Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2022, vol. 23, pp. 107–119 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2022.23.6

Cultural Interactions Between the Societies of the ‘Old Europe’ and the Steppe ‘Kurgan People’ During the Last Quarter of the 4th Millennium BC: Case Study of Serezlievka Local Group

Mykyta Ivanov

PhD.-candidate

National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy

mykyta.ivanov@ukma.edu.ua

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8473-9165

Mykola Tupciyenko

PhD, associate professor

Central Ukrainian National Technical University

tupchy_mp@ukr.net,

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7076-4861

Abstract. Cultural interactions between the societies of Old Europe and the Steppe ‘Kurgan people’ played a significant role in the academic writings of Maria Gimbutas. In her texts, the interplay between mentioned human groups was described as a dichotomy and was put into a framework of violent struggle. Three waves of destructive intrusion of steppe pastorals were reconstructed and the determinative role of ‘kurgan people’ in the spread of Indo-European nations was described (Gimbutas, 1993). However, although Gimbutas’ model is still influential and is used as a methodological framework for the most recent genomic studies (Haak et al., 2015), (Allentoft et al., 2015), (Juras et al., 2018), (Scorrano et al., 2021), there are certain archaeological data that allow suggesting a more complicated interaction than simple ‘east-to-west’ migration. In the current paper, we will publish a rare example of a kurgan burial with mixed Late Trypillia and ‘steppe’ traits, excavated by one of the authors in 1989 near the village of Pomichna. The context of similar burials discovered in the south of Eastern Europe between the South Buh and Dnieper rivers will be provided. The emergence of the Serezlievka local group with a hybrid Trypillia-steppe identity at the end of the 4th millennium BC will be conceptualized.

Keywords: Late Trypillia, kurgan, pottery, steppe, jewelry, anthropomorphic figurines, Indo-Europeans.

Kultūrinės sąveikos tarp žemdirbių ir klajoklių visuomenių paskutiniame IV tūkstm. pr. Kr. ketvirtyje: Serezlivkos lokalinės grupės atvejo analizė

Anotacija. Marijos Gimbutienės darbuose išsamiai nagrinėta Senõsios Europos visuomenės ir stepių „kurganų tautos“ kultūrinė sąveika. Archeologės tekstuose šių žmonių grupių sąveika buvo apibūdinama kaip abipusė ir nusakoma smurtinės kovos samprata. Rekonstruotos trys destruktyvaus stepių „kurganų tautos“ įsiveržimo bangos, aprašytas lemiamas „kurganų tautos“ vaidmuo indoeuropiečių sklaidoje (Gimbutas, 1993). Tačiau nors M. Gimbutienės pateiktas modelis vis dar turi įtakos ir yra naudojamas kaip metodologinis pagrindas naujausiems genominiams tyrimams (Haak ir kt., 2015; Allentoft ir kt., 2015; Juras ir kt., 2018; Scorrano ir kt., 2021), yra tam tikrų archeologinių duomenų, leidžiančių manyti, kad toji sąveika buvo sudėtingesnė nei paprasta migracija iš rytų į vakarus. Šiame straipsnyje pristatomas retas, 1989 m. netoli Pomičnos kaimo vieno iš straipsnio autorių tyrinėtas kurganinis palaidojimas, kuriame fiksuota mišri vėlyvosios Tripolės ir stepių kurganų kultūros įtaka. Panašių palaidojimų aptikta ir kitose vietose tarp pietų Bugo ir Dniepro upių.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: vėlyvoji Tripolė, kurganinis palaidojimas, keramika, stepė, papuošalai, antropomorfinės figūrėlės, indoeuropiečiai.

_____________

Acknowledgements. I started working on this paper in November 2021 in Kyiv. On February 24th, 2022 Russian Federation launched a full-scale war against Ukraine. Kyiv appeared besieged. Many men and women were called to arms to protect Ukraine’s independency including academics. Currently, more than 30 archaeologists serve in different Ukrainian military units and risk their lives daily. I want to say thank you to all my colleagues for sacrificing their academic careers so that I could finish my research in safety. I am especially grateful for my closest friends Ivan Dergachev, Anna Argunova and Maxim Zhylenko. Also, I owe gratitude to the keeper of the Kirovohrad museum of local history Pavlo Rybalko who unsealed the deposit for me in August of 2022 so I could take the pictures (M. Ivanov).

Funding Acknowledgements. This work was supported by an individual grant in 2021 from the Yuchymenko Family Fund (endowment) for the Development of the Yuchymenko Family Doctoral School at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

Received: 02/09/2022. Accepted: 21/11/2022

Copyright © 2022 Mykyta Ivanov, Mykola Tupciyenko. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Cultural interactions between the societies of Old Europe and the inhabitants of the Eurasian Steppe played a significant role in the academic writings of Maria Gimbutas discussing the emergence and spread of Indo-European people. Starting with the 1956 monograph (Gimbutas, 1956), M. Gimbutas consequently developed a three-wave model of Indo-Europeanization of Europe implying a violent intrusion of ‘kurgan people’ from the East (Gimbutas, 1977), (Gimbutas and Marler, 1991). Wave I was dated c. 4400–4300 BC and was associated with the so-called Early Yamnaya culture; wave II – 3500 BC and was assigned to the Mikhailovka I (Lower Mikhailovka) and Maikop cultures; wave III – 3000 BC and was appointed to the Late Yamnaya culture (Gimbutas, 1993, pp. 206–207).

Introduced more than 60 years ago, Gimbutas’ model remains influential and is used as an interpretative framework for some paleogenetic studies. In 2015 two different research teams led by M. Allentoft (Allentoft et al., 2015) and G. Haak (Haak et al., 2015) identified a significant admixture of the Yamnaya people’s ‘steppe’ genome in the ancient DNA of the Corded Ware people suggesting a massive migration of the Yamnaya people to the Central Europe c. 3000 BC. During the next years, the same results were received by M. Juras and their team (Juras et al., 2018), and G. Scorrano and their team (Scorrano et al., 2021). A slight adjustment to the existing model was made in 2018 when scholars received the first data from Central Ukraine (Mathieson et al., 2018). Among three newly published analyses of the Yamnaya people’s genome, one demonstrated (I1917) northwestern-Anatolian-Neolithic-related admixture suggesting the participation of the Late Tripillia people in the genesis of Yamnaya culture. Although such an interpretation may seem a drastic contradiction to Gimbutas’ model, it is not a surprise for scholars who specialize in the study of the earliest kurgan cultures of the Ukrainian steppe. As of today, a voluminous collection of the Late Trypilia artefacts originating from the kurgan burials of the Buh–Dnieper interfluve exist indicating a significant influence of Late Trypillia culture on the ‘kurgan people’ of Gimbutas’ wave II. The result of such influence is the emergence of a mixed Trypillia-‘kurgan’ culture which we propose to name the Serezlievka local group. Unfortunately, due to the lack of published archaeological materials, the Serezlievka phenomenon remains unknown to a wide academic audience. An attempt at filling the knowledge gap is made in the following paper. In the text below, we present the complete data about one of the Serezlievka burials excavated in 1989 near the village of Pomichna, Kirovohrad region, which was never published before. A detailed description of the site as well as the typology and dating of obtained archaeological materials will be provided. Cultural-historical attribution of the site will be discussed as well.

Site description

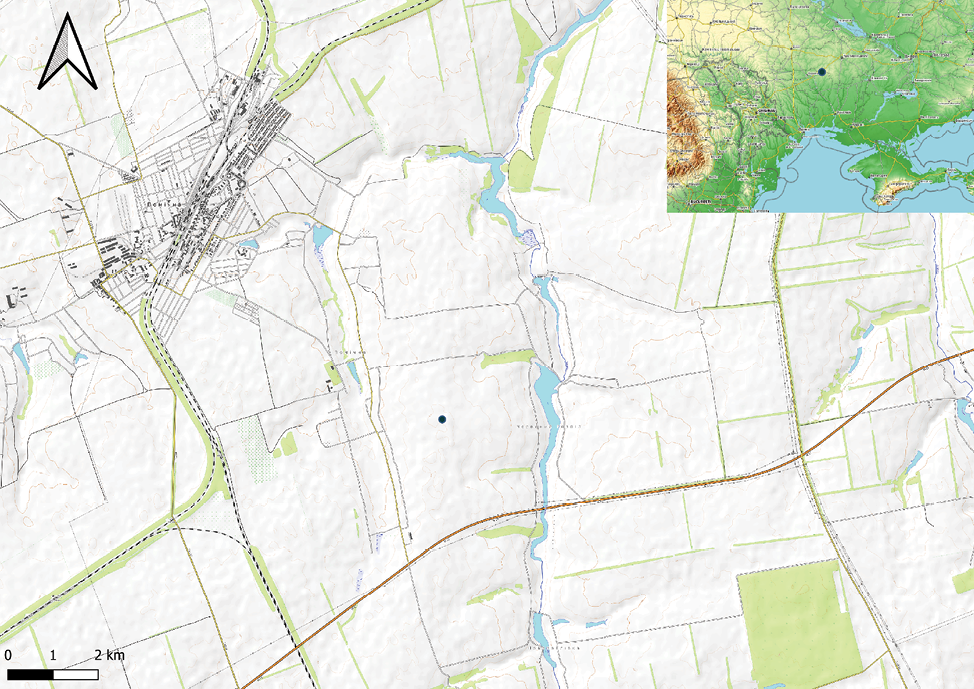

During the June–July of 1989, the Archaeological expedition of the Kirovohrad museum of local history led by M. Typciyenko excavated two kurgans near the village of Pomichna. Both monuments held the high ground and were placed on the right bank plateau of the river Pomichna 2.5 km east-southeast from the village (fig. 1). Although both kurgans provided peculiar archaeological material, only the kurgan No. 1 is valuable for our current research. The size of the mentioned burial mound at the moment of excavation had medium proportions with a diameter of 58 × 48 m and a height of 2.3 m. As was identified by the cross-section, the body of kurgan was constructed in four steps. The first layer of a mound with a diameter of 11–12 m and height of 0.7 m was constructed over the Late Eneolithic burial No. 25, and the second one – over the Yamnaya culture burial No. 2. Layers No. 3 and No. 4 were added during the later times. The total count of the burials discovered underneath the kurgan reaches 61 graves, 2 of which are associated with Late Eneolithic, 27 with the Yamnaya culture, 8 with the Catacomb culture, 7 with the Babyno culture, 6 with the Sabatinovka culture and 2 with Cimmerians. The cultural and chronological attribution of another 10 graves is problematic.

Fig. 1. Location of the kurgan Pomichna 1.

1 pav. Kurganinio palaidojimo Pomichna 1 vieta

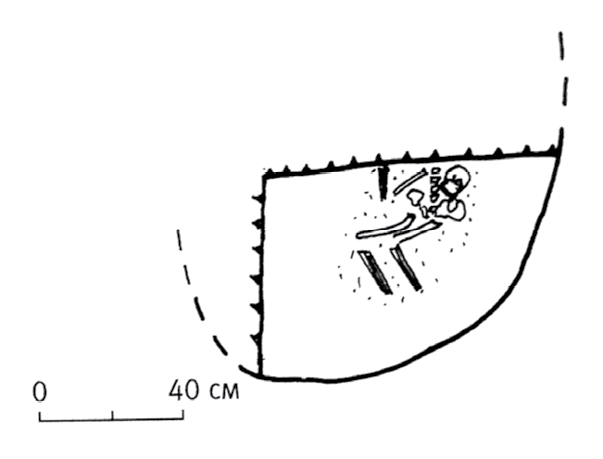

A significant for the current paper burial No. 50 was located at the distance of 5.7 m to the south-southeast from the center of a kurgan at the depth of 1.5 m from its top. The grave itself had a shape of an oval with a width of 0.85 m. At the bottom of a grave archaeologists cleared a skeleton of a three-year-old child laying crouched on a rind bedding. The upper part of the skeleton was ruined. A child’s right hand laid straight; the left hand was bent in an elbow. The legs of a buried were bent in the knees and laid on the right side. Feet were absent. Pelvis and tibias were painted with ocher (fig. 2). Although the preservation of a skeleton does not allow us to reconstruct the pose of a deceased completely, we may assume that it is laid in a type III-C pose according to the classification developed by Ju. Rassamakin (Ju. Rassamakin, 2004, tbl. 1).

Fig. 2. A drawing of a burial Pomichna 1/50 (drawing by M. Typciyenko).

2 pav. Pomichna 1/50 palaidojimo piešinys (M. Typciyenko pieš.)

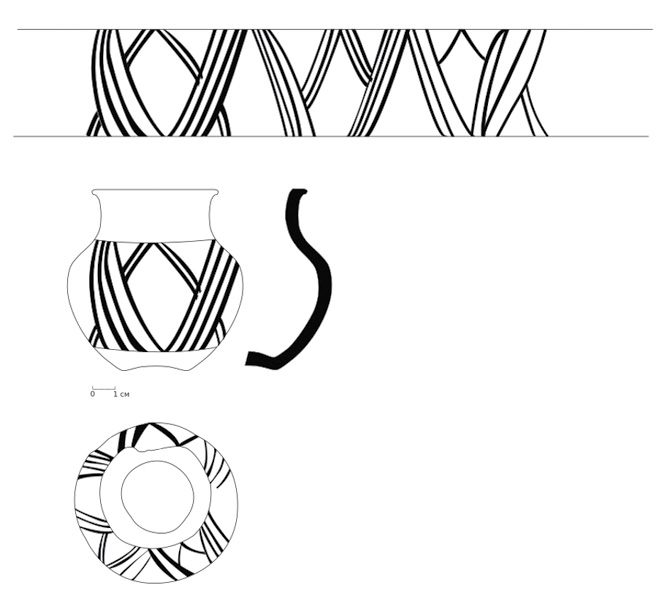

While clearing the grave, near the child’s left ilium archaeologists also found a small painted beaker of a Late Trypillia culture (fig. 3, 4). The discovered vessel had a concave bottom, a round body, a narrow high neck, and a wide bent outwards rim. The transition from a body of a vessel to the neck is emphasized with a scratched line. The color of the vessel is light brown. The ceramic dough is of high quality with few admixtures of gruss. The surface of a vessel is smooth with few pores and is covered with geometrical decoration made with pale brown paint. An ornamental composition of a vessel constitutes of slant lines composing several rhombuses, triangles, and zigzags. From the top view, the ornament reminds of a star or a flower (fig. 4). The closest analogy of such decorative style can be observed in the Gordinești local group of Late Cucuteni–Trypillia culture where it is derived from a reduction of the traditional Trypillia spiral (Овчінніков, Винагородська, Болтанюк, 2013, p. 15).

Fig. 3. Late Trypillia beaker found in the burial Pomichna 1/50 (photo by M. Ivanov).

3 pav. Pomichna 1/50 palaidojime rasta vėlyvosios Tripolės taurė (M. Ivanovo nuotrauka)

Fig. 4. Late Trypillia beaker found in the burial Pomichna 1/50 (drawing by M. Ivanov and Ju. Khodukina).

4 pav. Pomichna 1/50 palaidojime rasta vėlyvosios Tripolės taurė (M. Ivanovo ir Ju. Khodukinos pieš.)

Absolute dating of the burial is problematic. Unfortunately, due to the poor preservation of the bones as well as the lack of financial resources analysis for the C14 content was never done. For this reason, the only way to establish the burial’s chronological position is to refer to relative dating methods: typology and stratigraphy. As was said, the found beaker displays a great similarity to the painted pottery of the Gordinești local group which existed during 3360–2900 BC cal. (Sîrbu, Król and Heghea, 2020, p. 130) and is contemporaneous with the Sofievka culture (3300–2950 BC cal. (Harper, 2021, fig. 1)) and Usatovo culture (3500–2800 BC cal. (Петренко and Кайзер, 2011, p. 55)). The stratigraphic position of a grave under the first layer of a barrow in its turn indicates that the burial was constructed before the emergence of the Yamnaya culture. The oldest AMS-dated Yamnaya graves of the Kirovohrad region that can serve as a terminus ante quem are the burials No. 14 and No. 8 from the Sugokleja Mohyla (Nikolova and Kaiser, 2009). The burial No. 14 is dated 3006–2884 BC cal. and the burial No. 8 3088–2925 BC cal. or 3097–2940 BC cal. In such a way, the chronological frames of the burial of Pomichna 1/50 and the forthcoming Yamnaya culture conjoin.

A peculiar detail about the vessel is its small size. The height of a beaker is only 6.9 cm, the height of a neck is 1.2 cm, the diameter of the rims is 5.1 cm, the diameter of the body is 7.6 cm, and the diameter of the bottom is 3.3 cm. On the other hand, the walls are rather heavy with a thickness of 0.5 cm, which contrasts with the Trypillia BII-CI beakers whose thickness is usually around 0.2–0.3 cm. Nevertheless, such a small size of a beaker along with the similarity of its morphology to some large Gordinești beakers and amphoras suggests that it is a miniature copy of the ‘adult’ pottery made for the buried child. The latter fact is especially important for the cultural attribution of the burial as a Trypillia one. If a vessel was specifically made for a certain person, it should represent its owner’s identity rather than be an ‘import’ from a foreign culture.

In such a way, the described grave Pomichna 1/50 combines exclusively the traits of a ‘steppe’ kurgan burial rite with Late Trypillia material complex and should be considered as evidence of a mixed steppe-Trypillia identity emerging in the interfluve of South Buh and Dnieper rivers during the second half of the 4th millennium BC. Following the idea expressed by V. Dergachev and I. Manzura (Дергачев and Манзура, 1991), we suggest naming the archaeological phenomena standing behind this identity as a Serezlievka local group. Its history of research, as well as its geography, material culture and funeral tradition, will be described in detail below.

Serezlievka local group: history of recognition

The beginning of the research interest in the Serezlievka local group reaches the dawn of kurgan studies in Ukraine and is associated with the excavations conducted by Danylo Shcherbakivskyi in 1904 near the villages Serezlievka and Vilshanka located in the modern Kirovohrad region (Щербаковский, 1905, 1908). During the excavations, archaeologists discovered several burials accompanied by peculiar grave goods which the scholar correctly attributed to the Trypillia culture. Kurgan Serezlievka 4 included a painted beaker while a kurgan Serzlievka 7 contained a schematic anthropomorphic figurine that later became a benchmark for the identification of Serezlievka-type sculpture. Kurgan Vilshanka 3 in its turn included a wolf-teeth neckless and several vessels currently attributed to the Usatovo culture while kurgan Vilshanka 2 provided a flat As-bronze axe. The further investigation of Eneolithic and Early Bronze age steppe kurgans as well as the advancement of Trypillia culture chronology proved the legitimacy of Shcherbakivskyi’s attribution and provided ground for the identification of Trypillia presence in the interfluve of Southern Buh and Dnieper. In 1949 a known researcher of Trypillia culture T. Passek published her famous periodization of the culture of interest and dated Serezliievka’s and Vilshanka’s findings as well as vessel form Belozerka with the latest stage of culture’s development named ‘Trypillia γ/II’ (Пассек, 1949, p. 194). In 1953 O. Lagodovska complemented the catalogue of Late Trypillia artefacts originating from Right-bank Ukraine and assumed mentioned archaeological material as a local manifestation of Usatovo culture (Лагодовська, 1953). Lagodovska’s suggestion gained supportive acknowledgement (Мовша, 1960, pp. 67–69) and kept the status of a mainstream hypothesis until 1974 when another Trypillia expert V. Zbenovych drew attention to significant differences in the burial rite’s features characteristic of the Usatovo culture and Buh–Dnieper local group. In Zbenovych’es opinion, the Eneolithic burials of the Buh–Dniper interfluve represent a unique local variant of Late Trypillia culture (Збенович, 1974b, p. 156). In 1991 the mentioned archaeological phenomenon received a new name – Serezlievka local group (Дергачев, Манзура, 1991, p. 14), which we will use further.

An opposite attitude towards the systematization of the Late Eneolithic archaeological material of the Buh–Dnieper interfluve was demonstrated by authors specializing in the studies of ‘kurgan cultures’. While analyzing Late Eneolithic burial mounds of the mentioned region, they used to include Trypillia-like burials into their own ‘steppe’ cultural taxonomy that was built around the buried people’s pose. For example, I. Kovalova included all straight laying burials in a post-Mariupol culture regardless of their grave goods (Ковалева, 1984, pp. 4–53) while D. Telehin and O. Shaposhikova included some burials with Trypillia artefacts into Nizhnemikhailovka culture (Телегін, 1971, p. 15; Шапошникова, Бочкарев, Шарафутдинова, 1977, p. 9). For those scholars, foreign pottery of the Trypillia type and exotic figurines are nothing more than evidence of trade relations between Trypillia and ‘steppe’ cultures. A direct genetic relation between the Buh–Dnieper burials and Late Trypillia culture was denied.

In such a way, two competitive interpretative models exist. While the first one acknowledges Serezlievka burials as Tripillian, the second one associates them with the ‘steppe’ ‘kurgan’ tradition. Since further conclusions about the genetic and linguistic characteristics of the Serezlievka local group are arranged according to the chosen model, it is especially important to select the best-argued one. In our opinion, Tripillian attribution is more favorable. Complete data on the Tripillian component of the Serezlievka material culture will be presented in the following section.

Tripillian component of the Serezlievka local group: current state of research

Among all of the Late Eneolithic artefacts, discovered in graves and cultural layers of several settlements the most vivid Trypillia traits are manifested through pottery, clay sculpture and metal jewelry. Summarized characteristics of those artefacts as well as data about their context will be provided below.

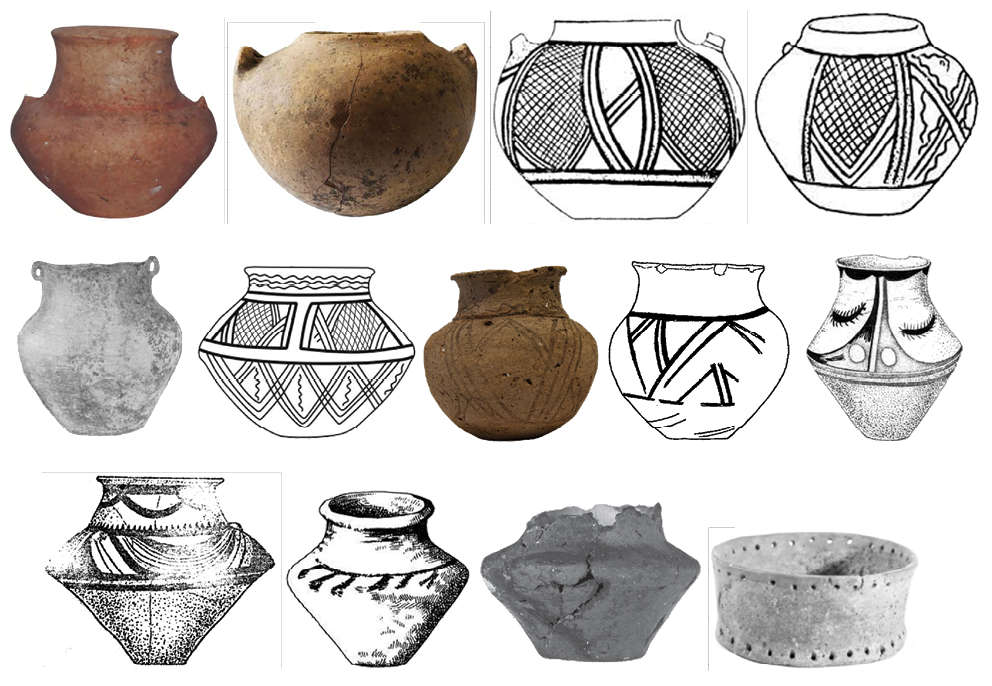

Pottery

The pottery assemblage of the Serezlievka local group consists of two pottery types of different quality: so-called ‘steppe’ kitchenware and Tripillian fine ware. Steppe pottery makes up 57% (25 specimens) of all vessels found in Late Eneolithic graves of the Buh–Dnieper interfluve, while Tripillian makes 43% (19 vessels originating from 18 graves). The steppe pots are characterized by a rounded body, a pointed or rounded bottom and deflected outside rims. The outer surface of steppe pottery is mostly undecorated. The rare examples of decoration technics applied for the vessel’s adornment include comb stamps, notches, and cord imprints. The ceramic dough of steppe pottery often includes pounded shells and limestone. The low quality of ‘steppe’ ceramics as well as the lack of decoration suggest that it was mainly used as regular kitchenware. The Tripillian ceramics (fig. 5), in its turn, represents elegant dishes kept for special occasions. It is usually made of clean clay and is decorated with sophisticated painted ornaments. Morphologically the mentioned vessels belong to several different types among which beakers and beaker-like pots (9 specimens) are the most common (fig. 5: 7–11). Amphora and amphora-like vessels constitute the second biggest group and are represented by 5 specimens (fig. 5: 1–6). The rest of the vessels possess a unique shape and cannot be unified into a single type.

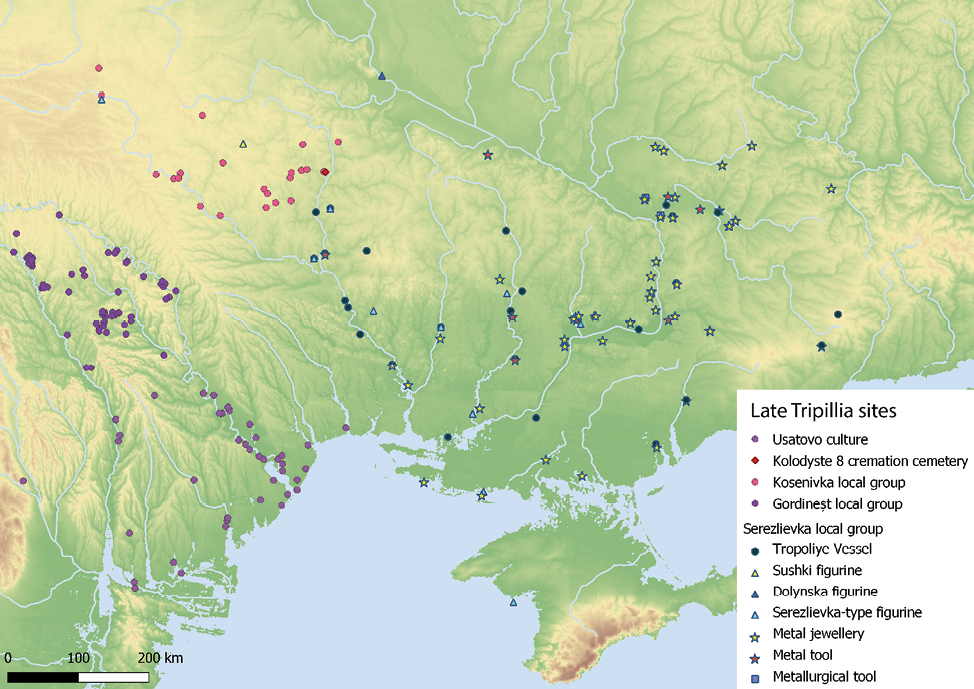

The geographical distribution of mentioned burials is unequal (fig. 6). While valleys of South Buh, Inhulets and Dnieper rivers are rich for Trypillia pottery, the stream of Inhul river provides almost none of such artefacts. Historical interpretation of such disproportion is problematic since it speaks for both the prehistoric population’s settling habits and bias in the choice of kurgans for excavation.

Fig. 5. Some of the Late Trypillia vessels originating from the burials of the Serezlievka local group. 1 – Dubova Mohyla 10; 2 – Velyka Oleksandrivka 1/23; 3 – Yermolaiivka 2; 4 – Bilozerka; 5 – Kryvyi Rih; 6 – Volodymyrivka; 7 – Pomichna 1/50; 8 – Zavadivski Mohyly 9/10; 9, 10 – Prybuzhany 4/19; 11 – Serezlievka 4; 12 – Vyshchetarasivka 79/13; 13 – Olshanka 3 (composed by M. Ivanov).

5 pav. Vėlyvosios Tripolės indai iš Serezlievka vietinės grupės palaidojimų. 1 – Dubova Mohyla 10; 2 – Velyka Oleksandrivka 1/23; 3 – Yermolaiivka 2; 4 – Bilozerka; 5 – Kryvyi Rih; 6 – Volodymyrivka; 7 – Pomichna 1/50; 8 – Zavadivski Mohyly 9/10; 9, 10 – Prybuzhany 4/19; 11 – Serezlievka 4; 12 – Vyshchetarasivka 79/13; 13 – Olshanka 3 (sud. M. Ivanovas)

Fig. 6. Late Trypillia sites of the Northern Pontic region. Point markets are tied to the nearest village and not to the real location of a site. The accuracy of localization is 10 km (map by M. Ivanov).

6 pav. Šiaurės Pontiko regiono vėlyvosios Tripolės radavietės. Taškai yra susieti su artimiausiu kaimu, o ne su realia lokacija. Lokalizacijos tikslumas – 10 km (M. Ivanovo žemėlapis)

The funeral rite of burials accompanied by Trypillia pottery is various which entangled their cultural attribution and postponed their recognition as a single archaeological entity. Deceased people owning Trypillia vessels may lay straight (2 cases), crouched on their side (5 cases), or crouched on their back with their legs bent in knees and raised (3 cases).

The exact function of Tripillia pottery, both practical and symbolic, is a matter of question. The small size of the beakers and their specific shape suggest that they were used for individual consumption of liquids – inebriating or non-toxic – rather than product storage. Since the exact identification of the beaker’s containment is problematic (the only attempt at analyzing lipids remaining on the interior surface of ceremonial flasks found inside the Nebelivka communal house was failing (Kreig et al., 2020)), we can speak about the beakers’ purpose only hypothetically. The list of available beverages that could have been poured includes water, fruit juice, and milk as well as several alcoholic drinks: beer, mead and fermented dairy products. The latter group is of special importance. Attested for the first time in Europe during the 5th millennium BC and gaining popularity during the 4th and 3rd millennia BC (Guerra-Doce, 2015) alcoholic drinks played an exceptional role in the construction of Eneolithic and Early Bronze age communication networks and social hierarchies (Turek, 2020). Seasonal or irregular drinking festivities were suitable occasions for visiting neighbors and tightening friendly relations. The ancient rule of gift and payback meant that generously treated guests will provide additional workforce or military support in time of need. To facilitate drinking festivities the European potters of the Eneolithic and Early Bronze Age developed a specific complex of vessels designed for brewing, storing, mixing, pouring and drinking alcohol. The assemblage included such pottery types as beakers, amphoras, large storage jars, jugs, and bowls. The first two types also exist in the Tripillian pottery collection of the Buh–Dnieper interfluve. In such a way, we believe that the presence of Tripillian pottery inside the Serezlievka burials means a much deeper cultural influence than the simple import of luxurious vessels and additionally implies the adaptation of foreign rituals, customs and social norms.

Clay sculpture

The unique feature of the Serezlievka local group is the so-called Serezlievka figurines. Since many figurines come in fragments, the exact number of known sculptures is a question of debate. For example, N. Burdo counted 34 specimens (Бурдо, 2018b, fig. 1) while Ju. Rassamakin counted only 29 (J. Rassamakin, 2004, fig. 1). To mentioned counts we should also add the newest find made in 2019 in the cultural layer of the Chekon settlement of the Maikop culture (Rassamakin, 2021, p. 338). Geographically most of the figurines concentrate on the interfluve of Southern Buh and Dnieper rivers while single finds were made in Podolia (Sandraky settlement), Crimea (Zaozerne k.17 (Попова, 2016, p. 704)) and Kuban (Chekon settlement). A peculiar detail of the spatial distribution of figurines is their frequent coincidence with the Trypillia vessels (fig. 6). In one case Serezlievka type figurine was found in the same burial as the Trypillia vessel (burial Yermolaivka 2); in two cases – within the same kurgan (burials Barativka 1/5 and 1/16, Chkalovka 3/11 and 3/25); in another case – within the same kurgan group (kurgans Serezlievka 4 and 7); in two cases a figurine and a vessel were found at a distance less than 10 km from each other (Dubova Mohyla–Shyroke 7 km and Zavadivski Mohyly–Dovha Mohyla 9 km); in two cases the distance between artefacts varied from 25 to 35 km (Zelenyi Hai–Kryvyi Rih 25 km, Prybuzhany–Petropavlivka or Vynohradnyi Sad–Petropavlivka 35 km). The context of the finds is various: kurgan burials, underhill space (Zaozerne k.17), and the settlement’s cultural layer (Sandraky, Chekon).

Morphologically Serezlievka figurines constitute a highly schematic depiction of the human body: the figurine’s corpse is represented by a long straight or slightly bent cylinder while the figurine’s hands are portrayed as small humps. The signs of sex are absent which contrasts with the classical Trypillia clay sculpture whose gender is clearly manifested. The decoration of figurines is simple and is usually built of straight or slightly slant mortise lines encircling the body. Sometimes, the lines are filled with white paste. In rare cases, like with a sculpture from the kurgan Serezlievka 7, the figurine’s body can be twined with the imprints of a cord.

The origin of Serezlievka-type figurines is arguable. On the one side, those figurines are completely different from the classical Trypillian clay sculpture; on the other side, they are too delicate for the products of ‘steppe’ potters. Moreover, the tradition of personal small-scale sculpture is foreign to the forthcoming Yamnaya culture, which preferred constructing large stone stelae. In our opinion, Serezlievka figurines are the result of a creative rework of Trypillia heritage and a search for new iconographic styles.

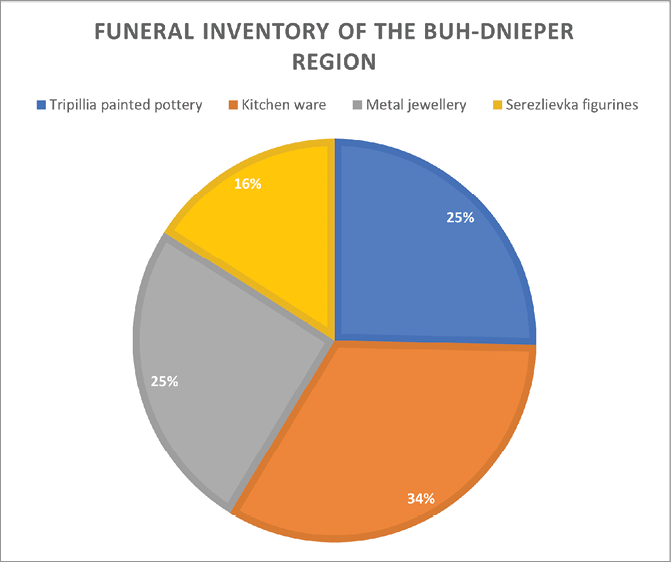

Copper jewelry

Among other types of physical objects, personal adornment represents a person’s identity most vividly. While having no pragmatic value, copper jewelry was deliberately designed to construct and negotiate affiliations along lines of ethnicity, gender, age, societal status and wealth. In the Buh–Dnieper interfluve, 19 Late Eneolithic burials that included any kind of copper jewelry are currently known. The share of jewelry among other sepulcher inventory is surprisingly large. 25% of all equipped graves included any kind of jewelry which is almost equal to the share of kitchenware (34%), Tripillia painted pottery (25%), Serezlievka figurines (16%) (fig. 7). The amount of jewelry placed in a single grave varies a lot. While most of the burials held meager necklaces, one of them was especially rich. A deceased person buried in the grave 5 of the kurgan Chkalivka k.gr.II, k.3 possessed a total of 242 copper tubes and rings (Рассамакин, 2004, p. 38). Morphologically copper jewelry can be classified into several categories:

- Rings made of metal wire with a rectangular cross-section;

- Tubes made of rectangular rolled metal plates;

- Spiral beads made of wire;

- Metal plates that served as overlays for belts.

Speaking of jewelry’s origin, we believe it was produced within workshops of Tripillia culture, for which personal adornment of a different type was an integral part of the material complex. As of today, 19 Tripillian jewelry hoards are known concentrating along the Dniester river (Dergachev and Parnov, 2022, p. 27).

The technology of jewelry production, as was shown by the studies of N. Ryndina (Рындина, 1998, pp. 176–179), is different from any other Eneolithic culture of South-Eastern Europe which implies their local production within Tripillian crafting centers of Dniester valley. At the stages CI-CII of the Tripillia culture development, the geographical range of jewelry distribution expanded further to the east and reached the Dnieper river. Such an expansion may both mean the intensification of cross-regional exchange relations or the migration of Tripillia people to the new territories. Regardless of whether the jewelry was traded, gifted or inherited we assume that it is evidence of close communication between ‘kurgan’ and Tripillian people resulting in the adaptation of foreign aesthetics and societal values.

Serezlievka local group: collective overview

As follows from the provided data the share of Trypillia artefacts among the grave goods of the earliest ‘kurgan people’ is evident and makes up in total 66% of all equipped burials (fig. 7). Painted pottery was found in 25% of all equipped burials, Serezlievka-type figurines in 16%, and metal jewelry in 25%. The so-called ‘steppe’ kitchenware was found, in its turn, only in 34% of all equipped graves. A strict correlation between the sepulcher inventory of the same type and the pose of the deceased was not observed which suggests that all four burial rituals identified by Ju. Rassamakin (Rassamakin, 2004) are contemporaneous.

Fig. 7. The structure of the Serezlievka local group funeral inventory (diagram by M. Ivanov).

7 pav. Serezlievka lokalios grupės palaidojimų įkapės (M. Ivanovo diagrama)

Discussion

The second half of the 4th millennium BC became a time of tremendous changes for the Tripillia culture. With the abandonment of Maidanetske (Ohlrau, 2020, p. 274) and Talianki (Shatilo, 2021, fig. 55) settlements around 3600 BC a bright era of megasites comes to an end while the Tripillia culture itself gradually loses its characteristic features and fades. Among factors negatively affecting the life of Maidanetske and Talianki inhabitants, scholars name climate change (Harper et al., 2019, p. 94), depletion of natural resources (Круц, 1993), ecological crisis (Videiko, 2011, p. 374), and spread of plague and other diseases (Makarewicz et al., 2022, p. 843). Deterioration in the life quality motivated Tripillia people to reclaim new territories – the forest zone of the Upper Dnieper and Desna rivers, the Budzhak steppe and the steppe belt of the Buh–Dnieper interfluve – which resulted in the emergence of new local variants of Late Tripillia culture: Sofievka, Usatovo and Serezlievka. While the first two cultures are well-known entities with a long research history (the first paper about Usatovo culture was published 96 years ago (Болтенко, 1926) and about Sofievka 70 years ago (Захарук, 1952)), identification of Serezlievka local group is a concept relatively new. Introduced in 1991 by V. Dergachev and I. Mazura (Дергачев and Манзура, 1991) the thought of the Serezlievka local group remains an underground rather than mainstream historiographic belief. The main concern which prevents Serezlievka local group from wide academic recognition is the level of Tripillia’s influence on the ‘kurgan’ people of the Buh–Dnieper interfluve. Did Tripillia people indeed migrate to the steppe or simply ‘export’ their artefacts? As we have shown in the previous section, the share of graves equipped with the Tripillia artefacts among other Buh–Dnieper kurgan burials is great and makes up in total 66% of all equipped burials. Painted pottery was found in 25% of all equipped burials, Serezlievka-type figurines in 16%, and metal jewellery in 25%. The ‘steppe’ kitchenware was found, in its turn, only in 34% of all equipped graves. Considering the described quantitative and qualitative domination of Tripillian artefacts, we assume the kurgans of the Serezlievka local group being an integral part of Cucuteni–Tripillia world. If it is true, then M. Gimbutas’ three-wave model requires serious adjustments. Instead of unidirectional east-to-west tension, we assume an oscillating west-to-east and east-to-west movement of people, artefacts, and ideas happening during the 4th and early 3rd millennia BC. At the time of Gimbutas’ wave II (c. 3500–3000 BC), the west-to-east movement prevailed resulting in the formation of the earliest kurgan cultures of the Ukrainian steppe – Usatovo and Serezlievka. Those cultures constitute the background of the forthcoming Yamnaya culture whose movement to the west probably affected the creation of Corded ware and other Early Bronze age cultures of Central Europe.

List of sources

Dergachev V., Parnov V. 2022. The Condrița hoard. Chişinău: Butuceni. Tipografia Centrală.

Klochko V. et al. 2020. The Era of Early Metals in Ukraine (History of Metallurgy and Cultural Genesis). Kyiv: National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

Rassamakin J. 2004. Die Statuetten des Serezlievka-Typs und zum Problem des Beginns der Bronzezeit in der nordpontischen Steppe. Internationale Archäologie. Studia honoria 21 (Zwischen Karpaten und Ägäis. Neolithikum und ältere Bronzezeit. Gedenkschrift für Viera Nemejcova-Pavukova), p. 149–167.

Rassamakin J. 2004. Die nordpontische Steppe in der Kupferzeit: Gräbr aus der Mitte des 5. jts. bis Ende des 4. jts. v. Chr. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

Rassamakin Yu. 2021. The Serezliivka type figurines as an evidence of contacts during the Late Eneolithic. Archaeology and Early History of Ukraine, 39/2, p. 338–349. https://doi.org/10.37445/adiu.2021.02.22.

Бурдо Н. 2018. Антропоморфная пластика курганных погребений раннего бронзового века в Буго-Днепровском междуречье и Поднепровье. Tyragetia (Serie Nouă), 1, p. 97–114.

Дергачев В., Манзура И. 1991. Погребальные комплексы позднего Триполья. Свод источников. Кишинев: Штиинца.

Захарук Ю. 1952. Софіївський тілопальний могильник (Коротке повідомлення про розкопки 1948 р.). Археологічні пам’ятки УРСР, 4, p. 112–120.

Лагодовська О. 1953. Пам’ятки Усатівського типу. Археологія, 8, p. 95–108.

Мовша Т. 1960. К вопросу о трипольских погребениях с обрядом трупоположения. Материалы и исследования по археологии Юго-Запада СССР и Румынской Народной Республики. Кишинев: Картя Молдовеняскэ, p. 59–76.

Попова Е. 2016. Антропоморфная статуэтка из кургана эпохи бронзы некрополя у поселка Заозерное в Северо-Западном Крыму. Исторический журнал: научные исследования, 6/6), p. 703–709. https://doi.org/10.7256/2222-1972.2016.6.19202.

Рассамакин Ю. 2004. Азово-Понтийские степи в эпоху меди (Погребальные памятники середины V – конца IV тыс. до н.э.. Часть ІІ). Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern.

Щербаковский Д. 1905. Раскопки курганов на пограничье Херсонской и Киевской губерний. Археологическая летопись Южной России, 1–2, p. 7–19.

Щербаковский Д. 1908. Отчет об археологической экскурсии в июне и июле 1904 года. Труды тринадцатого археологического сьезда в Екатеринославе. Москва: Товарищество типографии А. И. Мамонтова, p. 104–105.

List of Literature

Allentoft M. E. et al. 2015. Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature, 522/7555, p. 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14507.

Gimbutas M. 1956. The prehistory of Eastern Europe. Mesolithic, neolithic and copper age cultures in Russia and the Baltic area. Cambridge: Peabody Museum (American school of prehistoric researches. Harvard University Bulletin, 20).

Gimbutas M. 1977. The first wave of Eurasian pastoralists into Copper Age Europe. Journal (The) of Indo-European Studies Washington, 5/4, p. 277–338.

Gimbutas M. 1991. The civilization of the Goddess: The World of old Europe. HarperSanFrancisco.

Gimbutas M. 1993. The Indo-Europeanization of Europe: the intrusion of steppe pastoralists from south Russia and the transformation of Old Europe. WORD, 44/2, p. 205–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.1993.11435900.

Guerra-Doce E. 2015. The Origins of Inebriation: Archaeological Evidence of the Consumption of Fermented Beverages and Drugs in Prehistoric Eurasia. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 22/3, p. 751–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-014-9205-z.

Haak W. et al. 2015. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature, 522/7555, p. 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14317.

Harper T. K. et al. 2019. Ecological dimensions of population dynamics and subsistence in Neo-Eneolithic Eastern Europe. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 53, p. 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2018.11.006.

Juras A. et al. 2018. Mitochondrial genomes reveal an east to west cline of steppe ancestry in Corded Ware populations. Scientific Reports, 8/1, Article 11603. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29914-5.

Kreig O. E. et al. 2020. The Interior of the Miniature Vessels. B. Gajdarska (ed.) Early urbanism in Europe: the Trypillia megasites of the Ukrainian forest-steppe. 1. Auflage. Warsaw Berlin: De Gruyter, p. 346–350.

Makarewicz C. A. et al. 2022. Community negotiation and pasture partitioning at the Trypillia settlement of Maidanetske. Antiquity, 96/388, p. 831–847. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2022.32.

18. Mathieson I. et al. 2018. The genomic history of southeastern Europe. Nature, 555/7695, p. 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25778.

19. Ohlrau R. 2020. Maidanets’ke. Development and decline of a Trypillia mega-site in Central Ukraine. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Scorrano G. et al. 2021. The genetic and cultural impact of the Steppe migration into Europe. Annals of Human Biology, 48/3, p. 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460.2021.1942984.

20. Shatilo L. 2021. Tripolye typo-chronology: mega and smaller sites in the Sinyukha river basin (edited by J. Müller). Leiden: Sidestone Press (Scales of transformation, 12).

21. Turek J. 2020. Beer, Pottery, Society and Early European Identity. Archaeologies, 16/2, p. 396–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-020-09406-7.

Videiko M. 2011. The “disappearance” of Trypillia culture. Documenta Praehistorica, 38, p. 373–382. https://doi.org/10.4312/dp.38.29.

Болтенко М. 1926. Кераміка з Усатова. Трипільська культура на Україні, І, p. 8–30.

Збенович В. 1974. Позднетрипольськие племена северного Причерноморья. Киев: Наукова думка.

Ковалева И. 1984. Север степного Причерноморья в энеолите-бронзовом веке. Днепропетровск: Днепропетровский государственный университет.

Круц В. 1993. Питання демографії трипільської культури. Археологія, 3, p. 30–36.

Овчінніков Е., Винагородська Л., Болтанюк П. 2013. Кераміка Кукутень-Трипілля з території Старого Замку (північний бастіон) м. Кам’янець-Подільський. Археологія & Фортифікація Середнього Подністров’я. Кам’янець-Подільський: Видавництво «Медобори-2006», p. 10–16.

Пассек Т. 1949. Периодизация трипольскиx поселений (III–II тыс. до н. э.). Москва; Ленинград: Издательство Академии наук СССР.

Рындина Н. 1998. Древнейшее металлообрабатывающее производство Юго-Восточной Европы (истоки и развитие в неолите-энеолите). Москва: Эдиториал УРСС.

Телегін Д. 1971. Енеолітичні стели і пам’ятки нижньомихайлівського типу. Археологія, 4, p. 3–17.

Шапошникова О., Бочкарев В., Шарафутдинова И. 1977. О памятниках эпохи меди – ранней бронзы в бассейне р. Ингула. Древности Поингулья. Киев: Наукова Думка, p. 7–37.