Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2025, vol. 26, pp. 231–245 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2025.26.9

Irina Olevska-Kairisa

Maastricht University

Minderbroedersberg 4-6, 6211 LK Maastricht

i.olevska@maastrichtuniversity.nl / Irina.olevska@gmail.com

Abstract. Heritage crimes, including illicit excavation, looting, and the destruction of archaeological sites, have lasting repercussions that reach beyond physical damage. They erode vital links to humanity’s past and deprive future generations of cultural knowledge. Archaeologists, heritage professionals, and the wider scientific community—dedicated to preserving and understanding cultural heritage—are among the most deeply affected by these crimes. Such damage compromises scientific research, leading to permanent loss of knowledge and assaulting directly the work of those who safeguard these sites. Yet, despite the significant pecuniary and non-pecuniary damage suffered by heritage professionals, legal frameworks often emphasize punishing offenders over recognizing and compensating victims, leaving the scientific community’s interests unaddressed.

This article examines the impact of heritage crimes on archaeologists and heritage professionals, advocating for more attentive approach to their potential formal recognition as victims within criminal justice proceedings. Drawing on survey data, case law, and expert interviews, it highlights the urgent need for legal systems to acknowledge the multifaceted harm inflicted by these crimes. By addressing this oversight, the article aims to support a more comprehensive approach to heritage protection, reinforcing cultural heritage as a public good essential to collective memory and identity.

Keywords: heritage crimes, victims, scientific community, harm, cultural rights

Anotacija. Nusikaltimai paveldo srityje, įskaitant nelegalius kasinėjimus, plėšimus ir archeologinių vietų naikinimą, turi ilgalaikių pasekmių, kurios apima ne vien fizinę žalą. Jie ardo svarbius ryšius su žmonijos praeitimi ir atima iš ateities kartų galimybę pažinti kultūros paveldą. Archeologai, paveldo specialistai ir platesnė mokslo bendruomenė, kuri yra pasišventusi kultūrinio paveldo išsaugojimui ir supratimui, yra vieni iš labiausiai paveiktų šių nusikaltimų. Tokia žala turi įtakos moksliniams tyrimams, veda prie nuolatinio žinių praradimo ir tiesiogiai kenkia tiems, kurie tyrinėja ar saugo šias vietas. Tačiau nepaisant didelės materialinės ir nematerialinės žalos, kurią patiria paveldo specialistai, teisinės sistemos dažnai akcentuoja nusikaltėlių baudimą, o ne šių aukų pripažinimą ir žalos atlyginimą, todėl į mokslo bendruomenės interesus lieka plačiau neatsižvelgiama. Šiame straipsnyje nagrinėjamas paveldo nusikaltimų poveikis archeologams ir paveldo specialistams, raginama atidžiau vertinti jų galimą oficialų pripažinimą aukomis baudžiamosios teisės procesuose. Remiantis apklausos duomenimis, teismų praktika ir interviu su ekspertais, straipsnyje pabrėžiama, kad teisinės sistemos turi skubiai pripažinti daugialypę žalą, kurią daro šie nusikaltimai. Šiuo straipsniu siekiama atkreipti dėmesį į teisinį aspektą ir paremti visapusišką požiūrį į paveldo apsaugą, taip aktualizuojant kultūros paveldo svarbą kolektyvinės atminties ir tapatybės išsaugojimui.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: nusikaltimai paveldui, aukos, mokslo bendruomenė, žala, kultūrinės teisės.

_______

Received: 04/02/2025. Accepted: 20/02/2025

Copyright © 2025 Irina Olevska-Kairisa. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Heritage crimes, including the illicit excavation, looting, and the destruction of archaeological sites, have long been regarded as profound losses for humanity. The implications of such crimes extend far beyond the immediate damage to physical objects, erasing invaluable links to our past and depriving future generations of their cultural inheritance.

While the above has been widely declared (Hague Convention 1954, World Heritage Convention 1972, Nicosia Convention 2017, UN SC Resolution 2347, etc.), there has been limited theoretical development and empirical research dedicated to identifying specific groups of victims of heritage crimes as well as understanding the scope and extent of harm they endure. Over the past decade, a few attempts have been made to address significant gaps in knowledge about heritage crime victimization from both theoretical (see, for instance, Poyser et al. 2022; Olevska-Kairisa and Kairiss 2022; Poyser and Poyser 2017) and practical judicial perspectives (for instance, Al Mahdi Reparation Order). However, most of these efforts remain jurisdiction-specific (e.g., Poyser et al., 2022) or case-specific (e.g., Al Mahdi Reparation Order).

This study focuses on one of the groups allegedly most affected by heritage crimes, whose victimization has not yet been extensively explored. Those are the archaeologists, heritage professionals, and the broader scientific community, who dedicate their lives to studying, preserving, and disseminating knowledge about our shared cultural patrimony. Damage and destruction of archaeological sites undermine the scientific processes that rely on the integrity of these sites and lead to a permanent loss of knowledge and scholarly potential. For archaeologists and heritage professionals, these crimes may be deeply personal: they represent a direct assault on their work, their research, and their professional identities. “Indignation”, “helplessness”, “spite” are the often feelings they experience when yet another case of damage, vandalism or the destruction of archaeological sites comes to light.1

Despite the severe declared level of harm suffered by heritage crime victims, the current legal frameworks often focus on retribution (finding and punishing) to the offender than restoration to the victims (Kerr 2013; Interview with G.Kutris). Consequently, they usually fail to recognize the scientific community as a victim within criminal proceedings related to heritage crimes. This oversight not only diminishes the gravity of the harm caused but also weakens the broader societal understanding of the consequences of heritage crimes.

This article seeks to address the gap by exploring the impact of heritage crimes on archaeologists and heritage professionals, with a particular focus on the potential of recognizing the scientific community as a victim within the context of criminal justice. Through the results of the conducted survey, detailed examination of case law, and interviews with the professionals in the field, the article seeks to demonstrate the far-reaching consequences of heritage crimes on the scientific community and argues for the inclusion of these professionals as recognized victims within criminal proceedings. This recognition is crucial not only for ensuring justice but also for reinforcing the importance of cultural heritage as a public good that transcends individual ownership or sole state patronage and serves as a foundation for collective memory and identity.

In doing so, this research aims to:

• Examine the practical implementation of cultural rights within the scientific community;

• Investigate the personal attitude of scientific community members on the criminal acts of damaging or destroying archaeological sites;

• Analyze self-recognition of the members of the scientific community as victims of archaeological crimes and evaluate their willingness to seek formal recognition in criminal proceedings;

• Assess the current recognition of the scientific community as victims of archaeological crimes within criminal justice systems.

Ultimately, this study aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse on the legal and ethical responsibilities of protecting cultural heritage and to advocate for a more comprehensive approach to addressing victimization in heritage crime cases. By highlighting the multifaceted impact of these crimes on the scientific community, this article underscores the need for legal systems to evolve and better address the complexities of heritage protection in the 21st century.

The research methodology combines a comprehensive analysis of scientific literature, legal frameworks, and case law with in-depth interviews. These interviews were conducted with heritage professionals from Latvia, Estonia, and France, as well as a legal professional from Latvia, providing diverse perspectives and insights into the subject matter. This multifaceted approach ensures a well-rounded understanding of the issues at the intersection of heritage crimes, victimization, and legal recognition.

The major findings of the study were acquired through the survey conducted between 29 January - 30 June 2024. The survey questions (in two blocks – one for the members of the European Association of Archaeologists (hereinafter – the EAA) and one for heritage professionals, who are non-members thereof) were distributed through the following channels:

• A publication in the newsletter of the EAA “The European Archaeologist” Winter 2024 issue 79 “A Survey on the Impact of Archaeological Damage on the Scientific Community: Responses due by 15th March”, available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378461432_A_Survey_on_the_Impact_of_Archaeological_Damage_on_the_Scientific_Community_Responses_due_by_15_th_March_Published_in_The_European_Archaeologist_79_Winter_2024_issue;

• Direct mails to the members of the Community on the Illicit Trade in Cultural Material of the EAA, since the author is a member of the Community;

Direct mails to the Communities and Committees of the EAA, including, Archaeological Legislation and Organization Committee, Political Strategies Committee, Archaeological Prospection Community, Community on Fieldwalking Documentation, Community on Fortification Research, Community on Computational Modelling of Past Socio-ecological Systems, Community on Discovering the Archaeologists of Europe, EAA Working Group, Early Career Archaeologists Community, Medieval Europe Research Community, Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Community, Urban Archaeology Community, Community Integrating the Management of Archaeological Heritage and Tourism;

• Direct mails to the Lithuanian Archaeological Society, Estonian Association of Archaeologists, The Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Archaeological Society of Finland, British Archaeological Association, Society for American Archaeology;

• Direct dissemination by the committees of the CIfA Heritage Crime, Research & Impact, and International Practice SIGs to all the members of the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists.

The questions covered the following topics:

1. Self-recognition as an affected or suffered party if an archaeological site is damaged as a result of illegal activities;

2. Capacity in which the above affect takes place;

3. The first reaction to the case of damage of an archaeological site of the concern of the respondent;

4. Personal perspective toward formal recognition of the scientific community as a victims in instances involving illegal activities towards archaeological sites;

5. Types of appropriate reparation for the harm caused to the scientific community;

6. Experience of formal recognition as a victim in instances involving damage or destruction of archaeological sites.

The total amount of respondents was 133, consisting of:

• members of the EAA (59 responses altogether),

• members of the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (44 responses; 11 of them also members of the EAA (included in the overall 59 responses mentioned above)),

• other specialists in archaeology and heritage practitioners in the related fields.

The respondents included:

• archaeologist/researcher in the field of archaeology -80 (60,2%);

• academic staff in the field of archaeology -17 (12,8%);

• representative of heritage authority -9 (6,7%);

• researcher in the field other than archaeology -6 (4,5%);

• museum staff -6 (4,5%);

• other archaeological heritage professionals – 15 (11,3%), including academic staff in the field other than archaeology -3; laboratory expert or other staff -2; consultant on Archaeology, Heritage, Cultural Tourism and Sustainability -2; law enforcement professional -2; restoration architect -1; student -1; repatriation practitioner -1; NGO international expert in the field of cultural heritage -1; citizen scientist -1; professional commercial archaeologist -1.

Human rights are inherent to all of us, extending from the “right to life” to the rights that enrich our quality of life. Among these, cultural rights have been recognized as fundamental human rights since the mid-20th century (e.g., Art.27, Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948; Art.15, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966). However, as over time the focus has largely been on the development of civil and political rights, cultural rights have remained comparatively underdeveloped (see, e.g., Symonides 2002; Niec 1997).

Out of the many manifestations (see, e.g., Fribourg Declaration on Cultural Rights 2007), one of the most broadly-recognized cultural rights is the one to access and enjoy culture. Access to culture2 covers “…in particular the right of everyone — alone, in association with others or as a community — to know and understand his or her own culture and that of others through education and information, and to receive quality education and training with due regard for cultural identity” (CESCR 2009). Accordingly, archaeologists appear as both the holders (along with other members of local communities and broader society) and the enforcers (those who unveil information and lay the groundwork for education) of this right.

Singling out scientific community as one of the key stakeholders with a vested interest in cultural rights is not unique. Thus, for instance, Farida Shaheed, UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, specifically recognized “scientists and researchers” as a group with a direct stake in cultural heritage (Shaheed, 2011a). She emphasized that this recognition carries important implications for both States and courts. For States, it highlights the need to involve scientists and researchers in consultations, participation procedures, and to ensure access to effective remedies, including judicial avenues. For courts, it underscores the importance of considering the interests of this group when adjudicating conflicts over cultural heritage. Thus, it can be concluded that when heritage sites are damaged, the harm suffered by researchers—whether individually or collectively—should be recognized and accounted for (redressed).3

While the violation of cultural rights (as part of fundamental human rights) is typically understood as the injurious conduct of the state toward the affected parties, rather than the actions of a perpetrator toward cultural heritage stakeholders, such violations can occur not only through direct actions but also through omissions or failures by states to fulfil their legal obligations. According to CESCR, these omissions include the failure to take appropriate steps to fully realize the right of everyone to participate in cultural life, as well as the failure to enforce relevant laws or provide necessary administrative, judicial, or other remedies to enable individuals to exercise this right in its entirety. States are therefore obligated to adopt strategies and policies that establish effective mechanisms and institutions, where lacking, to investigate and address alleged violations of the right to take part in cultural life, assign responsibility, publicize findings, and provide necessary administrative, judicial or

other remedies to compensate victims (points 63 and 72, CESCR 2009).

Directive 2012/29/EU sets out minimum standards on the rights, support, and protection of victims of crime. According to the Directive, a victim is defined as a natural person who has suffered harm—whether physical, mental, emotional, or economic—directly caused by a criminal offence (Article 2, part 1).4 To the certain extent this definition is shared also by other international documents, such as the UN General Assembly Resolution 40/34 (Article A(1)) and the International Criminal Court (ICC) Rules of Procedure and Evidence (Rule 85). Harm is a crucial factor in determining who qualifies as a victim participant in legal proceedings (Gacka, 2018, p.27), in making criminalization decisions (Puig S.M., 2008), and in decisions regarding reparations (Victims’ Rights Working Group & Redress, 2018). From a procedural perspective, understanding the type and extent of harm in each case is essential for safeguarding both the rights of the convicted person and the victims (Ntaganda Reparations Order, para. 130).

International documents and legal practice often define harm by listing its components rather than providing a singular definition. For instance, Article 8 of the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law (Reparation Guidelines) states that harm includes “ physical or mental injury, emotional suffering, economic loss or substantial impairment of […] fundamental rights, through acts or omissions [that constitute gross violations of international human rights law, or serious violations of international humanitarian law].

Although the founding documents of the International Criminal Court (ICC) do not explicitly define harm, Rule 97 refers to it as “damage, loss, or injury”. ICC case law further elaborates, describing harm as encompassing material, physical, psychological (i.e., Lubanga Observations, para.36; Lubanga Reparations Order, para.10; Understanding the International Criminal Court, para.69; Al Mahdi Reparations Order, para.43), or even sui generis harm (Katanga Reparations Order, paras.136-139). While the ICC acknowledges both direct and indirect harm—which goes beyond the scope of victimhood under Directive 2012/29/EU—it emphasizes that the harm must be personal to the victim (Lubanga Reparations Order, para. 10).

According to the previous research of the author held among the members of the Latvian Society of Archaeologists, archaeological heritage professionals suffer the following types of harm: (a) emotional distress, decrease in cultural-historical value of the damaged sites, disruption of culture suffered predominantly socially and (b) restriction of research/earning opportunities suffered by them predominantly economically (Olevska-Kairisa and Kairiss, 2023). In order to double-check the findings among archaeologists and heritage practitioners at the broader level the author has held a Survey. To answer the questions on their personal attitude toward the archaeological crime, the respondents were given a scale from “0” - not feel affected/ suffered at all to “10” - feel highly affected/ suffered.5 Out of 133 specialists in the area the following responses were received:

Table 1. Would you perceive yourself (for any reason) as an affected or suffered party if an archaeological site is damaged as a result of illegal activities?

1 lentelė. Ar (dėl kokios nors priežasties) laikytumėte save paveikta ar nukentėjusia šalimi, jei archeologinė vietovė (objektas) būtų pažeistas dėl nelegalios veiklos?

|

“0” (not suffered) |

“1” to “5” (rather suffered) |

“6” to “7” (quite suffered) |

“8” to “10” (very much suffered) |

|

|

Site of archaeological age relevant to your expertise at your homeland |

6.0% |

15.0% |

9.8% |

69.2% |

|

Particular site you are researching (working at) or have researched (worked at) |

4.5% |

12.8% |

14.3% |

68.4% |

|

Any site anywhere at your homeland |

5.3% |

23.3% |

15% |

56.4% |

|

Site of archaeological age relevant to your expertise anywhere in the world |

3.8% |

18.1% |

24.8% |

53.3% |

|

Any site anywhere in the world listed in UNESCO World Heritage list |

3.8% |

21.9% |

23.3% |

51.0% |

|

Any site anywhere in the world |

4.5% |

29.3% |

23.3% |

42.9% |

It can be concluded that generally the level of harm suffered by the archaeological heritage professionals in case of damage or destruction of archaeological sites is quite high (around 50 to 70% would feel very much suffered (“8” to “10” at the scale; except for the category “Any site anywhere in the world”), while 65% to almost 83% of the respondents would feel “quite suffered” and “very much suffered” together (from “6” through to “10” at the scale)). The survey indicates that the highest levels of suffering are associated with sites to which respondents have a close professional connection—specifically, archaeological sites relevant to their area of expertise within their homeland, as well as sites they have personally researched. Interconnected social and professional ties, such as sites located anywhere in the homeland, sites of relevant archaeological age anywhere in the world, and sites of exceptional value (including those on the UNESCO World Heritage list), evoke somewhat lower levels of suffering compared to purely professional ties. However, these still rate significantly higher than sites of less defined nature or relevance to respondents.

Table 2. If you would perceive yourself as an affected or suffered party, in what capacity do you believe you would feel affected?

2 lentelė. Jei laikytumėte save paveikta ar nukentėjusia šalimi, kokiu pagrindu, manote, jaustumėtės paveikta?

|

“0” |

“1” to “5” |

“6” to “7” |

“8” to “10” |

|

|

As a local resident living in the vicinity of the affected archaeological site |

4.5% |

21.8% |

9.8% |

63.9% |

|

As a professional deprived in/ restricted of the (real or hypothetical) possibility to study an archaeological site |

3.0% |

19.6% |

14.2% |

63.2% |

|

As a cultural heritage admirer |

0.8% |

18.0% |

18.1% |

63.1% |

|

As a member of society |

1.5% |

22.6% |

15.8% |

60.1% |

|

As a member of the scientific community |

3.8% |

23.3% |

13.5% |

59.4% |

|

As a representative (member) of the relevant (archaeology-related national or international) NGO |

13.5% |

22.7% |

15.0% |

48.8% |

|

As a representative of the confession concerned (if the damaged object has religious significance |

34.6% |

23.3% |

10.6% |

31.5% |

The responses to the second question reveal that archaeological heritage professionals experience significant suffering both socially and professionally. Socially, as members of local communities, cultural heritage admirers, and broader society, over 60% of respondents rated their personal suffering in these roles as very high, scoring between “8” and “10”. Professionally, as professionals deprived in or restricted of the possibility to study an archaeological site, and as members of the scientific community, around 60% also rated their suffering in these capacities as very high, within the same score range. 6

The results of the two first questions discussed above (a) highlight the profound personal and professional impact of heritage crimes on those dedicated to its preservation and (b) in relation to these professionals unveil two key factors that determine whether a person is eligible for recognition as a victim: the experience of suffering and the nature of the harm endured. This creates a clearer connection between the specific experiences of archaeological heritage professionals and the broader legal framework for recognizing victim status. While it is the Court’s responsibility to clearly define the specific harms in each case (Lubanga Reparations Appeal Judgment, para. 184), the questions arises: given the extensive and multifaceted harm suffered by archaeological heritage professionals, should their suffering be overlooked or left unrecognized, without being addressed during criminal proceedings?

There appear to be several factors contributing to the scientific community’s lack of engagement in seeking recognition as victims in heritage crimes and advocating for their rights in the criminal process. For instance, the Latvian Society of Archaeologists noted that they have never applied for victim status due to lack of relevant experience in criminal proceedings, limited awareness of victim rights, legal obstacles to recognition, challenges in assessing damage or loss to the society, and a lack of information from criminal authorities about their potential to claim victim status (Written answers M.Kalnins). The latter, together with lack of relevant experience in criminal proceedings and uncertainty about receiving compensation, as well as existing “conflict of interests” between archaeological and related associations and public authorities involved7, were highlighted by a France-based NGO ArkeoTopia (Interview with J.-O. Gransard-Desmond). Legal obstacles to being recognised as a victim and difficulty in assessing the caused damage/loss were also mentioned among concerns of the Estonian Archaeological Society (written answers by U.Kadakas).

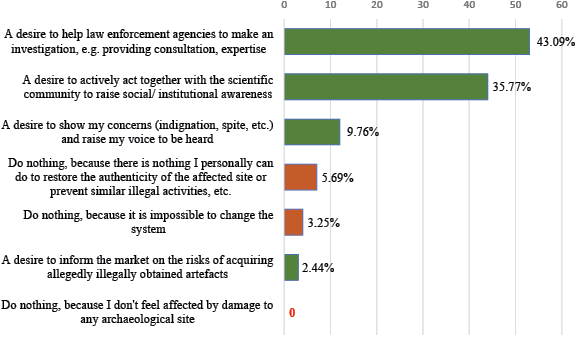

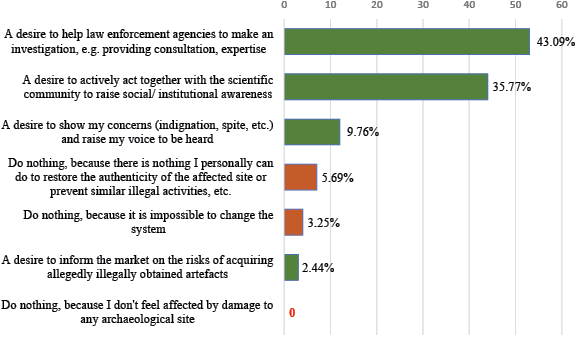

Despite the existing barriers, the survey reveals that heritage professionals are eager to have their voices heard and are prepared to take action, both collectively with their peers and individually, by supporting law enforcement agencies, markets, and other relevant bodies. When respondents were asked to share their initial reactions to yet another instance of archaeological damage, they were given the option to choose between proactive responses (green columns) and passive ones (red columns). Out of 133 respondents, 123 have chosen among the pre-offered reactions (one reaction per respondent was possible) with the following reply rates:

Graph 1. If integrity of an archaeological site of your concern is affected, what would be your first reaction?

1 diagrama. Jei būtų pažeistas jums rūpimos archeologinės vietovės / objekto vientisumas, kokia būtų jūsų pirmoji reakcija?

As shown in the graph, an overwhelming 91.06% of respondents (green columns in the Graph together) expressed a desire to take action.8 Notably, no respondent selected the option indicating indifference or a lack of personal connection to the damage (the option “Do nothing, because I don’t feel affected by damage to any archaeological site”). This strongly suggests that cases of archaeological harm evoke a profound emotional response among heritage professionals, reinforcing their commitment to addressing these crimes.

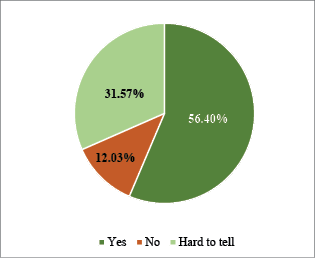

Despite the strong sense of suffering and the evident desire to take action, the responses to whether it would be appropriate to formally recognize the scientific community (e.g., through representation by national archaeological associations or the European Association of Archaeologists) as a victim in cases involving illegal activities targeting archaeological sites were not entirely clear-cut.

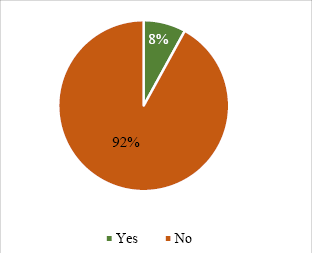

Graph 2. Do you believe it would be appropriate to formally acknowledge the scientific community (e.g., represented by the respective national archaeological association, EAA) as a victim (with all the rights accorded to a victim under the law) in instances involving illegal activities towards archaeological sites?

2 diagrama. Ar manote, kad būtų tinkama oficialiai pripažinti mokslinę bendruomenę (pvz., atstovaujamą atitinkamos nacionalinės archeologų asociacijos, EAA) auka (su visomis teisės aktų suteiktomis teisėmis) tais atvejais, kai neteisėti veiksmai vykdomi archeologinių paveldo objektų atžvilgiu?

As is shown, approximately one-third of respondents answered “hard to tell,” reflecting a degree of uncertainty on this issue.9 This ambiguity – “fear” (Interview with J.-O. Gransard-Desmond) - could be attributed to several factors, confirmed through the interviews. First, there may be a lack of awareness or understanding of the legal processes and the specific rights that such recognition would entail for the scientific community. Passive or restrictive behaviour of the public authorities and respective previous experience feed this uncertainty (Interview with J.-O. Gransard-Desmond). Additionally, the notion of a collective entity being acknowledged as a victim in criminal proceedings is not commonly encountered in current legal frameworks, which tend to focus on individuals. This unfamiliarity may contribute to the hesitation among respondents, who might not have fully considered the broader implications of such recognition. Furthermore, there may be concerns about the practical challenges in defining and measuring the harm experienced by the scientific community as a whole, especially when compared to individual victims whose losses are often more tangible and easily quantifiable (written answers U.Kadakas). Finally, the lack of public understanding and support, along with potential societal backlash against these “out-of-the-box” measures, may likely contribute to the respondents’ uncertainty about whether the formal acknowledgment of the scientific community as a victim is currently appropriate or feasible (interview with N.Kangert).

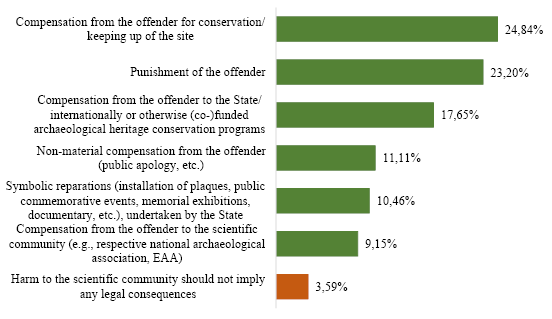

The next question in the survey focused on what type of reparation respondents believed would be appropriate for the scientific community if it were formally recognized as a victim in cases of archaeological heritage crime. Respondents were allowed to choose multiple answers.10

Graph 3. If you believe that it would be appropriate to formally acknowledge the scientific community as a victim in instances involving illegal activities towards archaeological sites, what in your opinion would be appropriate reparation for the harm caused to the scientific community?

3 diagrama. Jei manote, kad būtų tikslinga oficialiai pripažinti mokslo bendruomenę auka atvejais, susijusiais su neteisėta veikla archeologinių paveldo objektų atžvilgiu, kokia, Jūsų nuomone, būtų tinkama kompensacija už mokslo bendruomenei padarytą žalą?

Noteworthy, punishment of the offender was not seen as the most suitable form of reparation. Instead, the top choice was “compensation from the offender for the conservation and upkeep of the site.”11 More than a quarter of respondents (26.8% altogether) believed that monetary compensation, in various forms, aside of compensation for conservation, would be an appropriate remedy for the harm caused to the scientific community. However, one-fifth (21.57% altogether) of respondents favoured non-material or symbolic reparations. While non-material reparations are not so common in national criminal law — Latvia’s Criminal Law, for example, does not provide for symbolic reparations in any type of criminal cases, including heritage crimes12 — they are recognized in international criminal law. In the Al Mahdi case, for instance, symbolic reparations were awarded, with 1 euro granted to both the people of Mali and the international community as a symbolic gesture (Al Mahdi Reparations Order, paras 106-107). Similarly, in human rights cases, the acknowledgment of a violation can be considered “just satisfaction.” According to Article 41 of the European Convention on Human Rights, when a violation is found and national law does not provide adequate reparation, the Court may afford “just satisfaction” to the injured party. The purpose of just satisfaction is not to punish the offender but to compensate for the harm caused (Practice Direction 2022). “Just” is interpreted as “appropriate in the circumstances” (ibid.), and it may cover pecuniary and non-pecuniary damages, as well as legal costs and expenses (Harris et al., 2014, p.156-157).

In some cases, simply acknowledging a violation is considered sufficient reparation, without financial compensation awarded (Practice Directions). Given the complex nature of heritage crimes, recognizing harm may indeed be the most suitable form of redress for a broad and often not-so-easily-defined group of stakeholders, such as the scientific community. This acknowledgment, particularly regarding the irreplaceable loss of cultural heritage, can carry more significance than monetary compensation, offering a profound form of redress for heritage professionals.

According to the information available to the author the cases when the scientific community or the archaeologists (as a group of stakeholders) has ever been formally acknowledged as a victim in instances involving damage or destruction of archaeological sites are very uncommon. Thus, there have been no such cases, for instance, in Latvia (Kairiss and Olevska 2021; Written answers M.Kalnins), Estonia (interview with U.Kadakas; N.Kangert,). Similarly, no information on the relevant case law in France was received (Interview with

J.-O. Grasard-Desmond).

Besides, within the Survey, out of 133 specialists in the area, only 8% answered positively when asked “have you personally or the NGO (scientific community) or any other entity you represent has ever been formally acknowledged as a victim in instances involving damage or destruction of archaeological sites?”. Out of the 11 positive answers, 6 ones were from archaeologists (including one forensic archaeologist), 3 from representatives of heritage authorities (in some countries, for instance, Latvia and Estonia, it is common that the state represented by the heritage authority is recognized, usually solely, as a victim of archaeological crime), one from museum official and one from NGO international expert in the field of cultural heritage. 92% of all the respondents, representing different NGOs and entities and different occupations (practicing archaeologists, academic staff, museum officials, representatives of heritage authorities, etc.) were never individually or in community with others recognized as victims.

Graph 4. Have you personally or the NGO (scientific community) or any other entity you represent has ever been formally acknowledged as a victim in instances involving damage or destruction of archaeological sites? Yes/ No. If yes, please describe the case(-s).

4 diagrama. Ar jūs asmeniškai, ar NVO (mokslo bendruomenė), ar bet kuris kitas Jūsų atstovaujamas subjektas kada nors buvo oficialiai pripažintas auka atvejais, susijusiais su archeologinių paveldo objektų žalojimu ar naikinimu? Taip / Ne. Jei taip, apibūdinkite atvejį(-us).

The heritage professionals interviewed by the author appreciated the idea of recognition of the scientific community as a victim (Interview with N.Kangert, J.-O. Gransard-Desmond). However, they acknowledged the significant challenges posed by current legal frameworks, which are not readily equipped to accommodate such recognition. As one interviewee stated, “I like the idea, but […] the legal way is unknown” (Interview with N. Kangert), while another highlighted the lack of connection between science and law in this context (“no relation of science with the law” – Interview with J.-O. Gransard-Desmond).

Additionally, concerns were raised about potential perceptions that recognizing the scientific community as a victim might detract from the interests of other groups, including society as a whole (Written answers U. Kadakas). Despite these challenges, interviewees noted that formally acknowledging the scientific community as a victim could set a transformative precedent. Such recognition could pave the way for legal advancements while simultaneously raising public awareness and fostering greater support for the protection of cultural heritage (Interview with J.-O. Gransard-Desmond).

It should be noted, that at present, public understanding of the role scientists and researchers play as active defenders of cultural rights remains limited. This lack of awareness hinders societal appreciation of the harms these professionals endure as a result of heritage crimes. However, as public awareness grows, societal pressure and support could drive the adaptation of legal systems to address the harm caused to the scientific community more effectively, aligning legal frameworks with the broader goal of safeguarding cultural heritage.

The current research led to the following conclusions:

1. Effective implementation of cultural rights, in particular the right to take part in cultural life, requires States to establish mechanisms to investigate violations, assign responsibility, publicize findings, and provide remedies, ensuring victims of violations of this right receive appropriate redress.

2. Heritage crimes profoundly impact heritage professionals, emphasizing two key factors for victim recognition: the degree of suffering and the nature of the harm endured. Affected professionals experience the highest levels of harm when sites closely tied to their professional work or homeland are damaged or destroyed, reflecting deeper emotional and professional connections.

3. Heritage professionals are motivated to take collective and individual actions to combat heritage crimes, underscoring their emotional investment and dedication to preservation.

4. Uncertainty about formally recognizing the scientific community as victims stems from limited legal precedents, lack of awareness, and societal hesitation regarding collective victimhood in criminal proceedings.

5. According to respondents opinion (more than 50%) the material compensation from the offender (in the form of payment for conservation/keeping up of the damage site, contribution to archaeological heritage conservation programs or the respective scientific community concerned) should be the most appropriate reparation for the harm caused to the scientific community, with lesser emphasis on offender punishment and non-material compensation.

6. Formal acknowledgment of the scientific community or archaeologists as victims in cases of archaeological harm is exceedingly rare, as only 8% of surveyed professionals reported such recognition.

The current research sheds light on the profound harm inflicted on the scientific community by archaeological heritage crimes, highlighting how such harm is both personal and intricately tied to the illegal acts of damage and destruction. While the survey responses and expert interviews conducted here do not offer definitive conclusions, they reveal a clear trend: a significant majority of heritage professionals express a desire to be heard and, in many cases, to be recognized as victims of these crimes. This growing call for victim recognition—whether on an individual or collective basis—underscores the need for their suffering to be acknowledged and addressed through formal procedure.

At present, most national criminal justice systems lack mechanisms to accommodate claims of collective victimization in heritage crime cases. However, the findings emphasize the need for further exploration of how criminal law can evolve to better account for the negative impacts of heritage crimes on the scientific community. Such adaptations would not only address the profound emotional and professional toll on those dedicated to cultural preservation but also enhance protections for cultural heritage itself and help the state to fulfil its critical role in implementing cultural rights. Addressing these gaps through legal and institutional reforms is essential to advancing a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to victimization in heritage crime cases.

References

CESCR 2009. General comment no. 21, Right of everyone to take part in cultural life (art. 15, para. 1a of the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights). UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). 21 December 2009. E/C.12/GC/21. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4ed35bae2.html [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Code of Criminal Procedure of Estonia. Adopted on 12 February 2003, with amendments. Available at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/530102013093/consolide [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Criminal Law of the Republic of Latvia. Adopted on 17 June 1998, with amendments. Available at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/88966-kriminallikums (official translation available at: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/88966-criminal-law) [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Criminal Procedure Law of the Republic of Latvia. Adopted 21 April 2005, with amendments. Available at: https://likumi.lv/ta/id/107820-kriminalprocesa-likums (official translation: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/107820-criminal-procedure-law) [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Directive 2012/29/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2001/220/JHA. Official Journal of the European Union, L 315/57, 14 November 2012. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32012L0029 [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Gacka P. 2018. Attacks against cultural objects and the concept of victimhood in international criminal law. A critical analysis. Zeszyt Studencki Kół Naukowych Wydziału Prawa i Administracji UAM, 8, p. 25–41. Available at: http://zeszyt.amu.edu.pl/uploads/zeszyt/numery/Nr%208/02_GACKA.pdf [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Harris D., O’Boyle M., Bates E., Buckley C.M. 2014. Law of the European Convention on Human Rights. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Law Trove, 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-960639-9.

European Convention on Human Rights. 1950. Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. Council of Europe Treaty Series 005. Available at: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/convention_ENG [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Fribourg Declaration on Cultural Rights. 2007. University of Fribourg, May 2007. Available at: https://www.unifr.ch/ethique/en/research/publications/fribourg-declaration.html [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Hague Convention. 1954. Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, 14 May 1954, UNESCO. Available at: https://treaties.un.org/pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=0800000280145bac [accessed at 29 December 2024].

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. 1966. Adopted by General Assembly resolution 2200A (XXI), United Nations. Treaty Series, vol. 993, p. 3, 16 December 1966. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Kairiss A., Olevska I. 2021. Assessing endangerment of archaeological heritage in Latvia: legal framework and socio-economic aspects. AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology 11, a39-a72. DOI: 10.23914/ap.v11i0.281 [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Kerr J. 2013. The securitization and policing of art theft in London. Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London. Available at: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/2995/2/Kerr%2C_John.pdf [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Law on approval, entry into force and implementation of the Code of Criminal procedure of the Republic of Lithuania. Adopted on 14 March 2002, with amendments. Available at: https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/b3b97b11f31a11edb649a2a873fdbdfd?jfwid=zaoxg4j89 [accessed at 27 December 2024].

LSM. 2019. Veic izpostīto Loginu senkapu arheoloģisko izpēti. 05 September 2019. Available at: https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/dzive--stils/vesture/veic-izpostito-loginu-senkapu-arheologisko-izpeti.a330973/ [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Lubanga Reparations Appeal Judgment. 2015. Judgement on the appeals against the “Decision establishing the principles and procedures to be applied to reparations” of 7 August 2012 with amended order for reparations (Annex A) and public annexes 1 and 2, ICC-01/04-01/06-3129. The Prosecutor v. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo. Available at: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c3fc9d/ [accessed at 27 December 2024].

LVM. 2019. Sakopti Ciblas senkapi. 3 January 2019. Available at: https://www.lvm.lv/jaunumi/4154-sakopti-ciblas-senkapi [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Nicosia Convention. 2017. Council of Europe Convention on Offences relating to Cultural Property, 3 May 2017, Council of Europe. Available at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/convention-on-offences-relating-to-cultural-property [accessed at 29 December 2024].

Puig, S. M. 2008. Legal Goods Protected by the Law and Legal Goods Protected by the Criminal Law as Limits to the State’s Power to Criminalize Conduct. New Criminal Law Review, 11(3), 409-418. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1525/nclr.2008.11.3.409 [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Olevska-Kairisa I., Kairiss A. 2023. Victims of Heritage Crimes: Aspects of Legal and Socio-Economic Justice. Open Archaeology, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 2022-0293. https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2022-0293 [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Niec H. 1997. Cultural Rights: At the End of the World Decade for Cultural Development. Intergovernmental Conference on Cultural Policies for Development. Stockholm, Sweden, 30 March - 2 April 1998. UNESCO, CLT-98/CONF.210/CLD.6. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000109754 [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Ntaganda Reparations Order. 2021. Situation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in the case of the Prosecutor v. Bosco Ntaganda, Reparations Order, No. ICC-01/04-02/06, 8 March 2021. Available at: https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/CourtRecords/CR2021_01889.PDF [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Penal Code of the Republic of Estonia. Adopted on 6 June 2001, with amendments. Available at https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/522012015002/consolide [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Poyser B., Poyser S. 2017. Police practitioners’ and place managers’ understandings and perceptions of heritage crime in Nottinghamshire. International Journal of Police Science and Management, 19 (4), pp.247-260. Available at: https://doi-org.mu.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/1461355717730837 [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Poyser B., Poyser S., Doak J. 2022. A Typology of Heritage Crime Victims. Critical Criminology 30, 1057–1073. Available at: https://doi-org.mu.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s10612-022-09622-3 [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Practice direction 2022. Practice direction issued by the President of the Court in accordance with Rule 32 of the Rules of Court on 28 March 2007 and amended on 9 June 2022, pp.66-70. European Court of Human Rights. Available at: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/Rules_Court_ENG [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Practice Direction | Just satisfaction claims. Practice Direction on Just Satisfaction Claimes issued by the European Court of Human rights. Available at: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/d/echr/PD_satisfaction_claims_ENG [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Shaheed, F. 2011. Report of the independent expert in the field of cultural rights, Farida Shaheed. Human Rights Council, Seventeenth session, Agenda item 3: Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development. General Assembly 21 March 2011. A/HRC/17/38. Available at: https://www.right-docs.org/doc/a-hrc-17-38/ [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Shaheed, F. 2011a. Statement by Ms. Farida Shaheed, the Independent Expert in the field of cultural rights, to the Human Rights Council at its 17th session. 31 May 2011. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2011/08/statement-ms-farida-shaheed-independent-expert-field-cultural-rights-human [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Symonides J. 2002. Cultural rights: a neglected category of human rights. International Social Science Journal. Volume 50, Issue 158, pp. 559 - 572. Available at: https://doi-org.mu.idm.oclc.org/10.1111/1468-2451.00168 [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Tomasevski K. 1999. Preliminary report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to education, Ms. Katarina Tomasevski, submitted in accordance with Commission on Human Rights resolution 1998/33. E/CN.4/1999/49. 13 January 1999 Available at: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g99/101/34/pdf/g9910134.pdf [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Victims’ rights working group. 2018. Redress, Making Sense of Reparations at the International Criminal Court Background Paper Lunch Talk, 20 June 2018. Available at: https://redress.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Making-sense-of-Reparations-at-the-ICC_Background-paper_20062018.pdf [accessed at 27 December 2024].

World Heritage Convention. 1972. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, 16 November 1972, UNESCO. Available at: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ [accessed at 27 December 2024].

Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. UN General Assembly, Resolution 217A (III), Universal Declaration of Human Rights, A/RES/217(III). December 10, 1948. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights [accessed at 27 December 2024].

UN SC Resolution 2347 - Resolution 2347, S/RES/2347 (2017), 24 March 2017, United Nations Security Council. Available at: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n17/079/04/pdf/n1707904.pdf [accessed at 29 December 2024].

Irina Olevska-Kairisa

Santrauka

Nusikaltimai paveldo srityje, įskaitant nelegalius kasinėjimus, plėšimus ir archeologinių vietų naikinimą, daro didelę ir dažnai negrįžtamą žalą. Šie nusikaltimai ne tik fiziškai pažeidžia objektus, bet ir naikina neįkainojamas kultūrines ir istorines žinias, daro poveikį įvairioms suinteresuotųjų šalių grupėms. Nepaisant tarptautinio pripažinimo šioje srityje (pvz., tarptautinėse konvencijose, rezoliucijose ir kt.), teoriniai ir empiriniai tyrimai, skirti paveldo nusikaltimų aukoms identifikuoti ir jų patirtai žalai įvertinti, yra riboti.

Šis straipsnis skirtas šiai spragai užpildyti – sutelkia dėmesį į grupę, kurios nukentėjimas buvo daugiausia ignoruojamas, t. y. archeologus, paveldo specialistus ir platesnę mokslo bendruomenę. Archeologinių objektų žalojimas sutrikdo mokslinius procesus, dėl to prarandamos žinios ir profesinis identitetas. Tiems, kurie yra atsidavę paveldo išsaugojimui, šie nusikaltimai sukelia stiprias emocines reakcijas, įskaitant pasipiktinimą, bejėgiškumą, panieką. Tačiau dabartinė teisinė sistema teikia pirmenybę bausmei, o ne žalos atlyginimui, ir baudžiamajame procese nepripažįsta mokslo bendruomenės kaip aukos.

Remiantis apklausų analize ir ekspertų interviu, šiame tyrime nagrinėjamas paveldo nusikaltimų poveikis archeologams ir paveldo specialistams. Jame teigiama, kad reikia įvertinti galimybę juos oficialiai pripažinti aukomis baudžiamosios teisenos sistemoje. Pagrindinės išvados:

1. Veiksmingam kultūrinių teisių įgyvendinimui reikalingi mechanizmai, leidžiantys tirti pažeidimus, nustatyti atsakomybę ir vykdyti žalos atlyginimą nukentėjusioms šalims.

2. Žalos paveldo specialistams dydis priklauso nuo jų socialinių ir profesinių ryšių su pažeista vietove.

3. Daugelis paveldo specialistų jaučiasi pasirengę prisidėti prie valdžios institucijų pastangų kovoti su nusikaltimais paveldo srityje.

4. Teisinės kliūtys, precedentų ir informacijos trūkumas, taip pat visuomenės abejingumas yra pagrindinės priežastys, trukdančios oficialiai pripažinti mokslo bendruomenę baudžiamųjų bylų auka.

5. Daugiau nei 50 % respondentų pritaria, kad nusikaltėliai turėtų finansuoti kompensacijas mokslo bendruomenei, pabrėždami, jog svarbiau yra finansuoti išsaugojimą nei taikyti baudžiamąsias priemones.

6. Archeologų ir paveldo specialistų pripažinimas aukomis teismo bylose tebėra retas reiškinys – tik 8 % apklaustų specialistų nurodė, kad toks pripažinimas buvo suteiktas.

Šis tyrimas pabrėžia būtinybę įvertinti galimas teisines ir institucines reformas, kad būtų pripažinta ir atlyginta mokslo bendruomenei padaryta žala. Mechanizmų, pripažįstančių kolektyvines aukas, nebuvimas daugumoje teisinių sistemų palieka paveldo specialistus be oficialių teisių gynimo priemonių. Baudžiamosios teisės apsaugos išplėtimas mokslo bendruomenei ne tik pripažintų jos patiriamą žalą, bet ir užtikrintų veiksmingą praktinį kultūrinių teisių įgyvendinimą šios kultūros paveldo bendruomenės atžvilgiu.

Interviews and written answers

Interview with G.Kutris – telephone conversation with Gunārs Kūtris, expert of Criminal Law, ex-president of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Latvia, held on 6 June 2022.

Interview with U.Kadakas – online interview with Ulla Kadakas, president of the Estonian Archaeological Society, Researcher-Curator (Archeology) of the the Estonian History Museum, held on 11 September 2024.

Written answers U.Kadakas – written answers received from Ulla Kadakas, president of the Estonian Archaeological Society, Researcher-Curator (Archeology) of the the Estonian History Museum, received on 29 October 2024.

Written answers M.Kalnins – written answers from PhD hist. cand. M. Kalniņš, the heritage specialist of the Department of the circulation of cultural goods of the National Heritage Board of the Republic of Latvia, archaeologist, the Head of Latvian Society of Archaeologists, received on 21 March 2023.

Interview with N. Kangert – online interview with Nele Kangert, advisor on archaeological finds of the Department of Archaeological Heritage of the Estonian Heritage Board, held on 30 October 2024.

Interview with J.-O. Gransard-Desmond – interview with PhD Jean-Olivier Gransard-Desmond, co-founder and administrator of the ArkeoTopia, held on 31 October 2024.

1 Discussion held at the round-table session of the Community on Illicit Trade in Cultural Material at 29th Annual Meeting of the EAA in Belfast, Norther Ireland, on 1 September 2023.

2 The concept of access – the so-called 4-A scheme – was developed in 1999 and comprised availability, accessibility, acceptability and adaptability (Tomasevski, 1999). It is systematically used by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in its general comments and relating to cultural heritage it consists of (a) physical access to cultural heritage, which may be complemented by access through information technologies; (b) economic access, which means that access should be affordable to all; (c). information access, which refers to the right to seek, receive and impart information on cultural heritage, without borders; and (d) access to decision making and monitoring procedures, including administrative and judicial procedures and remedies (Point 60, Shaheed, 2011).

3 “States should make available effective remedies, including judicial remedies, to concerned individuals and communities who feel that their cultural heritage is either not fully respected and protected or that their right of access to and enjoyment of cultural heritage is being infringed upon. In arbitration and litigation processes, the specific relationship of communities to cultural heritage should be fully taken into consideration” (Point 80 (l), Shaheed, 2011).

4 With some variations, this definition is transferred into the national laws. For instance, see Section 95, Part 1 of the Criminal Procedure Law of the Republic of Latvia; Section 37, Part 1 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Republic of Estonia; Article 28, Part 1 of the Republic of Lithuania Law On approval, entry into force and implementation of the code of criminal procedure. While, for instance, in France there is no precise definition in the Penal Code, the victim must be understood as any person, natural or legal, or group of persons who have suffered, directly or indirectly, from an act prohibited by criminal law (https://www.justice.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/2024-02/RSJ2022_chapitre%2013.pdf ).

5 Hereinafter the results are aggregated as follows: “0” – not affected/ suffered at all; “1” to “5” – slightly affected/ suffered; “6” to “7” – quite affected/ suffered and “8” to “10” – very much affected/ suffered.

6 Comparatively less support was given to such capacities as representatives of the confession concerned (31,5% considered themselves very much suffered) and representatives of the relevant (archaeology-related national or international) NGO (48.8% considered themselves very much suffered). The author assumes that the rate of support to these capacities might be higher in areas with certain cultural/religious traditions (see, e.g., Al Mahdi case of heritage destruction in Timbuktu, Mali) and NGOs with higher level of comradery (out of all the respondents to the survey, 55,4% of non-EAA members evaluated their sufferings in this capacity as very high (“8” to “10”) with this rate being 40,7% among EAA members).

7 The interviewee mentioned disinterest, unjustified prolongation of terms, incomprehension of certain agents from the national bodies; excessive dissemination of heritage protection obligations among many public authorities; absence of a neutral third party to review the disputes arising between archaeological and related associations and public authorities.

8 The remaining ten reactions were provided by the respondents themselves and predominantly they also showed the desire to act – the desire to inform and help heritage authorities in their investigation and damage assessment, the desire to provide professional advice, etc.

9 It is noteworthy that respondents who were not members of the EAA were significantly more confident in their belief that the scientific community should be recognized as a victim. Among non-EAA members, 66.22% responded “Yes,” 25.68% answered “Hard to tell,” and only 8.11% said “No.” In contrast, the responses from EAA members showed more uncertainty, with 44.07% saying “Yes,” 38.98% responding “Hard to tell,” and 16.95% answering “No.”

10 Multiresponse method was used for this question. The aggregated graph presents % of all responses, not the respondents (130 respondents answered the question).

11 It should be mentioned that in certain countries, for instance, Latvia or Estonia the courts do not typically require offenders to restore damaged heritage sites. Often, the owners (alone or co-financed by the state agencies) or volunteers step in to carry out conservation efforts, sometimes years after the damage occurs (see, e.g., LSM 2019; LVM 2019; Interview with N.Kangert).

12 Section 36 of the Latvian Criminal Law provides for the possible forms of punishment, which do not foresee any kind of symbolic reparation; Similarly, no provision for symbolic punishment is provided for in Estonian Penal Code (Chapter 3: Types and terms of punishments).