the southern part of the mound, this horizon has been disturbed in many places by later excavations, Hellenistic-era construction and treasure hunters’ pits, but in the northern part it is relatively better preserved. Several buildings and parts of buildings have been explored from it. The four buildings that are better preserved have two floors each. Probably most of them were like that, since the debris everywhere are very massive, reaching up to 1 m in thickness. Two potter’s kilns full of vessels were found (Георгиева, 2010; Georgieva, 2019). Everywhere among the debris there are many vessels: small, medium and large. Among them there are those that are not finished. Also found are tools for making pottery, pieces of kneaded clay for making vessels, dozens of ceramic loom weights and other small objects, such as anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines, ornaments, stone tools, flint, bone and horn, mostly deformed from the fire. From the established situation, it can be concluded that this was a large pottery workshop, destroyed by a fire that occurred during the firing of ceramics. Other interesting and somewhat unusual finds from this horizon are the artifacts made from pieces of human skulls, the so-called skull roundels. They have been known for a long time from other sites from different eras, but for the first time in this settlement there are so many (Georgieva, / Russeva, 2016).

Fig. 4. Location of the Kozareva Mogila site and its contemporary nearby sites (author V. Danov).

4 pav. Kozareva Mogila lokacija ir kitos dabartinės netoliese esančios gyvenvietės (autorius V. Danovas)

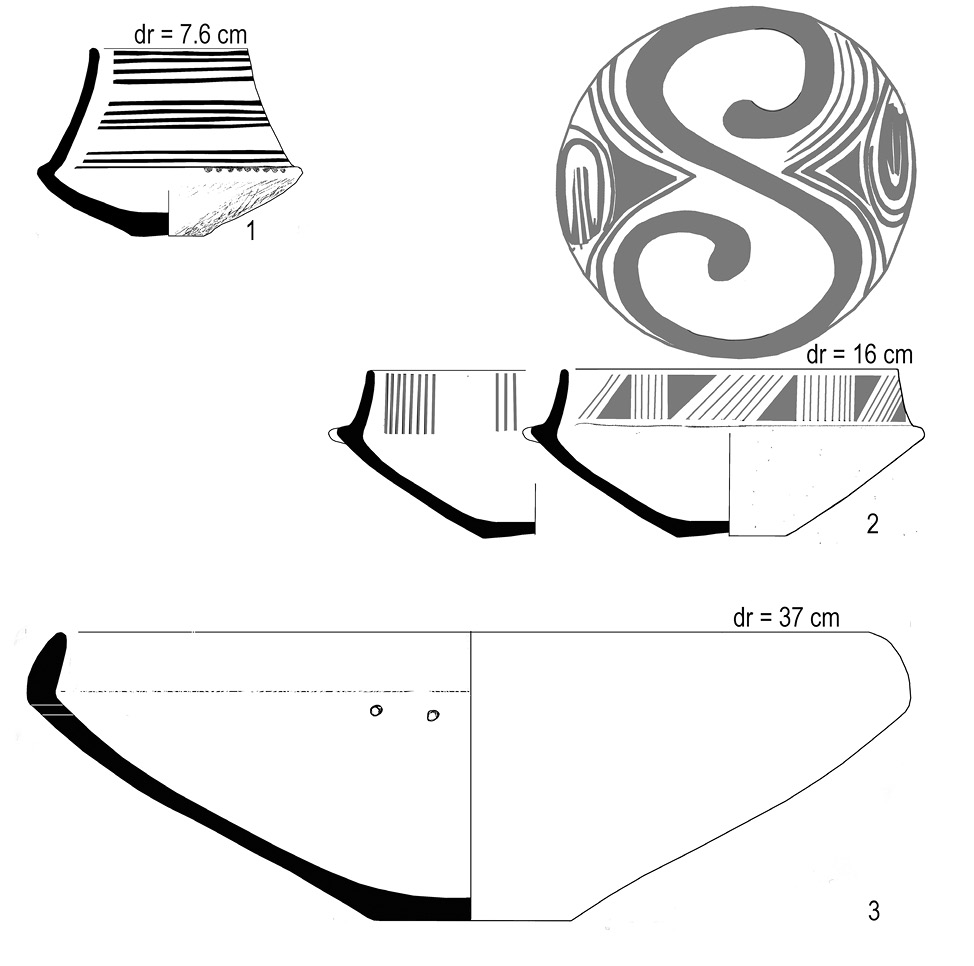

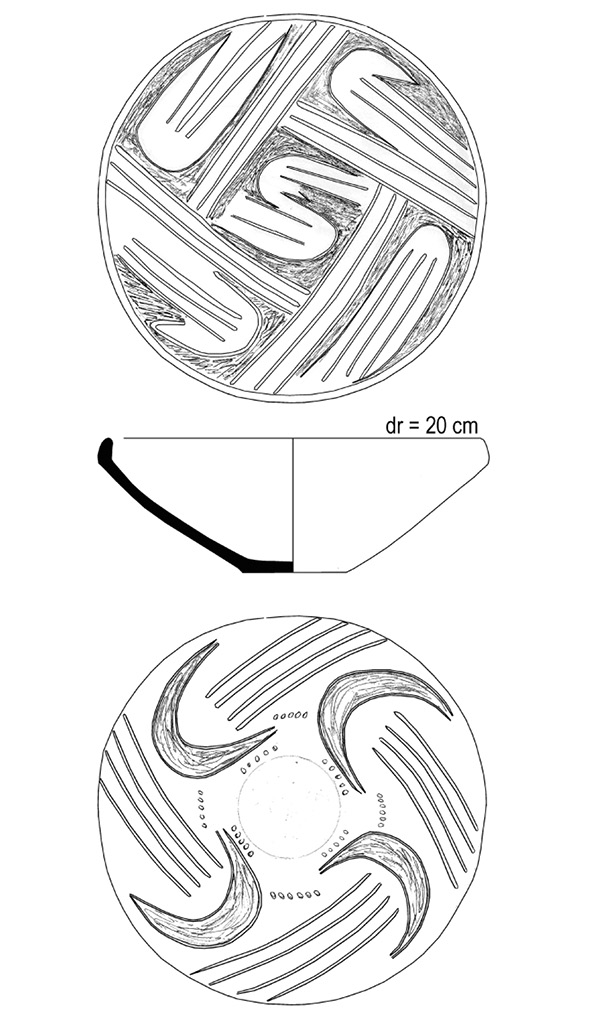

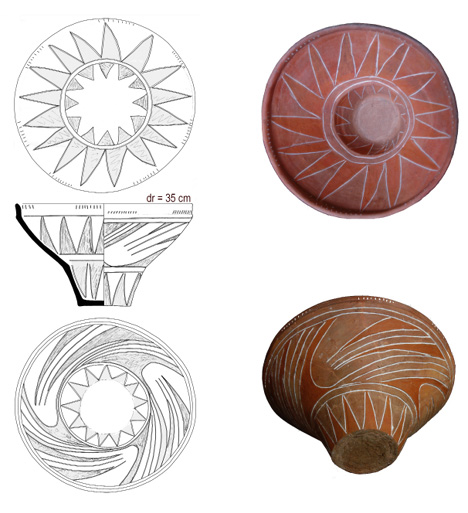

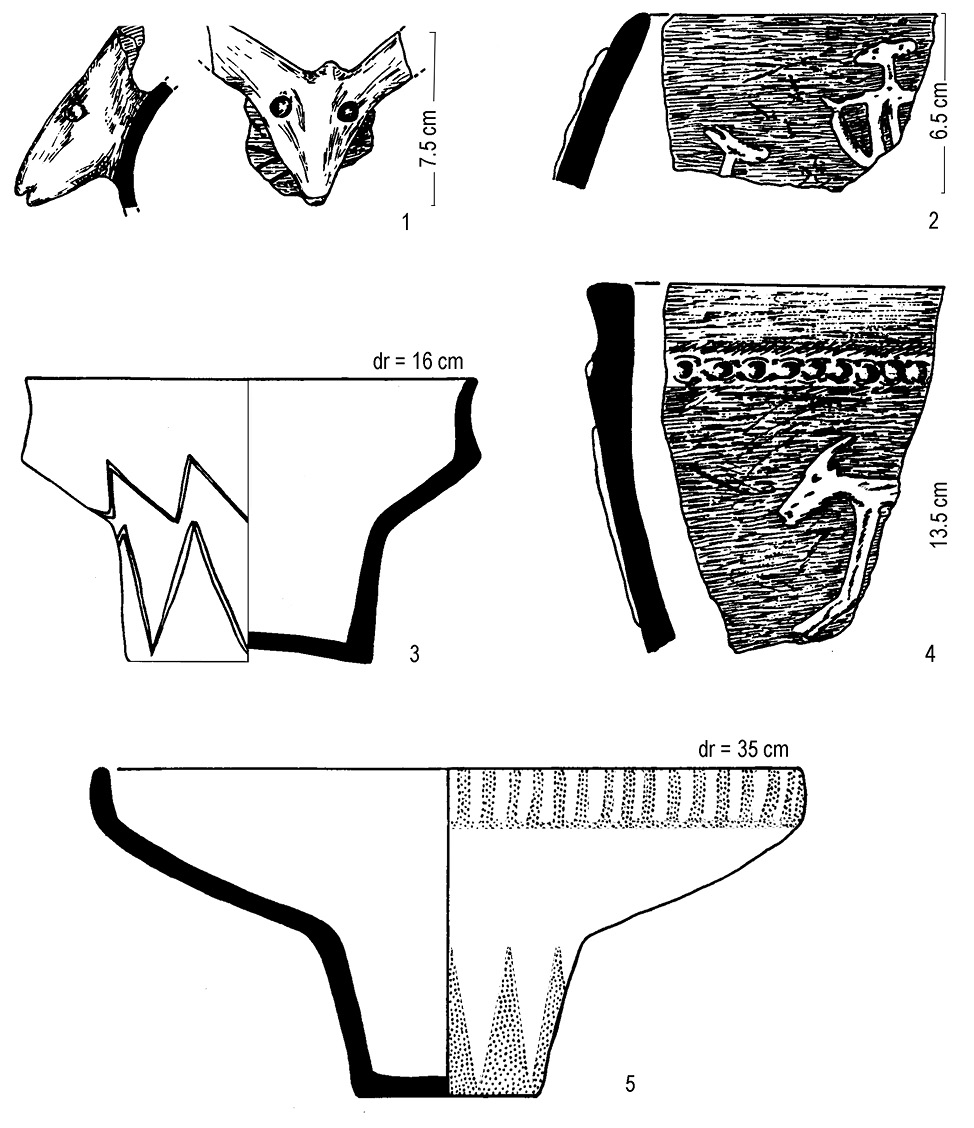

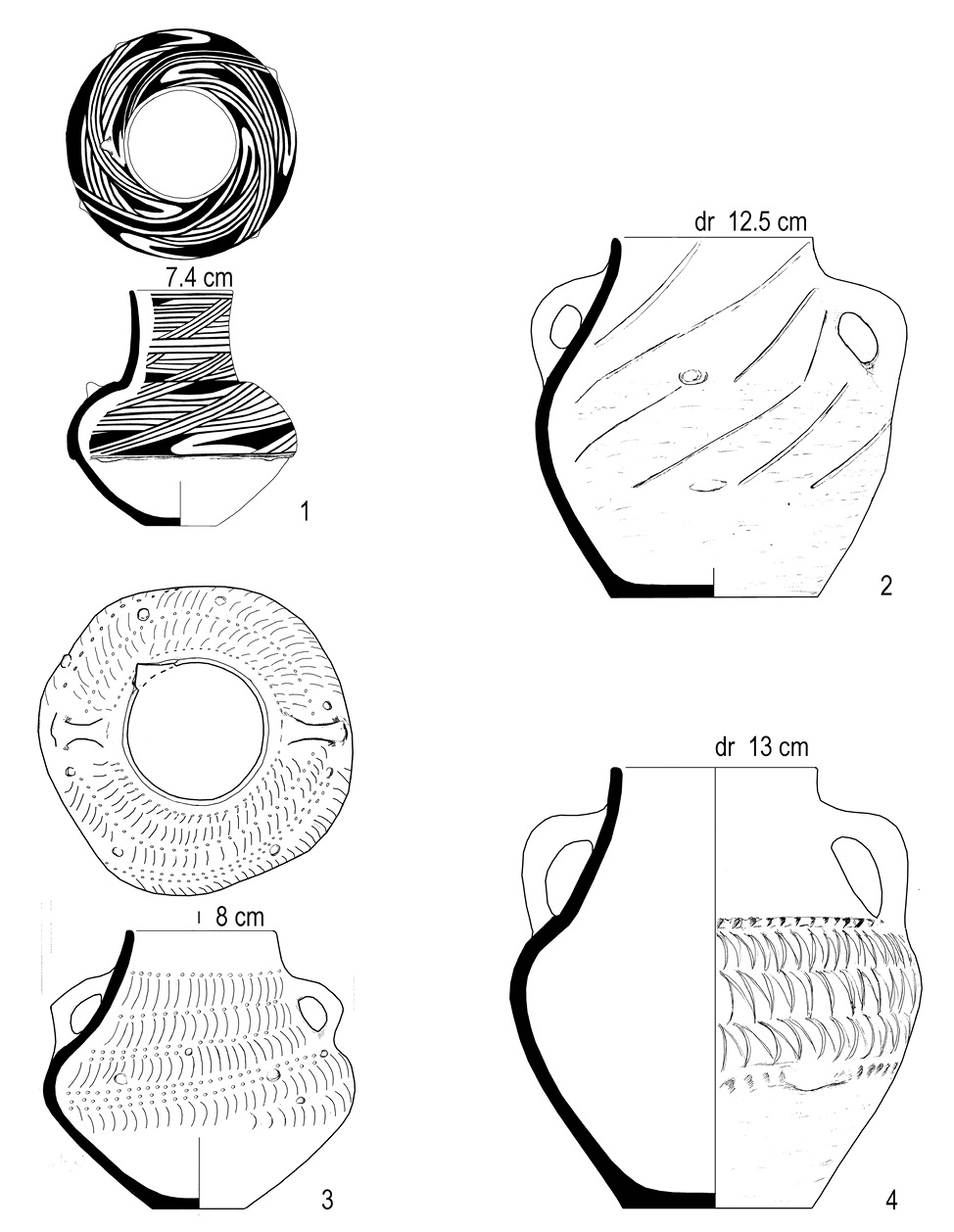

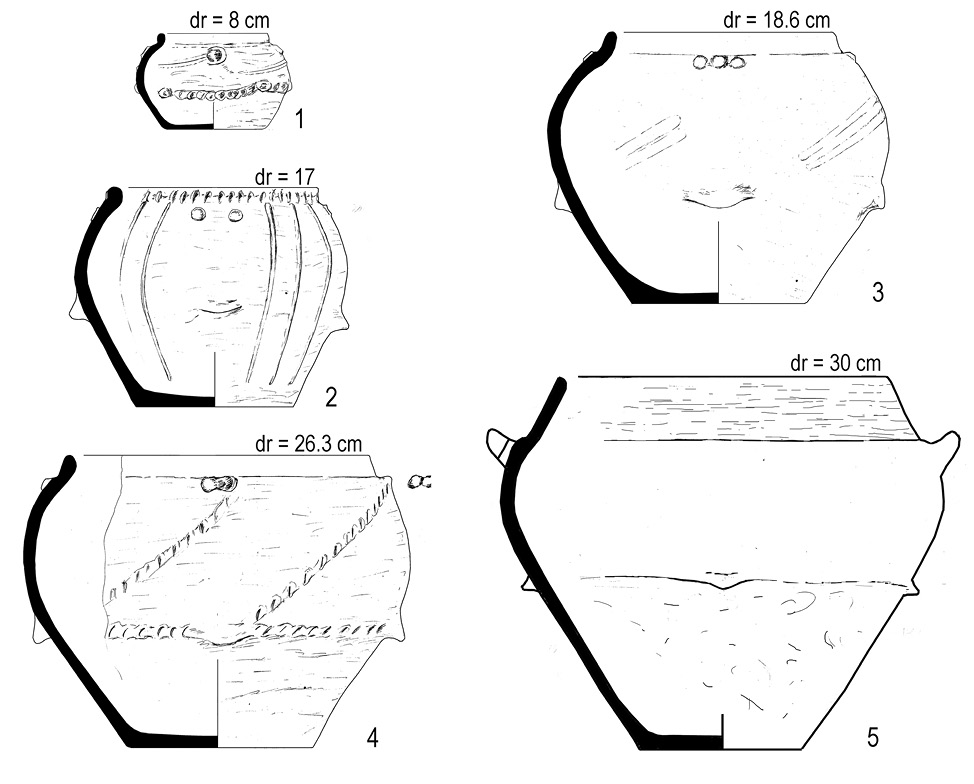

As an illustration of the relative chronology of this horizon, I present a few vessels from building 4 (Fig. 5–7, 9.10). The large dishes are of the same type, with no variants in the sill profiles (Fig. 5: 3). Their diameters are between 30 and 45 cm. They are rarely decorated with graphite on the inside and the upper part of the sill on the outside. There are few, richly ornamented smaller dishes like the one shown in the illustration (Fig. 5: 2). They are usually single instances or 2–3 for the whole settlement. With them, the variety of forms is greater. They are often ornamented inside and out, with the decoration distributed in several ornamental fields. Besides decoration painted with graphite, decoration incised and inlaid with white paint or with white and red paint is also found. There are few such vessels. The ornaments are outlined with incised lines and filled from the inside with scratches that served to fix the paint (Figs. 6, 7). This technique of ornamentation is not characteristic of the third phase of the Kodjadermen-Gumelnita-Karanovo VI culture, but it is typical of the Varna culture. The large bowl with a narrow and deep lower part is an interesting example in this respect (Fig. 7). Vessels with this shape are relatively few, but they are typical of the late Eneolithic. They seem to have a more special purpose than the others, because in addition to their strange shape, they also have a specific ornamentation. The bowl from Kozareva Mogila is ornamented with incised lines inlaid with white and outlining triangles covered with red paint. Seen both from the inside and outside, the vessel looks like a sun or a large flower. Two other vessels of the same type from the region of Thrace, from the settlement mound near Starozagorski Mineralni Bani, from the latest burned horizon of the Eneolithic, representing the final phase III of the Kodjadermen-Gumelnita-Karanovo VI culture, have similar ornamentation, but applied only with incised lines (Fig. 8: 3) or with red pastose paint (Fig. 8: 5). There are some fine deep high-necked graphite-ornamented vessels (Fig. 9: 1) and small biconical cups (Fig. 5: 1). They are few in number but not unusual for the period. Deep vessels with two vertical handles on the neck are taken as the most indicative for recognizing the end of phase III of the Late Eneolithic (Fig. 9: 2–4). They are numerous and of great variety in size. The decoration applied to the most prominent part and the lower part of the neck is in relief and coarsening (rows with impressions of a shell, nail, blade, relief ribs, etc.). There are also combinations of this type of decoration and graffiti painted on the upper part of the neck. A vessel from the latest burnt horizon from the Eneolithic of the settlement near Starozagorski Mineralni Bani has a similar shape (Fig. 14). The most numerous are the pots covered with barbotine, relief ribs and buds (Fig. 10: 1–4). Their inner surfaces and the outer part of the short necks are perfectly smoothed and polished. They range in size from tiny to very large. The largest ones have a height and a maximum diameter of approximately 90 cm. So far, two large storage vessels have been found in the burnt horizon, with a roughened with barbotine surface, decorated with relief bands depicting zoomorphic or anthropomorphic figures. One of them is the vessel that I present here. It was found in the northern part of the mound, in building 4, among large pieces of debris closely piled one upon another. At this place there was some structure built of a clay mixture similar to that of which the walls of the building were made. Here the conflagration reached a very high temperature, and the clay debris in several places were literally melted and turned into a vitrified porous mass. After part of the vessel was removed as ceramic fragments, one of them was observed to have a relief image of an animal head, and so began its purposeful collection and search for additional fragments , remaining in the field. It was found next to the central profile and this was an additional difficulty as we had reached a depth of almost 2 m. Thanks to the efforts of colleague Veselin Danov, almost all the pieces were collected. Some of them were glazed and severely deformed by the secondary firing during the conflagration. First, the fragments on which the zoomorphic figures are arranged were collected. One figure was observed to have a phallus and the other not, and therefore one was male and the other female. Despite the many deformations on the fragments, the restoration began. The deformations were so great that I only noticed the anthropomorphic figures after I started drawing the vessel. Not even the restorer had seen them.

Fig. 5. Vessels from building 4, Kozareva Mogila (drawing by P. Georgieva).

5 pav. Indai iš pastato Nr. 4, Kozareva Mogila (P. Georgievos pieš.)

Fig. 6. Dish with incised and scratched decoration, inlaid with white paint from building 4, Kozareva Mogila (drawing by P. Georgieva).

6 pav. Indas su įpjautais ir įrėžtais ornamentais, dekoruotas baltais dažais, iš pastato Nr. 4, Kozareva Mogila (P. Georgievos pieš.)

Fig. 7. Bowl with incised and scratched decoration, colored with white and red paint from building 4, Kozareva Mogila (drawing and photos by P. Georgieva).

7 pav. Dubuo su įpjautais ir įrėžtais ornamentais, dažytas baltais ir raudonais dažais, iš pastato Nr. 4, Kozareva Mogila (P. Georgievos piešinys ir nuotraukos)

Fig. 8. Vessels and fragments of vessels with incised decoration from the settlement mound near Starozagorski Mineralni Bani Mogila (drawing by P. Georgieva).

8 pav. Indai ir indų fragmentai su įrėžtais ornamentais iš gyvenvietės kalvoje prie Starozagorski Mineralni Bani Mogila (P. Georgievos pieš.)

Fig. 9. Vessels from building 4, Kozareva Mogila (drawing by P. Georgieva).

9 pav. Indai iš pastato Nr. 4, Kozareva Mogila (P. Georgievos pieš.)

Fig. 10. Vessels from building 4, Kozareva Mogila (drawing by P. Georgieva).

10 pav. Indai iš pastato Nr. 4, Kozareva Mogila (P. Georgievos pieš.)

The vessel with the relief decoration with anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures. Its shape is elliptical. The lower part is a truncated cone, the transition to the upper part is smooth, the shoulders are slightly bulging and smoothly transition into a low wide neck. The neck is clearly distinguished from the shoulders by the way the outer surface is treated. The surface of the entire vessel is covered with a slick of clay with minute impurities. The entire inner surface and a broad strip below the mouth are well polished. Most of the outer surface is roughened and decorated with barbotine, relief bands and relief buds. In terms of shape, size, proportions and surface treatment, the vessel does not differ from other similar ones, which we usually call pythoi or repositories, or storage vessel. The interesting thing about it is the relief decoration. It is presented in a frieze, with a height of 23.5 cm, bordered below and above with horizontally glued relief strips, incised with a finger. It is the most prominent and visible part of the vessel. Four figures are depicted in this ornamental field, two zoomorphic and two anthropomorphic. The anthropomorphic ones are represented frontally and the zoomorphic ones in profile. They are arranged next to each other at small distances with alternation – anthropomorphic, zoomorphic, anthropomorphic, zoomorphic. The anthropomorphic ones are significantly higher than the zoomorphic ones. They are presented very schematically, all in the same manner. Their height is 24 cm or 0.5 cm more than the height of the frieze. Their heads and feet rest on the relief bands bordering the field and appear to be part of them. The heads are short horizontally elongated buds. Two dimples are formed on them by pressing, in the middle of which there is a bulge. This is how the two sides of the face and the nose are depicted. From the middle of the heads protrude the necks, represented by relief bands. They are different. In one figure the neck is thinner and slightly pointed downwards, and in the other it is slightly thicker and incised in relief with a finger. In both figures the incised bands represent the shoulders, arms and legs. The shoulders and arms are horizontal bands, on either side of which two short vertical bands extend upwards. There is no torso. On the figure with the thinner neck, two buds depicting breasts were affixed to the horizontal band. One is broken. The other has no breasts. Below the shoulder and arm bands on both figures, a second horizontal band is of approximately the same size. It marks the upper parts of the legs and pelvis. The legs are represented by two right-angled triangles with a small distance between them. They end at the bottom with relief buds that can be associated with feet. In the figure, which has a thinner neck and no breasts, a short very slightly convex line can be seen at the top between the legs, which could be taken as a phallus, but this is not certain. It could also be a random effect of the roughening of the surface. The differences between the two figures, expressed in the presence and absence of breasts and the way the necks are presented, give reason to assume that one depicts a female and the other a male.

Fig. 11. The anthropomorphic figures from the decoration of the vessel from Kozareva Mogila (photos by P. Georgieva).

Fig. 11. The anthropomorphic figures from the decoration of the vessel from Kozareva Mogila (photos by P. Georgieva).

11 pav. Antropomorfinės figūros iš Kozareva Mogila indo dekoro (P. Georgievos nuotraukos)

Anthropomorphic relief images on ceramic vessels have existed since the Neolithic. In the three-dimensional anthropomorphic plastic art, whose instances are significantly more numerous than the images on vessels, different iconographic images are recognized, which probably represent different characters from mythology or the everyday life of society. For the Krivodol–Salkuta and Kodjadermen-Gumelnita-Karanovo VI cultures, such are, for example: a pregnant woman wearing a long dress with vertical stripes, appearing as a rattle or an anthropomorphic vessel with outstretched arms (Чохаджиев, 2005; Georgieva, Milanov, 2005), a man with a hump or backpack/load on the back (Перничева, 2004, с. 452–453, 460, 462; Chapman, 2020; Müller, 2015; Радунчева,1974; Радунчева, Холевич, 2001; Stavreva, 2022, see in this edition), a woman with long deformed snake-like arms (Радунчева, Холевич, 2000; Georgieva, 2012) etc. Relief images on vessels are significantly fewer, more schematic, but with them different iconographic schemes and poses can also be distinguished, which probably also correspond to different images or characters. What is specific in this case are the triangles that represent the legs and torso and the arms spread to the side and raised from the elbows up. There are similar images from the early Neolithic period from Karanovo, Zagortsi, Azmashka Mogila, Stara Zagora–Okrazhna Bolnitsa, etc. (Николов, 2006, с. 61–66). They have one arm raised up and the other pointing down, which distinguishes them from the later ones. Exact analogies from the Late Eneolithic are not many, and probably one of the reasons for this is that such reliefs are very difficult to recognize on fragments. The figurines from Hotnitsa (Чохаджиев, 2004, с. 418, обр. 1.9; Миткова, 2005, с. 204, обр. 4) and Vitanesti (Andreescu, 2002, Pl. 60.1) are closest to the figures from Kozareva Mogila. They were found on fragments of vessels and a loom weight (sample 12) (Chokhadzhiev, 2004, 418, sample 1.9; Mitkova, 2005, 204, sample 4). In two of the finds from Hotnica, there are two figurines, probably, also of different sexes. An image similar in general characteristics is also found on the chest of an anthropomorphic figure from Lovets (Fig. 12: 4). Similar is the figurine with hands on which three fingers are marked, from Vaksevo–Studena Voda (Чохаджиев, 2001, 175, рис. 93). There are other such finds, all from Late Eneolithic settlements, but preserved to a lesser extent (Berciu, 1961, 329, Fig. 150.4; Petrescu-Dâmboviţa, 1953, 583, fig. 8: 10; Stîngă 1988, 38, Fig. 6; Терзийска-Игнатова, 2000, обр. 2,7; Чохаджиев, 2004, обр. 1,5; Hansen et al., 2012, 33, Abb. 40; Radu, 2002, 352, Pl. 100.2; Pătroi 2015, 398, Fig. 365.1). The listed analogies prove that the representation scheme of the anthropomorphic figures is reproducible and it is a specific recognizable image, or rather images, of male and female sex.

Fig. 12. The anthropomorphic figures from the decoration of: vessels (1, 4) and weight for a weaving loom (3) from the Hotnitsa settlement mound (after: Чохаджиев, 2004, обр. 1.9; Миткова, 2005, обр. 4); 5 Vitanesti settlement mound (after: Andreescu, 2002, pl. 60,1); anthropomorphic figurine (3) from Lovetc (after Миткова, 2007, обр. 2).

Fig. 12. The anthropomorphic figures from the decoration of: vessels (1, 4) and weight for a weaving loom (3) from the Hotnitsa settlement mound (after: Чохаджиев, 2004, обр. 1.9; Миткова, 2005, обр. 4); 5 Vitanesti settlement mound (after: Andreescu, 2002, pl. 60,1); anthropomorphic figurine (3) from Lovetc (after Миткова, 2007, обр. 2).

12 pav. Antropomorfinės figūros iš: indų (1, 4) ir audimo staklių svarelis (3) iš Hotnitsa gyvenvietės (pagal: Чохаджиев, 2004, обр. 1.9; Миткова, 2005, обр. 4); 5 Vitanesti gyvenvietės (pagal Andreescu, 2002, pl. 60,1); antropomorfinė figūrėlė (3) iš Lovetc (pagal Миткова, 2007, обр. 2)

The two zoomorphic figures are as wide as the anthropomorphic figures, but their height is considerably less. They are located between the anthropomorphic ones, their upper parts being approximately at the level of the shoulder and arm lines of the anthropomorphic ones. They depict horned animals with long, drooping tails. They are outlined with relief ribs without notches (Fig. 13). The ribs are connected and enclose a space that is slightly raised above the surrounding surface of the vessel. This creates the feeling of a separate application, as if the figures were made independently and then glued. This is a significant difference with the anthropomorphic ones, in which the individual elements of the body are represented independently, even without a direct connection – head and neck, arms and chest and two right triangles for the pelvis and legs. Even the heads and steps appear to be part of the molding of the bands bounding the frieze. They are presented schematically in profile, and both figures follow the same scheme. The upper body is close to a straight line that turns about 45 degrees down for the tail and slightly up for the neck. The head is an extension of the neck with an extended downward muzzle. It has a bulging eye in relief and two long horns that curve backward over the back. In both figures the mouth is open. The lower part of the body and the inner part of the legs are outlined with a single arcuate line. Here is the only significant difference between the two figures. One has a clearly defined phallus on the arcuate line near the hind legs, and the other does not. The lines delineating the legs on the outer sides are straight and connect with the lines of the tail and neck. Two legs are visible – front and back. They end with feet, as in a human, conveyed with horizontal relief convex lines, slightly tapering in the front.

Fig. 13. The zoomorphic figures from the decoration of the vessel from Kozareva Mogila (photos by P. Georgieva).

Fig. 13. The zoomorphic figures from the decoration of the vessel from Kozareva Mogila (photos by P. Georgieva).

13 pav. Antropomorfinės figūros iš Kozareva Mogila indo dekoro (P. Georgievos nuotraukos)

The general impression is that they are cattle, because of the long tails hanging back. One of them should be a bull and the other a cow. The described scheme of representation of zoomorphic figures occurs in two objects. The gold zoomorphic appliqués from grave 36 of the Varna Eneolithic necropolis (Fig. 14) are of a similar shape. There are two of them – a small and a large one. They have no genital markings. They differ slightly from the figures from Kozareva Mogila in general proportions. The gold ones are higher. Also, their horns are more curved and their tails are longer. The feet are also horizontally placed, but are forked in front. And with the gold ones as well, on the head there is one embossed protruding eye and the mouth is open. Besides the figures from grave 36, there is another small gold figure from grave 26 (Fig. 14: 3). Its shape is slightly different – the lower part of the body is not arched. In the first publication of the excavator Ivan Ivanov, the three appliqués were called zoomorphic figurines (Иванов, 1978: 9), while in the articles published a year earlier by Maria Gimbutas, they were bulls (Gimbutas 1977a, 48, 49; 1977b).

Fig. 14. Gold zoomorphic figurines from grave 36 (1, 2) and grave 26 (3) of the Varna necropolis (photos of Varna museum).

14 pav. Auksinės zoomorfinės figūrėlės iš Varnos nekropolio kapo Nr. 36 (1, 2) ir Nr. 26 (3) (Varnos muziejaus nuotraukos)

Another exact analogy of the zoomorphic figures from the vessel from Kozareva Mogila is the decoration of a vessel from a settlement from the final stage of the Late Eneolithic near Starozagorski Mineralni Bani (Fig. 15). A total of six figures are represented on the middle part of the vessel. Their sizes are the same. Five of them are turned to the right, one to the left. Unlike the figures from Kozareva Mogila, these are drawn with incised lines. The feet are horizontal, but there are two for the front and two for the hind legs, facing forward and backward. No eyes are marked. The horns are represented in the same way. The mouth is also shown open. In the first publication, these figures are called horned animals, most likely bulls. It has also been noted that in terms of style they do not differ from the golden figures of bulls from Varna (Димитров 2002, 10).

Fig. 15. Vessel from the settlement mound near Starozagorski Mineralni Bani (drawing by P. Georgieva).

15 pav. Indas iš gyvenvietės kalvoje šalia Starozagorski Mineralni Bani (P. Georgievos pieš.)

Recognizing the sex of prehistoric anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images is difficult because they look quite similar and because they are not found whole in most cases. The vessel with the four figures described is a happy exception in this regard. Since the male sex is clearly marked in one of the zoomorphic figures, we can conclude that the other is female. The horns and long hanging tails give reason to interpret the zoomorphic figures as cattle or as a cow and a bull, since they are of the same size. In the anthropomorphic figures, the sex markers are the marked breasts in one figure and the thicker neck with an Adam’s apple in the other. That is, these are a male and a female. In another context, the sex of the same figures, namely the cow and the man, would not be recognized. In this frieze, the presence of two pairs of figures of different sexes helps to make the identification certain and is a key to identifying the sex of analogous figures from other places.

Particularly interesting in this regard are the gold applications from grave 36 of the Varna necropolis. Due to the truly sensational nature of the assemblage, after the first publications of Maria Gimbutas, the label “gold bulls” remained on them. In numerous mentions and comments in the literature, in the catalogs for the various exhibitions in which they were presented, the gold zoomorphic figurines are called bulls, most often without argumentation. Apparently, the fact that they were made of expensive material for Europeans precludes the possibility of depicting cows or simply cattle. In today’s world, calling someone cattle is offensive. It is also offensive to call a woman a cow. But to say of a man that he is like a bull is a compliment. There are also authors who do not commit themselves to determining the sex or even the species, but they are few. For example, Ralf Gleser believes that it is not certain that the vessel images from Starozagorski Mineralni Bani and the gold appliqués from grave 36 are cattle, but rather goats or domestic animals (Gleser, 2019, 187–190).

Very interesting is the analysis of the gold finds from grave contexts made by Ivan Marazov (Маразов, с. 31–34). He also took the zoomorphic figures from the Varna necropolis to be bulls. His analysis is based on parallels from ancient Greek religion and culture. For him, zoomorphic figurines are symbols of herds of bulls and carry an economic and ideological semantic interpretation. In Ancient Greece, herds of bulls were raised for the most prestigious sacrifices to the god Zeus. That is why they are a symbol of wealth and power, a symbol of prestige. On the other hand, the bull is a symbol of the male god and male power. That is, the figurines are taken both as a sacrificial animal intended for the god and as a symbol of the god himself.

The scene from the Kozareva Mogila vessel presented here is reason to reject such interpretations. Since the scheme of depicting the animals from the three sites – Varna, Starozagorski Mineralni Bani and Kozareva Mogila – is the same, it is likely that an animal of the same species is depicted. In this type of images, male animals are recognized by the phallus. In other collective finds of sculpted ceramic figures of cattle, the difference between cows and bulls is marked in the same way – the bulls have a clearly represented genital organ. There are no other differences. One but not the only example of this is the collective find from the Belovode settlement of the Vinca culture, where two bulls and two cows were found together (Šljivar, Jacanović, 2005).

If we assume that the animal from the gold appliqués is a symbol of a god, then it will not be the Bull-God, but the Cow-Goddess. This is not impossible. There are examples of this in the early human religions of the Middle East and North Africa. Such is the Egyptian goddess Hathor, who is the goddess of beauty, love and patroness of the pharaohs. She is depicted as a cow or with horns on which she carries the sun disk. Another example is Ninḫursaĝ, also known as Damgalnuna or Ninmah, was the ancient Sumerian mother goddess of the mountains, also depicted with horns.

If the two gold appliqués from grave 36 depict deities, they should be mother and child or cow and calf, because of the differences in size of similar figures from the same complex. By the same logic, it can be said about the vessel figurines from Starozagorski Mineralni Bani that they do not depict bulls, but cows, in this case a herd of cows.

As I pointed out when describing the vessel scene from Kozareva Mogila, the anthropomorphic figures are significantly larger than the zoomorphic ones. Their feet and heads even extend beyond the frame of the ornamental field. This could mean that they depict characters of a higher rank than those of the zoomorphic figures. It is possible that the bull and the cow are a symbol of the herds of cattle, which were very important to the economy of Eneolithic people. It is possible that they are indeed a symbol of sacrificial animals for the gods from the religious-mythological representations of society at that time. A similar interpretation can be given for the gold cows and calf from grave 36. They symbolize fertility, prosperity and wealth. It is noteworthy that all three sites are from the end of Phase III of the Late Eneolithic. This is the last stage before the collapse of the socio-economic structure that emerged as a result of the development of copper metallurgy. This is a time in which specialized production processes and crafts are born, a time of initial development of trade. It is normal during such a period for cows and bulls, the largest domestic animals, to become symbols of well-being or even to serve to depict some deity.

Conclusion

In the literature on prehistory, often the first published interpretation of an object or artefact is essential to its later perception. Once entered in the literature as gold bulls, the gold zoomorphic figures from the Varna Necropolis continue to march as bulls in most of the subsequent publications in which they are commented on. They are even grounds for identifying other similar images as bulls, such as the figurines from the vessel from Starozagorski Mineralni Bani. No one commented on why there were two bulls from grave 36 and why one was large and the other small. In the case of the scene on the vessel from Starozagorski Mineralni Bani, there are six bulls, a whole herd. Herds of bulls were a symbol of power and wealth because they were bred for sacrifice to the god Zeus, but this was done much later in another historical period.

The presented relief on a vessel from Kozareva Mogila depicting a cow, a bull, a man and a woman is a key to clarifying such situations. From it can be seen the way of depicting the sex of cattle and humans. In cattle, the sex is marked only in the male animal with the depiction of a phallus, and in humans, only in the female individual, with embossed breasts.

Therefore, the famous gold bulls from the Varna Necropolis are gold cows or a gold cow with a golden calf.

List of Literature

Andreescu R.-R. 2002. Plastica Antropomorfă Gumelniţean. Analiză Primară. (Monografii III). Bucureşti: MNIR.

Berciu D. 1961. Contribuţii la problemele Neoliticului in Romania in lumina noilor cercetari. Bucuresţi.

Hansen S. 2009. Kupfer, Gold und Silber im Schwarzmeerraum währenddes 5. und 4. Jahrtausends v. Chr. J. Apakidze, B. Govedarica, B. Hänsel (eds.) Der Schwarzmeerraum vom Äneolithikum bis in dieFrüheisenzeit (5000 – 500 v. Chr.). Kommunikationsebenen zwischen Kaukasus und Karpaten. Internationale Fachtagung von Humbold-tianern für Humboldtianer im Humboldt-Kolleg in Tiflis/Georgien (17 – 20 Mai 2007). Rahden/Westf, p. 11–50.

Hansen S., Toderaş M., Wunderlich J. 2012. Pietrele, Măgura Gorgana: Eine kupferzeitliche Siedlung an der Unteren Donau. W. Raeck, D. Steuernagel (eds.) Das Gebaute und das Gedachte: Siedlungsform, Architektur und Gesellschaft in prähistorischen und antiken Kulturen. Frankfurter archäologische Schriften 21. Bonn, p. 85–97.

Georgieva P. 1998. Early Eneolithic Pottery from a Burnt Dwelling from the Kozareva Mogila Tell near Kableshkovo. M. Stefanovich, H. Todorova, H. Hauptmann (eds.) James Harvey Gaul in Memoriam, In the Steps of James Harvey Gaul I. Sofia, p. 153–160.

Georgieva P. 2012. A Newly Discovered Necropolis in the Southern Part of the West Black Sea Coast–Issues of Cultural Interpretation. Pontica, XLV, p. 395–404.

Georgieva P. 2014. Opportunities for tracing influences of the Balkans on Anatolia during the end of the fifth and the beginning of the fourth millennium BC. Bulgarian e-Journal of Archaeology, 4, p. 217–236. Available at: https://be-ja.org/index.php/journal/issue/view/be-ja-4-2-2014 [accessed on 4 December 2022].

Georgieva P. 2019. On the Organisation of Ceramic Production within the Kodjadermen–Gumelniţa–Karanovo VI, Varna, and Krivodol–Sălcuţa–Bubanj Hum Ia Cultures. S. Amicone, P. Sean Quinn, M. Marić, N. Mirković-Marić, M. Radivojević (eds.) Tracing Pottery-Making Recipes in the Prehistoric Balkans 6th–4th Millennia BC. Archaeopress Archaeology, Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., p. 38–53.

Georgieva P., Milanov P. 2005. Eneolithic Clay Rattles from Bulgaria – Ways of Interpretation. Archaeologia Bulgarica, IX, p. 13–28.

Georgieva P., Russeva V. 2016. Human Skull Artifacts – Roundels and a Skull Cap Fragment from Kozareva Mogila, a Late Eneolithic Site. Archaeologia Bulgarica, 2, p. 1–28.

Georgieva P., Popova M., Danov V. 2018. Kozareva Mogila: A settlement and necropolis in the West Black Sea region. S. Dietz, F. Mavridis, Ž. Tankosić, T. Takaoğlu (eds.) Transition: The Circum-Aegean Area during the 5th and 4th Millennia BC. Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens, Vol. 20, p. 107–119.

Georgieva P., Danov V. 2021. Kozareva mogila – the Eneolithic Necropolis (Excavations 2005–2018). Archaeologia Bulgarica, Supplement 2. Sofia.

Gimbutas M. 1977a. Gold Treasure at Varna. Archaeology, 30(1) (January 1977), p. 44–51.

Gimbutas M. 1977b. Varna a sensationally rich cemetery of the Karanovo civilization, about 4550 B.C. Expedition Summer 1977, p. 39–47.

Gleser R. 2019. An evolutionary perspective on an unusual artefact. M. Gleser, D. Hofmann (eds.) Contacts, Boundaries & Innovation. Exploring developed Neolithic societies in central Europe and beyond. Leiden (Sidestone Press), p. 181–199.

Pătroi C. 2015. Cultura Sălcuţa in Oltenia. Craiova, Romania.

Petrescu-Dâmboviţa M. 1953. Cercetări arheologice la Surduleşti. Materiale şi cercetări arheologice, 1, p. 523–542.

Radu A. 2002. Cultura Sălcuţa în Banat. Reşiţa: Editura Banatica.

Šljivar D., Jacanović D. 2005. Zoomorphic Figurines from Belovode. Recueil du musee National, XVIII-1, Archеologie. Belgrade, p. 69–78.

Stîngă I. 1988. Reprezentări plastice aparţinând neoliticului târziu, din judeţul Mehedinţi. – Revista muzeelor și monumentelor. Muzee, 6, p. 36–40.

Георгиева П. 2003. За края на енеолита по Западнотo Черноморие. Festschrift fur Prof. Dr. habil. Henrieta Todorova. Добруджа, 21, с. 214–238.

Георгиева П. 2010. Керамична работилница от Козарева могила – възможности за интерпретация. Studia Archaeologica Universitatis Serdicensis, Suppl. V, Stephanos Archaeologicos in honorem Professoris Stephcae Angelova, Sofia, с. 25–39.

Георгиева П. 2014. Костени антропоморфни фигурки от Козарева могила. Годишник на Националния Археологически музей. 12, София. In memoriam Lilyana Pernicheva-Perets, с. 225–232.

Димитров М. 2002. Митологични сцени върху керамични съдове от селищната могила при Старозагорски минерални бани. Известия на Старозагорския исторически музей, том I. Stara Zagora, с. 9–18.

Иванов И. 1978. Съкровищата на Варненския халколитен некропол. Септември, София.

Маразов И. 1994. Митология на златото. Христо Ботев, София.

Миткова Р. 2005. За един знак от къснохалколитната орнаментика. Васил Гюзелев (ред.) Културните текстове на миналото: носители, символи и идеи. Сборник в чест на 70 годишнината на проф. К. Попконстантинов, ІІІ. София: УИ “Св. Климент Охридски”, с. 7–20.

Миткова Р. 2008. Къснохалколитна керамична антропоморфна фигурка от чашата на язовир „Тича”. М. Гюрова (ред.) Праисторически проучвания в България: новите предизвикателства. София: НАИМ-БАН, с. 194–204.

Николов В. 2006. Култура и изкуство на праисторическа Тракия. Летера, Пловдив.

Перничева Л. 2004. Халколитни антропоморфни фигури от Кирилово, Старозагорско. В. Николов, К. Бъчваров, П. Калчев (ред.) Праисторическа Тракия. Доклади от международния симпозиум в Стара Загора 30.09–04.10.2003. София – Ст. Загора, АИМ-БАН, РИМ Ст. Загора, с. 455–467.

Радунчева А., Холевич Б. 2000. Manus Vara Congenita или най-ранното семантично ниво за създаване на образа на богинята със змиите. Годишник на Департамент Археология – НБУ/АИМ, IV–V. София, с. 169–172.

Терзийска-Игнатова С. 2000. Къснохалколитни антропоморфни съдове и култови масички от селищната могила при Юнаците, Пазарджишко. В. Николов (ред.) Карановски конференция за праисторията на Балканите 1. Тракия и съседните райони през неолита и халколита. София: АИМ-БАН, с. 113–120.

Чохаджиев С. 2001. Ваксево. Праисторически селища. В. Търново.

Чохаджиев С. 2004. Трипръстни антропоморфни изображения: поява и разпространение. В. Николов, К. Бъчваров, П. Калчев (ред.) Праисторическа Тракия. Доклади от международния симпозиум в Стара Загора 30.09–04.10.2003. София - Ст. Загора. АИМ-БАН, РИМ Ст. Загора, с. 408–420.

Чохаджиев С. 2005. За предназначението на някои женски антропоморфни фигури – хронологически индикатор на късния халколит. Епохи, 3–4, с. 21–28.