Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2022, vol. 23, pp. 135–147 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2022.23.8

Elk-boat Depictions in the Ethnoarchaeological Context

Nataliia Mykhailova

Institute of archaeology of NASU, Kyiv

medzie.nataliiamykhailova@gmail.com

Abstract. Numerous depictions of elk-shaped ships are discovered in rock art of the Northern Europe and Siberia, dating from the Mesolithic time to the Bronze age. Usually they are interpreted as Boats of the Deads, connecting the Worlds. The water is the symbol of a border between Worlds in traditional societies. Northern Europe archaeological findings prove that images of the Cervid as a mediator between Worlds and the Boat of the Deads became connected in the Stone Age. Red deer (Cervus Elaphus) remnants were found in burials from the Mesolithic period to the Iron Age. Cemeteries of humans in boats with deer antlers or elk-headed stuffs were discovered at the Mesolithic sites of Denmark (Vedbaeck, Mollegabet) and in Northern Russia (Bolshoy Oleniy Ostrov). Being of a great significance in the mytho-ritual complex of the Stone Age population in Europe, Elk-Boat as the transport between Worlds is preserved in folklore of South-East European people. Mythological motif of the Cervid, sailing on the Sea or the River, with the sleeping maiden on his antlers, is widespread in South and Eastern Europe.

Key words: Mesolithic, Neolithic, Northern Eurasia, rock art, cervidae, cult of the deer, elk-headed boats, boat of the dead.

Elnio formos valčių vaizdavimas etnoarcheologiniame kontekste

Anotacija. Šiaurės Europos ir Sibiro akmenyse ir ant uolų aptikta daug elnio formos laivų atvaizdų, kurie datuojami nuo mezolito iki bronzos amžiaus. Dažniausiai jie interpretuojami kaip mirusiųjų valtys, jungiančios gyvųjų ir mirusiųjų pasaulius. Vanduo yra sienos tarp šių pasaulių simbolis. Šiaurės Europos archeologiniai radiniai rodo, kad elnio, kaip tarpininko tarp gyvųjų ir mirusiųjų pasaulio, atvaizdai atsirado dar akmens amžiuje. Tauriųjų elnių (Cervus Elaphus) liekanų rasta palaidojimuose, datuojamuose nuo mezolito laikotarpio iki geležies amžiaus. Danijos mezolito (Vedbæck, Mollegabet) ir šiaurės Rusijos (Bolshoy Oleniy Ostrov) vietovėse buvo aptikta žmonių kapinių su elnio ragais ar briedžių galvomis. Elnio formos valties kaip transporto priemonės tarp skirtingų pasaulių įvaizdis išsaugotas pietryčių Europos žmonių folklore.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: mezolitas, neolitas, Šiaurės Eurazija, uolų piešiniai, Cervidae, elnio kultas, briedžio galvos formos valtys, mirusiųjų valtis.

__________

Received: 14/11/2022. Accepted: 21/11/2022

Copyright © 2022 Nataliia Mykhailova. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

When complete reconstruction of the holistic ancient ideological system seems impossible, a reconstruction of separate, conservative, universal elements of the ancient worldview is reasonable. As A. Sagalaev, famous anthropologist and investigator of the Northern Asia spiritual culture said “Fundamental ideas of the worldview remained relevant during all cultural genesis” (Cагалаев, 1991, с. 15).

Understanding the events of the primitive spiritual culture requires a comprehensive study of all its manifestations as a single integral system. Comparison of different categories of ethnographical and archaeological data in synchronous and diachronic aspects allows to reconstruct the main elements of cult and its development (Михайлова, 2017, c. 8).

An important category of motifs in Northern European art, found as well in East Asia and North America, is so-called “boat” with an elk-headed prow. Archaeologists A. Okladnikov (Окладников, 1959), V. Ravdonikas (Равдоникас, 1937), A. Lahelma (2005, 2007), J. Coles (1991), and others studied the deer1 cult revealed in rock art, in particular regarding the images of boats with elk heads. I propose the interpretation of “elk-boats” based on cross-cultural analyses, including archaeological, cultural anthropological and folklore studies.

A boat as a means to transport souls of the dead to the afterlife was conceptualized in the ideology of the ancient world from Northern Europe to Southeast Asia, from Egypt to Gobustan (Равдоникас, 1937; Окладников, 1959; Ревуненкова, 1974; Петрухин, 1980; Алиев, 2017). Ethnographic sources on East Asia and Oceania describe funerals of the dead in zoomorphic boats put in the water or sank (Ревуненкова, 1974; Петрухин, 1980). Shamans had the leading role in the ceremony of virtual souls shipping (Ревуненкова, 1974; Анисимов, 1958, c. 58).

One of the most important motifs of the Neolithic and Bronze Age art in Northern Europe is a “boat” with a stem in the shape of an elk’s (Alces alces) head. Such “elk boats” include two symbolic references to Otherworld to be considered: widely accepted concept of a boat as a transport for the souls as well as archetype of Cervid as a guide to the world of the dead. The latter existed in ancient ideology in Eurasia from the Mesolithic period to the Middle Ages.

Archaeology proves this conception to be manifested in funeral rites. “Guide-deer” archetype is represented in two kinds of burial tradition. Appeared in the Mesolithic and existed in the Neolithic, the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, the first one deals with Cervidae burials in cemeteries (Михайлова, 2017, c. 205–208). The second one includes people burials in boats with Cervid features (skin wrap, antlers or elk-headed staffs) (Михайлова, 2017, 189–205; Михайлова и др., 2021).

Depictions of the “elk-boats” in the rock-art

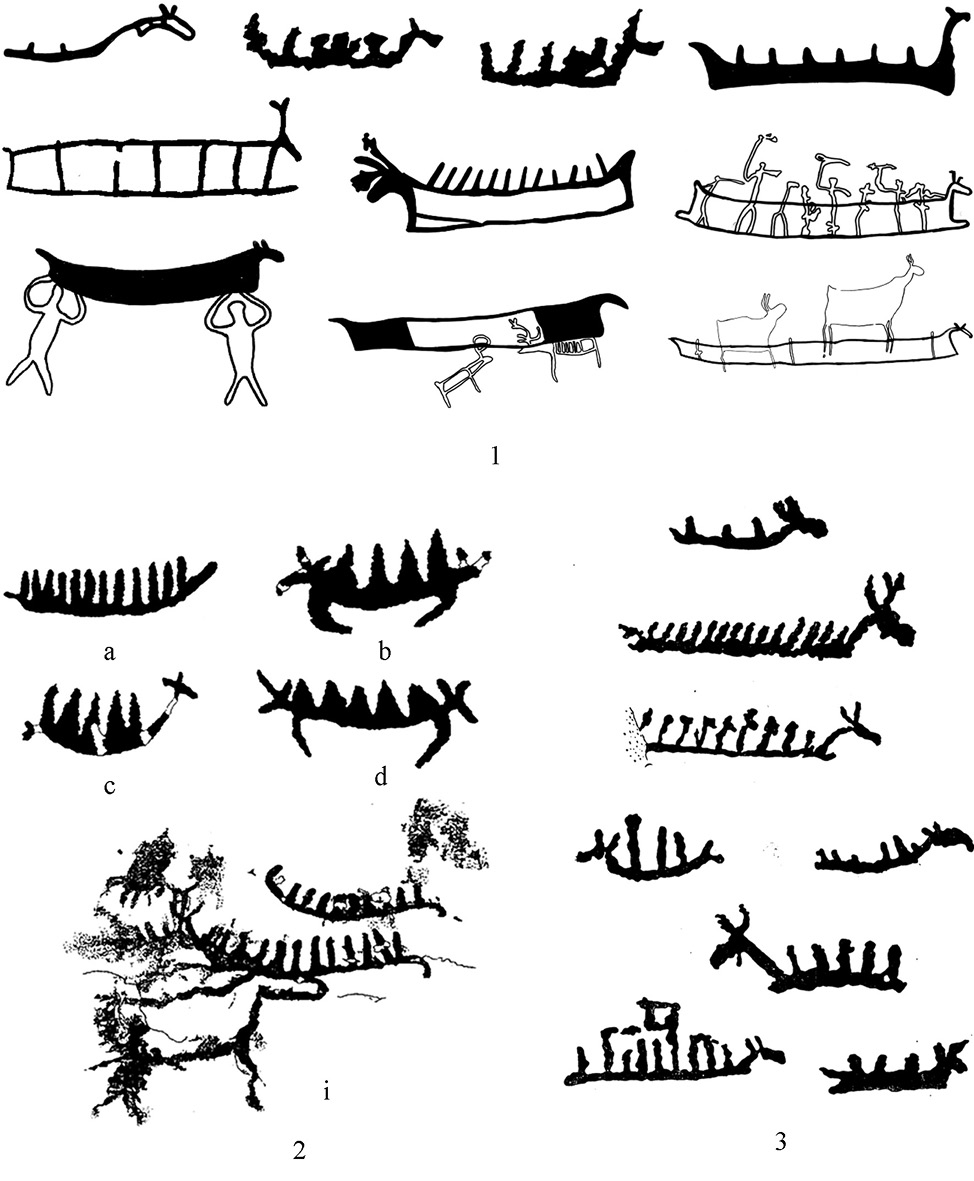

Images of elk-headed boats are most common in Scandinavia, Northern Russia, Siberia, and Chukotka. The most expressive are rock paintings of the Neolithic period in Uittamonsalma in Finland, Pyhäpää in Finland (Lahelma, 2007), Tumlehead and Namforsen (Fig. 1) in Sweden (Coles, 1991, p. 130, fig. 1, p. 135, fig. 7), Neolithic Basinai petroglyphs (Дэвлет, 2005, p. 29, fig. 33), Tom (Дэвлет, 2005, p. 47, fig. 57); Shishkino (Елинек, 1982, p. 486) in Siberia.

Some boats have two “heads”, sometimes with elk leg-like extensions or “tails” at the bottom (рис. 1) (Колпаков, 2012, с. 159). In some cases, elk heads were put on the boat and that resembled antlers (Fig. 1, 2) (Lahelma, 2000, p. 359; Sarvas, 1969, p. 8, аbb. 3). Discovered on the American continent, similar combinations of a boat with semantically important parts of the elk prove archaic origin of the phenomenon (Coles, 1991, с. 139).

Fig. 1. Depictions of the elk-shaped boats, Northern Europe, Bronze Age (by Klem, 2010; Lahelma, 2005; Равдоникас, 1937).

1 pav. Elnio formos valčių vaizdavimas, Šiaurės Europa, bronzos amžius (pagal Klem, 2010; Lahelma, 2005; Равдоникас, 1937)

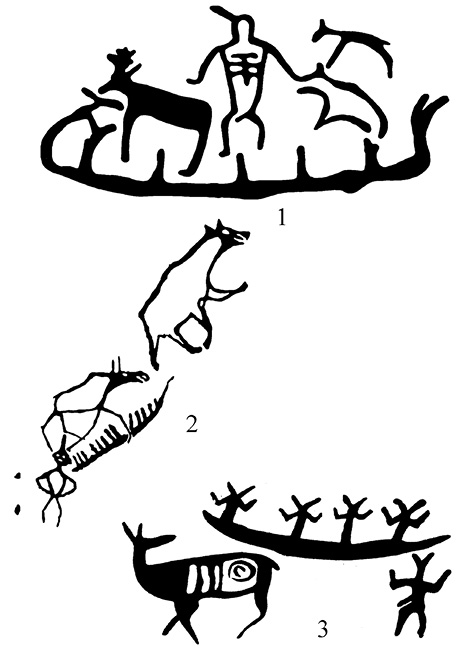

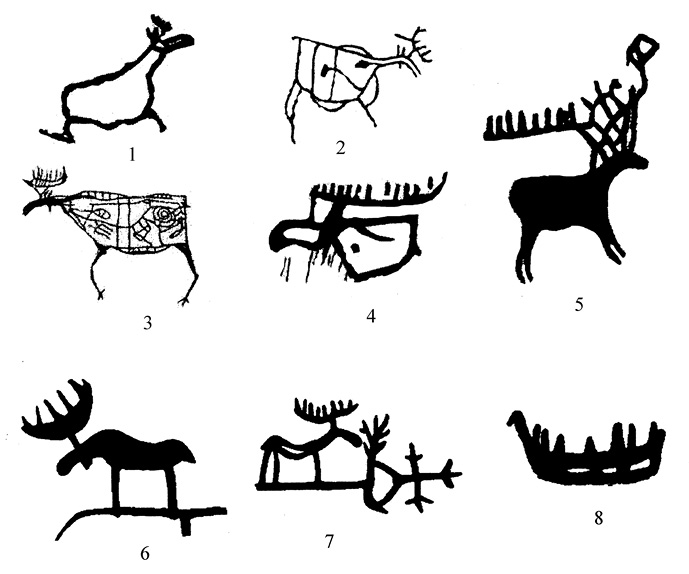

Found in Northern Europe, rock images of “people” on boats, were sketchy, sometimes with “antlers” (Figs. 2, 3) or zoomorphic staffs (Fig. 1, 1). Boats with horned anthropomorphic creatures, accompanied by a deer with a solar sign on hips, occur on the Angara paintings and Shalabolin petroglyphs (Fig. 2, 3) (Дэвлет, 2005, c. 28; Окладников, 1959, p. 100−101; Пяткин и др., 1985, pp. 45, 50, 83, 154). With horns, limbs and phallus, some of these anthropomorphic images are quite realistic (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Depictions of the boats, elks and “shamans”, Siberia, Neolithic (by Дэвлет, 2005; Елинек, 1982).

2 pav. Valčių, elnių ir „šamanų“ vaizdavimas, Sibiras, neolitas (pagal Дэвлет, 2005; Елинек, 1982)

Fig. 3. The motif of the deer as vehicle, Northern Eurasia (by Lahelma, 2007).

3 pav. Elnio, kaip transporto priemonės, motyvas, Šiaurės Eurazija (Lahelma, 2007)

Archaeological evidences

The ancient idea of a deer-mediator is archaeologically proved by deer remains in human burials as well as humans buried with the deer remnants. Human cemeteries with the red deer (Cervus Elaphus) or roe deer (Genus Capreolus) remains appeared in Europe in the Mesolithic. The practice continued in the Neolithic, the Bronze and the Iron ages: Gongehusvej (Petersen, 2003, p. 489−490); Stsheltze (Wislanski, 1960, p. 25−28); Lang-Enzerdorf (Behrens, 1964, S. 62−65); Maryino (Щепинский, 1959, с. 67−72); Ositnyazka (Галанина, 1977, с. 29−32); Hanlar (Гуммель, 1992).

Symbolic meaning of the Deer as a mediator between worlds was revealed in the burial tradition to provide the dead with a deer features: deer skin wrap (Mykhailova et al., 2021), deer antlers (Mykhailova, 2019) or elk-headed staffs (Mykhailova, 2017, p. 202–205).

Burials in the form of boats are commonly discovered in Scandinavia. The earliest Mesolithic “boats” were identified at Skateholm II: IV and some other cemeteries of the same period (Gron, 2015, p. 162). Barks or wooden structures in burials of Northern Europe, usually interpretated as boats, had deer features – namely, in Mollegabet II, Vedbaek (Mesolithic); (Bolshoy Oleny Island) (Bronze age); Riikala (Iron age), Zeleny Yar (Middle ages).

Mollegabet II (Ærø Municipality, Southern Denmark). As O. Gron (2004) described, in spring 1990 a dug-out boat was found at the Mellegabet II settlement site. Like almost all Mesolithic boats the dug-out boat made from a large, straight lime trunk. The base and the partly preserved starboard side, curved towards the stern evenly up to a height of c. 10 cm above the base of the boat, had been carefully shaped with axes down to a thickness of 1.5–2 cm. The bones lay immediately north of the boat and at the same level. They must have been washed out of the boat, as skeletal parts were also found on the bottom of the boat itself in the form of a large fragment of cranium and a finger bone. Two severed upper parts of large red deer antlers and a whole roe deer antler, all showing burin work, were found in the gyttja slightly south and east of the boat‘s stem and at the same level (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Dug-out boat burial. Mollegabet settlement. Reconstruction by J. Kragelund (by Skaarup, Gron, 2004).

4 pav. Iškastas valties palaidojimas. Mollegabet gyvenvietė. J. Kragelundo rekonstrukcija (pagal Skaarup, Gron, 2004)

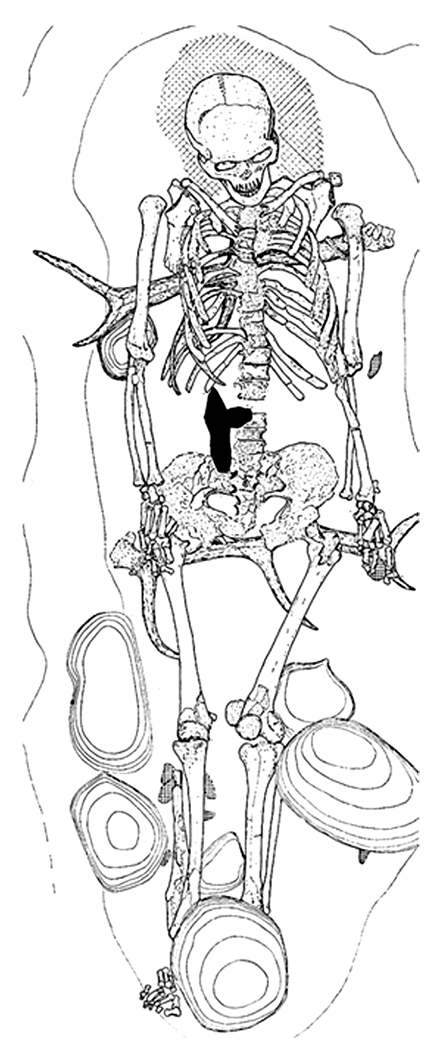

Vedbaeck (Henriksholm-Bøgebakken (Rudersdal Kommune, Denmark). The Mesolithic cemetery at Vedbæk, belongs to the late Kongemose culture and the early Ertebølle culture (4100 BCE). Twenty-two graves were excavated there. Three of them had red deer antlers. The undisturbed grave 10 contained the unusually well-preserved skeleton of a 50-year-old male (Fig. 5). Two large flint blades were found to the right of and just above the pelvis. The deceased had been laid to rest on a pair of red deer antlers, one placed under the shoulders, the other under the pelvis. Five big stones had been placed on the person’s lower extremities. The skull was surrounded by ochre. The undisturbed grave 11 was of the same type as the other burials. A red deer antler, a bone awl, and a shaft-hole axe were found at the bottom. The floor of the grave was colored by ochre, but there were no traces of the interred person. The explanation offered by the excavators is that the detailed stratification of the fill suggests that the body was disinterred shortly after burial. The composition of the grave goods suggests that grave 11 originally contained a man (Alberthsen, 1977).

Fig. 5. Mesolithic Vedbaeck cemetery, burial 10.

5 pav. Mezolitu datuojamas Vedbaeck kapinynas, palaidojimas Nr. 10

According to Petersen et al. (2015) three burials of HB: 10, 11 and 12, placed next to each other in the same row, all three have apparently been buried under individual parts of a turned around wooden dug-out canoe, the onboard hearth of which were discovered next to the pelvic area of HB: 10, when the box for lifting were being constructed around it .

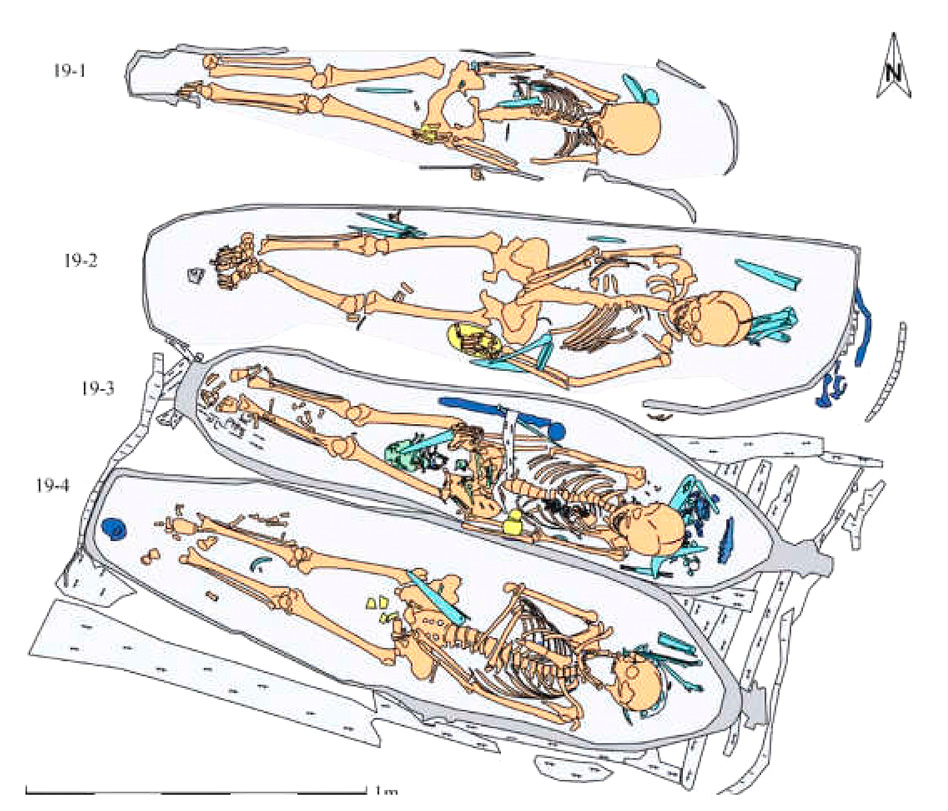

Bolshoy Oleny Island (Barents sea, Russia) burial ground on the shores of the Barents Sea included 32 burials with 40 skeletons dating by the Early Metal Age (Fig. 6). According to Murashkin et al., grave pits were 50 cm deep from the ancient surface, subrectangular in plan, had stone linings of various configurations. Most of the bodies had been buried in wooden, boat-shaped, lidded caskets, which looked like small boats or traditional Sámi sledges (Ru. kerezhka). It seems that the boards of the boats were made of thin wooden planks and were probably tarred. Probably, the dead were transported to the island in them. A ceramic vessel or a sea scallop shell was often placed on the wooden floor above the boats. Parts of animals were found on the upper parts of individual burials – possibly traces of a funeral feast. Other inventory included bone and horn daggers, bone and flint dart and arrowheads, bone needles and piercings, shell strings, hairpins and combs, bone pommels with a stylized image of a reindeer head, bone T-shaped pommels similar to rattles for tambourine (Murashkin et al., 2016). In my mind, the presence among the inventory of a pommels with a deer’s head and a T-shaped rattle testify to the shamanic status of some of the buried.

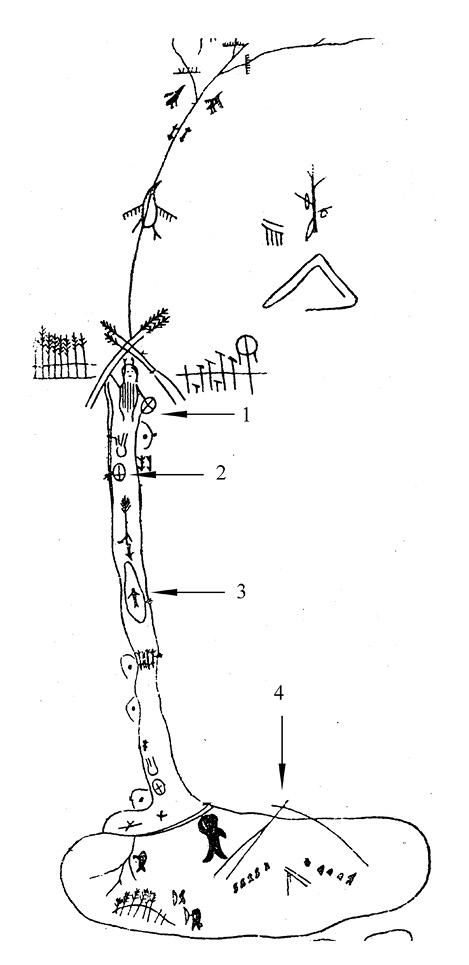

Fig. 6. The shaman transports the soul to the camp of the dead. Evenkian drawing. Siberia, Russia, XX cen. 1 – The shaman in the antlered crown; 2 – Shaman’s drum, which symbolize a boat; 3 – dead man; 4 – camp of the Dead (after Анисимов, 1958).

6 pav. Šamanas gabena sielą į mirusiųjų stovyklą. Evenkų piešinys. Sibiras, Rusija, XX a. 1 – šamanas su ragų karūna; 2 – šamano būgnas, simbolizuojantis valtį; 3 – miręs žmogus; 4 – mirusiųjų stovykla (pagal Анисимов, 1958)

Bronze Age boats in burials were imitated with stones arranged in the shape of a ship. Later, Viking Age wooden boats were used for noble burials (Shetelig, 1937, p. 151−152, 279−282). Iron Age burials in boats are known in the grave 7, Rikala Halikko complex in Finland (Михайлова и др., 2021).

One of the best-preserved examples of boat burials in Northern Eurasia is Zeleny Yar cemetery, Siberia (Slepchenko et al., 2019), dating back to 12–13 centuries AD. Fragments of clothing and footwear made of reindeer fur, burial masks made of birch bark and fur, and bronze anthropo- and zoomorphic figurines were discovered. The bodies were wrapped over their clothes in deer skin blankets. Burial structures made of birch bark or wood are supposed to be boats. The combination of animal skins and decks imitating boats in the burials of Rikala and Zeleny Yar acquires a special meaning (Зеленый Яр, 2005, 221; Михайлова и др., 2021).

Ethnographical materials. To understand the meaning of the images of elk-like boats we propose to address mythology. Numerous Northern Eurasia people’s mythology shows the deer as the ruler of the Otherworld.

The main characters of Nganasany mythology are giant reindeer females: Earth-Mother and Subterranean Ice Mother. The body of this Deer is the Land of Deads (Долгих, 1968, 217). The spirit of the lower world in Evenki mythology, Kalir, appears in the image of a wild male reindeer (Топоров, 1980). In the mythology of the Altai people there is a giant reindeer, who lives in the depths of the lake and symbolize the World Ocean (Окладников, 1950, 293). The Dolgany people believed, that a giant reindeer lived under the Earth (Окладников, 1950, 293). The bizarre elk of the Lower World in American Indian legends stands in the river and swallows everyone who descends this river (Окладников, 1950, 293, 294).

The global “deer-boat” motif allows to assume that its origin dates back to the time of the settlement of America, i.e., the Final Paleolithic. Indirect evidences of the ancient origin of this mythologeme can also be found in rock art discovered in Korea (Jang, 2005, p. 235).

So, numerous mythological mentions of the deer connected with the Lower World prove it was associated with a giant Deer in archaic societies of hunters-gatherers. This animal “swallow” the souls of the dead for to get them reborn in the world of humans. Also, according to hunting beliefs, the annual revival of antlers was supposed to contribute to the revival of the dead. The mentioned above facts caused the image of the Deer as a guide to the world of the dead to preserve in times.

We should also regard the indirect evidences that underline the deep root of the concept. Thus, prehistoric origin of the mythologeme of the deer as the ruler of the lower world survived in the similar idea, popular among the peoples of Europe in the Iron Age to the Middle Ages, when the deer was viewed as a guide to the World of the Dead as well (Даркевич, 1988, c. 109; Пропп, 2000, c. 290).

With the evolution of mythology, the image of the “Underground Deer” probably succeeded the features of a guide to the “Other World”. The motif of a “boat of the dead” with a similar function was imposed on it.

Relics of the concept of the red deer as a guide to the Otherworld was kept in the consciousness of many Eurasian peoples, especially peoples of Eastern and Central Europe, till nowadays. Ukrainian, Romanian, and Moldavian folklore motifs, where the deer appears, are mentioned in the works of M. Gimbutienė (1991), A. Poruchich (2011), L. Vinogradova (Виноградова, 1982), O. Naiden (Найден, 2005), L. Antokhi (Антохі, 2010).

This is the motif of a Deer floating on the sea with a cradle on its horns, in which a maiden or a lad lies, and the motif of a hut made from deer bones.

To begin with, let us consider a story about a deer that swims in a river or sea and carries a girl or a boy on its horns that, among others, can be found in some Ukrainian traditional songs as well:

“Oh, beyond the mountain, beyond the green, the river flows, carries overflows. In that overflows gray deer goes, He has a rocking cradle on his horns, in that cradle a nice maiden is spleeping” (Найден, 2005, с. 180; Сумцов, 1890, с. 67). Romanian carols “for the dead” mention a deer floating on the sea with a silk swing on its horns. A dead girl, sitting in it, sewing or embroidering a canvas, asks the deer not to drop her into the water (Виноградова, 1982, p. 163). Here is another similar plot with a plate on the deer’s horns and a man on it: “The Danube dried up, overgrown with herbs. Strange beast saves herbs, gray deer saves herbs. On that deer – 50 horns, 50 horns – one plate, on that plate ... gentle fellow” (Найден, 2005, 180).

The motif of a cattle floating on the sea / river and carrying a girl on its horns is also well known in Romania. Usually this is a bull or an aurochs, who plays the important role of a cult animal in agricultural societies (Porucic, 2011, 18).

M. Gimbutienė stated that the most archaic variants of the motif describing a girl lying on the deer’s horns were spread in the south-western regions and the Romanian Carpathians. It is presented in the Romanian Kolinda, which was first studied by A. Poruchich (2011). M. Gimbutienė published it in her monograph “The Language of the Goddesses” (1991). The plot is also based on a deer swimming with a cradle on its horns. A girl lying in a cradle asks her brothers to kill a deer, build a palace from its remnants and prepare a wedding dinner from his meat.

There is a widespread opinion that the motif of traveling by water indicates the transition from the world of the living to the world of the dead. In the Saami myth, the Human world is separated from the Animal world by the bloody river with the waves from the lungs and stones from the liver (Чарнолусский, 1968, с. 35).

The concept of the boat as a vehicle for transporting dead souls to the afterlife in the ancient world’s ideology is stable and widespread from Northern Europe to Southeast Asia, and from Egypt and Gobustan (Равдоникас, 1937; Алиев, 2008). According to ethnographic sources, many peoples of East Asia and Oceania buried their dead persons in zoomorphic boats, lowering them into the water or flooding (Петрухин, 1980; Ревуненкова, 1984).

In some versions of Ukrainian folk songs there is a tower built on the horns of a deer: “Do not bend the beech bridge, aurochs and deer are going on you. A high tower is on those deer. And in that tower the Nice Maiden sewed – embroidered a shirt to the father” (Vinogradova, 1982).

“Oh, you are a nine-horned deer; on the tenth horn a tower was built. And in that tower is a new room, And in that room a gentle lord sits” (Найден, 2005, 180).

According to N. Chausidis, there are mythical representations mentioned from all over the world regarding crossing the mythical bridge conceived in its cosmological dimension – as communication through the cosmic horizons (sky-earth-underworld) (Чаусидис, 2012).

The motif of a building made of deer bones is also common in Ukrainian and Moldavian folklore: “He covered his house with its skins; He built a living room from its ribs. He made a wedding dinner with its meat. He made cups of its horns” (Антохі, 2010, 27). In both building cases, the deer remnants are associated with the wedding.

In some songs the room is marked with the skin and horns of a sacrificial deer:

“– Oh, I know what I’m making noise, Because I have a strange beast, A strange beast, a gray deer, That deer has seventy horns. There you have me, there you will kill me! You will take off from me a gray hide coat, a gray hide coat, and antlers. You will bring the antlers to the new room” (Найден, 2005, 83).

Its purpose is mentioned in folklore of the neighboring peoples. Lithuanian ritual songs associated with the solstice (and possibly a time of adolescent initiations) features a deer with nine antlers. It had a tenth horn, with a house on it, music played and young people dancing inside (Dundulienė, 1990, p. 49). In the Serbian prayer to “lifeless” a protagonist was sent to enter the head of a deer to become as “kind and patient as a deer” (Бернштам, 1990, 36). Both cases presumably describe age-related initiations. Such adolescent initiations also gave right to marriage. The image of a deer is also associated with the motif of marriage in the East Slavic peoples’ folklore. In the Slavic song a deer says: “You will get married, I will come to the wedding; I will bring golden horns with me; I will light the whole yard with golden horns; I will cheer up all your guests; Moreover – I will cheer up your bride” (Потебня, 1865, p. 38).

Building made of deer bones and skins, mentioned in songs of the peoples in Central and Eastern Europe, reveals of the idea of a zoomorphic construction, used for adult initiation rites (a beast-hut by V. Propp). Preserving the oldest hunting cycle of myths about deer people (Myandash), Sámi mythology would help to better discover this motif. The main character of the series is Myandash-parn (guy), a Sámi culture hero. The protagonist travels between worlds during “transitional rites”. In a myth about Myandash, the travel from the Animal World to the Human World is connected with the house from the bones and skins of a deer: “Here, mother, let us live in a tower made of deer skins: the threshold will be the link of the cervical vertebrae , the roof boards of the ribs, the bars of the deer’s legs , and a clean place we will cover with a vertebral bone, and let the stones of the hearth be as smooth as the liver. He has turned over and took on a human form” (Чарнолусский, 1969, с. 37). When the deer entered the house, it acquired human features – that is, it passed into the Human world. Probably, it is a zoomorphic building, where the rites of age initiations were performed, that’s the transition to the status of adults. The zoomorphic building indicates a totem animal’s sign.

Therefore, the given plots might have elements of both funeral and marriage rites.

So, the deer is a transport between worlds, and the tower on deer antlers symbolizes a zoomorphic building.

Discussion

There are several interpretations of the semantics of elk boats. After A. Lahelma (2007), O. Almgren (1927), linked the boats with the solar cult, the cult of fertility and, consequently, with the cult of the god who dies and rises. V. Ravdonikas (Равдоникас, 1937), focusing on the images found in Karelia, proposed the semantic formula “deer-sun-boat” to symbolize the transportation of people to the world of the dead. The researcher discovered the connection of these images with the “sun boats” of ancient Egypt. A. Okladnikov adheres to the version of the sailing of the dead souls to the afterlife. He complements it with ethnographic data about the deer as an inhabitant of the underworld among the peoples of Siberia (Окладников, 1959, c. 103–104). According to Vastokas and Vastokas (1973: 126–127), the image of a sun-boat in northern circumpolar religious imagination arises when the notion of the soul-boat is brought into association with another central shamanistic motif, the Cosmic Tree or Axis. The boat may thus refer to travel on the horizontal plane, but also to the vertical axis: the celestial journeys of the shaman. The presence of the boat-antlered elk in the art led Taatvitsainen (1979, 191) to suggest, that all boat-figures in Finnish painting should in fact be interpreted as elk antlers (after Lahelma, 2007).

Using ethnographic materials of Saami and Siberian peoples, A. Lachelma (2017) proposes a hypothesis, that elk-head boats are the vehicles for the shaman to travel between the worlds. H. Bolin (2010) suggests, that depictions of the elk-boats indicate traveling of the mythical ancestor. However, all researchers are united in thought that the “boats” have mostly ritual significance.

In our opinion, the “boat” with more or less expressed elk/deer features is a syncretic mythological image that played the role of a mediator between the worlds. A detailed image of an elk head with horns and an earring (Kolpakov, 2012, p. 159) and also with the tail signifies that it is the mythical creature “elk-boat” depicted, not a boat decorated with elk prow (Fig. 1). The combined images of boats with horned people and solar signs deserve special attention (Figs. 2, 3). Apparently, these petroglyphs depict a mythological journey to the Otherworld of people who, after death, took on a zoomorphic appearance.

Therefore, regarding the rock art plots and myths of the peoples of Northern Eurasia, we can assume that the main elements of the myth about boats with deer features, used to transport people to the land of the dead, were formed as early as in Mesolithic–Neolithic times.

This hypothesis completely correlates with the well-known traditional idea of water as a boundary between worlds (Мириам, 2000; Niederle, 1912, 265–266; Успенский, 1982, 56).

The connection of shamans, as mediators between worlds, with the boat that served as their transport is indisputable in the ethnographic literature (Анисимов, 1958, c. 58; Lahelma, 2005, p. 359–362; Ревуненкова, 1984). Shaman “transported” souls of the dead down the river (Fig. 7). Among Siberian and North Asian shamans, frame drum also embodies a shaman’s boat (Анисимов, 1958, p. 58). Manchu shaman Nishan journey to the Otherworld is described in a particular way:

“Together with the spirits, she went to the land of the dead. Finally, we reached the Red River. There she saw neither a boat nor a boatman. Then she threw her drum into the water and stood on it. And at one point she flew across the river” (according to Hoppal, 2015, p. 80).

The idea of an “elk-boat” mythical syncretic creature as a contact provider between the world of the living and the world of the dead is also proved by archaeological and ethnographical data (Oкладников, 1959, p. 103–104; Lahelma, 2005, p. 359−362). Souls could cross the border between the worlds – namely, some water – guided by shamans who were probably depicted by ancient hunters with elk staffs in boats. People buried with deer antlers or elk-headed staffs, dated back to the Mesolithic-Neolithic times, might be archaeological evidence for this spiritual concept.

Fig. 7. Oleniy Ostrov cemetery.

7 pav. Oleniy Ostrov kapinynas

Conclusions

Traces of the ancient hunting beliefs are preserved in folklore of the South-Eastern Slavs and neighboring peoples. The sacral ideology appeared in the Mesolithic and Neolithic ages, when the deer played an extremely important role in the economy of Northern Eurasia.

The origin of this concept can be found both in ethnographic data of the Northern peoples and archaeological materials from the Northern Eurasia.

Originated in the Stone Age, the idea of the Deer as a mediator between Worlds was of great significance for Northern Eurasian hunters-gatherers. It was performed in the burials with deer features (skins, antlers elk-headed staffs) and deer skeletons in the graves.

In the coastal areas of Northern Europe and Asia, the image of the elk as a mediator was imposed on the boat archetype as a vehicle for transporting people to another world. As these two iconographic plots merged, the image of a fantastic creature combining boat and deer features appeared. The deer-boat concept is extremely common in Northern Europe, North Asia, it often can be found in Korea and North America.

Reminiscences of initiation rites of Stone Age European deer hunters are mentioned in folklore of Northern, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe peoples, such as Ukrainians, Moldovans, Romanians, Serbs, Lithuanians, and others.

The list of literature

Albertsen S., Petersen E. 1976. Excavation of a Mesolithic cemetery at Vedbaek. Acta Archaeologica, 47/1, p. 1–151.

Almgren O. 1934. Nordische Felszeichnungen als religiöse. Urkunden Frankfurt am Main.

Behrens H. 1964. Cervidenskelette aus der steinzeit und fruhen Metallzeit Europas. Eine kulturgeschichtliche Studie. Varia archeologia, p. 62–65.

Bolin H. 2010. The Re-generation of mythical messages: rock art and storytelling in Northern Fennoscandi. Fennoscandia archaeological, XXVII, p. 21–34.

Coles J. M. 1991. Elk and Ogopogo. Belief system in the hunter–gatherer rock art of Northern Lands. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Societies, 57/1, p. 129–149.

Dundulienė P. 1990. Senovės lietuvių mitologija ir religija. Vilnius: Mokslas.

Gimbutas M. 1991. The Language of the Gods. London: Harper and Roe.

Helskog K. 1987. Selective depictions. A study of 3,500 years of rock carvings from Arctic Norway and their relationship to the Sami drums. J. Hodder (ed.) Archaeology as long-term history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 17–31.

Jang S. H. 2005. Prehistoric painting of Whale-hunting in Korean Peninsula: Petrogliphs at Daedok-Ri. E. Дэвлет (ed.) Мир наскального искусства. Сборник докладов международной конференции. Москва: Институт археологии РАН, c. 355–359.

Lahelma A. 2005. The boat as a symbol in Finnish rock art. E. Дэвлет (ed.) Мир наскального искусства. Сборник докладов международной конференции. Москва: Институт археологии РАН, c. 359–363.

Lahelma A. 2007. ‘On the Back of a Blue Elk’: Recent Ethnohistorical Sources and ‘Ambiguous’

Lahelma A. 2017. The Circumpolar Context of the ‘Sun Ship’ Motif in South Scandinavian Rock Art. P. Skoglund, J. Ling, U. Bertilsson (eds.) North Meets South. Theoretical Aspects on the Northern and Southern Rock Art Traditions in Scandinavia. Oxford – Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, p. 144–171.

Murashkin A., Kolpakov E., Shumkin V., Khartanovic V, Moiseev V. 2016. New sites, new methods. The Finnish Antiquarian Society. ISKOS, 21, p. 185–199.

Mykhailova N. 2019. ‘Shaman’ burials in prehistoric Europe. J. Kokh and W. Kierlis (eds.) Gender Transformations in Prehistoric and Archaic Societies. Leiden: Slidestone Press, p. 341–362.

Petersen E. B., MeikleJohn C. 2003. Three Cremations and a Funeral: Aspects of Burial Practice in Mesolithic Vedbaek. L. Larsson (ed.) Mesolithic on the Move. Oxford: Oxbow Books, p. 487–494.

Petersen E. 2015. Diversity of Mesolithic Vedbaeck. Acta Archaeologica, 86/1, p. 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0390.2015.12048.x

Porucic A. 2011. Prehistoric roots of the Romanian and South-East European traditions. Institute of Archaeomythology.

Sarvas P. 1969. Die felsmalerei von Astuvansaalmi. Suomen Museo, 76, p. 5–34.

Shetelig H., Falk Н. 1937. Scandinavian archaeology. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press.

Skaarup J., Gron O. 2004. A submerged Mesolithic settlement in Southern Denmark. BAR International Series, 1328.

Slepchenko S. M., Gusev A. V., Svyatova E. O., Hong J. H., Oh C. S., Lim D. S. et al. 2019. Medieval mummies of Zeleny Yar burial ground in the Arctic Zone of Western Siberia. PLoS ONE, 14/1, e0210718. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210718.

Stone Age Rock Art at Pyhänpää, Central Finland. Norwegian Archaeological Review, October, p. 113–137.

Taavitsainen J.-P. 1978. Hallmaclningarna: en ny synvinkel pa Finlands forhistoria. Antropologi i Finland, 4, p. 179–195.

Vastokas J. M., Vastokas R. K. 1973. Sacred Art of the Algonkians: A Study of the Peterborough Petroglyphs. Peterborough, Ontario: Mansard Press.

Wislanski T. 1960. Sprawozdanie z prac Expedicji Wykopaliskowej w Strzelach, pow. Mogilno, w 1957 r. Sprawozdania archeologiczne, s. 23–30.

Алиев В. 2008. Духовный мир конных и лодочных охотников эпохи бронзы Азербайджана. “Irs – Heritage – Наследие”, 36, с. 21–24. www.irs-az.com/new/ru/archive/765

Анисимов А. Ф. 1958. Религия эвенков в историко-генетическом изучении и проблемы происхождения первобытных верований. Москва–Ленинград: Издательство АН СССР.

Антохі Л. 2010. Різдвяно-новорічний календарний фольклор українців та молдован на території Бесарабії. Available at: http://philology.knu.ua/files/library/folklore/35/5.pdf.

Бернштам Т. А. 1990. Следы архаических ритуалов и культов в русских молодежных играх «Ящер» и «Олень» (опыт реконструкции). Б. Н. Путилов (ed.) Фольклор и этнография. Проблемы реконструкции фактов традиционной культуры. Ленинград: Наука.

Богораз-Тан В. Г. 1939. Чукчи. Ч. ІІ. Религия. Ленинград: Издательство Главсевморпути.

Виноградова Л. Н. 1982. Зимняя календарная поэзия восточных и западных славян. Москва: Наука.

Галанина Л. К. 1977. Скифские древности Поднепровья (Эрмитажная коллекция Н. Е. Бранденбурга). САИ. – Вып. Д1–33. Москва: Наука.

Гуммель Я. И. 1992. Раскопки к юго–западу от Ханлара в 1941 г. ВДИ, 4, с. 5–15.

Даркевич В. П. 1988. Народная культура средневековья. Светская праздничная жизнь в искусстве IX–XVI вв. Москва: Наука.

Долгих Б. О. 1951. Обрядовые сооружения нганасанов и энцев. КСИЭ, 1, c. 8–14.

Дэвлет Е. Г., Дэвлет М. А. 2005. Мифы в камне. Е. Дэвлет (ed.) Мир наскального искусства России. Москва: Алетейа, c. 75–79.

Елинек Я. 1982. Большой иллюстрированный атлас первобытного человека. Прага: Артия.

Зеленый Яр. Археологический комплекс эпохи средневековья в Северном Приобье. 2005. (Н. В. Федорова ред.). Екатеринбург; Салехард: УРО РАН.

Колпаков Е. М., Шумкин В. Я. 2012. Петроглифы Канозера. Санкт-Петербург: Искусство России.

Леви-Брюль Л. 1930. Первобытное мышление. Москва: Атеист.

Мириам М. 2000. Славянские народные верования о воде как границе между миром живых и миром мертвых. Славяноведение, 1.

Михайлова Н. Р. 2017. Культ оленя у стародавніх мисливців Європи та Північної Азії. Київ: Стилос.

Михайлова Н. 2021. «Човни мертвих» та поховання у човнах: міграція і трансформація ідеї оленя-провідника. Наукові студії. Винники – Жешув – Львів: Каменяр.

Михайлова Н. Ремінісценції первісного культу оленя у фольклорі України й Центральної та Східної Європи. А. Пирожков, А. Загородній, Г. Скрипник (eds.) ІХ Міжнародний Конгрес україністів. Фольклористика. Українознавство. Збірник наукових статей. НАНУ, МАУ, ІМФЕ ім. М. Рильського. Київ, 2019, с. 114–124.

Михайлова Н. Р., Киркинен Т., Маннермаа К. 2021. Погребения в шкурах лося и северного оленя в железном веке и раннем средневековье в Северной Европе: этно-археологический аспект. Stratum +, 5, c. 295–308.

Найден О. С. 2005. Образ воїна в українському фольклорі: семантичні та образні аспекти. Київ: Стилос.

Окладников А. П. 1950. Неолит и бронзовый век Прибайкалья. Материалы и исследования по археологии СССР, 18.

Окладников А. П., Запорожская В. Д. 1959. Ленские писаницы. Наскальные рисунки у деревни Шишкино. Москва; Ленинград: Издательство АН СССР.

Петрухин В. Я. 1980. Погребальная ладья викингов и «корабль мертвых» у народов Океании и Индонезии (опыт сравнительного анализа). Л. Н. Жуковская, Г. Г. Стратанович (eds.) Символика культов и ритуалов народов зарубежной Азии. Москва: Главная редакция восточной литературы.

Потебня А. П. 1865. О мифическом значении некоторых обрядов и поверий. Xарьков.

Пропп В. Я. 1986. Исторические корни волшебной сказки. Ленинград: Издательство ЛГУ.

Пяткин Н. Б., Мартынов А. И. 1985. Шалаболинские петроглифы. Красноярск: Изд-во Краснояр. гос. ун-та.

Равдоникас В. И. 1936. Наскальные изображения Онежского озера и Белого моря. Труды института антропологии, археологии и этнографии, ІХ, с. 138–150.

Равдоникас В. И. 1937. Элементы космических представлений в образах наскальных изображений. Советская археология, 4, c. 11−32.

Ревуненкова Е. В. 1984. «Корабль мертвых» у батаков Суматры. Сборник Музея антропологии и этнографии, XXX, c. 293–306.

Сагалаев А. М. 1991. Урало-алтайская мифология. Символ и ритуал. Новосибирск: Наука. Сибирское отделение.

Сумцов Н. Ф. 1890. Культурные переживания. Киевская старина.

Топоров В. Н. 1980. Древо Мировое. С. А. Токарев (ред.) Мифы народов мира: Энциклопедия в 2 т. Москва: Советская Энциклопедия, т. 1, c. 398–406.

Успенский Б. А. 1982. Филологические разыскания в области славянских древностей. Москва.

Чарнолусский В. В. 1965. Легенда об олене-человеке. Москва: Наука.

Хоппал М. 2015. Шаманы – Культуры – Знаки. Sator, 14. Тарту. Available at: http://www.folklore.ee/rl/pubte/ee/sator/sator14/

Чаусидис Н. 2012. Премин преку тесниот мост – меѓу митот, обредот и циркуската точка. Poznańskie Studia Slawistyczne, 2. Poznań: Adam Mickiewicz University Press.

Щепинский А. А. 1959. Культ животных в погребениях эпохи бронзы в Крыму. КСИА, 9, c. 67–72.

САИ – Свод археологических источников

КСИЭ – Краткие сообщения Института этнографии СССР.

КСИА – Краткие сообщения Института археологии Академии Наук СССР

1 The word “deer” refers to the Cervidae family, which owns 51 species, including elk (Alces alces), reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), red deer (Cervus elaphus) and so on.