Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2023, vol. 24, pp. 19–33 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2023.24.2

Mykola Makarenko and Mariupol Neolithic Burial Ground The tragic fates of the archaeologist and the site

Nataliia Mykhailova

Institute of Archaeology of NASU, Kyiv, Ukraine

medzie.nataliiamykhailova@gmail.com

Abstract. Mariupol Neolithic burial site, unique by its exclusive rich and diversiform inventory, was excavated by Ukrainian archaeologist and art critic Mykola Makarenko in 1930. The author of the excavations was executed by Soviet punitive authorities. The top-level and highly informative publication of the materials on the cemetery, made in 1933, was confiscated. Part of the burial inventory was taken to Russia. Anthropological materials were destroyed during World War II.

The tragedy of Mariupol Cemetery continued in 2022. This was the year which became the tragedy in the history of Ukraine and inherently influenced the history of Europe. The Ukrainian people, the Ukrainian nature, and the Ukrainian culture suffered irretrievable losses. So did Ukrainian archaeology.

Hundreds of archaeological sites in the war zone, in the zone of occupation and in the annexed territories were completely destroyed or irreparably damaged. Among them, there were the scant surviving artifacts from Mariupol Cemetery.

This article is devoted to the history of excavations of Mariupol Burial Complex and the tragic fate of the collection of artifacts.

Keywords: Neolithic, Mariupol Cemetery, burials, Mariupol-type burial grounds, cultural heritage.

Mykola Makarenko ir Mariupolio neolitinis kapinynas. Tragiškas ukrainiečio archeologo ir vietovės likimas

Anotacija. Išskirtiniu turtingu ir įvairialypiu inventoriumi unikalų Mariupolio neolito laikų kapinyną 1930 m. kasinėjo ukrainiečių archeologas ir menotyrininkas Mykola Makarenko. 1933 m. buvo parengtas iš išleistas informatyvus kapinyno tyrimams skirtas leidinys, tačiau visas tiražas greitai buvo konfiskuotas. Dalis kapinyno inventoriaus išvežta į Rusiją. Antropologinė medžiaga sunaikinta Antrojo pasaulinio karo metais. 1938 m. kasinėjimų autoriui sovietų baudžiamoji valdžia paskyrė mirties bausmę.

Mariupolio kapinyno tragedija tęsėsi ir 2022 m., kurie tapo tragedija Ukrainos istorijoje ir paveikė visos Europos istoriją. Ukrainos žmonės, gamta, kultūra patyrė nepataisomų nuostolių. Taip pat ir Ukrainos archeologija. Karo zonoje, okupacinėje zonoje ir aneksuotose teritorijose buvo sunaikinta arba stipriai sužalota šimtai archeologinių vietovių.

Straipsnis skirtas Mariupolio laidojimo komplekso kasinėjimų istorijai ir tragiškam artefaktų kolekcijos likimui.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: neolitas, Mariupolio kapinynas, palaidojimai, Mariupolio tipo kapinynai, kultūros paveldas.

________

Received: 22/12/2023. Accepted: 29/12/2023

Copyright © 2023 Nataliia Mykhailova. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

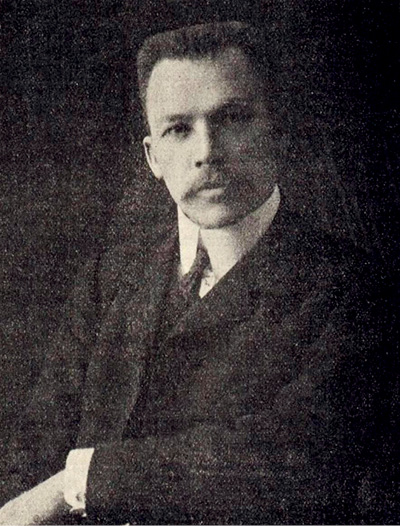

Mariupol Neolithic Cemetery was one of the most prominent burial complexes in Ukraine and Eastern Europe. Unique in its wealth and variety of inventory, the site was thoroughly researched; the materials were processed and published by Mykola Makarenko (Макаренко, 1933) (Fig. 1). The Mariupol Cemetery artifacts were so significant for Ukrainian archeology that the name of the site has lately been used to designate a type of a burial complex which was widespread in the late Mesolithic and Neolithic periods in the areas from the interfluve of the Prut and the Dniester rivers to the Don River.

Fig. 1. Mykola Makarenko (https://www.facebook.com/khanenkomuseum/posts/10159661228764162/).

1 pav. Ukrainiečių archeologas Mykola Makarenko (https://www.facebook.com/khanenkomuseum/posts/10159661228764162/)

There are about 30 Mesolithic and Neolithic cemeteries of the so-called Mariupol type, with most of them being located along the Lower Dnipro (Dnieper) Rapids. Mariupol-type burials can be assigned to two periods: the early Mariupol type: 7000–5500 BC, and the late Mariupol type: 5500–4000 BC (Telegin et al., 1987). According to anthropological research, the populations of the Middle Dnipro region mostly belonged to the Proto-European Europeoid race, also known in the craniological series of the Mesolithic burial grounds of Vedbaek in Denmark and Skateholm in Sweden (Потехина, 2006). This group is considered to have originated in the Baltic area with further migration to the Ukrainian territories.

Numerous deceased from the Mariupol-type cemeteries were accompanied with rich burial inventories. Burials of the later phase of the Mariupol-type cemeteries are characterized by outstanding abundance and variety of the grave findings. The most impressive personal ornaments are perforated boar tusks. The plurality of these decorations in Mariupol Cemetery determines the uniqueness of this funeral complex.

History of research

The funeral rite of Mariupol Neolithic Cemetery has been profoundly studied in Ukraine and Europe. The burial complex was discovered and excavated by Mykola Makarenko in 1930 on the Azov Sea shore, near Mariupol, Donetsk Region. The great number of artifacts from Mariupol Cemetery were thoroughly studied and described in his immediately written monograph (Макаренко, 1933).

The burial rite and the stratigraphy of the burial ground were systematically analyzed by Abram Stolyar, who identified the site as a unified cultural-historical complex (Столяр, 1955). The cultural organization, chronology, and periodization of Mariupol-type burial grounds were studied by Nadiia Kotova, who also reconstructed ancient burial clothes by means of burial goods (Kotova, 1994; 2010). The anthropological composition of Mariupol burial grounds was researched by Dmytro Telegin, Inna Potekhina and Malcolm Lillie (Telegin et al., 2002; Potekhina, 1999). The author of the present paper has been investigating the personal ornamentation of Mariupol-type cemeteries (Михайлова, 2019; 2020; Mykhailova, 2020).

Backstory

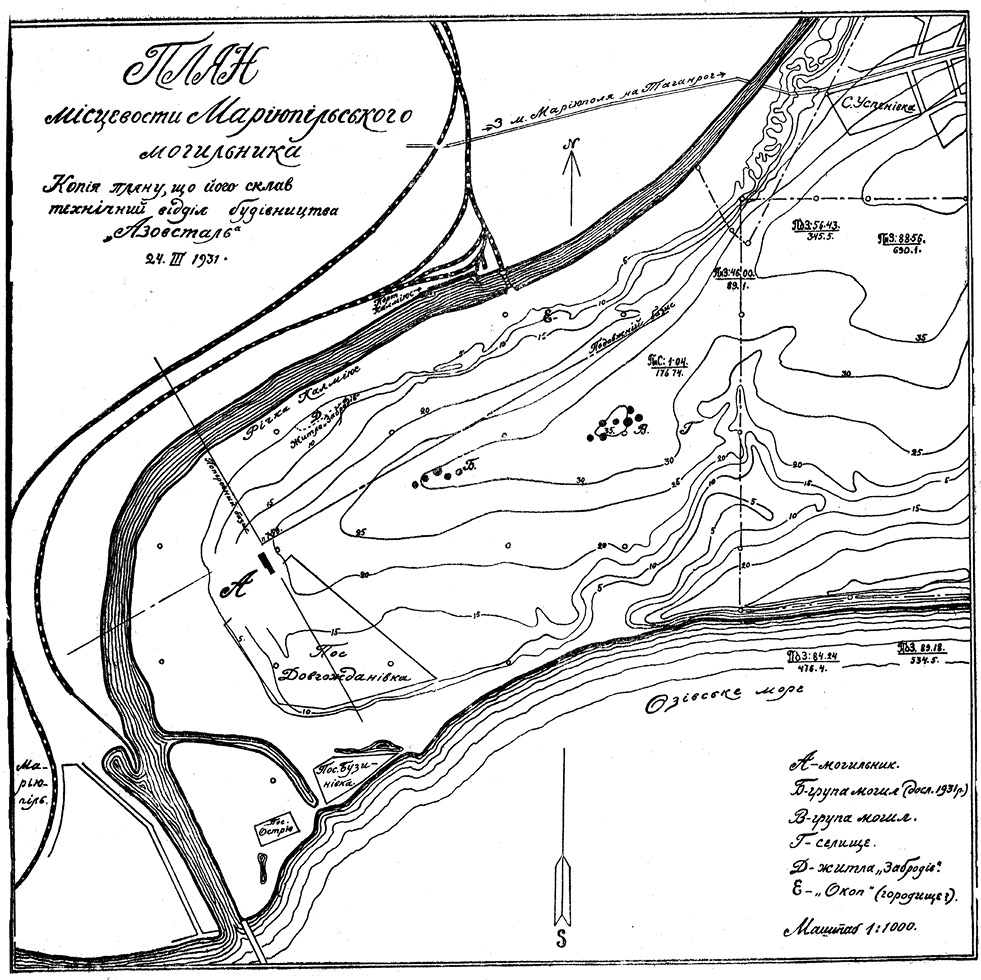

Mariupol Cemetery was discovered in the 1930s in the suburbs of Mariupol, a Ukrainian city on the shores of the Sea of Azov, with a long and glorious history. The location of Mariupol (Fig. 2) in the delta of the small Kalmius River was extremely convenient for settlements throughout the times, starting with the Neolithic Period. The first fortified settlement on the site of modern Mariupol appeared at the mouth of the Kalmius River in the 17th century. Zaporozhian Cossacks built a fortified outpost at the mouth of the Kalmius River, on the site of the Venetian-Genoese settlement of Adomakh (Domakha). From 1594 to 1768, Domakha Fortress was the center of Kalmius Palanka (military settlement). Its aim was to protect the winter farms, fishing places, and communication routes of the Zaporozhian Cossacks from the attacks of the Crimean Tatars. City construction on the place of Domakha Fortress started in 1778. The settlement was officially renamed ‘Mariupol’ in 1780 (Синяк, 2020).

Fig. 2. Plan of the placement of Mariupol Cemetery. A – Mariupol Cemetery (Макаренко, 1933).

2 pav. Mariupolio neolitinio kapinyno geografinė padėtis. Raide A pažymėta tyrimų vieta (pagal Макаренко, 1933)

An ambitious project to construct a huge steel complex, which later became known as Azovstal, started in Mariupol in 1930.

The construction of a blast furnace on the peninsula between the Sea of Azov and the Kalmius River revealed unique objects. Factory employee Kravets, who was an amateur archaeologist, noticed a red spot with human bones and unusual equipment under it. He informed the local history museum staff about his discovery. Thus famous archaeologist Mykola Makarenko was invited to examine the finding.

Author of the excavations

Mykola Makarenko (1877–1938) was an outstanding Ukrainian archeologist and art critic. His life was a series of discoveries, scrupulous work and tragedies. He was born in Ukrainian Moskalivka Village in 1877. After graduating from the gymnasium, the young man moved to St. Petersburg to study at the Central School of Technical Drawing in 1900–1902 (Рудяченко, 2023). He continued his education in 1902–1905 at the Imperial St. Petersburg Archaeological Institute. While still being a student, Mykola Makarenko started to work at the Imperial Hermitage, where he was promoted to assistant of the chief custodian of funds 16 years later. In 1910, he was elected a valid member of the Russian Archaeological Society (Кухарчук, 2018).

When Ukrainian People’s Republic was proclaimed, along with other outstanding scientists, Makarenko returned to Ukraine. From 1920 to 1925, he served as Director of the Museum of Arts of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. He assumed the position of professor at the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts and private associate professor at the Department of Archeology of Kyiv University, headed the arts section of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, and became an active member of the Archaeological Commission of Ukraine (Кухарчук, 2018).

In 1924, Makarenko was arrested for the first time. The trial of the director of the museum marked the beginning of a bitter struggle between the Soviet authorities and Ukrainian museums (Рудяченко, 2023).

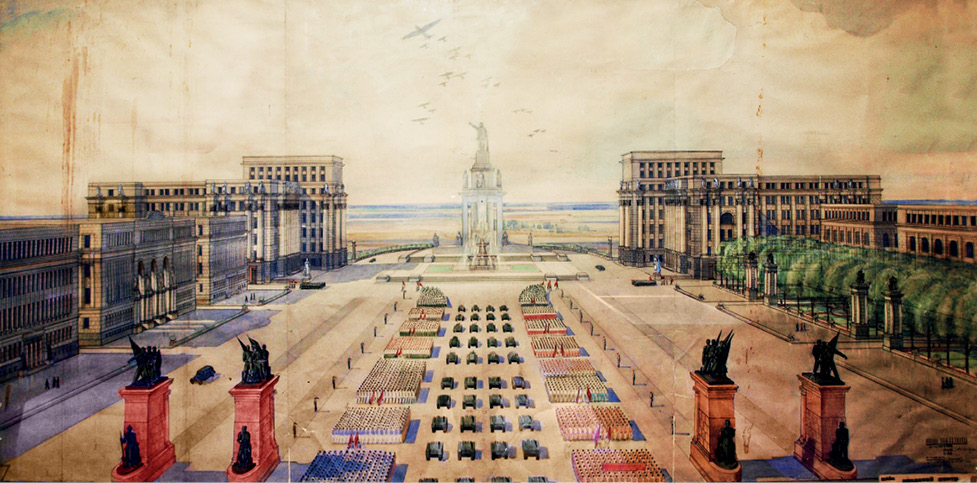

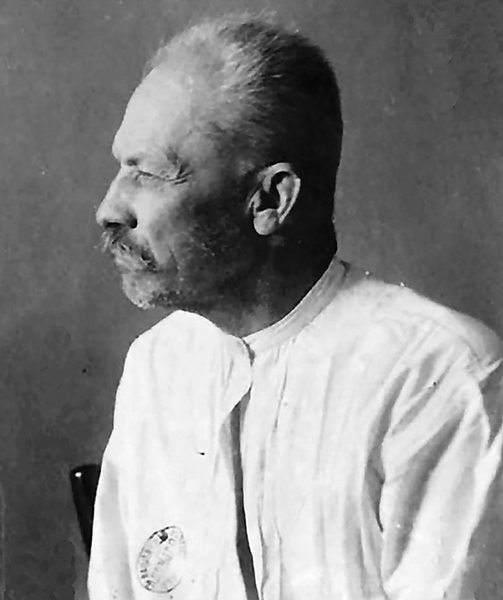

The second trial against M. Makarenko began in the more merciless 1930s. The General Plan of the Development of Kyiv played a fatal role in the life of the outstanding scientist. According to this monstrous plan, the medieval St. Michael’s (Fig. 3) and St. Sophia Monasteries of Kyiv had to be blasted. A pompous and intimidating Government Center had to be built on their site in the mid-1930s (Fig. 4) (Рудяченко, 2023). Mykola Makarenko courageously began the struggle for the protection of the spiritual heritage of Kyiv. He wrote desperate letters to Stalin, and even addressed the French Communists. The response was predictable. The famous archaeologist was arrested in 1934 and exiled to Kazan (Russia) (Fig. 5). The outstanding Ukrainian scientist Mykola Makarenko was executed by Stalin’s repressive machine in Siberia in 1938 (Рудяченко, 2023). However, his courageous sacrifice did not perish in vain as the sanctuary of the Ukrainian people, St. Sophia Cathedral, has been preserved for history.

Fig. 3. St. Michael Monastery. Destroyed in 1937 (https://bigkyiv.com.ua/myhajlivskyj-zolotoverhyj-sobor-vidznachaye-richnyczyu-vidnovlennya-z-ruyin/).

3 pav. Šv. Mykolo vienuolynas, nugriautas 1937 m. (https://bigkyiv.com.ua/myhajlivskyj-zolotoverhyj-sobor-vidznachaye-richnyczyu-vidnovlennya-z-ruyin/)

Fig. 4. Valerian Rykov. General plan of the Government Central Building in Kyiv. 1935 (https://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A3%D1%80%D1%8F%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D1%80_%D1%83_%D0%9A%D0%B8%D1%94%D0%B2%D1%96_%281930-%D1%82%D1%96%29).

4 pav. Architekto Valeriano Rykovo 1935 m. parengtas centrinės valdžios pastatų Kyjive generalinis planas (https://uk.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%A3%D1%80%D1%8F%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D1%80_%D1%83_%D0%9A%D0%B8%D1%94%D0%B2%D1%96_%281930-%D1%82%D1%96%29)

Fig. 5. Mykola Makarenko in exile (http://kngu.org/uk/node/236).

5 pav. Ukrainiečių archeologas Mykola Makarenko tremtyje Kazanėje (http://kngu.org/uk/node/236)

Excavations

Unique in terms of excavations, the exploration of Mariupol Cemetery lasted from August to October 1930 (it was tightly framed as the blast furnace had to be finished by the anniversary of the October Revolution). Archaeologists and laborers worked 12 hours a day without days off.

M. Makarenko wrote: “The moment of the research was not a favorable one. Our works impede the building of the Azovstal. The burial place was excepted from the general building plan. Round it, soil was being thrown. It was necessary to remove the 12 m high mount to obtain a level ground surface. Every day, we were requested to hasten our excavation works. Meanwhile, after one row of tombs which we considered as being the only one in the burial place, we came across a second and then a third one, just when we thought we had already reached the end of the burial place. Crowds of workers surrounded the place of our work. They arrived here by hundreds from different factories and were interested in what they saw of our excavations. We were finally obliged to build a fence of barbed wire to prevent them from hindering us in our work and to fix special hours for the inspection of the excavated material under the guidance of our expedition members” (1933: 136).

Materials of the outstandingly rich cemetery were quickly processed and published in 1933 in an exceptionally fundamental monograph Маріюпільський могильник (Макаренко, 1933). However, after the author’s fall from grace, the circulation was confiscated and was subject to destruction. It was due to the courage and wisdom of some Ukrainian archaeologists that the books were saved for science (Nimenko, 2008).

Mariupol Cemetery

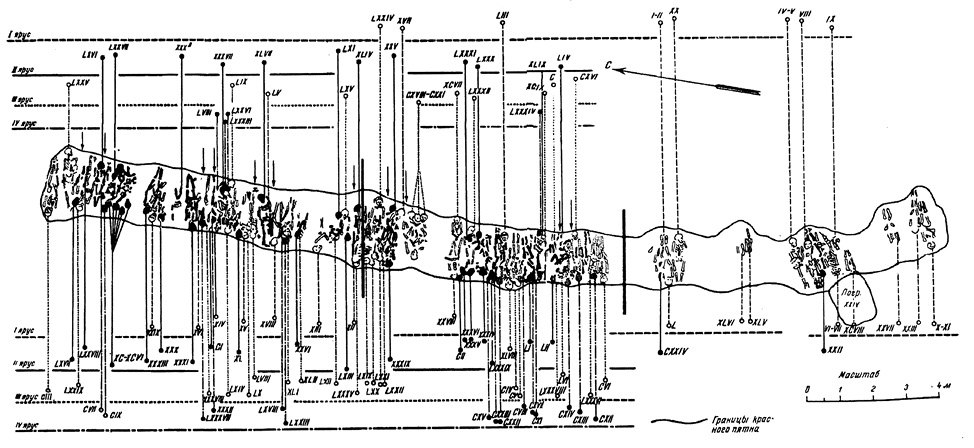

The cemetery border was represented by a stripe of red clay (ochre) more than 2 m broad and 28 m long (Fig. 6). There were 124 graves in total. According to Stoliar, the remains were located in three relatively independent clusters (Fig. 7). They were situated at four different stratigraphic levels (Столяр, 1955: 15, Fig. 1; 1955: 17). The skeletons lying on the back, with outstretched legs, heads turned to the east or to the west, were abundantly covered with red ochre. The skeletons lay parallel to each other within the strip. The taphonomy of the cemetery was complicated: the bones were extremely poorly preserved, and the burials had been partially destroyed in ancient times during the operation of the cemetery.

Fig. 6. Excavations of Mariupol Cemetery. 1930. The photo was provided by Mariupol Local History Museum.

6 pav. Mariupolio neolitinio kapinyno tyrimų akimirka 1930 m. (nuotrauką pateikė Mariupolio kraštotyros muziejus)

Fig. 7. The plan and the stratigraphy position of Mariupol Cemetery (Столяр, 1955).

7 pav. Mariupolio neolitinio kapinyno planas su atidengtų kapų stratigrafiniais lygiais (pagal Столяр, 1955)

An important feature of the burial ground was the strict orientation of the burials – to the west or to the east. Makarenko suggested that male burials were oriented to the east, whereas female burials were directed to the west. He made this assumption because ‘male’ burials had special flint assemblages – blades, bone spears with flint inserts and so on. Meanwhile, ‘female’ burials were often accompanied with children burials. Some ‘female’ graves were without the inventory (1933: 16). We can add that the majority of male burials were richly decorated. In terms of the orientation, 66 burials were female and 41 male. A major part of female burials was without any inventory or only had minimal inventory, mostly, tools.

There were 14 rich and very rich burials with great abundance of adornments. Seven burials had the assemblage of flint tools – blades, scrapers, and so on.

There were 11 exceptionally rich male burials with abundant adornments. Only a few of the male burials were without any inventory.

Nine infant burials were found, with two of them being without grave goods. Some children burials were richer than those of adults. They included special features, such as a bone figurine of a bull, a porphyry axe and a pendant, a rock crystal and so on. Probably, these artifacts can evidence a special sacral status or the potential role of these children in the society.

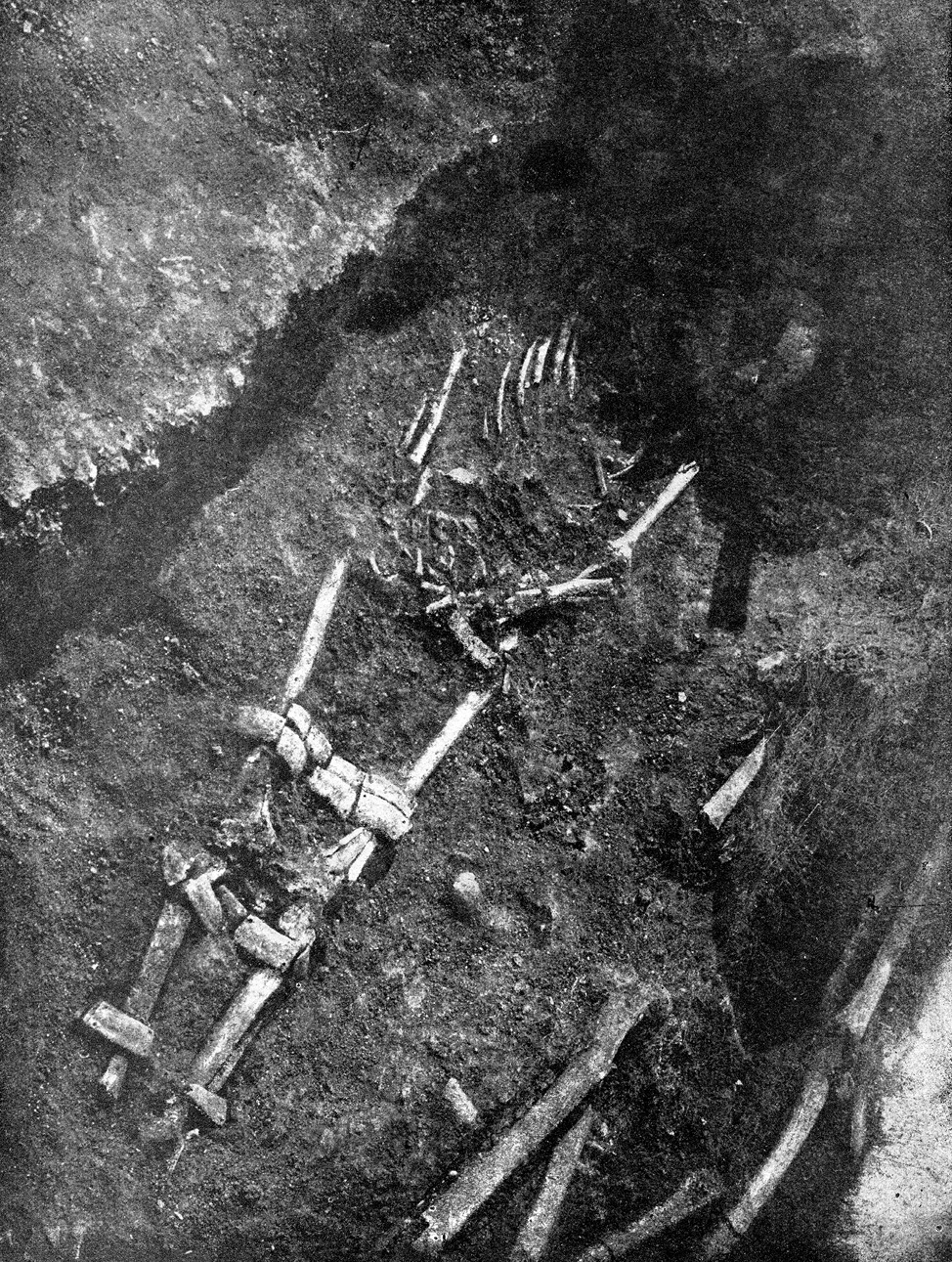

According to Makarenko, the human remains were in a very bad condition, and some even crumbled to dust in the hands of archaeologists. Sometimes, the former presence of human remains could only be guessed by decorations. Unfortunately, the circumstances of the expedition did not allow for careful preservation of the skeletons (Макаренко, 1933: 13). It was due to the efforts of Makarenko that archaeologists managed to carve out two skeletons with rich decoration together with monoliths weighing in between 1.5 and 2 metric tons. The two monoliths were placed in a specially made wooden box and transported to Mariupol Museum. With great difficulty, they were lifted in through the windows and installed on the second floor of the Museum (Fig. 8) (Кухарчук, 2018).

Fig. 8. Installation of burial fragments in Mariupol Museum. 1930. The photo was provided by Mariupol Local History Museum.

8 pav. Mariupolio neolitinio kapinyno vieno iš kapų perkėlimas medinėje dėžėje į Mariupolio muziejų (nuotrauką pateikė Mariupolio kraštotyros muziejus)

Personal ornaments

A lot of the deceased were accompanied with rich grave goods: adornments made from bone, stone, pearl, carp teeth, deer canines, and boar tusks. Men as well as women had unusual abundance of burial inventory. The rich and varied ornamentation that adorned all parts of the body could provide information about the sex, age and status of the remains.

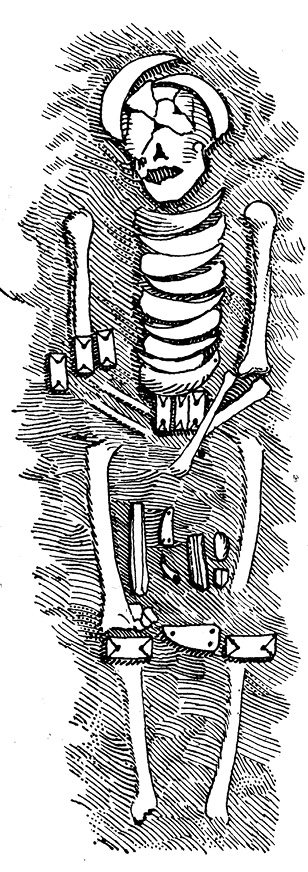

“All children graves were distinguished extraordinary ornaments (Fig. 9). Grave L was essentially filled up with ornaments. A beautifully worked porphyry pendant was found on skeleton CIX (Fig. 10), a grain of rock crystal was laid on the head of skeleton CIV. A figure of an animal made of boar tusk was discovered on skeleton CI” (Fig. 11) (Макаренко, 1933: 137).

Fig. 9. Infant Burial 54. Mariupol Cemetery (Макаренко, 1933).

9 pav. Mariupolio kapinyno vaiko kapas 54 (pagal Макаренко, 1933)

Fig. 10. Porphyry decoration from Burial 109. Mariupol Cemetery (Макаренко, 1933).

10 pav. Mariupolio kapinyno kape 109 rastas porfyrinis papuošimas (pagal Макаренко, 1933)

The most impressive, exclusive and abundant personal ornaments found in Mariupol Cemetery are the perforated boar tusks; they are mostly characteristic to female and children burials, whereas they are less represented in male burials. Mainly, they were used to decorate the head, the neck, and the chest of the deсeased (Fig. 12). The tradition to decorate clothing with wild boar tusks existed during the Neolithic Period in various cultures and regions of Europe. Yet, such totality and the large-scale of use as manifested in the Mariupol burial complex is outright unique.

Fig. 11. Animal figurine from Burial 101. Mariupol Cemetery. The photo was provided by Mariupol Local History Museum.

11 pav. Zoomorfinė figūrėlė iš Mariupolio kapinyno kapo 101 (nuotrauką pateikė Mariupolio kraštotyros muziejus)

Fig. 12. Female Cemetery 6. Mariupol Cemetery (Макаренко, 1933).

12 pav. Moters kapas 6 iš Mariupolio kapinyno (pagal Макаренко, 1933)

Probably, these artifacts marked the representation of a certain group.

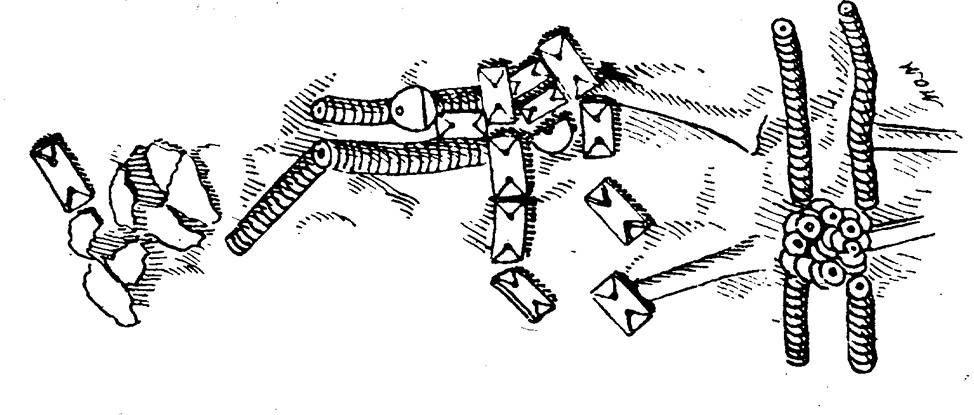

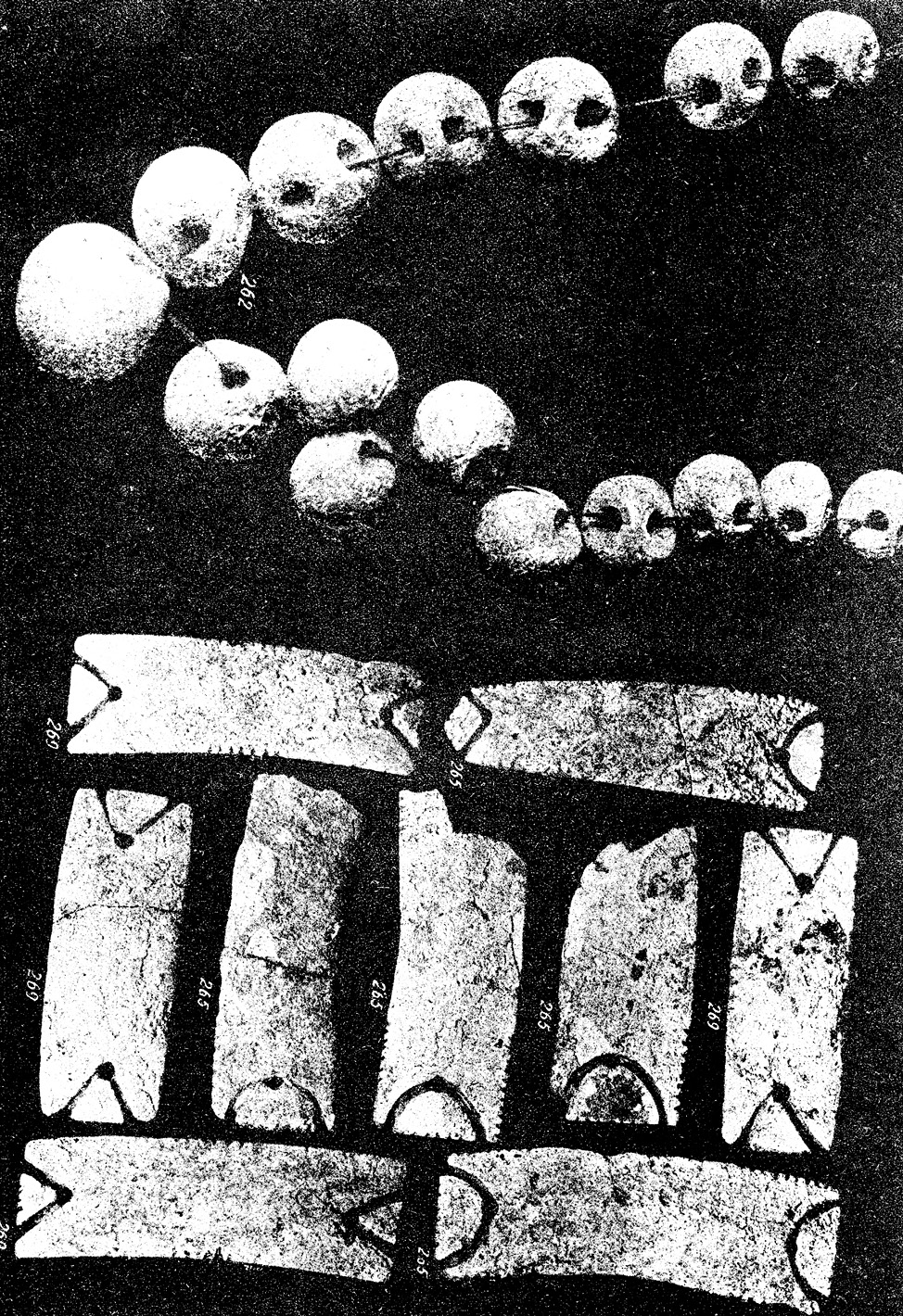

The most fascinating and frequently found in the complex feature of the Mariupol-type grave offering is the plates made of boar tusks of various shapes. With the edges sometimes bearing enigmatic incisions, they were skillfully made (Fig. 13). While s such multi-ornamented plates are almost unknown in other areas of Europe, Mariupol Cemetery remains to be perceived as a unique funeral complex due the great amount of such ornaments.

Makarenko (1933: 142) described these artefacts: “The plates were made of boar tusks – quadrangular and elongated ones are the ornament most frequently found in the burial-place. These plates may be divided in three types: short, broad, and narrow. They are carefully made. Their edges sometimes bear enigmatic incisions, sometimes single, sometimes in groups. Found on skeletons, from skull to feet, these plates were included into different parts of the garments.”

There were rows of plates on the waist, knees or shins of the deceased in some burials of Mariupol-type cemeteries. Probably, some parts of the plates were used as belt decorations. The belts might have been fastened over the cloth into which the deceased were wrapped (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Burial 56. Mariupol Cemetery (Макаренко, 1933).

13 pav. Mariupolio kapinyno kapas 56 (pagal Макаренко, 1933)

The perforated deer canines in Mariupol Cemetery were present mostly in female graves, yet rarely in male ones. They marked important parts of the skeletons – such as head, neck, pelvis, and feet.

Also, there were numerous beads and pendants of different materials: shells, bone, marble, jet, etc. (Fig. 14). Some beads were of unique forms “There were aesthetically perfect ring shaped or semilunar shell beads; cylindrical and ring-shaped shell and semilunar pearl beads; round or pear shaped bone beads with various holes; cylindrical jet, slate or geshir gagat (jet) beads among them” (Макаренко, 1933: 142).

Fig. 14. Bone beads and plates made of boar tusks from Burial 74. Mariupol Cemetery. Photo xerocopy after Макаренко, 1933.

14 pav. Kauliniai karoliukai ir plokštelės iš šerno ilčių, rasti Mariupolio kapinyno kape 74 (b/j nuotraukos kserokopija, Макаренко, 1933).

There were stone and bone pendants, a magnificent porphyry pendant and two stone maces. Two zoomorphic figurines, carved from the boar tusk, were found (Fig. 11). Presumably, zoomorphic figurines are ‘insignia’ of those particular animals symbolizing virtual connection of the buried persons with their totems.

Personal ornaments, semantically identifying important body parts, indicated the clan or the origin, the age or the biological stage of life. Logical reasoning suggests that rich grave goods depended on the age and experience of the dead person. The analysis of grave goods in general reveals social rites connected with the social and marital status, as well as gender and age-related ceremonies.

Death of the site

The fate of Mariupol Cemetery, similarly to fate of Mykola Makarenko, was tragic. The anthropological materials of Mariupol Cemetery were mostly destroyed during World War II. Part of the burial inventory was kept in Mariupol Museum. The tablets with decorations made of boar tusks, plates, animal teeth and mother-of-pearl necklaces were shown in the exhibition. The monoliths with burials were exhibited separately.

In April 2022, during the fierce battles for Mariupol, the local history museum was fired upon by russian occupying forces. The wooden floors of the building, erected during the First World War, burned down (Масюк, 2022). The fire also destroyed the exhibits, including plates with decorations from the Mariupol burial ground and the two monoliths with skeletons. According to the russian opposition publication Sobesednik, “[…] out of 70 thousand exhibits of the main fund, only 10 thousand remained” (Ноздряков, 2023) (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15. Ruins of Mariupol Local History Museum. April 2022 (https://novosti.dn.ua/news/330863-opublikovani-foto-zrujnovanogo-armiyeyu-rf-mariupolskogo-krayeznavchogo-muzeyu).

15 pav. Mariupolio kraštotyros muziejaus griuvėsiai, 2022 m. balandis (https://novosti.dn.ua/news/330863-opublikovani-foto-zrujnovanogo-armiyeyu-rf-mariupolskogo-krayeznavchogo-muzeyu)

The unique collection to be studied by lots of researches in future from all over the world perished at the hands of the russian occupiers. In September 2022, a predatory group under the cover of the so-called Russian Historical Society visited the destroyed Mariupol. Nikolai Makarov, the main marauder of russian archeology and the director of the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, cynically stated: “We also need to save the badly wounded Mariupol Museum” (Делегация...).

The above-mentioned Russian Historical Society was organized as a tool of Sergey Naryshkin, Director of the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation. He formulated the metaphoric aim of his ‘activity’ on May 13, 2023: “I hope that this experience will be popular in the frame of works of a new order by the head of state... Its evidence is the participation of this museum in the preparation of the wonderful multimedia exhibition Russian Azov, recently opened with the support of the Russian Historical Society in the pavilion Russia – My History in Moscow” (Fig. 16) (Нарышкин: 2023).

Fig. 16. Part of the exhibition Russian Azov in Moscow, 2023. Animal figurine from the burnt exposition of Mariupol Local History Museum and reconstruction of the costume of the Mariupol Warrior by Ukrainian artist Zinaida Vasina (https://historyrussia.org/sobytiya/vystavki/v-istoricheskom-parke-rossiya-moya-istoriya-otkrylas-vystavka-russkij-azov.html).

16 pav. Parodos „Rusijos Azovas“ dalis Maskvoje, 2023 m. Gyvūno figūrėlė iš sudegintos Mariupolio kraštotyros muziejaus ekspozicijos ir ukrainiečių menininkės Zinaidos Vasinos „Mariupolio kario“ kostiumo rekonstrukcija (https://historyrussia.org/sobytiya/vystavki/v-istoricheskom-parke-rossiya-moya-istoriya-otkrylas-vystavka-russkij-azov.html)

Conclusions

Mariupol Neolithic Cemetery became a new page in the archeology of Europe. It contained a huge array of information about the spiritual world, the social structure, gender relations, and the burial rites of the Neolithic population of Eastern Europe. The unusual richness of the burial equipment, the number of status burials, including lots of children’s burials, a large number of original decorations unknown at other sites could have been studied by many generations of scientists.

The tragedy of the Mariupol burial ground is part of the tragedy of the Ukrainian archaeological science: one of the most remarkable monuments of the primitive archeology of Ukraine, perfectly excavated and perfectly published, was destroyed twice by the occupiers – nazi and rashist.

Ukrainian archaeologists are not alone. Colleagues from many countries are supporting them. The special plenary on the russian invasion of Ukraine was held during the World Archaeological Congress-9 in 2022 in Prague. Jan Turek, WAC-9 Academic Secretary, said: “There is damage to Ukrainian national heritage, in a deliberate attempt to assert Russian national cultural dominance over common historical roots and thereby falsely rewrite the history and ethnic history of the entire region. Such a policy is totally unacceptable in the 21st century, and Putin and his administration must be tried for their humanitarian war crimes by an international tribunal” (WAC-9 2022).

Bibliography

Делегация Российского исторического общества посетила Мариуполь и Бердянск. Новости и события Российского исторического общества. 2022. [online]. Access online: https://historyrussia.org/sobytiya/delegatsiya-rossijskogo-istoricheskogo-obshchestva-posetila-mariupol-i-berdyansk.html?fbclid=IwAR1w5DksReWtYQuvMNw-kB6dBWiG0GvDyvrQO34FwLKTHRqCJhPrLMgnYQg

Котова Н.В. 1994. Мариупольская культурно-историческая общность (Днепро-донское междуречье). Археологічні пам’ятки та історія стародавнього населення України, 1, с. 4–143.

Кухарчук Ю. В. 2018. Внесок Миколи Макаренка в археологічну науку. Православ’я в Україні. Збірник за матеріалами VII Міжнародної наукової конференції, присвяченої 25-літтю відновлення Київської православної богословської академії. Київ, с. 366–381.

Макаренко М. О. 1933. Маріюпільський могильник. Київ: Видавництво Всеукраїнської академії наук.

Масюк М. 2022. “Якщо порівняти з Другою світовою, руйнування більші”. Працівник музею в Маріуполі про команду та експонати, віддані росіянам [online]. Access online: https://gwaramedia.com/yakshho-porivnyati-z-drugoyu-svitovoyu-rujnuvannya-bilshi-praczivnik-mariupolskogo-muzeyu-pro-komandu-ta-eksponati-viddani-rosiyanam/

Михайлова Н. Р. 2019. Дитячі поховання Маріупольського типу: питання інтерпретації. В: Чабай, В. П. (ред.). І Всеукраїнський археологічний з’їзд: матеріали роботи. Київ: ІА НАН України, с. 171–181.

Михайлова Н. Р. 2020. Особливі діти. Персональний орнамент у дитячих по хованнях Маріупольського типу. Археологія і давня історія України, вип. 4(37), с. 163–171.

Ноздряков Д. 2023. Спецоперация по демузеефикации. Собеседник, 16.

Потехина И.Д. 1999. Население Украины в эпохи неолита и раннего энеолита по антропологическим данным. Київ.

Потехина И.Д. 2006. Биоархеологические реконструкции первобытного населения контактных зон юга Восточной Европы. Вестник антропологии, 14, с. 90–98.

Рудяченко О. 2023. Микола Макаренко. Не жити лагідно із янголами та чортами [online]. Access online: https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-culture/3662891-mikola-makarenko-ne-ziti-lagidno-iz-angolami-ta-cortami.html

Синяк І. 2020. Поселення Кальміуської паланки в ґенезі сучасних населених пунктів. В: Репан О. (ред.) Нариси з історії освоєння Південної України XV-XVIII ст. Київ: К.І.С., с. 227–255.

Сергей Нарышкин: Необходимо последовательно отстаивать историческую правду Новоросии. Новости и события Российского исторического общества [Online]. Access online: https://historyrussia.org/sobytiya/sergej-naryshkin-neobkhodimo-posledovatelno-otstaivat-istoricheskuyu-pravdu-novorossii.html

Столяр А. Д. 1955. Мариупольский могильник как исторический источник (опыт историко-культурного анализа памятника). Советская археология, 23, с. 16 Новости и события Российского исторического общества. 37.

Шевельов Ю. 2017. Я – мене – мені... (і довкруги): Спогади. Харків : Видавець Олександр Савчук.

Kotova N. 2010. Burial clothing in Neolithic cemeteries of the Ukrainian steppe. Documenta Praehistorica XXXVII, р. 167–177.

Mykhailova N. 2020. Personal ornaments of the children in the Mariupol type cemeteries. In: Beauty and the Eye of the Beholder. Personal Ornaments across the Millennia. Margarit M., Boroneant A. (Eds.). Târgoviște: Cetatea de Scaun, p. 371–382

Telegin, D. Ya., Potekhina, I. D., Lillie, M., Kovalukh, M. M. 2002. The Chronology of the Mariupol-Type Cemeteries of Ukraine Revisited. Antiquity 76, 356–363.

Mykola Makarenko ir Mariupolio neolitinis kapinynas. Tragiškas ukrainiečio archeologo ir vietovės likimas

Nataliia Mykhailova

Santrauka

Mariupolio neolitinis kapinynas yra unikalus savo inventoriaus turtingumu, kuriam nėra lygių Ukrainoje. Kapinyną tyrinėjo iškilus Ukrainos archeologas ir menotyrininkas Mykola Makarenko, kuris dėl savo politinės, mokslinės ir visuomeninės pozicijos 1934–1938 m. buvo ištremtas į Kazanę. 1938 m. jis suimamas, o metais vėliau Tomske jam įvykdyta mirties bausmė.

Išskirtiniai kasinėjimai vyko 1930 m. rugpjūčio–spalio mėnesiais. Buvo atidengti 124 kapai, kurie išsidėstę daugiau nei 2 m pločio ir 28 m ilgio raudono molio (ochros) juostoje. Palaikai buvo išsidėstę trijuose palyginti nepriklausomuose klasteriuose ir keturiuose skirtinguose stratigrafiniuose lygmenyse. Skeletai paguldyti ant nugaros, ištiestomis kojomis, galva pasukti į rytus arba vakarus, gausiai apipilti raudona ochra. Skeletai prastai išlikę, tirtoje juostoje gulėjo lygiagrečiai vienas kitam. Dalis jų stipriai apardyti praeityje. Paminėtina, kad kai kurie iš mirusiųjų buvo palaidoti su išskirtinai turtingu inventoriumi – perforuotomis šernų iltimis, įvairiai ornamentuotomis šerno ilčių plokštelėmis, kauliniais karoliukais, įvairių formų kriauklėmis, akmeniniais ir kauliniais kabučiais, įmantriu porfyriniu kabučiu ir dviem akmeninėmis buožėmis.

Tyrinėto Mariupolio nekropolio reikšmė Ukrainos archeologijoje buvo tokia didelė, kad jo pavadinimas buvo naudojamas apibūdinti laidojimo kompleksų tipą, kuris buvo plačiai paplitęs vėlyvajame mezolite ir neolite srityse nuo Dniestro iki Dono.

2022-ųjų balandį, per įnirtingus mūšius dėl Mariupolio, Mariupolio kraštotyros muziejus buvo intensyviai apšaudytas okupacinių pajėgų artilerijos. Unikali kolekcija, kuri galėjo būti tyrimo objektas daugeliui mokslininkų iš viso pasaulio, žuvo nuo rusų okupantų.